95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 31 August 2022

Sec. Digital Impacts

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2022.908456

This article is part of the Research Topic Migration Studies and the Digital: Datafication, Implications and Methodological Approaches View all 7 articles

Digitization and digital methods have had a big impact on migration history and history in general. The dispersed and fragmented nature of migration heritage that involves at least two countries and many cultural heritage institutions make it clear that migration history can be much improved by using digital means to connect collections. This makes it possible to overcome the biases that policy have introduced in private and public collections alike by selection and perspective. Digital methods are not immune to these biases and may even introduce new distortions because they often change heritage contextualizations. In this article, Van Faassen and Hoekstra argue that therefore they should be embedded in source criticism methodology. They use the example of post-world War II Dutch-Australian emigration to show how a migrant registration system can be used as a structural device to connect migrant heritage. They use methods from computer vision to assess the information distribution of the registration system. Together, connecting collections and information assessments give an encompassing view of the migrant visibility and invisibility in the heritage collections and perspectives for scholars to become aware of heritage biases.

In the last two decades migration studies showed a more pronounced interest in what they call the “invisibility” of migrants. The topic was put on the agenda by developments within the multidisciplinary field of migration studies itself, but also by debates within the archive and heritage sciences, that were exploring the new responsibilities and possibilities coming with the multimedia and digital era. The volume Europe's invisible migrants (2003) for instance, that protaganized migrants of decolonization who were till then euphemistically categorized as repatriates by their governments and understudied by academia, was inspired by the new approach suggested by Lucassen and Lucassen in their landmark work of 1999 (Lucassen and Lucassen, 1999). They argued that migration history had developed too many typologies, like forced and voluntary migration, that had evolved into fixed dichotomies and divided migratory experience and scholarship alike and that these conceptual walls had to be broken down to open up the field again (Smith, 2003, p. 18). From 1993 academia picked up that certain migrant communities experienced themselves as being invisible because as a result of strict assimilation policies little tangible heritage of them had been retained with which they could distinguish themselves (Walcker-Birckhead, 1988; Willems, 2001, 2003; Coté, 2010, p. 122; Peters, 2010; Horne, 2011).

The cultural heritage field was criticized in those years that it supported and contributed to this invisibility as it only followed the official archives bringing just official stories and histories that affirmed the importance of hegemonistic groups in society, usually the white majority. To remediate these false and lopsided views, critical scholars argued that archives need to be decolonized (Stoler, 2002; Jeurgens and Karabinos, 2020). Other researchers and cultural heritage professionals have made ongoing efforts to find and tell alternative minority stories. They also strove to identify cultural heritage in the archive by creating forms of alternative access. Özden Yalim's “Passing on ‘invisible' histories” (Yalim, 2008), for instance, put her finger on the blind spots in the Dutch women's movement and its archive Atria for the role of immigrant women in the labor force. In the 1998 preparations of the commemoration of the 100-year National Exhibition on Women's Labour (1898), immigrant women were first completely left out. She describes the methods that were used to remediate this: collecting, preserving and reconstructing the cultural heritage of several women immigrant groups by using oral history and storytelling techniques and new media, so that the immigrant women were “given a voice,” which put them at the center of collaborating with experts and academics. In the United States and Oceania there have been similar experiments of co-creation with first nation or indigenous minority groups with heritages with forms of expression that do not fit the customary archive format (McKemmish, 2017).

Scholars who engage in combining digital humanities and migration or heritage studies also point at a shortage of sources as a cause for a certain blindness to study certain migrant groups. In the newly launched Journal of Digital History, Oberbichler and Pfanzelter (2021) justly point out that return migration—defined as cross-border migration to the country of origin—is a too frequently neglected topic in migration studies and migration history, as return migration is always part of every migratory movement. In their opinion national or even regional approaches have proven to be fruitful for studying the historical developments of migration, despite its transnational nature, “where archival material is scarce and sources often are lacking.” They experimented with corpus building from German language newspapers using text mining and machine learning techniques to address the lack of sources for studying return migration from the Americas to Europe between 1850 and 1950.

Although we agree that national and regional approaches can be fruitful in migration studies, we have a different opinion about their statement on the scarcity of sources and archival material. Precisely because of the transnational character of migration, migration history and migrant heritage is by its very nature dispersed over different collections in different countries, but not necessarily absent. As the examples on invisibility studies above show, there are often issues of ethnicity at stake, paradoxically enough even for what most researchers see as dominant white migrant groups. Upon closer inspection the more important common denominator or cause of experienced invisibility seems to be the policy at the time: ways of categorization that concealed certain groups, not only in the public debates of the time but especially in the archival heritage. This problem was discussed in 2013 in Schrover and Moloney's study on Gender, Migration and Categorization. They observed that scholars tend to follow the categorizations that policy makers use, often as a result of the source material that is available and organized according to these categorizations (Schrover and Moloney, 2013, p. 9). Therefore, we argue, we should not only engage in preserving heritage by co-creating or corpus building to make migrants visible but also take one step back and ask ourselves how to get the best out of the existing archival collections. More specifically our research questions are who and what is actually visible in dispersed archival migrant collections? How can digital methods help in discerning what is actually visible and what is not and what does this mean with respect to source criticism?

In this article we use the Migrant Mobilities and Connection project in which we have been working on methodologies for structurally connecting the information for Dutch-Australian migrants from 1945 to 1992 as a use case. We work on an aggregative representation that includes the many different perspectives that together constitute the migrant experience. Processes of selection and dispersion of information and heritage accumulate to make collections silos of information when they are digitized and datafied. In our case migration registration systems can play this pivotal role in connecting different types of information, ranging from personal files and stories to policy files and propaganda and including archive files, private collections, books, photos, moving images and sound, as well as digital communication such as Facebook and Instagram groups (Arthur et al., 2018). We argue that for exploring dispersed collections and for analysis, a serial resource is vital to interconnect dispersed cultural heritage and provide them with a logical context and make it possible to move beyond the impressionism of isolated case studies and cherry-picking.

In the following sections, we first elaborate on the discourse on the decolonization of the archives in order to explore the impact of digitization and the use of digital methods and the way scholars have used them and what that means for what is visible and invisible for them. Then we explain the way we try to connect different collections regarding migrants and migrant policy in our project by using a data backbone. Finally, we elaborate on the digital methods we used to explore the impact of national and bilateral policies on the nature and content of the different collections and what this means for the visibility of migrants in heritage collections.

The “archival turn” of the recent years, brought a lot of attention to reconfiguring and decolonizing the archive by paying attention to the ideological biases that are part of the archive that explicitly and implicitly capture policies and their ideologies and the hegemonistic master narratives that they supported. It made the archive itself an object of study and is for a part, a reinterpretation based on a combination of distant and close reading, but it has also been proposed that digital methods of virtual reordering could reconfigure the archives in such a way that alternative narratives cold be supported (Gilliland et al., 2017; Ketelaar, 2017; Jeurgens and Karabinos, 2020; Hoekstra et al., 2021, p. 8). We noticed that generally the “archival turn” just paid attention to the single archive. For example, writing about the changed relation between archivists and historians, Blouin and Rosenberg (2011, p. 4) write: “The most common understanding of an archive would describe it as a body of records generated by the activities of a specific individual or organization and commonly located (although not always) in a repository housing similar or related collections. The Boston City Archives holds records generated by the bureaucracy of the city of Boston. The Archives Nationales in Paris and the U.S. National Archives in Washington hold essential records of the modern French and American states.”

