- 1National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare, MedStar Health Research Institute, Washington, DC, United States

- 2Department of Emergency Medicine, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, United States

- 3Implementation Science, Healthcare Delivery Research Program, MedStar Health Research Institute, Hyattsville, MD, United States

- 4National Committee for Quality Assurance, Washington, DC, United States

- 5Maryland Primary Care Program, Maryland Department of Health, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 6Department of Oncology, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, United States

Background: Social needs screening can help modify care delivery to meet patient needs and address non-medical barriers to optimal health. However, there is a need to understand how factors that exist at multiple levels of the healthcare ecosystem influence the collection of these data in primary care settings.

Methods: We conducted 20 semi-structured interviews involving healthcare providers and primary care clinic staff who represented 16 primary care practices. Interviews focused on barriers and facilitators to awareness of and assistance for patients' social needs in primary care settings in Maryland. The interviews were coded to abstract themes highlighting barriers and facilitators to conducting social needs screening. The themes were organized through an inductive approach using the socio-ecological model delineating individual-, clinic-, and system-level barriers and facilitators to identifying and addressing patients' social needs.

Results: We identified several individual barriers to awareness, including patient stigma about verbalizing social needs, provider frustration at eliciting needs they were unable to address, and provider unfamiliarity with community-based resources to address social needs. Clinic-level barriers to awareness included limited appointment times and connecting patients to appropriate community-based organizations. System-level barriers to awareness included navigating documentation challenges on the electronic health record.

Conclusions: Overcoming barriers to effective screening for social needs in primary care requires not only practice- and provider-level process change but also an alignment of community resources and advocacy of policies to redistribute community assets to address social needs.

Introduction

Upstream social determinants of health (SDOH), including economic stability, education access, and the neighborhood and built environment, shape individual-level social risk factors such as unemployment, housing insecurity, and insurance status. Clinical care explains only 10%–20% of health outcomes, while the remaining 80%–90% is explained by other factors including SDOH and the downstream effects on individual circumstances (1–5). In 2019, the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) published a report outlining five strategies aimed at improving the integration of patients’ social needs (i.e., social risk factors for which a patient wants assistance) into clinical care delivery (1). Awareness about social needs can encourage adjustments in individual patient care, assist in addressing unmet needs, and, on a larger scale, align community structures to address unmet social needs within the community and advocate for policies aimed at redistributing community assets to address these social needs (2). A socio-ecological systems approach can help illustrate factors at different levels of the system in which social needs are elicited. These include the individual provider and patient level, the clinic or healthcare facility in which care activities occur, and the larger socio-technical infrastructure that shapes healthcare delivery (6–8).

Awareness of patients’ social needs is important in primary care where providers and patients maintain ongoing relationships for preventing and managing chronic diseases and preventing unnecessary health complications or hospitalizations (9–11). However, implementation of social needs screening can be complex, even for practices or providers who recognize the importance of such programs. Previous research on this topic has highlighted many of these complexities that exist at different levels of the socio-ecological system of screening for and addressing social needs. These complexities exist across various roles within the medical system, including mixed responses by patients and clinicians about who should conduct social needs screening (12–14). Complexities also exist at the clinic level, including the frequency with which screening must be conducted, and at the larger healthcare system level, including data privacy, and how this information should interface with electronic health records (EHRs) (13–18). However, there is a need to improve our understanding of patient and provider preferences for social needs screening in primary care settings and how different levels of the socio-ecological system interact with each other to impact the process of social needs screening.

National bodies in the United States such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have invested in large-scale programs to deliver and measure the impact of social risk factor screening through the Accountable Health Communities project, and the US Preventive Services Task Force has summarized the variation in practices across settings; however, there has been no national consensus about the ideal screening tools or delivery process (19, 20). Some professional groups have begun to tackle this issue, with social needs screening institutionalized in programs such as the Bright Futures program of the American Academy of Pediatrics, while other professional groups such as the American Academy of Family Medicine developed a screening tool to encourage screening while simultaneously suggesting more research on the impact of delivering screening and referral (21).

This study aimed to apply a socio-ecological model and use qualitative techniques to identify and understand barriers and facilitators in awareness about social needs, adjustment of practice to accommodate social needs, and assistance to address unmet needs across a diverse set of primary care practices in Maryland participating in a voluntary healthcare transformation initiative (6–8).

Materials and methods

Conceptual model

The socio-ecological model includes nested levels (6–8). The innermost level includes individual-level stakeholders in healthcare, including clinicians, healthcare staff such as clinic administrators and medical assistants, and patients. The individual is nested within the higher level of the clinic, comprising clinic-specific factors. The healthcare ecosystem is the largest level comprising healthcare practices and the communities they are embedded in, health information technology systems, and federal- and local-level healthcare governing bodies.

