95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Health Serv. , 19 December 2023

Sec. Implementation Science

Volume 3 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2023.1242908

This article is part of the Research Topic Advancements and Challenges in Implementation Science: 2023 View all 12 articles

Belinda O’Hagan1

Belinda O’Hagan1 Marilyn Augustyn1

Marilyn Augustyn1 Rachel Amgott1

Rachel Amgott1 Julie White2

Julie White2 Ilana Hardesty2

Ilana Hardesty2 Candice Bangham3

Candice Bangham3 Amy Ursitti1

Amy Ursitti1 Sarah Foster1

Sarah Foster1 Alana Chandler1

Alana Chandler1 Jacey Greece3*

Jacey Greece3*

Background: There is growing demand for developmental and behavioral pediatric services including autism evaluation and care management. Clinician trainings have been found to result in an increase of knowledge and attitudes. This study utilizes Normalization Process theory (NPT) to evaluate a clinician training program and its effects on practice.

Methods: The year-long virtual training program about autism screening and care management included didactic portions and case presentations. Focus groups and interviews were conducted with primary care clinicians (n = 10) from community health centers (n = 6) across an urban area five months post-training. Transcripts were deductively coded using NPT to uncover barriers to implementation of autism screening and care, benefits of the training program, and areas for future training.

Results: Participants were motivated by the benefits of expanding and improving support for autistic patients but noted this effort requires effective collaboration within a complex network of care providers including clinicians, insurance agencies, and therapy providers. Although there were support that participants could provide to families there were still barriers including availability of behavior therapy and insufficient staffing. Overall, participants positively viewed the training and reported implementing new strategies into practice.

Conclusion: Despite the small sample size, application of NPT allowed for assessment of both training delivery and implementation of strategies, and identification of recommendations for future training and practice sustainability. Follow-up focus groups explored participants' practice five months post-program. Variations in participants' baseline experience and context at follow-up to enable application of skills should be considered when using NPT to evaluate clinician trainings.

For the past decade, autism diagnosis and demand for developmental-behavioral pediatric care has been steadily rising with the most recent autism prevalence reported at 1 in 36 children (1). Increased demand of developmental services combined with disinvestment (2) and disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic (3) has led to service delays. This is problematic given that benefits of early autism diagnosis and evidence-based care are well established (4, 5). Although screening is recommended to occur between 18 and 24 months of age (6), most children receive diagnosis after their third birthday, which is the cutoff for state-funded early intervention programs (7). Access to autism developmental care is especially strained in low-income and minoritized communities partly due to shortage of pediatric specialists (8).

A proposed strategy to address gaps in services is training more clinicians to conduct developmental screening and evaluations (9) instead of waiting for referral to specialists. The Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO®) has shown promise in equipping primary care clinicians (PCC) with skills and knowledge on a variety of clinical areas (10, 11) including autism. The ECHO model consists of a Hub institution comprised of topic experts responsible for delivering trainings and Spoke institutions comprised of PCCs (10) less expert in the topic. Researchers found that autism-focused ECHO programs resulted in increased participant knowledge and confidence (12–16). For example, Mazurek et al. (2019) found that a 12-month ECHO program increased clinicians' ability and self-efficacy to screen for autistic patients in Missouri, United States (13). There has been little evidence, however, that autism-focused ECHO programs result in practice change (17). Most studies on ECHO programs focusing on autism used a pre/post design but did not qualitatively assess practice change at follow-up (13–15, 18–20). Evaluating both pre/post knowledge/skills changes and application of practice within the service delivery setting are necessary to understand training impact.

The current study uses Normalization Process Theory (NPT) (21) as a framework to guide the Boosting Capacity to Screen and Care for Underserved Autistic Children ECHO Program (BCAEP), a training designed to enhance autism screening and care in primary care settings. The BCAEP training was conducted virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic and supported PCCs during major care disruptions. NPT posits that there are four components of practice change, namely coherence (i.e., what the new practice is), cognitive participation (i.e., one's and others' roles in the new practice), collective action (i.e., steps needed to accomplish the new practice), and reflexive monitoring (i.e., evaluation of the new practice) (21). NPT emphasizes individual and collective behaviors, in addition to attitudes and beliefs, which aids practice-focused queries (22). Past studies have utilized NPT to assess new practices in healthcare settings (22, 23). This study advances previous research by applying NPT to evaluate delivery and effectiveness of PCC trainings in urban safety-net settings as well as the extent to which learned skills and knowledge are applied in practice months after the training.

