94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Health Serv. , 27 February 2023

Sec. Mental Health Services

Volume 3 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2023.1072248

This article is part of the Research Topic World Mental Health Day 2022: Key Drivers of Risk to Mental Health Services and Innovative Solutions View all 16 articles

Introduction: Police officers work in a variable environment under different circumstances and often involves stressful situations. This include working irregular hours, ongoing exposure to critical incidents, confrontations and violence. community police officers are mainly out in the society and have daily contact with the general public. critical incidents can also consist of being criticized and stigmatized as a police officer, both from the public but also lack of support from their own organization. There is evidence on negative impacts of stress on police officers. However, knowledge about the nature of police stress and its various types is insufficient. It is assumed that there are common stress factors which are universal among all police officers in different contexts but there is a lack of comparative studies to provide empirical evidence. The aim of this study is to compare different types of stress among police officers in Norway and Sweden and how the pattern of experiencing stress has changed over time in these countries.

Methods: The study population consisted of patrolling police officers from 20 local police districts or units in all seven regions in Sweden (n = 953) and patrolling police officers from four police districts in Norway (n = 678). A 42-item Police Stress Identification Questionnaire was used to measure the stress level.

Results: The findings show differences in types of stressful events as well as its severity among police officers in Sweden and Norway. The level of stress decreased over time among Swedish police officers whereas it showed no change or even an increase among the Norwegian participants.

Discussion: The results of this study are relevant for policy-makers, police authorities and lay police officers in each country to tailor their efforts to prevent stress among police officers.

Police officers are exposed to emotionally demanding situations, which come with the job. These situations include not only being confronted with death and illness and dealing with crime and accident victims but also interacting with perpetrators and disturbing persons and being exposed to various types of threats (1, 2). Police work includes regular and ongoing exposure to confrontation, violence, and, at its most extreme, potential harm to the officer's life (3). Many of these situations involve vulnerable people who are expected to receive support from the police (4). Therefore, police officers are continuously exposed to critical incidents as a part of their daily work. However, these critical incidents can also involve being criticized and stigmatized by the public and receiving little support from their own organization (5). For example, in a study on citizens' decisions to complain about the police, McLean (6) showed that the likelihood of complaining increases when the citizen perceives the interaction as procedurally and distributively unfair and when the outcome is unfavorable. In addition, police officers often work irregular hours, a factor that has been seen to negatively affect their health (e.g., an increased risk of cardiovascular disease) (7).

In summary, the complexity of demanding work-related situations and the factors described above have been shown to affect the stress levels of police officers (8–10). Although many investigations in police research have indicated the role of stress in police work, little is known about the various types of police stress. Without a comparative approach, it is difficult to determine whether there are some types of stress that are common among all police officers. In this comparative study, we aim to contribute to police stress research, identify specific types of police stress in Sweden and Norway, and assess the severity of these stress factors in both countries. We argue that this issue is highly relevant to police work and the profession because the identification of specific stress factors in police work creates the opportunity to develop resilience programs aimed at preventing long-term negative psychiatric, psychological, and social consequences for police officers. Moreover, the identification of police stress contributes to self-awareness among police officers and to police education by supporting the development of theoretical and practical modules to prepare police trainees for future police work. Researchers have reported the long-term effects of stress on police officers, which include maladaptive and antisocial behaviors, such as problem drinking, hyper-aggressiveness, and violence in work and private life (11, 12).

The current study compares Norway and Sweden because of the many similarities in their criminal justice systems (13); for example, the police are unified and state-organized, and each country is divided into police districts with a considerable degree of independence (13). However, there also exist several differences, including those in the way they organize prosecution, the number of police per resident, and the regulations concerning force resources (e.g., pepper spray and firearms). Furthermore, police work is carried out differently in Sweden and Norway. Norwegian police do not carry firearms unless the situation is expected to merit it (14), this is derived from that the police adopt a philosophy of policing by consent rather than policing with the threat of force.

