95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Genet. , 13 December 2022

Sec. Genetics of Common and Rare Diseases

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.1087818

This article is part of the Research Topic Genetics of Female Infertility View all 8 articles

Guoliang Jiang1,2

Guoliang Jiang1,2 Lijun Zou1,2

Lijun Zou1,2 Lingzhi Long1,2

Lingzhi Long1,2 Yijun He1,2

Yijun He1,2 Xin Lv2,3

Xin Lv2,3 Yuanyuan Han2,3

Yuanyuan Han2,3 Tingting Yao1,2

Tingting Yao1,2 Yan Zhang1,2

Yan Zhang1,2 Mao Jiang1,2

Mao Jiang1,2 Zhangzhe Peng2,3

Zhangzhe Peng2,3 Lijian Tao2,3

Lijian Tao2,3 Wei Xie2,4*

Wei Xie2,4* Jie Meng1,2*

Jie Meng1,2*Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that affects the structure and function of motile cilia, leading to classic clinical phenotypes, such as situs inversus, chronic sinusitis, bronchiectasis, repeated pneumonia and infertility. In this study, we diagnosed a female patient with PCD who was born in a consanguineous family through classic clinical manifestations, transmission electron microscopy and immunofluorescence staining. A novel DNAAF4 variant NM_130810: c.1118G>A (p. G373E) was filtered through Whole-exome sequencing. Subsequently, we explored the effect of the mutation on DNAAF4 protein from three aspects: protein expression, stability and interaction with downstream DNAAF2 protein through a series of experiments, such as transfection of plasmids and Co-immunoprecipitation. Finally, we confirmed that the mutation of DNAAF4 lead to PCD by reducing the stability of DNAAF4 protein, but the expression and function of DNAAF4 protein were not affected.

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a heterogeneous genetic disease that follows the law of autosomal recessive inheritance (Goutaki et al., 2016), although X-linked inheritance has also been reported (Moore et al., 2006). PCD, the first discovered and recognized motile ciliary disease, is classified as a ciliary disease with its incidence rate estimated to be 0.0025%–0.0050% worldwide (Goutaki et al., 2016). PCD is more common among consanguineous families (Lie et al., 2010). Patients with PCD often show some classic clinical phenotypes, such as situs inversus, chronic sinusitis, bronchiectasis, repeated pneumonia and infertility (Knowles et al., 2016).

Cilia exist widely in the kingdom of eukaryotes, and the structure of ciliary axoneme is highly conserved in evolution. According to the structure and function, cilia can be divided into three categories: motile cilia, non-motile cilia (also known as primary cilia) and nodal cilia (Antony et al., 2021). Motile cilia are consisted of a central pair microtubules surrounded by nine doublet microtubules in “9 + 2” pattern. Every single doublet has an inner dynein arm and an outer dynein arm which are protein complex consisted of heavy, intermediate and light chains. The head of the heavy chain has ATPase activity, which can drive ciliary oscillation by hydrolyzing ATP (Omran et al., 2008). The respiratory tract, auris media, eustachian tube, paranasal sinus, oviduct, and vessels of the brain are all covered by epithelial cells with multiple motile cilia, which can drive the flow of liquids and the clearance of foreign objects through precise, regular, coordinated and orderly movement (Mitchison and Valente, 2017). Primary cilia, existing almost all types of cells, are composed of “9 + 0” microtubule ultrastructure without dynein proteins and exert the function of signal transduction (Anvarian et al., 2019). Nodal cilia, composed of “9 + 0” microtubule ultrastructure with dynein proteins, are transiently expressed on the ventral surface of the gastrulation during the period of embryonic development, which can rotate clockwise to make the body fluid around the embryo flow leftward. Embryo senses its position through the flow of body fluid so that organs deflect normally (Hirokawa et al., 2006). The etiology of PCD lies in the structural or functional impairment of the motile cilia. Clinical symptoms of PCD patients are consistent with the distribution of motile cilia in the body.

At present, more than 40 genes have been confirmed to be associated with the pathogenesis of PCD (Bhatt and Hogg, 2020), such as DNAAF1, DNAAF2, DNAAF3, DNAAF4, DNAH5, DNAH9, and DNALI1. These genes are involved in the formation of motile cilia. In the case of dynein arms, the IDAs and ODAs need to pre-assembled in the cytoplasm before being transported to the microtubule doublets for assembly by the intraflagellar transport (IFT) (Kozminski et al., 1993; Omran et al., 2008). In this process, dynein axonemal assembly factors play a key role in cytoplasmic pre-assembly steps (Bhatt and Hogg, 2020), including DNAAF1, DNAAF2, DNAAF3, DANNF4, DNAAF5, and LRRC6. Theoretically, any genetic mutation participated in the synthesis, assemble, transport of motile cilia related components could lead to PCD.

