- Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Stadt Seeland, Germany

The recent advances in sequencing throughput and genome assembly algorithms have established whole-genome shotgun (WGS) assemblies as the cornerstone of the genomic infrastructure for many species. WGS assemblies can be constructed with comparative ease and give a comprehensive representation of the gene space even of large and complex genomes. One major obstacle in utilizing WGS assemblies for important research applications such as gene isolation or comparative genomics has been the lack of chromosomal positioning and contextualization of short sequence contigs. Assigning chromosomal locations to sequence contigs required the construction and integration of genome-wide physical maps and dense genetic linkage maps as well as synteny to model species. Recently, methods to rapidly construct ultra-dense linkage maps encompassing millions of genetic markers from WGS sequencing data of segregating populations have made possible the direct assignment of genetic positions to short sequence contigs. Here, we review recent developments in the integration of WGS assemblies and sequence-based linkage maps, discuss challenges for further improvement of the methodology and outline possible applications building on genetically anchored WGS assemblies.

Introduction

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has facilitated the rapid collection of vast amounts of genomic sequence data, enabling whole-genome shotgun (WGS) assemblies in species with huge genomes (Li et al., 2010; Jia et al., 2013; Ling et al., 2013; Nystedt et al., 2013). Compared with approaches based on physical maps, WGS assemblies are rapidly made, are comparatively cheap and represent an easy way to gain a comprehensive view of the gene complement of a species, even for species without prior availability of genomic resources. Nevertheless, de novo sequence assembly from short sequence reads remains a formidable algorithmic challenge requiring large amounts of sequence data and powerful compute resources. A recent comparative benchmarking (Bradnam et al., 2013) of assembly pipelines on real datasets highlighted substantial differences in the performance of different algorithmic approaches. The main limitation of WGS assemblies for downstream applications is their fragmentation (Green, 1997): they often consist of up to millions of short contiguous pieces of sequence (contigs), which may be grouped and partially ordered by long-distance mate-pair reads to form scaffolds.

The primary algorithmic challenge of sequence assembly – and thus the origin of the fragmentation – are repeat elements (Alkan et al., 2011b), whose numerous copies are nearly identical, are difficult to resolve with short NGS reads and thus tend to be assembled into a single collapsed sequence contig. Moreover, contigs representing single-copy regions cannot be unambiguously extended at the border of repetitive elements and terminate there. The lack of contiguity of WGS assemblies is a major impediment to downstream analyses. Sequence-based high-throughput genotyping and its applications such as genome-wide association or population genetic studies rely on the visualization of features [single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), peaks of summary statistics] along the chromosomes, often applying sliding-windows to aggregate the information of neighboring contigs (Luikart et al., 2003; Schneeberger et al., 2009; Andrews and Luikart, 2014; Ellegren, 2014). Without any notion of order or vicinity of contigs, such approaches are impossible.

The process of assigning chromosomal locations to contigs of an assembly is referred to as anchoring. The ultimate goal of this process is to establish pseudomolecules, single accurately ordered sequence scaffolds for each chromosome with as little intervening gaps as possible. Lacking in completeness – in particular in the repetitive portion of the genome – and contiguity, WGS assemblies of large and complex genomes of flowering plants or mammals have so far not attained the quality of a draft genome (Alkan et al., 2011b; Feuillet et al., 2011). High-quality reference sequences continue to be constructed with the help of physical maps and sequencing single bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs; Groenen et al., 2012; Amborella Genome Project, 2013). However, this hierarchical shotgun approach entails the laborious and expensive steps of BAC library construction, finger-printing and clone-by-clone sequencing (Ariyadasa and Stein, 2012).

If extensive physical mapping resources are not available (as is the case for many non-model species), reference genomes of related species may serve as proxy to order WGS assemblies, but approaches based on genome collinearity (Mayer et al., 2009) are restricted to genic regions and their accuracy is bounded by the degree of syntenic conservation between related species. Recent translocations or duplications of single genes or larger genomic regions may reduce interspecific collinearity and thus impact the accuracy of synteny-guided assembly ordering (Wicker et al., 2011). This approach is also limited to the gene-space, as intergenic, repetitive sequences evolve very fast and show little conservation even between individuals of a single species (Brunner et al., 2005). It is therefore desirable to have methods at hand that can provide fast and cost-efficient access to an at least partially ordered WGS assembly.

Genetic Anchoring of WGS Assemblies

For more than a century, genetic mapping has been a universal method to order genomic loci along the chromosomes of sexually reproducing species. Theoretical models of allelic segregation in experimental mapping populations have long been established (Morgan et al., 1922) and various algorithms applying these principles to construct genetic linkage maps from genotypic data have been implemented [reviewed in Cheema and Dicks (2009)]. During the last decades, advances in genetic mapping have been concomitant with the development of molecular marker technologies (Henry, 2012). NGS-based genotyping has recently enabled the simultaneous and near-exhaustive assay of every sequence polymorphism segregating in a mapping population (Huang et al., 2009; Davey et al., 2011). Genotyping-by-sequencing of mapping populations has first been employed in species with high-quality map-based reference sequences such as rice (Huang et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2010) or Drosophila (Andolfatto et al., 2011). This obviated the need for inferring marker order de novo from the genotypic data and enabled the efficient elimination of missing data through a sliding-window approach (Xie et al., 2010).

Because whole genome resequencing is still too expensive to deeply sequence a large number of individuals of species with large genomes, methods have been designed that reduce the genomic complexity either by restriction enzyme digestion (Altshuler et al., 2000; Baird et al., 2008; Elshire et al., 2011) or sequence capture with oligonucleotide baits (Hodges et al., 2007; Bainbridge et al., 2010). Reduced representation sequencing has been applied to anchor a large portion of the small genome (240 Mb) of woodland strawberry (Shulaev et al., 2011), but could assign only a minor fraction of the sequence assembly of the 4 Gb genome of the bread wheat progenitor Aegilops tauschii (Jia et al., 2013) to chromosomal locations.

