- 1Key Laboratory of Tropical and Subtropical Fisheries Resources Application and Cultivation, Ministry of Agriculture, Pearl River Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Guangzhou, China

- 2Shenzhen Key Lab of Marine Genomics, Guangdong Provincial Key Lab of Molecular Breeding in Marine Economic Animals, BGI Academy of Marine Sciences, BGI Marine, BGI Group, Shenzhen, China

- 3College of Fisheries, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China

- 4Fisheries College, Guangdong Ocean University, Zhanjiang, China

- 5College of Animal Science and Technology, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China

Doublesex and mab-3-related transcription factor (dmrt) genes are widely distributed across various biological groups and play critical roles in sex determination and neural development. Here, we applied bioinformatics methods to exam cross-species changes in the dmrt family members and evolutionary relationships of the dmrt genes based on genomes of 17 fish species. All the examined fish species have dmrt1–5 while only five species contained dmrt6. Most fish harbored two dmrt2 paralogs (dmrt2a and dmrt2b), with dmrt2b being unique to fish. In the phylogenetic tree, 147 DMRT are categorized into eight groups (DMRT1–DMRT8) and then clustered in three main groups. Selective evolutionary pressure analysis indicated purifying selections on dmrt1–3 genes and the dmrt1–3–2(2a) gene cluster. Similar genomic conservation patterns of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster with 20-kb upstream/downstream regions in fish with various sex-determination systems were observed except for three regions with remarkable diversity. Synteny analysis revealed that dmrt1, dmrt2a, dmrt2b, and dmrt3–5 were relatively conserved in fish during the evolutionary process. While dmrt6 was lost in most species during evolution. The high conservation of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster in various fish genomes suggests their crucial biological functions while various dmrt family members and sequences across fish species suggest different biological roles during evolution. This study provides a molecular basis for fish dmrt functional analysis and may serve as a reference for in-depth phylogenomics.

Introduction

Doublesex and Mab-3-related transcription factor (dmrt) genes are originally homologous to Doublesex (Dsx) in Drosophila melanogaster and Male abnormal 3 (Mab-3) in Caenorhabditis elegans, both of which play important roles in sex determination (Burtis and Baker, 1989; Zhu et al., 2000; Zarkower, 2001). In recent years, a large number of genes from the dmrt family have been identified from lower invertebrates to higher vertebrates, including corals, nematodes, fruit flies, frogs, fish, birds, and mammals, some of which have been confirmed to be related to sex differentiation (Hodgkin, 2002). Currently, in addition to Dsx and Mab, the dmrt family in vertebrates include nine dmrt genes (dmrt1–8 and dmrt2b) that share common characteristics with Dsx and Mab-3. Almost all of the encoded polypeptide chains contain a conserved DNA-binding motif, known as the Doublesex and Mab-3 (DM) domain, which is composed of six conserved cysteines and two histidines (locus 1 of CCHC and locus 2 of HCCC). Both loci form two highly intertwined zinc-finger-like DNA-binding regions can bind to the minor groove in DNA. Notably, this domain is highly conserved among organisms of different evolutionary types (Erdman and Burtis, 1993; Zhu et al., 2000).

Fish dmrt genes were first discovered in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) (Guan et al., 2000; Marchand et al., 2000). These genes in the dmrt family have now been identified in more than 30 fish species. Seven dmrt genes have been found in fish, including dmrt1–6 and dmrt2b. DMRT1 plays an important role in sex differentiation and testicular development (Matson and Zarkower, 2012), except the DM-W gene, a DMRT1 W-linked paralog in Xenopus laevis, play the opposite roles in primary ovary development (Yoshimoto et al., 2010). DMRT1 is specifically expressed only in the embryonic genital ridge and adult testes of human males, and is related to the expression of sex-determining genes and differentiation of primordial germ cells (Raymond et al., 1998; Moniot et al., 2000; Matson et al., 2011). Alternatively, studies on more than 20 fish species have determined that fish dmrt1 expression is related to male development regardless of the various sex determination mechanisms (Kobayashi et al., 2004, 2008; Johnsen et al., 2010), indicating that dmrt1 plays a key role in male germ cells self-renewal and differentiation, testicular development and spermatogenesis of fish (Herpin and Schartl, 2011; Lin et al., 2017). Furthermore, in the medaka Oryzias latipes, a Y-specific dmy gene, copy of autosome dmrt1, is the master sex-determining gene inducing male formation too.

The genomes of amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals contain only a single dmrt2 gene, whereas fish harbor two dmrt2 genes (dmrt2a and dmrt2b) (Liu et al., 2009; Su et al., 2015; Lyu et al., 2019). DMRT2 is widely distributed in the tissues of mammals and fish, and is expressed in both testes and ovaries (Kim et al., 2003; Winkler et al., 2004; El-Mogharbel et al., 2007). However, the function of DMRT2 has not been conserved during the evolution of species (Meng et al., 1999; Seo et al., 2006). For example, mouse DMRT2 is mainly involved in somite differentiation, in particular the patterning of the axial skeleton system (Lourenco et al., 2010). In contrast, both zebrafish dmrt2a and dmrt2b are involved in somite development, of which dmrt2a is necessary for symmetric somite formation and fast muscle differentiation (Saude et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2017), and dmrt2b regulates asymmetric organ positioning via the Hedgehog signaling pathway and therefore it is related to branchial arch and slow muscle development (Zhou et al., 2008; Li et al., 2018). This indicates that differences exist in the expression and functionality of dmrt2a and dmrt2b in fish.

Mammalian DMRT3 is highly expressed in the testis but not in the ovary; hence, it may be related to testicular differentiation and development (Hong et al., 2007). In mice, DMRT3 is also expressed in numerous non-gonadal tissues such as the embryonic forebrain and olfactory placode, in addition to spinal cord neurons, and thus it may be involved in neuronal specification (Smith et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2003; Andersson et al., 2012). Fish Dmrt3 is highly expressed in the testis and nervous system, and has accordingly been speculated to play a role in the developmental processes of the nerves and germ cells (Yamaguchi et al., 2006; Li et al., 2008; Dong et al., 2010).

The mouse dmrt4 gene is expressed in the testis and ovary, in addition to other various tissues (Kim et al., 2003). It can regulate the formation and development of ovarian follicles (Balciuniene et al., 2006). Alternatively, Xenopus DMRT4 is involved in the regulation of neurogenesis in the olfactory system (Huang et al., 2005b). In some fish species, the expression of dmrt4 in the ovary is significantly higher than that in the testis (Guan et al., 2000; Su et al., 2013; Wang, 2013); in other species, its expression is significantly higher in the testis than the ovary (Kondo et al., 2002; Dong and Chen, 2013; Sheng et al., 2014), whereas yet other species show high expression in both organs (Yamaguchi et al., 2006). In addition, dmrt4 is also expressed in the spleen (Yamaguchi et al., 2006; Sheng et al., 2014), kidney (Kondo et al., 2002; Sheng et al., 2014), gills (Kondo et al., 2002; Wang, 2013), and brain (Dong and Chen, 2013) in fish. Hence, it has been speculated to be related to immune and nervous system development.

Mouse DMRT5 is mainly expressed in brain tissue and is necessary for the early embryonic development of the cerebral cortex (Veith et al., 2006a; Konno et al., 2012). As a novel neurogenic factor, DMRT5, together with DMRT3, jointly controls hippocampal development and neocortical area map formation (Muralidharan et al., 2017; De Clercq et al., 2018). Fish dmrt5 is highly expressed primarily in the brain but can also be found in the gonads, eyes, and pituitary gland (Guo et al., 2004; Veith et al., 2006a; Yamaguchi et al., 2006; Gu et al., 2019). Furthermore, dmrt5 plays a key role in zebrafish neurogenesis in the telencephalon (Yoshizawa et al., 2011) and can regulate corticotrope and gonadotrope differentiation in the pituitary (Graf et al., 2015), in addition to spermatogenesis (Xu et al., 2013).

Mammalian DMRT6 is mainly expressed in gonadal intermediate cells and differentiating spermatogonia. It plays a crucial role in coordinating the transition of primordial germ cells from the mitotic to meiotic developmental programs during spermatogenesis (Zhang X.et al., 2014) and is also expressed in the embryonic brain of mice (Kim et al., 2003). Early studies have suggested that the dmrt6 gene is missing in fish (Veith et al., 2006b). However, recent studies have found that certain fish, such as coelacanth, tilapia, and Southern catfish also carry the dmrt6 gene, and that tilapia dmrt6 is involved in spermatogenesis (Forconi et al., 2013; Zhang X.et al., 2014). However, DMRT7 and DMRT8 are only present in mammals. The two genes are very similar, although DMRT8 does not have a complete DM domain. DMRT7 is specifically expressed in the male and female gonads and is related to mouse gonadal development and spermatogenesis (Kawamata and Nishimori, 2006; Hong et al., 2007). In comparison, DMRT8 is highly expressed in the male gonads and may have evolved from DMRT7 (Ottolenghi et al., 2002; Veith et al., 2006a).

Currently, reports are only available regarding the phylogenetic analysis of pan-arthropod and pan-metazoan DMRT family members (Volff et al., 2003; Wexler et al., 2014; Panara et al., 2019); to our knowledge, no studies have yet been published on the phylogeny of fish dmrt family. However, fish comprise a wide variety of species and previous reports have shown that members of the fish dmrt family own unique features such as two paralogs of dmrt2 genes (dmrt2a and dmrt2b), in addition to diverse tissue expression of the same gene family member in various fish (e.g., dmrt4), thus suggesting a remarkable difference in function. As the sequences of DMRT family members are highly variable with only the DM domain [∼49 amino acids (aa)] exhibiting high sequence homology (Volff et al., 2003), it is difficult to accurately determine the evolutionary relationship among the family members based on such short sequences, which in turn has limited our understanding of the history of DMRT functional development.

Nevertheless, in recent years the whole-genome sequencing of many fish species has significantly facilitated the in-depth and systematic analysis on the evolutionary relationships among gene family members. In this study, we therefore employed the fine genomic map of largemouth bass recently obtained using third-generation sequencing by our team and collected the dmrt sequences of 16 fish species with different taxonomic positions from published whole-genome sequences, in order to analyze the sequence structure, phylogenetic relationship, sequence conservation, and synteny of members of the fish dmrt family. These findings will lay a solid foundation for a more systematic understanding of the structural characteristics of these members in fish dmrt family, and for further investigations into the different functions of fish dmrt family members in sex determination or differentiation along with their underlying mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Sequence Collection

In the present study, we employed two strategies to collect nucleotide or deduced amino acid sequences for dmrt family members in various vertebrates (Supplementary Table S1). For those with publicly available sequences, such as in human (Homo sapiens) and mouse (Mus musculus), we downloaded the sequences from NCBI or Ensembl (Supplementary Table S2). Other dmrt sequences were extracted from corresponding genome databases through BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) and Genewise (Birney et al., 2004).

In brief, we used zebrafish (Danio rerio), Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes), and mouse DMRT protein sequences from NCBI as the references, and mapped them onto the examined genomes using tBLASTn with an E-value <1e–5 and an alignment rate>0.6. Solar v0.9.6 was applied to connect high-identity segment pairs. Subsequently, we discarded those low-quality results with alignment rate <0.6 and mapping identity <0.5. Finally, each gene sequence was predicted on the target genomic region using Exonerate v2.2.0 (Slater and Birney, 2005), and extended 5 kb in the upstream and downstream directions to obtain the integrated gene model. A total of 147 dmrt sequences were derived from 23 representative vertebrate species, including 2 mammals (human and mouse), 2 birds (chicken Gallus gallus and zebra finch Taeniopygia guttata), 1 reptile (green Anole Anolis carolinensis), 1 amphibian (Western clawed frog Xenopus tropicalis), and 17 fish species belonging to two classes (Actinopterygii and Sarcopterygii), and ten superorders (Percomorpha: largemouth bass, Asian sea bass Lates calcarifer, European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax, Japanese pufferfish Takifugu rubripes, Chinese tongue sole Cynoglossus semilaevis, and threespine stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus; Atherinomorpha: Japanese medaka and southern platyfish Xiphophorus maculatus; Protacanthopterygii: Atlantic salmon Salmo salar; Paracanthopterygii: Atlantic cod Gadus morhua; Ostariophysi: channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus and electric eel Electrophorus electricus; Clupeomorpha: Atlantic herring Clupea harengus; Elopomorpha: Japanese eel Anguilla japonica; Osteoglossomorpha: Asian arowana Scleropages formosus; Holostei: spotted gar Lepisosteus oculatus; Coelacanthiformes: African coelacanth Latimeria chalumnae).

Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

We performed phylogenetic analysis on these collected dmrt sequences. MAFFT v7.273 (Katoh et al., 2002) was employed to align these sequences. Gblocks was used to find conserved fragments with the following parameter settings: minimum number of sequences for a conserved/flank position (75/75), maximum number of contiguous non-conserved positions (50), minimum length of a block (50), allowed gap positions (all). ProtTest v3.42 was operated to determine the best-fit models of amino acid replacement (Darriba et al., 2011). Based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) algorithm, we set the best-fit model as “JTT+I+G+F.” Finally, we utilized PhyML 3.0, MrBayes v3.24 7, and MEGA v7.0 8 to analyze these sequences with 1,000,000 generations for Ngen and 100 for Samplefreq (Ronquist et al., 2012). Branch support values were calculated using Bayesian posterior probabilities. Evolview (He et al., 2016) was applied to edit constructed phylogenetic trees.

