94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Genet., 01 February 2013

Sec. Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics

Volume 3 - 2012 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2012.00318

This article is part of the Research TopicFunctional Polymorphisms of Xenobiotics Metabolizing Enzymes (XME)View all 21 articles

More than 30 years of genetic research on the CYP2C19 gene alone has identified approximately 2,000 reference single nucleotide polymorphisms (rsSNPs) containing 28 registered alleles in the P450 Allele Nomenclature Committee and the number continues to increase. However, knowledge of CYP2C19 SNPs remains limited with respect to biological functions. Functional information on the variant is essential for justifying its clinical use. Only common variants (minor allele frequency >5%) that represent CYP2C19*2, *3, *17, and others have been mostly studied. Discovery of new genetic variants is outstripping the generation of knowledge on the biological meanings of existing variants. Alternative strategies may be needed to fill this gap. The present study summarizes up-to-date knowledge on functional CYP2C19 variants discovered in phenotyped humans studied at the molecular level in vitro. Understanding the functional meanings of CYP2C19 variants is an essential step toward shifting the current medical paradigm to highly personalized therapeutic regimens.

Pharmacogenetics incorporates genetic information into clinical decision making to avoid adverse drug effects and improve drug efficacy. Drug responses can be affected by three major factors: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and the underlying molecular mechanisms of disease. Because the DNA sequence of CYP2C19 is highly polymorphic, this may account for much of the variability in the pharmacokinetics of drugs metabolized by CYP2C19. CYP2C19 metabolizes a number of drugs, including the antiulcer drug omeprazole (Andersson et al., 1992), the antiplatelet drug clopidogrel (Mills et al., 1992), the anticonvulsant mephenytoin (Andersson et al., 1992; Bertilsson, 1995), the antimalarial drug proguanil (Helsby et al., 1991; Ward et al., 1991), the anxiolytic drug diazepam (Bertilsson, 1995; Wan et al., 1996; Qin et al., 1999), and certain antidepressants such as citalopram (Sindrup et al., 1993), imipramine (Skjelbo et al., 1991), amitriptyline (Bouman et al., 2011), and clomipramine (Nielsen et al., 1994). The phenotype of CYP2C19 metabolic capacity can be categorized based on genotypes and includes extensive metabolizers (EM, two wild-type functional alleles), intermediate metabolizers (IM, two reduced functional alleles or one null allele and a functional allele), and poor metabolizers (PM, two non-functional alleles) of drugs. Undesirable side effects such as prolonged sedation and unconsciousness have been observed after administration of diazepam in CYP2C19 PMs (Bertilsson, 1995). In addition, a diminished response to the antiplatelet drug clopidogrel has been found in CYP2C19 PMs (Hulot et al., 2006; Brandt et al., 2007; Mega et al., 2009). However, proton pump inhibitor drugs, including omeprazole and lansoprazole, exhibit a greater cure rate for gastric ulcers with Helicobacter pylori infections in PMs than in EMs due to higher plasma concentrations of the parent drugs in PMs (Sohn et al., 1997; Furuta et al., 1998). In any case, clinical decision strategies following CYP2C19 genotyping suggest two regimens: an adjustment of the drug dose according to the genotype or an alternative drug choice. However, the greatest uncertainty is in the IM group, in which interindividual variation is clearly observed. The underlying mechanism for this variation remains unclear. Integration of other factors, such as clinical factors, environmental factors, and drug response-modulating factors may be needed to understand this variation. A successful launch of personalized medicine in relation to CYP2C19 drugs would be impossible without resolving the variation in the IM group. The majority of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetic studies have been conducted using CYP2C19*2, *3, and *17 variants. This article presents a collection of functional CYP2C19 variants evidenced in human studies and discusses their utilities and limitations for clinical use.

Four CYP2C genes have been identified in humans: CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C18, and CYP2C19. Among them, CYP2C19 is the most polymorphic enzyme, and it metabolizes many important clinical drugs. Its activity can be inhibited by fluoxetine (Jeppesen et al., 1996), fluvoxamine (Jeppesen et al., 1996; Yao et al., 2003), lansoprazole, pantoprazole (Li et al., 2004), and ticlopidine (Tateishi et al., 1999), and can be induced by phenobarbital and rifampin (Madan et al., 2003). A number of CYP2C19 polymorphisms have been identified. However, defining the quantitative value of altered functionality of the identified variant, such as the unequivocal percent value of wild-type activity, is difficult except for null alleles. One reason for this difficulty is from the different functional assay systems that include various molecular techniques with lab-to-lab variations. For example, to study protein-coding variants, enzyme expression systems have included yeast (Ferguson et al., 1998), baculovirus (Mankowski, 1999), and Escherichia coli (Lee et al., 2009), and have depended on the preference or experimental conditions of the laboratory. All systems are useful biochemical tools for determining relative activity compared to wild-type activity in vitro. However, results of comparative parameters are not identical among the assay systems. In addition, not all in vitro assay systems reflect the same phenomena of those conditions in vivo. Therefore, a quantitative comparison of CYP2C19 variants with wild-type CYP2C19 has been difficult and should be interpreted with great caution.