The BCAEP training was conducted virtually between November 2020 and October 2021 over 12 60-min sessions. Participants (n = 47) represented PCCs in seven health centers in the Greater Boston Area caring for safety-net populations. Trainings were facilitated by a senior developmental behavioral pediatrician with over 30 years of experience and an advanced practice clinician with 19 years of experience; both were affiliated with a safety-net academic medical institution. Each session consisted of didactic lectures and deidentified patient case discussions as per the ECHO model (10). Topics of the didactic lectures were determined based on an initial participant survey and were adjusted according to participants' interests. Examples of lecture topics were administration of different autism screening tools, engaging with patients in a culturally sensitive manner, and communicating an initial autism diagnosis to families.

This study was part of a larger mixed methods evaluation of the BCAEP training and represents the qualitative component of the evaluation. Focus groups and interviews with BCAEP PCCs (n = 10) were conducted to contextualize quantitative survey responses and provide actionable practice recommendations. Participants were asked to complete a brief pre-focus group assessment that gathered information about their practice (Table 1); nine responded to the survey and ten participated in focus groups. There were 30 pre-test (before first session), 19 mid-point (after sixth session), and 17 post-test (after twelfth session) survey responses, with nine matches from pre-test to post-test. Survey findings indicated an increase in participants' reported knowledge and self-efficacy in administering autism screeners and managing care in post-test compared to pre-test. Each of these quantitative findings warranted further exploration qualitatively and at a time when participants had a chance to implement the training learnings in practice.

Focus groups and interviews were conducted virtually approximately 6-months post-training using Zoom or in-person depending on participants' availability. This study was reviewed and approved as exempt by the Boston University Institutional Review Board (IRB #H-40718).

Participants for the qualitative assessments were recruited through convenience sampling of PCCs who attended the training. Participants represented PCCs from six out of seven (85.7%) eligible health centers. Recruitment emails consisting of abbreviated consent forms were sent. Participants were asked to complete a brief pre-focus group assessment that gathered information about their practice (Table 1).

Semi-structured focus groups and interviews were conducted in March 2022 using a guide (Appendix A) to gather information on individual level and clinic-level application of strategies taught in the BCAEP training as well as opinions about the training delivery. Questions were informed by survey findings, NPT constructs (21), and outcomes indicated on the logic model. Focus groups were conducted by two evaluation team members; a lead moderator and note-taker. One member was present at all focus group and interview sessions for consistency. Audio recordings were transcribed and verified by two different members for accuracy.

Deductive coding (24) using NPT constructs (21) and content analysis (25) were conducted on six transcripts. The coding team consisted of three evaluation team members who were trained to conduct qualitative analysis using NVivo12 (26). Each transcript was coded by two members. All three members then met to discuss discrepancies by consensus with the third member serving as tiebreaker if consensus was not reached.

