- 1Department of Public Health, Nice University Hospital, University of Côte D'Azur, Nice, France

- 2Clinical Research Unit (UR2CA), Nice University Hospital, University of Côte D'Azur, Nice, France

Effective public health interventions at local level must involve communities and stakeholders beyond the health services spectrum. A dedicated venue for structured discussion will ensure ongoing multi-sectoral collaboration more effectively than convening ad hoc meetings. Such a venue can be created using existing resources, at minimal extra cost. The University Hospital in Nice (France) has established an Open Arena for Public Health which can serve as a model for promoting collaborative partnerships at local level. The Arena has been successful in implementing sustainable interventions thanks to a set of principles, including: non-hierarchical governance and operating, fair representation of stakeholders, consensus as to best available evidence internationally and locally, policy dialogues: open, free-flowing discussions without preconceived solutions, and an experimental approach to interventions.

1. Introduction

As we move towards the second quarter of the 21st century, evidence-based medicine has taken the lead on expert clinical practice. Likewise, we are increasingly moving towards evidence-informed health policies and away from interventions guided by expertise or political will only. In parallel to the emergence of evidence to support decision-making in medicine and public health, experience is demonstrating the key role of involving communities in the design of public health interventions (1–3). Collaborative governance and community-based participatory research have made remarkable strides since the turn of the century. Increasingly, funders are requiring not only community participation in health promotion research (4), but cultural competency of relevant stakeholders and officials (5).

Stakeholder involvement in the design of interventions is necessary not only to determine their characteristics and scope, but also their uptake and ultimately their sustainability, without which even the most carefully designed initiatives will not produce the desired effects (6). Historically, many public health campaigns have been based on informing the public on the assumption that knowledge alone is enough to change behavior. But now we know that communities must also have the means to change their behavior.

The World Health Organization is increasingly promoting policy dialogues as the key knowledge translation tool for evidence-informed policy making (7). “Policy dialogues”—while not yet benefiting from an official definition—are broadly described as an interactive knowledge-sharing mechanism among a comprehensive range of stakeholders. Their use is encouraged for response to major public health problems, especially those which “resist solution, where there is no clear “right” answer and a number of different interests, priorities and values are in tension” (8). For instance, the WHO recently called for policy dialogues to tackle the obesity epidemic across the European region (9).

For the past 15 years, the Open Arena for Public Health (Espace Partagé de Santé Publique) in the department of Alpes Maritimes (South Eastern France) has been bringing together academics, decision-makers, and community representatives on a regular basis to tackle local health challenges. Although not formally designated as such, the de facto mechanism of concertation has been policy dialogues. Elsewhere, policy dialogues have been convened mostly on an ad hoc basis (10) (11, 12), but there is growing recognition that their systematic use—as in Alpes Maritimes—would be beneficial to promoting regular interaction of stakeholders in a given community setting (13, 14).

In this policy brief, we make recommendations for enhancing multi-sectorial collaboration via a dedicated space such as the Open Arena for Public Health in Nice which engages in ongoing policy dialogues.

2. Functioning of the open arena for public health

2.1. The open arena and the public health landscape in France

France has a long history of centralization. The country is divided administratively into 5 regions and 101 departments (including overseas). Piloting and coordination of health policies are ensured at the national level and translated locally via regional health agencies.

Any public health/health promotion intervention which does not fall directly within the prerogative of the department or the municipality (such as school lunches or sports venues) must be approved for funding by the regional health agency. Broadly speaking, the public health landscape remains rigid and top heavy with limited scope for adapting national policies to local contexts.

To overcome this rigidity, the University Hospital of Nice instituted an Open Arena for Public Health to be managed by the hospital's Department of Public Health. The aim of the Open Arena has been to improve the health status of communities living in Alpes Maritimes through collaborative partnerships among community representatives, civil society organizations, local health stakeholders, and academic institutions. From its inception, it has sought to federate across parties and respond in a timely fashion to evolving health determinants and population expectations, in line with the principles of health promotion and the new public health. The Arena was established using existing resources—i.e., the time and expertise of staff within the Department of Public Health—thus incurring no extra cost.