The extent and richness of digitized collections and the challenges in exploring them with new methodologies reinforces the tendency to concentrate on a single collection. However, this contrasts with how historians usually work. Chassanoff (2013, p. 461) notices that “Historians typically consult a large number of institutions during the archival research process. Archival institutions may include public or university libraries, academic special collections/repositories, state or local historical societies, museums, and state or government archives.”

The reason that historians consult different archives is that they want to contextualize their findings. Archives were always created for a specific purpose, usually related to administrative procedures that involve different actors, even if they are from a single government (Upward et al., 2018). Because of this, different archives and even archive collections contain different information, say the policy files that set out the policy lines and the administrative files that recorded the implementation of that same policy. This is the case for archives (and other heritage collections) that come from for instance different departments of the same organization, but of course even more if they were created by different organizations for different purposes. The separation of collections leads to a fragmentation of the policy and executive files that were once part of a connected reality. To get a fuller grasp of past realities, it is vital to reconstruct politics and ideas or ideologies and recontextualise documents and collections by connecting them. This also makes it possible to come to a fuller awareness of the ideological biases and the necessary scope for decolonization and other assessments of past policies and ideologies.

Historians have always seen the need for combining heritage collections but in the case of migration history it is obvious that heritage is distributed over many different collections in different countries. In practice it was always impossible to connect this dispersed heritage, because of the practical issue that they are physically distributed over different institutions with different policies and even over different countries, like in the case of the migrant heritage. Of course, historians have known this for a long time, but without connected collections it is really hard and very time consuming to get an idea about all collections relevant for a particular historical phenomenon. Interviewing historians about their use of digitized archives, Coburn (2021, p. 404) cites as one of the main perceived advantages “the improved availability of relevant materials, describing this as the ability to forestall travel to archive sites for research purposes.” He continues, that aside from traveling it is next to impossible to connect a myriad of collections in another way than using digital methods. If chosen carefully, digital methods enable us to make links between collections in a way that makes it possible to explore a much wider variety of heritage materials in a structured way. Coburn points out that there is concern about the selectivity of digitized archives and the naiveté of (other) historians in dealing with them (Coburn, 2021). He argues that in his experience historians are actually well aware of the pitfalls both of digital selectivity and the loss of context that occurs when archival items are located by search engines. This is indeed an important issue that researchers have to take into account. He also cites historians who try to reconstruct this context. As we have argued above, a full context reconstruction should include at least an awareness of all heritage holdings involved.

Of course, there have been numerous efforts to connect previously separate historical sources into a connected resource. Indeed, the linked data movement strives to enable linking data and there are large meta collections like Europeana (cf. Hoekstra et al., 2021). However, as we have argued elsewhere collections should not be just linked but structurally connected into a new dataset instead, to prevent digital selectivity, processing and decontextualization from introducing other, more subtle biases. We have called such a connected set a datascope (Hoekstra and Koolen, 2019). It needs a structural device to serve as a backbone to connect the constituent datasets and collections. The purpose of our connecting efforts is to construct a datascope for Dutch-Australian emigration using the registration cards as a structural device.

Writing about biases of dominant culture in the archives and the ways digital methods can contribute to solving this, Blouin and Rosenberg (2011, p. 4, cf. Hoekstra et al., 2021) write about the awareness of “the importance of ‘authority'... in conveying a sense of the past as well as an understanding of its documentary residues. This led [them] to such issues as the role of identity and experience as 'authorities' in forming both historical understanding and the structures of archival collections; the activism of archivists themselves in these processes; and the forms and often contested natures of archival and historical sources.”

In other words, the archives and other heritage collections reflect policies, usually official policies, both past and current. The influence of policy and policy informed decisions on the archives is manifold and multilevel. The first level is the formation and division of archives and archive collections themselves—which agents were involved in governance and therefore in the creation of an archive and what aspect and perspective do they represent? The second level is the composition of the different collections—archive collections are usually the residues of administrations. What was its purpose and what do they contain and how was it ordered? The third level is about the nature and content of specific administrative devices, such as registration systems—what does it register, what is left out?

These represent very different facets of a governance system and the way it kept and handed down its records. Digitization and datafication make it possible to explore and connect much larger portions of an archive, but first they also introduce new policy induced biases of selection and organization. Second, they tend to obscure traces of policies because they distort old context and introduce new ones, they tend to obscure the policies that determined the original context. On a final point, researchers have to keep in mind that digitization brings the possibility to connect archival and other heritage materials, but most of heritage is not digitized and probably never will be. The last European survey of 2017 estimated that 10 percent of European heritage collections had been digitized and 40 percent would never have to. The same report remarks that even if 80 percent of the cultural heritage institutions in 2017 had digital collections, less than half of them had a digitization strategy document whatsoever (Nauta et al., 2017, p. 28, 5, 15–16; Nyirubugara, 2012, p. 81–88). The parts that have been digitized, are only digitized partially. Often there is a selection of the “most interesting” or most used parts or just the inventory and some highlights are digitized. For example, the Dutch National Archives write that “the most frequently consulted archives of the past 20 years have been selected for digitisation” (Nationaal Archief, 2022) and the National Archives of Australia state they “[d]igitise the collection with particular emphasis on [...] high-use information” (National Archives of Australia, 2022, also cf. Thylstrup, 2019; Hauswedell et al., 2020).

This is even more the case for datafication, as datafying puts structural requirements on the contents of the documents. For instance, a form-based registration can be converted relatively easily, but it is really hard to fit in annotations that do not follow the structure of forms. Moreover, there are many documents in which information is not structured in such a way that they can be reduced to a data structure easily, for instance because they contain a policy argument or an analysis instead of data. In this way, much of this type of documents are not datafied and they are seldom included in data-based analysis. All this has even more consequences for dealing with (partially) digital research. Some choose to circumvent these confinements of digital research by concentrating on a single digital collection or digital corpus. While this is a legitimate object for research, migrant history teaches us that such an approach is too limited. Others have introduced alternative collections by using social media and oral history to better represent the unheard voices (for example Leurs, 2021). Social media only became available with the advance of the digital. However, it has often been pointed out that social media echo the views and preferences of the public debate and policy issues at stake (cf. Tufekci, 2017). We would argue that similar considerations are true for oral history. While these sources are valuable contributions, they should still be critically examined using the same criteria of source criticism.

This illustrates our point that it is important to not just decolonize the archive, but to structurally connect policy with what may appear cultural heritage. Researchers often know that collections are institution artifacts, but fail to take into account that they also change dynamically under the interaction with both society and policy changes (but see Upward et al., 2018). The characteristics and changes of archives influence who is visible in the archival collections, because like policy, archives do not treat everyone equally. Digitization often unconsciously enhances these processes of selection. Digital methods may be used to make visible what was previously invisible, but they also can result in affirming old policy preferences if archivists and researchers are not aware that they are hidden in the archive, and often old policy is lost in time.

