95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Genet. , 14 June 2018

Sec. Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2018.00218

Min Wen1,2,3

Min Wen1,2,3 Bo Zhou2

Bo Zhou2 Xin Lin2

Xin Lin2 Yunhua Chen2

Yunhua Chen2 Jialei Song1,3

Jialei Song1,3 Yanmei Li1,3

Yanmei Li1,3 Eldad Zacksenhaus4

Eldad Zacksenhaus4 Yaacov Ben-David1,3*

Yaacov Ben-David1,3* Xiaojiang Hao1,3*

Xiaojiang Hao1,3*Objectives: The aim of the present study was to define the potential relationship of xeroderma pigmentosum group D (XPD) Lys751Gln polymorphisms and the risk of leukemia.

Methods: Comprehensive electronic search in Pubmed, Web of Science, EBSCO, the Cochrane Library and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) to find original articles about the association between XPD Lys751Gln polymorphisms and leukemia risk published before March 2017. Literature quality assessment was performed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed by I2 statistics. Random- or fixed-effects models was used to calculate pooled odds ratios (ORs) in the presence or absence of heterogeneity, respectively. Sensitivity analysis was used to assess the influence of individual studies on the pooled estimate. Publication bias was investigated using funnel plots and Egger’s regression test. All data analyses were performed using Stata 14.0 and Revman 5.3.

Results: Fourteen studies with a total of 7525 participants (2,757 patients; 4,768 controls) were included in this meta-analysis. We found that XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism significantly increased the risk of developing leukemia in both a dominant [Odds Ratio (OR)] = 1.21, 95%CI [1.10–1.35], P < 0.001) and heterozygote (OR = 1.22, 95%CI [1.09–1.36], P < 0.001) models. An allele model showed borderline significant increase in leukemia risk (OR = 1.13, 95%CI [1.00–1.27], P = 0.05). Subgroup analysis revealed a consistent association for some genetic models in Caucasian populations, adult or chronic groups, and in almost all models of childhood or acute groups.

Conclusion: Our results overall indicate that XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism increases the risk of leukemia, especially in childhood and acute cases.

Leukemia, a common malignant disease of the hematopoietic system (Jiang et al., 2014), can be classified on the basis of speed of disease progression and cell cytogenetics into four common subtypes: acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) (Arber et al., 2016). The etiological and mechanism of leukemogenesis are still unclear, though radiation, smoking, obesity and exposure to chemical carcinogens are considered high risk factors (Larsson and Wolk, 2008; Fircanis et al., 2014; Malagoli et al., 2016; Nikkila et al., 2016). Nevertheless, only a small proportion of people exposed to these risk factors develop leukemia, suggesting that hereditary factors may play critical role in leukemia carcinogenesis (Li et al., 2016; Huang and Ovcharenko, 2017).

Decreased efficiency of DNA repair is considered a crucial event in carcinogenesis (Hoeijmakers, 2001). Recently, a series of studies revealed that reduced DNA repair, leading to chromosomal aberrations and genomic instability, is a major contributor to the pathogenesis of leukemia (Das-Gupta et al., 2000; Esposito and So, 2014). Xeroderma pigmentosum group D (XPD) gene, also known as ERCC2, encodes a 5′–3′ superfamily 2 (SF2) helicase that plays a key role in unwinding the DNA double helix around damaged DNA during nucleotide excision repair (NER) (Kuper et al., 2012; Constantinescu-Aruxandei et al., 2016). Because of the biological significance of XPD, the XPD polymorphism has been extensively studied in different malignant diseases, such as pancreatic (Wu et al., 2017), colorectal (Ni et al., 2014) and gallbladder (Srivastava et al., 2010) cancers.

Several studies revealed inconsistent results on the relationship between the XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism (SNP IDs: rs13181) and leukemia susceptibility. Some studies showed a clear trend of XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism with increased risk of leukemia (Juan et al., 2005; Ganster et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2011; Banescu et al., 2014, 2016), while others displayed decreased risk of leukemia (Ozcan et al., 2011; Douzi et al., 2015), and yet others suggested no association between this polymorphism and leukemia (Seedhouse et al., 2002; Allan et al., 2004; Matullo et al., 2006; Mehta et al., 2006; Pakakasama et al., 2007; Batar et al., 2009; Canalle et al., 2011; Ozdemir et al., 2012; Sorour et al., 2013; Dincer et al., 2015). To evaluate more precisely the potential relationship between XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism and leukemia, we hereby report on a meta-analysis using all available published data.

A computerized search of Pubmed, Web of Science, EBSCO, the Cochrane Library and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) up to March 2017 was conducted using the following search strategy: (“XPD” or “ERCC2” or “XPD”), and (“polymorphism” or “variant” or “mutation”), and “Leukemia.” The search was restricted to English and Chinese written publications. A manual search of references of the retrieved articles and relevant reviews was also conducted. A flowchart of information pertaining to identification, screening, eligibility, and final datasets selected was constructed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009).

In this report, the studies that investigate the association between XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism and leukemia risk were included. The inclusion criteria were (1) case-control study design; (2) available genotype information of the XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism; (3) evaluation of the XPD gene polymorphism and the risk of leukemia; and (4) the distribution of genotypes among the controls agreeing with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Major criteria for exclusion were: (1) duplication of earlier publications (for studies using the same sample in different publications, only the most complete information was included following careful examination), (2) unpublished papers, dissertations, conference articles and reviews, (3) family based studies of pedigrees.

Data from each eligible study were extracted into Excel including country of origin, ethnicity of each study population, age group (adult or childhood), subtypes of leukemia, genotyping method, numbers of cases and controls, numbers of cases and controls in the XPD Lys751Gln genotypes and results of the HWE test.

The quality of the included studies was assessed by two reviewers according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (Stang, 2010), which is used to assess the quality of observational studies. Discrepancies were reported and settled by a third party. Three major aspects of study quality were scored: (1) selection of the study groups (0 ± 4 points); (2) determination of the exposure of interest in the studies (0 ± 3 points); and (3) the quality of the adjustment for confounding variables (0 ± 2 points). A study could be scored as a maximum of one star for each item numbered within the categories of Selection and Exposure, while at most two stars could be allocated to Comparability. A higher score represents improved greater quality of the study methodology. A score equal to or higher than 6 was considered to indicate high study quality.

