95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Hum. Dyn. , 29 January 2021

Sec. Social Networks

Volume 2 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2020.615865

This article is part of the Research Topic Social Cure During COVID-19: The Role of Social Connections, Social Networks and Digital Technologies View all 11 articles

The present work presents an analytical and investigatory view of the existing issues regarding COVID-19 with attention to children and their overall well-being during the second quarter of 2020. The authors conducted an extensive content analysis of media reports, government briefings, social platforms, and provide some recommendations to the policymakers and care providers for building more robust responses for the pandemic affected children. The article contributes to the existing field of study in the following ways. Firstly, the present manuscript describes the impact of COVID-19 on the psychosocial health of children. Secondly, the authors offered some outcome-based responses to policymakers and caregivers to mitigate the negative impact of the pandemic on COVID affected families and children. Thirdly, the article highlights the importance of social media, the role of storytelling, and using the concept of mandalas in handling the pandemic affected sensitive sections of the society. Lastly, the authors furnish some response initiatives to combat the novel COVID-19 pandemic based on real-world observations. These initiatives can influence policymakers as well as help caregivers to design efficient and adequate response programs for the pandemic affected children.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to ravage and spread in India as well as across the globe, it is increasingly becoming certain that the pandemic would leave a profound impact on mental health care (Jaspal and Lopes, 2020; Xiang et al., 2020) of the humankind. Not only in India, but the entire globe is experiencing the detrimental effect of COVID-19 on the psychological health of people (Gupta, 2020). The major psychosocial effect of this pandemic has resulted in school closures, lack of outdoor activity, aberrant dietary and sleeping habits which are likely to disrupt children’s usual lifestyle and would strongly promote mental stress, impatience, annoyance, and other neurotic diseases (Ghosh et al., 2020). In the current reality of extended lockdown and movement restriction measures, children have been stripped of their access to socialization owing to school closures (UNESCO, 2020) restricted outdoor movements, and no physical contact with their peers. This may also lead to increased levels of frustration and anxiety (Idoiaga et al., 2020). Moreover, an increase in the use of digital and social media platforms especially among adolescents may also lead to such negative outcomes. It is also observed that COVID-19 has led to the emergence of new and unknown stressors for adults as well as caregivers (Sun et al., 2020). This may inhibit their capability to provide care and remain effectively engaged with their children who are keen observers of their environments. Children may become aware of how their primary caregivers absorb and react to stressors in their environment which would unavoidably affect how they would react and would affect their overall well-being. Such a detrimental effect would be exponentially high among vulnerable families such as children who are deprived of parental care in childcare institutions or alternative care, children living in the streets, or children of migrants (Ghosh et al., 2020). Tracing from the literature, outcomes from public health emergencies have established a higher likelihood of an increase of violence (Mittal and Singh, 2020) including gender-based violence (Magnus and Stasio, 2020; Simonovic, 2020), domestic violence (Kumar et al., 2020) or corporal punishment against children and women. The present work focuses on assessing the significant impact which the current pandemic “is having” on children. The authors offer their views about the needs, circumstances, and experiences of vulnerable children and young people in this pandemic. The authors end with some suggestions for caregivers and policymakers to handle heightened issues of anxiety and pressure imposed on children because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study had reviewed several online research articles published, newspaper stories, government reports, and international organizations reports, using manual content analysis. It was a cross-sectional analysis that analyzed the English media reports and journal articles released in the time frame between February 2020 to August 2020. The authors had developed a standardized format for data collection. The authors searched the internet using the keywords such as “pandemic affected children,” “domestic violence during COVID 19,” “parenting during COVID 19,” “mental health of caregivers,” “quarantine,” “lockdown,” “public policy” and “physical literacy” and their combinations. Both authors performed data management and cleaning. The cited articles are selected based on their relevance in themes identified as the authors deem fit. Most of the articles cited are from renowned publishers like Elsevier, Emerald, Sage, Springer, Taylor and Francis, and Wiley. The selected research papers were not limited only to India but also from the United States, United Kingdom, and Europe to gain an international view of the topic. As the researchers analyzed the papers already written, there was no need to get the formal ethical clearance for citing them. The key themes identified and discussed included COVID-affected families and children, the quarantine issues in public health, and the detrimental effect of COVID 19 on disabled children.