In this study, we investigated the clinical and genetic information of a PCD pedigree and further explored the pathogenic mechanism of a novel site mutation in DNAAF4.

DNA extraction kit (QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used to extract genomic DNA (gDNA) from peripheral blood samples of the proband and her family members. Subsequently, the gDNA of proband was sent to Novogene company (Beijing, China) for Whole-exome Sequencing by Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V6 kit (Agilent, California, United States) and Illumina platform. We filterd for SNPs and Indels from sequencing data according to the following requirements: 1) Remove mutations with a population frequency higher than 1% in 1000 Genomes, ESP6500, gnomAD_ALL and gnomAD_EAS databases. 2) remain the variants predicted pathogenic by SIFT, MutationTaster, CADD, Polyphen softwares. 3) Classify the variants according to the American College of Medical Genomics (ACMG) guideline of 2015. The variants in patient family members were validated by sanger sequencing. The primer sequences were designed as follows: Forward Sequence ATTCCTGCTCCTCGCTCTGTTG and Reverse Sequence TGCTCTTCGTGCCTCAGCTTGT.

We analyzed the evolutionary conservation of DNAAF4 protein by comparing the amino acid sequences in different species found from NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

The bronchial ciliary epithelium sample from the proband was fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide at 4°C. Following dehydration, the samples were embedded in epoxy resin.

Ultrathin sections stained with 1% uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate were imaged by HT7700 Hitachi electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and NIKON DS-U3 Digital Sight (NIKON, Tokyo, Japan).

Bronchial ciliary epithelium tissue was obtained by transbronchial lung biopsy. The tissue samples were made into paraffin sections. After being repaired with antigen retrieval solution (PN0012, Pinuofei, China), they were incubated with DNAH9 (PA5-57958, Thermo Fisher, United States), DNAH5 (PA5-45744, Thermo Fisher, United States), DNALI1 (HPA028305, Sigma, United States), anti-acetylated tubulin monoclonal antibody (bsm-33235M, Bioss, China) for 2.5 h and then with secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG, GB22301, Servicebio, China) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, DAPI (C1002, Beyotime, China) was used to stain nuclei. The pictures were collected by a confocal fluorescence microscope (NIKON, Tokyo, Japan).

HEK293T cells were chosen in all cell experiments in this paper. DMEM (Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Servicebio), and environment at 37 °C under humidified 5% CO2 were used to maintain HEK293T cells.

The plasmids including normal and mutant DNAAF4 plasmids with the HA tag fused to the C-terminus and DNAAF2 plasmids with the Flag tag fused to the C-terminus were constructed in Wellbio (Changsha, China). Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) was used for transfection of plasmids according to the instructions. Whole cell extracts were collected for Western blot analysis 48 h after transfection.

After 48 h of transfection, cell protein was extracted through mix with CoIP lysate buffer for 1 h and centrifugation in 7500 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. Subsequently, 20ul of the supernatant was taken as input, and 20 ul Protein G magic beads (Invitrogen) and 2 ul corresponding antibody were added to the other supernatant overnight at 4°C. Then, magnetic beads were washed with CoIP buffer for 5 times and added with 20 ul 2×SDS solution to boil for Western blot analysis.

The cell proteins were extracted with lysate buffer, and then the proteins concentrations were determined by using BCA Protein Assay kit (Sigma). The proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. QuickBlock Blocking Buffer for Western Blot was used to block membranes for 15 min at room temperature. Then, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies, including DNAAF4 (ab229555, Abcam, United Kingdom), Flag (SAB4200071, Sigma) and HA (H6908, sigma), and corresponding secondary antibodies. The target protein bands were visualized by the ECL substrate and analysed by ImageJ software.

