- 1Department of Urology, Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

- 2Department of Endocrinology, Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

TP53 (or p53) is widely accepted to be a tumor suppressor. Upon various cellular stresses, p53 mediates cell cycle arrest and apoptosis to maintain genomic stability. p53 is also discovered to suppress tumor growth through regulating metabolism and ferroptosis. However, p53 is always lost or mutated in human and the loss or mutation of p53 is related to a high risk of tumors. Although the link between p53 and cancer has been well established, how the different p53 status of tumor cells help themselves evade immune response remains largely elusive. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of different status of p53 and tumor immune evasion can help optimize the currently used therapies. In this context, we discussed the how the antigen presentation and tumor antigen expression mode altered and described how the tumor cells shape a suppressive tumor immune microenvironment to facilitate its proliferation and metastasis.

Introduction

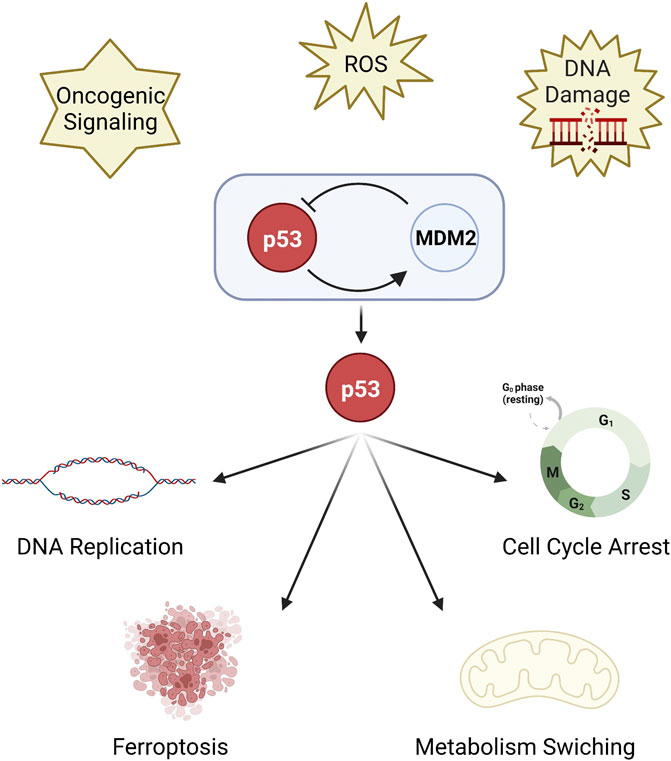

Genome instability is one of the hallmarks of cancer (Negrini et al., 2010; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). TP53 (or p53) is a vital tumor suppressor as it is the key regulator of DNA replication stress and DNA repair (Gaillard et al., 2015; Adriaens et al., 2016; Lindstrom et al., 2022) to maintain genomic stability. p53 responds to diverse cellular stresses, such as DNA damage, oxidative stress and oncogenic signaling (Hafner et al., 2019; Boutelle and Attardi, 2021). In unstressed, non-transformed cells, the expression and activity of p53 are blocked by its negative regulator MDM2 protein to be maintained at a low level (Haupt et al., 1997; Kubbutat et al., 1997; Shieh et al., 1997). On the contrary, the p53-MDM2 interaction will be lost and the expression of p53 is upregulated in stressed cells (Aubrey et al., 2018). Upregulated p53 mediates cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Engeland, 2018) to eliminate damaged cells. p53 has a complicated link with the death or survival of tumor cells through regulating metabolism (Liu and Gu, 2021). Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent mode of death (Dixon et al., 2012) associated with metabolism, has also been recently found to be a p53-regulated activity to inhibit tumor growth (Jiang et al., 2015; Liu and Gu, 2022) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. The function of p53. p53 is a key regulator of DNA replication stress and DNA repair. p53 is inhibited by MDM2 protein, but upregulated under stress. Upregulated p53 mediates cell cycle arrest and DNA replication, metabolism switching, and ferroptosis.

The function of the immune system in control of cancer has been realized (Keast, 1970). Both the elements of innate immune and adaptive immune participate in anti-tumor activities, such as CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and natural killer (NK) cells. The immune response to cancer is thought to be activated in a tumor genome-dependent manner (Chen and Mellman, 2017). Tumor antigens originated from specific gene mutations (Epping and Bernards, 2006) are presented by dendritic (DC) cells or directly presented by tumor cells (Jhunjhunwala et al., 2021) for priming of CD8+ T cells to eliminate tumor cells. Simultaneously, tumor cells escape from immune attack through altering internal genes and shaping external environment, and p53 is one of the key points.

TP53 mutation is strongly associated with a risk of cancer (Harris, 1995; Willenbrink et al., 2020). Previous researches in transcriptome and proteome have demonstrated that TP53 mutation exists broadly in patients suffering tumors, such as urothelial carcinoma of the bladder (Xu et al., 2022), lung cancer (Chen and Roumeliotis, 2020; Gillette et al., 2020), and mutant p53 (hereafter referred to as “mutp53”) always results in poor prognosis (Cao et al., 2021). The mutp53 displays various responses in cellular activity (Muller and Vousden, 2013), mainly dominant-negative effects compared to wild-type p53 (wt-p53) (Muller and Vousden, 2014). The loss of p53 gene also results in developing more advanced carcinomas than p53+/+ and p53+/− in mice skin cancer models (Guinea-Viniegra et al., 2012). Restoring the function or expression of p53 has been proved to inhibit tumor progression and even reduce tumor size in both in vivo and in vitro experiments (Ventura et al., 2007; Guinea-Viniegra et al., 2012).

Based on current research, the hallmarks of tumors with different status of p53 is clear, but how the tumor cells with different p53 status survived from immune surveillance remains largely elusive. Here, we focus on the complicated molecular network of tumor evasion derived from different status of p53 and explore new options of immunotherapy.

The p53 mutation regulates the MHC molecules and reduces immunogenicity of tumor cells

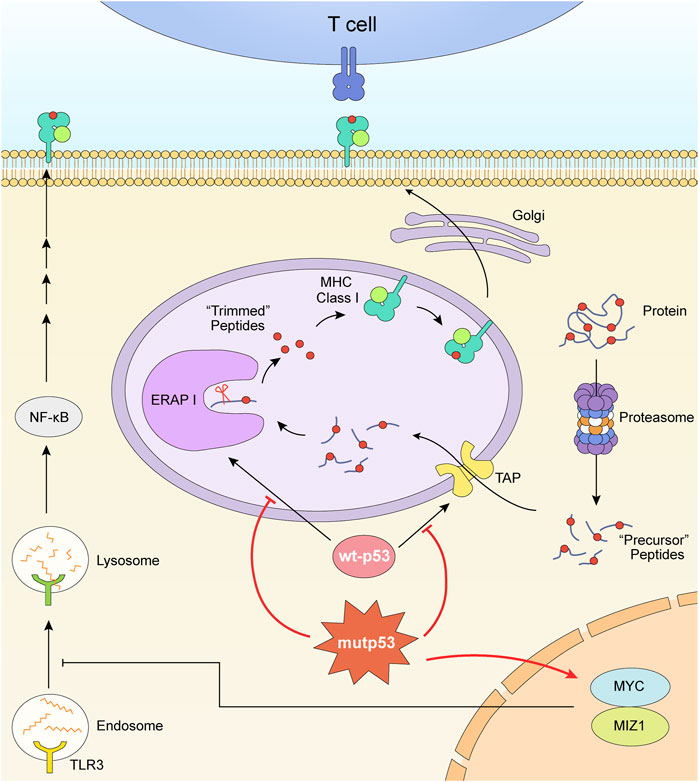

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules expressed on cell surface present peptides to T cells to motivate immune responses. MHC molecules can be divided into two major classes. MHC Class I mainly presents peptides came from intracellular proteins (Jhunjhunwala et al., 2021), which prevent cells from malignant proliferation and stop cancer formation, while MHC Class II presents extracellular proteins to protect cells from infection. MHC I is formed by four domains. The α1, α2, and α3 domain form a heavy chain, and the β2m domain forms a light chain. After the heavy chain combine with β2m, the complex binds to peptides provided by the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) and is transported to the cell surface via the Golgi network (Flutter and Gao, 2004; Cresswell et al., 2005). Under most circumstances, tumor cells lack of the expression of MHC molecules to decrease their immunogenicity.

