- 1School of Public Health, St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 2College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 3Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway

Background: Postoperative complications remain a significant challenge, especially in settings where healthcare access and infrastructure disparities exacerbate. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the pooled incidence and risk factors of postoperative complications among patients undergoing essential surgery in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

Method: PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched from January 2010 to November 2022 for completed studies reporting the incidence and risk factors associated with postoperative complications among patients undergoing essential surgery in SSA. Severity of postoperative complications was ranked based on the Clavien-Dindo classification system, while risk factors were classified into three groups based on the Donabedian structure-process-outcome quality evaluation framework. Studies quality was appraised using the JBI Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI), and data were analyzed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software. The study protocol adhered to the PRISMA guidelines and was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023414342).

Results: The meta-analysis included 19 studies (10 cohort and 9 cross-sectional) comprising a total of 24,136 patients. The pooled incidence of postoperative complications in SSA was 20.2% (95% CI: 18.7%–21.8%), with a substantial heterogeneity of incidence observed. The incidence varied from 14.6% to 27.5% based on the Clavien-Dindo classification. The random-effects model indicated significant heterogeneity among the studies (Q = 54.202, I = 66.791%, p < 0.001). Contributing factors to postoperative complications were: structure-related factors, which included the availability and accessibility of resources, as well as the quality of both the surgical facility and the hospital.; process-related factors, which encompassed surgical skills, adherence to protocols, evidence-based practices, and the quality of postoperative care; and patient outcome-related factors such as age, comorbidities, alcohol use, and overall patient health status.

Conclusion: The meta-analysis reveals a high frequency of postoperative complications in SSA, with noticeable discrepancies among the studies. The analysis highlights a range of factors, encompassing structural, procedural, and patient outcome-related aspects, that contribute to these complications. The findings underscore the necessity for targeted interventions aimed at reducing complications and improving the overall quality of surgical care in the region.

Systematic Reviews Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, identifier (CRD42023414342).

Introduction

Surgery is an essential aspect of healthcare globally, playing a significant role in preventing, diagnosing and treating various medical conditions (1). Emergency and essential surgical care, according to the World Health Organization, refers to the provision of surgical services that are crucial for addressing life-threatening conditions, preventing disability, and improving overall health outcomes in a community or population (2). However, postoperative complications remain a significant challenge, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where healthcare access and infrastructure disparities exacerbate (3).

Quality of surgical care is crucial for optimal patient outcomes. Quality of care refers to healthcare services that meet patient needs and expectations while achieving desired health outcomes (4). The Donabedian quality model examines healthcare quality using three elements: structure, process, and outcome (5). To provide appropriate care, it is necessary to have sufficient access to staff, equipment, and facilities. Research has shown that a shortage of these resources is linked to a higher incidence of postoperative complications (6, 7). A high-quality process involves promptly recognizing and managing complications, and utilizing the best techniques to minimize them (8). A high-quality outcome in the context of healthcare, particularly in surgery, refers to achieving the best possible results for the patient following a procedure or treatment (9). By evaluating these elements, the Donabedian model assesses the quality of care for post-operative complications, reflecting the overall quality of care offered.

Post-operative complications refer to adverse events or outcomes that occur as a result of a surgical procedure. Surgical complications can encompass a wide range of issues, including infections, bleeding, organ damage, adverse reactions to anesthesia, wound complications (such as dehiscence or hernias), blood clots, and surgical errors (10).

Surgical patients in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) confront formidable hurdles stemming from deficient healthcare facilities, scarce resources, inadequate infrastructure, and insufficient professional training, all of which elevate the risk of postoperative complications and exacerbate the burden of surgical diseases in the region (11). However, comprehensively understanding these challenges is impeded by the lack of standardization in data collection and reporting, as well as by variations in study populations and settings. This inconsistency hinders accurate assessment of complication prevalence and severity, complicating efforts to address these issues effectively (12).

Therefore, a comprehensive synthesis of the available literature is necessary to identify common patterns and risk factors for postoperative complications in SSA. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of the aggregated incidence and risk factors of postoperative complications among surgical patients in SSA.

Methods

Study design

The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis has been registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database, ID: CRD42023414342, and adhered to the PRISMA guidelines for the design and reporting of the results.

Search strategy

PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched from January 2010 to November 2022 for completed studies that reported the incidence and risk factors of postoperative complications among patients undergoing Emergency & essential surgery in SSA. The year 2010 marked a pivotal period where significant attention was drawn to the burden of surgical disease in sub-Saharan Africa, as highlighted in existing literature (13). Additional studies were searched manually from reference lists of some important articles. Controlled medical subject headings (MeSHs) terms and keywords words were used in different combinations using Boolean Operators. The keywords included surgery, postoperative, incidence, risk, and sub-Saharan Africa.

Eligibility criteria

PICOS (participants, interventions, comparison, outcomes, and study designs) design was used to establish the eligibility criteria.

- Participants: Patients of any age in SSA undergoing essential surgery.

- Intervention: Emergency and Essential surgery, which was referred to, based on the WHO guidelines (11), as a set of surgical procedures that are considered crucial for addressing substantial health needs.

- Comparison: Articles with or without a comparator were eligible.

- Outcomes: Primary outcome: incidence of postoperative complications, with the severity of the surgical complications ranked based on the Clavien Dindo classification system (14). Secondary outcome: risk factors for postoperative complications which are categorized into three groups based on the Donabedian structure-process-outcome framework for evaluation of quality of healthcare and services.

- Study design: No restrictions on study designs.

The classification of outcomes was conducted by the authors of the manuscript during the study's methodology and data analysis phases.