The experimental data are all expressed in mean ± standard deviation of at least three independent experiments. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 22.0, IBM, New York, United States). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

The proband (II:2) from a consanguineous family exhibited characteristic clinical manifestations of PCD, including complete situs inversus, chronic sinusitis, bronchiectasis, recurrent bronchitis and pneumonia and infertility (Table 1; Figure 1A). Meanwhile, these symptoms did not occur in her family members. These symptoms are clearly visible on Computed tomography (CT) examination of patient (Figure 1B). Her nasal nitric oxide (nNo) level was 7bpp and pulmonary function test (PFT) revealed severe obstructive ventilatory dysfunction (Table 1). The transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of bronchial ciliary epithelium from the proband showed partial loss of ODAs and IDAs (Figure 1C). Immunofluorescence of bronchial ciliary epithelium showed the existence of composition of ODAs and IDAs (Figures 1D–F). This is consistent with the results of TEM.

FIGURE 1. Pedigree of the family with PCD and the clinical features of the proband from this family. (A) There is one patient (the proband) in the family with PCD. Circles indicate to females. Squares indicate males. Solid symbols indicate patients. Half solid symbols indicate carriers of the identified mutations. The arrow indicates the proband. (B) Chest CT scan of the proband showed complete situs inversus, bronchiectasis and Recurrent bronchitis and pneumonia. (C) The transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of bronchial ciliary epithelium from the proband. The red arrow and the green arrow represent IDAs and ODAs, the black arrow indicates absence of IDAs and ODAs (A–C). A schematic diagram of the bronchial ciliary epithelium cross-section(D). (D–F) Immunofluorescence of bronchial ciliary epithelium revealed the existence of DNAH5, DNAH9 and DNALI1 of proband. Anti-acetylated tubulin monoclonal antibody was used to mark the ciliary axoneme. DNAH5 and DNAH9 were used to label the outer dynein arm (ODA), DNALI1 was used to label the inner dynein arm (IDA).

