- State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-bioresources, Guangxi University, Nanning, China

Coat color is of great importance in animal breed characteristics; it is not only a significant productive trait but also an indispensable economic trait, especially in the rabbit industry. In the present study, the relationship between melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) genotypes and coat color phenotypes was observed in five rabbit breeds with popular coat colors that are present in China. These breeds comprised the Lianshan black rabbit (BR), Fujian yellow rabbit (YR), New Zealand white rabbit (WR), Gray Giant rabbit (GR), and Checkered Giant rabbit (CR), which were firstly determined, and the results showed that GR had an E allele; WR, CR, and BR had a 6-bp in-frame deletion (c.281_286del6, ED allele); and YR had a 30-bp deletion (c.304_333del30 E allele). To explore the feasibility of obtaining a novel rabbit coat color through the mutation of MC1R with the CRISPR/Cas9 system, two single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) were designed for the MC1R gene, and the editing efficiency was confirmed by injection of rabbits’ zygotes. Unlike the donor rabbits whose coat color was originally black, two novel pale-yellow-coated rabbits were generated in the founders. A total of six novel MC1R gene deletions were identified in the two founder rabbits, in which the longest deletion was more than 700 bp. The histological hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) staining results indicated that eumelanin amounts were absent in hair follicles of MC1R-knockout (KO) rabbits, when compared with that of donor BR. In addition, the messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of some key downstream genes in the MC1R pathway were all downregulated in MC1R-KO rabbits compared with BR and YR. These results further indicate that loss-of-function MC1R contributed to blocking the synthesis of eumelanin and created a novel pale-yellow coat color in the MC1R-KO rabbits, and gene editing technology may be a useful tool to generate novel phenotypes in rabbit breeding.

Introduction

Animal coat color is one of the most important breed characteristics, which is not only a significant productive trait but also an indispensable economic trait. As an important genetic marker for molecular breeding, great attention has been paid to the inheritance of rabbit coat color for a long time. In mammals, the Extension locus encodes the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), which is mainly expressed in hair follicle and skin melanocyte, closely related to skin pigmentation. The activation of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) initiates with MC1R complex signaling that leads to the manufacturing of black and dark-brown eumelanin pigments. The agouti signaling protein (ASIP) antagonized the receptors in dissimilar pathways, causing a switch from a eumelanin type pigment to phaeomelanin (Lu et al., 1994; Ollmann et al., 1998) and producing yellow or red pigments. MC1R is a highly polymorphic gene. Mutations in some single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) loci have been shown in the alteration of mammalian coat color, such as red guinea pig (Cone et al., 1996), chestnut horse (Marklund et al., 1996), and Holstein cow with red skin (Joerg et al., 1996). Additionally, MC1R gene mutations linked with different coat colors have been described in humans (Valverde et al., 1995), mice (Robbins et al., 1993), pigs (Kijas et al., 1998; Kijas et al., 2001), cattle (Klungland et al., 1995; Rouzaud et al., 2000), sheep (Vage et al., 1999), goats (Fontanesi et al., 2009), dogs (Everts et al., 2000; Newton et al., 2000), chickens (Kerje et al., 2003), and foxes (Vage et al., 1997; Vage et al., 2005), in which functional mutations increased to produce black/dark coat color and lack of functions usually generated original/yellow coat color.

In domesticated rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), conventional genetic studies have been involved in crossbreeding experiments of breeds of different coat colors where five alleles were recognized at the Extension locus, representing the following: ED shows black dominant; ES represents steel, which is weaker version of ED; E wild type (WT) expresses normal gray or an extension of black; eJ exists in Japanese brindling with a mosaic distribution of yellow and black; and e expresses a red/yellow appearance with white belly. The ED > ES > E > eJ > e order showed the dominance (Robinson, 1958; Fox, 1994). Fontanesi et al. (2006) identified in-frame deletion, connected with two possibilities, which were recessive red (c.304_333del30; allele e) and black dominant (c.280_285del6; alleles ED and/or ES) coat colors via sequencing nearly the complete coding sequence (CDS) of the rabbit MC1R gene. Awareness about the MC1R gene’s role and mechanism in coat color pattern determination predominantly relied on analysis of spontaneous mutations in farm animals. Genome-specific manipulation is important to further explore the MC1R gene function and to provide insight into the coat color mechanism with alteration and formation by precise modification in the MC1R gene.

Though it is widely known that gene polymorphism of MC1R is related to the coat color of animals, most studies only focused on the correlation between spontaneous mutations and the phenotype in various animal species. There is still lack of effective MC1R-knockout (KO) animal models to further study the function of MC1R. Here, by using the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system, we can destroy the protein structure of MC1R partially or completely, which may help us to better understand the mechanism of this gene. Moreover, this is the first research using this system to create a mammalian model and study the function of MC1R, and the use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system makes it possible to artificially obtain animals with popular or new coat colors.

In an attempt to find out whether the phenotype produced by the artificially modified MC1R gene is consistent with that of the spontaneous loss-of-function mutation, we knocked out the MC1R gene of a Lianshan black rabbit (BR) through a dual-sgRNA-directed CRISPR/Cas9 system and generated two MC1R mutated rabbits with pale yellow coats, which were distinctly different from the wild yellow rabbits. In our present work, it is the first time to find out a novel coat color in rabbits by the interruption of the MC1R gene via CRISPR/Cas9. MC1R-KO rabbit can be used as a model to further study MC1R gene information on different coat colors.

Materials and Methods

Rabbit Sampling

Ear clips of five individual rabbits [one BR, one YR, one New Zealand white rabbit (WR), one Gray Giant rabbit (GR), and one Checkered Giant rabbit (CR)] were sampled, and the genomic DNA was extracted from tissue lysate by using phenol–chloroform and recovered by alcohol precipitation.

Cloning and Analysis of Rabbit MC1R

For cloning and analysis of rabbit MC1R gene, genomic DNA from BR, YR, WR, GR, and CR with equal amounts (100 ng) was used as template for PCR amplification by a pair of specific primers (MC1R-F:5′-GGTGGCTGGTGTGGAAATGT-3′ and MC1R-R:5′-GCTGGCAAAGGGGCACTA-3′), which were designed based on the sequence of rabbit MC1R (GenBank: FN658676.1). A gel extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tec, USA) was used for PCR product purification and for cloning into the pMD18-T vector (Takara, Japan). Ten positive clones of each rabbit (a total of 50 clones) were sequenced and then analyzed by using BioEdit and MEGA7. Besides, the CDS of the MC1R gene of two other breeds, Thrianta rabbit (GenBank: FN658678.1) and Japanese brindling (GenBank: FN658679.1), was added in multiple-sequence alignment.

SgRNA Design and Plasmid Construction

In our previous published data, the protocols for sgRNA design and vector construction have been discussed in detail (Su et al., 2018). A dual-sgRNA targeting rabbit MC1R gene was designed according to the multiple-sequence alignment result of rabbits in different colors, and these two target sites avoided the spontaneous deletion regions in the rabbit MC1R gene.

In Vitro Transcription of Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA

The hSpCas9 (CMV-T7-NLS-hSpCas9-NLS) expression plasmid was linearized by restriction endonuclease EcoRI preparing for hSpCas9 messenger RNA (mRNA) transcription in vitro. sgRNAs with a T7 promoter sequence (TAATACGACTCACTATAGG) in upstream were made to produce sgRNA by in vitro transcription. The templates used to generate the sgRNA were obtained by using the primers listed in Table S1. The linearized plasmid of hSpCas9 and the amplified T7-sgRNA product were subjected to gel purification and applied as the template for in vitro transcription, respectively, by a mMESSAGEmMACHINE® T7 Kit (Ambion, USA) and a MEGAshortscript™ T7 Kit (Ambion, USA) in strict accordance with each manufacturer-recommended protocol. The quality and the concentration of RNA were estimated by agarose gel electrophoresis and determined by a BioSpec-nano UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Japan), respectively. The Cas9 mRNA and the sgRNA were both purified through a MEGAclearTM transcription clean-up kit (Ambion, USA), eluted into RNase-free water, and frozen at −80 °C.

Embryo Collection, Microinjection, and Transplantation

Superovulation was conducted in 6–8-month-old female BR with 1.2-mg follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) at intervals of 12 h for six times, after mating with male BR and then injected with 100-IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Eighteen hours after hCG injection, rabbit embryos were collected at the pronucleus stage by flushing the oviducts with a 5-ml oocyte manipulation medium. A mixture of in vitro transcribed Cas9 mRNA (100 ng/μl) and sgRNAs (20 ng/μl per sgRNA) was microinjected into the cytoplasm of fertilized eggs. The injected zygotes were transferred into an embryo culture medium and cultured at 38.5 °C in 5% CO2 for 5–10 min. About 14–16 injected embryos were then autologously transplanted into the oviduct of the donor rabbit.

