- Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Sexual and gender minority youth are at risk for negative mental health outcomes, such as depression and suicide, due to stigma. Fortunately, sense of community, connection, and social support can ameliorate these deleterious effects. Youth express that most of their social support comes from peers and in-school organizations, but these sources require in-person interaction. Past research has identified social media sites as virtual and anonymous sources of support for these youth, but the role of YouTube specifically in this process has not been thoroughly explored. This study explores YouTube as a possible virtual source of support for sexual and gender minority youth by examining the ecological comments left on YouTube videos. A qualitative thematic analysis of YouTube comments resulted in six common themes in self-identified adolescents' YouTube comments: sharing, relating, information-seeking, gratitude, realization, and validation. Most commonly, adolescents shared feelings and experiences related to their identity, especially when they could relate to the experiences discussed in the videos. These young people also used their comments to ask for identity-related advice or information, treating the platform as a source of education. Results suggest that sexual minority youth's use of YouTube can be advantageous for social support and community, identity-related information, identity development, and overall well-being.

Introduction

Sexual and gender minority individuals are “individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, transgender, two-spirit, queer, and/or intersex…or who do not self-identify with one of these terms but whose sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or reproductive development is characterized by non-binary constructs of sexual orientation, gender, and/or sex” (NOT-O-19-139: Sexual Gender Minority Populations in NI-Supported Research., 2019). Put more simply, sexual and gender minorities are individuals who identify as anything other than straight or cisgender (someone whose gender identity matches their biological sex), or who engage in behavior outside of the gender or sexual binary (attraction and sexual activity between males and females). Sexual and gender minority youth are at risk for negative health outcomes. Youth with these identities are exposed to excess stress due to stigma (Meyer, 2003). In terms of sexual or gender minority identity, these stressors can include external experienced stressors such as explicit discrimination, anticipated stressors such as the expectation of rejection, or internal stressors such as internalized homophobia. Sexual and gender minority adolescents experience higher rates of both victimization and mental health symptoms than heterosexual peers, including depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and even suicide attempts (Meyer, 2003; Wright and Perry, 2006; Kelleher, 2009; Kann et al., 2016; Sattler et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2019).

Support, belongingness, and community are critical for adolescents exploring their identities as they are protective against these negative outcomes. For example, peer and social support increases sexual and gender minority youths' confidence and self-esteem (Romijnders et al., 2017) and protects against the common early and dangerous alcohol and drug use among these youth (Kidd et al., 2018). Sexual and gender minority youth report many positive influences on their well-being, including peers, schools, and sexual and gender minority community involvement (Higa et al., 2014; Porta et al., 2017). These social support systems can ameliorate the effects of identity-related stress on psychological functioning (Meyer, 2003). Social evaluation theory suggests that when those with stigmatized identities are connected with a community of others with whom they identify, they are able to compare themselves more to that group rather than to an out-group, allowing them to avoid negative comparison due to stigma and improve well-being (Pettigrew, 1967 as cited in Meyer, 2003). This research and theory illustrate the importance of connection to community. However, these supports require and provide in-person or face-to-face interaction.

There are situations in which adolescents may not have access to such in-person support and need another way to connect with a community. Formative research shows that sexual and gender minority youth say that they are often driven online by feelings of isolation, stigmatization, and a lack of information (Steinke et al., 2017). This may be truer now more than ever, since the last four years after the election of Donald Trump as president has brought a resurgence of outward homophobia and discrimination against sexual and gender minorities. The present research explores the possibility that specific Internet-based communities can be an additional resource to fulfill the ameliorative role of community, support, and interaction by examining the ecological online environment. This source of support can be especially important in the case of statistically infrequent identities (Suzuki and Beale, 2006; Sherman and Greenfield, 2013).

The Internet has shown to be an important part of identity development and support for sexual and gender minority individuals. In one 2011 study, participants described the Internet as the most influential media source influencing their sexual orientation identity development (Gomillion and Giuliano, 2011). Often, sexual and gender minority individuals are unable to find information about their identities in the ‘real' world, and therefore, turn to the Internet for information (Harper et al., 2016). In one study of gay and bisexual young men, participants expressed that the Internet fostered a connection to the gay community as well as facilitating the coming out process. The Internet also provides a certain level of anonymity to this process of identity exploration, allowing for individuals to express themselves freely and ask questions without risk of identification.

Even further, with the advent of sites that host user-generated content, like social media, the Internet landscape and its consumption have radically changed. In-depth interviews with sexual gender minority youth showed that they use social media to connect with others, express themselves, and access resources (Paceley et al., 2020). Social media are evolving at pace with evolving identities of young people (Bragg et al., 2018; Goldberg et al., 2020). Adolescents feel that they have more expansive and flexible definitions of their own identities, leading to more openness about pronouns, and acknowledgment of the fluid nature of gender and sexuality (Higa et al., 2014). This realization empowers young people to take control over their own identification and expression, but also perhaps renders traditional supports and interventions unable to adequately support the more diverse and expansive sexual and gender identities of youth. Fortunately, due to this ever-growing space, individuals are able to personalize their viewing and scrolling habits to seek out positive, reinforcing content about their identities. Research has shown that sexual and gender minority individuals sometimes turn to social media sites like Facebook to form relationships and community with those with common experiences, especially if they cannot find or access that type of support in person (Porta et al., 2017). The introduction of newer social media and user-generated content platforms has made it easier than ever to seek out such community. A 2017 study showed that the surveyed sexual and gender minority youth felt more comfortable communicating on social media rather than face-to-face, in order to eliminate the fear of discrimination or bullying (Lucero, 2017). Many sexual and gender minority youth express that the anonymity that some social media sites allow is a key factor in being able to explore and experience their identities (Fox and Ralston, 2016). They are able to detach from their offline lives and remove the risk of being exposed to their family and friends.