Our project Migrant Mobilities and Connection was conceived as a combined digital-analog project in which we have strived to incorporate these different aspects from the beginning. Its point of departure was the awareness that migration history and migrant heritage is by its very nature dispersed over different collections in different countries. Therefore, a study that is based on just one collection, let alone one corpus, for us was never a satisfying option because it leaves out the information and perspectives that are represented in other collections. We strove to find ways to integrate digital and analog material and allow for many different facets of the history of migrants, instead of telling a single story (Faassen and Hoekstra, forthcoming). Migrant, Mobilities and Connection, therefore, has a 2-fold aim: first digitally connect the cultural heritage of Dutch-Australian migrants that is dispersed over many collections in many institutions in two countries. As the archival heritage of the emigration policy of the Netherlands is not digitized and still hidden behind very generic inventory terminology which is—because of the complexity of the Dutch emigration governance system—dispersed over more than eight governmental ministries and even more private organizations, the first effort was to digitally identify the historical actors (and thus record creators) involved and to make a summary description of their 367 migration-related collections (see Figure 1, Faassen, 2014b).

Although the documents themselves are still not digitally available, at least their existence can be found online and their interdependence is made clear. The next step was to find a connecting device to link the institutional to the personal in both countries. As a core for the Migrant-project, we chose to digitize the migrant registration cards that were made by the Dutch emigration services in the Netherlands and traveled to Australia with the migrant application files, which served as input for the Australian immigration authorities. Subsequently these cards were repurposed by mainly the emigration attaches that were positioned at the Dutch consulates in Australia to support the migrants in their new home country (Faassen and Oprel, 2020). In doing so we hope to have established a new resource that is easily accessible for a larger public (the core business of Huygens Institute, see also Arthur et al., 2018) and that can be supplemented by other public or private collections, interviews etc. This resource can also facilitate our second aim: to start answering our main research question: how are policy and migrant agency related with respect to the whole migration experience?

The card files of migrant cards are part of the collection of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (NL_HaNA, 2.05.159). There are 51,525 cards that correspond to 100,000 images. They represent circa 180,000 migrants, or 80–90 percent of all migrants to Australia, as the cards contained data about migrant units, often but not always families, with personal data about the migrants. The cards contain a number of data about the migrants like personal data such as name, birthdate, occupation, place of origin and the dates and means of migration. These were compiled before migration. The cards contain additional unstructured data about interactions with the consulates. Because they comprise such a large share of the emigrants and a lot of their context, the cards enable us to connect all sorts of digital heritage (Faassen and Hoekstra, forthcoming). They also make it possible to make informed samples.

From a research point of view, it is necessary to assess the cards. We have images of the cards and a very summary index table with core data. In digitizing, the archive lost the connection between the index and the images. Also, the original order was disturbed in many places. We cannot read all cards because there are far too many and the cards contain a mix of typed and handwritten information that made experts in text recognition for the most part shy away. Developments in Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) now make it possible to recognize manuscript and mixed manuscript and handwritten text. In fact, one of the authors is involved in other projects that employ HTR for a large scale archive resource and compare and develop recognition methologies (Koolen et al., 2020). However, the cards are mostly structured models for which recognized text is not sufficient and therefore that require much more additional work on structuring (cf. Tames, 2022).

We did a general assessment of the cards with a one percent sample, taking each 100th card (consisting of 2 images and possible follow-up cards as far as they were localizable), structuring and analyzing the information on the cards. The sample confirmed that there is a wealth of information about migrants on the cards about the Dutch-Australian migrant population. Even a correctly drawn sample results in a simplification, or a small world representation of a larger world (McElreath, 2020, p. 19–46). Historians often complement this simplification by taking cases from the collection and studying these in depth to get insight into the variation, an established method in history. For the emigration cards, however, this posed a few different problems, especially selecting the cases. It is very hard to select the largest cards as some historians suggested, as we have no physical or visual access to the cards. Moreover, there may be a reason that files get big that would lead to an unconscious selection bias, also known as cherry-picking, as it is unclear for what reason migrants would get more attention. Notwithstanding the samples, the cards effectively were closed for research and we had to find a solution to complement the sampling. This solution had to be based on digital methods to be able to deal with the size of the registration system. We devised a method with different steps (Hoekstra and Koolen, 2019; Hoekstra, 2021).

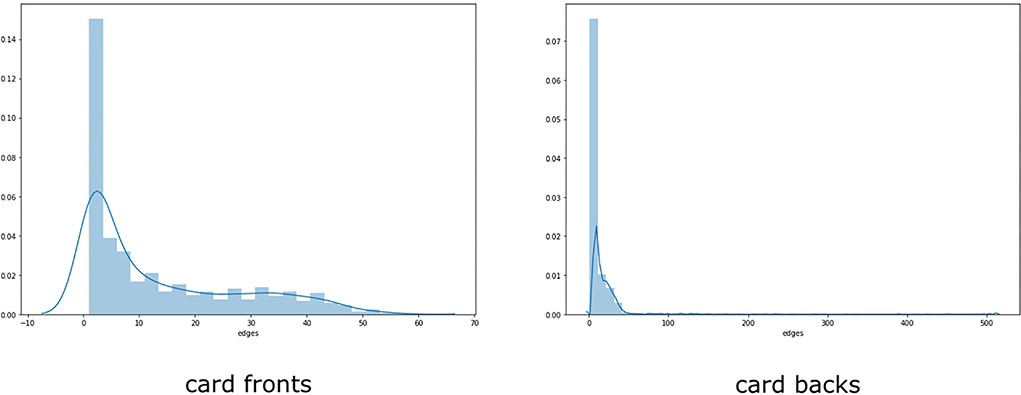

We first manually reconstructed the relation between images and the index table. Then, we devised a way to measure the information density on the cards, using a simple form of computer vision. The mixed script on the cards may be too difficult to transcribe using a combination of OCR and handwritten text recognition (HTR), but it is possible to measure the amount of writing on the cards, using the script edges that can be measured using software (see Figure 2). In this way we do not know what is written, but how much is written, giving a measure of the information density on the cards. The information density can then be related to what we do know about the content of the cards.

What we know about the cards is analyzed in the sample analysis. We distinguished different stages and influences on the cards, that may be depicted in the schema in Figure 3.

The different stages in the scheme are all visible on the cards. As we wrote above, the front of the cards was (primarily) filled in before migration, and the back of the cards after migration. The card fronts are therefore better structured. There is also a time lag with an average of 2.5 years and a median of 1 year between the date of emigration on the front of the cards and the first dates on the back of the cards. Although the cards sometimes contain information about the travel themselves and the first time after arrival, this is not structural. In the information distribution this translates to a different characteristic for the card fronts compared to the card backs (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Differing distribution of edge densities on registration card fronts and backs—(source—emigrant registration cards).

