95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 10 June 2021

Sec. Environment, Politics and Society

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2021.636422

This article is part of the Research Topic Political Ecologies of COVID-19 View all 11 articles

How a country responds to a rupture such as the COVID-19 pandemic can be revelatory of its governance. Governance entails not only the exercise but also the constitution of authority. The pandemic response thus presents a real-world disruption to verify or problematize some truisms about national governance and produce novel comparisons and insights. We present a comparative analysis across four established democratic nation-states. First, we identify concerns of relevance for national pandemic responses and map them to state characteristics. Next, we conduct thematic analyses of recent ruptures in India, the United States, Sweden and Norway, to form a baseline of truisms about governance responses to frontier moments such as this pandemic, and hypothesize their relative propensities across the concerns. We then compile comparative data on emergent pandemic responses during the first 90 days of respective, temporally proximate outbreaks. This combination enables us to link response characteristics to national propensities across the relevant concerns. We identify similarities and differences between what the pandemic responses reveal and the truisms of scholarship about the four countries state characteristics. We argue that ruptures in democratic governance contexts embody temporally discontiguous and country-specific patterns. They are conjunctures of particular possibilities for bounded reconfiguration. Such reconfiguration can intensify or shift the course of what the state is becoming. We argue that in our cases it accelerates shifts to authoritarianism (India and the United States), raises stark questions of national identity (Norway and Sweden) and underscores tensions between the reemergence of welfare states and the global project of neoliberalism. By revealing what sort of rules show resurgence across ruptures, our comparative analysis deepens a timely understanding of punctuated politics of reconfiguration of authority.

Considerable associated costs to life and wellbeing notwithstanding, every crisis is an opportunity. What each country makes of a rupture such as the COVID-19 pandemic shows us something about the stability of existing state formations. Lund (2016: 1199) argues that moments of rupture “allow us to see that rights do not simply flow from authority but also constitute it.” Governance thus entails not only the exercise of authority (over a resource, such as a territory) but also the constitution of authority, an act of state formation. In this sense, the pandemic response presents a real-world disruption to verify or problematize some truisms about national governance contexts. These truisms are broad characteristics undergirded by a wealth of empirical research on a range of problems in diverse contexts. In a chapter entitled “Principles true in every country,” Mitchell (2002: 70) characterizes the fallout of the cholera pandemic in the late 19th century in terms of the reconfiguration of debt and property by institutions with state quality that had “powers of exception.” These institutions can extend to non-state actors in “areas of limited statehood” (Risse, 2011), which is particularly apt during a rupture such as a pandemic where nation-states do not necessarily have the capacity to respond on their own.

Thus—despite various caveats we mention below—studying the real-world disruption of the “Coronavirus disease 2019” (COVID-19) response in the form of pandemic measures undertaken by select countries can produce several novel comparisons and insights. The truisms drawn from scholarship on rupture in specific nation-state contexts help us hypothesize the sort of things to look for; the outcomes speak back to the extent that such truisms hold true or are worth revising in light of any new knowledge. We ask: How consistent are insights on national responses to ruptures, drawn from COVID-19 pandemic responses, with existing contextual scholarship on ruptures? Drawing on Rasmussen and Lund (2018: 393), we understand rupture as institutional orders during “frontier moments.” These are “particularly intense conjunctures of crisis which suspend existing order [where] … the economic value of current activities is zeroed out, and the possibility of recognition as citizens is withdrawn or redefined” (ibid.). To these authors, such moments inevitably cohere with re-territorialization, where authority is reconfigured in a manner that relates to “particular institutional, legal, and economic conditions rather than to the spatial expansion of civilization” (ibid.). As Lund (2016: 1202) evocatively states, ruptures are “open moments” when opportunities and risks multiply, “when the scope of outcomes widens, and when new structural scaffolding is erected.” Accordingly, our enquiry foregrounds emergent non-linearity in the progression of state quality in the ruptured state contexts that we study during this COVID-19 frontier moment.

Political ecologists have been long interested in the nature and workings of the state and the dynamics of its reconfiguration, and in ever-ongoing re-territorialization processes. Scott. (1998) notes that narrow metricization of real-world complexity through calculative logics enables the state to multiply and strategically mobilize its authority. Li. (2007) delineates the dynamics through which states intervene in human lives in a purported bid to improve them. Furthermore, Agrawal. (2005) argues that over time state interventions shape human subjectivity itself to better suit the purposes of the state. Thus, the modalities of governance and popular perceptions of state quality are closely bound up with the impact of state interventions on subjects, e.g. through particular configurations of resource allocation and the manner in which they are normalised.

Robbins. (2008) identifies three key strains in how political ecologists depict state characteristics: the state tends toward ecological simplification; it governs through networks that reconstitute socio-ecological relations; and it institutionalizes environmental knowledge through erasure, creation and reproduction. While he takes a more fixed view of the state than Rasmussen and Lund. (2018), his review shares their concern with how the state is simultaneously a product and driver of territorialization. He sums up that the role of the state combines territorial strategies, political capabilities and an epistemological system as an effect of power at multiple scales (Robbins, 2008: 215). We approach the current rupture—the outbreak of a global pandemic with emergent state responses—as an “open moment” to study state quality through heightened forms of these dynamics of control over territory and resources, political authority, knowledge and expertise.

We proceed as follows. First, we identify concerns of relevance for national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic based on our reading of widespread coverage of the global pandemic response, and map them on to key nation-state characteristics (Research Design and Hypothesis). Second, we present thematic country analyses of recent ruptures in four national contexts–India, United States, Sweden and Norway–to provide a baseline of sorts for the truisms about each country’s response to frontier moments such as this pandemic, and hypothesize the relative propensities of the four countries across the relevant concerns (Ruptures and national propensities). Third, we compile comparative emerging data on the pandemic responses in these four countries during the first 90 days of respective, temporally proximate outbreaks (Empirical evidence by country case and by concern). Since comprehensiveness is not a meaningful present possibility, we include data with high certainty, and analytically characterize less ascertainable aspects in our timeline of the four pandemic responses. Fourth, we link response characteristics to national propensities across the relevant concerns to make claims about what this rupture reveals (Discussion), and then close with the Conclusion.

This exercise enables us to identify similarities and differences between what the pandemic responses reveal and the truisms of extant contextual scholarship on the four countries. We do not focus on making claims about the effectiveness of particular responses, as the timing would be premature for robust analysis and it is not our specialty. We rather argue that ruptures in democratic governance contexts embody temporally discontiguous and country-specific patterns. By definition, these depart from business-as-usual practices in a country, but they are conjunctures of particular possibilities for bounded reconfiguration. If we view the state as something that is always in the making (à la Lund, 2016), then such reconfiguration can intensify or shift the course of what the state is becoming. It can create the conditions for emergent national identities to concretize. We are interested in using this rupture to gain insight into the changing nature of the state in our country cases. Through this comparative analysis, we draw out lessons from the non-linear reconfigurations of authority that are being contested and constituted during the ongoing pandemic in our case contexts.

We have selected four country cases for comparative analysis: India, United States, Sweden and Norway. They are all established democracies, but display variation in terms of political history, levels of democratic consolidation, wealth and human development, as well as in responses to COVID-19. Our scope is limited to democracies, wherein popular legitimacy is formally necessitated for major shifts in governance decisions, thus we do not feature a case of an authoritarian state, but we do attend to authoritarianism within our cases. Norway and Sweden are small countries, and while both are instantiations of the “Scandinavian Model” of democracy, they have seen very different responses to COVID-19. The Scandinavian Model refers to a broadly social democratic form of governance with a strong welfare state combined with capitalist features, notably a commitment to free market principles for trade (Kettunen, 2011). India and the United States are large and culturally heterogeneous democracies, but share four features that define governance in both countries during the study period: populism, nationalism, authoritarianism and majoritarianism.1 They also feature great sub-national variation that we note but cannot address within the study scope.