Global statistics have shown the far-reaching consequences and effects of the current pandemic. Such effects are evident in a survey that posited that during the month of April, 70% of women have assumed the sole responsibility of their households and 66% of women are the primary caregivers of their children (New York Times, 2020). Such figures are preliminary examples of how COVID-19 has impacted societal family dynamics. Similarly, some reports have noted significant negative disruptions caused by COVID-19 to crucial areas such as vaccination, nutrition as well as children’s health services in general (Shen and Yang, 2020). Such reports seem to suggest that over the next 12 months, South Asian countries might see more than 800,000 deaths of children aged five and under. Similarly, they project a death toll of 36,000 mothers. Most of these deaths would be accounted for by India and Pakistan (UNICEF, 2020). Projections also signal that countries such as Bangladesh and Afghanistan could face a high mortality rate (The New Indian Express, 2020).

Psychologically, it is evident that the disruptions to normal life brought about by the current pandemic have rendered children more prone to experience heightened levels of stress and anxiety (Restubog et al., 2020). It has been suggested that statistically, susceptibility to such adverse psychological effects is incrementally high among age groups from 2-year old to adolescents (Singh et al., 2020a; Singh et al., 2020b). With regards to the current pandemic, children might ask themselves if they would lose their loved ones due to COVID-19 which ultimately would lead to an immense level of stress as well as an inability to effectively regulate their emotions. A survey on doctors indicated that medical professionals believe that the psychological toll of COVID-19 on children would far outweigh any physical illness because of this virus (The Hindu, 2020). There is an urgent need to implement strategies that would ensure the good mental health of children during these trying times (NIMHANS, 2020). Jiao et al. (2020) in their study in China identified the presence of psychological problems in children amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, such as fear, clinging, inattention, and irritability. Further, it is estimated that because of the sudden changes happening globally, at least 65% of children are now addicted to electronic devices (Perez, 2020). To add on to this, some children have started exhibiting rebellious behavior that includes not listening to their parents, anger outbursts, increasing frustration, and so on (Times of India, 2020). Thus, children in these families may feel less understood by their parents and may respond in a more rebellious manner (Pinquart, 2017). Moreover, because of this, there is an alarming fear that there would be increased incidents of cyberbullying as COVID-19 would push more children to engage in online interactions as a coping mechanism (Readers Digest, 2020). There is an immediate need to develop social policies that would markedly improve the lives of children (Idoiaga et al., 2020). Such policies would need to bridge the gap between what exists between the role schools were playing in socializing children and how they integrated into society. As the learning process is fast becoming virtualized, there is a serious threat that this may affect peer to peer association, teacher-student association as well as the community overall. As such, there is a risk that children would negatively react to this new reality (The Wire, 2020). Similarly, with the global movement of people which has been prominent in the last 20 years, it is estimated that the current lockdown conditions in most countries would inexplicably affect the lives of first-generation immigrants as well as their children (Economic Times, 2020). This is projected to be the result of their children’s inability to access opportunities to learn, practice, and socialize in their second language outside of their homes. Also, it is projected that there would be an increase in domestic abuse cases due to living in overcrowded accommodations. This would lead to children being witnesses to grave acts of violence, thereby affecting their mental well-being. (BBC, 2020).