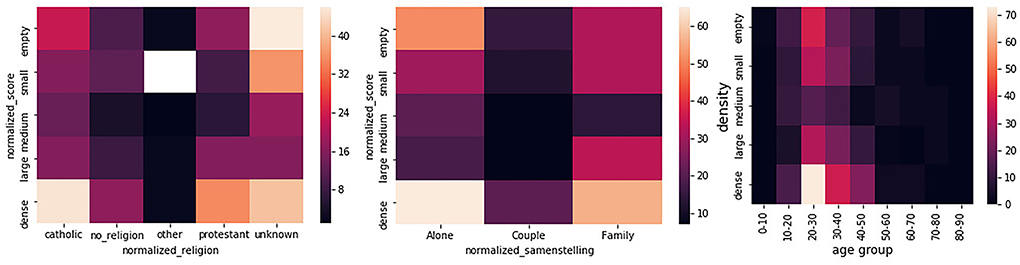

Because the cards contain partial reflections of the lives of the migrants, it is obvious to assume that some properties of the migrants would determine the information on the cards. Of course, the cards represent the perspective of the registering authorities, that is the Dutch Emigration service (NED) in the Netherlands and consulate personnel, mainly the emigration attaches and the social work officials in Australia. We have studied the possible relations between all the variables, ranging from age to family composition, religion, place of residence in the Netherlands primary to migration and the migrant scheme (some examples in Figure 5).

Figure 5. Some examples of analyses of migrant properties and card densities, that were inconclusive—(source—emigration registration cards).

Only the place of residence and the migrant scheme showed conclusive influence on the information distribution. This allows for one conclusion, but also leads to a further research question. The conclusion is, that in selecting the largest files (that is the cards with the highest information density) from the registration card files, will not introduce a selection bias for variables such as age, family composition or religion. If we want to study migrant lives, the distribution of information density does not reflect any sub groups among the migrants. Of course, there is a selection bias because cards with a lot of information reflect the most eventful lives, for whatever reason, but this constitutes a point of further study and it is a good idea to compare them with (a selection of) less information dense files.

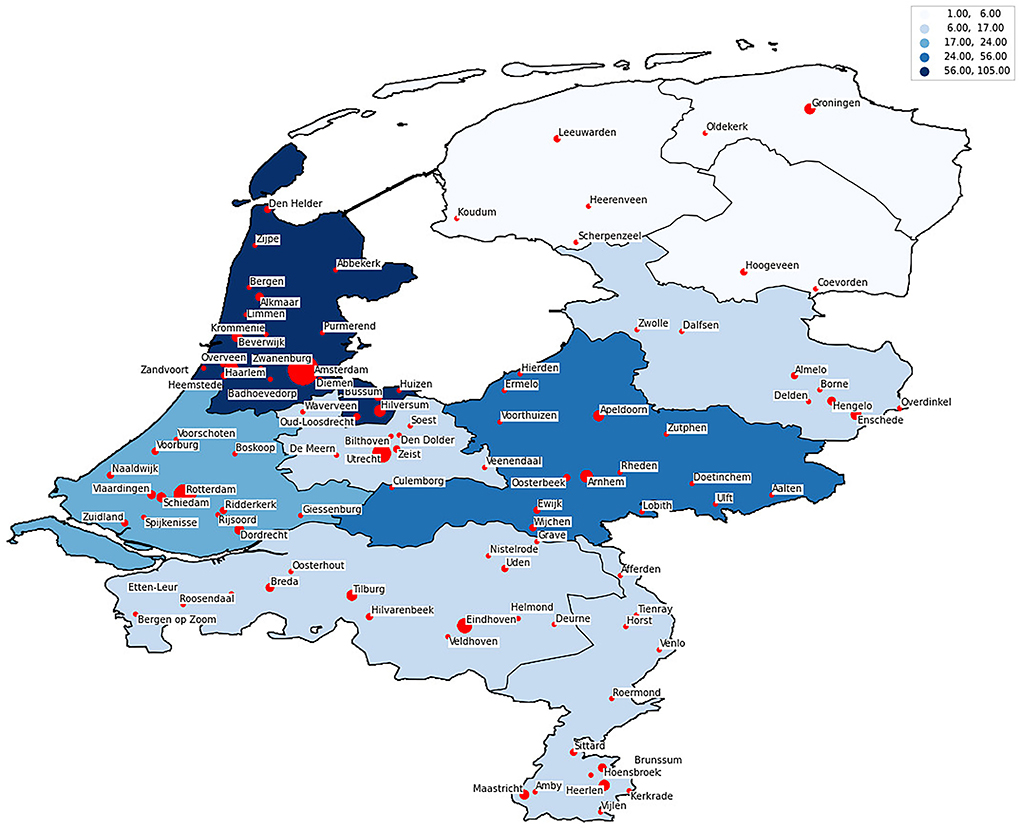

The further research questions that this raised, is why the place of residence and the migration scheme did have a marked influence on the cards (Figure 6). To be able to assess that, we first have to consider the intention of the instrument of the cards for the authorities. It was a type of monitoring device that was used at two different stages of emigration. The first was to record and streamline the emigration process itself. That stage, however, ended with the arrival of migrants in Australia and was primarily recorded on the card fronts. The second stage that was recorded on the card backs (and possible follow-up card) started well after arrival. The question is why the Dutch authorities would care about the Dutch who had left. This is only obvious for the strict consular activities in which official intervention of either a consul or the ambassador was required, such as passport prolongation and remigration. But the range of activities employed by the consulates was much broader and had to do with the well-being of the migrants. This reveals that there was an active policy by the authorities aimed at making emigration a success (also compare Devereaux, 1996; Torpey, 1998; Shoemaker, 2008).

Figure 6. Map of the origin of Dutch-Australian emigrants (1951–1992)—(source—emigrant registration cards).

The two influences of the migration scheme mentioned above reflect different sides of the policy. The variation in place of residence suggests that there was a conscious policy on the part of the authorities to stimulate migration in parts of the country. Although this is known from historiography, the focus has been primarily on the agrarian sector, as post-war emigration policy is understood as a solution for the “small farmers problem” in the Netherlands. This seems in line with the fact that the province of Zeeland is absent and the Northern provinces of Groningen, Friesland and Drenthe are underrepresented in the sample the map is based on. However, as emigration was meant to be complementary to the industrialization policies (Faassen, 2014a), this also calls for further research, because it seems likely that there also was a relation with post-war changes in the industrial situation of the Netherlands and the closing of the Limburg coal mines in the early 1960s.

The effects of the different migrant schemes are much more subtle. Most migrants traveled under a migration scheme, that is an agreement of the Dutch and Australian governments that subsidized the passage on the migration ships or planes. The most important was the Netherlands-Australian Migration Agreement, that was officially operative from 1951, but there were more schemes (Faassen, 2014a, 165–6). The schemas implied an involvement of both the Dutch and the Australian authorities that found an expression in many areas.

In the NAMA case, Australian co-subsidizing of the passage required migrants to work in Australian government service for 2 years. The schema also included migrant selection with both Australian and Dutch involvement (Schrover and van Faassen, 2010). On the other side, it also implied that the Dutch authorities wanted to make migration a success. Return migration was always sizable, but the contemporary files in the archives were marked secret as return was seen as failed migration, a label that still dominates historiography. To take away reasons to return, the Dutch authorities invested in social officers that resided at the Dutch consulates in Australia, partly in response to bottom-up pressure from the civil society organizations, who had the majority in the Dutch emigration governance system [(Faassen, 2014a), Ch. 2]. They supported the emigrants by intervening in their affairs, providing assistance in all sorts of social matters. They also were the ones who (predominantly) filled out the backs of the cards. In our sample, we classified several types of events they noted in categories, such as finance, housing, health, labor, social issues, consular/administrative. In combining close reading (sample) and distant reading (edging) of the cards it is possible to reveal how policy and agency come together for the events finance (Figure 7) and housing (Figure 8).

