- Dipartimento di Biotecnologie e Bioscienze, Università di Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are particularly hazardous lesions as their inappropriate repair can result in chromosome rearrangements, an important driving force of tumorigenesis. DSBs can be repaired by end joining mechanisms or by homologous recombination (HR). HR requires the action of several nucleases that preferentially remove the 5′-terminated strands at both DSB ends in a process called DNA end resection. The same nucleases are also involved in the processing of replication fork structures. Much of our understanding of these pathways has come from studies in the model organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Here, we review the current knowledge of the mechanism of resection at DNA DSBs and replication forks.

Introduction

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are highly cytotoxic forms of DNA damage because their incorrect repair or failure to repair causes chromosome loss and rearrangements that can lead to cell death or transformation (Liu et al., 2012). They can form accidentally during normal cell metabolism or after exposure of cells to ionizing radiations or chemotherapeutic drugs. In addition, DSBs are intermediates in programmed recombination events in eukaryotic cells. Indeed, defects in DSB signaling or repair are associated with developmental, immunological and neurological disorders, and tumorigenesis (O’Driscoll, 2012).

Conserved pathways extensively studied in recent years are devoted to repair DSBs in eukaryotes. The two predominant repair mechanisms are non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) and the choice between them is regulated during the cell cycle. NHEJ allows a direct ligation of the DNA ends with very little or no complementary base pairing and it operates predominantly in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Chiruvella et al., 2013). The initial step involves the binding to DNA ends of the Ku heterodimer, which protects the DNA ends from degradation, followed by ligation of the broken DNA ends by the DNA ligase IV (Dnl4/Lig4 in yeast) complex. By contrast, HR is the predominant repair pathway in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle and it requires a homologous duplex DNA to direct the repair (Mehta and Haber, 2014). For HR to occur, the 5′-terminated DNA strands on either side of the DSB must first be degraded by a concerted action of nucleases to generate 3′-ended single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) tails in a process referred to as resection (Cejka, 2015; Symington, 2016). These tails are first bound by the ssDNA binding complex Replication Protein A (RPA). RPA is then replaced by the recombination protein Rad51 to form a right-handed helical filament that is used to search and invade the homologous duplex DNA (Mehta and Haber, 2014).

Double-strand break occurrence also triggers the activation of a sophisticated highly conserved pathway, called DNA damage checkpoint, which couples DSB repair with cell cycle progression (Gobbini et al., 2013; Villa et al., 2016). Apical checkpoint proteins include phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase related protein kinases, such as mammalian ATM (Ataxia-Telangiectasia-Mutated) and ATR (ATM- and Rad3-related), orthologs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Tel1 and Mec1, respectively (Ciccia and Elledge, 2010). Once Mec1/ATR and/or Tel1/ATM are activated, their checkpoint signals are propagated through the S. cerevisiae protein kinases Rad53 and Chk1 (CHK2 and CHK1 in mammals, respectively), whose activation requires the conserved protein Rad9 (53BP1 in mammals) (Sweeney et al., 2005). While Tel1/ATM recognizes unprocessed or minimally processed DSBs, Mec1/ATR is recruited to and activated by RPA-coated ssDNA, which arises upon resection of the DSB ends (Zou and Elledge, 2003).

Most of our knowledge of the nucleolytic activities responsible for DSB resection has come from studies in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, where DNA end resection can be monitored physically at sites of endonuclease-induced DSBs. Interestingly, the same nucleases involved in DSB resection are also responsible for the processing of stalled replication forks both in yeast and in mammals. Here we will focus on the work done in S. cerevisiae to understand the resection mechanism at DNA DSBs and replication forks and its regulation by Tel1/ATM and Mec1/ATR checkpoint kinases.

Nuclease Action at Dna Double-Strand Breaks

Genetic studies in S. cerevisiae identified at least three distinct nucleases involved in end-resection: the MRX (Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 in yeast; MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 in mammals) complex, Dna2 and Exo1 (DNA2 and EXO1 in mammals, respectively). In particular, the Mre11 subunit of MRX has five conserved phosphoesterase motifs in the amino-terminal half of the protein that are required for 3′–5′ double-strand DNA (dsDNA) exonuclease and ssDNA endonuclease activities of the protein in vitro (Bressan et al., 1998; Paull and Gellert, 1998; Trujillo et al., 1998; Usui et al., 1998). Rad50 is characterized by Walker A and B ATP binding cassettes located at the amino- and carboxy-terminal regions of the protein, with the intervening sequence forming a long antiparallel coiled-coil. The apex of the coiled-coil domain can interact with other MRX complexes by Zn+-mediated dimerization to tether the bound DNA ends together (de Jager et al., 2001; Hopfner et al., 2002; Wiltzius et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2008). The ATP-bound state of Rad50 inhibits the Mre11 nuclease activity by masking the active site of Mre11 from contacting DNA (Lim et al., 2011). ATP hydrolysis induces conformational changes of both Rad50 and Mre11 that allow the Mre11 nuclease domain to access the DSB ends and to be engaged in DSB resection (Lammens et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2011; Möckel et al., 2012; Deshpande et al., 2014).

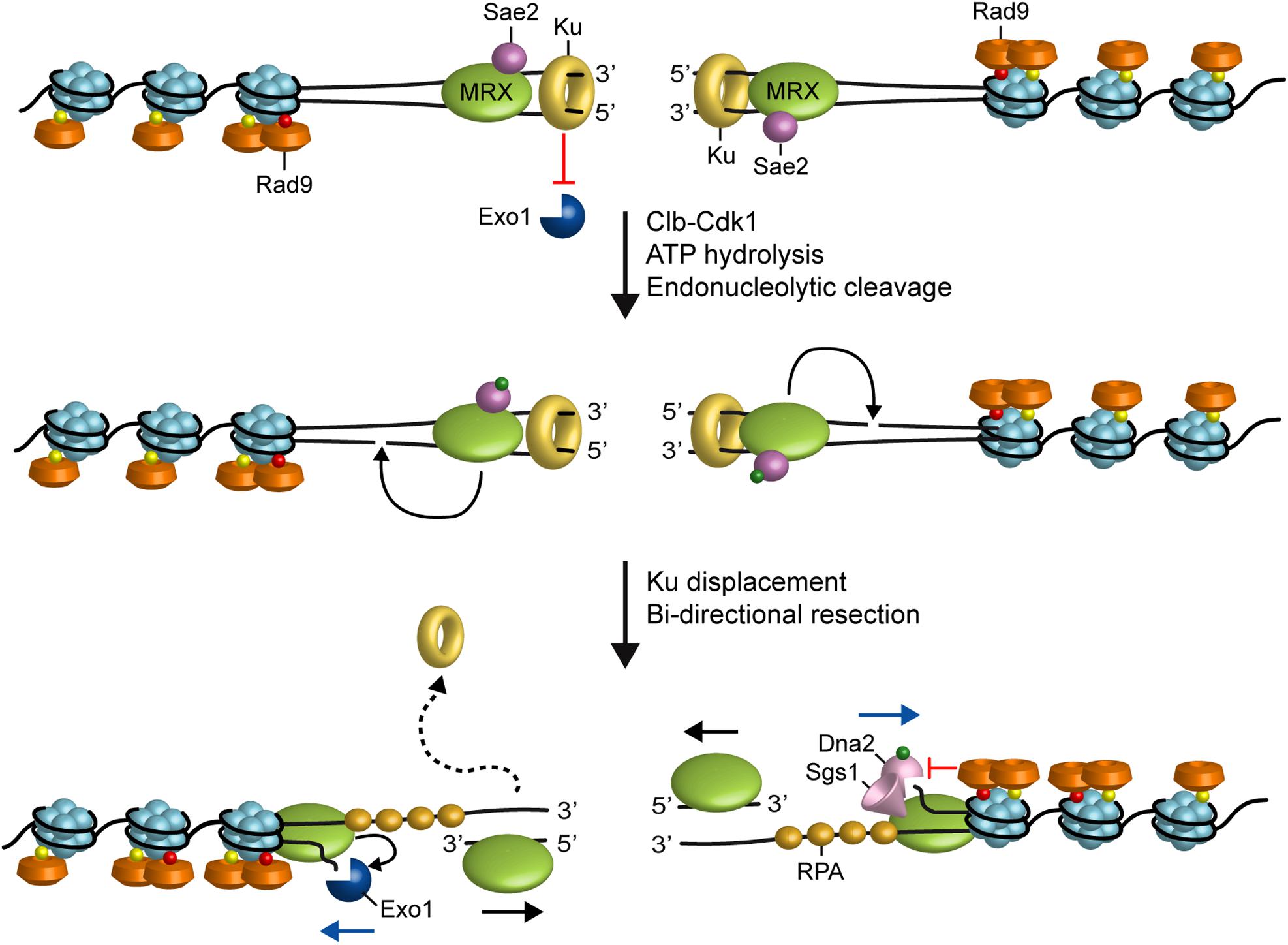

In the current model for resection, the Sae2 protein (CtIP in mammals) activates a latent dsDNA-specific endonuclease activity of Mre11 within the context of the MRX complex to incise the 5′-terminated dsDNA strands at both DNA ends (Cannavo and Cejka, 2014). The resulting nick generates an entry site for the Mre11 exonuclease to degrade back to the DSB end in the 3′–5′ direction, and for Exo1 and Dna2 nucleases to degrade DNA in the 5′–3′ direction away from the DSB end (Mimitou and Symington, 2008; Zhu et al., 2008; Cejka et al., 2010; Niu et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2011; Nimonkar et al., 2011; Shibata et al., 2014; Reginato et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Figure 1). In yeast, inactivation of either Sgs1-Dna2 or Exo1 results in only minor resection defects, whereas resection is severely compromised when the two pathways are simultaneously inactivated, indicating that they play partially overlapping functions (Mimitou and Symington, 2008; Zhu et al., 2008).