Identification of Conserved Synteny for the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) Gene Cluster (Synteny Analysis)

To evaluate the conservation of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster, we explored conserved genes in the upstream and downstream regions (20 kb) within the genomes of 19 examined species, using zebrafish genomic sequence as the reference, since the zebrafish genome is currently the best fish genome assembly with the highest quality and the completest genome annotation. These examined genome assemblies were explored using tBLASTn (Altschul et al., 1990), and the best-fit results were selected using a Perl script and Adobe Illustrator.

Substitution Rate Estimation and Comparison (Ka/Ks Analysis)

We calculated the average non-synonymous substitutions (Ka), synonymous substitutions (Ks), and Ka/Ks among dmrt1, dmrt2(2a), dmrt3, and the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster to test the selective pressure at the codon-based sequence level among various species. First, we aligned dmrt gene sequences from each species to spotted gar (L. oculatus; as the reference sequence) by using Prank v100802 with the “-codon” model (Loytynoja and Goldman, 2005). Subsequently, we calculated the Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks values of each pair using Ka/Ks Calculator v2.0 with four different algorithms, including gMYN (Wang D.P.et al., 2009), gYN (Wang D.et al., 2009), MYN (Zhang et al., 2006), and YN (Yang and Nielsen, 2000).

Analysis of Regulatory Regions and Cross-Species Comparisons of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) Gene Cluster

Complete genomic sequences with 20 kb-upstream/downstream regions of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster were extracted from various species. We applied mVISTA (Frazer et al., 2004) to align these relevant genomic sequences. This tool can align and compare long sequences based on the window-based comparisons of sequence conservation.

Repetitive elements were annotated using RepeatMasker v4.06 software (Chen, 2004), and the zebrafish genomic sequence was used as the reference. Pair-wise sequence comparisons were determined with a threshold of 70% identity in each 50-bp window. In addition, five typical regulatory elements, including BRE, CAAT box, E box, GC box, and TATA box, were predicted in each sequence using a Perl script (the motif function in Primer 5.0 and Genomatix MatInspector). Finally, Adobe Illustrator and R were applied to produce graphs for the information obtained.

Results

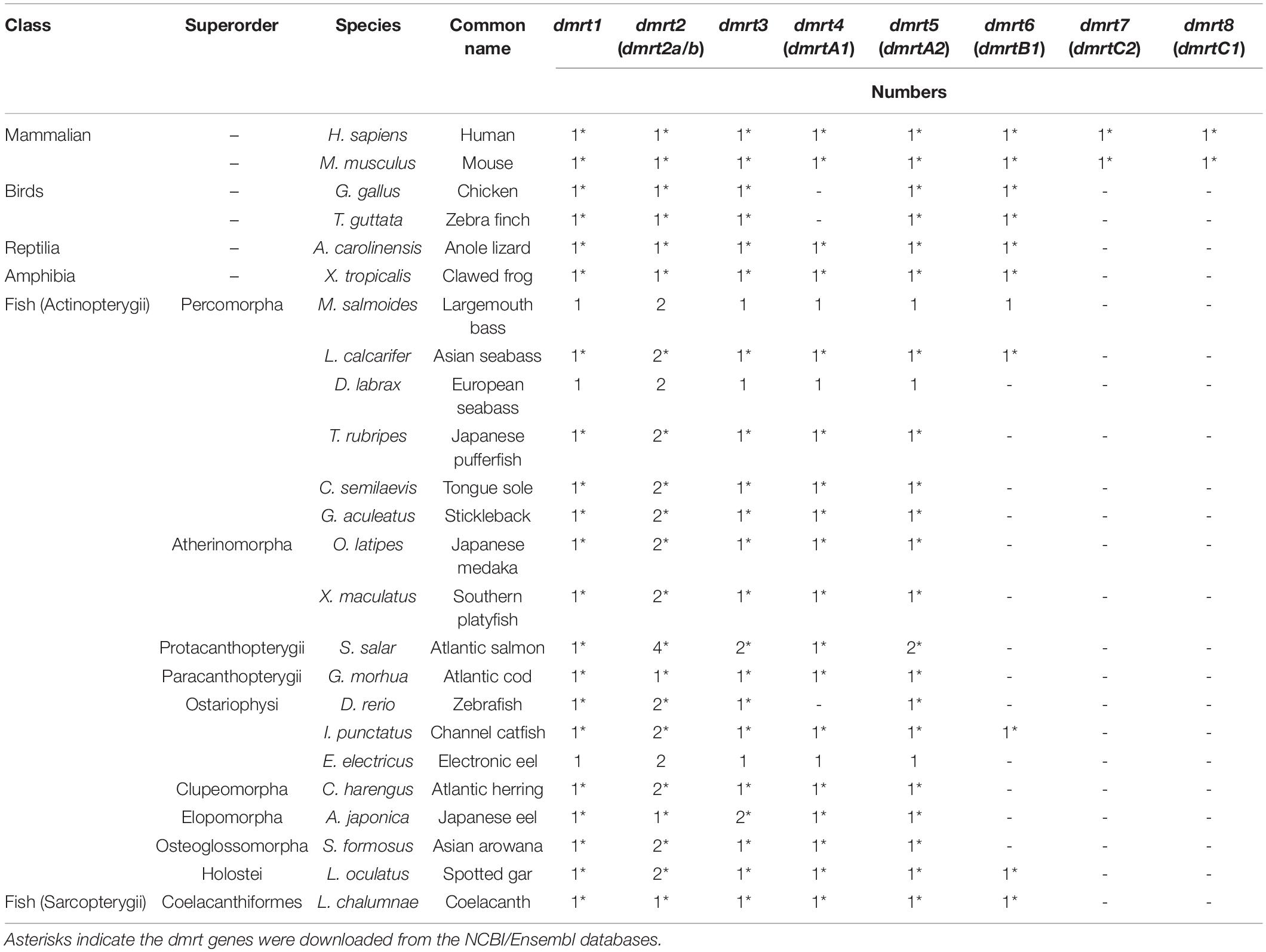

Cross-Species Changes in dmrt Family Members and Copy Numbers

A total of 147 dmrt sequences were derived from 23 representative vertebrate species (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables S1, S2). Among them, 128 dmrt sequences for 17 species were downloaded from the NCBI/Ensembl databases (asterisk in Table 1 and Accession number in Supplementary Table S2). The remaining 19 dmrt sequences for three species were extracted from genomes through the method described in section “Similarities and Variances of the dmrt Gene Family Members in Various Fish Species.” These nucleotide sequences and corresponding deduced protein sequences were used for our further data analysis.

In mammals, eight dmrt genes (dmrt1–dmrt8) were identified in their genomes. However, in other species, dmrt7 and dmrt8 were lost. In addition, dmrt4 was also lost in birds. In the fish dmrt gene family, dmrt1–dmrt5 showed relatively high conservation. Among these, dmrt2 usually consisted of two paralogs (dmrt2a and dmrt2b) in most fish species, with only three species (Atlantic cod, Japanese eel, and coelacanth) carrying a single paralog. dmrt6 was only found in five fish species, i.e., largemouth bass, Asian sea bass, channel catfish, spotted gar, and African coelacanth. In addition, some of the dmrt genes were duplicated in Atlantic salmon (dmrt2, 3, 5) and Japanese eel (dmrt3; see Table 1).

