- Department of Criminal Law, Law School, Tilburg University, Tilburg, Netherlands

Nearly 4 million Syrian refugees, including more than 1.8 million Syrian children, fled to Turkey during the Syrian war, where they face many challenges to rebuild their lives. They are confronted with restrictions on their residence status and access to the labor market, limiting their formal employment opportunities. Poverty and labor exploitation are widespread consequences, and to make ends meet, children are driven into the workforce. In Turkey, child labor among Turkish nationals is also widespread as follows from the Turkish national child labor survey from 2019, creating a fertile ground for Syrian children to take up work. Although child labor among the Syrian refugee population is gaining increasing attention among scholars and humanitarian actors, knowledge about its extent or characteristics remains limited. Drawing on a survey conducted in late 2020, this paper contributes to a deeper and more numerically based understanding of the current situation of Syrian minor workers in Turkey. The quantitative results of our research are compared with the Turkish national child labor survey, highlighting the differences and commonalities between Syrian and Turkish children working in the country and looking into the impact of the lack of permanent residency on the prevalence of child labor. Our findings suggest that Syrian children enter the labor force at a younger age and have less access to education while working very long hours and earning low wages. The study thus demonstrates the specific vulnerabilities of Syrian children to labor exploitation.

Introduction

Since the outbreak of war in Syria in 2011, more than 6.6 million Syrians have been forced to leave their country in search of safety and international protection (UNHCR, 2021). As a neighboring state, Turkey served as a transit and destination country for many of these refugees, offering a pathway to Europe (Simşek, 2017). At the same time and especially after the EU-Turkey statement in 2016, around 3.6 million Syrians stayed in Turkey, where they have now been for many years and have rebuilt their lives (Kaya, 2020; Simşek, 2020). More than 1.8 million Syrian children have come to Turkey since 2011. Although safe from war, the new life in Turkey brings its insecurities and vulnerabilities, and restrictions on refugees' residence status and labor rights limit their employment opportunities (Baban et al., 2017; Kaya, 2020). Consequently, poverty and labor exploitation are a widespread reality—not only for adults but also for children (Yalçin, 2016). As many families struggle to make ends meet, children are increasingly relied upon to contribute to the household income. Therefore, child labor1 has become a widely established phenomenon among Syrian refugees in Turkey (Yalçin, 2016). However, knowledge about the extent or characteristics of the Syrian child labor force is limited. While a recent survey by the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) provided valuable numbers on child labor among Turkish children, it did not cover children with Syrian nationality (Özbek, 2020). There are no official data on Syrian children in the workforce, nor their enrolment in Turkish schools (Lordoglu and Aslan, 2019). In recent years, different studies were conducted on child labor among Syrian refugees in Turkey (Yalçin, 2016; Lordoglu and Aslan, 2019) or on the difficulties for Syrian children in obtaining an education (Uyan-Semerci and Erdogan, 2018). These studies were mostly based on qualitative data, and statistical analyses on the matter remain scarce. This paper aims to contribute to a deeper and more numerically based understanding of the current situation of Syrian minor workers in Turkey. It discusses the characteristics and conditions of child labor among Syrian refugees in Turkey, drawing on a survey conducted in late 2020. Hereby, our quantitative results are compared with the national child labor survey from 2019, highlighting the differences and commonalities between child labor among Syrian and Turkish children in the country, and demonstrating the specific vulnerabilities of Syrian children to labor exploitation.

After a brief discussion of the data and methodology, the analysis starts by examining structural factors that explain the prevalence of child labor among Syrian refugees in Turkey. For this, restrictions on their residence status and labor rights are analyzed, and the context of the Turkish labor market and education system is taken into closer consideration. This section illustrates how child labor is a major cause of concern among the refugee population, but beyond that also a problem deeply rooted in Turkish society. In the next step, the legal framework on child labor in Turkey is explored. Hereby, relevant legal provisions for the combat of child labor both on the international and domestic level are discussed, while also considering the limitations of the legal framework that add to the persistence of child labor in Turkey. Against this background, results from the 2019 national survey on child labor in Turkey are compared to our survey. The differences and commonalities between child labor among Syrian and Turkish children are discussed, touching upon the age of the working children, the education rate, the most common work sectors, and the reasons for child labor. In a final step, we present additional characteristics of child labor among Syrian refugees that could not be compared with the Turkish child labor force due to the different thematic coverage of the two surveys, but which provide a deeper understanding of the realities of life for Syrian underage workers in Turkey.

Data and Methodology

This analysis is based on quantitative data collected in collaboration with Upinion2. Through an online network among Syrian refugees in Turkey using mobile technology and social media, we had real-time conversations via messaging apps. In this way, 684 Syrian refugees residing in Turkey participated in an online survey, where they were asked about their knowledge of the subject of child labor in Turkey. For ethical reasons and because we wanted to include questions related to the broader context of child labor, we only selected respondents above the age of 18 who had a working child within their household, or who knew of a working child. If the respondent stated that he or she has one working child within the household, the respondent was asked about this particular child. In the case of several working children within the household, the respondent was asked about the youngest working child. If a respondent indicated that he or she knew about a working child outside his or her household, the respondent was asked about that respective child.

According to this design of the survey, there are two groups of respondents with knowledge of child labor: the ones with working children in their household and the ones with knowledge of child labor outside their household. To a large extent, the two groups were asked the same questions. However, the respondents with working children within their household were asked some additional questions compared to the other group. They were expected to have some specific knowledge based on the close relationship to the child, for example regarding wages and the impact of having a working child in the household. Another consequence of the survey design is that, in addition to information on children within the respondent's household, information on child labor is collected indirectly through respondents who are not themselves affected by child labor, but who provide information on the issue. The questions were thus directed at the respondents and addressed the working children. Accordingly, the count of observations is indicated in “number of respondents” and indicates whether it includes only respondents with working children in their households, only respondents that know of child labor outside their households, or both.

This data collection method and the collaboration with Upinion brought great advantages to the study. First and foremost, access to the target population was enormously facilitated as Upinion had already built an online community with Syrian refugees in Turkey. Hereby, the fact that the participants had already been in contact with Upinion before was perceived to reduce reservations about the survey and to increase the response rate. Thus, in a short duration of 8 days, a sample with 684 respondents could be generated. Also, as the data could be collected online, there was no need for physical presence in the field, which would have been very challenging at the time due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, this study was confronted with several limitations and challenges. For one thing, the applied data collection method could only reach people with access to mobile technologies. This can result in the exclusion of those people lacking basic infrastructure or affected by severe poverty, whose voices would be even more important to hear. Furthermore, as the data collection took place online, strict measures to ensure data security had to be taken. For this purpose, a data management plan was established and ethical clearance for the research was received. To further comply with the do no harm principle and to make the survey as mutually beneficial an experience as possible, a flyer with information from (I)NGOs who have programs on child protection was built into the conversation and shared with the participants. It included vocational trainings and educational programs. Finally, the respondents received some airtime credit to their phones as a token of appreciation.