It is worth noting that lockdowns and social distance interventions are likely to disrupt transport networks and supply chains (Chaturvedi et al., 2020). It is going to present a challenge to ensure food security and to monitor already widespread malnutrition among children leading to increased mortality among infants and children (Khanna, 2020). Apart from the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on children’s well-being in general, a specific group of children, such as teenage girls, may be more vulnerable to the damaging impact of the pandemic (Kumar et al., 2020). It is because when they are kept within confines to abusive environments owing to the current pandemic situation, they would not be able to escape from their abusers. Statistical data from activists and survivors from different parts of the continent (e.g., Brazil, Germany, China) have voiced concerns that they are already witnessing an alarming increase in abuse cases (Campbell, 2020; Godin, 2020, WHO, 2020; Women, 2020a, Women, 2020b). As highlighted earlier, these measures push children to be dependent on electronic devices for socialization and thus more prone to sexual abuse or sexual exploitation (Kumar et al., 2020) as they may not be under constant adult supervision. According to the National Herald (2020), COVID-19 has also impacted homeless children. These children confined themselves to restricted spaces where they are unable to go out and play (Jiloha, 2020). It puts them at risk of being physically and emotionally abused (Grechyna, 2020). In addition to this, it also includes children with physical disabilities, for instance, children who are deaf are even more vulnerable than their peers (The Guardian International Edition, 2020). Young children with disabilities observed were having heightened responses to traumatic events of the current pandemic. It might have several negative impacts on disabled children, such as increased worry, distress, and a feeling of losing control, to name a few (Jiloha, 2020). Such detrimental effects are usually long-term in children with emotional or intellectual limitations who require additional care who might not be able to have access to them because of the current situation.

Therefore, there is an urgent need for governments to ensure adequate measures that would mitigate the negative impact brought about by the closure of academic institutions (Mukhtar, 2020). Such measures must include safeguarding the health and well-being of students (Dharmshaktu et al., 2020) and staff members and aim at reducing the stigma of the coronavirus (Singh et al., 2020a; Singh et al., 2020b). The authors have tried to give some suggestions to the policymakers and caregivers in the following section to tackle the current situation.

There are a variety of ways in which children may react to the current reality. These may include adverse psychological distress, angry outbursts, and hyperactivity to name a few. Therefore, primary caregivers must pay close attention to their children to understand how their emotions are constantly changing during this tough period (Chaturvedi, 2020). Also, care should be taken to maintain active routines and schedules to help children to manage their time and avoid disruptive behavior because of witnessing violence or being victims of abuse. There is also a need for early psychological intervention and informative interactions that inform children that nobody should be abused or stigmatized for having any illness (Singh et al., 2020a; Singh et al., 2020b). More importantly, the number of time children spend on online platforms should be supervised and limited as they may be exposed to distressing information. Caregivers should also consider including mental health professionals to assist in addressing the anxiety that children may experience when there is a death or illness in the family.

Summarily, there are priority actions that are urgently needed across different sectors working along with governments to ensure effective vulnerable child protection-sensitive response. In several nations, a recent phenomenon known as physical literacy is now well known (Shahidi et al., 2020). As defined by Whitehead, 2001, “Physical literacy refers to the confidence, competence, motivation, knowledge, and understanding to value and take responsibility for engagement in physical activities throughout the lifespan” (cited by Brian et al., 2019). The development and maintenance of physical literacy are of vital importance for disabled children (Pohl et al., 2019), who are under-represented and vulnerable during this pandemic. The policymakers and caregivers can do fun interventions for disabled children, for instance, the circus arts program to keep children active and mentally engaged during this pandemic (Kriellaars et al., 2019). In addition, many digital channels provide disadvantaged children with programs. For example, the Canadian “PLAYBuilder” platform is a cloud-based framework that offers activities to help children stay active and aware during a coronavirus pandemic while they are at home (https://sportforlife.ca/). “Appetite to Play” is another online program in Canada aimed at encouraging and enhancing good health and early childhood physical activity (https://www.appetitetoplay.com/). Along with this, caregivers can ensure the availability of standardized and effective procedures for documentation and referral processes for children between different sectors to enable children to access adequate and appropriate services. For instance, New Zealand has pioneered a social bubble model, allowing a given group of people to have close physical interactions and to practice physical separation rules with those outside the group (Long et al., 2020). This method allowed the start of the lock-down family bubbles to progressively be expanded to small and specific groups of family and friends and to be further activated. This concept was sponsored by the United Kingdom nations and since June 2020 a similar bubble support arrangement has been introduced.

