94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 10 June 2022

Sec. Migration and Society

Volume 4 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2022.778592

This article is part of the Research Topic Women's Empowerment, Migration and Health View all 9 articles

Brian D. Earp1,2,3*

Brian D. Earp1,2,3*The World Health Organization (WHO) condemns all medically unnecessary female genital cutting (FGC) that is primarily associated with people of color and the Global South, claiming that such FGC violates the human right to bodily integrity regardless of harm-level, degree of medicalization, or consent. However, the WHO does not condemn medically unnecessary FGC that is primarily associated with Western culture, such as elective labiaplasty or genital piercing, even when performed by non-medical practitioners (e.g., body artists) or on adolescent girls. Nor does it campaign against any form of medically unnecessary intersex genital cutting (IGC) or male genital cutting (MGC), including forms that are non-consensual or comparably harmful to some types of FGC. These and other apparent inconsistencies risk undermining the perceived authority of the WHO to pronounce on human rights. This paper considers whether the WHO could justify its selective condemnation of non-Western-associated FGC by appealing to the distinctive role of such practices in upholding patriarchal gender systems and furthering sex-based discrimination against women and girls. The paper argues that such a justification would not succeed. To the contrary, dismantling patriarchal power structures and reducing sex-based discrimination in FGC-practicing societies requires principled opposition to medically unnecessary, non-consensual genital cutting of all vulnerable persons, including insufficiently autonomous children, irrespective of their sex traits or socially assigned gender. This conclusion is based, in part, on an assessment of the overlapping and often mutually reinforcing roles of different types of child genital cutting—FGC, MGC, and IGC—in reproducing oppressive gender systems. These systems, in turn, tend to subordinate women and girls as well as non-dominant males and sexual and gender minorities. The selective efforts of the WHO to eliminate only non-Western-associated FGC exposes the organization to credible accusations of racism and cultural imperialism and paradoxically undermines its own stated goals: namely, securing the long-term interests and equal rights of women and girls in FGC-practicing societies.

Female, male, and intersex forms of non-therapeutic child genital cutting—so-called “gendered genital modifications” (Fusaschi, 2022)—tend to be discussed and evaluated separately, both in scholarly and popular discourses. It is increasingly recognized, however, that despite various differences between them, the practices also share certain features that render this tendency toward discursive separation questionable on several grounds. Scientifically, the tendency is questionable because in many countries at least two, and sometimes all three, forms of cutting are carried out together within the same cultural contexts or institutions; in these cases, the practices are often tightly symbolically linked, serving complementary or mutually reinforcing social functions. These functions—for example, maintaining gendered social divisions and associated power hierarchies—cannot adequately be understood, much less appropriately addressed, by studying each practice in isolation (Caldwell et al., 1997; Junos, 1998; Toubia, 1999; Lightfoot-Klein et al., 2000; Abu-Sahlieh, 2001; Knight, 2001; Robertson and James, 2002; Boddy, 2007; Merli, 2008, 2010; Fox and Thomson, 2009; Androus, 2013; Reis, 2013; Svoboda, 2013; Ahmadu, 2016a; Prazak, 2017; Johnsdotter, 2018; Earp, 2020a).

Legally, the tendency is questionable because it may lead to discriminatory treatment of different persons or groups based on constitutionally forbidden criteria, such as sex, gender, race, religion, ethnicity, or national origin (Coleman, 1998; Bond, 1999; Price, 1999; Davis, 2001; Mason, 2001; Somerville, 2004; Dustin, 2010; Johnsdotter and Essén, 2010; Askola, 2011; Adler, 2012; Merkel and Putzke, 2013; Fusaschi, 2015; Arora and Jacobs, 2016; Rogers, 2016, 2022; Svoboda et al., 2016; Earp et al., 2017; La Barbera, 2017; Shahvisi, 2017; Munzer, 2018; Notini and Earp, 2018; Pardy et al., 2019; Möller, 2020; Carpenter, 2021; Ahmadu and Kamau, 2022; Bootwala, 2022; Earp, 2022a; Rosman, 2022; Shweder, 2022b). And ethically, the tendency is questionable because, in practice, it privileges the customs of more powerful stakeholders (Gunning, 1991; Lewis, 1995; Obiora, 1996; Tangwa, 1999, 2004; Toubia, 1999; Androus, 2004, 2013; Chambers, 2004; Njambi, 2004; Bell, 2005; Ehrenreich and Barr, 2005; Shweder, 2005; Oba, 2008; Boddy, 2016, 2020; Ahmadu, 2017; Onsongo, 2017; Coene, 2018; Kart, 2020; MacNamara et al., 2020; Shahvisi, 2021), while also occluding overlapping moral concerns about the different forms of child genital cutting (Davis, 2003; Hellsten, 2004; Svoboda and Darby, 2008; van den Brink and Tigchelaar, 2012; Antinuk, 2013; Shweder, 2013; Svoboda, 2013; Earp, 2015b, 2020b; Shahvisi, 2016; Jones, 2017; Carpenter, 2018a; O'Donnell and Hodes, 2018; Lunde et al., 2020; O'Neill et al., 2020; Sarajlic, 2020; Townsend, 2020, 2022; Reis-Dennis and Reis, 2021). This moral occlusion leads to incoherent, unjust, and often ineffective or harmful social policies, which may further disadvantage the very groups that are meant to be helped (Coleman, 1998; Gruenbaum, 2001; Manderson, 2004; Berer, 2010, 2015; Johnson, 2010; Evans, 2011; Abdulcadir et al., 2012; Aktor, 2016; Latham, 2016; Johnsdotter, 2019; Karlsen et al., 2019, 2020, 2022; Sandland, 2019; Earp and Johnsdotter, 2021; Hehir, 2022; Johnsdotter and Wendel, 2022).

In response to these concerns, scholars of genital cutting have increasingly undertaken a more comprehensive, cross-cultural and cross-sex comparative approach, particularly in the last several years. For example, in a recent publication, a large group of scholars from diverse countries, cultures, and disciplinary backgrounds highlighted the following shared aspects of non-therapeutic female, male, and intersex child genital cutting (FGC, MGC, and IGC, respectively), that seemed to them to be morally—and perhaps also legally—relevant:

they are all (1) medically unnecessary acts of (2) genital cutting that are (3) overwhelmingly performed on young children (4) on behalf of norms, beliefs, or values that may not be the child's own and which the child may not adopt when of age. Indeed, such norms, beliefs, or values are often controversial in the wider society and hence prone to reevaluation upon later reflection or exposure to other points of view (e.g., the belief that a child's body must conform to a strict gender binary; that surgery is an appropriate means of pursuing hygiene; that one's genitals must be symbolically purified before one can be fully accepted; and so on). In this, they constitute painful intrusions into the “private parts” of the most vulnerable members of society, despite being [of] contested value overall (BCBI, 2019) (p. 21).

Nevertheless, despite such similarities, there has been considerable resistance among policymakers, legislators, international health agencies, and other key actors—especially those situated in or led from within the Global North—to evaluate these practices together. This resistance has been strongest in response to proposals to treat FGC and MGC together, so it is this comparison, along with common objections to it, that will serve as the primary focus of this paper.1

Why has there been such resistance to comparing female and male forms of child genital cutting? There are several potential explanations. As I discuss near the end of the paper, a partial explanation stems from sociological factors having to do with which countries or cultures predominately practice each form of genital cutting, and which of these countries or cultures have more “bargaining power”—for example, in determining what counts as a human rights violation—in the relevant spheres of influence (Tangwa, 1999; Njambi, 2004; Shweder, 2005; Oba, 2008; Carpenter, 2014; Latham, 2016; Onsongo, 2017). As Nahid Toubia has argued, at least one important difference between FGC and MGC is that “the female procedure is primarily carried out in Africa, which is currently the least dominant culture in the world. The male procedure is also common in the same countries, but it is also common in the United States, which is currently the most dominant culture in the world through its far-reaching media machine. This historical situation has made it easier to vilify and condemn what is common in Africa and sanctify what is popular in America” (Toubia, 1999) (p. 5).

This would suggest that reasons having to do with geopolitics and power are key to understanding what medical historian Robert Darby has described as “our habit of placing male and female genital cutting in separate ethical boxes” (Darby, 2016) (p. 155). However, there may also be principled reasons for treating the practices differently that could justify such separation. In this vein, there have been two main strategies for rejecting any moral comparison between FGC and MGC of children. The first has been to argue that the practices are highly distinct from one another in terms of typical health outcomes, whether considering physical or psychosexual harms or benefits. For example, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), in contrast to FGC, which “has no known health benefits [but] is known to be harmful to girls and women in many ways,” MGC, in the form of penile circumcision, “has significant health benefits that outweigh the very low risk of complications when performed by adequately-equipped and well-trained providers in hygienic settings” (WHO, 2008) (p. 1 and 11).

