- 1Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 2Program Participation, Talent Development and Equality of Opportunity, The Netherlands Institute for Social Research, The Hague, Netherlands

- 3Program Representation and Trust, The Netherlands Institute for Social Research, The Hague, Netherlands

Various studies have indicated the disadvantaged positions of refugees on the labor market and studied various characteristics explaining this. Yet, little is known about the impact of settlement policy characteristics on recent arrivals' labor market participation, despite them being heavily subject to such policies. We argue such policies, next to individual characteristics, can serve as a means to gather resources relevant to the host country and consequently labor market positions, but can also serve as a post-migration stressor obstructing this. Using the Netherlands as an example, we contribute to studies on the refugee gap and provide insight into key policy characteristics explaining recently arrived refugees' (finding) employment. We use two-wave panel data of 2,379 recently arrived Syrian refugees in the Netherlands, including data on key policy and individual characteristics combined with administrative data. Employing a hybrid model, we show both within- and between-person variation. Results indicate policy matters: short and active stays in reception, complying with the civic integration obligation and a lower unemployment rate in the region refugees are randomly assigned to are beneficial for Syrians' (finding) employment. Like for other migrants, various forms of individual human capital also play a role.

Introduction

Immigrants, and especially refugees, are often found to hold economically disadvantaged positions, also known as the refugee gap (see among others: Waxman, 2001; Connor, 2010; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Correa-Velez et al., 2013; Bakker et al., 2017; Kanas and Steinmetz, 2021). Yet, newcomers' finding employment is important for both receiving societies and newcomers themselves regarding newcomers' self-reliance (Koenig et al., 2016; van Liempt and Staring, 2020) general and settlement outcomes in other domains such as language and social contacts (Carrington et al., 2007; Colic-Peisker and Tilbury, 2007; Ager and Strang, 2008).

(Re)gaining lost resources and acquiring new skills relevant to the host society has been found crucial in securing employment (Hobfoll, 2001; Ryan et al., 2008). As shown in previous studies, newcomers' labor market positions can be explained through a wide range of such resources (for an overview, see Heath and Cheung, 2007; Ott, 2013), including pre- and post-migration cultural capital (Waxman, 2001; Chiswick and Miller, 2009; Hartog and Zorlu, 2009; Kanas and van Tubergen, 2009; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Correa-Velez et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2019), social capital (Waxman, 2001; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Kanas et al., 2011; Correa-Velez et al., 2013; Cheung and Phillimore, 2014) and personal capital (Phillimore, 2011; Walther et al., 2019).

In this paper, we aim to contribute to the understanding of (the lack of) refugees' labor market participation by addressing the question: What are key policy characteristics explaining recently arrived refugees' finding employment? We do so because we argue that, even though the impact of individual characteristics has been thoroughly studied, the field of studies on the impact of settlement policy characteristics (which we understand to be procedures installed and influenced by the government) for recent arrivals is lean. Yet, unlike other migrants, refugees, and especially those who have recently arrived, are highly subject to such policies in most European countries. Such settlement policy characteristics could hamper or promote refugees' resource gathering and consequently their labor market participation (Kogan, 2007; Kanas and Steinmetz, 2021; Kosyakova and Kogan, 2022).

There are studies that included one or a few of such policy factors in explaining (recently arrives) refugees' labor market participation (see Kosyakova and Kogan, 2022, for an overview). At first, it was shown that awaiting a decision on the permit to stay in reception centers can hinder resource gathering in general (Phillimore, 2011; Weeda et al., 2018; Damen et al., 2021) and employment in particular (de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Bakker et al., 2014; Hainmueller et al., 2016; Hvidtfeldt et al., 2018; Kosyakova and Brenzel, 2020). In some countries moreover, refugees are expected to pass a civic integration exam, (designed to) help them gain resources relevant to the host society and its labor market (Clausen et al., 2009; Blom et al., 2018; Battisti et al., 2019; Lochmann et al., 2019; Boot et al., 2020; CPB and SCP, 2020; Fossati and Liechti, 2020). Furthermore, refugees are generally randomly distributed across receiving societies, which can promote or hamper their labor market positions due to the (limited) opportunities available for resource gathering or employment (Åslund et al., 2000; Åslund and Rooth, 2007; Bevelander and Lundh, 2007; Larsen, 2011; Gerritsen et al., 2018; Aksoy et al., 2020; Fasani et al., 2022; Kanas and Kosyakova, 2022).

While the impact of various forms of individual human capital on newcomers' labor market positions has thus been studied thoroughly, and some studies include one or two policy characteristics, only a limited number of studies included a variety of such characteristics in trying to explain their impact on (changes in) recently arrived refugees' labor market integration (Waxman, 2001; Colic-Peisker and Tilbury, 2007; Kanas and Steinmetz, 2021). Waxman (2001) and Colic-Peisker and Tilbury (2007) showed differences in employment with regards to discrimination and non-recognition of certificates among recent arrivals (Colic-Peisker and Tilbury, 2007), as well as language but not duration of reception or qualifications (Waxman, 2001). However, both studies are largely descriptive, thereby lacking to statistically investigate the impact of the variety of policy characteristics. In addition, these studies predominantly use cross-sectional data and therefore cannot provide insight into the dynamics of refugees' employment. Kanas and Steinmetz (2021) do employ multiple waves and explain the role of labor market (but not settlement) policies.

Using the Netherlands as an example, our study provides insight into labor market positions within a cohort of 2,379 recently arrived Syrian refugees in the Netherlands. Adding to previous studies, we emphasize the impact of a wide variety of settlement policy characteristics (reception, civic integration, and regional unemployment rates), utilizing the opportunity to understand which of such characteristics are beneficial for recently arrived refugees' economic incorporation (Kosyakova and Kogan, 2022). Second, we examine employment among recent arrivals by employing two waves of survey data from refugees in the Netherlands who received a residence permit between 2014 and 2016 (consistent with the peak of the refugee influx in Europe). This provides us with the opportunity to identify key characteristics explaining recently arrived refugees' labor market participation. Third, we use two-wave panel data which allows us to better distinguish the dynamics in newcomers' finding employment. Given the long-term and dynamic nature of refugee settlement and the economic experience of refugees, longitudinal research is valuable to get a better grip on which characteristics are key in determining refugees' initial labor market positions (Beiser, 2006; McMichael et al., 2015).

Theoretical considerations

(Re)gaining resources and labor market positions

Integration starts upon arrival, which implies early experiences can influence long-term outcomes (Ghorashi, 2005; DiPrete and Eirich, 2006; Bakker et al., 2017). Moreover, during the initial period after arrival, newcomers tend to experience most changes (Diehl et al., 2016; Geurts and Lubbers, 2017), having to deal with lost resources (Hobfoll, 2001) and uncertainties and finding their way in the host society. To integrate, in this case into the labor market, refugees need to (re)gain lost resources and acquire new skills relevant to the host society (Hobfoll, 2001; Ryan et al., 2008)—“the presence or absence of which can shape their future opportunities and trajectories” (Phillimore et al., 2018, p. 5).

Previous research has indicated a refugee gap, showing the disadvantaged labor market positions of refugees, studying a variety of characteristics explaining this gap. For example, Waxman (2001) showcased the impact of language competency among refugees in Australia. de Vroome and van Tubergen (2010) displayed similar results regarding language and furthermore indicated the impact of host country specific education and work experience, as well as contacts with natives among refugees in the Netherlands. Also studying refugees in the Netherlands, Bakker et al. (2017) show the impact of migration motive, country of origin, length of stay, age, household characteristics, density of the region, having a Dutch qualification and Dutch nationality. Showcasing somewhat similar results among refugees' in Australia, Correa-Velez et al. (2013) showed the impact of region of birth, length of stay, using job service providers and informal networks, and owning a car were significant predictors of refugees' employment in Australia. They did however not find an impact of English language proficiency. Also in Australia, Cheng et al. (2019) indicated the impact of pre-immigration paid job experience, completed study/job training, having job searching knowledge/skills in Australia, possessing higher proficiency in spoken English and mental health. Touching upon the role of (labor market) policies, Kanas and Steinmetz (2021) establish the significant role of such policies in the economic disadvantage of family migrants and refugees.

Building on this, we include explanatory characteristics based on two out of the three overarching clusters as distinguished by Huddleston et al. (2013); policy and individual characteristics.1 Using Hobfoll's (2001) theory on resources, we explain how these policy and individual characteristics benefit or hamper refugees' finding employment. Hobfoll (2001) defines resources as entities “valued in their own right or valued because they act as conduits to the achievement or protection of valued resources” (p. 339). While both hold for individual characteristics, policy characteristics can be regarded as more of a means to gather such resources but can also serve as a post-migration stressor obstructing this (see also: Bakker et al., 2014).