It is recommended to the caregivers to avoid using a vocabulary that has negative connotations that may increase stigmatization; for example, to avoid adding a position or ethnicity to the disease, not to mark patients as victims or COVID-19 cases, but to classify them as “people who have COVID-19” to speak about “acquiring” or “contracting” the disease, and not to use a phrase that may increase stigmatization. It is further advised to educate kids about stages of corona when it is communicable and when not communicable to create proper awareness. Since we know that children have lower personal resources to cope with the many changes that the pandemic poses on their lives (Liu et al., 2020) and recommendations say that parents should address and clarify the situation with them so they have the right awareness of what’s going on. And the causes of the constraints that kids encounter are essential to the prevention of harmful psychological effects (Dalton et al., 2020). But how and when to do so is left entirely up to the parents’ decision. We might believe that more depressed parents may be too distracted by the situation to find effective ways to be a caring figure for their children and to find the best ways to resolve children’s problems and concerns (DiGiovanni et al., 2004). When kids do not find responsive responses from adults to their concerns, they may experience more anxiety, signs of more emotional and behavioral issues as well as a loss of focus, and difficulty in concentrating. Child healthcare providers should provide parents with an awareness of, for example, how children at various ages communicate anxiety and the value of expressing and communicating about worries and negative emotions (Dalton et al., 2020). In this way, even less resilient and more depressed parents can be encouraged to find ways to recognize and nurture their children (Belsky, 1984; Coyne et al., 2020). Besides this, policymakers should create strong and harmonized child-focused messages in the community about children’s risks and vulnerabilities about disease outbreaks as per global recommendations (Clark et al., 2020) because it is seen that a similar zoonotic disease known as Brucellosis is spreading to humans in Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu province (The Tribune, 2020). It was first discovered in November 2019. By the end of December, around 181 people at the Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute had been infected. Therefore, it looks like these zoonotic diseases would keep impacting human lives forever. These disease outbreaks had provided checklists for supervisors, instructors, parents, and children. The checklist includes empowering children to ask questions and to voice their concerns. For example, the safe school guidelines introduced in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone during the outbreak of the Ebola virus from 2014 to 2016 helped reduce school-based transmission of the virus.

One way to share COVID-19 related knowledge with children is through illustrated eBooks. A variety of organizations such as St Jude’s Children’s Hospital and Oxford Press, health practitioners such as Block and Block (2020) involved in helping children in these difficult times have designed free eBooks for children. Children’s educational media, such as television shows, short films, games, eBooks, etc., may be used as resources to promote discussions between children, families, and educators about the COVID-19 pandemic and other circumstances where health-related knowledge can be daunting for young children. From the theoretical lens of Joint Media Engagement (JME), this relationship between adults and children around the use of media can be examined. Stevens and Penuel (2010) say that JME applies to the mutual experiences of people using natural or design media together. JME can happen anytime and wherever there is contact between the media and multiple people. JME experiences can include watching, playing, searching, reading, and making, using digital media (ebooks, games, coding, etc.) or traditional media (books, radio, television, etc.) JME would make it easier for all participants to make sense of specific circumstances. For instance, parents and children watching television together, children involved in Minecraft as a group of friends are some examples of JME. Some researchers concentrated on home-based JME between parents and children (Penuel et al., 2009), while others concentrated on child-to-peer JME (Niemeyer and Gerber, 2015; Tissenbaum et al., 2017). Tiwari (2020) wrote an interactive children's e-book titled 'Q-Bot the Quarantine Robot’ which interacted via social media (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) in conjunction with parents and faculty. ILS Q-BOTO is the story of a 40-pin robot that was built to make people feel relaxed and happy during the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine. This story gives details on the best health and hygiene practices to prevent the capture of the virus.