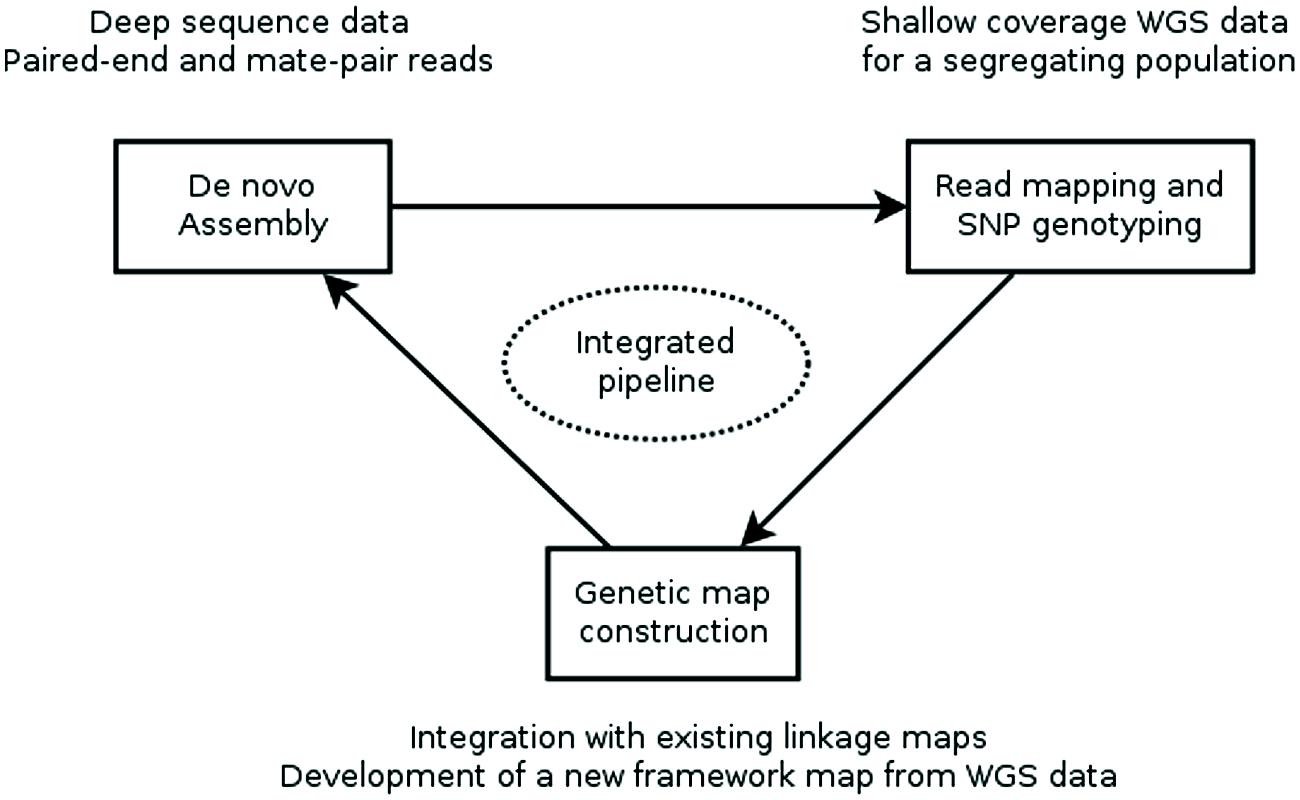

Recently, two reports (Mascher et al., 2013; Hahn et al., 2014) described computational pipelines that employ genotyping by whole genome sequencing of a genetic mapping population to construct an ultra-dense de novo linkage map of this population and place the assembly contigs of a WGS assembly into the map, producing a genetically anchored WGS assembly. The major computational steps of these procedures are: (i) constructing a WGS assembly from NGS data, (ii) mapping the sequence reads of the population to the assembly and computational genotype calling, (iii) building a genetic linkage map as a framework into which to (iv) integrate the WGS SNPs and assembly contigs harboring them (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Workflow for creating a genetically anchored WGS assembly. A WGS assembly is created from deep sequence data of a single, ideally homozygous individual using a combination of paired-end and long-jumping mate pair reads. Shallow coverage sequence data from the individuals of a genetic mapping population is mapped to this assembly and SNPs are detected and genotyped in silico in the population. This genotypic data is used to construct a linkage map or is integrated with existing maps. Finally, contigs are placed to the genetic map based on the segregation patterns of the SNP markers they carry. Currently, assembly, SNP genotyping and genetic map construction are performed consecutively with existing general-purpose tools. Future research should focus on developing an integrated pipeline, where an initial assembly is iteratively improved using sequence information from the mapping population.

The POPSEQ method (Mascher et al., 2013) utilizes established software for read mapping (BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009), variant calling [SAMtools (Li, 2011)] and map-making [MSTMap (Wu et al., 2008)]. SNPs detected by whole-genome sequencing of a mapping population are placed into a genetic framework of this same population through a simple nearest neighbor search. POPSEQ was first used to anchor genetically an existing genome assembly of barley (Hordeum vulgare), a monocotyledonous crop plant. The individuals of two mapping populations were sequenced to average onefold whole-genome coverage and after in silico genotyping, SNPs were placed into genetic framework maps of the populations which had been previously constructed from SNP array data (Comadran et al., 2012), through genotyping-by-sequencing (Poland et al., 2012), or were made from the WGS data of the population. The genetic positions of SNPs on WGS contigs were then used to assign chromosomal locations to the contigs of the WGS assembly. Two thirds (1.2 Gbp) of the 1.8 Gbp barley assembly could thus be genetically localized. Although the anchored portion of the assembly included 80% of the predicted gene loci, the assembly itself represented only the low-copy portion of the large (5 Gb) and highly repetitive barley genome (The International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2012).

