95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Genet. , 09 July 2021

Sec. Behavioral and Psychiatric Genetics

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.647246

This article is part of the Research Topic Genetic and Epigenetic Mechanisms Underpinning Vulnerability to Developing Psychiatric Disorders View all 17 articles

Schizophrenia is a common neuropsychiatric disorder with complex pathophysiology. Recent reports suggested that complement system alterations contributed to pathological synapse elimination that was associated with psychiatric symptoms in schizophrenia. Complement component 3 (C3) and complement component 4 (C4) play central roles in complement cascades. In this study, we compared peripheral C3 and C4 protein levels between first-episode psychosis (FEP) and healthy control (HC). Then we explored whether single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at C3 or C4 genes affect peripheral C3 or C4 protein levels. In total, 181 FEPs and 204 HCs were recruited after providing written informed consent. We measured serum C3 and C4 protein levels using turbidimetric inhibition immunoassay and genotyped C3 and C4 polymorphisms using the Sequenom MassArray genotyping. Our results showed that three SNPs were nominally associated with schizophrenia (rs11569562/C3: A > G, p = 0.048; rs2277983/C3: A > G, p = 0.040; rs149898426/C4: G > A, p = 0.012); one haplotype was nominally associated with schizophrenia, constructed by rs11569562–rs2277983–rs1389623 (GGG, p = 0.048); FEP had higher serum C3 and C4 (both p < 0.001) levels than HC; rs1389623 polymorphisms were associated with elevated C3 levels in our meta-analysis (standard mean difference, 0.50; 95% confidence interval, 0.30 to 0.71); the FEP with CG genotype of rs149898426 had higher C4 levels than that with GG genotypes (p = 0.005). Overall, these findings indicated that complement system altered in FEP and rs149898426 of C4 gene represented a genetic risk marker for schizophrenia likely through mediating complement system. Further studies with larger sample sizes needs to be validated.

- Peripheral C3 and C4 protein levels were increased in first-episode psychosis (FEP).

- The rs149898426 polymorphisms of C4 gene were associated with schizophrenia.

- The CG genotype of rs149898426 were associated with higher serum C4 level in FEP comparing with GG genotype.

Schizophrenia is a severe and complicated neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by hallucinations, delusions and cognitive dysfunction (Kahn and Keefe, 2013; Kahn et al., 2015; Owen et al., 2016). While many studies attributed the causes of schizophrenia to biological or environmental factors, the etiology of schizophrenia are still unclear. Several lines of evidence suggested that dysregulation of the immune system contributed to the development of schizophrenia. Epidemiological studies found that infection and autoimmune disorders were associated with schizophrenia (Brown and Derkits, 2010; Benros et al., 2011, 2014; Arias et al., 2012; Khandaker et al., 2013). Besides, many cross-sectional studies reported that proinflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein (CRP) were increased in schizophrenia compared with healthy control (HC) (Miller et al., 2011; Fineberg and Ellman, 2013; Fernandes et al., 2016). Lastly, antipsychotics has been demonstrated to have immunomodulatory effects, for example, clozapine (Hinze-Selch et al., 1998; Roge et al., 2012). Thus, immune dysregulation could represent a vulnerability factor for schizophrenia.

Complement system, an important part of the innate immune system, play important roles in clearing microbes and damaged cells from an organism, triggering inflammation and destroying foreign invaders (Merle et al., 2015a,b). Recent evidence identified that complement system orchestrated the balance for neurodevelopmental processes (Stephan et al., 2012; Ricklin et al., 2016). For example, overactivation of complement system contributed to neurotoxicity and pathological synapse loss through microglia, leading to progressive dysfunction in Alzheimer disease (AD) (Shi et al., 2017; Heneka et al., 2018).

Complement component 3 (C3) and complement component 4 (C4) play dominant roles in complement cascades. The C3 gene is located on chromosome 19, consisting of 41 exons and the mRNA has 5101 bp. C3 is a convergent point for activation both classical and alternative complement pathways (Merle et al., 2015a,b). Genetic evidence suggests that the polymorphisms of C3 were associated with risk of schizophrenia (Rudduck et al., 1985; Fañanás et al., 1992; Ni et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018). And patients with schizophrenia had increased C3 protein levels in peripheral blood (Santos Sória et al., 2012; Ali et al., 2017) and serum C3 concentrations were positively correlated with PANSS scores (Li et al., 2016). The C4 gene has two isoforms, C4A and C4B, located within the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region on chromosome 6. C4A was proved to increase the risk for schizophrenia through mediating synapse pruning during postnatal development (Sekar et al., 2016).