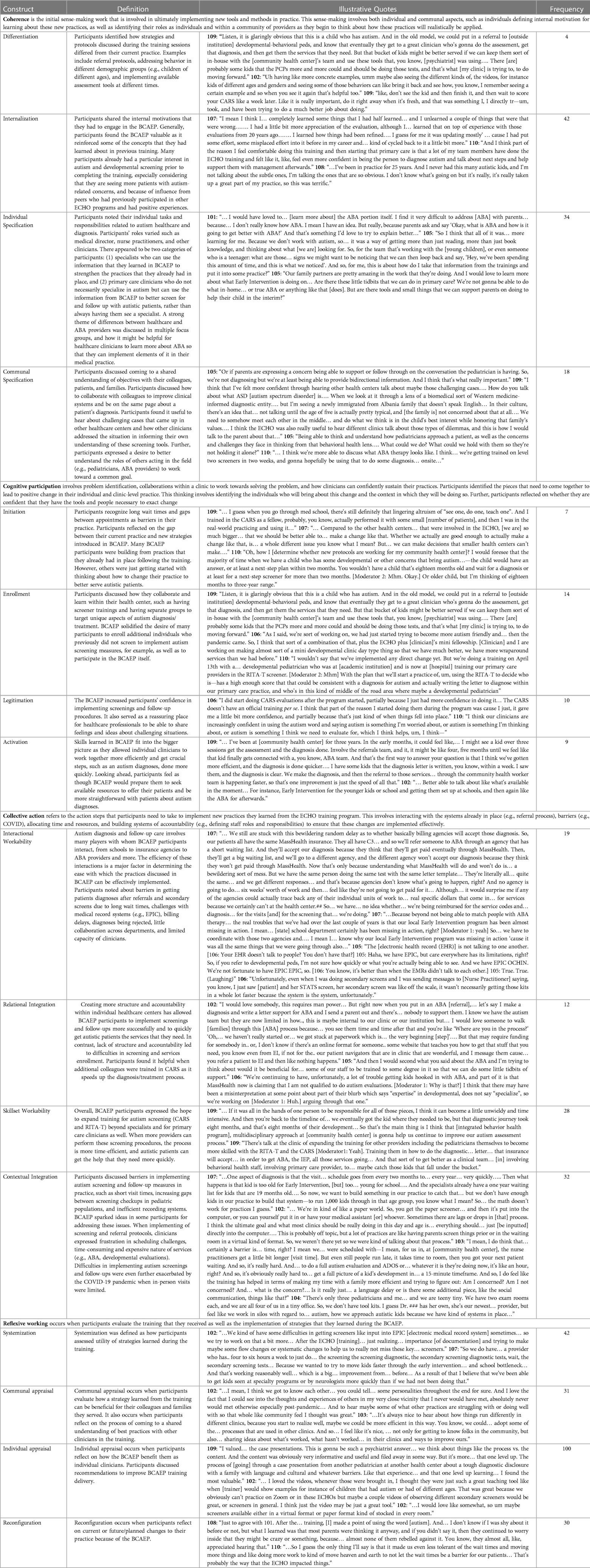

From the nine pre-focus group assessments, participants included physicians (n = 4), nurse practitioners (n = 4), and administrative leadership (n = 1) with most participants having 3–5 years (n = 3) and 11–20 (n = 3) years of experience. Specialties included pediatrics (n = 7), psychiatry (n = 1), and integrated behavior health (n = 1). On average, participants attended 10 out of 12 training sessions. Themes were organized by NPT constructs and presented with frequencies and illustrative quotes (Table 2) in order to provide a framework for actionable recommendations.

Table 2. Qualitative findings from focus groups and interviews with primary care clinicians organized using normalization process theory.

The following sections consisted of quotes coded with the corresponding constructs. NPT consisted of four constructs, each with four sub-constructs (21) that start with an understanding of the new practice (i.e., coherence), operationalizing change (i.e., cognitive participation), implementing the change (i.e., collective action), and ending with its evaluation (i.e., reflexive working) (22). While all constructs contributed to the findings and subsequent recommendations, reflexive working and collective action, given the role of clinicians to implement the concepts and assess the utility in practice, were most often mentioned.

Coherence occurs when an individual attempts to make sense of the new practice (21). This construct manifests through an individual's perception on a practice as well as their motivation and role for the new practice implementation.

In the current study, differentiation occurred when participants discussed how strategies taught in the training differed from their current practice (21). For example, one participant shared that “in the old model, we could put in a referral to [external institution] developmental-behavioral peds” but there are “kids [who] might be better served if we can keep them sort of in-house.” Another participant mentioned how behavioral observations may differ depending on the child's age and that “having more concrete examples… maybe also seeing… the videos… [of] kids of different ages and genders” could be helpful to deepen their understanding of screening procedures. Additionally, one participant described how the training reminded them to score screenings “right away when it's fresh.”

Internalization refers to motivations to implement a new practice, once participants have understood what the new practice entails (21). Motivations to engage in the training included an increase in patients with developmental support needs and reinforcement of previously learned concepts. Autism diagnosis and care management appeared to be important and timely skills to refine as one participant shared that they had “been in practice for 25 years and I never had this many autistic kids” and thus developmental care had “really taken up a great part of my practice.” Moreover, autism as a diagnosis had evolved considerably in the past few decades and this training allowed one clinician to “completely [learn] some things that I had half learned… and I unlearned a couple of things that were… wrong… on top of experience with those evaluations 20 years ago… I learned how things had been refined.”

Participants' roles and backgrounds in developmental care varied but they seemed to fall into two groups, namely specialists who could use tools and strategies introduced in the training to strengthen current practices and non-specialists who were looking for ways to improve care for autistic patients as they wait for a specialist appointment.

One participant mentioned that they “don't work with autism, so… [the training] was a way of getting… more than just book knowledge…” They described a desire to be better able to recognize “signs we might want to be noticing… And… how do I take that information from the trainings and put it into some practice?” Several participants discussed patient education with one participant describing they were looking for “tools and small things that we can support parents on doing to help their child in the interim [while waiting for Applied Behavior Analysis or ABA]?”

Participants discussed shared goals with colleagues, patients, and families. For example, one participant wanted to be better able to support parents who are “expressing concern or follow[ing] through on the conversation the pediatrician is having. So, we are not diagnosing but we’re at least being able to provide bidirectional information.” Participants described ways to improve their understanding of other staff roles. One participant expressed a desire to be “able to think and understand how pediatricians approach a patient,… What could we do? What could we hold with them so they’re not holding it alone?”

Participants engaged in problem identification, collaborations required to solve such problem, and discussed sustainability of the new practice. Participants identified the gap between the current and new practice, reorganized their work accordingly, and reflected on their ability to implement the new practice.