Since the impact of various forms of individual characteristics (such as pre-migration, post-migration, social and personal capital) on refugees' labor market positions has been studied thoroughly, we emphasize the impact of policy characteristics in this study. Thereby we focus on the period in reception, civic integration, and dispersal policy. Based on theory and previous research, we form hypotheses about the impact of these policy characteristics on recently arrived Syrian refugees in the Netherlands finding employment in the next section. To match the extensive range of studies in this field and to provide the most complete analysis possible, we also include an extensive selection of individual characteristics (which can be regarded as a type of control variable), but given the focus here is on policy, and the impact of these individual characteristics is already more established, we do not formulate separate hypotheses about on these.

The opposing impact of characteristics of the reception period

Starting upon arrival, asylum seekers (in the Netherlands and many other European countries) are provided accommodation in reception centers until their application is granted and housing is available. When they are awaiting the decision on their permit, their right to work is very much restricted. Employers need to apply for an employment permit, which most employers are not as keen to do, and moreover one can only work 24 out of the 52 weeks and needs to give up part of their salary to the reception center. These restrictions make it quite unlikely for newcomers to engage in employment when awaiting the decision on their permit but only do so after they move out of reception. In the rare case that one is already employed during their reception stay, this does not determine when they can move out of reception. Reception centers have been heavily criticized, especially regarding mental health. The main argument being that the isolated life in the reception center can cause refugees to waste vital years (Ghorashi, 2005; Smets et al., 2017). Based on this, it could be expected that a stay in reception centers can constrain refugees' ability to (re)gain the necessary resources (Bakker et al., 2014). We understand refugees having to stay in reception until their permit is granted and housing is available as a form of policy in itself, i.e., reception policy. Within this policy, it is for example determined how long the procedure regarding the decision on newcomers' residence permit may take (and thus how long they might have to stay in reception centers). Such a reception stay thus has various policy characteristics to it, such as the length of stay, but also the number of centers one stays in and opportunity to participate in activities, which we argue can all impact newcomers' employment.

Concerning labor market participation specifically, lengthy asylum procedures can be regarded as a post-migration stressor obstructing labor market opportunities. Longer stays can result in devaluation of human capital (Phelps, 1972; Smyth and Kum, 2010). Moreover, longer exposure to insecurity during reception stays as well as to non-employment may depress working aspirations (Hainmueller et al., 2016). Also, this feeling of insecurity or boredom might result in worsened mental health (Laban et al., 2004), which can consequently obstruct (labor market) integration (Phillimore, 2011; Weeda et al., 2018; Ambrosetti et al., 2021; Damen et al., 2021). Longer isolation from social resources, such as a social network that might assist with informal (labor market) information or opportunities, may furthermore delay refugees' job search and job-finding process (Bakker et al., 2014). Longer isolation can also mean being less exposed to the host country's language, which has been proven most important to learn (Kosyakova et al., 2022). Longer stays can thus negatively affect refugees' labor market participation for various reasons (de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Bakker et al., 2014; Hainmueller et al., 2016; Hvidtfeldt et al., 2018; Kosyakova and Brenzel, 2020).

Moreover, characteristics of the reception period may affect labor market participation in addition to the impact of duration. For example, through the number of relocations, that has been shown to negatively affect how newcomers find their way in the new society (Nielsen et al., 2008; Damen et al., 2021). The mechanism underlying this is that such relocations take place without the involvement of the refugees themselves and can be disruptive (Vitus, 2011). This lack of control and disruptiveness might in turn hamper mental health and consequently refugees' integration (Phillimore, 2011; Weeda et al., 2018; Ambrosetti et al., 2021; Damen et al., 2021). Moreover, if one has to relocate often this could be an obstacle to engaging in activities to (re)gain resources. Thus, relocations can also serve as a post-migration stressor obstructing refugees' finding employment.

Regarding gathering resources, the possibility to engage in activities during the reception center could in turn have a positive impact. While there are restrictions when it comes to employment when awaiting the decision on one's residence permit, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment and the Central Organization for the Reception of Asylum Seekers (COA) committed to providing opportunities for various activities in reception centers in 2016 (Bakker et al., 2018). Since then, reception centers may offer a variety of activities for their residents as part of reception policy, such as Dutch language learning or volunteering. Engaging in such activities can result in the feeling of regaining control over one's life, help to (re)gather resources, give distraction, a goal, and increase confidence (Bakker et al., 2018), all possibly leading to more prosperous integration (Weeda et al., 2018; Damen et al., 2021).

Based on previous findings regarding characteristics of the reception period, we arrive at three hypotheses about their impact on Syrians' employment: a longer stay (H1a), a higher number of relocations (H1b), and little participation in activities in reception centers (H1c) will negatively affect recent arrivals' employment.

Civic integration and employment

The second policy characteristic theoretically important for refugees' employment is civic integration. Apart from the need to integrate in general, civic integration in this case means the obliged integration period during which newcomers have to take courses (language, knowledge of the receiving society culture, and labor market) which can most often be finished through exams, after which they are considered “integrated” if they pass. In many European receiving countries such civic integration is obliged through civic integration policies on the macro-level. The micro-level impact here is that through such obliged civic integration the labor market position of refugees can be improved by assisting them to gather vital resources through the various courses and exams. Various studies have indicated the positive impact of such courses on newcomers' labor market participation (Clausen et al., 2009; Battisti et al., 2019; Lochmann et al., 2019; Fossati and Liechti, 2020; Kanas and Kosyakova, 2022).

In the Netherlands, the civic integration program is completed with an exam.2 which concerns language training and societal orientation. We can expect passing the integration course to be beneficial for refugees' employment because it represents practice with the Dutch language and a source of information on how things work in the Netherlands (Blom et al., 2018; Boot et al., 2020; CPB and SCP, 2020). Like in other countries, various studies in the Netherlands showed that passing the integration exam was indeed positively associated with the chance of employment (or not having obtained negatively associated) (de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Odé et al., 2013; CPB and SCP, 2020). As such, we propose successful completion of the integration course will positively affect the employment of recent arrivals in the Netherlands (H2).

Dispersal policies and the impact of regional unemployment rates

The place where newcomers end up is important, for example, due to local labor market conditions, opportunities for establishing social contacts, and local facilities. Several European countries have adopted the policy of geographic dispersal when it comes to newcomer's resettlement (Denmark, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the UK) (Fasani et al., 2022). In the Netherlands, this means refugees (with a temporary residence permit) are equally distributed among the municipalities in proportion to the number of inhabitants. Such a distribution can be seen as fair from the point of view of the municipalities, as they all host an equal share. For refugees, however, this can lead to unequal opportunities. Facilities to support newcomers, as well as opportunities for networking and finding employment, can simply be better in one municipality than in another and unlike most other Dutch people, refugees cannot decide where to live and are thus bound to its local (labor market) conditions.

The dispersal policy is thus another policy installed by the government which can impact newcomers' labor market participation. While there are many consequences of such a policy, the regional unemployment rate can be expected to be one of the most relevant regarding our outcome measure. By including this measure, we include the opportunity structure provided by low/high unemployment rates, and the dispersal policy explains why some newcomers are subjected to lower and others to higher unemployment rates, depending on the region they are assigned to and the regional labor market opportunities (Edin et al., 2003; Fasani et al., 2022).

Previous research from countries with such dispersal policies indeed points to its disadvantages (Åslund et al., 2000; Åslund and Rooth, 2007; Bevelander and Lundh, 2007; Larsen, 2011; Gerritsen et al., 2018; Aksoy et al., 2020; Fasani et al., 2022; Kanas and Kosyakova, 2022). Limited geographic mobility reduces the chances of finding employment or good job matches, and in some countries, refugees are allocated to relatively disadvantaged areas, where accommodation is cheaper but labor demand is weaker (Fasani et al., 2022) or there are limited opportunities for language learning (Kanas and Kosyakova, 2022). Despite being equally distributed across municipalities in the Netherlands, chances for employment can differ per region, partly due to regional (labor market) conditions (Gerritsen et al., 2018). As we cannot include a direct measure of dispersal policies as such, we include the regional unemployment rate as one (of many) characteristics of dispersal policy, which can indicate differences in (finding) employment among refugees assigned to different regions. We expect: lower regional unemployment to contribute positively to the employment of recent arrivals in the Netherlands (H3).