The Arena operates via a Steering Committee and an Operational Board. Project selection and decision-making are based on public health data, academic expertise, and community participation using a policy dialogue mechanism. The Open Arena also carries out consultative and technical support activities. As such, it breaks down administrative barriers among existing institutions and fosters collective thinking and collaboration among professionals and community members unused to working together. Community representatives are identified by a snowballing process, starting with civil society organizations and local stakeholders known to the municipality or greater Nice area. All partners volunteer their time to ensure cost containment. When funding for a specific project is required, it will be sought within the budgets of partnering institutions.

The Open Arena will meet whenever a complex public health priority is identified, such as poor uptake of cancer screening (15), or medical desertification in rural areas. As a department of France suffering from marked social disparities, the Arena is particularly concerned with health problems linked to inequalities and inequities. The process for convening the Arena can be reactive, e.g., in response to community concerns over a health-related issue such as pollution, or proactive as when the Steering Committee alerts members to a major health concern such as high prevalence of pediatric obesity in certain Nice neighborhoods. Discussion is rooted in scientific evidence provided by the Department of Public Health, but evolves freely as participants share their knowledge, experience, and skills. Typically, this encourages thinking out of the box and leads to innovative proposals involving new partnerships.

2.2. Example of an open arena intervention: preserving autonomy for the elderly

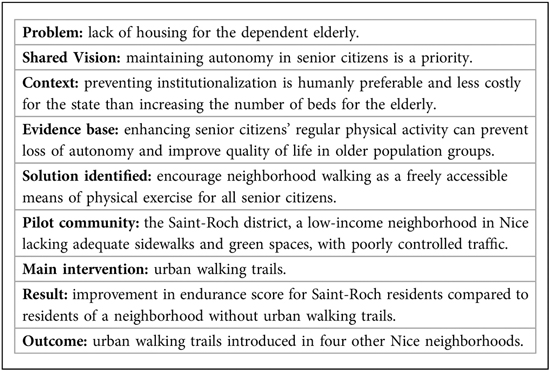

One of the first requests made to the Arena's Steering Committee was to think about new housing solutions for the dependent elderly. Several policy dialogues were convened, involving a wide range of stakeholders. The discussions shifted their focus from housing to the preservation of autonomy in senior citizens and came up with a comprehensive model for reducing loss of autonomy in the elderly. In line with the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, the Open Arena wished to empower older individuals with regard to their health through enhanced physical activity and ongoing social interaction. Over the past decades, several community-based health interventions have been developed to promote healthy ageing, specifically through physical activity (16–18).

The pilot intervention (the 4-S initiative: Saint-Roch—Sport—Solidarity—Senior Citizens) consisted of improving the urban environment of a socially disadvantaged neighborhood of Nice (Box 1). Consultations were carried out with local senior citizens, thus leading to a walking route in line with the expectations of those who would use them (19). The walking routes were also a means of strengthening social ties through meeting places such as open areas and shops. The evaluation of the intervention indicated enhanced quality of life for older individuals through a holistic approach including physical, social and mental well-being (20). Importantly, the intervention fit within the model of integrating progressive loss of autonomy into the life course of older individuals. This model seeks to create an environment conducive to “better ageing”, including a network of medical and social support, and suitable housing for those who become too dependent to live in their own home. Thus, institutionalized living is no longer the prime issue to be addressed, but emerges as a solution for the most vulnerable. Further, housing for the dependent elderly is foreseen within the neighborhood where they have previously lived.

Multi-sectoral partnering such as the Open Arena for Public Health is unique in France, yet can be replicated in almost any setting. In order for it to achieve its purpose, a number of actions can be recommended.

3. Actionable recommendations

3.1. Strong but non-hierarchical governance

The Open Arena for Public Health does not have a specific legal structure or dedicated funding. It operates through a Steering Committee, an Operating Board, and Project Groups. It is operational and flexible, and encourages both a bottom-up and top-down approach, although the ultimate decision-making power remains with the Steering Committee. Members volunteer to join working groups and dedicate their working time, thus allowing the Arena to function without incurring extra cost. In face of a specific challenge or problem, leaders will articulate a vision which can be shared by all, but they do not plan any interventions beforehand or present preconceived ideas. Instead, policy dialogue and interaction allows stakeholders to come up with original proposals and solutions in line with the shared vision.

