95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 29 November 2021

Sec. Environment, Politics and Society

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2021.769365

This article is part of the Research Topic Political Ecologies of COVID-19 View all 11 articles

Drawing on qualitative analysis and anthropological histories, we argue that deforestation rates in the Inter-Andean Valleys and in the Amazon Belt of Colombia reflect the specific role of the military in different articulations of the political forest along with new connections between conservation and the war on drugs. This paper examines the increase in deforestation in Colombia in 2020 that partially coincided with the “lockdown” imposed to curb the spread of COVID-19. Early media analysis linked this with the redeployment of military forces away from forest protection to impose lockdown restrictions. However, closer investigation reveals significant regional variation in both the reorganisation of military groups, and in the rate at which deforestation has materialised; military presence has increased in some regions, while in others deforestation has increased. To explain this, we unpack the “biopolitical” dimensions of international conservation to show how the specific deployment of military groups in Colombia reflects an interplay between notions of the protection of (species) life, longer colonial histories, and more recent classification of geographies in terms of riskiness and value.

This paper is motivated by a sharp uptick in deforestation in Colombia during early 2020, partially coinciding with the “lockdown” imposed by national governments to suppress the reproduction rate of a novel coronavirus first identified in China in late 2019, whose rapid spread was declared a Public Health Emergency by the World Health Organisation on the 30th January 2020 (WHO, 2020). Measures ranged from mandatory geographic quarantines to non-mandatory recommendations to stay at home, the closure of certain types of businesses and bans on events and gatherings. By mid-April of 2020, it was estimated that a third of the world’s countries were in some kind of lockdown (Buchholz, 2020), with impacts already evident on the global economy, transportation systems and business (Bates et al., 2020; Spenceley, 2020, forthcoming). In Colombia, lockdown measures were introduced on March 17, 2020 and began to be relaxed in August 2020. Some are still in place at the time of writing. The measures adopted in Colombia included restrictions on mobility; closures of public places, and mobility restrictions on inter-municipal roads overnight.

This sudden reduction of human movement had an immediate impact on environmental processes: early media reports suggested that bird populations and other species were flourishing in cities (The Washington Post, 2020; Revista, 2020b); Revista, 2020a hole in the ozone layer was self-repairing (UN, 2020; Arora et al., 2020), and that air quality improved in many cities (BBC, 2020; He et al., 2020). While it was clear that such effects might be temporary, lockdown was linked with positive impacts on rates of human-induced climate change (UNEP, 2020). However, the world’s forests have, in some cases, been impacted in exactly the opposite direction. For example, illegal timber extraction and illegal wildlife trafficking have been observed on the rise in Ecuador, along with the expansion of oil extraction and mining.1 Meanwhile, allowing for seasonal trends, forest fires and deforestation rates in the Andean and Amazon regions of Latin America rose or remained high throughout 2020 (CNN, 2020), a trend noted mid-year by global media (FCDS, 2020b; El, 2020; Mongabay, 2020).

Initial analysis linked these rates with a rise in the activities of illegal armed groups, speculatively associated with the redeployment of the state military away from rural forests and into urban centres to enforce lockdown regulations. However, these trends are not geographically uniform across Colombia: in some forested areas, such as the high Andes, deforestation rates appeared to be little affected despite the overall trend. Meanwhile, it is important to note that, even as state armies were moved away from at-risk areas in, for example, the Amazon, other para-state forces were able to increase, precisely due to the withdrawal of monitoring from these areas, and the subsequent expansion of influence on the part of illegal armed groups.

In this sense, and given Colombia’s complex history of policing, it is a simplification to speak of the “absence” of the military. Additionally, in other regions, such as the low Andean Forest, military forces actually increased at points during lockdown in relation to the longer history of the war on drugs in this region. In this paper we attempt to explain this geographical variability by unpicking the longer histories of these socio-environmental dynamics, such as the longstanding militarisation of conservation activities in particular conflicted areas, and the effects of colonial imaginations on the ways different regions are imagined and governed today. Through our analysis, we argue that the differential patterns of militarisation observable through lockdown do not reduce to the formula “removing armies = increased deforestation”: instead, they reveal important dimensions of power and spatial control in play through the governance of Colombia’s forests, which we characterise through the vocabulary of biopolitics.

Michel Foucault’s concept of biopolitics refers to the exercise of power to manage, regulate and enable the “life” of specific human and biological populations through the optimisation of these lives (1995; 2008; 2009; Lemke, 2011). This establishes orders and taxonomies among human and nonhuman populations, and defines certain ‘outside’ groups as risks or threats to the state’s productive interests. In the domain of conservation—which, in the twenty-first century is an elaborate international enterprise joining together political-economic rationalities, concepts of security, and biological ideas—the need to protect biodiversity frequently becomes a pretext to surveil potential “enemies” of the state, especially in conflicted areas (Bocarejo and Ojeda, 2016; Magliocca et al., 2019). Political ecologists studying these dynamics in the institutions of international conservation note a growing emphasis on military presence and surveillance technologies in conservation in the Global South—leading to the identification of a wider trend of “green militarization” (Lunstrum, 2014) or the ‘securitization’ of conservation (Massé and Lunstrum, 2016).

Green militarisation, meanwhile, denotes the elaboration of geopolitical interests through the way that conservation areas are geographically articulated and policed. Such interests include state concerns with quelling potential insurgency or containing minority groups perceived as “risky.” It also includes the priorities of international actors, which come to shape the specific contours of new scientific projects, economic tourism opportunities, and strategic (geo)political involvements in state conflict. Meanwhile, the language of environmentalism provides an acceptable front for such efforts, often covering over their racialised effects. In Colombia, green militarisation cannot, in this sense, be understood without understanding the ways that national militarisation, on the one hand, and international involvement, on the other, have been configured during the internal armed conflict (which began in 1964). The introduction of sanctions, mobility restrictions, and assassinations by armed groups in our case sites recalls—and builds upon—the exceptional powers afforded to the paramilitary and guerrillas in earlier decades of war, albeit interacting in new ways with more recent modes of biopolitical power associated with (international) conservation governance. Yet the patterns of armed containment, intensified control, and what we refer to as “active abandonment”—the exposure of particular groups to physical violence through the withdrawal of state governance—map onto histories that are much older than the recent rounds of conflict. Indeed, we suggest that they have roots in colonial histories and relationships.

Beyond accounting for the geographically differentiated patterns of militarisation that help explain how and where deforestation has increased during lockdown, in this paper we aim to make a theoretical intervention, recasting concepts of biopolitics into explicitly decolonial terms. This means following how conditions associated with colonial knowledge production (about species life and human bodies) have enabled the insertion of conditions of exceptional rule into the heart of biopolitical forms of governance. This is a pattern we suggest can be observed in many post-colonial states around the world, where National Parks and biodiversity hotspots already focalise enduring conflicts over the use of resources and access to land. In practice, what we are suggesting is that the state’s geopolitical interest in controlling and containing particular bodies is made more convenient and efficient through the operation of international conservation and its associated forms of monitoring, security and surveillance.

Moreover, the exceptional circumstances of the global pandemic, which authorise new forms of exceptional rule over everyday life (Barros et al., 2020; Karaseva, 2020), have configured a moment where the powers of the military and associated illegal armed groups (paramilitary and guerrilla dissidents in association with drug-trafficking mafias) have increased in conservation areas. Illegal armies—officially distinct from state operations, but which in contexts like Colombia are allotted distinctive powers—may thus carry out deforestation and human rights abuses without being challenged. Through our case studies we will suggest that the moral coding of the countryside via colonial administrations prior to armed conflict, together with the unpacking of international conservation agendas in recent decades, have interacted to enable pockets of exceptional rule during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. Beyond the forms of racialised exclusion associated with biopolitics, these pockets expose some populations to sustained and systematic violence beyond the rule of law.