Mutation Efficiency Detection in Blastocysts and Pups by PCR and Sequencing

For verification of indel mutations, injected embryos were collected at the blastocyst stage. Genomic DNA was extracted from a single blastocyst with a cell lysis buffer (Ambion) at 75 °C for 15 min and 95 °C for 10 min. The sgRNA target sites were amplified by using high-fidelity Golden Star T6 DNA polymerase (TsingKe, Beijing, China). PCR primers used for mutation detection were as follows: F, 5′-ACAGCCTCCCCCAGTCCT-3′; R, 5′-GCACCTCCTTGAGCGTCC-3′. The genomic DNA from MC1R KO and WT newborn rabbits were extracted from a small sample of ear tissue using Tris-phenol/chloroform. Primers MC1R-F/R were used for PCR genotyping. After gel purification, the PCR products were cloned into a pEASY-blunt simple vector (TransGen, Beijing, China) and then subjected to Sanger sequencing. Mutations were identified via alignment of the sequenced alleles to the WT.

Prediction of the Modified MC1R Protein Structure of MC1R KO Rabbits

To assess the influence of targeted deletion, five major targeted modifications were selected. Their 3D models were constituted using the online program Phyre2 (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index). The two spontaneous alleles of the MC1R protein were set as the control.

Off-Target Analysis

By testing whether off-target mutations presented in MC1R-KO rabbits, we predicted the potential off-target sites (POTS) of the sgRNAs using the online CRISPR Design Tool developed by the Zhang group at Massachusetts’s Institute of Technology (http://crispr.mit.edu/), and we selected the top eight POTS for each sgRNA. Then the PCR products of these POTS were subjected to T7E1 assay and Sanger sequence analysis. All primers for off-target assay were listed in Table S2.

T7E1 Cleavage Assay

The PCR products of POTS were gel purified. Next, a solution comprising 5-μl PCR products, 1.1–μl NEBuffer 2.1, and 4.4-μl ultrapure water was incubated at 95 °C for 10 min and then annealed at room temperature for at least 30 min. After that, hybridized PCR products were digested with 5-IU T7E1 (NEB) for 30 min at 37 °C and finally subjected to 2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Histology Analysis

Skin tissues of BR and MC1R-KO rabbits were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at 4 °C. The increasing concentrations of dehydrated ethanol (70% for 7 h, 85% for 5 h, 90% for 2 h, 95% for 2 h, and 100% for 2 h), dealcoholized with xylene and embedded in paraffin, were used for histological examination. The paraffin-embedded tissues which were sectioned into 5-μm-thick slices were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and analyzed with a fluorescence inverted microscope (Nikon, Japan). The integral optical density (IOD) analysis of histological sections was performed by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the skins of BR, YR, and MC1R-KO rabbits by TRIzol reagent (Ambion, Life Technologies, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, then treated with DNase I (Thermo Scientific, USA), and reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific). qPCR was performed using ChamQ™ Universal SYBR® qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China) with the ABI PRISM 7500 Real Time System (Applied Biosystems, USA), and the relative gene expression normalized to the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was determined by the 2−ΔΔCT formula. All the data of gene expression were performed three times. The candidate genes were microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), tyrosinase (TYR), tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP1), and dopachrome tautomerase (DCT). The specific primers for qPCR were listed in Table S3.

Statistics

All the quantitative data are expressed as mean ± SEM, with at least three individual determinations in all experiments. The data were analyzed by t-test using the SPSS 17.0 program. A probability of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The Relation of MC1R Genotypes and Coat Color Phenotypes

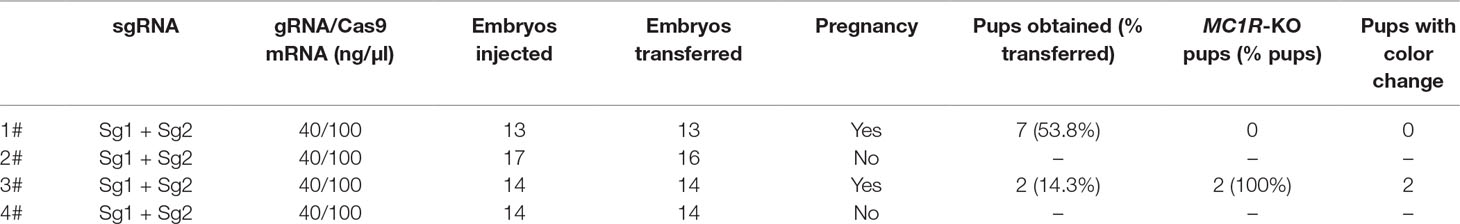

Cloned separately were 1,409 bp (regarded as a WT sequence) of the MC1R gene (the whole CDS of 954 bp was amplified and sequenced, 362 bp of the 5′-untranslated region and 93 bp of the 3′-untranslated region) in five rabbits with different coat colors, namely, BR, YR, WR, GR, and CR. The sequences obtained from WR, CR, and BR identified the presence of the 6-bp in-frame deletion (c.281_286del6, allele ED). The c.304_333del30 was identified in YR and Thrianta rabbit as the determinant of the e allele. Another 6-bp deletion flanked by a G > A transition in 5′ (c.[124G > A;125_130del6]) existed in Japanese brindling allele ej (Figure 1A). The MC1R gene of GR was WT allele E, which encoded 317 amino acids (AA). The ED allele carried by WR, CR, and BR had a two-amino-acid deletion in the second transmembrane (TM) domain. The e allele carried by YR and Thrianta rabbit had a 10-amino-acid deletion in the first extracellular loop. And the Japanese brindling allele (ej) had two AA in the first TM domain (Figure 1B). These three mutations were spontaneous.

Figure 1 Multiple-sequence alignment of rabbit MC1R gene and protein structures. (A) Multiple-exon-sequence alignment of MC1R gene of Gray Giant rabbit (GR), New Zealand White rabbit (WR), Checkered Giant rabbit (CR), Lianshan black rabbit (BR), Fujian yellow rabbit (YR), Thrianta rabbit (GenBank: FN658678.1), and Japanese brindling (GenBank: FN658679.1).The six nucleotides in blue and green boxes are those that are deleted in the rabbit MC1R gene c.125-130del6 and c.281-286del6 alleles, respectively. The 30 nucleotides in the red box are those deleted in the c.304-333del30 alleles. (B) Spontaneous mutations carried by rabbits of different breeds and coat colors. The MC1R gene of GR are wild-type alleles which encoded 317 amino acids. The two amino acids in blue circle is those deleted in the c.125-130del6 allele (eJ), carried by Japanese brindling rabbit. The two amino acids in green circle are those deleted in the c.125-130del6 alleles (ED), carried by WR, CR, and BR. And the 10 amino acids in red circle are those that are deleted in the c.304-333del30 alleles (e), carried by YR and Thrianta rabbit (the diagram of amino acid composition of rabbit mature MC1R protein with seven transmembrane domains was modified from Wolf Horrell et al. (2016).