The second main strategy has been to argue that, even if the health outcomes were similar in certain respects, there would still be an important moral difference between the practices in terms of their underlying intent, social functions, cultural associations, or symbolic meanings. According to the WHO, again: “Communities that practice female genital mutilation report a variety of social and religious reasons for continuing with it.” However, “as seen from a human rights perspective, the practice reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes, and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women” (WHO, 2008) (p. 1). MGC, by contrast, is generally not thought to constitute sex-based discrimination, whether against women and girls or indeed against men and boys. It is therefore not seen as conflicting with human rights (here, the right not to be discriminated against on account of one's sex or gender).

In the first part of this paper, I respond to the “health outcomes” argument of the WHO, showing that the alleged or purported differences in health benefits vs. harms—even if they are simply granted—cannot justify the current, categorically different treatment of the two types of genital cutting, especially as performed on non-consenting minors. This part of the paper will be comparatively brief, however, as I have previously addressed the health-based argument elsewhere (most recently in Earp, 2021a).

In the second part of the paper, I respond to the argument that, while FGC discriminates against women and girls, reflecting their lower status in society, MGC does not share these objectionable features. Instead, it is often said, MGC actually reflects the higher status of boys and men, practically and symbolically elevating them into positions of power (Dorkenoo, 1994).

I first raise some empirical concerns about the scope or generalizability of these claims, arguing that, while they may apply in some cases or along certain dimensions, they do not apply universally. Instead, it is necessary to take a more culture-relative and context-sensitive approach to understanding these ritual practices (Leonard, 2000a; Wade, 2012). Then, simply granting the claimed difference between MGC and FGC in relation to status or power, I reflect on the moral and political implications of this claim. I argue that, even if it is granted that the primary function of MGC in some communities is to “elevate” boys into powerful men, this would not, from the perspective of disrupting gendered socialization processes that oppress and subordinate women and girls, constitute a reason to ignore the male rite while seeking only to eliminate the female rite. It would, instead, constitute a compelling reason to (also) oppose the male rite.

As I aim to demonstrate, boys in many cultures are only “elevated” in the above-described sense if they successfully prove their masculinity in accordance with overtly patriarchal standards: in other words, the power that they may gain through these rites is typically power over women and girls (Junos, 1998). Insofar as that is a common effect or purpose of MGC, this should make the rite more concerning, not less concerning, from the perspective of seeking to promote women's and girls' flourishing and equal rights.

However, in patriarchal cultures, MGC and associated norms do not only contribute to the ongoing subordination of women and girls. As I argue, they also subordinate males who are perceived to be insufficiently masculine, including gay men and non-circumcised boys. These boys often face severe social mistreatment including ostracization unless they submit to a risky and painful genital cutting procedure (WHO, 2009).2 Moreover, in societies where MGC, but not FGC, is practiced and regarded as legal, boys face distinctive challenges. Although almost every society that practices FGC also practices MGC in tandem—meaning that girls are not singled out for genital cutting—the inverse is not true. Instead, there are many societies that ritually cut the genitals only of boys, precisely on account of their gender (Cohen, 1997, 2022; DeMeo, 1997; Abdulcadir et al., 2012). Insofar as being subjected to a medically unnecessary, non-consensual act of genital cutting is a moral violation in its own right, boys in these societies are discriminated against in the sense that, due to their gender, only they lack legal protection from such cutting (Möller, 2020).

Of course, there need not be a choice between opposing either FGC or MGC. Rather, a focus on children's rights could motivate campaigns against all non-consensual, medically unnecessary genital cutting of minors—female, male, or intersex—aimed at protecting the most vulnerable members of society on a non-discriminatory basis from adult interference with their sexual anatomy (Junos, 1998; Svoboda, 2013; Earp and Steinfeld, 2017; Townsend, 2022). In fact, given the symbolic and functional linkages between FGC and MGC in societies that practice both together—sometimes also alongside IGC; see Box 1—such a conjoined effort may be necessary for the successful abandonment of either (Abu-Sahlieh, 1994; Martí, 2010; Prazak, 2017; Šaffa et al., 2022).

Box 1. The role of intersex genital cutting in upholding patriarchal gender systems

How does intersex genital cutting (IGC) relate to patriarchal gender systems? On classic models, patriarchy requires socialization of persons into dichotomous gender roles, with a clear distinction between (dominant) men and (subordinated) women, and thus between male and female bodies. Because IGC attempts to surgically remove signs of sexual ambiguity, it is, on this view, strongly implicated in patriarchal social formations, laying the “physical” groundwork for an oppressive gender binary (Hird, 2000; Ehrenreich and Barr, 2005; Reis, 2009). This may have policy implications. As this paper suggests, the WHO opposes “FGM,” not only on the grounds that it involves medically unnecessary genital cutting, typically of a pre-autonomous minor, but also because it upholds oppressive gender norms that disadvantage women and girls. If that is correct, then, for the sake of consistency in promoting its own aims, the WHO should also campaign against IGC (i.e., as a means of resisting gender oppression). IGC does not only indirectly contribute to gender-based oppression of women and girls, however. According to advocates for intersex rights, it also directly, indeed violently, oppresses persons with intersex traits, including intersex males, intersex females, and persons whose bodies or identities confound such binary classification altogether (Chase, 1998; Dreger, 1999; Reis, 2009, 2019; Carpenter, 2016, 2018b; Viloria, 2017).

The take-home message of the paper is this: regardless of one's position on the role of FGC in socially subordinating women and girls, MGC rites in the same and other societies (also) uphold patriarchal power structures. Indeed, as I will argue, in many contexts, the genital cutting of boys and associated rituals are in fact central cultural mechanisms by which female-oppressive gender norms are reinforced in each generation. Thus, if a desire to contest such norms is at the heart of global campaigns to eliminate FGC, then, insofar as these campaigns are justified, it may be equally important, if not more important, for them to target MGC as well.

I proceed as follows. I first map out, in more detail, the various moral and conceptual inconsistencies that have been identified within the WHO's policies on genital cutting. I then address possible justifications of these inconsistencies, based on allegedly different health-related outcomes as well as divergent social functions or symbolic meanings. I then describe how MGC in many societies socializes boys to become “real men” (Dembroff, 2022) in accordance with patriarchal ideology. For the purposes of this paper, patriarchy refers to a social system within which males, in particular those who are interpreted as fulfilling locally normative expectations of masculinity—so-called “real men”—disproportionately occupy positions of power and privilege across multiple domains. Moreover, these men maintain their dominant status through structural oppression of females as well as non-dominant males (e.g., males who are subordinately racialized, disabled, or perceived to be of a lower class; young or effeminate boys, and so on) and likewise gender and sexual minorities (e.g., gay or transgender persons): all “not real men” according to this ideology (Dembroff, 2022). I conclude by discussing the work of Egyptian feminist Seham Abd el Salam, who argues that selective condemnation of FGC—while ignoring or promoting MGC—represents a political “bargain” with conservative patriarchal forces, given that, in her view, MGC is a distinctly powerful means of upholding men's dominance in society (Abd el Salam, 1999).