A similar method [recombinant population genome construction, RPGC(Hahn et al., 2014)] likewise combines existing tools for sequence-based genotyping [BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009), SAMtools (Li, 2011), GATK (DePristo et al., 2011)] and genetic map construction [MSTMap (Wu et al., 2008)]. An additional feature of RPGC is the detection and correction of assembly errors caused by erroneously collapsing highly similar paralogous sequences. Such collapsed loci show segregation patterns inconsistent with a 1:2:1 distribution of genotypes in an F2 population. The authors evaluated RPGC with simulated sequence data of an F2 population of the worm C. elegans, a model species with a small genome (∼100 Mb). A de novo assembly with ALLPATHS-LG (Gnerre et al., 2011) consisted of only 88 scaffolds and covered 96% of the genome. Alignment to the C. elegans reference genome revealed that all scaffolds were ordered and oriented correctly, indicating that NGS-based sequence assembly and subsequent anchoring may be able to create almost complete and highly accurate sequence assemblies for species with small, repeat-poor genomes.

POPSEQ and RPGC are both targeted towards the construction of a reference sequence for a given species. Nevertheless, the availability of a reference genome does not at all depreciate further de novo assembly efforts. Structural variation is abundant in the genomes of many species (Feuk et al., 2006; Springer et al., 2009; Munoz-Amatriain et al., 2013; Marroni et al., 2014). Because complex events resulting in copy-number or presence absence variation are difficult to disentangle by mapping short NGS reads to a single reference sequence (Medvedev et al., 2009; Alkan et al., 2011a), reference-guided de novo assembly (Schneeberger et al., 2011) has been proposed as a tool to detect large-scale deletions, insertions and inversions. In a recent example, Gao et al. (2013) used sequence data from a segregating population of rice to assemble the genome sequence of one parent and correct errors in the existing assembly of the other parent.

Anchoring sequence scaffolds by population sequencing can also benefit on-going map-based sequencing projects. Although the construction of genetically anchored WGS assemblies is independent of a physical map and associated sequence resources (sequenced BAC clones, BAC end sequences), both can synergistically improve each other. As shown for barley, the sequence and marker resources provided by the assembly can be used to order and anchor the physical map (Ariyadasa et al., 2014) and, vice versa, the information about short-range connectivity obtained from clone overlaps can help further resolve the order of sequence contigs within recombination bins.

Applications of Genetically Ordered Sequence Assemblies

The genome sequence of a species is not an end in itself. But a genome constitutes a “research infrastructure” for biology (Olson, 1993), providing a stepping stone to a wide range of studies in basic and applied research that either makes possible or greatly accelerates the achievement of their aims. Many of these applications do not strictly necessitate a finished reference genome, i.e., near-complete pseudomolecules for each chromosome, but they can also be carried out with a partially ordered sequence assembly (possibly supplemented by physical mapping resources) that represents the majority of gene models. Such a partial order can be provided by genetically ordered WGS assemblies, which may function as hubs for gene isolation and empower comparative and evolutionary genomics.

