94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. For. Glob. Change, 06 March 2023

Sec. Pests, Pathogens and Invasions

Volume 6 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2023.1132537

Introduction: The present changes in climate and land use have led to an increase in pest population densities. The oak pinhole borer, Platypus cylindrus, is one of the ambrosia beetles, which are known to infect wood tissue with fungi from their mycangia. These fungi are responsible for cellulose degradation. This species is now responsible for more frequent timber damage throughout Europe. Therefore, it is assumed that there is a high risk of P. cylindrus outbreaks in the future with possible subsequent oak diebacks. We focused on (1) the influence of stump diameter on P. cylindrus attraction and abundance; (2) the trapping efficacy by a specific pheromone and the impact on nontarget arthropods; and (3) interannual changes in trap catches.

Methods: The research was performed from 2015–2017 with a postharvest survey of stumps. We further analyzed the catches of P. cylindrus and of nontarget arthropods on pheromone traps compared to ethanol-baited traps.

Results and discussion: In total, 12,504 adults were trapped during the 3 years of the study. P. cylindrus abundance was positively correlated with stump diameter and interannual changes. The type of compound used for trapping positively affected the trapping efficacy. However, the pheromone type did not have an impact on nontarget beetles. We consider oak stumps to be a reservoir the oak pinhole borer. Therefore, we recommend their debarking or removal, especially in the case of stumps with a larger diameter (over 61 cm).

Forests in temperate Europe are facing the decline or even dieback of tree species with high economic and conservation importance. Oaks (Quercus spp.) are of crucial importance, as they are one of the major components of temperate ecosystems in Europe (Sallé et al., 2014). Recent oak declines and diebacks are the results of complex processes stemming from the interaction of biotic and abiotic factors (Thomas et al., 2002; Andersson et al., 2011; Macháčová et al., 2022). Bark and wood boring insects represent a main factor for this trend. They kill weakened or even healthy trees and thus are a key component in these multifactorial processes (Sallé et al., 2014). In Europe, oak diebacks are associated with insect pests, and the prevailing guilds are defoliators (mainly Lepidoptera) and bark and wood-boring insects (Sousa and Inacio, 2005; Sallé et al., 2014; Galko et al., 2018; Véle and Horák, 2018).

With respect to bark and wood-boring insects, some beetles from the Platypodinae subfamily have been recently associated with oak forest decline. Namely, Platypus quercivorus (Murayama, 1925) damage can be attributed to the Japanese oak wilt caused by Raffaelea quercivora (Kinuura and Kobayashi, 2006; Yamasaki and Sakimoto, 2009); Platypus koryoensis (Wood and Bright, 1992) is associated with the Korean oak wilt disease caused by R. quercus-mongolicae in Korea (Hong et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2009), and P. cylindrus (Fabricius, 1792; Coleoptera; Curculionidae: Platypodinae) is associated with hardwood trees (mainly oaks) in Europe (Henriques et al., 2006; Akbulut et al., 2008).

The distribution area of the oak pinhole borer, P. cylindrus, extends to the Eurasian and North African regions. Adults attack both healthy and weakened trees (Atkinson, 2004). The main host trees are oaks, but oak pinhole borers have been recorded on ash (Fraxinus), beech (Fagus), chestnut (Castanea), elm (Ulmus), plane (Platanus), and wild cherry (Prunus) trees (Henriques et al., 2006; Akbulut et al., 2008; Soulioti et al., 2015). This ambrosia beetle is in symbiotic relationships with many fungal species (Raffaelea spp., Graphium spp. and Ophiostoma spp.). Symbiotic fungi growing on the walls of galleries provide a food source for both larvae and adults. Moreover, they also intervene in the mechanisms of insect establishment by further weakening the host tree (Sousa and Inacio, 2005; Belhoucine et al., 2011b; Inácio et al., 2011; Bellahirech et al., 2014; Soulioti et al., 2015).

The colonization process of P. cylindrus infestation on the same host tree appears to be well-structured on the tree surface with a quasi-systematic vertical gradient suggesting the existence of secondary attraction mechanisms due to aggregation pheromones, which has already been observed for other members of the Platypodinae subfamily (Ytsma, 1986; Sousa and Inacio, 2005). The primary attraction of the genus Platypus has been identified common host tree odors, such as ethanol and terpenes (Shore and McLean, 1983; Catry et al., 2017). No host selection attraction mechanism is known for the oak pinhole borer. However, other members of Platypodinae often emit aggregation pheromones and, in some cases, sex pheromones (Milligan and Ytsma, 1988; Audino et al., 2005; Tokoro et al., 2007). Males detect volatile components resulting from host tree sap fermentation and first construct the gallery system. When the female arrives, she then moves randomly on the surface of the host tree, entering the gallery that was created previously by the male (Baker, 1963). Furthermore, females are more oriented by secondary attractants rather than other signals (Sousa and Inacio, 2005).

The symptoms of infestation by the oak pinhole borer are conspicuous. Trees lose their foliage or their leaves stay dry on the tree during the vegetation period. Circular entry holes with light sawdust appear on the bark of the trunk and branches. In cases of high infestation, the host trees die. Oak pinhole borers have not traditionally been considered pests, but this situation has changed in recent decades. This species is one of the main pests responsible for the observed dieback of Quercus suber L. in the Mediterranean region (Bouhraoua et al., 2002; Belhoucine et al., 2013). Moreover, the population of this borer increases after forest fires (Catry et al., 2017). Oak pinhole borer was formerly regarded as a beetle associated with overmatured oaks and their stumps in Europe. Nevertheless, the borer was also able to immediately attack the fallen oak trees, and the populations rapidly grew. Beetle population densities have remained high due to oaks being weakened (Winter, 1993), and the borer subsequently spread to new areas and attacked healthy trees. This occurs only in cases where the population grows uncontrollably and the amount of host material composed of weakened trees is insufficient for a dynamically changing population (Sousa and Inacio, 2005).

New outbreak areas and more frequent outbreaks have also been recorded recently in Europe and North Africa (Bellahirech et al., 2019). Regarding the situation in recent years and the prognoses for the forthcoming decades (Jentsch et al., 2007; Allen et al., 2010; Seidl and Rammer, 2017) of increasing temperatures and drought periods, it is assumed that the importance of oak ambrosia beetles will increase in the future with a high possibility of diebacks. This is related to the decreased ability of oak trees to regenerate following drought stress due to unsuitable silviculture (e.g., shading by conifers) and after bark and wood boring insect infestations (Sallé et al., 2014; Rodríguez-Calcerrada et al., 2017; Véle and Horák, 2018; Inácio et al., 2022). Knowledge of the biology of oak pinhole borers may help to prevent and reduce further damage caused by this insect pest. For example, more precise recognition of attractants’ efficiency and patterns of flight activity can lead to new approaches for monitoring and control development. Furthermore, there are still no effective management procedures to minimize damage if the population density increases. This paper provides new insight for protection regarding the damage caused by the oak pinhole borer in central Europe. The novelty of this study lies in deepening the information about pest bionomy and habitat preferences. The results can be considered for developing management procedures aimed at addressing future oak diebacks.

Regarding the pest management of the oak pinhole borer, P. cylindrus, in temperate forests, we were interested in three main aims:

1. How is the oak pinhole borer influenced by the diameter of the coarse woody debris left after harvest and by interannual variability? Are there thresholds for the independent variables?

