- 1The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

- 2Department of Emergency, Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

- 3The Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 4Department of Genomic Medicine, AmCare Genomics Lab, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Purpose: This study evaluates the efficacy of rapid clinical exome sequencing (CES) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequencing for diagnosing genetic disorders in critically ill pediatric patients.

Methods: A multi-centre investigation was conducted, enrolling critically ill pediatric patients suspected of having genetic disorders from March 2019 to December 2020. Peripheral blood samples from patients and their parents were analyzed using CES (proband-parent) and mtDNA sequencing (proband-mother) based on Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technology.

Results: The study included 44 pediatric patients (24 males, 20 females) with a median age of 27 days. The median turnaround time for genetic tests was 9.5 days. Genetic disorders were diagnosed in 25 patients (56.8%): 5 with chromosome microduplication/deletion syndromes (11.3%), 1 with UPD-related disease (2.3%), and 19 with monogenic diseases (43.2%). De novo variants were identified in nine patients (36.0%). A neonate was diagnosed with two genetic disorders due to a homozygous SLC25A20 variant and an MT-TL1 gene variation.

Conclusion: Rapid genetic diagnosis is crucial for critically ill pediatric patients with suspected genetic disorders. CES and mtDNA sequencing offer precise and timely results, guiding treatment and reducing mortality and disability, making them suitable primary diagnostic tools.

1 Introduction

Congenital disabilities typically encompass congenital malformations, physiological abnormalities, and metabolic defects related to genetic, environmental, and other unidentified factors. These factors collectively constitute the primary causes of death and congenital disabilities among newborns and infants (Almli et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). Various genetic diseases exist, including chromosome disorders, chromosome microduplication/deletion syndromes, single-gene genetic disorders, and mitochondrial disorders. Based on the latest statistics from the OMIM database (https://omim.org), as of 10 January 2025, the catalogue of genetic diseases exceeds 8400 entries, with new types emerging every year. Predominantly represented are single-gene genetic disorders, many of which manifest relevant clinical phenotypes early on during the neonatal and infancy stages.

Nevertheless, genetic diseases are characterized by clinical phenotypes and genetic heterogeneity. Early neonatal clinical presentations often manifest atypically, potentially overshadowed by common neonatal illnesses, or the relevant phenotypes may not have fully emerged during the neonatal or infancy phases. Certain genetic disorders advance rapidly, swiftly evolving into critical conditions. Absent timely diagnosis and targeted intervention strategies, dire consequences such as mortality and impairment may ensue. In recent years, rapid genome sequencing (rGS) based on next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology has been effectively applied to diagnose the genetic aetiology of neonatal/pediatric intensive care units (NICU/PICU) (Dimmock et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021; Maron et al., 2023; Rodriguez et al., 2024). According to literature reports, the diagnosis reporting period of exome sequencing (ES) typically ranges from 1 to 2 weeks (Gubbels et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021). The diagnosis reporting period of genome sequencing (GS) is usually less than 1 week, allowing prompt treatment adjustments in NICU/PICU pediatric cases (Wang et al., 2020; Sanford Kobayashi and Dimmock, 2022; Lumaka et al., 2023). This can reduce child mortality, prevent ineffective or harmful treatments, minimize unnecessary examinations, and provide prognostic information (Jezkova et al., 2022; Guner Yilmaz et al., 2024). However, the current rapid diagnosis scheme for genetic diseases generally does not include mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequencing. When using ES or GS to detect mtDNA variations, the detection results of mtDNA variations may be influenced by nuclear mitochondrial DNA segments (NUMTs) in the nucleus (Xue et al., 2023). This can lead to missed diagnoses or misdiagnoses of mitochondrial diseases (Gusic and Prokisch, 2021). This study explored the applicability of clinical exome sequencing (CES) based on NGS technology and mtDNA sequencing as the first-line diagnostic technology for critically ill children with suspected genetic disorders.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study cohorts

The Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University Ethics Committee approved this multi-centre prospective cohort study. Informed consent was obtained from the families of all children who were enrolled. From January 2020 to December 2020, this research included 44 critically ill pediatric patients with suspected genetic disorders who were admitted to Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University and Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Children in the NICU and PICU exhibiting one or more systemic symptoms such as unexplained dyspnea, severe uncontrollable infections, persistent jaundice, recurrent convulsions, diminished responsiveness, feeding difficulties, and abnormal muscle tone. (2) Presence of abnormal results in auxiliary examinations, such as hyperlactic acid, hyperammonemia, severe electrolyte disorder, intractable hypoglycemia, congenital heart disease, abnormal screening results of genetic metabolic diseases of blood or urine tandem mass spectrometry, and abnormal imaging and/or electrophysiology pointing to a possible genetic aetiology. (3) CES family (proband-parents) and mtDNA sequencing family (proband-mother) were selected as the first-line diagnosis methods for genetic diseases in children. Family members were informed about the testing methods, objectives, and limitations before genetic testing, and their informed consent was duly obtained. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Children who had previously undergone other genetic disease-related tests (such as karyotype analysis, chromosome microarray analysis (CMA) and ES) and whose results were positive. (2) Children with a documented family history of genetic disorders and identification of confirmed pathogenic gene variations. (3) Cases in which genetic test outcomes could not be used for familial analysis due to specific reasons. (4) Individuals with a documented history of previous trauma, exposure to drugs and toxins, or other factors that can result in organ dysfunction.