While a myriad of social media platforms are mentioned in previous studies on sexual and gender minority youth, YouTube stands out. YouTube is a video-sharing platform that allows users to upload, share, and comment on videos. For youth in general, the amount of time viewing video content on sites like YouTube has drastically increased (Rideout and Robb, 2019). From 2015 to 2019, the percentage of youth who say they watch online videos “every day” has more than doubled. Among 8- to 12-year-olds, daily video viewing has increased from 24 to 56%, and, among 13- to 18- year-olds, 34 to 69%.

YouTube is more than just a video hosting site; it is a platform “…at the intersection of media creation and social networking, providing young people a participatory culture in which to create and share original content while making new social connections” (Chau, 2010, p. 1). YouTube allows users to create their own content and consumers to seek out content that is relevant to them. This platform specifically is unique because its main purpose is facilitating the sharing of video content and can serve as an alternate form of media that is solely in the consumers control, contrasting in this respect with mainstream media. Although many sexual and gender minority individuals have found positive models in mainstream media, such as television and movies (Gomillion and Giuliano, 2011), younger sexual and gender minority adolescents believe that these mainstream representations of non-traditional sexuality and gender identities are limiting and less diverse than their actual identities (McInroy and Craig, 2017). Those who create their own videos often use this platform to express their identity (Chau, 2010). Research shows that YouTube is a place for those with minority identities to give advice and form community through creating and posting original videos. For example, many YouTube videos created by transgender people about trans-specific content discuss family, bullying, dating, and transitioning, and serve as guidance and education for transgender viewers (Miller, 2017). Several sexual and gender minority adolescents have mentioned that they subscribe to the YouTube channels of sexual and gender minority people to learn more about their identity-specific issues and experiences (Fox and Ralston, 2016). One transgender participant mentioned that YouTube was a key factor in coming to terms with his trans identity.

While the Internet and social media do provide an outlet for these adolescents, the dangers of the Internet cannot be discounted. Regulations on internet access, such as the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998, which determined that websites cannot collect any information on children under age 13, aim to protect young people from the potential dangers of the internet (Uhls et al., 2014). Even teens on the internet are vulnerable to cyberbullying, sexual solicitation, predators, and scams (The Most Common Threats Children Face Online, 2020; Internet Safety, n.d.). Sexual and gender minority teens in particular have had negative experiences on interactive media, including harassment through private messages or bullying on social media (Fox and Ralston, 2016) and non-heterosexual teens experience cyberbullying almost twice as much as their straight peers (Hinduja and Patchin, 2020). This situation requires an important conversation about whether the risks outweigh the benefits for young people, especially gender and sexual minority teens, using such social media. Our study will open a conversation on this issue.

Small scale YouTube creators, like vloggers (video bloggers), have previously made a distinction between their channels and commercial channels that are owned and operated by large professional media corporations (Rotman and Preece, 2010). They believe that their ability to interact and share their own experiences creates a sense of community. The ability of YouTube to provide realistic and peer-provided information on sexual and gender minority identities and experiences is advantageous, as these representations may actually impact young people more than seeing celebrity or mainstream media representations that lack authenticity (Gray, 2009). In fact, disclosure of sexual and gender minority identity actually prompts disclosure of the commenters identity, as well as leaving comments and “likes” (Doyle and Campbell, 2020). Research has revealed the motivations for those who create videos and post on YouTube. However, the motivations of viewers who consume this content have been less explored. Our research begins to fill in this gap.

The motivation for exploring how sexual and gender minority adolescents use media in relation to identity development and support lies in the fact that adolescence is an incredibly important and complex time for these processes. Adolescence is a time when many biological, psychological, and social factors develop and peak in intensity, leading to exploration and curiosity regarding sexuality (Kar et al., 2015). During this time, young people are also socialized to exhibit and conform to certain gendered behaviors (Kornienko et al., 2016), an expectation that can influence their gender identity. Because of the multifaceted nature of this identity development during such a critical time, determining effective forms of social support is crucial.

Although previous studies allude to the use of YouTube as a resource, the ecological conversation in YouTube comments has yet to be explored; and no studies have focused solely on YouTube. In other words, we know little about the process by which YouTube becomes a resource. A qualitative design is an appropriate methodology to explore this process because it allows us to develop a foundational understanding of how young people use this platform by examining their natural behavior. The analysis will paint a rich, in-depth, and ecologically valid picture of how a sample of adolescents responds to YouTube videos on sexual and gender minority topics. This analysis can then provide a foundation for future research that examines the generalizability of the findings through a quantitative research design.