FIGURE 1. Model for resection of DNA DSBs. MRX, Sae2 and Ku are rapidly recruited to DNA ends. Ku inhibits Exo1 access to DNA ends. In the ATP-bound state, Rad50 blocks the Mre11 nuclease. After ATP hydrolysis by Rad50, Mre11 together with Sae2 phosphorylated by Cdk1 can catalyze an endonucleolytic cleavage of the 5’ strand. This incision allows processing by Exo1 and Sgs1-Dna2 in a 5’–3’ direction from the nick (blue arrows) and by MRX in a 3’–5’ direction toward the DSB ends (black arrows). MRX also promotes the association of Exo1 and Sgs1-Dna2 at DNA ends, whereas Rad9 inhibits the resection activity of Sgs1-Dna2. Red dots indicate phosphorylation events by Mec1 and Tel1, green dots indicate phosphorylation events by Cdk1 and yellow dots indicate methylation of histone H3.

The efficiency of 5′ DNA end cleavage in vitro by MRX-Sae2 was shown to be strongly enhanced by the presence of protein blocks at DNA ends (Cannavo and Cejka, 2014; Anand et al., 2016; Deshpande et al., 2016). It has been proposed that the endonucleolytic cleavage catalyzed by MRX-Sae2 allows the resection machinery to bypass end-binding factors that can be present at the break end and restrict the accessibility of DNA ends to Exo1 and Sgs1-Dna2. These end-binding factors includes Spo11, which cleaves DNA by a topoisomerase-like transesterase mechanism and remains covalently attached to the 5′ end of meiotic DSBs, trapped topoisomerases, or the Ku complex (see the next paragraph) (Neale et al., 2005; Bonetti et al., 2010; Mimitou and Symington, 2010; Langerak et al., 2011; Chanut et al., 2016).

While Exo1 shows 5′–3′ exonuclease activity capable to release mononucleotide products from a dsDNA end (Tran et al., 2002), Dna2 has an endonuclease activity that can cleave either 3′ or 5′ overhangs adjoining a duplex DNA (Kao et al., 2004). The resection activity of Dna2 relies on the RecQ helicase Sgs1 (BLM in humans) that provides the substrates for Dna2 by unwinding the dsDNA (Zhu et al., 2008; Cejka et al., 2010; Niu et al., 2010; Nimonkar et al., 2011). Furthermore, RPA directs the resection activity of Dna2 to the 5′ strand by binding and protecting the 3′ strand to Dna2 access (Cejka et al., 2010; Niu et al., 2010). In both yeast and humans, Dna2 contains also a helicase domain that can function as a ssDNA translocase to facilitate the degradation of 5′-terminated DNA by the nuclease activity of the enzyme (Levikova et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2017).

In addition to the end-clipping function, the MRX complex also stimulates resection by Exo1 and Sgs1-Dna2 both in vitro and in vivo (Cejka et al., 2010; Nicolette et al., 2010; Niu et al., 2010; Shim et al., 2010; Nimonkar et al., 2011). Biochemical experiments have shown that MRX enhances the ability of Sgs1 to unwind dsDNA, possibly by increasing Sgs1 association to DNA ends. Furthermore, MRX enhances both the affinity to DNA ends and the processivity of Exo1 (Cejka et al., 2010; Nicolette et al., 2010; Niu et al., 2010; Nimonkar et al., 2011; Cannavo et al., 2013). The MRX function in promoting Sgs1-Dna2 and Exo1 resection activities does not require Mre11 nuclease, suggesting that it does involve the Mre11 end-clipping activity (Shim et al., 2010).

Interestingly, MRX possesses an ATP-dependent unwinding activity capable of releasing a short oligonucleotide from dsDNA (Paull and Gellert, 1999; Cannon et al., 2013) and the recent identification of the hypermorphic mre11-R10T mutation has allowed us to demonstrate that this strand-separation function of MRX is important to stimulate Exo1 resection activity (Gobbini et al., 2018). In particular, Mre11-R10T mutant variant, whose single aminoacid substitution is located in the first Mre11 phosphodiesterase domain, accelerates DSB resection compared to wild type Mre11 by potentiating the processing activity of Exo1, whose association to DSBs is increased in mre11-R10T cells. Molecular dynamic simulations have shown that the two capping domains of wild type Mre11 dimer rapidly interact with the DNA ends and cause a partial unwinding of the dsDNA molecule. The Mre11-R10T dimer undergoes an abnormal rotation that leads one of the capping domain to wedge in between the two DNA strands and to persistently melt the dsDNA ends (Gobbini et al., 2018). These findings support a model in which MRX can directly stimulate Exo1 activity by promoting local unwinding of the DSB DNA end that facilitates Exo1 persistence on DNA. Although Exo1 is a processive nuclease in vitro, single-molecule fluorescence imaging has shown that it is rapidly stripped from DNA by RPA (Myler et al., 2016), suggesting that multiple cycles of Exo1 rebinding at the same DNA end would be required for extensive resection. Therefore, this MRX function in the stimulation of Exo1 activity at DNA ends can be of benefit to increase the processivity of Exo1 in the presence of RPA.

Positive and Negative Regulation of Nuclease Action at Dna Double-Strand Breaks

Homologous recombination is generally restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, when a sister chromatid is present as repair template (Aylon et al., 2004; Ira et al., 2004). This restriction is mainly caused by reduced end resection in G1 compared to G2. Reduced resection in G1 is due to both Ku binding to DNA ends and low cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk1 in S. cerevisiae) activity (Aylon et al., 2004; Ira et al., 2004; Clerici et al., 2008; Zierhut and Diffley, 2008). Elimination of Ku in G1 (where Cdk1 activity is low) allows Cdk1-independent DSB resection that is limited to the break-proximal sequence, whereas the absence of Ku does not enhance DSB processing in G2 (where Cdk1 activity is high) (Clerici et al., 2008). Furthermore, inhibition of Cdk1 activity in G2 prevents DSB resection in wild type but not in kuΔ cells (Clerici et al., 2008). These findings suggest that Cdk1 activity is required for resection initiation when Ku is present. However, the finding that Cdk1 inhibition in G2-arrested kuΔ cells allows only short but not long-range resection (Clerici et al., 2008) suggests the existence of other Cdk1 targets to allow extensive resection. Consistent with this hypothesis, Cdk1 was shown to promote short- and long-range resection by phosphorylating and activating Sae2 and Dna2, respectively. In fact, substitution of Cdk1-dependent phosphorylation residues in Sae2 causes a delay of DSB resection initiation, while mutations of Cdk1-target sites in Dna2 cause a defect in long-range resection (Huertas et al., 2008; Huertas and Jackson, 2009; Manfrini et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011).

Subsequent experiments have shown that the Ku complex is rapidly recruited to DSBs and protects the DNA ends from degradation by Exo1 (Figure 1). The absence of Ku partially suppresses both the hypersensitivity to DSB-inducing agents and the resection defect of mre11Δ and sae2Δ cells in an Exo1-dependent fashion (Mimitou and Symington, 2010; Foster et al., 2011; Langerak et al., 2011). This finding suggests that Sae2, once phosphorylated by Cdk1, promotes resection initiation by supporting MRX function in removing Ku from the DSB ends. As Ku preferentially binds dsDNA ends over ssDNA (Griffith et al., 1992), the MRX-Sae2 endonucleolytic activity could limit DSB association of Ku by creating a DNA substrate less suitable for Ku engagement (Mimitou and Symington, 2010; Langerak et al., 2011; Chanut et al., 2016). On the other hand, as the absence of MRX, but not of Sae2 or Mre11 nuclease activity, increases Ku association at DNA ends (Zhang et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2008; Shim et al., 2010), MRX could compete with Ku for end binding. However, the finding that hyperactivation of Exo1 resection activity by the Mre11-R10T mutant variant leads to Ku dissociation from DSB ends and Cdk1-independent DSB resection close to the DSB end suggests that MRX can limit Ku association to DNA ends also indirectly by promoting Exo1 resection activity (Gobbini et al., 2018).

In addition to Ku, the Rad9 protein, originally identified as adaptor for activation of Rad53 checkpoint kinase (Sweeney et al., 2005), inhibits DSB resection (Bonetti et al., 2015; Ferrari et al., 2015; Figure 1). The lack of Rad9 suppresses the resection defect of Sae2-deficient cells and increases the resection efficiency also in a wild type context (Bonetti et al., 2015; Ferrari et al., 2015). Both these effects occur in a Sgs1-Dna2-dependent fashion, indicating that Rad9 inhibits mainly the resection activity of Sgs1-Dna2 by limiting Sgs1 association to DSBs. Further support for a role of Rad9 in Sgs1-Dna2 inhibition comes from the identification of the hypermorphic Sgs1-G1298R mutant variant, which potentiates the Dna2 resection activity by escaping the inhibition that Rad9 exerts on Sgs1 (Bonetti et al., 2015).