Studies were excluded if done outside SSA, carried out in animal models, not reported in the English language, or were non-empirical publications such as reviews, editorials, commentaries, or conference abstracts.

Study selection

Two independent authors screened the titles and abstracts of identified studies based on selection criteria and using a standardized form that guided their evaluation process. Studies that were duplicates or did not meet the inclusion criteria in the initial title and abstract searches were excluded and full texts of the remaining studies were further evaluated. Any disagreements between the authors were resolved through discussions. Mendeley Desktop Version 1.19.8 software was used to control potential duplicates.

Data extraction

The Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis Of Statistics Assessment And Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI) was used to extract descriptive data from the included articles. The data extracted include surname of the first author, year of publication, country, study population, sample size, data collection method(s), outcome measures, data analysis, and any study limitations reported by the author.

Assessment of risk of bias

Studies that matched the inclusion criteria were appraised using the JBI System for the Unified Management, Assessment, and Review of Information (JBI-SUMARI) tool (15). The JBI-MAStARI was used to evaluate studies with quantitative evidence. The evaluation was conducted by two independent reviewers. The appraisal tool had nine risk of bias questions that the reviewers used to score each article as low (0–3), moderate (4–6), or high quality (15).

Heterogeneity was evaluated using standard statistical tests (chi-square and I2) and subgroup analysis if statistical pooling was not feasible.

Statistical analysis

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software was used to do the meta-analysis. Effect sizes were expressed as event rates for categorical data with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The study's outcomes of interest were measured as categorical or continuous variables, and odds ratios or regression coefficients were collected, along with data on potential confounding factors.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 1,927 potentially relevant records were identified in the initial search of the databases, of which 1,868 remained after removing 59 duplicates. After title and abstract screening, 1,764 studies were excluded and the remaining 104 articles were analyzed in full-text, of which 19 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

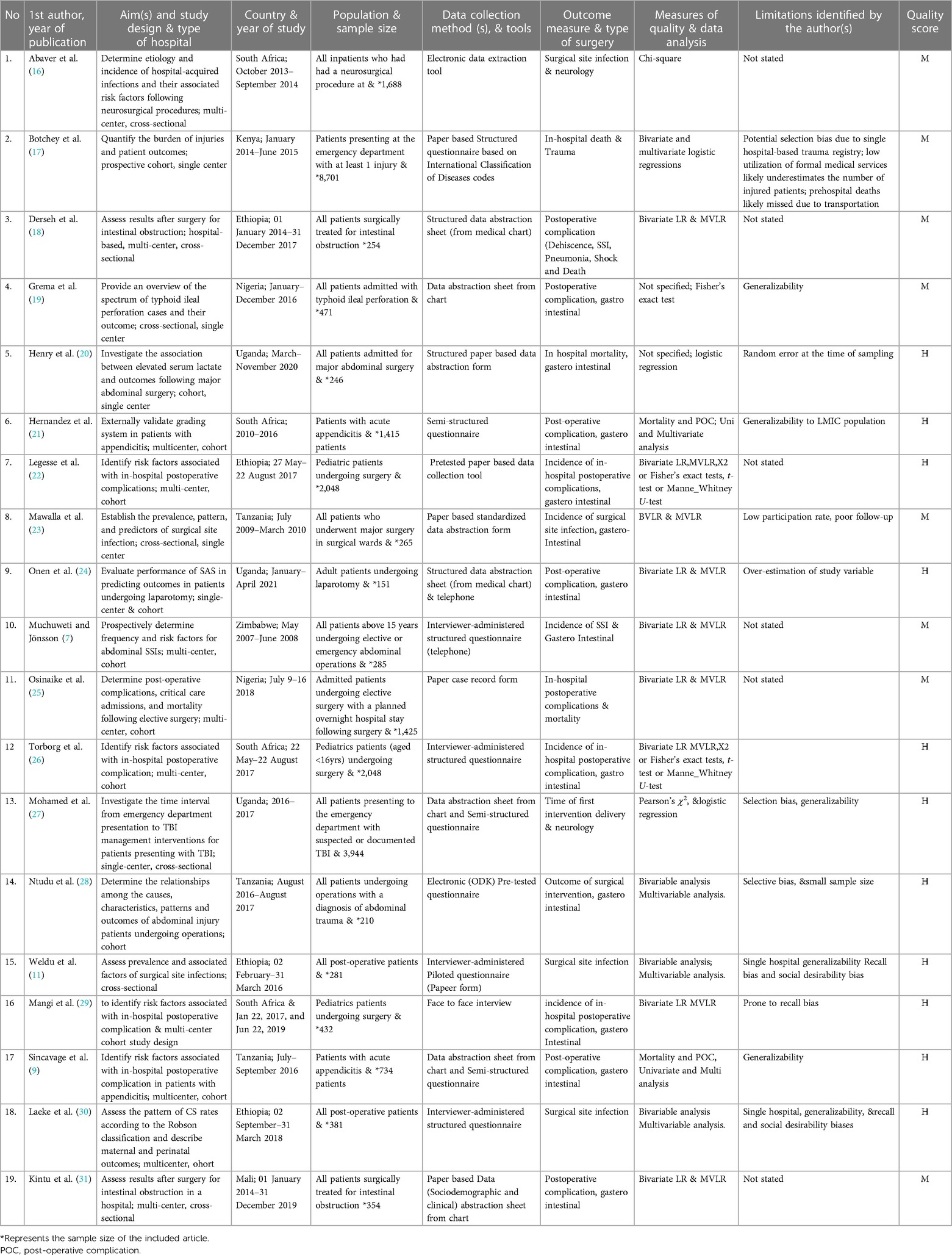

The table summarizes the characteristics of the 19 articles included in a meta-analysis conducted across various countries in sub-Saharan Africa between 2007 and 2021. Out of the 19 included articles, nine were cross-sectional studies, with three of the nine rated as high quality. Nine of the studies used systematic random sampling to select participants, while the remaining articles followed a cohort study design, with five out of ten rated as high quality. The samples taken were representative, and outcomes were measured using structured questionnaires. The outcomes focused on postoperative complications, mortality, and surgical site infections across neurosurgery, trauma surgery, and abdominal surgery. All studies controlled for confounding factors and employed various statistical tests for data analysis. Limitations identified included potential selection bias, poor follow-up, and generalizability concerns, highlighting the challenges and considerations in the studies (Table 1).