Method

Materials

YouTube Videos

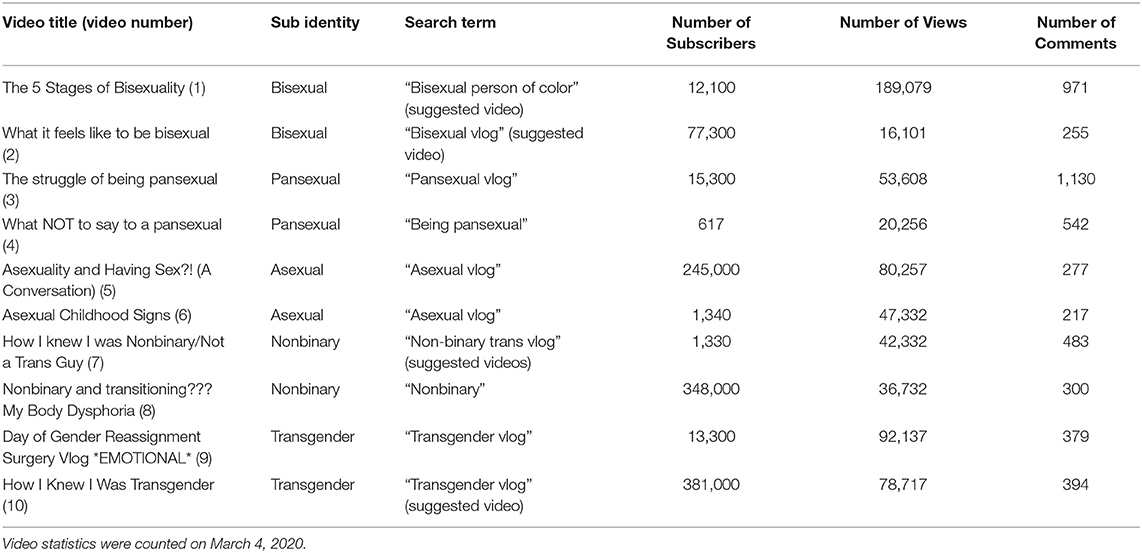

The first author created a brand-new YouTube account (to avoid any results based on existing algorithms) and searched for relevant videos with a variety of search terms such as “being pansexual” and “transgender vlogs” (see Table 1 for a list of video titles, search terms, and other information); there was no precedent for how to search for such videos in this context as previous studies are mostly self-report and interviews. Additionally, as the goal of qualitative research is to be formative and descriptive, these terms were utilized to result in a diverse selection of videos and topics. While the YouTube algorithm would not have existing history because the first author created a new account, it would eventually begin to curate content, resulting in very sexual and gender minority-focused results. To combat this, the first author did not choose videos based on their position in search results, but rather sifted through the results in order to create a sample of videos with a variety of sexual and gender minority-related topics. Videos included in the preliminary sample of videos resulted from these searches (chosen from the top of the results page, if possible, in order to find relatively popular videos) as well as videos provided by the YouTube algorithm as “suggested videos” on the site after using these search terms. The first author then viewed the videos, evaluating the content to meet the following five inclusion criterion:

(1) video must have been published after November 9, 2016, date of Donald Trump's election as President (to control for the culture shift of this time where outward discrimination of minorities, including sexual and gender minority individuals, increased)

(2) video must have elicited at least 100 comments

(3) video must have been created by an individual (such as a vlog [video blog] or personal video) and not by a professional company (such as Buzzfeed or Refinery 29)

(4) video must include the creator discussing their experience relating to their own sexual or gender minority identity

(5) creator must spend the whole video speaking about their experience (for example, a long video with the experience briefly mentioned in a shorter segment would not meet the inclusion criteria for inclusion in the sample).

Most of the chosen videos portrayed white video creators. At least three of the creators of videos used in this study explicitly stated in their YouTube profiles that they serve as an educational and supportive account for sexual and gender minority individuals:

“Hey everyone…I am 21 years old and agender. *THEY/THEM* This is an open community for people of all sexual orientations, romantic orientations, and gender identities. ♥ I make all kinds of different videos ranging anywhere from educational videos about different LGBTQ identities to vlogs of what's going on in my life and different things about me and things I've experienced through vlogs. I like to feature loads of other LGBTQ YouTubers and spread awareness and support throughout the LGBTQ community in order to unify us and help people feel welcome and valid!”

“Hi… An Aussie LGBTQ+ youtuber discussing new taboo topics every Monday and Friday!…On this channel you'll find LGBTQ+ issues, topics of taboo, general life advice,… and songs I create about important issues (on occasion)!”

“A channel devoted to bisexual empowerment, bisexuality and all things bisexual and mostly-straight, whether it's TV shows, movies, myths, tips for coming out or the latest scientific research.”

Five sub identities as video topics were included in this study: the sexual orientations of (1) bisexual, (2) pansexual, and (3) asexual, and the gender identities of (4) non-binary and (5) binary transgender. These identities were chosen in order to capture information about identities that are less represented in media and to understand diverse sexual orientations and gender identities (GLAAD, 2019). The final sample of videos includes two videos per sub-identity, with a sample size of 10 videos.

Sample

YouTube Comments

Next, all of the top-level comments left on these 10 videos (no replies to comments were included) were imported into MAXQDA 2020 software from YouTube on March 4, 2020. One thousand randomly selected comments (100 from each video) were included in the final sample to allow for a comprehensive analysis across a variety of identities and types of videos using the comment, not the person, as our unit of analysis. The remaining comments not included in the final sample served as items for coding scheme development. This sample was intended for a mixed-methods content analysis using MAXQDA 2020 to explore common themes in the comments section of YouTube videos. While the MAXQDA software package, in some iteration, has been a well-used program for 3 decades, it has evolved to accommodate the upload of social media data directly into the program from the Internet, making it an effective platform for the analysis of YouTube comments.