Stress is defined as human psychological and physiological adaptation to the environment (15). Coping is defined as a cognitive resource for managing stressful internal and external situations (16). The coping theory introduced by Folkman and Lazarus contributes to increasing our understanding of the relationship between human cognition and the environment through primary and secondary appraisals. In their early studies on coping, Folkman and Lazarus suggested two coping mechanisms: problem-focused and emotion-focused coping. Later, two other main mechanisms of coping, namely, meaning-focused and support-seeking coping, were presented (16). Adding John Violanti's research on police stress from the early 1990 s until now and the long-term consequences of exposure to massive stress creates an opportunity to comprehensively study the stressful work environment of police (16–22). In this article we use coping theory as our point of departure. Police work requires mental preparation before acting or managing complex threatful situations. Given that Coping theory is based on individual's appraisal, it would contribute in understanding how police officers recognize the source of stress and how they organize their policing based on their judgment of the stressful event. Stress in police work.

Many studies support the notion that police work is highly stressful (9, 23–26) and that police officers experience high levels of work-related stress relative to many other occupations (27). For example, working with traumatized victims and conducting homicide inquiries are stressors in the area of criminal investigation (28–30). Police work also involves shift work, traumatic events, staff shortages, and bureaucratic burden, all of which are considered stressful. Lucas and colleagues (31) found that killing in the line of duty, inadequate supervisor support, departmental politics, and insufficient personnel are work stressors that are rated as especially stressful; meanwhile, assignment to nonpolicing duties, demand for high morality, promotion, and boredom are not rated as especially stressful. Job dissatisfaction, workplace discrimination, lack of cooperation among coworkers, and exposure to critical incidents are associated with perceived work stress (32). Additionally, studies have addressed different stress patterns among female and male police officers (33, 34). Some studies have explored the relationship between police officers' strategies to cope with stress and police culture (10) while other studies have focused on individual factors, such as age and gender, in relation to police officers' coping strategies (35). Gershon and colleagues (32) found that avoidant or negative coping is associated with higher levels of perceived work stress and adverse health outcomes.

The present study focused on the comparison of stress levels between police officers in Sweden and Norway and the temporal changes over time.

This study comprises police officers from two neighboring Scandinavian countries, namely, Sweden and Norway.

The Swedish police is a national authority with seven geographical police regions comprising 100 local police districts. In 2018, approximately 30% of 20,040 police officers were women, and the average age of all officers was 44 years. The Swedish Police Authority is led by the National Police Commissioner.

The Norwegian police is a national authority consisting of 12 police districts and is mainly responsible for police operations within a geographical area. There are approximately 10,000 police officers, approximately 30% of whom are women.

Data originated from three investigations: the Mareld study (36) in Sweden and two studies aimed at evaluating conducted energy weapons (CEWs) in Sweden and Norway. A Conducted Energy Weapon (CEW) is a device that delivers low amperage electrical current into its target, temporarily impacting the sensory and motor nervous system. When properly deployed, a CEW can disable an assailant with limited risk of long term or substantial injury. Response rate was 52% in the Swedish sample and 56% in the Norwegian sample. The authors were assigned by the Stockholm Police Region to conduct a scientific investigation (Mareld) with a focus on the health and working conditions among police officers working in so-called vulnerable areas in Stockholm, a term applied by the Swedish Police to areas with high crime rates and social exclusion. The data were collected from 2017 to 2020. In addition, the authors evaluated the test periods on CEWs of the Swedish and Norwegian police forces. The Swedish test period was between 2018 and 2019, and the Norwegian test period was between 2019 and 2020. In all three investigations, data were collected annually in three phases.

All police officers present at work were eligible to take part in the study. Participation was voluntary and no incentive was given to participants. The entire sample consisted of patrolling police officers from 20 local police districts or units in all seven regions of Sweden (n = 954) and patrolling police officers from 4 police districts in Norway (n = 677).

The researchers visited three local police districts in the Stockholm Police Region in spring 2018 and spring 2019 and personally informed them about the project and ethical issues to obtain informed consent. The project was described in a letter and a paper survey was distributed. The third data collection in spring 2020 was modified because of the COVID-19 pandemic; specifically, one appointed police officer in every three local police districts distributed and collected the paper survey and then sent it to us by mail. The project was described in an information letter provided to the respondents.

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Umeå University (Dnr 2017/516-31). This project was funded by the Stockholm Police Region.