The records of studies excluded in the full-text reviews with underlying reasons are summarized in Supplementary File S1. Findings from methodological quality assessment of the cross-sectional and cohort studies included in the meta-analysis are summarized in Table 2.

Incidence of postoperative complications

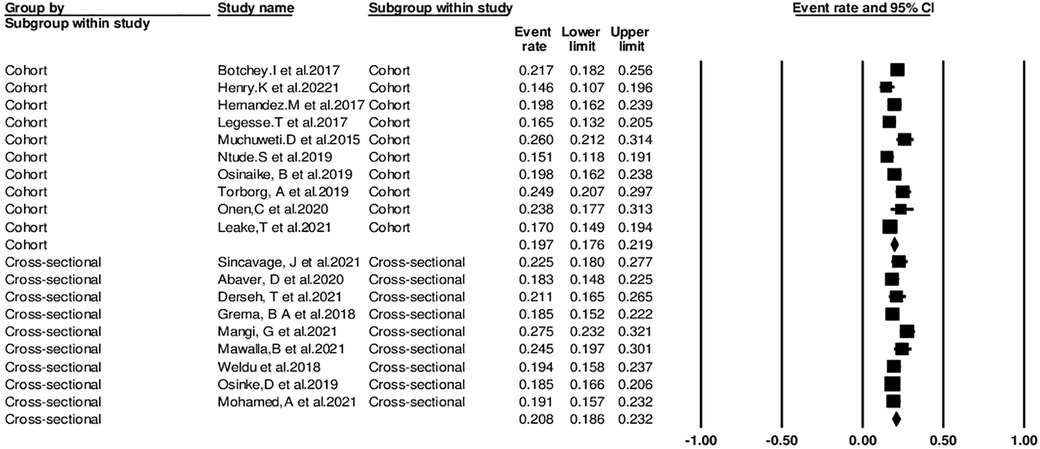

In the meta-analysis of the nineteen studies, a total of 24,136 patients were included, with 2,372 experiencing postoperative complications after undergoing essential surgery. The overall incidence of postoperative complications was calculated to be 20.2% (95% CI: 18.7%–21.8%) using the random-effects model, showing significant heterogeneity among the studies. The incidence ranged from 14.6% to 27.5% based on the Clavein-Dindo classification system (Figure 2).

Donabedian quality measures

Nineteen studies utilized the Donabedian quality model to evaluate healthcare quality using the three dimensions of structure, process, and outcome across diverse settings. Among 19 studies, fourteen (73.6%) evaluated the structure and process, 12 (80%) evaluated Process relate factor seventeen (89.5%) and nineteen (100%) articles were Outcome related factors evaluated the process. The studies focus on a range of topics, including surgical site infections, postoperative complications, mortality, risk factors for poor outcomes, and predictors of in-hospital death.

The identified factors have been categorized into three groups—structure, process, and outcomes—based on the Donabedian framework for the evaluation of the quality of healthcare and services. Overview of the statistically significant factors identified in the studies (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of the statistically significant risk factors of postoperative complications in Sub-saharan Africa.

Structure-related factors

Among the nineteen studies, seventeen clearly have pinpointed structural factors that influence surgical procedures. The identified factors encompass various aspects of both prehospital and hospital care (25). These include the mechanism of injury, Patient admission path(direct from emergency department to Operating room or Surgical ward/unit), and the process of diagnosis and initial management (17). Factors like the duration of illness, preoperative diagnoses, and the need for ICU admission were also highlighted (19) Moreover, the availability of emergency case operating rooms, pre-surgical antibiotics, and essential surgical equipment were crucial considerations (20, 29). Issues such as reduced access to advanced imaging techniques, interrupted referral linkages between health facilities, and turnover of trained manpower contribute to deficits in care. Additionally, factors like staffing of trained manpower, mode of transport to the hospital, and the length of post-operative hospital stays further impact patient outcomes. Detection time of surgical site infections, types of bacteria involved, and the duration of operations also play significant roles in determining outcomes (22, 32).

Process-related factors

Among the nineteen studies, seventeen clearly delineate process-related factors influencing surgical outcomes. Prolonged hospital stays exceeding 30 days and the implementation of specific procedures such as drains and iodine skin preparation emerge as prevalent risk factors for postoperative complications (16, 33). Factors like preoperative diagnosis of gangrenous small bowel, emergency laparotomy, and extended time between diagnosis and surgical intervention were identified as contributors to adverse outcomes (21). Additionally, the administration of antimicrobial prophylaxis within one hour of operation was recognized as a significant risk factor, Urgency and severity of surgery, operation duration surpassing 1.5 h, the use of local anesthesia, and dirty incision classification further underscore the complexity of adverse process-related outcomes (34).

