- 1Department of Population Studies, School of Statistics and Planning, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

- 2Department of Social Work and Social Administration, School of Social Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Introduction: Violence is a major global public health issue that threatens the physical and mental health of victims. Of particular concern is the increasing evidence which suggests that violence is strongly associated with suicidal behavior including ideation.

Methods: This study uses data from the 2015 Violence Against Children Survey (VACS). This study seeks to highlight the relationship between lifetime violence and suicidal ideation using a nationally representative sample of 1,795 young women (18–24 years) in Uganda.

Results: Results indicate that respondents who experienced lifetime sexual violence (aOR = 1.726; 95%CI = 1.304–2.287), physical violence (aOR = 1.930; 95%CI = 1.293–2.882) or emotional violence (aOR = 2.623; 95%CI = 1.988–3.459) were more likely to experience suicidal ideation. Respondents who were not married (aOR = 1.607; 95%CI = 1.040–2.484), not having too much trust with community members (aOR = 1.542; 95%CI = 1.024–2.320) or not having a close relationship with biological parents (aOR = 1.614; 95%CI = 1.230–2.119) were more likely to experience suicidal ideation. Respondents who did not engage in work in the past 12 months prior to the survey (aOR = 0.629; 95%CI = 0.433–0.913) were less likely to experience suicidal ideation.

Conclusion: The results can be used to inform policy and programming and for integration of mental health and psychosocial support in programming for prevention and response to violence against young women.

Background

Violence is a major global public health issue that threatens the physical and mental health of victims (1). Every year, 1 billion children are affected by a range of forms of violence including physical, sexual and emotional violence (2). Childhood violence is associated with lifelong impact on the individual including increased risk of injury, infectious diseases, mental health problems, reproductive health problems, and non-communicable diseases, as well as damage to the body's nervous, endocrine, circulatory, musculoskeletal, reproductive, respiratory, and immune systems (3).

Studies have established that childhood violence potentially has adverse effects on the mental wellbeing of victims (4, 5). Of particular concern is the increasing evidence which suggests that violence is strongly associated with suicidal behavior including ideation (6, 7). Suicidal behavior is a global public health problem that affects 700,000 people annually (8). In 2019, 1.3% of all deaths were by suicide and 77% of these were in low-and-middle income countries (LMIC) (8). Suicide is the leading cause of death among the population aged 15 to 24 years old globally (9). In Uganda studies on suicide among young people are based on community, clinical and school samples. The prevalence of suicidal ideation was 6.3% in a sample of university students (10); another study found that the prevalence of suicidal ideation among adolescents was as high as 30.6% (11). Among the refugees hosted in Uganda, the prevalence of suicidal ideation is 5% (12). A range of factors are associated with suicidal ideation including financial difficulties (13), family breakdown or conflicts (14), and trauma (11), unemployment (10).

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, and combined abuse were significantly associated with higher rates of suicide attempts (7). Moreover, young women in Uganda have been observed to experience violence more than their male counterparts (15). Yet, there is limited research on the effect of violence on suicidal ideation among vulnerable young women in developing countries (16). This study therefore seeks to highlight the relationship between lifetime violence and suicidal ideation among young women (18–24 years) in Uganda, using a nationally representative dataset. While the main focus is to highlight the relationship between lifetime violence and suicidal ideation, the analysis also controlled for other key variables to see how the effect changes. We focus on young women (18–24 years) because it is the age group that responded to questions on lifetime violence (ever experienced any form of violence). We focus on suicidal ideation because it is more common than attempted or completed suicide (17). Moreover, suicidal ideation is often a precursor to attempted or completed suicide (18–20). The results from such analyses can help design strategic and integrated programs that address the risks that occur simultaneously, related to violence and suicidal ideation among vulnerable women.