Setting

The Maryland Primary Care Program (MDPCP) is a voluntary program created by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that aims to support healthcare transformation for eligible Maryland primary care practices (22). In 2019, the MDPCP practices could choose one of two tracks. Track 1, the entry-level track that was phased out at the end of 2023, utilizes the fee-for-service model in addition to non-claims based program payments. Track 2, or the advanced track, provides higher levels of Track 1 payments and additional compensation through hybrid non-claims based and fee-for-service comprehensive primary care payments. Beginning in 2022, practices could transition to Track 3, which builds on the care delivery and performance requirements of Track 2 with enhanced financial risk for practice payments. Also beginning in 2022, MDPCP began funding the Health Equity Advancement Resource and Transformation (HEART) payment program to support providers in addressing patients' social needs (23). The practices participating in the advanced tracks are required to screen at least some of their patients for social needs and were the focus of data collection.

Participant characteristics

We created a purposive sampling pool of 75 primary care practices for recruitment from a list of 507 MDPCP participating practices in Maryland to balance practice characteristics by (1) electronic EHR platform, (2) county, (3) Care Transformation Organization affiliation (yes/no), and (4) Track (an MDPCP classification based on criteria about services offered to beneficiaries). We selected practices to balance these characteristics proportionately (e.g., if 10% of practices in MDPCP came from a specific county, we tried to target 10% from that county in our interview sample). From this list of 75 primary care practices, we emailed contacts provided by the Maryland Department of Health to recruit practices and conducted interviews until we reached thematic saturation. In total, we included up to two representatives from 16 practices to participate in semi-structured interviews, resulting in 24 participants (four interviews included two representatives from a single practice).

Data collection

All methods were implemented in accordance with guidelines and regulations outlined in the Georgetown-MedStar Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Protocol 4986). The interview guide was developed by researchers with expertise in social risk factor screening, quality improvement, and implementation science and modified with feedback from subject matter experts in public health and primary care (see Supplementary Material for interview guide). The interview explored current workflows for social needs screening, including clinicians and healthcare staff involved in screening, training to support social needs screening, use of screening tools, challenges in conducting screening, screening documentation, and ideal screening workflows.

We conducted virtual, semi-structured interviews via a HIPAA-compliant platform (Microsoft Teams). Interviews were led by a researcher with a master's (CS, female) or doctorate (BB, male) training in public health and skilled in qualitative research and human subjects’ compliance. Interviews also included a notetaker for documenting field notes during the interview. Data collection began after verbal informed consent was obtained for participation and audio and video recording. Interviews lasted approximately an hour. The participants received a $75 gift card.

Analysis

Interviews were audio and video recorded and transcribed automatically through Microsoft Teams, with quality control review by a member of the research team. Data were coded using a deductive approach using Dedoose coding software (24). A researcher with advanced training in human factors engineering (SK) developed the interview codebook using grounded theory to identify barriers and facilitators around eliciting social needs (25). Three researchers (SK, AM, HA) tested the codebook by coding the same interview independently before jointly reviewing the codes. Coding discrepancies were adjudicated through consensus, and the modified codebook was applied to five additional transcripts to confirm the codebook and establish coding reliability. The remaining interviews were divided between three researchers and coded by individual researchers. An inductive approach was used to abstract themes from participant quotes within codes and summarize key ideas. SK then organized sub-themes into the socio-ecological model and mapped them to the NASEM stages of awareness and assistance (1, 6–8).

Results

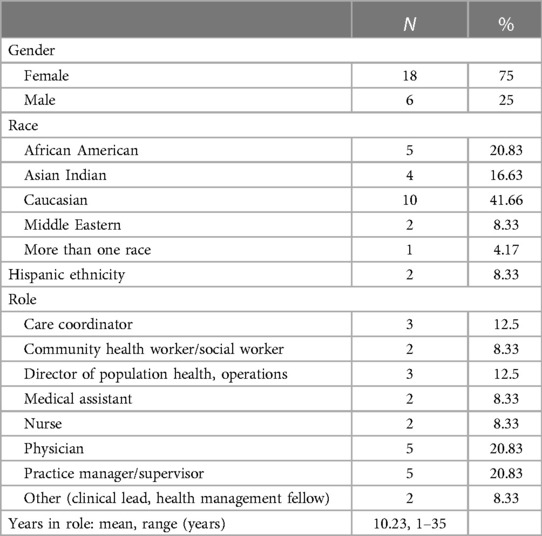

Table 1 shows the participant demographics. Interview participants represented at least 16 counties in Maryland (n = 3 practices each from Baltimore, Carroll, and Worcester; n = 2 practices each from Allegany, Anne Arundel, Calvert, Frederick, and Montgomery; n = 1 practice each from Dorchester, Harford, Howard, Prince George, St. Mary, Somerset, Wicomico, and unknown). Practice sizes ranged from very small to very large (1–45 providers; mean providers = 10).