2. Is the trapping efficacy of the oak pinhole borer influenced by the date and a specific pheromone? Is there any attractiveness to nontarget arthropods?

3. Is the increase in abundance of the oak pinhole borer the cause of the higher abundance of nontarget taxa in pheromone-baited traps?

The research was carried out in central Bohemia, Czechia, close to the town of Chlumec nad Cidlinou. The forest area was nearly 1,000 hectares. The altitude ranged from 200 to 260 m a.s.l. The majority of the stands were dominated by oaks, among which the most widely represented species were Quercus robur L. and Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl. The research site was a part of a game reserve where the stands were managed by selective logging.

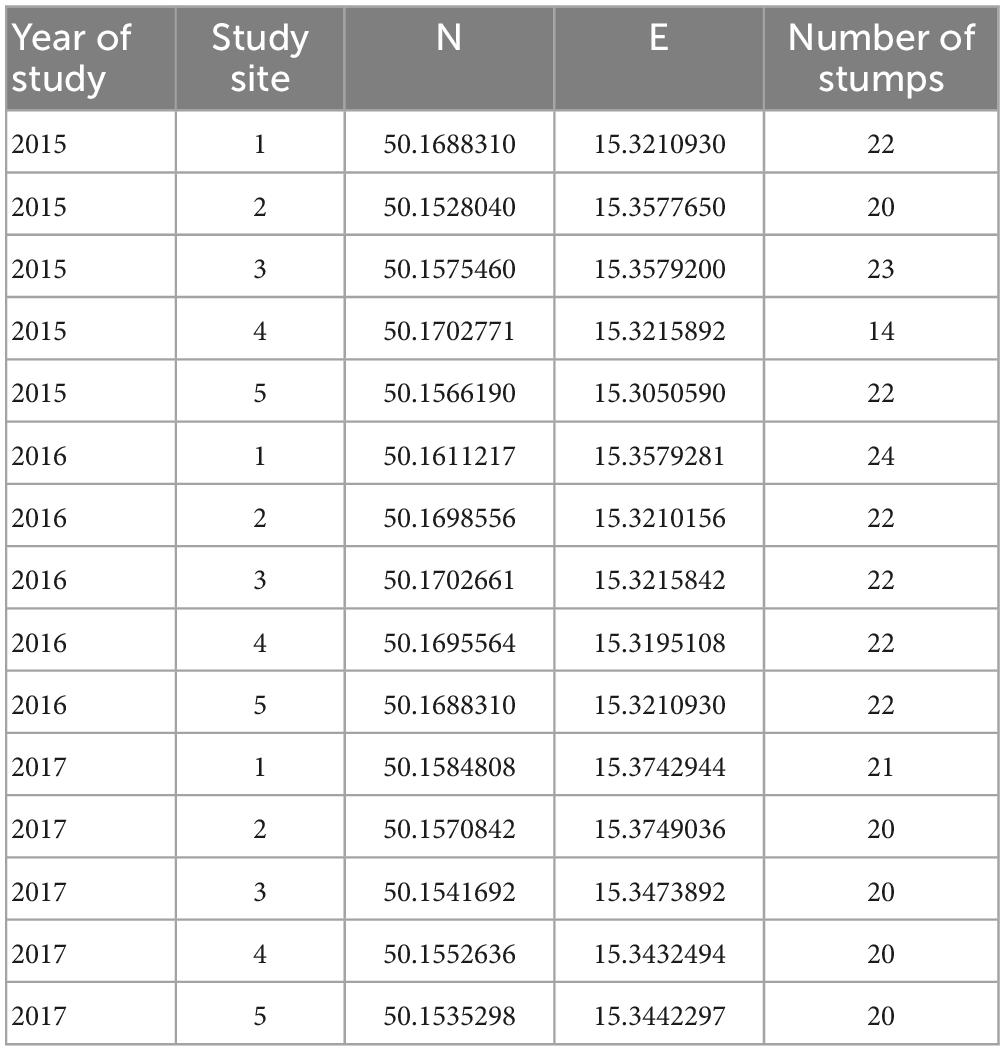

We selected five stands per year during our research from 2015 to 2017 (Table 1). The stands and their surroundings were composed of vital trees. The selected oak stands were harvested during the spring of a particular studied year. All stands consisted of mature oaks (i.e., more than 100 years old), and the proportion of oaks was at least 60%, i.e., oak was the dominant tree species in the stand species composition.

Table 1. Study oak (Quercus) stands during the research on the oak pinhole borer from 2015−2017 in the Czechia.

We conducted research on the stumps that, after tree felling, can contribute to P. cylindrus population build-up in the next season. A postharvesting survey of stumps was performed in each of the study stands after the peak flight activity of P. cylindrus adults in the second half of August.