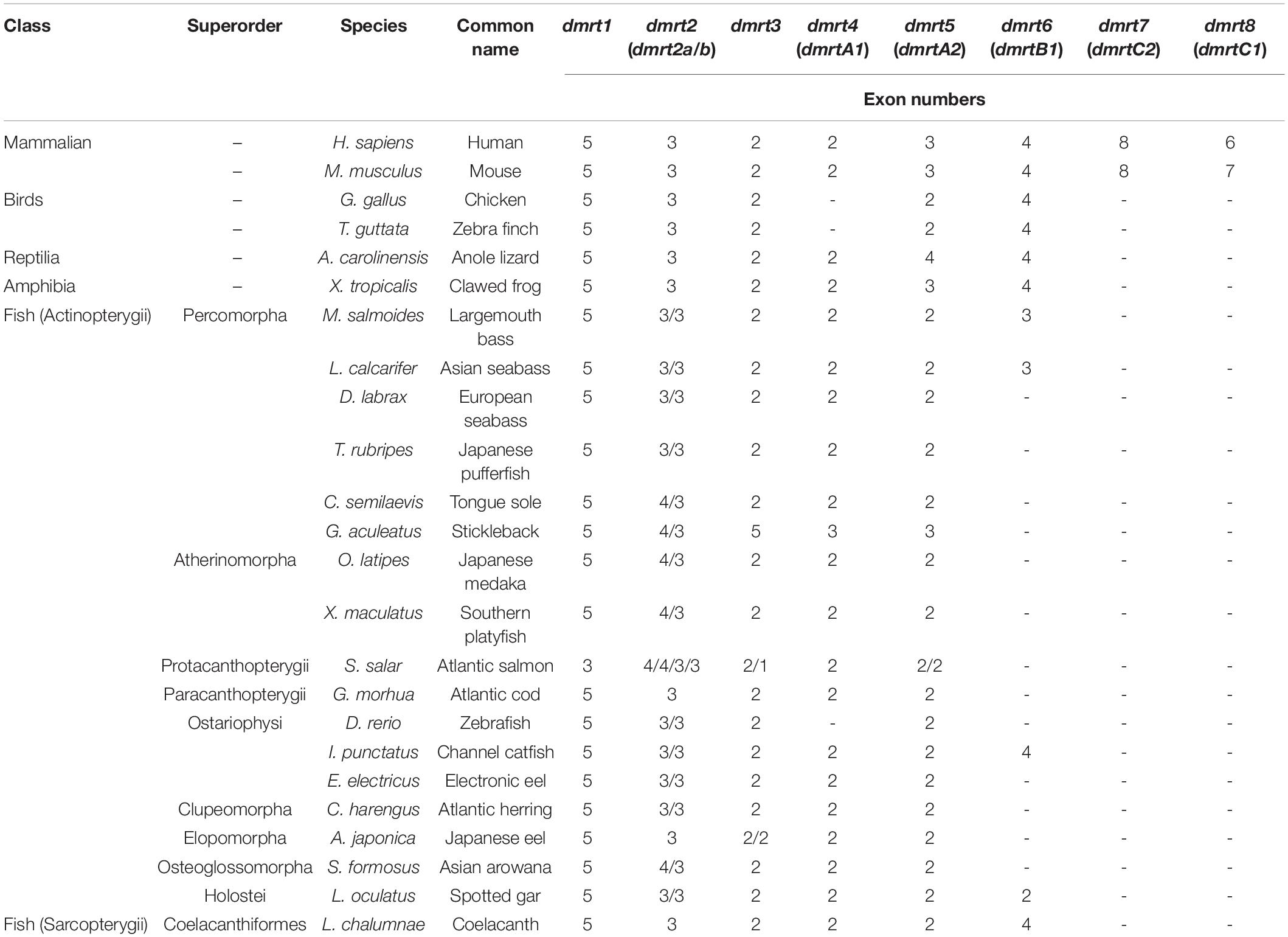

Structural Characterization and Evolutionary Analysis of the dmrt Family Genes

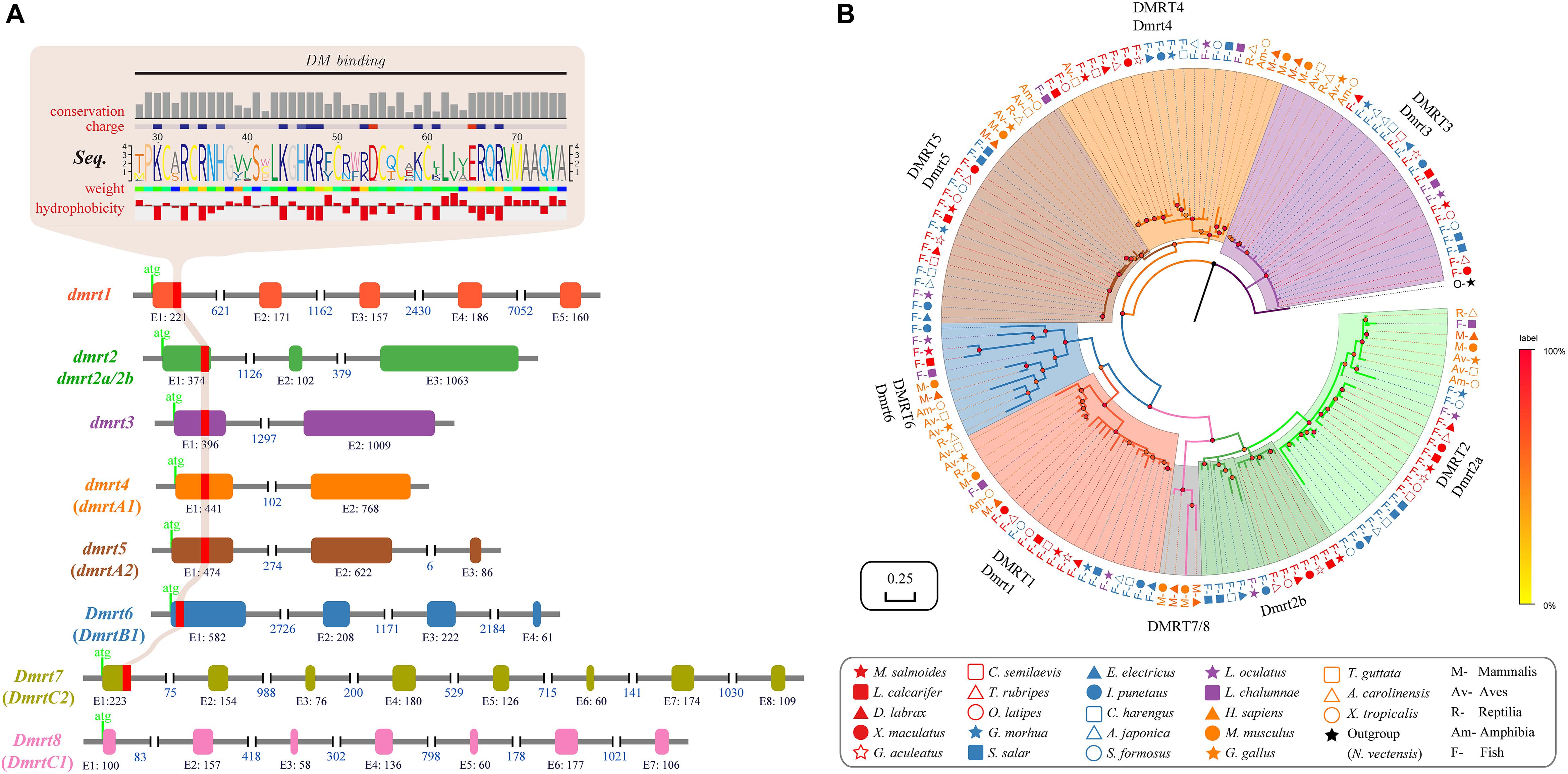

The gene structure of dmrt1 is composed of five exons in all examined species except for Atlantic salmon (Table 2 and Figure 1A), and a highly conserved DM domain (with a total of 49 aa) is located in the DMRT1 protein. In comparison, dmrt2 contains three exons and dmrt3–dmrt4 contain two exons in most examined species. Dmrt5 consists of 2 to 4 exons in higher vertebrates but only two in all examined fish species except for Stickleback (Table 2). Dmrt6 contains four exons in higher vertebrates, whereas the number of exons in fish varies greatly (from 2 to 4). dmrt7 and dmrt8 can only be identified in mammals, and both contain a large number of exons (8 for dmrt7, 6–7 for dmrt8). Except for DMRT8, all DMRT proteins (DMRT1–7) contain a conserved DM domain, often locating in the first exon of each gene (Figure 1A).

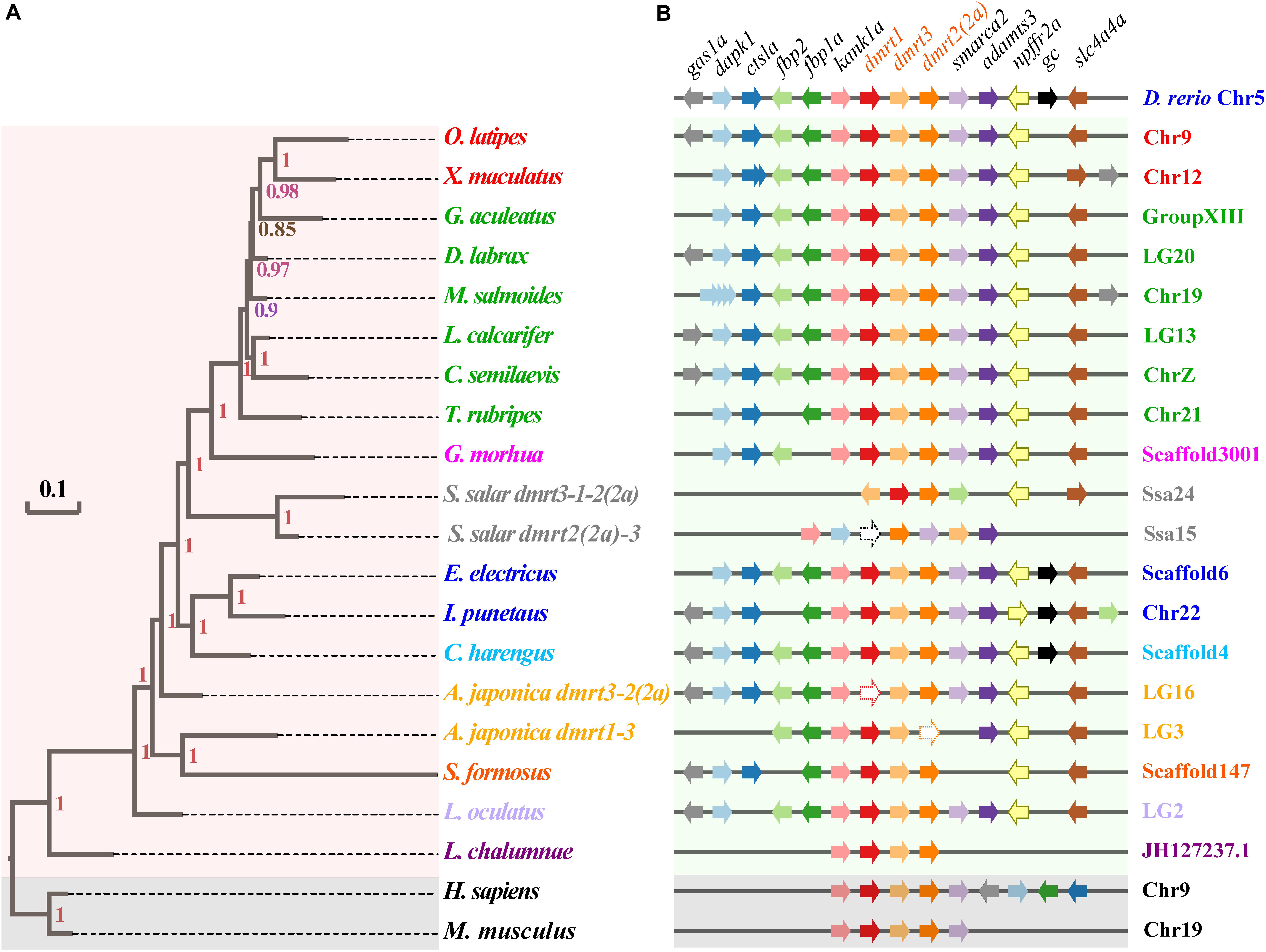

Figure 1. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the dmrt family in vertebrates. (A) Various structures of dmrt genes. The genomic structures of dmrt1–dmrt5 are based on the data of Japanese pufferfish, whereas those of dmrt6–dmrt8 are derived from the relevant data of mouse. (B) A Bayesian phylogenetic tree of 147 dmrt sequences. The phylogenetic analysis was performed using MrBayes v3.2.6. Amino acid replacement model selection was calculated using ProtTest with the best-fit model of JTT+I+G+F. The tree is rooted with the N. vectensis dmrtA.

Using DMRTA protein sequence of the sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis) as the out-group, we constructed a protein-based phylogenetic tree (Figure 1B), in which the DMRT family is distinctly categorized into eight groups (DMRT1–DMRT8). All DMRT proteins are distributed in the following three main groups: Group 1 includes five subfamilies, i.e., DMRT1, 2, 6, 7, and 8. DMRT2 was placed as the sister of DMRT7/8 and DMRT1 as the sister of DMRT6, suggesting a closer evolutionary relationship among these subfamilies. The subfamilies DMRT2, 7, and 8 were together placed as a sister group to the DMRT1 and 6 subfamilies. Group 2 includes DMRT4 and DMRT5. Group 3 contains only one subfamily DMRT3 (see more details in Figure 1B).

The dmrt1-dmrt3-dmrt2(2a) Cluster in Fish Genomes

Syntenic relationships of the dmrt1-dmrt3-dmrt2(2a) gene cluster were analyzed in 17 fish species, and using zebrafish (Cypriniformes, Ostariophysi) as the base reference. The dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster is relatively conserved in various fish species; consistent with this, fish within the same superorder were clustered together (Figure 2A). A total of 11 genes (gas1a, dapk1, ctsla, fbp2, fbp1a, kank1a, smarca2, adamts3, npffr2a, gc, and slc4a4a) neighbor the zebrafish dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster (Supplementary Table S3). All these genes were also found to neighbor the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster in channel catfish and Atlantic herring, whereas some genes were lost around this gene cluster in the remainder fish species (with frequent loss of the gc).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree and synteny conservation of the fish dmrt1-dmrt3-dmrt2(2a) gene clusters. (A) The rectangular Bayesian phylogenetic tree, rooted with human and mouse sequences. Numbers besides the nodes are Bayesian posterior probabilities (colored). (B) The synteny of examined dmrt1-dmrt3-dmrt2(2a) gene clusters. Full names of relevant genes are provided in Supplementary Table S3.

Mammals have lost larger numbers of genes next to this cluster, which also happens in two fish species (Atlantic salmon and coelacanth). Furthermore, in some fish species, such as largemouth bass, the dapk1 gene experienced a polyploidization event to generate four tandem duplicated copies. This phenomenon was also observed in the southern platyfish, which harbors two copies of the ctsla gene in its genome. Moreover, in both largemouth bass and southern platyfish, the gas1a gene experienced a translocation and inversion event as well (see more details in Figure 2B).

Substitution Rates (Ka/Ks) of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) Cluster in Fish Genomes

Ka/Ks represents the ratio of non-synonymous substitutions (Ka) to synonymous substitutions (Ks). This ratio can be used to determine whether there is selective pressure on a given protein-coding gene. It is generally believed that synonymous mutations are not subjected to natural selection, whereas non-synonymous mutations are. Ka/Ks > 1 implies the existence of positive selection; Ka/Ks = 1 suggests neutral selection; and Ka/Ks < 1 indicates purifying selection.

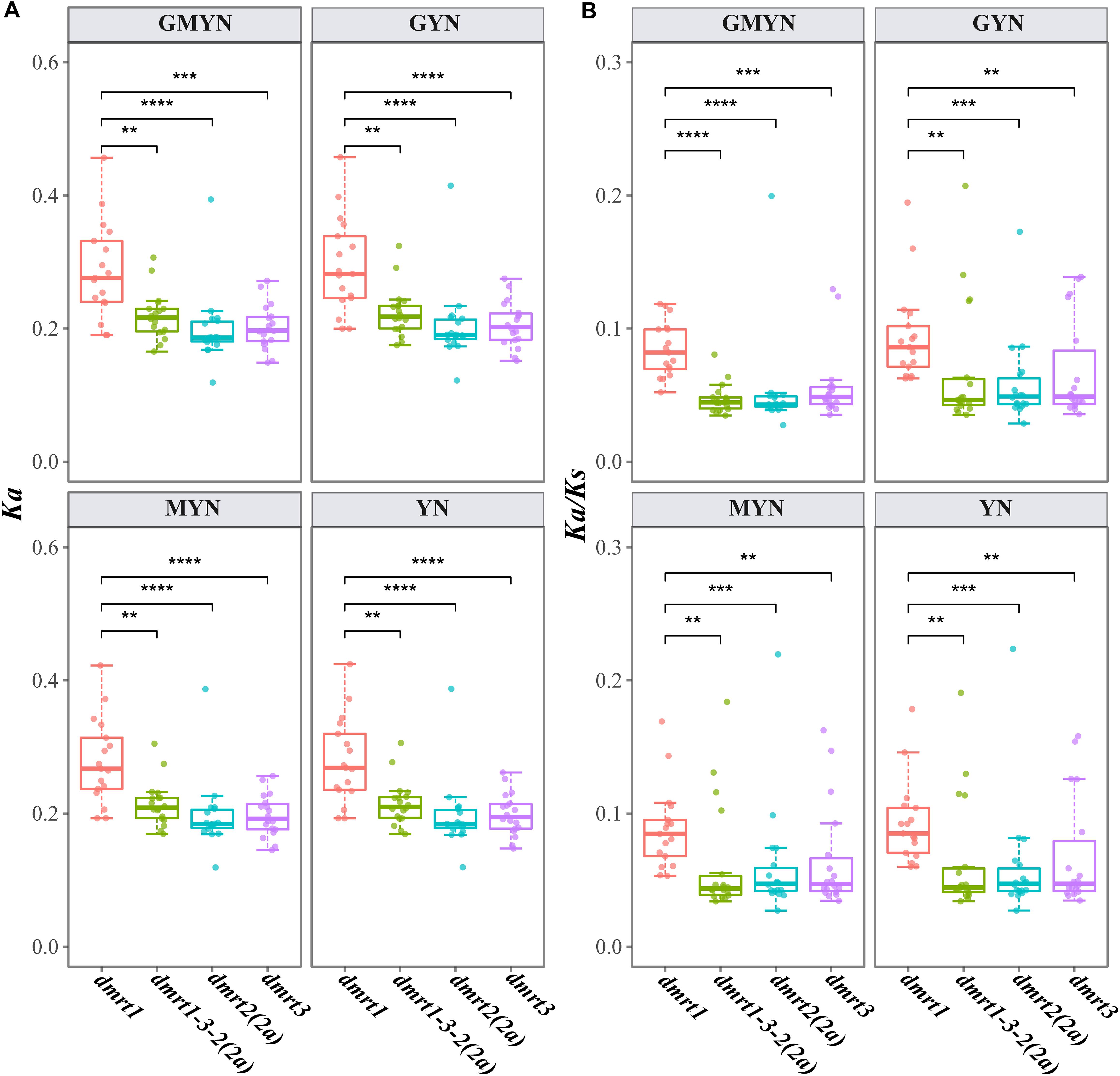

Comparing the Ka and Ka/Ks values using four different methods (gMYN, gYN, MYN, and YN), we found conserved substitution rates in dmrt1, dmrt2(2a), dmrt3, and the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster. In detail, all the mean Ka/Ks values were less than 1 (Figure 3), indicating a purifying selection on these genes. However, dmrt1 showed a higher average Ka/Ks value (0.0900) than dmrt2 (0.0576), dmrt3 (0.0645), and the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster (0.0606), suggesting that the evolution of dmrt1 might be less conservative and thereby may provide more variants for selection.