In this section, we first identify concerns of relevance to COVID-19 pandemic responses. Then, we transpose them into generic state characteristics that link directly with the nature of authority. This is the framework with which we organize our thematic analyses of the four selected countries, to hypothesize their propensities on these characteristics during frontier moments of rupture. These hypotheses are tested in our empirical findings from the pandemic response, adopting an abductive approach where we focus primarily on two characteristics per country pairing to maximize analytical import given our initially hypothesized sense of national propensities. We thus aim to analyze tendencies related to state characteristics in the cases where extant scholarship suggests we are most likely to find them, without drawing premature conclusions on the nature of these tendencies. This affords us scope to confirm or contradict existing truisms by analyzing a rupture. The empirical analysis sets up the basis for our discussion of rupture and state re-territorialization in relation to the country cases, and the conclusion offers reflections on the implications of our analysis for political ecology scholarship.

Thus, in this section, we undertake two tasks. The first is to identify concerns that relate to global pandemic responses. The second is to transpose them into generic state characteristics. Given the specificities of national contexts, the latter is necessarily reductive, yet nonetheless essential to enable a comparative analysis that we argue—similar to Adger et al. (2001) on global environmental discourse and more recently Sovacool. (2021) on climate mitigation—offers considerable value for a political ecology understanding of governance during ruptures.

During January-May 2020, and especially from March 2020 onwards, global pandemic responses received ample media coverage to discern some key patterns across countries. These feature some particularities related to COVID-19 characteristics, but are largely similar to generic pandemic measures that aim to “flatten the curve”. The generic principles include slowing the virus transmission rate, r, so that it is below 1 (r = 1 corresponds to one transmission per infected person) and declines, in order to limit viral reproduction within medical treatment capacity and to minimize the economic fallout of pandemic measures on society. The particular strategies include washing hands, using sanitisers and facemasks, maintaining a physical distance of 1–2 m or more from others, and limiting gatherings to small groups.

Our reading of global coverage identifies four concerns that feature in all immediate and short-term pandemic responses: 1) fiscal measures and beneficiaries; 2) mobility restrictions; 3) stockpiling and distribution of medical equipment; and 4) extent of testing (infection and mortality rates, and relative to national population), until such time as treatments and/or vaccines can be developed, tested and widely deployed. These are defined in Table 1. We see mobility restrictions as tightly linked with employment concerns, and focus on the former since this enables us to identify fine-grained evidence for the three-month study period, which is unavailable in terms of short-term employment variability statistics. The four concerns are closely linked with political ecology concerns of control over territory and resources, political authority, knowledge and expertise.

Each of the four concerns above coheres with a generic state characteristic that is linked to state quality during a rupture. Many indices of state characteristics exist focused on relevant aspects: for instance, Freedom House’s index of political rights and civil liberties, on whose 7-point “freedom rating” scale all four case countries fell under the “free” range of 1–2.5 pre-pandemic (Norway and Sweden most at 1, the United States less at 1.5, and India less at 2.5) (House, 2018).2O'Connor et al. (2019) draw on work by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to discuss the state in terms of citizen engagement, transparency, accountability and integrity, and show that these factors correspond in the short term with better quality public services and in the long term with the quality of democracy, inclusive growth, trust in government and the rule of law. While a comprehensive listing of such indices is beyond our current scope, the point is that there is some degree of consensus on varying national propensities on specific state characteristics, with clear implications for resource access and equity.

In Table 2, we map the four pandemic-related concerns defined above on to these four respective state characteristics: 1) each country has a degree of predisposition to elite capture of political and economic decision-making functions; 2) each country has a degree of tolerance for political leaders to act in an authoritarian manner at odds with democracy to meet urgent needs; 3) each country has a degree of commitment to affirmative action to secure the interests of vulnerable population categories; and 4) each country has a certain degree of trust in experts. These choices are fit-to-purpose based on our interest in understanding emergent changes in state quality during a rupture. They are not exhaustive, but do capture aspects of the state qualities that Robbins. (2008) synthesizes: territorial strategies (elite capture and affirmative action), political capabilities (tolerance to authoritarian measures) and an epistemological system (degree of trust in expertise).

To establish four hypotheses, each linked with one of these generic state characteristics for our case countries, we present thematic country analyses based on secondary data in Ruptures and national propensities. Each hypothesis takes the form of an internal ranking (1–4) representing the lowest to highest propensity for a characteristic by our selected countries. These are not based on a retrospective reading of country-specific developments during the pandemic, but solely on a review of literature on the linked state characteristics for each country context. We draw on research about moments of rupture as much as possible in our literature review; however, this is available to quite varying extents across the four countries and for different kinds of ruptures that have limited relevance to the particular rupture that the COVID-19 pandemic and various responses represent. While for the sake of clarity and conciseness we use relatively broad characterisations below to set up our analysis, we are aware that these characteristics are debated, and indicate through caveats that we hold claims tentatively. Indeed, the point of our analysis is to not take these claims at face value, but to put them to the test in terms of how they bear out during the rupture of COVID-19 as seen in initial national responses.

Our thematic country analyses focused on the key contextual aspects of the four countries in relation to recent ruptures, which we understand as “open” or “frontier” moments in the wake of diverse crises (Lund, 2016; Rasmussen and Lund, 2018). Here, we present a pointed overview for each country case, to provide a baseline for the aspects most germane to our study. For India and the United States, we are particularly interested in aspects related to elite capture and authoritarianism, whereas for Sweden and Norway, we accord attention to aspects of affirmative action and trust in experts. Both choices are based on traits reflected in extant scholarship, allowing us to maximize analytical import from our study. We then compare this scholarship to offer comparative overall assessments in Table 3 and populate the hypotheses in Table 4 at the end of this section.

The postcolonial Indian state has exhibited a strong (but now weakly repackaged) rhetorical commitment to pro-poor policies and affirmative action (see Deshpande et al., 2019 for a nuanced discussion), coupled with a high acceptance of the state reposing authority in experts. At the current conjuncture, however, the Indian state may be described as increasingly centralized with a strong propensity for authoritarian populist forms of governance (Chacko, 2018), coupled with a relatively high degree of elite capture.

Two ruptures in particular have contributed to this development. The authoritarian populist turn commenced from the late 1960s. Pressured by social groups marginalized by the postcolonial developmentalist project, the long-ruling Congress party abandoned its commitment to liberal principles in favour of a populist, pro-poor reform agenda that boldly promised to “abolish poverty”. This was coupled with the violent suppression of insurgencies and the systematic building of a large security state with more than a dozen different paramilitary services (Hansen, 2019). This particular rupture culminated in a brief period of Emergency rule during 1975–77, with a subsequent return to democratic elections.

The second rupture reduced centralized state control over the economy via policies of liberalization from the mid-1980s onwards. The state gradually facilitated the expansion of capitalist accumulation in newly opened economic sectors. This neoliberal turn reflects the rise of the capitalist class within India’s dominant class coalition, and an intimate relationship between the state and big business (Kohli, 2012). The current charismatic Prime Minister Modi—in power since 2014—is enthusiastically endorsed by prominent members of the Indian capitalist class, and his successful welding of neoliberal economics, authoritarian populism, and aggressive Hindu majoritarian politics is becoming hegemonic (Kaur, 2020). The past decade has in this manner seen a coalescing of centralized political authority, personalistic rule, and attempts to circumvent civil liberties and the rule of law in the name of popular majorities (Chatterji et al., 2019).

The prioritization of capitalist growth is legitimated with rhetorical references to a vaguely defined notion of “development”, but without clear plans for redistribution. This has exacerbated already high social inequality and wealth concentration among the country’s economic elite (Crabtree, 2018). At the same time, surveys document declining support for democracy among the electorate. The 2017 Pew report concluded that support for autocratic rule is higher than in any other nation surveyed. More than half of the Indians surveyed would support governing by the military, and an even larger proportion supported government by experts rather than elected officials (Chatterji et al., 2019, p. 7). As recent elections show, voters are comfortable centralizing political power in a strong leader (Sircar, 2020), representing a clear shift toward authoritarian rule in the longest functioning democracy of the Global South.