New CYP2C19 variants have been discovered by direct DNA sequencing using two kinds of human DNA samples, normal healthy subjects or phenotyped individuals. CYP2C19 variants identified by DNA sequencing in individuals that have been characterized by clinicians as PMs or outliers include CYP2C19*2, *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, *8, *16, *17, and *26, all based on comparisons to wild-type CYP2C19 activity in vivo or in in vitro functional studies, with the exception of CYP2C19*16 (Wilkinson et al., 1989; Balian et al., 1995). Briefly, CYP2C19*2 is the most common variant, which is a single base pair mutation in exon 5 (G > A), resulting an aberrant splice site (de Morais et al., 1994b). Creation of this splice site alters the reading frame of the mRNA beginning at amino acid 215 and produces a premature stop codon of 20 amino acids downstream (de Morais et al., 1994b); in that study, 7 of 10 Caucasians and 10 of 17 Japanese PMs for mephenytoin were homozygous for this mutation. CYP2C19*3 has been found in Japanese PMs that were not homozygous for CYP2C19*2 (de Morais et al., 1994a). CYP2C19*3, the result of the 636G > A mutation in exon 4, creates a premature stop codon. CYP2C19*2 and *3 are responsible for the majority of PM phenotypes in the metabolism of CYP2C19 substrate drugs (Goldstein, 2001; Xie et al., 2001). CYP2C19*4, an A > G mutation in the initiation codon, was identified in Caucasian PMs of mephenytoin (Ferguson et al., 1998); in that study, CYP2C19*4 cDNA was not expressed into the protein in a yeast expression system or an in vitro translation assay, whereas the CYP2C19*1 cDNA was expressed and translated in both systems, suggesting a new PM allele. CYP2C19*5, a 1297C > T mutation in the heme-binding region, results in a Arg433Trp substitution and has been identified in a single Chinese PM of S-mephenytoin (Xiao et al., 1997) and 1 in 37 white PMs of S-mephenytoin (Ibeanu et al., 1998a). A recombinant enzyme activity study indicated that this allele abolishes the activity toward S-mephenytoin and tolbutamide, suggesting a PM allele (Ibeanu et al., 1998a). CYP2C19*6, a 395G > A mutation in exon 3, leads to an Arg132Gln substitution and has been found in a white PM outlier of mephenytoin (Ibeanu et al., 1998b). In this study, recombinant protein of CYP2C19*6 prepared in an E. coli expression system exhibited negligible activity toward S-mephenytoin compared to that of wild-type, indicating that the CYP2C19*6 allele contributes to the PM phenotype in whites. CYP2C19*7 is a T > A mutation at the 5′ donor splice site of intron 5 and results in a PM allele. This allele has been found in a mephenytoin PM outlier of a Danish individual (Ibeanu et al., 1999). CYP2C19*8, a T358C change in exon 3 that results in a Trp120Arg substitution, was first identified in a French subject enrolled in a cancer risk study with mephenytoin activity (Benhamou et al., 1997). In a recombinant study, the CYP2C19*8 protein exhibited a 90% decrease in activity for S-mephenytoin and a 70% reduction in tolbutamide activity compared to wild-type (Ibeanu et al., 1999). CYP2C19*16 is a 1324C > T change in exon 9 located close to the heme-binding region that results in a Arg442Cys substitution, and was first identified in a Japanese individual with a low capacity to metabolize mephobarbital (Morita et al., 2004). Because this amino acid change is located close to the heme-binding site, it is proposed to have decreased activity for CYP2C19 substrate drugs. CYP2C19*17 is an allele carrying −806C > T and −3042C > T found in the 5′ regulatory region (Sim et al., 2006). Individuals with CYP2C19*17/*17 exhibit 35–40% lower omeprazole area under the plasma concentration-time curve values than the individuals having CYP2C19*1/*1, suggesting that this allele leads to an increased metabolizer phenotype. In Sim et al. (2006), a reporter assay showed increased transcriptional activity of CYP2C19*17 and electrophoretic mobility shift assays showed specific binding of human hepatic nuclear proteins to an element carrying −806T but not −806C. CYP2C19*26, a 766G > A change in exon 5 resulting in a D256N substitution, was first identified in an omeprazole PM outlier of a Vietnamese individual; a recombinant enzyme activity assay prepared in an E. coli expression system showed a significant decrease in Vmax for omeprazole (2.6-fold) and mephenytoin metabolism (twofold; Lee et al., 2009).