Data and methods

Source of data

This study uses data from the 2015 Violence Against Children Survey (VACS). We use the 2015 survey data because it is the latest publicly available nationally representative dataset. The VACS is a nationally representative cross-sectional population-based household survey that targeted adolescents and young people in the age group 13–24. Information from respondents that were aged 18–24 years was used to compute lifetime violence. For the purpose of this study, the analyses are restricted to only female respondents that were aged 18–24 years at the time of the survey.

Sample size, sampling and data collection

The sample included in the analyses is 1,795 female respondents aged 18–24 years. A three-stage cluster sampling design was employed. The first stage involved selecting primary sampling units which were used as a sampling frame. The second stage of sampling involved listing all households in the selected primary sampling unit. Twenty-five households were selected from each sampling unit using probability systematic sampling method. The third stage involved randomly selecting an individual for interview from the selected household. A split sampling approach was used to select female and male respondents. This was intended to protect the confidentiality of respondents and eliminate the chance of the perpetrator and the one sexually assaulted being both interviewed. Data were collected using a face-to-face structured questionnaire programmed on a tablet by well-trained interviewers. Interviewers were trained on the research protocol procedures and ethics in research. During data collection, same-sex interviews were conducted: where female interviewers interviewed female respondents and male interviewers interviewed male respondents (21).

Research ethics

The Makerere University College of Health Sciences ethics review committee and The Uganda National Council for Science and Technology and the Centre for Disease Control (CDC) Institutional Review Board independently reviewed and provided approval to conduct the study. All respondents provided informed consent to participate in the study. However, the data used in this study is publicly available and approval was not required for its re-use.

Measurement of variables

Dependent variable

Measurement of suicidal ideation was measured using the question: “Have you ever thought about killing yourself?”. Response options for the question were “yes” or “no”.

Independent variables

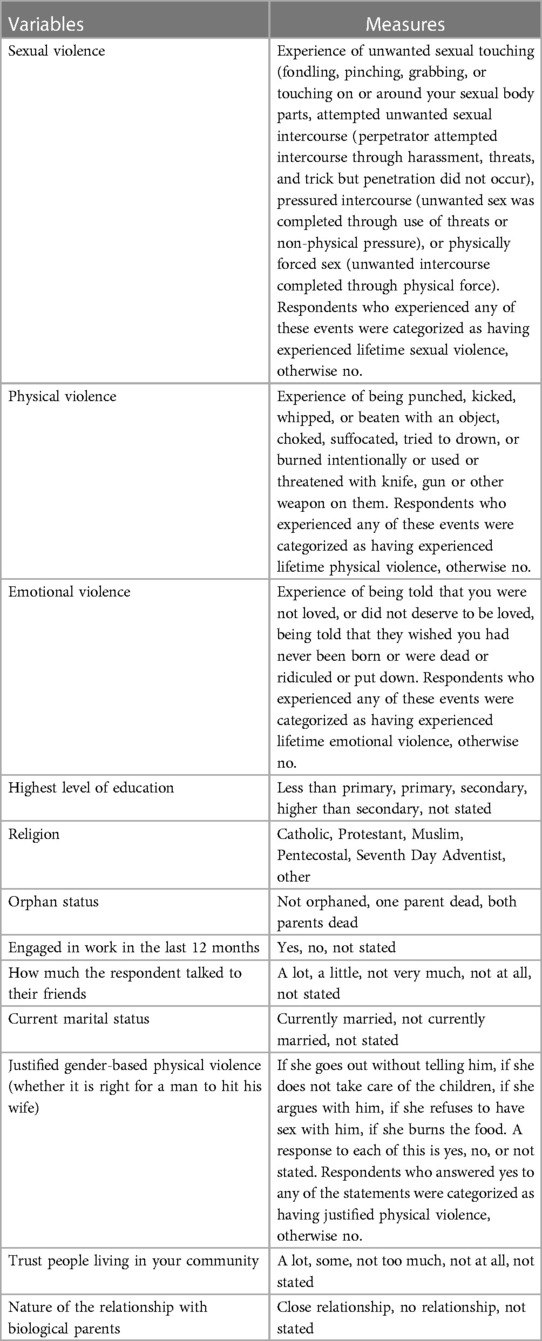

Table 1 summarizes the independent variables and measures included in this study.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Stata software version 15 (22). Three models were run. The first model (Model 1) only controlled for violence (sexual, physical, and emotional) on suicidal ideation. The second model (Model 2) generated unadjusted odds ratios for all variables included in the study. Model 3 generated adjusted odds ratios for all variables included in the study.