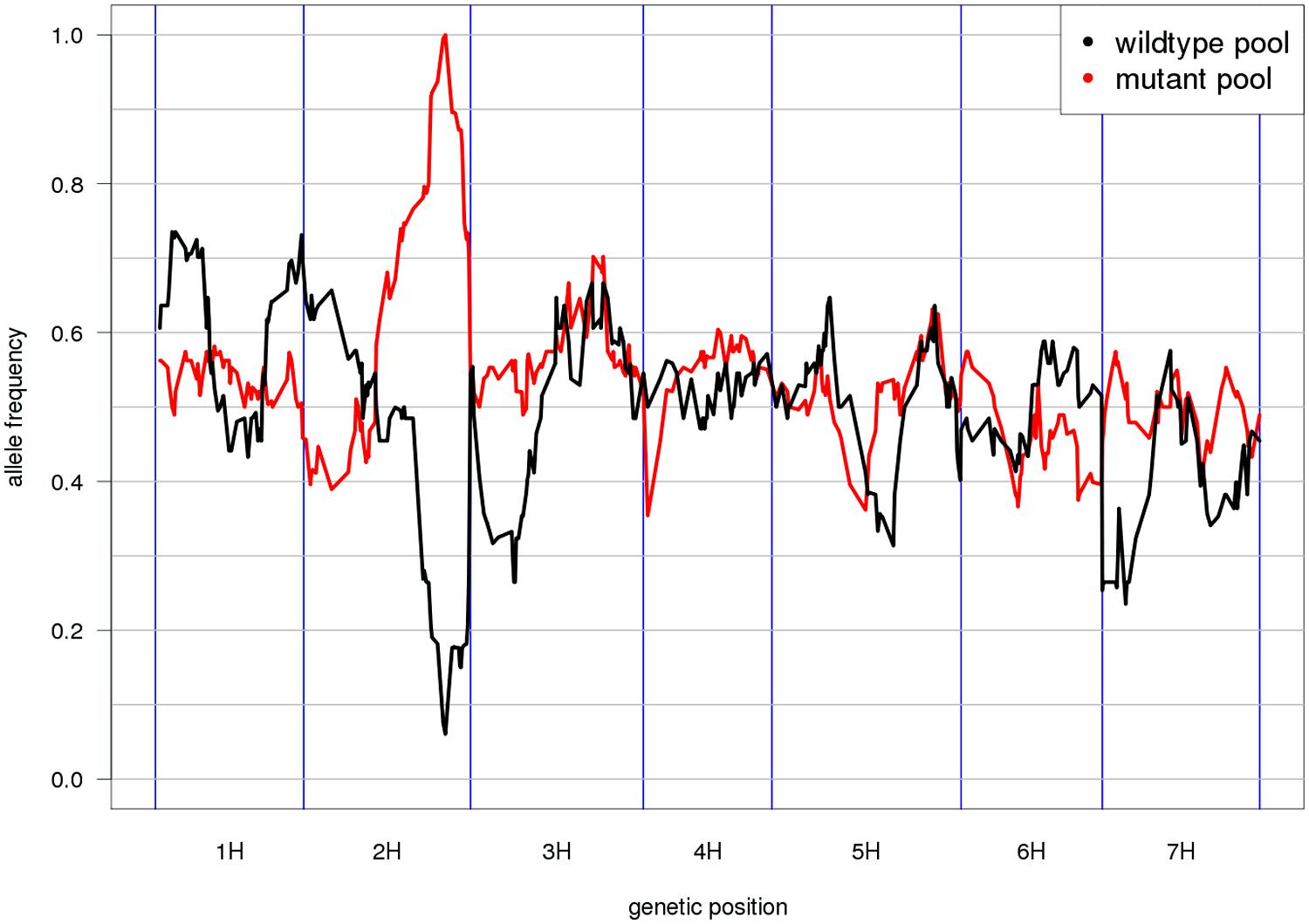

Mapping-by-sequencing is the combined use of bulked segregant analysis and NGS to identify genes that underlie phenotypic traits (Schneeberger and Weigel, 2011). After the initial implementation in Arabidopsis (Schneeberger et al., 2009), similar approaches have been developed in other plant and animal species (Doitsidou et al., 2010; Abe et al., 2012; Leshchiner et al., 2012). As the individuals of the mapping population are not genotyped individually but sequenced together in pools, only the distribution of allele frequencies across pools can be inspected and marker order cannot be determined de novo. Thus, genetic marker positions have to be inferred from an ordered reference sequence (Figure 2). Moreover, QTL mapping using whole-genome (Huang et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2013) or reduced representation resequencing (Baxter et al., 2011; Morris et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014) of biparental populations or association panels can take advantage of an ordered reference to search identified target intervals for anchored candidate genes.

FIGURE 2. Reference-based genetic mapping. A genetically ordered gene-space assembly can function as an effective surrogate for a reference genome sequence for the purpose of mapping-by-sequencing (Schneeberger et al., 2009). This example shows the allele frequency distribution along the POPSEQ map of barley (Mascher et al., 2013) in two contrasting bulks of the Oregon Wolfe Barley (OWB) population. The bulks were defined by presence or absence of the zeocriton (compressed ear) phenotype. Eighty-two OWB individuals were sequenced as part of POPSEQ and phenotypes were assigned based on publicly available phenotypic data (Carollo et al., 2005). The peak coincides with the genetic position of the gene ZEOCRITON (2H, 127 cM; Houston et al., 2013).

Genomics has been acknowledged as a powerful means to study evolutionary processes across several individuals of a single species (Luikart et al., 2003) and also across species boundaries (Sousa and Hey, 2013) to gain insights into how evolutionary forces such as adaptation to environmental conditions, natural selection, or random genetic drift shape the genomes of individuals and species. These fields have greatly benefited from the “democratization of sequencing” engendered by NGS technology (Stapley et al., 2010; Ekblom and Galindo, 2011). Genomic resources of non-model organisms can now quickly be assembled in order to support specific research aims (Ellegren, 2014). The recent study of Ellegren et al. (2012) used a genetically ordered draft genome sequence to dissect speciation between closely related songbird species. In an agronomic context, the International Oryza Map Alignment Project (Jacquemin et al., 2013) aims at sequencing the genomes of all members of the genus Oryza, i.e., relatives of cultivated rice. Starting from the premise that a single reference genome is not sufficient to assess the natural diversity across an entire genus, this project wants to establish a comprehensive genomic infrastructure to empower studies into the evolutionary dynamics of genome structure, conservation genomics and to assist crop improvement by introgressing beneficial alleles into elite germplasm. This endeavor could probably benefit from population sequencing data to anchor WGS assemblies and physical maps.

Challenges and Limitations

The most time-consuming step of anchoring a WGS assembly is the construction of a genetic population. While the sequencing and computational steps can be carried out in less than 6 months (Mascher et al., 2013), population development, in case of recombinant inbred line populations, may involve several rounds of self-fertilization, which can take several years. However, in plants, genetic mapping is routinely performed by researchers in academia and private industries and suitable mapping populations are often readily available. Moreover, plant mapping populations lend themselves very well to sequence-based mapping. Populations are generally started from highly homozygous genotypes and advanced recombinant inbred or doubled haploid progeny lines are nearly or completely homozygous, respectively. By contrast, F2 generations involve only one round of selfing after the initial cross. However, half of the genome of F2 individuals is expected to be heterozygous, requiring deeper sequence coverage for reliable genotyping. Even in obligate outcrossers, linkage maps can be made from crosses between heterozygous parents (Grattapaglia and Sederoff, 1994). Although controlled crosses cannot be made and the progeny of a single pair of parents is limited in number, genetic mapping is anything but impossible in animals. Linkage analysis in families of siblings from a cross between heterozygous parents is more complicated than in the progeny of homozygous lines (Maliepaard et al., 1997). Markers differ in the number of alleles and the number of heterozygous parents, and it can be impossible to determine the linkage phase of a marker, i.e., from which grandparent it was inherited. High-density linkage maps of the human genome have been constructed from multi-generation pedigrees (Dib et al., 1996). Similar methods based on three-generation pedigrees have been applied in other mammalian species such as macaque monkeys (Rogers et al., 2006) and domestic cats (Menotti-Raymond et al., 1999). Moreover, RIL populations have been created by mating of full-siblings in the laboratory animals mouse (Williams et al., 2001), rat (Pravenec et al., 1996), and fruit fly (Nuzhdin et al., 1997). If a robust genetic framework map can be computed, whole genome sequencing of the pedigree should allow populating this framework with additional markers and WGS sequence contigs. The heterozygosity of natural pedigrees may necessitate deeper sequencing to reliably score heterozygotes. Recent studies found that genotype calling from low- or medium-coverage (<15x) data often results in calling heterozygotes as homozygotes and can bias downstream analyses (Kim et al., 2011; Crawford and Lazzaro, 2012). A sliding-windows approach that aggregates sequence information across multiple SNP positions may help mitigate the effects of genotyping errors caused by low read depth.