To this end, the remainder of this article is organised into four parts. Firstly, we set the scene for our analysis by examining the ways that green militarisation has been explored through recent political ecology and political geography scholarship. Secondly, we unpack the Colombian context to show how contemporary forms of militarisation build on special powers associated with the armed conflict as well as the elaboration of international conservation policies and practices. Thirdly, we present the case studies we will examine in more detail and give an overview of our methodology. In the fourth part, we analyse the situation in the two forested sites under discussion—the Serranía de las Quinchas in the Inter-Andean valleys and Colombia’s Amazon belt—in relation to green militarisation under lockdown conditions. The narratives we present here draw on the qualitative data and extensive networks developed by a team of social scientists as part of an interdisciplinary research project on forest resilience (2019–2021),1 alongside additional interviews and historical analysis. In concluding the paper, we suggest important academic and policy implications of the insights we present, especially for how international publics are mobilised to act to address deforestation.

Recent work in the interdisciplinary field of political ecology has led to nuanced understandings of how the making of conservation spaces and rules function to contain populations identified as “threats” to state governments (Ojeda, 2012; Büscher and Ramutsindela, 2015; Devine et al., 2020), or to exclude minority groups or those perceived as “risky” (Ybarra, 2012; Verweijen and Marijnen, 2018). While newer models for conservation—such as participatory models for community forest management—may have been lauded internationally for their capacity to protect threatened species, they have still tended to be implemented via top-down processes that exclude local people (Sundberg, 2003) and afford states the powers to bring conflicted areas under their control through extraordinary legal measures (Adams and Hutton, 2007). Thus, the introduction of new boundaries for protected areas has been used to justify the displacement of indigenous groups, as well as the roll-back of social amenities and protection (Springer and &LeBillon, 2016), and the introduction of intelligence networks, media, and drones to police minorities (Brock&Dunlap, 2018). In Latin America, as elsewhere, such moves have resulted in the entanglement of military forces with everyday conservation operations (Escobar, 2006; Kelly and Ybarra, 2016; Camargo and Ojeda, 2017), what this paper calls green militarisation. Over time, green militarisation normalises the presence of armed forces in conservation areas and contributes to the constitution “potential nature-destroyers”, subjects understood as enemies of conservation who must be removed if the environment is to be protected. This perhaps helps explain why over 80% of the major armed conflicts occurring globally between 1950 and 2000 were in conservation zones characterised by high biodiversity (Hanson et al., 2009: 578).

An understanding of biopolitics adds nuance to this analysis, illuminating how the development of international conservation—as an assemblage of funding mechanisms, biological registers, security, and monitoring practices, and notions of protection—has established a kind of logic for social governance via the management of species life. Here we draw specifically on Foucault, 2008; Foucault, 2009) ideas of biopolitics and biopower, which refer to forms of power that work on and with concepts of “life”, as rendered through the knowledge regimes associated with the biological sciences; notions of security (with the specific idea of an “insider” population to be protected from an “outside,” posing risk), and ideas of political economy associated with (neo)liberalism. In biopolitical rationalities for governing states, explains Foucault, definitions of the population to be governed are articulated through political-economic rationalities and security practices, to the point that the boundaries of belonging defining citizens from non-citizens feel natural (Rabinow and Rose, 2006; Biermann and Anderson, 2017). Throughout the histories of conservation, which have long been linked with the spatial projects of colonialism and imperial control, such rationalities render particular bodies a risk to the proliferation of life, even as they establish conservation practices to protect life’s value (Biermann and Mansfield, 2014).

Because vulnerable inhabitants are repeatedly framed as environmental threats or internal enemies in contemporary conservation discourses, old divisions and traumas associated with previous rounds of conflict are quickly resurfaced. This is particularly true in Colombia, where agendas for biodiversity protection and peace have tended to be imagined together, attracting major international funding and investment as if the one might secure the other (see, for example, UNDP, 2020; and the “Environments for Peace” project). In such interventions, specific environments continue to be coded by states in terms of pre-existing conflict, for example, as locations of “potential insurgency”, and are consequently transformed into regions of military containment, or rural dispossession, in the name of biodiversity protection. Forested areas and jungles, long represented as zones “out of control” and in need of securitisation, become reconstructed as “state forests” under careful regulation (Peluso and Vandergeest, 2011) in this imagination. However, framing disenfranchised peasants as potential nature-destroyers—rather than as potential green subjects as in Colombia’s high Andes—does little to quell potential conflict. When we refer to the “political forest” in this article, we mean to signal the multiple ways that forests, specifically those designated as conservation areas, become invested with multiple (geo)political agendas through their articulation in biopolitical terms.

As green militarisation—one effect of the elaboration of biopolitical modes of conservation in specific spatial contexts—has expanded, we consequently witness the emergence of a new war “by conservation” (Duffy, 2016), where conservation is re-framed as a tool to other ends. Beyond the idea of eliminating the risks to species conservation, force shifts here to seeing conservation as an integral part of a state’s strategy to achieve peace. Here, concepts of, and funds for, biodiversity protection become blurred with concepts and practices of national security, while enabling new mechanisms for the containment of actors perceived as “insurgent”, or occupying land intended for accumulation strategies. It is, then, perhaps unsurprising that scholars identify the making and governance of conservation areas with the production of “special” powers, which include the introduction of the military to address illegal poaching and logging, the right to surveillance, and the creation of new borders and boundaries (Hawkins and Paxton, 2019). In contexts such as Colombia, however, where whole regions are still coded in the popular imagination as either “paramilitary” or “resistance” areas, we can go further, and speak of the configuration of military formations that expose local populations systematically to harm, risk, and death. However, to understand how such formations have been produced, we must understand how the biopolitics of conservation overlaps in important ways with the performance of international policing of the narcotics trade. In Colombia, what is referred to as environmental protection increasingly refers to both conservation objectives (replete with associated ideas of risk management) and the control of rural areas seen as zones of cocaine production.

In much of Latin America, green militarisation is not only associated with the history of conservation but with the “war on drugs,” a notion officially inaugurated by President Nixon in the United States in 1971 as a “public enemy,” and the number one cause of social and public ill-health among young Americans. This overlapping “war” has been a key driver of the introduction of new strategies of spatial containment and for translating U.S. geopolitical interests into biopolitical control (Tate, 2015). In Colombia, these interests map closely onto the geographies of hidden enemies established through the most recent decades of the counterinsurgency war (Lyons, 2016), as well as the exceptional powers claimed during this period to use disproportionate force against peasants in remote rural areas (Ballvé, 2013). As an extensive literature has demonstrated, military practices deployed in the war on drugs—such as the movement of troops, forced eradication, the burning of cocaine laboratories and aerial fumigation with glyphosate—have adverse effects on the environment and human health (Smith et al., 2014; Camacho and Mejía, 2015; Bernal Cáceres, 2019). It is thus important to expose the contradictions in the ways that new discourse on conservation and anti-drug rhetoric have been layered together to imply that the objectives of one can be met through the other. This co-articulation legitimises further rounds of policing and spatial containment and, moreover, makes it possible to assert extraordinary measures outside state law.

However, it is perhaps even more significant that, in important environmental discourses, the cocaine production and the associated cultivation of illicit crops are increasingly framed as the main drivers behind deforestation and environmental degradation in contexts such as Colombia (Clerici et al., 2020) and in Central America (Devine, et al., 2020). Through this process, fighting the war on drugs and the war against illegal deforestation are rendered equivalent, allowing the resources of one to be directed into the other, and enabling the creation of specialist forces that claim to tackle both. By collapsing together multiple other drivers of deforestation, such as the expansion of the agricultural Frontier for land accumulation and cattle-ranching, this association adds force to the agenda of articulating strategies for forest protection that rely on militarisation (Asher and Ojeda, 2009), and that fight specifically against deforestation via the war on drugs in Colombia, through the creation of new military operations. For example, in April 2019, President Duque launched “Operation Artemisa,” an initiative led by the armed forces with the support of the Prosecutor’s Office, the Ministry of the Environment and IDEAM (The Institute of Hydrological, Meteorological and Environmental Analysis). This ongoing operation monitors deforestation trends using drones, Geographical Information Systems (GIS), and satellite technologies, leading to military operations. The first actions undertaken by Artemisa in 2019 generated protests by human rights and peasant organisations, especially in the Tinigua and Picachos Natural Parks, due to the purported use of excessive force in specific acts of containment (Mongabay, 2019).