The elucidation of pathophysiology in the early stages of schizophrenia may help understand disease etiology. First-episode psychosis (FEP) refers to the first time a person outwardly experiences symptoms of psychosis. Although some symptoms were unspecific in FEP, the underlying biological processes has changed, especially upregulating inflammatory status. Given that C3 and C4 are major plasma proteins of the complement pathway and are widely measured parameters during clinical practice, we investigated whether C3 or C4 protein levels are different between FEP and HC from our clinical data. Considering previous reports that C3 or C4 gene has multiple single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were at the genome-wide level (Yang et al., 2012), we selected several SNPs at C3 (rs11569562, rs2277983, rs1389623) and C4 (rs406658, rs2746414, rs149898426) genes to explore the associations between genotype and complement protein concentration in FEP.

A total of 181 FEPs (94 males, 87 females; mean age: 29.9 ± 10.0 years) and 204 HCs (96 males, 108 females; mean age: 30.0 ± 10.2 years) were recruited from Peking University Sixth Hospital. The diagnosis was made according to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria using a Structured Clinical Interview and people with FEP did not take medication regularly. We excluded HC with a history of mental health or neurological diseases from communities through simple unstructured interviews conducted by psychiatrists. All participants were given written informed consent before the study began. The study was conducted under established ethical standards and was approved by the ethics committee of Peking University Sixth Hospital.

We collected 5 mL venous blood from each subject, separated out serum by centrifugation, and stored it at –80°C until laboratory analysis. The genomic DNA was extracted from using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit. We selected 3 haplotype-tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (tagSNPs) by using the UCSC (GRCh37/hg19) genome browser1 for C3 and C4, respectively (C3: rs11569562, rs2277983, rs1389623; C4: rs406658, rs2746414, rs149898426). Genotyping was conducted for 6 tagSNPs by using the platform of the Sequenom MassArray system (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, United States). Locus-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and detection primers were designed with the MassARRAY Assay Design Version 3.0 software (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, United States). The DNA samples were amplified by multiplex PCR reactions and the obtained products were used for locus-specific single-base extension reaction. The final products were desalted and transferred to 384-element SpectroCHIP arrays. Allele typing was performed using MALDI-TOF MS spectroscopy. The mass spectrum was analyzed by the MassARRAY TYPER software (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, United States). All DNA samples were analyzed in technical duplicates. We genotyped each sample thrice to minimize genotyping errors and only consensus genotypes were processed for further analysis. Genotyping primer sequences are indicated in Table 1.

Serum C3 and C4 levels were measured using the turbidimetric inhibition immunoassay in an automatic chemistry analyzer, ROCHE (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., Basel, Switzerland) module Cobas 8000 (C702). The assays were performed strictly by the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. All samples were analyzed in duplicates and the mean of the two measurements was used in the analysis.

Pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD), haplotype construction, and genetic association analysis were performed by using Haploview 4.2 software2. Deviation of the genotype and allele frequency from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium were analyzed using a chi-square goodness-of-fit test. We conducted t-tests and a univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to examine the difference of serum complement protein levels (C3 and C4) between FEP and HC, considering that age and sex may affect serum complement protein levels. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to explore the interaction effects of group and genotype. Post hoc analyses were performed using a Tukey test. When the result from F-test was marginal significant (0.05 < p < 0.1), we would conduct a meta-analysis of the SNP for case group and control group to increase the statistical power. Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software3. Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as number (proportion). Results were considered nominally significant at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). Multiple testing adjustment will be controlled via Bonferroni adjustment for comparison of genotype and allele distribution for C3 and C4 gene. P < 0.05/3 was considered as significant for the reason that the total number of independence tests (excluding LD) was 3 for all 6 SNPs across two genes.