The overall sample of comments was searched for adolescent age-identifiers given within the comment in order to collect a sub-sample of comments written by self-identified adolescents. The codes assigned to them during the coding of the overall sample remained, and further analysis of more nuanced themes was conducted. Forty-three comments were written by self-identified teens and were the focus of the present qualitative analysis. However, the Findings section begins by situating these comments in the context of the total sample. The sample is meant to be looked at as a whole for sexual and gender minority identities, but will allow in a future quantitative paper, for analysis of differences between identities.

Coding Scheme Development

To develop a coding scheme, the first and third authors independently examined 50 different randomly selected comments (10 from each video, for a total of 100 comments) that were not to be included in the final sample. Some themes were derived deductively from existing literature and some were derived inductively from an exploration of said randomly selected comments. Researchers discussed themes they saw, operationalized the themes, and provided an exemplary quote for each theme. Then, researchers independently coded the same 50 randomly selected comments not included in the final sample (10 from each video) in order to establish 85% or higher inter-rater reliability. This process was repeated 3 times with newly selected comments in order to establish 85% inter-rater reliability. Throughout this process, the coding scheme was adjusted and pared down accordingly.

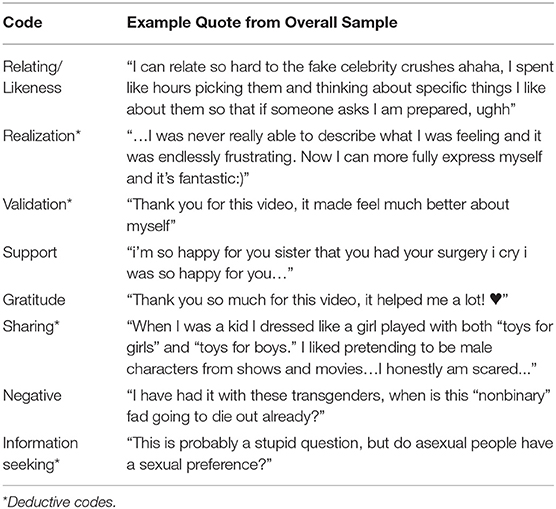

Table 2 presents the coding scheme. Note that all the coding categories had a positive valence except for one, which we called negative comments.

Coding

Once the final coding scheme was established, the first and third authors each independently coded the same 20% of the final sample (200 randomly selected comments) and reached an inter-rater reliability of 85.39% and a Kappa = 0.84, with eight individual Kappas ranging from 0.48 (moderate agreement; Landis and Koch, 1977) to 0.92 (almost perfect agreement; Landis and Koch, 1977). Finally, each researcher then independently coded half of the remaining final sample (400 comments each). Both coders were white, heterosexual females.

The overarching mixed-methods study (which included the adolescent-identified comments in the sample) did not involve contact with human subjects, and therefore, the Institutional Review Board did not require a board review. All comments used in the sample were public and in addition to most of the accounts themselves remaining anonymous, the identity of each commenter was kept anonymous by the lack of inclusion of any YouTube usernames in this paper. Any adolescent comments that mentioned age did not include other identifying information. Additionally, YouTube's Terms of Service includes comments as Content and explicitly states that users “grant each other user of the Service a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license to access your Content through the Service, and to use that Content (including to reproduce, distribute, modify, display, and perform it) only as enabled by a feature of the Service.”

Findings and Discussion

Overview and Quantitative Description

An analysis of the full sample of YouTube comments showed that there was a total of eight main themes found in the YouTube comments:

1. Sharing

2. Relating

3. Support for creators

4. Information seeking

5. Gratitude

6. Negative

7. Realization

8. Validation

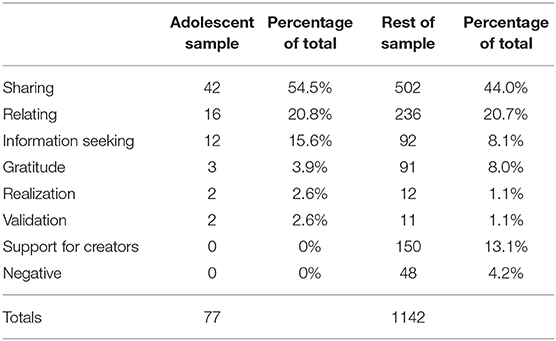

All but two themes (Negative and Support for creators) were found in the smaller, adolescent subsample. In both the subsample of self-identified adolescent comments and the remaining comments, sharing and relating were the most common themes identified and the most common pair of themes found together in the same comment. In this self-identified adolescent sample, we see all but two of these main themes from the overall coding scheme (see Table 3). Table 3 also shows that the rank order of mention for the subsample of comments for which the writer self-identified as adolescent matches the rest of our larger sample with two exceptions: negativity and support for creators. Because negative comments have important psychological meaning, this difference is discussed in the limitations section.

More nuanced themes and patterns that reflect the writers' lived experience are presented in the Qualitative Analysis section, which follows. See Table 1 for video numbers referenced as sources of quotes in the next section.

Qualitative Analysis

Theme: Sharing

Commenters frequently shared their identity-based experiences, both positive and negative, in their comments. Sharing was the most common theme in the sub-sample, identified in 41 of the 43 comments. This opportunity to connect and share with a community that has gone through similar experiences or struggles is advantageous. It is likely not an opportunity that many adolescents have, in person or within their own communities, especially if they live in geographic areas that do not have a large population of “out” sexual and gender minority people, or if they live with family and friends who are anti-sexual/gender minority.