The United States presents itself as a bastion of liberal democracy, in which the state secures individual liberties, equality, and the rights of minority groups, while simultaneously incarcerating more people than any other country, with steep increases since the 1980s and the privatization of prisons (Story, 2019). Commitments to affirmative action and trust in experts have long co-existed in adversarial entanglement with white supremacist tendencies and the “capitalist-evangelical assemblage” (Connolly, 2005, p. 870). Three recent ruptures stand out to us as turning points with salience for susceptibility to elite capture and authoritarianism: the World Trade Center attacks of 2001, the 2008 financial crisis, and the 2016 election of a populist authoritarian.

The World Trade Center attack led to a series of unconstitutional measures justified by the ensuing War on Terror (Redfield, 2009). One of these, The Patriot Act, followed the trajectory of political repression instigated by the illegal “counter-intelligence program” (where the Federal Bureau of Investigation infiltrated domestic political organisations during the 1950s–60s). The subsequent systematic policing of political dissents surfaced deep undemocratic tendencies (Churchill, 2004).

One of the hallmarks of the American dream has been a strong middle class and a perceived high degree of upward social mobility; aspects that have eroded over time (Putnam, 2016). Following the 2008 financial crisis, the bank bailouts represented an unprecedented transfer of wealth from the public to the private sector, which exemplifies elite capture. To say that wealth inequality has increased barely captures the fall from grace embodied by the new precariat since this rupture (see Milkman, 2017 for detailed treatment). Meanwhile, in the judicial branch, the 2010 Supreme Court decision in Citizens United vs. the Federal Election Commission solidified the precedent for corporate personhood, effectively establishing money as free speech (cf. Klumpp et al., 2016; Greenhouse, 2018). Thereafter, corporations could openly spend unlimited amounts in advertising and donations for political campaigns, which begs the question of who elected officials ultimately represent (Chomsky, 2017). The influence of money in US politics compromised the political left’s ability to counteract neoliberalism and elite capture (Karl, 2019).

In many ways, the presidential election of 2016 was a referendum on American values. By criticizing the international and unilateral institutions it helped to create and declaring “America First”, President Trump abandoned the long tradition of claiming to lead the free world. This rupture has consolidated the use of media for surveillance capitalism and political polarization rather than public awareness (Zuboff, 2019) and shown the susceptibility of democratic systems of checks and balances to open authoritarian abuse in a hitherto standard-bearing country.

It is without a doubt possible to claim that Sweden is one of the countries least used to rupture in the world, given its more than 200 years of avoiding violent conflict, major pandemics and social revolution (Malmborg, 2001). During this period, the country has moved from a poor, agrarian nation in the 19th century to build and maintain—despite intense global competition—an industrial, export-based economy, coupled with widespread government commitment to welfare for all citizens.

Sweden has, however, undergone change in recent decades to more closely resemble other OECD countries. This means increased globalization, increased privatization and increased inequality among other things (Bergh, 2014). The changes to economic policy from especially about 1985–1997 have even prompted some assertions of a systemic change to neoliberalism (e.g. Andersson and Kvist, 2015). A strong welfare system nonetheless remains in place, with universal coverage, even as many service providers are private companies in, e.g., healthcare and schooling (Kettunen, 2011). Public institutions in Sweden continue to carry significant legitimacy, led by independent experts able to act swiftly and impartially. This is regarded as core to the low perception of elite capture within the country and particularly to low perceptions of corruption (Rothstein, 1998; Rothstein, 2019).

Research on values has consistently shown personal independence as a strong response within the Swedish general public. The individualistic nature of responses in a country often perceived as socialist is evident in the emphasis on personal growth in contrast with low prioritization of religious and family ties compared to global tendencies. The role of the state in this system is thus not so much to support togetherness in a socialist sense, as to protect the individual from the enforced togetherness of family/tradition and religion in a system of “state individualism” (Berggren and Trägårdh, 2015). Correspondingly, the tolerance for authoritarian measures cuts against the grain of a strong societal will to exercise individual freedoms (ibid.).

Recent globalization, and particularly European Union entry in 1994, is increasing governance via supra-national institutions, thereby leading to an enlarged role for experts beyond the nation territory (Barrling and Holmberg, 2019). Like most other countries, Sweden has experienced increased questioning of ruling elites and advice from experts. To date, such questioning remains politically marginalized. But signs of unravelling faith in technocratic approaches do mean that the broad culture of consensus in Swedish politics—based on market-driven, globalized policies and a regulatory state with some ambition to redistribute wealth—has been gradually coming under pressure (Peterson et al., 2018 offer a nuanced backdrop of this long-term trend).

Relative to most countries and similar to other Nordic states, Norway is generally regarded as a strong state context (Christensen, 2003). It is characterized by low risk of elite capture, due to a strong system of checks and balances. It prides itself on not tolerating most authoritarian tendencies at home or abroad, with any exceptional incidents critiqued in public debate. It embodies strong commitment to affirmative action, backed by significant support to relevant global causes, albeit with exceptions to safeguard self-interest (e.g., limited societal acceptance of immigrants and European integration). It exhibits high trust in experts for governance, as evident from its considerable investments in research and a culture of rigorously using evidence to inform decision-making.

Notably, much of what enables this contemporary strong state has its roots in a rupture that began in 1969, with the discovery of some of the world’s largest oil and gas resources in Norwegian waters (Haarstad and Rusten, 2018). Contrary to many countries experiences with a “resource curse”, Norway undertook an exemplary political and administrative response to this windfall (at least at home, cf. Eriksen and Søreide, 2017), instituting a sovereign wealth fund that over the past half century has grown into a trillion-dollar behemoth. Fossil fuel export earnings catapulted Norway’s economy from being below the European average to a global financial player. Thus, even in this disjuncture there is a marked continuity of the long-standing welfare state, subsequently backed by a strong fiscal basis for affirmative action.

A more recent rupture forced the Norwegian state and public to reflect on their sense of self. For instance, the alt-right Utøya massacre of 2011 constituted a moment of national stocktaking (Steen-Johnsen and Winsvold, 2020). It laid bare the challenges of coordination across national institutions and sectors (Christensen et al., 2015). Norway has thereafter strengthened the security state and surveillance apparatus for emergency preparedness with an emphasis on protecting strategic interests.

Bulwarked by its robust economy during the global financial crisis of 2008–2015, Norway reached into its wealth fund in 2016 during a global oil price rut to maintain financial stability and the value of its kroner (Haarstad and Rusten, 2018). This response, as with previous ruptures, shows the affordances that the frontier moment of striking oil in the North Sea in 1969 has opened up for the country’s handling of contemporary crises like COVID-19, but also underscores a persistent concern with national resilience given overt economic dependence on fossil fuels with low diversification.

Table 3 presents a summary overview of the overall assessment for each of the four countries.

Based on a comparison of the above characteristics across countries, we hypothesize the expected propensity for a characteristic in Table 4, using a relative four-point scale of “very low,” “low,” “high” and “very high.”

It is already evident that the pandemic will have deep negative economic consequences, but it is equally likely to impact the nature of the state and the exercise of authority, both now and in the future. As Harari (2020) has argued, “this storm will pass. But the choices we make now could change our lives for years to come.” In democracies in particular, the COVID-19 rupture has most evidently exposed the tension and even trade-offs between security and civil liberties. But it has also set in motion a set of differentiated processes that may change national governance in other domains. Indeed, scholars and commentators have up to now proposed a great variety of post-COVID-19 scenarios, many of which point in opposite directions and are not readily reconcilable.

