- 1The Louis and Gabi Weisfeld School of Social Work, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel

- 2Endo Israel Community Association, Givatayim, Israel

- 3School of Social Work, Ariel University, Givatayim, Israel

Background: Endometriosis, impacting roughly 10% of reproductive-age women and girls globally, presents diagnostic challenges that can cause significant delays between symptom onset and medical confirmation. The aim of the current study was to explore the experience of women with endometriosis as well as that of their partners, from pre-diagnosis to diagnosis to post-diagnosis.

Methods: In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 couples coping with endometriosis. Each partner was interviewed separately, and each interview was analyzed both individually and as part of a dyad, using the dyadic interview analysis method.

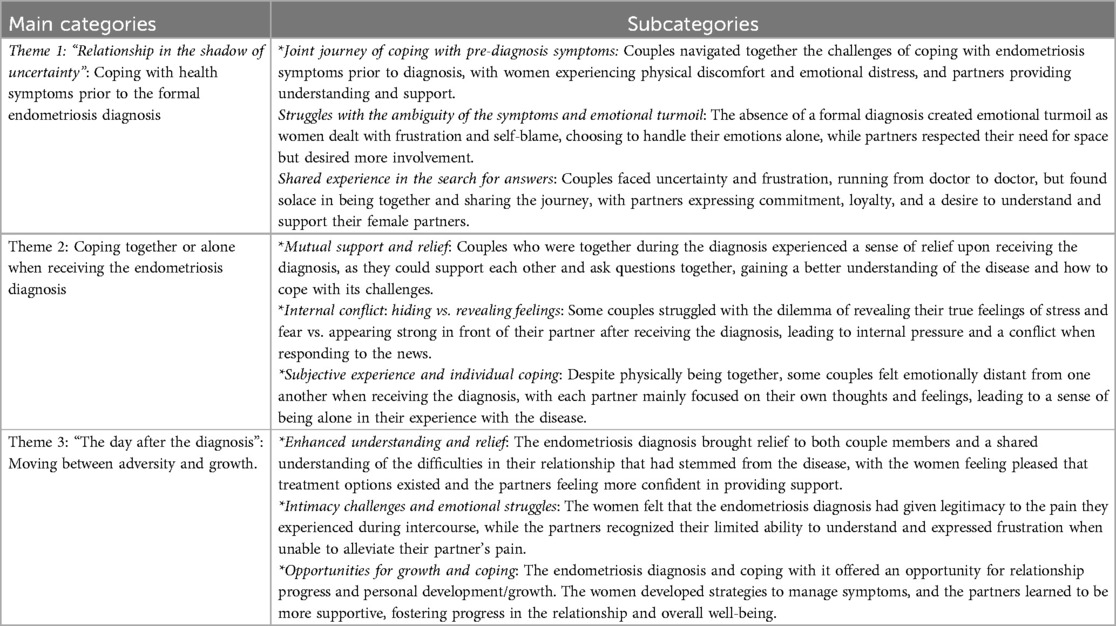

Results: Three main themes emerged: (i) “Relationship in the shadow of uncertainty”: Coping with health symptoms prior to the formal endometriosis diagnosis; (ii) Coping together or alone when receiving the endometriosis diagnosis; and (iii) “The day after the diagnosis”: Moving between adversity and growth.

Conclusions: The study's findings emphasize the importance of viewing the diagnosis from a dyadic perspective and comprehensively – that is, from pre-diagnosis to accepting the formal diagnosis to post-diagnosis. This journey can have a profound impact on both couple members, affecting their day-to-day functioning, communication, emotional and physical intimacy, and fertility.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a disease in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus (1). It affects roughly 10% (190 million) of reproductive-age women and girls globally and can cause infertility (2). According to the WHO (1), endometriosis symptoms include a combination of painful menstrual periods, chronic pelvic pain, pain during and/or after sexual intercourse, painful bowel movements, painful urination, fatigue, depression or anxiety, abdominal bloating, and nausea. Given the variability and broad symptoms involved, endometriosis is not easily diagnosed by healthcare workers, potentially causing a lengthy delay between symptom onset and diagnosis (3). Diagnosis can take seven years on average after symptom onset (4) but ranges from four to 11 years (5), suggesting a major impact on women's psychological well-being both before diagnosis and after (6). Indeed, a recent meta-ethnography in which the illness experience of endometriosis patients across the globe was investigated stressed the negative impact of this disease on many aspects of life (7). Specifically, the authors found that women with endometriosis encountered a multitude of problems including infertility, difficulty in maintaining intimate relationships (both emotional and physical) with their partners, psychological distress, negative emotions that could lead to suicidal ideation, low sense of self, low productivity at work, increased absenteeism, poor academic performance, social isolation, and low quality of life (7).

In Israel, the recognition and management of endometriosis have received growing attention at both policy and societal levels in recent years. The Israeli Ministry of Health has launched several initiatives aimed at raising awareness and improving the diagnosis of endometriosis through public health campaigns, with a focus on early detection and patient education (8). In this context, Wertheimer and colleagues (9) found that the average delay in diagnosing endometriosis in Israel is 11.2 years, which can be divided into two phases. The first phase involves an average delay of 4.6 years from the onset of symptoms to the point of reporting them to a medical professional, while the second phase includes an average delay of 6.6 years from the initial reporting to receiving a formal diagnosis. Their study also revealed that younger women experienced shorter diagnostic delays. Notably, only about 42% of the women reported that a medical professional was the first to raise the suspicion of endometriosis. The remaining women became aware of the possibility of endometriosis through media exposure, the activities of associations, independent online research, or conversations with acquaintances (9). Today, endometriosis is included in the basket of health services provided under national health insurance, offering more comprehensive and accessible treatment options for affected women (10).

In addition to endometriosis's impact on the woman's life, it also has an impact on the woman's partner's life. The negative emotions that have been reported among patients' partners include depression, anxiety, helplessness, frustration, worry, and anger (11–13). Additionally, partners of women with endometriosis have reported negative effects on their sex life (i.e., lack of communication about sexuality, sexual dysfunction, avoidance of sexual intercourse), intimacy, and the couple's relationship (14, 15).

Moreover, as endometriosis is a shared experience within the couple (16), several researchers have explored dyadic relations and marital satisfaction in the context of endometriosis (15–18). For example, Facchin and colleagues (17) revealed that women who perceived their partner as being more interested and actively involved in the management of their endometriosis (for instance by accompanying them to medical visits) reported greater relational satisfaction and better dyadic coping.