Participants reflected on the gap between their current practice and new strategies introduced in the training. When asked about potential care improvements, one participant “foresee[s] that the majority of the time, when we have a child who has some developmental or other concerns that bring autism…, the child would have an answer or at least a next-step plan within two months.” Another participant reflected on expanding their clinic's autism screening capacity by “dedicat[ing] some sort of FTE [full time equivalent] resource.” This was plausible because their clinic was larger “compared to the other health centers…” and thus could “make decisions that smaller health centers can't make.”

Participants discussed how they collaborated and learned, such as having autism screening trainings and separate groups to target unique aspects of autism diagnosis and care. One participant shared that their clinic was “doing a training… [for] our primary care providers in the RITA-T [Rapid Interactive Screening Test for Autism in Toddlers] screener.” Similarly, another participant shared their clinic's desire to have PCCs “… doing [developmental] tests” in-house before making a specialist referral, which may involve long wait times.

Participants discussed experiencing increased confidence in administering and advocating for autism screenings as they reflected on the value of strategies taught in the training. One participant “did start doing CARS [Childhood Autism Rating Scale] evaluations after the [training] started, partially because I just had more confidence in doing it.” Another participant described how PCCs in their workplace “are increasingly confident in using the autism word…”

Participants described their decision in enacting strategies introduced in the training. Specifically, how these strategies fit into clinic workflow by allowing PCCs to collaborate more efficiently and getting crucial steps in autism care done promptly. One participant shared that their clinic “ha[s] gotten more efficient, and the diagnosis is done quicker…” and “the referral… through the community health worker team is happening faster.” The knowledge of different services needed for different age groups was also conducive to efficient care as described by a participant who was “better able to talk about what [services are] available in the moment…”

Participants shared about implementing strategies introduced in the training within the context of current systems (e.g., referral process), barriers (e.g., the pandemic), time and resource allocations, and systems of accountability (e.g., staff roles and responsibilities).

Autism diagnosis and care involve multiple collaborators (e.g., school, insurance agency). The efficiency of interactions with such collaborators affected the implementation of strategies introduced in the training. Barriers included long wait times, complexity of electronic medical record (EMR) systems, billing delays, and limited bandwidth.

One participant described “bewildering random delay as to whether… billing agencies will accept [autism] diagnosis.” Even when patients “have the same [government] insurance” and presented with “the same [clinician] doing the same test with the same letter template,” they may receive varying responses based on the agencies' understanding of whether they would receive reimbursement. Additionally, EMR systems were described as “not talking to one another… So, if you refer to developmental peds [with a different EMR system], I’m not sure how quickly you’re actually being able to see [the referral].” Consequently, timely referrals did not always result in timely services.

Participants discussed structure and accountability within clinics needed for successful referrals to long-term services such as behavior therapy. One participant “would love someone to walk [families] through this [ABA] process because… you see [families] time and time after that and you’re like ‘Where are you in the process?’ ‘Oh,… we haven't really started or… we got stuck at paperwork which is… the very beginning [step].’” This issue did not only occur with ABA, as the participant continued that they “refer[red] a patient to EI [Early Intervention] and then like nothing happens.”

Participants described the distribution of responsibilities in implementing a new practice. Expanding training for autism screening beyond specialists could be key to timely referrals and care. One participant said, “If [screening and referral] was all in the hands of one person to…, it can become unwieldy and time intensive,” causing the “diagnostic journey [to take] eight months… of [the child's] development.” Multiple participants mentioned that it was helpful to have other PCCs who were able to conduct screenings. One participant felt “very fortunate to have [two colleagues conduct screenings]” as it “helped… take some of the stress of the long wait of getting an evaluation in our developmental clinic.”

Participants discussed barriers to autism screening and care such as gaps between appointments in pediatric patients. One participant described that “[pediatric visits] schedule goes from every two months to… every year… very quickly….” Due to age restrictions for some services, “that kid [becomes] too old for EI, [but] too… young for school.” Combined with “specialists already hav[ing] a one year waiting list,” the participant expressed a desire to “build something in our practice to catch [kids waiting for services].”

Another barrier discussed was “time, right?… It's obviously really hard to… get a full picture of a kid's development in… 15 min[s].” It is particularly challenging when “a full autism evaluation” takes “an hour.” Lastly, limited staffing and resources was cited as a barrier by a participant whose clinic consisted of “only three pediatricians and me… and we are teeny tiny.”

Individuals described how they evaluated and perceived the utility of strategies introduced in the training. Additionally, participants shared their evaluation of the training delivery and logistics.

Participants described how strategies introduced in the training impacted efficiencies of their practice. These changes were reported through informal observations. After the training, one participant “just realizing… importance [of documentation] and trying to make maybe some flow changes or systematic changes to help us to really not miss these key… screeners.”