For example, the decisive role of the state in responding to the crisis may resurrect desires for a strong, interventionist welfare state with greater control over resource allocation. But it may also lead to increased authoritarianism or nationalism (Thomson and Ip, 2020). Similarly, the initial acceptance of digital surveillance technologies in the COVID-19 context may, if it becomes an entrenched technology of governance in the post-pandemic world, lend itself to more authoritarian forms of rule, advancing this biopolitical agenda in the ecology of state territories. In the field of environmentalism, the increased pressure to mitigate the looming economic crisis may torpedo earlier ambitious climate policies; but the COVID-19 crisis may equally consolidate sustainable post-materialist values as people in the Global North and nouveau riche middle-classes in the Global South see the benefits of cutting air travel, working from home, and moving activities to digital platforms (Kuzemko et al., 2020). The role of experts in governance may be re-evaluated in light of the high levels of uncertainty and occasionally poor communication of the knowledge-related side of the crisis. However, in many societies, levels of trust in national public health authorities have increased or remained high, even where states—such as Norway and Sweden–proposed divergent policy measures (Helsingen et al., 2020).

Such contradictory predictions constitute a field of possible outcomes emerging from the rupture. We see these processes of change as open-ended, but accelerated and modulated by the present rupture as the latest in a series of stacked conjunctures over time. We argue that outcomes will vary between different democratic countries, and that the direction of change needs to be empirically explored rather than asserted a priori.

Unlike the country hypotheses in the previous section, our choice of empirical concerns themselves is informed by relevance to the measures adopted by governments in pandemic responses globally: distribution of financial support, mobility restrictions, medical equipment stockpiling and distribution, and infection testing. In this empirical section, we first present strictly descriptive evidence, followed by a more analytically oriented tabulation, and finally reflect on the implications of uncertainty. We draw on some raw national data as well as more fine-grained but less comparable and reliable contextual analysis.

We have strong evidence on national measures to adjust to the pandemic along a similar timeline. We organize this in four categories ordered along matching timelines: fiscal measures and category of beneficiaries, mobility restrictions, stockpiling and distribution of medical equipment; and the extent of testing conducted with results in terms of infection and mortality and as population proportion. Day zero (first known incidence) is specified for each country. This evidence allows us some commensurability across four distinct contexts. For a visual overview, please see virus spread (based on positive tests) in the four case countries in Supplementary Appendix A, drawn from the “Our World in Data” and “Worldometer” websites (also see gray literature data sources by country, provided in Supplementary Appendix B).

None During the First Month. Day 30–60: State Chief Ministers announced various economic “stimulus packages” and/or daily wage payments for labour categories. The Union Finance Minister announced a USD 24 billion national relief package, primarily for migrant labourers and daily wage earners, with USD 2 billion targeted to strengthen the healthcare sector. Wages worth INR 4431 crore (USD 600 million) pending under a national employment guarantee program were released. Heavy food grain subsidies were announced for 800 million Indians. The PM Citizen Assistance and Relief in Emergency Situations Fund (PM Cares) fund was set up with the PM as Chairman, to enable tax-deductible “micro-donations” to fight COVID-19. Day 60–90: PM Cares allocated INR 3100 crore (USD 400 million) to purchase ventilators and help stranded migrant workers. Various direct benefit transfer schemes targeted farmers, women, self-help groups, pensioners, widows and the homeless. Day 90-: Economic aid package worth USD 265 billion announced.

Day 0–30: Thermal Screening of Foreign Arrivals from Select Countries. Day 30–60: All non-essential traveller visas, land border crossings and air travel suspended. The government issued an advisory encouraging social distancing measures. Different states began to restrict mobility and close educational institutions. This was followed by a one-day national “people’s curfew” as a trial run for a 21-days nationwide lockdown on day 55. Day 60–90: Nationwide lockdown extended by 21 days. Day 90-: Nationwide lockdown extended twice for altogether 28 days. The lockdown and restrictions on mobility were graded into red, orange and green zones, depending on the degree of viral spread.

Day 0–15: The export of personal protection equipment (PPE) including masks, gloves and ventilators, was banned, then permitted a week later. Day 15–30: Concerns arose over future medical production, given broken supply chains with COVID-19-hit China. Day 30–60: Major hospitals reported shortage of PPE. Concerns were raised about possible shortage of government hospital beds and ventilators. PPE exports banned again, including the export of raw material for protective masks, and the export of anti-malaria drugs believed to work against COVID-19. Day 60-: Shortage of ventilators, import of used ones allowed. Concerns over testing and treatment capacity persisted, as infection numbers continued to increase.

Testing degree (per thousand people), infected (% of tested population), mortality (% of tested population): Day 0–30: testing <0.01, infected <0.01%, 0% mortality. Day 60: testing <0.01, infected (1,251 cases), mortality (29 dead). Day 90: testing 0.03, 4.29% infected, 0.131% mortality. Day 115: testing 0.07, 4.57% infected, 0.127% mortality.

None initially. Day 60: Initially, USD 8.3 billion was targeted to public health agencies and vaccine research; and USD 192 billion for the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, addressing unemployment insurance benefits, increased Medicaid and food-security spending, free testing, and tax credits to offset costs for employers obligated to offer paid sick leave and family leave. Day 90: The USD 1,721 billion CARES Act included USD 500 billion for loans to large companies deemed critical to national security, and to state and municipal governments; and USD 380 billion for loans to small businesses to avoid laying off employees with costs related to rent and payrolls, and to utilities eligible for loan forgiveness. Taxpayers with annual incomes up to $75,000 were to receive a one-time payment of USD 1,200, with an additional USD 500 per qualifying child. Unemployment benefits were expanded. USD 150 billion was earmarked for healthcare providers, and various tax incentives instituted, including deferral of payroll taxes that fund Social Security and Medicare.

Day 0–15: A federal 14-days quarantine was issued for returnees from China; a presidential order denied entry to foreign visitors to China from the past 2 weeks; a high-alert travel advisory discouraged US citizen travel to China. Day 60: A travel ban denied entry to non-US citizens who had visited Iran or the Schengen area within 2 weeks. 19 states, and Navajo and Yakima nations, issued stay-at-home orders. Day 90: 42 states, and Guam and Puerto Rico, had state-wide stay-at-home orders in place, whereas 19 states had eased such orders. Three cities in states without orders had issued their own orders.

Day 30: Health professionals warned about impending dangerous shortages of PPE and ventilators. Day 60: Federal, state and local governments competed in the market to secure medical supplies at inflated prices. Day 90-: 90% of the federal stockpile of medical equipment had been distributed to states, and the Defense Production Act had been partially enacted to produce ventilators and m95 masks to meet nationwide shortages.

Testing degree (per thousand people), infected (% of tested population), mortality (% of tested population): Day 15: negligible testing, 0.78% infected; 0% mortality. Day 30: negligible testing, 0.66% infected; 0% mortality. Day 60: testing 0.62, 26.78% infected; 0.4% mortality. Day 90: testing 12.19, 18.85% infected; 1.09% mortality. Day 120: testing 38.09, infected 12.23%, mortality 0.69%.

None during the first month. Day 30–60: Repeated and updated fiscal measures were announced by the government and Central Bank. These measures received support from opposition parties, who pushed for even larger measures in a shift from earlier broad political agreement about fiscal prudence as a key political goal. The specific thrust related to unemployment benefits, improved sick leave remuneration, and support to companies forced to retrench employees. Day 90: Fiscal measures reached 10.4–16.1% of GDP (SEK 523–811 billion, approximately USD 55–85 billion) in 3 months. The government continued to reiterate the state’s financial strength and existing political consensus supported continued spending. A clear message from the government was that the historical break from 30 years of fiscal prudence to state-backed financial crisis management was far from reaching its limits.

Day 0–15: No restrictions. Day 30: No restrictions. Day 60: Incoming international travel was restricted in Sweden as part of European Union legislation. Recommendation issued to citizens not to travel to high risk countries drastically reduced non-essential travel while keeping borders formally open. Recommendation issued to reduce domestic mobility between cities and regions. Advisories specifically targeted people above age 70 to refrain from any social interactions outside the household. Breaches to recommendation not liable for fine or other form of penalty, in line with the overall Swedish approach to combating COVID-19 based on personal responsibility. Day 90: Air travel down 90%. Initial recommendation not to cross municipal borders relaxed to a recommended travel radius of 1–2 h by car.