Specifically:

• The Steering Committee is the strategic core. It includes all decision-makers responsible for identifying partners, funding sources, and communication strategies. The Steering Committee maintains trust and cooperation among stakeholders and creates an environment favorable to change over time. It meets once a year.

• The Operating Board, made up of stakeholders and academics, meets at least three times a year. It develops the strategies required for change to materialize. Each time a new project is launched, a dedicated team is set up and evaluation protocols are developed. The Operating Board is responsible for coordinating these teams and making recommendations to the Steering Committee on the basis of collective discussions.

• The Project Groups bring together stakeholders (often technical experts) directly involved in implementing interventions. They are in charge of representing communities’ needs and developing approaches which allow individuals to be actors of their own health. The Project Groups also identify and report any problems encountered in the field and suggest solutions. They meet at different times depending on how the intervention is progressing and which actions need to be taken.

This three-tiered structure is intended to be both adaptive and self-organizing. Participants have freedom of action and influence each other collectively. Such room for maneuver, sharing of experience, and pooling of skills leads to creative experimentation in responding to local health challenges. Participants in Open Arena discussions must feel they are on equal footing when analyzing evidence and seeking solutions. As observed in the “Model of Research-Community Partnership”, described by Brookman-Frazee, facilitating factors for collaborative processes depend on non-hierarchical, collegial relations among partners based on mutual respect and trust (21).

3.2. Fair representation of stakeholders

In face of a given challenge, it is essential that the entire range of stakeholders be represented, and contribute to the policy dialogue. Failure to invite a key stakeholder can compromise the identification of a workable solution and/or its uptake in the community.

Bringing together representatives from different organizations, communities, disciplines, backgrounds, and cultures to exchange knowledge, discuss evidence, and suggest ways forwards always presents challenges. There must be mutual respect and acceptance that consensus cannot always be secured as a single set of actions, but will often take the form of a multiplicity of perceived solutions (a hallmark of policy dialogues).

For instance, regarding the model of loss of autonomy in the elderly and the 4-S initiative, academic and public health professionals contributed their knowledge and expertise; community representatives provided citizen's feedback regarding their specific social, environmental, and cultural context; and municipal policymakers were able to discuss financing in the context of competing priorities so as to make the best use of public funds.

3.3. A shared vision, but not preconceived solutions

While the policy dialogue itself remains an open and free-flowing discussion with minimal rules, it is essential that the participants start out with a shared vision of the problem at hand, and the importance for public health of addressing it adequately.

Prior to elaborating the walking trails intervention in a disadvantaged Nice neighborhood, all participants agreed that solutions needed to be found in face of lack of housing for the dependent elderly and, generally speaking, that more needed to be done to promote healthy ageing in the city of Nice. They were thus fully engaged in the need for and process of change.

3.4. Thinking global—acting local

The Open Arena's initiatives are aligned with major international objectives such as reducing obesity or creating healthy cities, but conceived on a very local scale—most often in terms of neighborhoods. Beyond considerations of experimentation and tailored interventions, the neighborhood is the nexus of everyday life in which individual and collective responsibility take on concrete meaning.

In the United States, the “Active Living by Design” national program was established to help 25 programs resulting from interdisciplinary collaborative partnerships create healthy urban environments and increase physical activity and social support within neighborhoods (22, 23). This kind of community action model has been successfully applied in other countries (24, 25) and served as an inspiration to the Open Arena in Nice when developing its own interventions to promote healthy ageing.

Taking a territorial approach (districts) means that population needs—both expressed and unexpressed—can be deliberately considered. Interventions at different levels of the health continuum contribute to promoting healthy lifestyles through educational and environmental strategies. These actions should be developed according to a life course approach, by intervening upstream on the determinants of health to prevent the loss of autonomy, and better meet the needs of an ageing population.

3.5. Discussions based on evidence

The golden rule for policy dialogues is that they be based on available evidence. This evidence should be summarized in plain language and shared with all participants before the initial meeting. Evidence is based on national and international data (Santé Publique France, WHO, scientific publications, etc.) but also draws on local aggregated data made available by the national income tax and statistics agencies. The strength and appropriateness of this evidence may be debated, but it serves as a starting block on which to build. Often, this evidence needs to be completed.