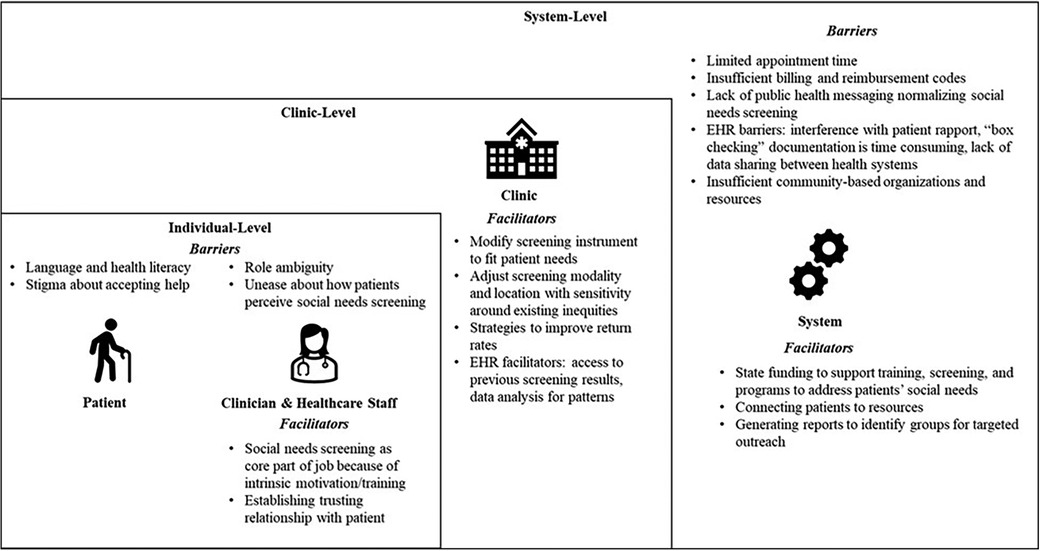

Participants suggested multi-level barriers and facilitators to awareness of and assistance for social needs: (1) individual level, including clinician perceptions of patient, provider, and healthcare staff factors; (2) clinic level; and (3) system level (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Overview of individual-, clinic-, and system-level barriers and facilitators in eliciting social needs screening in Maryland primary care practices.

Individual-level factors

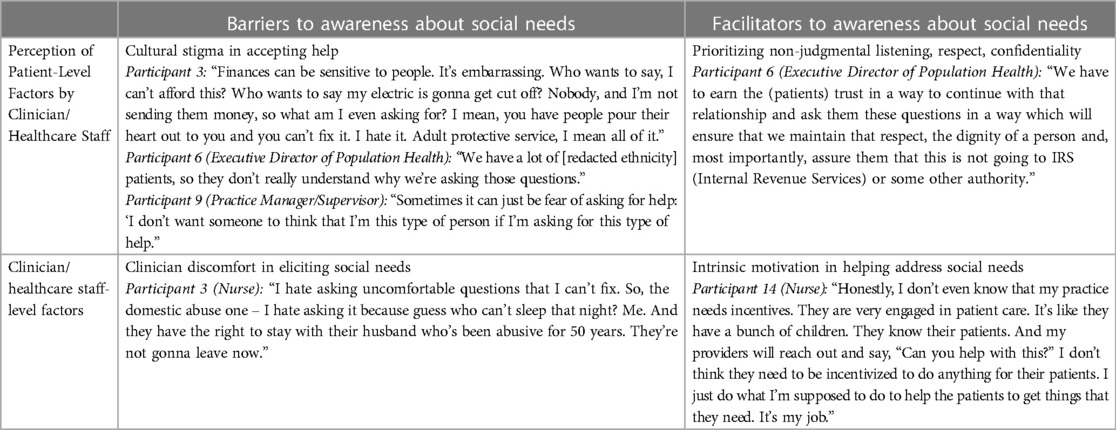

With regard to awareness of social needs, perceived cultural barriers were described by some providers, who noted that some patients’ cultural stigma in accepting help interfered with discussing needs in the first place. The participants were also worried about patients’ perception of social needs screening in a medical setting in terms of how data might be used and shared. Other provider barriers included discomfort in asking about social needs that they were unable to address (e.g., loneliness, patients who are victims of domestic violence and who are unwilling or unable to leave an abusive home environment). Finally, some providers were reluctant to elicit social needs because of a lack of knowledge of community-based resources to address these needs.

