- 1Centre for Reproductive Health, Kamuzu University of Health Sciences, Blantyre, Malawi

- 2Heilbrunn Department of Population and Family Health, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York, NY, United States

Background: The lack of usable indicators and benchmarks for staffing of maternity units in health facilities has constrained planning and effective program implementation for emergency obstetric and newborn care (EmONC) globally.

Objectives: To identify potential indicator(s) and benchmarks for EmONC facility staffing that might be applicable in low resource settings, we undertook a scoping review before proceeding to develop a proposed set of indicators.

Eligibility criteria: Population: women attending health facilities for care around the time of delivery and their newborns. Concept: reports of mandated norms or actual staffing levels in health facilities.

Context: studies conducted in healthcare facilities of any type that undertake delivery and newborn care and those from any geographic setting in both public and private sector facilities.

Sources of evidence and charting: Searches were limited to material published since 2000 in English or French, using Pubmed and a purposive search of national Ministry of Health, non-governmental organization and UN agency websites for relevant documents. A template for data extraction was designed.

Results: Data extraction was undertaken from 59 papers and reports including 29 descriptive journal articles, 17 national Ministry of Health documents, 5 Health Care Professional Association (HCPA) documents, two each of journal policy recommendation and comparative studies, one UN Agency document and 3 systematic reviews. Calculation or modelling of staffing ratios was based on delivery, admission or inpatient numbers in 34 reports, with 15 using facility designation as the basis for staffing norms. Other ratios were based on bed numbers or population metrics.

Conclusions: Taken together, the findings point to a need for staffing norms for delivery and newborn care that reflect numbers and competencies of staff physically present on each shift. A Core indicator is proposed, “Monthly mean delivery unit staffing ratio” calculated as number of annual births/365/monthly average shift staff census.

Introduction

The lack of usable indicators and benchmarks for adequate staffing of maternity units in health facilities has constrained planning and effective program implementation for emergency obstetric and newborn care (EmONC) globally. Many complications and deaths can be prevented by a set of medical interventions, coined “signal functions”, defined by the WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, and leading maternal health institutions (1). These signal functions include (1) administering parenteral antibiotics, (2) administering uterotonic drugs, (3) administering parenteral anticonvulsants for pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, (4) manually removing the placenta, (5) removing retained products of conception using manual vacuum extraction or similar procedures, (6) performing assisted vaginal delivery (i.e., vacuum extraction or forceps delivery), (7) performing basic neonatal resuscitation, (8) performing surgery (CS delivery), and (9) administering blood transfusions.