Due to COVID-19, the imbalance of psycho-social wellbeing in children must be taken care of in a more cautious way than earlier. The caregivers should focus on not making the conversation scary or fear-based for the child. This can be done by using the concept of storytelling. They can ask children to create stories on the prevention of COVID-19 using their cartoon characters and do role plays. Caregivers and parents can weave stories about learning the difference between real and fake news. The caregivers can also work to restore the mental and emotional balance of children’s minds by “using mandalas.” Mandalas have a very hypnotic appeal in their circular form, which catches the attention and soothes the mind instantly. They mimic flower-like shapes in nature–and heals our minds because of spending time in natural surroundings. The use of mandalas has a beneficial impact on children’s well-being as their brain reacts to geometric form shifts. For children, mandalas and animals in combination can work well for restoring their harmony amidst this lockdown owing to the COVID-19 pandemic.

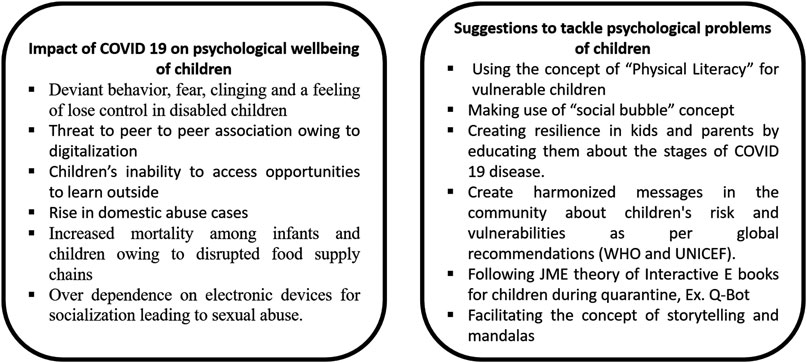

This paper offer insight into the current state of psychological health of children amidst COVID-19 (Figure 1). As societies move toward a new normal, with technology, remote working, and learning, caregivers and policymakers ought to adopt provisions to support families, regulate virtual platforms and fortify services as they work to safeguard children from all forms of violence. Caregivers and policymakers must build a strong response plan to tackle the psychological problems of pandemic affected children. The authors have presented the main findings of the paper in Figure 1. The authors have suggested that using the concept of “Physical literacy” through digital platforms for enhancing the physical activity of disabled children can work well. The paper also recommends caregivers to encourage more frequent communication with parents as well as children through e-books using the concept of JME. Moreover, caregivers should reduce the risk of segregation and stigmatization of COVID-19 by using positive language to communicate with children. Lastly, the authors showcased the importance of storytelling and mandalas for building the psychosocial wellbeing of children amidst the pandemic.

FIGURE 1. A breif pictorial representation of the psychological problems of children during COVID-19 and their remedical measures.

The study did not include any human participants. Therefore no review or approval was required from REVA University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

SC and TP contributed to the conception, structure of the paper, and interpretation of available literature. SC contributed to the development of the initial draft. TP reviewed and critiqued the output for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

BBC, (2020). How Covid-19 is changing the world’s children. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200603-how-covid-19-is-changing-the-worlds-children (Accessed June 4, 2020).

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Dev. 55, 83–96. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x

Block, L., and Block, A. (2020). Kelly stays home: the science of coronavirus, kelly stays home. Available at: www.kellystayshome.com (Accessed May 18, 2020).

Brian, A., De Meester, An., Klavina, A., Irwin, J., Taunton, S., Pennell, A., et al. (2019). Exploring children/adolescents with visual impairments’ physical literacy: a preliminary investigation of autonomous motivation. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 38 (2), 155–161. doi:10.1123/jtpe.2018-0194

Campbell, A. M. (2020). An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci. Int.: Report. 2, 100089. doi:10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089

Chaturvedi, S. (2020). Knowledge management initiatives for tackling COVID-19 in India. Knowledge management initiatives for tackling COVID-19 in India. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3731606 (Accessed November 16, 2020).