However, providers reported several facilitators to these individual-level factors, including addressing patient hesitancy to share social needs data through respectful and non-judgmental listening, prioritizing patient dignity, and assuring data confidentiality. In addition, intrinsic motivation led some clinicians to view asking about patients’ social needs as a core part of their job. Clinician and healthcare staff-level barriers to assisting patients with social needs include the lack of knowledge about community-based organizations (CBOs). Table 2 details the illustrative quotes on these individual-level barriers and facilitators to awareness about social needs.

Table 2 Illustrative quotes on individual-level barriers and facilitators that influence awareness of social needs screening in primary care.

Clinic-level factors

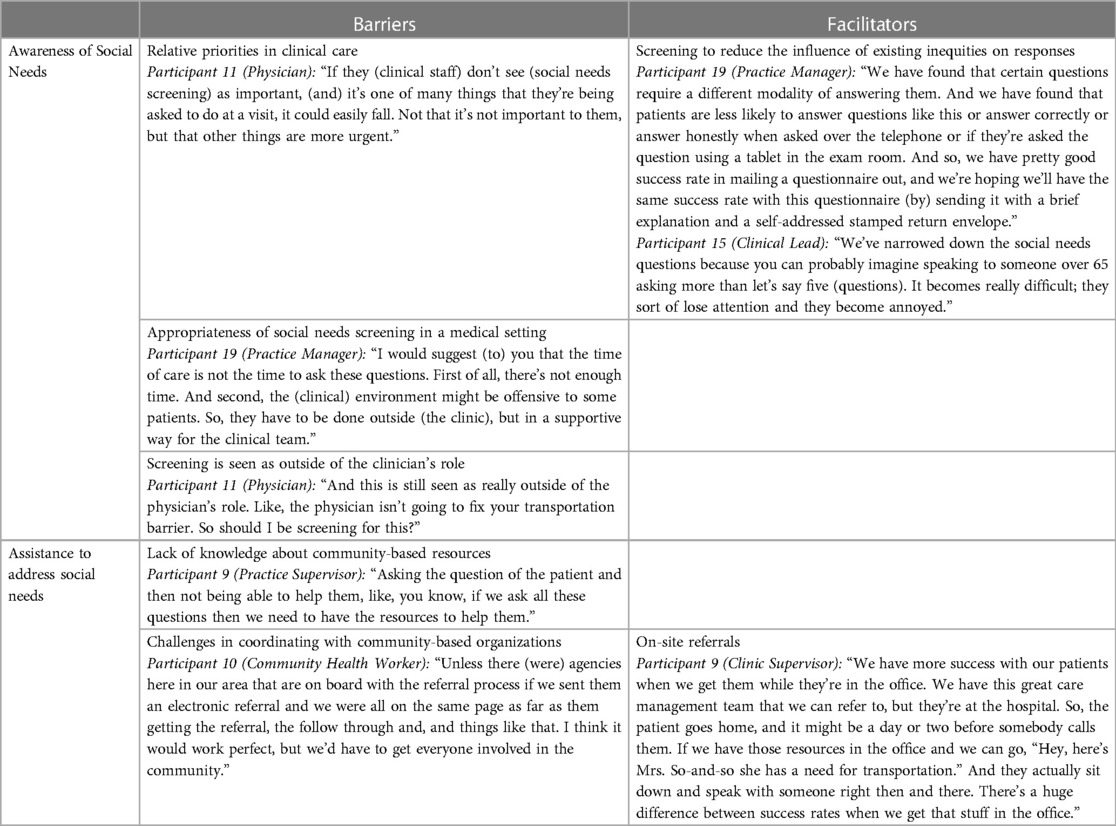

At the clinic level, participants suggested several barriers to conducting screening including relative priorities, insufficient time to address social needs, lack of community resources or knowledge of resources, and billing structures not supporting the time spent on screening.

Participants also mentioned several clinic-level facilitators. Many of them recognized the influence of screening modality (e.g., paper, tablet), location (i.e., in the patient's home or clinic), and existing inequities (e.g., lack of access to a phone) on responses. Some therefore chose unobtrusive screening procedures to improve return rate (e.g., enclosing questionnaire in a self-addressed stamped envelope) and modified screening instruments to better fit patient needs.

A clinic-level barrier to providing assistance for social needs included difficulties in coordinating with CBOs; a facilitator was using on-site referrals and leveraging connections within (e.g., word of mouth) and outside the practice (e.g., using publicly available databases such as findhelp.org) to assist patients’ unmet social needs. Table 3 details the illustrative quotes on these clinic-level barriers and facilitators to awareness about social needs.

Table 3 Illustrative quotes on clinic-level barriers and facilitators that influence awareness of and providing assistance for social needs screening in primary care.