Design and Determine the Efficiency of sgRNA Targeting Rabbit MC1R Gene

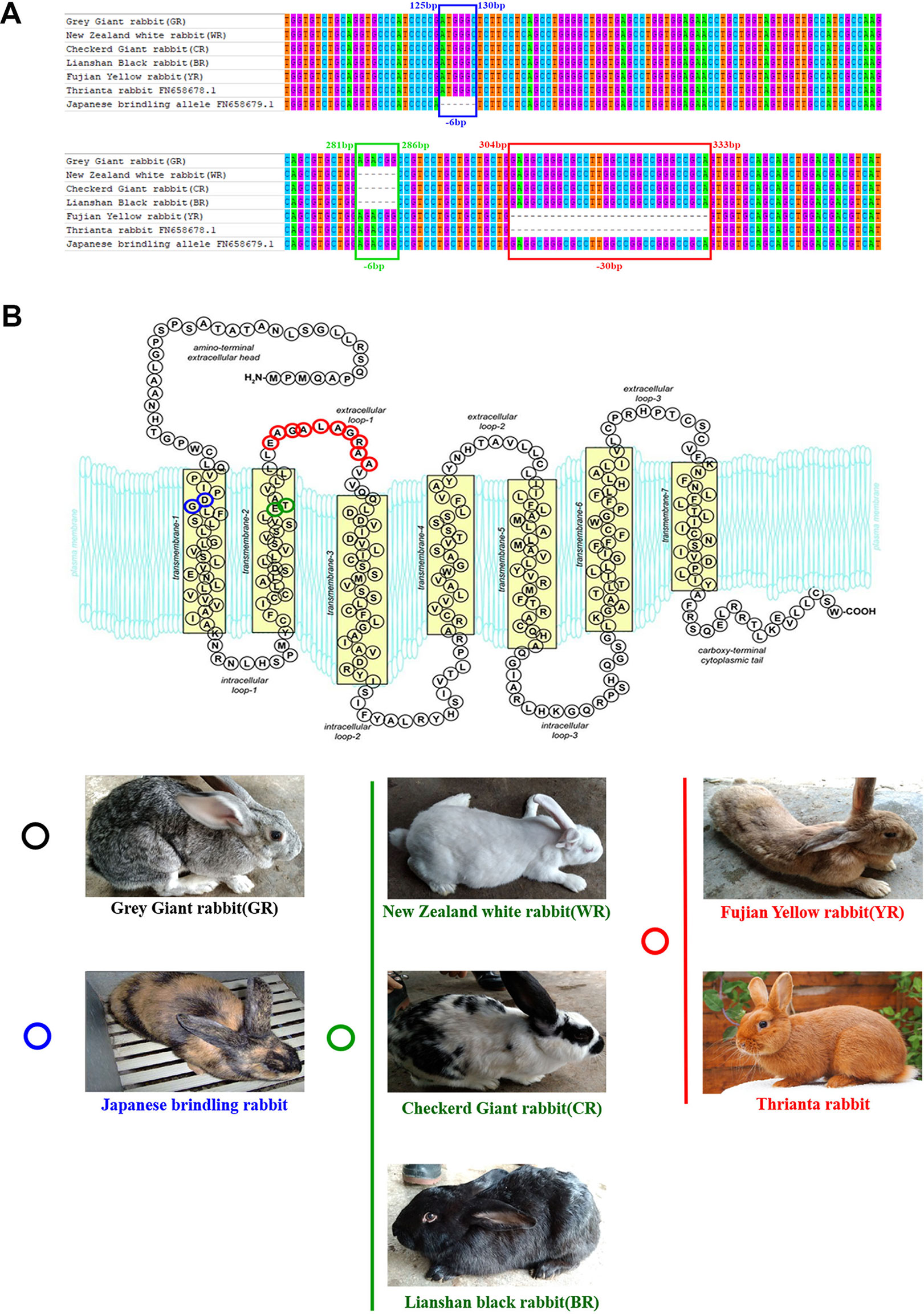

For the purpose of destroying MC1R in BR, a dual sgRNA targeting the CDS of MC1R was designed according to the multiple-sequence alignment result of rabbits in different colors, which avoided the natural deletion regions in rabbit MC1R gene (Figure 2A). Since the existence of spontaneous mutations, we did not perform the T7E1 assay in this determination, and the editing results were confirmed by Sanger sequence analysis. As shown in Figures 2B, C, mutations were identified in six of these seven blastocysts (85.7%). There were different long-fragment deletions in every mutated blastocyst. These results indicated that a dual–sgRNA-directed CRISPR/Cas9 system efficiently knocked out rabbit MC1R in our study.

Figure 2 Dual single-guide RNA (sgRNA)-directed deletion of MC1R in zygotes. (A) Schematic diagram of sgRNA targeting the rabbit MC1R gene loci. The yellow rectangle represents the transmembrane domain of MC1R. Two sgRNA sequences, sgRNA1 (Sg1#) and sgRNA2 (Sg2#), are highlighted in green. Protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences are presented in red with underline. Primers F and R are used for mutation detection in embryos. (B) Cytoplasmic injection of zygotes using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Seven blastocysts are collected. Mutation detection in blastocyst by PCR. M, marker; numbers 1–7 represent different blastocysts used in this study. The number in red represents the positive embryos. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) T-cloning and Sanger sequencing of the modified MC1R alleles in blastocysts. Wild-type sequence is shown at the top of the targeting sequence. Sequences of sgRNAs are marked in green, the PAM sequences are in red, insertions are highlighted in lowercase red letters, and deletions are designated by dashes. E: embryos; WT: ED allele; deletion: “−”; insertion: “+”.