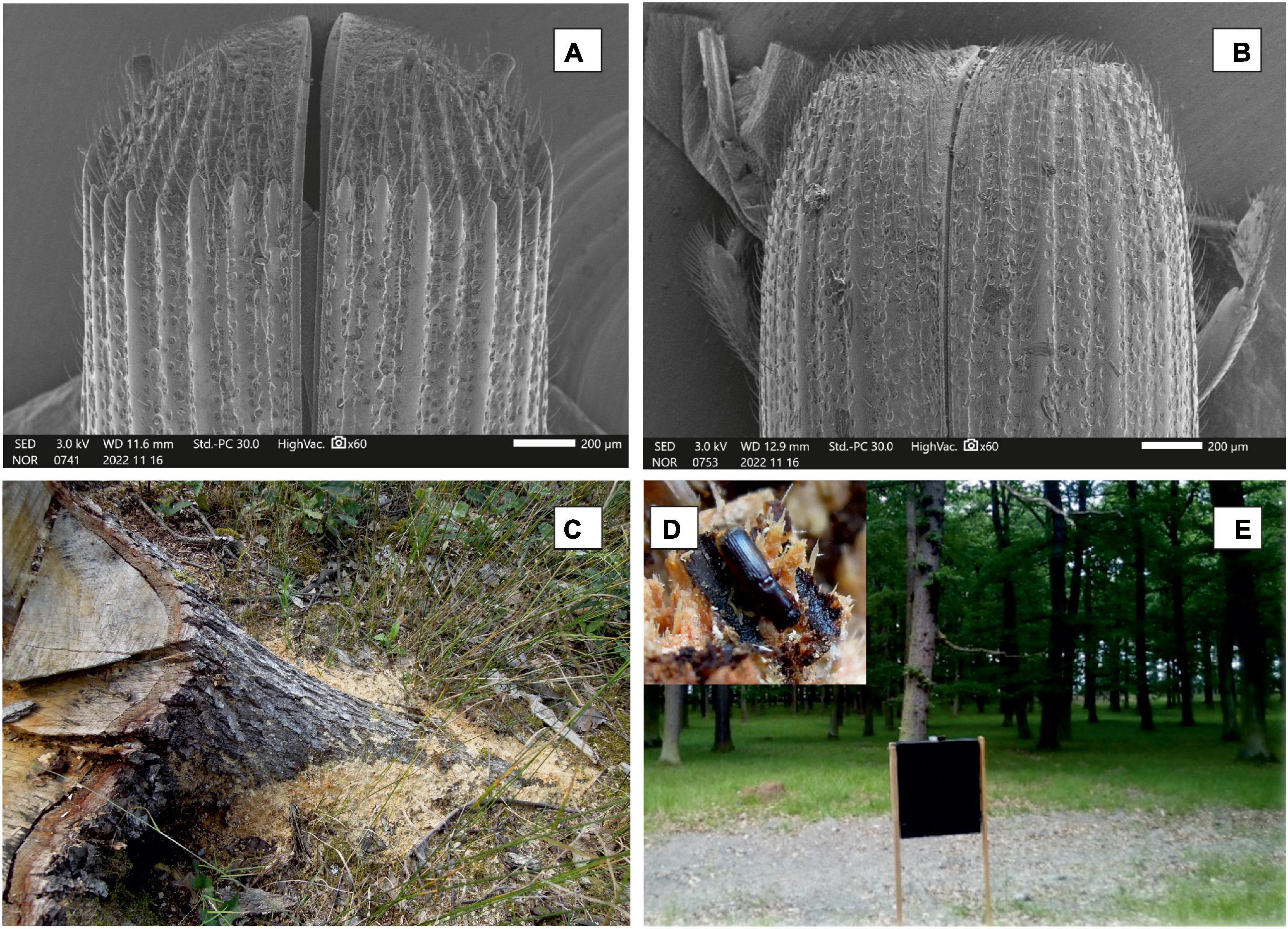

During the assessment, the number of entry holes (variable intensity = number of entry holes per 1 dm2) was counted within two linear transects with a length of 200 meters that included 14 to 24 stumps (Table 1). All stumps in the transect were evaluated, regardless of whether P. cylindrus infestation was detected or not. Each analyzed tree stump was completely debarked with an axe (Figure 1) and the bark area was measured. The determined number of entry holes was converted to a number per reference area of 1 dm2. The diameter (variable diameter) of a particular stump with bark was measured in centimeters.

Figure 1. Male (A) and female (B) declivity in Platypus cylindrus. SEM micrographs were acquired by scanning electron microscopy using a JEOL JSM-IT500HR instrument (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) operating at 3 kV. (C)…dust at base of stump resulting from feeding of the ambrosia beetle P. cylindrus. (D)… P. cylindrus adult beetle in gallery system. (E)…commercial flight barrier traps used in the experiment. Photograph (A,B) by (D). Popelková, (C–E) by K. Resnerová.

Our experiments began at the beginning of June and lasted until the end of August. At the five study sites, commercial flight barrier traps (type Theysohn - Theyson Kunstststoff. GmbH, Germany; black color) were placed 1.5 m above the ground approximately 10 m from the nearest standing oak tree (Figure 1). The sampling of trapped beetles and other arthropods took place regularly every 7-10 days (variable day) during all the years (variable year) of the research.

In 2015, one trap per study site with the pheromone lure Cylindriwit (Witasek Pflanzenschutz GmbH, Austria) was used. Cylindriwit® contained ethanol, (±) 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-ol, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one and 1-hexanol. The Cylindriwit® lures were changed after 10 weeks (as recommended by the manufacturer), and ethanol evaporators were added continuously during monitoring. The insects were stored in a 70% ethanol solution.

In 2016, there were two traps used in the study site. One trap was baited with 96% ethanol in a polyethylene bottle with holes at the top for evaporation, and the second was baited with Cylindriwit®. The traps were approximately 20 m apart. In each sample, nontarget coleopteran species were also counted, but their identity was not determined in more detail.

In 2017, there was installed just one trap for study site again with Cylindriwit® pheromone lure.

In each sample, the number of P. cylindrus specimens was counted, and the sex was determined (based on the outer marks on the abdomen) (Figure 1).

A detailed analysis of the nontarget organisms found in the pheromone traps baited by Cylindriwit® was carried out in the 2017 samples. The nontarget species were classified into taxonomic groups (orders and families).

We used the glmmADMB R package for the computation of the GLMMs (generalized linear mixed-effect models). The models were computed as zero-inflated with a negative binomial distribution of the dependent variables. All the independent variables were first controlled for multicollinearity using the VIF (package HH).

For the first research aim, intensity was the dependent variable, site was used as a random factor, and diameter and year were the fixed factors. For the second aim, the adult males, females, and nontarget taxa trapped were used as dependent variables, day and compound (ethanol or Cylindriwit) were the independent variables, and rank was a random factor. In the third aim, we used all the individuals (variable adults) trapped and then the males and females separately as the dependent variables. The year was used as an independent factor, and the site was a random factor.

A zero-inflated model was not used in the case of the nontarget arthropods. We computed the GLMMs using the abundance of nontarget species as the dependent variable and the number of adults of P. cylindrus as an independent variable with the site as a fixed factor. Only the nontarget taxa with abundances higher than or equal to five individuals were analyzed.

We also used the package party for the threshold computation using the conditional inference tree method (ctree) for the analysis of the first aim (Hothorn et al., 2006), with intensity as the dependent variable and the diameter and year as the independent predictors.

All analyses were performed in R 3.0.2.