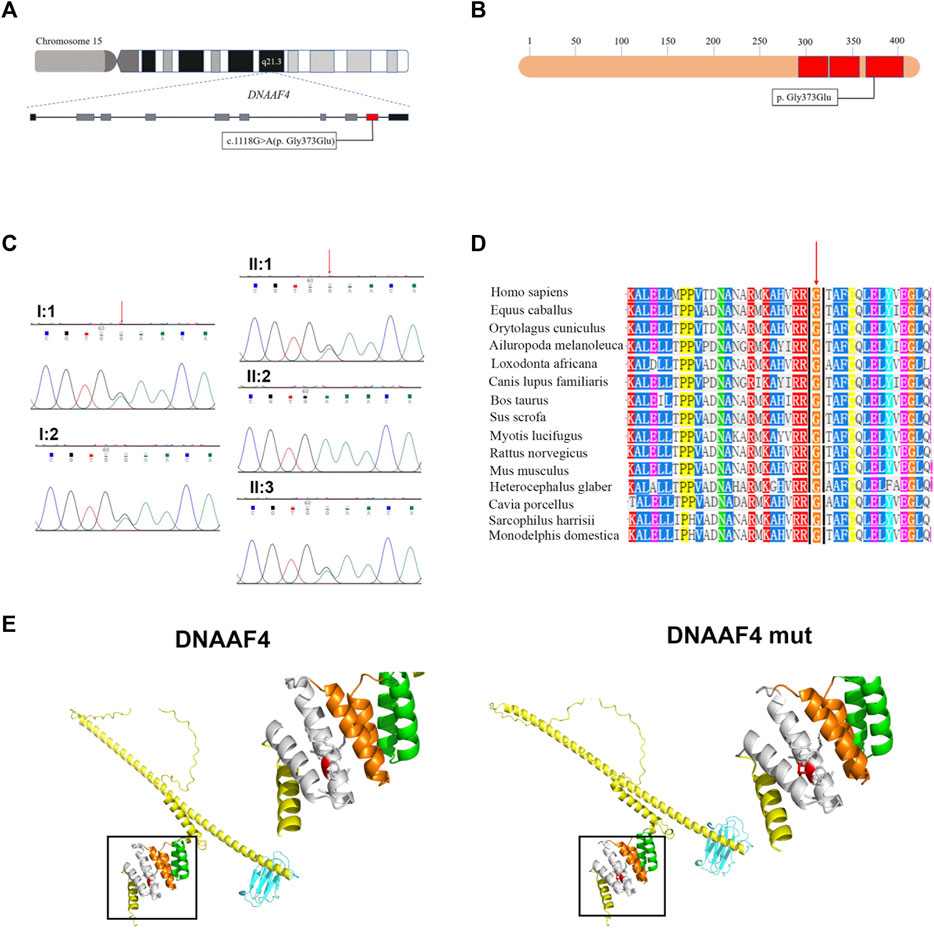

In this study, the blood sample of the proband was performed by whole-exome sequencing (WES). To confirm the accuracy and reliability of the sequencing results, we assessed the quality of the data. The readable genes with coverage depth up to 10× accounted for 99.5% of the reference regions. After filtering SNPs and indels through known databases such as 1000G, dbSNP, YH databases and our inner database, and comparing with currently known PCD causative genes or candidate genes, we identified a homozygous DNAAF4 variant (NM_130810:exon9:c.1118G>A (p. G373E)) (Figure 2A). This is a completely new mutation that has not been reported before, and the population frequency is extremely low. Subsequently, we performed Sanger sequencing on the mutation site in family members of proband (I:1, I:2, II:1, and II:3), and found that her family members were heterozygous for this variant (Figure 2C), which fits the autosomal recessive model (Figure 1A). The mutation was predicted to cause a missense change in amino acid 373 of the entire 420-amino-acid sequence, which is located in the important functional domain of DNAAF4 protein, the C-terminal tetratricopeptide-repeat (TPR) domain (Figure 2B). Then, we analyzed the conservation of DNAAF4 protein sequence and the pathogenicity of the mutation. Sequence alignment of DNAAF4 protein in human and other orthologs showed that DNAAF4 protein sequence was highly conserved at position of amino acid 373 (Figure 2D). Using alpha Fold to predict the structure of DNAAF4 protein, it was found that the mutation P. (G373E) did not affect the overall spatial structure of the protein, but only affected the local protein conformation, which meant that the mutation may not affect the function of the protein (Figure 2E). We used MutationTaster, SIFT and Polyphen-2 software to predict the pathogenicity of the mutation, demonstrating disease-causing, damaging and probably damaging, and evaluated the mutation as likely pathogenic according to ACMG guideline of 2015, (Table 2).

FIGURE 2. Identification of the DNAAF4 Mutation. (A) Schematic of chromosome 15 and the genomic structure of DNAAF4. The red rectangle represents exon9. The boxed Mutation was newly found in this study. (B) Schematic showing protein primary structure of DNAAF4; The mutation is located within the TPR domains (red rectangles) at the C terminus of DNAAF4. (C) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of proband and her family members. A novel homozygous variant DNAAF4 (C) 1118G>A (p. G373E) was identified in the proband. Her family members were heterozygous at the same position. (D) Orthologous protein sequence alignment of DNAAF4 from different species. The red arrow shows that the novel mutation occurred at highly conserved position in these species. (E) 3D mock structure of DNAAF4 protein. The white, orange, and green indicate the three TPR domains. The variant p. (G373E) is indicated by red color.