Patient outcome-related factors

All included studies have highlighted different risk factors influencing surgical outcomes and leading to postoperative complications (16, 18). Notably, patient age has emerged as a common factor, with individuals aged 35 years or older, at higher risk of complications (23) Additionally, pre-existing illnesses and comorbidities significantly contribute to adverse effects (23, 28). Factors such as smoking and a history of alcohol use was linked to increased postoperative complication risks (30). Other significant contributors include the presence of peritonitis upon admission, pre-anesthesia medical comorbidities classified by the ASA Physical Status Classification System, and severe injury defined by the New Injury Severity Score (26), Moreover, the use of drains during surgery and iodine alone in skin preparation was associated with elevated complication risks following abdominal surgery (16, 33).

Heterogeneity

The random-effects model indicated significant heterogeneity among the studies (Q-value = 54.202, p < 0.001, I-squared = 66.791%), demonstrating that the variation in effect sizes was not purely random. The Tau-squared value of 0.029 indicated a substantial degree of heterogeneity among the studies.

Subgroup analysis

The pooled incidence of postoperative complications based on the Clavein-Dindo classification system in the seven cross-sectional studies was 20.8% (95% CI: 18.6%–23.2%), while the pooled incidence in the remaining cohort studies was 19.7% (95% CI: 17.6%–21.9%). The difference in incidence between the two study designs was statistically significant (p = 0.001). Therefore, the type of study design appears to be a significant source of heterogeneity (Figure 3).

Sensitivity analysis

The results showed that no individual study significantly affected the overall incidence estimate of post-operative complications by more than 1%, indicating that our results were robust and not driven by a single study.

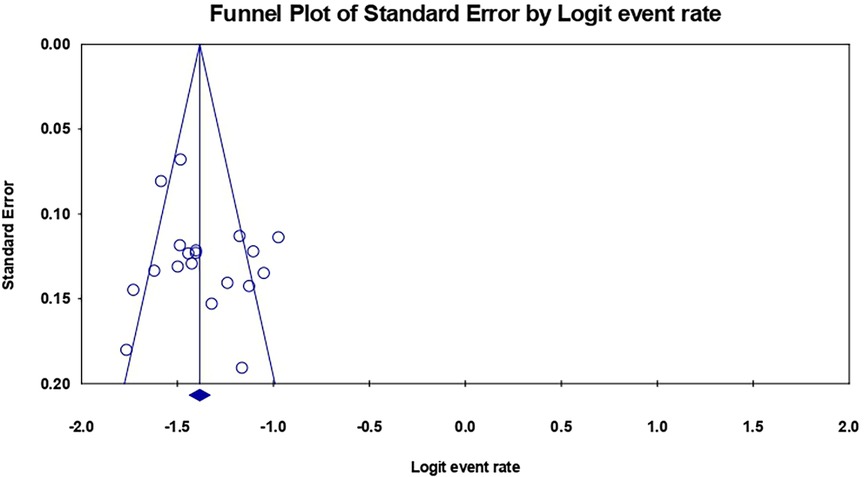

Publication bias

The funnel plot revealed asymmetry pinpointed to the left (Figure 4), suggesting a potential publication bias in the included studies. To further investigate this, Egger's test was conducted, yielding a significant result (p < 0.339), providing additional evidence for the absence of publication bias.

Figure 4. Funnel plot of the included studies in this meta-analysis for the incidence of postoperative complications.

Discussion

Postoperative complications are adverse events that occur after surgery and can significantly impact a patient's recovery and outcome. According to this meta-analysis, these complications may be influenced by patient-related factors such as age, pre-morbid illness, smoking, alcohol use, and severity of injury, as well as process-related factors such as duration of operation, use of drains, skin preparation, antimicrobial prophylaxis, and type of surgery.

Structure-related factors

Structure-related factors within healthcare systems play a pivotal role in shaping surgical outcomes, encompassing various elements such as resource availability, staffing levels, and the quality of surgical facilities. Our analysis underscores the significant impact of these factors on patient care and the overall success of surgical interventions.

The mechanism of injury and pre-hospital care set the stage for subsequent treatment outcomes. Adequate pre-hospital care, including timely assessment and stabilization of patients, is crucial in optimizing outcomes and minimizing the risk of complications upon hospital admission (35, 36). However, deficits in pre-hospital care, such as delays in transport or inadequate emergency medical services, can impede timely access to surgical intervention and exacerbate patient outcomes (37).

The admission path from the emergency department to the operating room or surgical unit is another critical determinant of surgical outcomes. Efficient processes for triage, diagnosis, and initial management are essential in expediting care delivery and facilitating prompt surgical intervention when indicated (38). However, interruptions or delays in this pathway can prolong the time to surgery and increase the risk of adverse outcomes (38).

The availability of resources, including access to intensive care units (ICUs) and emergency case operating rooms is paramount in ensuring timely and appropriate surgical care. Adequate staffing levels and the presence of trained manpower are essential for delivering high-quality surgical services and responding effectively to surgical emergencies (39). Similarly, the availability of essential surgical equipment and supplies is vital in facilitating safe and efficient surgical procedures (9).

Challenges such as interrupted or poor referral linkages between health facilities can hinder access to specialized care and delay surgical intervention, particularly in rural or underserved areas (40, 41). Moreover, high turnover rates of trained manpower and inadequate hospital infrastructure pose significant challenges to maintaining consistent surgical services and may contribute to variations in care quality (42, 43).

Access to advanced imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) scans, is essential for accurate preoperative evaluation and surgical planning (44). However, reduced access to these resources may limit diagnostic capabilities and hinder the timely identification of surgical conditions, potentially leading to delayed or suboptimal treatment.