Results

Characteristics of respondents

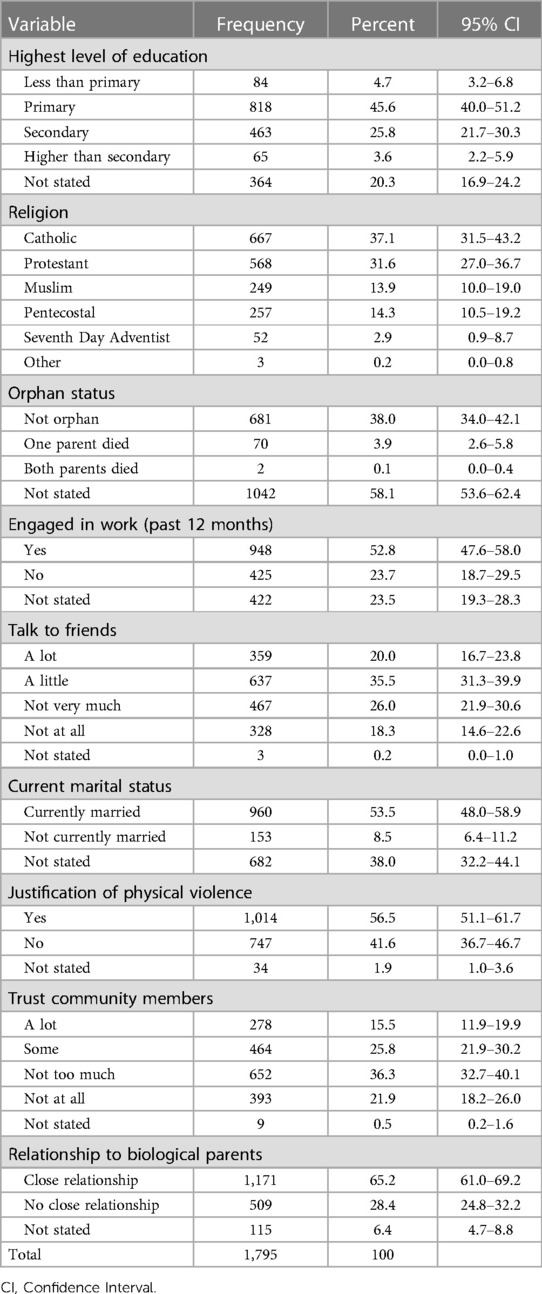

Table 2 shows the characteristics of young women (18–24 years). About four out of every ten respondents (45.6%) had primary level of education. Most respondents (37.1%) were Catholic. Slightly more than half of the respondents (52.8%) had engaged in work in the past 12 months prior to the survey or were currently married at the time of the survey (53.5%). Table 2 shows that 56.5% of respondents justified violence (husbands physically abusing their partners). About sixty-five percent of respondents reported to have a close relationship with their biological parents.