Sometimes young people may just need a safe (i.e., anonymous) space to express their struggles, especially since concealing their identities can be harmful for their mental health (Meyer, 2003). This comment left by a twelve-year-old exemplifies this need to share what they are feeling:

“I've been struggling with my sexuality for a year and a half probably (tho I've kinda always known I was different), I'm 12…” (video 2)

Additionally, adolescents may have positive milestones they would like to share about their identity development, as evidenced by this 16-year-old's comment:

“…i have alot of fear of what i am and i spent alot of my live really hating myself for it but im slowly starting to want to embrace it” (video 1)

For some, the comments that adolescents leave on these YouTube videos could be the first time they admit that they are struggling with their sexuality or gender identity. This is illustrated by a comment by one 11-year-old:

“I'm 11 years old and I think I may be asexual... for about 1 and a half years I am struggling to know if I'm asexual lesbian or straight.” (video 6)

Several adolescents specifically shared their struggles of being torn between their identity and the beliefs of their families. Homophobic family members present a unique challenge for young individuals vs. adults, as they are likely living with these family members and depending on them to meet their basic needs. They may be scared to come out to their families for fear of rejection or even punishment (Aranmolate et al., 2017). This collective hardship that sexual and gender minority youth face may prompt adolescents to share their struggles with others who may have experienced the same thing in hopes of making connections and getting advice for how to proceed. The anticipation of their families and parents not accepting their identities could prompt teens to form another community so they feel a sense of belonging that they do not have at home. This need for kinship is illustrated by the concept of “chosen family,” a common social grouping in the lives of sexual and gender minority individuals, made up of friends, because of the lack of support from their family of origin (Hull and Ortyl, 2019).

The fear of abandonment can keep a young person from living their full identity and also cause negative health outcomes (Ryan et al., 2009). A bisexual high schooler said:

“i live with my mother who i know would not be accepting of it at all and the fact that i cant come out to my family makes it very hard for me to want to come out to anyone else…” (video 1)

Another bisexual teen said:

“I'm nervous. My parents don't support pride, bisexuals, gays, lesbians, etc. I don't know what to do...I'm a bi teen…I'm so scared to tell my family and very close friends. I'm not gonna tell them at all.” (video 1)

One 17 year old described their experience of this type of rejection:

“My mom kinda understands but I'm concerned she views me in the same way. The rest of my family has practically abandoned me” (video 10)

Psychological stress relating to sexual identity can lead to negative mental health outcomes like depression, self-harm, and suicide (Aranmolate et al., 2017). Having a space to share with and learn from like-minded or like-identity people could improve well-being and reduce the risk for these negative outcomes. Some adolescents expressed that simply viewing these YouTube videos helped them feel better and, in some cases, saved their lives. One 16-year-old reflected on their experience learning to accept themselves and the role that YouTube played in that process:

“Three years ago. I had just come to terms with being transgender. I was 13. I spent an entire night watching all your videos. I slept through my alarm and missed the bus for school the next day. But at least I knew that I would be okay.” (video 10)

A 14-year-old explained how watching YouTube videos possibly saved their life:

“Watching your videos gave me the want to come out, it gave me hope for the future because as a small thirteen-year-old, I didn't think I would live to graduate high school.” (video 10)

Theme: Relating

Another type of sharing that adolescents engaged in was relating. In these comments, the writer directly addressed and related to a specific concept or experience from the video rather than just sharing their general experience. This was the second most common theme in the adolescent sample. Relating to both difficult and positive experiences that they see in the videos can help them feel like they belong. Feeling the connection of going through a similar event or having similar thoughts could allow a young person to feel better about their situation. In response to an asexual creator explaining how they always felt the need to fit in and pretend to act like everyone else when they were young, an 18-year-old related:

“I'm 18 and I still feel the need to be like everyone else… I hope one day I actually do come to terms with my sexuality, and stop pretending…” (video 6)

One bisexual creator discussed that some of her friends told her that her bisexuality was just a phase and how she had to explain that it wasn't. A 13-year-old says that they had a similar experience:

“I'm 13 and just came out as bi… someone at school said it was a phase and I said “Yeah what phase lasts 13 years, I mean, other than your stupidity”…” (video 2)

Theme: Information-Seeking

Along with learning from these videos, many adolescents explicitly asked questions or for advice based on the content in the video. Information-seeking was the third most common theme in the adolescent sample. Sexuality or gender-identity related information, that they may not be able to get from other sources, could promote both physical and mental well-being for adolescents. Some young people may not know any other sexual and gender minority individuals and therefore don't have anyone they can ask these questions to personally. YouTube creates a space for sexual and gender minority youth to access videos that address these issues and ask questions to those with similar identities. Three teens (12, 13, and “teen,” respectively) asked questions about how to know what their identity might be:

“Do you think that 13 is too young to know if you are asexual?” (video 6)

“Is 12 too young to be ace/aro? I feel like around this time people are really starting to understand more and grow up, but I feel like people will judge me for being ace and aro at this age.. What do you think?” (video 6)

“i have a question: so i'm a closeted teen, who is also bisexual. i have a crush on this girl, and like i'm not fully gay. but i recently had a boyfriend a few months ago, but i'm not fully straight. how does that work? am i gay if i have a girlfriend? or am i straight if i have a boyfriend? or am i just in a gay/straight relationship. being bisexual is definitely so confusing!” (video 2)