Individual capital and employment

Originating from human capital theory (Nafukho et al., 2004), various forms of individual capital are most popular in explaining differences in labor market positions. Because capital is relational, a distinction is made between pre-and post-migration human capital (Friedberg, 2000; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Cheng et al., 2019). Regarding pre-migration capital, home country education and work experience can be important for economic success (Connor, 2010; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010). Yet, transferring these skills can be difficult, especially for refugees, as pre-migration certificates and work experience are often not recognized or valued by employers (Friedberg, 2000; Colic-Peisker and Tilbury, 2007; Chiswick and Miller, 2009; Kanas and van Tubergen, 2009; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010). In this regard, it might either be that those with high-skilled work experience find work easier due to their (cognitive) skills, but on the other hand it might be easier to secure employment for those with low-skilled or no work experience due to the availability of such jobs in the destination country. Regarding post-migration human capital, education acquired in host countries is considered important in enhancing employability directly or indirectly (Hartog and Zorlu, 2009; Kanas and van Tubergen, 2009; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010). Other forms of post-migration human capital associated with labor market success are host country language (Waxman, 2001; Kanas and van Tubergen, 2009; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Koopmans, 2016; Cheng et al., 2019) and voluntary work experience (Bakker et al., 2018; Cheng et al., 2019). Bourdieu (1986) classified these types of knowledge, skills and qualifications as cultural capital but also indicated social capital as fundamental resource. Such social capital has also been found to be associated with newcomers' labor market success (see among others: de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Kanas et al., 2011; Correa-Velez et al., 2013; Cheung and Phillimore, 2014). Co-ethnic networks can provide emotional and material support but also knowledge and information which can facilitate adjustment to the labor market (Kanas et al., 2011; Correa-Velez et al., 2013). At the same time, co-ethnics might be involved in a certain niche in the labor market, which might not match the newcomers' skills or (higher) ambitions. In this regard, social contacts with natives are found to be particularly important (Kanas and van Tubergen, 2009; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Kanas et al., 2011; Koopmans, 2016), as they can provide access to wider society and facilitate cultural adaptation with wider job choices as a result. Another individual characteristic regarded as personal capital is health (mental and physical). Health problems are relatively high among refugee populations (Beiser, 2006) and poor health can serve as a barrier to successful settlement (Ager and Strang, 2008; Phillimore, 2011; Walther et al., 2019; Ambrosetti et al., 2021). Considering labor market positions specifically, depression and general health problems have been found to negatively relate to different labor market outcomes among refugees (Connor, 2010; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Bakker et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2019). Although not our focus, we include these various individual human capital characteristics to substantiate earlier findings and properly estimate the impact of the policy characteristics.

Materials and methods

The analysis was based on two waves of the survey “New Permitholders in the Netherlands” (NSN2017 and NSN2019),3 which were conducted as part of a larger project (Longitudinal cohort study permit holders) at the request of four Dutch ministries, aiming to gain insight into early integration among refugees in the Netherlands. The first wave of the NSN was collected in 20174 among Syrians aged 15 and older who received a (temporary) residence permit between January 1st, 2014, and July 1st, 2016. Their children born in the Netherlands and family members who reunited in 2014/2015 also belong to the target population. Based on these characteristics (ethnic background, age, legal status, child, or family member) a single random cluster sample was drawn from the target population by Statistics Netherlands. The questionnaire was tested thoroughly and translated into Modern Standard Arabic. A sequential mixed-mode survey design was used; respondents were first invited to complete the survey online (CAWI) but if they did not, they were given the opportunity to complete the survey in person with an interviewer (CAPI). In case of no response, interviewers would visit respondents up to four times to make an appointment.5 All interviewers spoke Arabic and were from the same country of origin as the respondents. The second wave of the survey was collected in 2019 and a similar approach was taken regarding the data collection. Some questions were only asked in wave one (for example those on the reception period), which is why we copied the 2017 values to 2019 to keep these characteristics constant.

In total, 3,209 Syrians completed the first survey, corresponding to a response rate of 81%. Statistics Netherlands was able to provide data for 2,944 people in 2019 and 2,544 participated in the second survey, resulting in a response rate of 86%. The high response rates can partly be attributed to the personal and repetitive approach, but it also shows people were eager to provide their input. The survey files were weighted by Statistics Netherlands to match the distribution in the sample with that in the population. Moreover, the survey data was enriched with administrative data from Statistics Netherlands.6 For this study, we made use of a balanced panel, meaning only respondents who participated in both waves were included (N = 2,544). Moreover, we selected those who were in the 15–74 age group, given that these are the official age limits for the working population in the Netherlands, and did not have any missing values on the variables in our models. Consequently, the final sample consisted of 2,379 respondents.

Measures

To access Syrians' labor market positions, we focus on net-participation, i.e., employment, which was dichotomized into those who were employed (1) versus those who were not employed (0).7 Those employed included self-employed, employed full-time, or employed part-time and those not employed included those unemployed as well as those not in the labor force, e.g., actively seeking employment.

To explain labor market participation, we include different settlement policy measures. The first being characteristics of the reception period measured through length of reception stay (in years), the number of reception centers one has stayed in (0–9) and engaging in one or more activities (such as language learning, volunteering of work) during the reception period (1 = yes, 0 = no), which refer to a point in time before the first survey. Moreover, passing the civic integration course was included as a dummy variable (1 = passed or exempt from, 0 = not completed). Regional labor market conditions were included through the regional unemployment rate. The regional unemployment rate (in the first quarter of 2017 and 2019, the years of the corresponding survey) was included as a continuous variable (0–100). The COROP classification–a regional area classification used for analytical purposes within the Netherlands, also known as NUTS 3 (Verkade and Vermeulen, 2005)–has been used for this. This classification entails a total of 40 COROP areas in the Netherlands. Two provinces (Flevoland and Utrecht) are each one COROP area, the others are part of one (out of twelve) province and consist of several municipalities.

Additionally, we took several individual characteristics into account. Pre-migration education was included as a dummy variable (1 = followed or completed higher education, 0 = followed or completed lower education or no education). Pre-migration work experience was included as a categorical variable (0 = no work, 1 = unknown skilled work, 2 = lower skilled work and 3 = higher skilled work). Post-migration education covered all those in vocational training to university and was included as a categorical variable (0 = no education/no certificate (ref), 1 = education but certificate unknown, 2 = certificate obtained). Dutch language proficiency was included as a self-reported score (1–10), for which a higher score represents stronger proficiency. Volunteering experience was included as a categorical variable indicating the frequency [0 = never (ref), 1 = yearly/monthly, 2 = weekly/daily]. Social contact with other Syrians and social contact with Dutch nationals were both included as dummy variables (1 = weekly or more frequent, 0 = monthly or less frequent). Finally, we included mental health (0–100, the higher the better the mental health8) and having one or more long-term (physical) disorders (1 = yes, 0 = no). Gender (1 = female, 0 = male), age in 2017 [in categories: 1 = 18-24 years (ref), 2 = 25-34 years, 3 = 35-44 years, 4 = 45 years and older], year of arrival (in categories: 1 = 2010–2014 (ref), 2 = 2015, 3 = 2016), having child(ren) living at home, regardless of their age (1 = yes, 0 = no), being a family migrant (1 = yes, 0 = no) and views on gender roles (scale of 1–5 based on four items, the higher the more progressive) were also included.

Method

To make optimal use of the panel character of the data and to test the hypotheses, we estimated a hybrid model (Allison, 2009) in Stata (version 16). A hybrid model is a random effects (RE) model with decomposed estimates, i.e., fixed effects (FE) and between effects (BE), all well known for analyzing panel data. Although FE brings us closest to displaying the impact of changes over time, non-time-varying characteristics (such as characteristics of the reception period or pre-migration education) are omitted from such a model. As we are interested in displaying the impact of a wide variety of characteristics on Syrians' finding employment in this study, we opted to employ a hybrid model. Within a hybrid model, both the effects of time-varying (such as passing the integration course and regional labor market conditions) and non-time-varying characteristics can be estimated simultaneously (Schunck and Perales, 2017). The hybrid model estimates within-person (FE) and between-person effects for the time-varying characteristics and between-person effects (BE) for the non-time-varying characteristics (Brüderl and Ludwig, 2019). The within-person effects reflect the effect of change in the independent variable on change in the dependent variable over time and between effects represent differences between persons in the outcome measure. As our main interest here is to explain dynamics in employment and estimates of the between-effects “are (in most cases) substantively of no interest” (Brüderl and Ludwig, 2019, p. 208), we opted to only display and discuss FE for the time-varying and BE for the non-time-varying characteristics. Models were estimated with the specification of a robust standard error (Schunck and Perales, 2017).