2.2 Clinical exome sequencing (CES)

Peripheral blood was collected from pediatric patients and their parents, anticoagulated with EDTA, and stored at 2°C–8°C. Genetic testing and family analysis were conducted using CES technology (AmCare Genomics Lab, Guangzhou, China). The genomic DNA was processed using an ultrasonic disruptor, followed by terminal repair, amplification, and purification steps to prepare the sequencing library. Specific capture probes (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI) were used to hybridize and enrich the DNA sequence of the target region. This region encompasses all exons of approximately 5,000 genes related to known diseases, 30bp introns upstream and downstream and known deep introns. The next-generation sequencing was performed on the MGISEQ-2000 platform of the Huada Zhizao sequencer. The MGISEQ-2000RS high-throughput rapid sequencing reagent kit was used for sequencing. The average sequencing depth of the target region reached 200×, with a coverage interval exceeding 10× accounting for 99.8% and a coverage interval surpassing 20× accounting for 99.5%. The generated sequencing reads were aligned against the human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) using NextGENe. The analysis methods for single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small fragment insertions and deletions (Indels) were as follows: high-frequency variations were filtered using population variation frequency databases such as dbSNP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/), ExAC (http://exac.broadinstitute.org), and gnomAD (http://www.gnomad-sg.org/). Pathogenic variation sites were assessed using various databases, including dbSNP, OMIM, HGMD (http://www.hgmd.org), and ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/). The conservation and pathogenicity of the variations were predicted using SIFT, Polyphen2, MutationTaster, FATHMM, and other prediction software (http://159.226.67.237/sun/varcards/welcome/index). The low-quality sequencing data (with an average coverage of coding sequence less than 3×) were discarded. Copy number variations (CNVs) involving single or multiple exons were analyzed using homogenization calculation (Fromer et al., 2012). Annotations of CNVs refer to databases such as DGV (https://www.dgv/app/home), DECIPHER(https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/), OMIM, and other databases, as well as published literature. The pathogenicity of the variation was classified according to the guidelines of the American Society of Medical Genetics (ACMG) (Richards et al., 2015; Riggs et al., 2020).

2.3 mtDNA sequencing

The mtDNA was sequenced using a combination of long-range PCR (LR-PCR) and NGS sequencing methods. Firstly, the full-length mitochondrial DNA (16529bp) was amplified from total genomic DNA using a one-step LR-PCR method. Subsequently, the sequencing library was prepared through a series of procedures, including ultrasonic disruption, terminal repair, amplification, and purification. The library was then sequenced on the MGISEQ-2000 platform of Huada Zhizhi Sequencer, resulting in a comprehensive coverage depth of approximately 5,000X for each coding base. Mitochondrial variations are expressed as a percentage value, which enables a quantitative assessment of changes in each base. The detection sensitivity of detecting coding region variation heterogeneity or variations load is greater than 2%. The latest Cambridge mitochondrial genome (rCRS NC_012920) was used as the reference sequence. The polymorphism of mitochondrial genome variation is classified based on data from approximately 20,000 mitochondrial genomes. Pathogenicity assessment of mitochondrial gene variations mainly refers to relevant databases, including mtDB (http://www.mtdb.igp.uu.se/), OMIM, and MitoMap (https://www.mitomap.org/MITOMAP), as well as published literature (Wong et al., 2020).

3 Results

3.1 Cohort characteristics

Forty-four critically ill children were enrolled in the study, with 39 (88.6%) inpatients in the NICU and 5 (11.4%) inpatients in the PICU. The cohort included 24 males (54.5%) and 20 females (45.5%). The median age of genetic testing was 27 days (ranging from 4 days to 13 years old), with 22 cases involving newborns (less than 28 days), 20 cases in infancy (28 days–1 year old), and 2 cases involving children (older than 1 year old).