An example of a direct influence of a migration schema is visible in the visualization of financial events. From the graph, it would seem that there were many migrants with financial issues in the mid-1960. Upon closer inspection, however, it appears that these mostly stem from migrants that migrated under the so-called youth program (Jongeren Programma, JP) who could only stay for one or 2 years in Australia and had to save with the consulates for their return fare. The sums they saved were notated in succession on the registration cards. Archival research to find an explanation for this phenomenon revealed that this temporary migration, embedded in youth programs, was a deliberate policy of both governments, aiming at increasing the “emigratability” of the Dutch population (when departure figures went down after 1956) by introducing young people to perspectives abroad for a longer period of time. After their return to the Netherlands, the youth could function as “goodwill ambassadors” for emigration, as they were expected to supply emigration supporting information (Faassen and Hoekstra, 2015). Later on, the Youth Programs were succeeded by Working Holiday Schemes (NL-HaNa, 2.15.68, inv.nr. 1351-1353 and 1355-1357) (Figure 8).

One of the other prominent problems in the Dutch-Australian migration was housing. There is a wealth of studies on the first years after arrival especially from the migrant perspective, when emigrants were housed in camps (or, formally, reception centers) like Bonegilla, Scheyville, Wacol etc. or hostels and families were separated from the moment the man had to start working, for instance to fulfill the NAMA-scheme requirements (Peters, 2001, Ch.4, Walcker-Birckhead, 1988, p. 190–206; Eysbertse, 1997). In contrast with the graph on finance, the housing graph doesn't show specific patterns that prompt analysis. In general, it follows the pattern of the departure peaks and tops, which is rather obvious. However, analyzing the housing events per migration scheme show more variation (Figure 9).

The first thing that stands out is that the Youth Program (JP) showed the least housing events, in contrast with the two largest and simultaneously run schemes NAMA and the Netherlands Government Agency Scheme (NGAS), which have the highest percentages of housing events. This is still rather obvious as migrants under the Youth programs usually traveled alone, or at least without a family. For the other schemes (which are often affiliated with churches and their social networks) it is known that most of the time sponsorships of private persons (including housing) were required. Close reading of the housing events on the cards of the sample however reveals an intriguing shift around 1960–1961. Complaints about the migrant camps and hostels then make way for questions about Building Societies and Housing Committees. Together with the downward trend in housing events/problems after 1960 in the graph in Figure 8, this can be interpreted as a possible starting point for further analysis on supposed governmental policy on housing. Archival research in both countries indeed reveals the other side of the camp-stories in migrant studies.

In 1948–1949 the Australian Government organized a conference on housing for “Australians and migrants” in which a policy was formulated to improve the supply of building materials and secure a greater output of houses. One of the suggestions to the Australian states was to order more “prefabricated houses” (NAA, A445/202/3/34). Archival research in the Netherlands shows a twofold response to this idea. The Utrecht Building Company Bredero that already developed the idea of prefabs during the Second World War (Clark, 2002, p. 24–25) took the momentum (1950) to establish an Australian holding to build prefab-houses for Dutch migrants who were employed at the Snowy Mountains Hydro Electric Schemes, which ultimately resulted in the now famous Dutch Australian multinational Lendlease Corporation, led by Dick Dusseldorp (Clark, 2002, p. 5, 23–25; Harfield and Prior, 2010; Schlesinger, 2018; Hoekstra and van Faassen, 2022). This initiative was supported by the Dutch government who developed in the early 1950s a policy of financing and sending prefab houses to overseas emigration destinations, in addition to their policy to solve their own domestic housing issues. In researching the specific files, it becomes clear that this policy was based on reports from Dutch emigration attaches abroad. Thus, we can conclude that the Dutch emigration attaches in Australia converted the complaints recorded on the emigrant cards into a more general policy issue on housing, leading the Dutch government to react with formulating new policy lines (NL-HaNA, 2.15.68, inv.nr. 842, esp. 1385).

Further research on the housing policy leads to the conclusion that the questions about the Building Societies (and Housing Committees) on the cards from the 1960's onwards must in turn be understood as a reflection of a follow up of the “prefab phase” of the housing-policy-abroad, developed by the Dutch government from 1954 and implemented from 1959 till 1975. In order to create a new incentive for emigration to Australia, the Dutch Government designed a policy in four consecutive steps in which money was provided by the Development Loan Fund, Australian Banks and later by Dutch institutional investors. They lend money to so-called Dutch(-Australian) Building Societies, which in turn made it possible for Dutch migrants to borrow money on low interest rates to buy newly built houses (NL-HaNa, 2.15.68, inv.nrs 1262–1265). There even seems to be a closer connection with the Dutch initiated real estate business in Australia, although the exact relations require further investigation.

Both examples leads to the conclusion that the card system was not only a one way monitoring or surveillance device, but that it was a constant form of systemic interaction with input and feedback loops between migrants' experiences abroad (e.g., complaints about housing in camps and hostels to the emigration attaches) and policymaking in the homeland (sending prefab houses for migrants, followed by financial incentives for building activities in Australia), in order to reduce the rate of return migration.

Although we now have a rather good insight in the intention and the focus of this registration system as a policy instrument, this still leaves the question about the exact scope of the registration, what is hidden or missing. Summarizing our previous institutional research, we know that the phase of selection consisted of a pre-selection process (Figure 3), in the Netherlands carried out by the private organizations mentioned above. These organizations also left archival collections and card systems. The question arises if and how these index systems are related to “our” registration system. While the mix of manuscript and typewriting makes analyzing the information on the cards still difficult, the card models (prototypes and pre-printed) can be read by OCR. In this way of distant reading, we could get a complete overview of all card models in the registration system. Once again, we complemented this by close reading cards and connecting them to policy files. This mixed methods approach of close and distant reading allowed us to conclude that the file reference numbers on “our” registration system (ref. nr. A/920/41988) formed the linchpin between the pre-selection files (ref. nr. A/920) kept in the private organizations in the Netherlands and the application files (ref.nr. 41988), now preserved in the National Archives Australia (Faassen and Oprel, 2020, Figure 10). Our registration system literally contains the master cards (stamkaart) on the migrants' application files.

Combining the fact that there are several information models of the master card and that not all master cards actually have a reference file number, revealed that cards also could be filled in Australia after arrival. These migrants somehow have been able to “avoid” the selection procedures. This can be explained partially by departures in the late 1940s, early 1950s (before this selection procedure was perfected or because they departed from other places like the ex-servicemen serving in the Netherlands East Indies) but also by migrants who were not the primary target of the policymakers, the more expat-like migrants from companies or industry. Thus, there has been a hybridity in using the migrant registration system. Another conclusion that can be drawn from this exercise is that pre-selection also means that there are dropouts before migration, in other words, aspiring migrants who never left for whatever reasons. Summing up: the master cards registration system gives information on those who went, but this information can range from very summary to very extensive, it can contain more hidden information on non-targeted migrants or on return migrants and it contains no information on migrants who did not pass the selection procedures.

In the next section, we will elaborate how until today these policies have resulted in making some migrants invisible, and others iconic in the archival collections and the storytelling and historiography based on these collections.