Considering the impact of endometriosis on both spouses, it is important to recognize that Israel's cultural landscape is heavily shaped by traditional values and societal expectations surrounding marriage, family, and procreation (19). There is a particularly strong emphasis on family life and childbearing, with significant social pressure on couples to have children soon after marriage (20). This cultural expectation often intensifies the emotional and psychological distress experienced by women diagnosed with endometriosis, who may already be struggling with issues related to infertility and intimacy (21). Partners may also feel an increased sense of responsibility to support their spouses, reflecting cultural notions of marital solidarity and traditional gender roles (13).

Taken together, it seems clear that endometriosis is a physically and mentally debilitating disease, with high emotional costs for both patients and partners (18). However, less is known about patients' and partners' pre-diagnosis experience, and whether the pre-diagnosis period impacts the acceptance of the diagnosis as well as the post–diagnosis period. Based on the Biopsychosocial Model (22), which emphasizes the complex interactions between biological, psychological, and social factors in understanding health and illness, we aimed to explore the experience of patients and their partners throughout their endometriosis “journey”—from pre-diagnosis, to receiving the diagnosis, to post-diagnosis management. By adopting this model, our study acknowledges that the experience of endometriosis extends beyond physical symptoms, impacting intimate relationships, self-identity, and social participation (23). Gaining a deeper understanding of the experiences of both couple members will provide professionals in the field with knowledge regarding the design of suitable interventions addressing both patients' and partners' needs.

Method

In this study we used a qualitative-phenomenological approach (24), exploring participants' experiences with endometriosis so as to understand the phenomenon. This approach allows researchers to gain a rich understanding of the interviewees and uncover meaningful insights about the complex phenomenon under study (25). By focusing on participants’ lived experiences, phenomenological inquiry seeks to capture the essence of how individuals perceive and make sense of their condition, providing depth and context to their emotional and relational responses (25).

Sample

Purposive sampling (26) was used, and the inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) having received a diagnosis of endometriosis at least nine months prior to the study, (2) being aged 18 and above, and (3) being in a heterosexual cohabiting relationship for at least one year. Given the dyadic nature of the study, both partners were asked for consent to participate.

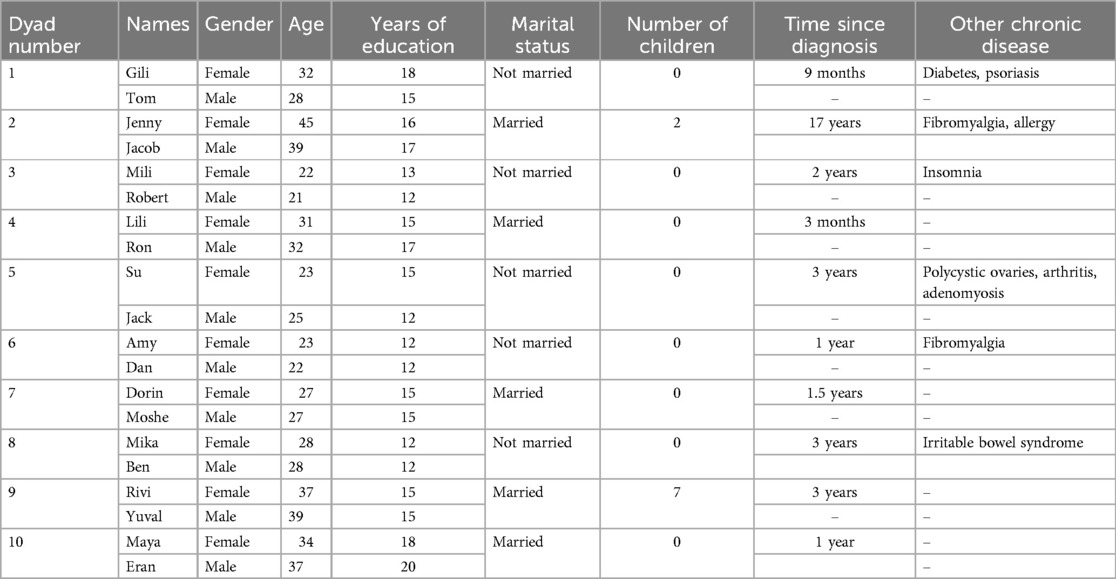

The sample included 10 dyads (20 participants) aged 21–45 (men aged 21–39; women aged 22–45). Five couples were married, and two of them also had children. Years of education for all participants ranged between 12 and 20. Time elapsed since the endometriosis diagnosis ranged from 9 months to 17 years. Three couples were in a cohabiting relationship only post-diagnosis (for more details see Table 1).

Procedure

After obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee (Authorization No. 072202), participants were recruited from August to October 2022 through the Endo Israel Community Association, which advertised the study on its Facebook and Instagram pages. Because the data was collected via social networks, we could not assess the response rate.

The interviews were conducted by five female interviewers, four of whom had themselves been diagnosed with endometriosis and who served as members of the Endo Israel Community Association (the first author was the fifth interviewer). All interviewers had prior training in qualitative interviewing including the conducting of mock interviews prior to the start of this study. To ensure consistency across interviews, an ongoing supervision and mentoring regarding interviewing style were provided by S.S.A., a social worker with extensive experience in qualitative research. Debriefing sessions were held throughout the data collection period to ensure alignment in interview techniques and adherence to the research objectives.

The interviewers contacted each patient and partner by phone to explain the study's aims and procedure. Once both partners agreed to participate, the interviewers scheduled a separate interview with each one. The same interviewer interviewed both members of each couple. For ethical reasons, each participant received information regarding the purpose of the study and signed a letter of consent that included an explanation stating that data would be used for research purposes only and that confidentiality would be preserved by changing identifying details. Participants were informed they could withdraw from the study at any time and could refuse to answer any question. None of the participants dropped out. No incentives were offered. Each interview was conducted via Zoom and lasted 60–90 min. Each partner was interviewed separately, and each interview was analyzed individually and as part of a dyad. Notably, to address the ethical complexities of dyadic research, we followed recommendations from the literature (27) to ensure confidentiality. We anonymized sensitive information and informed participants that the analysis would prevent partners from identifying each other's disclosures.