In what led up to the enhanced physical activity initiative, social science researchers introduced the life course approach to discussions around healthy ageing and relevant information was made available to all participants.

Interestingly, partners involved in the dialogues initially each had their own project in mind for enhancing physical exercise for the elderly. But the discussions led to a synergetic effect and identified urban walking trails as the best practicable solution.

Focus group discussions with neighborhood residents collected experiences of physical activity, requirements to improve walking opportunities, and proposals to overcome perceived difficulties. Participants clearly stated that heavy traffic, sidewalk parking, unavailable pedestrian passages or limited vision at crossings led to a sense of insecurity and discouraged them from walking in their own neighborhood. They then proposed their own itinerary which included congenial spots and avoided unpleasant ones. Such specific input was obviously crucial to creating urban trails which people would actually use.

3.6. Experimental approach

The beauty of policy dialogues is that they can, and often do, lead to new ideas (or old ideas which have been forgotten). All the health promotion interventions conducted by the Open Arena are first tested on a small scale (usually a pilot study within a target community) and replicated only if successful.

The Saint-Roch district was chosen as the target neighborhood for the 4-S Initiative being a low-income neighborhood in the city center. Another low-income neighborhood was selected as the control. The goal was to assess the combined impact of an organized urban walking circuit and individual coaching on female senior citizens’ physical well-being and quality of life. Older women in the target and control districts were randomly allocated to receive coaching. The invention was funded by the regional health agency and targeted over 4,000 citizens above the age of 64. At three months, the endurance score was higher in the improved urban environment group, whether coupled with coaching or not (20).

4. Conclusion

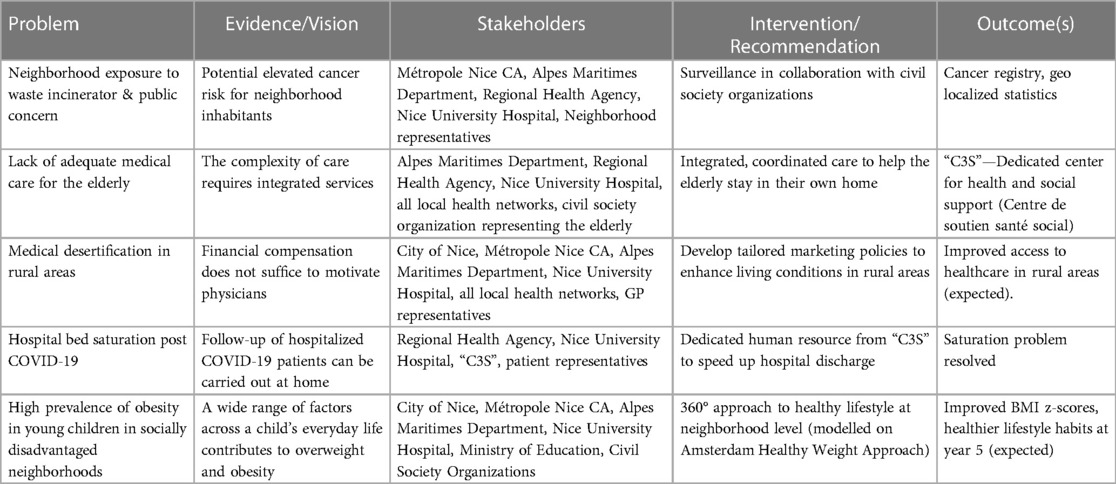

The Open Arena for Public Health is an example of a local initiative which has led to substantial social and political innovation in improving population health in Alpes Maritimes (Table 1). The Arena clearly arose within the premises of the new public health, meaning “community participation in health policy development and implementation of programs, [emphasis on] primary health care and health promotion, and inter-sectoral cooperation involving agencies whose influence impinges on health” (26). It seeks to bridge the gap between academics, on the one hand, and policy makers and implementers on the other, in order to improve community health.

Table 1. Examples of interventions resulting from policy dialogues within the open arena for public health.