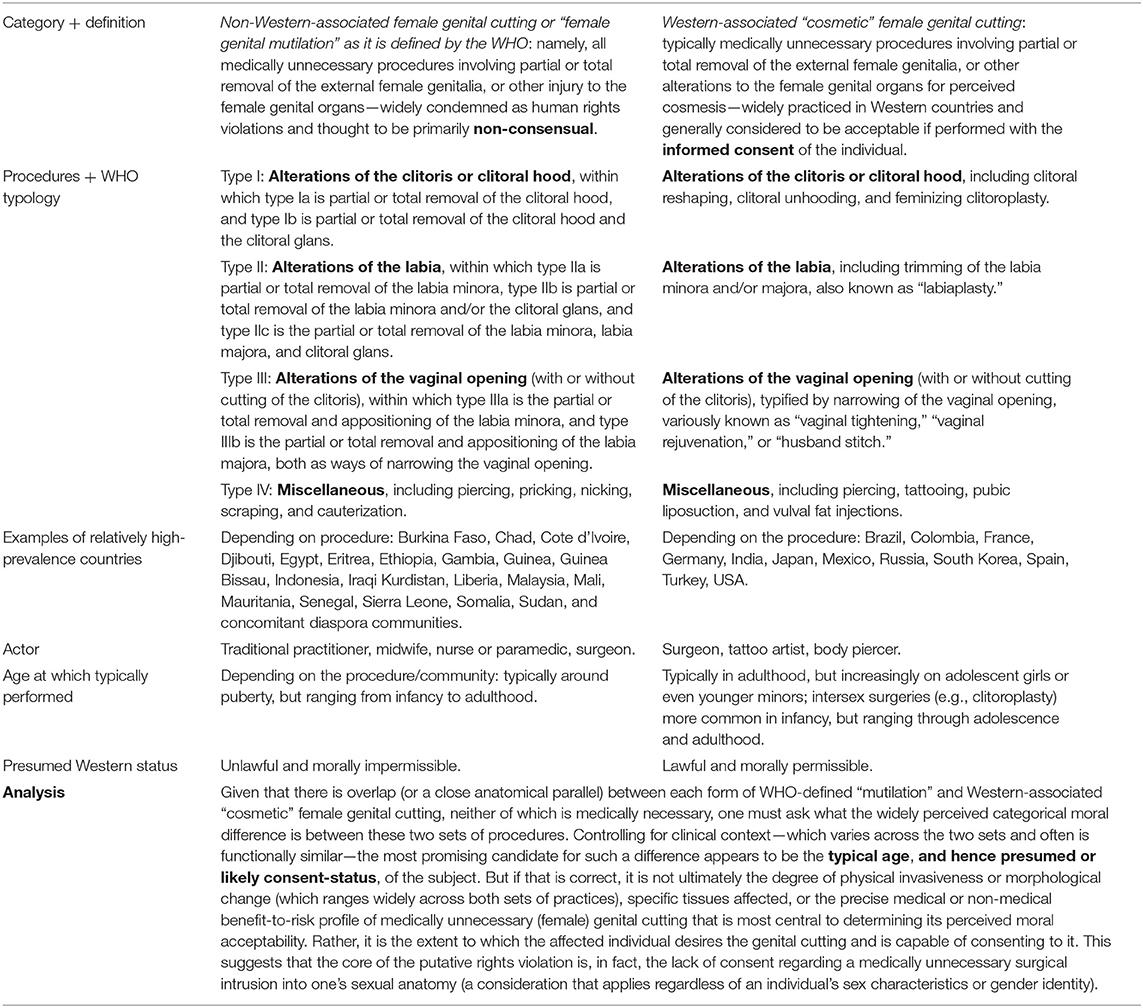

For decades, scholars have called attention to troubling inconsistencies in the WHO's policies on medically unnecessary3 genital cutting practices, especially those imposed on children (Junos, 1998; Toubia, 1999; Lightfoot-Klein et al., 2000; Ehrenreich and Barr, 2005; Oba, 2008; Svoboda and Darby, 2008; DeLaet, 2009; Askola, 2011; van den Brink and Tigchelaar, 2012; Svoboda, 2013; Coene, 2018; Johnsdotter, 2018; Sandland, 2019). The WHO conceptualizes “female genital mutilation” (FGM) as all non-therapeutic cutting, however slight, of the external genitalia of (non-intersex)4 females—irrespective of the individual's consent—and categorically condemns such cutting as a violation of the human right to bodily integrity. However, the WHO has exclusively sought to eliminate medically unnecessary female genital cutting (FGC) practices that are customary in parts of the Global South, while ignoring comparable practices that are common in the Global North, such as elective labiaplasty (see Table 1) which is increasingly performed on adolescent girls (Liao et al., 2012; Runacres and Wood, 2016; Boddy, 2020).

Table 1. Non-Western-associated female genital “mutilation” (Global South) vs. Western-associated “cosmetic” female genital cutting (Global North); adapted from BCBI (2019) and Shahvisi and Earp (2019); internal references ommitted.

Numerous scholars have argued that this selective focus reflects moral double standards rooted in racism and cultural imperialism (Gunning, 1991; Obiora, 1996; Tangwa, 1999; Ahmadu, 2000, 2007, 2016b; Mason, 2001; Shweder, 2002, 2013; Njambi, 2004; Ehrenreich and Barr, 2005; Oba, 2008; Dustin, 2010; Smith, 2011; Kelly and Foster, 2012; Boddy, 2016, 2020; Onsongo, 2017; Shahvisi, 2017, 2021; Shahvisi and Earp, 2019). Some have therefore called on the WHO to revise its policy: either by including Western-associated5 so-called “cosmetic” female genital surgeries in the campaign against “FGM” (Esho, 2022), or by establishing an age limit or consent criterion for FGC to be applied without discrimination or favor (Dustin, 2010; Shahvisi, 2021). According to this latter approach, self-affecting FGC requested by legally competent adult women or sufficiently mature (e.g., Gillick-competent)6 minors would in principle be allowed (assuming certain conditions are met regarding, e.g., safety and informed consent), while medically unnecessary genital cutting of non-consenting girls would be uniformly forbidden. That is, it would be forbidden regardless of whether the cutting is characterized (by some) as being “cosmetic” or “cultural” in nature7 and without distinction as to the girl's race, ethnicity, immigration status, parental religion, or other such features.

If the WHO were to take this approach, it might neutralize accusations of racism, cultural imperialism, and moral double standards, at least with regard to FGC. But it would not address concerns about other vulnerable persons who also face non-consensual genital cutting. These include children who may be categorized as either female or male at birth who have certain intersex traits, sometimes called differences of sex development or variations of sex characteristics (Monro et al., 2017; Carpenter, 2018a), and children who, at birth, do not appear to have such traits and are categorized as male.8 A growing number of scholars argue that an age limit or consent criterion should be applied to these children too (Tangwa, 1999; Toubia, 1999; Lightfoot-Klein et al., 2000; Mason, 2001; Ehrenreich and Barr, 2005; Darby, 2013; Svoboda, 2013; Ungar-Sargon, 2015; Earp, 2016b; Svoboda et al., 2016; Steinfeld and Earp, 2017; Chambers, 2018, 2022; BCBI, 2019; Reis, 2019; Townsend, 2020, 2022; Bootwala, 2022).

In fact, the WHO has, in at least one published report, referred to medically unnecessary intersex genital cutting (IGC) as a form of “abuse” if performed on minors without their consent, thus appearing to recognize the moral importance of consent in evaluating the permissibility of non-therapeutic genital modifications in children (WHO, 2015). However, despite the extraordinary oppression faced by intersex people in many countries, the WHO has not led a concerted effort to eliminate such non-consensual IGC (Ehrenreich and Barr, 2005; Jones, 2017; Earp et al., 2021). Regarding male genital cutting (MGC), although the WHO firmly opposes all non-Western-associated FGC (Table 1), including non-tissue-removing forms (e.g., sanitized “nicking” of the clitoral foreskin or prepuce undertaken for religious purposes) (Bootwala, 2019; Shweder, 2022b, 2023), it does not condemn any form of medically unnecessary MGC, including relatively severe and unhygienic forms, irrespective of how much healthy genital tissue is damaged or removed.

This latter inconsistency is particularly striking given that, wherever non-Western-associated FGC is performed, MGC is virtually always performed within the same communities, typically on children of a similar age under comparable conditions (DeMeo, 1997; Abdulcadir et al., 2012; Johnsdotter, 2018; Šaffa et al., 2022). In other words, wherever girls are cut for cultural or religious reasons, whether in a modern clinic or a rural homestead, their brothers are cut as well (but not vice versa). It has been estimated that 13.3 million boys and 2 million girls are “circumcised” every year (Denniston et al., 2007). The motivations for cutting overlap between the sexes and the rites often serve complementary social functions as I detail below.

Regarding physical outcomes or harms, depending on the community and the subtypes of cutting that are customary within it, either the male or female version of the ritual may be more physically severe, damaging to sexual experience, or have a higher risk of medical complications. As Debra DeLaet (2009) argues,

there are sharp differences between infibulation, the most extreme form of female genital mutilation, and the less invasive form of male circumcision that is most widely practiced. However, that comparison is not necessarily the most appropriate comparison that can be made … there are extremely invasive forms of male circumcision that are as harsh as infibulation [and while it is true] that these extreme forms [are relatively rare] it is also the case that infibulation is much less common than the less invasive variants of female circumcision. (pp. 406-407)

Indeed, according to DeLaet, “female circumcision as it is commonly practiced can be as limited in terms of the procedures that are performed and their effects as the most widespread type of male circumcision” (DeLaet, 2009) (p. 407). Taking a similar view, Nahid Toubia, the pioneering Sudanese surgeon, women's health advocate, and longtime campaigner against FGC, has stated that in many cases, “female circumcision actually results in less functional impairment and fewer physical complications than male circumcision” (Toubia, 1999) (p. 4). This appears to be the case, for example, in many Muslim communities throughout South and Southeast Asia, where religiously-inspired circumcision (i.e., cutting of the genital prepuce; see Box 2) is a gender-inclusive rite, where both forms have been largely medicalized, and where the female form is often less physically substantial than the male form (Rashid et al., 2010; Rogers, 2016; Bhalla, 2017; DBWRF, 2017; Bootwala, 2019; Rashid and Iguchi, 2019; Wahlberg et al., 2019; Dawson et al., 2020; O'Neill et al., 2020; Shweder, 2022a,b, 2023).9

Box 2. Overview of the human prepuce. Box adapted from Myers and Earp (2020) and Earp (2022a).