Recruitment of Rad9 to chromatin involves multiple pathways. The TUDOR domain of Rad9 interacts with histone H3 methylated at K79 (H3-K79me) (Giannattasio et al., 2005; Wysocki et al., 2005; Grenon et al., 2007). Rad9 binding to the sites of damage is strengthened through an interaction of its tandem-BRCT domain with histone H2A phosphorylated at S129 (γH2A) by Mec1 and Tel1 checkpoint kinases (Downs et al., 2000; Shroff et al., 2004; Toh et al., 2006; Hammet et al., 2007). Finally, phosphorylation of Rad9 by Cdk1 leads to Rad9 interaction with the multi-BRCT domain protein Dpb11 (TopBP1 in mammals), which mediates histone-independent Rad9 association to the sites of damage (Granata et al., 2010; Pfander and Diffley, 2011).

Rad9 association to DSB ends is counteracted by the Swr1-like family remodeler Fun30 (SMARCAD1 in mammals) (Chen et al., 2012; Costelloe et al., 2012; Eapen et al., 2012; Bantele et al., 2017) and the scaffold protein complex Slx4-Rtt107 (Dibitetto et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017), both of which promote DSB resection (Chen et al., 2012; Dibitetto et al., 2016). The Slx4-Rtt107 complex limits Rad9 binding near a DSB possibly by competing with Rad9 for interaction with Dpb11 and γH2A (Ohouo et al., 2013; Dibitetto et al., 2016).

DNA Damage Checkpoint Regulation of Nuclease Action at Double-Strand Breaks

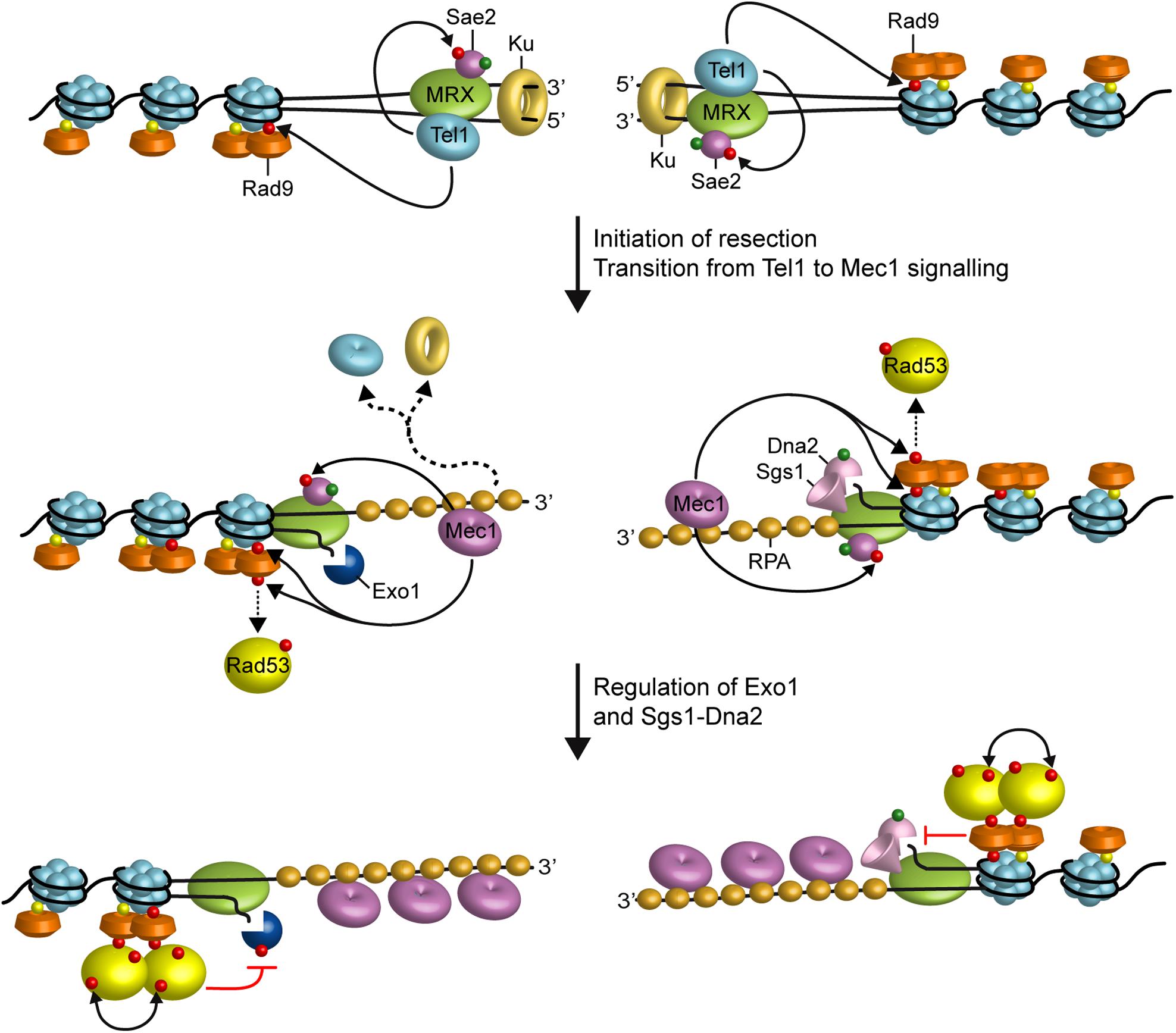

Generation of DNA DSBs triggers the activation of the DNA damage checkpoint, whose key players include the S. cerevisiae protein kinases Mec1 (ATR in mammals) and Tel1 (ATM in mammals) (Gobbini et al., 2013). In both yeast and mammals, Tel1/ATM is activated by the MRX/MRN complex, which is required for Tel1/ATM recruitment to the site of damage through direct interaction between Tel1/ATM with the Xrs2 subunit (Nakada et al., 2003; Falck et al., 2005; Lee and Paull, 2005; You et al., 2005). By contrast, Mec1/ATR activation depends on its interactor Ddc2 (ATRIP in mammals) (Paciotti et al., 2000). While blunt or minimally processed DSB ends are preferential substrates for Tel1/ATM (Shiotani and Zou, 2009), RPA-coated ssDNA is the structure that enables Mec1/ATR to recognize DNA (Zou and Elledge, 2003). In both yeast and mammals, as the single-stranded 3′ overhangs increase in length, Mec1/ATR activation is coupled with loss of ATM/Tel1 activation, suggesting that DSB resection promotes a switch from a Tel1/ATM- to a Mec1/ATR-dependent checkpoint (Mantiero et al., 2007; Shiotani and Zou, 2009; Figure 2). The substrates for Mec1 and Tel1 are largely overlapping and include H2A, Rad53/CHK2, Chk1, Rad9/53BP1, Sae2/CtIP, Dna2, and RPA (Ciccia and Elledge, 2010).

FIGURE 2. Interplays between end resection and checkpoint. Rad9 is already bound to chromatin via interaction with methylated histone H3 (yellow dots). When a DSB occurs, MRX, Sae2, and Ku localize to the DSB ends. MRX bound to DNA ends recruits and activates Tel1, which in turn promotes DSB resection by phosphorylating Sae2 and stabilizing MRX association to DNA ends. Tel1 also contributes to the recruitment of Rad9 to the DSB ends by phosphorylating H2A. Initiation of DSB resection by MRX-Sae2, Exo1, and Sgs1-Dna2 generate ssDNA tails that promotes a switch from Tel1 to Mec1 signaling. Activated Mec1 contributes to phosphorylate H2A that leads to a further enrichment of Rad9 at DSBs, which counteracts directly Sgs1-Dna2 resection activity. Mec1 also phosphorylates Rad9, which in turn allows Rad53 in-trans autophosphorylation and activation (double black arrows). Activated Rad53 limits DSB resection by phosphorylating and inhibiting Exo1. Phosphorylation events by Mec1 and Tel1 are indicated by red dots, whereas green dots indicate phosphorylation events by Cdk1.

The DNA damage checkpoint regulates the generation of 3′–ended ssDNA at DNA ends in both positive and negative fashions. Cells lacking Tel1 slightly reduce the efficiency of DSB resection (Mantiero et al., 2007). Tel1, which is loaded at DSBs by MRX, supports MRX persistence at DSBs in a positive feedback loop (Cassani et al., 2016), suggesting that it can facilitates DSB resection by promoting MRX function. Interestingly, Tel1 exerts this role independently of its kinase activity (Cassani et al., 2016), suggesting that it plays a structural role in stabilizing MRX retention to DSBs.

In contrast to tel1Δ cells, cells lacking Mec1 accelerate the generation of ssDNA at the DSBs, whereas the same process is impaired by the mec1-ad allele (Clerici et al., 2014), indicating that Mec1 inhibits DSB resection. Mec1 exerts this function at least in two ways: (i) it induces Rad53-dependent phosphorylation of Exo1 that leads to the inhibition of Exo1 activity (Jia et al., 2004; Morin et al., 2008), (ii) it promotes retention of the resection inhibitor Rad9 at DNA DSBs through phosphorylation of H2A on serine 129 (Eapen et al., 2012; Clerici et al., 2014; Gobbini et al., 2015). The association of Rad9 at DSBs and therefore the inhibition of DSB resection is promoted also by the checkpoint sliding clamp Ddc1-Mec3-Rad17 (9-1-1 in mammals) complex (Ngo and Lydall, 2015), which is required for full Mec1 activation and binds to the ssDNA-dsDNA junction at DNA ends (Gobbini et al., 2013).