Results

Descriptive statistics

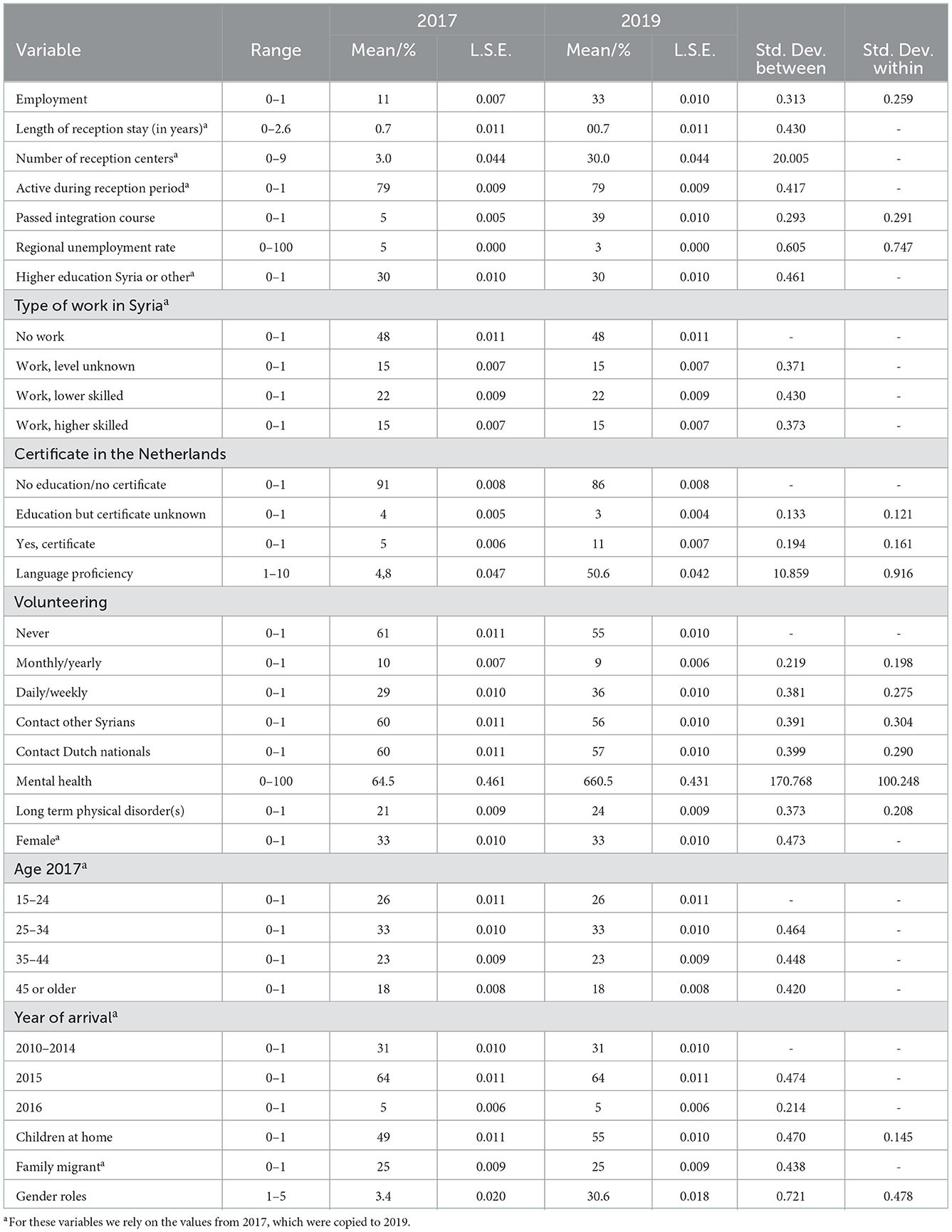

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables in the analyses, displaying the group differences in means for 2017 and 2019 as well as the between and within variation per variable. Focusing on the mean differences of the key variables in our study (employment and policy characteristics) the table shows that in 2017, 11% of Syrian refugees were employed, which increased to 33% in 2019. Refugees in this study on average spent 7 months in reception and stayed in three different centers. A large share of the respondents (79%) indicated they participated in at least one activity during their time in the reception center(s). They can thus be considered to have spent their time in reception actively. Those who have complied with the civic integration requirement (passed or exempt from) increased sharply, only 5% were successful in 2017, compared to 39% in 2019. The regional unemployment rate has decreased slightly from 5% in 2017 to 3% in 2019. Considering the variance between municipalities, the regional unemployment rate ranged from 3.6 to 6.3 percent in 2017 and 2.7 to 4.7 percent in 2019.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the variables in the analysis. Syrian refugees, 15–74 years, 2017–2019 (n = 2,379; in means and percentages), weighted averages.

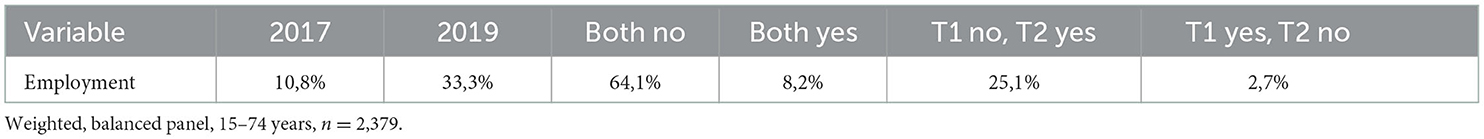

Looking at the individual changes in employment, Table 2 shows there has been a relatively large share of positive change; 25.1% made a positive change between t1 and t2. This means that over the course of 2 years, about a quarter of those not employed in 2017 did indicate to be employed in 2019. Only 2.7% of the Syrians in this study changed from being employed to not being employed between 2017 and 2019. Generally, we can see a positive trend: during their first years after settlement Syrian refugees' employment has developed positively, more refugees are employed over time.