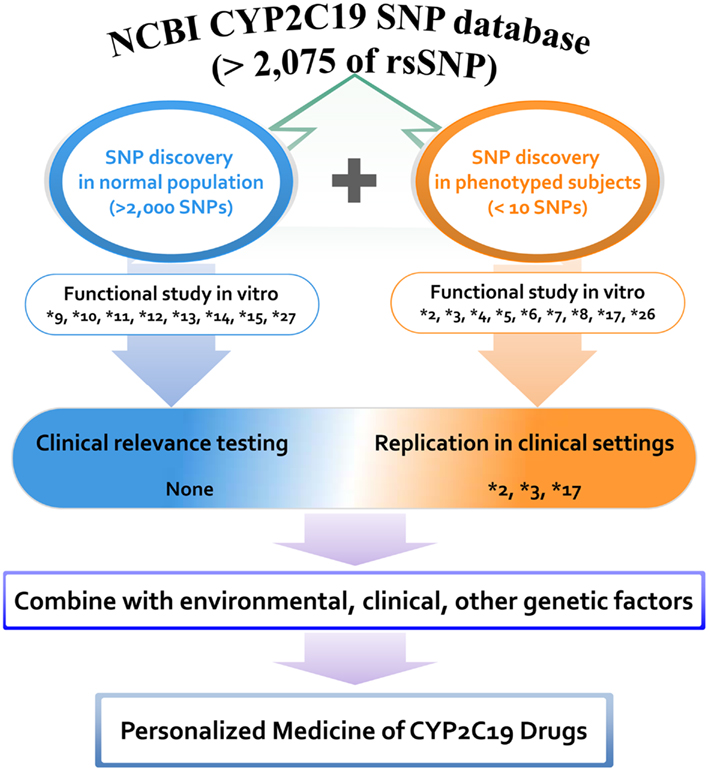

The majority of other alleles have been discovered in various human projects by using DNAs obtained from normal populations. CYP2C19 variants that were discovered without phenotyping but which were characterized by in vitro systems include *9, *10, *11, *12, *13, *14, *15, and *27. A positive correlation between in vitro data and in vivo biological evidence would strengthen the incorporation of genetic data into clinical practice. Although more than 2,000 variants have been identified in the last several decades, alleles characterized via either in vivo or in vitro studies are limited to less than 20 variants, indicating a huge gap between the number of discovered single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and the number of functionally known SNPs. A summary of CYP2C19 variants that have been discovered and characterized in phenotyped human subjects is presented in Figure 1. Clinical application of variant alleles with functional information is critical in the clinical setting for individualized drug therapy. Profiling of rare variants reflecting interindividual variability in drug responses could be difficult, but is needed for incorporating CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics into the clinical decision making process.

Figure 1. Distribution of CYP2C19 variants discovered and characterized in phenotyped human subjects and normal populations. A total of 2,075 rsSNPs have been reported in NCBI CYP2C19 SNP database at the present stage. Among them the number of SNPs that are functionally studied in vitro and validated in vivo is limited. Proposed scheme is for the personalized medicine of CYP2C19 substrate drugs.

Because CYP2C19*2 and CYP2C19*3 are the most common and defective variants (Goldstein et al., 1997; Xie et al., 2001), a number of reports have described the clinical significance of these variants. The promoter variant CYP2C19*17 has been shown to be associated with increased CYP2C19 activity due to increased transcription of CYP2C19. Therefore, homozygous carriers of CYP2C19*17 exhibit rapid clearance of CYP2C19 substrate drugs compared to wild-type (Sim et al., 2006; Ingelman-Sundberg et al., 2007; Rudberg et al., 2008). As a consequence, individuals with CYP2C19*17 are likely to exhibit a lack of response to certain PPIs and antidepressants compared to EMs (CYP2C19*1/*1); this is due to rapid clearance of the drugs. Although most variation in the drug response can be explained by these three variants (CYP2C19*2, *3, and *17), high interindividual variation in subjects homozygous for CYP2C19*1 has also been observed (Sim et al., 2006). It is well-known that CYP2C19 activity is influenced by clinical factors, various inducers and inhibitors, drug–drug interactions, and other genetic polymorphisms in drug response-related genes. Because most studies have translated drug response data after genotyping for common alleles only, variants that have not been detected may be missing. More candidate SNPs may improve the translational process for drug responses. The limited amount of genotyping in current research may be due to the lack of data on the functional significance (in vitro or in vivo) of the allele and the low or undetermined allele frequency in the study population. Therefore, information on the functional significance of the variant allele would help researchers to include more candidate SNPs for genotyping in their clinical studies. This would ultimately improve translational quality in clinical settings and would be a beginning step for launching personalized medicine because physicians could easily communicate with patients using biological evidence for the drug response prediction instead of explaining the statistical risk without biological significance.