Participants shared how they evaluated a new practice as a group. Participants discussed how the training provided an opportunity to come to a shared understanding of best practices with other clinicians. One participant shared that “it's always nice to hear about how things run differently in different clinics….” Learning more about other clinics also created a “community feel I thought was great.”

Participants reflected on how the training benefitted their individual practice. One participant “valued… the case presentations” because it was “that one level up” from didactic lectures. Another participant “loved the videos… I thought they were just such a great teaching tool” in a virtual environment. Participants also shared recommendations to improve future trainings, such as having more training in addressing “that lag time and the desperation of parents” and “… little interventions or pearls that we can share with parents…”

Participants reflected on current or planned changes to their care for autistic patients after the training. One participant recalled “ma[king] a point of using the word [autism]….” Another participant shared that the training had “brought to our primary care practice like a renewed focus on autism.” The enhanced understanding of best practices “made us even less tolerant of the wait times and… doing more work to… move heaven and earth to not let the wait times be a barrier for our patients.”

In this study, NPT was instrumental to organize qualitative data into actionable recommendations for a virtual PCC training program on autism screening and care. Qualitative data analysis revealed participants' motivations, attitudes, and perceived barriers regarding autism screening and care management strategies taught in the training. NPT was useful in highlighting both the process (training delivery) and outcome (practice change) aspects of evaluation.

Participants discussed the coherence construct or understanding of strategies introduced in the training. The training gave participants ideas to improve care by scoring autism screenings sooner, adapting behavioral observations based on patients' age, and providing more in-house care while waiting for external services. Benefits of early autism diagnosis and support are well established (27, 28) yet wait times for developmental-behavioral services in recent years grew due to increased demand (29) and disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic. Enhancement of in-house care could help bridge this gap (29). Practice recommendations include expansion of topics relevant to primary care (e.g., feeding, sleeping, medication dosages) and having a centralized location for resources about local services that PCCs can share with each other and patients/families.

Participants were also motivated by an observed increase in patients needing developmental care. Child mental health care was declared as being in a state of crisis partly due to the decline of services available and workforce capacity (2). Additionally, senior clinicians reported wanting to refine their knowledge about autism given recent major changes to autism as a diagnosis (30). Although comprehensive and systemic changes are needed, equipping clinicians with up-to-date knowledge could be a step in bridging gaps in services (31). Strategies that could help expand screening capacity included hands-on opportunities for clinicians to practice autism screening and modelling use of autism screening tools on real patients.

Participants also discussed components needed to implement strategies introduced in the training, which were coded using the cognitive participation construct. First, increasing the number of PCCs able to administer and advocate for autism screening could increase access, which aligns with past research (31). Participants described increased confidence in administering autism screening and educating families about autism, which in turn led to increased efficiency. Expansion of autism screening and care could address barriers to timely autism evaluation especially in low resource populations such as those served by this study's participants (32).

Second, a shared understanding of goals and accountability was needed as autism service referrals often involved multiple collaborators (e.g., behavior therapy providers, insurance agencies). Therefore, participants also expressed a desire for stronger understanding of how different services work, particularly EI and ABA as the latter is regarded as the golden standard for autism treatment (33). Including external experts on autism-related care could enhance clinicians' knowledge and establish connection with key collaborators. Past studies indicated that improvements were needed in follow up care of children who screened positive for autism (34, 35). Although additional research is needed to examine factors affecting low referral rates to follow up services (35), increased understanding of services may enhance PCCs' ability to navigate and advocate for timely service receipt.

Additionally, participants reflected on action steps they took to implement strategies introduced in the training, which were coded using the collective action construct. Barriers to autism screening and care were also discussed such as gaps between pediatric visits, EMR complexities, and inconsistent insurance requirements, all of which could contribute to service delays and aligned with prior research (9). Some barriers were outside clinicians' control, yet participants were committed to improving care whenever possible. Considerable investment is needed to expand the developmental-behavioral pediatric workforce and services (36), but enhancing aspects of care within a clinician's control may be one step closer to short-term care improvement.

For example, easy access of screening materials (e.g., printouts in exam rooms, centralized location of digital copies), clear follow-up protocols with defined responsibilities such that screenings have actionable outcomes, and enhanced patient education. Enhanced longitudinal family-clinician rapport that could result from these care improvements may further facilitate family's engagement with clinician recommendations, as found within the context of Latinx families (37).

Lastly, the training was well-received as evident from transcript text coded using the reflexive working construct. Participants cited the feeling of community with other attendees. Connection with other clinicians were found to be facilitators of clinician well-being (38, 39), which is crucial to maintain for an increasingly strained workforce (40, 41). The live, synchronous format of the training where trainers could engage attendees in real time appeared to be key in fostering such connection. Moreover, participants reported renewed focus on autism and decreased tolerance of wait times as they now had the tools and strategies to help remedy the situation in the short-term.