That is how—when it was called upon to deal with the problem of lack of housing for the dependent elderly—it focused on means to improve senior citizens’ overall health status, thus allowing them to remain in their own homes for as long as possible. The actions decided upon involved a wide spectrum of stakeholders, well beyond the health system. Such diversification of stakeholders, skills, and expertise clearly enhances both tacit and explicit knowledge sharing, and also leads to varied interpretations and intermediary solutions arising from mutual exchange and learning. Within this context, academics have played a key role by framing discussions within the most recent concepts in public health.

Arguably the principle hurdle which the Arena has faced time and time again is maintaining the horizontal approach to problems in a country where the model of governance is overwhelmingly top-down. If constant efforts are not made to keep the balance among stakeholders and maintain fluid cross-over as well as top-down-bottom-up processes, initiatives will fall flat or only partially reach their objectives.

The COVID-19 pandemic has once more highlighted the impact of social inequities on health outcomes (27). Solutions to address the consequences of such inequities must be based on evidence and involve actors beyond the health system. Yet policy interventions based on evidence entail huge efforts to harness available knowledge, share it, overcome conflicting views and priorities, and translate it into action.

We believe that the Open Arena for Public Health can serve as a model for ensuring ongoing exchange and answers to complex health challenges at community level, allowing change and innovation to come about as a result of collective intelligence and ongoing policy dialogues.

Author contributions

CP contributed to the conception and critical revision of the article. MB contributed to the conception of the article and was responsible for its drafting. LB contributed to the conception and critical revision of the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Jean Rochon (1938–2021) to the concept and construct of the Espace Partagé de Santé Publique, for which he acted as international advisor.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Totten MK. Collaborative governance the key to improving community health. Available at: https://trustees.aha.org/articles/995-collaborative-governance-key-to-community-health.

2. Hoekstra F, Mrklas KJ, Khan M, McKay RC, Vis-Dunbar M, Sibley KM, et al. A review of reviews on principles, strategies, outcomes and impacts of research partnerships approaches: a first step in synthesising the research partnership literature. Health Res Policy Syst. (2020) 18(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-0544-9

3. Ortiz K, Nash J, Shea L, Oetzel J, Garoutte J, Sanchez-Youngman S, et al. Partnerships, processes, and outcomes: a health equity-focused scoping meta-review of community-engaged scholarship. Annu Rev Public Health. (2020) 41:177–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094220

4. Harting J, Kruithof K, Ruijter L, Stronks K. Participatory research in health promotion: a critical review and illustration of rationales. Health Promot Int. (2022) 37(Supplement_2):ii7–20. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daac016

5. Jongen CS, McCalman J, Bainbridge RG. The implementation and evaluation of health promotion services and programs to improve cultural competency: a systematic scoping review. Front Public Health. (2017) 5:24. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00024

6. Duke M. Community based participatory research. Oxford research encyclopaedias. Anthropology. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190854584.013.225

7. EVIPNet. Policy dialogue preparation and facilitation checklist. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/323153/EVIPNET-PD-preparation-facilitation-checklist.pdf.

8. Mitchell P, Reinap M, Moat K, Kuchenmüller T. An ethical analysis of policy dialogues. Health Res Policy Syst. (2023) 21(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12961-023-00962-2

9. WHO begins subregional policy dialogues to fight obesity. Available at: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/24-06-2022-who-begins-subregional-policy-dialogues-to-fight-obesity (Consulted 29.03.23).

10. Leslie K, Bartram M, Atanackovic J, Chamberland-Rowe C, Tulk C, Bourgeault IL. Enhancing the capacity of the mental health and substance use health workforce to meet population needs: insights from a facilitated virtual policy dialogue. Health Res Policy Syst. (2022) 20(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12961-022-00857-8

11. Damani Z, MacKean G, Bohm E, DeMone B, Wright B, Noseworthy T, et al. The use of a policy dialogue to facilitate evidence-informed policy development for improved access to care: the case of the Winnipeg central intake service (WCIS). Health Res Policy Syst. (2016) 14(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0149-5

12. Shaw J, Jamieson T, Agarwal P, Griffin B, Wong I, Bhatia RS. Virtual care policy recommendations for patient-centred primary care: findings of a consensus policy dialogue using a nominal group technique. J Telemed Telecare. (2018) 24(9):608–15. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17730444