In any species, linkage mapping has the inherent limitation that the maximally achievable resolution is determined by the recombination landscape, or more specifically, the ratio between physical and genetic distance along the genome. In grasses, for example, recombination events mainly occur in distal regions, whereas large peri-centromeric intervals are almost devoid of cross-overs. These so-called genetic centromeres correspond to a single large bin in a genetic map, which can only be resolved with extremely large mapping populations or possibly through alternative approaches such as physical mapping (van Oeveren et al., 2011), optical mapping (Dong et al., 2013), or methods based on chromosomal conformation capture (Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009; Burton et al., 2013).

In contrast to these intrinsic difficulties given by biological facts, algorithmic parameters of the anchoring process can be subject to directed improvement. The major computational tasks of assembly anchoring are de novo assembly, read mapping, variant calling and linkage map construction. One of the major determinants of anchoring efficiency is assembly contiguity. The longer a sequence contig is, the more likely it is that at least one sequence polymorphism can be detected to anchor it. Furthermore, longer contigs alleviate the problem of missing data. Even though the majority of individuals have missing genotype calls for single SNPs as a consequence of shallow-coverage sequencing (Huang et al., 2009; Mascher et al., 2013), aggregating genotypic information across all SNPs on a single contig results in consensus genotype calls with little or no missing data.

In the approaches of Mascher et al. (2013) and Hahn et al. (2014), read mapping and variant calling are performed with standard tools that are routinely used in large-scale resequencing projects (1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al., 2012; Tennessen et al., 2012) and will likely scale with the growing amount of raw data as population size and sequencing depth increase. By contrast, the majority of genetic mapping programs are still tailored to datasets encompassing only a few 1000 markers. The most commonly used tool to compute linkage maps form larger marker sets is MSTMap (Wu et al., 2008), for which excessive runtimes have been reported when marker order exceeds ∼100,000 (Howe et al., 2013). As the number of recombination bins in small biparental populations is limited, it can be envisaged to cluster markers prior to map-making based on their segregation patterns to obtain a smaller, yet fully informative set of framework markers. Moreover, focusing on a small number of high-confidence SNP loci may avoid the common problem of map-inflation, which is often caused by spurious cross-over events introduced by genotyping errors (Cheema and Dicks, 2009).

Moreover, valuable insights into the choice of parameters, the overall accuracy of the methods and the interplay of sequencing depth, population size, and final mapping resolution may be gained by performing de novo assembly and anchoring on real data gathered from species with existing high-quality reference genomes to be used as a gold standard for benchmarking.

Conclusion

The interest in the genome sequencing of non-model species (Ellegren, 2014) or economically important species with humongous genomes (Brenchley et al., 2012; Nystedt et al., 2013) has increased recently. Genome sequencing and assembly efforts and novel algorithmic development can be expected to intensify in the years to come, as genome sequencing of thousands of animal and plant species has been proposed (Genome 10K Community of Scientists, 2009; Johnson et al., 2012). We conclude with reiterating the advice of Gao et al. (2013) that each genome assembly project should, if at all possible, obtain WGS data from at least one segregating population. Short read assembly will remain a central part of any genome project as long as advances in sequencing technology will not make possible chromosome-sized sequence scaffolds. In the meantime, methods such as genetic anchoring will always be necessary to enhance the utility of fragmented WGS assemblies.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Barley genome sequencing in the lab of Nils Stein is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Research and Education (BMBF) in frame of the TRITEX project (FKZ 0315954).

References

1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Abecasis, G. R., Auton, A., Brooks, L. D., Depristo, M. A., Durbin, R. M.,et al. (2012). An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491, 56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632

Abe, A., Kosugi, S., Yoshida, K., Natsume, S., Takagi, H., Kanzaki, H.,et al. (2012). Genome sequencing reveals agronomically important loci in rice using MutMap. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 174–178. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2095

Alkan, C., Coe, B. P., and Eichler, E. E. (2011a). Genome structural variation discovery and genotyping. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 363–376. doi: 10.1038/nrg2958

Alkan, C., Sajjadian, S., and Eichler, E. E. (2011b). Limitations of next-generation genome sequence assembly. Nat. Methods 8, 61–65. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1527

Altshuler, D., Pollara, V. J., Cowles, C. R., Van Etten, W. J., Baldwin, J., Linton, L.,et al. (2000). An SNP map of the human genome generated by reduced representation shotgun sequencing. Nature 407, 513–516. doi: 10.1038/35035083

Amborella Genome Project. (2013). The Amborella genome and the evolution of flowering plants. Science 342:1241089. doi: 10.1126/science.1241089

Andolfatto, P., Davison, D., Erezyilmaz, D., Hu, T. T., Mast, J., Sunayama-Morita, T.,et al. (2011). Multiplexed shotgun genotyping for rapid and efficient genetic mapping. Genome Res. 21, 610–617. doi: 10.1101/gr.115402.110