There were several limitations to this study. First, there was limited transferability of findings due to small sample size (n = 10) and self-selected participants from an urban area in northeastern United States. Participants, however, represented most of the eligible health centers (85.7%) with varying patient populations. Moreover, there was a large range in years of experience despite similar levels of prior interest in autism. Second, clinicians who participated in focus groups may be subject to social desirability bias as many knew and worked with each other. Findings however were gathered from a mix of focus groups and personal interview data.

NPT provided a helpful framework to organize qualitative data into actionable recommendations. Qualitative data analysis revealed participants' motivations, attitudes, and perceived barriers regarding autism screening and care management strategies taught in the training. Findings could guide efforts to enhance and sustain implementation of autism screening and care management in diverse urban settings. NPT could also be used to guide evaluations of other clinician training programs in addition to implementation of specific protocols in healthcare settings (23).

Similar to findings of a review of studies using NPT, we found overlaps between NPT constructs that made it difficult to assign a single construct to our data (22). For example, activation under cognitive participation and individual appraisal under reflexive working. Activation occurred when participants decided to enact a new practice whereas individual appraisal occurred when participants evaluated the value of a new practice after they had enacted it (21). However, participants tended to discuss these topics simultaneously; their decision to enact a new practice was implied by their reasoning involving the value of such practice. Although the overlap did not impact actionable recommendations out of the analyses, it is important to consider when using NPT.

Moreover, because participants varied in their baseline knowledge and experience with autism care, the novelty of their practice change and whether it was influenced by the training was unclear. As such, it was difficult to assign data to the construct differentiation under coherence, which referred to the contrast between existing vs. new practice. Another construct that was challenging to apply was systemization under reflexive working, which referred to participants' way of evaluating a new practice (21). The definition could apply to both formal (i.e., quality improvement studies) and informal (i.e., conversations) evaluation methods, but participants tended to share their thoughts about the training without sharing specifically how they gathered data to come to their conclusions. It was largely implied that they evaluated the training through personal observations and informal conversations with colleagues. Lastly, the current study focused on two innovations, namely the tools and strategies introduced in the training as well as the training delivery itself (i.e., virtual, year-long, inter-professional training). Careful attention was paid to specify which innovation codes applied.

PCC training on autism screening and care management could potentially address service access issues. There were distal barriers outside of a clinician's control, but equipping clinicians with knowledge and self-efficacy about autism care may help address proximal barriers within their control. NPT allowed for detailed assessment of process and outcome evaluations for a PCC training program, identification of gaps, and practice recommendations. Moreover, NPT was useful in highlighting both the process (training delivery) and outcome (practice change) aspects of evaluation and providing a framework for delivering recommendations to program implementers. Lastly, NPT could be used as a guiding framework for other clinician training programs, however, defining the new practice of interest may need to be further clarified when working with a participant group with varying baseline knowledge.

The authors cannot provide raw data per IRB regulations. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The studies involving humans were approved by Boston University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because Verbal consent was obtained by clinicians to participate in this evaluation.

BO led data collection and qualitative analysis and drafted the manuscript. MA, JW, and IH conceptualized the study, delivered the program, and reviewed manuscript drafts. RA delivered the program and reviewed manuscript drafts. CB assisted in data analysis and reviewed manuscript drafts. AU, SF, and AC conducted data analysis and reviewed manuscript drafts. JG conceptualized the study, oversaw data collection and analysis, drafted manuscript, and reviewed manuscript drafts. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the Deborah Munroe Noonan Memorial Research Fund.

We would like to acknowledge the health system and health centers for their investment of time and participation in this project and evaluation. We would also like to thank Catherine Pagliaro for coordinating the training sessions. Lastly, we would like to thank Tiffany Liu and Alyson Codner for statistical analysis of survey responses.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Maenner MJ, Warren Z, Williams AR, Amoakohene E, Baikan AV, Bilder DA, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism Spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. (2023) 72:1–14. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1

2. Karpman HE, Frazier JA, Broder-Fingert S. State of emergency: a crisis in children’s mental health care. Pediatrics. (2023) 151:e2022058832. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-058832

3. Bellomo TR, Prasad S, Munzer T, Laventhal N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with autism spectrum disorders. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. (2020) 13:349–54. doi: 10.3233/PRM-200740

4. Elder JH, Kreider CM, Brasher SN, Ansell M. Clinical impact of early diagnosis of autism on the prognosis and parent–child relationships. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2017) 10:283–92. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S117499

5. Fernell E, Eriksson MA, Gillberg C. Early diagnosis of autism and impact on prognosis: a narrative review. Clin Epidemiol. (2013) 5:33–43. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S41714