Explaining (changes in) Syrian's employment

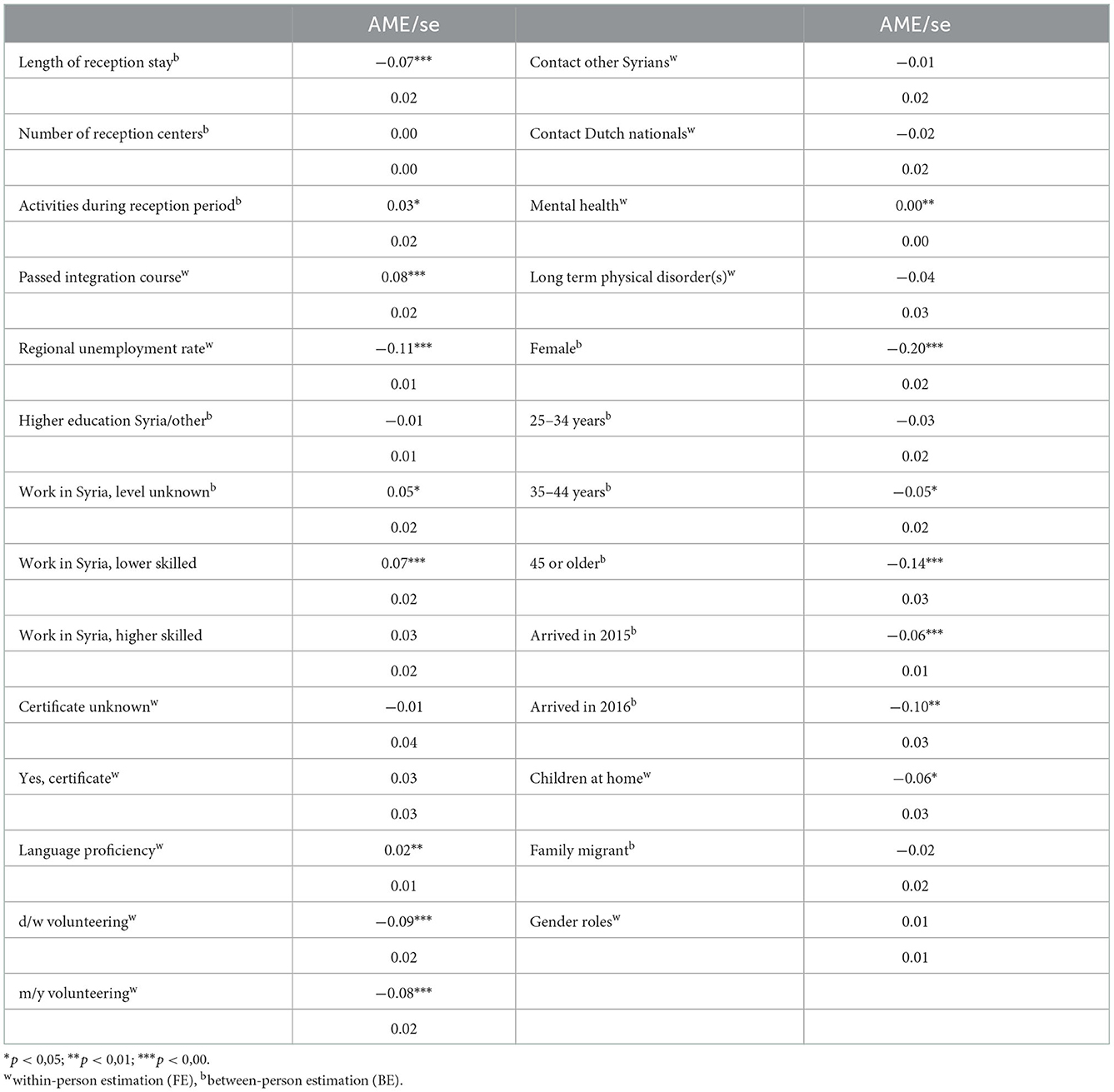

Next, we are interested to identify important characteristics associated with positive changes in Syrians' employment. Before testing the hybrid model, we checked for multicollinearity. VIF scores ranged from 1.02 for certificate unknown to 3.61 for age over 44, indicating there was no multicollinearity problem. The results from the hybrid model–both FE for time-varying characteristics and BE for non-time-varying characteristics–are presented in Table 3. The results are unweighted, and we show results of the full model, including all explanatory characteristics. However, we have built the model in steps to provide insight into direct and indirect effects. For this step-by-step structure, see Appendix B. We discuss the results per explanatory characteristic, focusing on the impact of settlement policy characteristics. The results are presented in average marginal effects and can be interpreted as follows: below zero means a decrease in the chance of (finding) employment, above zero means an increase in the chance of (finding) employment. Goodness of fit of the proposed model was: χ2(40, N = 2,379) = 355.95, p < 0.0001.

Policy matters

The results show that procedures installed and influenced by the government can impact newcomers' labor market participation. As our results indicated, the impact of such policies already starts during the initial period after arrival, when newcomers are staying in reception centers and are subject to reception policies. Part of what happens during their reception stay is related to whether recent arrivals find a job afterward. If one has stayed in reception centers longer, their chance for employment decreases (H1a confirmed). Those who had to stay in reception longer for various reasons, i.e., decision on their permit delayed, no housing available, can thus experience additional disadvantages when it comes to their labor market success. On the contrary, for refugees who have been active during the reception period the chance to be employed increases, compared to refugees who did not participate in such activities (H1c confirmed). Spending the reception period shortly and actively can thus be understood to be beneficial regarding refugees' labor market participation. The results do not indicate a relationship between the number of reception centers and Syrians' employment (H1b rejected).

As intended on the macro-level, passing the integration course has a positive impact on Syrian refugees finding employment. For refugees who complied with the civic integration obligation, the chance to find employment increases (H2 confirmed). In addition, the place where refugees live proves to be important; a rising unemployment rate (regional change or through change of residence) decreases the chance for finding employment (H3 confirmed). In this regard, the dispersal policy, next to many other consequences that can be attributed to this, does explain why some newcomers are subjected to lower and others to higher unemployment rates, depending on the region they are assigned to and thereby signals and the possible uneven consequences of varying unemployment rates through random allocation.

Impact of individual capital

Although we are particularly interested in the impact of settlement policy characteristics, findings on the individual characteristics are also relevant. Results show an impact of pre-migration work experience; for those who had work in Syria of which the status was unknown, or it was a lower skilled job, the chance to be employed in the Netherlands increases. An improvement in Dutch language proficiency also has a positive impact, the chance of finding employment increases for those whose Dutch language proficiency has improved. Better mental health also leads to an increased chance of finding employment. The difference may seem modest, (0.00), but the scale runs from 0 to 100. This may have a greater impact once mental health deteriorates. Volunteering on the other hand seems to hinder finding employment. Social contacts with other Syrians or Dutch nationals, the level of education from Syria or other foreign countries, obtaining a certificate and physical health, perhaps strikingly, do not show a significant relationship with Syrians' employment. For Syrian women, the chance for employment is much lower than for Syrian men. Moreover, the chance for employment is lower for Syrians over the age of 35, for Syrians with children living at home, and for Syrians who came to the Netherlands later.

Additional analyses

There are some time-varying characteristics, such as obtaining a certificate in the Netherlands, social contacts, and physical health, for which we did not determine a significant within-person effect. To check whether these do indeed not play a role at all, we tested an additional random-effects model (Appendix C). We decided to do so because the FE approach is a 'strict' way of establishing relationships as it is dependent on the time points at which the respondents were studied. In this study, this means the FE approach only takes into account changes occurring between wave 1 and wave 2. Thereby respondents who have not changed on the dependent variable between the observed time points are excluded and anyone who already had a physical disorder when s/he/they arrived in the Netherlands, and therefore cannot work, is excluded. Few respondents changed in obtaining a certificate, social contacts, or their physical health between the two observed time points, which makes it difficult to estimate these relationships properly. We might be too quick to conclude—based on the available data—that these characteristics do not matter for Syrians' employment if we only look at the within-person (FE) estimations. What we see—based on the additional RE models—is that people with a physical disorder are less often employed than people without a physical disorder. Also, these models show that Syrians who obtained a certificate in the Netherlands are more likely to be employed than Syrians who did not. These characteristics thus do play a role in determining Syrians' employment. We do not find significant relations for social contacts.

We additionally tested the full model for a restricted part of the sample; only those between 25 and 55 years of age. We did so since when it comes to employment, especially newcomers within this age range would be expected to engage in the workforce as their main activity. As Appendix D shows, results are largely robust. Similar explanations for (finding) employment hold whether we include the complete sample, or those restricted between 25 and 55 years. In the latter model we do find an additional significant effect for those with a long-term physical disorder, showing that for those who came to suffer from this their chance for employment decreases. There was no longer a significant result for those between 35 and 44 years of age, as compared to those between 25 and 34 their chances for employment do not differ, in contrast to compared to those between 15 and 24.

Discussion

Previous research has indicated a refugee gap, showing the disadvantaged labor market positions of refugees (see among others: Waxman, 2001; Colic-Peisker and Tilbury, 2007; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Correa-Velez et al., 2013; Bakker et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2019; Kanas and Steinmetz, 2021). To integrate into the labor market, refugees need to (re)gain lost resources and acquire new skills relevant to the host society (Hobfoll, 2001; Ryan et al., 2008). Building on and further extending the impact of previously studied characteristics, we focused on the initial economic adjustment of recently arrived Syrian refugees in the Netherlands and contributed to the existing literature in three ways: (1) we explored the impact of a wide range of characteristics, focussing on the impact of settlement policy characteristics, (2) we examined employment among recent arrivals identifying key characteristics for refugees' initial labor market participation, (3) we employed panel data to better distinguish dynamics in Syrians' (finding) employment.

Results show a positive trend regarding the employment of recently arrived Syrian refugees in the Netherlands; their employment has increased between 2017 and 2019. Focusing on two of the three overarching clusters of explanatory characteristics (Huddleston et al., 2013), we showed which policy and individual characteristics explain these changes, partly through (re)gaining resources (Hobfoll, 2001). All in all, our findings indicate policy matters (see also: Kosyakova and Kogan, 2022). We find that a longer stay in reception centers reduces the chance of being employed (see also: de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Bakker et al., 2014; Hainmueller et al., 2016; Hvidtfeldt et al., 2018; Kosyakova and Brenzel, 2020). The duration of the reception period can thus be regarded as a post-migration stressor which hampers (re)gaining resources and as a result Syrians' employment. For example, due to devaluation of human capital (Phelps, 1972; Smyth and Kum, 2010), declining work aspirations (Hainmueller et al., 2016), increased health risks (Phillimore, 2011; Weeda et al., 2018; Damen et al., 2021), and longer isolation from social resources (Bakker et al., 2014). Interestingly, the impact of the reception period is not as negative as portrayed before, as engaging in activities (such as language learning and volunteering) during the reception period has a positive impact on being employed. Spending the reception period actively can help to (re)gather resources, give distraction, a goal and increase confidence (Bakker et al., 2018), resulting in better chances to secure employment. In this regard, reception policy can be regarded as a first form of integration policy, because preparation for integration already starts during reception. The results did not indicate a relationship between the number of reception centers and Syrians' employment. This could be due to the way we included this variable (continuous as opposed to categorical). There might be an impact solely for those having stayed in over a number of different centers, which can be investigated in future studies.

Moreover, results show refugees who have complied with the civic integration obligation (passing their language and cultural knowledge exams) have a higher chance of finding employment (see also: Clausen et al., 2009; de Vroome and van Tubergen, 2010; Odé et al., 2013; Battisti et al., 2019; Lochmann et al., 2019; Fossati and Liechti, 2020; Kanas and Kosyakova, 2022). This finding can be understood in two ways. On the one hand, compliance with the integration requirement is a form of gaining resources relevant to the host society, such as a certain level of Dutch language and knowledge about Dutch society, culture, and the labor market. These resources can subsequently be used to promote their labor market position. In addition, it is possible that after fulfilling the civic integration obligation, there is more room to look for work (mentally and considering time available).