The combined odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to evaluate the strength of the association with the risk of leukemia. Pooled ORs were performed for allelic comparison (a vs. A), dominant (aa + Aa vs. AA), recessive (aa vs. Aa + AA) and codominant (aa vs. AA and Aa vs. AA) models (‘a’ and ‘A’ represent the mutant allele and the wild-type allele, respectively). Heterogeneity among the included studies was assessed by I2 statistic. A random-effects model or fixed-effects model was used to calculate pooled odds ratio (OR) in the presence or absence of heterogeneity, respectively. To detect possible sources of heterogeneity and potential difference among subgroups, meta-regression and subgroup analyses were carried out on stratification of different ethnicity, age group and subtypes of leukemia. The significance of the pooled OR was determined by Z-test, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Publication bias was investigated using funnel plots and Egger’s regression test. We also conducted sensitivity analysis to test the robustness of associations by sequentially omitting each of the included studies one at a time. All the data analysis was performed using the software STATA 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States) and Review Manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom).

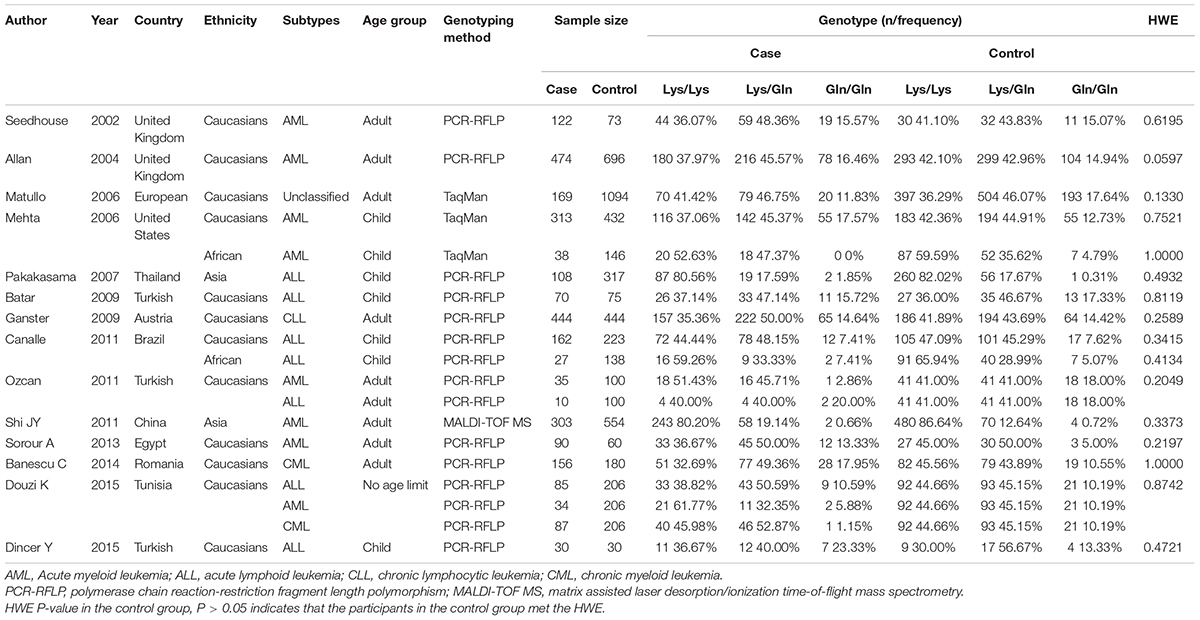

We used several search criteria to include or exclude reported studies on the relationship between XPD polymorphism and leukemia (Figure 1). A total of 14 studies (2,757 cases and 4,768 controls) about XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism were included in the final evaluation (Table 1). Quality assessment of the individual studies showed that the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) score ranged from 6 to 8, indicating that the quality of methodology was generally good (Table 2).

TABLE 1. Main characteristics of datasets included for the XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism and leukemia risk.