This blending together of two wars consequently gives the military exceptional powers in the field of conservation, which we suggest can be illuminated by expanding the biopolitical logics at play in the associated term “necropolitics.” Following Achille Mbembe (2003, 2006; 2008), the term necropolitics refers to modes of the government of population life in former colonial territories, where technologies of exploitation remain prevalent and are embedded into specific structures of rule. Necropolitics interacts dynamically with Foucault’s idea of biopolitics, illuminating how zones of exception are established by coding part of the human population as “non-life,” or quasi-human. This neo-colonial practice subjects certain populations, e.g., indigenous groups or ethnic minorities, to death or sustained conditions of inhumanity, under the guise of fighting terror or establishing legitimate rule. Necropolitics cannot be reduced to the right to kill, but denotes practices that keep bodies in a condition between life and death, for example in conditions of slavery or continual subjection to violence. This is the form of power in play when massacres, femicide, execution, trafficking, and forced disappearances are systematically in play, and involve the legal-administrative mechanisms of the state, so that it is either unrecognised by legal authorities, or is not deemed illegal. In this paper, we identify a threshold at which the biopolitical rationalities associated with conservation—which already legitimise specific forms of racialised exclusion—cross over to authorise extra-legal forms of containment and control. In Colombia, this threshold has been configured through the extended armed conflict on the one hand, and the war on drugs on the other.

Where biopolitical modes of governing natural environments work through producing a regime of governability, which renders visible particular sources of threat, necropolitical modes rationalise the need for emergency securitisation or invasive surveillance through their articulation of such threats, for example by providing a grammar that justifies an increasing military presence to contain “unruly” elements. Necropolitics governs not only through enacting the right to kill, which is not usually permitted in biopolitical regimes, but by exposing othered populations to their own vulnerability or to the experience of dying slowly—to be “death-in-life” (Mbembe 2003:21). As a Cameroonian philosopher and political theorist of power and subjectivity in postcolonial Africa, Mbembe devised the concept of necropolitics for a context in which biopolitics was not sufficient to capture the experience he witnessed. From a decolonial sensibility or standpoint, biopolitics failed to explain the life and death regimes that took place and continue to take place in colonized countries. People living under necropower are actively abandoned: they are actively denied the possibility of being protected, helped, or saved from injury or death. Today we suggest that there is an overlap between the two modes of power as enacted in contemporary conservation, especially where the military is afforded powers to remove or contain groups framed as threats or potential eco-destroyers. Yet, while biopolitics operates by rendering (biological) life productive, necropolitics works by rendering death (or the confrontation of certain subjects with death) productive.

In the following section we explain how these necropolitical dimensions of conservation have developed in Colombia, with specific reference to the extraordinary measures introduced under conditions of internal war.

To understand how international conservation enables necropolitical practices in some regions and not others in a country like Colombia, it is important to grasp how colonial histories and geographies persist, through the way that forests and rural areas are coded according to concepts of riskiness and threat. Distinct from, yet persisting through, conservation strategies, the “moral topographies” configured by colonial rule in Colombia rendered the highlands and lowlands visible in distinct ways, conferring specific—apparently permanent—traits onto the people living there. Most famously, the anthropologist Michael Taussig (1987) used this term to explain how the lowlands have been consistently viewed as places of heat, humidity and suspicion, in association with their tropical climate and inaccessibility, whereas the highlands—where the capital Bogotá is situated—have been associated with an organised peasantry and Christian morality. This visuo-spatial imaginary persists today, perpetuating what has been characterised as a “geography of differences” (Roldan, 1998), “geographies of terror” (Oslender, 2008) and “fragmented territories” (Asher, 2020)—terms that describe an entrenchment of such stereotypes through the elaboration of subjects of conservation.

These geographies of difference were reinforced in subsequent centuries partly through the categorisation of distinct groups of rural peasants in Colombia, seen to require different levels of spatial control. In the Andean highlands campesinos [peasant farmers] have been consistently considered as rural communities requiring limited policing, and, more recently, as potential green subjects. Meanwhile, the lowlands have been strongly articulated through the alternative term colono [landless peasants], a category of subject historically constituted as distant from state institutions, which needs controlling. In Colombia’s social studies, the colono emerged during La Violencia ‘the Violence (1948–1958), when they were stripped of their lands by internal conflict. During the 1960s and 1970s, colonos were depicted as hardworking people, willing to adapt and display creativity despite difficulties. They were the protagonists of “progress” via the domestication of the jungles and the expansion of the agricultural Frontier. However, colonos were also figured as those who endlessly moved on to escape land accumulators and dispossession (Legrand, 1988; Molano, 2009). This association with displacement, landlessness and “cutting down the jungle” stigmatised the colonos over time. In subsequent decades they would be re-constituted as “internal enemies” associated with insurgency, in opposition to state rule (Sanchez and Meertens, 1984; Fajardo, 2005). More recently, colonos in other parts of Latin America have been seen as potential nature-destroyers whose practices do not fit the images of “green peasants” (Ojeda, 2012) or ecological indigenous peoples (Ulloa, 2017) promoted by environmental conservation. This new stigma interleaves with associations of resistance to the state and with guerrillas or drug-trafficking. During the COVID-19 lockdown, they have once again become central targets of surveillance and control.

In Colombia, necropolitical practices were prevalent during the crudest years of the armed internal conflict, especially between 2002 and 2008, when powers of exception were claimed by the state at both regional and national scales. Yet their history is much longer, for conditions of exception were re-created throughout the 20th century in the various internal wars and forms of territorial control enacted by legal and illegal armed groups (Leal, 2003; Richani, 2013; Angarita et al., 2015; Puentes-Cala, 2018). These practices were broadened and extended, however, in a series of government decrees issued between 1965 and 1968 that legalised the existence of private armed groups (“paramilitaries”). Of course, the guerrilla forces also practiced their own forms of control and mafia governance in the zones where they asserted sovereignty—which formed part of the justification of the need for paramilitary governance (Cubides, 1997). Supported by funding from landlords, businessmen and drug-traffickers, paramilitaries have, since this time, been largely associated with state counterinsurgency campaigns, although their independence from state mechanisms allows the state to denounce excessive violence and associated drug crimes without compromising its own legitimacy.

By the way they were defined, the zones inhabited by colonos took on lasting associations that would influence the ways that related protected areas were policed and governed. Areas under guerrilla control, such as large parts of departments in the Amazon (Caquetá, Putumayo, and Meta), were branded “red zones,” while the areas controlled by the paramilitary were regarded by the armed forces as zones of “special control.” People living in such areas came under the spatial rule and associated stigma of the dominating armed groups, and were automatically seen as their supporters, regardless of their position (Cancimante, 2014; Amador-Jiménez et al., 2020). Many of the forested areas that we know today as protected areas, were, at this time, framed by the state and media as impenetrable war jungles: places where the Colombian state had not yet arrived (Gutiérrez Sanín and Barón, 2005). The geographies of war have thus continued to inform geographies of conservation through such processes of spatial codification and the consolidation of extra-legal groups and powers.

These geographies of the operation of illegal groups (paramilitary and guerrilla forces) map strongly onto conservation areas, not least because, since 2016, reintegration zones for ex-combatants have been systematically designated close to biodiversity hotspots, targeted as areas for the promotion of sustainable development and ecotourism (Van BroeckGuasca and Vanneste, 2019). One interpretation of this is that conservation is being exploited as part of a civilising mission to convert former guerrillas into forest guardians, tourist guides and organic farmers. Another is that peace agendas and conservation agendas tend to be thought together, first, because “post-conflict” environmental programmes gain considerable traction with funders (Baptiste et al., 2017), and second, because conservation allows state concerns with quelling insurgency to become codified in internationally acceptable ways.