Day 0–15: Significant scarcities were reported across all forms of supplies other than ventilators. Preparations were slow and stock stayed low. In the 1990s, successive governments reduced all military and strategic medical stocks, selling or discarding the last in the 2000s. Day 15–30: Shortages became particularly apparent in elderly care homes. The supply system lacked a national thrust. The government Social Board only acted as an advisory body to regional hospital administrations, which slowly coordinated supplies with hundreds of care home providers. Several international orders for essential supplies were cancelled due to closed borders. Day 30–60: Ad hoc supply arrangements and repurposing old equipment largely met needs despite rapidly increasing patient numbers. Day 60–90: No significant shortages were reported after orders worth SEK 1 billion, as domestic industries and civic initiatives fulfilled demand and imports commenced.

Testing degree (per thousand people), infected (% of tested population), mortality (% of tested population): Day 15: testing 0.51, infected 20%, mortality 0.01%. Day 30: testing 3.65, infected 0.06%, mortality 0.05%. Day 60: testing 5.44, infected 27.18%, mortality 3.94%. Day 90: testing 14.67, infected 20.46%, mortality 2.45%. Testing proved difficult to scale, first due to uncertainties with the technology and specific supplies, and later due to logistical and staff constraints. Testing was not prioritized by the Public Health Authority.

Day 15: the first fiscal measures were introduced, with preliminary rules published on changes to working life and unemployment benefits. Essential services–healthcare and consumables–were maintained, whereas other activities–including kindergartens and schools–were conducted remotely or suspended. Day 30: Notably, by day 19, a crisis package of NOK 100 billion (approximately USD 10 billion) enabled loans to impacted businesses. The lockdown continued, with health advisors and the government adapting policies in concert. The large welfare state safety net offered support to laid-off employees. Day 60: Some lockdown rules were eased, with non-essential services reopening with mandatory social distancing. The period for unemployment benefits was prolonged by 18 days. Day 90: The right to seek compensation for laid-off employees was temporarily extended to cover workers from outside the European Economic Area. Almost all economic activities gradually resumed.

Day 15: A national lockdown was announced and rapidly enforced. Only essential travel was permitted, with restrictions on incoming foreigners, including 14-days quarantine. Norwegians abroad were asked to return to Norway unless stationed abroad long-term. Day 30: The northern region Nordland banned travel from southern regions, despite central government contestation. Municipal measures often exceeded and preceded similar national rules, e.g., on business closures. Those exhibiting mild symptoms were mandated 14-days self-isolation. Day 60: Air travel abroad was down 90 percent. Limited use of public transport was encouraged, and socially distanced hikes recommended. Kindergartens and schools partially reopened, while remote work was recommended. Day 90: Schools reopened fully, and most employers resumed near-regular work practices, with minimal use of public transport encouraged. Buses and trains ran with half their capacity marked as non-use.

Day 0–30: Initially, total respirator capacity was not revealed to strategically avoid panic. Then, Norway announced it had 682 ventilators. An industry-defense collaboration ensured production of 600–1,200 emergency ventilators to meet estimated needs. The government assured funding for 1,000 of these, which health experts however criticized as inadequate for COVID-19. Day 30–90: The pandemic measures flattened the curve and demand for ventilators stayed far below maximum estimates. COVID-19 hospitalisations peaked at 325 patients by Day 35, and declined steadily to below 40 by Day 90.

Testing degree (per thousand people), infected (% of tested population), mortality (% of tested population): Day 15: testing 1.52, infected 11%, mortality <0.01%. Day 30: testing 12.25, infected 5.74%, mortality 0.02%. Day 60: testing 24.20, infected 5.76%, mortality 0.15%. Day 90: testing 38.48, infected 4.01%, mortality 0.11%.

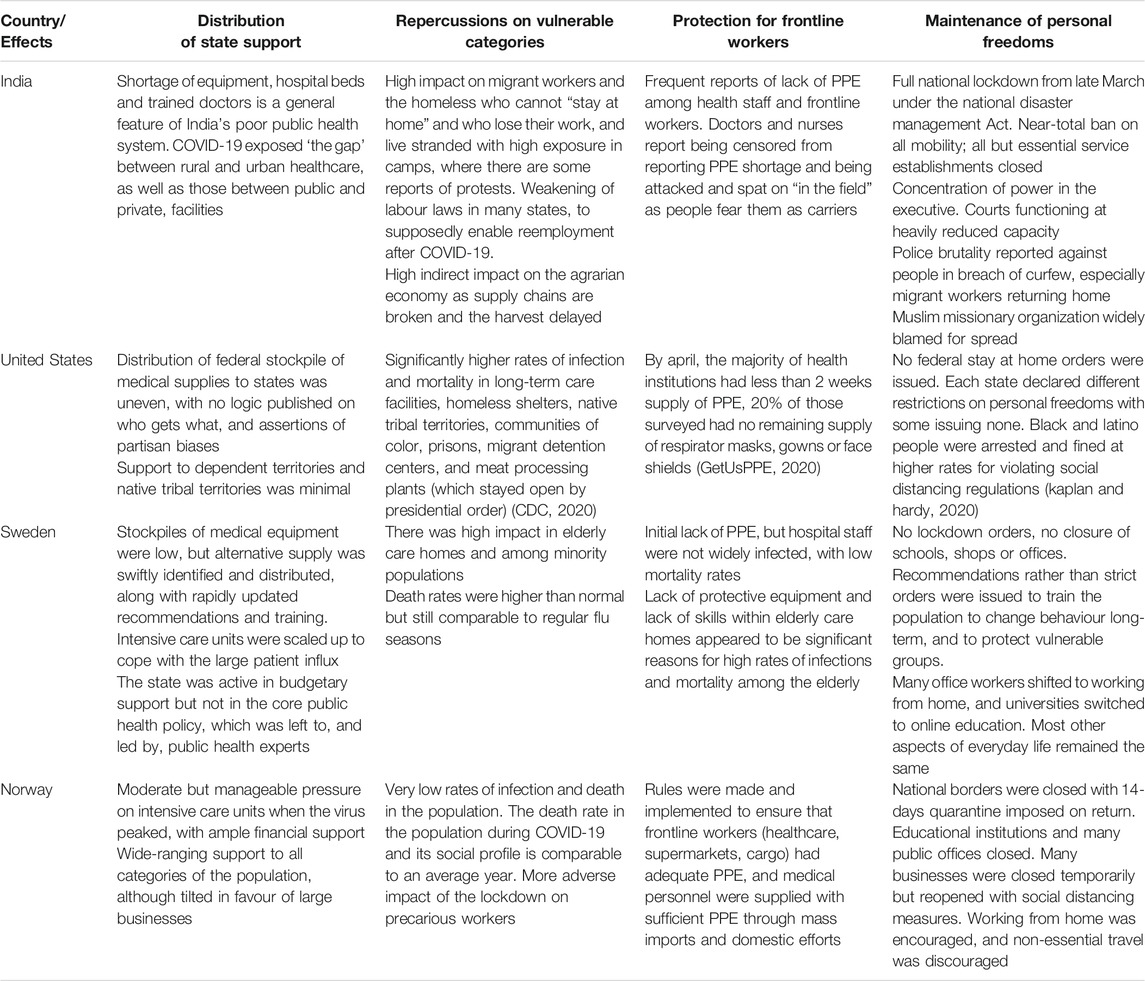

We have anecdotal evidence and emerging detailed reportage on the effects of pandemic responses on different societal actors. We organize this in terms of: distribution of state support (where transparency is not sufficient to assume a match with formal allocations); repercussions on vulnerable categories (e.g. migrants, hospitality sector, temporary workers, tourism sector, the homeless, self-employed and small businesses); protection for healthcare personnel and other frontline workers; and maintenance of law, order and personal freedoms. This reflects political ecology concerns related to resource allocation, equity and rights, and the exercise of authority. Our evidence base is limited to online coverage (in English, Swedish and Norwegian languages) and we aim not at comprehensiveness but at sufficient coverage to support and enrich analytical characterization of variation across countries and conjunctural explanation for each case. We present findings in Table 5. This also highlights the varying challenges the countries faced in terms of state capacity.