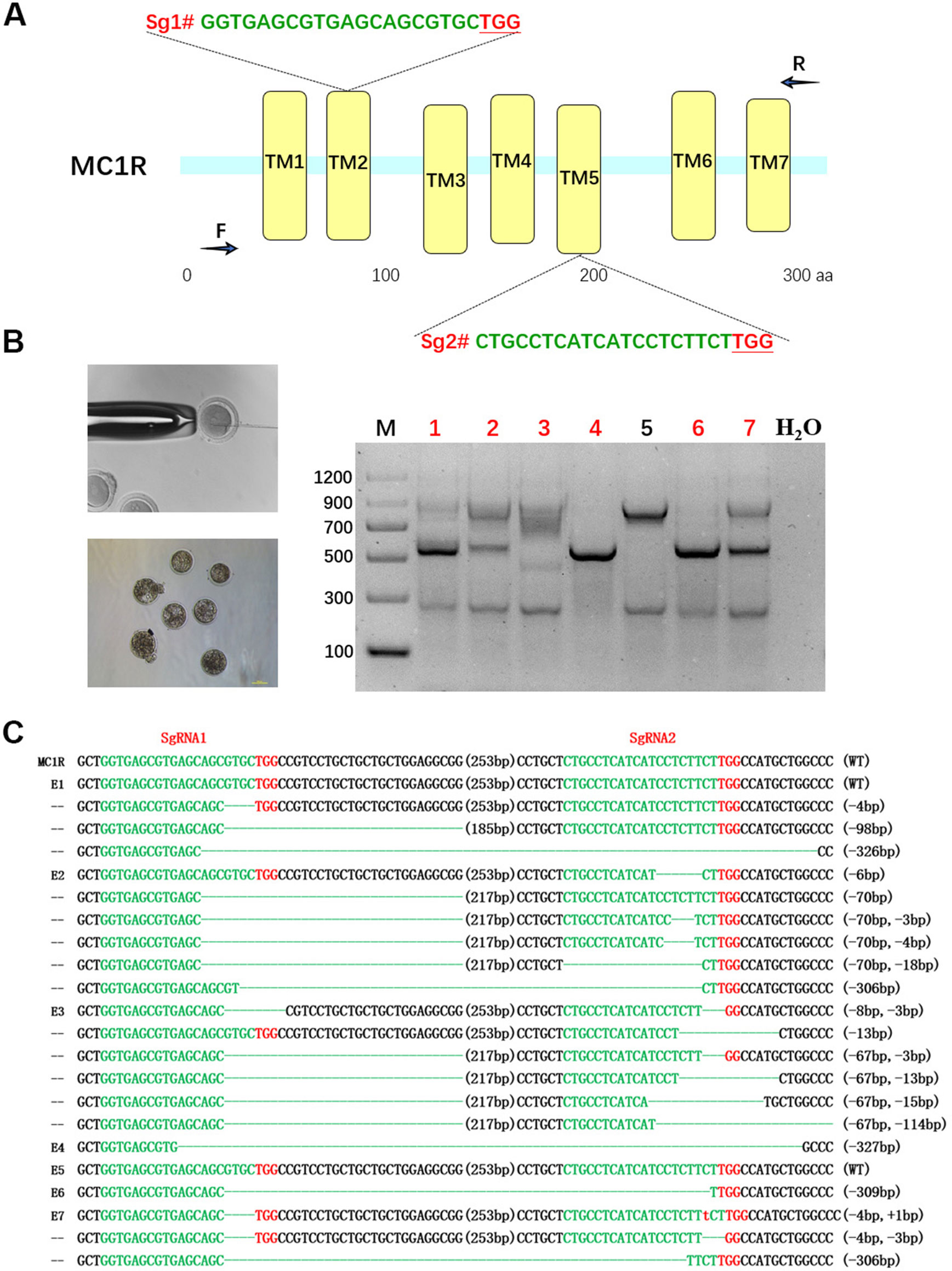

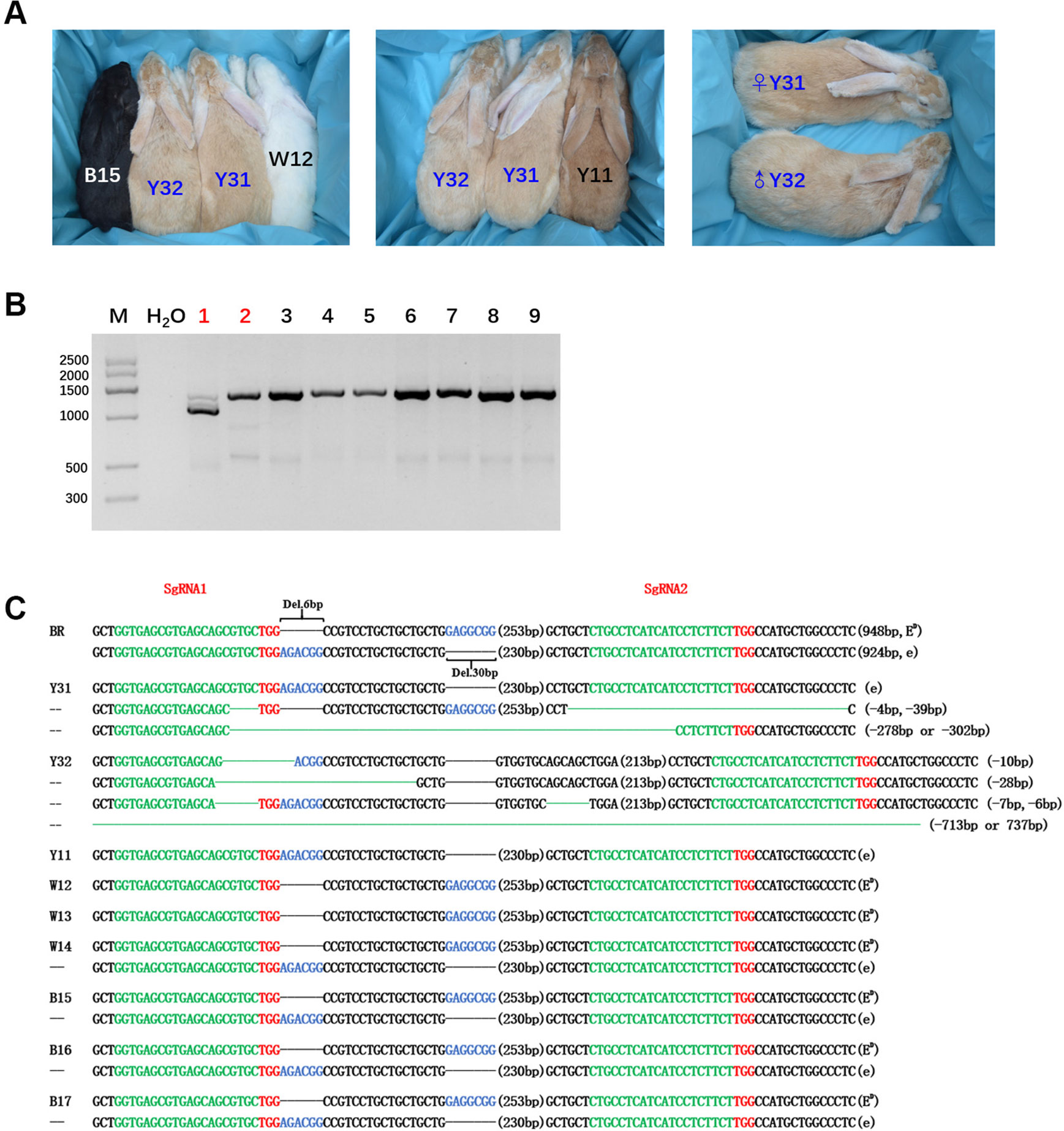

Generation of MC1R-KO Rabbits Using CRISPR/Cas9 System

After embryo transplantation and full-term gestation, two pregnant rabbits successfully gave birth to nine live pups (Table 1). MC1R modifications were not found in the seven pups from mother rabbit #1, but the other two pups from mother rabbit #3 all had a mutated MC1R gene. As expected, large-fragment deletions of MC1R gene were present in these two pups numbered Y31 and Y32, and Y31 had one WT sequence, namely, e allele, compared with BR, but Y32 did not (Figures 3B, C). As shown in Figure 3A, under the natural condition, the black male and female parents who had the heterozygous genotype (ED/e) would have pups of three colors, black (B15), yellow (Y11), and white (W12). Interestingly, the MC1R-KO rabbits Y31 and Y32 showed a novel beautiful coat color, a pale yellow distinctly different from wild yellow. And we found that two founder rabbits carried multiple mutant genotypes, ranging from 10-bp deletion to over 700-bp deletion. Because the deleted fragment is too long, which included both the 6-bp and 30-bp spontaneous deletions, it was impossible to know the original genotype and original coat color of Y32. But one thing was certain, that Y31 carried the ED allele at first, which meant that it was originally black and this black coat color was changed to pale yellow via gene editing. Taken together, we successfully generated MC1R-KO rabbits with a novel coat color using CRISPR/Cas9.

Figure 3 Generation of the MC1R-knockout (KO) rabbits with a new coat color using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. (A) Photographs of the MC1R-KO rabbits at 6 months old generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system; rabbit B15, black; rabbit W12, white; rabbit Y11, yellow; and rabbit Y31 and Y32, pale yellow. Y31 is a female rabbit, and Y32 is male. (B) The mutation was determined in founder rabbits by PCR. M, marker; 1, Y31; 2, Y32; 3, Y11; 4, W12; 5, W13; 6, W14; 7, B15; 8, B16; and 9, B17. The number in red represents the MC1R mutated pups. (C) T-cloning and Sanger sequencing in nine pups with modified MC1R alleles. The two alleles ED and e of parent Lianshan black rabbits (BR) are shown at the top of the targeting sequence. Spontaneous deletions are designated by black dashes, and the corresponding nondeleted bases are shown in blue. Sequences of single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) are marked in green, the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sites are highlighted in red, insertions are highlighted in lowercase red letters, and deletions are designated by green dashes. Deletion: “−”.