The overlapping agendas of militarisation and conservation seem set only to intensify in the “post-conflict” moment. The paramilitary demobilisation in 2006 and peace process with the FARC-EP in 2016 only partially and temporarily reduced conflict, and “neo”-paramilitary forces have since reconstituted themselves and rearmed. Meanwhile, FARC-dissident groups have expanded in the face of the failure of state entities to control drug-trafficking mafias. Much of the forest of the Amazon and Inter-Andean valley is now controlled by neo-paramilitary groups, FARC-EP dissidents and the ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional [National Liberation Army]) guerrilla movement, each working with different drug mafia cartels (PARES, 2018; FIP [Fundación Ideas para la Paz], 2019). They fight among themselves, but also make temporary alliances with each other, as with the state armed forces (Avila, 2020 in; El Espectador, 2020).

In the following sections we will build on these understandings of green militarisation, biopolitics and necropolitics to explore the geographically differentiated ways that armed forces have moved in Colombia under lockdown. These specific forms of green militarisation help explain how and why deforestation has increased in some areas during 2020–21.

The data in this paper was gathered primarily through fieldwork carried out between 2018 and 2021 by the socio-cultural component of an interdisciplinary research project, financed by a cross-council UK AHRC-NERC grant associated with the science hub Colciencias in Colombia. As part of this, we carried out extensive ethnographic fieldwork and participant observation in forested regions of the high and low Andes as well as eighty-five interviews and ten workshops related to topics such as environmental governance, gender and environment, oral histories of the forest and ecotourism as alternative livelihood.2 We carried out these interventions alongside ecological and palaeoecological teams analysing the long-term resilience of the forest. Our immersion in rural forest communities, networking with non-governmental organisations (NGOs), environmental activists and governance actors, put us in a prime position to observe the unfolding dynamics of increasing deforestation under lockdown. We received reports of illegal operations directly via our networks, which led us to publish, with other authors, a rapid response article containing early analysis of the spatial distribution of these new trends (see Amador-Jiménez et al., 2020). Throughout lockdown we remained in close contact with our research communities via mobile phone and web-calls and have become increasingly involved in regional-level environmental governance discussions relating to deforestation and beyond.

Our analysis focuses primarily on the Serranía de las Quinchas Regional Natural Park (“Quinchas”), located in the department of Boyacá in the central-eastern Andean lowlands. As a forested area of high biodiversity historically dominated by paramilitary forces, Quinchas provides an important example of a site that was further militarised, by state armed forces specifically, during lockdown. Contra popular accounts, the army was present in numbers while deforestation rates increased. Indeed, we see new necropolitical practices emerging at this time, including curfews, assassinations, and evictions, by both state armed forces and paramilitaries. The “exceptional” forces in play here are configured through reference to the war on drugs. This case contrasts with the transforming geographies of the Colombian Amazon, where deforestation rates have been very high in recent decades (OpenDemocracy, 2020; Murad and Pearse, 2018).3 In the Amazon, state armed forces were moved away from biodiversity hotspots during lockdown, although partially because of this, the authority of other illegal armed groups increased (Mongabay, 2020). It also enabled necropolitical practices, since the active abandonment of forest communities by state actors has exposed them to intensified forms of violence and dispossession. In neither case can increasing deforestation rates be explained by the demilitarisation of forest areas under lockdown: instead, they can be understood through the ways that biopolitical forms of forest governance cross over into necropolitics. Under necropolitics, the control of risk and threat passes to para-state entities that are not accountable to the rule of law nor the imperative of conserving species life operative under biopolitics. Unpacking the socio-environmental histories of these regions consequently allows us to demonstrate differences in the ways that pre-existing patterns of militarisation of the forests have been intensified under the “exceptional” conditions of lockdown.

The two cases we will discuss in the following sections can be summarised as follows:

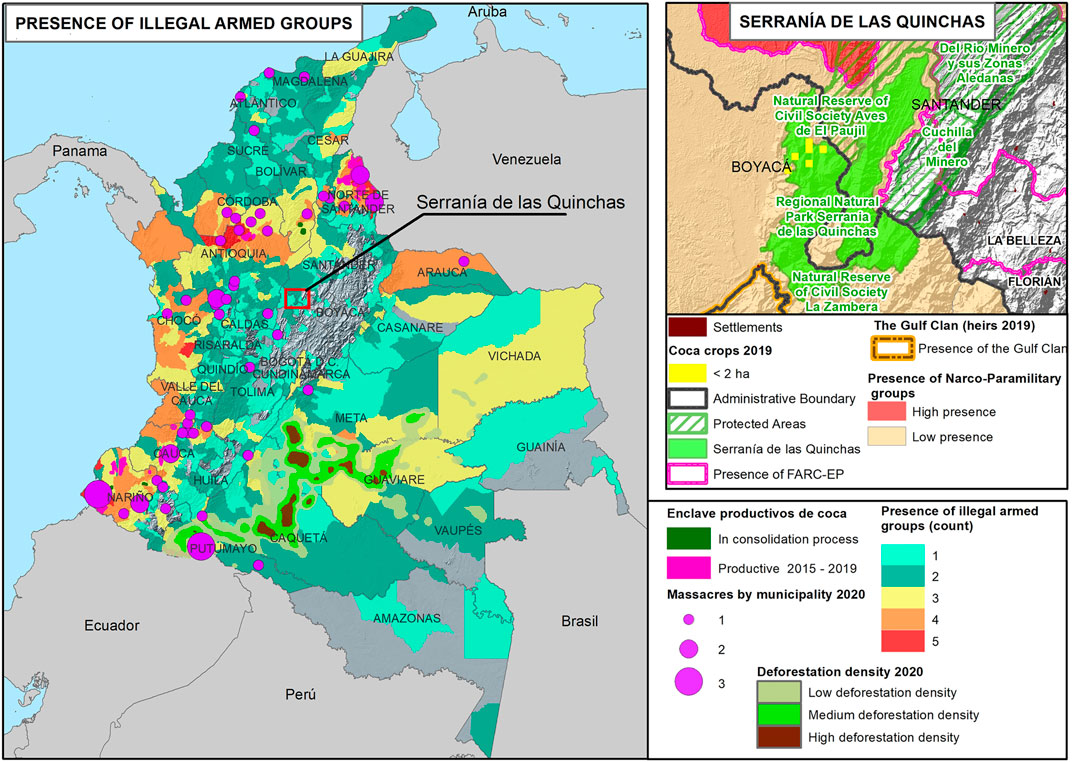

• Quinchas is a protected area located in the Inter-Andean Valley, formally constituted in 2008, which is administered by the governing body CorpoBoyacá.4,5 Although the area was zoned to protect vulnerable species, restrictions on access and lack of information on the new rules has led to increased poverty, disenfranchisement and conflict among rural communities there. The region has a long history of armed conflict and is associated with a high presence of competing paramilitary groups. Figure 1 illustrates key geographical features of this region. For example, we can observe the overlap between the operating zone of illegal groups and coca enclaves in this area, together with deforestation trends reported by IDEAM in the first half of 2020. According to IDEAM, deforestation rates in the Colombian Andes increased from 14% in 2018 (28,089 ha deforested) to 16% in 2019 (25,213 ha deforested), while in the first half of 2020 alone (January–June, coinciding with the COVID-19 lockdown measures) it shot up to 17.2% (January–March) and 28% (April–June) (IDEAM, 2021).