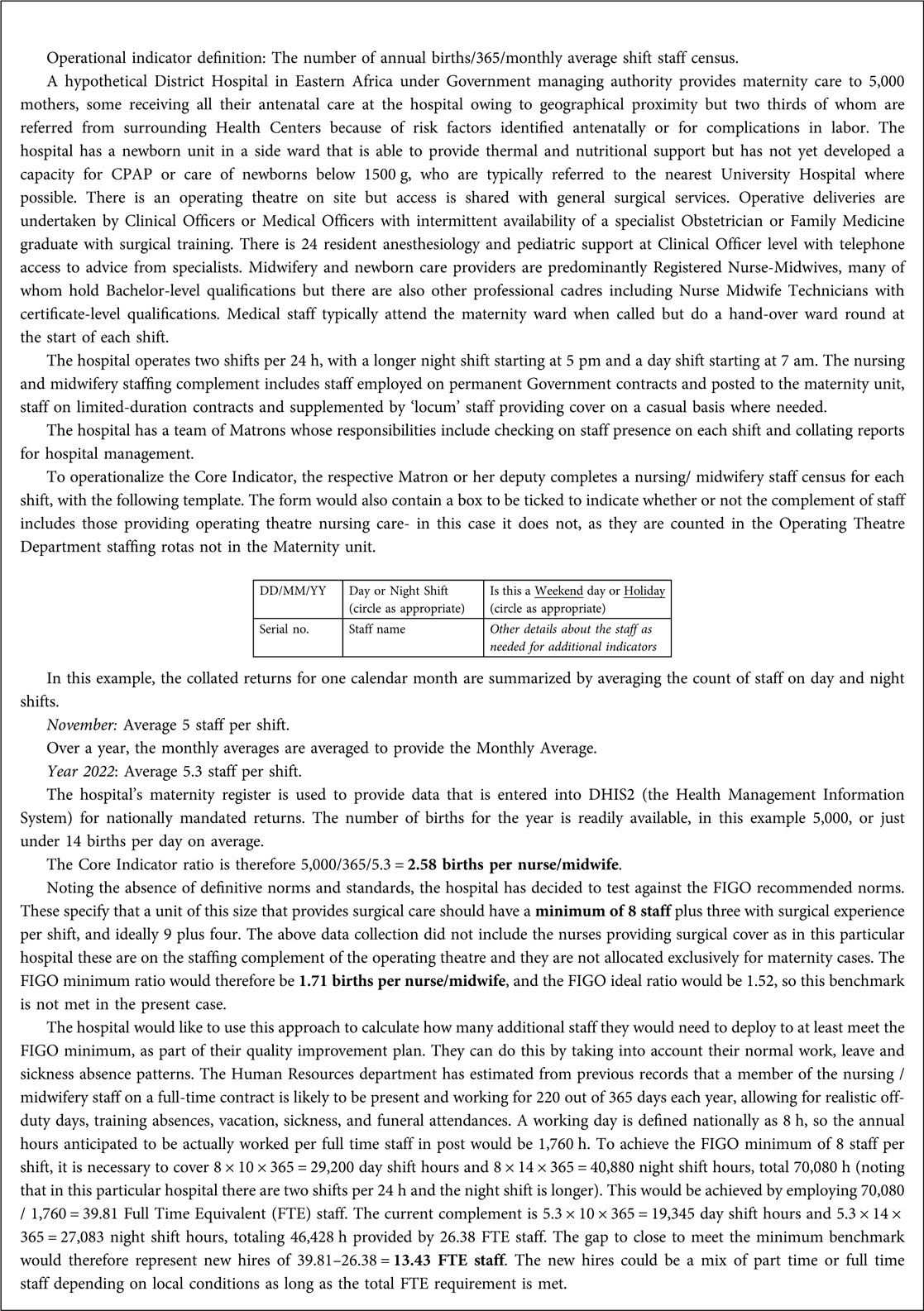

Inadequate staffing can prevent EmONC facilities from providing both basic and comprehensive services. Staff in many settings around the world frequently report working under difficult conditions with large numbers of patients to attend, and suffer distress along with patients and families when complications or even fatalities arise as a result of inadequate staffing despite the best efforts of those on duty. Demoralization and stress can lead staff to seek redeployment to less challenging clinical areas, to the detriment of maternity and newborn services. Box 1 lists the particular challenges that arise from the service requirements of providing safe and acceptable delivery and newborn care, that render formulation of useful metrics difficult.

Box 1. Special challenges for formulation of metrics for staffing of maternity and newborn services.

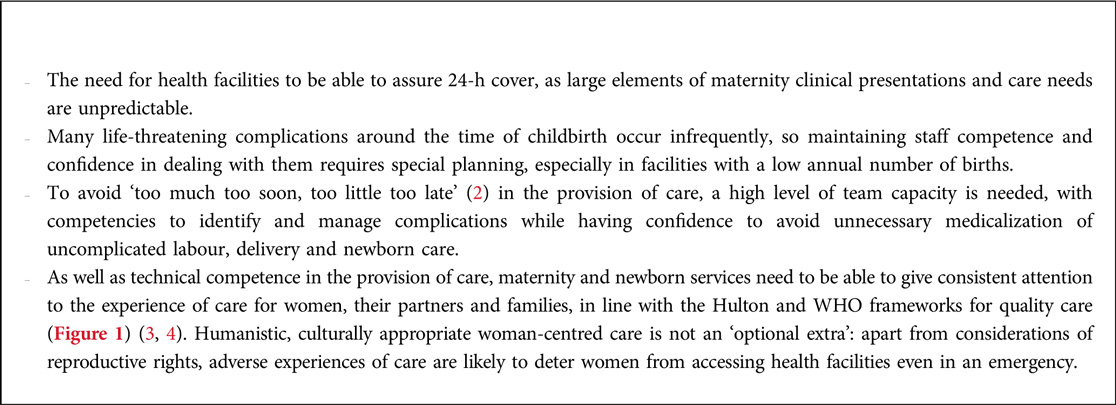

Figure 1. Reprinted from Tunçalp et al. 2015 (4) with permission.