Characterization of Disruptive Modifications of MC1R-KO Rabbits

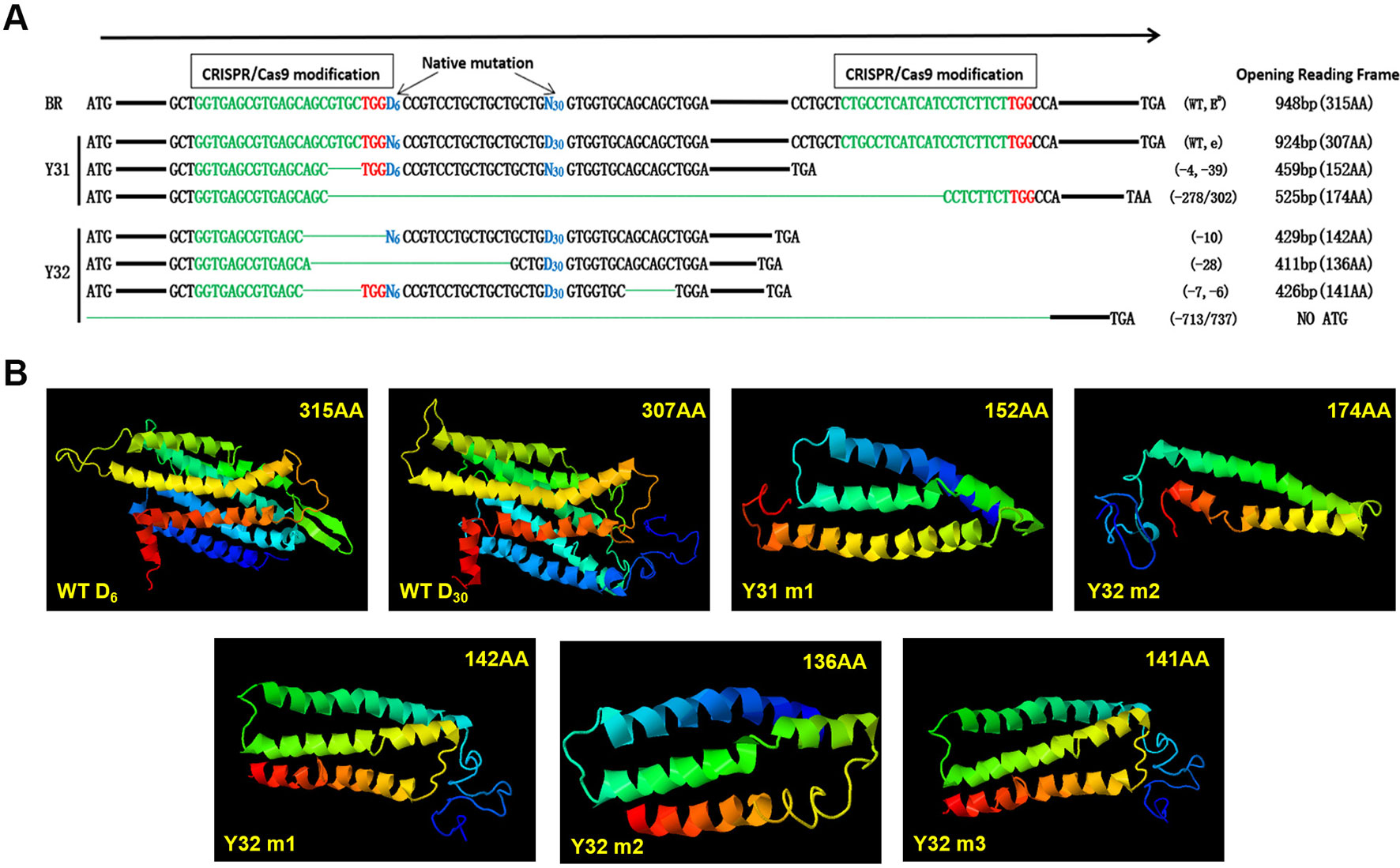

Through sequencing analysis, there were two types of MC1R modifications found in Y31 and four types in Y32. As there is involvement of a spontaneous 6-bp deletion denoted as D6 (c.281_286del6) and a 30-bp deletion denoted as D30 (c.304_333del30) in MC1R CDS, for a more intuitive display, we genotyped all modifications of two targeted rabbits by D6 or D30 deletions compared with BR (D denotes deletion and N nondeletion). Previous investigations found that D6N30 spontaneous mutations, namely, ED allele, were dominantly presented in black rabbit, and N6D30, namely, e allele, was recessive red/yellow (Fontanesi et al., 2006). So the genotype of the black one was ED/−, and the yellow one was ee. As shown in Figure 4A, the genotype of Y31 was ED/e, and that of Y32 was −/e, both of which are uncertain because the two spontaneous mutations were all deletion. Therefore, it was certain that the coat color of Y31 was changed from black to pale yellow via the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Further analysis revealed that, except the fourth modified type of Y32, which was deleted too long to have a start codon, the rest of the modifications all resulted in a frame shift and premature stop codon and, as consequence, led to a truncated MC1R protein that could completely or partially abolish the function of MC1R. The result of protein structure prediction showed that premature termination caused the absence of most of the TM structures which were essential for MC1R function (Figure 4B). It can be deduced that the targeting events led to the disruption of the MC1R function.

Figure 4 Diagram of the spontaneous deletions (D6N30 or N6D30) and prediction of protein structure of single-guide (sgRNA)/Cas9 targeted modifications of two MC1R-knockout (KO) rabbits. (A) “D6” is designated as a spontaneous deletion (versus N6 as nondeletion), with 6-bp deletion downstream of the ATG start codon. “D30” is designated as spontaneous deletion (versus N30 as nondeletion), with 30-bp deletion downstream of D6. The CRISPR/Cas9 targeted modifications are illustrated separately in the upstream and downstream of spontaneous deletion diagram, which shows the forms of modifications, and predicted protein products of a premature stop codon of amino acids. The sgRNA sequences are marked in green, PAM sites are red, and the deletions are designated by green dashes. (B) Construction of MC1R ED models according to five modifications and two WT types of BR. WT D6, structure of MC1R ED allele; WT D30, structure of MC1R e allele; Y31 m1, editing type of −4 and −39 bp; Y31 m2, editing type of −278 or 302 bp; Y32 m1, editing type of −10 bp; Y32 m2, editing type of −28 bp; Y32 m3, editing type of −7 and −6 bp.

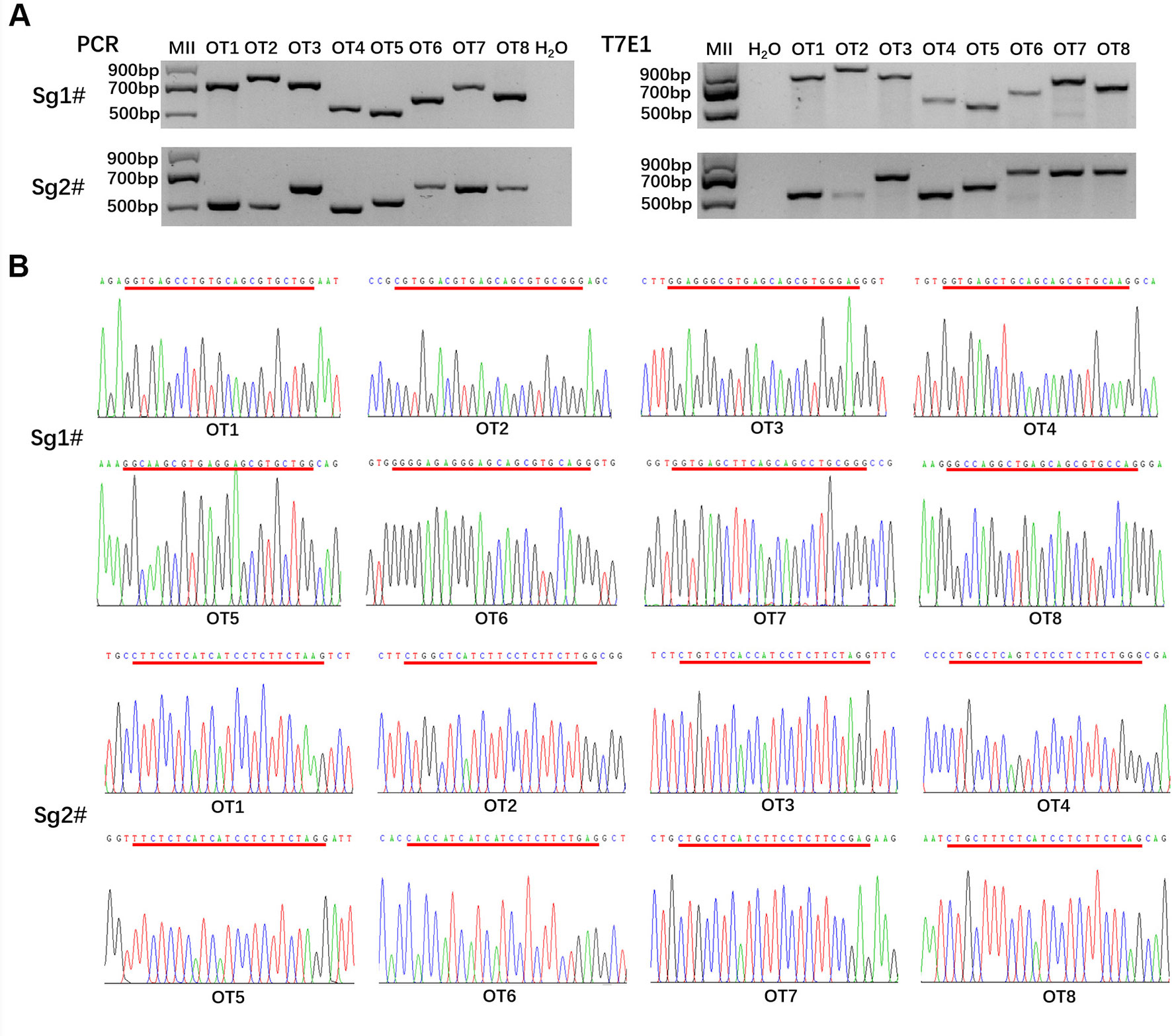

Off-Target Detection in the MC1R-KO Rabbits

To detect whether off-target mutations were present in MC1R-KO rabbits, we predicted POTS of the two sgRNAs using the online CRISPR Design Tool developed and selected the top eight POTS for each sgRNA. The results of T7E1 assay and Sanger sequence analysis showed that none of the off-target mutations was detected at these POTS in the MC1R-KO rabbits (Figures 5A, B). The information about POTS was listed in Table S2.