Many clinical drugs are metabolized by CYP2C19, and hence, the pharmacokinetics of CYP2C19 substrate drugs is influenced by CYP2C19 polymorphisms. Altered CYP2C19 activity can be, at least in part, predicted by the CYP2C19 genotype. The most extensively used polymorphic variants for genotype and phenotype association studies have been CYP2C19*2, *3, and *17 (Goldstein, 2001; Xie et al., 2001; Desta et al., 2002). Ethnic differences in the frequency of CYP2C19*2, *3, and *17 alleles are summarized in Table 1. Identification of PM alleles or the CYP2C19*17 variant in patients and the modification of therapy regimens does not represent personalized drug therapy but is useful for the prevention of side effects. Because the human genome is very difficult to understand and drug responses are affected by several modulating genes with environmental factors, the development of personalized medicine for CYP2C19 substrate drugs using only CYP2C19 and other modulating gene’s genotypes is nearly impossible. However, several FDA-approved drugs are strongly affected by CYP2C19 genotypes (see Table 2), and their labels include pharmacogenomic information (http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ScienceResearch/ResearchAreas/Pharmacogenetics). Briefly, diazepam is demethylated by CYP2C19 (Jung et al., 1997), and hence its pharmacokinetics are affected by CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms. The plasma half-life of diazepam is approximately fourfold longer in individuals with PM genotypes than in individuals homozygous for wild-type CYP2C19*1 (Wan et al., 1996; Qin et al., 1999). PMs may be at risk for toxic doses of diazepam and therefore more care is required to determine the diazepam dose for such subjects, especially for certain ethnicities because the frequency of PM differs between ethnic groups, being 3–6% in whites and blacks, 13–23% in Asians, and 38–79% in Polynesians and Micronesians (Kaneko et al., 1999; Xie et al., 2001). The CYP2C19 genotype affects the metabolism of PPIs, resulting in altered cure rates for H. pylori infection in peptic ulcer patients. In a previous study, the cure rate of peptic or duodenal ulcers for Japanese patients that received dual therapy with omeprazole (20 mg/day for 2 weeks) and amoxicillin (2,000 mg/day for 2 weeks) was 100% in CYP2C19 PMs, 60% for those who were heterozygous for one mutant allele, and 29% in individuals homozygous for the CYP2C19*1 allele (Furuta et al., 1998). These differences are attributable to the CYP2C19 PM genotype’s impaired metabolism of PPIs, which leads to higher PPI plasma concentrations in PM individuals (Furuta et al., 2004). The contribution of CYP2C19 to the metabolism of various PPIs differs. For example, in terms of plasma drug concentration-time curves, the ratio of the area under the curve of PMs versus EMs decreases in the following order: omeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, and rabeprazole (Funck-Brentano et al., 1997; Furuta et al., 2004). This is in agreement with the fact that the cure rate of rabeprazole is less dependent on the CYP2C19 genotype compared to other PPIs. Patients with CYP2C19*17 exhibit an enhanced response to clopidogrel with an increased risk of bleeding due to

the higher rate of biotransformation into the active metabolite (Sibbing et al., 2010). In addition, an improved protective effect of clopidogrel after myocardial infarction has been observed in patients carrying the CYP2C19*17 allele (Tiroch et al., 2010). The major enzymes involved in the production of the active metabolite of clopidogrel have been identified as CYP2C19, CYP3A4, and paraoxonase-1 (Clarke and Waskell, 2003; Bouman et al., 2011), although clopidogrel itself is a potent inhibitor of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 (Richter et al., 2004). In general, patients that carry one or two CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles exhibit diminished platelet inhibition after clopidogrel treatment compared to those with the EM genotype (Hulot et al., 2006; Brandt et al., 2007; Mega et al., 2009; Kubica et al., 2011). CYP2C19 PMs may not benefit from clopidogrel and thus alternative drugs, such as prasugrel, should be considered. No definitive recommendations have been established regarding dose adjustment of clopidogrel based on CYP2C19 genotype testing. This may be due to the fact that other downstream genes, such as GPIIb/IIIa receptor genes, and other modulating factors can render a patient more sensitive or more resistant to clopidogrel despite having the same genotype. Larger-scale investigations using genotype-guided clopidogrel therapy compared to other therapy options would reveal the effectiveness of CYP2C19 genotype testing for clopidogrel therapy.

To date, the pharmacogenetic data on CYP2C19 clearly support that genetic variants alter the drug responses of its substrate drug. However, clinical application of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics is limited to certain genotypes, mostly null alleles, and functionally known variants with a minor allele frequency of >5%. Clinical research using common variants only in case and control groups can enhance the statistical power of the evidence for that variant. However, the number of study populations that would benefit from pharmacogenomics research would be greatly reduced if such studies focused on common variants for strong statistical evidence. One goal of pharmacogenomics is to provide personalized medicine to each individual patient and to provide him or her an appropriate dose of the most appropriate drug. Therefore, more diversified investigations or strategies including low-frequency variants are needed to develop a standard practice for human applications. This may be ineffective or unrealistic for personalized medicine if clinical trials wait for the enrollment of a certain number of participants carrying the target genotype to satisfy the statistical power when assessing the role of that particular variant. The biological function of most rare variants remains unknown or has not been investigated in vitro, which has made physicians reluctant to test these individuals in clinical trials. Therefore, more data on functional genomics are needed particularly for rare variants. Although CYP2C19 is a major enzyme for the metabolism of certain drugs and influences their pharmacokinetics, there are many other genes that can modulate or mask the genetic effect of CYP2C19 polymorphisms, including genes involved in pharmacodynamics. Fortunately, recent whole genome sequencing and exome sequencing data have identified numerous variants, and these findings have led to genome-wide association studies using dense genomic markers on chips, resulting in the discovery of new determinants of drug responses. In conclusion, the translation of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics into clinical practice is currently limited to a small number of functional variants, although more than 2,000 variants have already been discovered. More comprehensive and diverse research covering a large number of CYP2C19 variants will lay the foundation for improved personalized medicine in the future.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author thanks Hyuk Choi, MS., Department of pharmacology and pharmacogenomics research center, Inje University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea, for his valuable assistance in computer analysis. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST; No. R13-2007-023-00000-0) and by a grant of the National Project for Personalized Genomic Medicine, Ministry for Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A111218-PG02).