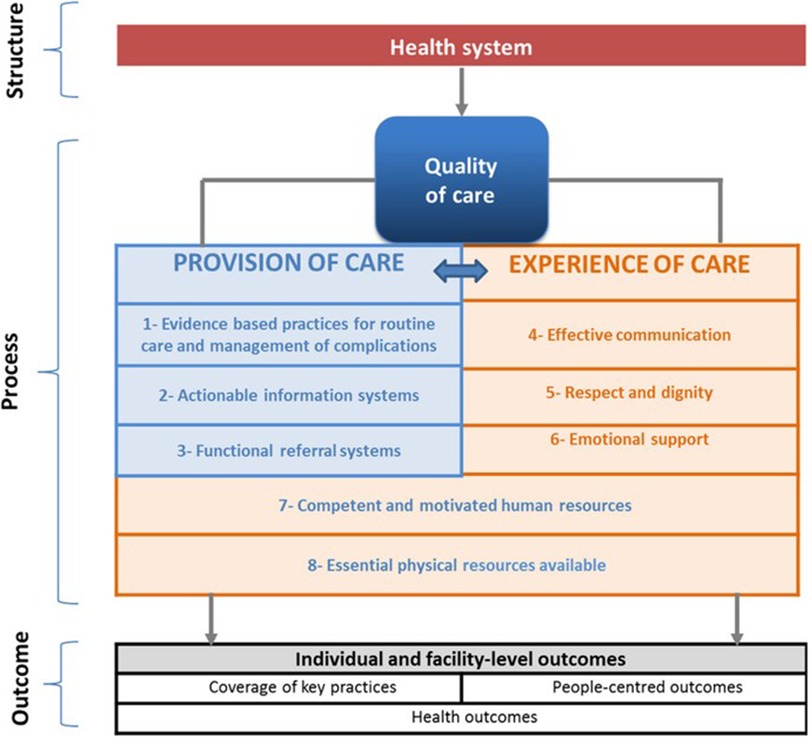

The World Health Organization Health Systems framework recognizes the Health Workforce as a building block contributing to outcomes of improved health, responsiveness, risk protection and efficiency (Figure 2) (5).

Figure 2. Reprinted from WHO 2007 (5) with permission.

In the context of maternity and newborn care the element of responsiveness is especially important and can be identified in four respects shown in Box 2.

The aspect of skill mix is partially addressed by recent moves away from the inclusive concept of “skilled birth attendant” towards recognition of the complexities of provider cadre and levels of training, experience and professional affiliation in different countries. WHO and the international health care professional associations have stated a preferred designation of “skilled health personnel providing care during childbirth” with an emphasis on competencies to “provide and promote evidence-based, human-rights- based, quality, socioculturally sensitive and dignified care, to women and newborns; facilitate physiological processes during labour and delivery to ensure a clean and positive childbirth experience; and (iii) identify and manage or refer women and/or newborns with complications”. (6). However, the current WHO intrapartum care recommendations do not address the matter of optimal staffing ratios and skill mix (7).

The landmark “State of the World's Midwifery” report (8) highlighted the challenge for human resource planning of the nominal facility headcount vs. full time equivalent (FTE1) staff actually present to provide delivery care. This means that metrics based on headcount of health care professionals against population size are an inadequate guide to this essential component of service availability.

The numbers needed and cadre mix of health care professionals involved in maternal and newborn care varies with both the population context of fertility and health in different countries, as well as by how the health system is organized and by national policies regarding levels of care and where women should give birth and want to give birth. Furthermore, emerging evidence continually adds to the list of effective interventions to improve maternal and newborn outcomes that can be provided by staff with midwifery and newborn care competencies, providing further layers of complexity and resulting in generally higher estimates of staffing needs than those reported in the 2014 report (9). These interventions may impinge in different ways across the continuum of care. For example, countries with a high burden of HIV infection require staff with relevant competencies for prevention of maternal to child transmission and sufficient time to provide the related components of care. However, when women have been stabilised on antiretroviral therapy with undetectable viral loads there is no excess care need during labor and delivery itself. By contrast, rolling out of measures to detect and manage fetal bradycardia in the second stage of labor such as use of hand-held Doppler devices and competencies in vacuum delivery have excellent scope to reduce intrapartum stillbirth and neonatal asphyxia but do require additional skilled staff presence in the delivery room (10). When a staffing model has already taken these components of care into account there is greater resilience should an emergency occur. Very recently, a formal trial has provided evidence that the presence of a second midwife in the delivery room can result in a clinically important reduction in perineal and sphincter injury during childbirth (11).

With regard to sick newborns, similar challenges regarding case mix/acuity and skill mix arise to those in labor and delivery care. Rogowski and colleagues analysed patient acuity and staffing arrangements in US newborn intensive care units (12). There were statistical associations between acuity and staffing levels, but nurse education, experience, and specialty certification were not reflected in nurse-to-infant ratios. The challenges of newborn unit staffing in the limited-resource setting of Kenya have been described (13). In the English National Health Service, a concept of “Qualified in Speciality” (QIS) is incorporated into staffing calculations, with for example a minimum of 70% of registered nurses needing to be QIS in lower acuity neonatal special care but all QIS for intensive care (14).

The detrimental impact of staff rotation has received attention in maternal and newborn health policy discussions, for example the Newborn Toolkit (15) where a recommendation is made for “Non rotation of staff in order to ensure the development of institutional memory, knowledge and skills transference, continuity of care and the growth of an experienced workforce.” The FIGO recommendations on staffing requirements noted that rotation can be problematic especially in countries that have followed a “nurse-midwife” professional model such that those working as midwives in delivery units might rotate to unrelated clinical areas (16). There may be staff preference for access to rotation, either for professional development or to take advantage of opportunities such as extra shifts that may be available. Rotation within maternity and newborn units may carry benefits to the service: for example, enabling staff mainly working in antenatal care to refresh their labor ward skills from time to time. This might ensure that advice given in antenatal services is current and consistent with actual practice in the labor ward.