The surveys and prepaid return envelopes were sent in a sealed envelope to the contact persons at each local police district or unit for distribution to police officers who could respond to the survey and return it using the prepaid return envelopes in December 2017. The project was presented to the researchers' contacts in the police authority through written and verbal descriptions. A reminder was conveyed to the contact persons through e-mail and communicated further to the police officers. This convenience sample was used because of confidentiality rules in the Swedish police organization. In November 2018 and November 2019, a link to the web survey and an information letter were distributed through e-mail to the police officers involved in the study by the contact person within the police authority. Two reminders were sent to police officers by e-mail.

This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2019-02464). This project was funded by the Swedish Police Authority.

The dataset was based on a survey conducted among all police officers who participated in the CEW evaluation. The survey and an information letter describing the project were distributed by the National Police Directorate through e-mail and made available to all participating officers in the evaluation of CEWs. Two reminders were sent to the police officers by e-mail. Once the data were collected, they were handed over to the research team after being anonymized.

A 42-item Police Stress Identification Questionnaire (11) was used to measure stress levels with the following instruction: “These questions map different types of stressors that affect you as a police officer or civil servant. Mark with a cross how strong you experienced the stress. It can be both that you experienced the event or that you experienced the risk of it happening as stressful.” A numerical rating from 0 to 9 was applied, with 9 indicating the most stressful level. A previous study has reported the validity and reliability of the instrument (11). Reliability of the questionnaire was checked with internal consistency assessment methods. Consistency of the entire scale was assessed using the Cronbach's alpha coefficient which was 0.95.

To ascertain face validity, we interviewed nine police officers focusing on items provided to them and discussed them, given their personal experiences that may lead to generating new items (11). The interviewees, aged 30–60 years, had on average more than 10 years of experience in the field. They were informed about the study's aim. Each interview took approximately 30 min. The content of interviews was discussed in our authorship group using content analysis and our theoretical perspectives. Phrases identified from the content analysis were discussed in the expert panel, including one expert in the field of stress and coping and an experienced police officer, and provided the basis for modifying or rewording the items and generating new items that were not included in the preliminary list. Interview data were used to confirm concepts in the existing literature about police stress and explore new areas. The results from confirmatory factor analysis showed the highest fit for data, suggesting construct validity of the PSIQ (11).

A random-effects ordered logistic model was adopted to analyze the data. Ordered logistic models were used to compare stress levels between police officers in Sweden and Norway as well as the temporal changes over the study period. We assessed (1) whether there is a difference between Sweden and Norway; (2) any changes in the mean score of stress items over time (three time points); and (3) the interactions between country and time point, that is, whether or not the change over time differs between Sweden and Norway. This method is designed to estimate models in the presence of a variable number of waves for each individual (37). Some individuals participated once, twice, and all three times. In this structure, repeated observations (panels) are nested within individual observations. We chose an optimal statistical method that accounts for the correlation between within-person measures repeated over time. We also estimated the predicted means in the form of average marginal effects (38) of the stress items at each measurement point for each country.

All estimations were performed using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

A total of 1,631 police officers (677 from Norway and 954 from Sweden) participated in this study (73% of them were male). Their baseline ages ranged from 22 to 66 years (mean age = 35 years; SD = 8 years).