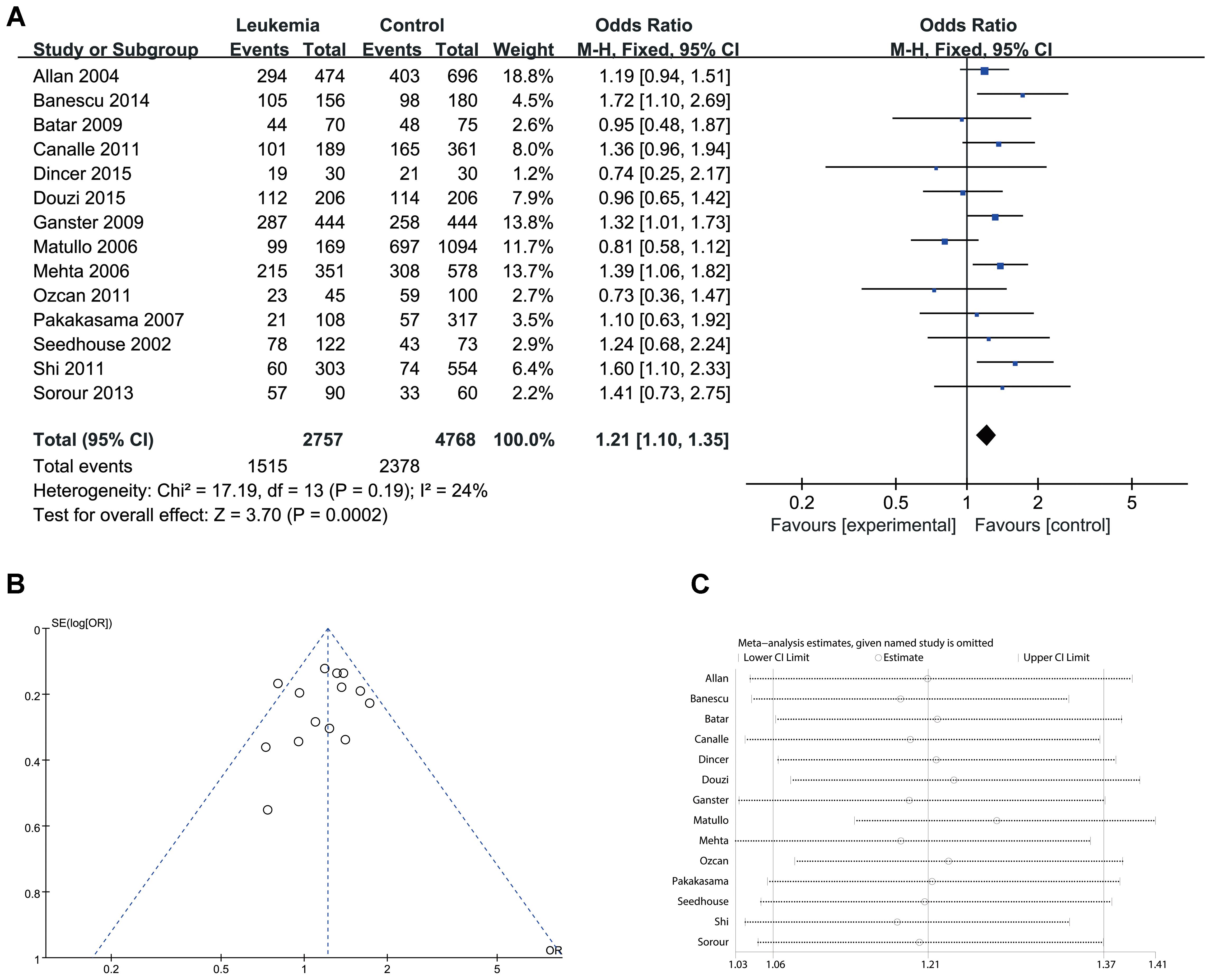

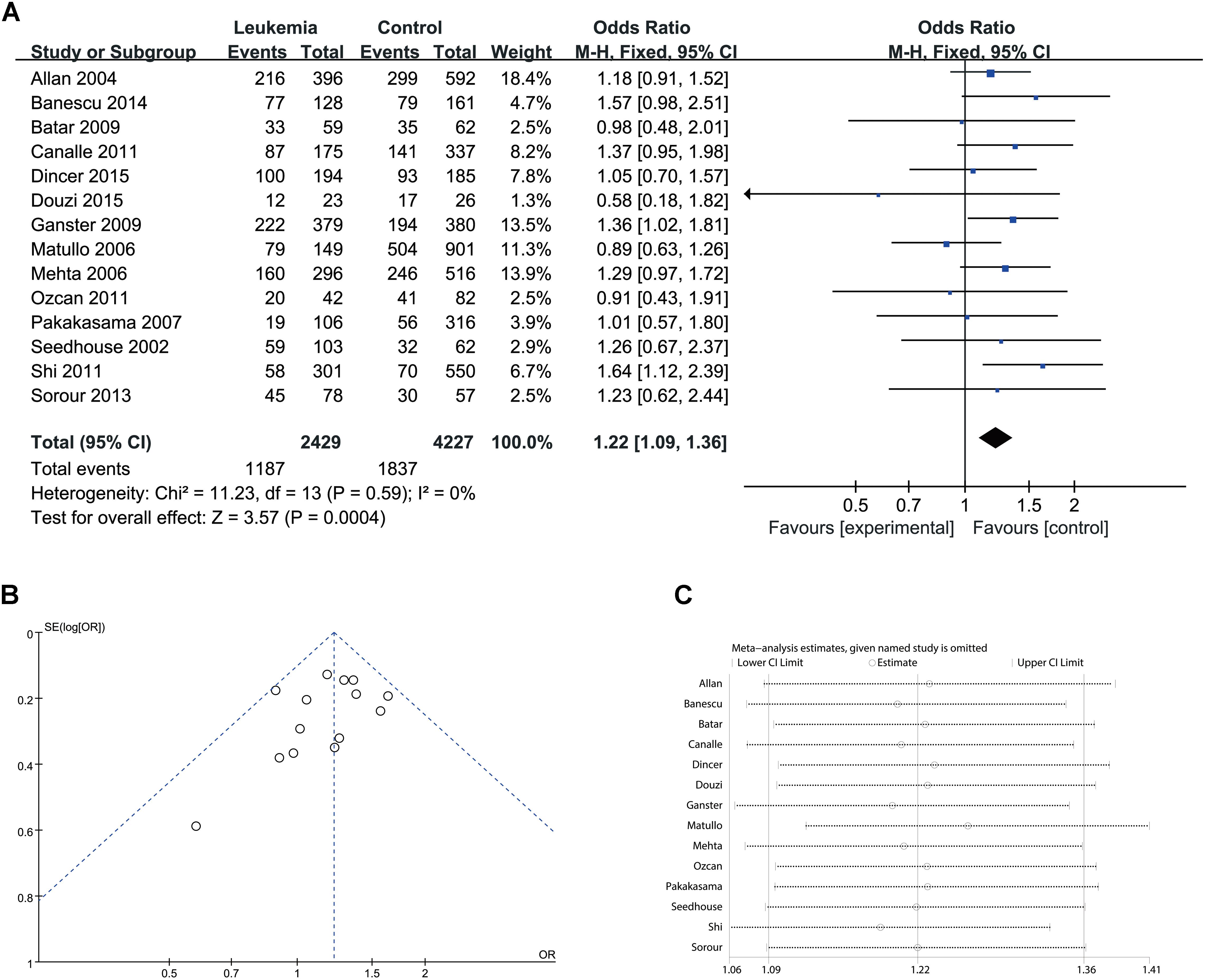

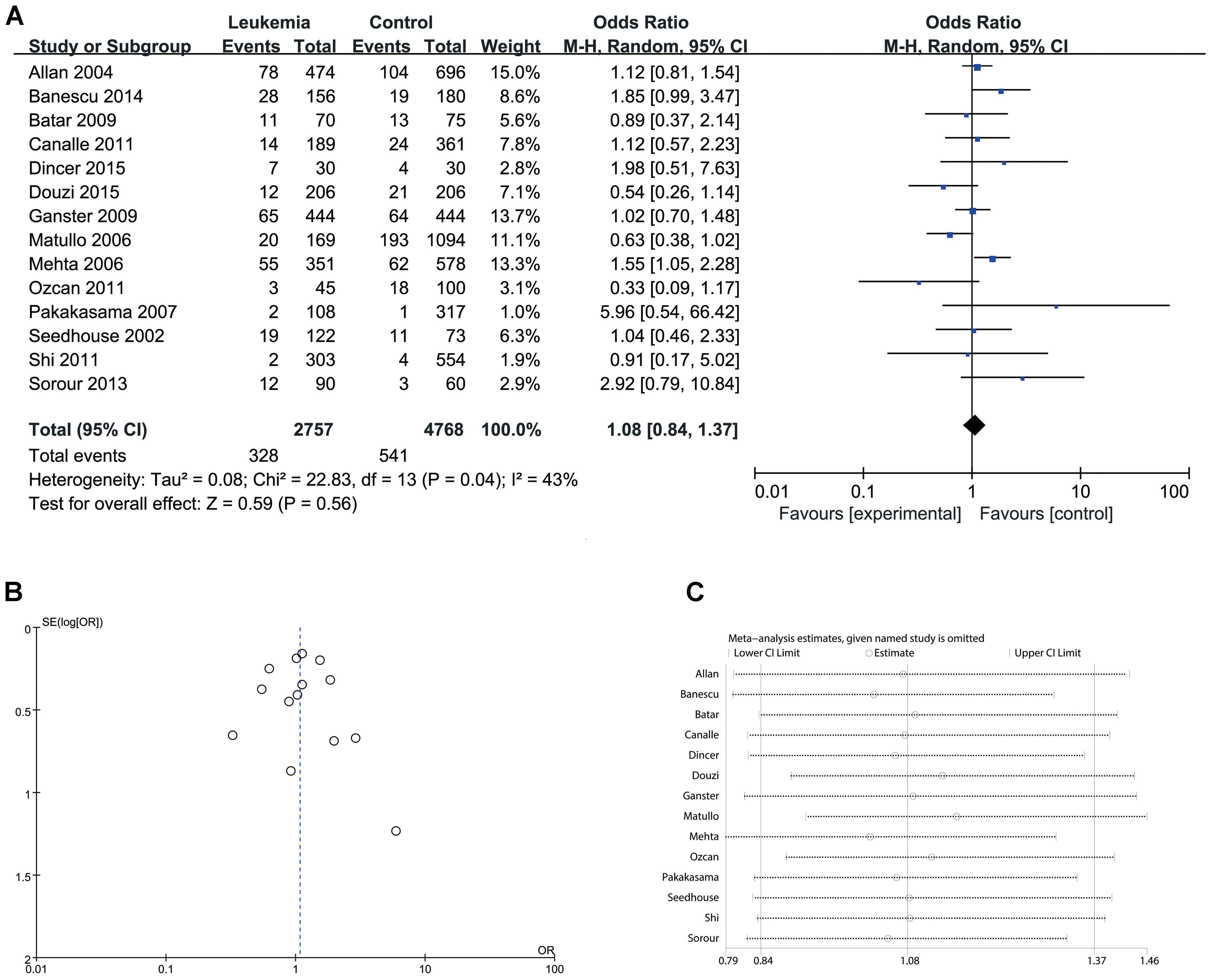

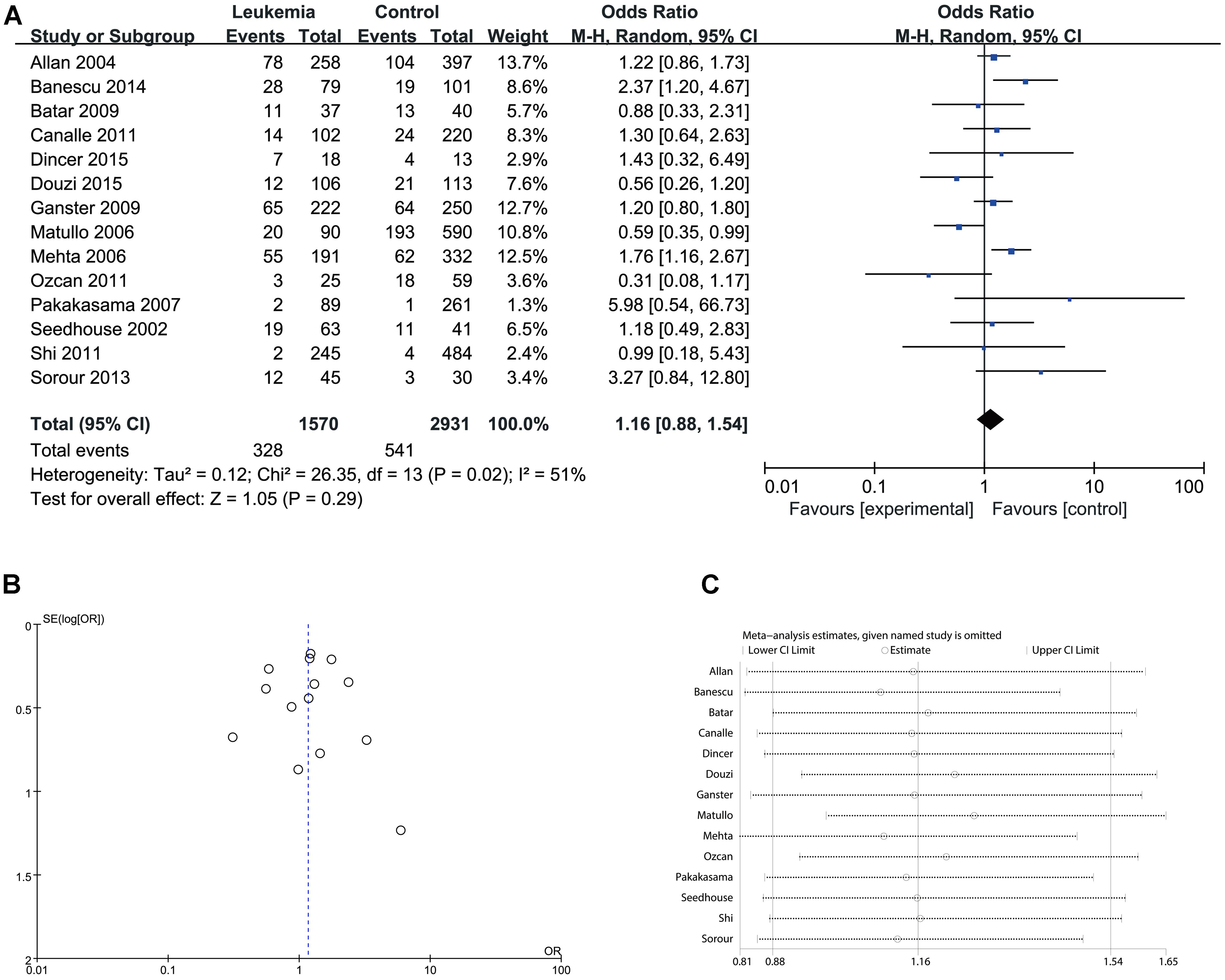

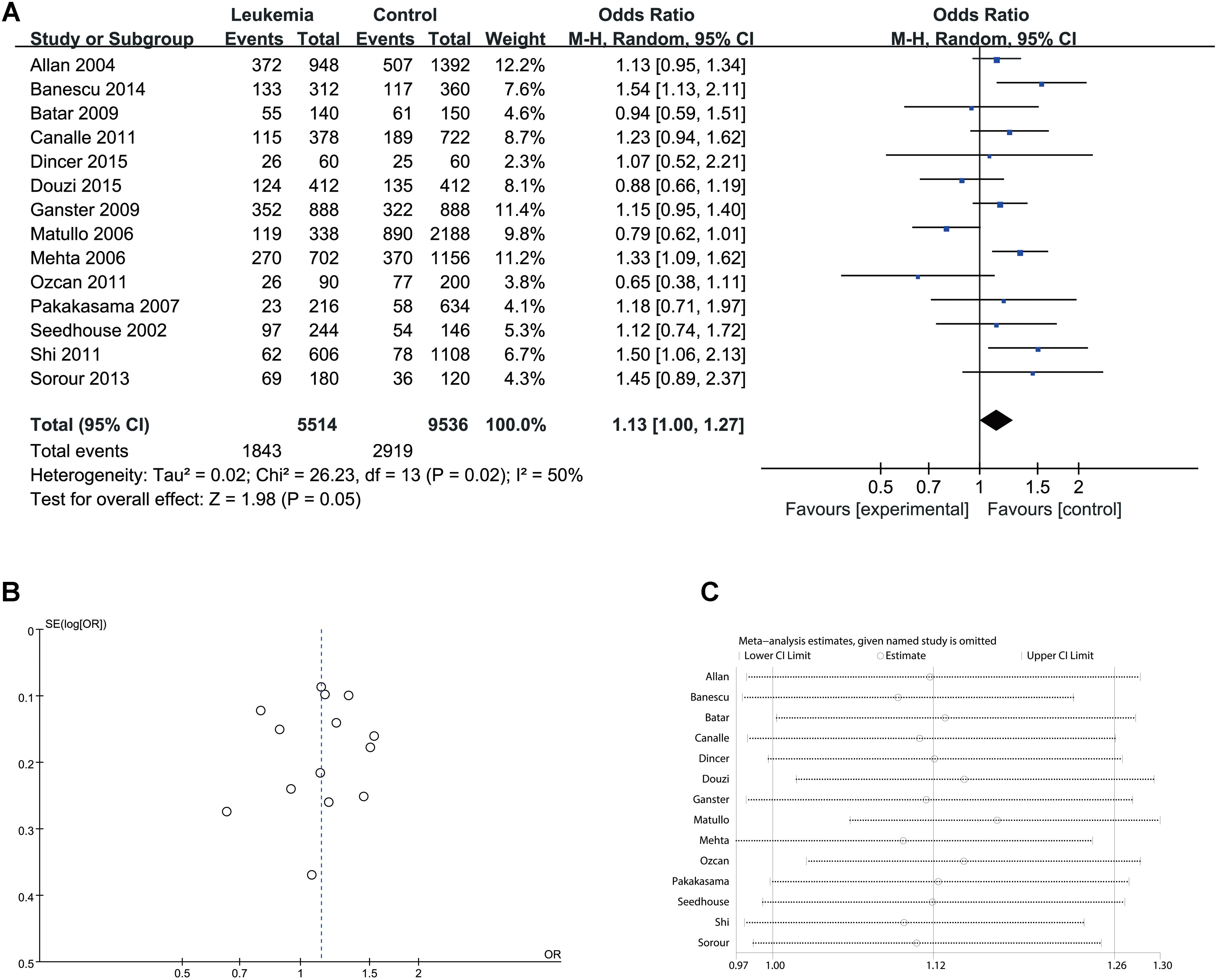

Since significant heterogeneity was identified in recessive, homozygote and alleles models, random-effects model was used. The other genetic models were analysis by fixed-effects model. Overall, significant increase in leukemia risk was identified in dominant (Gln/Gln + Lys/Gln vs. Lys/Lys: I2 = 24%, P < 0.001, Figure 2) and heterozygote models (Lys/Gln vs. Lys/Lys: I2 = 0%, P < 0.001, Figure 3). No significant association was found in