Andersson, T., Regardh, C. G., Lou, Y. C., Zhang, Y., Dahl, M. L., and Bertilsson, L. (1992). Polymorphic hydroxylation of S-mephenytoin and omeprazole metabolism in Caucasian and Chinese subjects. Pharmacogenetics 2, 25–31.

Babalola, C. P., Adejumo, O., Ung, D., Xu, Z., Odetunde, A., Kotila, T., et al. (2010). Cytochrome P450 CYP2C19 genotypes in Nigerian sickle-cell disease patients and normal controls. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 35, 471–477.

Balian, J. D., Sukhova, N., Harris, J. W., Hewett, J., Pickle, L., Goldstein, J. A., et al. (1995). The hydroxylation of omeprazole correlates with S-mephenytoin metabolism: a population study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 57, 662–669.

Benhamou, S., Bouchardy, C., and Dayer, P. (1997). Lung cancer risk in relation to mephenytoin hydroxylation activity. Pharmacogenetics 7, 157–159.

Berge, M., Guillemain, R., Tregouet, D. A., Amrein, C., Boussaud, V., Chevalier, P., et al. (2011). Effect of cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype on voriconazole exposure in cystic fibrosis lung transplant patients. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 67, 253–260.

Bertilsson, L. (1995). Geographical/interracial differences in polymorphic drug oxidation. Current state of knowledge of cytochromes P450 (CYP) 2D6 and 2C19. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 29, 192–209.

Bouman, H. J., Schömig, E., van Werkum, J. W., Velder, J., Hackeng, C. M., Hirschhäuser, C., et al. (2011). Paraoxonase-1 is a major determinant of clopidogrel efficacy. Nat. Med. 17, 110–116.

Brandt, J. T., Close, S. L., Iturria, S. J., Payne, C. D., Farid, N. A., Ernest, C. S. II, et al. (2007). Common polymorphisms of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 affect the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic response to clopidogrel but not prasugrel. J. Thromb. Haemost. 5, 2429–2436.

Bravo-Villalta, H. V., Yamamoto, K., Nakamura, K., Baya, A., Okada, Y., and Horiuchi, R. (2005). Genetic polymorphism of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 in a Bolivian population: an investigative and comparative study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 61, 179–184.

Chen, L., Qin, S., Xie, J., Tang, J., Yang, L., Shen, W., et al. (2008). Genetic polymorphism analysis of CYP2C19 in Chinese Han populations from different geographic areas of mainland China. Pharmacogenomics 9, 691–702.

Clarke, T. A., and Waskell, L. A. (2003). The metabolism of clopidogrel is catalyzed by human cytochrome P450 3A and is inhibited by atorvastatin. Drug Metab. Dispos. 31, 53–59.

de Morais, S. M., Wilkinson, G. R., Blaisdell, J., Meyer, U. A., Nakamura, K., and Goldstein, J. A. (1994a). Identification of a new genetic defect responsible for the polymorphism of (S)-mephenytoin metabolism in Japanese. Mol. Pharmacol. 46, 594–598.

de Morais, S. M., Wilkinson, G. R., Blaisdell, J., Nakamura, K., Meyer, U. A., and Goldstein, J. A. (1994b). The major genetic defect responsible for the polymorphism of S-mephenytoin metabolism in humans. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 15419–15422.

Desta, Z., Zhao, X., Shin, J. G., and Flockhart, D. A. (2002). Clinical significance of the cytochrome P450 2C19 genetic polymorphism. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 41, 913–958.

Ferguson, R. J., De Morais, S. M., Benhamou, S., Bouchardy, C., Blaisdell, J., Ibeanu, G., et al. (1998). A new genetic defect in human CYP2C19: mutation of the initiation codon is responsible for poor metabolism of S-mephenytoin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 284, 356–361.

Funck-Brentano, C., Becquemont, L., Lenevu, A., Roux, A., Jaillon, P., and Beaune, P. (1997). Inhibition by omeprazole of proguanil metabolism: mechanism of the interaction in vitro and prediction of in vivo results from the in vitro experiments. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 280, 730–738.