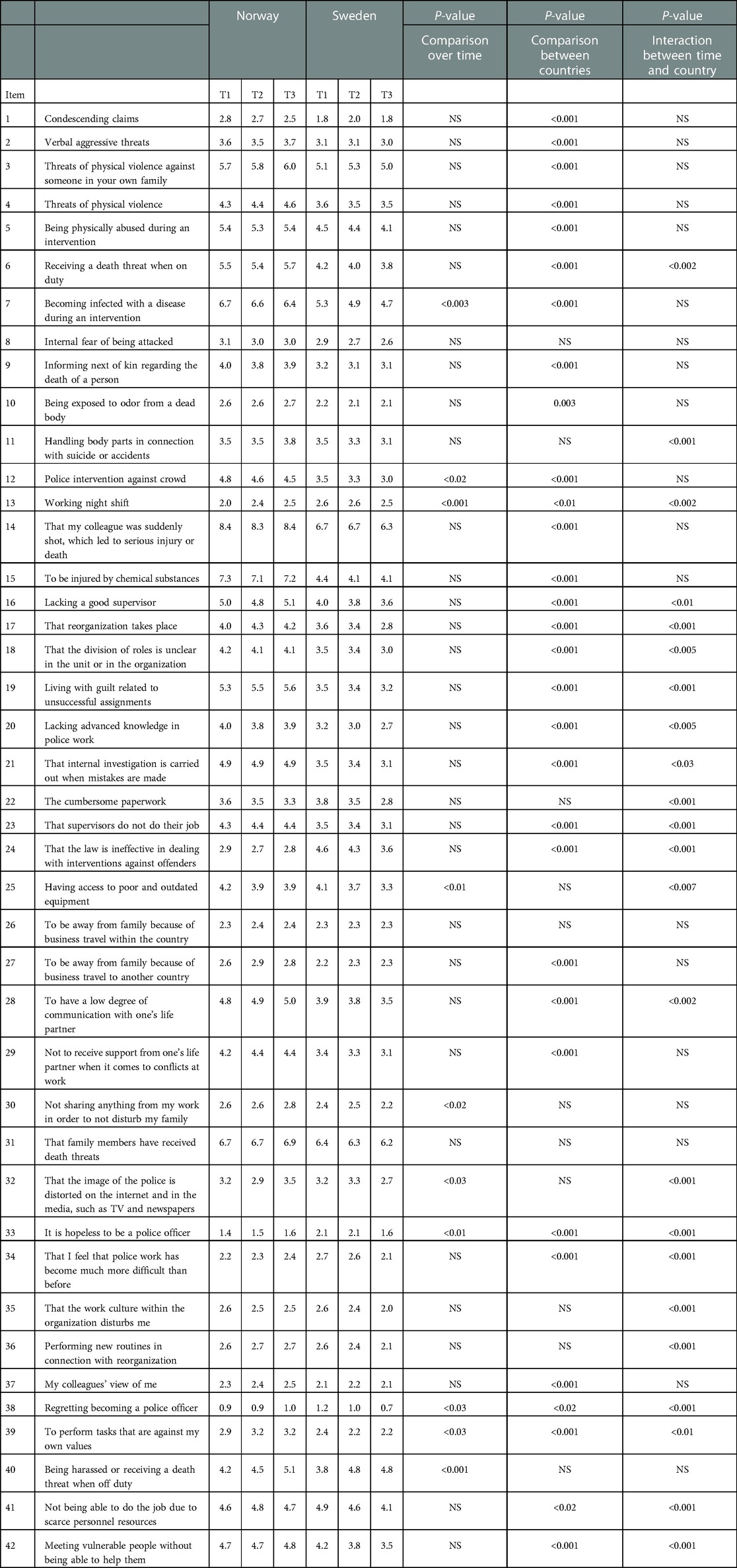

Figure 1 shows the mean scores for the stress items among the Swedish and Norwegian police officers. The police officers in both countries identified “That my colleague was suddenly shot, which led to serious injury or death” as the most stressful factor, followed by “That family members have received death threats.” Both countries identified “Regretting becoming a police officer” as the least stressful factor.

The mean score for the majority of the items (26 out of 42 items) was significantly higher among Norwegian police officers, suggesting that they experience a higher level of stress than their Swedish counterparts. Only five items were scored higher among Swedish police officers. These items are as follows:

P13. Working night shift

P24. That the law is ineffective in dealing with interventions against offenders

P33. It is hopeless to be a police officer

P34. That I feel that police work has become much more difficult than before

P38. Regretting becoming a police officer

Table 1 presents the mean scores of the 42 stress items among police officers in Sweden and Norway.

Table 1. Mean scores for the stress items among police officers in Sweden and Norway at three measurement points.

We found an interaction between time and country for 23 items, suggesting that Sweden and Norway showed different patterns regarding changes in stress levels over time. These interactions can be classified into the following four patterns. There were 15 items that belonged to Pattern 1, 6 items to Pattern 2 and one item in each pattern 3 and 4.

There were 15 items that showed no difference over time in Norway but decreased in Sweden. (Figure 2).