Health facilities providing maternity and newborn care vary considerably in size around the world, from birthing centers with fewer than 300 deliveries per annum up to very large referral hospitals with as many as 30,000 annual births. There has been concern about the ability to offer safe care in small units, as they may fall below a critical mass that can provide all the needed elements of care. For example, 24 h cover with an on-site anesthesiologist or neonatal paediatrician may be impractical. Overall, in smaller hospitals units that maintain a 24-hour capacity to offer delivery care, staffing costs are higher than in larger units owing to loss of economies of scale in rota arrangements (17). Evidence is unclear as to whether maternal and newborn outcomes are necessarily worse in smaller relative to larger units: in a large United States analysis maternal outcomes were similar (18) whereas the adjusted odds of receiving guideline based neonatal sepsis treatment in Nepal were substantially greater in large hospitals (19). Smaller units are likely to have medical staff on-call from home rather than resident in the hospital: a study of low-risk births in Finland showed a greater risk of intrapartum stillbirth when the on-call arrangement was from home (20). A potential indicator and related benchmarks for maternity and newborn unit staffing needs to reflect expected variances related to unit size and cover arrangements.

Although the importance of staffing arrangements has been widely recognized in policy documents, a systematic review of human resources for health interventions for improving maternal health outcomes did not identify any studies, despite including “Personnel systems: workforce planning (including staffing norms), recruitment, hiring, and deployment” in the review scope (21).

With the aim of identifying potential indicator(s) and benchmarks for EmONC facility staffing that might be applicable in low resource settings, this report used a Scoping Review methodology to identify current global literature that may have advanced the field.

The objective of this review was to identify indicators and benchmarks for maternity unit staffing for delivery and newborn care, on which international consensus is currently lacking. The review aimed to consider size of health facility (number of births), case mix (risk status of clients/ patients), skill mix of staff (professional cadre, midwifery competencies, additional clinical roles in supporting maternity care), service organizational arrangements (rotas, rotation) and recognized overall health system resource contexts (low, middle and high income country settings). The review sought to identify any studies that linked staffing levels with maternal and perinatal outcomes. The focus was on reports that could be applicable in low resource settings whether generated in high or low resource countries.

Methods

Table 1 shows the inclusion criteria related to the objectives in terms of Population, Concept and Context (PCC).

Reference was made to the Prisma-ScR Checklist (22) as far as possible within the limitations of the present study. Owing to time constraints the investigators undertook data extraction individually rather than a model of two independent investigators that would have been ideal.

Search syntax in Pubmed was as follows:

(“maternal” OR “newborns” “neonates” OR “neonatal” OR “childbirth” OR “maternity” OR “obstetric”) AND (“staffing” OR “staff allocation” OR “human resources” OR “full-time equivalent employment” OR “staffing adequacy” OR “provider ratio”)

A second search added.

AND (“indicator” OR “recommendation” OR “benchmark”) to the above syntax.

Manual online searching of Ministry of Health and program websites in low resource countries for national maternal and newborn health service policy documents available in English or French was also undertaken.

Title screening

Pubmed search output files (.nbib) were uploaded into a reference manager and titles were flagged for further screening. Downloads of Ministry of Health reports and grey literature were screened by content, aiming for inclusiveness where only a single report was available for a particular country and recognizing that titles alone might not be a good guide to the content of interest for the review.

Titles retained for further scrutiny from the search output files were as follows:

The initial Pubmed search generated 1,204 titles of which 170 were retained after initial screening. Titles retained included 8 systematic or scoping reviews. The second Pubmed search identified 42 titles of which 9 were retained: these proved all to have been identified in the initial search.

From reports and grey literature, 39 reports were identified of which 20 were retained for further examination after initial scrutiny (Table 2).

Data extraction

Individual investigators undertook selection for data extraction using a template in Microsoft Excel, limited to the Abstract where access to the full paper or report was restricted but accessing the full paper or report where available. Data extraction was undertaken for a total of 59 sources, comprising 20 reports/grey literature, 36 journal papers and 3 systematic reviews. A formal quality grading of sources was not undertaken.

Results

Overview of findings

Findings from data extraction are presented in Table 3 in terms of the geographic source, the type of material, clinical focus within EmONC, facility type and how staffing ratios are calculated, followed by detail of the material and comment on applicability for indicator development. 59 papers and reports were included of which 6 were global in scope. Sources by World Health Organization regional office were AFRO: 17, Europe:12, SEARO: 11; Americas: 7, EMRO: 4 and Western Pacific: 2. There were 29 descriptive journal articles, 17 national Ministry of Health documents, 5 Health Care Professional Association (HCPA) documents, two each of journal policy recommendation and comparative studies, one UN Agency document and 3 systematic or scoping reviews. 34 sources related to both delivery and newborn care, 5 only to delivery care while 18 related only to newborn care. Two sources related only to post abortion care (PAC). A majority of sources related to multiple facility types (40 sources) with others relating to referral or University hospitals, District and rural hospitals or primary health centres. Calculation or modelling of staffing ratios was based on delivery, admission or inpatient numbers in 34 reports, with 15 using facility designation as the basis for staffing norms. Other ratios were based on bed numbers or population metrics.