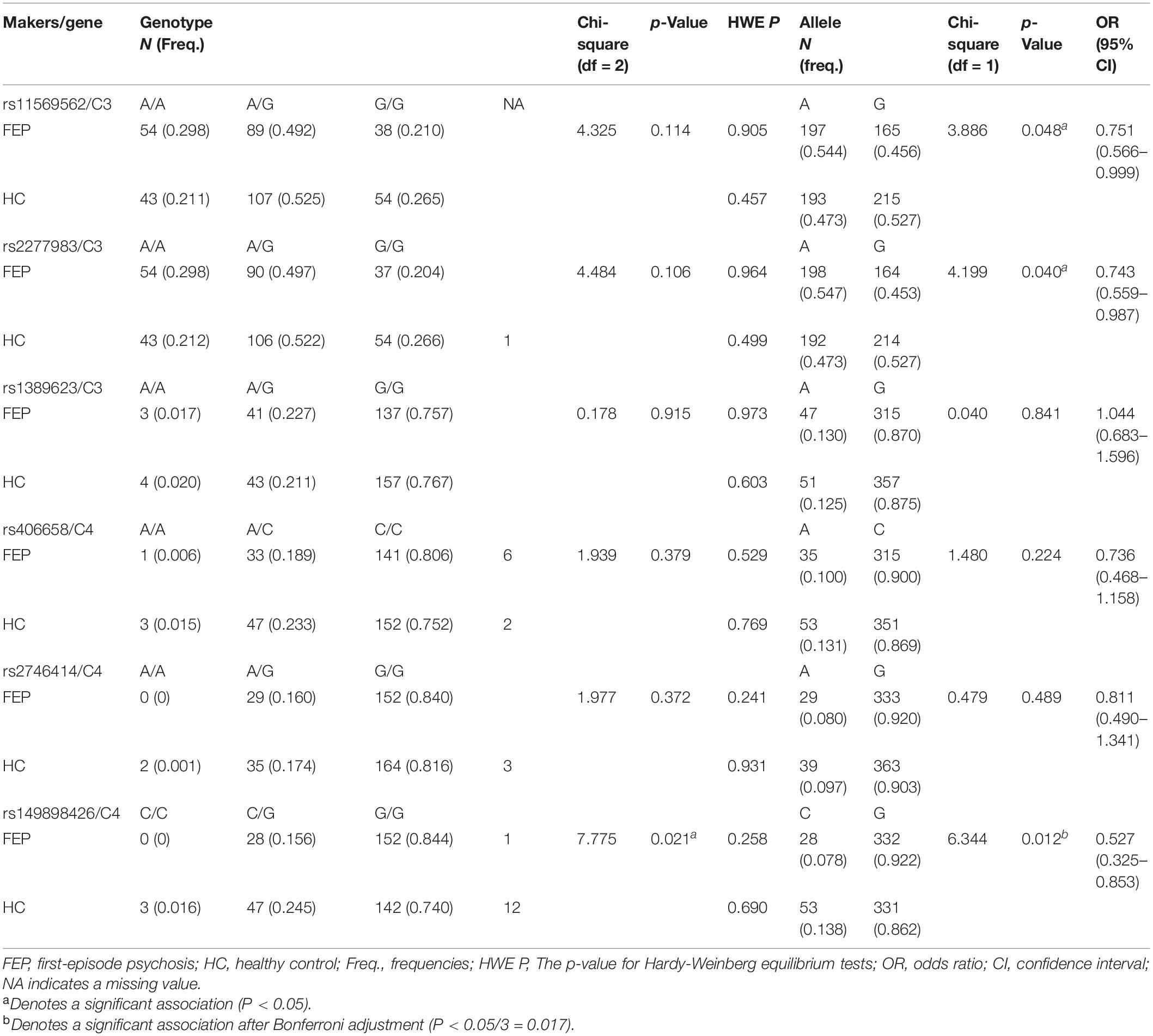

We observed no association of rs11569562, rs1389623, s406658, and rs2746414 polymorphism with schizophrenia for genotypes and alleles. There were two nominally significant associations between rs11569562 (p = 0.048) and rs2277983 (p = 0.040) alleles distributions and schizophrenia but no association between genotypes and schizophrenia. The genotypes (p = 0.0205) and alleles (p = 0.012 < 0.05/3) of rs149898426 were significantly different between FEP and HC. The genotypes and alleles frequencies of each polymorphism were presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Comparison of genotype and allele distribution of 6 SNPs of C3 and C4 gene between FEP and HC.