3.2 Genetic disease diagnosis

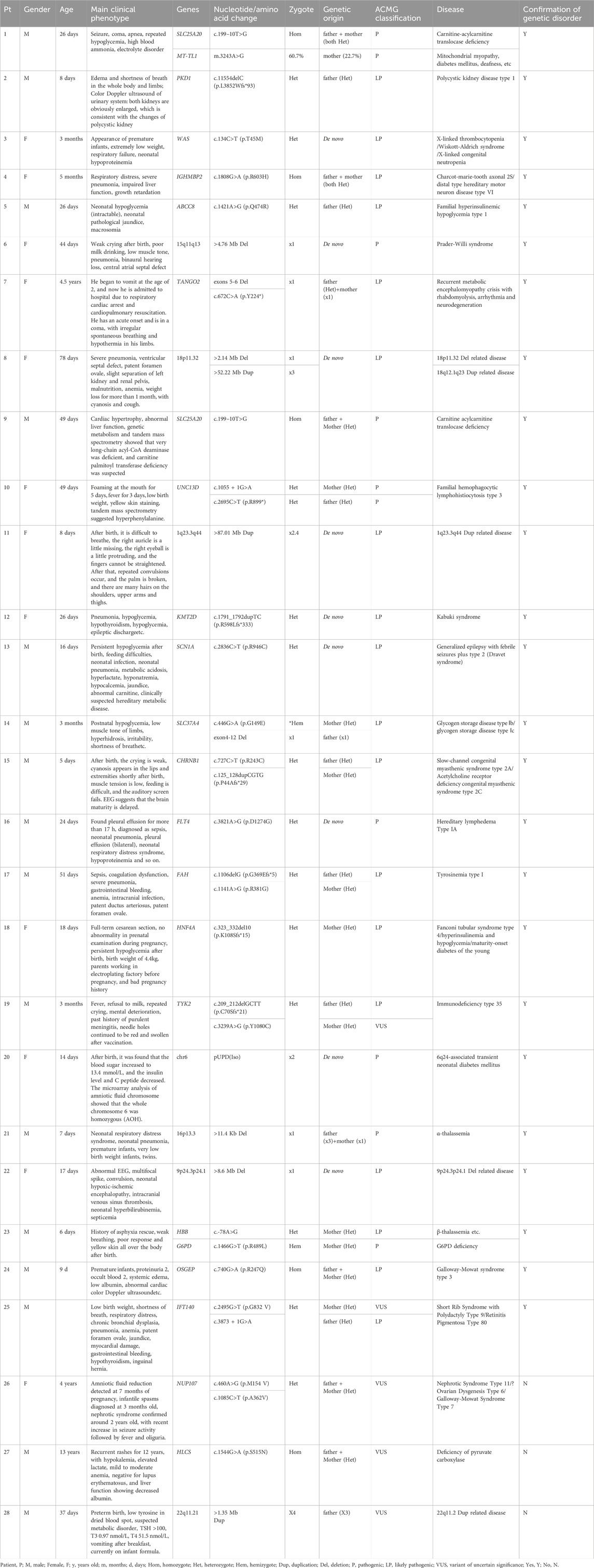

CES and mtDNA sequencing were performed simultaneously, and the median turnaround time for gene detection results was 9.5 days (4∼19 days), involving Sanger sequencing verification or real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR verification (qRT-PCR). Among the 44 critically ill children suspected of having genetic disorders, 28 patients were found to have genetic variations (Table 1). Among them, 25 patients were found to have pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants, leading to a diagnosis of the corresponding genetic disorders and a positive rate of 56.8% (25/44). It is worth noting that one patient was simultaneously detected with both a variation in the SLC25A20 gene (c.199–10T>G) and a mitochondrial gene variation in the MT-TL1 (m.3243A>G). In addition, 4 cases were detected with a varitant of uncertain significance. The diagnosed genetic diseases include 1 case of chromosome microduplication syndrome (1q23.3q44 duplication, 2.3%), 4 cases of chromosome microdeletion-related disorders (9.0%), 1 case of UPD-related disorders (2.3%), and 19 cases of monogenic disorders (43.2%). De novo variations were identified in 9 cases (36.0%), and inherited variants were identified in 16 cases (64.0%). The 19 children were diagnosed with monogenic disorders, of which autosomal recessive (AR) cases constituted 52.6% (10 cases), followed by X-linked (XL) cases at 5.3% (1 case), autosomal dominant (AD) at 26.3% (5 cases), and a combined AR/AD instance at 15.8% (3 cases).

Table 1. Clinical phenotype and genetic variation information of twenty-eight children with detected genetic variations.

3.3 Cases of special genetic diseases

Case 1, a 28-day-old infant, presented with seizures, coma, respiratory arrest, recurrent hypoglycemia, hyperammonemia, electrolyte imbalances, and neutropenia. Genetic analysis revealed a homozygous variation in the SLC25A20 gene (c.199–10T>G), leading to carnitine-acyl carnitine transferase deficiency. Additionally, a mitochondrial gene variation in MT-TL1 (m.3243A>G) was identified, with a mutation load of 60.7% and a maternal contribution of 22.7%. These variations were classified as pathogenic, resulting in diagnoses of both carnitine-acyl carnitine transferase deficiency and mitochondrial disease.

An infant female (case 20), 14 days old, presented with postnatal hyperglycemia reaching up to 13.4 mmol/L, diminished insulin and C-peptide levels. SNP analysis found that the proband has paternal isodisomy of the entire chromosome 6 (pUPD, Isodisomy). Additionally, the analysis of polymorphic sites in the relevant exonic regions confirmed the paternity within the family. This genetic condition is notably linked to 6q24-related transient neonatal diabetes mellitus (TNDM), which presents with a distinct absence of ketosis despite elevated blood sugar levels and may be accompanied by a range of developmental issues. Ultimately, the infant was diagnosed with 6q24-associated TNDM.