Experience of lifetime violence among young women (18-24 years)

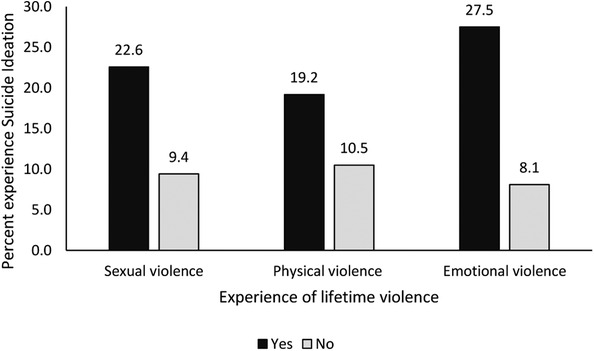

Overall, 72.1% of respondents reported to have experienced physical violence. Slightly more than half (52.0%) of respondents experienced sexual violence and 42.6% reported to have experienced emotional violence. Figure 1 shows that experience of violence (sexual, physical, or emotional) was associated with experience of suicidal ideation. Respondents who experienced sexual violence (22.63% vs. 9.4%), physical violence (19.2% vs. 10.5%) or emotional violence (27.5% vs. 8.1%) were more likely to report higher rates of lifetime suicidal ideation than respondents who did not experience such violence The results in Figure 1 show that suicidal ideation was observed more among respondents who experienced emotional violence (27.5%) compared to other forms of violence: sexual (22.6%) or physical (19.2%).

Factors associated with suicidal ideation

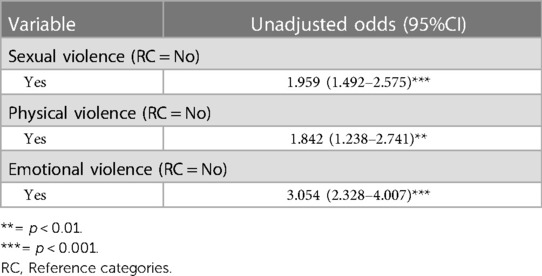

The results in Table 3 show results from a model (Model 1) that controlled for only sexual, physical, and emotional violence. The results indicate that sexual (OR = 1.959; 95%CI = 1.492–2.575), physical (OR = 1.842; 95%CI = 1.238–2.741), and emotional violence (OR = 3.054; 95%CI = 2.328–4.007) were all significantly associated with suicidal ideation. This means that respondents who experienced lifetime sexual, physical, or emotional violence were more likely to experience suicidal ideation than respondents who did not experience any lifetime violence. However, the results indicate that the risk of experiencing suicidal ideation is higher among respondents who experienced emotional violence than other forms of violence (sexual and physical).