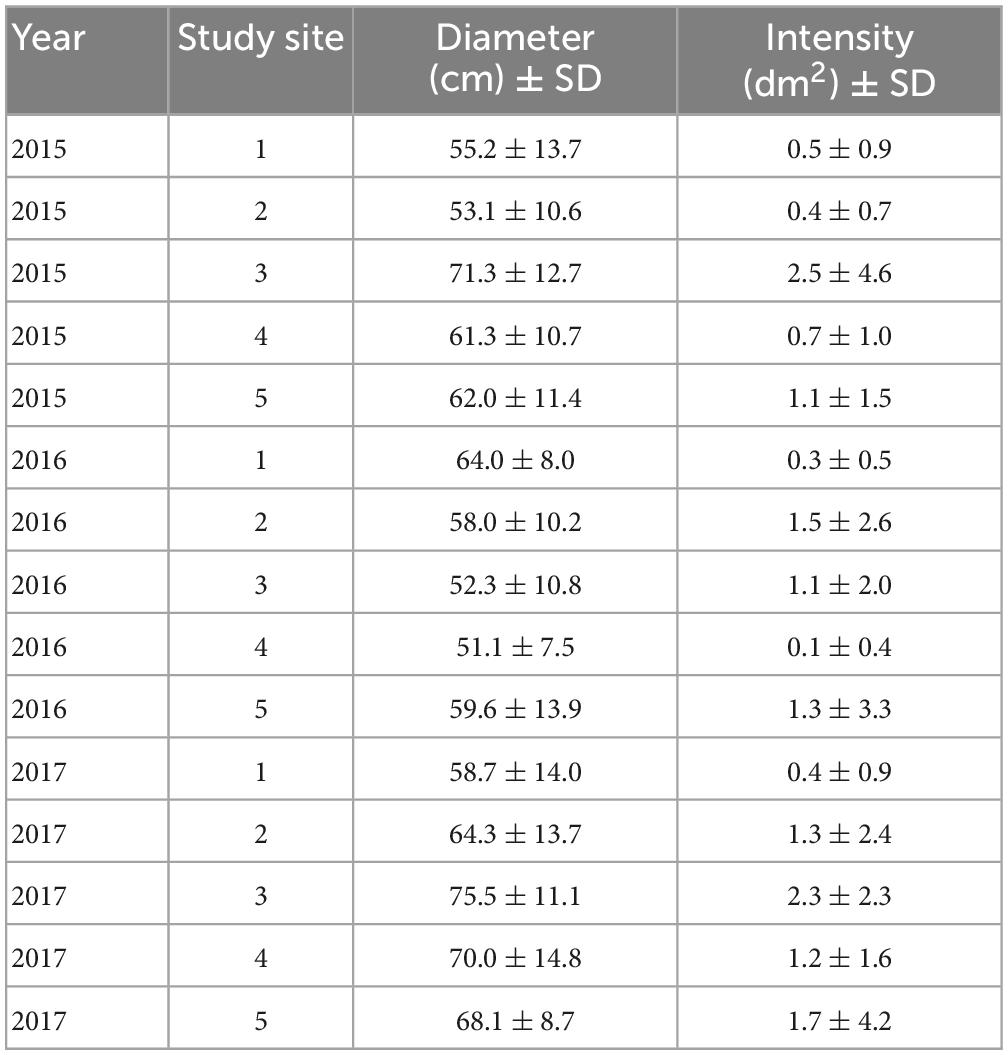

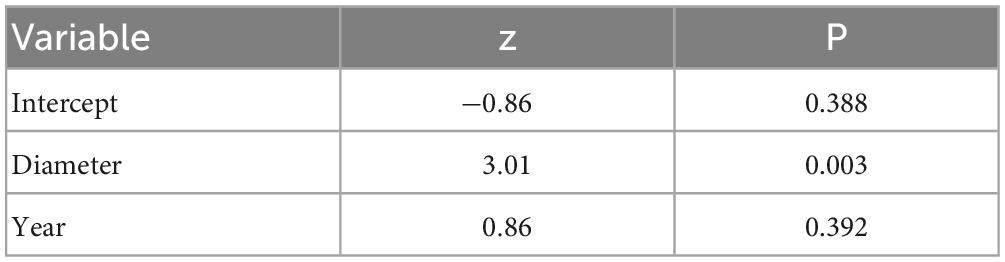

We examined 1,684 oak pinhole borer entry holes in 314 studied stumps. The mean attack intensity was 1.10 entry hole per dm2 from 2015 to 2017 (Table 2). The attack intensity by the oak pinhole borer significantly increased with increasing diameter of the oak stumps (mean = 61.42 ± 13.43 cm, minimum = 33 cm, maximum = 103 cm; Table 2). The year did not influence the attack intensity (Table 3).

Table 2. Overview of the average diameter (cm) of the studied stumps and the average number of entry holes at the study sites during 2015-2017 in the Czechia.

Table 3. Results of the influence of the studied independent variables on the attack intensity of the oak pinhole borer in the Czechia.

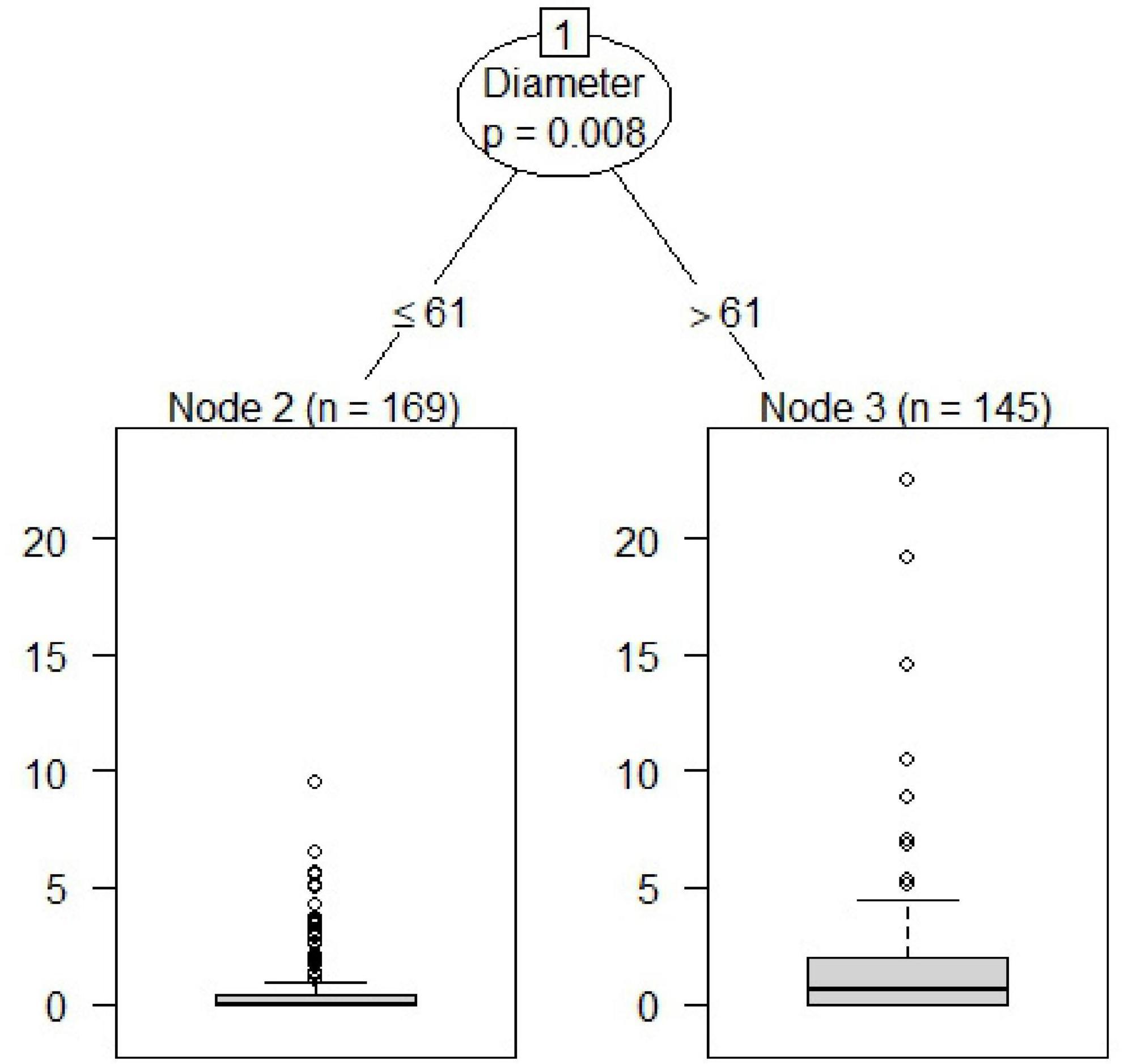

We found a significant threshold (Statistic = 8.29; P = 0.008) for the diameter of the oak stumps regarding the attack intensity by the oak pinhole borer. The threshold was found at a stump diameter of 61 cm (Figure 2). The number of stumps under or equal to this value was 169; the number of stumps above this threshold was 145. The mean value under or equal to this threshold was 0.66 entry holes, and 1.61 holes per dm2 was the mean above this value.

Figure 2. Determination of the attack intensity of the oak pinhole borer by the threshold of oak stump diameter in the Czechia.