Tumor cells that lack p53 exhibit markedly lower MHC I molecules (Bubeník, 2004) (Figure 2). The dysfunctional p53 lost its TAP1 activation function. In normal cells, TAP1 is induced by endogenous wild-type p53 (wt-p53) to enhance the transport and the expression of surface MHC-peptide complexes, but not in mutant p53 (R249S) cells and p53-null like HCT116E6 cells (Zhu et al., 1999). Similarly, endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1) is another p53-target gene. ERAP1 acts as a molecular scissor to trim N-terminal extended peptides to be optimal length for assembling with MHC I (Falk and Rötzschke, 2002; Reeves et al., 2020). In human colon carcinoma cell lines, it has been proved that the cognate response element of ERAP1 gene is not accessible to bind silenced p53. The expression of MHC I consequently decreased. (Wang et al., 2013). Wt-p53 limits tumor growth via repressing the myelocytomatosis (Myc) oncogene transcription (Olivero et al., 2020). But the p53 deletion could increase the expression of Myc (Olivero et al., 2020) and the p53-R249S mutation could enhance the activity of Myc (Liao et al., 2017). Upregulated MYC prevented nuclear-derived double-stranded RNA from being recognized by toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), consequently inhibited the activation of downstream MHC I (Krenz et al., 2021).

FIGURE 2. Mutant p53 downregulates the expression of MHC I. The formation and expression of MHC I is related with TAP and ERAP1. TAP transports peptides degraded by proteasome into ER. ERAP1 trims these precursor peptides to be optimal length for assembling with MHC. The dysfunctional p53 lost its TAP1 and ERAP1 activation function. What’s more, the p53 mutation and deletion play roles in upregulating MYC oncoprotein, consequently inhibited the activation of downstream MHC I.

Thus, one of the treatments is to upregulate MHC I expression relying on the re-activation of p53. Pharmacologically activated p53 induced by MDM2 inhibitors enhanced the expression of endogenous retroviruses (ERV). The derepression of ERV triggered ERV-dsRNA-interferon (IFN) pathway followed by activation of antigen processing and presenting genes, including B2M, HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C which encode MHC class I molecules (Zhou et al., 2021). Besides, it is also demonstrated that the dual-targeting PI3K and HDAC inhibitor BEBT-908 can promote ferroptosis of cancer cells by hyperacetylating p53 and promoting the expression of ferroptotic signaling (Liu et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2021). Acetylation-modified p53 in tumor cells induced the upregulation of MHC I via signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) one signaling pathway (Fan et al., 2021).

Another mechanism that p53 impacts immune escape is through affecting the recognition of MHC molecules. The different mutant p53 status interfere with TCR-MHC identification as endogenous proteins presented by MHC I via proteasome. By detecting the secretion of IFNγ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and the proportion of CD69+ T cells, it was found that p53-bearing destabilizing mutations, such as R175H and Y220C mutations, are recognized more efficiently and activated more p53 target T cells than G245S mutation (Shamalov et al., 2017).

As for MHC II, it is found MHC II mediated the T-cell response to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. The p53 deletion caused the downregulation of MHC II and tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor one and receptor 2 (TRAIL-R1/2) which induced immune evasion of AML (Chitlur, 2022; Ho et al., 2022).

How does p53 mutation or deletion shape an immunosuppressive environment?

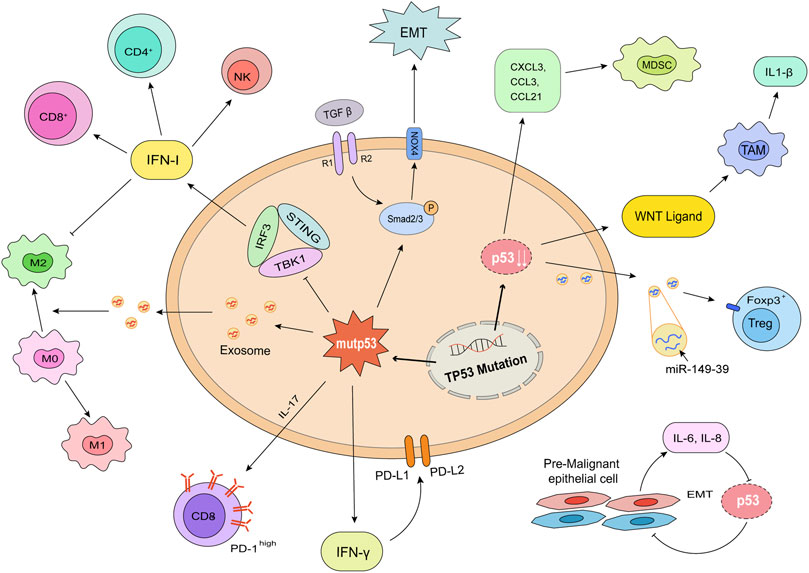

Over the past few centuries, researchers came to realize tumors are more than a group of malignant proliferating cells, but a complex “organ” including tumor cells, stromal cells, immune cells, extracellular matrix, vessels, cytokines, chemokines, as well as other metabolic products (Fu et al., 2021). It has been found that tumor cells transformed themselves (Bottcher et al., 2018) at gene and transcriptome levels (Bi et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021) to shape a surrounding which is suitable for proliferation and differentiation. In this part, we discussed how the changes of p53 influence the cytokines secreting, suppressive ligands expression, and immunocytes with inhibitive function differentiation (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. p53 mutation and deletion shape an immunosuppressive environment. The consequences of mutation (left) or deletion (right) of p53 in tumor cells are shown. Mutp53 decreased the release of IFN I, consequently decreased the infiltration of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells. Mutp53 promoted the formation of exhausted CD8+ T cells through IL-17 signaling. The increased IFNγ played a role in the expression of immunosuppressive ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. Mutant p53 has a synergistic effect with TGF-β to promote EMT. p53 deletion upregulated the releasing of WNT ligands, CXCL1, CCL3, CCL21, and miR-149–39 to enhance the differentiation of TAMs and Tregs. Pre-malignant epithelial cells would release IL-6 and IL-8 to promote EMT. This process promoted tumor formation and metastasis.

The p53 mutation or deletion induces immunosuppressive cytokines and downregulates proinflammatory factors

Cytokines are the main proteins produced and secreted by many different cell types. They mediate immune system responses (Borish and Steinke, 2003) and communication between cells and immune system components (Propper and Balkwill, 2022). For one thing, cytokines can act directly on tumor cells to promote or inhibit their growth; for another, they can also influence the status of tumors by recruiting immune cells or stromal cells. Responses caused by different cytokines also have synergy or confrontation effects (Salazar-Onfray et al., 2007). All above combined the complexity of cytokines therapy (Conlon et al., 2019). Understanding the regulatory mechanism of cytokines may help enhance clinical benefits and reduce adverse reactions. Using RNA interference to reactivate p53 briefly in the p53-dificient mouse liver carcinoma model, (Xue et al., 2007) found that tumor proliferation is restricted and dependent on the cellular senescence program and consequently increased inflammation cytokines. We hypothesized that the influence of p53 in different status on tumor immunity may be achieved through the influence of cytokines.