The interviews were conducted in Hebrew, recorded, and then translated into English. Each translation was reviewed by two native speakers, including a professional translator. Data collection continued until theoretical saturation was achieved, meaning that additional interviews no longer produced new material for analysis (17).

Research tools and instruments

The study's qualitative data were collected through in-depth semi-structured interviews (28). The research team opted for interviews as the primary method to explore and understand participants' experiences (see Appendices 1, 2). The interviews followed a flexible guide that included significant key areas to facilitate a dialogue between the interviewer and the interviewee and enable meaningful self-expression (25). We developed the interview guide based on a phenomenological framework, designed to explore participants' lived experiences of endometriosis and its impact on their relationships. The guide included open-ended questions aimed at facilitating an in-depth exploration of emotional, physical, and relational aspects of coping with the disease.

Data analysis

The dyadic interview analysis method (29) was used to analyze the data. This method involves following the initial steps of thematic analysis, such as reading and re-reading the interviews, making notes, and coding the data to identify units of meaning and their corresponding titles. This process was repeated for each partner's interview, and all 20 interviews were analyzed. The analysis focused on the endometriosis diagnosis journey, resulting in three themes. The analysis, conducted by S.S.A., was conducted on both individual and dyadic levels to examine the data from different perspectives (30).

At the individual level, each partner's quotes were analyzed in an in-depth fashion, with content, structure, linguistics, grammar, and metaphors being taken into consideration (31). This process involves deriving interpretations directly from the data. The same analysis was conducted for quotes from the other partner. At the dyadic level, the focus was on examining the contrasts and overlaps between the partners' quotes. Doing so involved exploring the text and subtext, as well as the partners’ descriptions and interpretations within each theme and sub-theme (29). The themes were identified on the basis of the content and structure of the quotes specifically related to the endometriosis diagnosis.

To ensure the trustworthiness of the study findings, the researchers employed multiple methods. These included conducting in-depth interviews for a comprehensive understanding of participants' experiences, verbatim transcription of interview data, and adhering to credibility criteria (i.e., presenting data in a dense and detailed manner). Triangulation through the use of two different sources of interviews and dyadic analysis further enhanced the trustworthiness of the data (32).

Results

This section presents three key themes from interviews with women diagnosed with endometriosis and their partners. These themes explore the emotional, physical, and relational challenges experienced across the pre-diagnosis, diagnosis, and post-diagnosis stages, highlighting the impact of endometriosis on both individuals and their relationships.

Theme 1: “Relationship in the shadow of uncertainty”: coping with health symptoms prior to the formal endometriosis diagnosis

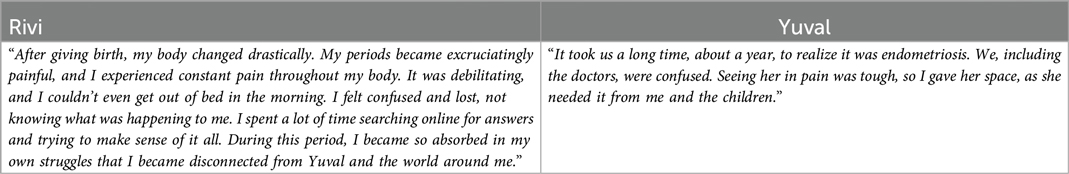

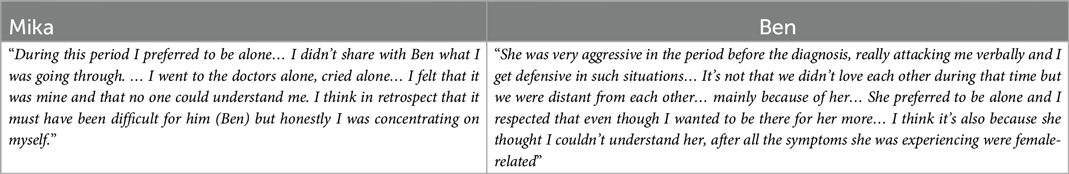

The couples talked about a joint coping journey that started pre-diagnosis. This period was marked by an arduous quest for answers, as the disease's symptoms were taking a severe toll on the women's physical and emotional well-being. All of the women talked about the physical discomfort they had experienced in various regions of their bodies, to the extent that it hindered their daily functioning. Furthermore, the women, along with their partners, expressed a great deal of unease over the ambiguity and meaning of these symptoms. During this difficult period, the women in four couples began to distance themselves from their partners. The partners responded with understanding, recognizing the women's need for space and time to process their emotions. Despite the temporary distance between them, the partners remained committed to supporting each other (Boxes 1, 2).

The individual coping within the dyad during the pre-diagnosis period was reflected in five of the women preferring to handle their emotions and cope with the situation alone, rather than burdening their partners: They often chose to undergo medical tests on their own and refrained from sharing their emotional struggles with their significant others. Five male partners discussed the dilemma regarding the emotional distance that was created between them as a result: They expressed their wish to support their female partners and be part of the process but also acknowledged their partners’ need for space. Despite the emotional difficulty and their limited understanding of the situation, given the female nature of the as-yet undiagnosed disease, five partners emphasized that they would have preferred to be involved in the process.

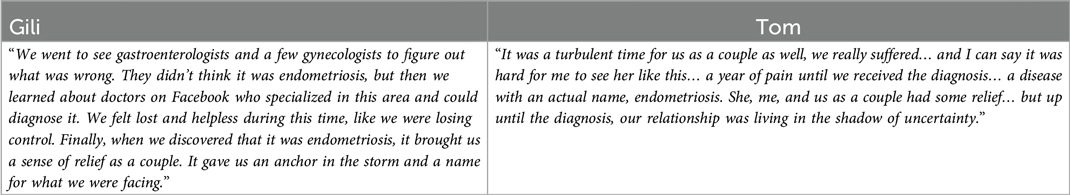

The “we” of the experience even in the pre-diagnosis phase was expressed among five dyads who described that due to how significantly the disease was impacting the women's functioning, the couple together tried to find a name for it (i.e., a diagnosis), on the basis of the women's physical and emotional symptoms. One of the most prominent features during this period was running from doctor to doctor together, a feeling of uncertainty, and a lack of control in the face of various proposed diagnoses, some of which in retrospect were wrong and only led to more frustration. The couples described a common experience around the search for a diagnosis; both the women and their partners described a shared marital experience (Box 3).