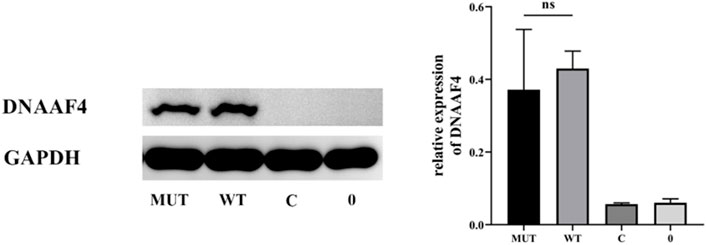

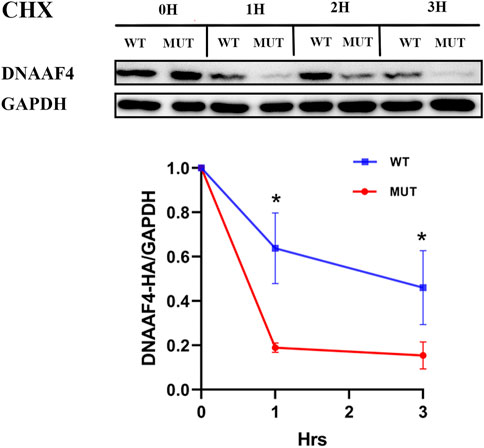

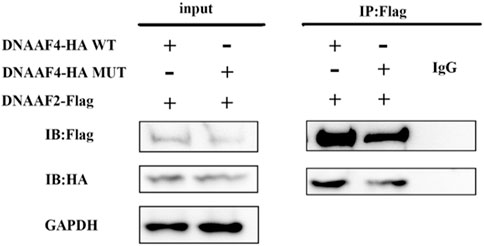

Further, we explored the effect of the mutation on DNAAF4 protein from three aspects: protein expression, stability and interaction with downstream protein. First, We generated DNAAF4 normal and mutant plasmids with the HA tag fused to the C-terminus of DNAAF4 protein (Supplementary Figure S1), and transfected them into HEK293T cells to ascertain the expression of protein. The levels of DNAAF4 protein extracted from HEK293T cells were detected by western blotting with DNAAF4 antibody. At the same experimental conditions, there was no significant difference in expression between mutant and normal DNAAF4 proteins, and HEK293T cells themselves did not express DNAAF4 protein without transfection of plasmid (Figures 3A,B). Second, To explore the difference in the stability of normal and mutant DNAAF4 proteins, cycloheximide (CHX), a bacterial toxin interfering with protein biosynthesis, was used. We detected the levels of normal and mutant DNAAF4 protein by western blotting with DNAAF4 antibody at 0, 1, 2, and 3 h after CHX added with final concentration of 100 ug/ml, and found that the protein expression of normal and mutant DNAAF4 was approximately equal at 0 h, and the quantity of the mutant protein showed faster reduction than normal protein with time (Figures 4A,B). Third, To study the interaction of DNAAF4 protein and its downstream DNAAF2 protein, we performed the co-immunoprecipitation experiments. We generated DNAAF2 plasmids with the Flag tag fused to the C-terminus of DNAAF2 protein (Supplementary Figure S1), transferring the DNAAF4 plasmid and DNAAF2 plasmid into HEK293T cells for co-expression, and validated that both normal and mutant DNAAF4 proteins can bind to the downstream DNAAF2 protein to exert their physiological functions by western blotting with Flag and HA antibodies (Figure 5). In summary, these experiments confirmed the mutation of DNAAF4 reduced the stability of DNAAF4 protein.

FIGURE 3. Effect of the Mutation on the expression of the DNAAF4 Protein. Forty-8 hours after transfection of plasmid in HEK293T, Western blot showed the expression of DNAAF4 protein. GAPDH is shown as a reference. MUT, mutated DNAAF4-HA plasmid; WT, normal DNAAF4-HA plasmid; C, blank plasmid; and 0, no plasmid. NS means not significant.

FIGURE 4. Effect of the Mutation on the Stability of the DNAAF4 Protein. (Top panel) Forty-eight hours after transfection of HEK293T with plasmid, then CHX added, Western blot showed the expression of DNAAF4 protein at 0, 1, 2, and 3 h after addition of CHX. GAPDH is shown as a reference. (Bottom panel) Quantification of the DNAAF4-HA stability relative to GAPDH for this experiment. The densitometric ratio of DNAAF4-HA to GAPDH at the time of addition of CHX is established as 100% and the ratio of the DNAAF4-HA to GAPDH at 1 and 3 h is compared to time 0. *, p < 0.05.

FIGURE 5. Interaction of the Mutated and Normal DNAAF4 Protein with DNAAF2 protein. DNAAF4 represents a new cytoplasmic axonemal dynein assembly factor, acting together with DNAAF2 at an early step in cytoplasmic ODAs and IDAs assembly. HA-tagged DNAAF4 was co-expressed with Flag-tagged DNAAF2 in HEK293T cells for Forty-eight hours. Extracts were immunoprecipitated with Flag, associated proteins were examined by western blotting using Flag and HA. GAPDH is shown as a reference.

DYX1C1 was formerly considered to be a candidate gene for dyslexia (Taipale et al., 2003), but its pathogenesis has not been confirmed. Later, mutations of DYX1C1 gene connected to cilia structure and motor function were discovered in patients without dyslexia. In 2013, Tarkar (Tarkar et al., 2013) found that mice deleting exons two to four of the DYX1C1 gene exhibited a PCD phenotype and further confirmed that DYX1C1 is the disease-causing gene of PCD. DYX1C1, now known as DNAAF4, is a newly identified dynein axonemal assembly factor that localizes in the cytoplasm of respiratory epithelial cells. It interacts with DNAAF2 to regulate the pre-assembly of IDAs and ODAs. There are only seven pathogenic mutations of DNAAF4 having been identified and documented in human gene mutation database (HGMD) until now.