Video creators that show that there is the opportunity to thrive after overcoming what many sexual and gender minority adolescents themselves are currently afraid of can ease anxiety and create an environment where young people can ask questions they are typically afraid to ask. This can reduce worry and promote wellbeing. One young trans teen expressed that they were scared to come out to their family and asked for advice on how to do so:

“How do you come out as trans to your parents and you're a young teen?:D I really need help with this, I'm just terrified.” (video 10)

Theme: Gratitude

These adolescents often expressed gratitude to the video creator in their comments. Sometimes the gratitude was just for making the video, but other times it was explicitly thanking the creator for helping them in general, without specifying how exactly the creator helped. However, the commenters often shared hardships that they went through prior to expressing gratitude in their comments, which suggests resolution after watching the video. Here, a 13-year-old illustrates this gratitude:

“I am 13, I was also confused about my gender but you helped me!!!” (video 10)

Theme: Realization and Validation

Adolescents expressed that sometimes watching these YouTube creators talk about their own sexual and gender minority identity helped them in a more specific way, by helping to put a name to their identity or clarifying their feelings, as well as helping the adolescent feel good about their identity. Those who are unsure of their identity actually experience similar amounts of discrimination and mental health symptoms as sexual and gender minority-identifying adolescents (Kann et al., 2016). Additionally, an adolescent who discovers a community of similarly-identifying individuals who share similar feelings and experiences can gain a sense of belonging. A transgender 14-year-old spoke directly to the YouTube creator when describing how the process of realizing that they were transgender from watching the creator's video was “alleviating”:

“I found your video from Buzzfeed and that was so revolutionary for me. I had been going through a spill of trying to figure out my sexuality because I didn't know you could have a gender identity, I thought that what you were born as was what your gender was and trying to figure out my sexuality was alleviating... in a way…The whole day I kept thinking about that video and I remember when I finally realized why I was freaking out about that video so much. I finally realized that I am transgender…” (video 10)

Another commenter relayed this powerful account of the moment they realized that they were bisexual as a teen.

“…my realization moment was the moment I had a word for it. it was the summer before seventh grade and I was watching a YouTube video of someone coming out as bisexual. they explained what it was and what it meant to be bisexual and it hit me like a ton of bricks” (video 1)

A bisexual 11-year-old shows that watching these YouTube videos can both lead to discovery as well as acceptance of oneself:

“Thank you so much, you have helped me discover my sexuality and taught me to be me and to love myself!” (video 2)

Conclusions and Implications

This ecological conversation in the form of YouTube comments corroborates previous self-report evidence that young people use YouTube to form community and assist with identity development (Fox and Ralston, 2016). These new results give us insight about how to support adolescents who are exploring their sexual and gender identities; their comments imply that these teens are looking for information and community. Wuest (2014, p. 31) captures this idea by saying,

“…the use of YouTube…remains significant in its reflection of wider issues of queer youth's place in the mainstream, through understanding the support structures that queer youth build for themselves in a community of like-minded peers can help make clear what potential there is in mainstream culture, and specific need to be addressed within this…”

The ability to focus on adolescent comments on YouTube is a rare one. Because of the nature of YouTube, one is not able to access the demographic information of a user, unless the user volunteers that information either on their account profile or in their comment. Fortunately, many of the adolescents included their ages in their comments and allowed us to analyze an adolescent sample. It may seem surprising that this sample included many 11-and-12-year-old commenters, while YouTube terms of service require a user to be at least 13 years of age. However, in 2014, 23% of children under 13 reported having a social media site (Uhls et al., 2014). The presence of 11- and 12-year-olds in this sample implies that feelings and concerns about possibly having a sexual or gender minority identity often start quite young.

These results also suggest the importance of websites that promote user-generated content and community, especially during situations and times when in-person supports are not available. While this sample of comments was left before the onset of the current COVID-19 pandemic, this opportunity to connect online may be even more important during current times when COVID-19 has forced many adolescents out of school and into a more isolated environment, perhaps with unsupportive families and challenging home lives. These new circumstances could lead to a loss of in-person supports such as Gay Straight Alliance clubs or school counselors; they may be able to be replaced with less formal virtual supports such as YouTube communities.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations exist within this study. The comments included in this analysis were limited to comments in which adolescents self-identified as such. Other teens may have commented on the videos, and expressed other themes, but we cannot identify them due to their lack of self-identification. Since we do not have official demographic information about these commenters and the Internet allows for anonymous activity, one concern would be that those who self-identified as adolescents may not be truthful about their ages. However, research shows that teens who lie about their ages on the internet often portray their age as older (Madden et al., 2013), so it is unlikely that teens would portray their ages as younger in these YouTube comments. Additionally, this concern about self-reported age is no different from accepted survey methodology in which respondents are given anonymity and self-report their age.

Because this is a small sample size, common in qualitative research, we are not able to generalize these results to all sexual and gender minority adolescents. However, we also have no reason to believe that our sample is not representative. And indeed, the dominant themes closely resemble the thematic foci of the rest of the sample.