Both Mec1 and 9-1-1 have also a positive role in DSB resection. In fact, Mec1 is known to phosphorylate Sae2 and this phosphorylation is important for Sae2 function in resection of both mitotic and meiotic DSBs (Baroni et al., 2004; Cartagena-Lirola et al., 2006). Furthermore, Mec1 also phosphorylates Slx4 and this phosphorylation favors DSB resection by promoting Dpb11-Slx4-Rtt107 complex formation that leads to a destabilization of Rad9 association at DSBs (Smolka et al., 2007; Ohouo et al., 2013; Dibitetto et al., 2016).

Finally, in the absence of Rad9, the 9-1-1 complex facilitates DSB resection by stimulating both Dna2-Sgs1 and Exo1 through an unknown mechanism (Ngo et al., 2014). This effect of 9-1-1 is conserved, as also the human 9-1-1 complex stimulates the activities of DNA2 and EXO1 in vitro (Ngo et al., 2014).

In yeast, the checkpoint response to DNA DSBs depends primarily on Mec1. However, if resection initiation is delayed, for example, in the sae2Δ mutant, MRX persistence at DSBs is increased, Tel1 is hyperactivated and the mec1Δ checkpoint defect is partially bypassed (Usui et al., 2001; Clerici et al., 2006). This persistent checkpoint activation caused by enhanced MRX and Tel1 signaling activity at DSBs contributes to the DNA damage hypersensitivity and the resection defect of Sae2-deficient cells by increasing Rad9 persistence at DSBs. In fact, mre11 mutant alleles that reduce MRX binding to DSBs restore DNA damage resistance and resection in sae2Δ cells (Chen et al., 2015; Puddu et al., 2015; Cassani et al., 2018). Furthermore, reduction in Tel1 binding to DNA ends or abrogation of its kinase activity restores DNA damage resistance in sae2Δ cells (Gobbini et al., 2015). Similarly, impairment of Rad53 activity either by affecting its interaction with Rad9 or by abolishing its kinase activity suppresses the sensitivity to DNA damaging agents and the resection defect of sae2Δ cells (Gobbini et al., 2015). The bypass of Sae2 function by Rad53 and Tel1 impairment is due to decreased amount of Rad9 bound at the DSBs (Gobbini et al., 2015). As Rad9 inhibits Sgs1-Dna2 (Bonetti et al., 2015; Ferrari et al., 2015), reduced Rad9 association at DSBs increases the resection efficiency by relieving Sgs1-Dna2 inhibition.

Altogether, these findings support a model whereby the binding of MRX to DNA ends drives the recruitment of Tel1, which facilitates initiation of end resection by phosphorylating Sae2 and promoting MRX association to DNA ends (Figure 2). Generation of RPA-coated ssDNA leads to the recruitment of Mec1-Ddc2, which in turn phosphorylates Rad9, Rad53, and H2A. γH2A generation promotes the enrichment of Rad9 to the DSB ends, which limits the resection activity of Dna2-Sgs1. Rad9 association at DSBs also leads to the inhibition of Exo1 activity indirectly by allowing activation of Rad53, which in turn phosphorylates and inhibits Exo1 (Figure 2).

This Mec1-mediated inhibition of nuclease action at DSBs avoids excessive generation of ssDNA, which can form secondary structures that can be attacked by structure-selective endonucleases, leading to chromosome fragmentation. Furthermore, since Mec1 is activated by RPA-coated ssDNA, inhibition of end resection by Mec1 keeps under control Mec1 itself. This negative feedback loop may avoid excessive checkpoint activation to ensure a rapid checkpoint turning off to either resume cell cycle progression when the DSB is repaired or adapt to DSBs as a final attempt at survival after cells have exhausted repair options.

Nuclease Action at the Replication Forks

Accurate and complete DNA replication is essential for the maintenance of genome stability. However, progression of replication forks is constantly challenged by various types of replication stress that generally causes a slowing or stalling of replication forks (Giannattasio and Branzei, 2017; Pasero and Vindigni, 2017). Replication forks can slow or stall at sites containing DNA lesions, chromatin compaction, DNA secondary structures (G-quadruplex, small inverted repeats, trinucleotides repeats), DNA/RNA hybrids and covalent protein-DNA adducts. Furthermore, clashes between transcription and replication machineries can impact genome stability even in unchallenged conditions (Giannattasio and Branzei, 2017; Pasero and Vindigni, 2017). Fork obstacles may result in dysfunctional replication forks, which lack their replication-competent state and necessitate additional mechanisms to resume DNA synthesis. Failure to resume DNA synthesis results in the generation of DNA DSBs, a major source of the genome rearrangements (Liu et al., 2012).

A general feature of stalled replication forks is the accumulation of ssDNA that can originate from physical uncoupling between the polymerase and the replicative helicase or between the leading and the lagging strand polymerases (Pagès and Fuchs, 2003; Byun et al., 2005; Lopes et al., 2006). The accumulation of torsional stress ahead of replication forks (Katou et al., 2003; Bermejo et al., 2011; Gan et al., 2017) can also lead to the annealing of the two newly synthesized strands and the formation of a four-way structure resembling a Holliday junction (i.e., fork reversal), which might expose DNA ends to exonucleolytic processing (Sogo et al., 2002). These tracts of ssDNA coated by the RPA complex recruit the checkpoint kinase Mec1/ATR (Zou and Elledge, 2003), whose activation prevents entry into mitosis, increases the intracellular dNTP pools, represses late origin firing, maintains replisome stability and orchestrates different pathways of replication fork restart/stabilization (Giannattasio and Branzei, 2017; Pasero and Vindigni, 2017).

In both yeast and mammals, the same nucleases involved in DSB resection are emerging as key factors for the processing of replication intermediates to allow repair/restart of stalled replication forks and/or to prevent accumulation of DSBs (Cotta-Ramusino et al., 2005; Segurado and Diffley, 2008; Tsang et al., 2014; Thangavel et al., 2015; Colosio et al., 2016). Indeed, the ability of Mre11, Sae2, Dna2, and Exo1 to resect dsDNA ends is relevant to prevent the accumulation of replication-associated DSBs by promoting DSB repair by HR (Costanzo et al., 2001; Cotta-Ramusino et al., 2005; Segurado and Diffley, 2008; Hashimoto et al., 2012; Tsang et al., 2014; Yeo et al., 2014; Thangavel et al., 2015; Colosio et al., 2016; Ait Saada et al., 2017). In addition, controlled Dna2-mediated degradation of replication forks is a relevant mechanism to mediate reversed fork restart (Thangavel et al., 2015).

Although the nucleolytic processing of nascent strands at stalled replication forks is important to resume DNA synthesis, unrestricted nuclease access can also promote extensive and uncontrolled degradation of stalled replication intermediates and genome instability (Pasero and Vindigni, 2017). In budding yeast, the checkpoint activated by the ssDNA that arise at stalled replication forks plays a role in protecting replication intermediates from aberrant nuclease activity (Tercero and Diffley, 2001; Alabert et al., 2009; Barlow and Rothstein, 2009). In fact, in the absence of the checkpoint, relieve of Exo1 inhibition by Rad53 leads to the formation of long ssDNA gaps and fork collapse (Sogo et al., 2002; Cotta-Ramusino et al., 2005; Segurado and Diffley, 2008). Furthermore, replication stress in ATR-defective Schizosaccharomyces pombe and mammalian cells results in MRE11- and EXO1-dependent ssDNA accumulation (Hu et al., 2012; Koundrioukoff et al., 2013; Tsang et al., 2014). Interestingly, in S. cerevisiae, Tel1/ATM was recently found to counteract nucleolytic degradation by Mre11 of replication forks that reverse upon treatment with camptothecin (CPT) (Menin et al., 2018), which leads to accumulation of torsional stress by blocking Top1 on DNA (Postow et al., 2001; Koster et al., 2007; Ray Chaudhuri et al., 2012). Fork reversal in CPT is promoted by the replisome component Mrc1, whose inactivation prevents fork reversal in both wild type and TEL1 deleted cells (Menin et al., 2018).

Interestingly, the same negative regulators of DSB resection limit nuclease action also at the replication forks. In yeast, Rad9, which is known to counteract the resection activity of Sgs1-Dna2, is important to protect stalled replication forks from detrimental Dna2-mediated degradation when Mec1/ATR is not fully functional (Villa et al., 2018). This Rad9 protective function relies mainly on the interaction of Rad9 with Dpb11, which is recruited to stalled replication forks at origin-proximal regions (Balint et al., 2015). Similarly, human cells lacking 53BP1, the mammalian Rad9 ortholog, are hypersensitive to DNA replication stress and show degradation of nascent replicated DNA (Her et al., 2018). Furthermore, the Ku heterodimer was shown to be recruited to terminally arrested replication forks and to regulate their resection in S. pombe (Teixeira-Silva et al., 2017). The lack of Ku leads to extensive Exo1-mediated fork resection, a reduced recruitment of RPA and Rad51 and a delay of fork-restart, suggesting that arrested replication forks undergo fork reversal that provides a substrate for Ku binding.

In addition to the checkpoint, other proteins are devoted to protect replication forks from degradation in mammalian cells. The absence of proteins involved in HR or in the Fanconi anemia network, including FAN1, FANCD2, RAD51, BRCA1, and BRCA2, leads to uncontrolled DNA degradation by MRE11 and EXO1 (Howlett et al., 2005; Hashimoto et al., 2010; Schlacher et al., 2011, 2012; Ying et al., 2012; Chaudhury et al., 2014; Karanja et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2016; Kais et al., 2016; Kolinjivadi et al., 2017; Lemaçon et al., 2017; Mijic et al., 2017; Taglialatela et al., 2017). Furthermore, loss of the WRN exonuclease activity enhances degradation at nascent DNA strands by EXO1 and MRE11 (Su et al., 2014; Iannascoli et al., 2015), whereas cells depleted of the biorientation defect 1-like (BOD1L) protein exhibit a DNA2-dependent degradation of stalled/damaged replication forks (Higgs et al., 2015).