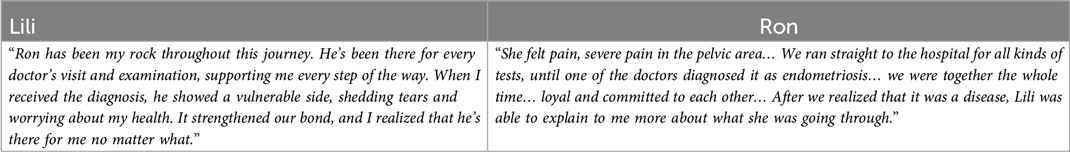

Lili and Ron (Box 4) also described a joint couple experience on the way to receiving a diagnosis. Their shared experience could be described as “we're in it together for better and worse.” Their relationship experience during this period of uncertainty was enveloped in mutual loyalty and commitment.

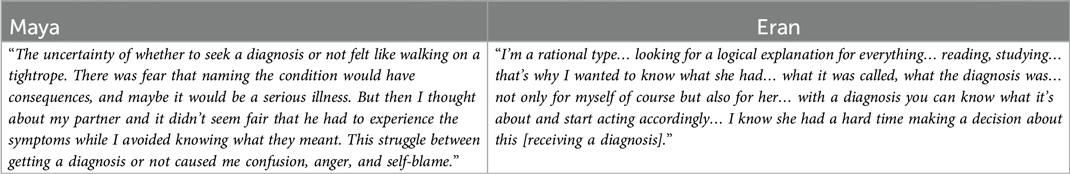

Before receiving the diagnosis, six women experienced internal conflict. They wanted to understand whether there was a name for their physical symptoms and whether it was recognized in the medical literature. They felt frustrated and confused that their symptoms did not seem to be taken seriously by healthcare providers or society. However, they also feared the potential consequences of receiving a diagnosis and worried about how it might impact their lives. This inner turmoil caused them to feel guilty for not facing the situation and not allowing their partners to be more involved. The partners, on the other hand, were simply “hungry” for information; they wished to fully comprehend their partner's health status, educating themselves about the disease they were facing (Box 5).

Theme 2: Coping together or alone when receiving the endometriosis diagnosis

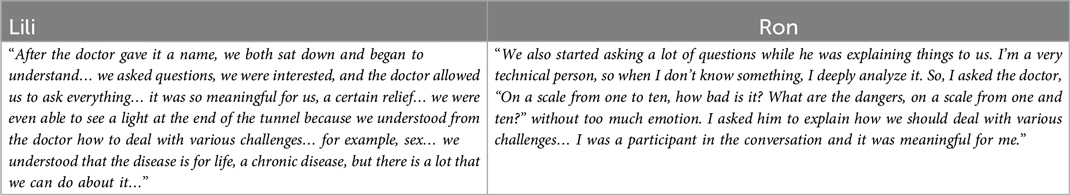

This theme pertains to the experience of receiving an endometriosis diagnosis after a prolonged period of waiting. Six women were with their partners when they received the diagnosis, and four women were not in a relationship at the time of the diagnosis. Therefore, the latter group of women had to break the news about the disease to their partners (i.e., when they entered these relationships). The couples who were together described a common experience of relief upon receiving the diagnosis and the mutual support made possible by the partner's presence (i.e., he too could hear what the doctor had to say about the disease). Even though endometriosis is a “female disease,” it also directly affects the partner in various ways, thus making the partner's presence meaningful (Box 6).

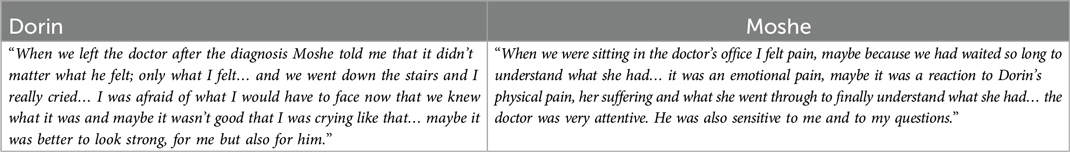

For four couples, receiving the diagnosis was accompanied by feelings of stress and fear. They struggled between hiding their feelings, in order to appear strong in the face of this new information, and revealing their true feelings/fear (Box 7).

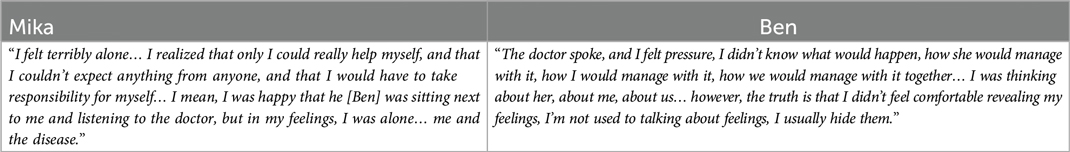

Other couples talked about being together but feeling apart when they received the news. Physically they were both present in the doctor's office, but emotionally/psychologically each was present in the situation mainly with himself/herself (Box 8).

Among three dyads, the women received the diagnosis before being in a cohabiting relationship, and therefore they were the ones who actually informed their partners about their disease. The delivery of this news was more complex for these women than the others, as they were concerned that the partner would fear or be alarmed by the disease and its implications for their relationship. Among these unmarried couples there was a gap between the woman's fear of telling her partner about the disease and the partner's desire to support and help his partner (Box 9).

Theme 3: “The day after the diagnosis”: moving between adversity and growth

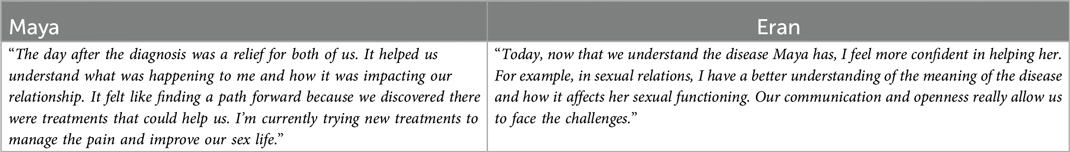

After the endometriosis diagnosis, both partners experienced relief at finally understanding the cause of the women's suffer. The women were pleased to learn they could receive treatment that would help reduce their symptoms, improving their quality of life and their ability to engage in sexual activity. Five partners also talked about feeling relieved that their female partner's condition was finally being addressed, and they felt more confident about providing support and care for her (Box 10).