Figure 3. Ka (A) and Ka/Ks (B) values for the target coding sequences. Paralog genes in the spotted gar were used as the references. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; and ****p < 0.0001 (based on a Wilcoxon test). Four methods, including GMYN, GYN, MYN, and YN, were used.

Conserved Sequences and Regulatory Elements in the Fish dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) Gene Clusters

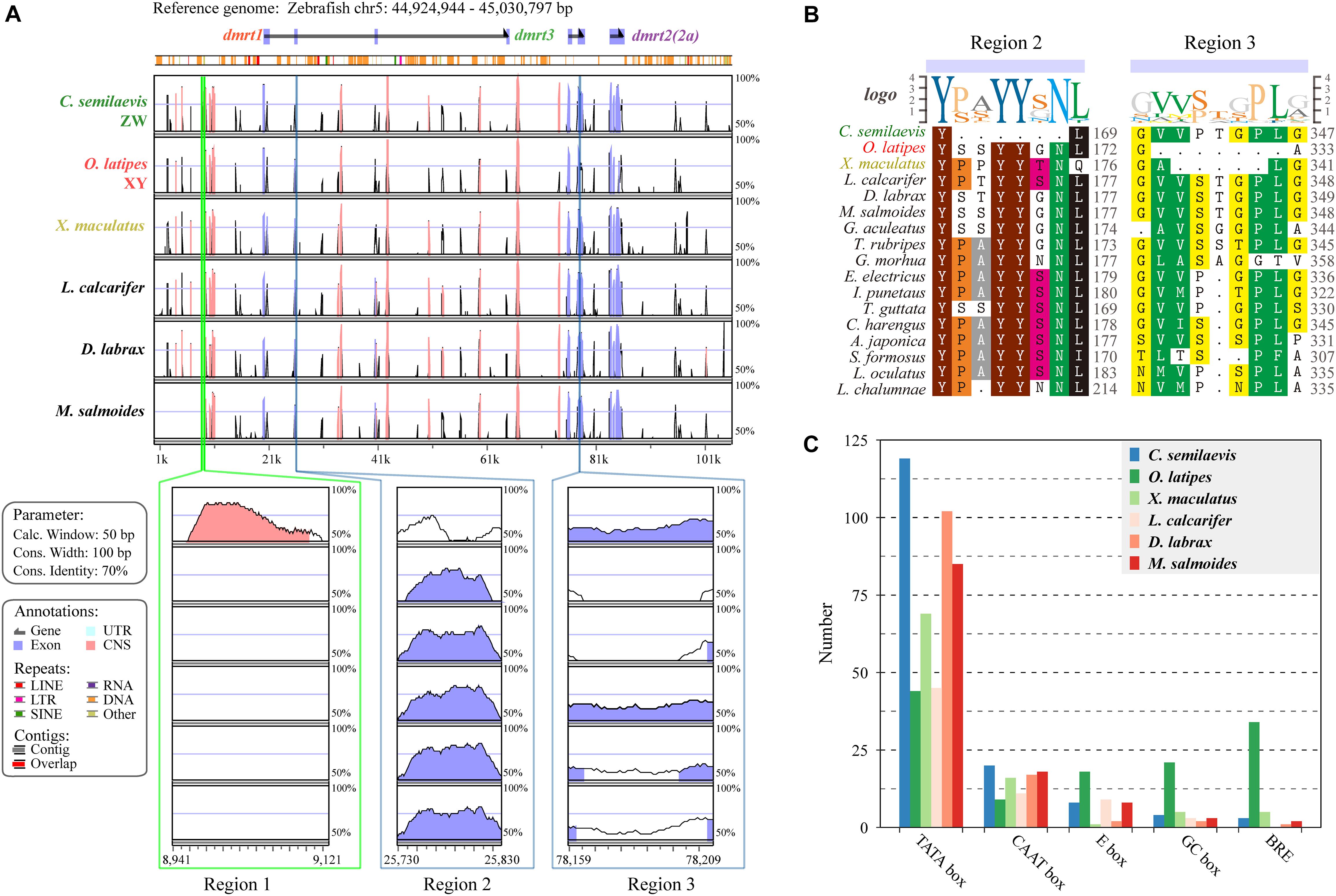

To visualize the genomic conservation, the mVISTA tool was employed to generate a VISTA plot (Figure 4A). We used Chinese tongue sole (ZZ/ZW) (Chen et al., 2014), Japanese medaka (XX/XY) (Kasahara et al., 2007), southern platyfish (males are XY or YY, females are WX, WY, or XX) (Volff and Schartl, 2001), European sea bass (polygenic sex determination system, PSD system) (Vandeputte et al., 2007; Mei and Gui, 2015), Asia sea bass (protandrous hermaphrodite) (Wang et al., 2018), and largemouth bass which was previously reported as WZ/ZZ) (Glennon et al., 2012), whereas our recent analysis combining genomic map, ddRAD-Seq and sex-reversal experiments suggests a XX/XY sex determination system (data unpublished),, to evaluate regulatory elements and genomic sequence changes in the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster with 20-kb upstream/downstream regions in various sex-determination systems.

Figure 4. Species variances of the regulatory regions in the dmrt1-dmrt3-dmrt2(2a) gene cluster. (A) A VISTA plot of the dmrt1-dmrt3-dmrt2(2a) gene clusters among six examined fish species. Peaks of similarity in pair-wise sequence alignments between zebrafish (D. rerio) are compared with Chinese tongue sole (C. semilaevis), Japanese medaka (O. latipes), southern platyfish (X. maculatus), Asian sea bass (L. calcarifer), European sea bass (D. labrax), and largemouth bass (M. salmoides). Blue peaks represent coding exons and pink peaks denote non-coding sequences. The horizontal axis shows relative positions in the zebrafish genomic sequence, whereas the vertical axis indicates percentage of identity (50–100%). Three distinct regions, named as Region 1, Region 2, and Region 3, were identified. (B) Protein sequence alignments of the Regions 2 and 3 in 17 examined fish species. (C) Numbers of different regulatory elements in six representative fish species. Additional details regarding the sequences of each regulatory element are provided in Supplementary Table S4.

Overall, a similar conservation pattern in both coding and non-coding sequences was observed. Comparisons of these six fish species along with zebrafish showed considerable homology within and between these dmrt genes. We also identified three regions with remarkable diversity among these fish (lower panels in Figure 4A). Region 1 covers 207 bp located at the 11-kb upstream region of the dmrt1 gene and contains nine TATA boxes (63 bp), which only exists in Chinese tongue sole. Region 2 is located in the third exon of dmrt1 with 18-bp missing in Chinese tongue sole. Comparing the protein sequences of tongue sole and other fish species, we determined that six amino acids (-P/S-A/S/T/P-YY-S/G/N-N-) were missing (Figure 4B). Region 3, located in the second exon of dmrt3, shows a 21-nucleotide (nt) deletion in Japanese medaka and a 15-nt deletion in southern platfish (Figure 4B).

In the examined six species, TATA box represents the main regulatory element. In Chinese tongue sole, TATA boxes are much more frequent than in other fish, however, markedly fewer E boxes, GC boxes, and B recognition elements (BREs) are present in Japanese medaka than in other species (Figure 4C).

Synteny of Other dmrt Genes [Excluding dmrt1, dmrt2(2a), and dmrt3] in Fish Genomes

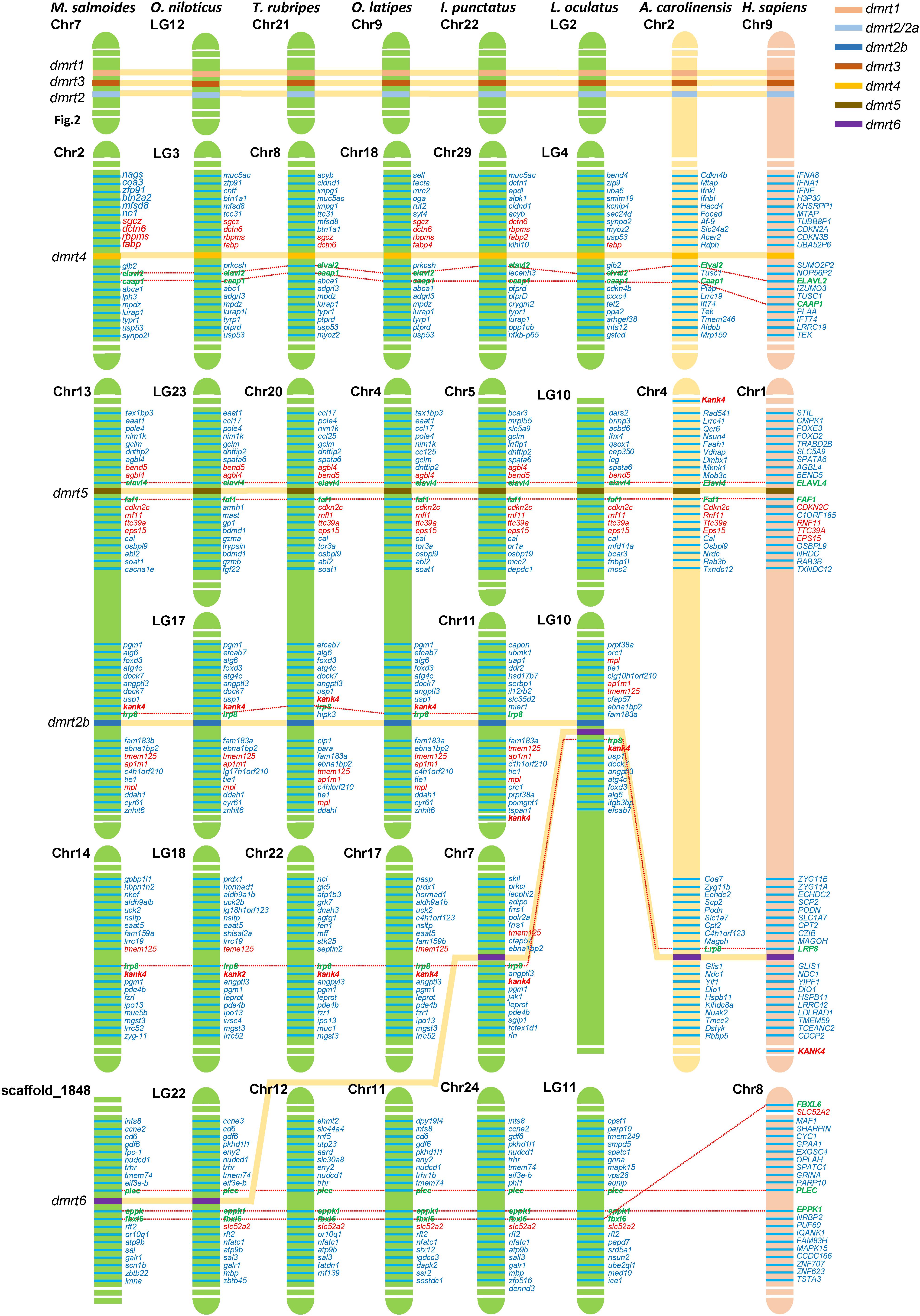

Based on the whole-genome sequence of largemouth bass and other eight representative vertebrate species (including O. niloticus, T. rubripes, O. latipes, I. punctatus, L. oculatus, A. carolinensis, and H. sapiens) obtained from NCBI, we performed a synteny analysis of four dmrt genes, including dmrt2b, dmrt4, dmrt5, and dmrt6. The results (Figure 5) indicated that among these fish species, the KN motif and ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein 4 (kank4) and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 8 (lrp8) genes in the upstream of dmrt2b were conserved. The ELAV-like protein 2 (elavl2) and caspase activity and apoptosis inhibitor 1 (caap1) genes in the downstream of dmrt4, and the elavl4 and FAS-associated factor 1 (faf1) genes in the downstream of dmrt5 were also conserved, which is consistent with the findings in reptiles and humans. This suggests that dmrt2b, dmrt4, and dmrt5 were relatively conserved during the evolutionary process.

Figure 5. Synteny of dmrt genes in various fish species. The synteny analyses were performed in eight vertebrate species (M. salmoides, O. niloticus, T. rubripes, O. latipes, I. punctatus, L. oculatus, A. carolinensis, and H. sapiens). Chr., chromosome; LG, linkage group. The most conserved surrounding genes of dmrt genes were shown in green and bold fonts. The most conserved were shown in red fonts.