TABLE 5. Analytical characterisations of cases by effects (sources: see Supplementary Appendix B).

In terms of uncertainty, there are moreover a number of unknowable facts, both at the time of writing and possibly also later. These include actual numbers of deaths caused by COVID-19, for which testing and monitoring is insufficient, especially in India and to some extent the United States, but also in Sweden based on comparisons of death rates during the same time period in recent years, which exhibit a wider difference than deaths attributed to COVID-19. This also holds true of infected person counts, where testing matters even more; testing rates varied widely and remained abysmally low in India, with Norway having the most rapid rollout among the four cases. Even more challenging to understand at present are the alternative costs to lockdown, i.e., the decreasing wellbeing that stems from a lack of other medical care for serious ailments such as cancer or cardiovascular diseases with severe long-term consequences, as well as from the socio-economic effects of the lockdown. The latter includes joblessness and social isolation, both with well-known effects on personal health. Similar health challenges have been noted from past economic downturns (Zivin et al., 2011), and there is no reason to think that the deep economic difficulties caused by the pandemic and societal responses will not follow similar future patterns.

Importantly, we cannot know at present how well or otherwise containment strategies work over time in terms of infection transmission and mortality effects, and in terms of economic and socio-political repercussions. These uncertainties place clear limits to the scope of our analysis, but because our research design recognizes this, they do not affect the validity of the claims we put forward, which have a basis in evidence.

Having taken stock of the emerging empirical evidence in the previous section, we discuss key similarities and differences between the truisms from extant scholarship focused on rupture-relevant characteristics on the one hand, and the pandemic-specific findings for each of the four countries on the other hand.

What is confirmed by COVID-19? COVID-19 has confirmed and even accelerated India’s turn toward authoritarian populism, with its attendant implications for the concentration of power and privilege. The political response to the virus has certainly been populist, insofar as it has been strong on rhetoric and symbolism, but relatively weak on substance. It was announced relatively late compared to other countries, and with severely inadequate preparation and planning on implementation and consequences. However, the strict nationwide lockdown signalled Modi’s individual capacity for decisiveness, determination, and sacrifice, thus enhancing his standing as a strong national leader. Concurrently, the authoritarian tendency surfaced clearly in violent police crackdowns on people unable to observe curfew, such as the homeless and returning migrant workers, highlighting low commitment to affirmative action and equitable resource allocation in remedying pandemic impacts. The lockdown period has also confirmed India’s adherence to neoliberal economics. Economic stimulus packages were announced late and were small compared to most other countries in terms of additional resources allocated. Fiscal conservatism was prioritized over economic aid so that even the large stimulus package announced in May with much fanfare and populist rhetoric reportedly left both business leaders and social activists “underwhelmed”. In a similar neoliberal and authoritarian vein, the lockdown period has been used to push through dilutions to labour rights and environmental protection in the name of economic growth, with very little parliamentary debate. This shows a tendency toward elite capture. And, in line with dominant Hindu nationalist tendencies, the Muslim organization Tablighi Jamaat has been blamed for bringing the virus to India and spreading it via “corona jihad”, which shows an effort to channel blame away from the state apparatus and toward a vulnerable group in an increasingly Hindu fundamentalist context.

What is challenged by COVID-19? Rather than outright challenging hypothesized propensities about India, the COVID-19 crisis shines a clearer light on aspects of these propensities. In this regard, COVID-19 potentially helps us see the contours of state capacity and authority more clearly, especially in the domain of poverty reduction. Specifically, the inability or unwillingness of the government to aid the millions of migrant workers who were immediately affected by the lockdown tells us several important things. First, it indicates that the Indian state has–for ideological reasons that align with neoliberal ethics of individual entrepreneurship and responsibility–now more decisively abandoned its commitment to welfare, redistribution, and pro-poor interventions. The state, in other words, can be tough on dissent (when people break curfew) but indifferent to social suffering, constructing territories of exclusion and conditions for injustice. Second, it also indicates that the Indian state, in spite of being hailed as an emerging market with high growth rates for many decades, remains a relatively poor state with limited capacity to address situations of intense crisis, which reflects poorly on the role of expertize in governance. Third, the inability to handle the humanitarian fallouts of the crisis and the lockdown shines a light on the lopsided nature of economic growth encouraged by the Indian state over decades, where precious little has been channelled into improving public infrastructure such as the health system. Decades of high economic growth may well have lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, but only barely so. And the COVID-19 crisis has already pushed 75 million of them back into poverty.3 This suggests a political ecology where the state commits resources less to vulnerable groups and more to shore up its own authority; ironically, this rupture’s stark exposure of this tendency may itself undermine such state authority.

What is confirmed by COVID-19? A crisis situation like COVID-19 could perhaps lead us to expect that existing institutions would reassert their value in trusted modes of governance and in the value of science. This has, however, not happened. On the contrary, lack of initiative, misinformation, and radically uncertain blame games have characterized the US response. Dissonance between the imagined greatness of the United States and the realities of domestic poverty, disenfranchisement and partisan polarization have crippled public debate. Characterized by “post-truth” (cf. McIntyre, 2018), the pretence of accountability has been abandoned. A continuum across discontiguous ruptures from 9/11 to COVID-19 can be seen to concentrate power in the state apparatus while undermining accountability across sectors (cf. Daoudi, 2020). The federal state’s attention is mainly focused on business, and its initiatives are accompanied by the risk of elite capture, as tax credits and spending benefit large companies and already-wealthy large business owners. The vulnerability of many groups as exposed through past ruptures continues to deepen, with little to no commitment to affirmative action in the national COVID-19 response in the study period. In some ways, the state response to COVID-19 has exacerbated the challenges faced by marginalized communities.

What is challenged by COVID-19? The pandemic appears to challenge the United States’s role as a global leader in the world. Trust in the state apparatus use of experts may be even lower than hypothesized, with the then-president announcing that he is taking chloroquine to prevent contracting COVID-19, a drug that experts agree is not proven to be effective and could lead to harm (cf. Yazdany and Kim, 2020). While anti-vaccination groups had been marginal before the pandemic, they have been bolstered by the then-president, increasing the challenge of eventual vaccination drives and revealing little respect for expertize in formal governance mechanisms. By contrast, tolerance to authoritarian measures may be lower than hypothesized. The lockdowns and stay-at-home orders represent the first time a large section of the population has so viscerally experienced authoritarian measures, which until now had mostly impacted marginalized groups. While previous erosions of the constitution in the name of countering terrorism and economic collapse went largely unchallenged, this temporary restriction of personal freedoms in the name of public health has been met with vehement and sometimes armed opposition in several states. This underscores limits to state authority and suggests an evolving political ecology where individual power can be exercised to erode formal authority.

What is confirmed by COVID-19? Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic Sweden was experiencing, on the face of it, one of its most successful periods of sustained economic growth, low unemployment and strong state finances. And yet, national politics were under strain with increasing inequalities apparent, rising concerns of violent crime and populist, and heightening anti-immigrant sentiments. Rather than putting further pressure on national authority, COVID-19 appears to have strengthened a weak coalition government under pressure, and generated greater overall confidence in the government and the need for a strong state among the general public. This is evident from a number of national polls carried out since the start of the crisis. Similarly reaffirmed trust is exhibited in government experts who were otherwise undermined by the widespread outsourcing of activities to the private sector, and the growing support for populist parties who challenge elites and technocratic knowledge. General trust in the national approach to COVID-19 has been supported by the political opposition which has refrained from critical remarks, other than to request increased state spending, marking a move to expand state authority over resource allocation. As the pre-pandemic mainstream political consensus appeared under challenge from right-wing populism, this rupture marks a reassertion of the welfare state model of governance.