Metrics used in staffing analyses

A single study reported the staffing ratio metric of “Care hours per patient day” (CHPPD). Regarding the quality of staff in post or on duty in relation to their expected duties in maternal, newborn or postabortion care (Qualified in Service, QIS), most reports did not specify competencies beyond the primary clinical qualification. A single study of post abortion care included “confidence to perform post abortion care” as a measure of QIS, in this case reported as 68% (23). Also addressing QIS, a study of neonatal intensive care provision from the Palestinian territories reported that 86/637 (13.5%) of nurses had specialized qualifications (24). In a UK study, neonatal outcomes for very low birthweight babies were favourable where QIS as expressed by the ratio of nurses specialising in neonatology reached 1.3 (25).

Staff rotation arrangements were described in three sources: the Indian national policy document (26) specified that staff should not rotate from the maternity unit. The UK report of a staffing model implementation mentioned rotation within maternal and newborn services (27). Rotation of trained and experience staff was identified as problematic for quality newborn care in a scoping review (28).

Staffing in relation to outcomes

A small number of studies related maternal outcomes to staffing ratios. Maternal mortality was reported in a study of 26,479 births in Nigeria with staffing ratios of 106:1 for doctors in post and 18:1 for midwives in post. There was considerable variation in the ratios between facilities studied, ranging from the most favourable at 1:1 to the most challenging at 22 births per provider. A statistical association was identified between adverse staffing ratios and the incident rate ratio for maternal death (29). It should be noted that staffing numbers here represent staff in post in a clinical department rather than FTE or actual ratios of staff on duty per shift in maternal and newborn care: much of the staff time is likely to have been allocated for a range of duties at the respective hospital such as antenatal clinic and ward duties. A large study aimed to examine birth outcomes in 2011 in England in relation to staffing levels: in this setting of very low mortality a composite outcome of “healthy mother and health baby” was used. There were 4.80 FTE staff for every 100 births (range 2.43–8.66, 20.8 births per provider FTE) of which 0.82 FTE were doctors, 3.08 FTE were midwives (range 1.11 to 4.71, 32.4 births per provider) and 0.90 FTE were support workers. Variation between women's characteristics had much bigger statistical effects than staffing variables in this analysis. Furthermore, levels of midwifery staffing were statistically associated with only two of the 10 indicators, delivery with bodily integrity and intact perineum. The FTE calculations reflect staff in post rather than shift-wise presence in the midwifery unit (30). The variation in staffing ratios within each of these two very different settings is noteworthy, perhaps especially in the English example given the relatively homogeneous structure of the National Health Service maternity system. Comparison of ratios of births per midwife, e.g. 18.1 in Nigeria and 32.4 in England, may be problematic owing to differences in the staffing estimates based on head count or FTE and the way in which the analysis apportions the contribution of a FTE midwife to hands-on delivery and newborn care.

Neonatal intensive care studies have identified a relationship between staffing levels and survival outcomes, for example Callaghan et al. 2003 where an infant to staff ratio of 1:1.61 was reported for very low birthweight neonates who succumbed vs. 1.65 for those that survived (31). As noted above, in a UK study higher ratios of QIS staff were associated with improved newborn survival as was achieving a 1:1 staffing ratio per shift in a setting where many units were reporting ratios of 0.9 staff per neonate in the unit (25).

Recommended and mandated staffing levels

Reports were identified in this review mandating staffing levels of maternity and newborn units authored by Ministries of Health, Health Care Professional Associations and the World Health Organization. The latter contains an indicative recommendation based on an example District fertility pattern such that 3,600 births could be supported by 20 midwives, based on an expectation that each midwife would attend 175 births per annum, derived from a 1991 report (32). Details of shift arrangements for delivery care and participation in other care activities are not given and the indicated number appears to be a head count rather than FTE or shift wise calculation.

FIGO provided a set of staffing recommendations based on delivery numbers at health facilities, recognizing that economies of scale can occur in larger units where dealing efficiently with peaks and troughs of demand may be easier to manage, as well as nurturing of a cadre of experienced staff able to take on a shift-leading role. The consensus statement also recognises the variation in care needs during a maternity episode, with ratios broken down by stage of admission, delivery and postnatal care, ranging from 1:8 in a latent phase observation area to 2 staff per 1 patient during active pushing in the second stage and for immediate postnatal observations (16). The model does not include the contributions of specialists including components of obstetric high care, anaesthesiology and neonatal paediatrics. The French health care professional associations including obstetrics, anaesthesiology, paediatrics, nursing and midwifery produced joint staffing recommendations for maternity units, specifying a 1:1 ratio in labour rooms, with a base FTE of 6 midwives plus an additional FTE midwife for each additional 200 births, meaning that a unit of 2,500 births would have 13.5 FTE midwives (33). This group further specifies that 5.1 midwives for 3,000 births and 7.2 for 4,500 births should be available per shift to provide unscheduled care, thus combining an element of FTE based analysis with consideration of numbers required on duty at any given time (34).