The term “circumcision” can refer to cutting or removing part or all of either the male or female prepuce. The genital prepuce or foreskin is a shared anatomical feature of both male and female members of all human and non-human primate species (Cold and Taylor, 1999). In humans, the penile and clitoral prepuces are undifferentiated in early fetal development, emerging from an ambisexual genital tubercle that is capable either of penile or clitoral development regardless of genotype (Baskin et al., 2018). Even at birth—and thereafter—the clitoral and penile prepuces may remain effectively indistinguishable in persons who have certain intersex traits or differences of sex development (Pippi Salle et al., 2007; Hodson et al., 2019; Grimstad et al., 2021). The penile prepuce has a mean reported surface area of between 30 and 50 square centimeters in adults (Werker et al., 1998; Kigozi et al., 2009) and it is the most sensitive part of the penis, both to light touch stimulation and to sensations of warmth (Sorrells et al., 2007; Bossio et al., 2016). The clitoral prepuce, while smaller in absolute terms, is continuous with the sexually-sensitive labia minora; it is also an important sensory platform in its own right, and one through which the clitoral glans can be stimulated without direct contact (which can be unpleasant or even painful) (O'Connell et al., 2008). Regardless of a person's sex, the prepuce is “a specialized, junctional mucocutaneous tissue which marks the boundary between mucosa and skin [similar to] the eyelids, labia minora, anus and lips … The unique innervation of the prepuce establishes its function as an erogenous tissue” (Cold and Taylor, 1999) (p. 34). It has been argued that, insofar as one assigns a positive value to the prepuce, or to the ability to decide for oneself whether such delicate genital tissue should be cut or removed, circumcision, whether of boys or of girls, necessarily harms the child to that extent, irrespective of medical risks or complications (Svoboda, 2017).

In short, the harms of genital cutting vary widely, both within and between cultures, and they do so in a way that is not reliably predicted by the sex of the affected child (Androus, 2013). That FGC in Global South settings can be medically dangerous, and sometimes deadly, is well-documented and commonly known (Obermeyer, 1999, 2003, 2005; WHO, 2008; Berg and Denison, 2012; Berg and Underland, 2013; Berg et al., 2014). As the case of Egypt shows, even in countries where most girls are cut by doctors with sterile instruments, deaths associated with FGC—due to shock, infection, sudden loss of blood pressure, or even an overdose of anesthesia—are known to occur. At least four such cases have captured the attention of national and international media in recent years (Meleigy, 2007; Al Arabiya, 2013; Al Sherbini, 2016; BBC, 2020).

By contrast, the fact that MGC within Global South settings can also be, and often is, comparably or even more dangerous has not been as widely discussed (nor, for that matter, have the risks associated with female genital “cosmetic” surgeries, intersex genital cutting, or routine penile circumcision in the Global North, although these, too, can be substantial) (Beh and Diamond, 2000; Creighton, 2001; Diamond and Garland, 2014; Darby, 2015; Earp et al., 2018; Fahmy, 2019; Learner et al., 2020; Gress, 2021; Kalampalikis and Michala, 2021; Schröder et al., 2021). To illustrate, health department records from the Eastern Cape region of South Africa show that more than five thousand Xhosa boys required hospitalization due to their traditional circumcisions between 2006 and 2013; there were 453 recorded deaths among initiates within this time period and 214 circumcision-related penile amputations (Meissner and Buso, 2007; Meel, 2010; Douglas and Nyembezi, 2015). These amputations, which ensue from circumcision nearly every cutting season, are sufficiently common that there is now an established literature debating the ethics of using government resources to pay for attempted penile transplantations (Moodley and Rennie, 2018; van der Merwe, 2020; van der Merwe et al., 2021).10

This is not to suggest that comparative harm judgments could ever suffice for a moral or political analysis of these practices; rather, it is to dispel a common empirical misunderstanding, namely, that FGC and MGC can be clearly distinguished on the basis of the respective damage they cause to health or sexuality. Indeed, from a human rights perspective, the perspective ostensibly adopted by the WHO, the relative harmfulness of genital cutting under various conditions does not determine its moral permissibility. Instead, a focus on rights might suggest that non-consenting persons (per se), including insufficiently autonomous children, have a moral—and in many countries also a legal—right against having their sexual anatomy interfered with, to any extent, whether surgically or otherwise, unless it is medically necessary11 to do so (Archard, 2007; Bruce, 2020; Bruce et al., 2022). If that is correct, a child is automatically wronged—that is, their rights are violated—by any and all such genital interference, irrespective of how harmful or even beneficial (e.g., physically, psychosocially, or spiritually) a third party intends or expects the cutting to be.

That is the position I take in my own work, at least with regard to the cultures with whose political histories, social institutions, and ethicolegal norms I am most familiar, primarily in North America, Australasia, and Europe.12 However, I argue that the right in question, insofar as it is recognized, must apply to all non-consenting persons irrespective of their sexual anatomy or socially assigned gender role (Earp, 2021b, 2022a,b). According to this approach, one cannot determine the moral acceptability of genital cutting based on an individual's sex or gender, nor can it be determined by making an empirical prediction about how harmful the cutting is likely to be. In addition to inherent problems with trying to “measure” harm-levels associated with genital cutting, whether physical or psychological, there is also the problem of coming to a principled agreement as to how much harm, or risk of harm, should be considered “too much” for a child to suffer as a result of a medically non-indicated surgery (i.e., before the operation is regarded as unacceptable).

But there is a deeper problem. And that is that one and the same type of cutting, under the same conditions (whether clinical or non-clinical), can have radically different implications for well-being depending on the affected person's attitudes, beliefs, and values (Einstein, 2008; Earp and Darby, 2017; Earp and Steinfeld, 2018; Connor et al., 2019; Abdulcadir, 2021; Johnson-Agbakwu and Manin, 2021; Tye and Sardi, 2022). Put differently, the level of harm a person experiences by virtue of having their sexual anatomy non-consensually cut or altered is not simply a function of how physically severe the cutting was, or whether there were surgical complications. Rather, for many persons subjected to medically unnecessary genital cutting, even supposedly minor forms, it is the mere fact of having been judged “imperfect,” “impure,” or “incomplete” as a child, and (therefore) unwillingly subjected to a surgical operation—targeting a part of the body that is culturally constructed as being especially intimate or personal—that engenders feelings of harm and even sexual violation (Dreger, 1999; Hammond and Carmack, 2017; Taher, 2017). How much harm the person feels, or will feel, on such a basis, cannot be predicted in advance, as it depends on culturally and individually variable interpretive frameworks (Johnsdotter, 2013).

In its policies and materials on FGC, the WHO gives a cluster of reasons for opposing the practice, without clarifying which of the reasons, or combination of reasons, is necessary or sufficient to make it a rights violation. Nevertheless, it stresses that the practice—regardless of type—is condemnable due to the following: it involves the cutting or removal of healthy, functional tissue from the sexual anatomy of a vulnerable individual; it is medically unnecessary; it is usually very painful; it risks various complications, both physical and psychological; and it is typically performed on pre-autonomous minors, making it (presumably in conjunction with one or more of the other factors) “a violation of the rights of children” (WHO, 2020b). As Hope Lewis writes, this reasoning is common among human rights advocates primarily situated in the Global North: “From the perspectives of non-practicing cultures, the primary ethical basis of universal concern about [FGC] is that it involves the infliction of great physical pain and the risk of life-threatening complications for infants and children, whose well-being is of special legal and moral concern in both practicing and non-practicing cultures” (Lewis, 1995) (p. 19, emphasis added).

As demonstrated in Box 3, each of these concerns applies with equal force to MGC in the same societies where FGC is carried out, as well as to MGC in other societies, where only boys are cut. Moreover, the WHO is aware of this fact, as the information presented in Box 3 is derived from its own 2009 report on “Traditional Male Circumcision Among Young People” (WHO, 2009).

Box 3. What the WHO knows about the harms and circumstances of “traditional” MGC.