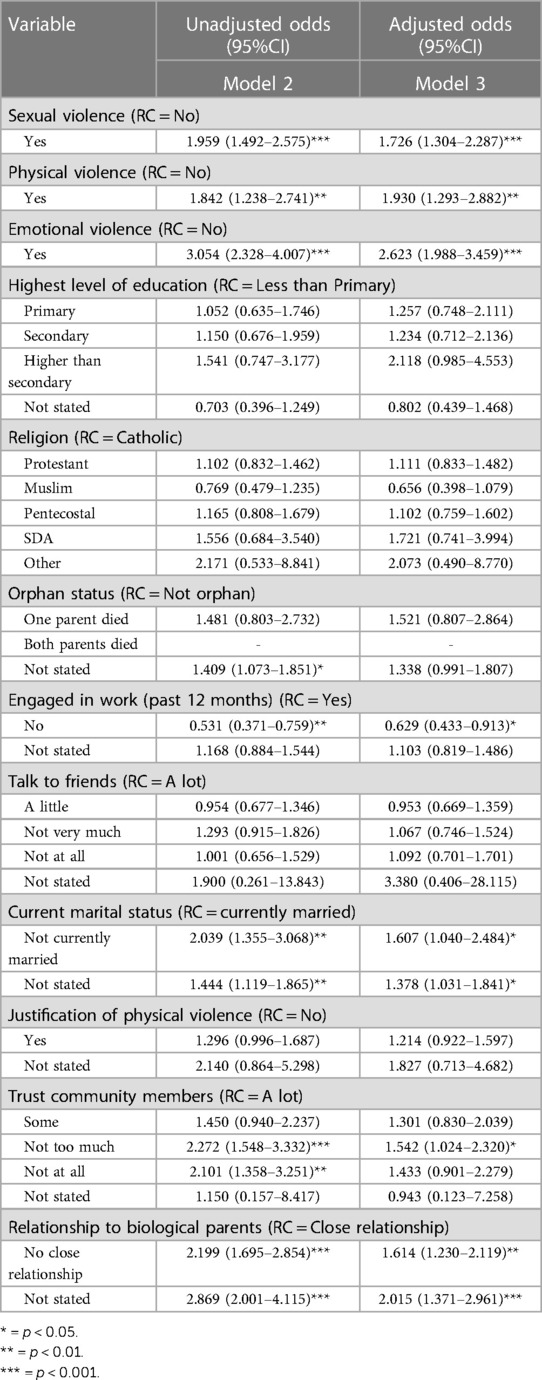

Table 4 shows results from Model 2 (unadjusted odds) and Model 3 (adjusted odds). The results from Model 2 and Model 3 point to the same pattern and direction. After controlling for all background variables (adjusted odds) in the model (Model 3) other than those that measure violence, the results indicate that respondents who experienced lifetime sexual violence (aOR = 1.726; 95%CI = 1.304–2.287), physical violence (aOR = 1.930; 95%CI = 1.293–2.882) or emotional violence (aOR = 2.623; 95%CI = 1.988–3.459) were more likely to experience suicidal ideation than respondents who did not experience sexual, physical or emotional violence.

The results in Table 4 show that respondents who did not engage in work in the past 12 months prior to the survey (aOR = 0.629; 95%CI = 0.433–0.913) were less likely to experience suicidal ideation than respondents who engaged in work in the past 12 months. Not being married (aOR = 1.607; 95%CI = 1.040–2.484) was associated with a more likelihood to experience suicidal ideation than being married. Respondents who reported not to have too much trust with community members (aOR = 1.542; 95%CI = 1.024–2.320) were more likely to experience suicidal ideation than respondents who reported to have a lot of trust with community members. The results from Model 3 indicate that young women (18-24 years) who reported not to have a close relationship with their biological parents (aOR = 1.614; 95%CI = 1.230–2.119) were more likely to experience suicidal ideation than respondents who reported to have a close relationship.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that lifetime violence among young women is high with physical and sexual violence being the most prevalent. These findings are in line with results reported elsewhere (23, 24). Our results demonstrate a significant association between the different forms of violence (physical, emotional, and sexual violence) and suicidal ideation. These results are in line with several studies that have demonstrated a significant relationship between violence and psychosocial distress (25, 26) including suicidal ideation. The reality that young women who experience lifetime sexual, physical, or emotional violence are more likely to experience suicidal ideation underscores the risk violence poses to mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of young women (25, 27). It also underscores the need to integrate mental health and psychosocial support interventions in policy and programming addressing prevention and response to violence against women (28).

The results indicate that the risk of experiencing suicidal ideation is highest among those that experienced emotional violence, followed by sexual violence and the risk is lowest among those that experienced physical violence. This finding resonates with previous findings that report a strong relationship between emotional violence and suicidal ideation (29–31). Emotional abuse can often lead to trauma (30), with lasting consequences which may lead to mental distress especially among young people (32). The results show that being engaged in work was associated with a likelihood to experience suicidal ideation. This may contradict some of the findings that associate access to employment and positive psychosocial outcomes. However, this needs to be understood in the context in which our respondents work. In some of these contexts the workplace could also be one of the sites of violence involving working under hazardous conditions and lack of protective workplace policies (33, 34). Particularly for young women, balancing work pressure and gender roles at home—that has been described as unpaid care work—could also contribute to stress more so in some work settings where childcare services are not well developed (35). Results show that the risk of experiencing suicidal ideation was higher among those who were not currently married. Evidence on the relationship between marriage and suicidal ideation is not conclusive in the literature; some studies have shown that marriage has no influence on suicidal ideation (17). However, it could be that having a companion or spouse (depending on the quality of the relationship) is more likely to build resilience and positive coping mechanisms, but this may be dependent on the context of the relationship between a couple and its quality. Social capital in the form of having a network of community members young women trust was associated with a less likelihood to experience suicidal ideation. Similar findings about the relationship between trust and suicidal ideation have been reported elsewhere (36–38). This further emphasizes the importance of social capital, particularly social networks, in facilitating better coping and mental health for young women (39, 40).