Andrews, K. R., and Luikart, G. (2014). Recent novel approaches for population genomics data analysis. Mol. Ecol. 23, 1661–1667. doi: 10.1111/mec.12686

Ariyadasa, R., Mascher, M., Nussbaumer, T., Schulte, D., Frenkel, Z., Poursarebani, N.,et al. (2014). A sequence-ready physical map of barley anchored genetically by two million single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Plant Physiol. 164, 412–423. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.228213

Ariyadasa, R., and Stein, N. (2012). Advances in BAC-based physical mapping and map integration strategies in plants. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012:184854. doi: 10.1155/2012/184854

Bainbridge, M. N., Wang, M., Burgess, D. L., Kovar, C., Rodesch, M. J., D′ascenzo, M.,et al. (2010). Whole exome capture in solution with 3 Gbp of data. Genome Biol. 11, R62. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-6-r62

Baird, N. A., Etter, P. D., Atwood, T. S., Currey, M. C., Shiver, A. L., Lewis, Z. A.,et al. (2008). Rapid SNP discovery and genetic mapping using sequenced RAD markers. PLoS ONE 3:e3376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003376

Baxter, S. W., Davey, J. W., Johnston, J. S., Shelton, A. M., Heckel, D. G., Jiggins, C. D.,et al. (2011). Linkage mapping and comparative genomics using next-generation RAD sequencing of a non-model organism. PLoS ONE 6:e19315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019315

Bradnam, K. R., Fass, J. N., Alexandrov, A., Baranay, P., Bechner, M., Birol, I.,et al. (2013). Assemblathon 2: evaluating de novo methods of genome assembly in three vertebrate species. Gigascience 2:10. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-2-10

Brenchley, R., Spannagl, M., Pfeifer, M., Barker, G. L., D’Amore, R., Allen, A. M.,et al. (2012). Analysis of the bread wheat genome using whole-genome shotgun sequencing. Nature 491, 705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature11650

Brunner, S., Fengler, K., Morgante, M., Tingey, S., and Rafalski, A. (2005). Evolution of DNA sequence nonhomologies among maize inbreds. Plant Cell 17, 343–360. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025627

Burton, J. N., Adey, A., Patwardhan, R. P., Qiu, R., Kitzman, J. O., and Shendure, J. (2013). Chromosome-scale scaffolding of de novo genome assemblies based on chromatin interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 1119–1125. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2727

Carollo, V., Matthews, D. E., Lazo, G. R., Blake, T. K., Hummel, D. D., Lui, N.,et al. (2005). GrainGenes 2.0. an improved resource for the small-grains community. Plant Physiol. 139, 643–651. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.064485

Cheema, J., and Dicks, J. (2009). Computational approaches and software tools for genetic linkage map estimation in plants. Brief. Bioinform. 10, 595–608. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbp045

Comadran, J., Kilian, B., Russell, J., Ramsay, L., Stein, N., Ganal, M.,et al. (2012). Natural variation in a homolog of Antirrhinum CENTRORADIALIS contributed to spring growth habit and environmental adaptation in cultivated barley. Nat. Genet. 44, 1388–1392. doi: 10.1038/ng.2447

Crawford, J. E., and Lazzaro, B. P. (2012). Assessing the accuracy and power of population genetic inference from low-pass next-generation sequencing data. Front. Genet. 3:66. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00066

Davey, J. W., Hohenlohe, P. A., Etter, P. D., Boone, J. Q., Catchen, J. M., and Blaxter, M. L. (2011). Genome-wide genetic marker discovery and genotyping using next-generation sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 499–510. doi: 10.1038/nrg3012

DePristo, M. A., Banks, E., Poplin, R., Garimella, K. V., Maguire, J. R., Hartl, C.,et al. (2011). A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 43, 491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806

Dib, C., Faure, S., Fizames, C., Samson, D., Drouot, N., Vignal, A.,et al. (1996). A comprehensive genetic map of the human genome based on 5,264 microsatellites. Nature 380, 152–154. doi: 10.1038/380152a0

Doitsidou, M., Poole, R. J., Sarin, S., Bigelow, H., and Hobert, O. (2010). C. elegans mutant identification with a one-step whole-genome-sequencing and SNP mapping strategy. PLoS ONE 5:e15435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015435

Dong, Y., Xie, M., Jiang, Y., Xiao, N., Du, X., Zhang, W.,et al. (2013). Sequencing and automated whole-genome optical mapping of the genome of a domestic goat (Capra hircus). Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 135–141. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2478

Ekblom, R., and Galindo, J. (2011). Applications of next generation sequencing in molecular ecology of non-model organisms. Heredity (Edinb) 107, 1–15. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.152

Ellegren, H. (2014). Genome sequencing and population genomics in non-model organisms. Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst.) 29, 51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2013.09.008

Ellegren, H., Smeds, L., Burri, R., Olason, P. I., Backstrom, N., Kawakami, T.,et al. (2012). The genomic landscape of species divergence in Ficedula flycatchers. Nature 491, 756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature11584

Elshire, R. J., Glaubitz, J. C., Sun, Q., Poland, J. A., Kawamoto, K., Buckler, E. S.,et al. (2011). A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS ONE 6:e19379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019379

Feuillet, C., Leach, J. E., Rogers, J., Schnable, P. S., and Eversole, K. (2011). Crop genome sequencing: lessons and rationales. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.10.005

Feuk, L., Carson, A. R., and Scherer, S. W. (2006). Structural variation in the human genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 85–97. doi: 10.1038/nrg1767

Gao, Z. Y., Zhao, S. C., He, W. M., Guo, L. B., Peng, Y. L., Wang, J. J.,et al. (2013). Dissecting yield-associated loci in super hybrid rice by resequencing recombinant inbred lines and improving parental genome sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 14492–14497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306579110

Genome 10K Community of Scientists. (2009). Genome 10K: a proposal to obtain whole-genome sequence for 10,000 vertebrate species. J. Hered. 100, 659–674. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp086

Gnerre, S., Maccallum, I., Przybylski, D., Ribeiro, F. J., Burton, J. N., Walker, B. J.,et al. (2011). High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1513–1518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017351108

Grattapaglia, D., and Sederoff, R. (1994). Genetic linkage maps of Eucalyptus grandis and Eucalyptus urophylla using a pseudo-testcross: mapping strategy and RAPD markers. Genetics 137, 1121–1137.