The most psychologically important difference is the absence of negative comments in the adolescent sample, alongside their presence in the sample as a whole. One hypothesis concerning the lack of negative comments in the adolescent sample is that, because of the social change regarding views about the sexual and gender minority community, individuals in this younger generation are more accepting and tolerant of sexual and gender minorities because they were raised during a time where these identities, and for example, same-sex marriage, are accepted (A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States, 2020), or even ordinary. However, another possibility is that youth who identify themselves in comments feel more supported by the content. A future study in which the unit of analysis is participant rather than comment will be able to decide between these interpretations.

We do not know whether there are comments in the sample written by adolescents who did not mention their age. Nonetheless, the presence of negative comments anywhere in the comment population can be read by others. This situation leads us to conclude that adolescents can be exposed to negative comments about alternative gender and sexual identities when and if they read what others write. However, negative comments are very much in the minority, even where the age of the writer is unknown. Future research, using either survey or experimental methodology, can explore the psychological impacts of a small number of negative comments, as well as the psychological impacts of a large number of positive comments.

Regarding intersectionality, the creators in the videos chosen for this study, as well as the coders, lack diverse representation. Most of the creators in the videos were white, which could limit the diversity in the viewers and commenters, leading to results that are skewed by race or ethnic identity. Additionally, the two researchers who coded the YouTube comments both identify as cisgender (those who feel their gender matches their biological sex) women. Because the coders do not identify with the communities on which this study is based, there are certain nuances that were likely missed during the coding process.

These limitations are expected because of the nature of the data and methodology, but these qualitative results serve as a starting point for further exploration of online communities of youth. Quantitative studies with larger sample sizes will be more generalizable and representative and can build on the foundation of these qualitative results. Future research should have sexual and gender minority youth play a part in the research, with involvement from researchers belonging to the sexual and gender minority community, in order to explore the culture of the online sexual and gender minority community more deeply. Using a sample of sexually-, gender-, and racially-diverse youth in which researchers can identify all of those factors can provide a rich and intersectional account of how and why such online communities exist.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

JL was responsible for study conception, data collection, coding scheme development, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript drafting and preparation. PG was responsible for study conception, reliability processes, and manuscript editing and feedback. JS was responsible for coding scheme development, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript drafting and preparation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Yalda T. Uhls for the contribution of expertise in media and adolescents in designing and conducting this study.

References

A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States (2020). Georgetown Law. Available online at: https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=592919andp=4182201

Aranmolate, R., Bogan, D., Hoard, T., and Mawson, A. (2017). Suicide risk factors among LGBTQ youth: review. In JSM Schizophren. 2:2.

Bragg, S., Renold, E., Ringrose, J., and Jackson, C. (2018). ‘More than boy, girl, male, female': exploring young people's views on gender diversity within and beyond school contexts. Sex Educ. 18, 420–434. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2018.1439373

Chau, C. (2010). YouTube as a participatory culture. New Direct Youth Dev. 2010, 65–74. doi: 10.1002/yd.376

Doyle, P. C., and Campbell, W. K. (2020). Linguistic markers of self-disclosure: using YouTube coming out videos to study disclosure language. PsyArXiv [Preprint]. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Fox, J., and Ralston, R. (2016). Queer identity online: Informal learning and teaching experiences of LGBTQ individuals on social media. Comp. Hum. Behav. 65, 635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.009

Goldberg, S. K., Rothblum, E. D., Russell, S. T., and Meyer, I. H. (2020). Exploring the Q in LGBTQ: demographic characteristic and sexuality of queer people in a U.S. representative sample of sexual minorities. Psychol. Sex. Orient. Gender Divers. 7, 101–112. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000359

Gomillion, S. C., and Giuliano, T. A. (2011). The influence of media role models on gay, lesbian, and bisexual identity. J. Homosex. 58, 330–354. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.546729

Gray, M. L. (2009). Negotiating identities/queering desires: coming out online and the remediation of the coming-out story. J. Comp. Med. Commun. 14, 1162–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01485.x

Harper, G. W., Serrano, P. A., Bruce, D., and Bauermeister, J. A. (2016). The internet's multiple roles in facilitating the sexual orientation identity development of gay and bisexual male adolescents. Am. J. Men's Health 10, 359–376. doi: 10.1177/1557988314566227

Higa, D., Hoppe, M. J., Lindhorst, T., Mincer, S., Beadnell, B., Morrison, D. M., et al. (2014). Negative and positive factors associated with the well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth. Youth Soc. 46, 663–687. doi: 10.1177/0044118X12449630

Hinduja, S., and Patchin, J. W. (2020). Bullying, Cyberbullying, and Sexual Orientation/Gender Identity. Cyberbullying Research Center. Available online at: cyberbullying.org

Hull, K. E., and Ortyl, T. A. (2019). Conventional and cutting-edge: definitions of family in LGBT communities. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 16, 31–43. doi: 10.1007/s13178-018-0324-2

Internet Safety (n.d.). Common Sense Education. Available online at: https://www.commonsense.org/education/digital-citizenship/internet-safety (accessed 2020).