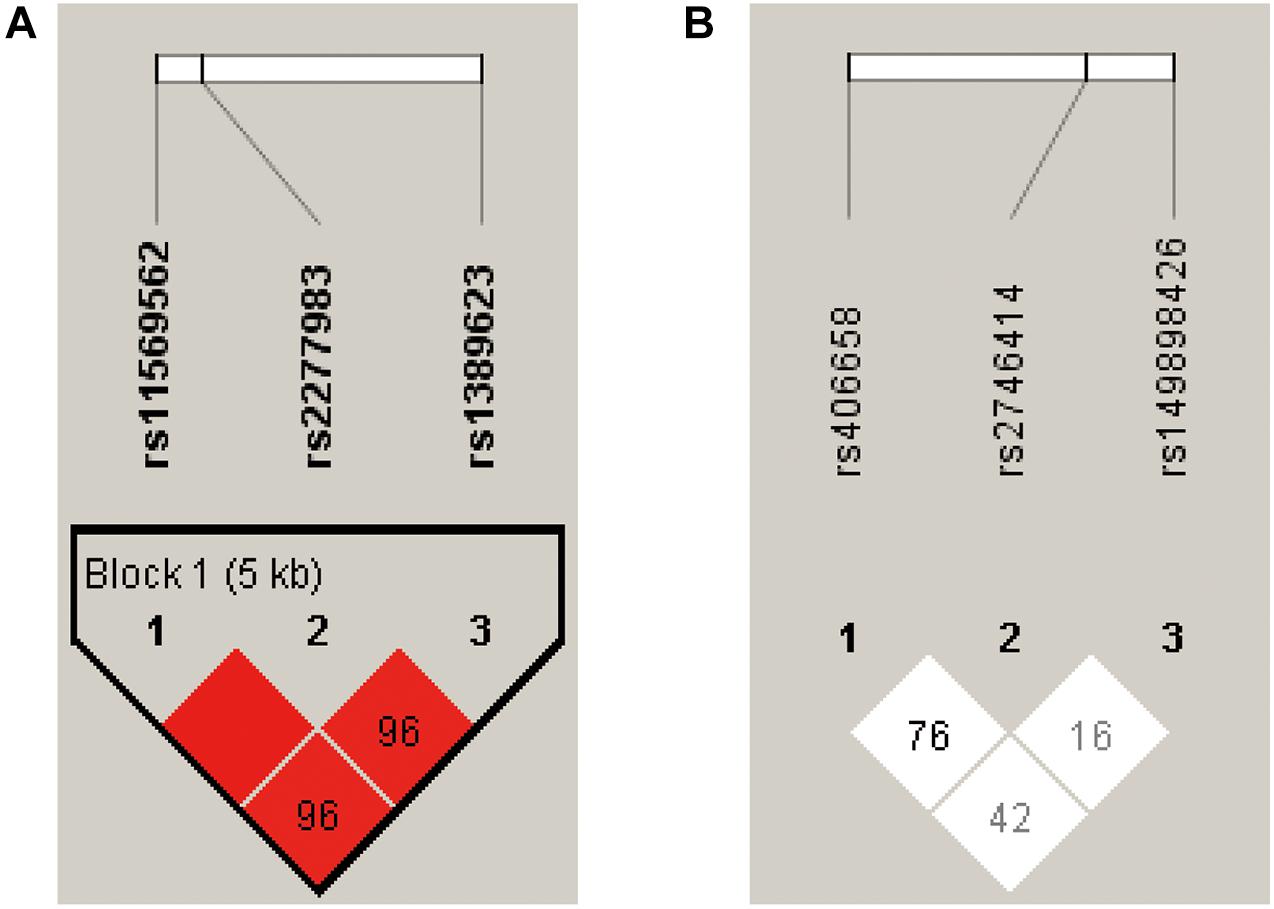

The LD map and block structures of C3 and C4 polymorphisms were shown in Figure 1. A haplotype block of C3 was constructed by rs11569562, rs2277983, and rs1389623: GGG haplotype was significantly associated with schizophrenia (χ2 = 3.922, p = 0.048); while after 10,000 times of permutation tests, the difference of haplotype GGG frequencies between FEP and HC were not significant (empirical p-value was 0.104) (see details in Table 3 and Figure 1A). No haplotype blocks were found in C4 gene (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. The pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis was applied to detect the inter-marker relationship of the three SNPs at the C3 and C4 gene receptively, by using the D’ values. According to the D’ values in this figure, (A) three SNPs constructed into one haplotype block in C3 gene. (B) No haplotype block was detected in C4 gene.