Type I IFN (IFN I) is an important cytokine whose response plays significant roles in antiviral innate immune and anti-tumor adaptive immune (Woo et al., 2015). One of the mechanisms to active immunity is to upregulate the expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), thereby giving rise to ISG DC cells resembling type 1 DC cells. ISG DC cells present intact tumor-derived peptide-MHC I to reactivate antitumor immunity (Corrales et al., 2016; Duong et al., 2022). The attenuation of IFN I response is conducive to tumor evasion. Current studies confirmed that IFN I response is activated by stimulator of IFN genes (STING) pathway. Cells with mutp53 suppress downstream signaling of cGAS/STING. Mutp53 prevents STING-IRF3-TBK1 trimeric complex formation and IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) activation via interacting with TANK binding protein kinase 1 (TBK1) (Balka et al., 2020; Ghosh et al., 2021), consequently downregulates the release of IFN I.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is an important trigger of tumor-promoting inflammation. Tumor cells exposed to IL-6 activate the oncogenic STAT3 transcription factor to promote epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is the first step for tumor cell migration. MiR-34a, activated by p53, is a major inhibitor through targeting IL-6R (Rokavec et al., 2014). In studies investigating aging and carcinogenesis, it was found that pre-malignant epithelial cells induce EMT through a paracrine mechanism of IL-6 and IL-8. IL-6, and IL-8 caused the loss of p53 in normal cells and the p53 deficiency exacerbated the pro-malignant secretory activity, forming a vicious cycle (Downward et al., 2008). Whereas co-expression of wt-p53 and NF-κB in tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) can enhance the survival of tumor cells through secreting IL-6, CXCL-1, and promoting tumor associated neutrophils recruitment (Lowe et al., 2014).

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is an immunosuppressive cytokine that has both positive and negative roles in tumor formation (Yang et al., 2010). The canonical response of TGF-β is the phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3, which then combine with SMAD4 to mediate growth inhibition (Yang et al., 2010). TGF-β acts as a tumor suppressor and the loss of TGF-β signaling effectors is the molecular basis to develop tumors. A study in prostate cancer discovered the TGF-βRII and Smad4 in tumor cells taper off during the progression process (Zeng et al., 2004). TGF-β also acts as a tumor promoter owing to its immune suppressive effects (Batlle and Massague, 2019). TGF-β inhibits the differentiation and proliferation of effector T cells (Teffs) but enhances the fraction of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and other suppressive cells through the phosphorylation of Smad family proteins. Blocking TGF-β in breast cancer cell lines was effectively to counteract its effects (Yi et al., 2021).

The dual functions of TGF-β in tumor cell survival are interconnected with different status of p53. TGF-β mediates the inhibition of p53 and DNA damage response to conduce to tumor progression. These effects are achieved through the downstream signals of miR-100 and miR-125b upregulated by SMAD2/3 transcription factors (Ottaviani et al., 2018). Furthermore, TGF-β1 antagonizes p53-induced apoptosis in precancerous cells via switching the viral E2-associated factor 4 (E2F-4)/p107 complex to Smad/E2F-4 corepressor, which represses transcription and translation of p53 (Lopez-Diaz et al., 2013). Equally, both wt-p53 and mutp53 regulate the TGF-β-mediated human lung and breast EMT by affecting TGF-β/SMAD3-mediated signaling. By restricting the expression of Nox4, a NADPH oxidase, wt-p53 downregulates downstream focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation to reduce migration. On the contrary, mutp53 has a synergistic effect with TGF-β to upregulate Nox4 and promotes tumor cells evasion (Boudreau et al., 2014).

The p53 mutation or deletion upregulates immunosuppressive ligands

Immunosuppressive ligands, also known as immune checkpoints, such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4), have attracted much attention since their discoverers won the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Immune Checkpoints are inhibitory pathways to maintain the persistence of immune response and the stability of the internal environment based on self-tolerance (Abril-Rodriguez and Ribas, 2017). Currently, there are several immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) proved by FDA for clinical treatment. The representative examples are ipilimumab for metastatic melanoma (Langer et al., 2007; Kirkwood et al., 2008; Weber et al., 2008), nivolumab for non-small cell lung cancer (Topalian et al., 2012; Hellmann et al., 2019; Forde et al., 2022) and avelumab for urothelial carcinoma (Powles et al., 2020; Powles et al., 2021). However, immune therapy still has limits. A large fraction of patients has no response to immune therapy and many patients responding develop drug resistance after several treatment cycles (Chowdhury et al., 2018). Understanding the intrinsic mechanisms of immune checkpoints expression can therefore deepen our understanding of tumor immune escape and help develop new treatment options.

It is discovered that PD-L1, PD-L2, and CTLA-4 expression is significantly increased in patients with TP53 mutations in both clinical samples and mouse models of hematologic neoplasms (Pascual et al., 2019; Sallman et al., 2020). Similar findings have been discovered in solid tumors (Thiem et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020). Furthermore, other co-inhibitory receptors, such as PD-1, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM3), and lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3) are co-expressed on tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cells (Williams et al., 2019). Based on these specific subtypes of T cells and tumor cells, TP53 mutations are one of the indicators in predicting efficacy in patients treated with ICIs (Chen et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020).

PD-L1 expression is regulated by multiple pathways. The gain-of-function mutant p53 upregulated IL-17 signaling and induced the transformation of infiltrating T cells into exhausted CD8+ T cells to counteract the effects of PD-1 inhibitors (Wang J. et al., 2021). Besides, PD-L1 expression is upregulated by IFN-γ induced immune response, and both wt- and mut-p53 work in this process. It isn’t the activity, but the expression level of p53 or mutp53 impacts PD-L1 expression activated by IFN-γ (Thiem et al., 2019). The non-coding RNA miR-34, transcriptionally induced by p53, is also proved to negatively regulate PD-L1 (Cortez et al., 2016). In addition, p53 transcriptionally induces the expression of PTEN gene, an inhibitor of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, which downregulates PD-L1 and maintains immune response (Hays and Bonavida, 2019). For the p53 deletion losing inhibition of PD-L1, it is conducive to tumor immune evasion.

The p53 mutation or deletion promotes immunosuppressive cells differentiation

Tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) refers to immunological components with tumors (Fu et al., 2021). Various immune cells are the major participators of immune response. Notably, patients with TP53 mutations display non-T cell infiltrated phenotype. The numbers of cytotoxic T cells, helper T cells, as well as NK cells significantly reduced. Meanwhile, highly immunosuppressive Tregs (Sallman et al., 2020) and M2 macrophages (Wang et al., 2021) are expanded in cases with TP53 mutations.

Some indirect evidence suggests different status of p53 impact the intensity of immune response. The adaptive immune response is enhanced in the mouse model of colon cancer treated with HDM201, a selective MDM2 inhibitor. After the HDM201 treatment, the percentage of DC cells and CD8+ T cells increased in a p53-dependent manner (Wang et al., 2021). Moreover, p53 activation combined with immune checkpoint blockade therapy has been found to make breakthroughs in a variety of tumors. Studies in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) demonstrated the number of infiltrating CD8+ T cells and the fraction of activated CD8+ T cells is significantly increased after the combination therapy (Xiao et al., 2022).