6. Receiving a death threat when on duty

16. Lacking a good supervisor

18. That the division of roles is unclear in the unit or in the organization

20. Lacking advanced knowledge in police work

21. That internal investigation is carried out when mistakes are made

22. The cumbersome paperwork

23. That supervisors do not do their job

24. That the law is ineffective in dealing with interventions against offenders

28. To have a low degree of communication with one's life partner

34. That I feel that police work has become much more difficult than before

35. That the work culture within the organization disturbs me

36. Performing new routines in connection with reorganization

38. Regretting becoming a police officer

41. Not being able to do the job due to scarce personnel resources

42. Meeting vulnerable people without being able to help them

We found 6 items that in average increased over time in Norway but showed a decreasing trend over time in Sweden (Figure 3).

11. Handling body parts in connection with suicide or accidents

17. That reorganization takes place

19. Living with guilt related to unsuccessful assignments

32. That the image of the police is distorted on the internet and in the media, such as TV and newspapers

33. It is hopeless to be a police officer

39. To perform tasks that are against my own values

There was one item for which the mean value decreased over time in both countries (Figure 4).

25. Having access to poor and outdated equipment

There was one item with an increasing trend over time in Norway but no change in Sweden (Figure 5).

13. Working night shift

The aim of this study is to compare different types of stress among police officers in Norway and Sweden and investigate how the pattern of experiencing stress has changed over time in these countries. Both countries are highly developed and are economically comparable, but they hold significant disparities in terms of societal problems and population dynamics. Prior research tends to consider police work in northern countries in a similar manner. Researchers have also emphasized the extent to which the police in Nordic countries are renowned for emphasizing “soft policing” based on notions of prevention, social inclusion and an equal relationship between members of the civil society and the police (39). In general, Nordic police are endowed with a high level of public trust, and the general public perception is that discrimination and differential treatment rarely exist (13, 40, 41). We provided empirical evidence of potential differences in police work between the two countries that demand specific attention from their respective authorities. We found that Norwegian police officers experienced low stress (score of 1–3.9) for 21 items, such as “Regretting becoming a police officer” and “Working night shift”; medium stress (score of 4–6.9) for 19 items, such as “Having access to poor and outdated equipment “ and “Threats of physical violence”; and high stress (score of 7–9) for 2 items, namely, “To be injured by chemical substances” and “That my colleague was suddenly shot, which led to serious injury or death.” Contrary to Norway police, Swedish police had 32 items under the low stress category (e.g., “Regretting becoming a police officer”), 10 items in the medium level category (e.g., “Receiving a death threat when on duty”), and no item in the high level stress category. On average, Norwegian police officers reported higher levels of stress than their Swedish counterparts. Burke and Mikkelsen (42) reported that Norwegian police officers experience high levels of cynicism because of job stress and burnout. Findings from a nationwide survey of 3,272 Norwegian police personnel exploring the association between job stress and physical and mental health showed that frequent exposure to work stress is associated with health problems (43). The results showed that Norwegian police have high levels of musculoskeletal health problems, which are mainly associated with the frequency of job pressure and lack of support. The report concluded that daily routine work, as well as police operational duties, must be considered when assessing job stress and police health. There is a lack of national surveys among Swedish police regarding job stress, but a number of investigations have reported experienced job demand and police stress as a source of poor mental health (11, 23). Further investigation is needed to determine whether differences in aspects such as police organizational settings in the two countries are associated with higher levels of stress among Norwegian police officers.

Another explanation could be the fact that Norwegian police officers do not carry service weapons in their belts; they store their service weapons in the patrol car and equip them when necessary. This might explain why Norwegian police officers reported significantly higher stress on items 4–6, 12, and 14 (threat and violence on duty) compared with Swedish police officers when there are no significant differences for item 40 (threat of violence off duty). In other words, there is a difference in stress when the officers are on duty, with only Swedish police being armed, but there are no differences when they are off duty and unarmed. Meanwhile, there is no difference between the countries in terms of item 25, which is related to poor or outdated equipment. This needs to be investigated further as the issue of armed or unarmed police involves more perspectives than officers' perceptions of stress. Finally, the long-term effects of being armed on police officers need to be considered at individual and societal levels.