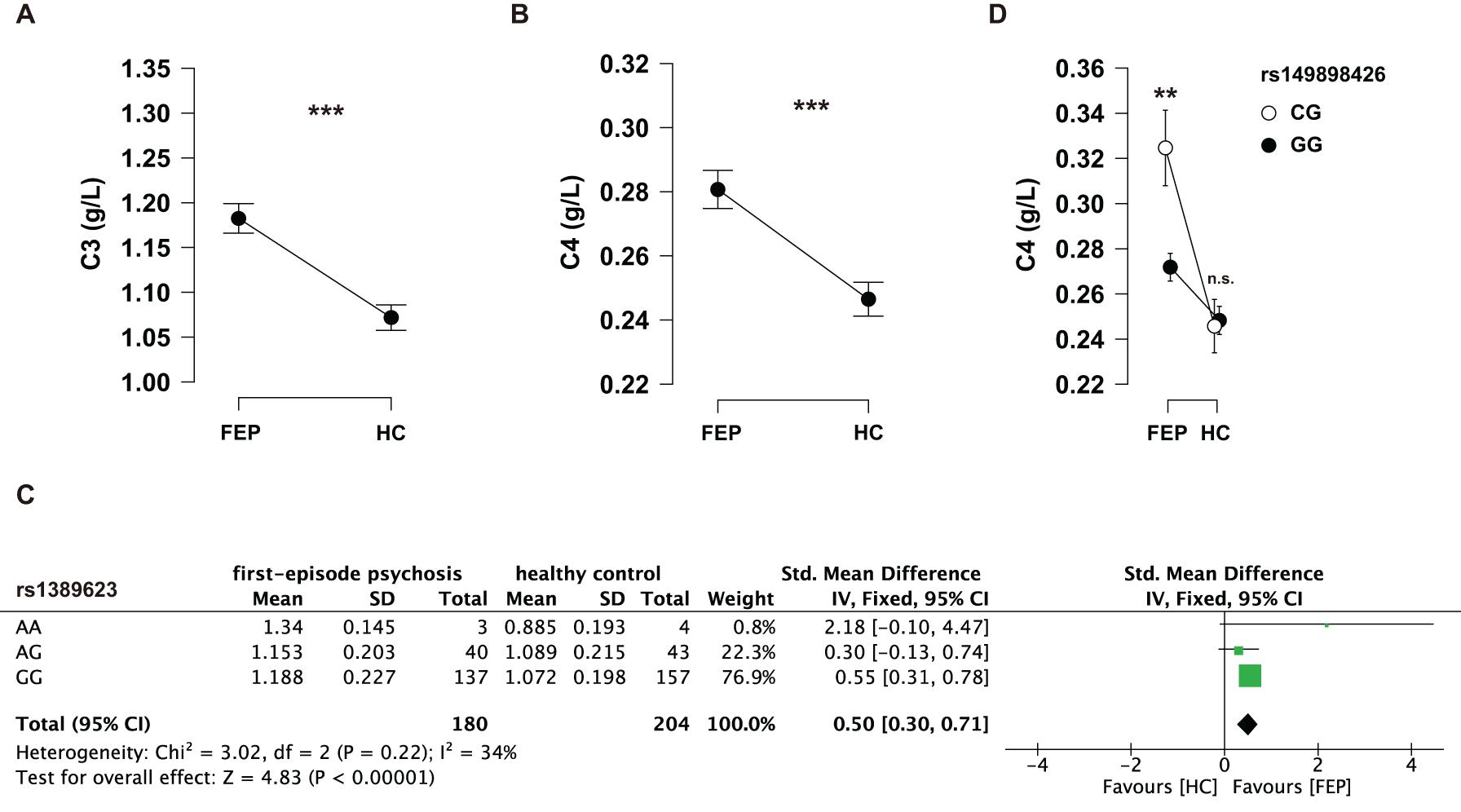

One sample testing C3 protein levels was excluded for being three SDs above the mean. The serum C3 protein levels (mean ± SD) in cases and controls were 1.18 ± 0.22 and 1.07 ± 0.20 g/L; the serum C4 protein levels (mean ± SD) in cases and controls were 0.28 ± 0.08 and 0.25 ± 0.08 g/L, respectively. T-tests showed that FEP had higher serum C3 (t = 5.11, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.52) and C4 (t = 4.21, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.44) protein levels than HC (Figures 2A,B). Although the differences of serum C3 and C4 protein levels were not significant considering age and sex in cases and controls, respectively (see details in Table 4), age- and sex-adjusted comparisons were performed with ANCOVA: the differences of serum C3 (F = 26.55, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.065) and C4 (F = 18.27, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.046) protein levels remained significant.