Chaturvedi, D. S., Gowda, K., Chowdari, L., Anjum, A., and Begum, A. (2020). Directive government policy and process for the people amidst COVID-19. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract3755221 (Accessed December 25, 2020). doi:10.2139/ssrn.3755221

Clark, H., Coll-Seck, A. M., Banerjee, A., Peterson, S., Dalglish, S. L., Ameratunga, S., et al. (2020). A future for the world's children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. Lancet 395 (10224), 605–658.

Coyne, L. W., Gould, E. R., Grimaldi, M., Wilson, K. G., Baffuto, G., and Biglan, A. (2020). First things first: parent psychological flexibility and self-compassion during COVID-19. Behav. Analyst Pract. 6, 1–7. doi:10.1007/s40617-020-00435-w

Dalton, L., Rapa, E., and Stein, A. (2020). Protecting the psychological health of children through effective communication about COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 4, 346–347. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30097-3

Dharmshaktu, N. S. (2020). The lessons learned from current ongoing pandemic public health crisis of COVID-19 and its management in India from various different angles, perspectives and way forward. Epidemiol. Int. (E-ISSN: 2455-7048). 5 (1), 1–4.

DiGiovanni, C., Conley, J., Chiu, D., and Zaborski, J. (2004). Factors influencing compliance with quarantine in Toronto during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Biosecur. Bioterror. 2 (4), 265–272. doi:10.1089/bsp.2004.2.265

Economic Times (2020). Lockdown in India has impacted 40 million internal migrants: world Bank. Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/lockdown-in-india-has-impacted-40-million-internal-migrants-world-bank/articleshow/75311966.cms (Accessed April 23, 2020).

Ghosh, R., Dubey, M. J., Chatterjee, S., and Dubey, S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on children: special focus on psychosocial aspect. Education 31, 34. doi:10.23736/S0026-4946.20.05887-9

Godin, M. (2020). As cities around the world go on lockdown, victims of domestic violence look for a way out. Available at: https://time.com/5803887/coronavirus-domestic-violence-victims/ (Accessed March 18, 2020).

Grechyna, D. (2020). Health threats associated with children lockdown in Spain during COVID-19. SSRN Electron. J. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3567670

Gupta, S. D. (2020). Ravaging pandemic of COVID-19. J. Health Manag. 22 (2), 115–116. doi:10.1177/0972063420951876

Idoiaga, N., Berasategi, N., Eiguren, A., and Picaza, M. (2020). Exploring children’s social and emotional representations of the Covid-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11, 1952. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01952

Jaspal, R., and Lopes, B. (2020). Psychological wellbeing facilitates accurate HIV risk appraisal in gay and bisexual men. Sexual Health 17 (3), 288–295.

Jiao, W., Wang, L., J., Fang, S., Jiao, F., Mantovani, M., et al. (2020). Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J. Pediatr. 211, 264–266. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013

Jiloha, R. C. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health. Epidemology International 5 (1), 7–9. doi:10.24321/2455.7048.202002

Khanna, A. (2020). Impact of migration of labour force due to global COVID-19 pandemic with reference to India. J. Health Manag. 22 (2), 181–191. doi:10.1177/0972063420935542

Kriellaars, D. J., Cairney, J., Bortoleto, M. C., Kiez, T. M., Dudley, D., and Aubertin, P. (2019). The impact of Circus arts instruction in physical education on the physical literacy of children in grades 4 and 5. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 38 (2), 162–170. doi:10.1123/jtpe.2018-0269

Kumar, S., Maheshwari, V., Prabhu, J., Prasanna, M., Jayalakshmi, P., Suganya, P., et al. (2020). Social economic impact of COVID-19 outbreak in India. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1108/IJPCC-06-2020-0053

Liu, W., Zhang, Q., Chen, J., Xiang, R., Song, H., Shu, S., et al. (2020). Detection of Covid-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. New Engl. J. Med. 382 (14), 1370–1371.