In many ways, Adri Zevenbergen has become one of the most iconic migrants of the Dutch-Australian migration. This was the intention of the authorities, both the Dutch and the Australian, that singled her out as the 100,000th migrant and carefully orchestrated and documented her migration (NL-HaNA, 2.15.68, inv.nr. 1400). She got a lot of media coverage in both countries and both the Dutch and the Australian national archives preserved a lot of (identical!) photos from Adri Zevenbergen. They show her in the Dutch village of Abbebroek, with a windmill and a sixteenth century church, where she lived among people “who still wore clogs” according to the captions—to show that migration to Australia means entering a modernized world, to the migration travel that started with a trunk imprinted with “100,000 migrant,” and the ship Johan van Oldenbarnevelt where she had a pleasant travel to her arrival in Australia. There she was offered the keys to a brand-new house in the suburbs of Geelong, near Melbourne. Her husband was offered a job on the Shell refineries in Australia. Her selection as the 100.000th migrant was in line with the governmental policies to stimulate emigration. As was the case with the 50.000th emigrant, again a woman was selected, to persuade Dutch “housewives,” who—in the eyes of the emigration authorities were more vulnerable to homesickness—to emigrate as well.

A propaganda subject, her migration was anything but typical, if only because most Dutch-Australian migrants had trouble finding suitable work and housing, as was explained above. Nowadays, in both Australia and the Netherlands Zevenbergen has disappeared from the collective memory, leaving the Dutch Australian community confused about their invisibility. But when this emigration wave was commemorated during a public diplomacy visit of the Dutch King Willem Alexander and his wife in 2016, the now partially digitized archives showed Zevenbergen once again as a typical Dutch-Australian migrant. For a Dutch documentary in 2018 even her thoroughly Australianised son Addo, who did not speak Dutch anymore, was interviewed and reflected on his mother's celebrity (Omroep Max, Documentary Vaarwel Nederland, 2018, destination Australia 7649080; images NED-fotoarchief, 0833 + 0834. NAA: A12111, 1/1958/4/39 barcode 7529953, 1/1958/4/70 barcode 7529984, 1/1958/4/45, 1/1959/13/22; A2478, Zevenbergen C).

On the same voyage as Adri Zevenbergen and her family on the migrant ship Johan van Oldenbarnevelt were a group of 37 Moluccans who had earlier migrated to The Netherlands as stowaways, regretting their previous choice of Indonesian citizenship after the decolonization wars (Eijl, 2012). They were evicted from The Netherlands and forcefully repatriated to Indonesia in a separate section on the ship that had been constructed especially for them (NL-HaNA, 2.15.68, inv.nr. 1400). In the Netherlands, there was a lot of protest against the eviction of these young men who were former Dutch after all. Like Zevenbergen, these 37 stowaways were emigrants, and they traveled on the same ship, though not to the same destination. The stories of emigrants and stowaways normally do not come together because they are in different ministerial collections and even if emigration and politics of eviction coincided, their connection is only revealed by connecting the separate collections.

These two stories of the passengers on a same journey aboard the Johan van Oldenbarnevelt illustrate some of the determinants for the visibility of migrants and the role of cultural heritage institutions and digitization. Cultural heritage institutions focus on storytelling and claim to tell the story of historical events and groups of people by highlighting the story of individuals. While this makes a historical phenomenon come alive, it is from the perspective of an individual who comes to stand for the whole phenomenon. In this way, iconic migrants are created. Digitization usually reinforces this, as the cultural heritage objects of these iconic migrants are prioritized in digitization efforts.

While most migrant cultural heritage materials are not digitized, archives tend to prioritize digitisation of the kind of registrations systems we used in our project and which can be found worldwide (Faassen and Oprel, 2020). They give an overview of many migrant names and are usually systematic in contrast to policy and individual case files that are patchy and often disorganized. Australian archival policy also tends to prioritize the digitization of passenger lists, which also consist of long lists of names of migrants, disembarkation schemes and sometimes even information on individual migrants or migrants' groups, traveling under the same scheme. These lists can be very helpful in giving invisible migrants (or their children) more grip on their own history, as we figured out in several pilots done by interns on the project. When migrants cannot be found in our registration system but the ship they traveled on is known, their families who stayed in the Netherlands can at least imagine the events from the journey through the eyes of fellow travelers with more extensive information in our card index system.

As we said above, the schema of the process of filling out cards makes it possible to assess who were not in the cards either. A very special and often forgotten category by researchers are those who were in the selection process for migration but never left for whatever reason. Fortunately, in some cases the personal selection files have survived in other archives such as the Catholic Documentation Centre (KDC) in Nijmegen or the International Institute for Social History in Amsterdam, making it possible to link those who did emigrate and compare them with those who stayed (Kosterman, 2021).

The objectives of the consulates also left their traces in the registration. As they were primarily focused on consular work on the one hand and social assistance on the other, these are the interactions that are most prominent in the registrations. Therefore, they contain lots of information about housing and employment, also the policy targets of the Dutch government. There is very little direct information about health issues, except when they led migrants and their families into social trouble such as poverty or were reasons to remigrate. On the other hand, situations where things got out of hand because migrants socially derailed were common. In some cases, migrants who appeared in the Australian newspapers because they committed a crime, already were trouble in the consular offices. Also, if interventions in family matters threatened or were necessary, these are also reflected on the cards, such as cases when one of a migrant family suffered from mental disorders, causing trouble to his or her family or in cases of (suspicions of) child molesting (Faassen and Oprel, 2020). These traces can be followed to mental hospital registers in Australia where names of Dutch migrants can be found (Faassen, 2014b).

The consular work itself left trails too, usually if migrants or remigrants needed passport renewal in order to travel. This sometimes (lightly) documents the migrants who would not appear in the registration because they were sent by their companies. For other collections, similar remarks can be made, but they all tend to highlight different aspects of migrants, therefore connecting them leads to a more complete view of migrants. But because they are dispersed, this is only possible with a cross collection and cross institutional approach. As it is, institutional policies, archiving practices and institutional collection policies such as the destruction of executive files all contribute to the presence or absence and visibility or invisibility of migrants and migrant groups in the archives. And, as we said before, storytelling approaches and selective digitization policies tend to single out the most visible migrants and unconsciously accentuate past policies.

On the other hand, the creation of alternative collections by using social media, creates even more possibilities to better represent the unheard voices and make migrants visible in the existing heritage when combined with connected collections. On social media there are often calls from emigrants who are looking for their family or lost friends. In a small pilot we found out for several cases that the registration system does contain rather elaborate cards and sometimes even a whole file (with photos at the time of immigration) in the Australian immigration files. Perhaps social media would yield more information, but that depends on whether the question reaches the right people. In addition, it is doubtful whether these contain information from the archives.

A last Dutch-Australian emigrant may serve to highlight some other aspects of iconicity. This is Dick Dusseldorp (1918–2000), mentioned above. He was an industrial tycoon who became rich, famous and powerful in Australia, first as a builder and later as the founder and president of the Lend-Lease company that still is a world-wide building and financing concern. He is still famous in Australia, but unknown in the Netherlands. He is an icon but not an important figure in most of the collections of either the Australian or Dutch archives. As he was sent to Australia by his Utrecht Building Company Bredero for the prefab housing project, his migration was not recorded in the registration system in the first instance. However, he was registered once his passport had to be renewed. Due to his public appearances and the high-profile construction activities, his story can be reconstructed and added to the data backbone using digitized press archives, such as newspapers and even YouTube films.