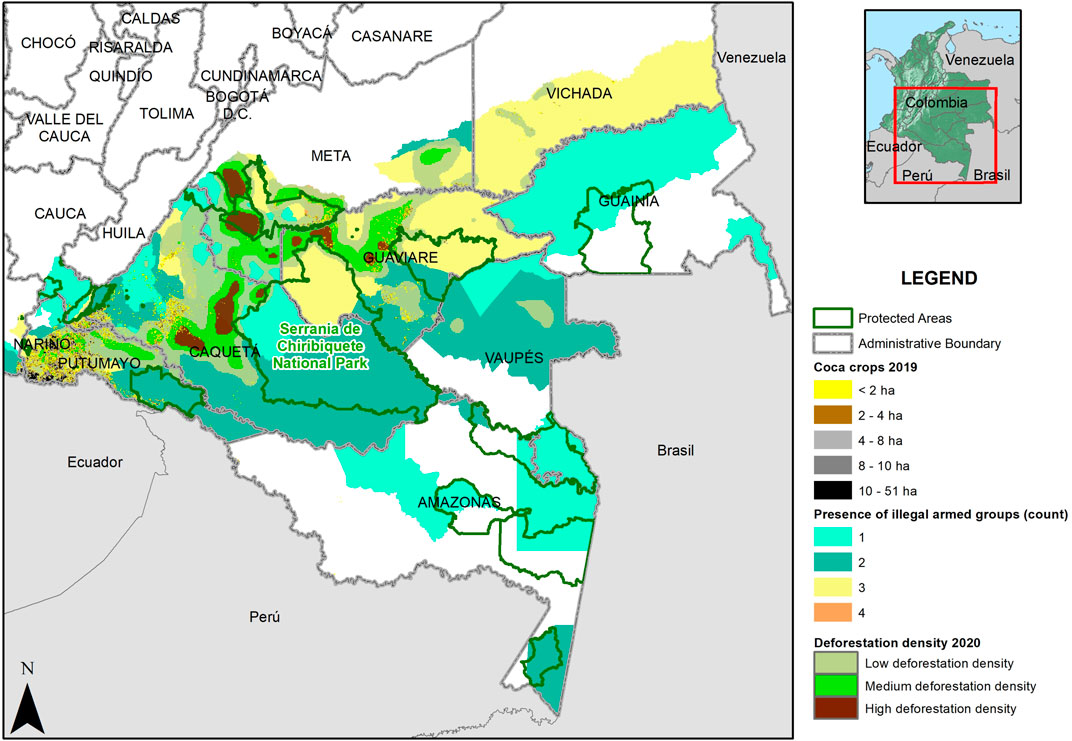

• The Colombian Amazon biome includes seven departments. In this article we concentrate on the Amazon belt (Caquetá, Guaviare, and Meta), a zone of historical armed confrontation, where there are many colonos seeking to obtain land on a rapidly expanding agricultural Frontier. In the context of increased international awareness of biodiversity loss and climate change in recent decades, the Amazon has become the centre of global intervention in militarised forest conservation. As Table 1 shows, in 2020, deforestation increased in the Amazon and Andes Biomes, coinciding with the period of restrictions imposed by the pandemic.

FIGURE 1. Map of location of the Serrania de las Quinchas in Colombia in the Andean Mountains. Produced by Alejandra Gomez (2020), commissioned by the authors5.

TABLE 1. Deforestation trends in Colombian in the Post-Agreement. Source: Global Forest Watch, 2021.

This table shows the deforestation trend in Colombia since the signing of the peace agreement with the FARC guerrilla in 2016 and its eventual disarmament. During 2020, the first year of the pandemic, deforestation increased notably, reversing the achievements made in 2019.

From the beginning of our interventions, the socio-cultural component of the project sought to enact a specifically decolonial ethos to our research methods, in keeping with the work of scholars like Mbembe, but also inspired by the work of Escobar (2007), Walsh (2015), and de Sousa Santos (2016). These scholars set out a way of doing social science research, including ethnography, from a perspective in which reciprocity, social networks, horizontality and seeking to strengthen capacities to address violence are central to producing knowledge. This is to say, all knowledge production is understood to be situated in relationships that are grounded in power relationships and configured in and through institutions that establish difference in advance. However, decolonial projects that are committed to becoming aware of the ongoing effects of (neo)colonial relationships, including in the academy and in research projects, and to transforming them through everyday conversations, interventions, and the creation of legacies that outlive projects. The decolonial approach involves not just observing and taking notes but noticing differences, asymmetries and devising forms of resistance in situ. Although in many ways the interventions that inform this paper were improvised and short-term, the collaborations began long before the conversations and have outlived them in the form of meetings, exchanges, and policy interventions. In this sense, our involvements also resonate with the ethos of feminist political ecologists, who have called repeatedly for “situated” researchers who do not see themselves as neutral or objective knowledge producers, but involved participants who affect and are affected by the situations they relate to (Elmhirst, 2015).

This positionality also affected the possibility of writing this paper, which unfolded through ongoing relationships and communications not originally designed into the research. Our research in Quinchas had two significant moments, the first prior to the COVID-19 outbreak in 2018–2019, when we generated a collaborative dynamic with local researchers from the region. We worked closely with four researchers in particular, who trained in qualitative research to become part of our team as well as to develop their own objectives, and together as a team we began to work on conceptualising a problematic of the territory based on initial interviews and historical readings of the territory. These researchers participated in a reading group with community researchers and students from our wider project and became an active part of our research team. Once the COVID-19 pandemic began, and we were prevented from returning to the field, these local researchers continued recording the situation first-hand in a second “research moment”, and began transmitting data and concerns to us regarding local military operations and other uncertainties virtually. We received via the messaging interface WhatsApp (which, in such rural areas with limited internet access, remained the most functional way to communicate under lockdown) videos, photos, audios, and text messages tracking the acts of violence on the part of the army that we will cover in this paper. This led to significant periods of unprecedented food insecurity in the community of Quinchas. During an early stage of the national lockdown, we supported our collaborators in an international fundraising campaign to provide short-term relief in the form of non-perishable food, masks and sanitising gel that would allow them to maintain the lockdown without being exposed to the violence of the army outside their homes. Meanwhile, these ongoing collaborations allowed us to develop the data that provides the backbone for this paper.

While it may seem that fundraising and research are and should be separate concerns, we suggest that they both emerge from the decolonial commitments that we have outlined above. The affirmative action, as we called it, generated political visibility in the Colombian media, so that the situation of remote rural communities like Quinchas became a national concern during the pandemic, in particular the case of the Indigenous communities in the Amazon, who were abandoned by state institutions, and who had to move into hiding in the forest to contain COVID-19 (Gaia Amazonas, 2021; Cumbre de Mujeres de la Cuenca Amazonica, 2021) Although the global pandemic affected our capacity to undertake our planned fieldwork, being committed to decolonial relationships demanded from us a modified way of working rather than a step back. This was especially the case in a context where it was clear that, being positioned in universities in the Global North, or in networks at the national and international level, were affordances that allowed us, at this moment in time, to work together to create new levels of political visibility in a situation that was changing very rapidly.

Our involvement with local researchers and then the “Affirmative Action” also increased the interaction and trust between the rural community of Quinchas and the wider research team: our communication increased, and we have continued to developing working relationships up until the time of writing. We have actively participated in local, regional and national forums to support policy change in conservation governance in consequence.

Our close focus on the developments in Quinchas also encouraged us to keep abreast of the changing situation elsewhere in Colombia. Through contacts in the national environmental offices of Colombia for sustainability and monitoring, including IDEAM (Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology, and Environmental Studies), we kept up to date with new deforestation hotspots and the deployment of the armed forces. Through existing activist and social movement contacts in the Andes and Amazon, we followed reports that disagreed with national reporting, especially human rights abuses and notices of the sudden arrival or departure of armed groups. Some of our existing networks enabling this work were created through our forest-based research, whereas others were created through our parallel investigations into environmental monitoring technologies, including drones.

Our contacts reported that in 2020, amid the pandemic, military operations increased. As also indicated by a key report on Artemisa’s military operation against deforestation (May 6, 2020), and information extracted from the General Command of the Military Forces and the National Police (MinDefensa, 2020), military operations against deforestation were mainly deployed in southwestern Colombia, the inter-Andean valleys and the Guaviare, Putumayo and Meta, where civilians associated with residual guerrilla groups were detained. Two hundred mobile military eradication groups were also deployed to eradicate illicit crops in the first half of 2020 in cooperation with the Security Force Assistance Brigade troops (SFAB) and in coordination with forces known as Hercules, Vulcano, Omega, and the Brigade against Drug-Trafficking. Operations were concentrated in the Inter-Andean Valleys. Military operations increased during March and April 2020, covering 160 municipalities, compared with the same months in 2019 when there were 87 (Garzón, 2020). However, such operations were unusually conducted as if counterinsurgent military operations, as was evident in the type of clothing and weaponry used (Arenas and Vargas, 2020). Additionally, they were accompanied by the more heavily-armed ESMAD (Mobile Anti-riot Squad) when confronting peasant protests. Meanwhile, paradoxically, although there was a greater number of more intense and heavily armed coca eradication operations in 2020, 6,500 fewer hectares of coca were actually eradicated compared to 2019 (17,300 compared to 23,800 in 2019) (Garzón, 2020).