DNAAF4 is located on chromosome 15q21.3 and consists of 10 exons. The DNAAF4 protein has 420 amino acids overall and three TPR domains at its C terminus. The TPR domains play a very important role in the structure and function of DNAAF4 protein, like interacting with molecular chaperones. All of the previously known mutations in DNAAF4 were non-sense mutations, which resulted in premature termination of protein translation before the TPR domains and caused severe clinical phenotypes with defection of ODAs and IDAs (Tarkar et al., 2013). In our study, we analysed and identified a missense mutation in DNAAF4, which is located in the TPR domains. WES for the genetic analysis, transmission electron microscopy, and immunofluorescence were used to identify a disease-causing homozygous DNAAF4 mutation. Then we further studied the effect of the mutation and found that the expression and function of DNAAF4 protein were not affected, but its stability was significantly decreased, which were consistent with the prediction of DNAAF4 protein structure. The instability may lead to insufficient pre-assembly of dynein in the cytoplasm, which also explained the partial absence of ODAs and IDAs in transmission electron microscopy of bronchial ciliary epithelium from the proband.

In PCD patients, different genotypes exhibit different clinical features, ranging from mild to severe phenotypes. Genotype-phenotype relationships have also attracted increasing attention (Brennan et al., 2021). Respiratory symptoms and infertility are the most important clinical phenotypes affecting the quality of life in PCD patients. The severity of respiratory symptoms is related to specific genes. Patients with biallelic mutations of CCDC39 or CCDC40, which encode coiled-coil domain containing proteins to regular the correct spatial structure of IDAs and radial spokes, experienced faster decline in pulmonary function than patients with mutations of DNAH5 (Davis et al., 2019). Conversely, individuals with biallelic MNS1 (Ta-Shma et al., 2018), DNAH9 (Fassad et al., 2018), CFAP53 (Silva et al., 2016) or RSPH1 (Knowles et al., 2014) mutations have a lower prevalence of neonatal respiratory distress and a later and milder onset of respiratory symptoms. Current studies revealed a link between particular genes and infertility phenotypes. The flagellum of sperm has the “9 + 2” structure similar to the motile cilia. Therefore, the mutations of PCD-related genes will also affect the structure and function of sperm flagellum, leading to infertility. Patients (both male and female) with mutations in the genes DNAH5 (Aprea et al., 2021), DNAH11 (Schwabe et al., 2008), CCDC114 (Onoufriadis et al., 2013) encoding the ODAs and RSPH4A (Castleman et al., 2009) encoding the radio-spoke protein are fertile. But absolute infertility is occurred in female with mutations in the genes DNAAF1 and LRRC6 encoding dynein axonemal assembly factor (Vanaken et al., 2017). Previous studies and reports have suggested that mutations in DNAAF4 can lead to infertility (male and female) (Tarkar et al., 2013; Guo T et al., 2022). Therefore, we can infer that the DNAAF4 mutation caused infertility in the proband. In the clinical phenotype of infertility, patients with different genders exhibit different manifestations for same gene mutations. It’s possible that this is connected to the differential expression of genes in sperms and oviduct epithelial cells. In addition, situs inversus is a indicative phenotype in diagnosis of PCD. Normal visceral placement is driven by the dynein of nodal cilia, so patients with gene mutations encoding non-dynein structural components such as RSPH1 (Knowles et al., 2014), RSPH3 (Jeanson et al., 2015), and HYDIN (Olbrich et al., 2012) have not been reported for situs inversus. The mechanism of different pathogenic genes leading to different clinical phenotypes, or even different mutations of the same pathogenic gene leading to different clinical phenotypes (Shoemark et al., 2018) is still unclear, which requires more basic research to explore.

Patients with known DNAAF4 mutations tend to exhibit severe phenotypes (Tarkar et al., 2013; Guo T et al., 2022), including neonatal respiratory distress, recurrent respiratory symptoms, and infertility. In this study, the proband did not manifest neonatal respiratory distress, but exhibited complete situs inversus, chronic sinusitis, bronchiectasis, recurrent bronchitis and pneumonia, and infertility, with low level of nNO and severe pulmonary ventilation dysfunction. Currently, researches on genotype-phenotype relationships are primarily based on summaries of the reported cases and our study could provide additional references for the genotype-phenotype research of PCD. Therefore, it is very important to further explore and summarize the genotype-phenotype relationships of PCD patients, which can provide personalized medical services for patients.

This study identified and confirmed a novel c.1118G>A (p.G373E) mutation of the DNAAF4 associated with severe phenotypes, and further explored its pathogenic mechanism. Our findings enrich the spectrum of DNAAF4 mutations in PCD, which can contribute to the diagnosis and treatment of PCD and advance reproductive genetic counseling.