System-level factors

Participants expressed several barriers related to the larger healthcare system that adversely impacted social needs screening in primary care settings. One clinician suggested that the lack of public health messaging about the impact of social needs on health contributed to the stigma of eliciting or expressing social needs in medical settings and that public health campaigns were needed to normalize the discussion of social needs as part of medical care to reduce stigma.

Several interviewees emphasized EHR-related barriers. First, EHR documentation during the clinical encounter or transferring results from paper screeners into the EHR was time-consuming. Second, EHR documentation interfered with establishing rapport, detracted from interactions with the patient, and was perceived to be unnecessary “box checking.” Third, the lack of data sharing between health systems and CBOs interfered with obtaining a complete picture of patient needs, whether social or medical. Fourth, even within a single healthcare system where providers used the same EHR, it was difficult to integrate disparate pieces of data that were scattered across the EHR to determine how to track screening for the patients’ social needs.

However, the participants also mentioned EHR facilitators. First, some EHRs enabled providers to access screening completed by other specialists, thereby reducing patient frustration with repeated screening. Second, it allowed practices to analyze data patterns to enable targeted screening and offer services to patients who met target criteria (e.g., patients aged over 65 years in a specific zip code). An additional facilitator that increased awareness of social needs was the HEART reimbursement program that funded social needs screening processes and provider training.

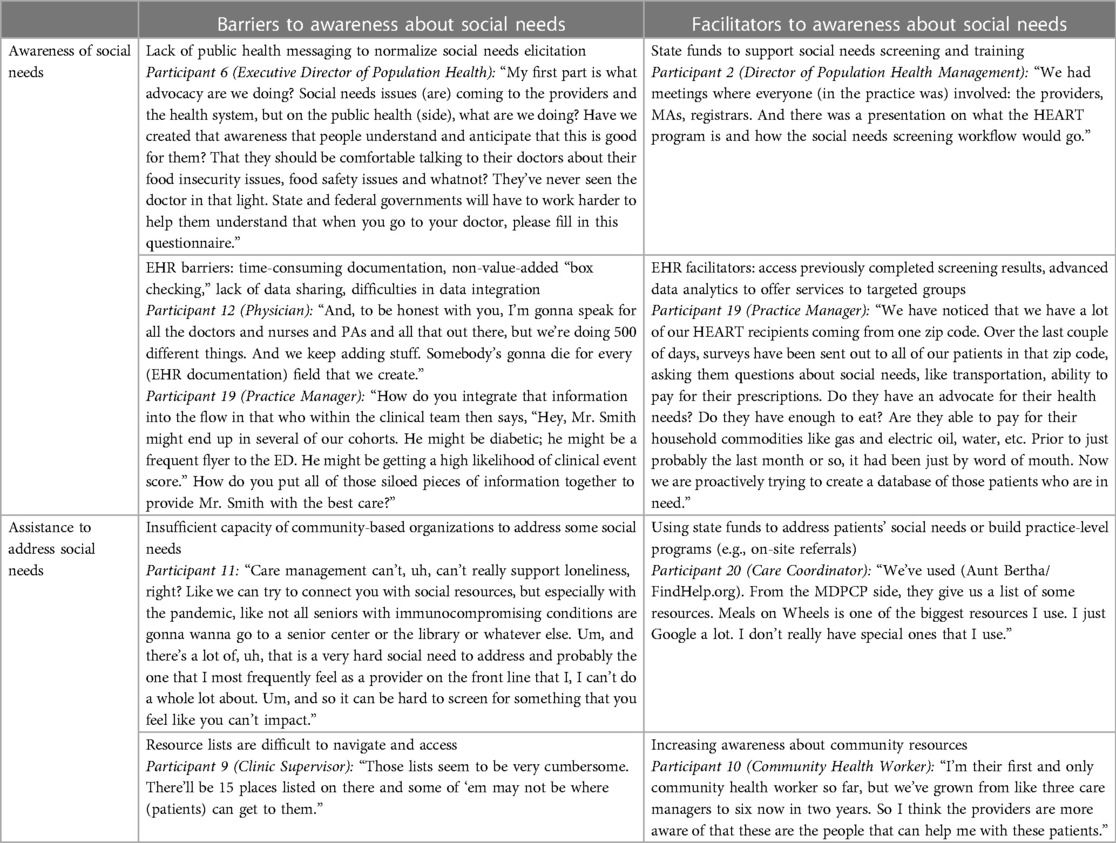

Participants also mentioned system-level barriers to providing assistance for social needs. These included insufficient capacity to address some social needs such as loneliness and resource lists that were difficult to navigate and access; a facilitator was using HEART funds to address patients’ needs or build practice-level programs. Table 4 details the illustrative quotes on these system-level barriers and facilitators to awareness about social needs.