The results show that a positive quality of relationships (close relationships) between young women and their biological parents is associated with a decreased risk of developing suicidal ideations. This is similar to other studies that underscore the contribution of attachment and relationships with family members (especially parents) in facilitating mental health and psychosocial wellbeing (41).

This study has four major limitations. First, this paper uses a single measure of suicidal ideation; yet, there could be a diversity in the measurement scales of suicidal ideation. Second, we are unable to infer causality from the cross-sectional research design: we note the possibility of suicidal ideation occurring either before or after experiencing violence—which we cannot ascertain. Third, the data used in this study may not be free from recall bias; it is possible that those with a history of suicidal ideation may be more likely to recall experiences of violence in their lifetime, or, may have a heightened memory of such events, or may attribute greater salience to past instances of violence. Fourth, although we use the most recent nationally representative dataset available, we recognize the fact that the data were collected 8 years ago, and rates of violence and suicidal ideation could have changed since then.

The results reported in this study demonstrate that young people experience psychosocial problems that may be caused by violence. These results demonstrate the importance of ensuring that policy and programming for prevention and mitigation of violence should integrate strong elements of mental health and psychosocial support especially among young people. Programmes working with young people should endeavor to conduct risk and needs assessments for psychosocial problems. The results of this study further highlight the need to integrate mental health and psychosocial programming in all projects targeting young people.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Makerere University College of Health Sciences Ethics review Committee and The Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. The Centre for Disease Control (CDC) Institutional Review Board independently reviewed and provided approval to conduct the study. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: PK and AK. Data curation: PK. Formal analysis: PK. Investigation: AK, PB and PK. Methodology: AK and PK. Resources: PB, AK and PK. Writing—original draft: PK, AK and PB. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank the AfriChild Centre for aiding access to the data used in this study (from the Ministry of Gender, Labour, and Social Development) through the “Together for Girls” fellowship—awarded to Agatha Kafuko.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Stubbs A, Szoeke C. The effect of intimate partner violence on the physical health and health-related behaviors of women: a systematic review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 2. (2022) 3(4):1157–72. doi: 10.1177/1524838020985541

2. Hillis S, Mercy J, Amobi A, Kress H. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: a systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics. (2016) 137(3):e20154079. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4079

3. Hillis SD, Mercy JA, Saul JR. The enduring impact of violence against children. Psychol Health Med. (2017) 22(4):393–405. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1153679

4. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. (2012) 9(11):e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349

5. Miller AB, Esposito-Smythers C, Weismoore JT, Renshaw KD. The relation between child maltreatment and adolescent suicidal behavior: a systematic review and critical examination of the literature. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. (2013) 16(2):146–72. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0131-5

6. Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. (2017) 2(8):e356–66. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

7. Angelakis I, Gillespie EL, Panagioti M. Childhood maltreatment and adult suicidality: a comprehensive systematic review with meta-analysis. Psychol Med. (2019) 49(7):1057–78. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718003823

8. World Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2019. (2021) Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643 (Accessed October 7 2022).

9. World Health Organization. Mental Health. (2022) Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_1 (Accessed October 7 2022).