Groenen, M. A., Archibald, A. L., Uenishi, H., Tuggle, C. K., Takeuchi, Y., Rothschild, M. F.,et al. (2012). Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and evolution. Nature 491, 393–398. doi: 10.1038/nature11622

Hahn, M. W., Zhang, S. V., and Moyle, L. C. (2014). Sequencing, assembling, and correcting draft genomes using recombinant populations. G3 (Bethesda) 4, 669–679. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.010264

Hodges, E., Xuan, Z., Balija, V., Kramer, M., Molla, M. N., Smith, S. W.,et al. (2007). Genome-wide in situ exon capture for selective resequencing. Nat. Genet. 39, 1522–1527. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.42

Houston, K., Mckim, S. M., Comadran, J., Bonar, N., Druka, I., Uzrek, N.,et al. (2013). Variation in the interaction between alleles of HvAPETALA2 and microRNA172 determines the density of grains on the barley inflorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 16675–16680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311681110

Howe, K., Clark, M. D., Torroja, C. F., Torrance, J., Berthelot, C., Muffato, M.,et al. (2013). The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 496, 498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature12111

Huang, X., Feng, Q., Qian, Q., Zhao, Q., Wang, L., Wang, A.,et al. (2009). High-throughput genotyping by whole-genome resequencing. Genome Res. 19, 1068–1076. doi: 10.1101/gr.089516.108

Jacquemin, J., Bhatia, D., Singh, K., and Wing, R. A. (2013). The International Oryza Map Alignment Project: development of a genus-wide comparative genomics platform to help solve the 9 billion-people question. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.02.014

Jia, J., Zhao, S., Kong, X., Li, Y., Zhao, G., He, W.,et al. (2013). Aegilops tauschii draft genome sequence reveals a gene repertoire for wheat adaptation. Nature 496, 91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature12028

Johnson, M. T., Carpenter, E. J., Tian, Z., Bruskiewich, R., Burris, J. N., Carrigan, C. T.,et al. (2012). Evaluating methods for isolating total RNA and predicting the success of sequencing phylogenetically diverse plant transcriptomes. PLoS ONE 7:e50226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050226

Kim, S. Y., Lohmueller, K. E., Albrechtsen, A., Li, Y. R., Korneliussen, T., Tian, G.,et al. (2011). Estimation of allele frequency and association mapping using next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 12:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-231

Leshchiner, I., Alexa, K., Kelsey, P., Adzhubei, I., Austin-Tse, C. A., Cooney, J. D.,et al. (2012). Mutation mapping and identification by whole-genome sequencing. Genome Res. 22, 1541–1548. doi: 10.1101/gr.135541.111

Li, H. (2011). A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 27, 2987–2993. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr509

Li, H., and Durbin, R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324

Li, R., Zhu, H., Ruan, J., Qian, W., Fang, X., Shi, Z.,et al. (2010). De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 20, 265–272. doi: 10.1101/gr.097261.109

Lieberman-Aiden, E., Van Berkum, N. L., Williams, L., Imakaev, M., Ragoczy, T., Telling, A.,et al. (2009). Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326, 289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369

Ling, H. Q., Zhao, S., Liu, D., Wang, J., Sun, H., Zhang, C.,et al. (2013). Draft genome of the wheat A-genome progenitor Triticum urartu. Nature 496, 87–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11997

Liu, H., Bayer, M., Druka, A., Russell, J. R., Hackett, C. A., Poland, J.,et al. (2014). An evaluation of genotyping by sequencing (GBS) to map the Breviaristatum-e (ari-e) locus in cultivated barley. BMC Genomics 15:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-104

Luikart, G., England, P. R., Tallmon, D., Jordan, S., and Taberlet, P. (2003). The power and promise of population genomics: from genotyping to genome typing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4, 981–994. doi: 10.1038/nrg1226

Maliepaard, C., Jansen, J., and Van Ooijen, J. (1997). Linkage analysis in a full-sib family of an outbreeding plant species: overview and consequences for applications. Genet. Res. 70, 237–250. doi: 10.1017/S0016672397003005

Marroni, F., Pinosio, S., and Morgante, M. (2014). Structural variation and genome complexity: is dispensable really dispensable? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 18C, 31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.01.003

Mascher, M., Muehlbauer, G. J., Rokhsar, D. S., Chapman, J., Schmutz, J., Barry, K.,et al. (2013). Anchoring and ordering NGS contig assemblies by population sequencing (POPSEQ). Plant J. 76, 718–727. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12319

Mayer, K. F., Taudien, S., Martis, M., Simkova, H., Suchankova, P., Gundlach, H.,et al. (2009). Gene content and virtual gene order of barley chromosome 1H. Plant Physiol. 151, 496–505. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.142612

Medvedev, P., Stanciu, M., and Brudno, M. (2009). Computational methods for discovering structural variation with next-generation sequencing. Nat. Methods 6, S13–S20. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1374