Digitization and digital methods can make important contributions to the analysis of collections and to expose and even overcome policy biases. However, this potential is complicated when digitisation and digital methods tend to decontextualise archive material and contribute new distortions and biases. Moreover, if digital methods are applied within the confinements of a single collection, they cannot contribute a more encompassing picture that results from combining the many facets in other public and private heritage collections. A more balanced use depends on the connection of different collections and using digital methods as an extension of methods of source criticism. Only if they are employed in this way, it becomes possible to assess the pervasiveness of policy in holdings of archives, other collecting institutions and private resources alike. Migration history is par excellence suited to show the way. The dispersed nature of migration heritage not only implies that it is important to connect collections to get an integral view of migration history and more grip on the variety of migrants, but it also makes it clear that there are fundamentally different views that are codified in collections.

We exemplified this with our study of Dutch-Australian migration by using a registration system as a connecting device between collections and by scrutinizing the impact of policy on this system. Our analysis depended on the realization that the registration cards were an instrument of the registering authorities and their own policies were much more influential than the characteristics of the migrants. While computer vision was instrumental in measuring the information distribution in the card system, further analysis was impossible without close reading policy files. This illustrates that for historical research computer assisted methods can provide an important extension of the methodology, but that they are most effective if combined with established methods.

The assessment of the information in the registration cards was established to prevent selection biases in further sampling migrant lives and connecting them to dispersed cultural heritage materials. On the basis of that assessment, we now know that further sampling will not give a selection bias toward specific groups of migrants, but we should include the policies of the emigration authorities in our analysis. This underlines Schrover and Moloneys' statement that it is necessary to acknowledge the interaction between policy and migrants' choices. We can even go one step ahead: only the whole assessment of information revealed that states do use other, more hidden or implicit forms of categorization, like the migration schemes based on economic principles. Thus, researchers should also take into account that there are micro forces such as seemingly “neutral migration schemes” that can influence migrant's life course experiences. Furthermore, in combining close reading (sample) and distant reading (edging) of the cards we are able to conclude that the card system was not only a one-way monitoring device, but that it was a constant form of systemic interaction with input and feedback loops between migrants' experiences abroad and policymaking in the homeland.

Next to that we have presented some iconic migrants as illustrations of what makes migrants visible and invisible in digital cultural heritage collections. Our main point is that visibility is largely determined by a chain of policies on the part of archive creators and curators, both analog and digital. Connecting collections from dispersed institutions add different perspectives to the larger view on migrants. In this way connected digital resources transcend collection limitations and provide more possibilities to make migrants visible, either directly or by providing context.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://github.com/HoekR/MIGRANT/blob/master/results/exploring_data_integration/notebooks/Profiles.ipynb.

MF and RH are collaborators on the project Migrant: they both conducted the research and they both wrote an equal share of this article (MF on the migration history, RH on the digital methodology: both on source criticism). Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Arthur, P., Ensor, J., Faassen, M. van., Hoekstra, R., and Peters, N. (2018). Migrating people, migrating data. Digital approaches to migrant heritage. J. Jap. Assoc. Dig. Human. 3–1, 98–113. doi: 10.17928/jjadh.3.1_98

Blouin, Jr., Francis, X., and Rosenberg, W. G. (2011). “On the Intersections of Archives and History,” in Processing the Past: Contesting Authorities in History and the Archives. Oxford Academic. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199740543.003.0001 (accessed August 5, 2022)

Chassanoff, A. (2013). Historians and the use of primary source materials in the digital age. Am. Arch. 76, 458–480. doi: 10.17723/aarc.76.2.lh76217m2m376n28

Clark, L. (2002). Finding a Common Interest. The Story of Dick Dusseldorp and Lend Lease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coburn, J. (2021). Defending the digital: awareness of digital selectivity in historical research practice. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 53, 398–410. doi: 10.1177/0961000620918647

Coté, J. (2010). The indisch Dutch in post-was Australia. Low Countries J. Soc. Econ. Hist. 7, 103–125. doi: 10.18352/tseg.378

Devereaux, S. (1996). The city and the sessions paper: “Public Justice” in London, 1770-1800. J. Br. Stud. 35, 466–503. doi: 10.1086/386119

Eysbertse, D. M. (1997). Where Waters Meet. Bonegilla, the Dutch Migrant Experience in Australia. Erasmus Foundation North Brighton (VIC): Melbourne, VIC.

Faassen, M. van. (2014a). Polder en Emigratie. Het Nederlandse Emigratiebestel in Internationaal Perspectief 1945-1967. The Hague: Huygens ING.

Faassen, M. van. (2014b). Emigratie 1945-1967. Available online at: http://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/emigratie (accessed March 30, 2022).

Faassen, M. van., and Hoekstra, R. (2015). “Tijdelijke migratie als bewust beleid. De Nederlands-Australische Youth Programs en Working Holiday Schemes,” in Presentation CGM (The Hague). Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marijke-Van-Faassen (accessed August 5, 2022).

Faassen, M., and van. Hoekstra, R. (forthcoming). “Storytelling, identity digitizing heritage,” in Digitising Heritage. TransOceanic Encounters Between Australia Europe, eds C. Wergin S. Affeldt (Heidelberg: KEMTE, Heidelberg University Publishing).

Faassen, M. van., and Oprel, M. (2020). “Paper trails to private lives. The performative power of card indexes through time and space,” in Information and Power in History: Towards a Global Approach, eds I. Nijenhuis, M. van Faassen, R. Sluijter, J. Gijsenbergh, and W. de Jong (Routledge), 254–274.

Gilliland, A. J., McKemmish, S., and Lau, A. J. (2017). Research in the Archival Multiverse. Clayton: Monash University Publishing.

Harfield, S., and Prior, J. H. (2010). “A bright new suburbia? GJ Dusseldorp and the development of the Kingsdene Estate,” in Green Fields, Brown Fields,New Fields: Proceedings of the 10th Australasian Urban History, Planning History Conference, eds D. Nichols, A. Hurlimann, C. Mouat and S. Pascoe (Melbourne, VIC: University of Melbourne), 7–10, 207–220.

Hauswedell, T., Nyhan, J., Beals, M. H., Terras, M., and Bell, E. (2020). Of global reach yet of situated contexts: an examination of the implicit and explicit selection criteria that shape digital archives of historical newspapers. Arch. Sci. 20, 139–165. doi: 10.1007/s10502-020-09332-1

Hoekstra, R. (2021). Summary Analysis Notebook. Available online at: https://github.com/HoekR/MIGRANT/blob/master/results/exploring_data_integration/notebooks/Profiles.ipynb (accessed August 10, 2022).

Hoekstra, R., and Koolen, M. (2019). Data scopes for digital history research. Historical Methods J. Quan. Interdiscip. History 52, 79–94. doi: 10.1080/01615440.2018.1484676

Hoekstra, R., Koolen, M., and van Faassen, M. (2021). Vested authorities, emergent brokers and user archivists: power and legitimacy in information provision. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. doi: 10.1145/3484481

Hoekstra, R., and van Faassen, M. (2022). “Hoog-Catharijne en het Sydney Opera House,” in Nog meer Wereldgeschiedenis van Nederland, eds L. Heerma van Voss, N. Bouras, M. t Hart, M. van der Heijden, and L. Lucassen (Amsterdam: Ambo-Anthos).