Although dmrt6 was lost in most fish species including T. rubripes and O. latipes, in L. oculatus and I. punctatus, lrp8 was present in the upstream of dmrt6, which is consistent with higher vertebrates; whereas in M. salmoides and O. niloticus, dmrt6 was located between the conserved plectin (plec) and epiplakin-F-box/LRR-repeat protein 6 (eppk1–fbxl6) genes (see more details in Figure 5).

Discussion

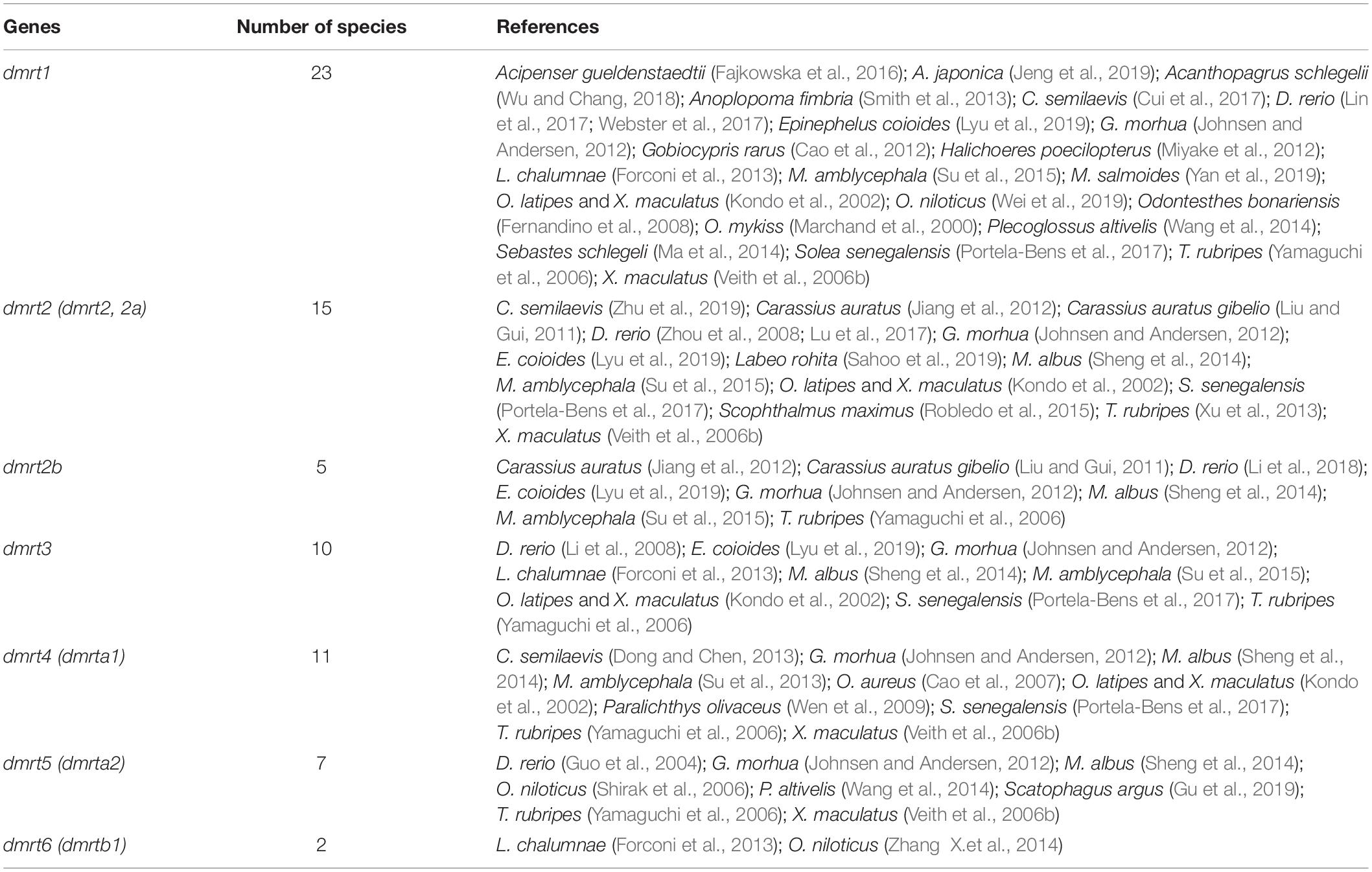

Fish are the oldest and most diverse group among vertebrates, containing about 32,000 species and accounting for more than half of the vertebrate species. Fish have undergone a long history of emergence, development, and evolution. The increasing amount of fish genomic information provides an important resource for studying the evolution, structure, and function of key genes through comparative genomics analysis. Seven dmrt genes have been identified in fish to date, including dmrt1–6 and dmrt2b. dmrt genes have also been reported in more than 30 fish species and a number of functional studies have been performed to reveal that regardless of the sex determination mechanism, the majority of fish dmrt genes (Table 3) are related to sexual development (Li et al., 2008, 2018; Liu et al., 2009; Herpin and Schartl, 2011; Yoshizawa et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2013). However, the phylogenetics of the dmrt gene family in fish have not yet been reported.

To obtain a better understanding of the functional diversification of this gene family, we therefore examined dmrt gene complements from the whole genome sequences of 17 representative fish species representing 10 various superorders and several non-fish outgroups. The evolutionary relationships of the dmrt genes in fish were subsequently examined using both phylogenetic and synteny analyses.

Similarities and Variances of the dmrt Gene Family Members in Various Fish Species

Zhou et al. (2008) showed that unlike mammals and other groups that only harbored one dmrt2, zebrafish carries a second paralog of dmrt2(2a), dmrt2b, which was subsequently identified in many other fish species (Zhou et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Su et al., 2015; Lyu et al., 2019). The 17 representative fish species analyzed in the present study belong to Actinopterygii, with the exception of coelacanth L. chalumnae that belongs to Sarcopterygii. Among the 16 actinopterygians, 14 harbored the two paralogs of dmrt2 (dmrt2a and dmrt2b), however, dmrt6, which is commonly found in mammals and other groups, was only identified in four actinopterygians including M. salmoides and the sarcopterygian L. chalumnae.

Among the 17 fish species, only A. japonica and G. morhua carried dmrt2a alone and lacked dmrt6. L. chalumnae only had one dmrt2 (2a) and one dmrt6, similar to higher vertebrates. A search through the database revealed that two other sarcopterygians (Protopterus annectens and Latimeria menadoensis) also only carried one dmrt2a and dmrt6 (see more details in Supplementary Table S2; Forconi et al., 2013; Biscotti et al., 2018). Actinopterygii and Sarcopterygii are two relatively independent evolutionary branches of fish. Sarcopterygii is a side-branch in the evolution of fish, from which tetrapods evolved (Nelson et al., 2016). Therefore, the characteristics of the dmrt family genes in Sarcopterygii are more similar to those of higher vertebrates.

Based on the cross-species comparisons of dmrt family genes and copy numbers, we found that some of the dmrt genes were duplicated in S. salar and A. japonica (S. salar: dmrt2, 3, 5; A. japonica: dmrt1–3; see Table 1). Lien et al. (2016) suggested that S. salar is a typical tetraploid teleost that had experienced a salmonid-specific genome duplication. The copies of dmrt genes were duplicated in its genome, whereas one copy of dmrt1 and dmrt4 were lost (Lien et al., 2016). Loss of the duplicated gene possibly occurred owing to the salmonid-specific genome duplication event, which may lead to rearrangements of genome sequences, as S. salar has lost numerous syntenic genes in comparison with other teleosts. Similar dmrt duplication and loss were also found in four other fish species (e.g., brown trout Salmo trutta and Sockeye salmon Oncorhynchus nerka) that belong to the same superorder as S. salar (i.e., Protacanthopterygii; Supplementary Table S5). In addition, the copy number of dmrt1 and dmrt3 is doubled in A. japonica, which is considered to be an uncommon ploidy (2n = 38) of this special teleost (Nomura et al., 2004).

The conservation of fish dmrt1 and dmrt(3–5) sequences is relatively high, all of which containing the highly conserved DM domain and a stable number of exons (majority of dmrt1 contained 5 exons and most dmrt3–5 had 2 exons). Phylogenetic analysis showed that dmrt4 and 5 were clustered into a major branch, indicating that these genes appear to be originated from a common ancestor of dmrt.

To date, the dmrt7 and dmrt8 genes have not been found in fish but only in mammals. In fact, they exist in all mammals, from the lower Monotremata in Prototheria (platypus) (Tsend-Ayush et al., 2009) to Marsupiala in Metatheria (wombat), and to the higher Euarchonta in Eutheria (mouse) (Veith et al., 2006a), thus indicating that both genes were only formed after the evolutionary divergence of mammals from other vertebrates including fish (Veith et al., 2006a).

Apart from dmrt5, which is highly expressed in brain tissue, the other members of the fish dmrt family are highly expressed in the gonads. Specifically, dmrt1, 3, and 6 are highly expressed in the testis (dmrt1: (Guan et al., 2000; Marchand et al., 2000; He et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2005a; Veith et al., 2006b; Yamaguchi et al., 2006; Johnsen et al., 2010; Su et al., 2015); dmrt3:(Yamaguchi et al., 2006; Dong et al., 2010; Sheng et al., 2014; Su et al., 2015); dmrt6: (Forconi et al., 2013; Zhang X.et al., 2014), whereas dmrt2a, 2b, and dmrt4 are expressed in both male and female gonads, with different fish species showing different expression profiles [dmrt2a/b:(Yamaguchi et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2008; Liu and Gui, 2011; Sheng et al., 2014; Su et al., 2015); dmrt4:(Kondo et al., 2002; Veith et al., 2006b; Yamaguchi et al., 2006; Cao et al., 2007; Wen et al., 2009; Dong and Chen, 2013; Sheng et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2019)]. Current studies have shown that fish dmrt family members may mainly be involved in embryonic sex differentiation, gonadal development, and gametogenesis (Herpin and Schartl, 2011; Xu et al., 2013; Zhang X.et al., 2014; Graf et al., 2015), in addition to other functions such as neural development (Li et al., 2008; Lourenco et al., 2010; Yoshizawa et al., 2011).

Similarities and Variances of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) Gene Cluster in Various Fish Genomes

In vertebrate genomes, the dmrt1, dmrt2(2a), and dmrt3 genes are in tandem in the order of dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) (Johnsen and Andersen, 2012). Our phylogenetic analysis based on this dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) cluster confirmed the clustering in fish within the same superorder, thus indicating that the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster is highly conserved in various fish species (Figure 2). Further analysis of the conserved genes flanking this cluster revealed that D. rerio carried 11 neighboring genes, as did I. punctatus and C. harengus. However, other fish species showed partial loss (such as the gc gene), duplication (dapk1 in M. salmoides and ctsla in X. maculatus), and transversion (gas1a in M. salmoides and X. maculatus). This may have been caused by genomic polyploidization events during the evolutionary process of fish (Braasch and Postlethwait, 2012). Despite the large variations in the flanking genes among different fish species, the number and location of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) genes have been stable. Thus, the high conservation of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster in various fish genomes suggests their crucial biological functions in fish.

Among the fish genomes analyzed in this study, the Ka/Ks ratios of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster and the three dmrt genes were less than 0.2, impling that after the examined actinopterygians diverged from L. oculatus, the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster was subjected to relatively strong purification selection in its evolutionary process, whereas its positive selection may have occurred prior to the divergence from L. oculatus. These low Ka/Ks ratios across various fish species indicate that the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) genes are highly conserved during evolution. Occurrence of a non-synonymous substitution would alter the conformation and function of the corresponding protein, thereby affecting any individual’s sex differentiation, which in turn would affect the inheritance of the mutation site by its offspring (Wang D.et al., 2009). Therefore, the high conservation of the dmrt1/2/3 genes across fish suggests that its key role in sex differentiation.

Analysis of the conserved sequences and regulatory elements was performed on the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster of three representative fish genomes with different sex determination systems [i.e., C. semilaevis (ZW) (Chen et al., 2012), O. latipes (XY) (Otake et al., 2006), X. maculatus (WXY) (Schultheis et al., 2009)]. Three distinct regions 1–3 were identified (Figure 4A). C. semilaevis showed 207-bp only exists in Region 1 and 18-bp deletions in Regions 2, respectively, and Region 1 contained nine TATA boxes. O. latipes and X. maculatus showed 21- and 15-bp deletions, respectively, in Region 3. Analysis of the regulatory elements for this gene cluster indicated that the number of TATA boxes in C. semilaevis was higher than that in other fish species (twice of O. latipes), whereas O. latipes had significantly more E box, GC box, and BRE elements than other fish species. Fish with various sex-determination systems showed significant differences in their conserved sequences and regulatory elements, suggesting that the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster may be related to the sex-determination systems in fish. In our recent study, it reveals that M. salmoides is a XY/XX system species (Sun et al., 2020). In conserved sequences analysis of fish dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene clusters, it had much difference in Regions 1–3 between M. salmoides and C. semilaevis (ZW/ZZ). The Region 2 of M. salmoides was more similar to O. latipes (XX/XY). The Region 3 of M. salmoides was similar to D. labrax (PSD) and L. calcarifer (hermaphrodite) (Wang et al., 2018). Therefore, the sex-determination systems of M. salmoides might be preferred to XY/XX system species.