Conclusion

Defects in HR and DNA replication underlie a significant proportion of the genomic instability observed in cancer cells. Furthermore, ssDNA formed at DSBs and at replication forks can be source of clustered mutations, frequently occurring during carcinogenesis, and of error-prone repair events that can cause DNA deletions or translocations (Nik-Zainal et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2012; Alexandrov et al., 2013; Sakofsky et al., 2014). Therefore, there is a growing interest in understanding how ssDNA is generated at both DSBs and replication forks and how its generation is regulated. Mounting evidence indicates that processing of both DSB ends and replication forks is regulated both positively and negatively by several proteins involved also in the DNA damage checkpoint, thus coupling resection with checkpoint activation. Given the importance to maintain genome stability, advancements in delineating the mechanisms that control nuclease action at both DSBs and replication forks will have far-reaching implications for human health.

Author Contributions

MPL conceived the idea. DB and MPL wrote the manuscript. CVC and MC revised and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) (IG Grant 19783) and Progetti di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) 2015 to MPL.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Longhese lab for helpful discussions.

References

Ait Saada, A., Teixeira-Silva, A., Iraqui, I., Costes, A., Hardy, J., Paoletti, G., et al. (2017). Unprotected replication forks are converted into mitotic sister chromatid bridges. Mol. Cell 66, 398–410.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.04.002

Alabert, C., Bianco, J. N., and Pasero, P. (2009). Differential regulation of homologous recombination at DNA breaks and replication forks by the Mrc1 branch of the S-phase checkpoint. EMBO J. 28, 1131–1141. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.75

Alexandrov, L. B., Nik-Zainal, S., Wedge, D. C., Aparicio, S. A., Behjati, S., Biankin, A. V., et al. (2013). Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477

Anand, R., Ranjha, L., Cannavo, E., and Cejka, P. (2016). Phosphorylated CtIP functions as a co-factor of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 endonuclease in DNA end resection. Mol. Cell 64, 940–950. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.10.017

Aylon, Y., Liefshitz, B., and Kupiec, M. (2004). The CDK regulates repair of double-strand breaks by homologous recombination during the cell cycle. EMBO J. 23, 4868–4875. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600469

Balint, A., Kim, T., Gallo, D., Cussiol, J. R., Bastos de Oliveira, F. M., Yimit, A., et al. (2015). Assembly of Slx4 signaling complexes behind DNA replication forks. EMBO J. 34, 2182–2197. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591190

Bantele, S. C., Ferriera, P., Gritenaite, D., Boos, D., and Pfander, B. (2017). Targeting of the Fun30 nucleosome remodeller by the Dpb11 scaffold facilitates cell cycle-regulated DNA end resection. eLife 6:e21687. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21687

Barlow, J. H., and Rothstein, R. (2009). Rad52 recruitment is DNA replication independent and regulated by Cdc28 and the Mec1 kinase. EMBO J. 28, 1121–1130. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.43

Baroni, E., Viscardi, V., Cartagena-Lirola, H., Lucchini, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2004). The functions of budding yeast Sae2 in the DNA damage response require Mec1- and Tel1-dependent phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24,4151–4165. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4151-4165.2004

Bermejo, R., Capra, T., Jossen, R., Colosio, A., Frattini, C., Carotenuto, W., et al. (2011). The replication checkpoint protects fork stability by releasing transcribed genes from nuclear pores. Cell 146, 233–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.033

Bonetti, D., Clerici, M., Manfrina, N., Lucchini, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2010). The MRX complex plays multiple functions in resection of Yku- and Rif2-protected DNA ends. PLoS One 5:e14142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014142

Bonetti, D., Villa, M., Gobbini, E., Cassani, C., Tedeschi, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2015). Escape of Sgs1 from Rad9 inhibition reduces the requirement for Sae2 and functional MRX in DNA end resection. EMBO Rep. 16, 351–361. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439764

Bressan, D. A., Olivares, H. A., Nelms, B. E., and Petrini, J. H. (1998). Alteration of N-terminal phosphoesterase signature motifs inactivates Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11. Genetics 150, 591–600.

Byun, T. S., Pacek, M., Yee, M. C., Walter, J. C., and Cimprich, K. A. (2005). Functional uncoupling of MCM helicase and DNA polymerase activities activates the ATR-dependent checkpoint. Genes Dev. 19, 1040–1052. doi: 10.1101/gad.1301205

Cannavo, E., and Cejka, P. (2014). Sae2 promotes dsDNA endonuclease activity within Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 to resect DNA breaks. Nature 514, 122–125. doi: 10.1038/nature13771

Cannavo, E., Cejka, P., and Kowalczykowski, S. C. (2013). Relationship of DNA degradation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae Exonuclease 1 and its stimulation by RPA and Mre11-Rad50Xrs2 to DNA end resection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E1661–E1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305166110

Cannon, B., Kuhnlein, J., Yang, S. H., Cheng, A., Schindler, D., Stark, J. M., et al. (2013). Visualization of local DNA unwinding by Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 using single-molecule FRET. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18868–18873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309816110

Cartagena-Lirola, H., Guerini, I., Viscardi, V., Lucchini, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2006). Budding yeast Sae2 is an in vivo target of the Mec1 and Tel1 checkpoint kinases during meiosis. Cell Cycle 5, 1549–1559. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.14.2916

Cassani, C., Gobbini, E., Vertemara, J., Wang, W., Marsella, A., Sung, P., et al. (2018). Structurally distinct Mre11 domains mediate MRX functions in resection, end-tethering and DNA damage resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 2990–3008. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky086

Cassani, C., Gobbini, E., Wang, W., Niu, H., Clerici, M., Sung, P., et al. (2016). Tel1 and Rif2 regulate MRX functions in end-tethering and repair of DNA double-strand breaks. PLoS Biol. 14:e1002387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002387

Cejka, P. (2015). DNA end resection: nucleases team up with the right partners to initiate homologous recombination. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 22931–22938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.675942

Cejka, P., Cannavo, E., Polaczek, P., Masuda-Sasa, T., Pokharel, S., Campbell, J. L., et al. (2010). DNA end resection by Dna2-Sgs1-RPA and its stimulation by Top3-Rmi1 and Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2. Nature 467, 112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature09355

Chanut, P., Britton, S., Coates, J., Jackson, S. P., and Calsou, P. (2016). Coordinated nuclease activities counteract Ku at single-ended DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Commun. 7:12889. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12889

Chaudhury, I., Stroik, D. R., and Sobeck, A. (2014). FANCD2-controlled chromatin access of the Fanconi-associated nuclease FAN1 is crucial for the recovery of stalled replication orks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 3939–3954. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00457-14

Chen, H., Donnianni, R. A., Handa, N., Deng, S. K., Oh, J., Timashev, L. A., et al. (2015). Sae2 promotes DNA damage resistance by removing the Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 complex from DNA and attenuating Rad53 signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 1880–1887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503331112

Chen, X., Bosques, L., Sung, P., and Kupfer, G. M. (2016). A novel role for non-ubiquitinated FANCD2 in response to hydroxyurea-induced DNA damage. Oncogene 35, 22–34. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.68

Chen, X., Cui, D., Papusha, A., Zhang, X., Chu, C. D., Tang, J., et al. (2012). The Fun30 nucleosome remodeller promotes resection of DNA double-strand break ends. Nature 489, 576–580. doi: 10.1038/nature11355

Chen, X., Niu, H., Chung, W. H., Zhu, Z., Papusha, A., Shim, E. Y., et al. (2011). Cell cycle regulation of DNA double-strand break end resection by Cdk1-dependent Dna2 phosphorylation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 1015–1019. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2105

Chiruvella, K. K., Liang, Z., and Wilson, T. E. (2013). Repair of double-strand breaks by end joining. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5:a012757. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012757

Ciccia, A., and Elledge, S. J. (2010). The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell 40, 179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019

Clerici, M., Mantiero, D., Guerini, I., Lucchini, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2008). The Yku70-Yku80 complex contributes to regulate double-strand break processing and checkpoint activation during the cell cycle. EMBO Rep. 9, 810–818. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.121

Clerici, M., Mantiero, D., Lucchini, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2006). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sae2 protein negatively regulates DNA damage checkpoint signalling. EMBO Rep. 7, 212–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400593

Clerici, M., Trovesi, C., Galbiati, A., Lucchini, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2014). Mec1/ATR regulates the generation of single-stranded DNA that attenuates Tel1/ATM signaling at DNA ends. EMBO J. 33, 198–216. doi: 10.1002/embj.201386041

Colosio, A., Frattini, C., Pellicanò, G., Villa-Hernández, S., and Bermejo, R. (2016). Nucleolytic processing of aberrant replication intermediates by an Exo1-Dna2-Sae2 axis counteracts fork collapse-driven chromosome instability. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 10676–10690. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw858

Costanzo, V., Robertson, K., Bibikova, M., Kim, E., Grieco, D., Gottesman, M., et al. (2001). Mre11 protein complex prevents double-strand break accumulation during chromosomal DNA replication. Mol. Cell 8, 137–147. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00294-5

Costelloe, T., Louge, R., Tomimatsu, N., Mukherjee, B., Martini, E., Khadaroo, B., et al. (2012). The yeast Fun30 and human SMARCAD1 chromatin remodellers promote DNA end resection. Nature 489, 581–584. doi: 10.1038/nature11353