Horne, S. (2011). The Invisible Immigrants: Dutch Migrants in South Australia. An arts Internship Project for the Migration Museum. Adelaide: University of Adelaide. Available online at: https://apo.org.au/node/74461 (accessed August 09, 2022).

Jeurgens, C., and Karabinos, M. (2020). Paradoxes of curating colonial memory. Arch. Sci. 20, 199–220. doi: 10.1007/s10502-020-09334-z

Ketelaar, E. (2017). “Archival turns and returns,” in 2017 Research in the Archival Multiverse, eds A. J. Gilliland, S. McKemmish, and A. J. Lau (Clayton: Monash University Publishing), 228–269.

Koolen, M., Hoekstra, R., Nijenhuis, I., Sluijter, R., van Gelder, E., van Koert, R., et al. (2020). “Modelling resolutions of the dutch states general for digital historical research,” in Collect and Connect: Archives and Collections in a Digital Age 2020. Proceedings of the International Conference Collect and Connect: Archives and Collections in a Digital Age (Leiden). Available online at: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2810/paper4.pdf (accessed July 5, 2022).

Kosterman, F. (2021). “Op zoek naar een beter leven. Gecombineerde datasets brengen levensgeschiedenissen van Nederlandse migranten naar Australië in kaart,” in Impressie, Tijdschrift voor Katholiek Erfgoed, 18–22. Available online at: https://www.ru.nl/kdc/weten/impressie-nieuwsbrief-kdc/ (accessed August 5, 2022).

Leurs, K. (2021). “Personal digital archives: doing historical migration research in the digital era,” in Doing Historical Research on Migration in the Digital Age: Theories, Concepts and Methods. Luxemburg: IMISCOE Conference 2021.

Lucassen, J. M. W. G., and Lucassen, L. A. C. J. (1999). “Introduction,” in Migration, Migration History, History: Old Paradigms and New Perspectives (Bern; New York, NY: Peter Lang), 9–38.

McElreath, R. (2020). Statistical Rethinking: A Bayesian Course With Examples in R and Stan. London: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

McKemmish, S. (2017). “Recordkeeping in the continuum: an australiantradition,” in Research in the Archival Multiverse, eds A. J. Gilliland, S. McKemmish, and A. J. Lau (Clayton: Monash University Publishing), 122–161.

Nationaal Archief (2022). Proces van Digitalisering. Available online at: https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/archiveren/kennisbank/proces-van-digitalisering (accessed July 5, 2022).

National Archives of Australia (2022). Corporate Plan 2017-18 to 2020-21. Available online at: https://www.naa.gov.au/about-us/our-organisation/accountability-and-reporting/our-corporate-plans/corporate-plan-2017-18-2020-21 (accessed July 5, 2022).

Nauta, G. J., van den Heuvel, W., and Teunisse, S. (2017). D4.4. Report on Revision ENUMERATE Core Survey 4. Europeana/DEN. Available online at: https://www.den.nl/uploads/5c6a8684b3862327a358fccaf100d59668eedf1f7f449.pdf (accessed March 30, 2022).

Nyirubugara, O. (2012). Surfing the Past: Digital Learners in the History Class. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Oberbichler, S., and Pfanzelter, E. (2021). Topic-specific corpus building: a step towards a representative newspaper corpus on the topic of return migration using text mining methods. J. Dig. History. jdh001. Available online at: https://journalofdigitalhistory.org/en/article/4yxHGiqXYRbX (accessed August 9, 2022)

Omroep Max. (2018). Documentary. Available online at: https://www.maxvandaag.nl/programmas/tv/vaarwel-nederland/australie/POW_03876992/, 25:43 (accessed March, 2022).

Peters, N. (2001). “Milk & honey - but no gold,” in Postwar Migration to Western Australia Between 1945–1964 (Perth, WA: UWA Publishing).

Peters, N. (2010). Aanpassen and invisibility: being Dutch in post-war Australia. Low Countries J. Soc. Econ. Hist. 7, 82–102. doi: 10.18352/tseg.377

Schlesinger, L. (2018). Lendlease's Dick Dusseldorp: From Nazi Labour Camp to Listed Giant. Financial Review (september 2018). Available online at https://www.afr.com/property/residential/lendleases-dick-dusseldorp-from-nazi-labour-camp-to-listed-giant-20180702-h1252g (accessed August 8, 2022).

Schrover, M., and Moloney, D. M. (2013). Gender, Migration and Categorization. Making Distinctions Between Migrants in Western Countries 1945-2010. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Schrover, M., and van Faassen, M. (2010). Invisibility and selectivity. Introduction to the special issue on Dutch overseas migration in the nineteenth and twentieth century. Low Countries J. Soc. Econ. Hist. 7, 3–31. doi: 10.18352/tseg.374

Shoemaker, R. B. (2008). The Old Bailey proceedings and the representation of crime and criminal justice in eighteenth-century London. J. Br. Stud. 47, 559–580. doi: 10.1086/587722

Smith, A. L. (2003). “Introduction,” in Europe's Invisible Migrants, ed A. L. Smith (Amsterdam: Amsterdam AUP), 9–33.

Stoler, A. L. (2002). “Colonial archives and the arts of governance: on the content in the form,” in Refiguring the Archive, eds C. Hamilton, V. Harris, J. Taylor, M. Pickover, G. Reid, and R. Saleh (Dordrecht: Springer), 83–102.

Tames, I. (2022). Digitized Archives and Stateless People: New Windows on Those Usually Invisible. Available online at: https://medium.com/@ismee.tames/digitized-archives-and-stateless-people-new-windows-on-those-usually-invisible-c85357c3c1bc (accessed July 5, 2022).

Torpey, J. (1998). Coming and going: on the state monopolization of the legitimate ‘means of movement'. Soc. Theory 16, 239–259. doi: 10.1111/0735-2751.00055

Upward, F., Reed, B., Oliver, G., and Evans, J. (2018). Recordkeeping Informatics for a Networked Age. Clayton, NC: Monash University Publishing.

Walcker-Birckhead, W. (1988). Dutch identity and assimilation in Australia: an interpretative approach [Dissertation]. Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia.

Willems, W. H. (2003). “No sheltering sky: migrant identities of Dutch nationals from Indonesia,” in Recalling the Indies. Colonial Culture & Postcolonial Identities, Eds J. Coté and L. Westerbeek (Amsterdam: Aksant), 33–61.

Keywords: migrant history, digital methods, source criticism, computer vision, connecting heritage

Citation: Faassen Mv and Hoekstra R (2022) Migrant visibility: Digitization and heritage policies. Front. Hum. Dyn. 4:908456. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2022.908456

Received: 30 March 2022; Accepted: 11 July 2022;

Published: 31 August 2022.

Edited by:

Machteld Venken, University of Luxembourg/European University Institute, LuxembourgReviewed by:

Sarah Oberbichler, University of Innsbruck, AustriaCopyright © 2022 Faassen and Hoekstra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marijke van Faassen, bWFyaWprZS52YW4uZmFhc3NlbkBodXlnZW5zLmtuYXcubmw=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.