In its report on “traditional” MGC, the WHO acknowledges that, as with FGC, “complications associated with male circumcision, including long-term morbidity and death … have not been systematically assessed.” Nevertheless, it cites a 35% complication rate for traditional male circumcision, with wound infection and delayed wound-healing (more than 60 days) being common (WHO, 2009) (p. 4). Other “serious sequelae in the traditional groups were persistent swelling, extensive scarring, and loss of erectile function” (WHO, 2009) (p. 27).

More generally, the WHO is aware of “reports of appalling complications after male circumcision,” “forced male circumcision through the abduction of boys” in multiple African countries, “reactive depression” of boys following circumcision, homophobia associated with male circumcision rites, and “reporting of suicide in some cases” (p. 13). The WHO states that in some communities, boys “face ritual circumcision without any encouragement or social support” (ibid.).

In the same report, the WHO affirms that boys are “expected to tolerate” the pain of circumcision “without showing any weakness” and that participation is rarely voluntary: as with FGC, circumcision is “usually not an optional procedure to be decided about on an individual basis” (p. 12). Indeed, “the social pressure to undergo circumcision puts uncircumcised boys at risk of ostracism,” which, in the relevant circumstances, can be a life-endangering proposition (p. 14). Moreover, “women are reported as actively influencing” adolescents boys' decisions to be circumcised (p. 14), with one of the “main” reasons cited being the belief that circumcised men will give them more sexual pleasure. In many African communities, “no self-respecting” girl would marry an “uncircumcised” male, leaving few options for boys who would refuse the rite (ibid).

Finally, the WHO reports that in some contexts, boys experience “bullying and beatings” until they agree to be circumcised; however, hospital circumcisions are considered to be ritually inadequate: “particularly because of the use of anesthesia and the avoidance of pain, which is considered [a] central aspect of the traditional ritual” (p. 21). The WHO concludes that severe stigmatization of boys who do not want to be circumcised “limits the freedom of choice regarding circumcision” (ibid.).

So, what has been the WHO's policy in this area? In the case of “traditional” MGC, the WHO advises that it should preferably be done in a clinical setting or with sterilized equipment to make it safer, taking a harm-reduction approach. Indeed, the WHO has published its own training manual for healthcare providers on how to successfully medicalize the practice. The manual gives explicit, step-by-step instructions with accompanying photographs, showing how to perform medically unnecessary penile circumcisions on non-consenting boys, while touting a new surgical device for doing so invented and patented by an author of the manual (WHO, 2010).13

At the same time, the WHO categorically opposes medicalization of any type of FGC, including forms that are less physically substantial than the penile circumcisions performed in certain cases within the same families, as illustrated earlier with the gender-inclusive Islamic ritual common in parts of South and Southeast Asia (Rashid and Iguchi, 2019; Dawson et al., 2020; Rashid et al., 2020). The WHO fears that medicalizing even such “minor” FGC (e.g., nicking, pricking, or partial removal of the female foreskin or labia without clitoral glans modification) might “legitimize” the practice (WHO, 2020b):

In many settings, health care providers perform FGM due to the belief that the procedure is safer when medicalized. WHO strongly urges health care providers not to perform FGM. FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women.

Thus, the WHO argues that medicalizing FGC risks “legitimizing” a ritual practice that is internationally recognized to violate human rights—perhaps most saliently, the right to bodily integrity—irrespective of cutting severity or any health-related outcomes. This suggests that it is not the medical risk level, degree of harmfulness, anticipated adverse effects on health or sexuality, or any other such contingent empirical feature that grounds the status of medically unnecessary FGC as being a violation of this purported human right. Instead, according to the WHO, or at least implicit within its statements and claims, it is the simple fact of cutting into a vulnerable person's sexual anatomy, when there is no relevant medical emergency, that makes FGC a rights violation (perhaps especially when the person cannot consent).

Given its widely noted commitment to the principle of non-discrimination on the basis of sex, it might seem that the WHO should therefore regard any act of genital cutting that shares these features to be a violation of the human right to bodily integrity. Both MGC and FGC, to quote now directly from the WHO policy on the latter, involve “[t]he removal of or damage to healthy, normal genital tissue [risking] several immediate and long-term health consequences,” can be “painful and traumatic,” and are “nearly always carried out on minors,” often within the same communities (WHO, 2008) (p. 1). A puzzle is therefore raised as to why the WHO treats one of these practices as a fundamental human rights violation in all its forms, while the other type is not treated as a human rights violation in any of its forms. The situation is puzzling because human rights, by definition, apply to all humans; that is, they apply regardless of sex.14

Instead, paradoxically, as the anthropologist Kirsten Bell has noted, the WHO seeks “to medicalize male circumcision on the one hand, oppose the medicalization of female circumcision on the other, while simultaneously basing their opposition to the female operations on grounds that could legitimately be used to condemn the male operations” (Bell, 2005) (p. 131).

These and other inconsistencies threaten to damage the credibility of the WHO and undermine its perceived authority to pronounce on human rights. This, in turn, may have implications for the global campaign against FGC, given that the campaign increasingly relies on human rights-based arguments rather than solely, or even mainly, on health-based arguments (Shell-Duncan, 2008). As the WHO acknowledges, the latter type of argument may tend to foster medicalization of FGC, or a transition to its less severe forms, rather than the wholesale abandonment of the practice as the WHO prefers (Askew et al., 2016). In short, whatever one thinks of the legitimacy of the WHO's policy goals in this area, if the organization is to be taken seriously on matters of genital cutting, whether scientifically, politically, or morally, these inconsistencies must be addressed.

One way the WHO might seek to address the aforementioned inconsistencies would be to deny that they are based on double standards. A common way to do this has been to suggest that FGC, either typically or on balance, is far more harmful than MGC, often by making appeals to Western stereotypes of the practices that are based on very different exemplars. Plausibly, these contrasting stereotypes stem, in part, from greater cultural familiarity with MGC in Western countries, especially in the United States, where MGC—but not FGC—is a medicalized birth custom associated with concepts of hygiene (Wallerstein, 1985; Gollaher, 1994; Hodges, 1997; Darby, 2016). In addition, Jewish religious MGC has also been familiar to Western culture for many centuries.15 By contrast, since the 1970s, FGC has been linked in Western discourse to “African” culture, which is widely portrayed as being “primitive” or “barbaric” (Bader, 2019; Abdulcadir et al., 2020; Bader and Mottier, 2020). A major aspect of this “othering” portrayal has been a disproportionate focus on the most drastic forms of FGC done in “traditional” settings, while ignoring both (1) the less drastic, medicalized forms of FGC that are common in many Global South countries, and (2) the comparatively dangerous, “traditional” forms of MGC that co-occur with their female counterparts.16 As we have seen, however, when the full range of practices across cultures is taken into account, and relevantly similar cases compared, a harm-based analysis of health outcomes cannot justify the WHO's categorically differential treatment of the two types of cutting.

What about health-related benefits, then? According to this approach, the WHO could appeal to potential health benefits associated with MGC, while maintaining that FGC has “no health benefits, only harm” (WHO, 2020b). As noted previously, the WHO has indeed relied on this argument to distinguish its apparently conflicting policies on genital cutting, so it merits some comment here.

Recall that, according to the WHO, MGC, in the form of penile circumcision, “has significant health benefits that outweigh the very low risk of complications when performed by adequately-equipped and well-trained providers in hygienic settings” (WHO, 2008) (p. 11). The WHO goes on to cite evidence of a reduced risk for circumcised males, but not their partners, of acquiring heterosexually transmitted HIV in settings where transmission of this kind is epidemic (the trial looking at male-to-female transmission was stopped early for futility, as the female partners of circumcised males were contracting HIV at a higher rate; the WHO does not mention this trial).17

Note the multiple qualifiers, in the previous paragraph, in the quote from the WHO after “when.” In trying to establish a categorical difference between FGC and MGC, the WHO picks out a very specific type of MGC, namely the type that is culturally familiar to Western countries, primarily through exposure to the medicalized version of the practice that is customary in the United States. When it illustrates “FGM,” by contrast, it highlights the least sanitary forms of the practice, done in the most coercive ways, with the most disabling physical outcomes, while simultaneously urging that these forms not be medicalized (Gruenbaum, 2005). According to Dr. Tatu Kamau, a Kenyan physician who advocates for equal legal treatment of male and female genital cutting, such an approach “absurdly prevents women from accessing quality health services and then blames them for risking their lives. This asymmetry [is] all the more questionable considering that during circumcision, both males and females run the same immediate surgical risks of uncontrolled bleeding, shock and sepsis yet males are privileged to have these risks mitigated but females are not” (Ahmadu and Kamau, 2022) (p. 32).