recessive (Gln/Gln vs. Lys/Gln + Lys/Lys: I2 = 43%, P = 0.560, Figure 4) and homozygote (Gln/Gln vs. Lys/Lys: I2 = 51%, P = 0.29, Figure 5) models. In addition, allele model showed a borderline significant increase in leukemia risk (Gln vs. Lys: I2 = 50%, P = 0.05, Figure 6). Moderate heterogeneity (I2: 43–51%) was found in the no-association model group. To explore the source of this heterogeneity, a meta-regression analysis was conducted. The results revealed that the heterogeneity was not associated with ethnicity, age, clinical subtype or detection method (p > 0.05 in all genetic models). We further explored the source of heterogeneity by removing one study each time. The results showed that the Matullo’s study was one of the central sources of heterogeneity (its inclusion increased heterogeneity by 12–24%). No publication bias was found in any of the models. Sensitivity analysis suggested that with exception of the allele model, the results were stable and reliable.

FIGURE 2. Comparison of XPD Lys751Gln for overall data in dominant model (Gln/Gln + Lys/Gln vs. Lys/Lys). (A) Forest plot, (B) funnel plot, (C) sensitivity analysis.

FIGURE 3. Comparison of XPD Lys751Gln for overall data in heterozygote model (Lys/Gln vs. Lys/Lys). (A) Forest plot, (B) funnel plot, (C) sensitivity analysis.