Table 4 Illustrative quotes on system-level barriers and facilitators that influence awareness of and providing assistance for social needs screening in primary care.

Discussion

Research exploring provider perceptions and acceptance of social needs screening highlights the complex operational issues that must be considered before large-scale implementation of social needs screening. NASEM recommends five strategies to improve the integration of patients’ social needs into healthcare delivery: awareness, adjustment, assistance, alignment, and advocacy (1). There is no gold standard screening tool recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force or professional societies for primary or specialty care, introducing significant variation in whether screening is standardized and part of routine care. Our study highlights not only how barriers and facilitators to social needs screening at the individual, clinic, and system levels affect awareness about patients’ social needs but also how difficulties in addressing the strategy of providing assistance for social needs preclude this awareness.

Our findings of provider-level barriers such as perceptions of the limited utility of asking patients about social needs in a medical setting have been previously reported (16, 17, 26, 27). At the same time, we also found a limited understanding of how care activities can be adjusted to accommodate patients’ social needs. This suggests that rather than consider a linear implementation of the five NASEM strategies to improve the integration of social needs in care delivery, it may be worthwhile considering how strategies that are likely to have a tangible and direct impact on patients, such as providing assistance to patients for their social needs, may strongly impact the likelihood of engaging in awareness activities. In addition, from the perspective of healthcare providers who directly interface with patients, the ability to provide assistance may be seen as more important for direct patient care compared to strategies that boost social needs integration at larger levels of the system, i.e., alignment and advocacy. In addition, while we frame results through the socio-ecological model, these different levels are inherently connected and should be considered together in any workflow modifications or implementation recommendations. For example, some individual-level barriers by providers in conducting screening were attributable to higher-level barriers, including limited time during a typical appointment to sufficiently address patients’ social needs, balancing patient interaction with onerous EHR documentation requirements, and a relative paucity of community-based resources to address social needs.

Previous research has also found that stigma may prevent patients from sharing social needs with providers (13, 28). Our study extends these findings to suggest other multi-level strategies to combat stigma about expressing social needs in clinical settings. These include respectful and non-judgmental listening by clinicians and healthcare staff eliciting social needs, assuring patients about data confidentiality, and at a broader system level, public health messaging around social needs screening to potentially normalize such discussions in medical settings.

Research demonstrates that providers perceive many benefits of social needs screening, including tailoring care to patients’ social needs, informing community action, and building a robust referral network (16, 26, 29). Our findings were similar in that most healthcare clinicians acknowledged the importance of assessing social needs. However, clinicians also recognized several barriers that did not support this process in primary care. System-level barriers such as limited appointment times and competing priorities, insufficiently trained staff to administer the screening and coordinate referrals, and insufficient knowledge about resources to address social needs have also been raised in previous research (27, 29–31). A previous study summarizing professional medical association policy statements on social needs screening underscored this problem, highlighting how pediatrics, family medicine, and obstetrics and gynecology are leaders in encouraging screening, but do not have detailed recommendations around how and when screening should occur (32).

Our study also found that engaging in conversations about patients’ social needs and addressing needs calls for special competencies that require time and effort. Providers must navigate uncomfortable situations to elicit social needs. They must also be knowledgeable about community-based resources that exist to address social needs and know how to modify the patient's plan of care to ensure treatment access within the context of unmet needs. These tasks are important but can add to the provider’s workload if there is an expectation of also completing other clinical responsibilities within the same appointment in which social needs are assessed or addressed. Healthcare policies guiding workforce development must be reimagined to accommodate social needs and screening-related tasks to minimize provider burnout from having to perform these tasks (33).

Of note, although participants reported using HEART payment funds to support training for social needs screening, they perceived limited support in being able to effectively use these funds to assist patients’ social needs. Many providers mentioned the lack of awareness of resources within the community or how to make referrals to these resources. Therefore, they were hesitant about surfacing social needs that they were unable to address. This highlights that along with investing in improving understanding of patients’ social needs in clinical settings, there is a need to simultaneously increase investment in CBOs that can meet patients’ social needs.

In consideration of the NASEM framework, it is important that providers not only become aware of patients’ social needs and adjust the care plan accordingly but also support awareness and adjustment by ensuring that there is alignment of community resources to address unmet needs through advocacy. Thus, social needs screening implementation in primary care must consider how awareness of social needs is influenced by activities that occur at later stages in the NASEM framework, i.e., the ability to provide assistance by aligning the availability of community-based resources to address the identified needs. Our research demonstrates that providing assistance for unmet needs may be difficult unless there is system-level consideration of putting resources in place to directly address social needs (e.g., programs like HEART), designing tools to make these resources easy to locate, and designing workflows that improve the ease of coordinating referrals to CBOs. These findings are largely supported by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accountable Health Communities Act study which found that it was challenging to resolve individual patient's social needs, even with navigators (34).