Figure 2. (A) Serum C3 protein levels between FEP and HC. (B) Serum C4 protein levels between FEP and HC. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-tests. (C) Serum C4 levels among the genotypes of rs149898426 (CG and GG) in FEP and HC receptively. Data were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc tests. Data shown in the figure represent mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s.: non-significant. (D) A meta-analysis of the genotypes of rs1389623 on serum C3 levels.

Serum C3 and C4 protein levels of individual genotypes were evaluated between the case and control groups using two-way ANOVAs. We found that the interaction effects of group (FEP vs. HC) and rs1389623 were marginal significant (F = 2.81, p = 0.062, partial η2 = 0.015) on serum C3 levels (see Supplementary Tables 1–2). A meta-analysis showed that rs1389623 polymorphism were associated with elevated serum C3 levels (Z = 4.83, p < 0.001) (see details in Figure 2C). There was no interaction effect between other genotypes and group on serum C3 protein levels (see Supplementary Tables 3–6). Besides, we excluded all CC genotypes in a two-way ANOVAs (group: FEP, HC × rs149898426 polymorphisms: CG, GG) on C4 protein levels, for the reason that there were three subjects with CC genotypes in HC and no subject in FEP. The interaction effects of group and rs149898426 were significant (F = 7.33, p = 0.007, partial η2 = 0.02) (see Supplementary Tables 7–8). Post hoc tests found that FEP who carry the CG genotypes of rs149898426 had higher serum C4 protein levels than the patients who carry the GG genotypes (t = 3.34, ptukey = 0.005) while HC not (t = −0.198, ptukey = 0.997) (Figure 2D). No other interaction of genotypes and group was significant in serum C4 protein levels (see Supplementary Tables 9–12).

The present study confirmed that complement system overactivated in FEP, which were correlated with genetic factors. We observed that FEP had higher serum C3 and C4 protein levels than HC, suggesting that aberrant expression of complement proteins may be potential biomarkers for schizophrenia; C4 polymorphism affected serum C4 protein levels in FEP but not in HC, suggesting that genotype may be considered as an important risk factor for the development of schizophrenia.

The first finding was that FEP had increased serum C3 and C4 protein levels compared with HC. The results replicated many previous findings in schizophrenia (Maes et al., 1997) and extended to patients that were not FEP. But two other studies had no similar findings in FEP (Kopczynska et al., 2019; Laskaris et al., 2019). One possible reason is that the sample size may not be sufficient to reach the statistical differences; both studies had lower sample sizes than our study. Another potential cause for this divergence of outcomes is race or ethnicity. In our study, study participants are limited to the Chinese Han population, while various racial groups were involved in other studies. However, one study pointed that individuals at ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis had elevated C3 and C4 protein levels (Laskaris et al., 2019), suggesting that alteration of complement system accompanied the development of schizophrenia. These results should be considered exploratory and further studies with larger cohorts would be required to confirm results.

To our knowledge, this is the first survey that compares serum C3 and C4 levels with their SNP in FEP of the China Han population. Two recent papers investigated the roles of C3 polymorphism in susceptibility to schizophrenia in the China Han population (Ni et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018). Although SNP rs11569562 in C3 was not associated with schizophrenia in the Chinese Han population (Zhang et al., 2018) consisting of 1086 patients with schizophrenia and 1154 HCs, patients with all genotypes of rs11569562 have higher serum C3 levels than the controls similar to our study. Other studies using expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) analysis revealed that rs2277984, which is adjacent to rs2277983 in our study, regulates C3 expression in the liver (Zhang et al., 2017), suggesting that SNPs in the C3 gene affected the expression of C3 genes to further impact the C3 protein translation. Similarly, one study found that in the region near C4 of chromosome 6, the more strongly an SNP associated with schizophrenia, the more strongly it correlated with predicted C4A expression (Sekar et al., 2016). In short, the genotype of the complement gene had effects on its expression, which concurs with our results.

The present study has a major limitation that the sample size was small and may underpower the whole study in terms of C3 and C4 genotype distribution. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution. Further studies with larger sample sizes will be required to achieve sufficient statistical power and elucidate a potential link between complement system and schizophrenia in China Han population.