Ministry of Health documents frequently reported staffing norms according to facility designation. Notable reports specifying maternity unit staffing in relation to delivery numbers at the facility are those from India and Senegal. For India the allocation of medical and nursing/midwifery and support staff is specified in detail, for example for Staff Nurses (expected to conduct deliveries there would be 4 for a unit with 100–200 deliveries per month, eight for a unit with 200–500 deliveries and 10 for units delivering more than 500 mothers per month. The shift arrangements translating head count to FTE and staff actually present on shift is not specified (26). In Senegal, a similar incremental model is mandated with three FTE midwives specified for a unit with 31–60 monthly births, rising to 10 staff for a unit of 300 monthly births (35). Staff absence on leave, sickness or training is not factored into this model and detailed specifications for medical staff participation in maternal and newborn care is not included.

Discussion

Taken together, a key observation from the material studied is the lack of consistency and clarity regarding the method of calculation of staffing norms or observed levels. Indeed, most sources do not provide a rationale or justification and do not specify whether the numbers reported are of staff in post, Full Time Equivalent (FTE) staff or staff physically present on the unit. This renders efforts to compare findings or norms across contexts very difficult and would also present difficulties for planners hoping to use these data to estimate hospital, District level and national staffing needs or benchmarks. Reported neonatal nurse staffing ratios most commonly reflect staff actually present on a shift, whereas reported numbers for maternity care are the least consistent in this regard.

The strongest staffing analyses and models seen in the review are those that are based on delivery or actual patient numbers rather than facility designation. In India there have been developments in specifying public health facility staffing norms in some detail, previously in terms of facility designation but the 2016 standards (26) add a refinement of additional staffing for each 200-birth increment. The French consensus document from the health care professional associations follows an approach based on unit size and activity and is notable for the detail provided regarding needs for obstetric, paediatric and anaesthesiology cover. The current Senegal reporting system is aligned with data capture into the District Health Information System (DHIS-2) and the technical document mandates staffing increments based on delivery numbers at the facility. A number of reports assess neonatal intensive care staffing needs in relation to admission numbers and acuity, predominantly from high income countries but including some from low- and middle-income settings. The matter of staff rotation is explicitly mentioned as undesirable in a number of sources. However, no studies describe or formally compare within-unit or external rotation practices in relation to patient outcomes or unit functionality.

The literature provides a strong sense of the importance of adequate staffing for EmONC with many studies identifying gaps in coverage, both in terms of numbers but also skill mix and competencies. The importance of contextualizing staffing arrangements for the local population and service needs is also emphasized and is consistent with a view that a single benchmark for staffing levels is likely to remain elusive. A critical issue is the way that staffing norms are expressed: while several reports recognize the need to capture workforce in terms of Full Time Equivalent (FTE) staff rather than numbers of staff nominally in post, there remains a gap between FTE and actual presence of staff on the delivery unit for a particular shift. For example, the Senegal model specifies a minimum of three FTE staff for facilities with low delivery numbers, but such a complement does not mean that one member of staff would be physically present for every shift once the hours of the working week, sickness absence and annual leave are taken into account. The FIGO consensus statement specifies recommended staffing in terms of FTE present on each shift.

Implications for policy and programming

For maternal and newborn health planners to estimate staffing requirements, operationalize norms and benchmarks and undertake analytical studies exploring service models and their impact, consistent approaches to calculation of staffing ratios and their application as norms or benchmarks is needed. From the present review findings, the lack of clarity across the literature regarding staffing metrics is evident. Documents reviewed for this scoping exercise comprise a mixture of mandated and recommended norms. Often, mandated norms have arisen from previous reports of actual staffing levels that have not necessarily been shown to be ideal or desirable. An example is the World Health Report 2005 (32) where a workload of 175 births per midwife is recommended, based on 1990 experience in Rwanda in a District setting. This ratio has been heavily cited as a WHO-mandated norm, perhaps beyond the intentions of the originators.

While it appears unrealistic to anticipate that an authoritative globally applicable benchmark for delivery unit and newborn care staffing can be identified from existing literature, for policy and programming an interim solution is needed so that indicator(s) are available that governments (at national and sub-national levels) and facility directors find useful for planning and implementing high-quality maternal and neonatal health services. Such indicators need to accurately measure the actual situation in the maternity ward, and offer the ability to relate these to the outcome of interest especially delivery of high-quality of care and reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality.