6. Johnson CP, Myers SM. American Academy of pediatrics council on children with disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. (2007) 120:1183–215. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2361

7. Brinster MI, Brukilacchio BH, Fikki-Urbanovsky A, Shahidullah JD, Ravenscroft S. Improving efficiency and equity in early autism evaluations: the (S)TAAR model. J Autism Dev Disord. (2023) 53:275–84. doi: 10.1007/s10803-022-05425-1

8. Broder-Fingert S, Mateo C, Zuckerman KE. Structural racism and autism. Pediatrics. (2020) 146:e2020015420. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-015420

9. Wieckowski AT, Zuckerman KE, Broder-Fingert S, Robins DL. Addressing current barriers to autism diagnoses through a tiered diagnostic approach involving pediatric primary care providers. Autism Res. (2022) 15:2216–22. doi: 10.1002/aur.2832

10. Arora S, Geppert CMA, Kalishman S, Dion D, Pullara F, Bjeletich B, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: project ECHO. Acad Med. (2007) 82:154–60. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f68

11. Zhou C, Crawford A, Serhal E, Kurdyak P, Sockalingam S. The impact of project ECHO on participant and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Acad Med. (2016) 91:1439–61. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001328

12. Buranova N, Dampf M, Stevenson B, Sohl K. ECHO autism: early intervention connecting community professionals to increase access to best practice autism intervention. Clin Pediatr (Phila). (2022) 61(8):518–22. doi: 10.1177/00099228221090710

13. Mazurek MO, Curran A, Burnette C, Sohl K. ECHO autism STAT: accelerating early access to autism diagnosis. J Autism Dev Disord. (2019) 49:127–37. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3696-5

14. Mazurek MO, Stobbe G, Loftin R, Malow BA, Agrawal MM, Tapia M, et al. ECHO autism transition: enhancing healthcare for adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. (2020) 24:633–44. doi: 10.1177/1362361319879616

15. Nowell KP, Christopher K, Sohl K. Equipping community based psychologists to deliver best practice ASD diagnoses using the ECHO autism model. Children’s Health Care. (2020) 49:403–24. doi: 10.1080/02739615.2020.1771564

16. Vinson AH, Iannuzzi D, Bennett A, Butter EM, Curran ABB, Hess A, et al. Facilitator reflections on shared expertise and adaptive leadership in ECHO autism: center engagement. J Contin Educ Health Prof. (2022) 42:53–9. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000395

17. Mazurek MO, Parker RA, Chan J, Kuhlthau K, Sohl K, for the ECHO Autism Collaborative. Effectiveness of the extension for community health outcomes model as applied to primary care for autism: a partial stepped-wedge randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr (2020) 174:e196306. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6306

18. Dreiling NG, Cook ML, Lamarche E, Klinger LG. Mental health project ECHO autism: increasing access to community mental health services for autistic individuals. Autism. (2022) 26:434–45. doi: 10.1177/13623613211028000

19. Hardesty C, Moody EJ, Kern S, Warren W, Cooley Hidecker MJ, Wagner S, et al. Enhancing professional development for educators: adapting project ECHO from health care to education. Rural Special Education Quarterly. (2020) 40:42–52. doi: 10.1177/8756870520960448

20. Mazurek MO, Brown R, Curran A, Sohl K. ECHO autism: a new model for training primary care providers in best-practice care for children with autism. Clin Pediatr (Phila). (2017) 56:247–56. doi: 10.1177/0009922816648288

21. May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology. (2009) 43:535–54. doi: 10.1177/0038038509103208

22. May CR, Cummings A, Girling M, Bracher M, Mair FS, May CM, et al. Using normalization process theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2018) 13:80. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0758-1

23. McEvoy R, Ballini L, Maltoni S, O’Donnell CA, Mair FS, MacFarlane A. A qualitative systematic review of studies using the normalization process theory to research implementation processes. Implementation Sci. (2014) 9(2):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-2

24. Brehaut JC, Eva KW. Building theories of knowledge translation interventions: use the entire menu of constructs. Implement Sci. (2012) 7(114):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-114

25. Siminof LA, Jacoby L, Forman J, Damschroder L. “Qualitative content analysis.,” empirical research for bioethics: A primer. Oxford: Elsevier Publishing (2008). 39–62.

26. Best Qualitative Data Analysis Software for Researchers | NVivo. Available at: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (Accessed July 22, 2022).