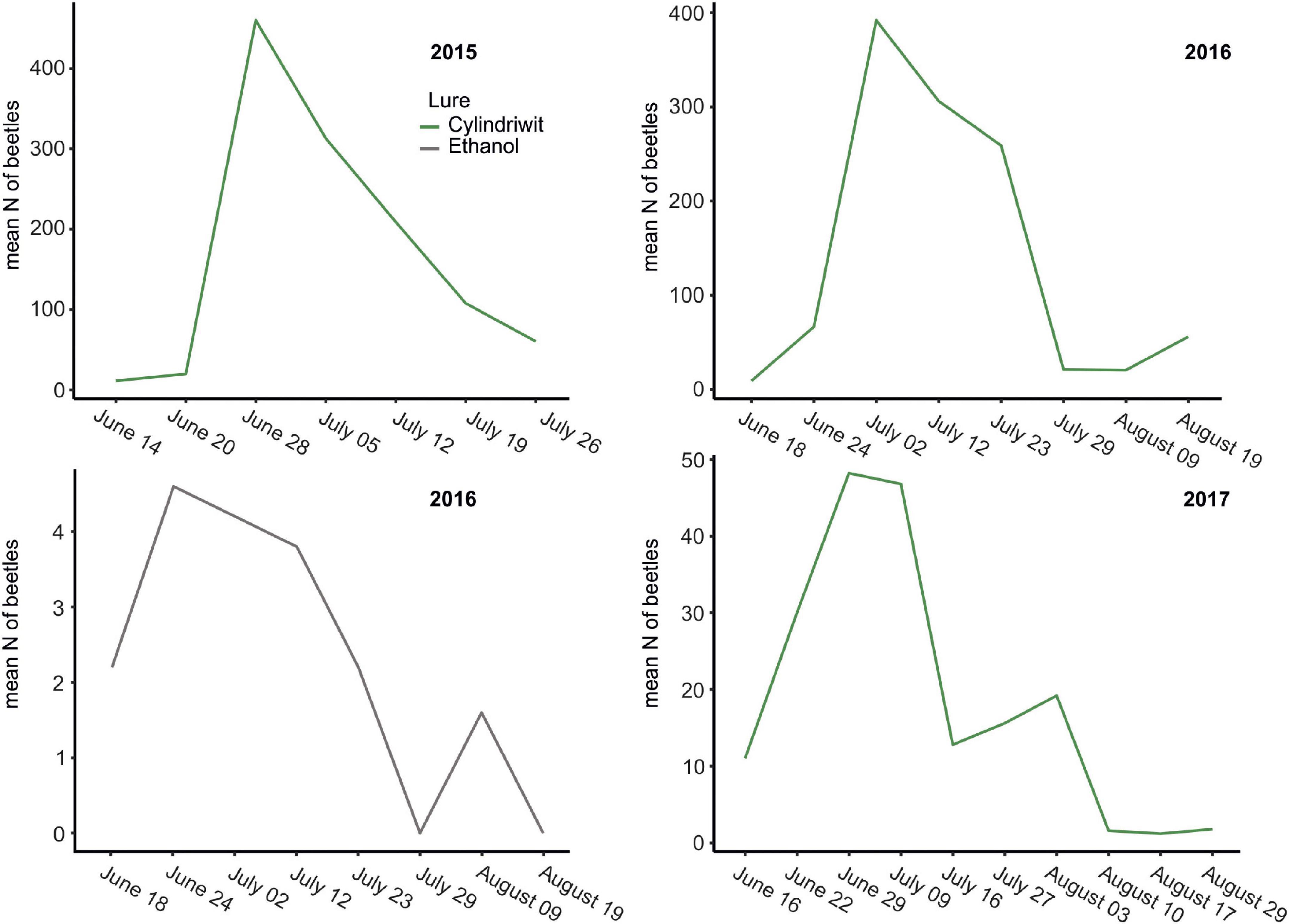

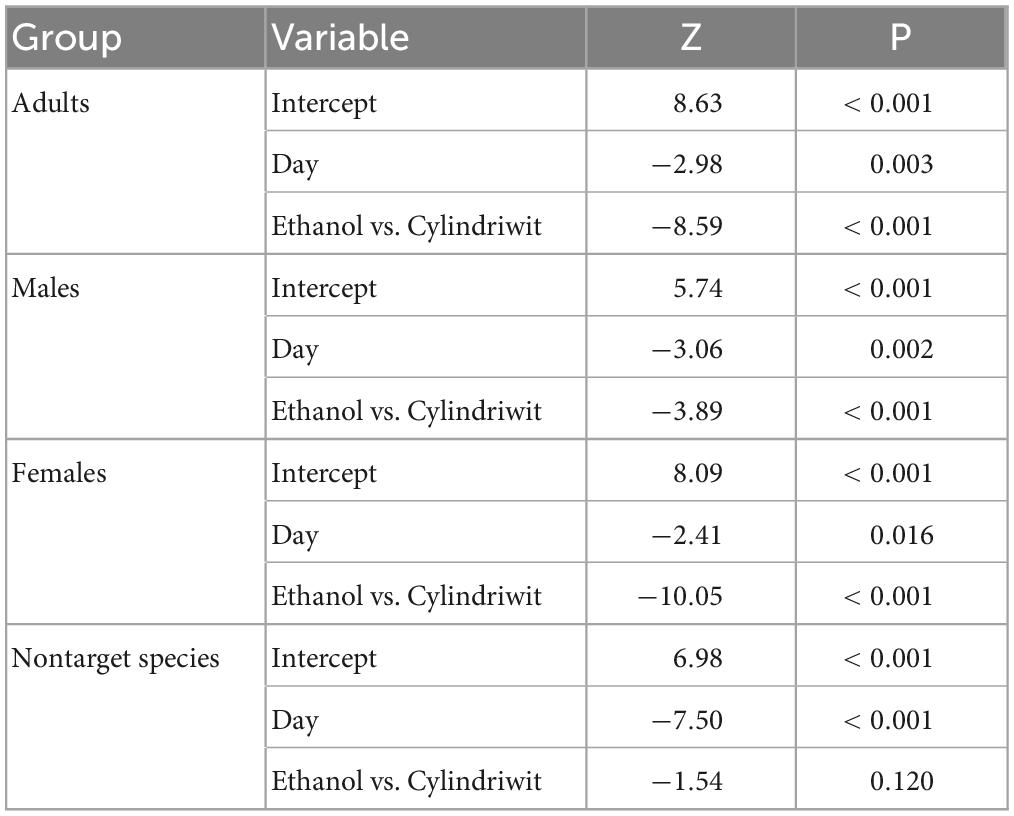

In 2016, we trapped 5,747 oak pinhole borer adults, of which 4,646 were females. We also observed 348 trapped individuals of nontarget beetles, which was 5.7% of the total number of individuals. In total, 160 nontarget beetles in Cylindriwit and 188 in ethanol were observed. The number of trapped adults and nontarget beetles decreased from the beginning of the experiment to the peak flight activity of P. cylindrus. The type of compound used, had a positive impact on the trapping efficacy of the oak pinhole borer males, females, and total individuals. Pheromone traps proved to be more effective than ethanol-baited traps (Figure 3). The type of compound had no significant effect on the nontarget beetles (Table 4). We trapped 12,504 adults, of which 8,999 were females, during the 3 years of the study. We observed a significant difference in trapping success among the three study years (Figure 3). The number of males, females, and adults in total was significantly lower in the last year than in the previous 2 years (Table 5).