Menotti-Raymond, M., David, V. A., Lyons, L. A., Schaffer, A. A., Tomlin, J. F., Hutton, M. K.,et al. (1999). A genetic linkage map of microsatellites in the domestic cat (Felis catus). Genomics 57, 9–23. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5743

Morgan, T. H., Sturtevant, A. H., Muller, H. J., and Bridges, C. B. (1922). The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

Morris, G. P., Ramu, P., Deshpande, S. P., Hash, C. T., Shah, T., Upadhyaya, H. D.,et al. (2013). Population genomic and genome-wide association studies of agroclimatic traits in sorghum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 453–458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215985110

Munoz-Amatriain, M., Eichten, S. R., Wicker, T., Richmond, T. A., Mascher, M., Steuernagel, B.,et al. (2013). Distribution, functional impact, and origin mechanisms of copy number variation in the barley genome. Genome Biol. 14, R58. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-6-r58

Nuzhdin, S. V., Pasyukova, E. G., Dilda, C. L., Zeng, Z. B., and Mackay, T. F. (1997). Sex-specific quantitative trait loci affecting longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 9734–9739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9734

Nystedt, B., Street, N. R., Wetterbom, A., Zuccolo, A., Lin, Y. C., Scofield, D. G.,et al. (2013). The Norway spruce genome sequence and conifer genome evolution. Nature 497, 579–584. doi: 10.1038/nature12211

Olson, M. V. (1993). The human genome project. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 4338–4344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4338

Poland, J. A., Brown, P. J., Sorrells, M. E., and Jannink, J. L. (2012). Development of high-density genetic maps for barley and wheat using a novel two-enzyme genotyping-by-sequencing approach. PLoS ONE 7:e32253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032253

Pravenec, M., Gauguier, D., Schott, J. J., Buard, J., Kren, V., Bila, V.,et al. (1996). A genetic linkage map of the rat derived from recombinant inbred strains. Mamm. Genome 7, 117–127. doi: 10.1007/s003359900031

Rogers, J., Garcia, R., Shelledy, W., Kaplan, J., Arya, A., Johnson, Z.,et al. (2006). An initial genetic linkage map of the rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) genome using human microsatellite loci. Genomics 87, 30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.10.004

Schneeberger, K., Ossowski, S., Lanz, C., Juul, T., Petersen, A. H., Nielsen, K. L.,et al. (2009). SHOREmap: simultaneous mapping and mutation identification by deep sequencing. Nat. Methods 6, 550–551. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0809-550

Schneeberger, K., Ossowski, S., Ott, F., Klein, J. D., Wang, X., Lanz, C.,et al. (2011). Reference-guided assembly of four diverse Arabidopsis thaliana genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 10249–10254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107739108

Schneeberger, K., and Weigel, D. (2011). Fast-forward genetics enabled by new sequencing technologies. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.02.006

Shulaev, V., Sargent, D. J., Crowhurst, R. N., Mockler, T. C., Folkerts, O., Delcher, A. L.,et al. (2011). The genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Nat. Genet. 43, 109–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.740

Sousa, V., and Hey, J. (2013). Understanding the origin of species with genome-scale data: modelling gene flow. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 404–414. doi: 10.1038/nrg3446

Springer, N. M., Ying, K., Fu, Y., Ji, T., Yeh, C. T., Jia, Y.,et al. (2009). Maize inbreds exhibit high levels of copy number variation (CNV) and presence/absence variation (PAV) in genome content. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.100073

Stapley, J., Reger, J., Feulner, P. G., Smadja, C., Galindo, J., Ekblom, R.,et al. (2010). Adaptation genomics: the next generation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.09.002

Tennessen, J. A., Bigham, A. W., O’Connor, T. D., Fu, W., Kenny, E. E., Gravel, S.,et al. (2012). Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science 337, 64–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1219240

The International Barley Genome Sequencing Consortium. (2012). A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature 491, 711–716. doi: 10.1038/nature11543

van Oeveren, J., De Ruiter, M., Jesse, T., Van Der Poel, H., Tang, J., Yalcin, F.,et al. (2011). Sequence-based physical mapping of complex genomes by whole genome profiling. Genome Res. 21, 618–625. doi: 10.1101/gr.112094.110

Wicker, T., Mayer, K. F. X., Gundlach, H., Martis, M., Steuernagel, B., Scholz, U.,et al. (2011). Frequent gene movement and pseudogene evolution is common to the large and complex genomes of wheat, barley, and their relatives. Plant Cell 23, 1706–1718. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.086629

Williams, R. W., Gu, J., Qi, S., and Lu, L. (2001). The genetic structure of recombinant inbred mice: high-resolution consensus maps for complex trait analysis. Genome Biol. 2:RESEARCH0046.

Wu, Y., Bhat, P. R., Close, T. J., and Lonardi, S. (2008). Efficient and accurate construction of genetic linkage maps from the minimum spanning tree of a graph. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000212

Keywords: next-generation sequencing, whole-genome shotgun assembly, assembly anchoring, genetic mapping, genotyping-by-sequencing, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, mapping populations

Citation: Mascher M and Stein N (2014) Genetic anchoring of whole-genome shotgun assemblies. Front. Genet. 5:208. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00208

Received: 16 May 2014; Paper pending published: 12 June 2014;

Accepted: 19 June 2014; Published online: 07 July 2014.

Edited by:

Yih-Horng Shiao, US Patent Trademark Office, USAReviewed by:

Beat Keller, University of Zurich, SwitzerlandMartien Groenen, Wageningen University, Netherlands

Copyright © 2014 Mascher and Stein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martin Mascher, Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Corrensstraße 3, 06466 Stadt Seeland, OT Gatersleben, Germany e-mail:bWFzY2hlckBpcGstZ2F0ZXJzbGViZW4uZGU=

Martin Mascher

Martin Mascher Nils Stein

Nils Stein