The region where Syrian refugees live is also important for their employment (see also: Åslund et al., 2000; Åslund and Rooth, 2007; Bevelander and Lundh, 2007; Larsen, 2011; Gerritsen et al., 2018; Aksoy et al., 2020; Fasani et al., 2022; Kanas and Kosyakova, 2022). The recent arrivals in this study are more likely to find employment in an environment with a relatively lower unemployment rate than in a context with less favorable labor market conditions. The positive impact of favorable regional labor market conditions probably applies to everyone looking for work. However, whereas the general population can choose where they want to live and change locations if they expect opportunities to be more favorable, refugees do not choose the region they are going to live in themselves and are thus more bound to regional opportunities. Our study shows this can have negative consequences for finding employment. A theoretical contribution following these results is that policy can work in two directions; on the one hand, policy can contribute to (re)gathering resources (Hobfoll, 2001), which can positively impact newcomers' labor market positions, on the other hand, policy can also be seen as a post-migration stressor, counteracting newcomers' participation to some extent.

Considering individual resources, pre-migration (unknown or lower skilled work in Syria), post-migration human capital (host country language) and personal capital (mental health) were found to be important for Syrian refugees' labor market success. The findings regrinding pre-migration work experience partly resonate with our expectation; it might be easier to secure employment for those with unknown/low skilled work experience compared to no work experience, but not as much for those with high skilled work experience compared to no work experience, as the latter two might both more difficultly translate due to the job availability in the destination countries. As has also been shown in other research into the participation of refugees, women, the elderly, those who arrived later and those with children living at home occupy a less favorable position on the labor market. Volunteering also seemed to decrease one's chance for employment, but this might be due to a lock-in effect, i.e., those who can't find a job will start volunteering and are then less likely to find paid employment. Interestingly, we did not find significant associations between Syrians' pre-migration education, certificate obtained in the Netherlands, social contact, as well as physical health and their employment. This might be explained by the fact that the within-person estimation excludes respondents who have not changed between the observed time points, which makes it difficult to properly estimate these relationships. The additional RE models did show a negative relation between having a physical disorder and employment and an increased chance to be employed for Syrians who obtained a certificate in the Netherlands, but not for social contacts.

Notwithstanding our contributions, there are some limitations to this study. While we focused on Syrians' employment, we could not distinguish between type of employment (employed on temporary or permanent contract, parttime or fulltime, self-employed) and job quality. We do know from other studies that immigrants and especially refugees often hold a precarious position on the labor market, working in low-skilled and temporary jobs (Kanas and Steinmetz, 2021). While we find a positive trend for employment, it is thus likely that those who are employed find themselves in such precarious positions. Moreover, dynamics in the groups of employees and those self-employed may differ (see for example: Wauters and Lambrecht, 2008; Berry, 2012; Alrawadieh et al., 2019) but the number of self-employed respondents was too low in our data, which made it impossible to distinguish between the two for now. As we focus on recent arrivals, we were mainly interested in who already participates in the labor market shortly after arrival, rather than in what way. This also made it possible to include all respondents in the working population, as for example students with part-time jobs also count as those “employed”. Future studies could investigate labor market characteristics explaining the type of employment and job quality of the jobs recent arrivals are able to secure in more detail, possibly limiting its sample to those whose main activity is employment or being (unintentionally) unemployed. Nevertheless, our analyses showed similar results for both the full sample as the restricted sample of those between 25 and 55 years.

Next, while our study provides insight in the impact of various policy characteristics on changes in Syrian refugees' employment, the effect of policy should ultimately be tested utilizing randomized controlled trials, comparing refugees subject to different policies. In the case of our study, all individuals are subject to the same policy, but there was difference regarding their interaction with the implementation and the phase they were in regarding civic integration. Since we know quite a lot about all kinds of background characteristics through combing survey and administrative panel data, we were able to estimate the impact of these policy characteristics more accurately than other generally cross-sectional studies employing less extensive data sources. This provides us with an indication of the impact of these policy characteristics but could be further evaluated using comparison groups. Related to this, we cannot completely rule out self-selection when it comes to those who engaged in activities during reception. While the opportunity to engage in such activities can be understood as a policy characteristic, the extent to which these activities are provided may differ and newcomers are not obliged to engage.9 Our analyses show the impact of those who had the opportunity and took it, but this would be purer if it was part of the policy that every center provided similar activities, and everyone had to engage. Moreover, while showing the impact of the regional unemployment rate is an addition to previous studies, indicating differences in (finding) employment among refugees assigned to different regions, more regional aspects can be of influence, such as the population composition of the neighborhood, and local policy implementation (Bevelander and Lundh, 2007) for example, the local supply of language courses (Kanas and Kosyakova, 2022). Future research could include a variety of these characteristics to be able to make more precise statements about the impact of regional differences and dispersal policies.

In addition, we cannot make statements about the role of the labor market itself and, for example, the impact of discrimination. Syrian refugees indicate they have little experience with discrimination in the Netherlands (Dagevos and Miltenburg, 2020), but this is often difficult for individuals to assess. It is thus not unlikely that discrimination does play a role. In times of economic downturn, the role of discrimination tends to increase. Combined with the often-vulnerable position in which many refugees find themselves, this is not hopeful for (the development of) their labor market positions and will have to be considered in future studies.

In conclusion, though refugees often experience a difficult start on the labor market, five years after the large influx of refugees the share of them being employed has increased. We focused on refugees who have only been in the Netherlands for a relatively short time, during which they were highly subject to different forms of policy. Our study shows these policy characteristics are key for the start of refugees' labor market participation, which is an important finding regarding refugees' precarious position and could apply to other countries as well. A short and active reception period can be beneficial and shows that reception policy should be regarded as a first form of integration policy. Through completing the civic integration obligation, refugees can furthermore gain resources relevant to their labor market position. Regional labor market conditions also play a role, the regional unemployment rate can negatively impact refugees' opportunities for employment, and it thus matters which region refugees are assigned to. As for other migrants, post-migration (language) and personal (health) capital are also key in promoting Syrians' employment. By using panel data, we were able to better distinguish dynamics in Syrian's finding employment and thus the impact of the various characteristics. Yet, some relationships were difficult to estimate due to the little variation between the two measurement points. Nevertheless, we showed both policy and individual characteristics can be understood in terms of resources (Hobfoll, 2001), benefitting, or hampering refugees' employment. Given the precarious position of refugees on the labor market, gaining insight into characteristics of labor market success has always been important, but perhaps even more in the prevailing economic crisis. Refugees' precarious labor market position will likely be disproportionately damaged and attention to their labor market positions in times of crisis, therefore, remains valuable.

Data availability statement

The survey data is archived at the research institutes involved. Administrative data is available from Statistics Netherlands. Restrictions apply to the accessibility of these data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ZGF0YUBzY3Aubmw= or bWljcm9kYXRhQGNicy5ubA==.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants at the time of data collection and analyses in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

RD, WH, and JD contributed to the design and implementation of the research. RD took the lead in analyzing the data. All authors dedicated their time to the writing and revising of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The surveys used for this study are part of a larger project (Longitudinal cohort study permit holders), conducted at the request of and funded by four Dutch ministries.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2022.1028017/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Though most likely connected to settlement policies, we were not able to include characteristics of the social context–such as discrimination–in this study.

2. ^Almost all newcomers in the Netherlands are obliged to pass this integration exam within three years. Sanctions are imposed to punish those who fail. There are some exceptions; refugees with severe health issues can apply for dispensation. In addition, there is an “exemption due to demonstrable efforts”. Those with a certificate for education in the Netherlands can also opt for an exemption as the certificate can serve as proof of having the necessary skills. Moreover, refugees can apply for more time to pass due to various reasons https://www.inburgeren.nl/geen-examen-doen/ziek-of-handicap.jsp

3. ^The data employed in this study were gathered before the Corona outbreak in 2020 and do thus not account for the current economic climate.

4. ^The data collection was led by The Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP). There was collaboration with Statistics Netherlands (CBS), the Research and Documentation Center (WODC), the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), and the research agency Labyrinth.

5. ^See Kappelhof (2018) for more details on the survey design and implementation.

6. ^Variables regarding employment and most individual background characteristics arise from the self-reported survey data. Information about the length of the reception stay, compliance with the civic integration requirement, regional unemployment rate and being a family migrant were taken from the registers.

7. ^See Appendix A for the exact wording of this and all the other items as included.

8. ^To assess respondents' mental health, the Mental Health Inventory 5 (MHI-5) was used. The MHI-5 is a measuring instrument that gives an impression of people's mental health in the last four weeks at the time of the survey (Rumpf et al., 2001). Respondents were asked how often they felt: very nervous, depressed, and gloomy, calm, so bad that nothing could cheer you up and happy. They could answer these questions on a six-point scale, ranging from (1) constantly to (6) never. Answers to the items calm and happy were reversed. For each person, the values of all five questions were recoded to a 0–5 scale and multiplied by 4, next a sum score was calculated based on the five items. In this way, the minimum score is 0 and the maximum score is 100.