Cotta-Ramusino, C., Fachinetti, D., Lucca, C., Doksani, Y., Lopes, M., Sogo, J., et al. (2005). Exo1 processes stalled replication forks and counteracts fork reversal in checkpoint-defective cells. Mol. Cell 17, 153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.032

de Jager, M., van Noort, J., van Gent, D. C., Dekker, C., Kanaar, R., and Wyman, C. (2001). Human Rad50/Mre11 is a flexible complex that can tether DNA ends. Mol. Cell 8, 1129–1135. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00381-1

Deshpande, R. A., Lee, J. H., Arora, S., and Paull, T. T. (2016). Nbs1 converts the human Mre11/Rad50 nuclease complex into an endo/exonuclease machine specific for protein-DNA adducts. Mol. Cell 64, 593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.10.010

Deshpande, R. A., Williams, G. J., Limbo, O., Williams, R. S., Kuhnlein, J., Lee, J. H., et al. (2014). ATP-driven Rad50 conformations regulate DNA tethering, end resection, and ATM checkpoint signaling. EMBO J. 33, 482–500. doi: 10.1002/embj.201386100

Dibitetto, D., Ferrari, M., Rawal, C. C., Balint, A., Kim, T. H., Zhang, Z., et al. (2016). Slx4 and Rtt107 control checkpoint signalling and DNA resection at double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 669–682. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1080

Downs, J. A., Lowndes, N. F., and Jackson, S. P. (2000). A role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone H2A in DNA repair. Nature 408, 1001–1004. doi: 10.1038/35050000

Eapen, V. V., Sugawara, N., Tsabar, M., Wu, W. H., and Haber, J. E. (2012). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromatin remodeler Fun30 regulates DNA end resection and checkpoint deactivation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 4727–4740. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00566-12

Falck, J., Coates, J., and Jackson, S. P. (2005). Conserved modes of recruitment of ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damage. Nature 434, 605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature03442

Ferrari, M., Dibitetto, D., De Gregorio, G., Eapen, V. V., Rawal, C. C., Lazzaro, F., et al. (2015). Functional interplay between the 53BP1-ortholog Rad9 and the Mre11 complex regulates resection, end-tethering and repair of a double-strand break. PLoS Genet. 11:e1004928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004928

Foster, S. S., Balestrini, A., and Petrini, J. H. J. (2011). Functional interplay of the Mre11 nuclease and Ku in the response to replication-associated DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 4379–4389. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05854-11

Gan, H., Yu, C., Devbhandari, S., Sharma, S., Han, J., Chabes, A., et al. (2017). Checkpoint kinase Rad53 couples leading- and lagging-strand DNA synthesis under replication stress. Mol. Cell 68, 446–455.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.018

Garcia, V., Phelps, S. E. L., Gray, S., and Neale, M. J. (2011). Bidirectional resection of DNA double-strand breaks by Mre11 and Exo1. Nature 479, 241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature10515

Giannattasio, M., and Branzei, D. (2017). S-phase checkpoint regulations that preserve replication and chromosome integrity upon dNTP depletion. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74, 2361–2380. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2474-4

Giannattasio, M., Lazzaro, F., Plevani, P., and Muzi-Falconi, M. (2005). The DNA damage checkpoint response requires histone H2B ubiquitination by Rad6-Bre1 and H3 methylation by Dot1. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9879–9886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414453200

Gobbini, E., Cassani, C., Vertemara, J., Wang, W., Mambretti, F., Casari, E., et al. (2018). The MRX complex regulates Exo1 resection activity by altering DNA end structure. EMBO J. 37:e98588. doi: 10.15252/embj.201798588

Gobbini, E., Cesena, D., Galbiati, A., Lockhart, A., and Longhese, M. P. (2013). Interplays between ATM/Tel1 and ATR/Mec1 in sensing and signaling DNA double-strand breaks. DNA Repair. 12, 791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.07.009

Gobbini, E., Villa, M., Gnugnoli, M., Menin, L., Clerici, M., and Longhese, M. P. (2015). Sae2 function at DNA double-strand breaks is bypassed by dampening Tel1 or Rad53 activity. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005685

Granata, M., Lazzaro, F., Novarina, D., Panigada, D., Puddu, F., Abreu, C. M., et al. (2010). Dynamics of Rad9 chromatin binding and checkpoint function are mediated by its dimerization and are cell cycle-regulated by CDK1 activity. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001047

Grenon, M., Costelloe, T., Jimeno, S., O’Shaughnessy, A., Fitzgerald, J., Zgheib, O., et al. (2007). Docking onto chromatin via the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad9 Tudor domain. Yeast 24, 105–119. doi: 10.1002/yea.1441

Griffith, A. J., Blier, P. R., Mimori, T., and Hardin, J. A. (1992). Ku polypeptides synthesized in vitro assemble into complexes which recognize ends of double-stranded DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 331–338.

Hammet, A., Magill, C., Heierhorst, J., and Jackson, S. P. (2007). Rad9 BRCT domain interaction with phosphorylated H2AX regulates the G1 checkpoint in budding yeast. EMBO Rep. 8, 851–857. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401036

Hashimoto, Y., Puddu, F., and Costanzo, V. (2012). RAD51- and MRE11-dependent reassembly of uncoupled CMG helicase complex at collapsed replication forks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 17–24. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2177

Hashimoto, Y., Ray Chaudhuri, A., Lopes, M., and Costanzo, V. (2010). Rad51 protects nascent DNA from Mre11-dependent degradation and promotes continuous DNA synthesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1305–1311. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1927

Her, J., Ray, C., Altshuler, J., Zheng, H., and Bunting, S. F. (2018). 53BP1 mediates ATR-Chk1 signaling and protects replication forks under conditions of replication stress. Mol. Cell. Biol 38:e00472-17. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00472-17

Higgs, M. R., Reynolds, J. J., Winczura, A., Blackford, A. N., Borel, V., Miller, E. S., et al. (2015). BOD1L is required to suppress deleterious resection of stressed replication forks. Mol. Cell 59, 462–477. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.007

Hopfner, K. P., Craig, L., Moncalian, G., Zinkel, R. A., Usui, T., Owen, B. A., et al. (2002). The Rad50 zinc-hook is a structure joining Mre11 complexes in DNA recombination and repair. Nature 418, 562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature00922

Howlett, N. G., Taniguchi, T., Durkin, S. G., D’Andrea, A. D., and Glover, T. W. (2005). The Fanconi anemia pathway is required for the DNA replication stress response and for the regulation of common fragile site stability. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 693–701. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi065

Hu, J., Sun, L., Shen, F., Chen, Y., Hua, Y., Liu, Y., et al. (2012). The intra-S phase checkpoint targets Dna2 to prevent stalled replication forks from reversing. Cell 149, 1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.030

Huertas, P., Cortés-Ledesma, F., Sartori, A. A., Aguilera, A., and Jackson, S. P. (2008). CDK targets Sae2 to control DNA-end resection and homologous recombination. Nature 455, 689–692. doi: 10.1038/nature07215

Huertas, P., and Jackson, S. P. (2009). Human CtIP mediates cell cycle control of DNA end resection and double strand break repair. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9558–9565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808906200

Iannascoli, C., Palermo, V., Murfuni, I., Franchitto, A., and Pichierri, P. (2015). The WRN exonuclease domain protects nascent strands from pathological MRE11/EXO1-dependent degradation. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 9788–9803. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv836

Ira, G., Pellicioli, A., Balijja, A., Wang, X., Fiorani, S., Carotenuto, W., et al. (2004). DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1. Nature 431, 1011–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature02964

Jia, X., Weinert, T., and Lydall, D. (2004). Mec1 and Rad53 inhibit formation of single-stranded DNA at telomeres of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cdc13-1 mutants. Genetics 166, 753–764. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.2.753

Kais, Z., Rondinelli, B., Holmes, A., O’Leary, C., Kozono, D., D’Andrea, A. D., et al. (2016). FANCD2 maintains fork stability in BRCA1/2-deficient tumors and promotes alternative end-joining DNA Repair. Cell Rep. 15, 2488–2499. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.031

Kao, H. I., Campbell, J. L., and Bambara, R. A. (2004). Dna2p helicase/nuclease is a tracking protein, like FEN1, for flap cleavage during Okazaki fragment maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50840–50849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409231200

Karanja, K. K., Lee, E. H., Hendrickson, E. A., and Campbell, J. L. (2014). Preventing over-resection by DNA2 helicase/nuclease suppresses repair defects in Fanconi anemia cells. Cell Cycle 13, 1540–1550. doi: 10.4161/cc.28476

Katou, Y., Kanoh, Y., Bando, M., Noguchi, H., Tanaka, H., Ashikari, T., et al. (2003). S-phase checkpoint proteins Tof1 and Mrc1 form a stable replication-pausing complex. Nature 424, 1078–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature01900

Kolinjivadi, A. M., Sannino, V., De Antoni, A., Zadorozhny, K., Kilkenny, M., Técher, H., et al. (2017). Smarcal1-mediated fork reversal triggers Mre11-dependent degradation of nascent DNA in the absence of Brca2 and stable Rad51 nucleofilaments. Mol. Cell 67, 867–881.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.07.001

Koster, D. A., Palle, K., Bot, E. S., Bjornsti, M. A., and Dekker, N. H. (2007). Antitumour drugs impede DNA uncoiling by topoisomerase I. Nature 448, 213–217. doi: 10.1038/nature05938