Kann, L., O'Malley Olson, E., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., et al. (2016). Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9-12 - United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR Surveil. Summ. 65, 1–202. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1

Kar, S., Choudhury, A., and Singh, A. (2015). Understanding normal development of adolescent sexuality: a bumpy ride. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 8, 70–74. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.158594

Kelleher, C. (2009). Minority stress and health: Implications for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people. Counsell. Psychol. Q. 22, 373–379. doi: 10.1080/09515070903334995

Kidd, J. D., Jackman, K. B., Wolff, M., Veldhuis, C. B., and Hughes, T. L. (2018). Risk and protective factors for substance use among sexual and gender minority youth: a scoping review. Curr. Addic. Rep. 5, 158–173. doi: 10.1007/s40429-018-0196-9

Kornienko, O., Santos, C. E., Martin, C. L., and Granger, K. L. (2016). Peer influence on gender identity development in adolescence. Dev. Psychol. 52, 1578–1592. doi: 10.1037/dev0000200

Landis, J. R., and Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159. doi: 10.2307/2529310

Lucero, L. (2017). Safe spaces in online places: social media and LGBTQ youth. Multicult. Educ. Rev. 9, 117–128. doi: 10.1080/2005615X.2017.1313482

Madden, M., Lenhart, A., Cortesi, S., Urs, G., Maeve, D., Smith, A., et al. (2013). Teens, Social Media, and Privacy. Available online at: http://www.lateledipenelope.it/public/52dff2e35b812.pdf

McInroy, L. B., and Craig, S. L. (2017). Perspectives of LGBTQ emerging adults on the depiction and impact of LGBTQ media representation. J. Youth Stud. 20, 32–46. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2016.1184243

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 129, 674–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Miller, B. (2017). YouTube as educator: a content analysis of issues, themes, and the educational value of transgender-created online videos. Soc. Med. Soc. 3:205630511771627. doi: 10.1177/2056305117716271

NOT-O-19-139: Sexual and Gender Minority Populations in NI-Supported Research. (2019). Available online at: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-19-139.html

Paceley, M. S., Goffnett, J., Sanders, L., and Gadd-Nelson, J. (2020). “Sometimes You Get Married on Facebook”: the use of social media among nonmetropolitan sexual and gender minority youth. J. Homosex. 2020, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2020.1813508

Pettigrew, T. F. (1967). “Social evaluation theory: convergences and applications,” in Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, ed D. Levine (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), 241–304.

Porta, C. M., Singer, E., Mehus, C. J., Gower, A. L., Saewyc, E., Fredkove, W., et al. (2017). LGBTQ youth' s views on gay-straight alliances : building community, providing gateways, and representing safety. J. School Health 87, 489–497. doi: 10.1111/josh.12517

Romijnders, K. A., Wilkerson, J. M., Crutzen, R., Kok, G., Bauldry, J., and Lawler, S. M. (2017). Strengthening social ties to increase confidence and self-esteem among sexual and gender minority youth. Health Prom. Prac. 18, 341–347. doi: 10.1177/1524839917690335

Rotman, D., and Preece, J. (2010). The “WeTube” in youTube - Creating an online community through video sharing. Int. J. Web Based Commun. 6, 317–333. doi: 10.1504/IJWBC.2010.033755

Ryan, C., Huebner, D., Diaz, R. M., and Sanchez, J. (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics 123, 346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524

Sattler, F. A., Zeyen, J., and Christiansen, H. (2017). Does sexual identity stress mediate the association between sexual identity and mental health? Psychol. Sex. Orien. Gender Div. 4, 296–303. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000232

Sherman, L. E., and Greenfield, P. M. (2013). Forging friendship, soliciting support: A mixed-method examination of message boards for pregnant teens and teen mothers. Comp. Hum. Behav. 29, 75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.018

Steinke, J., Root-Bowman, M., Estabrook, S., Levine, D. S., and Kantor, L. M. (2017). Meeting the needs of sexual and gender minority youth: formative research on potential digital health interventions. J. Adolesc. Health 60, 541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.11.023

Suzuki, L. K., and Beale, I. L. (2006). Personal Web home pages of adolescents with cancer: Self-presentation, information dissemination, and interpersonal connection. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 23, 152–161. doi: 10.1177/1043454206287301

The Most Common Threats Children Face Online (2020). Norton. Available online at: https://us.norton.com/internetsecurity-kids-safety-the-most-common-threats-children-face-online.html

Uhls, Y. T., Zgourou, E., and Greenfield, P. (2014). 21st century media, fame, and other future aspirations: a national survey of 9–15 year olds. Cyberpsychology. 8:4. doi: 10.5817/CP2014-4-5

Watson, R. J., Fish, J. N., Poteat, V. P., and Rathus, T. (2019). Sexual and gender minority youth alcohol use: within-group differences in associations with internalized stigma and victimization. J. Youth Adolesc. 48, 2403–2417. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01130-y

Wright, E. R., and Perry, B. L. (2006). Sexual identity distress, social support, and the health of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. J. Homosex. 51, 81–110. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n01_05

Keywords: connectedness, LGBTQ, YouTube, adolescence, gender identity, sexual orientation, sexual and gender minority, social support

Citation: Levinson JA, Greenfield PM and Signorelli JC (2020) A Qualitative Analysis of Adolescent Responses to YouTube Videos Portraying Sexual and Gender Minority Experiences: Belonging, Community, and Information Seeking. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2:598886. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2020.598886

Received: 25 August 2020; Accepted: 27 October 2020;

Published: 20 November 2020.

Edited by:

ZhiMin Xiao, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

Tyler Hatchel, University of Florida, United StatesLauren Stentiford, University of Exeter, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Levinson, Greenfield and Signorelli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jordan A. Levinson, am9yZGFubGV2QGcudWNsYS5lZHU=

Jordan A. Levinson

Jordan A. Levinson Patricia M. Greenfield

Patricia M. Greenfield Jenna C. Signorelli

Jenna C. Signorelli