FIGURE 4. Comparison of XPD Lys751Gln for overall data in recessive model (Gln/Gln vs. Lys/Gln + Lys/Lys). (A) Forest plot, (B) funnel plot, (C) sensitivity analysis.

FIGURE 5. Comparison of XPD Lys751Gln for overall data in homozygote model (Gln/Gln vs. Lys/Lys). (A) Forest plot, (B) funnel plot, (C) sensitivity analysis.

FIGURE 6. Comparison of XPD Lys751Gln for overall data in allele model (Gln vs. Lys). (A) Forest plot, (B) funnel plot, (C) sensitivity analysis.

In Caucasian populations, a significant increase in leukemia risk was found in heterozygote model (Lys/Gln vs. Lys/Lys: I2 = 0%, P = 0.02) and dominant models (Gln/Gln + Lys/Gln vs. Lys/Lys: I2 = 14%, P = 0.02). No significant association was found in recessive (Gln/Gln vs. Lys/Gln + Lys/Lys: I2 = 44%, P = 0.75), homozygote (Gln/Gln vs. Lys/Lys: I2 = 55%, P = 0.32) and allele models (Gln vs. Lys: I2 = 47%, P = 0.24) (Table 3). In African and Asian populations, subgroup analysis was unreliable as only two studies were available.

In subgroup analysis by age group, one study was excluded as it lacked data on patients’ age (Douzi et al., 2015). Significant assoc). Significant associations were consistently found in some genetic models of adult group (GlnGln + LysGln vs. LysLys: I2 = 46.0%, P = 0.04; LysGln vs. LysLys: I2 = 9%, P = 0.002), and in almost all models of childhood group (Gln vs. Lys: I2 = 0%, P = 0.003; GlnGln + LysGln vs. LysLys: I2 = 0%, P = 0.01; GlnGln vs. LysGln + LysLys: I2 = 0%, P = 0.03; GlnGln vs. LysLys: I2 = 0%, P = 0.009; LysGln vs. LysLys: I2 = 0%, P = 0.04). Moderate to higher heterogeneity (I2: 46–65%) was found in the no-association models of the adult group (Table 4).

In subgroup analysis by leukemia subtypes, one study was excluded as it lacked such data (Matullo et al., 2006). Significant associations were found in almost all genetic models of acute leukemia (Gln vs. Lys: I2 = 12%, P < 0.001; GlnGln + LysGln vs. LysLys: I2 = 0%, P < 0.001; GlnGln vs. LysLys: I2 = 14%, P = 0.02; LysGln vs. LysLys: I2 = 0%, P = 0.003), and in some models of chronic disease (GlnGln + LysGln vs. LysLys: I2 = 34%, P = 0.009; LysGln vs. LysLys: I2 = 0%, P < 0.001) (Table 5).

The NER pathway is a highly conserved DNA repair mechanism that removes bulky intra-strand adducts created by agents such as UV radiation and certain chemicals, including several commonly used chemotherapy agents (Scharer, 2013). Genetic polymorphism in DNA repair genes may cause variation in DNA repair capacity, which in turn can lead to cumulative genotoxic damage and increased susceptibility to cancer (Douzi et al., 2015). As an important component of NER, XPD is an evolutionarily conserved ATP-dependent DNA helicase that plays an essential role in DNA repair (Kim et al., 2016). Several studies suggested an increased risk of cancer in individuals with polymorphism in XPD or other NER pathway genes (Paszkowska-Szczur et al., 2013; He et al., 2016). Moreover, several molecular epidemiological studies have found an association between XPD polymorphism and leukemia risk in diverse populations. However, the results were inconsistent and even contradictory. We therefore conducted a meta-analysis to globally evaluate the potential relationship between XPD polymorphism and leukemia.

Our results indicate that XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism significantly increase overall leukemia risk in dominant and heterozygote models, but not in allele model or homozygote model. The results suggest that heterozygous mutations but not homozygote mutations of XPD (Lys/Gln) may increase the genetic susceptibility of leukemia. This may be the result of a higher rates of heterozygous vs. homozygous mutations (the ratio between heterozygous and homozygous mutations is 2.27 ∼ 56 in control and 1.71 ∼ 29 in leukemia). Subgroup analysis by ethnicity showed the same result in Caucasian population. The exact mechanism for association between different tumors susceptibility and XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism is currently unknown. XPD is a 5′–3′ superfamily 2 DNA helicase that opens damaged DNA for bulky lesion repair in NER. The interaction of C-terminal domain of XPD with the p44 helicase activator protein are critical for both helicase activity and stability of the TFIIH complex, which is essential for RNA polymerase (RNAP) II-mediated transcription initiation and the NER (Liu et al., 2008). The XPD C-terminal Lys751Gln polymorphism may alter the structure of the C-terminal domain, hence blocking critical interaction with p44 and destructive TFIIH conformation, which subsequently reduce DNA repair activity (Lunn et al., 2000; Fan et al., 2008; Monaco et al., 2009). Furthermore, by stratifying the data by age and subtype of disease, we found that XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism significantly increased leukemia risk in almost all models of childhood and acute disease. The occurrence and development of leukemia appeared to be regulated by genetic and environmental factors. In children with acute leukemia, malignancy manifests with a short latency period, thus does not have enough exposure time to allow the initiation of a long carcinogenic process. Unlike children, adults usually develop cancer because of the cumulative effect of environmental exposure during his/her life (Brisson et al., 2015). Thus, we speculate that genetic polymorphism is more important for childhood and acute leukemia.

Compared to previous reports (Liu et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2014), the present study has the following advantages: (1) it analyzed the association between XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism and acute leukemia, but also it association with chronic leukemia; (2) A total of 14 studies (2,757 cases and 4,768 controls) were compiled in our research, thus increasing the statistical power of the analysis. (3) Strict literature inclusion and exclusion criteria were enforced, the Ozdemir’s study was excluded from our analysis due to lack of discerning information between ALL and Burkitt lymphoma patients. However, our research also has some limitations: (1) The number of original studies included in the meta-analysis are relatively small, especially in the subgroup analysis. Future studies on ethnicity, age and subtype of leukemia are needed to further corroborate our findings. (2) Heterogeneity, which can greatly affect conclusions of meta-analysis, was high in some models. Our result showed that moderate or higher heterogeneity was found in some models, which showed no association with leukemia risk. The Matullo’s study was a major source of this heterogeneity, probably due to the significant differences in number of cases and controls.