Conserved Synteny of the dmrt Genes in Fish Genomes

The synteny analysis performed in this study showed that apart from dmrt6, all other six dmrt genes in the fish dmrt gene family (dmrt1, dmrt2a, dmrt2b, and dmrt3–5) were relatively conserved. Fish dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) clusters are located in tandem in genomes, which is consistent with higher vertebrates. Fish dmrt4 is usually located on a different chromosome from the cluster, and the downstream elavl2 gene is conserved. In contrast, dmrt4 is located on the same chromosome as this dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) cluster in higher vertebrates, but the downstream elavl2 gene is also conserved. Fish dmrt5 gene is the same as that in higher vertebrates, in which the upstream and downstream elavl4 and faf1 genes are also conserved. dmrt2b gene can be found in most fish species, and the upstream kank4 and lrp8 genes are conserved. The dmrt6 gene is lost in most fish genomes. However, in L. oculatus and I. punctatus, dmrt6 is conserved with downstream lrp8, which is consistent with higher vertebrates, however, in M. salmoides and O. niloticus, the dmrt6 gene is located between the conserved plec and eppk1–fbxl6 genes (see Figure 5).

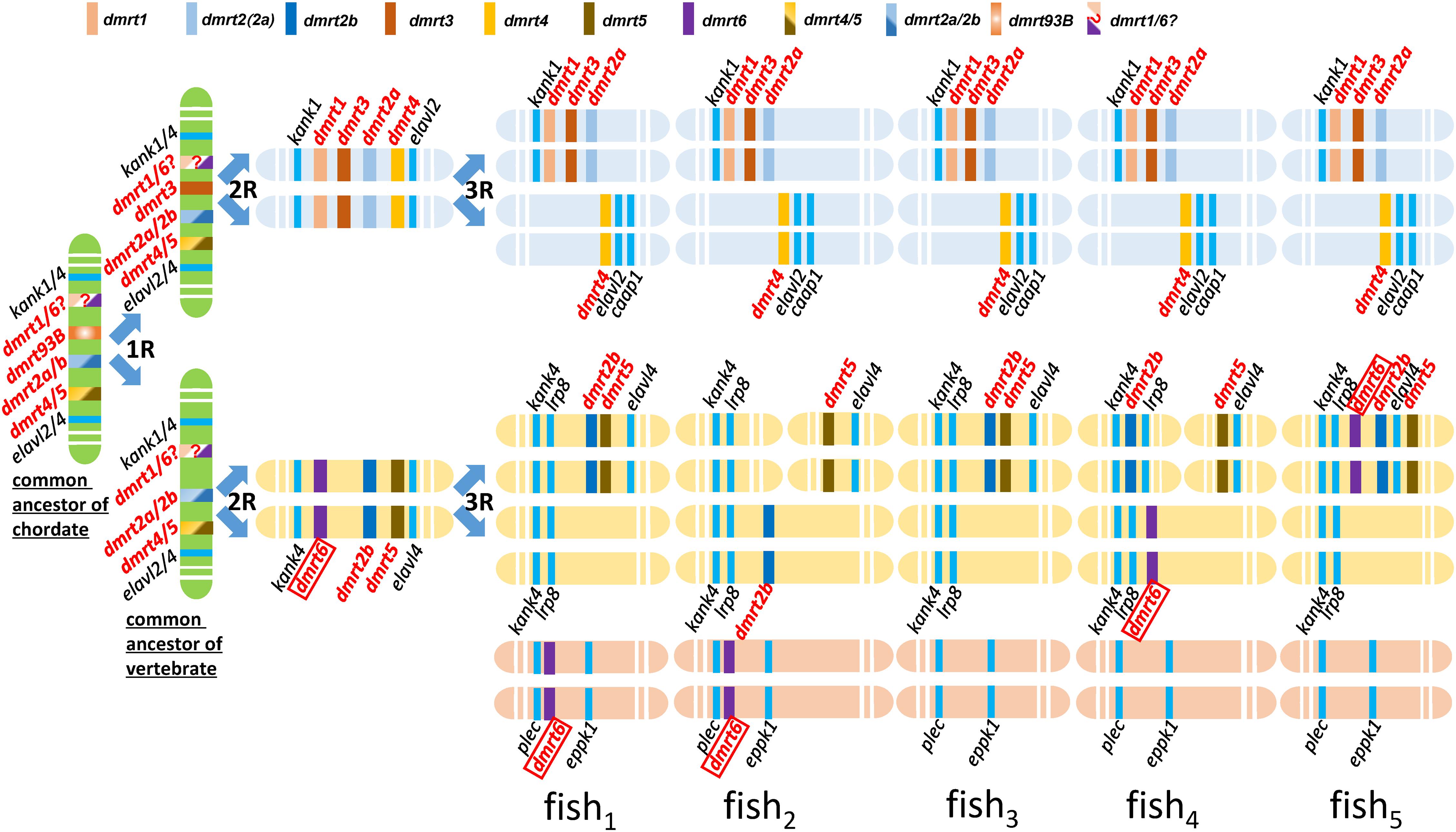

Kondo et al. (2002) was the first report of conserved synteny analysis on the dmrt1–4 genes between fish and human. This study demonstrated that the dmrt1, 2, and 3 genes formed clusters in fish and constituted a part of a large number of genes in this cluster that exhibit conserved synteny between human and fish. Johnsen and Andersen (2012) performed chromosomal synteny analysis on dmrt2a and dmrt2b, and proposed that these genes originated from the second round (2R) of whole genome duplication of the ancestral dmrt2 (Johnsen and Andersen, 2012). In turn, Mawaribuchi et al. (2019) performed phylogenetic cluster analysis of lower bilaterian and higher animal dmrt genes, based on which they speculated that the dmrt3 gene emerged by genome duplication (1R), and dmrt1 and dmrt6 emerged after the 2R genome duplication; they also proposed an evolutionary history for the dmrt family genes in bilateria (Mawaribuchi et al., 2019). Therefore, according to our data coupled with these relevant literatures, we hypothesized evolutionary history of the dmrt genes in fish (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Hypothetical evolutionary history of the dmrt genes in fish through fish-specific (3R) genome duplications. This figure was constructed based on figures in this study. The common ancestor of chordate might possess four ancestral genes, including dmrt4/5, dmrt2a/2b, dmrt93B, and dmrt1/6. A common ancestor of vertebrata may have possessed four dmrt family genes, dmrt1/6, dmrt2a/2b, dmrt3, and dmrt4/5. The syntenies of kank1-dmrt1-dmrt3-dmrt2a, dmrt4-elavl2-caap1, kank4-lrp8-dmrt2b, and dmrt5- elavl4 are conserved after three rounds of whole genome duplication in the ancestral vertebrates. dmrt6 is lost in most fish species.

Firstly, we propose that dmrt genes exist in various fish species through the fish-specific (3R) genome duplications (Johnsen and Andersen, 2012). Secondly, we propose that dmrt3 might originate from dmrt93B and emerged by genome duplication (1R). According to our phylogenic tree of the dmrt family in vertebrates (Figure 1B), in addition to the conserved genes flanking dmrt1 and dmrt6 (kank1/4) (Figure 5), we propose that dmrt1 and dmrt6 might originate from the same ancestral dmrt (labeled with dmrt1/6? in Figure 6) and they emerged after genome duplication (2R). Thirdly, (1) we propose that the common ancestor of chordates might have four ancestral dmrt genes (dmrt4/5, dmrt2a/2b, dmrt93B, and dmrt1/6), and two ancestral surrounding genes (kank1/4 and elval2/4). (2) A common ancestor of vertebrata might have possessed four dmrt family genes, inclduing dmrt1/6, dmrt2a/2b, dmrt3, and dmrt4/5. The four dmrt family genes and their conserved surrounding genes are distributed in tandem on two pairs of chromosomes, specifically kank1/4–dmrt1/6–dmrt3–dmrt2a/2b–dmrt4/5–elalv2/4 and kank1/4–dmrt1/6–dmrt2a/2b–dmrt4/5–elalv2/4. (3) After three rounds (3R) of whole genome duplication, the syntenies of kank1–dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2a, dmrt4–elavl2–caap1, kank4–lrp8–dmrt2b, and dmrt5–elavl4 are conserved in fish. (4) dmrt6 is lost in most fish species, although some retained it with downstream kank4–lrp8, or it was recombined to other chromosomes with a location between plec and eppk1.

We should note that our present study has several limitations. First, although fish are the most numerous vertebrates on earth, whole genome sequences are currently available for only a small fraction of fish. In this study, 17 representative fish species from 10 superorders were selected for analysis; however, the number and coverage of species was still insufficient and may have limited the generalizability of our results. Second, this study was based on fish species with known genome sequences, which may have affected the accuracy of data analysis because genome assembly techniques and quality vary significantly among species. For example, since coelacanth genomes are not assembled to the chromosomal level, our syntenic analysis of their genes is affected. Third, it is expected that as sequencing coverage and quality increase for fish genomes, future studies will be able to confirm and expand findings and generalizability from the present study.

In this study, we applied bioinformatics methods to perform phylogenetic and synteny analyses on dmrt genes in 17 fish speices. (1) All the examined fish species have dmrt1–5 and most fish species harbored two dmrt2 paralogs (dmrt2a and dmrt2b). Phyletic evolution and structure of dmrt1∼5 and dmrt2b genes were relatively conserved in most of fish. The dmrt6 gene is lost in most fish genomes and less conservative. (2) Purifying selections on the dmrt1, dmrt2(2a), dmrt3, and the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster were observed. (3) Fish with various sex-determination systems have the similar genomic conservation patterns of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster. dmrt2b, dmrt4, and dmrt5 were also relatively conserved during the evolutionary process. The high conservation of the dmrt1–dmrt3–dmrt2(2a) gene cluster in various fish genomes suggests their crucial biological functions while various dmrt family members and sequences across fish species suggest different biological roles during evolution.

Furthermore, we hypothesized the evolutionary history of the dmrt genes in fish after fish-specific genome duplication(s). Moreover, here raised a series of new questions during the course of our data analysis. For example, in terms of evolutionary analysis, whether dmrt2b is homologous and functionally similar to a specific dmrt in higher animals, or does fish dmrt6 have similar functions to mammalian counterpart. We anticipate that these gene trees will help to place current dmrt research in a proper phylogenomic context. Our present study will provide a solid molecular basis for functional research on the fish dmrt family and may in particular serve as genetic reference for in-depth phylogenomics studies.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

XY and QS conceived and designed the project and revised the manuscript. JD and JL performed the genomic investigations and wrote the manuscript. JH, CFS, YT, NY, CXS, XS, and SY participated in discussion and figure preparation. All authors read and approve the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-46), Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (2020TD23), Special Fund for Scientific Research in Public Welfare and Capacity Building of Guangdong Province (NO. 2017A030303002), Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (NO. 2017HY-XKQ0208) and the Youth Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 3190235).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewers JM and ZS declared a shared affiliation, with no collaboration, with one of the authors CFS, to the handling editor at the time of review.

Acknowledgments

We thank Editage (https://www.editage.cn/) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2020.563947/full#supplementary-material

References

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., and Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Andersson, L. S., Larhammar, M., Memic, F., Wootz, H., Schwochow, D., Rubin, C. J., et al. (2012). Mutations in DMRT3 affect locomotion in horses and spinal circuit function in mice. Nature 488, 642–646. doi: 10.1038/nature11399

Balciuniene, J., Bardwell, V. J., and Zarkower, D. (2006). Mice mutant in the DM domain gene Dmrt4 are viable and fertile but have polyovular follicles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 8984–8991. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00959-06

Birney, E., Clamp, M., and Durbin, R. (2004). GeneWise and genomewise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.1865504

Biscotti, M. A., Adolfi, M. C., Barucca, M., Forconi, M., Pallavicini, A., Gerdol, M., et al. (2018). A comparative view on sex differentiation and gametogenesis genes in lungfish and coelacanths. Genome Biol. Evol. 10, 1430–1444. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy101

Braasch, I., and Postlethwait, J. H. (2012). “Polyploidy in fish and the teleost genome duplication,” in Polyploidy and Genome Evolution, eds P. S. Soltis and D. E. Soltis (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg), 341–383. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-31442-1_17

Burtis, K. C., and Baker, B. S. (1989). Drosophila doublesex gene controls somatic sexual differentiation by producing alternatively spliced mRNAs encoding related sex-specific polypeptides. Cell 56, 997–1010. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90633-8

Cao, J., Cao, Z., and Wu, T. (2007). Generation of antibodies against DMRT1 and DMRT4 of Oreochromis aurea and analysis of their expression profile in Oreochromis aurea tissues. J. Genet. Genomics 34, 497–509. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(07)60055-1

Cao, M., Duan, J., Cheng, N., Zhong, X., Wang, Z., Hu, W., et al. (2012). Sexually dimorphic and ontogenetic expression of dmrt1, cyp19a1a and cyp19a1b in Gobiocypris rarus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 162, 303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.03.021

Chen, N. (2004). Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics Chapter 4, Unit4.10. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s05

Chen, S., Zhang, G., Shao, C., Huang, Q., Liu, G., Zhang, P., et al. (2014). Whole-genome sequence of a flatfish provides insights into ZW sex chromosome evolution and adaptation to a benthic lifestyle. Nat. Genet. 46, 253–260. doi: 10.1038/ng.2890