Understanding the Prevalence of Child Labor Among the Syrian Refugee Population

Restrictions on Residence Status and Labor Rights

Since 2011, more than 3.6 million Syrian refugees have settled in Turkey (Erdogan and Uyan Semerci, 2018). At first, Turkish authorities pursued an “open door” policy, where Syrian refugees were generally granted to stay in the country, although as “guests” and without any formal legal status (Özden, 2013; Ahmet and Simşek, 2016; Koca, 2016; Kaya, 2020). Although Turkey is a party to the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, it only signed them with a geographic limitation, according to which full refugee status can only be granted to Europeans (Özden, 2013; Kaya, 2020)3. In 2014, the Turkish government introduced a new Law on Foreigners and International Protection (LFIP, No. 6458), where the conditions for international protection were redefined (Ahmet and Simşek, 2016; Kaya, 2020) and the geographical limitation to full refugee status was upheld (Koca, 2016). Also, in 2014 Turkey introduced the Temporary Protection Regulation based on the LFIP. Consequently, most Syrians in Turkey are now registered under the formal status of “temporary protection,” and not as “refugees” (Koca, 2016)4, and they do not enjoy the rights set forth in the Refugee Convention (Simşek, 2017). The status of temporary protection, however, does not grant Syrians a regular residence permit envisaged for legal stay in Turkey, but exempts them from the residence permit requirement (AIDA, 2021a, see art. 20(1)(g) LFIP, citing art. 83 LFIP; Kaya, 2020). While this exemption rule also authorizes legal stay in Turkey, it only does so for an undefined duration until terminated by the authorities, creating a situation of limbo and unpredictability. Furthermore, this status cannot lead to a regular long-term residence, and the time spent in Turkey under this status cannot contribute toward the attainment of the 5-year legal residence requirement for naturalization (AIDA, 2021a). Following the implementation of the Temporary Protection Regulation, the Turkish government announced in July 2016 that Syrian refugees could eventually receive Turkish citizenship and work permits (Ahmet and Simşek, 2016, p. 62; Kaya, 2020, p. 35). So far, this has not been put into established practice, and naturalization for Syrians under temporary protection in Turkey is mostly granted only under exceptional circumstances, for example, for Syrians with economic and cultural capital or through marriage to a Turkish citizen (Kaya, 2020; AIDA, 2021b). In the same year, Turkey adopted the Regulation on Work Permits for Foreigners under Temporary Protection (AIDA, 2021c), based on which it became possible for Syrian refugees who have been in the country for more than 6 months to apply for work permits (art. 5). Obtaining such permits, however, comes with several challenges: It is only the employers who can apply for them, and the applicants must fulfill certain residency, registration, and health requirements (Ahmet and Simşek, 2016). Also, the number of foreigners under temporary protection in a given workplace may not exceed 10 percent of the number of Turkish employees, and employers must pay them at least the official minimum wage (Ahmet and Simşek, 2016, p. 64). Because of these challenges, many Syrian refugees have not obtained such permits: As of March 2019, it was only about 1.5 percent of the 2.2 million working-age Syrians in Turkey who had received official work permits (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2019). The rest continues to work in the informal labor market in low-paid positions (Yalçin, 2016; Simşek, 2017).

Turkey's approach to dealing with its Syrian refugee population has been further determined by the EU-Turkey statement, which was signed in 2016. The agreement constitutes a statement of cooperation between the EU member states and Turkey to control and reduce the number of migrants from Turkey arriving in Europe (Simşek, 2017, p. 162). More specifically, it includes that all irregular migrants crossing the sea from Turkey to the Greek islands will be returned to Turkey. For every Syrian being returned, another Syrian will be resettled from Turkey to the EU (Haferlach and Kurban, 2017, p. 87)5. The EU-Turkey statement has been subject to severe and repeated criticism by scholars and humanitarian actors, such as Human Rights Watch or Amnesty International, emphasizing the negative repercussions it has on the protection of Syrian refugees (Haferlach and Kurban, 2017, p. 67). Hereby, one of the main concerns lies in the de facto recognition of Turkey as a “safe third country” (Simşek, 2017, p. 163; Haferlach and Kurban, 2017, p. 86). Since the statement came into effect, the number of sea crossings from Turkey to the Greek islands has drastically decreased (Simşek, 2017, p. 164), although many continue to risk their lives while trying to do so. For those Syrians still in Turkey, this means that the chances to reach Europe have diminished even further.

Syrian Children in the Informal Labor Market in Turkey

More than half of the Syrian refugees in Turkey are under the age of 18 (Erdogan and Uyan Semerci, 2018). Many of these children are either involved in child labor or vulnerable to becoming minor workers (Lordoglu and Aslan, 2019). In order to understand the risk of them engaging in child labor, one first needs to address the broader context in Turkey, especially the conditions of the labor market and the education system. Turkey features one of the highest informal economy rates among the OECD countries (Yalçin, 2016, p. 92) and ranks the seventh place among the OECD countries with the highest child poverty rates (OECD, 2021). Child labor is deeply rooted in Turkish society and results from a variety of societal and economic factors. These include poverty, a distorted income distribution, limited employment opportunities in the formal labor market, a lack of social protection mechanisms, population growth, urban migration, and low levels of education (Akin, 2009, p. 55). Against this background, scholars see the informal and insecure nature of the labor market as a fertile ground for child labor, also among Syrian refugees (Yalçin, 2016, p. 92). In addition, factors that specifically apply to the refugee population include difficulties in acquiring employment permits and obstacles in obtaining an education. For instance, many Syrian refugees face obstacles when enrolling their children in the public school system (Yalçin, 2016). These arise mainly due to lacking regulatory procedures, language barriers, or insufficient infrastructure (Ahmet and Simşek, 2016, p. 66). Consequently, many Syrian children in Turkey do not go to school,6 which increases their chances of becoming minor workers.

Child labor among Syrian refugees in Turkey can thus be viewed as a multilayered problem (Yalçin, 2016, p. 96; Thévenon and Edmonds, 2019). Considering that both Turkish and Syrian children are heavily affected by this issue, it is crucial to approach it as an established risk for exploitation in the broader context of the labor market and social inequality in Turkey (Yalçin, 2016, p. 90). It would be inadequate to discuss the issue of child labor among Syrian refugees as an isolated problem among this group that has only arisen due to the increased entry into the country after the war in Syria (Yalçin, 2016, p. 90). Child labor in Turkey stems from multifaceted, structural factors and labor market-immanent characteristics and has been a problem long before the arrival of Syrian refugees in the last decade (Lordoglu and Aslan, 2019, p. 59). Nevertheless, it needs to be recognized that Syrian families are confronted with additional burdens and insecurities compared to Turkish nationals and that Syrian children are particularly vulnerable to being exploited in the informal labor market.

The Legal Framework on Child Labor in Turkey

Given the widespread prevalence of child labor in Turkey, this section explores and questions the legal framework in place to combat child labor in the country. Since the 1990s—at a time when Turkey had the largest population of working children in Europe according to estimations of the Council of Europe (Bakirci, 2002, p. 55) –, several measures to combat child labor have been introduced. In 1994, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) was ratified, and its core principles have been integrated into national legislation (Yalçin, 2016). Regarding child labor, art. 32 CRC states that every child should “be protected from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child's education, or to be harmful to the child's health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.” In addition, Turkey signed the ILO Convention 138 regarding the Minimum Age of Workers in 1998, where the minimum age to work has been set at 15 years of age in general, and 18 years of age for hazardous work (Ozgun and Gungordu, 2021). In 2001, Turkey signed the ILO Convention 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, defining it in art. 3 para. 1 lit. d as “work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety or morals of children” (Yalçin, 2016; Kanun and Kayaoglu, 2019). These three conventions constitute the main international legal framework regarding child labor (Ozgun and Gungordu, 2021). Through the ratification of these international treaties, Turkey committed itself to introducing policies and legislation to combat child labor, guaranteeing the enshrined rights to all children under its jurisdiction (see for example art. 2 CRC), and thus covering not only children with Turkish citizenship but also Syrian children living in Turkey.

In addition to these international legal norms, the national legal framework also holds several provisions dedicated to the combat of child labor. Hereby, the Turkish Constitution lays out the legal basis prohibiting work that is unsuited to one's age (art. 50 para. 1) and further states that children must enjoy special protection with regard to working conditions (art. 50 para. 2) (Bakirci, 2002; Akin, 2009). Furthermore, art. 41 of the Constitution sets forth that every child has the right to protection and care (para. 3) and that the state shall protect children against all kinds of abuse and violence (para. 4) (Yalçin, 2016, p. 96). Based on these constitutional provisions, several Turkish laws address issues linked to child labor, including the Child Protection Law (No. 5395), the Criminal (No. 5237) and Civil (No. 4721) Codes, the Labor Act (No. 4857), the General Hygiene Law (No. 1593), the Occupational Health and Safety Act (No. 6331), the Code of Obligations (No. 6098), and the Trade Union Act (Nr. 6356) (Bakirci, 2002; Yalçin, 2016). Furthermore, there are various regulations on the decree level, for example, the Regulation on Heavy and Dangerous Work or the Ordinance on the Procedures and Principles of Employing Child and Young Workers, which sets out the principles for work involving children to avoid their economic exploitation. In light of this variety of relevant legal sources, different issues related to child labor such as minimum age, working conditions, or compulsory education are regulated separately and across different laws and regulations, as the next sections will demonstrate.