The data presented in the study are deposited in the the China National Genebank (CNGB, https://db.cngb.org/cnsa/) repository, accession number CNP0003761.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by medical ethic committee of Third Xiangya Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

GJ (First Author): acquisition and analysis of data, Design and completion of experiments, and drafting manuscripts. LZ, YH, LL, TY, YZ: analysis of WES data and bioinformatics. XL, MJ, YH: critical revision of the manuscript. ZP, LT: Review & Editing. WX, JM (Corresponding Author): Design of experiments, Guidance on experimental techniques, Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Writing-Review and Editing. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing and approved the final version.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82070070 and 82270079).

We thank all the participants of this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.1087818/full#supplementary-material

Antony, D., Brunner, H. G., and Schmidts, M. (2021). Ciliary dyneins and dynein related ciliopathies. Cells 10, 1885. doi:10.3390/cells10081885

Anvarian, Z., Mykytyn, K., Mukhopadhyay, S., Pedersen, L. B., and Christensen, S. T. (2019). Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15, 199–219. doi:10.1038/s41581-019-0116-9

Aprea, I., N The-Menchen, T., Dougherty, G. W., Raidt, J., Loges, N. T., Kaiser, T., et al. (2021). Motility of efferent duct cilia aids passage of sperm cells through the male reproductive system. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 27, gaab009. doi:10.1093/molehr/gaab009

Bhatt, R., and Hogg, C. (2020). Primary ciliary dyskinesia: A major player in a bigger game. Breathe (Sheff) 16, 200047. doi:10.1183/20734735.0047-2020

Brennan, S. K., Ferkol, T. W., and Davis, S. D. (2021). Emerging genotype-phenotype relationships in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8272. doi:10.3390/ijms22158272

Castleman, V. H., Romio, L., Chodhari, R., Hirst, R. A., De Castro, S. C., Parker, K. A., et al. (2009). Mutations in radial spoke head protein genes RSPH9 and RSPH4A cause primary ciliary dyskinesia with central-microtubular-pair abnormalities. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84, 197–209. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.011

Davis, S. D., Rosenfeld, M., Lee, H. S., Ferkol, T. W., Sagel, S. D., Dell, S. D., et al. (2019). Primary ciliary dyskinesia: Longitudinal study of lung disease by ultrastructure defect and genotype. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 199, 190–198. doi:10.1164/rccm.201803-0548OC

Fassad, M. R., Shoemark, A., Legendre, M., Hirst, R. A., Koll, F., Le Borgne, P., et al. (2018). Mutations in outer dynein arm heavy chain DNAH9 cause motile cilia defects and situs inversus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 103, 984–994. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.016

Goutaki, M., Meier, A. B., Halbeisen, F. S., Lucas, J. S., Dell, S. D., Maurer, E., et al. (2016). Clinical manifestations in primary ciliary dyskinesia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 48, 1081–1095. doi:10.1183/13993003.00736-2016

Guo, T., Lu, C., Yang, D., Lei, C., Liu, Y., Xu, Y., et al. (2022). Case report: DNAAF4 variants cause primary ciliary dyskinesia and infertility in two han Chinese families. Front. Genet. 13, 934920. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.934920

Hirokawa, N., Tanaka, Y., Okada, Y., and Takeda, S. (2006). Nodal flow and the generation of left-right asymmetry. Cell 125, 33–45. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.002

Jeanson, L., Copin, B., Papon, J. F., Dastot-Le Moal, F., Duquesnoy, P., Montantin, G., et al. (2015). RSPH3 mutations cause primary ciliary dyskinesia with central-complex defects and a near absence of radial spokes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 97, 153–162. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.05.004

Knowles, M. R., Ostrowski, L. E., Leigh, M. W., Sears, P. R., Davis, S. D., Wolf, W. E., et al. (2014). Mutations in RSPH1 cause primary ciliary dyskinesia with a unique clinical and ciliary phenotype. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 189, 707–717. doi:10.1164/rccm.201311-2047OC

Knowles, M. R., Zariwala, M., and Leigh, M. (2016). Primary ciliary dyskinesia. Clin. Chest Med. 37, 449–461. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2016.04.008

Kozminski, K. G., Johnson, K. A., Forscher, P., and Rosenbaum, J. L. (1993). A motility in the eukaryotic flagellum unrelated to flagellar beating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90, 5519–5523. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.12.5519