13. Dovlo D, Monono ME, Elongo T, Nabyonga-Orem J. Health policy dialogue: experiences from Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. (2016) 16 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):214. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1447-x

14. Akhnif EH, Hachri H, Belmadani A, Mataria A, Bigdeli M. Policy dialogue and participation: a new way of crafting a national health financing strategy in Morocco. Health Res Policy Syst. (2020) 18(1):114. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00629-2

15. Bailly L, Jobert T, Petrovic M, Pradier C. Factors influencing participation in breast cancer screening in an urban setting. A study of organized and individual opportunistic screening among potentially active and retired women in the city of nice. Prev Med Rep. (2022) 31:102085. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.102085

16. Eisinger A, Senturia K. Doing community-driven research: a description of Seattle partners for healthy communities. J Urban Health. (2001) 78(3):519–34. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.519

17. Metzler MM, Higgins DL, Beeker CG, Freudenberg N, Lantz PM, Senturia KD, et al. Addressing urban health in detroit, New York City, and Seattle through community-based participatory research parterships. Am J Public Health. (2003) 93(5):803–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.5.803

18. Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Schulz AJ, McGranaghan RJ, Lichtensetin R, et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. (2010) 100(11):2094–102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506

19. Touboul P, Valbousquet J, Pourrat-Vanoni I, Alquier MF, Benchimol D, Pradier C. Comment adapter l'environnement pour favoriser la marche des seniors? Une étude qualitative [adapting the environment to encourage the elderly to walk: a qualitative study]. Sante Publique. (2011) 23(5):385–99. French. doi: 10.3917/spub.115.0385

20. Bailly L, d’Arripe-Longueville F, Fabre R, Emile M, Valbousquet J, Ferré N, et al. Impact of improved urban environment and coaching on physical condition and quality of life in elderly women: a controlled study. Eur J Public Health. (2019) 29(3): 588–93. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky192

21. Brookman-Frazee L, Stahmer AC, Lewis K, Feder JD, Reed S. Building a research-community collaborative to improve community care for infants and toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders. J Community Psychol. (2012) 40(6):715–34. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21501

22. Bors P, Dessauer M, Bell R, Wilkerson R, Lee J, Strunk SL. The active living by design national program: community initiatives and lessons learned. Am J Prev Med. (2009) 37(6):S313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.027

23. Mccreedy M, Leslie JG. Get active Orlando: changing the built environment to increase physical activity. Am J Prev Med. (2009) 37(6):S395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.013

24. Van Holle V, Van Cauwenberg J, Van Dyck D, Deforche B, Van de Weghe N, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Relationship between neighborhood walkability and older adults’ physical activity: results from the Belgian environmental physical activity study in seniors (BEPAS seniors). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2014) 11(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12966-014-0110-3

25. Cerin E, Sit CH, Barnett A, Johnston JM, Cheung M-C, Chan W-M. Ageing in an ultra-dense metropolis: perceived neighborhood characteristics and utilitarian walking in Hong Kong elders. Public Health Nutr. (2014) 17(1):225–32. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003862

26. Kerr C. Education for management in the new public health. J Health Adm Educ. (1991) 9(2):147–61.10114550

Keywords: policy dialogue, multi-sectoral collaboration, community-Based participatory research, health promotion, knowledge sharing

Citation: Pradier C, Balinska MA and Bailly L (2023) Enhancing multi-sectoral collaboration in health: the open arena for public health as a model for bridging the knowledge-translation gap. Front. Health Serv. 3:1216234. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2023.1216234

Received: 3 May 2023; Accepted: 6 September 2023;

Published: 18 September 2023.

Edited by:

Susan S. Garfield, ey US, United StatesReviewed by:

Christine Hildreth, Ernst and Young, United StatesYele Aluko, Ernst and Young, United States

© 2023 Pradier, Balinska and Bailly. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marta A. Balinska UGVyb3V0a2EubUBjaHUtbmljZS5mcg==

Christian Pradier

Christian Pradier Marta A. Balinska

Marta A. Balinska Laurent Bailly1,2

Laurent Bailly1,2