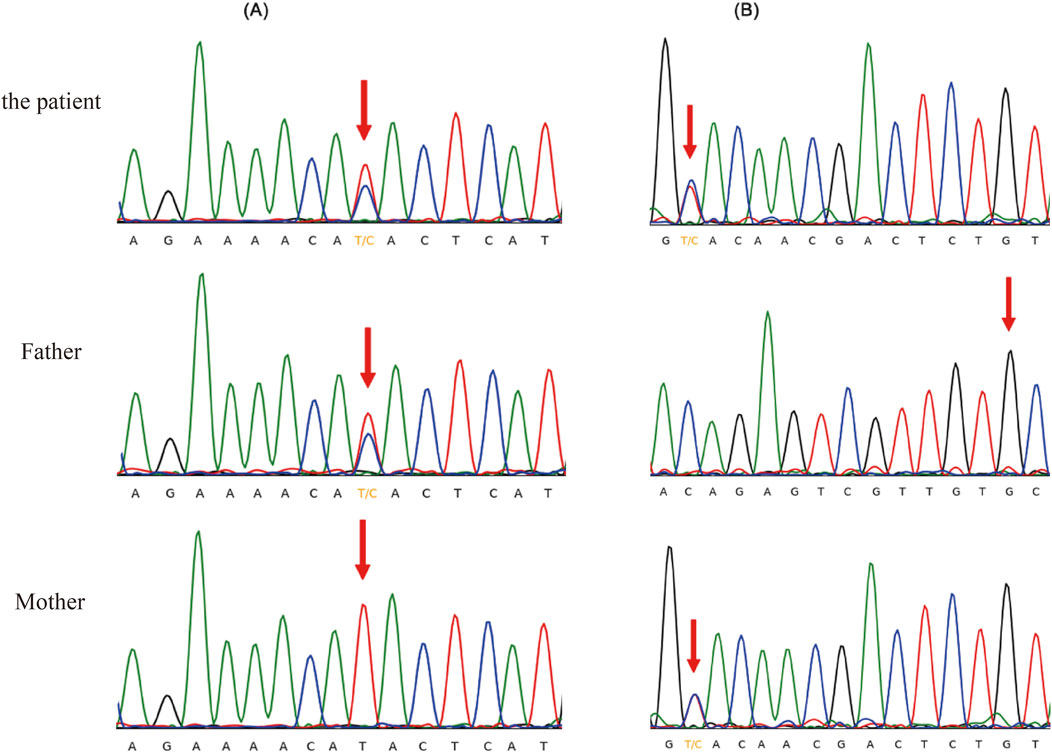

Moreover, a 4-year-old female child (case 26) presents with unexplained massive proteinuria, hypoproteinemia and oedema. When the mother was 7 months pregnant, the ultrasound imaging indicated decreased levels of amniotic fluid. Subsequent CES identified complex heterozygous variants c.460A>G (p.M154 V) and c.1085C>T (p.A362 V) of the NUP107 gene in the children. These variants were inherited from the child’s father and mother (both heterozygous) and were subsequently validated through Sanger sequencing (Figure 1). Notably, these two NUP107 gene variants are novel, as they have not been previously reported in related clinical cases. Their occurrence is infrequent within the gene database of the reference population. The computer-aided analysis predicts that these two variants may affect the structure or function of the protein. According to the American ACMG variation classification guide, these two variations are categorized as “of uncertain significance.”

Figure 1. Sanger sequencing validation of the heterozygous variants in the NUP107 gene. (A) c.460A>G (p.M154V), (B) c.1085C>T (p.A362V).

4 Discussion

Hereditary disorders are the primary cause of mortality in children admitted to NICU/PICU and significantly contribute to infant mortality (Cunniff et al., 1995; Kingsmore et al., 2024). It is well-recognized that most genetic disorders exhibit clinical phenotypes during the neonatal period or early infancy, including conditions associated with variations in mitochondrial DNA (Ebihara et al., 2022; Zeviani and Viscomi, 2022). However, diagnosing the condition can be challenging due to atypical or early-stage clinical manifestations during the neonatal period. Furthermore, some severe disorders manifest rapidly, leading to potentially life-threatening situations. Thus, it is imperative to have an expedient and accurate clinical diagnosis in order to guide treatment decisions and prognostic assessments, thereby reducing disability and mortality rates.

In this prospective multi-centre study, we examined 44 critically ill children from NICU/PICU suspected of having genetic disorders using rapid CES, mtDNA sequencing, and family analysis to elucidate potential genetic etiologies. Among them, 25 children received diagnoses of genetic disorders, resulting in a positivity rate of 56.8%. This group included 5 cases of CNV microdeletion or microduplication-related disorders, 1 case of UPD-related disorder, and 19 cases of monogenic genetic disorders. Notably, one newborn was diagnosed with both a monogenic genetic disorder (SLC25A20 gene variation) and a mitochondrial disorder (m.3243A>G). Among the children diagnosed with hereditary disorders, de novo variations were identified in 36.0% (9/25) of the cases. In addition to identifying pathogenic variants directly linked to the patients’ clinical conditions, genetic testing also has the potential to reveal secondary and incidental findings (SFs and IFs). SFs were defined as clinically significant variants that are actively searched for during sequencing, independent of the patient’s primary indication for testing, while IFs referred to variants that are unintentionally discovered and unrelated to the clinical presentation (Saelaert et al., 2018; Miller et al., 2023). In this study, no SFs or IFs were detected. The identification and management of SFs and IFs remain critical aspects of clinical genomics, particularly as WGS and expanded exome sequencing strategies become more prevalent. Current guidelines emphasized that patients and their families should have the opportunity to opt in or opt out of SF disclosure before testing (Miller et al., 2023). If broader genomic testing approaches, such as WGS, are incorporated into future studies, establishing a structured framework for handling SFs and IFs will be essential. This includes implementing comprehensive informed consent processes, developing standardized disclosure protocols, and ensuring access to genetic counseling to help patients and their families navigate the potential implications of unexpected findings. The ethical, psychological, and clinical considerations associated with SFs and IFs must be carefully balanced to maximize the clinical utility of genomic data while respecting patient autonomy. Future research should further explore best practices for managing these findings in critically ill pediatric patients, integrating advancements in variant interpretation and ethical guidelines to optimize patient care (Saelaert et al., 2018).