Figure 3. The oak pinhole borer catches to lure and ethanol baited traps from 2015 to 2017 in the Czechia. Green line…Cylindriwit baited traps, gray line…ethanol baited traps.

Table 4. Results of the influence of the studied independent variables on the intensity of the trapping of the oak pinhole borer adults, males, females, and nontarget beetles in the Czechia.

Table 5. Results of the trapping success analyses among years using the pheromone of the oak pinhole borer in the Czechia.

We trapped 181 nontarget arthropods in the pheromone-baited oak pinhole borer traps (Table 6). Jewel (Buprestidae) and click (Elateridae) beetles were significantly more abundant in the traps with an increasing number of trapped oak pinhole borers, while other taxa did not demonstrate a significant relationship (Table 6).

Table 6. Results of the association of the nontarget arthropods (in alphabetic order) with the abundance of the oak pinhole borer in the pheromone-baited traps in 2017 in the Czechia.

We found that oak stumps left in stands could be a potential source of P. cylindrus outbreak. The oak pinhole borer was positively influenced by stump diameter with a threshold of 61 cm and that seasonality had no effect. The artificial trapping efficacy was positively driven using pheromones and the early season, but pheromones had no effect on the nontarget beetles. Seasonality is a significant factor in pheromone-baited trap catches. Jewel and click beetles were positively correlated with the abundance of the study species, while other taxa were not.

The key factors involved in oak diebacks are the actual site conditions and management strategies (Führer, 1998; McDowell and Allen, 2015). These factors affect both forest stands and individual trees (Führer, 1998; Thomas et al., 2002). P. cylindrus belongs to species whose abundance coincides with local oak densities. It has been shown that their population densities are highest in mid-size gaps (Bouget and Noblecourt, 2005). The mean intensity of oak pinhole borer attack was 1.1 entry holes per dm2 on the stumps in our study, and the average density of individuals was approximately 55 beetles per dm3 (Belhoucine et al., 2011a).

Host selection by the oak pinhole borer depended primarily on the diameter of the oak stumps. We found a significant increase in ambrosia beetle density with the diameter of the oak stumps. This partly coincides with the spatiotemporal distribution of P. cylindrus, which was not random, indicated by cork oak stands. Nevertheless, there were more factors related to the attacks beside stump dimensions, such as weakness and exploitation (Sousa and Debouzie, 1999). In particular, oak pinhole borer males prefer trees that are already weakened, show discoloration symptoms and have higher diameters (Sousa and Debouzie, 1999). In other research, oak pinhole borer abundance was associated not only with stand and tree characteristics such as dimension, genes and localization (Mattson et al., 1991) but also with debarking and cutting methods in the case of cork oak (Sousa and Inacio, 2005).

Important information regarding commercial losses is that timber with holes caused by P. cylindrus is not destroyed significantly (it is mainly in sapwood), but the appearance of the final products will be spoiled (Tilbury, 2010). To ensure the commercial potential of oak timber, effective management at sites with high abundances of P. cylindrus appears to be shelterwood cutting. This allows for medium sunlight compared to standards (better fructification and growth). At the same time, there will be no intense sunlight on the remaining oak trees and forest floor in the stand, and possible drought stress will not be significant (Schlesinger et al., 1993). Oak stands could also be underplanted with seedlings, including those of other tree species, to make the microclimate of the stand less favorable to wood-boring insects (Thomas et al., 2002; Tilbury, 2010). To prevent damage by the oak pinhole borer, the cutting of oaks with a target diameter of more than 61 cm could be suggested.

Regarding interannual variability, a good management strategy would be to avoid harvesting from June to September, i.e., during the time when the adult beetles are dispersing and colonizing logs. All harvested oak timber should be removed or debarked (including stumps) from forest stands as quickly as possible, mostly before the flight period (Tilbury, 2010).

Even if this strategy is not suitable for mixed stands (Jonsell and Schroeder, 2014; Miklín and Čížek, 2014), in some cases, stump harvesting as a renewable energy source might also be used, especially in places with a strong threat of P. cylindrus outbreaks (dieback occurrence or sanitary or salvage cuttings after wind or fire damage). Nevertheless, this strategy is mainly used in boreal forests and for softwood tree species. One solution can be extracting stumps with the use of wood-chipping, which is sometimes applied in central Europe. This approach limits the mass of deadwood and thus affects the total diversity of the stand. However, it should be avoided in conservation forests and stands with protection status (Miklín and Čížek, 2014).

The flight activity of adults typically begins in May and ends in September in Europe (Sousa and Inacio, 2005). Nevertheless, sporadic emergence of P. cylindrus occurs throughout the whole vegetation season (Baker, 1963; Sousa and Inacio, 2005). In our study; most of the individuals were trapped in June and July. In the Mediterranean region, flying lasts until November (Catry et al., 2017). The main reasons are the life cycle of this cryptic species inside the tree for a long period of time and the high variability in egg laying, which means variability in life stage occurrence. This life strategy leads to a long emergence period (from spring to autumn) and may continue for a second generation during the spring of the following year. Imago activity stops only in winter, before which time males block entry holes of the gallery systems with a mixture of sawdust and secretions (Sousa and Inacio, 2005).

The abundance in the traps was significantly higher with the pheromone lure. This finding may be important for pest management and monitoring. Ethanol also attracted adults, but, consistent with other works, we found the abundance of adults attracted to be low (Markalas and Kalapanida, 2005). Monitoring using pheromone traps is a suitable detection method for estimating the size of a P. cylindrus population, focusing on installation at peak population densities in June and July in Central Europe. We do not recommend monitoring during other time periods outside the peak of flight activity because this method will eliminate nontarget insect species, as in the case of other saproxylic insect species (Lubojacký and Holuša, 2013, 2014).

More than three times more females than males were trapped in the pheromone traps at our study localities. The detected sex ratios were much higher than those previously reported in southern Europe (Catry et al., 2017). These sex ratio differences were most likely due to the different attractiveness to the pheromone compounds for the sexes. The building of galleries is initiated by males, which produce pheromones to attract a female. By producing pheromones, other beetles are attracted, which leads to frequent concurrent attacks (Atkinson, 2004).

P. cylindrus abundance was only related to the occurrence of the beetle families Buprestidae and Elateridae in 2017. One of the most plausible reasons is that jewel beetles (mainly from the genus Agrilus) frequently occur during oak declines and sometimes strongly affect forest stands (Evans et al., 2004; Sallé et al., 2014). Increasing population densities of Agrilus biguttatus (Fabricius, 1776) are often connected with oak declines after defoliations or severe drought events (Moraal and Hilszczanski, 2000; Hilszczański and Sierpinski, 2006). This might explain the correlation in abundance with P. cylindrus, whose abundance also increases due to oak stress (Henriques et al., 2006; Akbulut et al., 2008), and both groups of pests are apparently attracted to similar volatile substances associated with oak declines. Nevertheless, jewel beetles are not frequently found in passive traps; thus, it is hypothesized that they might use the pheromones of the study species as a kairomone. The same situation might be the case for click beetles. However, the most important reason is probably the fact that adult click beetles are very active, frequently collected using window traps (Horák and Rébl, 2013) and sometimes found in conspicuous numbers in oak forest stands (Loskotová and Horák, 2016).