The findings of this study show a decreasing trend over time for most of the items among Swedish police officers. By contrast, the findings reveal no change or even increase over time for some items among the Norwegian participants. A possible explanation for this could be related to the Swedish police reorganization into one national authority in 2015. The first data collection was conducted three years after the reorganization, and the last data collection was conducted five years after the reorganization. During the first few years after the transformation into the national police authority, many supervisors had to apply for new positions, and during this time, many supervisor positions were temporary, resulting in accountability being at risk or unclear. In addition, many previously well-functioning units were reorganized, possibly causing distress among the personnel. The organization might have stabilized five years after the reorganization. Some studies have reviewed police reforms. For example, Mendel and colleagues (44) found relatively strong evidence for a range of risks involved in police mergers, such as the risk of loss of skills and competence, risk of disruption to employer–employee relationships, and risk of problems being exacerbated by inadequate planning and management. In addition, the Swedish Agency for Public Management (Statskontoret), which is responsible for evaluating police reorganization, found that the new organization lacks management and communication (45).

Another explanation could be that during the study period, Swedish police authorities initiated several interventions with the goal of improving safety and security in society. In 2017, the Swedish government announced a broad political consensus that Sweden's internal and external security must be strengthened through public security and institutional protection (46). Given this mission, there is a need to enhance crime prevention efforts by practical and political actors and capacity building for police units as one of the main stakeholders in fighting crime.

Our investigation has several limitations. The sample comprised only patrolling police officers which limits the generalizability of the findings. Items were selected from a range of possibilities that are relevant to patrolling police officers whose tasks are unique and somehow different from other police employees. Including desk police officers would require a different set of items that specifically concerns the target group. Being a police officer is a complex and diverse profession, and it is impossible to capture all possible stressors in police work in one questionnaire. As the first step, we decided to focus on patrolling police officers, who deal with certain types of stressors and move forward to a broader range of police stressors in future research.

In future studies, it would be relevant to use multiple methods to develop quantitative and qualitative data (such as participant observations) to explain the differences in various types of stress between the two countries. There are several other important future research directions that this study did not cover. For example, it would be interesting to investigate how subjective experiences of stress are connected to societal forces and the kinds of interactions that take place between the public and the police.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because The data includes sensitive information and according the ethical approval we cannot share it with third party.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Umeå University (Dnr 2017/516-31) and Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2019-02464). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

MP, MG, JH and MI: conceptualized and designed the study. JH, JS, MG and MI: collected data for the study. MP: managed and analyzed the data. MG, JH and MI: acquired funding for this study. MP: prepared the figures and tables. JH, JS and MP: prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited, and commented on the final draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by Swedish Police Authority, Stockholm Police Region and Norwegian Police Directorate (Dnr 2019-02464 and 2017-516/31).

The authors thank the participants of the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Anderson GS, Litzenberger R, Plecas D. Physical evidence of police officer stress. Int J Police Strateg manag. (2002) 25(2):399–420. doi: 10.1108/13639510210429437

2. Karlsson I, Christianson SÅ. The phenomenology of traumatic experiences in police work. Int J Police Strateg manag. (2003) 26(3):419–38. doi: 10.1108/13639510310489476

3. Maguen S, Metzler TJ, McCaslin SE, Inslicht SS, Henn-Haase C, Neylan TC, et al. Routine work environment stress and PTSD symptoms in police officers. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2009) 197(10):754. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b975f8

4. Punch M, James S. Researching law enforcement and public health. Policing and Society. (2017) 27:251–60. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2016.1205066

5. Ménard KS, Arter ML. Police officer alcohol use and trauma symptoms: associations with critical incidents, coping, and social stressors. Int J Stress Manag. (2013) 20(1):37. doi: 10.1037/a0031434

6. McLean K. Justice-restoring responses: a theoretical framework for understanding citizen complaints against the police. Polic Soc. (2021) 31(2):209–28. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2019.1704755

7. Ma CC, Andrew ME, Fekedulegn D, Gu JK, Hartley TA, Charles LE, et al. Shift work and occupational stress in police officers. Saf Health Work. (2015) 6(1):25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2014.10.001

8. Russell LM. An empirical investigation of high-risk occupations: leader influence on employee stress and burnout among police. Manag Res Rev. (2014) 37(4):367–84. doi: 10.1108/MRR-10-2012-0227

9. Padyab M, Backteman-Erlanson S, Brulin C. Burnout, coping, stress of conscience and psychosocial work environment among patrolling police officers. J Police Crim Psychol. (2016) 31(4):229–37. doi: 10.1007/s11896-015-9189-y