What is challenged by COVID-19? Challenges in the short term appear modest, in large part due to coalescing political and technocratic elites keen to see out the crisis before any wider debate or reckoning takes place. The somewhat retreating Swedish state with its emphasis on fiscal prudence and market forces is, as noted above, reasserting its usefulness during the crisis. State spending has regained popularity with a wave of economic packages and forms of support granted for citizens as well as businesses, revealing a broadly egalitarian governance approach to resource allocation. Relatedly, emergency response systems and particularly emergency supplies are also back in favour, if not to replace then at least to ascertain the need for national emergency preparedness of critical items. In recent decades, these have been procured through a globalized, efficient supply system with China at the center. On a complementary note, poor worker conditions within elderly care homes have resulted in reduced education, skills and overall quality of treatment, and here, neoliberal policies and forms of governance may require a rethink. However, major reforms reducing employment security have been proposed in the meantime, based on earlier promises during coalition government formation in early 2019. This marks an evolving political ecology where care workers, instead of being supported through affirmative action as a vulnerable group, are further marginalised.

What is confirmed by COVID-19? Norway’s response to this pandemic is closely aligned with its state characteristics at times of previous ruptures. The population relies on the state to safeguard its interests, and in rising to this need the state simultaneously secures its own interests—of political stability, of a strong large industrial presence as an economic backbone, and of a well-functioning political-administrative democracy. The leverage Norway gained from its adept handling of the 1969 rupture is evident in how it navigated the early stages of COVID-19, responding rapidly with preventive measures at significant economic cost, and being adaptive in the extent and duration of lockdown based on health expertize and administrative savvy. It is hard to separate political coordination and financial leverage when attributing reasons for its response—having a financial cushion made pandemic response easier. While this seems plausible in hindsight, the step-by-step response was nonetheless marked by uncertainty: would people accept stringent lockdown measures before a major outbreak? And would the economic burden be justified as the pandemic continued, potentially for over a year, requiring less expensive measures? It appears that the state, by acting decisively and being responsive to changing needs, was able to create political appetite and a constituency that backed its stringent response, enlarging its authority and control over resources.

What is challenged by COVID-19? Despite strong public approval of the state’s response to COVID-19, and broad agreement across political parties, the pandemic brought out a weakness that marks a persistent rift in Norwegian politics—its future in the global economy. Demand for oil slumped globally during the pandemic, and the Norwegian kroner fell sharply, highlighting the complexity and contingency of a governance approach so reliant on the global ecology of fossil fuel. A scandal emerged contemporaneously, with Norway’s oil major posting a NOK 200 billion (approximately USD 20 billion) loss in its US operations (NRK, 2020). The political right made a push to go all-in on jobs and abandon environmental considerations in the face of layoffs and rising unemployment. The green party pushed for a green economic recovery package and environmental commentators critiqued state support to oil interests. These political dynamics are notable beyond Norway in Europe and elsewhere, but for Norway they pose a question of future identity and deepening divides in what governance approach enjoys public legitimacy and drives resource use. Thus, this rupture constitutes an antithesis of the 1969 rupture where the national “oil adventure” began; it forces a stocktake on how and when Norway can exit this adventure without courting economic disaster, and what can replace its dominant industry. Unlike the 2001 and 2011 ruptures, when the security state united political interests, or the 2016 exception when the sovereign wealth fund bolstered a faltering kroner, this rupture brings to the fore a question of national interest where a single direction of consensus is as yet unclear. It is clear that the state must urgently confront its own identity.

In considering how these concerns cut across our four cases, we note that the COVID-19 response provides us with a crystallization of existing trends within each country setting. The pandemic has accelerated reluctance to use the central government as a tool of intervention when it might upset the fiscal balance, leading to a delayed response carried out in haste in neoliberal India and the United States. Conversely, state spending has increased in Sweden and Norway. Previously frugal national budgets compared to earlier decades of state spending are here coming in for a major revision. In all cases, the rupture has accelerated existing tendencies in the political ecology of resource governance.

The comparisons across our four countries focused especially on India-USA and Norway-Sweden for reasons of commensurability in terms of scale and heterogeneity. We saw India and the United States as major countries with large and diverse populations, and increasing central concentration of political economic power, constituting a move to governance with increasingly authoritarian characteristics that tend to concentrate power and privilege. Norway and Sweden being neighbouring Nordic small states with similar, relatively homogenous populations and welfare state functions (cf. Kristensen and Lilja, 2011) were not easy to separate along the four criteria in our country analyses. And yet, it is imminently clear that both countries have taken quite different approaches to dealing with COVID-19, aiming to expand state authority in contrasting ways.

The form and execution of responses aligns with pre-existing trends toward authoritarianism in India and the United States: both played the blame game more or less openly, Trump by accusing China for the spread, Modi and his Hindu nationalist government by blaming a Muslim missionary organization. To the extent that there has been a blame game in Norway, it has rational roots in blaming people who broke the national “dugnad” (teamwork) of mobility restrictions by going shopping in Sweden, or visiting countryside cabins, without subsequent quarantine. The lack of precise and binding regulations in Sweden has meant reduced scope for apportioning blame, but also a lack of accountability. Thus, the apportionment of blame—transnationally in the United States, internally on a vulnerable group in India, on sub-groups with formal violations in Norway and negligibly in Sweden—reveals diverse political ecologies linked with national discourses of viral spread pathways.

The rupture has also exposed hitherto debated truisms for which there is now hard evidence: the callousness of the leadership in the United States and India. This throws into question the romanticized American dream. The United States is undeniably a country of poor people: in 2016, 63% of US citizens lacked USD 500 in savings for an emergency, 34% had no savings at all, and the official poverty rate was 12.7 percent (Edelman, 2020). Comparably, while India has been regarded as poor but ascendant, the nationalist myth of “India Shining” perpetuated by the ruling party now appears very hollow in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only does India lack a public health infrastructure equipped to deal with crises, its state apparatus has been unable to, and perhaps even unwilling to, tend to the needs of poor workers, urban migrants and rural dwellers who are rendered almost entirely dependent on state support in emergencies. A large number of officially non-poor Indians in reality live precarious lives, as Cyclone Amphan of May 2020 served as a stark reminder of, exacerbating COVID-19 adversity. In both countries, the rupture reveals failures of governance to adequately address inequity in their initial pandemic responses.

One apparent outcome of this reasoning is that the United States is no longer an unquestionable global leader. American exceptionalism has made it difficult to compare with other countries until now. Its inability to cope with the pandemic reveals weaknesses that tilt global geopolitical dynamics in favour of China, whose authoritarian state apparatus enabled more efficiently coordinated top-down action. Norway has closely followed trends in the US, such as the war on drugs, the invasion of Iraq, and neoliberal economic policies, but future political appetite for such commitments may well diverge. With US elections taking place in late 2020, the pandemic struck at a crucial moment in its national politics, in a notably contrasting manner to India, where the incumbent was re-elected in 2019.

As we note a range of worrying concerns, particularly in India and the United States, we ask: has the pandemic created new opportunities to exercise public control over governance decisions such as resource allocation? In the United States, some Trump supporters were displeased by restrictions on personal freedoms and defied the state. India’s COVID-19 response accelerated existing trends in the remaking of the state and consolidated its authority, while also exposing uncomfortable truths and state weaknesses that may open up new spaces for future political contestation. But our analysis of this rupture is also revelatory in relation to uneasy political phenomena that have surfaced in Sweden and Norway. In Sweden, trust in experts for governance seems to continue undeterred, supported by a political calculus to boost public spending and return the welfare state centre-stage, increasing its resource control at a time when many of its services have already been contracted out to private providers. In Norway, the rupture highlights a critical tussle as the harbinger of the coming choice for its future national identity: will Norway remain contented with continued dependence on an oil economy, or will this recognition of its vulnerability to global economic and environmental vagaries catalyze more vigorous debate on diversification for resilience, with public opinion swaying governance decisions?