To gain an overview of these patterns it is also important to understand the distribution of illegal armed groups and coca production in the two regions. Figure 1 shows, as purple dots, acts such as massacres of the civilian population in the Inter-Andean Valleys during the 2020 lockdown, as well as military operations for the eradication of coca production. Figure 2 shows that in the Amazon a significant number of illegal armed groups were present and deforestation higher.

FIGURE 2. Map of Colombia focusing on the Amazon Region, produced by Alejandra Gomez, commissioned by the authors.

In the next section we use our case studies and contextual historical analysis to demonstrate that pre-existing geographies of social difference, established historically via colonisation and decades of war, help explain the new patterns of militarisation in play. Although these patterns do not explain, on their own, rising deforestation rates, they help illuminate how and why zones of lawlessness/exceptional control have been configured in areas where deforestation was previously decreasing. Rather than perpetuating the narrative of armed forces being necessary to prevent deforestation, this change of focus helps us appreciate the ways that powers of exception are being used under lockdown to intensify militarisation in many conservation areas, while exempting the state from responsibility for environmental damage.

The forests of Quinchas are mainly inhabited by colonos: landless peasants who migrated to escape violence in other regions.6,7 Here, as in other inter-Andean valleys, counterinsurgency operations overlap with the war on drugs and environmental conservation agendas, with the state armed forces operating flexibly between these remits. This was evident during the 2020 lockdown, when the number of troops in the area increased dramatically, ostensibly to crack down on coca production, but also to regulate and contain local communities in other ways. From the perspective of a local female environmental activist from Quinchas, these moves are “highly opportunistic” and take ‘advantage of the fact that the peasants are locked down and thus do not have the usual channels of communication open to them, for example to claim the right to voluntary eradication programmes—a condition that was central to the peace agreements between the Colombian Government and the FARC-EP guerrillas. These armed interventions also have their own environmental impact—the forced eradication of coca crops involves the burning of agricultural land and forest where supplies and laboratories are identified. However, despite a military presence, deforestation due to illegal logging intensified during this period. We suggest that this is because the green militarisation already in play here shifted toward a necropolitical rationale. This is to say, the armed forces used the exceptional conditions of lockdown to carry out geopolitical objectives outside the purview of state law. Meanwhile, associated paramilitary groups, with longstanding territorial control, expanded their influence.

Green militarisation in such contexts describes how the logic of environmental protection has led to the proliferation of armed groups (legal, para-legal, and illegal armies) in conservation zones. We are not suggesting that all such groups are working together for similar ends. They may form temporary alliances to confront other groups, but they also often confront each other. Such groups are also configured differently in relation to the forest and its protection. The state’s armed forces are ostensibly involved in preventing illegal deforestation, via operations like Artemisa, though such concerns appear to be sidelined when they are undertaking coca eradication programmes. Meanwhile, some armed groups are explicitly engaged in coercing local colonos to clear areas of the forest for agriculture—a pattern that manifests in large square blocks of land, unlike the piecemeal agriculture associated with the colonos’ own subsistence practices. Other groups directly oppose or permit it in exchange for protection. Significantly, under lockdown, exceptional interventions into the coca trade have been emphasised, while forces have been removed from forest protection. Rule has taken on necropolitical qualities, with the armed forces of the state refusing to keep stating territorial rules, harassing local communities without accountability, and even carrying out assassinations (Ortega, 2020; WOLA, 2020).

In prioritizing forced coca eradication during lockdown, the Colombian government and its army reveal that, rather than lacking resources to police deforestation, these extraordinary conditions are providing an opportunity to intensify spatial control. As well as generating clashes with rural communities and permitting illegal deforestation to take place unchecked, this has resulted in the infringement of peasant civil rights and an increase in the number of social leaders murdered in the forests of the inter-Andean valleys, including Quinchas (Indepaz, 2020). Much of this military violence is taking place under the conditions of exceptionality associated with the pandemic—avoiding controversy and contestation by social organisations and defenders of human rights.

The way that Quinchas became a target for militarisation can be better understood through our earlier account of the historical situation of the colonos in the region. In Quinchas, few rural communities within the boundaries of the natural regional park have formal titles. The arrival of international conservation programmes, after the declaration of the park in 2008, only compounded ongoing insecurities as the new rules and zoning regulations were never properly explained. As community members recounted in our workshops, new legislation threatened to evict them from conservation areas, partly because infractions had taken place without full information about the new regime, and partly because some residential areas had been deemed “core zones” of the forest, where no one may live. Further, the establishment of new park borders created a vehicle for the introduction of military operations against deforestation in the Andean Forest that authorised the use of force. Conditions for exceptional rule were therefore in place before 2020, although these operated in keeping with a primarily biopolitical logic, focusing on managing species life in the forest and excluding or disciplining local communities by virtue of these operations. In this area long dominated by paramilitary and neo-paramilitary forces, however, people were also subject to periodical declarations of curfews, crackdowns on youth drug use by local gangs, and sanctions imposed by neo-paramilitaries. During lockdown, these two sets of exceptional measures were increasingly articulated together.

Governance also took a further necropolitical turn under lockdown conditions. An example of this took place in March 2020 in the small community of Otanche, when the army arrived to forcibly eradicate coca, burning ranches and peasant crops. Communities confronted the soldiers, who did not have the required biosafety equipment or provide legal guarantees (Aldianoticias, 2020). Already frightened by COVID-19, however, people submitted to the operation without having their concerns met. Meanwhile, with the continued support of the Colombian and U.S. governments, the Ministry of the Interior maintained that lockdown was an important moment for glyphosate spraying because there would be a reduced impact on humans (Forbes, 2020). Measures continued throughout 2020 in this way.

In the Amazon, peasants have also been largely interpellated as colonos: many communities arrive at the forest-agricultural Frontier as displaced people with the promise of a plot of land for cultivation and make their living through subsistence agriculture. Quinchas and the Amazon are in this sense connected by their historical constitution as zones for agricultural expansion shaped by social and armed conflicts. However, there are important differences. Colonos arrived in Quinchas during La Violencia, escaping from the violence and seeking state recognition and rights to land. Here the state promoted peasant colonisation and tried to regularise it through agrarian reform, but the process was only partially completed as an agrarian counter-reform was instigated by landowners and paramilitaries. Today, although colonos have been settled in Quinchas for several decades, they still do not have land tenure, which is why they continue to be defined as colonos. Meanwhile, although landless peasants in the Amazon also arrived due to forced displacement, the region has, over the last two decades, remained a central theatre of the internal armed conflict (PARES, 2018; 2020). This adds a distinctive dynamic to the operation of conservation governance, because in some sense, necropolitical rule has never ceased. The figure of the colono has been much more strongly associated with counterinsurgency operations in the Amazon than in Quinchas, especially as part of Plan Colombia I and II (1999–2002), and the war on drugs, through which the Colombian state recoded the guerrillas as narco-terrorists.

Colonos living in the Amazon belt have thus suffered persistent stigmatisation merely for inhabiting this disputed area. Environmental conservation, especially since the second government of Juan Manuel Santos (2014–2017), which gave the army a new role in specific, multi-stakeholder environmental projects, has continued to target colonos as a source of environmental deforestation. These projects have been adapted under Ivan Duque’s (2018-) more explicit focus on combining conservation with counterinsurgency, and environmental monitoring is increasingly blended with surveillance and control by the army. Operations like Artemisa are premised on the notion that colonos are intrinsically eco-destroyers and are indistinguishable from the illegal armed groups operating in the region (DeJusticia, 2020). This renders it practically impossible for peasants to appeal to the law to resist harassment by the army. Indeed, they are often codified, in state accounts, as part of the problem of illegal deforestation.