Provisions on Compulsory Education and the Minimum Age for Work

According to the Turkish Constitution, every child in Turkey has the right to education (art. 42 para. 1), whereby primary education is both compulsory and free of charge for all citizens (art. 42 para. 5) (Akin, 2009, p. 57). This is not in line with art. 28 of the CRC which requires primary education to be compulsory and available free of charge for all children within their jurisdiction. However, art. 90 para. 5 of the Turkish Constitution provides for the hierarchy of norms and determines that “International agreements duly put into effect have the force of law. [...] In the case of a conflict [...] the provisions of international agreements shall prevail.” Thus, in practice, also many Syrian children can attend school in Turkey (Kaya, 2020, p. 49). The duration of compulsory education has been gradually increased, from 5 to 8 years in 1997, and then to 12 years in 2012 (Kanun and Kayaoglu, 2019, p. 1994). This increase in mandatory education has inter alia been delineated as a measure targeted to combat child labor. Regarding the minimum age for work, the Labor Act (No. 4857) prohibits the employment of children who have not completed the age of 15 (art. 71 para. 1). Children 14 years of age may be exempted, provided they are employed in light work that will not adversely affect their physical, mental, and moral development, and which does not conflict with their education—in case they are still attending school (art. 71 para. 1 Labor Act). Also, 16 is the minimum age for arduous or dangerous work (art. 85 para. 1 Labor Act), and children under the age of 18 are prohibited from hazardous work, including underground and underwater work (art. 72 Labor Act), or industrial work at night (art. 73 Labor Act). However, the Labor Act does not cover all types of workers, for example, workers without an employment contract (art. 1), and certain work sectors, such as domestic work (art. 4 para. 1 lit. e), agricultural work in establishments with a maximum of 50 employees (art. 4 para. 1 lit. b), family enterprises (art. 4 para. 1 lit. c and d), and small enterprises employing less than three workers (art. 4 para. 1 lit. i) are excluded. In establishments processing agricultural products (e.g., making cheese, drying fruits, etc.), art. 4 para. 2 lit. c provides for an exception to the exclusion, meaning that even if this work is performed in undertakings having <50 employees, the Labor Act, including its provisions on child labor, applies. As many Syrian minors work in the informal economy and assumingly without an employment contract, a large portion of these minor workers may not be protected by the Labor Act (Bakirci, 2002, p. 61). The General Health Law (No. 1593) covers some work sectors excluded by the Labor Act and prohibits the employment of children under the age of 12 in mining and industrial work (Bakirci, 2002, p. 62). This conflicts with art. 85 para. 1 Labor Act, which sets the minimum age at 16 for such work. Consequently, the Turkish labor legislation contains inconsistent regulations regarding the minimum age for work, depending on the respective law and work sector (Bakirci, 2002, p. 62).

Provisions on Working Hours, Employment Conditions, and Minimum Wage

According to the Labor Act, the working hours for children who completed their basic education and do no longer attend school may not exceed 7 h a day and 35 h per week, whereby this may be increased up to 8 h daily and 40 h per week for children who have completed the age of 15 (art. 71. para. 4) (Akin, 2009, p. 63). For those children still attending school, the maximum working time is 2 h a day and 10 h per week, whereby the work may not take place during school hours (art. 71 para. 5). However, as outlined above, the Labor Act does not cover all workers and work sectors, and situations of child labor are often excluded from these regulations. For those situations which are further covered by the General Health Act, the rule applies that individuals between the ages of 12 and 16 must not work for more than 8 h a day (Bakirci, 2002, p. 63).

Concerning employment conditions, the Turkish constitution establishes a legal foundation by stating that every person is entitled to a healthy environment (art. 56 para. 1) and to have their well-being safeguarded (art. 17 para. 1). The Labor Act further holds in art. 77 that employers must ensure occupational health and safety at the workplace. This includes that employers must inform their employees about any occupational risks and the measures taken against these risks. Additionally, workers under the age of 18 must be examined by a medical practitioner and certified as being fit for the job before starting any employment, and thereafter every 6 months (art. 87 Labor Act). Furthermore, the Occupational Health and Safety Law (No. 6331) also guarantees the safety and health of workers (art. 4), whereby the employers are obliged to take measures against occupational risks (para. 1) and monitor their implementation (para. 2). In contrast to the Labor Act, this law covers all employees regardless of the work sector or the company size, except for domestic services, persons producing goods in their name, the Armed Forces, the Police Department, and certain employees in civil defense services (art. 2), and is thus far more comprehensive (Bilir, 2016, p. 13). Moreover, the Ordinance on the Principles and Procedures for the Employment of Children and Young Persons specifically protects minor workers against every type of occupational risk and obliges employees to ensure their health and safety (art. 5) (Akin, 2009, p. 61).

Regarding the minimum wage, the Turkish Constitution establishes that the state must take the necessary measures to ensure that workers earn a fair wage and that they enjoy social benefits (art. 55) (Bakirci, 2002, p. 64). The Labor Act specifies in art. 39 that the minimum wage for all workers with an employment contract shall be determined every 2 years by the Ministry of Labor and Social security. The minimum monthly wage of 2020 (the year of the data collection) was set at 2,324.70 Turkish lira net and 2,943 Turkish lira gross7. However, as mentioned above, many workers are not covered by the Labor Act, such as children working in the informal sector for example, who are therefore deprived of this right to a minimum wage and other services, despite guarantees in international instruments.

Limitations of the Legal Framework

As of today, there are thus various legal norms anchored in national and international law that serve the combat of child labor in Turkey. Yet in spite of this, the number of children working in exploitative and hazardous circumstances is continuously high, and the working conditions have been reported to be worsening in many respects (Yalçin, 2016; Erdogan and Uyan Semerci, 2018; Lordoglu and Aslan, 2019). Although the legal framework provides some guarantees against child labor, in practice these provisions are not adhered to and leave many gaps, especially because the majority of the children work in the informal labor market. As mentioned above, child labor is a multilayered problem, and prohibition in legislation is only one facet of an effective response. It was also against this background that in 2018, the Turkish Prime Minister officially declared the year to be the “year of battle against child labor” (Erdogan and Uyan Semerci, 2018, p. 193), emphasizing the continuous need for action. One issue that has been found to hinder adequate prevention of child labor lies in the fragmentation and inconsistencies of the regulatory framework, and scholars argue that child labor constitutes a legislative gray area (Yalçin, 2016; Ozgun and Gungordu, 2021). Hereby, the fact that the Labor Act—the main legislative instrument regarding employment—does not cover the informal sector and other areas with high degrees of child labor, must be considered a major shortcoming since working children do not benefit from any of its protective measures (Ozgun and Gungordu, 2021). This also means that the Labor Inspectorate Agency, which is responsible for the implementation of the Labor Act, only rarely examines those sectors which employ children (Bakirci, 2002), making it easier for child labor to remain undetected. A further inconsistency has been observed regarding the combination of work and education: Since compulsory education has been extended to 12 years, children usually complete mandatory education when they are 18 years old. At the same time, light work which is allowed from the age of 14 onwards, is only permitted if a child has terminated primary education (Ozgun and Gungordu, 2021). Furthermore, the lacking implementation and enforcement of the law has been criticized to prevent effective protection against child labor (Bakirci, 2002, p. 61). Therefore, prohibited child labor will remain a problem as long as there are no structured mechanisms for the proper implementation of the law (Yalçin, 2016, p. 97). Yalçin (2016, p. 97) highlights the inspections conducted by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, criticizing them to be a failed attempt to implement the Labor Act. The penalties available for sanctioning prohibited child labor have been further disapproved for being too lenient (Bakirci, 2002, p. 61), and scholars call for more serious instruments to sanction prohibited child labor, along with improved monitoring of their implementation (Erdogan and Uyan Semerci, 2018, p. 139). On this note, Ozgun and Gungordu (2021) criticize that employers are not immediately fined when a breach of labor legislation has been detected, but that they enjoy a correction period. The authors argue that this “flexible approach creates a regulatory gap and encourages breaches of child labor regulations.” Although a firm legal response is important in combating child labor, a more comprehensive approach that also addresses root causes of child labor, supports families in making ends meet, and invests in the prevention of prohibited child labor is required.