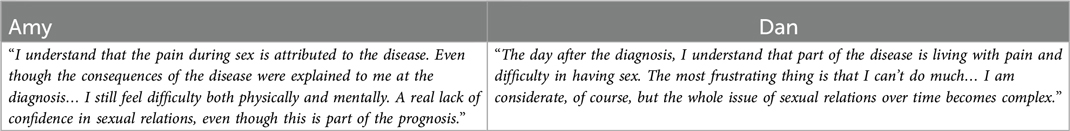

Regarding the post-diagnosis period, six women also talked about having a new understanding of the challenges they faced in maintaining intimacy with their partners. They felt that the pain they experienced during intercourse – which made sex unpleasant or even impossible – now had more “legitimacy” (i.e., it now made more sense). Additionally, according to eight women, the physical and emotional toll of living with endometriosis led to feelings of anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem, which affected their ability to feel sexually confident and comfortable. It should be noted that the topic of sexual intimacy was discussed mainly by the women, and they went into detail and specifics; the male partners, however, discussed this issue in a limited and more general way. Five partners talked about their difficulty in understanding the extent of their partners’ pain and discomfort, although they knew that such pain/discomfort was part of the disease. They felt helpless or frustrated when their partner was in pain, especially if there was little they could do to help (Box 11).

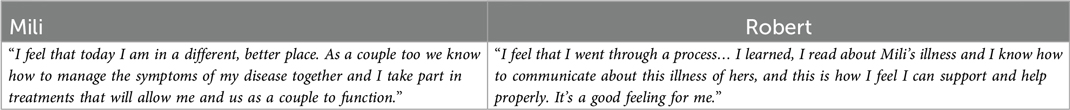

Eight women described how in coping with the disease, they saw the opportunity for change and progress in their relationships, as a result of learning how to manage their physical and emotional symptoms. They sought and found effective pain management strategies such as medication, acupuncture, or physical therapy, and developed coping mechanisms to deal with the emotional toll of the condition. In addition, they learned to advocate for themselves in medical settings by asking questions, seeking second opinions, and exploring different treatment options. Their partners also saw the potential for change and progress. Their personal growth involved learning about the disease, its symptoms, and its impact on their partner's life, as well as providing emotional support and practical help. Partners’ personal growth was also reflected in their ability to learn to communicate effectively with their partner about their needs, feelings, and concerns, and finding ways to be a supportive and loving partner in the face of endometriosis (Box 12).

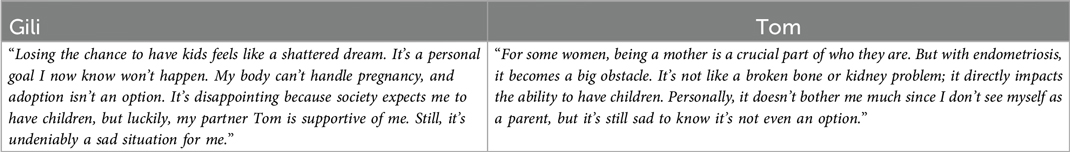

One factor the couples became aware of at diagnosis was that the disease could cause fertility problems. For seven of the women, fertility and bringing children into the world were seen as a fundamental part of their identity and sense of life fulfillment. Some of the women shared that the desire to have children was also tied to cultural and societal expectations, such as the expectation that they would become mothers at some point in their lives (Box 13).

Table 2 presents the classification of main categories and subcategories.

Discussion

In this study we explored the individual coping within the dyad and dyadic experience of women with endometriosis as well as that of their partners in their journey of coping with the disease, from pre-diagnosis to receiving the diagnosis to post-diagnosis. The findings revealed that endometriosis has a profound impact not only on the women diagnosed but also on their partners and the couple as a whole. The diagnosis process and subsequent coping strategies are intertwined with emotional, relational, and societal factors, shaping how both partners experience and respond to the condition. The findings underscore the multifaceted nature of coping with endometriosis, which aligns with Engel's Biopsychosocial Model (22). This model posits that health and illness are influenced not just by biological factors but also by psychological and social dimensions. In this context, the coping mechanisms observed in both women with endometriosis and their partners illustrate the interconnected nature of emotional, relational, and societal factors in shaping responses to this chronic condition. This study highlights the need to view endometriosis as a shared experience within relationships, where both individual and dyadic coping mechanisms play crucial roles in navigating the challenges posed by the disease.

In the first theme, ‘Relationship in the shadow of uncertainty’: Coping with health symptoms prior to the formal endometriosis diagnosis”, the women presented a range of coping mechanisms, from detachment and handling their health symptoms on their own to recognizing the significance of collaboratively (i.e., with their partners), addressing the symptoms and their impacts. This duality between individualism and interdependence brought with it a spectrum of emotions, ranging from guilt and shame to feelings of acceptance and understanding that coping with these uniquely female symptoms needed to be a shared experience. In addition, the first theme's findings point to the long and painful road that the women and their partners had to travel in order to receive a formal diagnosis. Indeed, previous studies have shown the complexity of receiving a diagnosis of endometriosis (33, 34). The findings of the current study reinforce these earlier findings by showing that there are also emotional and marital implications resulting from the mere seeking of an accurate diagnosis. Pre-diagnosis, the current study participants experienced feelings of uncertainty and stress. According to several previous studies, stress in couple relationships is no longer conceptualized as an individual phenomenon but rather as a dyadic stressor (35, 36). Dyadic coping entails mutual involvement of both partners: providing and receiving support from each other and engaging in joint problem-solving activities and shared emotion regulation (37). In line with this notion, Bodenmann (35) coined the term “we-ness”, referring to the function of dyadic coping as enhancing mutual trust and intimacy, mutual attachment and commitment. In this context, the Biopsychosocial Model (22) suggests that emotional responses to health symptoms are not solely individual experiences but are also shaped by interpersonal and social dynamics. This highlights the importance of viewing the pre-diagnosis coping efforts within the broader context of the couple's relationship and the societal expectations surrounding gendered experiences of health. Yet in our study, some of the women preferred, during the pre-diagnosis phase, to cope with their symptoms individually, within the context of the relationship, rather than engaging in joint coping as a couple.