Tregs are the major suppressive cells in controlling immune tolerance and homeostasis of immune system. Tregs are considered as tumor-promoting cells (Ye et al., 2012) because of suppressing anti-tumor Teffs response by releasing inhibitory cytokines such as IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-35 (Li et al., 2020). The relationship between Tregs and p53 is complex. Patients treated with p53 vaccination displayed decreased frequencies of Tregs and the 2-year disease-free survival reached 88% (Schuler et al., 2014). High doses of p53-derived peptide inhibited the Tregs differentiation and immunosuppressive function in vitro (Mandapathil et al., 2013). However, a research found the lack of p53 in rheumatoid arthritis compromised Tregs differentiation because of the decreasing activity of STAT-5 (Park et al., 2013). Depletion of highly activated and strongly suppressive tumor-infiltrating Tregs contributes to clinical outcomes of immunotherapy (Van Damme et al., 2021). These phenomena suggest that wt-p53 in the normal state promotes Tregs differentiation to control immune response, but under the tumor environment, p53 tends to suppress Tregs action to limit tumors.

The suppressive effects in Tregs cells is mainly dependent on the expression and function of the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (Foxp3) (Ohkura and Sakaguchi, 2020). Further, the lineage stability of Tregs is closely related to the PI3K/Akt pathway and its suppressor PTEN (Huynh et al., 2015). As is mentioned above, the lack of p53 consequently promotes the accumulation of inactivated PTEN, thus activating PI3K/Akt signaling and the Tregs differentiation (Kang et al., 2017). Foxp3 also can be regulated by miR-149-39. A study in esophageal cancer found long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3) upregulates MDM2, the inhibitor of p53. The decreased p53 is unable to generate sufficient miR-149-3p to limit transcription of Foxp3, but upregulate Tregs (Xu et al., 2021).

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) is another important member of the suppressive immune microenvironment, which produces reactive oxygen species and other cytokines to inhibit T cell mediated immune response (Li et al., 2021). p53 mediates the quantity and quality of MDSC in TIME. The p53 deletion enhanced the recruitment of suppressive myeloid CD11b+ cells through upregulating the expression of CXCR3/CCR2-associated chemokines and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (Blagih et al., 2020). The destabilizing p53 prevents MDSCs from ferroptosis through upregulating Heme Oxygenase-1 (Hmox1) expression to suppress lipid reactive oxygen species production (Zhu et al., 2021). The dysfunctional p53 promotes the expansion of lymphoid-like stromal network, which increased the expression of CXCL1, CCL3, and CCL21 to recruit more immunosuppressive populations, especially MDSCs (Guo et al., 2013).

TAMs are major tumor-infiltrating cells mediated a variety of cellular activities such as tumor cytotoxicity (Chen et al., 2018), angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis (Volk-Draper et al., 2019). TAMs can be simply divided into tumor killing M1 type and tumor promoting M2 type based on their response to tumors. The transform mechanism between M1 and M2 that remains a mystery is a research hotspot, and p53 plays a role in the process. As mentioned above, the co-expression of p53 and NF-κB in TAMs promotes the secretion of IL-6 and CXCL-1 to promote tumor cell survival (Lowe et al., 2014). Tumor cells lack p53 also release WNT ligands to stimulate TAMs to produce IL-1β. The IL-1β triggers an inflammatory cascade throughout the body and drives tumor metastasis (Wellenstein et al., 2019). In macrophages, p53 acetylation induced M1 polarization to maintain iron homeostasis (Zhou et al., 2018). In vitro co-cultures of M0 macrophages with H358 (a p53-null cell line) exosomes demonstrated that exosome-induced M2 polarization may be p53 independent (Pritchard et al., 2020). Besides, upregulated wt-p53 altered miRNA levels in the exosomes and promoted macrophage repolarization towards a more pro-inflammatory/antitumor M1 phenotype (Trivedi et al., 2016). Equally, TAMs will affect p53 during the response. The expression of VEGF-C and its receptor VEGFR3 promoted by TAMs results in the loss of p53 and PTEN in tumor cells, which contributes to tumor resistance (Li et al., 2017).

Target p53: New therapeutic strategies for immunotherapy

In recent years, immunotherapy including ICIs, cancer vaccination, and adoptive cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of cancer. As introduced above, the p53 mutation or deletion play a central role in tumor immune evasion, so reactivating wt-p53 or restoring tumor suppressive function of mutp53 are promising anti-tumor immunotherapy strategies.

Scientists has appreciated the antigenic character of p53 since 1990s and developed p53-based vaccines (DeLeo and Appella, 2020). A novel phase Ib clinical trial of adjuvant p53 peptide-loaded DC cells demonstrated that the DC–p53 vaccine triggered a p53-specific immune response in 11 patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, out of the 16 patients treated (Schuler et al., 2014). In another phase I trial, patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer received a combination regimen of a Modified Vaccinia Ankara vaccine delivering wild-type human p53 (p53MVA) and gemcitabine chemotherapy. It is found that p53MVA could elevate p53-reactive CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses, and patients with greatest expansion of T cells had longer progression-free survival (PFS) (Hardwick et al., 2018). Moreover, restoring p53 expression by p53 mRNA nanomedicine (Xiao et al., 2022) or directly introducing wt-p53 gene could reprogram the TME and sensitize tumors to anti-PD-1 therapy in mice experiments (Kim et al., 2019).

Targeting p53-MDM2 pathway is another strategy. Combination of reactivation of wt-p53 and ICIs is also proved to have a better anti-tumor effect. Wang and co-workers demonstrated that HDM201, a potent and selective second-generation MDM2 inhibitor, could trigger adaptive immunity and develop durable, antigen-specific memory T cells in a p53-dependent manner. Combination of HDM201 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade is more efficient for complete tumor regressions (Wang et al., 2021). Similarly, Fang et al. (2019) also discovered that p53 activation by APG-115 would reduce the number and proportion of immunosuppressive M2 macrophage and has a synergistic effect with PD-1 blockade in anti-tumor.

It isn’t difficult to find from the previous studies that p53 has a strong connection with TIME (Hassin and Oren, 2022). The p53 mutation and deletion in tumor cells trends to form a tumor promoting microenvironment. Growing evidence indicated that p53 could be an effective target to deal with immune evasion.

Concluding remarks

p53 is a star molecular which mediates multiple cellular activities of tumors and attracts much attention since its discovery. Scientists gradually realized the better treatment is to recover normal immune response, not only to enhance immune response. Owing to the essential role of p53 mutation and deletion in tumor immune evasion, reactivation of expression and function of p53 to reshape TIME and restore anti-tumor immunity may be efficient treatment for anti-tumor. Although scientists have spent almost 30 years to develop p53-based therapies, p53 is still a mystery protein attracting our attention. Great expectations of targeting p53 and unstable efficacy urge us to have a deeper understanding of it.