10. Gutschmidt D, Vera A. Organizational culture, stress, and coping strategies in the police: an empirical investigation. Police Pract Res. (2022) 23(5):507–22. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2021.1958683

11. Ghazinour M, Padyab M, Hansson J. Police stress in the Swedish context: development and psychometric properties of the police stress identification questionnaire. Nordic J Stud Policing. 8(1):1–19. doi: 10.18261/issn.2703-7045-2021-01-05

12. Kohan A, O’Connor BP. Police officer job satisfaction in relation to mood, well-being, and alcohol consumption. J Psychol. (2002) 136(3):307–18. doi: 10.1080/00223980209604158

14. Henriksen SV, Kruke BI. The force Continuum: prevalence and characteristics of police use of coercive force. Nordic J Stud Policing. (2020) 7(1):5–22. doi: 10.18261/issn.2703-7045-2020-01-02

15. Jones A, Pruessner JC, McMillan MR, Jones RW, Kowalik GT, Steeden JA, et al. Physiological adaptations to chronic stress in healthy humans–why might the sexes have evolved different energy utilisation strategies? J Physiol. (2016) 594(15):4297–307. doi: 10.1113/JP272021

16. Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu Rev Psychol. (2004) 55(1):745–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456

17. Violanti JM. The police: perspectives on trauma and resiliency. Traumatology. (2006) 12:167–9. doi: 10.1177/1534765606296998

18. Violanti JM, Fekedulegn D, Hartley TA, Charles LE, Andrew ME, Ma CC, et al. Highly rated and most frequent stressors among police officers: gender differences. Am J Crim Justice. (2016) 41(4):645–62. doi: 10.1007/s12103-016-9342-x

19. Violanti JM, Aron F. Ranking police stressors. Psychol Rep. (1994) 75(2):824–6. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1994.75.2.824

20. Violanti JM. Shifts, extended work hours, and fatigue: An assessment of health and personal risks for police officers (2012). NIJ FINAL REPORT..

21. Violanti JM, Charles LE, McCanlies E, Hartley TA, Baughman P, Andrew ME, et al. Police stressors and health: a state-of-the-art review. Int J Police Strateg manag. (2017) 40(4): 642–56. doi: 10.1108/PIJPSM-06-2016-0097

22. Violanti JM, Fekedulegn D, Andrew ME, Hartley TA, Charles LE, Miller DB, et al. The impact of perceived intensity and frequency of police work occupational stressors on the cortisol awakening response (CAR): findings from the BCOPS study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2017) 75:124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.10.017

23. Backteman-Erlanson S, Padyab M, Brulin C. Prevalence of burnout and associations with psychosocial work environment, physical strain, and stress of conscience among Swedish female and male police personnel. Police Pract Res. (2013) 14(6):491–505. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2012.736719

24. Duxbury L, Halinski M. It’s not all about guns and gangs: role overload as a source of stress for male and female police officers. Polic Soc. (2018) 28(8):930–46. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2017.1342644

25. Griffin JD, Sun IY. Do work-family conflict and resiliency mediate police stress and burnout: a study of state police officers. Am J Crim Justice. (2018) 43(2):354–70. doi: 10.1007/s12103-017-9401-y

26. Sherwood L, Hegarty S, Vallières F, Hyland P, Murphy J, Fitzgerald G, et al. Identifying the key risk factors for adverse psychological outcomes among police officers: a systematic literature review. J Trauma Stress. (2019) 32(5):688–700. doi: 10.1002/jts.22431

27. Johnson S, Cooper C, Cartwright S, Donald I, Taylor P, Millet C. The experience of work-related stress across occupations. J Manag Psychol. (2005) 20(2):178–87. doi: 10.1108/02683940510579803

28. Roach J, Sharratt K, Cartwright A, Skou Roer T. Cognitive and emotional stressors of child homicide investigations on UK and Danish police investigators. Homicide Stud. (2018) 22(3):296–320. doi: 10.1177/1088767918759695

29. Cartwright A, Roach J. A price paid? A review of the research on the impact of investigating serious crime on the wellbeing of police staff. Police J. (2022) 95(1):109–26. doi: 10.1177/0032258X211049335