Long, N. J., Aikman, P. J., Appleton, N. S., Davies, S. G., Deckert, A., Holroyd, E., et al. (2020). Living in bubbles during the coronavirus pandemic: insights from New Zealand. London, United Kingdom: London School of Economics

Magnus, A., and Stasio, F. (2020). COVID-19 is creating another public health crisis: domestic violence. WUNC 91.5—North Carolina Public Radio. Available at: https://www.wunc.org/post/covid–19-creating-another-public-health-crisis-domestic-violence (Accessed April 21, 2020).

Mittal, S., and Singh, T. (2020). Gender based violence, Front. Glob. Women’s Health 1, 4. doi:10.3389/fgwh.2020.00004

Mukhtar, S. (2020). Pakistanis' mental health during the COVID-19. Asian J Psychiatr, 51, 102127. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102127

National Herald (2020). The pandemic era of no good choices. Available at: https://www.nationalheraldindia.com/india/the-pandemic-era-of-no-good-choices (Accessed September 15, 2020).

New York Times (2020). Nearly half of men say they do most of the home schooling. 3 percent of women agree. New York Times, A20, May, 8.

Niemeyer, D. J., and Gerber, H. R. (2015). Maker culture and Minecraft: implications for the future of learning. Educ. Media Int. 52 (3), 216–226. doi:10.1080/09523987.2015.1075103

NIMHANS (2020). Taking care of the mental health of the children during COVID-19 (2020). Bengaluru, India: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (Institute of National Importance).

Penuel, W. R., Riel, M., Krause, A., and Frank, K. A. (2009). Analyzing teachers’ professional interactions in a school as social capital: a social network approach. Teach. Coll. Rec. 111 (1), 124–163

Perez, S. (2020). Perez Kids now spend nearly as much time watching TikTok as YouTube in United States, United Kingdom and Spain TechCrunch. Available at: https://techcrunch.com/2020/06/04/kids-now-spend-nearly-as-much-time-watching-tiktok-as-youtube-in-u-s-u-k-and-spain/ (Accessed June 9, 2020).

Pinquart, M. (2017). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: an updated meta-analysis. Dev. Psychol. 53 (5), 873–932. doi:10.1037/dev0000295

Pohl, D., Alpous, A., Hamer, S., and Longmuir, P. E. (2019). Higher screen time, lower muscular endurance, and decreased agility limit the physical literacy of children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 90, 260–265. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.05.010

Readers Digest (2020). Coronavirus special issue. Available at: https://www.readersdigest.co.uk/lifestyle/technology/how-to-help-children-stay-safe-online (Accessed April 16, 2020).

Restubog, S. L. D., Ocampo, A. C. G., and Wang, L. (2020). Taking control amidst the chaos: emotion regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Vocat. Behav. 119, 103440.

Shahidi, S. H., Stewart Wouldiams, J., and Hassani, F. (2020). Physical activity during COVID-19 quarantine. Acta Paediatr. 109 (10), 2147–2148. doi:10.1111/apa.15420

Shen, K., and Yang, Y. (2020). Diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children: a pressing issue. World J Pediatr. 16, 219–221. doi:10.1007/s12519-020-00344-6

Simonovic, D. (2020). States must combat domestic violence in the context of COVID-19 lockdowns—United Kingdom rights expert. United nations office of the high commissioner for human rights. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25749&LangID=E (Accessed May 27, 2020).

Singh, S., Bhutani, S., and Fatima, H. (2020a). Surviving the stigma: lessons learnt for the prevention of COVID-19 stigma and its mental health impact. Ment. Health Soc. Inclusion 24 (3), 145–149. doi:10.1108/MHSI-05-2020-0030

Singh, S., Roy, M. D., Sinha, C. P. T. M. K., Parveen, C. P. T. M. S., Sharma, C. P. T. G., and Joshi, C. P. T. G. (2020b). Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: a narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatr. Res. 293, 113429. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429

Stevens, R., and Penuel, W. (2010). Studying and fostering learning through Joint media engagement, Principal Investigators Meeting of the National Science Foundation’s Science of Learning Centers. Arlington, VA, 1–75.