Proposed core indicator

For both planning and monitoring of staffing of maternity and newborn units, an indicator set is needed that addresses the above considerations. The neonatal intensive care community has largely adopted metrics based on shift-wise ratios, often adjusted for acuity/ dependency needs. However, for maternal and routine newborn care an equivalent approach has been elusive and no definitive indicator was identified in the present review. Arising from the findings of this review, in order to overcome the inconsistencies in calculation and reporting of ratios, we propose that the Core indicator should be the Monthly mean delivery unit staffing ratio, derived from a staff census of those actually present on duty including all Health Care Professional (HCP) cadres on labour ward including medical staff resident or on-call, and operating theatre staff available for Caesarean delivery, but not including students. Census reports (two or three daily depending on the facility's shift pattern) would be averaged in a one-month period. The final staffing ratio is computed as number of annual births/365/[monthly average shift staff census]. Reflecting the focus on provision of EmONC, the scope includes all staff proving basic newborn care (eg resuscitation following delivery, initiation of skin to skin contact/ suckling, thermal care, administration of vitamin K, cord care) but not special or intensive newborn care, for which existing metrics are available. Box 3 provides a worked example for a hypothetical maternity unit, showing how the core indicator is calculated and how it might be applied when estimating staffing needs against a benchmark. In this example using FIGO norms, the minimum ratio excluding surgical staff is a minimum of 1.71 births per nurse/midwife and an ideal ratio is taken as 1.52.

Implications for research

Implementation research is needed to develop and test the practical application of this core indicator in a range of maternity unit settings, its integration into health management information systems such as DHIS-2 and the need for additional related indicators reflecting other essential aspects of care such as QIS and the participation of other clinicians in maternal, newborn and post abortion care. Other than in the field of newborn intensive care, the current literature is not consistent regarding relationships between staffing levels (however measured) and outcomes and research is needed to assess the performance of the above proposed core indicator in this regard, and test its sensitivity to change following adjustment of staffing levels using benchmarks derived from its application.

Limitations

It should be noted that the present scoping review was not intended to focus specifically on Post Abortion Care although abortion related complications contribute to the burden of maternal mortality and are reflected in the EmONC Signal Functions: this is an important gap for future study.

Limitations of the present scoping review include the limited searching for national Ministry of Health and development partner documents and the restriction to English and French language sources. It is highly likely that informative reports and documents exist in off line formats and in other languages. Data extraction was undertaken by individual investigators rather than the ideal of two independent extractors owing to limitations of time and resources.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

WS: developed the concept and framed the scope of the review. AN: undertook syntax development and literature searching. Both authors undertook data extraction. WS: formulated the proposed indicator set. WS: wrote the manuscript and AN contributed revisions for content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation INV-001363.

Acknowledgment

The Re-Visioning Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (EmONC) Project is led by a Steering Committee coordinated by the Averting Maternal Death and Disability (AMDD) program at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, and includes the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UNICEF, UNFPA, and WHO. This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [INV-001363]. Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission. The views expressed in the manuscript are those of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnote

1Also known as WTE, Whole Time Equivalent

References

1. WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, Averting Maternal Death and Disability Program. Monitoring emergency obstetric care: A handbook. Geneva (2009). Available at: http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/obstetric_monitoring.pdf

2. Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, Ciapponi A, Colaci D, Comandé D, et al. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet. (2016) 388(10056):2176–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31472-6

3. Hulton L, Matthews Z, Stones R. A framework for evaluation of quality of care in maternity services. University of southampton. Southampton: University of Southampton (2000). Available at: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/40965/

4. Tunçalp Ö, Were W, MacLennan C, Oladapo O, Gülmezoglu A, Bahl R, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns—the WHO vision. BJOG. (2015) 122(8):1045–9. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13451

5. WHO. Everybody's business — strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. WHO's Framework for action. Cited in: WHO 2010 “Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies”. Geneva. (2007).

6. WHO. Definition of skilled health personnel providing care during childbirth: the 2018 joint statement by WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, ICM, ICN, FIGO and IPA WHO/RHR/18.14. Geneva (2018). Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272818/WHO-RHR-18.14-eng.pdf?ua=1

8. UNFPA. The state of the world's Midwifery: a universal pathway. A woman's Right to health. New York (2014). Available at: https://www.unfpa.org/sowmy-2014

9. ten Hoope-Bender P, Nove A, Sochas L, Matthews Z, Homer CSE, Pozo-Martin F. The ‘dream team’ for sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn and adolescent health: an adjusted service target model to estimate the ideal mix of health care professionals to cover population need. Hum Resour Health. (2017) 15(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0221-4

10. FIGO. Management of the second stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2012) 119(2):111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.08.002

11. Edqvist M, Dahlen HG, Häggsgård C, Tern H, Ängeby K, Teleman P, et al. The effect of two midwives during the second stage of labour to reduce severe perineal trauma (oneplus): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial in Sweden. Lancet. (2022) 399(10331):1242–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00188-X

12. Rogowski JA, Staiger DO, Patrick TE, Horbar JD, Kenny MJ, Lake ET. Nurse staffing in neonatal intensive care units in the United States. Res Nurs Health. (2015) 38(5):333–41. doi: 10.1002/nur.21674

13. Nyikuri M, Kumar P, Jones C, English M. “But you have to start somewhere….”: nurses’ perceptions of what is required to provide quality neonatal care in selected hospitals, Kenya. Wellcome Open Res. (2020) 4:195. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15592.2

14. NHS. Safe, sustainable and productive staffing: an improvement resource for neonatal care. London: National Quality Board. (2018).