Our meta-analysis demonstrates that XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism significantly increases overall leukemia risk in dominant and heterozygote models, and that this polymorphism is significant associated with almost all genetic models of childhood and acute leukemia.

XH and Y-BD designed this study. XL, YC, and JS searched databases and collected the full-text papers. MW and BZ extracted and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. EZ, YL, XH, and Y-BD reviewed the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81700169), the Natural Science Foundation of Guizhou Province (201842920480710623), “Light of the West” Talent Cultivation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (201684), the Found for Guizhou The Fourth Batch of “100 Talented Leaders”, and the Science and Technology Department of Guizhou Province Innovation and Project Grant (2013-6012).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Allan, J. M., Smith, A. G., Wheatley, K., Hills, R. K., Travis, L. B., Hill, D. A., et al. (2004). Genetic variation in XPD predicts treatment outcome and risk of acute myeloid leukemia following chemotherapy. Blood 104, 3872–3877. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2161

Arber, D. A., Orazi, A., Hasserjian, R., Thiele, J., Borowitz, M. J., Le Beau, M. M., et al. (2016). The revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 127, 2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544

Banescu, C., Iancu, M., Trifa, A. P., Dobreanu, M., Moldovan, V. G., Duicu, C., et al. (2016). Influence of XPC, XPD, XPF, and XPG gene polymorphisms on the risk and the outcome of acute myeloid leukemia in a Romanian population. Tumour Biol. 37, 9357–9366. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4815-6

Banescu, C., Trifa, A. P., Demian, S., Benedek Lazar, E., Dima, D., Duicu, C., et al. (2014). Polymorphism of XRCC1, XRCC3, and XPD genes and risk of chronic myeloid leukemia. Biomed Res. Int. 2014:213790. doi: 10.1155/2014/213790

Batar, B., Guven, M., Baris, S., Celkan, T., and Yildiz, I. (2009). DNA repair gene XPD and XRCC1 polymorphisms and the risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 33, 759–763. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.11.005

Brisson, G. D., Alves, L. R., and Pombo-de-Oliveira, M. S. (2015). Genetic susceptibility in childhood acute leukaemias: a systematic review. Ecancermedicalscience 9:539. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2015.539

Canalle, R., Silveira, V. S., Scrideli, C. A., Queiroz, R. G., Lopes, L. F., and Tone, L. G. (2011). Impact of thymidylate synthase promoter and DNA repair gene polymorphisms on susceptibility to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 52, 1118–1126. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.559672

Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D., Petrovic-Stojanovska, B., Penedo, J. C., White, M. F., and Naismith, J. H. (2016). Mechanism of DNA loading by the DNA repair helicase XPD. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 2806–2815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw102

Das-Gupta, E. P., Seedhouse, C. H., and Russell, N. H. (2000). DNA repair mechanisms and acute myeloblastic leukemia. Hematol. Oncol. 18, 99–110. doi: 10.1002/1099-1069(200009)18:3<99::AID-HON662>3.0.CO;2-Z

Dincer, Y., Yuksel, S., Batar, B., Guven, M., Onaran, I., and Celkan, T. (2015). DNA repair gene polymorphisms and their relation with dna damage, dna repair, and total antioxidant capacity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 37, 344–350. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000133

Douzi, K., Ouerhani, S., Menif, S., Safra, I., and Abbes, S. (2015). Polymorphisms in XPC, XPD and XPG DNA repair genes and leukemia risk in a Tunisian population. Leuk. Lymphoma 56, 1856–1862. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.974045

Esposito, M. T., and So, C. W. (2014). DNA damage accumulation and repair defects in acute myeloid leukemia: implications for pathogenesis, disease progression, and chemotherapy resistance. Chromosoma 123, 545–561. doi: 10.1007/s00412-014-0482-9

Fan, L., Fuss, J. O., Cheng, Q. J., Arvai, A. S., Hammel, M., Roberts, V. A., et al. (2008). XPD helicase structures and activities: insights into the cancer and aging phenotypes from XPD mutations. Cell 133, 789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.030

Fircanis, S., Merriam, P., Khan, N., and Castillo, J. J. (2014). The relation between cigarette smoking and risk of acute myeloid leukemia: an updated meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Am. J. Hematol. 89, E125–E132. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23744

Ganster, C., Neesen, J., Zehetmayer, S., Jager, U., Esterbauer, H., Mannhalter, C., et al. (2009). DNA repair polymorphisms associated with cytogenetic subgroups in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 48, 760–767. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20680

He, B. S., Xu, T., Pan, Y. Q., Wang, H. J., Cho, W. C., Lin, K., et al. (2016). Nucleotide excision repair pathway gene polymorphisms are linked to breast cancer risk in a Chinese population. Oncotarget 7, 84872–84882. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12744

Hoeijmakers, J. H. (2001). Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature 411, 366–374. doi: 10.1038/35077232

Huang, D., and Ovcharenko, I. (2017). Epigenetic and genetic alterations and their influence on gene regulation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. BMC Genomics 18:236. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3617-6

Jiang, D., Hong, Q., Shen, Y., Xu, Y., Zhu, H., Li, Y., et al. (2014). The diagnostic value of DNA methylation in leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 9:e96822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096822

Juan, Z., Yuepu, P., Lihong, Y., Fangyan, Z., and Ji, G. (2005). Study on the relationship between genetic polymorphism and susceptibility for adult acute leukemi. Tumor 25, 346–350.