Postoperative care, including the duration of hospital stays and the detection of surgical site infections (SSIs), also reflects structural factors within healthcare systems (44). Prolonged hospital stays may indicate underlying issues such as inadequate postoperative care or challenges in discharge planning. Similarly, delays in SSI detection may stem from deficiencies in infection control measures or limited access to diagnostic resources (45).

Process-related factors

Process-related factors play a critical role in determining surgical outcomes, encompassing various aspects of the surgical process itself. Factors such as surgical skill, adherence to established protocols, and the use of evidence-based practices are fundamental in ensuring the success of surgical interventions (46, 47). However, our analysis highlights several specific process-related factors that significantly impact postoperative complications.

Prolonged hospital stays exceeding 30 days emerged as a notable risk factor for adverse outcomes. Extended hospitalization not only increases the risk of nosocomial infections but also reflects underlying systemic issues in healthcare delivery, such as delayed discharge planning and inadequate postoperative care (46, 47).

The use of drains and iodine alone in skin preparation during surgery has also been associated with increased postoperative complications. While drains are often employed to prevent fluid accumulation and facilitate wound healing, their indiscriminate use may introduce the risk of infection and other complications (48, 49). Similarly, the use of iodine alone in skin preparation, rather than more comprehensive preoperative skin antisepsis methods, may predispose patients to surgical site infections (50).

Furthermore, the duration of the operation emerged as a significant determinant of postoperative complications. Operations lasting more than three hours pose inherent challenges, including prolonged exposure to anaesthesia and increased surgical stress, which can heighten the risk of adverse outcomes (50).

Preoperative factors, such as the diagnosis of gangrenous small bowel and the necessity for emergency laparotomy, also contribute to adverse surgical outcomes. These conditions often require urgent surgical intervention, leaving little time for thorough preoperative optimization and increasing the complexity of the procedure, thereby elevating the risk of complications (50).

Additionally, delays in making diagnoses and interventions, particularly in emergency settings, exacerbate the risk of adverse outcomes. Prompt recognition and timely intervention are crucial in mitigating the progression of surgical conditions and preventing complications associated with delayed treatment (51).

Anesthesia-related factors, such as the choice of anesthesia and adherence to safety protocols, also influence surgical outcomes. Local anesthesia may offer advantages in certain procedures but must be carefully selected based on patient factors and procedural requirements to minimize complications (52).

The urgency and severity of surgery, as well as the use of prophylactic antibiotics, are further determinants of postoperative complications. Routine surgeries may carry lower inherent risks compared to major or emergency procedures, while the timely administration of prophylactic antibiotics is essential in preventing surgical site infections and reducing the overall risk of complications (53).

Postoperative disposition and length of hospital stay also impact patient outcomes. Efficient postoperative care and discharge planning are crucial in facilitating patient recovery and reducing the risk of complications associated with prolonged hospitalization (54).

Patient outcome-related factors

Patient outcome-related factors play a crucial role in determining the success of surgical interventions, encompassing various individual characteristics such as overall health status, comorbidities, age, and other demographic factors (55). Our analysis highlights the significance of these factors in predicting surgical outcomes and guiding patient management strategies.

Advanced age has consistently emerged as a significant predictor of surgical outcomes, with individuals aged 35 years and above being at higher risk of adverse events. The presence of pre-morbid illnesses, including factors such as cigarette smoking, longer pre-hospital times, and severe injury severity scores, further compounds the risk of postoperative complications (56).

Patients with comorbidities, such as pre-existing medical conditions or a high severity of illness as indicated by the High-SAS category, are particularly vulnerable to adverse surgical outcomes (57). Additionally, late presentation of patients, especially those with symptoms of peritonitis upon admission, poses challenges in timely intervention and may exacerbate postoperative morbidity and mortality rates (58).

Demographic characteristics, including age and sex, interact with the presence of comorbidities to influence surgical outcomes. Notably, older patients with pre-existing comorbidities are at heightened risk, underscoring the importance of comprehensive preoperative evaluation and risk stratification in this population (10).

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification system provides valuable insights into patients' overall health status and perioperative risk, with higher ASA classifications correlating with increased complication rates (10). Similarly, the New Injury Severity Score (NISS) serves as a predictor of postoperative outcomes, reflecting the severity of traumatic injuries and guiding treatment decisions (10).

Other patient-related factors, such as a history of alcohol use, pre-operative anemia, and admission Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, further contribute to the complexity of surgical risk assessment (10). Understanding these factors and their interplay is essential for tailoring treatment plans and optimizing patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis highlights the prevalence of postoperative complications affecting 20.2% of essential surgery procedures in Sub-Saharan countries.

Structural factors significantly influence surgical outcomes and patient care delivery. Addressing challenges related to resource availability, staffing, infrastructure, and care coordination is essential to optimize surgical services and improve patient outcomes. By investing in robust healthcare systems and implementing strategies to overcome barriers, policymakers and healthcare providers can enhance the quality and accessibility of surgical care.

Recognizing and addressing process-related factors are crucial for optimizing surgical outcomes. Prioritizing evidence-based practices, adhering to established protocols, and implementing comprehensive perioperative care strategies can effectively minimize the risk of postoperative complications and enhance patient safety and satisfaction.