Author contributions

RY and HQG designed the study. SYL and TYL wrote and edited the manuscript. JXJ and SYL drew the figures. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82172691, 81772727 and 81772710) and Nanjing Science and Technology Development Key Project (YKK19011).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abril-Rodriguez, G., and Ribas, A. (2017). SnapShot: Immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Cell 31 (6), 848–848.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2017.05.010

Adriaens, C., Standaert, L., Barra, J., Latil, M., Verfaillie, A., Kalev, P., et al. (2016). p53 induces formation of NEAT1 lncRNA-containing paraspeckles that modulate replication stress response and chemosensitivity. Nat. Med. 22 (8), 861–868. doi:10.1038/nm.4135

Aubrey, B. J., Kelly, G. L., Janic, A., Herold, M. J., and Strasser, A. (2018). How does p53 induce apoptosis and how does this relate to p53-mediated tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ. 25 (1), 104–113. doi:10.1038/cdd.2017.169

Balka, K. R., Louis, C., Saunders, T. L., Smith, A. M., Calleja, D. J., D'Silva, D. B., et al. (2020). TBK1 and IKKε act redundantly to mediate STING-induced NF-κB responses in myeloid cells. Cell Rep. 31 (1), 107492. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.056

Batlle, E., and Massague, J. (2019). Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in immunity and cancer. Immunity 50 (4), 924–940. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.024

Bi, K., He, M. X., Bakouny, Z., Kanodia, A., Napolitano, S., Wu, J., et al. (2021). Tumor and immune reprogramming during immunotherapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 39 (5), 649–661.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2021.02.015

Blagih, J., Zani, F., Chakravarty, P., Hennequart, M., Pilley, S., Hobor, S., et al. (2020). Cancer-specific loss of p53 leads to a modulation of myeloid and T cell responses. Cell Rep. 30 (2), 481–496.e6. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.028

Borish, L. C., and Steinke, J. W. (2003). 2. Cytokines and chemokines. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111, S460–S475. doi:10.1067/mai.2003.108

Bottcher, J. P., Bonavita, E., Chakravarty, P., Blees, H., Cabeza-Cabrerizo, M., Sammicheli, S., et al. (2018). NK cells stimulate recruitment of cDC1 into the tumor microenvironment promoting cancer immune control. Cell 172 (5), 1022–1037.e14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.004

Boudreau, H. E., Casterline, B. W., Burke, D. J., and Leto, T. L. (2014). Wild-type and mutant p53 differentially regulate NADPH oxidase 4 in TGF-beta-mediated migration of human lung and breast epithelial cells. Br. J. Cancer 110 (10), 2569–2582. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.165

Boutelle, A. M., and Attardi, L. D. (2021). p53 and tumor suppression: It takes a network. Trends Cell Biol. 31 (4), 298–310. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2020.12.011

Bubeník, J. (2004). MHC class I down-regulation: Tumour escape from immune surveillance? (review). Int. J. Oncol. 25 (2), 487–491. doi:10.3892/ijo.25.2.487

Cao, L., Huang, C., Cui Zhou, D., Hu, Y., Lih, T. M., Savage, S. R., et al. (2021). Proteogenomic characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell 184 (19), 5031–5052.e26. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.023

Chen, D. S., and Mellman, I. (2017). Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature 541 (7637), 321–330. doi:10.1038/nature21349

Chen, D., Xie, J., Fiskesund, R., Dong, W., Liang, X., Lv, J., et al. (2018). Chloroquine modulates antitumor immune response by resetting tumor-associated macrophages toward M1 phenotype. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 873. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03225-9

Chen, Y., Chen, G., Li, J., Huang, Y. Y., Li, Y., Lin, J., et al. (2019). Association of tumor protein p53 and ataxia-telangiectasia mutated comutation with response to immune checkpoint inhibitors and mortality in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2 (9), e1911895. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11895

Chen, Y. J., and Roumeliotis, T. I. (2020). Proteogenomics of non-smoking lung cancer in east asia delineates molecular signatures of pathogenesis and progression. Cell 182 (1), 226–244.e17. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.012

Chitlur, M. (2022). Desmopressin revisited in mild hemophilia A. Blood 140 (10), 1063–1064. doi:10.1182/blood.2022017652

Chowdhury, P. S., Chamoto, K., and Honjo, T. (2018). Combination therapy strategies for improving PD-1 blockade efficacy: A new era in cancer immunotherapy. J. Intern Med. 283 (2), 110–120. doi:10.1111/joim.12708

Conlon, K. C., Miljkovic, M. D., and Waldmann, T. A. (2019). Cytokines in the treatment of cancer. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 39 (1), 6–21. doi:10.1089/jir.2018.0019

Corrales, L., Matson, V., Flood, B., Spranger, S., and Gajewski, T. F. (2016). Innate immune signaling and regulation in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 27 (1), 96–108. doi:10.1038/cr.2016.149

Cortez, M. A., Ivan, C., Valdecanas, D., Wang, X., Peltier, H. J., Ye, Y., et al. (2016). PDL1 Regulation by p53 via miR-34. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 108 (1), djv303. doi:10.1093/jnci/djv303

Cresswell, P., Ackerman, A. L., Giodini, A., Peaper, D. R., and Wearsch, P. A. (2005). Mechanisms of MHC class I-restricted antigen processing and cross-presentation. Immunol. Rev. 207, 145–157. doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00316.x

DeLeo, A. B., and Appella, E. (2020). The p53 saga: Early steps in the Development of tumor immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 204 (9), 2321–2328. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1901343

Dixon, S. J., Lemberg, K. M., Lamprecht, M. R., Skouta, R., Zaitsev, E. M., Gleason, C. E., et al. (2012). Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149 (5), 1060–1072. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042

Downward, J., Coppé, J-P., Patil, C. K., Sun, Y., Munoz, D. P., Goldstein, J., et al. (2008). Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 6 (12), 2853–2868. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301

Duong, E., Fessenden, T. B., Lutz, E., Dinter, T., Yim, L., Blatt, S., et al. (2022). Type I interferon activates MHC class I-dressed CD11b(+) conventional dendritic cells to promote protective anti-tumor CD8(+) T cell immunity. Immunity 55 (2), 308–323.e9. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2021.10.020

Engeland, K. (2018). Cell cycle arrest through indirect transcriptional repression by p53: I have a DREAM. Cell Death Differ. 25 (1), 114–132. doi:10.1038/cdd.2017.172

Epping, M. T., and Bernards, R. (2006). A causal role for the human tumor antigen preferentially expressed antigen of melanoma in cancer. Cancer Res. 66 (22), 10639–10642. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2522

Falk, K., and Rötzschke, O. (2002). The final cut: how ERAP1 trims MHC ligands to size. Nat. Immunol. 3, 1121–1122. doi:10.1038/ni1202-1121

Fan, F., Liu, P., Bao, R., Chen, J., Zhou, M., Mo, Z., et al. (2021). A Dual PI3K/HDAC inhibitor induces immunogenic ferroptosis to potentiate cancer immune checkpoint therapy. Cancer Res. 81 (24), 6233–6245. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-1547

Fang, D. D., Tang, Q., Kong, Y., Wang, Q., Gu, J., Fang, X., et al. (2019). MDM2 inhibitor APG-115 synergizes with PD-1 blockade through enhancing antitumor immunity in the tumor microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 7 (1), 327. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0750-6

Flutter, B., and Gao, B. (2004). MHC class I antigen presentation-recently trimmed and well presented. Cell Mol. Immunol. 1 (1), 22–30.