Syrian Child Labor and the 2019 National Survey

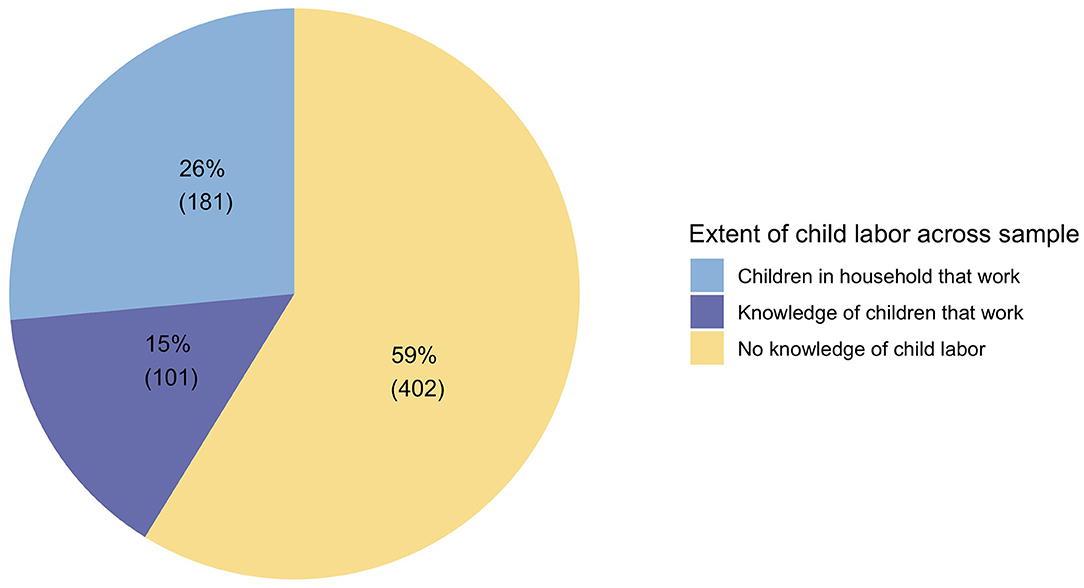

According to the child labor survey conducted by the Turkish Statistical Institute in 2019, there were 720'000 children aged 5–17 who were engaged in economic activities in Turkey (TurkStat, 2020). With an estimated total of 16 million 457 thousand children, this accounts for an employment rate of more than 4 percent (TurkStat, 2020). However, this number has been criticized for severely underestimating the issue for several reasons, but mostly because Syrian children working in Turkey were excluded from the survey (Özbek, 2020; Ozgun and Gungordu, 2021). As already mentioned above, more than 1.8 million Syrian children have come to the country since 2011, of which many are believed to be working. Our survey confirmed a high number of working Syrian children: 41 percent of the Syrian respondents have indicated knowledge of child labor in Turkey, either within their own household (26 percent) or outside their household (15 percent), as Figure 1 shows.

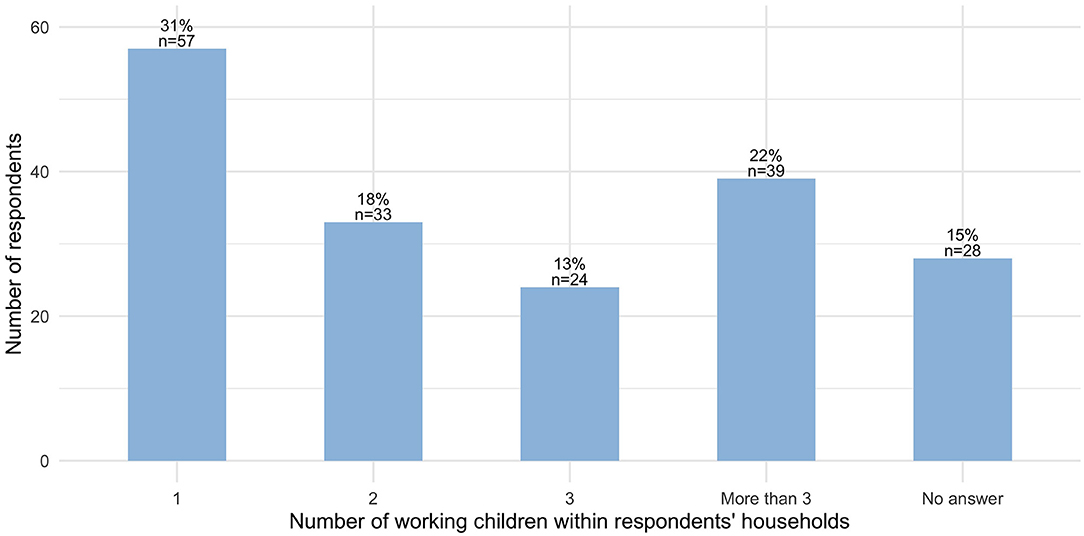

Hereby, the respondents with working children in their households were further asked how many children work within their household. The results in Figure 2 show that 31 percent of the households have only one working child, whereas 53 percent have several children that work. In every fifth household, there are more than three working children. If one adds these cases up, this amounts to at least 351 working children within the respondents' households8. Taken together with the 101 children that are known to be working outside of the respondents' households, this gives a total of 452 working children. However, in our questionnaire, the participants were asked about one specific working child, namely the youngest child known to be working either within or outside the household. Therefore, the further analyses will focus on the 181 (youngest) working children within the respondents' households and the 101 working children referred to by respondents who know of child labor outside of their households. The total of the 282 respective children will be referred to as “all working children” or “all cases of child labor” in the sample. When indicated, a specific focus is put on the 181 working children within the respondents' households.

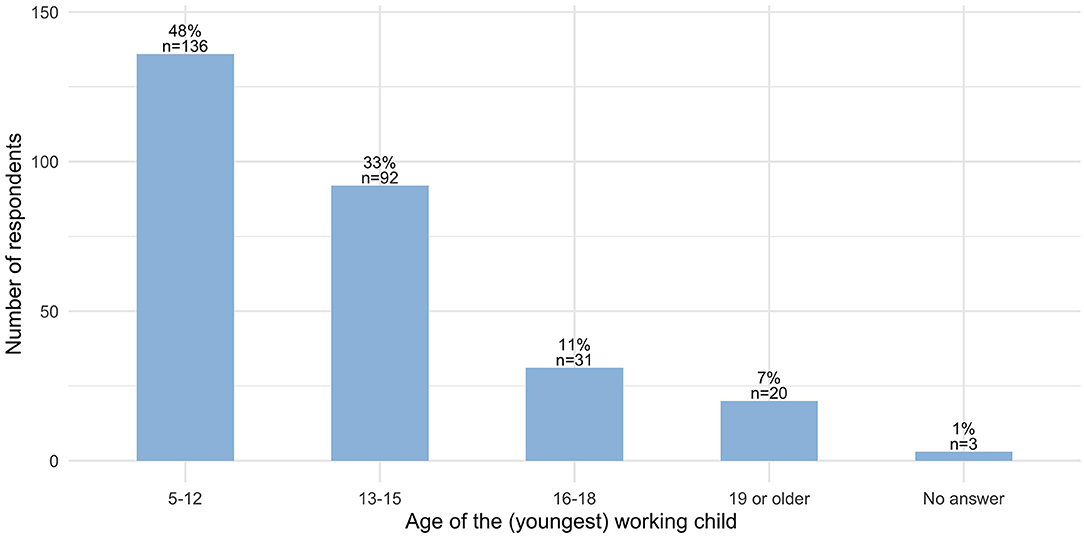

In the following, the results of our survey conducted among Syrian refugees in Turkey are compared to the 2019 national survey on child labor to determine the extent to which children of Syrian refugees are more vulnerable to child labor. Hereby, the differences and commonalities in the characteristics and conditions of child labor among Syrian and Turkish children are discussed. Among the working children included in the 2019 national survey, the vast majority were aged 15–17, whereas only 4.4 percent were reported to be 5–12 years old (TurkStat, 2020). This finding stands in stark contrast to our survey, where it becomes apparent how prevalent child labor is among young Syrian children, see Figure 3. Almost half (48 percent) of the working children included in this sample are between 5 and 12 years old, and children aged 13–15 also make up a considerable share (33 percent) of the Syrian child labor force. It needs to be considered, however, that the survey asks the age of the youngest child known to be working and, consequently, this age distribution is expected to overrepresent the youngest age group.