The population density of the oak pinhole borer still may not reach sufficient level to contribute to oak diebacks in central Europe. However, our study indicates that the population density could be very high in oak stumps. A coarse stump diameter is likely the most important attractant for borer attack; the observed presence of the borer in European beech coarse stumps in mountains (i.e., above 600 m a.s.l.) coincides with the above-mentioned results but also indicates two other risks. The first is the possibility of attacks on other commercially important tree species. The second is a shift to high elevations, which is highlighted by its observed long flying period and the habitats it utilizes (wood). Comparable catches of nontarget beetles in traps baited with Cylindriwit and ethanol support the use of pheromone lures for oak pinhole borer monitoring. This result explains the composition of the lure, the main ingredient of which is also ethanol. An insignificant effect on nontarget invertebrates indicates that additional pheromone lure composition attracts target pests but does not affect other groups. This information appears to be important regarding the use of biodiversity-friendly monitoring methods that do not affect other species.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

KR, SŠ, and JHor designed the study concept together. KR provided data from the field study. JHor and SŠ developed the statistical analysis. KR, SŠ, JHor, and JHol wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DP provided scanning electron microscope (SEM) images and graphical corrections. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the grant “Advanced research supporting the forestry and wood-processing sector’s adaptation to global change and the 4th industrial revolution,” no. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000803, which was financed by OP RDE.

We would like to acknowledge the colleagues and students who helped to collect and identify samples during the experiment.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Akbulut, S., Keten, A., and Yuksel, B. (2008). Wood destroying insects in Düzce province. Turk. J. Zool. 32, 343–350.

Allen, C. D., Macalady, A. K., Chenchouni, H., Bachelet, D., McDowell, N., Vennetier, M., et al. (2010). A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 259, 660–684. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001

Andersson, M., Milberg, P., and Bergman, K.-O. (2011). Low pre-death growth rates of oak (Quercus robur L.)—Is oak death a long-term process induced by dry years? Ann. For. Sci. 68, 159–168. doi: 10.1007/s13595-011-0017-y

Atkinson, T. H. (2004). Ambrosia beetles, Platypus spp. (Insecta: Coleoptera: Platypodidae). Gainesville, FL: University of Florida, doi: 10.32473/edis-in331-2004

Audino, P. G., Villaverde, R., Alfaro, R., and Zerba, E. (2005). Identification of volatile emissions from Platypus mutatus (=sulcatus) (Coleoptera: Platypodidae) and their behavioral activity. J. Econ. Entomol. 98, 1506–1509. doi: 10.1093/jee/98.5.1506

Baker, J. M. (1963). “Ambrosia beetles and their fungi, with particular reference to Platypus cylindrus Fab,” in Symbiotic Associations, eds H. Lambers, F. S. Chapin, and T. L. Pons (Cambridge: University Press), 232–265.

Belhoucine, L., Bouhraoua, R. T., Dahane, B., and Pujade, J. (2011a). Aperçu biologique du Platypus cylindrus (Fabricius, 1792) (Coleoptera, Curculionidae: Platypodinae) dans les galeries du bois de chêne-liège (Quercus suber L.). Orsis 25, 105–120.

Belhoucine, L., Bouhraoua, R. T., Meijer, M., Houbraken, J., Harrak, M. J., Samson, R. A., et al. (2011b). Mycobiota associated with Platypus cylindrus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae, Platypodidae) in cork oak stands of North West Algeria, Africa. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 5, 4411–4423. doi: 10.5897/AJMR11.614

Belhoucine, L., Bouhraoua, R. T., Prats, E., and Pulade-Villar, J. (2013). Fine structure and functional comments of mouthparts in Platypus cylindrus (Col. Curculionidae: Platypodinae). Micron 45, 74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2012.10.017

Bellahirech, A., Branco, M., Catry, F. X., Bonifácio, L., Sousa, E., and ben Jamâa, M. L. (2019). Site- and tree-related factors affecting colonization of cork oaks Quercus suber L. by ambrosia beetles in Tunisia. Ann. For. Sci. 76:45. doi: 10.1007/s13595-019-0815-1

Bellahirech, A., Inácio, M. L., Bonifácio, L., Nóbrega, F., Sousa, E., and ben Jamâa, M. L. (2014). Comparison of fungi associated with Platypus cylindrus F. (Coleoptera: Platypodidae) in Tunisian and Portuguese cork oak stands. IOBC/WPRS Bull. 101, 149–156.

Bouget, C., and Noblecourt, T. (2005). Short-term development of ambrosia and bark beetle assemblages following a windstorm in French broadleaved temperate forests. J. Appl. Entomol. 129, 300–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2005.00970.x

Bouhraoua, R., Villemant, C., Khelil, M. A., and Bouchaour, S. (2002). Situation sanitaire de quelques suberaies de l’oust algérien: Impact des xylophages. IOBC/WPRS Bull. 25, 85–92.

Catry, F. X., Branco, M., Sousa, E., Caetano, J., Naves, P., and Nóbrega, F. (2017). Presence and dynamics of ambrosia beetles and other xylophagous insects in a Mediterranean cork oak forest following fire. For. Ecol. Manage. 404, 45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2017.08.029

Evans, H. F., Moraal, L. G., and Pajares, J. A. (2004). “Biology, ecology and economic importance of Buprestidae and Cerambycidae,” in Bark and Wood Boring Insects in Living Trees in Europe, a Synthesis, eds F. Lieutier, K. R. Day, A. Battisti, J.-C. Grégoire, and H. F. Evans (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 447–474. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-2241-8_20

Führer, E. (1998). Oak decline in Central Europe: A synopsis of hypotheses. in Population dynamics, impacts, and integrated management of forest defoliating insects. USDA For. Serv. Gen.Tech. Rep. NE 247, 7–24.

Galko, J., Økland, B., Kimoto, T., Rell, S., Zúbrik, M., Kunca, A., et al. (2018). Testing temperature effects on woodboring beetles associated with oak dieback. Biologia 73, 361–370. doi: 10.2478/s11756-018-0046-1

Henriques, J., de Lurdes Inácio, M., and Sousa, E. (2006). Ambrosia fungi in the insect-fungi symbiosis in relation to cork oak decline. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 23, 185–188. doi: 10.1016/S1130-1406(06)70041-9

Hilszczański, J., and Sierpinski, A. (2006). “Agrilus spp. the main factor of oak decline in Poland,” in Proceedings of the IUFRO Working Party 7.03.10, Gmunden.

Hong, K. J., Kwon, Y.-D., Park, S., and Lyu, D. (2006). Platypus koryoensis (Murayama) (Platypodidae: Coleoptera), the vector of oak wilt disease. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 45, 113–117.

Horák, J., and Rébl, K. (2013). The species richness of click beetles in ancient pasture woodland benefits from a high level of sun exposure. J. Insect. Conserv. 17, 307–318. doi: 10.1007/s10841-012-9511-2

Hothorn, T., Hornik, K., and Zeileis, A. (2006). Unbiased recursive partitioning: A conditional inference framework. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 15, 651–674. doi: 10.1198/106186006X133933

Inácio, M. L., Henriques, J., Guerra-Guimarães, L., Azinheira, H. G., Lima, A., and Sousa, E. (2011). Platypus cylindrus Fab. (Coleoptera: Platypodidae) transports Biscogniauxia mediterranea, agent of cork oak charcoal canker. Bol. San. Veg. Plagas – Dialnet 37, 181–186.