Patient outcome-related factors play a pivotal role in shaping surgical outcomes and should be meticulously considered in preoperative assessment and perioperative management. By identifying high-risk patients, implementing evidence-based interventions, and fostering multidisciplinary collaboration, healthcare providers can mitigate the impact of these factors and elevate the overall quality of surgical care.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TM: Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. DD: Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. DK: Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The work was supported by St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Ethiopia. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College or the University of Oslo.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frhs.2024.1353788/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Price R, Makasa E, Hollands M. World health assembly resolution WHA68.15: “strengthening emergency and essential surgical care and anesthesia as a component of universal health coverage”—addressing the public health gaps arising from lack of safe, affordable and accessible surgical and anesthetic services. World J Surg. Springer New York LLC. (2015) 39(9):2115–25. doi: 10.1007/S00268-015-3153-Y/METRICS

2. Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L. Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. (2015) 386(9993):569–624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X

3. Bath M, Bashford T, Fitzgerald JE. What is “global surgery”? defining the multidisciplinary interface between surgery, anaesthesia and public health. BMJ Global Health. BMJ Specialist Journals. (2019) 4(5):e001808. doi: 10.1136/BMJGH-2019-001808

4. Coury J, Scheider Jennifer S, Rivelli J, Amanda F, Evely S. Applying the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) approach to a large pragmatic study involving safety net clinics. BMC Health Serv Res. (2017) 17(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2364-3

5. Donabedian A. Criteria and standards for quality assessment and monitoring. Qual Rev Bull. (1986) 12(3):99–108. doi: 10.1016/S0097-5990(16)30021-5

6. Fleisher LA, Linde-Zwirble WT. Incidence, outcome, and attributable resource use associated with pulmonary and cardiac complications after major small and large bowel procedures. Perioper Med. (2014) 3(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/2047-0525-3-7

7. Muchuweti D, Jönsson KUG. Abdominal surgical site infections: a prospective study of determinant factors in Harare, Zimbabwe. Int Wound J. England. (2015) 12(5):517–22. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12145

8. Starr N, Gawande AA, Thomas EJ, Michael J. The lifebox surgical headlight project: engineering, testing, and field assessment in a resource-constrained setting. Br J Surg. (2020) 107(Annual Meeting of the College-of-Surgeons-of-East-Central-and-Southern-Africa):1751–61. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11756

9. Sincavage J, Msosa VJ, Katete C, Purcell LN. Postoperative complications and risk of mortality after laparotomy in a resource-limited setting. J Surg Res. United States. (2021) 260:428–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.11.017

10. Kurt M, Akdeniz M, Kavukcu E. Assessment of comorbidity and use of prescription and NonprescriptionDrugs in patients above 65 years attending family medicine outpatient clinics. Gerontol Geriatr Med. SAGE Publications. (2019) 5:233372141987427. doi: 10.1177/2333721419874274

11. Weldu MG, Shiferaw WS, Ayalem YA, Akalu TY. Magnitude and determinant factors of surgical site infection in Suhul Hospital Tigrai, northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Surg Infect (Larchmt). Mary Ann Liebert Inc. (2018) 19(7):684–90. doi: 10.1089/sur.2017.312

12. Muula AS, Senkubug F, Modisenyane M, Bishaw T. Prevalence of complications of male circumcision in Anglophone Africa: a systematic review. BMC Urol. (2007) 7:1–4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-7-4

13. Bentounsi Z, Sheik-Ali S, Drury G, Lavy C. Surgical care in district hospitals in Sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. BMJ Open. (2021) 11(3):1–11. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042862

14. Dencker EE, Bonde A, Troelsen A, Varadarajan KM, Sillesen M. Postoperative complications: an observational study of trends in the United States from 2012 to 2018. BMC Surg. BMC. (2021) 21(1):393. doi: 10.1186/S12893-021-01392-Z

15. Yang L, Nasser A, Zhang X, Sawafta FJ, Salah B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of single-port versus conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. No longer published by Elsevier. (2016) 133(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/J.IJGO.2015.08.013

16. Abaver DT, Bokop Fotso C, Muballe D, Vasaikar S, Apalata T. Postoperative infections: aetiology, incidence and risk factors among neurosurgical patients in Mthatha, South Africa. S Afr Med J. (2020) 110(5):403. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i5.13779

17. Botchey IM, Hung Y, Bachani W, Abdulgafoor M, Paruk FM, Amber S, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of injuries in Kenya: a multisite surveillance study. Surgery. (2017) 162(6):S45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.01.030

18. Derseh T, et al. Clinical outcome and predictors of intestinal obstruction surgery in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BioMed Res Int. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Medicine and Health Science, Harar, Ethiopia: Hindawi Limited. (2020) 140(2):387–96. doi: 10.1155/2020/7826519

19. Grema BA, Aliyu I, Michae GCl, Musa A, Fikin AG, Abubakar BM, et al. Typhoid ileal perforation in a semi-urban tertiary health institution in north-eastern Nigeria. S Afr Fam Pract. Family Medicine Department, Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital Kano, Nigeria: African Online Scientific Information System PTY LTD. (2018) 60(5):168–73. doi: 10.1080/20786190.2018.1481604

20. Henry K, Merab K, Leonard M, Ronald K, Nasser K. Elevated serum lactate as a predictor of outcomes in patients following major abdominal surgery at a tertiary hospital in Uganda. BMC Surg. England. (2021) 21(1):319. doi: 10.1186/s12893-021-01315-y

21. Hernandez MC, Kong VY, Aho JM, Bruce JL, Polites SF, Laing GL, et al. Increased anatomic severity in appendicitis is associated with outcomes in a South African population. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. (2017) 83(30th Annual Scientific Assembly of the Eastern-Association-for-the-Surgery-of-Trauma (EAST)):175–81. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001422

22. Legesse Laloto T, Hiko Gemeda D, Abdella SH. Incidence and predictors of surgical site infection in Ethiopia: prospective cohort. BMC Infect Dis. England. (2017) 17(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2167-x