Figure 5 Off-target detection in the MC1R-knockout (KO) rabbits. (A) PCR and T7E1 assays of the top eight potential off-target sites (POTS) for Sg1# and Sg2#, respectively. No fragment is found in T7E1 assays. (B) Chromatogram sequence analysis of 16 POTS for Sg1# and Sg2# using PCR products in the founders. No double curve was shown in any sequencing diagrams. The POTS are underlined in red.

Phenotype Assessment of MC1R-KO Rabbits and Signal Pathway Analysis

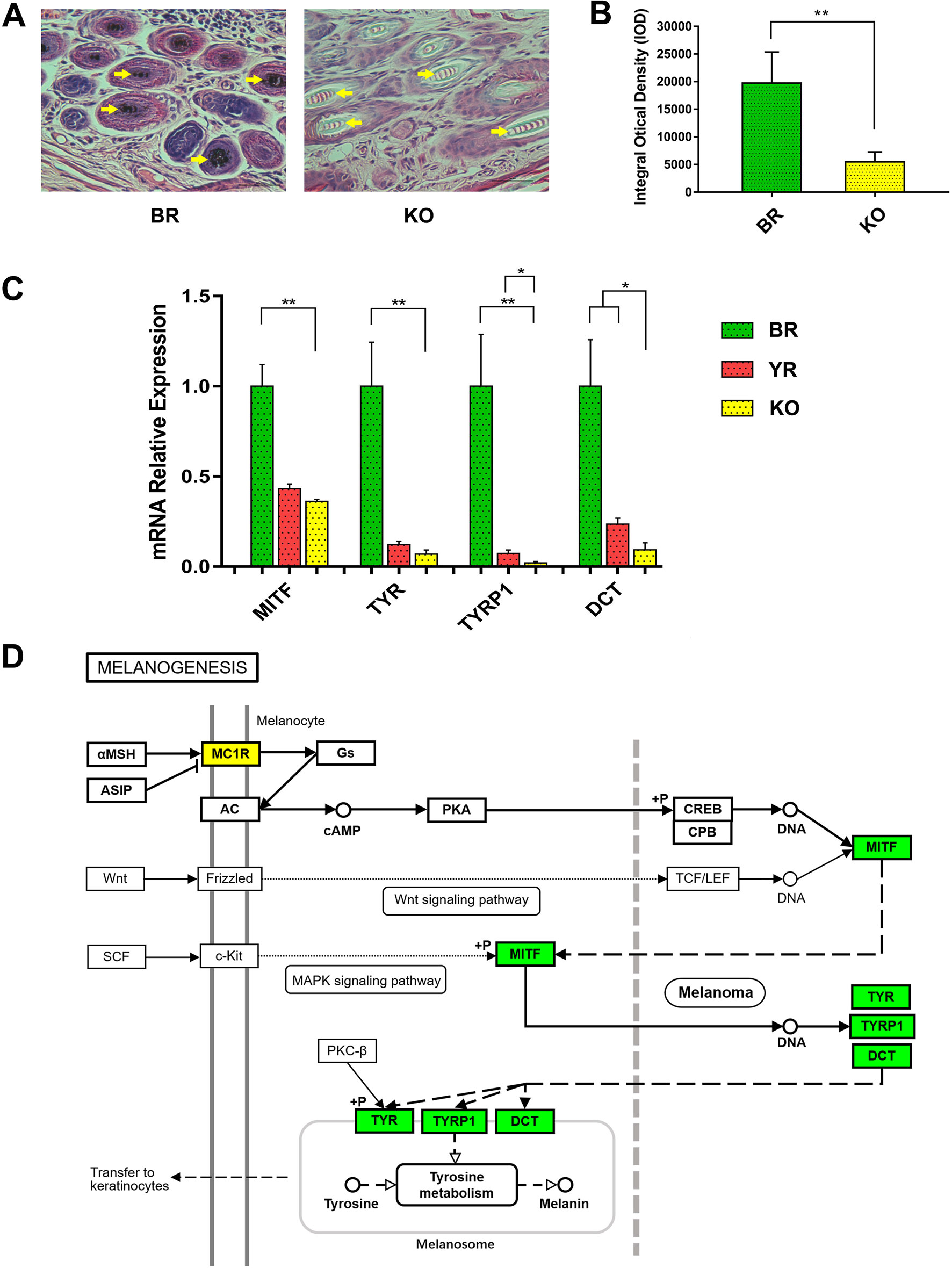

The histological H&E staining results indicated that eumelanin amounts were not present in hair follicles of MC1R-KO rabbits, when compared with BR (Figure 6A). And the histogram showed that the IOD of histological sections of KO rabbits was significantly lower than that of BR (Figure 6B). We further examined whether disruption of the MC1R led to reduced expression of the downstream gene of the MC1R signal pathway (Figure 6D) in the skin tissue. As shown in Figure 6C, the mRNA levels of MITF, TYR, TYRP1, and DCT gene were significantly reduced in MC1R-KO rabbits, when compared with the control group of BR. These results further indicate that loss of MC1R protein function contributed to blocking of the synthesis of eumelanin and created a new coat color in the MC1R-KO rabbits.

Figure 6 Phenotype identification and the expression of downstream genes in MC1R signal pathway of MC1R-KO rabbits. (A) H&E staining of the skin from the BR and KO rabbits. BR, Lianshan black rabbit; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; KO, MC1R-knockout rabbits. Scale bar, 100 μm for 400×. (B) Integral optical density (IOD) analysis of histological sections by Image-Pro Plus software. (C) Relative expression of MITF, TYR, TYRP1, and DCT genes were determined by Real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR). Bar graphs show mean values. Error bars represent standard error (SE). (D) The relation of MITF, TYR, TYRP1, and DCT in the melanogenesis pathway. The genes with a green frame are significantly downregulated in the KO skin compared with the BR skin. BR, Lianshan black rabbit; YR, Fujian yellow rabbit; KO, MC1R-KO rabbit. *0.01 < p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (the diagram of melanogenesis pathway was simplified from the KEGG pathway database, 04916, 10/23/15, Kanchisa Laboratories).

Discussion

MC1R is formed of seven α-helical (TM) domains with a DRY motif at the junction of the third TM domain, an intracellular C-terminus associated with palmitoylation site, and an extracellular N-terminus attached with an N-linked glycosylation site, like other G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Yang, 2011). The extracellular N-terminal tail performed the following functions: (1) ligand affinity (Chhajlani et al., 1996) and (2) sign anchor (Wallin and von Heijne, 1995; Garcia-Borron et al., 2005). There is a conserved cysteine residue present at the N-terminus junction and the first TM domain which is entirely essential for receptor function (Frandberg et al., 2001). The C-terminus in GPCR often plays a role in protein trafficking from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane (Schulein et al., 1998; Qanbar and Bouvier, 2003) and also in receptor interactions with the G protein at the plasma membrane (Strader et al., 1994). Previous studies have demonstrated that mutations which interrupt the pentapeptide or especially in the tripeptide variant such as premature termination at R306 (Newton et al., 2000) or removal of the terminal pentapeptide (Sanchez-Mas et al., 2005) result in minimized plasma membrane MC1R expression. as the extracellular loops of MC1R interconnect with ligands, mutations in this region affect binding affinity (Chhajlani et al., 1996). Likewise, mc1r intracellular loops play a vital role in binding of the Gs protein. Thus, any loss of function from MC1R gene mutations could affect the MC1R signaling pathway and interfere with melanogenesis.

The WT E allele of rabbit MC1R gene has 317 AA, and the phenotype of coat color is normal grey, like GR. The ED and ES alleles remove two AA in the second TM domain (c.280_285del6) and result in the dominant black and steel coat colors, respectively (Fontanesi et al., 2006). Therefore, the black breeds like BR certainly carry this dominant allele (ED/ED or ED/−).The recessive allele removes 10 AA of the first extracellular loop (c.304_333del30) and was in a homozygous condition in all red/yellow rabbit breeds such as Thuringian breeds and YR (Fontanesi et al., 2006). In our study, the result of sequencing the complete MC1R gene CDS of GR, WR, CR, BR, and YR was consistent with previous reports. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the MC1R-KO gene of BR will produce a yellow phenotype.