NGS technology has become an essential tool for clinicians to diagnose genetic disorders. These methods can be divided into WGS, ES, and targeted sequencing (like CES). The human genome comprises the nuclear genome, which consists of approximately 3 billion base pairs, and the mitochondrial genome, which comprises 16,569 base pairs. Within this genome, all exons, which are protein-coding regions, constitute merely 1%–2% of the total, yet they encompass around 85% of disease-related variations. WGS sequences the whole genome’s bases, including nuclear and mitochondrial genomes. On the other hand, WES is used to sequence the exon regions of over 20,000 known genes. Targeted sequencing is primarily used to sequence specific genes, typically known as pathogenic genes or genes of interest. For instance, CES encompasses all disease-related genes known in the OMIM database. Because the reporting period of conventional NGS-based genetic testing spans 4–6 weeks, it is unsuitable for diagnosing genetic disorders in critically ill or progressively deteriorating children. In recent years, rGS based on NGS technology has been effectively applied to diagnose suspected genetic disorders among children in NICU/PICU settings. Rapid exon sequencing, such as ES, offers diagnosis reports within 1–2 weeks, while the diagnostic reporting time for fast GS is usually under 1 week. In some cases, the preliminary test results can be available within 24 h (Clark et al., 2019), thereby promptly influencing children’s treatment and management in the NICU/PICU. Compared to ES, GS eliminates the need for probe capture in targeted regions, resulting in a shorter reporting period. Consequently, it is the most widely used method for rapidly diagnosing genetic disorders. In this study, the median time to obtain gene detection results through rapid CES and mtDNA sequencing was 9.5 days, ranging from 4∼19 days, including the time required for Sanger sequencing verification or qRT-PCR validation.

The results of several cohort studies on rapid diagnosis of genetic causes indicate that the positive rate of rGS in critically ill children is 30%∼69.7% (van Diemen et al., 2017; Farnaes et al., 2018; Sanford et al., 2019). Similarly, the positive yield of rapid ES is 45%∼72.2% (Bourchany et al., 2017; Lunke et al., 2020; Śmigiel et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020), encompassing both individual proband and family-based examinations and analyses. In a cohort study, rapid CES, encompassing 4,503 known disease-associated genes, was applied to analyze a group of 20 children from the NICU/PICU/CICU, yielding a positive diagnostic rate of 50% (Brunelli et al., 2019). This study used rapid CES and mtDNA sequencing as the first-line diagnostic methods for family analysis. Custom capture probes were designed to target all exons, 30-base pair introns, and well-recognized deep introns within approximately 5,000 disease-associated genes catalogued in the OMIM database. The positive diagnostic rate for gene-related disorders was 56.8% (25/44). Strict inclusion criteria are crucial for improving the diagnostic yield of genetic testing, as narrowing the criteria to individuals with clearly defined phenotypes significantly results in more consistent estimates (Dellava et al., 2011). Studies have demonstrated that applying well-defined criteria, such as family history, clinical symptoms, or age, improves variation detection rates and diagnostic yields across various genetic disorders, including monogenic kidney diseases (Vaisitti et al., 2021), cerebral cavernous malformations (Spiegler et al., 2014), and neurofibromatosis type 1 (Castellanos et al., 2020; Kehrer-Sawatzki and Cooper, 2022). Especially, vaisitti et al. demonstrated that the implementation of strict inclusion criteria in CES greatly improved diagnostic outcomes in monogenic kidney diseases (Vaisitti et al., 2021).

WGS is the sequencing of all bases in the whole genome, which can detect SNV, Indels, and CNVs in all exon regions and include the variation of intron region and non-coding region, genome structure variation (SV), and partial mtDNA variations (Willig et al., 2015). Consequently, WGS may have more advantages in detecting and analyzing different variations. However, the cost of WGS is substantial, and numerous variations are detected, including variations in non-coding regions and deep introns, as well as a significant number of small fragment deletions/repetitions. Because it is difficult to judge pathogenicity without the support of a database, the available information is limited, which hinders its usefulness in clinical disease elucidation. Therefore, the diagnostic positive yield of WGS does not significantly surpass that of ES. Concerning genetic disease diagnosis, ES primarily detects and analyzes the SNV and Indels variations in the exon region of nuclear genes. This technique is utilized to diagnose monogenic diseases. Combined with complementary methodologies for CNV detection, such as CMA, it generally meets most clinical diagnostic requirements. Notably, the average sequencing depth of ES typically reaches around 100×. Previous studies have demonstrated that read-depth analysis can detect copy number variations involving more than three exonic fragments (Hehir-Kwa et al., 2015; Retterer et al., 2015). In this study, the average sequencing depth of CES is approximately 200×. The homogeneous algorithm can effectively analyze CNVs and detect single exon deletions (case 13, case 20). Moreover, it simultaneously analyzes diverse variation types variations, including SNVs, Indels, and CNVs. This approach’s primary focus is the evaluation of approximately 5,000 genes associated with known disorders. The interpretation of variation pathogenicity, accuracy, periodicity, and cost aligns well with the requirements of rapid diagnosis for clinical genetic disorders.