As for the claim that the health benefits of male circumcision outweigh the risks, that is, in part, a value judgment (Savulescu, 2015; Frisch and Earp, 2018), and it is not a judgment that is universally shared among relevant authorities. In fact, it is the minority position among national-level medical societies to have formally considered the question: only U.S.-based bodies have joined the WHO in attributing net health benefits to (especially newborn) MGC (FMA, 2008; KNMG, 2010; RACP, 2010; AAP, 2012; Frisch et al., 2013; CPS, 2015; Earp, 2015a; Earp and Shaw, 2017; DMA, 2020; Deacon and Muir, 2022). But suppose the claim is simply granted. The alleged net health improvement the WHO ascribes to medicalized MGC under ideal clinical conditions obviously does not apply to so-called “traditional” MGC, which, by contrast, has an extremely high rate of morbidity and mortality that would more than nullify any claimed health benefit (see Box 3). However, the WHO does not condemn any type of MGC as a rights violation, including its most dangerous and unhygienic forms, even when these are carried out on non-consenting children. Instead, it urges that the more dangerous forms be medicalized, as noted previously. By contrast, as we saw, the WHO opposes medicalization of FGC, arguing that such attempts at harm-reduction would be unethical: the practice is, in its view, inherently a human rights violation, irrespective of medical outcome or even the affected person's own consent (Shell-Duncan, 2001; WHO, 2008, 2020b; Askew et al., 2016). It stands to reason, then, that, even if “FGM” did have statistical health benefits similar to those that have been attributed to MGC, the WHO would not switch to supporting it.

This can be seen by drawing an analogy, taking MGC first. The data regarding HIV-related health benefits for MGC come from studies of adult men in sub-Saharan Africa who, ostensibly, gave their free and informed consent to undergo penile circumcision, hoping this would reduce their risk of acquiring HIV. The population-level effectiveness of such circumcision as a form of prophylaxis against HIV remains contested (Garenne et al., 2013; Rosenberg et al., 2018; Garenne and Matthews, 2019; Loevinsohn et al., 2020; Luseno et al., 2021; Garenne, 2022), perhaps because one's risk of contracting a sexually transmitted virus has more to do with behavioral and social-structural considerations than with anatomical factors such as the presence or absence of healthy genital tissues (Aggleton, 2007; Norton, 2013, 2017; Parker et al., 2015; Earp and Darby, 2019; Fish et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, the WHO has cited these HIV-related data to justify not only the voluntary circumcision of adult men, as might be expected, but also the circumcision of young boys—including infants in the U.S. American style—in populations that do not traditionally practice genital cutting (WHO, 2010). In fact, a “large proportion” of the now more than 25 million medicalized circumcisions that have taken place in Africa since 2007, promoted as prophylaxis by the WHO and substantially funded by the U.S. government, have been carried out, not on consenting adults, but on underage boys between the ages of 10 and 14 (WHO, 2020a).18

To complete the analogy, let us now turn to FGC. Suppose there were equivalent data suggesting an HIV-protective effect of adult, consensual FGC—labiaplasty, say—in women. It is inconceivable that the WHO would cite these data as a justification for surgically removing non-diseased labial tissues from healthy newborns or even 10–14 year-old adolescent girls. Instead, as I have suggested elsewhere, the WHO would likely argue as follows: “healthy, nerve-laden genital tissue (a description that applies as much to the penile foreskin as it does to the labia) is valuable in its own right, so that removing it without urgent medical need is itself a harm; [it] would stress that all more conservative means of addressing potential infection should be exhausted before surgery is employed; and [it] would insist that girls have an inviolable moral right against any medically unnecessary interference with their private, sexual anatomy to which they themselves do not consent when of age” (Earp, 2021a) (p. 6).

To summarize, the health benefits attributed to “medicalized” MGC—even if they are simply granted—do not apply to so-called “traditional” MGC, which the WHO does not condemn regardless of risk-level or consent. In any case, the data that are cited in support of these benefits come from studies of consensual adult surgeries, not non-consensual surgeries performed on minors: the data cannot, whether scientifically or ethically, simply be transposed to children. Finally, the benefits themselves can be realized more effectively in alternative ways that do not require genital surgery (such as regular condom use), making this a morally inappropriate option for pre-autonomous minors. This can be seen, I have suggested, by imagining that WHO-defined “FGM” did have health benefits comparable to the ones that have been attributed to medicalized MGC. If that were so, would the WHO conclude that the practice no longer counted as an instance of genital mutilation, nor violated human rights, even if it were imposed on pre-autonomous girls? It does not seem likely.

Empirical questions, therefore, concerning health benefits or harms will not be the focus of the rest of this paper. Instead, I will now consider whether the WHO can defend its selective opposition to non-Western-associated FGC by appealing to a distinctive role for such FGC in upholding patriarchal gender systems and furthering sex-based discrimination.

According to the WHO, all non-Western-associated FGC “reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes, and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women” (WHO, 2008) (p. 1). The implied corollary is that MGC does not reflect deep-rooted inequality between the sexes nor constitute sex-based discrimination. In other words, FGC might be thought to symbolize or even actively reinforce the subordinated status of women and girls, making it a highly objectionable practice, whereas boys on this view are not similarly demeaned or disadvantaged by MGC, so it is less of a problem (if a problem at all). In fact, MGC is sometimes said to benefit boys by elevating them into positions of power, thereby granting them access to special social privileges (Dorkenoo, 1994). It is therefore entirely appropriate, according to this perspective, that global campaigns against genital cutting should aim to help women and girls but not boys.

I argue that this view is mistaken, not only empirically and conceptually, but also politically and morally.

The empirical and conceptual flaws can be summarized as follows. First, with respect to the claim that non-Western-associated FGC constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women, one must rehearse the point that, as far as anthropologists are aware, women and girls are rarely if ever19 exclusively targeted for genital cutting, whereas, by contrast, boys in many cultures are so targeted (Abdulcadir et al., 2012; Šaffa et al., 2022; see also Gruenbaum et al., in press). In such “MGC-only” cultures, moreover, while boys may be advantaged along some dimensions, they are specifically disadvantaged by genital cutting, specifically because they are boys. In other words, because they were designated male at birth and raised as boys, rather than as female and raised as girls, they (and only they) must submit to a physically risky and often intentionally painful intervention into their sexual anatomy, or else face potentially severe social sanction (Schlegel and Barry, 2017).

Of course, girls in such societies may be significantly disadvantaged in various other ways. And it can readily be agreed that, wherever girls are disadvantaged along some dimension simply because they are girls, this should be a matter for serious concern and needs to be addressed. Here, however, we are evaluating the claim that women and girls are discriminated against by virtue of having their genitals cut, thus potentially justifying the WHO's selective condemnation of non-Western-associated FGC. That claim appears not to be true.

Nevertheless, it might still be argued that, even if girls are not singled out for genital cutting, whereas boys often are; and even if, because of their gender, boys in some cultures are significantly disadvantaged by genital cutting in particular (whereas girls in those same cultures are spared that particular disadvantage), FGC is still uniquely problematic on other grounds having to do with gender inequality. For example, it could be argued that FGC, and only FGC, reflects and reinforces a lower status for women and girls in the societies where it is practiced, despite being practiced alongside MGC.

Efua Dorkenoo, the great Ghanaian-British campaigner against FGC, is one of many prominent voices to have advanced such a claim. In her classic book Cutting the Rose, she begins by acknowledging that there are at least some similarities between, in her terms, “FGM and male circumcision,” and also between “the rites of passage” into adulthood for girls and boys in many African communities. She writes: “Certainly the two procedures are related. Both are widely practiced without medical necessity and in both cases children go through a traumatic experience. Both are performed on children without their consent.” But, she continues, “there the parallel ends.” With respect to symbolic meanings, she stresses that

the content of male rites of passage is geared toward training young boys to develop skills associated with power and control, not to reinforce their submissiveness and to make them feel they are second-class citizens as is done in the female initiation (Dorkenoo, 1994) (p. 52).

Therefore, Dorkenoo seems to suggest, it is not so important to criticize the boys' “traumatic” rite.

Such a conclusion, however, does not follow. As LeYoni Junos argued more than 20 years ago, where FGC and MGC are practiced together as parallel rites of initiation, “the initiation of both boys and girls have a codependency. The males in the community cannot have power and control unless there is someone to be controlled. Equally, female submissiveness can only be reinforced if there is someone to be submissive to; i.e., someone (male) exerting power and control” (Junos, 1998) (p. 11, emphasis in original). To break this codependency, she argues, both male and female genital cutting of children must be opposed.