However, the environmental conservation efforts reshaping the region since 2008 according to biopolitical logics have also slowly changed the connotation of colonos. Environmental entities frequently stress the idea of colonos as “internal enemies” of the environment, who need to be quelled. This discourse, shaped by biopolitical concerns with protecting species life, has created a loop in which the necropolitical agenda of the Colombian state can be activated. This loop takes an unexpected turn, creating state arguments that connect deforestation, coca cultivation, counterinsurgency, and the state’s struggle against deforestation that go back and forward targeting the colonos as the old-new enemy to control, monitor and repress. This means that ultimately the state can claim that in controlling the colonos, they are saving the environment and reducing cocaine production (UNODC, 2019). A knock-on effect may be that the authority of illegal armed groups is paradoxically increased, enabling further rounds of unlawful deforestation.

Significantly, in contrast with Quinchas, in the Amazon the military forces involved in forest protection operations were largely redeployed elsewhere. In line with media narratives, this may be partially attributed to the need to ensure lockdown compliance in the principal cities. However, what the new situation also revealed was how many of the institutions and experts involved in maintaining environmental conservation practices were already based far outside these areas. Due in part to the narrative that the Amazonian colonos are in league with dangerous illegal groups and need controlling from outside, peasant communities have been actively abandoned by the state, a situation exacerbated when the functionaries who usually monitor conservation stopped coming due to lockdown. With the army redeployed and these functionaries absent, the state’s precarious hold of illegal logging fell apart. In parts of the Colombian Amazon, where the state’s presence was already limited, armed groups and criminal networks, described by local environmental organisations as “land grabbers” and “mafias come bosque” [forest-devouring mafias] have since lockdown strengthened their territorial control and expanded their deforestation activities (FCDS, 2020a). The underlying motivation of such groups seems be to profit from deforestation, eg. via cattle ranching, and local peasants are employed—often under duress—to clear vast tracts of forest to this end (Clerici et al., 2020; Prem et al., 2020). The landless peasants—stigmatised, abused, and unrecognised by state institutions—are consequently trapped by illegal timber economies and may be forced to work in them due to the lack of other subsistence possibilities. This has given way to the fresh empowerment of illegal armed groups to enforce a local rule of law, reviving conditions of necropolitical securitisation.

In both Quinchas and the Amazon, new rounds of green militarisation can therefore be identified under lockdown conditions. In the Inter-Andean Valley, where Quinchas is located, the presence of the state military is greater, but the emphasis on coca eradication has increased conflict and enabled exceptional intervention measures. Deforestation has increased, maybe partly due to the eradication measures, as well as to the weakening of conservation institutions vis-à-vis paramilitary forces and other illegal groups. In the Amazon, the state military has been suddenly withdrawn, and the territory is now dominated by dissidents and paramilitaries associated with cocaine, logging, and illegal mining. Although this may have directly contributed to the increased deforestation, it is important to note that processes of active state abandonment and the configuration of alternative, para-state authorities are also in play.

In both Quinchas and the Amazon, therefore, we can observe how the existing biopolitical logic of international conservation has been used to establish necropolitical loops in Colombia during the exceptional circumstances of COVID-19. In both cases, the use of biopolitical practices to monitor biodiverse forested areas is associated with longer histories of international environmental conservation, whose operations are structured to preserve the life of forests and biodiversity as a moral imperative. This logic legitimises interventions that are seen to reduce threats on species life, such as illegal timber cutting and poaching. Over time, it also frames actors already understood to be “risky” as potential eco-destroyers. In ordinary times, such interventions take place through the rule of law, although we have increasingly seen the militarisation of conservation through operations like Artemisa and the forced eradication of coca crops. Meanwhile, during the COVID-19 lockdown, discourses of the war on drugs were reactivated, enabling properly necropolitical practices, such as forced cocaine eradication operations and harassment of the civilian population.

In Quinchas, the biopolitical rationale nevertheless remains dominant through such processes, with the war on drugs being used as a premise to secure and protect some lives against the active threats posed by others. In the Amazon, meanwhile, a pivotal site of interventions in environmental conservation—and thereby biopolitics—the necropolitical rationale has become dominant. Here, illegal armed groups now dominate the forests abandoned by the Colombian state and its institutions, exposing colonos, indigenous people and forests to new levels of violence. The necropolitical regime consists of actively letting people die and watching the inhabitants suffer from a distance, at the hands of para-state actors. The help requested by colonos and indigenous people has been ignored by state entities, exposing their vulnerability, and even being recoded as a sign of the irresponsibility of peasant inhabitants. Only recently are national and international institutions returning to take stock of the losses due to this active abandonment during lockdown in the first wave of COVID-19 in Colombia.

It is also important to note that this trend toward the intensification of military presence in forests and necropolitical control has not been consistent across Colombia’s forests, even during lockdown. While military operations were being enacted in the inter-Andean valleys and active state abandonment was being entrenched in the Amazon, something very different was happening in the forested areas of the high Andean mountains of the Chingaza biological corridor, another location where we conducted interdisciplinary fieldwork. In Chingaza, biosafety equipment was distributed, as well as information about protective measures for quarantine, coordinated by campesinos and local state authorities. The local authorities and communities of the highlands in the central Andes were also the fastest to act to counter the expansion of the pandemic in general (El Espectador, 2020). Regional borders were closed, lockdown was enforced, and action was taken to prevent the spread of the virus, along with the distribution of food supplies (personal communication with inhabitants from Monquentiva). In the highland mountains of Cundinamarca and Boyacá, meanwhile, the closure of all National Parks seems to have provoked an unexpected passive ecological restoration. Here, the state was involved with the inhabitants of these forests, focusing on the prevention of harm, and the operations were not militaristic.

What is clear, therefore, is firstly, that the state does not operate the same way in all the forests of Colombia, and secondly, that the spatial imaginaries to which the deployment of armies to support “conservation” conforms are loaded with stereotypes and stigmatizing gestures that manifest ongoing colonial power relations. In other words, they are not far from Taussig’s topographies of highland and lowland morality that codify “good” campesinos in the high Andes and differentiate them from colonos, or potential nature destroyers, in the lowlands. These spatial imaginaries, layered in turn with associations conferred by the national armed conflict, come to legitimise exceptional powers and actions of the armed forces, in the name of conservation for the good of all. In this sense, the additional sites presented in this article provided a useful contrast to the two regions under discussion in this paper, helping us to see how the historical moral geography traced by Taussig and others is perpetuated today in the way that the state is present at certain sites as part of the elaboration of biopolitical conservation, while others are passively abandoned or securitised with excessive force—sometimes through the insertion of necropolitical “loops” of exceptional rule.

We observed that these colonially-grounded differences also manifested in the varied expressions of survival of the forest in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and the violence of legal and illegal armies. Among the paramo communities in the high Andes, lockdown conditions amplified existing capacities for self-organisation and endurance. Small communities were able to survive relative disconnection from cities and provide food, medicine, water, and mutual care for their inhabitants. This was also the response of many Amazonian Indigenous communities, in the face of the explicit abandonment of the Colombian state, albeit under conditions of relative isolation and poverty (Gaia Amazonas, 2021).

However, in Quinchas, facing similar issues like in the Amazon, this was not a possible option. The internal social networks and capacities were not in place, and the regulatory frameworks that might have enabled vibrant economic livelihoods under the new ecological frameworks of the Natural Park had never been fully explained to local people. What did happen, on the other hand, was an increase of external connections and relationships, for example with networks of researchers, like us, so that allowed local people to denounce acts of violence and to receive material aid. The peasants of Quinchas, from being sceptical toward social organization and cooperation, have moved, through the pandemic and interactions with our research group, toward creating conditions of mutual support, hope and encouragement, and have increased social organization for food autonomy and community-led conservation of the forest.