15. Nest 360, UNICEF. Implementation toolkit—small and sick newborn kit: human resource. undated. Available at: https://www.newborntoolkit.org/toolkit/human-resources/overview

16. Stones W, Visser GHA, Theron G, FIGO Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health Committee, di Renzo GC, Ayres-de-Campos D, et al. FIGO statement: staffing requirements for delivery care, with special reference to low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2019) 146(1):3–7. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12815

17. Edwards N, Vaughan L, Palmer B. Maternity services in smaller hospitals: a call to action. London: Nuffield Trust (2020). Available at: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2020-08/maternity-services-in-smaller-hospitals-web.pdf

18. Snowden JM, Cheng YW, Emeis CL, Caughey AB. The impact of hospital obstetric volume on maternal outcomes in term, non–low-birthweight pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2015) 212(3):380.e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.09.026

19. Ekman B, Paudel P, Basnet O KCA, Wrammert J. Adherence to world health organisation guidelines for treatment of early onset neonatal sepsis in low-income settings; a cohort study in Nepal. BMC Infect Dis. (2020) 20(1):666. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05361-4

20. Karalis E, Gissler M, Tapper AM, Ulander VM. Effect of hospital size and on-call arrangements on intrapartum and early neonatal mortality among low-risk newborns in Finland. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2016) 198:116–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.10.020

21. Lassi ZS, Musavi NB, Maliqi B, Mansoor N, de Francisco A, Toure K, et al. Systematic review on human resources for health interventions to improve maternal health outcomes: evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health. (2016) 14(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s12960-016-0106-y

22. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169(7):467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

23. Ansari N, Zainullah P, Kim YM, Tappis H, Kols A, Currie S, et al. Assessing post-abortion care in health facilities in Afghanistan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2015) 15(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0439-x

24. Massad S, Tucktuck M, Dar Khawaja R, Dalloul H, Abu Saman K, Salman R, et al. Improving newborn health in countries exposed to political violence: an assessment of the availability, accessibility, and distribution of neonatal health services at Palestinian hospitals. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2020) 13:1551–62. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S270484

25. StC Hamilton KE, Redshaw ME, Tarnow-Mordi W. Nurse staffing in relation to risk-adjusted mortality in neonatal care. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2007) 92(2):F99–103. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.102988

26. India Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Guidelines for standardization of labor rooms at delivery points. New Delhi (2016). Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/maternal-health/guidelines/Labor_Room%20Guideline.pdf

27. RCM. Working with BirthratePlus®. (2013). Available at: https://www.rcm.org.uk/media/2375/working-with-birthrate-plus.pdf

28. Bolan N, Cowgill KD, Walker K, Kak L, Shaver T, Moxon S, et al. Human resources for health-related challenges to ensuring quality newborn care in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Glob Health Sci Pract. (2021) 9(1):160–76. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00362

29. Okonofua F, Ntoimo L, Ogu R, Galadanci H, Abdus-salam R, Gana M, et al. Association of the client-provider ratio with the risk of maternal mortality in referral hospitals: a multi-site study in Nigeria. Reprod Health. (2018) 15(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0464-0

30. Sandall J, Murrells T, Dodwell M, Gibson R, Bewley S, Coxon K, et al. The efficient use of the maternity workforce and the implications for safety and quality in maternity care: a population-based, cross-sectional study. Health Serv Deliv Res. (2014) 2(38):1–266. doi: 10.3310/hsdr02380

31. Callaghan LA, Cartwright DW, O’Rourke P, Davies MW. Infant to staff ratios and risk of mortality in very low birthweight infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2003) 88(2):F94. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.2.F94

32. WHO. World health report 2005: make every mother and child count. Geneva (2005). Available at: https://www.who.int/whr/2005/whr2005_en.pdf?ua=1

33. Sentilhes L, Galley-Raulin F, Boithias C, Sfez M, Goffinet F, le Roux S, et al. Ressources humaines pour les activités non programmées en gynécologie-obstétrique. Propositions élaborées par le CNGOF, le CARO, le CNSF, la FFRSP, la SFAR, la SFMP et la SFN. Gynécologie Obstétrique Fertilité & Sénologie. (2019) 47(1):63–78. doi: 10.1016/j.gofs.2018.11.001

Keywords: childbirth, human resources for health, midwifery, staffing adequacy, EMONC, facility

Citation: Stones W and Nair A (2023) Metrics for maternity unit staffing in low resource settings: Scoping review and proposed core indicator. Front. Glob. Womens Health 4:1028273. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2023.1028273

Received: 25 August 2022; Accepted: 27 January 2023;

Published: 15 March 2023.

Edited by:

Loveday Penn-Kekana, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Katherine E. A. Semrau, Ariadne Labs, United StatesMselenge Mdegela, University of Sunderland, United Kingdom

© 2023 Stones and Nair. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: William Stones d3N0b25lc0BrdWhlcy5hYy5tdw==

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Maternal Health, a section of the journal Frontiers in Global Women's Health

William Stones

William Stones Anjali Nair

Anjali Nair