The human mitochondrial genome is a circular, double-stranded DNA molecule comprising 16,569 base pairs and 37 genes. These genes include two rRNA (12S, 16S), 22 tRNA, and 13 polypeptides related to oxidative phosphorylation. The main types of mtDNA variations are point variations and recombination variations. Due to factors such as variation load, tissue distribution, organ-specific reliance on the respiratory chain, and environmental influences, the clinical manifestations of mitochondrial diseases are complex and diverse. These manifestations range from dysfunction in a single organ to multi-system, making it often challenging to differentiate from other diseases (Orsucci et al., 2021). Molecular genetic testing is crucial for neonates suspected of mitochondrial diseases (Mady et al., 2024), as a clear diagnosis can provide targeted treatment for some patients, alleviating their condition. Common genetic testing methods include Sanger sequencing and NGS, which encompasses targeted panel testing, WES, and WGS. According to the Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Neonatal Mitochondrial Diseases (2024) (Jun et al., 2024), when a neonatal mitochondrial disease is highly suspected based on clinical phenotype, targeted testing for common mtDNA and/or nDNA mutations can be performed. For critically ill neonates who require comprehensive testing for mitochondrial-related diseases, and due to the atypical clinical phenotype and the fact that approximately 80% of pediatric mitochondrial diseases are caused by nDNA mutations (Gusic and Prokisch, 2021), the first choice is rapid WES combined with mtDNA testing, with WGS performed when necessary. In this study, the sequencing of mtDNA based on LR-PCR and NGS can effectively address the interference issues of SNVs and CNVs arising from NUMTs. This approach ensures accurate identification of mtDNA variations and their corresponding variation load. In a newborn, a variation load of 60.7% was observed in the MT-TL1 gene, with 22.7% being inherited maternally. This clear genetic basis facilitates the diagnosis of mitochondrial disease. Additionally, the concurrent deficiency of carnitine-acyl carnitine translocation deficiency in the child somewhat obscures the clinical phenotype of mitochondrial disease. Consequently, continuous monitoring and appropriate interventions are imperative to improve prognosis.

However, in our study, we did not systematically track the follow-up of cases without a genetic diagnosis. Future research would collect more comprehensive follow-up data, including the use of WGS or other diagnostic methods, to assess how these approaches may improve diagnostic yields when CES and mtDNA sequencing fail to provide conclusive results.

5 Conclusion

In summary, rapid genetic diagnosis is highly valuable for critically ill pediatric patients suspected of having genetic diseases. It can guide clinical treatment strategies and prognostic assessments in confirmed cases, effectively reducing mortality and disability rates. Furthermore, it establishes a foundation for future genetic counselling regarding fertility-related considerations. For cases lacking definitive diagnoses, the outcomes of genetic testing remain significant for differential diagnosis and guiding therapy. Implementing rGS in clinical practice must prioritize clinical diagnosis and provide practical solutions to patient dilemmas. The precision, regularity, and comprehensibility of results obtained from rapid CES and mtDNA sequencing in this study align with the requirements of clinical diagnosis. Thus, they can be adopted as the primary detection technique for critically ill children who are suspected of having genetic diseases.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhujiang Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

XO: Data curation, Writing – original draft. DC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. YZ: Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. TY: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. QZ: Methodology, Writing – review and editing. LX: Methodology, Writing – review and editing. VZ: Methodology, Writing – review and editing. BW: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (320.6750.2020-06-32).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the study participants and their families.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2025.1526077/full#supplementary-material

References

Almli, L. M., Ely, D. M., Ailes, E. C., Abouk, R., Grosse, S. D., Isenburg, J. L., et al. (2020). Infant mortality attributable to birth defects—United States, 2003–2017. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 69, 25–29. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6902a1

Bourchany, A., Thauvin-Robinet, C., Lehalle, D., Bruel, A. L., Masurel-Paulet, A., Jean, N., et al. (2017). Reducing diagnostic turnaround times of exome sequencing for families requiring timely diagnoses. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 60 (11), 595–604. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.08.011

Brunelli, L., Jenkins, S. M., Gudgeon, J. M., Bleyl, S. B., Miller, C. E., Tvrdik, T., et al. (2019). Targeted gene panel sequencing for the rapid diagnosis of acutely ill infants. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 7 (7), e00796. doi:10.1002/mgg3.796

Castellanos, E., Rosas, I., Negro, A., Gel, B., Alibés, A., Baena, N., et al. (2020). Mutational spectrum by phenotype: panel-based NGS testing of patients with clinical suspicion of RASopathy and children with multiple café-au-lait macules. Clin. Genet. 97 (2), 264–275. doi:10.1111/cge.13649

Clark, M. M., Hildreth, A., Batalov, S., Ding, Y., Chowdhury, S., Watkins, K., et al. (2019). Diagnosis of genetic diseases in seriously ill children by rapid whole-genome sequencing and automated phenotyping and interpretation. Sci. Transl. Med. 11 (489), eaat6177. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aat6177

Cunniff, C., Carmack, J. L., Kirby, R. S., and Fiser, D. H. (1995). Contribution of heritable disorders to mortality in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics 95 (5), 678–681. doi:10.1542/peds.95.5.678

Dellava, J. E., Thornton, L. M., Lichtenstein, P., Pedersen, N. L., and Bulik, C. M. (2011). Impact of broadening definitions of anorexia nervosa on sample characteristics. J. Psychiatric Res. 45 (5), 691–698. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.003

Dimmock, D. P., Clark, M. M., Gaughran, M., Cakici, J. A., Caylor, S. A., Clarke, C., et al. (2020). An RCT of rapid genomic sequencing among seriously ill infants results in high clinical utility, changes in management, and low perceived harm. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 107 (5), 942–952. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.10.003