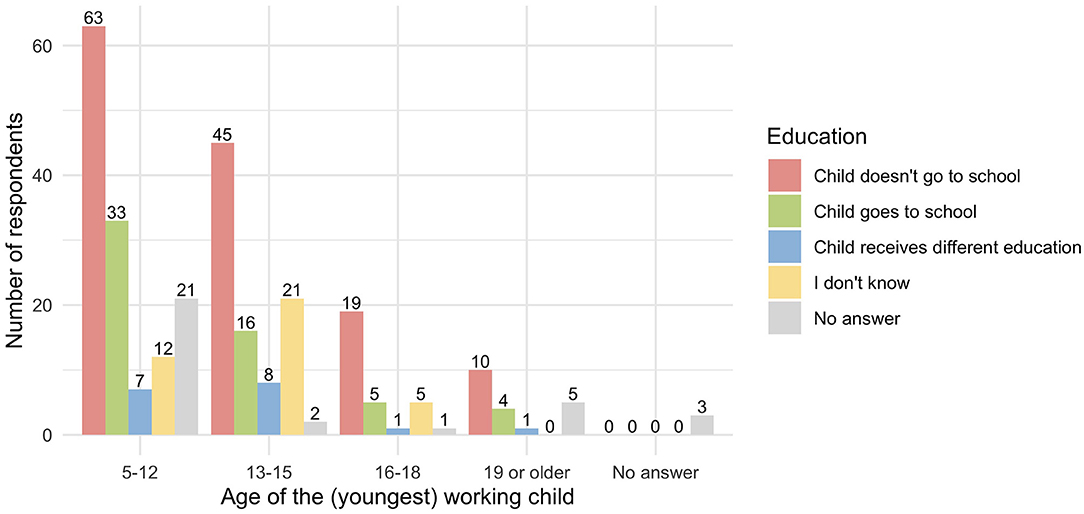

Furthermore, our survey revealed that the education rate among Syrian working children is drastically lower compared to the Turkish children included in the 2019 child labor survey. Whereas, only 21 percent of the respondents in our survey stated that the Syrian working children go to school, the 2019 national survey reported that 66 percent of the working children continue their education (TurkStat, 2020). Hereby, the education rate among Syrian working children is low across all age groups, as Figure 4 demonstrates. Whereas, the schooling rate among the 5–14 years old Turkish minor workers is 72 percent, only 24 percent of the working Syrian children aged 5–12 go to school. And while 64 percent of the 15–17 years old Turkish working children go to school, this rate is only 17 percent among the 13–15 years old Syrian minor workers and 16 percent among those aged 16–18. This finding is not particularly surprising, as previous studies have demonstrated that Syrian children are confronted with severe challenges in obtaining education in Turkey (Uyan-Semerci and Erdogan, 2018).

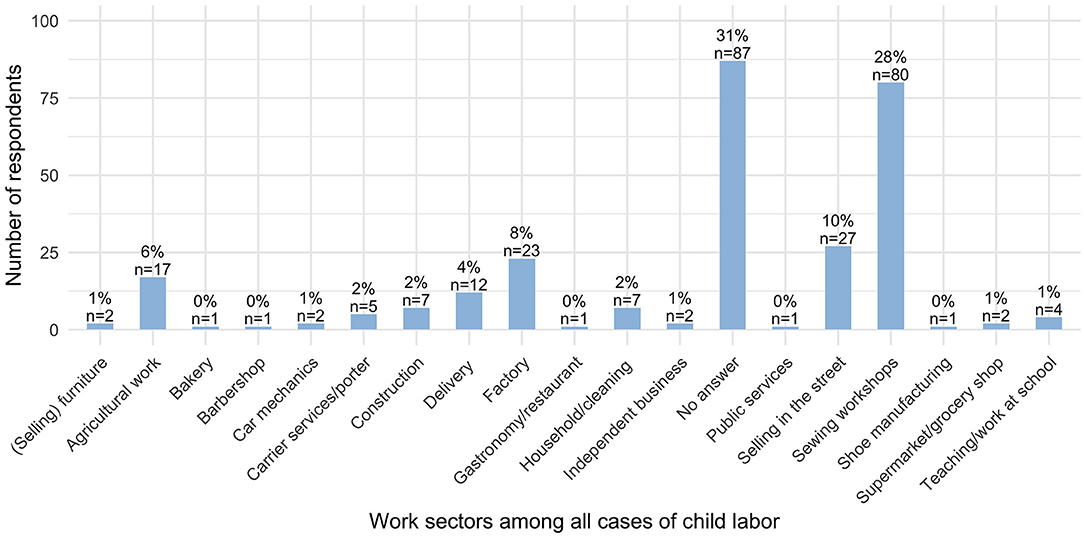

Regarding the work sectors the children are most involved in, our sample revealed that child labor among Syrian refugees is most common in sewing workshops (28 percent), followed by selling in the street (10 percent), factories (8 percent), and agriculture (6 percent), as shown in Figure 59. In comparison, the sectoral distribution among Turkish children shows a greater share of children in the service sector (46 percent) and agriculture (31 percent), along with a share of 24 percent in industry (TurkStat, 2020). At first sight, these results suggest that Syrian children work much less in agriculture than Turkish children, but instead find work more often in sewing workshops. On one hand, this stands in line with existing research demonstrating the prevalence of Syrian children working in the textile industry (Yalçin, 2016, p. 91). On the other hand, it needs to be considered that the work sector's predominance may vary by region, whereby agriculture is expected to be more prevalent in rural areas, and industry or service jobs seem more common in urban areas. And as the survey on child labor among Syrian refugees did not cover all regions of Turkey, and certain places of residence such as Istanbul, Gaziantep, or Hatay were more represented among the respondents, the results need to be interpreted accordingly. Indeed, the numbers show that sewing workshops are by far the most common work sector in Istanbul and Gaziantep—two regions which together account for more than a third of the respondents. Therefore, the regional distribution of the survey participants needs to be taken into account when discussing the high share of Syrian children in sewing workshops and the low proportion in agriculture, especially considering recent studies that show the high number of Syrian refugees working as seasonal workers in Turkish agriculture (Kavak, 2016).

When it comes to the reasons for child labor, the 2019 national survey and the survey among Syrian refugees show similar results. Both Turkish and Syrian children seem to work primarily out of financial needs to contribute to the household income. More specifically, the 2019 national survey revealed that 59 percent of the Turkish children work to help the household's economic activity and income, and 6 percent work to support their needs (TurkStat, 2020). In the survey among Syrian refugees, the respondents with working children within their households were asked what consequence they see if the respective child stopped working. Similarly, the results show that financial distress is by far the most frequent concern. More specifically, the respondents mentioned the inability to cover daily expenses, in particular food, clothes, water, or electricity. This goes so far that many of them mentioned hunger or starvation as a consequence if the child stopped working. Also, the inability to pay rent and the risk of homelessness represent further common concerns. Several respondents stated that the loss of income would make it impossible to live or to live in dignity. From this, it can be concluded that it is often out of basic needs that children of Syrian refugees go to work, and that child labor is needed as a financial contribution to the household income. This finding also stands in line with previous studies (Lordoglu and Aslan, 2019, p. 59). Apart from financial motives, another 34 percent of Turkish children were reported to work to learn a profession and to gain skills for a job (TurkStat, 2020). This seems to differ from children of Syrian nationality, for whom learning a profession or gaining relevant skills was only mentioned as a benefit of child labor in very few cases. Also, only 9 percent of the respondents stated that the work performed by the respective child is part of vocational training.

Further Characteristics of Child Labor Among Syrian Refugees

Apart from the statistics discussed above, the Turkish national survey and the questionnaire conducted in the scope of our research covered different topics related to child labor. Whereas the first asked additional questions regarding children's employment status, working conditions, and household chores, we collected further data on the working hours, wages, duration, and impact of child labor, along with the influence of the residence status and the household size on the prevalence of child labor. In the following, these aspects regarding child labor among Syrian refugees in Turkey are analyzed more in-depth, yet without a comparison to the Turkish minor workforce.

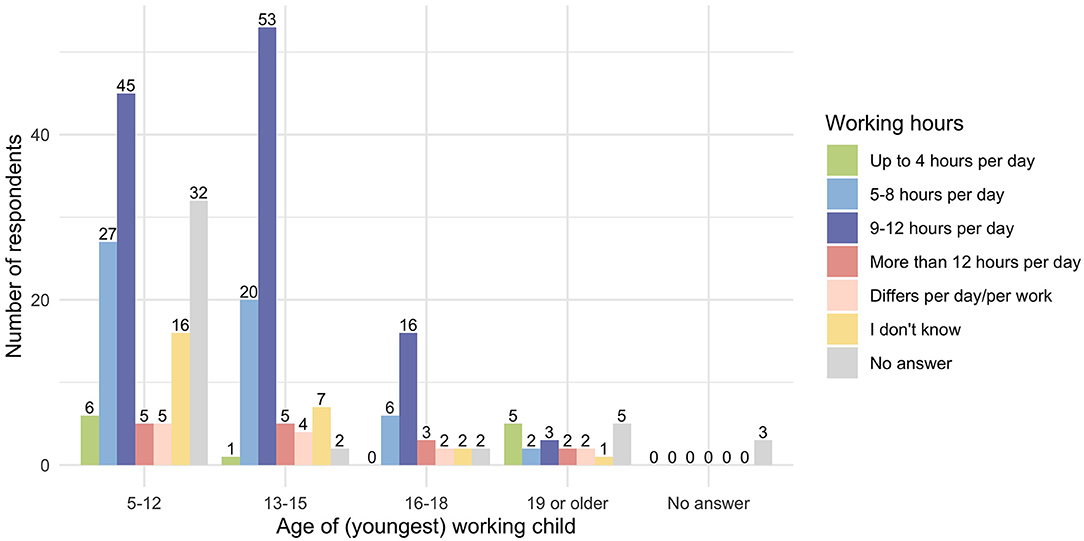

Regarding the working hours of the Syrian children, the analysis revealed that the biggest share of the children included in the sample (41 percent) work 9–12 h per day. Also, 5 percent work more than 12 h daily. This means that around half of the Syrian child laborers in our survey work more than the legal limit of 7 h per day10. In contrast, only every fifth Syrian child works 5–8 h, and every twentieth works <4 h a day. These high working hours can be observed among all age groups. “9–12 h per day” constitute the most common working hours in every age segment, including those as young as 5–12 years old, as Figure 6 shows.