Forde, P. M., Spicer, J., Lu, S., Provencio, M., Mitsudomi, T., Awad, M. M., et al. (2022). Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386 (21), 1973–1985. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2202170

Fu, T., Dai, L. J., Wu, S. Y., Xiao, Y., Ma, D., Jiang, Y. Z., et al. (2021). Spatial architecture of the immune microenvironment orchestrates tumor immunity and therapeutic response. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14 (1), 98. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01103-4

Gaillard, H., Garcia-Muse, T., and Aguilera, A. (2015). Replication stress and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15 (5), 276–289. doi:10.1038/nrc3916

Ghosh, M., Saha, S., Bettke, J., Nagar, R., Parrales, A., Iwakuma, T., et al. (2021). Mutant p53 suppresses innate immune signaling to promote tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 39 (4), 494–508.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2021.01.003

Gillette, M. A., Satpathy, S., Cao, S., Dhanasekaran, S. M., Vasaikar, S. V., Krug, K., et al. (2020). Proteogenomic characterization reveals therapeutic vulnerabilities in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell 182 (1), 200–225.e35. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.013

Guinea-Viniegra, J., Zenz, R., Scheuch, H., Jimenez, M., Bakiri, L., Petzelbauer, P., et al. (2012). Differentiation-induced skin cancer suppression by FOS, p53, and TACE/ADAM17. J. Clin. Invest. 122 (8), 2898–2910. doi:10.1172/JCI63103

Guo, G., Marrero, L., Rodriguez, P., Del Valle, L., Ochoa, A., and Cui, Y. (2013). Trp53 inactivation in the tumor microenvironment promotes tumor progression by expanding the immunosuppressive lymphoid-like stromal network. Cancer Res. 73 (6), 1668–1675. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3810

Hafner, A., Bulyk, M. L., Jambhekar, A., and Lahav, G. (2019). The multiple mechanisms that regulate p53 activity and cell fate. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20 (4), 199–210. doi:10.1038/s41580-019-0110-x

Hanahan, D., and Weinberg, R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 144 (5), 646–674. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

Hardwick, N. R., Frankel, P., Ruel, C., Kilpatrick, J., Tsai, W., Kos, F., et al. (2018). p53-Reactive T cells are associated with clinical benefit in patients with platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer after treatment with a p53 vaccine and gemcitabine chemotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 24 (6), 1315–1325. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2709

Harris, C. C. (1995). 1995 deichmann lecture-p53 tumor suppressor gene: At the crossroads of molecular carcinogenesis, molecular epidemiology and cancer risk assessment. Toxicol. Lett. 82-83, 1–7. doi:10.1016/0378-4274(95)03643-1

Hassin, O., and Oren, M. (2022). Drugging p53 in cancer: one protein, many targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 127–144. doi:10.1038/s41573-022-00571-8

Haupt, Y., Maya, R., Kazaz, A., and Oren, M. (1997). Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature 387 (6630), 296–299. doi:10.1038/387296a0

Hays, E., and Bonavida, B. (2019). YY1 regulates cancer cell immune resistance by modulating PD-L1 expression. Drug Resist. Updat. 43, 10–28. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2019.04.001

Hellmann, M. D., Paz-Ares, L., Bernabe Caro, R., Zurawski, B., Kim, S. W., Carcereny Costa, E., et al. (2019). Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 381 (21), 2020–2031. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1910231

Ho, J. N. H. G., Schmidt, D., Lowinus, T., Ryoo, J., Dopfer, E. P., Gonzalo Nunez, N., et al. (2022). Targeting MDM2 enhances antileukemia immunity after allogeneic transplantation via MHC-II and TRAIL-R1/2 upregulation. Blood 140 (10), 1167–1181. doi:10.1182/blood.2022016082

Huynh, A., DuPage, M., Priyadharshini, B., Sage, P. T., Quiros, J., Borges, C. M., et al. (2015). Control of PI(3) kinase in Treg cells maintains homeostasis and lineage stability. Nat. Immunol. 16 (2), 188–196. doi:10.1038/ni.3077

Jhunjhunwala, S., Hammer, C., and Delamarre, L. (2021). Antigen presentation in cancer: insights into tumour immunogenicity and immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21 (5), 298–312. doi:10.1038/s41568-021-00339-z

Jiang, L., Kon, N., Li, T., Wang, S. J., Su, T., Hibshoosh, H., et al. (2015). Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 520 (7545), 57–62. doi:10.1038/nature14344

Kang, Y. J., Balter, B., Csizmadia, E., Haas, B., Sharma, H., Bronson, R., et al. (2017). Contribution of classical end-joining to PTEN inactivation in p53-mediated glioblastoma formation and drug-resistant survival. Nat. Commun. 8, 14013. doi:10.1038/ncomms14013

Keast, D. (1970). Immunosurveillance and cancer. Lancet 2 (7675), 710–712. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(70)91973-2

Kim, S. S., Harford, J. B., Moghe, M., Slaughter, T., Doherty, C., and Chang, E. H. (2019). A tumor-targeting nanomedicine carrying the p53 gene crosses the blood-brain barrier and enhances anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in mouse models of glioblastoma. Int. J. Cancer 145 (9), 2535–2546. doi:10.1002/ijc.32531

Kirkwood, J. M., Tarhini, A. A., Panelli, M. C., Moschos, S. J., Zarour, H. M., Butterfield, L. H., et al. (2008). Next generation of immunotherapy for melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (20), 3445–3455. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6423

Krenz, B., Gebhardt-Wolf, A., Ade, C. P., Gaballa, A., Roehrig, F., Vendelova, E., et al. (2021). MYC- and MIZ1-Dependent vesicular transport of Double-strand RNA controls immune evasion in pancreatic Ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 81 (16), 4242–4256. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-1677

Kubbutat, M. H., Jones, S. N., and Vousden, K. H. (1997). Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature 387 (6630), 299–303. doi:10.1038/387299a0

Langer, L. F., Clay, T. M., and Morse, M. A. (2007). Update on anti-CTLA-4 antibodies in clinical trials. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 7 (8), 1245–1256. doi:10.1517/14712598.7.8.1245

Li, Y., Weng, Y., Zhong, L., Chong, H., Chen, S., Sun, Y., et al. (2017). VEGFR3 inhibition chemosensitizes lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells in the tumor-associated macrophage microenvironment through upregulation of p53 and PTEN. Oncol. Rep. 38 (5), 2761–2773. doi:10.3892/or.2017.5969

Li, C., Jiang, P., Wei, S., Xu, X., and Wang, J. (2020). Regulatory T cells in tumor microenvironment: new mechanisms, potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Mol. Cancer 19 (1), 116. doi:10.1186/s12943-020-01234-1

Li, T., Liu, T., Zhu, W., Xie, S., Zhao, Z., Feng, B., et al. (2021). Targeting MDSC for immune-checkpoint blockade in cancer immunotherapy: Current progress and new prospects. Clin. Med. Insights Oncol. 15, 11795549211035540. doi:10.1177/11795549211035540

Liao, P., Zeng, S. X., Zhou, X., Chen, T., Zhou, F., Cao, B., et al. (2017). Mutant p53 gains its function via c-myc activation upon CDK4 phosphorylation at serine 249 and consequent PIN1 binding. Mol. Cell 68 (6), 1134–1146.e6. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2017.11.006

Lindstrom, M. S., Bartek, J., and Maya-Mendoza, A. (2022). p53 at the crossroad of DNA replication and ribosome biogenesis stress pathways. Cell Death Differ. 29 (5), 972–982. doi:10.1038/s41418-022-00999-w

Liu, Y., and Gu, W. (2021). The complexity of p53-mediated metabolic regulation in tumor suppression. Seminars Cancer Biol. 85, 4–32. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.03.010

Liu, Y., and Gu, W. (2022). p53 in ferroptosis regulation: the new weapon for the old guardian. Cell Death Differ. 29 (5), 895–910. doi:10.1038/s41418-022-00943-y

Liu, Y., Tavana, O., and Gu, W. (2019). p53 modifications: exquisite decorations of the powerful guardian. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 11 (7), 564–577. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjz060

Lopez-Diaz, F. J., Gascard, P., Balakrishnan, S. K., Zhao, J., Del Rincon, S. V., Spruck, C., et al. (2013). Coordinate transcriptional and translational repression of p53 by TGF-β1 impairs the stress response. Mol. Cell 50 (4), 552–564. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.029