Chen, S. L., Ji, X. S., Shao, C. W., Li, W. L., Yang, J. F., Liang, Z., et al. (2012). Induction of mitogynogenetic diploids and identification of WW super-female using sex-specific SSR markers in half-smooth tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis). Mar. Biotechnol. (NY) 14, 120–128. doi: 10.1007/s10126-011-9395-2

Cui, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, W., Wang, Q., Zhang, N., Lin, F., et al. (2017). Genome editing reveals dmrt1 as an essential male sex-determining gene in Chinese tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis). Sci. Rep. 7:42213. doi: 10.1038/srep42213

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R., and Posada, D. (2011). ProtTest 3: fast selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics 27, 1164–1165. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr088

De Clercq, S., Keruzore, M., Desmaris, E., Pollart, C., Assimacopoulos, S., Preillon, J., et al. (2018). DMRT5 together with DMRT3 directly controls hippocampus development and neocortical area map formation. Cereb. Cortex 28, 493–509. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw384

Dong, X. L., and Chen, S. L. (2013). Molecular cloning and expression analysis of Dmrt4 gene in half-smooth tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis). J. Fish. Sci. China 20, 499–505. doi: 10.3724/sp.j.1118.2013.00499

Dong, X. L., Chen, S. L., and Ji, X. S. (2010). Molecular cloning and expression analysis of Dmrt3 gene in half-smooth tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis). J. Fish. China 34, 829–835. doi: 10.1007/s10695-018-0472-6

El-Mogharbel, N., Wakefield, M., Deakin, J. E., Tsend-Ayush, E., Grutzner, F., Alsop, A., et al. (2007). DMRT gene cluster analysis in the platypus: new insights into genomic organization and regulatory regions. Genomics 89, 10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.07.017

Erdman, S. E., and Burtis, K. C. (1993). The Drosophila doublesex proteins share a novel zinc finger related DNA binding domain. EMBO J. 12, 527–535. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05684.x

Fajkowska, M., Rzepkowska, M., Adamek, D., Ostaszewska, T., and Szczepkowski, M. (2016). Expression of dmrt1 and vtg genes during gonad formation, differentiation and early maturation in cultured Russian sturgeon Acipenser gueldenstaedtii. J. Fish. Biol. 89, 1441–1449. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12992

Fernandino, J. I., Hattori, R. S., Shinoda, T., Kimura, H., Strobl-Mazzulla, P. H., Strussmann, C. A., et al. (2008). Dimorphic expression of dmrt1 and cyp19a1 (ovarian aromatase) during early gonadal development in pejerrey, Odontesthes bonariensis. Sex Dev. 2, 316–324. doi: 10.1159/000195681

Forconi, M., Canapa, A., Barucca, M., Biscotti, M. A., Capriglione, T., Buonocore, F., et al. (2013). Characterization of sex determination and sex differentiation genes in Latimeria. PLoS One 8:e56006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056006

Frazer, K. A., Pachter, L., Poliakov, A., Rubin, E. M., and Dubchak, I. (2004). VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W273–W279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458

Glennon, R., Gomelsky, B., Schneider, K., Kelly, A., and Haukenes, A. (2012). Evidence of female heterogamety in largemouth bass, based on sex ratio of gynogenetic progeny. North Am. J. Aquac. 74, 537–540. doi: 10.1080/15222055.2012.700906

Graf, M., Teo Qi-Wen, E. R., Sarusie, M. V., Rajaei, F., and Winkler, C. (2015). Dmrt5 controls corticotrope and gonadotrope differentiation in the zebrafish pituitary. Mol. Endocrinol. 29, 187–199. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1176

Gu, H. T., Liu, Q. Q., Situ, J. X., Jiang, D. N., Chen, H. P., Wu, T. L., et al. (2019). Cloning and expression of Dmrt5 gene in Scatophagus argus. J. Hainan Trop. Ocean Univ. 26, 9–15.

Guan, G., Kobayashi, T., and Nagahama, Y. (2000). Sexually dimorphic expression of two types of DM (Doublesex/Mab-3)-domain genes in a teleost fish, the Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 272, 662–666. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2840

Guo, Y., Cheng, H., Huang, X., Gao, S., Yu, H., and Zhou, R. (2005). Gene structure, multiple alternative splicing, and expression in gonads of zebrafish Dmrt1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 330, 950–957. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.066

Guo, Y., Li, Q., Gao, S., Zhou, X., He, Y., Shang, X., et al. (2004). Molecular cloning, characterization, and expression in brain and gonad of Dmrt5 of zebrafish. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324, 569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.085

He, C. L., Du, J. L., Wu, G. C., Lee, Y. H., Sun, L. T., and Chang, C. F. (2003). Differential Dmrt1 transcripts in gonads of the protandrous black porgy, Acanthopagrus schlegeli. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 101, 309–313. doi: 10.1159/000074354

He, Z., Zhang, H., Gao, S., Lercher, M. J., Chen, W. H., and Hu, S. (2016). Evolview v2: an online visualization and management tool for customized and annotated phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W236–W241. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw370

Herpin, A., and Schartl, M. (2011). Dmrt1 genes at the crossroads: a widespread and central class of sexual development factors in fish. FEBS J. 278, 1010–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08030.x

Hodgkin, J. (2002). The remarkable ubiquity of DM domain factors as regulators of sexual phenotype: ancestry or aptitude? Genes Dev. 16, 2322–2326. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025502

Hong, C. S., Park, B. Y., and Saint-Jeannet, J. P. (2007). The function of Dmrt genes in vertebrate development: it is not just about sex. Dev. Biol. 310, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.035

Huang, X., Guo, Y., Shui, Y., Gao, S., Yu, H., Cheng, H., et al. (2005a). Multiple alternative splicing and differential expression of dmrt1 during gonad transformation of the rice field eel. Biol. Reprod. 73, 1017–1024. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.041871

Huang, X., Hong, C. S., O’Donnell, M., and Saint-Jeannet, J. P. (2005b). The doublesex-related gene, XDmrt4, is required for neurogenesis in the olfactory system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 11349–11354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505106102

Jeng, S. R., Wu, G. C., Yueh, W. S., Kuo, S. F., Dufour, S., and Chang, C. F. (2019). Dmrt1 (doublesex and mab-3-related transcription factor 1) expression during gonadal development and spermatogenesis in the Japanese eel. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 279, 154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2019.03.012

Jiang, D. N., Peng, Y. Q., Mustapha, U. F., Gu, H. T., Deng, S. P., Chen, H. P., et al. (2019). molecular cloning and expression profile of Dmrt4 in spotted scat (Scatophagus argus). J. Guangdong Ocean Univ. 39, 7–13.

Jiang, S., Chen, X. W., Shi, Z. Y., and Li, Q. (2012). Expression of Dmrt2 gene in Carassius auratus. J. Shanghai Ocean Univ. 21, 701–708.

Johnsen, H., and Andersen, O. (2012). Sex dimorphic expression of five dmrt genes identified in the Atlantic cod genome. The fish-specific dmrt2b diverged from dmrt2a before the fish whole-genome duplication. Gene 505, 221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.06.021

Johnsen, H., Seppola, M., Torgersen, J. S., Delghandi, M., and Andersen, O. (2010). Sexually dimorphic expression of dmrt1 in immature and mature Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 156, 197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2010.03.009

Kasahara, M., Naruse, K., Sasaki, S., Nakatani, Y., Qu, W., Ahsan, B., et al. (2007). The medaka draft genome and insights into vertebrate genome evolution. Nature 447, 714–719. doi: 10.1038/nature05846

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K., and Miyata, T. (2002). MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436

Kawamata, M., and Nishimori, K. (2006). Mice deficient in Dmrt7 show infertility with spermatogenic arrest at pachytene stage. FEBS Lett. 580, 6442–6446. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.066

Kim, S., Kettlewell, J. R., Anderson, R. C., Bardwell, V. J., and Zarkower, D. (2003). Sexually dimorphic expression of multiple doublesex-related genes in the embryonic mouse gonad. Gene Expr. Patterns 3, 77–82. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(02)00071-6

Kobayashi, T., Kajiura-Kobayashi, H., Guan, G., and Nagahama, Y. (2008). Sexual dimorphic expression of DMRT1 and Sox9a during gonadal differentiation and hormone-induced sex reversal in the teleost fish Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Dev. Dyn. 237, 297–306. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21409

Kobayashi, T., Matsuda, M., Kajiura-Kobayashi, H., Suzuki, A., Saito, N., Nakamoto, M., et al. (2004). Two DM domain genes, DMY and DMRT1, involved in testicular differentiation and development in the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Dev. Dyn. 231, 518–526. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20158

Kondo, M., Froschauer, A., Kitano, A., Nanda, I., Hornung, U., Volff, J. N., et al. (2002). Molecular cloning and characterization of DMRT genes from the medaka Oryzias latipes and the platyfish Xiphophorus maculatus. Gene 295, 213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00692-3

Konno, D., Iwashita, M., Satoh, Y., Momiyama, A., Abe, T., Kiyonari, H., et al. (2012). The mammalian DM domain transcription factor Dmrta2 is required for early embryonic development of the cerebral cortex. PLoS One 7:e46577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046577

Li, L., Mao, A., Wang, P., Ning, G., Cao, Y., and Wang, Q. (2018). Endodermal pouch-expressed dmrt2b is important for pharyngeal cartilage formation. Biol Open 7:bio035444. doi: 10.1242/bio.035444

Li, Q., Zhou, X., Guo, Y., Shang, X., Chen, H., Lu, H., et al. (2008). Nuclear localization, DNA binding and restricted expression in neural and germ cells of zebrafish Dmrt3. Biol. Cell 100, 453–463. doi: 10.1042/BC20070114

Lien, S., Koop, B. F., Sandve, S. R., Miller, J. R., Kent, M. P., Nome, T., et al. (2016). The Atlantic salmon genome provides insights into rediploidization. Nature 533, 200–205. doi: 10.1038/nature17164

Lin, Q., Mei, J., Li, Z., Zhang, X., Zhou, L., and Gui, J. F. (2017). Distinct and cooperative roles of amh and dmrt1 in self-renewal and differentiation of male germ cells in zebrafish. Genetics 207, 1007–1022. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.300274

Liu, S., and Gui, J. F. (2011). Molecular characterization and functional analysis of gibel carp dmrt2b. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 35, 379–383.

Liu, S., Li, Z., and Gui, J. F. (2009). Fish-specific duplicated dmrt2b contributes to a divergent function through Hedgehog pathway and maintains left-right asymmetry establishment function. PLoS One 4:e7261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007261

Lourenco, R., Lopes, S. S., and Saude, L. (2010). Left-right function of dmrt2 genes is not conserved between zebrafish and mouse. PLoS One 5:e14438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014438

Loytynoja, A., and Goldman, N. (2005). An algorithm for progressive multiple alignment of sequences with insertions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10557–10562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409137102

Lu, C., Wu, J., Xiong, S., Zhang, X., Zhang, J., and Mei, J. (2017). MicroRNA-203a regulates fast muscle differentiation by targeting dmrt2a in zebrafish embryos. Gene 625, 49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.05.012

Lyu, Q., Hu, J., Yang, X., Liu, X., Chen, Y., Xiao, L., et al. (2019). Expression profiles of dmrts and foxls during gonadal development and sex reversal induced by 17alpha-methyltestosterone in the orange-spotted grouper. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 274, 26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2018.12.014

Ma, L., Wang, W., Yang, X., Jiang, J., Song, H., Jiang, H., et al. (2014). Characterization of the Dmrt1 gene in the black rockfish Sebastes schlegeli revealed a remarkable sex-dimorphic expression. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 40, 1263–1274. doi: 10.1007/s10695-014-9921-z

Marchand, O., Govoroun, M., D’Cotta, H., McMeel, O., Lareyre, J. J., Bernot, A., et al. (2000). DMRT1 expression during gonadal differentiation and spermatogenesis in the rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1493, 180–187. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00186-x

Matson, C. K., Murphy, M. W., Sarver, A. L., Griswold, M. D., Bardwell, V. J., and Zarkower, D. (2011). DMRT1 prevents female reprogramming in the postnatal mammalian testis. Nature 476, 101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature10239

Matson, C. K., and Zarkower, D. (2012). Sex and the singular DM domain: insights into sexual regulation, evolution and plasticity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 163–174. doi: 10.1038/nrg3161

Mawaribuchi, S., Ito, Y., and Ito, M. (2019). Independent evolution for sex determination and differentiation in the DMRT family in animals. Biol. Open 8:bio041962. doi: 10.1242/bio.041962

Mei, J., and Gui, J. F. (2015). Genetic basis and biotechnological manipulation of sexual dimorphism and sex determination in fish. Sci. China Life Sci. 58, 124–136. doi: 10.1007/s11427-014-4797-9

Meng, A., Moore, B., Tang, H., Yuan, B., and Lin, S. (1999). A Drosophila doublesex-related gene, terra, is involved in somitogenesis in vertebrates. Development 126, 1259–1268.