The second theme, “Coping together or alone when receiving the endometriosis diagnosis”, demonstrated how meaningful the presence of a partner during the diagnosis process was, as this presence enabled both partners to offer each other mutual support and also allowed the male partner to understand the meaning and consequences of the disease. Indeed, endometriosis is not solely a female disease; it also affects the partner in various ways, such as in terms of intimacy, fertility, and overall quality of life (38, 39). The presence of a partner during the diagnosis process can help alleviate some of the stress and anxiety associated with the disease and can facilitate open and honest communication about the disease's impact on the relationship.

The significance of mutual support during the diagnosis aligns with the Biopsychosocial Model's emphasis on the role of social and relational factors in health outcomes (22). The model helps elucidate how the presence of a partner not only provides emotional and instrumental support but also contributes to understanding the psychological burden of the diagnosis and the challenges in maintaining intimacy and communication in the face of a chronic illness like endometriosis.

Our findings also indicated that some couples struggled with a kind of tension between hiding their feelings upon receiving the diagnosis (so as to appear strong in the face of it) and revealing their true emotions/fears to their partner. This internal pressure and conflict between hiding vs. revealing feelings/fears may be related to societal expectations of how individuals should respond to a medical diagnosis, particularly as it pertains to gender roles and expectations. Studies have shown that gendered expectations can influence how individuals cope with illness and how they express their emotions [e.g., (40)]. Specifically, women are often expected to express their emotions more freely than men, who may be socialized to suppress their emotions and appear strong and stoic in the face of adversity.

In this context, the concept of “strength” as it applies to men can be further explored. Societal expectations often frame men as the 'strong figure' in relationships, responsible for providing support and maintaining composure. This notion was reflected in the coping strategies seen in our study, where men often emphasized rationality and technical approaches to understanding the diagnosis and managing their partner's health. These coping mechanisms align with existing research, which shows that men tend to use problem-solving and emotionally distanced approaches as a way of maintaining control in the face of stress (41). Such approaches, while seen as manifestations of strength, may also limit emotional expression, contributing to feelings of isolation within the couple dynamic (42).

Indeed, such notions may apply to the findings of the current study, in which couples felt pressure to hide their emotions and appear strong in front of their partners, and this was particularly the case for the men. However, hiding emotions and appearing strong may not always be helpful in coping with the emotional impact of a diagnosis, as it may lead to feelings of isolation and lack of support (43).

The third theme, ‘The day after the diagnosis’: Moving between adversity and growth”, highlights the dialectical lens, viewing the adversity that accompanies the endometriosis diagnosis and the personal/couple growth as potentially coexisting phenomena. Specifically, both members of the couple reported that initially they felt relief that the disease finally had a name, particularly as it took so long to receive a diagnosis. The women hoped that now their medical treatment would be accurately targeted, and that their partners would be better able to support/understand them. However, when the exact meaning of the disease became clear to both couple members, and they became more informed, their distress became apparent once again: Women had to deal with anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem pertaining to the various implications of their diagnosis, and their partners had to deal with hopelessness and difficulty in relieving their partners' pain. In this context, Missmer and colleagues (44) found that the most frequent symptoms that negatively affected various areas of the lives of women diagnosed with endometriosis, including their intimate relationships, were pelvic pain apart from menstruation, painful menstruation, and painful sexual intercourse.

Distress and concern about fertility, in light of the endometriosis diagnosis, also emerged among both couple members. Indeed, women with a history of endometriosis have twice the risk of infertility compared with women without a history of endometriosis (45). In this regard, Moradi and colleagues (46) indicated that the worrying about the possibility of infertility adds to the burden of endometriosis, and negatively affects psychological health, marital relationships, and social interactions, and causes feelings of stigmatization and hopelessness. Thus, it was not surprising that once the symptoms received the “endometriosis” label, dealing with fertility became a cause for additional distress. Nevertheless, some of the positive impacts of receiving the diagnosis – namely, personal and couple growth – also became clear. Women showed self-efficacy in terms of finding tailored and personalized treatments, in addition to standard care, and handling the medical setting in a more effective way. Their partners indicated that finally having a diagnosis strengthened their ability to communicate with their partner, as well as the intimate relationship itself. Our findings echo previous findings (13) regarding men's descriptions of how they live with their partners' endometriosis. The researchers of that study stressed several positive impacts including the development of a supportive approach to the partner which strengthened the relationship, becoming a more sympathetic person and a better partner, and being closer to the partner. These results suggest the possibility of posttraumatic growth (PTG), which is defined as the positive psychological change experienced as a result of a struggle with highly challenging life circumstances (47). In this regard, Marki and colleagues (48) revealed, via the use of focus groups with women who had a confirmed endometriosis diagnosis, that despite many difficulties and problems, women described positive impacts on their life, such as peace, patience, openness, personality development, and gratitude, after they had accepted the diagnosis.

The coexistence of adversity and growth within couples coping with endometriosis reflects the Biopsychosocial Model's framework (22), which recognizes that psychological resilience and adaptation are influenced by an interplay of biological challenges (e.g., physical symptoms), psychological responses (e.g., depression, anxiety), and social support structures (e.g., relational dynamics). This integrated perspective can help explain the potential for posttraumatic growth despite the substantial physical and emotional burdens posed by endometriosis.

The current study had a few limitations. First, the sample was composed mainly of heterosexual couples, with limited variability in socioeconomic status. Additionally, the study did not collect relevant demographic characteristics such as nationality, religion, levels of religiosity, or geographic distribution, which may have impacted the participants' experiences and the generalizability of the findings. Second, the endometriosis-specific information (e.g., disease stage/grading, confirmed diagnosis) was self-reported and not clinically confirmed. Third, most of the study's interviewers were members of the Endo Israel Community Association. Thus, their personal experience of both having the disease and conducting the interviews must be taken into consideration. We would recommend, going forward, that additional experiences among both endometriosis patients and their partners in a more heterogeneous sample be examined.

Clinical implications

The research findings point to the importance of revising comprehensive treatment approaches for endometriosis; specifically, guidelines must be implemented for community physicians to expedite diagnosis, increase awareness, and normalize experiences. Doing so would help reduce diagnostic delays and provide support for individuals and couples. Individual and couple treatment protocols within endometriosis treatment centers, both in hospitals and in the community, should be developed, so as to address emotional needs and facilitate open communication. Additionally, healthcare professionals must deliver the diagnosis with sensitivity and provide information about the potential impacts of the disease on fertility, pregnancy, and childbirth, taking into consideration the couples' concerns. Offering information through workshops, virtual communities, lectures, and treatment centers can further enhance patient support.