Furuta, T., Ohashi, K., Kamata, T., Takashima, M., Kosuge, K., Kawasaki, T., et al. (1998). Effect of genetic differences in omeprazole metabolism on cure rates for Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic ulcer. Ann. Intern. Med. 129, 1027–1030.

Furuta, T., Shirai, N., Sugimoto, M., Ohashi, K., and Ishizaki, T. (2004). Pharmacogenomics of proton pump inhibitors. Pharmacogenomics 5, 181–202.

Gaikovitch, E. A., Cascorbi, I., Mrozikiewicz, P. M., Brockmoller, J., Frotschl, R., Kopke, K., et al. (2003). Polymorphisms of drug-metabolizing enzymes CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP1A1, NAT2 and of P-glycoprotein in a Russian population. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 59, 303–312.

Goldstein, J. A. (2001). Clinical relevance of genetic polymorphisms in the human CYP2C subfamily. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52, 349–355.

Goldstein, J. A., Ishizaki, T., Chiba, K., De Morais, S. M., Bell, D., Krahn, P. M., et al. (1997). Frequencies of the defective CYP2C19 alleles responsible for the mephenytoin poor metabolizer phenotype in various Oriental, Caucasian, Saudi Arabian and American black populations. Pharmacogenetics 7, 59–64.

Hamdy, S. I., Hiratsuka, M., Narahara, K., El-Enany, M., Moursi, N., Ahmed, M. S., et al. (2002). Allele and genotype frequencies of polymorphic cytochromes P450 (CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2E1) and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD) in the Egyptian population. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 53, 596–603.

Hashemi-Soteh, S. M., Shahabi-Majd, N., Gholizadeh, A. R., and Shiran, M. R. (2012). Allele and genotype frequencies of CYP2C9 within an Iranian population (Mazandaran). Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 16, 817–821.

Helsby, N. A., Watkins, W. M., Mberu, E., and Ward, S. A. (1991). Inter-individual variation in the metabolic activation of the antimalarial biguanides. Parasitol. Today 7, 120–123.

Hulot, J. S., Bura, A., Villard, E., Azizi, M., Remones, V., Goyenvalle, C., et al. (2006). Cytochrome P450 2C19 loss-of-function polymorphism is a major determinant of clopidogrel responsiveness in healthy subjects. Blood 108, 2244–2247.

Ibeanu, G. C., Blaisdell, J., Ferguson, R. J., Ghanayem, B. I., Brosen, K., Benhamou, S., et al. (1999). A novel transversion in the intron 5 donor splice junction of CYP2C19 and a sequence polymorphism in exon 3 contribute to the poor metabolizer phenotype for the anticonvulsant drug S-mephenytoin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 290, 635–640.

Ibeanu, G. C., Blaisdell, J., Ghanayem, B. I., Beyeler, C., Benhamou, S., Bouchardy, C., et al. (1998a). An additional defective allele, CYP2C19*5, contributes to the S-mephenytoin poor metabolizer phenotype in Caucasians. Pharmacogenetics 8, 129–135.

Ibeanu, G. C., Goldstein, J. A., Meyer, U., Benhamou, S., Bouchardy, C., Dayer, P., et al. (1998b). Identification of new human CYP2C19 alleles (CYP2C19*6 and CYP2C19*2B) in a Caucasian poor metabolizer of mephenytoin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 286, 1490–1495.

Ingelman-Sundberg, M., Sim, S. C., Gomez, A., and Rodriguez-Antona, C. (2007). Influence of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms on drug therapies: pharmacogenetic, pharmacoepigenetic and clinical aspects. Pharmacol. Ther. 116, 496–526.

Jeppesen, U., Gram, L. F., Vistisen, K., Loft, S., Poulsen, H. E., and Brosen, K. (1996). Dose-dependent inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 by citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and paroxetine. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 51, 73–78.

Jose, R., Chandrasekaran, A., Sam, S. S., Gerard, N., Chanolean, S., Abraham, B. K., et al. (2005). CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms: frequencies in the south Indian population. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 19, 101–105.

Jung, F., Richardson, T. H., Raucy, J. L., and Johnson, E. F. (1997). Diazepam metabolism by cDNA-expressed human 2C P450s: identification of P4502C18 and P4502C19 as low K(M) diazepam N-demethylases. Drug Metab. Dispos. 25, 133–139.

Kaneko, A., Lum, J. K., Yaviong, L., Takahashi, N., Ishizaki, T., Bertilsson, L., et al. (1999). High and variable frequencies of CYP2C19 mutations: medical consequences of poor drug metabolism in Vanuatu and other Pacific islands. Pharmacogenetics 9, 581–590.

Kearns, G. L., Leeder, J. S., and Gaedigk, A. (2010). Impact of the CYP2C19*17 allele on the pharmacokinetics of omeprazole and pantoprazole in children: evidence for a differential effect. Drug Metab. Dispos. 38, 894–897.