The key word here is “both,” not one or the other. From the perspective of gender equality, it would be no more appropriate to selectively condemn MGC than it is to selectively condemn FGC, simply as a matter of principle. However, more than abstract principles are at stake. In fact, as I will now argue, women and girls may be actively harmed by the WHO's “single sex” approach to addressing medically unnecessary child genital cutting. This harm is based, in part, on a failure to understand the multiple meanings, motivations, intentions, and functions of FGC in the diverse societies where it is practiced (Thomas, 1996; Yoder et al., 1999; Shell-Duncan and Hernlund, 2000; Baumeister and Twenge, 2002; Robertson and James, 2002; Dellenborg, 2007; Kratz, 2010), not least because, by ignoring the concurrent rite for boys, FGC is inaccurately and misleadingly reduced to “discrimination” (WHO, 2008).

The reality is not so simple. Not all of the social meanings and functions of FGC are straightforwardly bad for women and girls—at least not under the arguably non-ideal conditions in which boys are also cut—and nor do they necessarily reflect a subordinated status. Instead, where deliberately harsh MGC rites enable men to form politically powerful bonds amongst themselves, created in part through their shared experience of genital cutting20 (Schlegel and Barry, 2017), FGC appears to have arisen in some cultures as a parallel rite that is then invariably led by women. And like its male counterpart, the female rite serves to promote within-sex bonding, communal network-building, and power consolidation, thereby weakening other-sex domination in various spheres (Grande, 2009; Ahmadu, 2010, 2016a; Prazak, 2017).

In fact, some scholars suggest that FGC may have culturally evolved in reaction to, or in conjunction with, male-oriented rites in certain gender systems, as an offsetting force or power-neutralizer (Caldwell et al., 1997; Leonard, 2000b; Knight, 2001; Silverman, 2004; Moxon, 2017). According to a recent global phylogenetic analysis conducted by Gabriel Šaffa and colleagues, over the course of human history, FGC has almost exclusively emerged in societies that were already practicing MGC. The result has often been a co-equal platform for girls, like boys, to gain social status through displays of courage, maturity, and the ability to withstand pain, while showing respect for authority and communal institutions (Šaffa et al., 2022). Indeed, even the potential exceptions to this pattern (i.e., of FGC emerging or persisting only alongside MGC) may end up proving the rule. Support for this possibility comes from the Hadza of Tanzania, a primarily hunting and foraging people. Ironically, the Hadza may be one of the few—perhaps the only—society on record in which FGC, but not MGC, is traditionally practiced. Far from being patriarchal, however, the Hadza are “famously egalitarian” (Power, 2015) (p. 339). If FGC serves primarily to subordinate women and girls, how could that be so? The answer is revealing. The Hadza practice a linked pair of gender rituals, one male-oriented and the other female-oriented, in which members of both sexes engage in “costly signaling”—including genital cutting in the case of women—to demonstrate their commitment to the group. The male ritual, epeme, confers certain sacred privileges, however, which is seen as “discordant” in a society where men have very little authority over women in daily life. To explain how such ritual male privilege could co-exist with a deep-rooted lack of male control over women, Camilla Power posits that the female rite, maitoko, acts as a “counterbalance: women-as-a-group contesting and answering men's ritual claims” (Power, 2015) (p. 353). In particular, she argues that the women's intense, painful, and emotionally transformative rite is a vital source of female bonding and solidarity formation that operates to counteract male power and thus “maintain egalitarianism” (Power, 2015) (p. 354).

Taking a broader view, anthropologists have argued that FGC rites in some societies, whether functioning as rites of passage or so-called instituting rites,21 may thus serve to undermine gender inequality (Leonard, 2000b; Shweder, 2002; Grande, 2009; Ahmadu, 2010; Abdulcadir et al., 2012; Prazak, 2017; Dellenborg and Malmström, 2020). Elisabetta Grande, for example, argues that in many cases, the women-led FGC rites are such crucial sources of “group solidarity, mutual aid, exchange and companionship, that [they may act as] the primary and most important form of resistance against male dominance” (Grande, 2009) (p. 15).22

Thus, rather than simply being a means of oppressing girls, as implied by the WHO, FGC rites in some societies appear to serve as politically important sources of power for women—just as the MGC rites often do for men. Ironically, then, the WHO's selective targeting of the female rites may actually “weaken female power centers within society and bring women's bodies and lives under the hegemonic control and management of local male religious or political leaders” (Abdulcadir et al., 2012) (p. 23). Meanwhile, as MGC is not targeted for condemnation, the men are free to continue their own initiations, training up the next generation of boys to assume the aforementioned leadership positions, often through stoical displays of patriarchal masculinity (as I describe next).

To summarize, it may be the WHO's selective opposition to FGC rituals in societies that initiate girls and boys together, more so than the rituals themselves, that discriminate(s) on the basis of sex (women, but not men, exposed to legal sanction for carrying out their valued traditions; girls, but not boys, protected from genital cutting) while simultaneously weakening female power centers (Grande, 2009; Abdulcadir et al., 2012) and diverting resources away from more pressing material needs—such as access to medicines, nutritious food, or clean water—thereby leaving women worse off overall (Gruenbaum, 2001).23

Strikingly, a more appropriate target of condemnation, from the perspective of promoting women's and girls' rights in FGC-practicing cultures, may in fact be the male-centered genital cutting rituals that occur in the same societies.

In these rituals, young boys are typically separated from their mothers and sisters, isolated from female friends and playmates, and socialized—often by means of an explicitly gendered trial of violence—to become “real men” (see Dembroff, 2022), where this is characteristically defined in terms of patriarchal norms of masculinity that promote the subordination of women and girls (Leonard, 2000a; Silverman, 2004; Schlegel and Barry, 2017; Mashabane and Henderson, 2020). Therefore, opposition to these male initiations and other MGC rites may be crucial for disrupting gendered socialization processes by which patriarchal hierarchies are reproduced (Kimmel, 2001; Prazak, 2017; Steinfeld and Earp, 2017; Meoded Danon, 2021).

Using the Xhosa of South Africa as an example, it has been argued that the prevailing patriarchal belief system embedded in Xhosa culture “contributes to the widespread gender-based violence in South Africa” (Mashabane and Henderson, 2020) (p. 163). Tellingly, these authors claim that the initiation rite for boys “explicitly instills norms of hegemonic masculinity” (ibid.). According to Alice Schlegel and Herbert Barry III, adolescent impressionability “facilitates intensive teaching of cultural beliefs and ideology, including the ideology of masculinity. If the ideal man is aggressive, subjecting boys to aggressive behavior by men is a vivid demonstration of that ideal” (Schlegel and Barry, 2017) (p. 15).

Domineering behavior is a common feature of such rites; similar observations have been made of the male initiation practices among the Kikuyu of Kenya (Njoroge et al., 2022), for example, or among various ethnic groups in Papua New Guinea (Kelly et al., 2012). In these and other MGC-practicing societies, young boys who fail to live up to the demands of “real man” masculinity often face bullying and harassment from older males to prove their manliness—a necessary component of which is surviving the MGC ritual (see Box 3). In fact, in many such societies, males are not considered men unless they have been circumcised in the ritually prescribed way; a non-circumcised male remains a “boy” regardless of age or maturity, and thus cannot marry or receive other social goods (Mavundla et al., 2010).

Accordingly, non-circumcised boys, along with other males who are perceived to violate “real man” standards (gay, disabled, or poor men, for example) are stigmatized, ridiculed, and marginalized—both by circumcised men and by women and girls24—unless and until they comply with their prescribed socialization (Weiss, 1966; Rowanchilde, 1996; Martí, 2010; Mavundla et al., 2010; Kelly et al., 2012; Mashabane and Henderson, 2020). Under such a regime, the only way to escape from this subordinated position (apart from suicide, which is not uncommon in the relevant contexts) is to undergo a painful genital cutting rite without flinching or showing signs of “weakness” (WHO, 2009). As a part of this, the initiate is forced to reject and repudiate any “feminine” aspects of his personality, character, or body (the foreskin is considered “feminine,” being soft and sensitive; this is part of why it must be cut off).25

According to research summarized by Schlegel and Barry III, such harrowing male rituals, and the teachings that accompany them,

force a cognitive reorganization, from attachment to and dependence on mothers and other women to denigration of them. [Boys may be] forcefully taken from the nurturing environment of their mothers' dwellings to the community men's house in which men spend most of their non-working time and may also sleep. In addition to the abrupt transition and the pain and fear they experience, boys are taught that women are dangerous. The initiation ceremony, emphasizing women's pollution [and] the need to remove it, prepares the boys to denigrate women, particularly women of reproductive age … By learning that women are polluting and dangerous, they come to fear women and feel revulsion at female bodies and to realign their attachment from mothers and sisters to males (Schlegel and Barry, 2017) (p. 16).