Our results showed that first-episode psychosis had higher serum C3 and C4 protein levels than healthy control. C4 gene polymorphisms affected C4 protein levels in peripheral blood: the FEP carrying CG genotypes of rs149898426 had higher serum C4 protein levels than that of GG genotypes. The available evidence that complement proteins were elevated in FEP and polymorphisms of complement genes played a contributing role in regulating peripheral complement proteins concentration.

The data presented in the study are deposited in the Peking University Open Research Data repository, accession number 10635 (http://opendata.pku.edu.cn/api/access/datafile/10635).

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Sixth Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

WY provided the funds and designed the study. YC analyzed the data and wrote the draft of the manuscript. ZZ recruited schizophrenia patients and collected peripheral blood samples. Primers were designed by FL and LW. ZL supervised this study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1307000), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81825009, 81901358, and 81221002), Peking University Clinical Scientist Program supported by “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities” (BMU2019LCKXJ012), and Academy of Medical Sciences Research Unit (2019-I2M-5-006). The findings had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer QW declared a past co-authorship with the authors LW and WY to the handling editor.

We thank the participants who were involved in the study.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.647246/full#supplementary-material

Ali, F. T., Abd El-Azeem, E. M., Hamed, M. A., Ali, M. A. M., Abd Al-Kader, N. M., and Hassan, E. A. (2017). Redox dysregulation, immuno-inflammatory alterations and genetic variants of BDNF and MMP-9 in schizophrenia: pathophysiological and phenotypic implications. Schizophr. Res. 188, 98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.016

Arias, I., Sorlozano, A., Villegas, E., de Dios Luna, J., McKenney, K., Cervilla, J., et al. (2012). Infectious agents associated with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 136, 128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.026

Benros, M. E., Nielsen, P. R., Nordentoft, M., Eaton, W. W., Dalton, S. O., and Mortensen, P. B. (2011). Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for Schizophrenia: a 30-year population-based register study. Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 1303–1310. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030516

Benros, M. E., Pedersen, M. G., Rasmussen, H., Eaton, W. W., Nordentoft, M., and Mortensen, P. B. (2014). A Nationwide Study on the Risk of Autoimmune Diseases in Individuals With a Personal or a Family History of Schizophrenia and Related Psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 218–226. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13010086

Brown, A. S., and Derkits, E. J. (2010). Prenatal infection and Schizophrenia: a review of epidemiologic and translational studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 261–280. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030361

Fañanás, L., Moral, P., Panadero, M. A., and Bertranpetit, J. (1992). Complement genetic markers in schizophrenia: C3, BF and C6 polymorphisms. Hum. Hered. 42, 162–167. doi: 10.1159/000154060

Fernandes, B. S., Steiner, J., Bernstein, H. G., Dodd, S., Pasco, J. A., Dean, O. M., et al. (2016). C-reactive protein is increased in schizophrenia but is not altered by antipsychotics: meta-analysis and implications. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 554–564. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.87

Fineberg, A. M., and Ellman, L. M. (2013). Inflammatory cytokines and neurological and neurocognitive alterations in the course of Schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 951–966. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.001

Heneka, M. T., McManus, R. M., and Latz, E. (2018). Inflammasome signalling in brain function and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 610–621.

Hinze-Selch, D., Becker, E. W., Stein, G. M., Berg, P. A., Mullington, J., Holsboer, F., et al. (1998). Effects of clozapine on in vitro immune parameters: a longitudinal study in clozapine-treated schizophrenic patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 19, 114–122.

Kahn, R. S., and Keefe, R. S. E. (2013). Schizophrenia is a cognitive illness time for a change in focus. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 1107–1112. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.155

Kahn, R. S., Sommer, I. E., Murray, R. M., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Weinberger, D. R., Cannon, T. D., et al. (2015). Schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 1:15067. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.67

Khandaker, G. M., Zimbron, J., Lewis, G., and Jones, P. B. (2013). Prenatal maternal infection, neurodevelopment and adult schizophrenia: a systematic review of population-based studies. Psychol. Med. 43, 239–257. doi: 10.1017/s0033291712000736

Kopczynska, M., Zelek, W., Touchard, S., Gaughran, F., Di Forti, M., Mondelli, V., et al. (2019). Complement system biomarkers in first episode psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 204, 16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.12.012

Laskaris, L., Zalesky, A., Weickert, C. S., Di Biase, M. A., Chana, G., Baune, B. T., et al. (2019). Investigation of peripheral complement factors across stages of psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 204, 30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.11.035