Sun, N., Wei, L., Shi, S., Jiao, D., Song, R., Ma, L., et al. (2020). A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Infect. Contr. 48 (6), 592–598. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018

The Guardian International Edition (2020). Lockdown and the Impact on the deaf children. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/jun/07/lockdown-and-the-impact-on-deaf-children (Accessed June 7, 2020).

The Hindu (2020). COVID-19 taking an emotional toll on children. Available at: https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/health/coronavirus-lockdown-covid-19-taking-an-emotional-toll-on-children/article31822539.ece (Accessed June 7, 2020).

The New Indian Express (2020). COVID-19 might push 120 mn children into poverty in South Asia, including India: UNICEF. Available at: https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/jun/23/covid-19-might-push-120-mn-children-into-poverty-in-south-asia-including-india-unicef-2160390.html (Accessed July 6, 2020).

The Tribune (2020). How thousands in China got infected by brucellosis in one single outbreak. Available at: https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/world/how-thousands-in-china-got-infected-by-brucellosis-in-one-single-outbreak-166901 (Accessed November 6, 2020).

The Wire (2020). COVID-19 lockdown lessons and the need to reconsider draft new education policy. Available at: https://thewire.in/education/covid-19-lockdown-lessons-and-the-need-to-reconsider-draft-new-education-policy (Accessed June 10, 2020).

Times of India (2020). 65% children became device addictive during lockdown, reveal study. Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/education/news/65-children-became-device-addictive-during-lockdown-reveals-study/articleshow/76784896.cms (Accessed July 4, 2020).

Tissenbaum, M., Berland, M., and Lyons, L. (2017). DCLM framework: understanding collaboration in open-ended tabletop learning environments. Inter. J. Comp.-Sup. Collab. Learn. 12 (1), 35–64. doi:10.1007/s11412-017-9249-7

Tiwari, S. (2020). Q-Bot, the Quarantine Robot: Joint-media engagement between children and adults about quarantine living experiences. Inform. Learn. Sci. 121, 401–409. doi:10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0075

UNESCO (2020). Adverse consequences of school closures. UNESCO. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/consequences (Accessed April 23, 2020).

UNICEF (2020). UNICEF estimates deaths of 8.8 lakh children due to COVID-19 in South Asia; maximum from India. The Statesman, A20, November, 19.

Whitehead, M. (2001). The concept of physical literacy. Eur. J. Phys. Educ. 6 (2), 127–138. doi:10.1080/1740898010060205

Women, U. N. (2020a). The shadow pandemic: violence against women and girls and COVID-19. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/issue-brief-covid–19-and-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls-infographic-en.pdf?la=en&vs=515 (Accessed October 1, 2020).

Women, U. N. (2020b). COVID-19 and ending violence against women and girls. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org//media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/issue-brief-covid-19-and-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls-en.pdf?la=en&vs=5006 (Accessed November 19, 2020).

Keywords: covid 19 (epidemics), children, psychosocial health and well-being, policymaker, caregivers’, vulnerable sections

Citation: Chaturvedi S and Pasipanodya TE (2021) A Perspective on Reprioritizing Children’s’ Wellbeing Amidst COVID-19: Implications for Policymakers and Caregivers. Front. Hum. Dyn 2:615865. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2020.615865

Received: 10 October 2020; Accepted: 17 December 2020;

Published: 29 January 2021.

Edited by:

Tushar Singh, Banaras Hindu University, IndiaReviewed by:

Vijyendra Pandey, Central University of Karnataka, IndiaCopyright © 2021 Chaturvedi and Pasipanodya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shakti Chaturvedi, c2hha3RpLmNoYXR1cnZlZGlAcmV2YS5lZHUuaW4=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.