Koundrioukoff, S., Carignon, S., Técher, H., Letessier, A., Brison, O., and Debatisse, M. (2013). Stepwise activation of the ATR signaling pathway upon increasing replication stress impacts fragile site integrity. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003643

Lammens, K., Bemeleit, D. J., Möckel, C., Clausing, E., Schele, A., Hartung, S., et al. (2011). The Mre11:Rad50 structure shows an ATP-dependent molecular clamp in DNA double-strand break repair. Cell 145, 54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.038

Langerak, P., Mejia-Ramirez, E., Limbo, O., and Russell, P. (2011). Release of Ku and MRN from DNA ends by Mre11 nuclease activity and Ctp1 is required for homologous recombination repair of double-strand breaks. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002271

Lee, J. H., and Paull, T. T. (2005). ATM activation by DNA double-strand breaks through the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 complex. Science 308, 551–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1108297

Lemaçon, D., Jackson, J., Quinet, A., Brickner, J. R., Li, S., Yazinski, S., et al. (2017). MRE11 and EXO1 nucleases degrade reversed forks and elicit MUS81-dependent fork rescue in BRCA2-deficient cells. Nat. Commun. 8:860. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01180-5

Levikova, M., Pinto, C., and Cejka, P. (2017). The motor activity of DNA2 functions as an ssDNA translocase to promote DNA end resection. Genes Dev. 31, 493–502. doi: 10.1101/gad.295196.116

Lim, H. S., Kim, J. S., Park, Y. B., Gwon, G. H., and Cho, Y. (2011). Crystal structure of the Mre11-Rad50-ATPγS complex: understanding the interplay between Mre11 and Rad50. Genes Dev. 25, 1091–1104. doi: 10.1101/gad.2037811

Liu, P., Carvalho, C. M., Hastings, P. J., and Lupski, J. R. (2012). Mechanisms for recurrent and complex human genomic rearrangements. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.012

Liu, Y., Cussiol, J. R., Dibitetto, D., Sims, J. R., Twayana, S., Weiss, R. S., et al. (2017). TOPBP1Dpb11 plays a conserved role in homologous recombination DNA repair through the coordinated recruitment of 53BP1Rad9. J. Cell. Biol. 216, 623–639. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201607031

Lopes, M., Foiani, M., and Sogo, J. M. (2006). Multiple mechanisms control chromosome integrity after replication fork uncoupling and restart at irreparable UV lesions. Mol. Cell 21, 15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.015

Manfrini, N., Guerini, I., Citterio, A., Lucchini, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2010). Processing of meiotic DNA double strand breaks requires cyclin-dependent kinase and multiple nucleases. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11628–11637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104083

Mantiero, D., Clerici, M., Lucchini, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2007). Dual role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Tel1 in the checkpoint response to double-strand breaks. EMBO Rep. 8, 380–387. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400911

Mehta, A., and Haber, J. E. (2014). Sources of DNA double-strand breaks and models of recombinational DNA repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 6:a016428. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016428

Menin, L., Ursich, S., Trovesi, C., Zellweger, R., Lopes, M., Longhese, M. P., et al. (2018). Tel1/ATM prevents degradation of replication forks that reverse after topoisomerase poisoning. EMBO Rep. 19:e45535. doi: 10.15252/embr.201745535

Mijic, S., Zellweger, R., Chappidi, N., Berti, M., Jacobs, K., Mutreja, K., et al. (2017). Replication fork reversal triggers fork degradation in BRCA2-defective cells. Nat. Commun. 8:859. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01164-5

Miller, A. S., Daley, J. M., Pham, N. T., Niu, H., Xue, X., Ira, G., et al. (2017). A novel role of the Dna2 translocase function in DNA break resection. Genes Dev. 31, 503–510. doi: 10.1101/gad.295659.116

Mimitou, E. P., and Symington, L. S. (2008). Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature 455, 770–774. doi: 10.1038/nature07312

Mimitou, E. P., and Symington, L. S. (2010). Ku prevents Exo1 and Sgs1-dependent resection of DNA ends in the absence of a functional MRX complex or Sae2. EMBO J. 29, 3358–3369. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.193

Möckel, C., Lammens, K., Schele, A., and Hopfner, K. P. (2012). ATP driven structural changes of the bacterial Mre11:Rad50 catalytic head complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 914–927. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr749

Morin, I., Ngo, H. P., Greenall, A., Zubko, M. K., Morrice, N., and Lydall, D. (2008). Checkpoint-dependent phosphorylation of Exo1 modulates the DNA damage response. EMBO J. 27, 2400–2410. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.171

Myler, L. R., Gallardo, I. F., Zhou, Y., Gong, F., Yang, S. H., Wold, M. S., et al. (2016). Single-molecule imaging reveals the mechanism of Exo1 regulation by single-stranded DNA binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E1170–E1179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516674113

Nakada, D., Matsumoto, K., and Sugimoto, K. (2003). ATM-related Tel1 associates with double-strand breaks through an Xrs2-dependent mechanism. Genes Dev. 17, 1957–1962. doi: 10.1101/gad.1099003x

Neale, M. J., Pan, J., and Keeney, S. (2005). Endonucleolytic processing of covalent protein-linked DNA double-strand breaks. Nature 436, 1053–1057. doi: 10.1038/nature03872

Ngo, G. H., Balakrishnan, L., Dubarry, M., Campbell, J. L., and Lydall, D. (2014). The 9-1-1 checkpoint clamp stimulates DNA resection by Dna2-Sgs1 and Exo1. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 10516–10528. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku746

Ngo, G. H., and Lydall, D. (2015). The 9-1-1 checkpoint clamp coordinates resection at DNA double strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 5017–5032. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv409

Nicolette, M. L., Lee, K., Guo, Z., Rani, M., Chow, J. M., Lee, S. E., et al. (2010). Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 and Sae2 promote 5′ strand resection of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1478–1485. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1957

Nik-Zainal, S., Alexandrov, L. B., Wedge, D. C., Van Loo, P., Greenman, C. D., Raine, K., et al. (2012). Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell 149, 979–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.024

Nimonkar, A. V., Genschel, J., Kinoshita, E., Polaczek, P., Campbell, J. L., Wyman, C., et al. (2011). BLM-DNA2-RPA-MRN and EXO1-BLM-RPA-MRN constitute two DNA end resection machineries for human DNA break repair. Genes Dev. 25, 350–362. doi: 10.1101/gad.2003811

Niu, H., Chung, W. H., Zhu, Z., Kwon, Y., Zhao, W., Chi, P., et al. (2010). Mechanism of the ATP-dependent DNA end-resection machinery from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 467, 108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature09318

O’Driscoll, M. (2012). Diseases associated with defective responses to DNA damage. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4:a012773. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012773

Ohouo, P. Y., Bastos de Oliveira, F. M., Liu, Y., Ma, C. J., and Smolka, M. B. (2013). DNA-repair scaffolds dampen checkpoint signalling by counteracting the adaptor Rad9. Nature 493, 120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature11658

Paciotti, V., Clerici, M., Lucchini, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2000). The checkpoint protein Ddc2, functionally related to S. pombe Rad26, interacts with Mec1 and is regulated by Mec1-dependent phosphorylation in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 14, 2046–2059. doi: 10.1101/gad.14.16.2046

Pagès, V., and Fuchs, R. P. (2003). Uncoupling of leading- and lagging-strand DNA replication during lesion bypass in vivo. Science 300, 1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1083964

Pasero, P., and Vindigni, A. (2017). Nucleases acting at stalled forks: how to reboot the replication program with a few shortcuts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 51, 477–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120116-024745

Paull, T. T., and Gellert, M. (1998). The 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Mre11 facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol. Cell 1, 969–979. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80097-0

Paull, T. T., and Gellert, M. (1999). Nbs1 potentiates ATP-driven DNA unwinding and endonuclease cleavage by the Mre11/Rad50 complex. Genes Dev. 13, 1276–1288.

Pfander, B., and Diffley, J. F. (2011). Dpb11 coordinates Mec1 kinase activation with cell cycle-regulated Rad9 recruitment. EMBO J. 30, 4897–4907. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.345

Postow, L., Ullsperger, C., Keller, R. W., Bustamante, C., Vologodskii, A. V., and Cozzarelli, N. R. (2001). Positive torsional strain causes the formation of a four-way junction at replication forks. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2790–2796.