Kim, J., Mouw, K. W., Polak, P., Braunstein, L. Z., Kamburov, A., Tiao, G., et al. (2016). Somatic ERCC2 mutations are associated with a distinct genomic signature in urothelial tumors. Nat. Genet. 48, 600–606. doi: 10.1038/ng.3557

Kuper, J., Wolski, S. C., Michels, G., and Kisker, C. (2012). Functional and structural studies of the nucleotide excision repair helicase XPD suggest a polarity for DNA translocation. EMBO J. 31, 494–502. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.374

Larsson, S. C., and Wolk, A. (2008). Overweight and obesity and incidence of leukemia: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int. J. Cancer 122, 1418–1421. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23176

Li, S., Garrett-Bakelman, F. E., Chung, S. S., Sanders, M. A., Hricik, T., Rapaport, F., et al. (2016). Distinct evolution and dynamics of epigenetic and genetic heterogeneity in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Med. 22, 792–799. doi: 10.1038/nm.4125

Liu, D., Wu, D., Li, H., and Dong, M. (2014). The effect of XPD/ERCC2 Lys751Gln polymorphism on acute leukemia risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gene 538, 209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.01.049

Liu, H., Rudolf, J., Johnson, K. A., McMahon, S. A., Oke, M., Carter, L., et al. (2008). Structure of the DNA repair helicase XPD. Cell 133, 801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.029

Lunn, R. M., Helzlsouer, K. J., Parshad, R., Umbach, D. M., Harris, E. L., Sanford, K. K., et al. (2000). XPD polymorphisms: effects on DNA repair proficiency. Carcinogenesis 21, 551–555. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.551

Malagoli, C., Costanzini, S., Heck, J. E., Malavolti, M., De Girolamo, G., Oleari, P., et al. (2016). Passive exposure to agricultural pesticides and risk of childhood leukemia in an Italian community. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 219, 742–748. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.09.015

Matullo, G., Dunning, A. M., Guarrera, S., Baynes, C., Polidoro, S., Garte, S., et al. (2006). DNA repair polymorphisms and cancer risk in non-smokers in a cohort study. Carcinogenesis 27, 997–1007. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi280

Mehta, P. A., Alonzo, T. A., Gerbing, R. B., Elliott, J. S., Wilke, T. A, Kennedy, R. J., et al. (2006). XPD Lys751Gln polymorphism in the etiology and outcome of childhood acute myeloid leukemia: a Children’s Oncology Group report. Blood 107, 39–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2305

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62, 1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Monaco, R., Rosal, R., Dolan, M. A., Pincus, M. R., Freyer, G., and Brandt-Rauf, P. W. (2009). Conformational effects of a common codon 751 polymorphism on the C-terminal domain of the xeroderma pigmentosum D protein. J. Carcinog. 8:12. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.54918

Ni, M., Zhang, W. Z., Qiu, J. R., Liu, F., Li, M., Zhang, Y. J., et al. (2014). Association of ERCC1 and ERCC2 polymorphisms with colorectal cancer risk in a Chinese population. Sci. Rep. 4:4112. doi: 10.1038/srep04112

Nikkila, A., Erme, S., Arvela, H., Holmgren, O., Raitanen, J., Lohi, O., et al. (2016). Background radiation and childhood leukemia: a nationwide register-based case-control study. Int. J. Cancer 139, 1975–1982. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30264

Ozcan, A., Pehlivan, M., Tomatir, A. G., Karaca, E., Ozkinay, C., Ozdemir, F., et al. (2011). Polymorphisms of the DNA repair gene XPD (751) and XRCC1 (399) correlates with risk of hematological malignancies in Turkish population. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10, 8860–8870. doi: 10.5897/AJB10.1839

Ozdemir, N., Celkan, T., Baris, S., Batar, B., and Guven, M. (2012). DNA repair gene XPD and XRCC1 polymorphisms and the risk of febrile neutropenia and mucositis in children with leukemia and lymphoma. Leuk. Res. 36, 565–569. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.10.012

Pakakasama, S., Sirirat, T., Kanchanachumpol, S., Udomsubpayakul, U., Mahasirimongkol, S., Kitpoka, P., et al. (2007). Genetic polymorphisms and haplotypes of DNA repair genes in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 48, 16–20. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20742

Paszkowska-Szczur, K., Scott, R. J., Serrano-Fernandez, P., Mirecka, A., Gapska, P., Gorski, B., et al. (2013). Xeroderma pigmentosum genes and melanoma risk. Int. J. Cancer 133, 1094–1100. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28123

Scharer, O. D. (2013). Nucleotide excision repair in eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5:a012609. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012609

Seedhouse, C., Bainton, R., Lewis, M., Harding, A., Russell, N., and Das-Gupta, E. (2002). The genotype distribution of the XRCC1 gene indicates a role for base excision repair in the development of therapy-related acute myeloblastic leukemia. Blood 100, 3761–3766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1152

Shi, J. Y., Ren, Z. H., Jiao, B., Xiao, R., Yun, H. Y., Chen, B., et al. (2011). Genetic variations of DNA repair genes and their prognostic significance in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Int. J. Cancer 128, 233–238. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25318

Sorour, A., Ayad, M. W., and Kassem, H. (2013). The genotype distribution of the XRCC1, XRCC3, and XPD DNA repair genes and their role for the development of acute myeloblastic leukemia. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 17, 195–201. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0278

Srivastava, K., Srivastava, A., and Mittal, B. (2010). Polymorphisms in ERCC2, MSH2, and OGG1 DNA repair genes and gallbladder cancer risk in a population of Northern India. Cancer 116, 3160–3169. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25063

Stang, A. (2010). Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

Wu, K. G., He, X. F., Li, Y. H., Xie, W. B., and Huang X. (2014). Association between the XPD/ERCC2 Lys751Gln polymorphism and risk of cancer: evidence from 224 case-control studies. Tumour Biol. 35, 11243–11259. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2379-x

Keywords: leukemia, XPD, ERCC2, meta-analysis, polymorphism

Citation: Wen M, Zhou B, Lin X, Chen Y, Song J, Li Y, Zacksenhaus E, Ben-David Y and Hao X (2018) Associations Between XPD Lys751Gln Polymorphism and Leukemia: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Genet. 9:218. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00218

Received: 16 February 2018; Accepted: 28 May 2018;

Published: 14 June 2018.

Edited by:

Vita Dolzan, University of Ljubljana, SloveniaReviewed by:

Ken Batai, University of Arizona, United StatesCopyright © 2018 Wen, Zhou, Lin, Chen, Song, Li, Zacksenhaus, Ben-David and Hao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yaacov Ben-David, eWFhY292YmVuZGF2aWRAaG90bWFpbC5jb20= Xiaojiang Hao, aGFveGpAbWFpbC5raWIuYWMuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.