In an attempt to find out whether the phenotype produced by the artificially modified MC1R gene is consistent with that of the spontaneous loss-of-function mutation, the MC1R gene was targeted by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. By coinjection of sgRNA and Cas9 mRNAs into rabbit zygotes, we got two MC1R-KO rabbits of novel coat color. Sanger sequencing indicated that the deletion in the MC1R gene of the founder rabbits ranged from 10 to more than 700 bp. The MC1R-KO model in mammals was the first time to be reported. Compared with the wild yellow rabbit, the coat color of MC1R-KO rabbits was obviously lighter (Figure 3A). It is worth noting that in offspring, white rabbits were produced besides black and yellow ones, and all white rabbits carried the dominant black allele ED (Figure 3C). In rabbits, the white coat color is controlled by the C locus which encodes the Tyrosinase (Tyr) gene rather than the E locus that encodes MC1R (Aigner et al., 2000). Previous studies have demonstrated that TYR is the rate-limiting enzyme to catalyze melanogenesis and plays key roles in melanin biosynthesis and albinism (Simeonov et al., 2013). Mutated Tyr gene resulted in a lack of pigmentation because of melanin production deficiency. We speculated that the parent rabbits carried the heterozygous Tyr mutation and the albinism phenotype was not affected by whether MC1R was knocked out or not.

In order to analyze the original genotypes of MC1R-KO rabbits, we also identified the MC1R genotypes of parent rabbits. The genotypes of parents were all ED/e, and the progenies from mother rabbit #1 showed three expected genotypes. One of two MC1R-KO rabbits could not be determined due to the very-large-fragment deletions in the MC1R gene, but the other originally carrying the dominant black allele ED was confirmed. Due to the nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) feature caused by CRISPR/Cas9, alleles were randomly edited and may have different modifications for each allele. There were six types of modifications in MC1R-KO rabbits, which resulted in frame shift and premature termination, and even part of intron sequences had even been deleted. Based on the 3D model prediction of protein, premature terminations all consequently led to protein truncation, and all the five truncated proteins lacked at least half of the TM domains. As for two spontaneous mutant proteins, D30 lacked two β-turns compared with the protein of D6. β-Turns play a vital part in proteins, which makes it possible to change the direction for the polypeptide, concerning protein folding and molecular recognition (Rose et al., 1985). On account of the protein encoded by the e allele missing two β-turns in the first extracellular loop, the recognition of MC1R by ligands was affected; thus, the activation of the pathway to produce eumelanin was interfered with. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the destruction of TM domains and the complete C-terminal domain produced by the KO of the MC1R gene destroyed the receptor structure to a greater extent, which resulted in more functional defects of MC1R.

MC1R is involved in melanin synthesis by binding to two ligands: α-MSH and ASIP (Choudhary et al., 2016). The combination of α-MSH to MC1R will activate the adenylate cyclase system, increase the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) level, and then promote the synthesis of eumelanin and inhibit the yield of pheomelanin, whereas binding of ASIP to MC1R reduces constitutive signaling to the cAMP pathway, which results in a decrease in the production of eumelanin and an increase in the yield of pheomelanin, thus regulating the change of coat color (Le Pape et al., 2008;Le Pape et al., 2009). As the downstream genes of MC1R/cAMP pathway, MITF (Steingrimsson et al., 2004; Levy et al., 2006), TYR (Wang and Hebert, 2006; Ando et al., 2007), TYRP1 (del Marmol and Beermann, 1996; Lai et al., 2018), and DCT (Aroca et al., 1992; Guyonneau et al., 2004) genes were very crucial in the melanogenesis pathway (Figure 6D). We demonstrated that the MC1R/cAMP pathway was disturbed and dysfunctional MC1R leads to different degrees of reduction in the expression of these genes in MC1R-KO rabbits compared with the wild yellow rabbit (Figure 6C). This result reasonably explained the lighter yellow phenotype of MC1R-KO rabbits at the molecular level.

Conclusion

In summary, a novel pale-yellow coat color in MC1R-KO rabbits was generated by interruption of the MC1R gene in BR via CRISPR/Cas9 system. Our work demonstrated that rabbit MC1R gene plays a vital role in coat color determination and disruption of MC1R gene will change the coat color. The gene editing rabbits with the novel coat color can be used as a model for further study on the mechanisms of MC1R gene function. In addition, our study established the foundation of using the CRISPR/Cas9 system to artificially obtain animals with popular or new coat colors.

Data Availability

All datasets for this study are included in the manuscript and the Supplementary Files.

Ethics Statement

Rabbits were used in present study were fed regularly at Laboratory Animal Center of Guangxi University. All experimental studies were approved and reviewed by the Experimental Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangxi University (Permit code: GXU2019-029). In present study, rabbit experiment was performed by the Principle Guidance for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals.

Author Contributions

NX, DS, and QL conceived and designed the experiments. NX, HL, SZ, XS, and YZ performed the experiments. NX analyzed the data, and LS wrote the manuscript. KC revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present study was granted and supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31772597 and 31860638), and we are also grateful to the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (Grant Nos. AA17204051 and AB16380042).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for the technical support from the State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-bioresources. We also thank the Laboratory Animal Center of Guangxi University for providing the experimental rabbits.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2019.00875/full#supplementary-material

References

Aigner, B., Besenfelder, U., Muller, M., Brem, G. (2000). Tyrosinase gene variants in different rabbit strains. Mamm Genome 11 (8), 700–702. doi: 10.1007/s003350010120

Ando, H., Kondoh, H., Ichihashi, M., Hearing, V. J. (2007). Approaches to identify inhibitors of melanin biosynthesis via the quality control of tyrosinase. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 127 (4), 751–761. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700683

Aroca, P., Solano, F., Salinas, C., Garcia-Borron, J. C., Lozano, J. A. (1992). Regulation of the final phase of mammalian melanogenesis. The role of dopachrome tautomerase and the ratio between 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid and 5,6-dihydroxyindole. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 208 (1), 155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17169.x

Chhajlani, V., Xu, X., Blauw, J., Sudarshi., S. (1996). Identification of ligand binding residues in extracellular loops of the melanocortin 1 receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 219 (2), 521–525. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0266

Choudhary, R., Kumar, S., Singh, S. V., Sharma, A. K., Goud, T. S., Srivastava, A. K., et al. (2016). Validation of putative reference genes for gene expression studies in heat stressed and alpha-MSH treated melanocyte cells of Bos indicus using real-time quantitative PCR. Mol. Cell Probes. 30 (3), 161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2016.03.002

Cone, R. D., Lu, D. S., Koppula, S., Vage, D. I., Klungland, H., Boston, B., et al. (1996). “The melanocortin receptors: agonists, antagonists, and the hormonal control of pigmentation,” in Recent progress in hormone research, vol. 51. Ed. Conn, P. M. (Chevy Chase: Endocrine Soc), 287–318. Proceedings of the 1995 Conference.

del Marmol, V., Beermann, F. (1996). Tyrosinase and related proteins in mammalian pigmentation. Febs Lett. 381 (3), 165–168. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00109-3

Everts, R. E., Rothuizen, J., van Oost, B. A. (2000). Identification of a premature stop codon in the melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor gene (MC1R) in Labrador and golden retrievers with yellow coat colour. Anim. Genet. 31 (3), 194–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.2000.00639.x

Fontanesi, L., Beretti, F., Riggio, V., Dall’Olio, S., Gonzalez, E. G., Finocchiaro, R., et al. (2009). Missense and nonsense mutations in melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) gene of different goat breeds: association with red and black coat colour phenotypes but with unexpected evidences. BMC Genet. 10, 47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-10-47

Fontanesi, L., Tazzoli, M., Beretti, F., Russo, V. (2006). Mutations in the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) gene are associated with coat colours in the domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Anim. Genet. 37 (5), 489–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01494.x

Fox, R. R. (1994). “Taxonomy and genetics,” in The biology of the laboratory rabbit, 2nd ed. Eds. Manning, P. J., Ringler, D. H., Newcomer, C. E. (San Diego: Academic Press), 1–26.