Lie, H., Zariwala, M. A., Helms, C., Bowcock, A. M., Carson, J. L., Brown, D. E., et al. (2010). Primary ciliary dyskinesia in Amish communities. J. Pediatr. 156, 1023–1025. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.054

Mitchison, H. M., and Valente, E. M. (2017). Motile and non-motile cilia in human pathology: From function to phenotypes. J. Pathol. 241, 294–309. doi:10.1002/path.4843

Moore, A., Escudier, E., Roger, G., Tamalet, A., Pelosse, B., Marlin, S., et al. (2006). RPGR is mutated in patients with a complex X linked phenotype combining primary ciliary dyskinesia and retinitis pigmentosa. J. Med. Genet. 43, 326–333. doi:10.1136/jmg.2005.034868

Olbrich, H., Schmidts, M., Werner, C., Onoufriadis, A., Loges, N. T., Raidt, J., et al. (2012). Recessive HYDIN mutations cause primary ciliary dyskinesia without randomization of left-right body asymmetry. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 672–684. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.016

Omran, H., Kobayashi, D., Olbrich, H., Tsukahara, T., Loges, N. T., Hagiwara, H., et al. (2008). Ktu/PF13 is required for cytoplasmic pre-assembly of axonemal dyneins. Nature 456, 611–616. doi:10.1038/nature07471

Onoufriadis, A., Paff, T., Antony, D., Shoemark, A., Micha, D., Kuyt, B., et al. (2013). Splice-site mutations in the axonemal outer dynein arm docking complex gene CCDC114 cause primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92, 88–98. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.11.002

Schwabe, G. C., Hoffmann, K., Loges, N. T., Birker, D., Rossier, C., De Santi, M. M., et al. (2008). Primary ciliary dyskinesia associated with normal axoneme ultrastructure is caused by DNAH11 mutations. Hum. Mutat. 29, 289–298. doi:10.1002/humu.20656

Shoemark, A., Moya, E., Hirst, R. A., Patel, M. P., Robson, E. A., Hayward, J., et al. (2018). High prevalence of CCDC103 p.His154Pro mutation causing primary ciliary dyskinesia disrupts protein oligomerisation and is associated with normal diagnostic investigations. Thorax 73, 157–166. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-209999

Silva, E., Betleja, E., John, E., Spear, P., Moresco, J. J., Zhang, S., et al. (2016). Ccdc11 is a novel centriolar satellite protein essential for ciliogenesis and establishment of left-right asymmetry. Mol. Biol. Cell 27, 48–63. doi:10.1091/mbc.E15-07-0474

Ta-Shma, A., Hjeij, R., Perles, Z., Dougherty, G. W., Abu Zahira, I., Letteboer, S. J. F., et al. (2018). Homozygous loss-of-function mutations in MNS1 cause laterality defects and likely male infertility. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007602. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007602

Taipale, M., Kaminen, N., Nopola-Hemmi, J., Haltia, T., Myllyluoma, B., Lyytinen, H., et al. (2003). A candidate gene for developmental dyslexia encodes a nuclear tetratricopeptide repeat domain protein dynamically regulated in brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 11553–11558. doi:10.1073/pnas.1833911100

Tarkar, A., Loges, N. T., Slagle, C. E., Francis, R., Dougherty, G. W., Tamayo, J. V., et al. (2013). DYX1C1 is required for axonemal dynein assembly and ciliary motility. Nat. Genet. 45, 995–1003. doi:10.1038/ng.2707

Keywords: primary ciliary dyskinesia, female infertility, DNAAF4 mutation, pathogenic mechanism, autosomal recessive inheritance

Citation: Jiang G, Zou L, Long L, He Y, Lv X, Han Y, Yao T, Zhang Y, Jiang M, Peng Z, Tao L, Xie W and Meng J (2022) Homozygous mutation in DNAAF4 causes primary ciliary dyskinesia in a Chinese family. Front. Genet. 13:1087818. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.1087818

Received: 02 November 2022; Accepted: 01 December 2022;

Published: 13 December 2022.

Edited by:

Hamid Gourabi, Royan Institute, IranReviewed by:

Jiaxiong Wang, Suzhou Municipal Hospital, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Jiang, Zou, Long, He, Lv, Han, Yao, Zhang, Jiang, Peng, Tao, Xie and Meng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Xie, MTM5MDczMTU4NzRAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Jie Meng, bWVuZ2ppZUBjc3UuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.