Li, H., Zhang, Q., Li, N., Wang, F., Xiang, H., Zhang, Z., et al. (2016). Plasma levels of Th17-related cytokines and complement C3 correlated with aggressive behavior in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 246, 700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.061

Maes, M., Delange, J., Ranjan, R., Meltzer, H. Y., Desnyder, R., Cooremans, W., et al. (1997). Acute phase proteins in schizophrenia, mania and major depression: modulation by psychotropic drugs. Psychiatry Res. 66, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(96)02915-0

Merle, N. S., Church, S. E., Fremeaux-Bacchi, V., and Roumenina, L. T. (2015a). Complement system part I - molecular mechanisms of activation and regulation. Front. Immunol. 6:262. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00262

Merle, N. S., Noe, R., Halbwachs-Mecarelli, L., Fremeaux-Bacchi, V., and Roumenina, L. T. (2015b). Complement system part II: role in immunity. Front. Immunol. 6:257. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00257

Miller, B. J., Buckley, P., Seabolt, W., Mellor, A., and Kirkpatrick, B. (2011). Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in Schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol. Psychiatry 70, 663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.04.013

Ni, J., Hu, S., Zhang, J., Tang, W., Lu, W., and Zhang, C. (2015). A preliminary genetic analysis of complement 3 gene and Schizophrenia. PLoS One 10:e0136372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136372

Owen, M. J., Sawa, A., and Mortensen, P. B. (2016). Schizophrenia. Lancet 388, 86–97. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01121-6

Ricklin, D., Reis, E. S., and Lambris, J. D. (2016). Complement in disease: a defence system turning offensive. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 12, 383–401. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.70

Roge, R., e>Moller, B. K., Andersen, C. R., Correll, C. U., and Nielsen, J. (2012). Immunomodulatory effects of clozapine and their clinical implications: What have we learned so far? Schizophr. Res. 140, 204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.06.020

Rudduck, C., Beckman, L., Franzén, G., and Lindström, L. (1985). C3 and C6 complement types in schizophrenia. Hum. Hered. 35, 255–258. doi: 10.1159/000153555

Santos Sória, L. D., Moura Gubert, C. D., Ceresér, K. M., Gama, C. S., and Kapczinski, F. (2012). Increased serum levels of C3 and C4 in patients with schizophrenia compared to Eutymic patients with bipolar disorder and healthy. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 34, 119–120.

Sekar, A., Bialas, A. R., de Rivera, H., Davis, A., Hammond, T. R., Kamitaki, N., et al. (2016). Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature 530, 177–183. doi: 10.1038/nature16549

Shi, Q., Chowdhury, S., Ma, R., Le, K. X., Hong, S., Caldarone, B. J., et al. (2017). Complement C3 deficiency protects against neurodegeneration in aged plaque-rich APP/PS1 mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 9:eaaf6295. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6295

Stephan, A. H., Barres, B. A., and Stevens, B. (2012). The complement system: an unexpected role in synaptic pruning during development and disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 35, 369–389.

Yang, X., Sun, J., Gao, Y., Tan, A., Zhang, H., Hu, Y., et al. (2012). Genome-wide association study for serum complement C3 and C4 levels in healthy Chinese subjects. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002916

Zhang, C., Zhang, Y., Cai, J., Chen, M., and Song, L. (2017). Complement 3 and metabolic syndrome induced by clozapine: a cross-sectional study and retrospective cohort analysis. Pharmacogenomics J. 17, 92–97. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2015.68

Keywords: first-episode psychosis, complement protein concentration, single nucleotide polymorphism, Chinese Han population, case-control studies

Citation: Chen Y, Zhao Z, Lin F, Wang L, Lin Z and Yue W (2021) Relationships between Complement Protein Concentration and Genotype in First-episode Psychosis: Evidence from C3 and C4 in Peripheral Blood. Front. Genet. 12:647246. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.647246

Received: 29 December 2020; Accepted: 04 June 2021;

Published: 09 July 2021.

Edited by:

Elena Martín-García, Pompeu Fabra University, SpainReviewed by:

Qiang Wang, Sichuan University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Chen, Zhao, Lin, Wang, Lin and Yue. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Weihua Yue, ZHJ5dWVAYmptdS5lZHUuY24=; Zheng Lin, bGluenpyQDEyNi5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.