Furthermore, high working hours are predominant in all common work sectors. “9–12 h per day” was indicated most often for children working in sewing workshops, factories, or in agricultural work. Only for children that are selling in the street, daily working hours of 5–8 h were mentioned a few times more often than those of 9–12 h.

Concerning the children's wages, the survey disclosed that 80 percent of the working children within the respondents' households are paid <100 Turkish liras (TL) (which corresponds to 11.14 Euro) per day. Only 5 percent of the working children receive daily wages that are higher than 100TL. This shows that the great majority does not earn the official minimum wage of 108TL per day11.

Furthermore, our survey revealed that around 40 percent of the working children within the respondents' households had been working for <1 year at the time of data collection. 16 percent of the respective children had been working between 1 and 2 years, and 14 percent had been working for more than 3 years. This shows that many of the concerned children had only recently joined the workforce. However, a third of the respondents did not provide an answer regarding the duration of child labor, especially when children from the youngest age group (5–12 years) were concerned.

What is more, the survey demonstrated that most respondents (42 percent) observed a negative impact of child labor (at a non-response rate of 54 percent). The most common reason for this is that children are deprived of education, but also the loss of childhood and negative health effects were mentioned several times. Yet despite the negative impact, the respondents mentioned that they depend on child labor mostly because of financial needs. In contrast, only 2 percent stated that child labor has a positive impact, such as the possibility to learn a profession and to afford education, the chance to increase the child's independence and self-reliance, and distraction from negative influences. Another 2 percent indicated that there are both positive and negative effects.

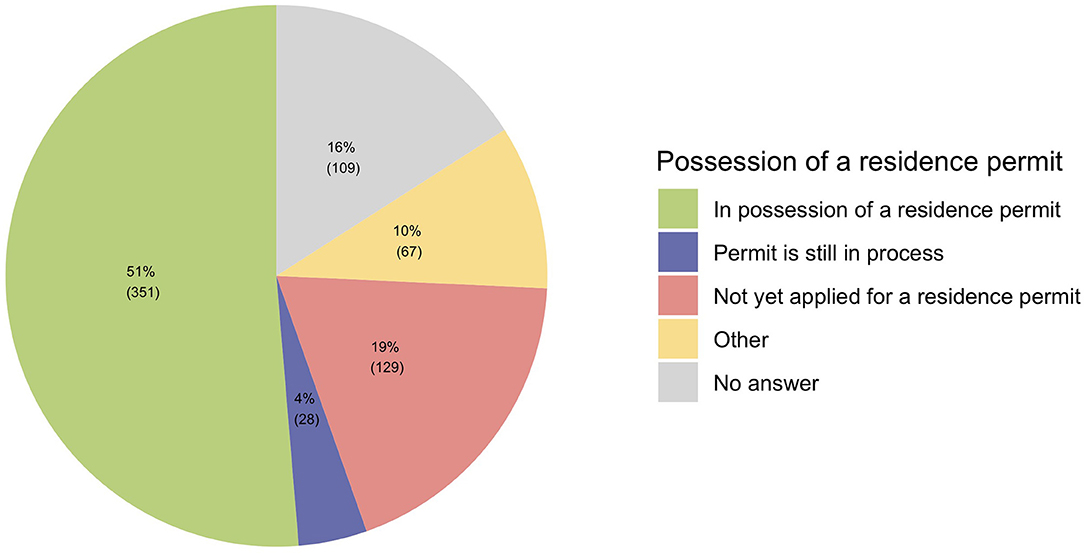

In addition, we examined the role of the residence status with regard to the prevalence of child labor. As already mentioned above, Syrian refugees in Turkey have the option to apply for the official status of “temporary protection.” In our sample, around half of the respondents indicated to have such a status12, whereas 23 percent stated that the process of obtaining an official status is still ongoing, or that they have not yet applied for it. The remaining 26 percent did not provide an answer to this question or indicated “Other,” as illustrated in Figure 7.

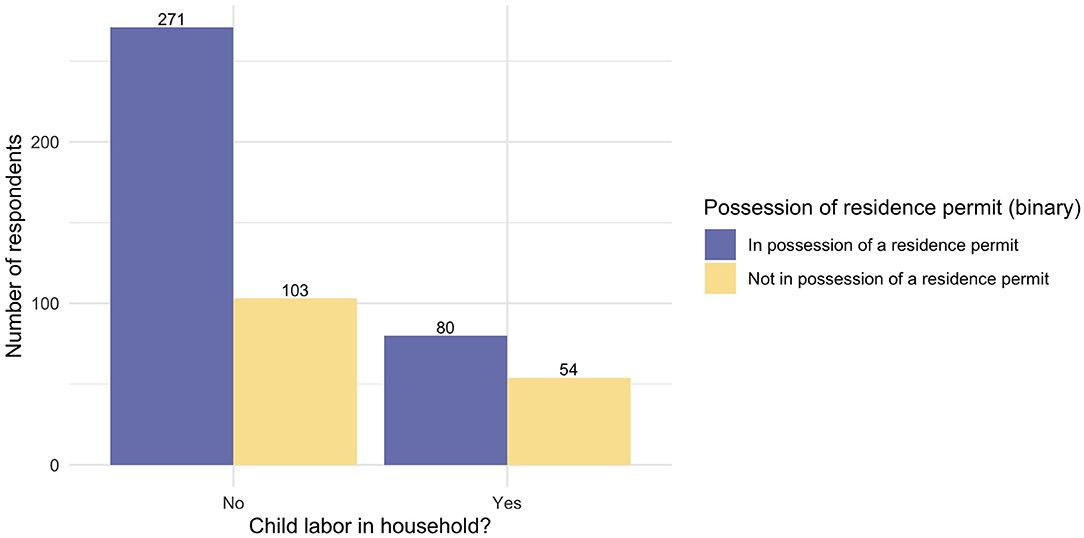

Against this background, we investigated whether there is a correlation between the possession of a residence permit and the existence of child labor in the household. For this, we only looked at those respondents who are either in possession of a residence permit or not, meaning that those who responded “Other” or did not provide an answer were excluded from this particular analysis. The answers “Permit is still in process” and “Not yet applied for a residence permit” were taken together to “Not in possession of a residence permit,” and this new binary variable was then compared between those respondents who do have child labor in their household and those who do not. As Figure 8 shows, the share of “Not in possession of a residence permit” is proportionally larger among those who do have child labor in their household compared to the respondents who do not. Our statistical analysis using a Pearson's Chi-squared test confirmed with a p-value of 0.006101 that the lack of an official residence status indeed correlates with child labor in the household of the respondent.

Figure 8. Possession of a residence permit among respondents with and without child labor in household.

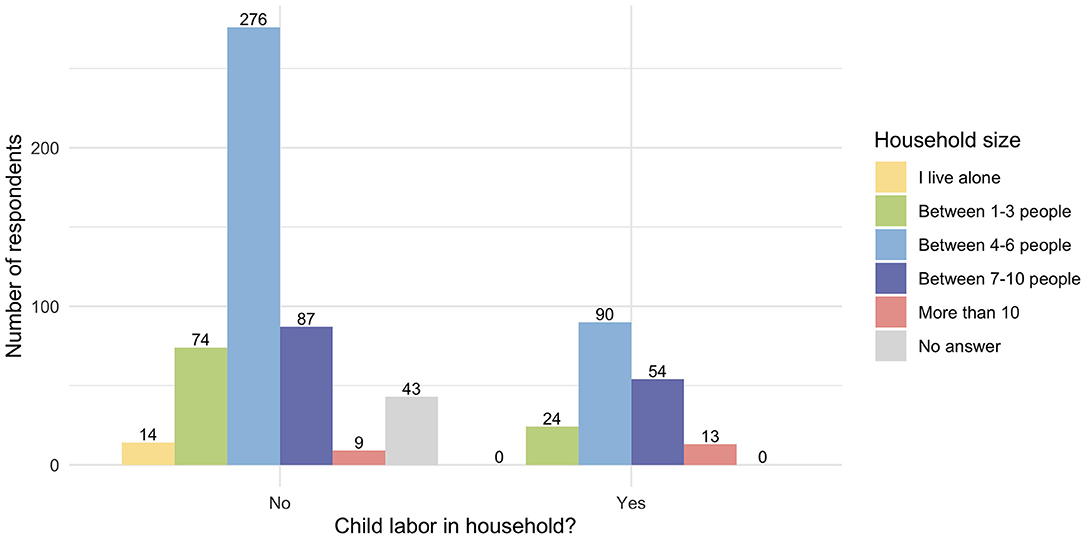

Finally, we examined the influence of the household size on the prevalence of child labor in the household. When comparing the household size between those respondents who do have child labor and those who do not, one can observe that the relative share of medium-sized households (4–6 people) is much higher where there is no child labor in the household, whereas the relative share of big households (more than 10 people) is much higher where there is child labor in the household, as Figure 9 shows. Using a Pearson's Chi-squared test, we found with a p-value of 0.0001643 that there is a statistically significant correlation between the household size and the existence of child labor in the household13.