These expressions of self-care and survival suggest an “excess” to militarised conservation, or something that does not reduce to thethe violence of the armed groups and the abandonment of the state. Even as the necropolitical conditions we have traced are active and expanding, it is important to notice that they do not saturate the possibilities for social and collective life, even in areas currently codified as “risky” or in need of containment by the state. It is a crucial part of a decolonial and feminist political ecology commitment to identify and expand the possibilities for such forms of collective care and endurance that are emerging through and despite (neo)colonial power relations. Marisol de la Cadena, 2015 elaborates on this idea of “excess” (2015: 34) as a space of relationality that partially escapes the modern-developmentalist-capitalist framing–resonating with notions of the “otherwise” as discussed by decolonial thinkers like Arturo Escobar (2007) and Catherine Walsh (2015). Excess is performed at ontological limits—the limits of what it is possible to see and say about the world according to current discourses and forms of legitimacy. The COVID-19 pandemic opened a fresh space of limits, which enabled the Colombian state, on the one hand, to operate under, and declare, new conditions of exceptionality. On the other hand, it also renders possible new kinds of relationality and care that escape and exceed the state, modernity and coloniality, whether temporarily or with enduring possibility.

This analysis of the dynamics of conflict in Colombia therefore highlights the fractured relationship against colonos. Such geographies persist in the ways that environments are governed and policed today, in ways that are perpetually transforming, but which continue to reproduce regional stereotypes and the forms of governance related with them. The insertion of necropolitical loops into conservation practices today is partly the result of the ways that the figure of the colono has been historically configured in Quinchas and the Amazon, where rural communities are associated with violence, cocaine production and deforestation. This legitimises continuous intervention on the part of the state, rendering green militarisation part of everyday life in forest communities. Against the idea that moving armed forces out of forests on its own makes deforestation more likely, this history of interventions is part of the story of deforestation. It is also a major factor in exposing highly vulnerable rural communities to increased levels of risk and harm.

In this article we have observed how the general sharp uptick in rates of deforestation identified in Colombia in 2020 reveals important dynamics of green militarisation and its potential future directions. We have linked current patterns of militarisation with the histories of: 1) interpellating rural subjects as colonos, interwoven with colonial imaginaries of the rural poor; 2) geographies of international conservation, whose biopolitical logics have been exploited to illuminate particular subjects as potential eco-threats; 3) histories of necropolitical practice as grounded in the formation of paramilitary forces and the justification of extraordinary powers for the state armed forces, linked with decades of conflict in Colombia; and 4) discourses of the war on drugs, which strengthen militaristic rights to intervene in biopolitical risks via geopolitical imperatives. Together, these factors help explain why, in Quinchas, both deforestation rates state armed forces have increased during lockdown; why in the Amazon the army and international actors have been largely absent during the first months of lockdown, but the spatial authority of illegal armed groups has increased, and why in some highland areas of the Andes like Monquentiva, reduced rates of deforestation have continued.

This account contributes to the interdisciplinary field of political ecology by showing how the biopolitical dimensions of international conversation in the Global South, which are well understood, may be manipulated to insert “necropolitical loops” during extraordinary circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In Colombia, where necropolitical practices have a long history, green militarisation associated with forest conservation projects has fostered conditions where they can, at any moment, be reintroduced. This is particularly worrisome because extravagant reporting tends to make rural communities’ part of the problem of sudden increases in deforestation in these regions, rather than clarifying the extent to which they are forced to submit under exceptional conditions by illegal armed groups. Further, the moral agenda of protecting life in both international conservation and the war on drugs, tends to obscure how new zones of exceptionality are being established, where rural communities are systematically exposed to harm in the form of fumigation, and the violent actions of (legal and illegal) armed groups supposedly acting to contain potential eco-destroyers. In making this argument we have also advanced understanding of the dialogue between biopolitical and necropolitical regimes. These we have framed not as two opposing modes of governing, but as two processes whose interrelation takes shape in specific socio-historical and geographical contexts, forming liminal spaces (Chung, 2020) in which they articulate. As we have shown through the cases of Quinchas and the Amazon, they articulate with one another in discursive practices and in practices that organise these territories in moments of perceived crisis, in which international publics accept military interventions uncritically.

Through our case studies we have also suggested that the specific geographies of necropolitical practices in Colombia have been shaped by longer histories, including the moral topographies analysed by Taussig in association with colonial narratives and practices. The hot, tropical lowlands have been consistently viewed as places of potential violence, chaos, and disorder, needing to be brought under control, while the highlands have been coded as places of peasant organisation and tenacity. These geographies still inform the configuration of conservation governance according to biopolitical logics that determine which life-bodies are worth caring for, and which are disposable or marginal to these agendas.

What we are witnessing as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds is not new, but provides insight into where and how biopolitical regimes are being pushed across the threshold into necropolitical ones. The biopolitical affordances of pandemics already prepare the ground for such transformations by rendering particular bodies as objects for protection, and by mobilising the exceptional powers of states to intervene legitimately on behalf of a threatened population. In such moments, states abandon and stigmatise bodies like the elderly, those with chronic diseases, people in jails, people without health infrastructure and the poor. In dialogue with state agendas to control and weaken perceived insurgents, supported by US geopolitical interventions in Colombia, such hierarchies working on bodies can be seen to extend into necropolitical processes that systematically abandon and expose entire communities to harm, suspicion, surveillance, and violence.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Professor Rachel Flecker Chair of the Research Ethics Committee, School of Geographical Sciences. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This project has received funding from NERC-UK through the interdisciplinary research project: BioResilience: Biodiversity resilience and ecosystem services in post-conflict socio-ecological systems in Colombia, led by the University of Exeter and the University of Bristol in collaboration with Colciencias-Colombia. Project Reference NE/R017980/1.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1Personal conversation with Patricia Gualinga, Indigenous leader of an Amazonian group in Ecuador

2“BioResilience: Biodiversity resilience and ecosystem services in post-conflict socio-ecological systems” (2019–2021) was an interdisciplinary project funded by a UK NERC-AHRC cross-council call under the Newton-Caldas Colombia-Bio programme (NE/R017980/1). The project (PI: Ted Felpausch) set out to examine the long-term resilience of Colombian forest ecosystems to environmental and climatic changes and to improve understanding of the future implications of forest degradation for Colombian society

3We interviewed different population groups divided by professions or economic activity, gender and geographic location within the natural park. The workshops included socialisation activities, prior consultation, training and focus groups in five villages of the Serranía de las Quinchas in the municipality of Puerto Boyacá.

4Our analysis of the Amazon case must be understood as more speculative as it leans heavily on emergent satellite data and the analysis developed by environmental activists and organisations. We wanted to develop this contrast, however, because as media reports and the testimony of activists have made clear, the Amazon is a major arena of green militarisation that is being reactivated in significant ways in this moment. It is also difficult to talk about the Colombian forest without talking about the Amazon: the Andean forest (17%) and the Amazon forest (66%) form a significant part of Colombia’s biodiversity, jointly forming 83% of Colombia’s forests (IDEAM, 2021).

5CorpoBoyacá is a decentralised autonomous institution, which controls the administration of regional natural resources for the Department of Boyacá in Colombia.

6The maps presented in this article were produced through a compilation of different sources including UNODC, SIMCI, PARES, and REDEPAZ. Thematic layers (information about coca, actors of armed conflict and deforestation) were subsequently generated and laid over the shape format of the official National Park data.

7The Middle Magdalena Medio, where Quinchas is located, was governed under a permanent state of exception from 1952 to 1994, a condition declared by the government of Laureano Gomez. Several repressive legal instruments were put in place during the conflict, such as the Organic Statute of National Defence (1965), The National Security Statute (1978) and the Special Public Order Jurisdiction (1978). The latter determined that Puerto Boyacá would become a Zone of Special Control.

Adams, W. M., and Hutton, J. (2007). People, Parks and Poverty: Political Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation. Conservation Soc. 5, 147–183.

Aldianoticias (2020). Destruyen más de 16 mil plantas de coca en Otanche. Last. Boyacá. [online]. Available at: https://aldianoticias.com.co/blog/boyaca/chiquinquira/destruyen-mas-de-16-mil-plantas-de-coca-en-otanche-boyaca/(Accessed November 1, 2020).