Ebihara, T., Nagatomo, T., Sugiyama, Y., Tsuruoka, T., Osone, Y., Shimura, M., et al. (2022). Neonatal-onset mitochondrial disease: clinical features, molecular diagnosis and prognosis. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 107 (3), 329–334. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2021-321633

Farnaes, L., Hildreth, A., Sweeney, N. M., Clark, M. M., Chowdhury, S., Nahas, S., et al. (2018). Rapid whole-genome sequencing decreases infant morbidity and cost of hospitalization. NPJ Genom Med. 3, 10. doi:10.1038/s41525-018-0049-4

Fromer, M., Moran, J. L., Chambert, K., Banks, E., Bergen, S. E., Ruderfer, D. M., et al. (2012). Discovery and statistical genotyping of copy-number variation from whole-exome sequencing depth. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91 (4), 597–607. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.005

Gubbels, C. S., VanNoy, G. E., Madden, J. A., Copenheaver, D., Yang, S., Wojcik, M. H., et al. (2020). Prospective, phenotype-driven selection of critically ill neonates for rapid exome sequencing is associated with high diagnostic yield. Genet. Med. 22 (4), 736–744. doi:10.1038/s41436-019-0708-6

Guner Yilmaz, B., Akgun-Dogan, O., Ozdemir, O., Yuksel, B., Hatirnaz Ng, O., Bilguvar, K., et al. (2024). Rapid genome sequencing for critically ill infants: an inaugural pilot study from Turkey. Front. Pediatr. 12, 1412880. doi:10.3389/fped.2024.1412880

Gusic, M., and Prokisch, H. (2021). Genetic basis of mitochondrial diseases. FEBS Lett. 595 (8), 1132–1158. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.14068

Hehir-Kwa, J. Y., Pfundt, R., and Veltman, J. A. (2015). Exome sequencing and whole genome sequencing for the detection of copy number variation. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn 15 (8), 1023–1032. doi:10.1586/14737159.2015.1053467

Jezkova, J., Shaw, S., Taverner, N. V., and Williams, H. J. (2022). Rapid genome sequencing for pediatrics. Hum. Mutat. 43 (11), 1507–1518. doi:10.1002/humu.24466

Jun, L., Danhong, W., Baimao, Z., Fang, F., Ying, W., Chuanzhong, Y., et al. (2024). Experts consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of neonatal mitochondrial diseases. Chin. J. Clin. Med. 2024 (11), 15. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.2096-2932.2024.11.002

Kehrer-Sawatzki, H., and Cooper, D. N. J. H. g. (2022). Challenges in the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) in young children facilitated by means of revised diagnostic criteria including genetic testing for pathogenic NF1 gene variants. Hum. Genet. 141 (2), 177–191. doi:10.1007/s00439-021-02410-z

Kingsmore, S. F., Nofsinger, R., and Ellsworth, K. (2024). Rapid genomic sequencing for genetic disease diagnosis and therapy in intensive care units: a review. NPJ Genom Med. 9 (1), 17. doi:10.1038/s41525-024-00404-0

Liu, Y., Hao, C., Li, K., Hu, X., Gao, H., Zeng, J., et al. (2021). Clinical application of whole exome sequencing for monogenic disorders in PICU of China. Front. Genet. 12, 677699. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.677699

Lumaka, A., Fasquelle, C., Debray, F.-G., Alkan, S., Jacquinet, A., Harvengt, J., et al. (2023). Rapid whole genome sequencing diagnoses and guides treatment in critically ill children in Belgium in less than 40 hours. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (4), 4003. doi:10.3390/ijms24044003

Lunke, S., Eggers, S., Wilson, M., Patel, C., Barnett, C. P., Pinner, J., et al. (2020). Feasibility of ultra-rapid exome sequencing in critically ill infants and children with suspected monogenic conditions in the Australian public health care system. Jama 323 (24), 2503–2511. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.7671

Mady, E. A., Osuga, H., Toyama, H., El-Husseiny, H. M., Inoue, R., Murase, H., et al. (2024). Relationship between the components of mare breast milk and foal gut microbiome: shaping gut microbiome development after birth. Veterinary Q. 44 (1), 1–9. doi:10.1080/01652176.2024.2349948

Maron, J. L., Kingsmore, S., Gelb, B. D., Vockley, J., Wigby, K., Bragg, J., et al. (2023). Rapid whole-genomic sequencing and a targeted neonatal gene panel in infants with a suspected genetic disorder. Jama 330 (2), 161–169. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.9350

Miller, D. T., Lee, K., Abul-Husn, N. S., Amendola, L. M., Brothers, K., Chung, W. K., et al. (2023). ACMG SF v3.2 list for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing: a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 25 (8), 100866. doi:10.1016/j.gim.2023.100866

Orsucci, D., Caldarazzo Ienco, E., Rossi, A., Siciliano, G., and Mancuso, M. (2021). Mitochondrial syndromes revisited. J. Clin. Med. 10 (6), 1249. doi:10.3390/jcm10061249

Retterer, K., Scuffins, J., Schmidt, D., Lewis, R., Pineda-Alvarez, D., Stafford, A., et al. (2015). Assessing copy number from exome sequencing and exome array CGH based on CNV spectrum in a large clinical cohort. Genet. Med. 17 (8), 623–629. doi:10.1038/gim.2014.160