Discussion

Similar to Syrian children, many Turkish children are driven into the labor force. Nevertheless, it needs to be recognized that Syrian refugees are confronted with additional burdens and insecurities compared to Turkish nationals, for example regarding accessing education and working in the informal sector (Kaya, 2020). The current possibilities to obtain work permits or citizenship comes with many hurdles and most Syrians continue to work in the informal labor market, often for low wages and in jobs considered undesirable by the local population, for instance in the sewing industry. Considering that more than half of the Syrian refugees in Turkey are under the age of 18, many children are driven into the labor force. Our analysis illustrated that these children find themselves in an environment with one of the highest informal economies and child poverty rates among the OECD countries. It is generally understood that child labor is inextricably linked to poverty and low economic development (Thévenon and Edmonds, 2019), but as recognized by Thévenon and Edmonds (2019), other factors beyond the level of economic development are also relevant. In this study, we have defined child labor as labor performed by persons under the age of 18. The ILO's Minimum Age Convention, which allows child labor from the age of 15 or even 14 if it is light work, sets a minimum age for children to perform work. The underlying question here is whether child labor that is permitted by the ILO needs to be eradicated, or if the focus must be on the eradication of exploitative and harmful practices. According to the sustainable development goal target 8.7, all forms of child labor must be eradicated by 2025. In contrast, the ILO takes a two-step approach to child labor, aiming at the abolishment of all forms of child labor while starting with the worst forms of child labor (Van Daalen and Hanson, 2019). With 10 percent of all children engaged in child labor worldwide and half of them working in hazardous and health and safety precarious work—whereby 48 percent of these working children are between 5 and 11 years old (Thévenon and Edmonds, 2019, p. 8)—complete eradication is far away and maybe illusive. At the same time, these figures and our research show that international conventions and national legal frameworks based thereon have a limited impact on the eradication of child labor, and therefore a more comprehensive approach is needed (Thévenon and Edmonds, 2019; Van Daalen and Hanson, 2019). Our research has shown that child labor among Syrian refugees is often needed to make ends meet and until alternative survival strategies and financial means are available, it is unlikely the situation will change (Thévenon and Edmonds, 2019, p. 47–71). The high prevalence of young children at work, including in difficult and hazardous conditions, and the low wages received by them justifies the prioritization to combat these practices, as they are most harmful to children. We refer to these practices as child labor exploitation, defined as work performed by children below the age of 15 years, work that is dangerous and harmful to children, and work that interferes with their schooling e.g., work during school and night hours, thereby connecting these practices with the ILO Minimum Age Convention and the ILO Convention on Worst Forms of Child Labor. Others make a similar distinction but qualify non-harmful work by children as “children in employment” and other forms as “child labor” (Thévenon and Edmonds, 2019, p. 17). Confusingly, child labor then only refers to “work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development” (ILO definition)14. We think that distinguishing between child labor exploitation and child labor better reflects the different realities and the differences between permitted and prohibited child labor, while at the same time recognizing the advantages of child labor if performed in line with international conventions (Anker, 2000). What follows from our data is that both child labor exploitation and child labor are highly prevalent among Syrian refugees in Turkey. Although progress has been made in admitting children to schools and providing work permits, the problem remains pregnant. The burdens to make use of these services are manifold and it has been reported that applying for a work permit would deteriorate one's financial situation because one then cannot apply for financial schemes anymore, thus keeping these persons contained in the informal labor market and precarious work situations (Kaya, 2020). This too has negative repercussions on child labor because working in the informal labor market is more insecure, wages are lower, and risks for not being paid or for underpayment are omnipresent, increasing the need for additional financial means including through child labor (Kaya, 2020).

Conclusion

As a neighboring state of war-torn Syria, Turkey served as a transit and destination country for many people seeking safety and international protection in Europe. At the same time, and especially since the EU-Turkey statement, Turkey became the new home for around 3.6 million Syrians. This paper discussed the restrictions on residence status and labor rights that the Syrian refugee population faces in the new residence country, along with the resulting vulnerabilities in the informal labor market. The analysis demonstrated that Turkey's geographical limitation to the 1951 Geneva Convention and the subsequent recognition of Syrians as “temporary protection holders” but not as “refugees,” does not guarantee a safe and regular residency, but rather a situation of limbo and unpredictability. Furthermore, it has been shown that in Turkey, child labor is not only a cause of concern among the Syrian refugee population but an established practice in the broader context of the labor market and social inequality. In light of the structural nature of child labor in Turkey, this article examined the Turkish legal framework in place to combat child labor, along with its limitations. Hereby, it has been found that through the ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the ILO Conventions 138 and 182, Turkey is committed under international law to combat child labor and to guarantee the enshrined rights. On the constitutional level, there are further obligations to combat child labor. However, they have been found to translate only fragmentarily and inconsistently into national laws and regulations. Although there are provisions on compulsory education, the minimum age for work, working conditions, and working hours, there seem to be several legislative gray areas and shortcomings. Most prominently, the Labor Act, which constitutes the main legislative instrument regarding employment, does not cover the informal sector and other areas with high degrees of child labor, rendering many minor workers without legal protection. Additionally, the insufficient implementation of the existing laws and law enforcement, in general, has been repeatedly criticized to contribute to the widespread prevalence of child labor. This research provided empirical insight into the situation of child labor among Syrian refugees in Turkey and exposed their particular vulnerability to labor exploitation. In comparison to the Turkish minor workers mapped in the 2019 national child labor survey, Syrian children appear to be involved in child labor at a much younger age and have less access to education. Moreover, Syrian children have been reported to work very long working hours, most of them between 9 and 12 h daily, and earn wages lower than 100 Turkish lira per day. These results demonstrate the detrimental human costs of Turkey's approach to dealing with the Syrian refugees living in its territory, where thousands of children are exploited in the labor market, deprived of education, and where many lose their childhoods. Also, the survey results illustrate the precariousness in which many Syrian families find themselves in Turkey, where child labor presents the last resort to make ends meet and to escape severe poverty, hunger, or homelessness. Given the normality of child labor in Turkey and in line with ILO's approach, priority should be given to eradicate child labor exploitation or prohibited child labor and worst forms of child labor, equally addressing Syrian and Turkish children while taking into account the specific vulnerabilities of Syrian children as highlighted in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Review Board, Tilburg Law School, Tilburg University, vice-chair Jan Jans, ZXJiLXRsc0B0aWxidXJndW5pdmVyc2l0eS5lZHU=. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The project was designed by CR. The data analysis was primarily done by IF. The first draft was written by IF. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project was funded by the Tilburg University Fund.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Tilburg University Fund for the funding of this project and Upinion for the fruitful collaboration in collecting the data. Thanks go to Ozan Turhan for reviewing the legal part of this article.

Footnotes

1. ^For the sake of comparability, child labor in this article refers to children below 18 years who perform work. Similarly, the Turkish survey also considers child labor to be economic activities performed by persons under 18 years (TurkStat, 2020). However, not all work done by children below the age of 18 is to be eliminated. Similar to the approach adopted by the ILO, we consider work performed by children below the age of 15 years, work that is dangerous and harmful to children, and work that interferes with their schooling e.g., work during school and night hours, to be undesirable for children. In this article and in accordance with the Convention on the Rights of the Child, these forms of child labor are considered a form of labor exploitation or economic exploitation. Extreme forms of such labor or economic exploitation are referred to as the ‘worst forms of child labor' as defined in ILO Convention 182, which include, among other practices, slavery or practices similar to slavery, child trafficking, debt bondage, forced labor, and prostitution.