Lowe, J. M., Menendez, D., Bushel, P. R., Shatz, M., Kirk, E. L., Troester, M. A., et al. (2014). p53 and NF-κB coregulate proinflammatory gene responses in human macrophages. Cancer Res. 74 (8), 2182–2192. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1070

Mandapathil, M., Visus, C., Finn, O. J., Lang, S., and Whiteside, T. L. (2013). Generation and immunosuppressive functions of p53-induced human adaptive regulatory T cells. Oncoimmunology 2 (7), e25514. doi:10.4161/onci.25514

Muller, P. A., and Vousden, K. H. (2013). p53 mutations in cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 15 (1), 2–8. doi:10.1038/ncb2641

Muller, P. A., and Vousden, K. H. (2014). Mutant p53 in cancer: new functions and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Cell 25 (3), 304–317. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.021

Negrini, S., Gorgoulis, V. G., and Halazonetis, T. D. (2010). Genomic instability-an evolving hallmark of cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11 (3), 220–228. doi:10.1038/nrm2858

Ohkura, N., and Sakaguchi, S. (2020). Transcriptional and epigenetic basis of treg cell development and function: its genetic anomalies or variations in autoimmune diseases. Cell Res. 30 (6), 465–474. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0324-7

Olivero, C. E., Martinez-Terroba, E., Zimmer, J., Liao, C., Tesfaye, E., Hooshdaran, N., et al. (2020). p53 activates the long noncoding RNA Pvt1b to inhibit Myc and suppress tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell 77 (4), 761–774.e8. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.014

Ottaviani, S., Stebbing, J., Frampton, A. E., Zagorac, S., Krell, J., de Giorgio, A., et al. (2018). TGF-beta induces miR-100 and miR-125b but blocks let-7a through LIN28B controlling PDAC progression. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 1845. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03962-x

Park, J. S., Lim, M. A., Cho, M. L., Ryu, J. G., Moon, Y. M., Jhun, J. Y., et al. (2013). p53 controls autoimmune arthritis via STAT-mediated regulation of the Th17 cell/Treg cell balance in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 65 (4), 949–959. doi:10.1002/art.37841

Pascual, M., Mena-Varas, M., Robles, E. F., Garcia-Barchino, M. J., Panizo, C., Hervas-Stubbs, S., et al. (2019). PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint and p53 loss facilitate tumor progression in activated B-cell diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood 133 (22), 2401–2412. doi:10.1182/blood.2018889931

Powles, T., Park, S. H., Voog, E., Caserta, C., Valderrama, B. P., Gurney, H., et al. (2020). Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 383 (13), 1218–1230. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2002788

Powles, T., Sridhar, S. S., Loriot, Y., Bellmunt, J., Mu, X. J., Ching, K. A., et al. (2021). Avelumab maintenance in advanced urothelial carcinoma: biomarker analysis of the phase 3 JAVELIN bladder 100 trial. Nat. Med. 27 (12), 2200–2211. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01579-0

Pritchard, A., Tousif, S., Wang, Y., Hough, K., Khan, S., Strenkowski, J., et al. (2020). Lung tumor cell-Derived exosomes promote M2 macrophage polarization. Cells 9 (5), 1303. doi:10.3390/cells9051303

Propper, D. J., and Balkwill, F. R. (2022). Harnessing cytokines and chemokines for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19 (4), 237–253. doi:10.1038/s41571-021-00588-9

Reeves, E., Islam, Y., and James, E. (2020). ERAP1: A potential therapeutic target for a myriad of diseases. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 24 (6), 535–544. doi:10.1080/14728222.2020.1751821

Rokavec, M., Oner, M. G., Li, H., Jackstadt, R., Jiang, L., Lodygin, D., et al. (2014). IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a feedback loop promotes EMT-mediated colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis. J. Clin. Invest. 124 (4), 1853–1867. doi:10.1172/JCI73531

Salazar-Onfray, F., Lopez, M. N., and Mendoza-Naranjo, A. (2007). Paradoxical effects of cytokines in tumor immune surveillance and tumor immune escape. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 18 (1-2), 171–182. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.01.015

Sallman, D. A., McLemore, A. F., Aldrich, A. L., Komrokji, R. S., McGraw, K. L., Dhawan, A., et al. (2020). TP53 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes and secondary AML confer an immunosuppressive phenotype. Blood 136 (24), 2812–2823. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006158

Schuler, P. J., Harasymczuk, M., Visus, C., Deleo, A., Trivedi, S., Lei, Y., et al. (2014). Phase I dendritic cell p53 peptide vaccine for head and neck cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 20 (9), 2433–2444. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2617

Shamalov, K., Levy, S. N., Horovitz-Fried, M., and Cohen, C. J. (2017). The mutational status of p53 can influence its recognition by human T-cells. Oncoimmunology 6 (4), e1285990. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2017.1285990

Shieh, S. Y., Ikeda, M., Taya, Y., and Prives, C. (1997). DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell 91 (3), 325–334. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80416-x

Sun, H., Liu, S. Y., Zhou, J. Y., Xu, J. T., Zhang, H. K., Yan, H. H., et al. (2020). Specific TP53 subtype as biomarker for immune checkpoint inhibitors in lung adenocarcinoma. EBioMedicine 60, 102990. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102990

Sun, Y. F., Wu, L., Liu, S. P., Jiang, M. M., Hu, B., Zhou, K. Q., et al. (2021). Dissecting spatial heterogeneity and the immune-evasion mechanism of CTCs by single-cell RNA-seq in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 4091. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24386-0

Thiem, A., Hesbacher, S., Kneitz, H., di Primio, T., Heppt, M. V., Hermanns, H. M., et al. (2019). IFN-gamma-induced PD-L1 expression in melanoma depends on p53 expression. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38 (1), 397. doi:10.1186/s13046-019-1403-9

Topalian, S. L., Hodi, F. S., Brahmer, J. R., Gettinger, S. N., Smith, D. C., McDermott, D. F., et al. (2012). Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 366 (26), 2443–2454. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1200690

Trivedi, M., Talekar, M., Shah, P., Ouyang, Q., and Amiji, M. (2016). Modification of tumor cell exosome content by transfection with wt-p53 and microRNA-125b expressing plasmid DNA and its effect on macrophage polarization. Oncogenesis 5 (8), e250. doi:10.1038/oncsis.2016.52

Van Damme, H., Dombrecht, B., Kiss, M., Roose, H., Allen, E., Van Overmeire, E., et al. (2021). Therapeutic depletion of CCR8(+) tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells elicits antitumor immunity and synergizes with anti-PD-1 therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 9 (2), e001749. doi:10.1136/jitc-2020-001749

Ventura, A., Kirsch, D. G., McLaughlin, M. E., Tuveson, D. A., Grimm, J., Lintault, L., et al. (2007). Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature 445 (7128), 661–665. doi:10.1038/nature05541

Volk-Draper, L., Patel, R., Bhattarai, N., Yang, J., Wilber, A., DeNardo, D., et al. (2019). Myeloid-Derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors significantly contribute to lymphatic metastasis in clinical breast cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 189 (11), 2269–2292. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.07.006

Wang, B., Niu, D., Lai, L., and Ren, E. C. (2013). p53 increases MHC class I expression by upregulating the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase ERAP1. Nat. Commun. 4, 2359. doi:10.1038/ncomms3359

Wang, H. Q., Mulford, I. J., Sharp, F., Liang, J., Kurtulus, S., Trabucco, G., et al. (2021). Inhibition of MDM2 promotes antitumor responses in p53 wild-type cancer cells through their interaction with the immune and stromal microenvironment. Cancer Res. 81 (11), 3079–3091. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-0189