23. Mawalla B, Mshana SE, Chalya PL, Imirzalioglu C, Mahalu W. Predictors of surgical site infections among patients undergoing major surgery at Bugando Medical Centre in northwestern Tanzania. BMC Surg. BioMed Central. (2011) 11(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-11-21

24. Onen BC, Semulimi AW, Bongomin F, Olum R, Kurigamba G, Mbiine R, et al. Surgical Apgar score as a predictor of outcomes in patients following laparotomy at Mulago National Referral Hospital, Uganda: a prospective cohort study. BMC Surg. (2020) 22(1):433. doi: 10.1186/s12893-022-01883-7

25. Osinaike S, Singh PP, Parampreet G, Nitin D, Arjun H, Uma S, et al. Nigerian surgical outcomes—report of a 7-day prospective cohort study and external validation of the African surgical outcomes study surgical risk calculator. Medicine (Baltimore). United States. (2019) 98(1):3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.06.003

26. Torborg A, Cronje L, Thomas J, Meyer H, Bhettay A, Diedericks J, et al. South African paediatric surgical outcomes study: a 14-day prospective, observational cohort study of paediatric surgical patients. Br J Anaesth. (2019) 122(2):224–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.11.015

27. Mohamed Ibrahim SM, Mahmoud El-Sheikh MA, Salama Abdelfattah AM. Effect of enhanced recovery after surgery protocol on postoperative outcomes of women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. SAGE Open Nurs. (2023) 9. doi: 10.1177/23779608231165948

28. Ntundu SH, Herman AM, Kishe A, Babu H, Jahanpour OF. Patterns and outcomes of patients with abdominal trauma on operative management from northern Tanzania: a prospective single centre observational study. BMC Surg. England. (2019) 19(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12893-019-0530-8

29. Mangi G, Mlay P, Oneko O, Maokola W, Swai P. Postoperative complications and risk factors among women who underwent caesarean delivery from northern Tanzania: a hospital-based analytical cross-sectional study. Open J Obstet Gynecol. Scientific Research Publishing, Inc. (2022) 12(04):243–57. doi: 10.4236/ojog.2022.124023

30. Laeke T, Tirsit A, Kassahun A, Sahlu A, Debebe T, Yesehak B, et al. Prospective study of surgery for traumatic brain injury in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: trauma causes, injury types, and clinical presentation. World Neurosurg. (2021) 149:e460–8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.02.003

31. Kintu A, Abdulla S, Lubikire A, Nabukenya MT, Igaga E, Bulamba F, et al. Postoperative pain after cesarean section: assessment and management in a tertiary hospital in a low-income country. BMC Health Serv Res. (2019) 19(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-3911-x

32. Atalabi OM, Osinaike BB. Do abnormal findings on hystero-salphingographic examination correlate with intensity of procedure associated pain? Afr J Reprod Health. Department of Radiology, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan: Women’s Health & Action Research Centre. (2014) 18(2):147–51. Available online at: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=103960117&site=ehost-live&scope=site25022152

33. Botchey IM, Hung YW, Bachani AM, Saidi H, Paruk F, Hyder AA. Understanding patterns of injury in Kenya: analysis of a trauma registry data from a national referral hospital. Surgery. (2017) 162(6):S54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.02.016

34. Traut AA, Kaminer D, Boshoff D, Seedat S, Hawkridge S, Stein DJ. Pre-operative education programme for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Afr J Reprod Health. United States: African Online Scientific Information System PTY LTD. (2019) 26(1):1–9. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v15i1.474

35. Klein K, Lefering R, Jungbluth P, Lendemans S, Hussmann B. Is prehospital time important for the treatment of severely injured patients? A matched-triplet analysis of 13,851 patients from the TraumaRegister DGU®. BioMed Res Int. Hindawi Limited. (2019) 2019:14. doi: 10.1155/2019/5936345

36. Abebe A, Kebede Z, Demissie DB. Practice of Pre-hospital emergency care and associated factors in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: facility-based cross-sectional study design. Open Access Emerg Med. Dove Press. (2023) 15:277. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S424814

37. Bashiri A, Savareh BA, Ghazisaeedi M. Promotion of prehospital emergency care through clinical decision support systems: opportunities and challenges. Clin Exp Emerg Med. The Korean Society of Emergency Medicine. (2019) 6(4):288. doi: 10.15441/CEEM.18.032

38. Abebe K, Negasa T, Argaw F. Surgical admissions and treatment outcomes at a tertiary hospital intensive care unit in Ethiopia: a two-year review. Ethiop J Health Sci. College of Public Health and Medical Sciences of Jimma University. (2020) 30(5):725. doi: 10.4314/EJHS.V30I5.11

39. Blume KS, Dietermann K, Kirchner-Heklau U, Winter V, Fleischer S, Kreidl L, et al. Staffing levels and nursing-sensitive patient outcomes: umbrella review and qualitative study. Health Serv Res. Health Research & Educational Trust. (2021) 56(5):885. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13647

40. Austin A, Gulema H, Belizan M, Colaci D, Kendall S, Tamil T, et al. Barriers to providing quality emergency obstetric care in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: healthcare providers’ perspectives on training, referrals and supervision, a mixed methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. BioMed Central Ltd. (2015) 15(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0493-4

41. Yasin C, Geleto A, Berhane Y. Referral linkage among public health facilities in Ethiopia: a qualitative explanatory study of facilitators and barriers for emergency obstetric referral in Addis Ababa city administration. Midwifery. (2019) 79:102–528. doi: 10.1016/J.MIDW.2019.08.010

42. Petterson SM, Rayburn WF, Liaw WR. When do primary care physicians retire? Implications for workforce projections. Ann Fam Med. Annals of Family Medicine, Inc. (2016) 14(4):344–9. doi: 10.1370/AFM.1936