As a part of this transformation, boys must learn to assume a dominant gender role, which means domination over women and girls—as well as non-circumcised boys, gay men, and other perceived failures of masculinity (Junos, 1998; Mashabane and Henderson, 2020). And so the cycle continues. Thus, I conclude, the MGC ritual in many FGC-practicing societies (as well as in some societies where FGC is not practiced) is a major cultural mechanism through which female-subordinating gender hierarchies and associated ideologies are reproduced. Accordingly, insofar as the WHO is concerned about genital cutting practices that “reflect deep-rooted inequality between the sexes”—one of the main reasons for its condemnation of non-Western-associated FGC—it should similarly oppose and condemn ritual MGC in the same (and other) societies.

Much of what I have synthesized here has been said, in one way or another, by many other scholars before me. Indeed, there is a large and longstanding body of research—within anthropology, gender studies, post-colonial feminism, and other areas—that has highlighted the WHO's inaccurate, sensationalized, and essentializing characterizations of non-Western-associated FGC. All of this research is well-known to scholars of genital cutting and is readily available to the WHO. Yet as Michela Fusaschi writes:

Ignoring much of this research, the WHO has persisted in cordoning off and defining only non-Western-associated female-only genital modification as a grave human rights abuse, except when performed for ‘medical reasons.' Much of the academic literature, journalistic coverage of the topic, and international policy and law approaches to genital modification have taken their cue from the WHO (Fusaschi, 2022) (p. 2).

This has led to an unfortunate situation whereby “common knowledge” of non-Western-associated FGC, especially in relation to MGC, does not constitute knowledge at all, but rather highly skewed impressions and incorrect inferences based on stereotypes and selective examples. Moreover, this “common knowledge” is not merely mistaken, or randomly erroneous; rather, it is systematically biased in a way that preserves the status quo of unequal power relations between certain countries and cultures in the arena of global health and human rights governance (Shweder, 2002; Njambi, 2004; Boddy, 2007; Earp, 2016a; Shahvisi, 2021).

This is not an abstract or theoretical point. Rather, there has been fine-grained sociological research into the relevant decision-making processes of human rights “gatekeepers” at the WHO and other Global North agencies. Charli Carpenter (2014), who has conducted such research, notes that the perceived acceptability of different genital cutting practices tracks the personal or familial commitments/customs of the decision-makers themselves.

Notably, MGC of non-consenting minors, specifically non-therapeutic penile circumcision, is a majority birth custom in the United States, the country with the greatest influence on the WHO. This influence extends to the personnel who are directly involved in setting the global human rights agenda, a disproportionate number of whom are U.S. Americans. As such, “the practice [of MGC] is prevalent in their own social networks” (p. 138). Carpenter reports that, “unlike many other practices human rights professionals condemn but do not participate in, the practice of circumcision was widespread” among her interview subjects. Confronting this fact “evoked defensiveness from those who had circumcised their own [male] children and were loath to think of themselves as human rights abusers” (p. 139).

Hope Lewis has drawn a similar connection: “Because male circumcision is a far more accepted practice among Western groups—whose cultural norms have significantly shaped human rights instruments and norms—it is rarely considered an appropriate subject of human rights concern” (Lewis, 1995) (p. 6). Ditto Zachary Androus: “The normalization of male circumcision in Anglophone society was a necessary condition for the emergence of the paradigmatic gender distinction that characterizes [Western] cultural, social, and political responses to African genital modification practices” (Androus, 2013) (p. 277).

These sorts of analyses suggest that U.S.-based human rights campaigners may suffer from a cultural illusion, simply failing to connect the dots between, on the one hand, their cited reasons for opposing all non-Western-associated FGC, regardless of severity, and, on the other hand, the practice of MGC that is happening in their own back yard. However, the Egyptian feminist Seham Abd el Salam (1999) (all quoted material from section III.C.a) has argued that such selective opposition to FGC is not due to simple ignorance or a failure to have considered the connections to MGC. Rather, she suggests that such “pragmatic” or inconsistent proponents of the human right to bodily integrity have made an “unwritten deal with … conservative social forces” to allow MGC to go unquestioned:

The terms of this unspoken deal imply that pro-bodily integrity activists accept some conservative practices, such as [MGC] that provides symbolic carving of traditional masculinity, in exchange [for] letting the activists oppose [FGC], which is a traditional … symbolic carving of femininity.

The bargain thus rests on a certain logic that takes for granted patriarchal gender asymmetries, with MGC as the immovable foundation. The logic, according to Abd el Salam, rests on the heightened status or worth of male children within patriarchal social systems. She writes: “given that male children are particularly valued by patriarchal family systems, [MGC] is significant to replicate the terms of the patriarchal hierarchy, which requires submission of lower to higher rank groups.” This includes not only rankings based on gender (men dominating women) but also based on age (men dominating boys and women dominating girls). Thus, the practice of involuntary MGC of young boys acts as a type of “age discrimination” with more powerful adults asserting their control over the bodies of the next generation. This serves to uphold social hierarchies because it “socializes people into submission to hurting their own children.” Moreover, Abd el Salam maintains, it is a particularly effective means of doing so because of the special value of boys in patriarchal systems.

For such patriarchal systems to persist, the role of MGC in normalizing such top-down violence—that is, painful genital cutting inflicted on the most valuable members of society when they are simultaneously at their most vulnerable—must not be questioned. It is, according to one theory of the socio-functional origins of the practice, a dangerous and costly signaling device that proves one's willingness to submit to the norms (and rankings or authority structure) of the wider community, which would have been necessary for group survival under certain challenging conditions (Schlegel and Barry, 2017). FGC also serves this purpose, but to a lesser extent: “getting people to tolerate mutilation of their sons' bodies as a price for conditioned social acceptance is a stronger tool to ensure their submission to authorities than getting them to tolerate [FGC]” (Abd el Salam, 1999).

According to Abd el Salam, there is at least an implicit recognition of this fact among “pragmatic” defenders of the right to bodily integrity: that is, those campaigners who, like the WHO, selectively apply the principle and oppose only FGC. Such campaigners seem to know, at least on some level, that raising MGC as an issue “may break the terms of their unwritten political bargain” with the conservative patriarchal forces. This, in turn, “explains the panic of pragmatists from raising the issue [and their] attack of anyone who dares to raise it.”26 According to this way of thinking, it is better to allow men to continue to dominate boys within the logic of the patriarchal power system—for example, by testing them with painful rites until they prove they are capable of assuming a dominant position themselves—than to disturb the status quo while seeking an allowance to end FGC of girls.

The strategy may seem sensible, but Abd el Salam proposes that it cannot work in the long run, if the aim is to undermine the patriarchal system. She writes: “the pragmatists are right in that … hegemonic social authorities at all levels are likely to stand against any efforts to liberate people from the suffering of hurting their own sons. Nonetheless, they are not right in neglecting the potential impact of such efforts on bringing about a social change for the benefit of the more vulnerable social groups,” including women and girls and sexual and gender minorities. MGC, she suggests, serves as a lynchpin of patriarchy in those various human societies that have, at some point in their history, discovered its usefulness for that very purpose. To undermine the patriarchal order of gender relations, the lynchpin must be pulled.

This analysis by Abd el Salam appears to be borne out by the recent global phylogenetic study conducted by Šaffa and colleagues, mentioned earlier. Not only did they find that FGC has almost always come about, historically, in societies already practicing MGC; they also found that the abandonment of MGC in certain societies has reliably been followed by a “rapid loss” of FGC as well (Šaffa et al., 2022). Given, therefore, the apparently greater socio-structural dependence of FGC on MGC than vice versa, Šaffa and colleagues suggest that “it may be more difficult to eliminate [FGC] while treating male circumcision as a separate issue.” Instead, “efforts to eradicate [genital cutting] may benefit from greater gender neutrality” in dominant approaches to social reform.

If this line of analysis is correct, it might be necessary for the long-term achievement of gender equality in societies that practice FGC—and thus also MGC—for international advocates of children's rights to bodily integrity to join forces across lines of sex and gender. This should involve collaboration with local dissenters and reformers to condemn and campaign against, not only FGC, but also MGC and IGC: that is, all medically unnecessary genital cutting of vulnerable children by adults in positions of power. All such practices can be seen as normalizing the infliction of bodily injuries on relatively defenseless persons and thus as a form of violent domination, thereby reinforcing the patriarchal status quo. By contrast, a human rights approach, consistently applied, may break the cycle of violence once and for all.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Thank you to Clare Chambers, Manon Garcia, Ellen Gruenbaum, Sara Johnsdotter, Saarrah Ray, Arianne Shahvisi, and the peer reviewers for valuable feedback on earlier drafts. Thank you also to Enrico Ripamonti for his extraordinary patience with the revisions.