Kim, K. A., Song, W. K., Kim, K. R., and Park, J. Y. (2010). Assessment of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms in a Korean population using a simultaneous multiplex pyrosequencing method to simultaneously detect the CYP2C19*2, CYP2C19*3, and CYP2C19*17 alleles. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 35, 697–703.

Kubica, A., Kozinski, M., Grzesk, G., Fabiszak, T., Navarese, E. P., and Goch, A. (2011). Genetic determinants of platelet response to clopidogrel. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 32, 459–466.

Kurzawski, M., Gawronska-Szklarz, B., Wrzesniewska, J., Siuda, A., Starzynska, T., and Drozdzik, M. (2006). Effect of CYP2C19*17 gene variant on Helicobacter pylori eradication in peptic ulcer patients. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 62, 877–880.

Lamba, J. K., Dhiman, R. K., and Kohli, K. K. (2000). CYP2C19 genetic mutations in North Indians. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 68, 328–335.

Lee, S. J., Kim, W. Y., Kim, H., Shon, J. H., Lee, S. S., and Shin, J. G. (2009). Identification of new CYP2C19 variants exhibiting decreased enzyme activity in the metabolism of S-mephenytoin and omeprazole. Drug Metab. Dispos. 37, 2262–2269.

Lee, S. S., Lee, S. J., Gwak, J., Jung, H. J., Thi-Le, H., Song, I. S., et al. (2007). Comparisons of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms between Korean and Vietnamese populations. Ther. Drug Monit. 29, 455–459.

Li, X. Q., Andersson, T. B., Ahlstrom, M., and Weidolf, L. (2004). Comparison of inhibitory effects of the proton pump-inhibiting drugs omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole on human cytochrome P450 activities. Drug Metab. Dispos. 32, 821–827.

Luo, H. R., Poland, R. E., Lin, K. M., and Wan, Y. J. (2006). Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 2C19 in Mexican Americans: a cross-ethnic comparative study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 80, 33–40.

Madan, A., Graham, R. A., Carroll, K. M., Mudra, D. R., Burton, L. A., Krueger, L. A., et al. (2003). Effects of prototypical microsomal enzyme inducers on cytochrome P450 expression in cultured human hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 31, 421–431.

Mankowski, D. C. (1999). The role of CYP2C19 in the metabolism of (±) bufuralol, the prototypic substrate of CYP2D6. Drug Metab. Dispos. 27, 1024–1028.

Mega, J. L., Close, S. L., Wiviott, S. D., Shen, L., Hockett, R. D., Brandt, J. T., et al. (2009). Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 354–362.

Mills, D. C., Puri, R., Hu, C. J., Minniti, C., Grana, G., Freedman, M. D., et al. (1992). Clopidogrel inhibits the binding of ADP analogues to the receptor mediating inhibition of platelet adenylate cyclase. Arterioscler. Thromb. 12, 430–436.

Morita, J., Kobayashi, K., Wanibuchi, A., Kimura, M., Irie, S., Ishizaki, T., et al. (2004). A novel single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the CYP2C19 gene in a Japanese subject with lowered capacity of mephobarbital 4′-hydroxylation. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 19, 236–238.

Myrand, S. P., Sekiguchi, K., Man, M. Z., Lin, X., Tzeng, R. Y., Teng, C. H., et al. (2008). Pharmacokinetics/genotype associations for major cytochrome P450 enzymes in native and first- and third-generation Japanese populations: comparison with Korean, Chinese, and Caucasian populations. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 84, 347–361.

Nielsen, K. K., Brosen, K., Hansen, M. G., and Gram, L. F. (1994). Single-dose kinetics of clomipramine: relationship to the sparteine and S-mephenytoin oxidation polymorphisms. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 55, 518–527.

Pedersen, R. S., Brasch-Andersen, C., Sim, S. C., Bergmann, T. K., Halling, J., Petersen, M. S., et al. (2010). Linkage disequilibrium between the CYP2C19*17 allele and wildtype CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 alleles: identification of CYP2C haplotypes in healthy Nordic populations. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 66, 1199–1205.

Qin, X. P., Xie, H. G., Wang, W., He, N., Huang, S. L., Xu, Z. H., et al. (1999). Effect of the gene dosage of CgammaP2C19 on diazepam metabolism in Chinese subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 66, 642–646.

Ramsjö, M., Aklillu, E., Bohman, L., Ingelman-Sundberg, M., Roh, H. K., and Bertilsson, L. (2010). CYP2C19 activity comparison between Swedes and Koreans: effect of genotype, sex, oral contraceptive use, and smoking. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 66, 871–877.

Richter, T., Murdter, T. E., Heinkele, G., Pleiss, J., Tatzel, S., Schwab, M., et al. (2004). Potent mechanism-based inhibition of human CYP2B6 by clopidogrel and ticlopidine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 308, 189–197.

Rudberg, I., Mohebi, B., Hermann, M., Refsum, H., and Molden, E. (2008). Impact of the ultrarapid CYP2C19*17 allele on serum concentration of escitalopram in psychiatric patients. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 83, 322–327.