Conclusions

In this study the experiences of women with endometriosis and their partners, from pre-diagnosis to post-diagnosis, were explored. The findings revealed that coping with health symptoms before receiving a formal diagnosis involved balancing individualism and interdependence. Couples experienced uncertainty and stress during the pre-diagnosis period. The presence of a partner when receiving the diagnosis played a crucial role in providing support and facilitating communication about the impact of endometriosis on the relationship. However, couples faced challenges in expressing their emotions authentically during the diagnosis process. After receiving the diagnosis, couples felt relief that the disease finally had a name, but they also experienced distress and concern about pain and fertility issues. The study emphasizes the coexistence of adversity and growth, as well as the importance of mutual coping in addressing the psychological effects of endometriosis.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee, School of Social Work, Bar Ilan University (Authorization No. 072202). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SS-A: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. AW: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. B-EF: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YH-R: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shir Shahar, Sharon Livneh, Amit Sarussi-Eliyahu, and Roni Tevet-Adar for helping in recruiting participants as well as to all the participants who took part in this study. This paper benefited from English editing assistance provided by Open AI's ChatGPT (version: GPT-4, a conversational generative AI model).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). Geneva: WHO (2018).

2. Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382(13):1244–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1810764

3. Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Giudice LC, Laufer MR, Leyland N, Missmer SA, et al. Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: a call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2019) 220(4):354.e1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.039

4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Endometriosis in Australia: Prevalence and Hospitalisations: In Focus. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2019).

5. Singh S, Soliman AM, Rahal Y, Robert C, Defoy I, Nisbet P, et al. Prevalence, symptomatic burden, and diagnosis of endometriosis in Canada: cross-sectional survey of 30,000 women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. (2020) 42(7):829–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.10.038

6. Staal AH, van der Zanden M, Nap AW. Diagnostic delay of endometriosis in The Netherlands. Gynecol Obstet Invest. (2016) 81(4):321–4. doi: 10.1159/000441911

7. Nwankudu OC, Idris IO, Ayomoh FI, Onyes U. Exploring the societal burden of endometriosis on women: a meta-ethnography. Preprints. (2021):2021090345. doi: 10.20944/preprints202109.0345.v1

8. ENDO Israel. (2024). Available online at: https://endoisrael.org/ (accessed June 24, 2024). (Hebrew)

9. Wertheimer A, Tzuri-Karo Z, Shoman-Harel N. Endometriosis in numbers: Data and policy recommendations. Annual report. (2022). ENDO Israel. (Hebrew).

10. National Insurance. (2024). Available online at: https://www.btl.gov.il/About/Vaadot/TfasimVichozreiKsafim/Pages/PratimRefuimLicholotEndomatriozis.aspx (accessed June 24, 2024). (Hebrew)

11. Aerts L, Grangier L, Streuli I, Dällenbach P, Marci R, Wenger JM, et al. Psychosocial impact of endometriosis: from co-morbidity to intervention. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. (2018) 50:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.008

12. Ameratunga D, Flemming T, Angstetra D, Ng SK, Sneddon A. Exploring the impact of endometriosis on partners. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. (2017) 43(6):1048–53. doi: 10.1111/jog.13325

13. Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, Mitchell H, Denny E, Raine-Fenning N. A qualitative study of the impact of endometriosis on male partners. Hum Reprod. (2017) 32(8):1667–73. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex221

14. Hämmerli S, Kohl Schwartz AS, Geraedts K, Imesch P, Rauchfuss M, Wölfler MM, et al. Does endometriosis affect sexual activity and satisfaction of the male partner? A comparison of partners from women diagnosed with endometriosis and controls. J Sex Med. (2018) 15(6):853–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.03.087

15. Norinho P, Martins MM, Ferreira H. A systematic review on the effects of endometriosis on sexuality and couple’s relationship. Facts Views Vis ObGyn. (2020) 12(3):197–205.33123695

16. Van Niekerk LM, Schubert E, Matthewson M. Emotional intimacy, empathic concern, and relationship satisfaction in women with endometriosis and their partners. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. (2021) 42(1):81–7. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2020.1774547

17. Facchin F, Buggio L, Vercellini P, Frassineti A, Beltrami S, Saita E. Quality of intimate relationships, dyadic coping, and psychological health in women with endometriosis: results from an online survey. J Psychosom Res. (2021) 146:110502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110502

18. Pereira MG, Ribeiro I, Ferreira H, Osório F, Nogueira-Silva C, Almeida AC. Psychological morbidity in endometriosis: a couple’s study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(20):10598. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010598

19. Lavee Y, Katz R. The family in Israel: between tradition and modernity. Marriage Fam Rev. (2003) 35(1–2):193–217. doi: 10.1300/J002v35n01_11

20. Fogiel-Bijaoui S, Rutlinger-Reiner R. Rethinking the family in Israel: individualization, gender, religion, and human rights. Isr Stud Rev. (2013) 28(2):7–12. doi: 10.3167/isr.2013.280213

21. Girard E, Mazloum A, Navarria-Forney I, Pluchino N, Streuli I, Cedraschi C. Women’s lived experience of endometriosis-related fertility issues. PLoS One. (2023) 18(11):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0293531

22. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. (1977) 196:129–36. doi: 10.1126/science.847460

23. Missmer SA, Tu FF, Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Soliman AM, Chiuve S, et al. Impact of endometriosis on life-course potential: a narrative review. Int J Gen Med. (2021) 14:9–25. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S261139

24. Patton MQ. Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: a personal, experiential perspective. Qual Soc Work. (2002) 1(3):261–83. doi: 10.1177/1473325002001003636

25. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry Research Methods: Choosing among Five Approaches. 4th ed. London: Sage (2018).

27. Ummel D, Achille M. How not to let secrets out when conducting qualitative research with dyads. Qual Health Res. (2016) 26(6):807–15. doi: 10.1177/1049732315627427

28. Brinkman S, Kvale S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (2015).

29. Hudson N, Law C, Culley L, Mitchell H, Denny E, Raine-Fenning N. Conducting dyadic, relational research about endometriosis: a reflexive account of methods, ethics and data analysis. Health. (2020) 24(1):79–93. doi: 10.1177/1363459318786539

30. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

31. Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: Sage (2009).