30. Foley J, Massey KLD. The “cost”of caring in policing: from burnout to PTSD in police officers in England and Wales. Police J. (2021) 94(3):298–315. doi: 10.1177/0032258X20917442

31. Lucas T, Weidner N, Janisse J. Where does work stress come from? A generalizability analysis of stress in police officers. Psychol Health. (2012) 27(12):1426–47. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2012.687738

32. Gershon RR, Barocas B, Canton AN, Li X, Vlahov D. Mental, physical, and behavioral outcomes associated with perceived work stress in police officers. Crim Justice Behav. (2009) 36(3):275–89. doi: 10.1177/0093854808330015

33. He N, Zhao J, Archbold CA. Gender and police stress: the convergent and divergent impact of work environment, work-family conflict, and stress coping mechanisms of female and male police officers. In: Natarajan M, Editor. Women police. London: Routledge (2005). p. 687–708.

34. Kurtz DL. Controlled burn: the gendering of stress and burnout in modern policing. Fem Criminol. (2008) 3(3):216–38. doi: 10.1177/1557085108321672

35. Acquadro Maran D, Varetto A, Zedda M, Ieraci V. Occupational stress, anxiety and coping strategies in police officers. Occup Med (Chic Ill). (2015) 65(6):466–73. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv060

36. Sundqvist J, Eriksson M, Ghazinour M, Hansson J, Hjertstedt M, Padyab M. Initiativ Mareld: en studie om polisanställdas hälsa, arbetsmiljö och trygghetsskapande arbete i särskilt utsatta områden i polisregion Stockholm (2021).

37. Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using stata: Categorical responses, counts, and survival. 3rd ed. Umeå: Stata Press (2012). Available at: http://books.google.se/books?id=KyKnpwAACAAJ.

38. Williams R. Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J. (2012) 12(2):308–31. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1201200209

39. Balvig F, Holmberg L, Sørensen AS. Ringstedforsøget: livsstil og forebyggelse i lokalsamfundet. 1. udgave, 1. oplag. København: Jurist- og Økonomforbundets Forl (2005). 454 p.

41. Kääriäinen J. Why do the Finns trust the police? J Scand Stud Criminol Crime Prev. (2008) 9(2):141–59. doi: 10.1080/14043850802450294

42. Burke RJ, Mikkelsen A. Burnout, job stress and attitudes towards the use of force by Norwegian police officers. Int J Police Strateg manag. (2005) 28(2):269–78. doi: 10.1108/13639510510597906

43. Berg AM, Hem E, Lau B, Ekeberg Ø. An exploration of job stress and health in the Norwegian police service: a cross sectional study. J Occup Med Toxicol. (2006) 1(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-1-26

44. Mendel J, Fyfe NR, den Heyer G. Does police size matter? A review of the evidence regarding restructuring police organisations. Police Pract Res. (2017) 18(1):3–14. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2015.1135399

45. Uppföljning av karriärstegsreformen. Delrapport 3. Statskontoret. . Available at: https://www.statskontoret.se/publicerat/publikationer/publikationer-2017/uppfoljning-av-karriarstegsreformen.-delrapport-3/ (cited 2022 Oct 14).

46. Regeringskansliet R och. Tillsammans mot brott - ett nationellt brottsförebyggande program [Internet]. Regeringskansliet. Regeringen och Regeringskansliet (2017). Available at: https://regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/skrivelse/2017/03/skr.-201617126/ (cited 2022 Mar 8).

Keywords: stress, police, comparative study, Sweden, Norway

Citation: Padyab M, Hansson J, Sundqvist J, Inzunza M and Ghazinour M (2023) A comparative study of stress experienced by Swedish and Norwegian police officers. Front. Health Serv. 3:1072248. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2023.1072248

Received: 17 October 2022; Accepted: 2 February 2023;

Published: 27 February 2023.

Edited by:

Gerard Leavey, Ulster University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sarah Butter, Ulster University, United Kingdom© 2023 Padyab, Hansson, Sundqvist, Inzunza and Ghazinour. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mojgan Padyab bW9qZ2FuLnBhZHlhYkB1bXUuc2U=

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Mental Health Services, a section of the journal Frontiers in Health Services

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.