9. ^The policy regarding these activities is twofold. For those who received a permit but are awaiting housing to be available, there is the program ‘preparation for civic integration' (see Bakker et al., 2020 for more information), This program started in 2008 and intensified in 2016, consisting of language lessons, knowledge about Dutch society and labor market and personal accompaniment. The program is generally offered the same way, but there is room for creativity. Those awaiting a decision can learn Dutch themselves, participate in Dutch classes by volunteers, or engage in (volunteer) work, but the extent to which such activities are provided differs.

References

Åslund, O., Edin, P.-A., and Fredriksson, P. (2000). Settlement Policies and the Economic Success of Immigrants. Stockholm, Sweden: Nationalekonomiska institutionen.

Åslund, O., and Rooth, D.O. (2007). Do when and where matter? Initial labour market conditions and immigrant earnings. Econ. J. 117, 422–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02024.x

Ager, A., and Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: a conceptual framework. J. Refug. Stud. 21, 166–191. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fen016

Aksoy, C. G., Poutvaara, P., and Schikora, F. (2020). First Time Around: Local Conditions and Multi-Dimensional Integration of Refugees, SOEP Papers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research, No. 1115. Berlin: Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW). doi: 10.31235/osf.io/nsr8q

Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed Effects Regression Models. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications. doi: 10.4135/9781412993869

Alrawadieh, Z., Karayilan, E., and Cetin, G. (2019). Understanding the challenges of refugee entrepreneurship in tourism and hospitality. Serv. Ind. J. 39, 717–740. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2018.1440550

Ambrosetti, E., Dietrich, H., Kosyakova, Y., and Patzina, A. (2021). The impact of pre- and postarrival mechanisms on self-rated health and life satisfaction among refugees in Germany. Front. Sociol. 6:693518. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.693518

Bakker, L., Bekkers, R., Reitsma, J., Sederel, C., Smets, P., and Younes, Y. (2018). “Vrijwilligerswerk: stimulans voor tijdige participatie en integratie? Monitor- en evaluatie onderzoek vrijwilligerswerk door asielzoekers en statushouders die in de opvang verblijven”. Den Haag/Barneveld: Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid/Significant.

Bakker, L., Dagevos, J., and Engbersen, G. (2014). The importance of resources and security in the socio-economic integration of refugees. A study on the impact of length of stay in asylum accommodation and residence status on socio-economic integration for the four largest refugee groups in the Netherlands. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 15, 431–448. doi: 10.1007/s12134-013-0296-2

Bakker, L., Dagevos, J., and Engbersen, G. (2017). Explaining the refugee gap: a longitudinal study on labour market participation of refugees in the Netherlands. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 43, 1775–1791. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1251835

Bakker, L., Zwanepol, M., van der Maas-Vos, G., Kalisvaart, I., and Blom, M. (2020). Evaluatie programma Voorbereiding op de Inburgering. Barneveld: Significant.

Battisti, M., Giesing, Y., and Laurentsyeva, N. (2019). Can job search assistance improve the labour market integration of refugees? Evidence from a field experiment. Labour Econ. 61(101745). doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2019.07.001

Beiser, M. (2006). Longitudinal research to promote effective refugee resettlement. Transcult. Psychiatry. 43, 56–71. doi: 10.1177/1363461506061757

Berry, S. E. (2012). Integrating refugees: the case for a minority rights based approach. Int. J. Refugee La. 24, 1–36. doi: 10.1093/ijrl/eer038

Bevelander, P., and Lundh, C. (2007). Employment Integration of Refugees: The Influence of Local Factors on Refugee Job Opportunities in Sweden, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 2551. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.958714

Blom, M., Bakker, L., Goedvolk, M., van der Maas, G., and van Plaggenhoef, W. (2018). “Systeemwereld versus leefwereld: Evaluatie Wet Inburgering 2013”. Barneveld: Significant Public.

Boot, N., Miltenburg, E., and Dagevos, J. (2020). “Inburgering” in Syrische statushouders op weg in Nederland. De ontwikkeling van hun positie en leefsituatie, Dagevos, J., Miltenburg, E., de Mooij, M., Schans, D., Uiters, E., Wijga, A. (eds). (Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau) p. 32–41.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, Richardson, J. G. (eds). (New York: Greenwood) p. 241–258.

Brüderl, J., and Ludwig, V. (2019). Applied Panel Data Analysis Using Stata. Available online at: https://www.ls3.soziologie.uni-muenchen.de/studium-lehre/archiv/teaching-marterials/panel-analysis_april-2019.pdf (accessed July 20, 2022).

Carrington, K., McIntosh, A. F., and Walmsley, D. J. (2007). The Social Costs and Benefits of Migration into AUSTRALIA. Biddeford, ME: University of New England.

Cheng, Z., Wang, B. Z., and Taksa, L. (2019). Labour force participation and employment of humanitarian migrants: evidence from the building a new life in australia longitudinal data. J. Busi. Ethics. 1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04179-8

Cheung, S. Y., and Phillimore, J. (2014). Refugees, social capital, and labour market integration in the UK. Sociology. 48, 518–536. doi: 10.1177/0038038513491467

Chiswick, B. R., and Miller, P. W. (2009). The international transferability of immigrants' human capital. Econ. Educ. Rev. 28, 162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2008.07.002

Clausen, J., Heinesen, E., Hummelgaard, H., Husted, L., and Rosholm, M. (2009). The effect of integration policies on the time until regular employment of newly arrived immigrants: evidence from Denmark. Labour Econ. 16, 409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2008.12.006

Colic-Peisker, V., and Tilbury, F. (2007). Integration into the australian labour market: the experience of three “visibly different” groups of recently arrived refugees. Int. Migrat. 45, 59–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2007.00396.x

Connor, P. (2010). Explaining the refugee gap: economic outcomes of refugees versus other immigrants. J. Refug. Stud. 23, 377–397. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feq025

Correa-Velez, I., Barnett, A. G., and Gifford, S. (2013). Working for a better life: Longitudinal evidence on the predictors of employment among recently arrived refugee migrant men living in Australia. Int. Migrat. 53, 321–337. doi: 10.1111/imig.12099

CPB and SCP. (2020). Kansrijk integratiebeleid. Den Haag: Centraal Planbureau en Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau.

Dagevos, J., and Miltenburg, E. (2020). “Discriminatie en acceptatie.,” in Syrische statushouders op weg in Nederland. De ontwikkeling van hun positie en leefsituatie., Dagevos, J., Miltenburg, E., de Mooij, M., Schans, D., Uiters, E., and Wijga, A. (eds). Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Damen, R. E. C., Dagevos, J., and Huijnk, W. (2021). Refugee reception re-examined: a quantitative study on the impact of the reception period for mental health and host country language proficiency among Syrian refugees in the Netherlands. J. Int. Migrat Integrat. 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s12134-021-00820-6

de Vroome, T., and van Tubergen, F. (2010). The employment experience of refugees in the Netherlands. Int. Migr. Rev. 44, 376–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2010.00810.x

Diehl, C., Lubbers, M., Mühlau, P., and Platt, L. (2016). Starting out: new migrants' socio-cultural integration trajectories in four European destinations. Ethnicities. 16, 157–179. doi: 10.1177/1468796815616158

DiPrete, T. A., and Eirich, G. M. (2006). Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: a review of theoretical and empirical developments. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 32, 271–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.32.061604.123127

Edin, P.-A., Fredriksson, P., and Åslund, O. (2003). Ethnic enclaves and the economic success of immigrants—evidence from a natural experiment. Q. J. Econ. 118, 329–357. doi: 10.1162/00335530360535225

Fasani, F., Frattini, T., and Minale, L. (2022). (The Struggle for) Refugee integration into the labour market: evidence from Europe. J. Econ. Geography. 22, 351–393. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbab011

Fossati, F., and Liechti, F. (2020). Integrating refugees through active labour market policy: a comparative survey experiment. J. Eur. Soc. Policy. 30, 601–615. doi: 10.1177/0958928720951112

Friedberg, R. M. (2000). You can't take it with you? Immigrant assimilation and the portability of human capital. J. Labor Econ. 18, 221–251.

Gerritsen, S., Kattenburg, M., and Vermeulen, W. (2018). Regionale plaatsing vergunninghouders en kans op werk. Den Haag: CPB.