Miyake, Y., Sakai, Y., and Kuniyoshi, H. (2012). Molecular cloning and expression profile of sex-specific genes, Figla and Dmrt1, in the protogynous hermaphroditic fish, Halichoeres poecilopterus. Zoolog. Sci. 29, 690–701. doi: 10.2108/zsj.29.690

Moniot, B., Berta, P., Scherer, G., Sudbeck, P., and Poulat, F. (2000). Male specific expression suggests role of DMRT1 in human sex determination. Mech. Dev. 91, 323–325. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00267-1

Muralidharan, B., Keruzore, M., Pradhan, S. J., Roy, B., Shetty, A. S., Kinare, V., et al. (2017). Dmrt5, a novel neurogenic factor, reciprocally regulates Lhx2 to control the neuron-glia cell-fate switch in the developing hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 37, 11245–11254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1535-17.2017

Nomura, K., Nakajima, J.-I., Ohta, H., Kagawa, H., Tanaka, H., Unuma, T., et al. (2004). Induction of triploidy by heat shock in the Japanese eel Anguilla japonica. Fish. Sci. 70, 247–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-2906.2003.00798.x

Otake, H., Shinomiya, A., Matsuda, M., Hamaguchi, S., and Sakaizumi, M. (2006). Wild-derived XY sex-reversal mutants in the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Genetics 173, 2083–2090. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.058941

Ottolenghi, C., Fellous, M., Barbieri, M., and McElreavey, K. (2002). Novel paralogy relations among human chromosomes support a link between the phylogeny of doublesex-related genes and the evolution of sex determination. Genomics 79, 333–343. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6711

Panara, V., Budd, G. E., and Janssen, R. (2019). Phylogenetic analysis and embryonic expression of panarthropod Dmrt genes. Front. Zool. 16:23. doi: 10.1186/s12983-019-0322-0

Portela-Bens, S., Merlo, M. A., Rodriguez, M. E., Cross, I., Manchado, M., Kosyakova, N., et al. (2017). Integrated gene mapping and synteny studies give insights into the evolution of a sex proto-chromosome in Solea senegalensis. Chromosoma 126, 261–277. doi: 10.1007/s00412-016-0589-2

Raymond, C. S., Shamu, C. E., Shen, M. M., Seifert, K. J., Hirsch, B., Hodgkin, J., et al. (1998). Evidence for evolutionary conservation of sex-determining genes. Nature 391, 691–695. doi: 10.1038/35618

Robledo, D., Ribas, L., Cal, R., Sanchez, L., Piferrer, F., Martinez, P., et al. (2015). Gene expression analysis at the onset of sex differentiation in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). BMC Genomics 16:973. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2142-8

Ronquist, F., Teslenko, M., van der Mark, P., Ayres, D. L., Darling, A., Hohna, S., et al. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029

Sahoo, L., Sahoo, S., Mohanty, M., Sankar, M., Dixit, S., Das, P., et al. (2019). Molecular characterization, computational analysis and expression profiling of Dmrt1 gene in Indian major carp, Labeo rohita (Hamilton 1822). Anim. Biotechnol. 1–14. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2019.1707683

Saude, L., Lourenco, R., Goncalves, A., and Palmeirim, I. (2005). terra is a left-right asymmetry gene required for left-right synchronization of the segmentation clock. Nat. Cell. Biol. 7, 918–920. doi: 10.1038/ncb1294

Schultheis, C., Bohne, A., Schartl, M., Volff, J. N., and Galiana-Arnoux, D. (2009). Sex determination diversity and sex chromosome evolution in poeciliid fish. Sex. Dev. 3, 68–77. doi: 10.1159/000223072

Seo, K. W., Wang, Y., Kokubo, H., Kettlewell, J. R., Zarkower, D. A., and Johnson, R. L. (2006). Targeted disruption of the DM domain containing transcription factor Dmrt2 reveals an essential role in somite patterning. Dev. Biol. 290, 200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.027

Sheng, Y., Chen, B., Zhang, L., Luo, M., Cheng, H., and Zhou, R. (2014). Identification of Dmrt genes and their up-regulation during gonad transformation in the swamp eel (Monopterus albus). Mol. Biol. Rep. 41, 1237–1245. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2968-6

Shirak, A., Seroussi, E., Cnaani, A., Howe, A. E., Domokhovsky, R., Zilberman, N., et al. (2006). Amh and Dmrta2 genes map to tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) linkage group 23 within quantitative trait locus regions for sex determination. Genetics 174, 1573–1581. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.059030

Slater, G. S., and Birney, E. (2005). Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 6:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-31

Smith, C. A., Hurley, T. M., McClive, P. J., and Sinclair, A. H. (2002). Restricted expression of DMRT3 in chicken and mouse embryos. Mech. Dev. 119(Suppl. 1), S73–S76. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00094-7

Smith, E. K., Guzman, J. M., and Luckenbach, J. A. (2013). Molecular cloning, characterization, and sexually dimorphic expression of five major sex differentiation-related genes in a Scorpaeniform fish, sablefish (Anoplopoma fimbria). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 165, 125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2013.03.011

Su, L., Zhou, F., Ding, Z., Gao, Z., Wen, J., Wei, W., et al. (2015). Transcriptional variants of Dmrt1 and expression of four Dmrt genes in the blunt snout bream, Megalobrama amblycephala. Gene 573, 205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.07.044

Su, L. N., Ding, Z. J., Li, H., Zhou, F. J., Wang, W. M., and Liu, H. (2013). Molecular cloning and expression analysis of Dmrt4 gene in Megalobrama amblycephala. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 32, 110–116.

Sun, C., Li, J., Dong, J., Niu, Y., Hu, J., Lian, J., et al. (2020). Chromosome-level genome assembly for the largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides provides insights into adaptation to fresh and brackish water. Mol. Ecol. Resour. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13256 [Epub ahead of print].

Tsend-Ayush, E., Lim, S. L., Pask, A. J., Hamdan, D. D., Renfree, M. B., and Grutzner, F. (2009). Characterisation of ATRX, DMRT1, DMRT7 and WT1 in the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus). Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 21, 985–991. doi: 10.1071/RD09090

Vandeputte, M., Dupont-Nivet, M., Chavanne, H., and Chatain, B. (2007). A polygenic hypothesis for sex determination in the European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax. Genetics 176, 1049–1057. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.072140

Veith, A. M., Klattig, J., Dettai, A., Schmidt, C., Englert, C., and Volff, J. N. (2006a). Male-biased expression of X-chromosomal DM domain-less Dmrt8 genes in the mouse. Genomics 88, 185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.01.003

Veith, A. M., Schafer, M., Kluver, N., Schmidt, C., Schultheis, C., Schartl, M., et al. (2006b). Tissue-specific expression of dmrt genes in embryos and adults of the platyfish Xiphophorus maculatus. Zebrafish 3, 325–337. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2006.3.325

Volff, J. N., and Schartl, M. (2001). Variability of genetic sex determination in poeciliid fishes. Genetica 111, 101–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1013795415808

Volff, J. N., Zarkower, D., Bardwell, V. J., and Schartl, M. (2003). Evolutionary dynamics of the DM domain gene family in metazoans. J. Mol. Evol. 57(Suppl. 1), S241–S249. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-0033-0

Wang, D., Zhang, S., He, F., Zhu, J., Hu, S., and Yu, J. (2009). How do variable substitution rates influence Ka and Ks calculations? Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 7, 116–127. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(08)60040-6

Wang, D. P., Wan, H. L., Zhang, S., and Yu, J. (2009). Gamma-MYN: a new algorithm for estimating Ka and Ks with consideration of variable substitution rates. Biol. Direct. 4:20. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-4-20

Wang, H. (2013). The bioinformatical analysis on DMRT family and possible role of Dmrt4/Dmrt6 in the development of tilapia gonad. Southwest Univ.

Wang, H., Piferrer, F., Chen, S., and Shen, Z. (2018). “Epigenetics of sex determination and differentiation in fish,” in Sex Control in Aquaculture, eds H. P. Wang, F. Piferrer, S. L. Chen, and Z. G. Shen (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 65–83. doi: 10.1002/9781119127291.ch3

Wang, J. H., Miao, L., Li, M. Y., Guo, X. F., Pan, N., Chen, Y. Y., et al. (2014). Cloning the Dmrt1 and DmrtA2 genes of ayu (Plecoglossus altivelis) and mapping their expression in adult, larval, and embryonic stages. Zool. Res. 35, 99–107.

Webster, K. A., Schach, U., Ordaz, A., Steinfeld, J. S., Draper, B. W., and Siegfried, K. R. (2017). Dmrt1 is necessary for male sexual development in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 422, 33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.12.008

Wei, L., Li, X., Li, M., Tang, Y., Wei, J., and Wang, D. (2019). Dmrt1 directly regulates the transcription of the testis-biased Sox9b gene in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Gene 687, 109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.11.016

Wen, A., You, F., Tan, X., Sun, P., Ni, J., Zhang, Y., et al. (2009). Expression pattern of dmrt4 from olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) in adult gonads and during embryogenesis. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 35, 421–433. doi: 10.1007/s10695-008-9267-5

Wexler, J. R., Plachetzki, D. C., and Kopp, A. (2014). Pan-metazoan phylogeny of the DMRT gene family: a framework for functional studies. Dev. Genes Evol. 224, 175–181. doi: 10.1007/s00427-014-0473-0

Winkler, C., Hornung, U., Kondo, M., Neuner, C., Duschl, J., Shima, A., et al. (2004). Developmentally regulated and non-sex-specific expression of autosomal dmrt genes in embryos of the Medaka fish (Oryzias latipes). Mech. Dev. 121, 997–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.03.018

Wu, G. C., and Chang, C. F. (2018). Primary males guide the femaleness through the regulation of testicular Dmrt1 and ovarian Cyp19a1a in protandrous black porgy. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 261, 198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.01.033

Xu, S., Xia, W., Zohar, Y., and Gui, J. F. (2013). Zebrafish dmrta2 regulates the expression of cdkn2c in spermatogenesis in the adult testis. Biol. Reprod. 88:14. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.105130

Yamaguchi, A., Lee, K. H., Fujimoto, H., Kadomura, K., Yasumoto, S., and Matsuyama, M. (2006). Expression of the DMRT gene and its roles in early gonadal development of the Japanese pufferfish Takifugu rubripes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomics Proteomics 1, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2005.08.003

Yan, N., Hu, J., Li, J., Dong, J., Sun, C., and Ye, X. (2019). Genomic organization and sexually dimorphic expression of the Dmrt1 gene in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 234, 68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2019.05.005

Yang, Z., and Nielsen, R. (2000). Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 32–43. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026236

Yoshimoto, S., Ikeda, N., Izutsu, Y., Shiba, T., Takamatsu, N., and Ito, M. (2010). Opposite roles of DMRT1 and its W-linked paralogue, DM-W, in sexual dimorphism of Xenopus laevis: implications of a ZZ/ZW-type sex-determining system. Development 137, 2519–2526. doi: 10.1242/dev.048751

Yoshizawa, A., Nakahara, Y., Izawa, T., Ishitani, T., Tsutsumi, M., Kuroiwa, A., et al. (2011). Zebrafish Dmrta2 regulates neurogenesis in the telencephalon. Genes Cells 16, 1097–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01555.x

Zarkower, D. (2001). Establishing sexual dimorphism: conservation amidst diversity? Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 175–185. doi: 10.1038/35056032

Zhang, T., Murphy, M. W., Gearhart, M. D., Bardwell, V. J., and Zarkower, D. (2014). The mammalian Doublesex homolog DMRT6 coordinates the transition between mitotic and meiotic developmental programs during spermatogenesis. Development 141, 3662–3671. doi: 10.1242/dev.113936

Zhang, X., Wang, H., Li, M., Cheng, Y., Jiang, D., Sun, L., et al. (2014). Isolation of doublesex- and mab-3-related transcription factor 6 and its involvement in spermatogenesis in tilapia. Biol. Reprod. 91:136. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.121418

Zhang, Z., Li, J., and Yu, J. (2006). Computing Ka and Ks with a consideration of unequal transitional substitutions. BMC Evol. Biol. 6:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-44

Zhou, X., Li, Q., Lu, H., Chen, H., Guo, Y., Cheng, H., et al. (2008). Fish specific duplication of Dmrt2: characterization of zebrafish Dmrt2b. Biochimie 90, 878–887. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.02.021

Zhu, L., Wilken, J., Phillips, N. B., Narendra, U., Chan, G., Stratton, S. M., et al. (2000). Sexual dimorphism in diverse metazoans is regulated by a novel class of intertwined zinc fingers. Genes Dev. 14, 1750–1764.

Keywords: fish, comparative genomics studies, dmrt genes, phylogenetic evolution, synteny analysis

Citation: Dong J, Li J, Hu J, Sun C, Tian Y, Li W, Yan N, Sun C, Sheng X, Yang S, Shi Q and Ye X (2020) Comparative Genomics Studies on the dmrt Gene Family in Fish. Front. Genet. 11:563947. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.563947

Received: 20 May 2020; Accepted: 16 October 2020;

Published: 12 November 2020.

Edited by:

Deshou Wang, Southwest University, ChinaReviewed by:

Jie Mei, Huazhong Agricultural University, ChinaZhigang Shen, Huazhong Agricultural University, China

Shikai Liu, Ocean University of China, China

Wenjing Tao, Southwest University, China

Silvia Portela Bens, University of Cádiz, Spain

Copyright © 2020 Dong, Li, Hu, Sun, Tian, Li, Yan, Sun, Sheng, Yang, Shi and Ye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiong Shi, c2hpcWlvbmdAZ2Vub21pY3MuY24=; Xing Ye, Z3p5ZXhpbmdAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Junjian Dong1†

Junjian Dong1† Jia Li

Jia Li Wuhui Li

Wuhui Li Song Yang

Song Yang Qiong Shi

Qiong Shi Xing Ye

Xing Ye