Wang, J., Hu, Y., Escamilla-Rivera, V., Gonzalez, C. L., Tang, L., Wang, B., et al. (2021). Epithelial mutant p53 promotes resistance to anti-PD-1-mediated oral cancer immunoprevention in carcinogen-induced mouse models. Cancers (Basel) 13 (6), 1471. doi:10.3390/cancers13061471

Weber, J. S., O'Day, S., Urba, W., Powderly, J., Nichol, G., Yellin, M., et al. (2008). Phase I/II study of ipilimumab for patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (36), 5950–5956. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1927

Wellenstein, M. D., Coffelt, S. B., Duits, D. E. M., van Miltenburg, M. H., Slagter, M., de Rink, I., et al. (2019). Loss of p53 triggers WNT-dependent systemic inflammation to drive breast cancer metastasis. Nature 572 (7770), 538–542. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1450-6

Willenbrink, T. J., Ruiz, E. S., Cornejo, C. M., Schmults, C. D., Arron, S. T., and Jambusaria-Pahlajani, A. (2020). Field cancerization: Definition, epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 83 (3), 709–717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.126

Williams, P., Basu, S., Garcia-Manero, G., Hourigan, C. S., Oetjen, K. A., Cortes, J. E., et al. (2019). The distribution of T-cell subsets and the expression of immune checkpoint receptors and ligands in patients with newly diagnosed and relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 125 (9), 1470–1481. doi:10.1002/cncr.31896

Woo, S. R., Corrales, L., and Gajewski, T. F. (2015). Innate immune recognition of cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 33, 445–474. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112043

Xiao, Y., Chen, J., Zhou, H., Zeng, X., Ruan, Z., Pu, Z., et al. (2022). Combining p53 mRNA nanotherapy with immune checkpoint blockade reprograms the immune microenvironment for effective cancer therapy. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 758. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28279-8

Xu, Q. R., Tang, J., Liao, H. Y., Yu, B. T., He, X. Y., Zheng, Y. Z., et al. (2021). Long non-coding RNA MEG3 mediates the miR-149-3p/FOXP3 axis by reducing p53 ubiquitination to exert a suppressive effect on regulatory T cell differentiation and immune escape in esophageal cancer. J. Transl. Med. 19 (1), 264. doi:10.1186/s12967-021-02907-1

Xu, N., Yao, Z., Shang, G., Ye, D., Wang, H., Zhang, H., et al. (2022). Integrated proteogenomic characterization of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. J. Hematol. Oncol. 15 (1), 76. doi:10.1186/s13045-022-01291-7

Xue, W., Zender, L., Miething, C., Dickins, R. A., Hernando, E., Krizhanovsky, V., et al. (2007). Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature 445 (7128), 656–660. doi:10.1038/nature05529

Yang, L., Pang, Y., and Moses, H. L. (2010). TGF-beta and immune cells: An important regulatory axis in the tumor microenvironment and progression. Trends Immunol. 31 (6), 220–227. doi:10.1016/j.it.2010.04.002

Ye, J., Huang, X., Hsueh, E. C., Zhang, Q., Ma, C., Zhang, Y., et al. (2012). Human regulatory T cells induce T-lymphocyte senescence. Blood 120 (10), 2021–2031. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-03-416040

Yi, M., Zhang, J., Li, A., Niu, M., Yan, Y., Jiao, Y., et al. (2021). The construction, expression, and enhanced anti-tumor activity of YM101: A bispecific antibody simultaneously targeting TGF-β and PD-L1. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14 (1), 27. doi:10.1186/s13045-021-01045-x

Zeng, L., Rowland, R. G., Lele, S. M., and Kyprianou, N. (2004). Apoptosis incidence and protein expression of p53, TGF-beta receptor II, p27Kip1, and Smad4 in benign, premalignant, and malignant human prostate. Hum. Pathol. 35 (3), 290–297. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2003.11.001

Zhou, Y., Que, K. T., Zhang, Z., Yi, Z. J., Zhao, P. X., You, Y., et al. (2018). Iron overloaded polarizes macrophage to proinflammation phenotype through ROS/acetyl-p53 pathway. Cancer Med. 7 (8), 4012–4022. doi:10.1002/cam4.1670

Zhou, X., Singh, M., Sanz Santos, G., Guerlavais, V., Carvajal, L. A., Aivado, M., et al. (2021). Pharmacologic activation of p53 triggers viral mimicry response thereby abolishing tumor immune evasion and promoting antitumor immunity. Cancer Discov. 11 (12), 3090–3105. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1741

Zhu, K., Wang, J., Zhu, J., Jiang, J., Shou, J., and Chen, X. (1999). p53 induces TAP1 and enhances the transport of MHC class I peptides. Oncogene 18 (54), 7740–7747. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203235

Zhu, H., Klement, J. D., Lu, C., Redd, P. S., Yang, D., Smith, A. D., et al. (2021). Asah2 represses the p53-hmox1 Axis to protect myeloid-Derived suppressor cells from ferroptosis. J. Immunol. 206 (6), 1395–1404. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.2000500

Glossary

NK cell Natural killer cell

DC cell Dendritic cell

Mutp53 Mutant p53

Wt-p53 Wild-type p53

MHC Major histocompatibility complex

TAP Transporter associated with antigen processing

ERAP1 Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1

Myc Myelocytomatosis

TLR3 Toll-like receptor 3

ERV Endogenous retroviruses

IFN Interferon

STAT Signal transducer and activator of transcription

TCR T cell receptor

TNF Tumor necrosis factor

AML Acute myeloid leukemia

TRAIL-R1/2 Tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 1 and receptor 2

ISGs IFN-stimulated genes

STING Stimulator of IFN genes

IRF3 IFN regulatory factor 3

TBK1 TANK binding protein kinase 1

IL-6 Interleukin-6

EMT Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

TAMs Tumor accosicated macrophages

TGF-β Transforming growth factor-β

Teffs Effector T cells

Tregs Regulatory T cells

E2F-4 Viral E2-associated factor 4

PD-1 Programmed cell death protein 1

CTLA-4 Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4

ICIs Immune checkpoint inhibitors

TIM3 T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3

LAG3 Lymphocyte-activation gene 3

TIME Tumor immune microenvironment

Foxp3 Factor forkhead box P3

LncRNA Long non-coding RNA

MEG3 Maternally expressed gene 3

MDSC Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

M-CSF Macrophage colony-stimulating factor

Hmox1 Heme oxygenase-1

p53MVA Modified vaccinia ankara vaccine delivering wild-type human p53

PFS Progression-free survival.

Keywords: p53 mutation, p53 deletion, tumor immune evasion, tumor immune microenvironment, MHC

Citation: Liu S, Liu T, Jiang J, Guo H and Yang R (2023) p53 mutation and deletion contribute to tumor immune evasion. Front. Genet. 14:1088455. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1088455

Received: 03 November 2022; Accepted: 11 January 2023;

Published: 20 February 2023.

Edited by:

Jing Zhang, Beihang University, ChinaReviewed by:

Qianqian Chen, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, ChinaAnqi Li, The Ohio State University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Liu, Liu, Jiang, Guo and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rong Yang, ZG9jdG9yeXJAZ21haWwuY29t; Hongqian Guo, ZHIuZ2hxQG5qdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Siyang Liu

Siyang Liu Tianyao Liu

Tianyao Liu Jiaxuan Jiang2

Jiaxuan Jiang2 Hongqian Guo

Hongqian Guo Rong Yang

Rong Yang