Geurts, N., and Lubbers, M. (2017). Dynamics in intention to stay and changes in language proficiency of recent migrants in the Netherlands. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 43, 1045–1060. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1245608

Ghorashi, H. (2005). Agents of change or passive victims: the impact of welfare states (the case of the Netherlands) on refugees. J. Refug. Stud. 18, 181–198. doi: 10.1093/refuge/fei020

Hainmueller, J., Hangartner, D., and Lawrence, D. (2016). When lives are put on hold: lengthy asylum processes decrease employment among refugees. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600432. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600432

Hartog, J., and Zorlu, A. (2009). How important is homeland education for refugees' economic position in The Netherlands? J. Popul. Econ. 22, 219–246. doi: 10.1007/s00148-007-0142-y

Heath, A., and Cheung, S. Y. (2007). Unequal Chances: Ethnic Minorities in Western Labour Markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.5871/bacad/9780197263860.001.0001

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 50, 337–421. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Huddleston, T., Niessen, J., and Tjaden, J. D. (2013). Using EU Indicators of Immigrant Integration. Brussel: European Commission DG Home Affairs.

Hvidtfeldt, C., Schultz-Nielsen, M. L., Tekin, E., and Fosgerau, M. (2018). An estimate of the effect of waiting time in the Danish asylum system on post-resettlement employment among refugees: separating the pure delay effect from the effects of the conditions under which refugees are waiting. PLoS ONE. 13, e0206737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206737

Kanas, A., and Kosyakova, Y. (2022). Greater local supply of language courses improves refugees' labor market integration. Eur. Soc. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2022.2096915. [Epub ahead of print].

Kanas, A., and Steinmetz, S. (2021). Economic outcomes of immigrants with different migration motives: the role of labour market policies. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 37, 449–464. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcaa058

Kanas, A., and van Tubergen, F. (2009). The impact of origin and host country schooling on the economic performance of immigrants. Social Forces. 88, 893–915. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0269

Kanas, A., Van Tubergen, F., and Van der Lippe, T. (2011). The role of social contacts in the employment status of immigrants: a panel study of immigrants in Germany. Int. Sociol. 26, 95–122. doi: 10.1177/0268580910380977

Kappelhof, J. (2018). Survey Onderzoek Nieuwe Statushouders in Nederland 2017. Verantwoording van de opzet en uitvoering van een survey onder Syrische statushouders. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Koenig, M., Maliepaard, M., and Güveli, A. (2016). Religion and new immigrants' labor market entry in Western Europe. Ethnicities. 16, 213–235. doi: 10.1177/1468796815616159

Kogan, I. (2007). Working Through Barriers Host Country. Institutions and Immigrant Labour Market Performance in Europe. Springer: Dordrecht.

Koopmans, R. (2016). Does assimilation work? Sociocultural determinants of labour market participation of European Muslims. J. Ethn. Migr. 42, 197–216. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1082903

Kosyakova, Y., and Brenzel, H. (2020). The role of length of asylum procedure and legal status in the labour market integration of refugees in Germany. SozW Soziale Welt. 71, 123–159. doi: 10.5771/0038-6073-2020-1-2-123

Kosyakova, Y., and Kogan, I. (2022). Labour market situation of refugees in Europe: the role of individual and contextual factors. Front. Political Sci. 4:977764. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.977764

Kosyakova, Y., Kristen, C., and Spörlein, C. (2022). The dynamics of recent refugees' language acquisition: How do their pathways compare to those of other new immigrants? J Ethnic Migration Stud. 48, 989–1012. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2021.1988845

Laban, C. J., Gernaat, H. B., Komproe, I. H., Schreuders, B. A., and De Jong, J. T. (2004). Impact of a long asylum procedure on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in The Netherlands. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 192, 843–851. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000146739.26187.15

Larsen, B. R. (2011). Becoming part of welfare scandinavia: integration through the spatial dispersal of newly arrived refugees in Denmark. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 37, 333–350. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2011.521337

Lochmann, A., Rapoport, H., and Speciale, B. (2019). The effect of language training on immigrants' economic integration: empirical evidence from France. Eur. Econ. Rev. 113, 265–296. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2019.01.008

McMichael, C., Nunn, C., Gifford, S. M., and Correa-Velez, I. (2015). Studying refugee settlement through longitudinal research: Methodological and ethical insights from the Good Starts Study. J. Refug. Stud. 28, 238–257. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feu017

Nafukho, F. M., Hairston, N., and Brooks, K. (2004). Human capital theory: implications for human resource development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 7, 545–551. doi: 10.1080/1367886042000299843

Nielsen, S. S., Norredam, M., Christiansen, K. L., Obel, C., Hilden, J., and Krasnik, A. (2008). Mental health among children seeking asylum in Denmark–the effect of length of stay and number of relocations: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 8, 293. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-293

Odé, A., Paulussen-Hoogeboom, M., and Witvliet, M. (2013). De bijdrage van inburgering aan participatie. Amsterdam: Regioplan.

Ott, E. (2013). The labour market intergation of resettled refugees. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Phelps, E. S. (1972). Inflation Policy and Unemployment Theory: The Cost-Benefit Approach to Monetary Planning. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Phillimore, J. (2011). Refugees, acculturation strategies, stress and integration. J. Soc. Policy 40, 575–593. doi: 10.1017/S0047279410000929

Phillimore, J., Humphris, R., and Khan, K. (2018). Reciprocity for new migrant integration: Resource conservation, investment and exchange. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 44, 215–232. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341709

Rumpf, H.-J., Meyer, C., Hapke, U., and John, U. (2001). Screening for mental health: validity of the MHI-5 using DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders as gold standard. Psychiatry Res. 105, 243–253. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00329-8

Ryan, D., Dooley, B., and Benson, C. (2008). Theoretical perspectives on post-migration adaptation and psychological well-being among refugees: towards a resource-based model. J. Refug. Stud. 21, 1–18. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fem047

Schunck, R., and Perales, F. (2017). Within-and between-cluster effects in generalized linear mixed models: a discussion of approaches and the xthybrid command. Stata J. 17, 89–115. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1701700106

Smets, P., Younes, Y., Dohmen, M., Boersma, K., and Brouwer, L. (2017). Sociale media in en rondom de vluchtelingen-noodopvang bij Nijmegen. Mens en Maatschappij 92, 395–420. doi: 10.5117/MEM2017.4.SMET

Smyth, G., and Kum, H. (2010). ‘When they don't use it they will lose it': professionals, deprofessionalization and reprofessionalization: the case of refugee teachers in Scotland. J. Refug. Stud. 23, 503–522. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feq041

van Liempt, I., and Staring, R. (2020). Nederland papierenland. Syrische statushouders en hun ervaringen met participatiebeleid in Nederland. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Verkade, E. M., and Vermeulen, W. (2005). “The cpb regional labour market model: A tool for long term scenario construction,” in A survey of spatial economic planning models in the Netherlands: Theory, application, and evaluation, van Oort, F., Thissen, M., and van Wissen, L. (eds). (Rotterdam/Den Haag, NAI Uitgevers/Ruimtelijk Planbureau) p. 45–62.

Vitus, K. (2011). Zones of indistinction: family life in Danish asylum centres. Distinktion: Scandinavian Journal of Social Theory (rDIS). 12, 95–112. doi: 10.1080/1600910X.2011.549349

Walther, L., Kröger, H., Tibubos, A. N., Ta, T. M. T., von Scheve, C., Schupp, J., et al. (2019). Psychological Distress among Refugees in Germany – a Representative Study on Individual and Contextual Risk Factors and the Potential Consequences of Poor Mental Health for Integration in the Host Country. Berlin: DIW Berlin, The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033658

Wauters, B., and Lambrecht, J. (2008). Barriers to refugee entrepreneurship in Belgium: Towards an explanatory model. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 34, 895–915. doi: 10.1080/13691830802211190

Waxman, P. (2001). The economic adjustment of recently arrived bosnian, afghan and iraqi refugees in Sydney, Australia. Int. Migrat. Rev. 35, 472–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2001.tb00026.x

Keywords: labor market participation, employment, refugees, panel analysis, resources, recent arrivals, reception policy

Citation: Damen REC, Huijnk W and Dagevos J (2023) Explaining recently arrived refugees' labor market participation: The role of policy characteristics among Syrians in the Netherlands. Front. Hum. Dyn. 4:1028017. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2022.1028017

Received: 25 August 2022; Accepted: 13 December 2022;

Published: 06 January 2023.

Edited by:

Yuliya Kosyakova, Institute for Employment Research (IAB), GermanyReviewed by:

Jannes Jacobsen, German Center for Integration and Migration Research (DeZIM), GermanyVerena Seibel, Utrecht University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2023 Damen, Huijnk and Dagevos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roxy Elisabeth Christina Damen,  ZGFtZW5AZXNzYi5ldXIubmw=

ZGFtZW5AZXNzYi5ldXIubmw=

Roxy Elisabeth Christina Damen

Roxy Elisabeth Christina Damen Willem Huijnk2

Willem Huijnk2