Frandberg, P. A., Doufexis, M., Kapas, S., Chhajlani, V. (2001). Cysteine residues are involved in structure and function of melanocortin 1 receptor: substitution of a cysteine residue in transmembrane segment two converts an agonist to antagonist. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 281 (4), 851–857. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4429

Garcia-Borron, J. C., Sanchez-Laorden, B. L., Jimenez-Cervantes, C. (2005). Melanocortin-1 receptor structure and functional regulation. Pigment Cell Res. 18 (6), 393–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00278.x

Guyonneau, L., Murisier, F., Rossier, A., Moulin, A., Beermann, F. (2004). Melanocytes and pigmentation are affected in dopachrome tautomerase knockout mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 24 (8), 3396–3403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3396-3403.2004

Joerg, H., Fries, H. R., Meijerink, E., Stranzinger, G. F. (1996). Red coat color in Holstein cattle is associated with a deletion in the MSHR gene. Mamm. Genome 7 (4), 317–318. doi: 10.1007/s003359900090

Kerje, S., Lind, J., Schutz, K., Jensen, P., Andersson, L. (2003). Melanocortin 1-receptor (MC1R) mutations are associated with plumage colour in chicken. Anim. Genet. 34 (4), 241–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.2003.00991.x

Kijas, J. M., Moller, M., Plastow, G., Andersson, L. (2001). A frameshift mutation in MC1R and a high frequency of somatic reversions cause black spotting in pigs. Genetics 158 (2), 779–785. doi: 10.1017/S0016672301005043

Kijas, J. M., Wales, R., Tornsten, A., Chardon, P., Moller, M., Andersson, L. (1998). Melanocortin receptor 1 (MC1R) mutations and coat color in pigs. Genetics 150 (3), 1177–1185.

Klungland, H., Vage, D. I., Gomez-Raya, L., Adalsteinsson, S., Lien, S. (1995). The role of melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) receptor in bovine coat color determination. Mamm. Genome 6 (9), 636–639. doi: 10.1007/BF00352371

Lai, X. L., Wichers, H. J., Soler-Lopez, M., Dijkstra, B. W. (2018). Structure and function of human tyrosinase and tyrosinase-related proteins. Chemistry 24 (1), 47–55. doi: 10.1002/chem.201704410

Le Pape, E., Passeron, T., Giubellino, A., Valencia, J. C., Wolber, R., Hearing, V. J. (2009). Microarray analysis sheds light on the dedifferentiating role of agouti signal protein in murine melanocytes via the Mc1r. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106 (6), 1802–1807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806753106

Le Pape, E., Wakamatsu, K., Ito, S., Wolber, R., Hearing, V. J. (2008). Regulation of eumelanin/pheomelanin synthesis and visible pigmentation in melanocytes by ligands of the melanocortin 1 receptor. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 21 (4), 477–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00479.x

Levy, C., Khaled, M., Fisher, D. E. (2006). MITF: master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol. Med. 12 (9), 406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.008

Lu, D., Willard, D., Patel, I. R., Kadwell, S., Overton, L., Kost, T., et al. (1994). Agouti protein is an antagonist of the melanocyte-stimulating-hormone receptor. Nature 371 (6500), 799–802. doi: 10.1038/371799a0

Marklund, L., Moller, M. J., Sandberg, K., Andersson, L. (1996). A missense mutation in the gene for melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor (MC1R) is associated with the chestnut coat color in horses. Mamm. Genome 7 (12), 895–899. doi: 10.1007/s003359900264

Newton, J. M., Wilkie, A. L., He, L., Jordan, S. A., Metallinos, D. L., Holmes, N. G., et al. (2000). Melanocortin 1 receptor variation in the domestic dog. Mamm. Genome 11 (1), 24–30. doi: 10.1007/s003350010005

Ollmann, M. M., Lamoreux, M. L., Wilson, B. D., Barsh, G. S. (1998). Interaction of agouti protein with the melanocortin 1 receptor in vitro and in vivo. Genes Dev. 12 (3), 316–330. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.3.316

Qanbar, R., Bouvier, M. (2003). Role of palmitoylation/depalmitoylation reactions in G-protein-coupled receptor function. Pharmacol. Ther. 97 (1), 1–33. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(02)00300-5

Robbins, L. S., Nadeau, J. H., Johnson, K. R., Kelly, M. A., Roselli-Rehfuss, L., Baack, E., et al. (1993). Pigmentation phenotypes of variant extension locus alleles result from point mutations that alter MSH receptor function. Cell 72 (6), 827–834. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90572-8

Robinson, R. (1958). “Genetic studies of the rabbit,” in Genetic studies of the rabbit. The Hague, Holland: Martinus Nijhoff.

Rose, G. D., Glerasch, L. M., Smith, J. A. (1985). Turns in peptides and proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 37, 1–109. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(08)60063-7

Rouzaud, F., Martin, J., Gallet, P. F., Delourme, D., Goulemot-Leger, V., Amigues, Y., et al. (2000). A first genotyping assay of French cattle breeds based on a new allele of the extension gene encoding the melanocortin-1 receptor (Mc1r). Genet. Sel. Evol. 32 (5), 511–520. doi: 10.1051/gse:2000102

Sanchez-Mas, J., Sanchez-Laorden, B. L., Guillo, L. A., Jimenez-Cervantes, C., Garcia-Borron, J. C. (2005). The melanocortin-1 receptor carboxyl terminal pentapeptide is essential for MC1R function and expression on the cell surface. Peptides 26 (10), 1848–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.11.030

Schulein, R., Hermosilla, R., Oksche, A., Dehe, M., Wiesner, B., Krause, G., et al. (1998). A dileucine sequence and an upstream glutamate residue in the intracellular carboxyl terminus of the vasopressin V2 receptor are essential for cell surface transport in COS.M6 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 54 (3), 525–535. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.3.525

Simeonov, D. R., Wang, X., Wang, C., Sergeev, Y., Dolinska, M., Bower, M., et al. (2013). DNA variations in oculocutaneous albinism: an updated mutation list and current outstanding issues in molecular diagnostics. Hum. Mutat. 34 (6), 827–835. doi: 10.1002/humu.22315

Steingrimsson, E., Copeland, N. G., Jenkins, N. A. (2004). Melanocytes and the microphthalmia transcription factor network. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38, 365–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092717

Strader, C. D., Fong, T. M., Tota, M. R., Underwood, D., Dixon, R. A. (1994). Structure and function of G protein-coupled receptors. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63, 101–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.000533

Su, X., Cui, K., Du, S., Li, H., Lu, F., Shi, D., et al. (2018). Efficient genome editing in cultured cells and embryos of Debao pig and swamp buffalo using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 54 (5), 375–383. doi: 10.1007/s11626-018-0236-8

Vage, D. I., Fuglei, E., Snipstad, K., Beheim, J., Landsem, V. M., Klungland, H. (2005). Two cysteine substitutions in the MC1R generate the blue variant of the Arctic fox (Alopex lagopus) and prevent expression of the white winter coat. Peptides 26 (10), 1814–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.11.040

Vage, D. I., Klungland, H., Lu, D., Cone, R. D. (1999). Molecular and pharmacological characterization of dominant black coat color in sheep. Mamm. Genome 10 (1), 39–43. doi: 10.1007/s003359900939

Vage, D. I., Lu, D., Klungland, H., Lien, S., Adalsteinsson, S., Cone, R. D. (1997). A non-epistatic interaction of agouti and extension in the fox, Vulpes vulpes. Nat. Genet. 15 (3), 311–315. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-311

Valverde, P., Healy, E., Jackson, I., Rees, J. L., Thody, A. J. (1995). Variants of the melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor gene are associated with red hair and fair skin in humans. Nat. Genet. 11 (3), 328–330. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-328

Wallin, E., von Heijne, G. (1995). Properties of N-terminal tails in G-protein coupled receptors: a statistical study. Protein Eng. 8 (7), 693–698. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.7.693

Wang, N., Hebert, D. N. (2006). Tyrosinase maturation through the mammalian secretory pathway: bringing color to life. Pigment Cell Res. 19 (1), 3–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00288.x

Wolf Horrell, E. M., Boulanger, M. C., D'Orazio, J. A. (2016). Melanocortin 1 receptor: structure, function, and regulation. Front Genet. 7, 95. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00095

Keywords: rabbit, MC1R, novel coat color, Cas9, knockout

Citation: Xiao N, Li H, Shafique L, Zhao S, Su X, Zhang Y, Cui K, Liu Q and Shi D (2019) A Novel Pale-Yellow Coat Color of Rabbits Generated viaMC1R Mutation With CRISPR/Cas9 System. Front. Genet. 10:875. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00875

Received: 28 March 2019; Accepted: 20 August 2019;

Published: 18 September 2019.

Edited by:

Göran Andersson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SwedenReviewed by:

Nelson Colihueque, University of Los Lagos, ChileShaojun Liu, Hunan Normal University, China

Copyright © 2019 Xiao, Li, Shafique, Zhao, Su, Zhang, Cui, Liu and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qingyou Liu, cXlsaXUtZ2VuZUBneHUuZWR1LmNu; Deshun Shi, YXJkc3NoaUBneHUuZWR1LmNu

Ning Xiao

Ning Xiao Yu Zhang

Yu Zhang Qingyou Liu

Qingyou Liu