In light of the above, we revisit our hypotheses of the four countries in Table 6. We argue that the rupture reveals some departures from the truisms of scholarship. India and the United States exhibit strong risks of elite capture, both display low levels of commitment to affirmative action, and both show a lack of trust in experts in their governance approaches—we had hypothesized that the United States would fare better in all three regards. This poorer than expected performance may be linked with the specific political moment the United States was experiencing during the pandemic, with pronounced authoritarian traits comparable to political developments in India. Norway performs better than Sweden on commitment to affirmative action, albeit marginally, for its safeguarding of high-risk populations through a broad approach. On the other hand, Sweden displays less tolerance to authoritarian measures than Norway. We explain this by noting that while both countries have strong trust in experts, their modes of acting on this expertize differ: Norway coordinates thematic and administrative expertize whereas Sweden takes a sector-specific approach with experts in charge. This could well play out differently in other kinds of ruptures than COVID-19 and sectors other than healthcare, hence we are careful not to over-generalize from this analysis.

In this article, we have compared and contrasted responses to COVID-19 across four countries to understand core, dynamic characteristics of governance—and thus the political ecology of governance—in each country. This approach is based on the urgent need for more scholarly engagement with realpolitik and international relations as these take shape during dramatic ruptures with emergent consequences, something that political ecologists have been found wanting at (Braun, 2015). It is only by embedding analyses within uncertain and still unfolding ruptures that we can understand already emerging conjunctures clearly and in a timely manner (Sultana, 2020). What we argue for is thus the crystallizing function of a crisis such as COVID-19 for critical scholarship on the state that challenges existing truisms.

During the present rupture, we note stronger recognition of the role of the state across our countries. Expressions of stateness, however, take on widely different characteristics, with a concentration of power in top leadership with authoritarian and anti-science policies in India and the United States, but a recommitment to state support for marginalized groups and an expanded role of the state in Norway and Sweden, albeit with lacunae related to care workers in Sweden. The welfare state is clearly back in favour, and perhaps so is the need for a welfare state, having seen gradual erosion in all four countries. This characterization may not seem to square easily with the United States case, given the particular political moment it was experiencing during the study period, but we point to Trump’s extensive use of executive orders to act in deeply impactful ways through the state apparatus. While many of these interventions served to roll back the regulatory role of the state, ironically they also underscored just how significant state presence is in people’s lives, through centralized state control over resources and territory (including mobility), and over knowledge production. In both the United States and India, there are notable sub-national differences in initial responses to the extent that states exercise discretionary authority; while beyond the scope of our study, this merits attention.

In the varied national responses to the pandemic, we find that some issues have become depoliticized while others have become repoliticized by drawing in new constituencies. Particularly in Sweden, the almost complete placement of control in the hands of the Public Health Authority and its technocratic experts, with the government acting as financial backer rather than administrator, has depoliticized the response. Science has served as a tool to depoliticize resource allocation decisions and the exercise of state authority on domains such as freedom of personal mobility, in marked contrast with the more direct role of politics in Norway. It is possible to attribute this to the Swedish constitution’s strong emphasis on individual freedoms, which we see as co-constitutive with contemporary national identity. This identity is in turn itself socially reinforced; Sunnercrantz. (2020) argues that media coverage strategically deployed narratives of Swedish exceptionalism and the state epidemiologist contra other domestic and foreign experts. While the Norwegian response appears well in tune with science based on study period results, the government adopted stricter guidelines than those recommended by its public health experts, relating to the stringency of lockdown, which raises questions of the scope of its control over significant long-term resources, notably the trillion dollar sovereign wealth fund. These differences are perhaps best explained by different cultures of crisis awareness, and a Swedish coalition government that was weakly poized to act swiftly on complex issues at the time. The moment in political dynamics when the pandemic arose has clearly had some bearing on each of the four state responses.

Returning to our concern with political ecology research on state quality and rupture (Lund 2016; Rasmussen and Lund 2018), we reflect on the value of a comparative analysis of emergent state responses to a major contemporary global rupture. This exercise has enabled us to identify the key characteristics that are in play during emergent reterritorialization dynamics for this particular rupture. These dynamics include the sharpening and acceleration of existing governance trends (e.g., elite capture and shifts toward authoritarianism) as well as the emergence or contestation of suppressed ones (e.g., welfare state expansion, the marginalization of specific vulnerable groups). Political ecologists can extend such enquiry by reflecting explicitly on the territorial strategies, political capabilities and epistemological systems (Robbins, 2008) mobilized by specific states in response to COVID-19. Such accounts can link empirical analysis of the effect of power at multiple scales (which Robbins is concerned with) to conceptualisations of emergent contestation over state quality and the changing nature of statehood (a concern that runs through Lund’s work) in greater depth than we are able to offer in this four-country analysis. Norval. (2016): 150) notes that “It is necessary to retain an analytical distinction between the event of the crisis, and the discursive articulation of that event as a crisis.” We hope to have conveyed a situated sense of territorialization dynamics linked to this rupture in its initial phase and to have thus furnished a basis for deeper analyses of its protracted aftermath, in a manner that enables political ecologists to draw approaches to characterizing governance into generative entanglement.

To conclude, our comparative case analysis in four established democracies indicates that longer-term trends of independent institutions able to counterbalance authoritarian leaders—and to thus maintain public checks to the concentration of power and privilege in resource governance—appear dramatically missing at “frontier moments” of rupture. Iterative ruptures over time allow for radical institutional change or an intensification of a tendency that serves the interests of well-positioned actors, notably incumbents.4 These are worrying traits for proponents of democracy, and for those who cherish the concern of political ecology with equity, access and rights in relation to the reconfigured governance of changing ecologies. A wider range of state—including sub-national—responses to such ruptures merit closer attention. We hope this attempt will motivate others to study COVID-19 responses in other contexts over time, and identify what sort of rules show resurgence across ruptures, leading to a curious punctuated politics of reconfiguration.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

SS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Data curation, Writing—Original draft preparation and Review and editing. KN, PO, DR (in alphabetical order by last name): Data curation, Writing—Original draft preparation and Review and editing.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fhumd.2021.636422/full#supplementary-material

1These tendencies are at play to various extents in any state, including Scandinavian ones (Törnquist and Harriss, 2016).

2In the 2021 ratings, India was downgraded and categorized as only partly free, which highlights the changing nature of state quality. See https://freedomhouse.org/country/india/freedom-world/2021 (accessed 21.5.2021).

3Source: Covid pandemic pushes 75 million more people into poverty in India: Study accessed on 16.4.2021 at https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/19/covid-pandemic-pushes-75-million-more-people-into-poverty-in-india-study.html.

4As an instance of the latter, see government responses in terms of planned higher fossil fuel production after COVID-19 in this report, which includes India, the United States and Norway, accessed 16.4.2021: http://productiongap.org/2020report.

Adger, W. N., Benjaminsen, T. A., Brown, K., and Svarstad, H. (2001). Advancing a Political Ecology of Global Environmental Discourses. Dev. Change 32 (4), 681–715. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00222

Agrawal, A. (2005). Technologies of Government and the Making of Subjects. Durham: Duke University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11sn32g

Andersson, K., and Kvist, E. (2015). The Neoliberal Turn and the Marketization of Care: The Transformation of Eldercare in Sweden. Eur. J. Women's Stud. 22 (3), 274–287. doi:10.1177/1350506814544912

Barrling, K., and Holmberg, S. (2019). in Demokratins Framtid (Stockholm: The Swedish Parliament). Available at: https://firademokratin.riksdagen.se/globalassets/05.-global/bestall-och-ladda-ner/demokratins-framtid-antologi-v2x.pdf.

Berggren, H., and Trägårdh, L. (2015). “Är Svensken Människa? Gemenskap Och Oberoende I Det Moderna Sverige [Is the Swede Human?,” in Togetherness and independence in Modern Sweden. 2nd edition (Stockholm: Norstedts förl).

Bergh, A. (2014). Sweden and the Revival of the Capitalist Welfare State. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. doi:10.4337/9781783473502

Braun, B. (2015). “Rethinking Political Ecology for the Anthropocene,” in The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, London and New York, Routledge 102.

Chacko, P. (2018). The Right Turn in India: Authoritarianism, Populism and Neoliberalisation. J. Contemp. Asia 48 (4), 541–565. doi:10.1080/00472336.2018.1446546