10. Wesonga S, Osingada C, Nabisere A, Nkemijika S, Olwit C. Suicidal tendencies and its association with psychoactive use predictors among university students in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Afr Health Sci. (2021) 21(3):1418–27. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v21i3.53

11. Bukuluki P, Wandiembe S, Kisaakye P, Besigwa S, Kasirye R. Suicidal ideations and attempts among adolescents in Kampala urban settlements in Uganda: a case study of adolescents receiving care from the Uganda youth development link. Front Soc. (2021) 58:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.646854

12. Bukuluki P, Kisaakye P, Wandiembe SP, Besigwa S. Suicide ideation and psychosocial distress among refugee adolescents in bidibidi settlement in west Nile, Uganda. Discover Psychol. (2021) 1(1):3. doi: 10.1007/s44202-021-00003-5

13. Kaggwa MM, Arinaitwe I, Muwanguzi M, Nduhuura E, Kajjimu J, Kule M, et al. Suicidal behaviours among Ugandan university students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22(1):234. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03858-7

14. Kinyanda E, Kizza R, Levin J, Ndyanabangi S, Abbo C. Adolescent suicidality as seen in rural northeastern Uganda: prevalence and risk factors. Crisis. (2011) 32:43–51. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000059

15. Black E, Worth H, Clarke S, Obol JH, Akera P, Awor A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence against women in conflict affected northern Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Confl Health. (2019) 13(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0219-8

16. Jiwatram-Negrón T, Meinhart M, Primbetova S, Terlikbayeva A, El-Bassel N. Examining the association between intimate partner violence and suicidal ideation among women living with HIV in a low- and middle-income country. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2021) 30(9):1148–66. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2020.1853297

17. Ovuga E, Boardman J, Wassermann D. Prevalence of suicide ideation in two districts of Uganda. Arch Suicide Res. (2005) 9(4):321–32. doi: 10.1080/13811110500182018

18. Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S, Fisher P, Schwab-Stone M, Kramer R, et al. Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1998) 37(9):915–23. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00011

19. Klonsky ED, May AM, Saffer BY. Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2016) 12(1):307–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204

20. Hubers AAM, Moaddine S, Peersmann SHM, Stijnen T, van Duijn E, van der Mast RC, et al. Suicidal ideation and subsequent completed suicide in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2018) 27(2):186–98. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016001049

21. Ministry of Gender Labour and Social Development. Violence against children in Uganda: Findings from a national survey. Kampala, Uganda: UNICEF (2017). Available at: https://www.togetherforgirls.org/wp-content/uploads/VACS-REPORT-FINAL-LORES-2-1.pdf (Accessed October 7 2022).

23. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF. Uganda Demographic and health survey 2016. Kampala, Uganda and Rockville, Maryland, USA: UBOS and ICF (2018).

24. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and UN Women. National Survey on Violence in Uganda. (2021) Available at: https://africa.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2021/12/national-survey-on-violence-in-uganda—violence-againstwomen-and-girls (Accessed October 7 2022).

25. Masterson R, J Usta A, Gupta J, Ettinger AS. Assessment of reproductive health and violence against women among displaced Syrians in Lebanon. BMC Women's Health. (2014) 14(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-25

26. Bukuluki P, Kisaakye P, Etti B, Ocircan M, Bev R-R. Tolerance of violence against women and the risk of psychosocial distress in humanitarian settings in northern Uganda. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021aa) 18(15):8103. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18158103

27. Ellsberg M, Emmelin M. Intimate partner violence and mental health. Glob Health Action. (2014) 7(1):25658. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25658

28. Tol WA, Stavrou V, Greene MC, Mergenthaler C, Garcia-Moreno C, van Ommeren M. Mental health and psychosocial support interventions for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence during armed conflict: a systematic review. World Psychiatry. (2013) 12(2):179–80. doi: 10.1002/wps.20054

29. Puzia ME, Kraines MA, Liu RT, Kleiman EM. Early life stressors and suicidal ideation: mediation by interpersonal risk factors. Pers Individ Dif. (2014) 56:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.08.027