Richards, S., Aziz, N., Bale, S., Bick, D., Das, S., Gastier-Foster, J., et al. (2015). Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med. 17 (5), 405–424. doi:10.1038/gim.2015.30

Riggs, E. R., Andersen, E. F., Cherry, A. M., Kantarci, S., Kearney, H., Patel, A., et al. (2020). Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen). Genet. Med. 22 (2), 245–257. doi:10.1038/s41436-019-0686-8

Rodriguez, K. M., Vaught, J., Salz, L., Foley, J., Boulil, Z., Van Dongen-Trimmer, H. M., et al. (2024). Rapid whole-genome sequencing and clinical management in the PICU: a multicenter cohort, 2016–2023. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 10, 1097. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000003522

Saelaert, M., Mertes, H., De Baere, E., and Devisch, I. (2018). Incidental or secondary findings: an integrative and patient-inclusive approach to the current debate. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 26 (10), 1424–1431. doi:10.1038/s41431-018-0200-9

Sanford, E. F., Clark, M. M., Farnaes, L., Williams, M. R., Perry, J. C., Ingulli, E. G., et al. (2019). Rapid whole genome sequencing has clinical utility in children in the PICU. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 20 (11), 1007–1020. doi:10.1097/pcc.0000000000002056

Sanford Kobayashi, E. F., and Dimmock, D. P. (2022). Better and faster is cheaper. Hum. Mutat. 43 (11), 1495–1506. doi:10.1002/humu.24422

Śmigiel, R., Biela, M., Szmyd, K., Błoch, M., Szmida, E., Skiba, P., et al. (2020). Rapid whole-exome sequencing as a diagnostic tool in a neonatal/pediatric intensive care unit. J. Clin. Med. 9 (7), 2220. doi:10.3390/jcm9072220

Spiegler, S., Najm, J., Liu, J., Gkalympoudis, S., Schröder, W., Borck, G., et al. (2014). High mutation detection rates in cerebral cavernous malformation upon stringent inclusion criteria: one-third of probands are minors. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2 (2), 176–185. doi:10.1002/mgg3.60

Vaisitti, T., Sorbini, M., Callegari, M., Kalantari, S., Bracciamà, V., Arruga, F., et al. (2021). Clinical exome sequencing is a powerful tool in the diagnostic flow of monogenic kidney diseases: an Italian experience, J. Nephrol Clin. exome sequencing is a powerful tool diagnostic flow monogenic kidney Dis. Italian Exp. 34 1767–1781. doi:10.1007/s40620-020-00898-8

van Diemen, C. C., Kerstjens-Frederikse, W. S., Bergman, K. A., de Koning, T. J., Sikkema-Raddatz, B., van der Velde, J. K., et al. (2017). Rapid targeted genomics in critically ill newborns. Pediatrics 140 (4), e20162854. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2854

Wang, H., Qian, Y., Lu, Y., Qin, Q., Lu, G., Cheng, G., et al. (2020). Clinical utility of 24-h rapid trio-exome sequencing for critically ill infants. NPJ genomic Med. 5 (1), 20. doi:10.1038/s41525-020-0129-0

Willig, L. K., Petrikin, J. E., Smith, L. D., Saunders, C. J., Thiffault, I., Miller, N. A., et al. (2015). Whole-genome sequencing for identification of Mendelian disorders in critically ill infants: a retrospective analysis of diagnostic and clinical findings. Lancet Respir. Med. 3 (5), 377–387. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00139-3

Wong, L. C., Chen, T., Schmitt, E. S., Wang, J., Tang, S., Landsverk, M., et al. (2020). Clinical and laboratory interpretation of mitochondrial mRNA variants. Hum. Mutat. 41 (10), 1783–1796. doi:10.1002/humu.24082

World Health Organization (2020). Newborns: improving survival and well-being. Available online at: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborns-reducing-mortality.

Wu, B., Kang, W., Wang, Y., Zhuang, D., Chen, L., Li, L., et al. (2021). Application of full-spectrum rapid clinical genome sequencing improves diagnostic rate and clinical outcomes in critically ill infants in the China Neonatal Genomes Project. Crit. Care Med. 49 (10), 1674–1683. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000005052

Xue, L., Moreira, J. D., Smith, K. K., and Fetterman, J. L. (2023). The mighty NUMT: mitochondrial DNA flexing its code in the nuclear genome. Biomolecules 13 (5), 753. doi:10.3390/biom13050753

Keywords: clinical exome sequencing, mtDNA sequencing, critical illness, rapid genetic diagnosis, pediatric

Citation: Ouyang X, Chi D, Zhang Y, Yu T, Zhang Q, Xu L, Zhang VW and Wang B (2025) Application of rapid clinical exome sequencing technology in the diagnosis of critically ill pediatric patients with suspected genetic diseases. Front. Genet. 16:1526077. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2025.1526077

Received: 11 November 2024; Accepted: 17 February 2025;

Published: 10 March 2025.

Edited by:

Irene Bottillo, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Simone Baldovino, University of Turin, ItalyAmy Brower, Creighton University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Ouyang, Chi, Zhang, Yu, Zhang, Xu, Zhang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bin Wang, Z3p3YW5nYmluQHNtdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Xuejun Ouyang1†

Xuejun Ouyang1† Qian Zhang

Qian Zhang Victor Wei Zhang

Victor Wei Zhang Bin Wang

Bin Wang