Puddu, F., Oelschlaegel, T., Guerini, I., Geisler, N. J., Niu, H., Herzog, M., et al. (2015). Synthetic viability genomic screening defines Sae2 function in DNA repair. EMBO J. 34, 1509–1522. doi: 10.15252/embj.201590973

Ray Chaudhuri, A., Hashimoto, Y., Herrador, R., Neelsen, K. J., Fachinetti, D., Bermejo, R., et al. (2012). Topoisomerase I poisoning results in PARP-mediated replication fork reversal. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 417–423. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2258

Reginato, G., Cannavo, E., and Cejka, P. (2017). Physiological protein blocks direct the Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 and Sae2 nuclease complex to initiate DNA end resection. Genes Dev. 31, 2325–2330. doi: 10.1101/gad.308254.117

Roberts, S. A., Sterling, J., Thompson, C., Harris, S., Mav, D., Shah, R., et al. (2012). Clustered mutations in yeast and in human cancers can arise from damaged long single-strand DNA regions. Mol. Cell 46, 424–435. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.030

Sakofsky, C. J., Roberts, S. A., Malc, E., Mieczkowski, P. A., Resnick, M. A., Gordenin, D. A., et al. (2014). Break-induced replication is a source of mutation clusters underlying kataegis. Cell Rep. 7, 1640–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.053

Schlacher, K., Christ, N., Siaud, N., Egashira, A., Wu, H., and Jasin, M. (2011). Double-strand break repair-independent role for BRCA2 in blocking stalled replication fork degradation by MRE11. Cell 145, 529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.041

Schlacher, K., Wu, H., and Jasin, M. (2012). A distinct replication fork protection pathway connects Fanconi anemia tumor suppressors to RAD51-BRCA1/2. Cancer Cell 22, 106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.015

Segurado, M., and Diffley, J. F. (2008). Separate roles for the DNA damage checkpoint protein kinases in stabilizing DNA replication forks. Genes Dev. 22, 1816–1827. doi: 10.1101/gad.477208

Shibata, A., Moiani, D., Arvai, A. S., Perry, J., Harding, S. M., Genois, M. M., et al. (2014). DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice is directed by distinct MRE11 nuclease activities. Mol. Cell 53, 7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.11.003

Shim, E. Y., Chung, W. H., Nicolette, M. L., Zhang, Y., Davis, M., and Zhu, Z. (2010). Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Ku proteins regulate association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks. EMBO J. 29, 3370–3380. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.219

Shiotani, B., and Zou, L. (2009). Single-stranded DNA orchestrates an ATM-to-ATR switch at DNA breaks. Mol. Cell 33, 547–558. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.024

Shroff, R., Arbel-Eden, A., Pilch, D., Ira, G., Bonner, W. M., Petrini, J. H., et al. (2004). Distribution and dynamics of chromatin modification induced by a defined DNA double-strand break. Curr. Biol. 14, 1703–1711. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.047

Smolka, M. B., Albuquerque, C. P., Chen, S. H., and Zhou, H. (2007). Proteome-wide identification of in vivo targets of DNA damage checkpoint kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10364–10369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701622104

Sogo, J. M., Lopes, M., and Foiani, M. (2002). Fork reversal and ssDNA accumulation at stalled replication forks owing to checkpoint defects. Science 297, 599–602. doi: 10.1126/science.1074023

Su, F., Mukherjee, S., Yang, Y., Mori, E., Bhattacharya, S., Kobayashi, J., et al. (2014). Non-enzymatic role for WRN in preserving nascent DNA strands after replication stress. Cell Rep. 9, 1387–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.025

Sweeney, F. D., Yang, F., Chi, A., Shabanowitz, J., Hunt, D. F., and Durocher, D. (2005). Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad9 acts as a Mec1 adaptor to allow Rad53 activation. Curr. Biol. 15, 1364–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.063

Symington, L. S. (2016). Mechanism and regulation of DNA end resection in eukaryotes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 51, 195–212. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2016.1172552

Taglialatela, A., Alvarez, S., Leuzzi, G., Sannino, V., Ranjha, L., Huang, J. W., et al. (2017). Restoration of replication fork stability in BRCA1- and BRCA2-deficient cells by inactivation of SNF2-family fork remodelers. Mol. Cell 68, 414–430. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.036

Teixeira-Silva, A., Ait Saada, A., Hardy, J., Iraqui, I., Nocente, M. C., Fréon, K., et al. (2017). The end-joining factor Ku acts in the end-resection of double strand break-free arrested replication forks. Nat. Commun. 8:1982. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02144-5

Tercero, J. A., and Diffley, J. F. (2001). Regulation of DNA replication fork progression through damaged DNA by the Mec1/Rad53 checkpoint. Nature 412, 553–557. doi: 10.1038/35087607

Thangavel, S., Berti, M., Levikova, M., Pinto, C., Gomathinayagam, S., Vujanovic, M., et al. (2015). DNA2 drives processing and restart of reversed replication forks in human cells. J. Cell. Biol. 208, 545–562. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201406100

Toh, G. W., O’Shaughnessy, A. M., Jimeno, S., Dobbie, I. M., Grenon, M., Maffini, S., et al. (2006). Histone H2A phosphorylation and H3 methylation are required for a novel Rad9 DSB repair function following checkpoint activation. DNA Repair. 5, 693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.03.005

Tran, P. T., Erdeniz, N., Dudley, S., and Liskay, R. M. (2002). Characterization of nuclease-dependent functions of Exo1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair. 1, 895–912. doi: 10.1016/S1568-7864(02)00114-3

Trujillo, K. M., Yuan, S. S., Lee, E. Y., and Sung, P. (1998). Nuclease activities in a complex of human recombination and DNA repair factors Rad50, Mre11, and p95. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21447–21450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21447

Tsang, E., Miyabe, I., Iraqui, I., Zheng, J., Lambert, S. A., and Carr, A. M. (2014). The extent of error-prone replication restart by homologous recombination is controlled by Exo1 and checkpoint proteins. J. Cell. Sci. 127, 2983–2994. doi: 10.1242/jcs.152678

Usui, T., Ogawa, H., and Petrini, J. H. J. (2001). A DNA damage response pathway controlled by Tel1 and the Mre11 complex. Mol. Cell 7, 1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00270-2

Usui, T., Ohta, T., Oshiumi, H., Tomizawa, J., Ogawa, H., and Ogawa, T. (1998). Complex formation and functional versatility of Mre11 of budding yeast in recombination. Cell 95, 705–716.

Villa, M., Bonetti, D., Carraro, M., and Longhese, M. P. (2018). Rad9/53BP1 protects stalled replication forks from degradation in Mec1/ATR-defective cells. EMBO Rep. 19, 351–367. doi: 10.15252/embr.201744910

Villa, M., Cassani, C., Gobbini, E., Bonetti, D., and Longhese, M. P. (2016). Coupling end resection with the checkpoint response at DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 3655–3663. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2262-6

Wang, W., Daley, J. M., Kwon, Y., Krasner, D. S., and Sung, P. (2017). Plasticity of the Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2-Sae2 nuclease ensemble in the processing of DNA-bound obstacles. Genes Dev. 31, 2331–2336. doi: 10.1101/gad.307900.117

Williams, G. J., Williams, R. S., Williams, J. S., Moncalian, G., Arvai, A. S., Limbo, O., et al. (2011). ABC ATPase signature helices in Rad50 link nucleotide state to Mre11 interface for DNA repair. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 423–431. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2038

Williams, R. S., Moncalian, G., Williams, J. S., Yamada, Y., Limbo, O., Shin, D. S., et al. (2008). Mre11 dimers coordinate DNA end bridging and nuclease processing in double-strand-break repair. Cell 135, 97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.017

Wiltzius, J. J., Hohl, M., Fleming, J. C., and Petrini, J. H. (2005). The Rad50 hook domain is a critical determinant of Mre11 complex functions. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 403–407. doi: 10.1038/nsmb928

Wu, D., Topper, L. M., and Wilson, T. E. (2008). Recruitment and dissociation of nonhomologous end joining proteins at a DNA double-strand break in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 178, 1237–1249. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083535

Wysocki, R., Javaheri, A., Allard, S., Sha, F., Coté, J., and Kron, S. J. (2005). Role of Dot1-dependent histone H3 methylation in G1 and S phase DNA damage checkpoint functions of Rad9. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 8430–8443. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8430-8443.2005

Yeo, J. E., Lee, E. H., Hendrickson, E. A., and Sobeck, A. (2014). CtIP mediates replication fork recovery in a FANCD2-regulated manner. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 3695–3705. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu078

Ying, S., Hamdy, F. C., and Helleday, T. (2012). Mre11-dependent degradation of stalled DNA replication forks is prevented by BRCA2 and PARP1. Cancer Res. 72, 2814–2821. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3417

You, Z., Chahwan, C., Bailis, J., Hunter, T., and Russell, P. (2005). ATM activation and its recruitment to damaged DNA require binding to the C terminus of Nbs1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 5363–5379. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5363-5379.2005

Zhang, Y., Hefferin, M. L., Chen, L., Shim, E. Y., Tseng, H. M., and Kwon, Y. (2007). Role of Dnl4-Lif1 in nonhomologous end-joining repair complex assembly and suppression of homologous recombination. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 639–646. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1261

Zhu, Z., Chung, W. H., Shim, E. Y., Lee, S. E., and Ira, G. (2008). Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell 134, 981–994. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037

Zierhut, C., and Diffley, J. F. (2008). Break dosage, cell cycle stage and DNA replication influence DNA double strand break response. EMBO J. 27,1875–1885. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.111

Keywords: checkpoint, DNA replication, double-strand break, MRX, nucleases, resection

Citation: Bonetti D, Colombo CV, Clerici M and Longhese MP (2018) Processing of DNA Ends in the Maintenance of Genome Stability. Front. Genet. 9:390. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00390

Received: 29 June 2018; Accepted: 29 August 2018;

Published: 12 September 2018.

Edited by:

Maria Grazia Giansanti, Istituto di Biologia e Patologia Molecolari (IBPM), Consiglio Nazionale Delle Ricerche (CNR), ItalyReviewed by:

Simonetta Piatti, Délégation Languedoc Roussillon (CNRS), FranceMarcus Smolka, Cornell University, United States

Copyright © 2018 Bonetti, Colombo, Clerici and Longhese. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Pia Longhese, bWFyaWFwaWEubG9uZ2hlc2VAdW5pbWliLml0

Diego Bonetti

Diego Bonetti Chiara Vittoria Colombo

Chiara Vittoria Colombo Michela Clerici

Michela Clerici Maria Pia Longhese

Maria Pia Longhese