30. Bahk Y-C, Jang S-K, Choi K-H, Lee S-H. The relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation: role of maltreatment and potential mediators. Psychiatry Investig. (2017) 14(1):37. doi: 10.4306/pi.2017.14.1.37

31. Allbaugh LJ, Mack SA, Culmone HD, Hosey AM, Dunn SE, Kaslow NJ. Relational factors critical in the link between childhood emotional abuse and suicidal ideation. Psychol Serv. (2018) 15:298–304. doi: 10.1037/ser0000214

32. Seff I, Stark L. A sex-disaggregated analysis of how emotional violence relates to suicide ideation in low- and middle-income countries. Child Abuse Negl. (2019) 93:222–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.05.008

33. Woo J-M, Postolache TΤ. The impact of work environment on mood disorders and suicide: evidence and implications. Int J Disabil Human Dev. (2008) 7(2):185–200. doi: 10.1515/IJDHD.2008.7.2.185

34. Chin W-S, Chen Y-C, Ho J-J, Cheng N-Y, Wu H-C, Shiao JSC. Psychological work environment and suicidal ideation among nurses in Taiwan. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2019) 51(1):106–13. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12441

35. Joling KJ, ten Have M, de Graaf R, O’Dwyer ST. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts in informal caregivers: results from the population-based Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study-2 (NEMESIS-2). BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19(1):320. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2317-y

36. Brezo J, Paris J, Tremblay R, Vitaro F, Zoccolillo M, HÉBert M, et al. Personality traits as correlates of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in young adults. Psychol Med. (2006) 36(2):191–202. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006719

37. Yamamura E. Comparison of social Trust's Effect on suicide ideation between urban and non-urban areas: the case of Japanese adults in 2006. Soc Sci Med. (2015) 140:118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.001

38. Smith AR, Kinkel-Ram S, Grunwald W, George TS, Raval V. A pilot feasibility study of reconnecting to internal sensations and experiences (RISE), a mindfulness-informed intervention to reduce interoceptive dysfunction and suicidal ideation, among university students in India. Brain Sci. (2022) 12(2):237. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12020237

39. Sivaram S, Zelaya C, Srikrishnan A, Latkin C, Go V, Solomon S, et al. Associations between social capital and HIV stigma in chennai, India: considerations for prevention intervention design. AIDS Educ Prev. (2009) 21(3):233–50. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.233

40. Verduin F, Smid GE, Wind TR, Scholte WF. In search of links between social capital, mental health and sociotherapy: a longitudinal study in Rwanda. Soc Sci Med. (2014) 121:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.054

Keywords: lifetime violence, suicidal ideation, young women, Uganda, population-based survey

Citation: Kisaakye P, Kafuko A and Bukuluki P (2023) Lifetime violence and suicidal ideation among young women (18–24 years) in Uganda: Results from a population-based survey. Front. Glob. Womens Health 4:1063846. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2023.1063846

Received: 7 October 2022; Accepted: 28 March 2023;

Published: 17 April 2023.

Edited by:

S. M. Yasir Arafat, Enam Medical College, BangladeshReviewed by:

Huynh-Nhu Le, George Washington University, United StatesJoël Djatche Miafo, Uni-Psy et Bien-Être, Cameroon

© 2023 Kisaakye, Kafuko and Bukuluki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Daniel Nzebou, UNIPSY, Cameroon, in collaboration with reviewer JDM

*Correspondence: Peter Kisaakye cGtpc2Fha3llQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†ORCID Peter Kisaakye orcid.org/0000-0003-1859-2078 Agatha Kafuko orcid.org/0000-0001-5142-6907 Paul Bukuluki orcid.org/0000-0002-5388-5469

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Women's Mental Health, a section of the journal Frontiers in Global Women's Health

Peter Kisaakye

Peter Kisaakye Agatha Kafuko

Agatha Kafuko Paul Bukuluki

Paul Bukuluki