Our study had several limitations. We relied on individuals who volunteered to participate within the primary care network, which may not capture an exhaustive list of barriers and facilitators to social needs screening in primary care practices across Maryland. Additionally, we were not able to interview patients or those experiencing the screening as part of this project. However, we did have access to all potentially eligible practices and purposively sampled to get representation across various patient characteristics. Furthermore, these findings may not be generalizable to primary care practices across Maryland that are not part of this network, practices within the network that are not interested in research, or those in other states with different incentives or supports.

Conclusions

Overcoming barriers to social needs screening in primary care requires simultaneous changes at multiple levels of the socio-ecological system in which these activities occur because engaging in activities to become aware of social needs is informed by providers’ abilities to assist with these needs by leveraging community-based resources. Thus, although it is important to implement practice- and provider-level process changes to improve screening, these individual-level changes must also be accompanied by changes at the larger system level by aligning community resources and implementing policies to redistribute community assets to address social needs.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Helsinki Declaration, Georgetown-MedStar IRB Ethics Committee (Protocol 4986). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the participants provided verbal informed consent to participate in the interviews (Ethics Approval Committee: Georgetown-MedStar IRB, Protocol 4986).

Author contributions

SK: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CS: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AM: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. BB: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RG: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. EG: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. KM: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. HA: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control National Initiative to Address COVID-19 Health Disparities Among Populations at High-Risk and Underserved, Including Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations and Rural Communities grant number OT21-2103 through the Maryland Department of Health.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frhs.2024.1380589/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CBOs, community-based organizations; EHR, electronic health record; HEART, Health Equity Advancement Resource and Transformation; MDPCP, Maryland Primary Care Program; NASEM, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

References

1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation's Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2019). doi: 10.17226/25467

2. Bibbins-Domingo K. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care. JAMA. (2019) 322(18):1763. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.15603

3. Walker RJ, Smalls BL, Campbell JA, Strom Williams JL, Egede LE. Impact of social determinants of health on outcomes for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Endocrine. (2014) 47(1):29–48. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0195-0

4. Cockerham WC, Hamby BW, Oates GR. The social determinants of chronic disease. Am J Prev Med. (2017) 52(1):S5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.010

5. Wan W, Li V, Chin MH, Faldmo DN, Hoeffling E, Proser M, et al. Development of PRAPARE social determinants of health clusters and correlation with diabetes and hypertension outcomes. J Am Board Fam Med. (2022) 35(4):668–79. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2022.04.200462

6. Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. In: Vasta R, editor. Annals of Child Development: Volume 6. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers (1989). p. 187–249.

7. Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. (1977) 32(7):513–31. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

9. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. (2005) 83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

10. Rosano A, Loha CA, Falvo R, van der Zee J, Ricciardi W, Guasticchi G, et al. The relationship between avoidable hospitalization and accessibility to primary care: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. (2013) 23(3):356–60. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks053

11. Babor TF, Sciamanna CN, Pronk NP. Assessing multiple risk behaviors in primary care: screening issues and related concepts. Am J Prev Med. (2004) 27(SUPPL.):42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.018

12. Rogers AJ, Hamity C, Sharp AL, Jackson AH, Schickedanz AB. Patients’ attitudes and perceptions regarding social needs screening and navigation: multi-site survey in a large integrated health system. J Gen Intern Med. (2020) 35(5):1389–95. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05588-1

13. Broaddus-Shea ET, Fife Duarte K, Jantz K, Reno J, Connelly L, Nederveld A. Implementing health-related social needs screening in western Colorado primary care practices: qualitative research to inform improved communication with patients. Health Soc Care Community. (2022) 30(5):e3075–85. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13752

14. Trochez RJ, Sharma S, Stolldorf DP, Mixon AS, Novak LL, Rajmane A, et al. Screening health-related social needs in hospitals: a systematic review of health care professional and patient perspectives. Popul Health Manag. (2023) 26(3):157–67. doi: 10.1089/pop.2022.0279

15. Hamity C, Jackson A, Peralta L, Bellows J. Perceptions and experience of patients, staff, and clinicians with social needs assessment. Perm J. (2018) 22:1–5. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-105

16. Nehme E, de Martell SC, Matthews H, Lakey D. Experiences and perspectives on adopting new practices for social needs-targeted care in safety-net settings: a qualitative case series study. J Prim Care Community Health. (2021) 12:21501327211017784. doi: 10.1177/21501327211017784

17. Tong ST, Liaw WR, Kashiri PL, Pecsok J, Rozman J, Bazemore AW, et al. Clinician experiences with screening for social needs in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. (2018) 31(3):351–63. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.03.170419

18. Gruß I, Bunce A, Davis J, Dambrun K, Cottrell E, Gold R. Initiating and implementing social determinants of health data collection in community health centers. Popul Health Manag. (2021) 24(1):52–8. doi: 10.1089/pop.2019.0205

19. Beil H, Brower HM, Chepaitis A, Clayton M, DePriest K, Derzon J, et al. Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model Evaluation: Second Evaluation Report. (2023). Available online at: https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/data-and-reports/2023/ahc-second-eval-rpt (Accessed May 6, 2024).

20. Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research. Technical Brief Screening and Interventions for Social Risk Factors: A Technical Brief to Support the U.S. Preventive Services Task. (2021). Available online at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/inline-files/SocialRiskFactorsTechBrief_AssembledforWeb_Sep2021_1.pdf (Accessed May 6, 2024).

21. American Academy of Pediatrics. No Title. Bright futures. Available online at: https://www.aap.org/en/practice-management/bright-futures/ (Accessed May 6, 2024)

22. Maryland State Department of Health. Maryland Primary Care Program. Available online at: https://health.maryland.gov/mdpcp/Pages/home.aspx (Accessed March 15, 2023)

23. Program MPC. HEART Payment Playbook. (2022). Available online at: https://health.maryland.gov/mdpcp/Documents/MDPCP_HEART_Payment_Playbook.pdf (Accessed May 6, 2024).

24. Dedoose: Cloud Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data. Available online at: www.dedoose.com (Accessed May 6, 2024).

25. Noble H, Mitchell G. What is grounded theory? Evid Based Nurs. (2016) 19(2):34–5. doi: 10.1136/eb-2016-102306

26. Chhabra M, Sorrentino AE, Cusack M, Dichter ME, Montgomery AE, True G. Screening for housing instability: providers’ reflections on addressing a social determinant of health. J Gen Intern Med. (2019) 34(7):1213–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04895-x

27. Byhoff E, De Marchis EH, Hessler D, Fichtenberg C, Adler N, Cohen AJ, et al. Part II: a qualitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am J Prev Med. (2019) 57(6):S38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.016

28. Drake C, Batchelder H, Lian T, Cannady M, Weinberger M, Eisenson H, et al. Implementation of social needs screening in primary care: a qualitative study using the health equity implementation framework. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06991-3

29. Berry C, Paul M, Massar R, Marcello RK, Krauskopf M. Social needs screening and referral program at a large US public hospital system. Am J Public Health. (2020) 110(S2):S211–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305642

30. Sandhu S, Xu J, Eisenson H, Prvu Bettger J. Workforce models to screen for and address patients’ unmet social needs in the clinic setting: a scoping review. J Prim Care Community Health. (2021) 12:21501327211021021. doi: 10.1177/21501327211021021

31. Eismann EA, Theuerling J, Maguire S, Hente EA, Shapiro RA. Integration of the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) model across primary care settings. Clin Pediatr (Phila). (2019) 58(2):166–76. doi: 10.1177/0009922818809481

32. Gusoff G, Fichtenberg C, Gottlieb LM. Professional medical association policy statements on social health assessments and interventions. Perm J. (2018) 22(4S). doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-092

33. Telzak A, Chambers EC, Gutnick D, Flattau A, Chaya J, McAuliff K, et al. Health care worker burnout and perceived capacity to address social needs. Popul Health Manag. (2022) 25(3):352–61. doi: 10.1089/pop.2021.0175

34. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Findings at a Glance: Accountable Health Communities Model 2018–2021. Available online at: https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/ahcm

Keywords: social needs screening, primary care, patient stigma, documentation, community resources, qualitative methods

Citation: Kazi S, Starling C, Milicia A, Buckley B, Grisham R, Gruber E, Miller K and Arem H (2024) Barriers and facilitators to screen for and address social needs in primary care practices in Maryland: a qualitative study. Front. Health Serv. 4:1380589. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2024.1380589

Received: 1 February 2024; Accepted: 21 May 2024;

Published: 17 June 2024.

Edited by:

Sylvester Reuben Okeke, University of New South Wales, AustraliaReviewed by:

Mina Motamedi, ECA College of Health Sciences, AustraliaJosielli Comachio, The University of Sydney, Australia

© 2024 Kazi, Starling, Milicia, Buckley, Grisham, Gruber, Miller and Arem. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sadaf Kazi, c2FkYWYua2F6aUBtZWRzdGFyLm5ldA==

Sadaf Kazi

Sadaf Kazi Claire Starling

Claire Starling Arianna Milicia1

Arianna Milicia1 Bryan Buckley

Bryan Buckley Hannah Arem

Hannah Arem