32. Anney VN. Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: looking at trustworthiness criteria. J Emerg Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. (2014) 5(2):272–81. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/123456789/256

33. Anastasiu CV, Moga MA, Elena Neculau A, Bălan A, Scârneciu I, Dragomir RM, et al. Biomarkers for the noninvasive diagnosis of endometriosis: state of the art and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21(5):1750. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051750

34. Koninckx PR, Ussia A, Adamyan L, Tahlak M, Keckstein J, Martin DC. The epidemiology of endometriosis is poorly known as the pathophysiology and diagnosis are unclear. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. (2021) 71:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.08.005

35. Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples Coping with Stress: Emerging Perspectives on Dyadic Coping. Washington: American Psychological Association (2005). p. 33–49. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2021.1912740

36. Bodenmann G, Meuwly N, Kayser K. Two conceptualizations of dyadic coping and their potential for predicting relationship quality and individual well-being. Eur Psychol. (2011) 16(4):255–66. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000068

37. Revenson TA, DeLongis A. Couples coping with chronic illness. In: Folkman S, editor. Handbook of Coping and Health. New York: Oxford Press (2010). p. 101–23.

38. Maren S, Ariane G, Bettina B, Stephanie H, Magdalena G, Sabine R, et al. Partners matter: the psychosocial well-being of couples when dealing with endometriosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2022) 20(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12955-021-01913-7

39. Margatho D, Makuch MY, Bahamondes L. Experiences of male partners of women with endometriosis-associated pelvic pain: a qualitative study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. (2022) 27(6):454–60. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2022.2097658

40. Greaves L, Ritz SA. Sex, gender and health: mapping the landscape of research and policy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(5):2563. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19052563

41. Seidler ZE, Rice SM, Ogrodniczuk JS, Oliffe JL, Shaw JM, Dhillon HM. Men, masculinities, depression: implications for mental health services from a Delphi expert consensus study. Prof Psychol Res Pract. (2019) 50(1):51. doi: 10.1037/pro0000220

42. Wong YJ, Ho MR, Wang SY, Miller ISK. Meta-analyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes. J Couns Psychol. (2017) 64(1):80–93. doi: 10.1037/cou0000176

43. English T, Lee IA, John OP, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation strategy selection in daily life: the role of social context and goals. Motiv Emot. (2017) 41:230–42. doi: 10.1007/s11031-016-9597-z

44. Missmer SA, Tu F, Soliman AM, Chiuve S, Cross S, Eichner S, et al. Impact of endometriosis on women’s life decisions and goal attainment: a cross-sectional survey of members of an online patient community. BMJ Open. (2022) 12(4):e052765. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052765

45. Prescott J, Farland LV, Tobias DK, Gaskins AJ, Spiegelman D, Chavarro JE, et al. A prospective cohort study of endometriosis and subsequent risk of infertility. Hum Reprod. (2016) 31(7):1475–82. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew085

46. Moradi M, Parker M, Sneddon A, Lopez V, Ellwood D. Impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. (2014) 14:123. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-123

47. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. (2004) 15(1):1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

48. Márki G, Vásárhelyi D, Rigó A, Kaló Z, Ács N, Bokor A. Challenges of and possible solutions for living with endometriosis: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. (2022) 22:20. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01603-6

Appendix 1 Interview guide for women diagnosed with endometriosis

• Please go back to the time when your endometriosis was discovered. Tell me how it was discovered.

• How were you informed that you had endometriosis? Who was with you when you found out?

• Describe your relationship with your partner during the process of getting the diagnosis and in the period after it.

• Tell me about your partner's reactions to the endometriosis diagnosis. How did you feel about his reactions?

• If you were asked to describe your life before and after the discovery of endometriosis, what has changed? What has remained the same?

• What have you discovered about yourself and your partner as a result of the endometriosis diagnosis?

• If you were to divide into sections the way you coped with endometriosis from the beginning until now, how would you divide it? What name would you give each section?

• How has endometriosis affected/changed your relationship with your partner?

• In the eyes of your partner, how has endometriosis affected your relationship?

• In your opinion, how does endometriosis influence your intimate relationship with your partner?

• What helps you cope with endometriosis? How do you feel about this help?

• Tell me about your communication with your partner in regard to the consequences of endometriosis.

• When you bring up your fears and difficulties about your endometriosis in discussions with your partner, what are your thoughts and feelings?

• What advice would you give to other women diagnosed with endometriosis?

• What advice would you give to the partners of women diagnosed with endometriosis?

Appendix 2 Interview guide for partners of women diagnosed with endometriosis

• At what stage of the relationship did you find out that your partner had endometriosis?

• How were you informed that your partner had endometriosis?

• When did the current relationship with your partner begin in relation to the disease and its symptoms?

• Describe to me the feelings and thoughts that went through your head immediately after receiving your partner's diagnosis.

• Describe your relationship with your partner during the process of receiving the diagnosis and in the period after it.

• How has endometriosis affected your relationship with your partner?

• In the eyes of your partner, how has endometriosis affected/changed your relationship?

• In your opinion, how does endometriosis influence your intimate relationship with your partner (both physical and emotional)?

• What helps you cope with endometriosis? How do you feel about this help?

• Tell me about your communication with your partner in regard to the consequences of endometriosis.

• When you bring up your fears and difficulties about endometriosis in discussions with your partner, what are your thoughts and feelings?

• What advice would you give to other partners of women diagnosed with endometriosis?

Keywords: endometriosis, coping, qualitative method, dyadic interview analysis, couples

Citation: Shinan-Altman S, Wertheimer A, Frankel B-E and Hamama-Raz Y (2024) Her, His, and their journey with endometriosis: a qualitative study. Front. Glob. Womens Health 5:1480060. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2024.1480060

Received: 13 August 2024; Accepted: 1 November 2024;

Published: 3 December 2024.

Edited by:

Offer Emanuel Edelstein, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, IsraelReviewed by:

Shani Pitcho, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, IsraelLiraz Cohen-Biton, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel

Copyright: © 2024 Shinan-Altman, Wertheimer, Frankel and Hamama-Raz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shiri Shinan-Altman, c2hpcmkuYWx0bWFuQGJpdS5hYy5pbA==

Shiri Shinan-Altman

Shiri Shinan-Altman Aya Wertheimer2

Aya Wertheimer2 Yaira Hamama-Raz

Yaira Hamama-Raz