2. ^Upinion is an organization dedicated to amplifying people's voices in crisis situations. By gathering instant insights and stories from affected populations, Upinion promotes inclusiveness and effectiveness of humanitarian support, see: www.upinion.com (accessed January 23, 2022).

3. ^Initially, Turkey signed the Convention both with a geographic and a time limitation, but the latter was lifted when signing the 1967 Protocol (Kirişçi, 1996, p. 293).

4. ^In this article, Syrian citizens residing in Turkey in search of safety and international protection are nonetheless referred to as “refugees,” even though they do not carry this official status in Turkey.

5. ^In return, the EU committed to increase its financial contribution toward improving the humanitarian situation of Syrian refugees in Turkey, to accelerate the lifting of visa requirements for Turkish citizens traveling to the Schengen area, and to re-energize Turkey's EU membership negotiation process (Baban et al., 2017; Haferlach and Kurban, 2017; Simşek, 2017).

6. ^Although there are no exact numbers on the enrolment of Syrian children in Turkey, UNICEF estimates that more than 500,000 out of the 850,000 school-aged Syrian children in Turkey have no access to education (Yalçin, 2016, p. 93).

7. ^See: https://ikamet.com/blog/turkey-raises-minimum-wages-for-2020 (accessed January 21, 2022).

8. ^Whereby “More than 3” was counted as 4 children per household that work.

9. ^However, as 31 percent of the respondents did not provide an answer on the work sector of the working child, these numbers should be interpreted with caution and should not be mistaken to depict a full picture.

10. ^Or 8 h for children over 15, respectively. As explained above, this limitation of legal working hours is based on the Labor Act, and accordingly, does not legally protect the children working in the informal labor market or in the other sectors mentioned above.

11. ^Calculation based on monthly net minimum wage of 2'324.70TL and 21.4 average working days per month (average working days according to workday calculator, reference year 2020; https://turkey.workingdays.org/workingdays_holidays_2021.htm).

12. ^Whereby, the survey asked for “possession of a residence permit”.

13. ^For this test, we excluded those respondents who either live alone (as they cannot have child labor in the household) and those who did not indicate their household size.

14. ^See: https://www.ilo.org/ipec/facts/lang–en/index.htm (accessed January 23, 2022).

References

Ahmet, I., and Simşek, D. (2016). Syrian refugees in Turkey: towards integration policies in turkish policy. Quarterly 15, 59–69.

AIDA (2021a). Residence Permit Turkey. Available oline at: https://asylumineurope.org/reports/country/ turkey/content-international-protection/status-and-residence/residence-permit/ (accessed December 17, 2021).

AIDA (2021b). Naturalisation Turkey. Available oline at: https://asylumineurope.org/reports/country/turkey/content-temporary-protection/status-and-residence/naturalisation/ (accessed December 17, 2021).

AIDA (2021c). Access to the Labor Market Turkey. Available oline at: https://asylumineurope.org/reports/country/turkey/content-temporary-protection/employment-and-education/access-labour-market/#_ftn1 (accessed December 17, 2021).

Akin, L. (2009). Working conditions of the child worker in Turkish labour law. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 21, 53–67. doi: 10.1007/s10672-008-9098-7

Anker, R. (2000). The economics of child labour: a framework for measurement. Int. Labour Rev. 139, 257–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1564-913X.2000.tb00204.x

Baban, F., Ilcan, S., and Rygiel, K. (2017). Syrian refugees in Turkey: pathways to precarity, differential inclusion, and negotiated citizenship rights. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 43, 41–57. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1192996

Bakirci, K. (2002). Child labour and legislation in Turkey. Int. J. Children's Rights 10, 55–72. doi: 10.1163/157181802772758128

Bilir, N. (2016). Occupational Safety and Health Profile Turkey. Ankara: International Labour Organization.

Demirguc-Kunt, A., Lokshin, M., and Ravallion, M. (2019). A New Policy to Better Integrate Refugees Into Host-Country Labor Markets. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/turkey/new-policy-better-integrate-refugees-host-country-labor-markets (accessed December 17, 2021).

Erdogan, E., and Uyan Semerci, P. (2018). Illegality in the informal labour market: findings from pilot research on child labour. Istanbul Res. Policy Turkey 3, 138–154. doi: 10.1080/23760818.2018.1517448

Haferlach, L., and Kurban, D. (2017). Lessons learnt from the EU-Turkey refugee agreement in guiding EU migration partnerships with origin and transit countries. Glob. Policy 8, 85–93. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12432

Kanun, O., and Kayaoglu, A. (2019). Child labor and its sectoral distribution in Turkey TT - Türkiye'de çocuk işçiliginin sebepleri ve sektörel dagilimi. Calisma ve Toplum 62, 1991–2014.

Kavak, S. (2016). Syrian refugees in seasonal agricultural work: a case of adverse incorporation in Turkey. N. Perspect. Turkey 54, 33–53. doi: 10.1017/npt.2016.7

Kaya, A. (2020). Reception: Country Report. Global Migration: Consequences and Responses Working Paper. Istanbul 37.

Kirişçi, K. (1996). Is Turkey lifting the 'geographical limitation'? - The November 1994 regulation on asylum in Turkey. Int. J. Refugee Law 8, 6–11. doi: 10.1093/ijrl/8.3.293

Koca, B. T. (2016). Syrian refugees in Turkey: from “guests” to “enemies”? N. Perspect. Turkey 54, 55–75. doi: 10.1017/npt.2016.4

Lordoglu, K., and Aslan, M. (2019). “The invisible working force of minor immigrants: the case of syrian children in Turkey,” in Integration through Exploitation: Syrians in Turkey, ed G. Yilmaz, I. D. Karatepe, and T. Tören (München: Rainer Hampp Verlag), 55–66.

OECD (2021). OECD Family Data Base: Child Poverty. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/CO_2_2_Child_Poverty.pdf (accessed December 17, 2021).

Özbek, A. (2020). TurkStat's Child Labor Survey is Not Realistic as it Does Not Cover Syrian Children. Available online at: https://bianet.org/english/children/222335-turkstat-s-child-laborsurvey-is-not-realistic-as-it-does-not-cover-syrian-children (accessed December 17, 2021).

Özden, S. (2013). Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. doi: 10.9779/pauefd.490559

Ozgun, A., and Gungordu, A. (2021). Child Labor in Turkey and the Need for Human Rights Due Diligence For Corporations. Available online at: https://www.cetinkaya.com/insights/child-labor-turkey-need-human-rights-due-diligence-corporations (accessed December 17, 2021).

Simşek, D. (2017). Turkey as a “Safe Third Country”? The impacts of the EU-Turkey statement on Syrian refugees. Turkey Percept. J. Int. Affairs 22, 161–182.

Simşek, D. (2020). Integration processes of Syrian refugees in Turkey: ‘Class-based integration'. J. Refugee Stud. 33, 537–554. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fey057

Thévenon, O., and Edmonds, E. (2019). Child Labour: Causes, Consequences and Policies to Tackle it. Paris: OECD Publishing.

TurkStat (2020). Child Labor Force Survey 2019. Available online at: https://turkstatweb.tuik.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=33807 (accessed February 2, 2021).

UNHCR (2021). Syria Refugee Crisis Explained. Available online at: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/syria-refugee-crisis-explained/ (accessed December 17, 2021).

Uyan-Semerci, P., and Erdogan, E. (2018). Who cannot access education? Difficulties of being a student for children from Syria in Turkey. Vulnerable Children Youth Stud. 13, 30–45. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2017.1372654

Van Daalen, E., and Hanson, K. (2019). “The ILO's shifts in child labour policy: regulation and abolition,” in The ILO @ 100, eds U. Panizza, C. Gironde, and G. Carbonnier (Leiden; Boston, MA: Brill Nijhoff), 133–151. doi: 10.1163/9789004399013_008

Keywords: child labor, Syrian refugees, child labor exploitation, causes of child labor, Turkey

Citation: Fehr I and Rijken C (2022) Child Labor Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Front. Hum. Dyn. 4:861524. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2022.861524

Received: 24 January 2022; Accepted: 28 February 2022;

Published: 26 April 2022.

Edited by:

Jane Freedman, Université Paris 8, FranceReviewed by:

Lucy Williams, University of Kent, United KingdomSibel Safi, Dokuz Eylul University, Turkey

Copyright © 2022 Fehr and Rijken. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Conny Rijken, Yy5yLmouai5yaWprZW5AdGlsYnVyZ3VuaXZlcnNpdHkuZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Irina Fehr

Irina Fehr Conny Rijken*†

Conny Rijken*†