43. de Varies N, Alidina S, Kuchukhidze S, Menon G, Citron I, Lama T, et al. The race to retain healthcare workers: a systematic review on factorsthat impact retention of nurses and physicians in hospitals. Inquiry. SAGE Publications. (2023) 60:161–5. doi: 10.1177/00469580231159318

44. Hussain S, Mubeen I, Ullah N, Mujeeb A. Modern diagnostic imaging technique applications and risk factors in the medical field: a review. BioMed Res Int. Hindawi Limited. (2022) 2022:1–19. doi: 10.1155/2022/5164970

45. Mehtar S, Sissolak D, Marais F, Mehtar S. Implementation of surgical site infection surveillance in low- and middle-income countries: a position statement for the international society for infectious diseases. Int J Infect Dis. Elsevier. (2020) 100:123. doi: 10.1016/J.IJID.2020.07.021

46. Duclos A, Chollet F, Pascal L, Ormando H, Carty MJ, Polazzi S, et al. Effect of monitoring surgical outcomes using control charts to reduce major adverse events in patients: cluster randomised trial. The BMJ. BMJ Publishing Group. (2020) 371:3840. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.M3840

47. Ferorelli D, Benevento M, Vimercati L, Spagnolo L. Improving healthcare workers’ adherence to surgical safety checklist: the impact of a short training. Front Public Health. Frontiers Media S.A. (2022) 9:732707. doi: 10.3389/FPUBH.2021.732707/FULL

48. von Eckardstein KL, Dohmes JE, Rohde V. Use of closed suction devices and other drains in spinal surgery: results of an online, Germany-wide questionnaire. Eur Spine J. Springer Verlag. (2016) 25(3):708–15. doi: 10.1007/S00586-015-3790-8

49. Adogwa O, Elsamadicy AA, Sergesketter AR, Shammas RL, Vuong VD, Khalid S, et al. Post-operative drain use in patients undergoing decompression and fusion: incidence of complications and symptomatic hematoma. J Spine Surg. OSS Press. (2018) 4(2):220. doi: 10.21037/JSS.2018.05.09

50. Goswami K, Austin MS. Intraoperative povidone-iodine irrigation for infection prevention. Arthroplast Today. Elsevier. (2019) 5(3):306. doi: 10.1016/J.ARTD.2019.04.004

51. Ataman MG, Sariyer G, Saglam C, Karagoz A, Unluer EE. Factors relating to decision delay in the emergency department: effects of diagnostic tests and consultations. Open Access Emerg Med. Dove Press. (2023) 15:119. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S384774

52. McQueen K, Coonan T, Ottaway A, Dutton RP, Nuevo FR, Gathuya Z, et al. Anesthesia and perioperative care. In: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 1): Essential Surgery. Semantic Scholar: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank (2015). p. 263–77. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-0346-8_CH15

53. Cohen ME, Gensini GF, Maritz F, Gurfinkel EP, Huber K, Timerman A, et al. Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis and risk for postoperative antibiotic-resistant infections. J Am Coll Surg. NIH Public Access. (2017) 225(5):631. doi: 10.1016/J.JAMCOLLSURG.2017.08.010

54. Issa ME, Eyad Al, Mohammed B, Pedro A, Basil J. Predictors of duration of postoperative hospital stay in patients undergoing advanced laparoscopic surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. (2005) 15(2):90–3. doi: 10.1097/01.SLE.0000160287.93535.A6

55. Billig J, Sears I, Erika D, Travis B, Breanna N, Jennifer F. Patient-reported outcomes: understanding surgical efficacy and quality from the patient’s perspective. Ann Surg Oncol. (2020) 27(1):56–64. doi: 10.1245/S10434-019-07748-3

56. Gunaratnam C, Bernstein M. Factors affecting surgical decision-making—a qualitative study. Rambam Maimonides Med J. Rambam Health Care Campus. (2018) 9(1):e0003. doi: 10.5041/RMMJ.10324

57. Khan PS, Dar LA, Hayat H. Predictors of mortality and morbidity in peritonitis in a developing country. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. Turkish Surgical Association. (2013) 29(3):124. doi: 10.5152/UCD.2013.1955

58. Bakhtiary F, Ahmad A, Sayed EL, Autschbach R, Benedikt P, Bonaros N, et al. Impact of pre-existing comorbidities on outcomes of patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement—rationale and design of the international IMPACT registry. J Cardiothorac Surg. (2021) 16:1. doi: 10.1186/S13019-021-01434-W

Keywords: quality measure, essential surgery, postoperative complications, meta-analysis, Sub-Saharan Africa

Citation: Yadeta DA, Manyazewal T, Demessie DB and Kleive D (2024) Incidence and predictors of postoperative complications in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Health Serv. 4:1353788. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2024.1353788

Received: 30 January 2024; Accepted: 17 April 2024;

Published: 9 May 2024.

Edited by:

Kelly Smith, University of Toronto, CanadaReviewed by:

Helen Higham, University of Oxford, United KingdomNicholas Meo, University of Washington Medical Center, United States

Charles Vincent, University of Oxford, United Kingdom

© 2024 Yadeta, Manyazewal, Demessie and Kleive. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniel Aboma Yadeta ZGFuaWVsLmFib21hQHNwaG1tYy5lZHUuZXQ=

Daniel Aboma Yadeta

Daniel Aboma Yadeta Tsegahun Manyazewal

Tsegahun Manyazewal Dereje Bayissa Demessie

Dereje Bayissa Demessie Dyre Kleive3

Dyre Kleive3