Scordo, M. G., Aklillu, E., Yasar, U., Dahl, M. L., Spina, E., and Ingelman-Sundberg, M. (2001). Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 2C9 in a Caucasian and a black African population. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52, 447–450.

Sibbing, D., Koch, W., Gebhard, D., Schuster, T., Braun, S., Stegherr, J., et al. (2010). Cytochrome 2C19*17 allelic variant, platelet aggregation, bleeding events, and stent thrombosis in clopidogrel-treated patients with coronary stent placement. Circulation 121, 512–518.

Sim, S. C., Risinger, C., Dahl, M. L., Aklillu, E., Christensen, M., Bertilsson, L., et al. (2006). A common novel CYP2C19 gene variant causes ultrarapid drug metabolism relevant for the drug response to proton pump inhibitors and antidepressants. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 79, 103–113.

Sindrup, S. H., Brosen, K., Hansen, M. G., Aaes-Jorgensen, T., Overo, K. F., and Gram, L. F. (1993). Pharmacokinetics of citalopram in relation to the sparteine and the mephenytoin oxidation polymorphisms. Ther. Drug Monit. 15, 11–17.

Skjelbo, E., Brosen, K., Hallas, J., and Gram, L. F. (1991). The mephenytoin oxidation polymorphism is partially responsible for the N-demethylation of imipramine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 49, 18–23.

Sohn, D. R., Kwon, J. T., Kim, H. K., and Ishizaki, T. (1997). Metabolic disposition of lansoprazole in relation to the S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation phenotype status. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 61, 574–582.

Sugimoto, K., Uno, T., Yamazaki, H., and Tateishi, T. (2008). Limited frequency of the CYP2C19*17 allele and its minor role in a Japanese population. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 65, 437–439.

Tassaneeyakul, W., Mahatthanatrakul, W., Niwatananun, K., Na-Bangchang, K., Tawalee, A., Krikreangsak, N., et al. (2006). CYP2C19 genetic polymorphism in Thai, Burmese and Karen populations. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 21, 286–290.

Tateishi, T., Kumai, T., Watanabe, M., Nakura, H., Tanaka, M., and Kobayashi, S. (1999). Ticlopidine decreases the in vivo activity of CYP2C19 as measured by omeprazole metabolism. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 47, 454–457.

Tiroch, K. A., Sibbing, D., Koch, W., Roosen-Runge, T., Mehilli, J., Schomig, A., et al. (2010). Protective effect of the CYP2C19 *17 polymorphism with increased activation of clopidogrel on cardiovascular events. Am. Heart. J. 160, 506–512.

Wan, J., Xia, H., He, N., Lu, Y. Q., and Zhou, H. H. (1996). The elimination of diazepam in Chinese subjects is dependent on the mephenytoin oxidation phenotype. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 42, 471–474.

Ward, S. A., Helsby, N. A., Skjelbo, E., Brosen, K., Gram, L. F., and Breckenridge, A. M. (1991). The activation of the biguanide antimalarial proguanil co-segregates with the mephenytoin oxidation polymorphism – a panel study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 31, 689–692.

Wilkinson, G. R., Guengerich, F. P., and Branch, R. A. (1989). Genetic polymorphism of S-mephenytoin hydroxylation. Pharmacol. Ther. 43, 53–76.

Xiao, Z. S., Goldstein, J. A., Xie, H. G., Blaisdell, J., Wang, W., Jiang, C. H., et al. (1997). Differences in the incidence of the CYP2C19 polymorphism affecting the S-mephenytoin phenotype in Chinese Han and Bai populations and identification of a new rare CYP2C19 mutant allele. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 281, 604–609.

Xie, H. G., Kim, R. B., Wood, A. J., and Stein, C. M. (2001). Molecular basis of ethnic differences in drug disposition and response. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 41, 815–850.

Yao, C., Kunze, K. L., Trager, W. F., Kharasch, E. D., and Levy, R. H. (2003). Comparison of in vitro and in vivo inhibition potencies of fluvoxamine toward CYP2C19. Drug Metab. Dispos. 31, 565–571.

Keywords: CYP2C19, functional genetics, personalized medicine, SNP, drug

Citation: Lee S-J (2013) Clinical application of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics toward more personalized medicine. Front. Gene. 3:318. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00318

Received: 06 November 2012; Accepted: 20 December 2012;

Published online: 01 February 2013.

Edited by:

Kathrin Klein, Dr. Margarete Fischer-Bosch-Institute of Clinical Pharmacology, GermanyReviewed by:

Miia Turpeinen, University of Oulu, FinlandCopyright: © 2013 Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and subject to any copyright notices concerning any third-party graphics etc.

*Correspondence: Su-Jun Lee, Department of Pharmacology, Pharmacogenomics Research Center, Inje University College of Medicine, Inje University, Gaegum2-dong, Busanjin-gu, Busan 614-735, South Korea. e-mail:MnN1anVuQGluamUuYWMua3I=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.