27. Clark MLE, Barbaro J, Dissanayake C. Continuity and change in cognition and autism severity from toddlerhood to school age. J Autism Dev Disord. (2017) 47:328–39. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2954-7

28. Clark MLE, Vinen Z, Barbaro J, Dissanayake C. School age outcomes of children diagnosed early and later with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. (2018) 48:92–102. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3279-x

29. Kanne SM, Bishop SL. Editorial perspective: the autism waitlist crisis and remembering what families need. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2021) 62:140–2. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13254

30. Volkmar FR, McPartland JC. From kanner to DSM-5: autism as an evolving diagnostic concept. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2014) 10:193–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153710

31. Guan X, Zwaigenbaum L, Sonnenberg LK. Building capacity for community pediatric autism diagnosis: a systemic review of physician training programs. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2022) 43:44–54. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000001042

32. Aylward BS, Gal-Szabo DE, Taraman S. Racial, ethnic, and sociodemographic disparities in diagnosis of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr. (2021) 42:682–9. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000996

33. McPhilemy C, Dillenburger K. Parents’ experiences of applied behaviour analysis (ABA)-based interventions for children diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder. Br J Spec Educ. (2013) 40:154–61. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12038

34. Moore C, Zamora I, Patel Gera M, Williams ME. Developmental screening and referrals: assessing the influence of provider specialty, training, and interagency communication. Clin Pediatr (Phila). (2017) 56:1040–7. doi: 10.1177/0009922817701174

35. Wallis KE, Guthrie W, Bennett AE, Gerdes M, Levy SE, Mandell DS, et al. Adherence to screening and referral guidelines for autism spectrum disorder in toddlers in pediatric primary care. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0232335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232335

36. Lord C, Charman T, Havdahl A, Carbone P, Anagnostou E, Boyd B, et al. The lancet commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. Lancet. (2022) 399:271–334. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01541-5

37. Zuckerman KE, Lindly OJ, Reyes NM, Chavez AE, Macias K, Smith KN, et al. Disparities in diagnosis and treatment of autism in latino and non-latino white families. Pediatrics. (2017) 139:1–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3010

38. Olson K, Marchalik D, Farley H, Dean SM, Lawrence EC, Hamidi MS, et al. Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout and improve professional fulfillment. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2019) 49:100664. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2019.100664

39. Southwick SM, Southwick FS. The loss of social connectedness as a major contributor to physician burnout: applying organizational and teamwork principles for prevention and recovery. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:449–50. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4800

40. Bridgemohan C, Bauer NS, Nielsen BA, DeBattista A, Ruch-Ross HS, Paul LB, et al. A workforce survey on developmental-behavioral pediatrics. Pediatrics. (2018) 141:e20172164. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2164

41. Vinci RJ. The pediatric workforce: recent data trends, questions, and challenges for the future. Pediatrics. (2021) 147:e2020013292. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-013292

1. What skills are you applying, meaning what are you able to do differently because of what you learned from the ECHO Autism Program? Are any skills missing from what you received in the ECHO Autism Program? (Probe for screening, referral, treatment)

2. What knowledge did you gain, meaning what did you learn that you can apply to your practice and relay information to your patients? Are any pieces of knowledge missing? (Screening tools, referral protocols, resources)

3. How did the program change your perspective on the education and care of your patients? (Probe for comfort of using terminology, confidence in referring, managing care)

1. How has your clinic’s practice changed because of your participation in in the ECHO Autism Program? Who have been implementing these changes? (Probe for administrative support, connection/community within the practice)

2. What are some of the benefits to implementing the strategies from the ECHO Autism Program training given your current clinic context? Who are the recipients of these benefits? (Probe for EMR supports, protocols for referral and screening, sense of community)

3. How do you determine if strategies from the ECHO Autism Program training are working for your clinic? (Probe for patient satisfaction, staff satisfaction, burnout factors (e.g., feeling worthwhile at work, work is satisfying/meaningful, they are contributing professionally in ways they value)

1. What parts of the ECHO Autism Program training do you value the most? (Probe for parts that can be transferrable to other clinics and avenues.)

2. What could have been done differently during the training to better meet the learning objectives? Reflect on your experiences with case presentation and discussion. (Probe for support from clinic administration, further resources, etc.)

Keywords: implementation research, normalization process theory, qualitative evaluation, autism, extension for community healthcare outcomes

Citation: O’Hagan B, Augustyn M, Amgott R, White J, Hardesty I, Bangham C, Ursitti A, Foster S, Chandler A and Greece J (2023) Using normalization process theory to inform practice: evaluation of a virtual autism training for clinicians. Front. Health Serv. 3:1242908. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2023.1242908

Received: 19 June 2023; Accepted: 4 December 2023;

Published: 19 December 2023.

Edited by:

Nick Sevdalis, National University of Singapore, SingaporeReviewed by:

Tim Rapley, Northumbria University, United Kingdom© 2023 O'Hagan, Augustyn, Amgott, White, Hardesty, Bangham, Ursitti, Foster, Chandler and Greece. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jacey Greece amFibG9vbUBidS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.