Inácio, M. L., Marcelino, J., Lima, A., Sousa, E., and Nóbrega, F. (2022). Ceratocystiopsis quercina sp. nov. associated with Platypus cylindrus on declining Quercus suber in Portugal. Biology 11:750. doi: 10.3390/biology11050750

Jentsch, A., Kreyling, J., and Beierkuhnlein, C. (2007). A new generation of climate-change experiments: events, not trends. Front. Ecol. Environ. 5:365–374. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2007)5[365:ANGOCE]2.0.CO;2

Jonsell, M., and Schroeder, M. (2014). Proportions of saproxylic beetle populations that utilise clear-cut stumps in a boreal landscape – Biodiversity implications for stump harvest. For. Ecol. Manage. 334, 313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2014.08.042

Kim, K.-H., Choi, Y.-J., Seo, S.-T., and Shin, H.-D. (2009). Raffaelea quercus-mongolicae sp. nov. associated with Platypus koryoensis on oak in Korea. Mycotaxon 110, 189–197. doi: 10.5248/110.189

Kinuura, H., and Kobayashi, M. (2006). Death of Quercus crispula by inoculation with adult Platypus quercivorus (Coleoptera: Platypodidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 41, 123–128. doi: 10.1303/aez.2006.123

Loskotová, T., and Horák, J. (2016). The influence of mature oak stands and spruce plantations on soil-dwelling click beetles in lowland plantation forests. PeerJ 4:e1568. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1568

Lubojacký, J., and Holuša, J. (2013). Comparison of lure-baited insecticide-treated tripod trap logs and lure-baited traps for control of Ips duplicatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J. Pest. Sci. 86, 483–489. doi: 10.1007/s10340-013-0492-z

Lubojacký, J., and Holuša, J. (2014). Effect of insecticide-treated trap logs and lure traps for Ips typographus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) management on nontarget arthropods catching in Norway spruce stands. J. For. Sci. 60, 6–11. doi: 10.17221/62/2013-JFS

Macháčová, M., Nakládal, O., Samek, M., Bat’a, D., Zumr, V., and Pešková, V. (2022). Oak decline caused by biotic and abiotic factors in Central Europe: A case study from the Czech Republic. Forests 13:1223. doi: 10.3390/f13081223

Markalas, S., and Kalapanida, M. (2005). Flight pattern of some Scolytidae attracted to flight barrier traps baited with ethanol in an oak forest in Greece. Anz. Schädlingskd. Pfl Umwelt. 70, 55–57. doi: 10.1007/BF01996922

Mattson, W. J., Haack, R. A., Lawrence, R. K., and Slocum, S. S. (1991). Considering the nutritional ecology of the spruce budworm in its management. For. Ecol. Manage. 39, 183–210. doi: 10.1016/0378-1127(91)90176-V

McDowell, N. G., and Allen, C. D. (2015). Darcy’s law predicts widespread forest mortality under climate warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 669–672. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2641

Miklín, J., and Čížek, L. (2014). Erasing a European biodiversity hot-spot: Open woodlands, veteran trees and mature forests succumb to forestry intensification, succession, and logging in a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. J. Nat. Conserv. 22, 35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2013.08.002

Milligan, R. H., and Ytsma, G. (1988). Pheromone dissemination by male Platypus apicalis White and P. gracilis Broun (Col., Platypodidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 106, 113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.1988.tb00573.x

Moraal, L. G., and Hilszczanski, J. (2000). The oak buprestid beetle, Agrilus biguttatus (F.) (Col., buprestidae), a recent factor in oak decline in Europe. Anz Schädlingskd Pfl Umwelt 73, 134–138. doi: 10.1007/BF02956447

Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J., Sancho-Knapik, D., Martin-StPaul, N. K., Limousin, J.-M., McDowell, N. G., and Gil-Pelegrín, E. (2017). “Drought-induced oak decline—factors involved, physiological dysfunctions, and potential attenuation by forestry practices,” in Oaks Physiological Ecology. Exploring the Functional Diversity of Genus Quercus L, eds E. Gil-Pelegrín, J. J. Peguero-Pina, and D. Sancho-Knapik (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 419–451. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69099-5_13

Sallé, A., Nageleisen, L.-M., and Lieutier, F. (2014). Bark and wood boring insects involved in oak declines in Europe: Current knowledge and future prospects in a context of climate change. For. Ecol. Manage. 328, 79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2014.05.027

Schlesinger, R. C., Sander, I. L., and Davidson, K. R. (1993). Oak regeneration potential increased by shelterwood treatments. North J. Appl. For. 10, 149–153. doi: 10.1093/njaf/10.4.149

Seidl, R., and Rammer, W. (2017). Climate change amplifies the interactions between wind and bark beetle disturbances in forest landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 32, 1485–1498. doi: 10.1007/s10980-016-0396-4

Shore, T. L., and McLean, J. A. (1983). Attraction of Platypus wilsoni Swaine (Coleoptera: Platypodidae) to traps baited with sulcatol, ethanol and a-pinene. Can. For. Serv. Res. Notes 3, 24–25.

Soulioti, N., Tsopelas, P., and Woodward, S. (2015). Platypus cylindrus, a vector of Ceratocystis platani in Platanus orientalis stands in Greece. For. Pathol. 45, 367–372. doi: 10.1111/efp.12176

Sousa, E., and Debouzie, D. (1999). Spatio–temporal distribution of Platypus cylindrus F. (Coleoptera: Platypodidae) attacks in cork oak stands in Portugal. IOBC–WPRS Bull. 22, 47–58.

Sousa, E., and Inacio, M. L. (2005). New aspects of Platypus cylindrus Fab. (Coleoptera: Platypodidae) life history on cork oak stands in Portugal. Entomol. Res. Mediterranean For. Ecosyst. 147–168.

Thomas, F. M., Blank, R., and Hartmann, G. (2002). Abiotic and biotic factors and their interactions as causes of oak decline in Central Europe. For. Pathol. 32, 277–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0329.2002.00291.x

Tilbury, C. (2010). Oak pinhole borer Platypus cylindrus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Farnham: Forest Research.

Tokoro, M., Kobayashi, M., Saito, S., Kinuura, H., Nakashima, T., Shoda-Kagaya, E., et al. (2007). Novel aggregation pheromone, (1S,4R)-p-menth-2-en-1-ol, of the ambrosia beetle, Platypus quercivorus (Coleoptera: Platypodidae). Bull. FFPRI 6, 49–57.

Véle, A., and Horák, J. (2018). The importance of host characteristics and canopy openness for pest management in urban forests. Urban For. Urban Green 36, 84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2018.10.012

Winter, T. (1993). “Dead wood – is it a threat to commercial forestry?,” in Dead wood – is it a threat to commercial forestry?, eds K. Kirby and C. M. Drake (United Kingdom: English Nature Science), 74–80.

Yamasaki, M., and Sakimoto, M. (2009). Predicting oak tree mortality caused by the ambrosia beetle Platypus quercivorus in a cool-temperate forest. J. Appl. Entomol. 133, 673–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2009.01435.x

Keywords: Platypus cylindrus, pheromone-baited traps, Cylindriwit, nontarget arthropods, interannual changes, Quercus

Citation: Resnerová K, Šenfeldová S, Horák J, Popelková D and Holuša J (2023) Colonization of oak stumps by the oak pinhole borer in temperate forests and the efficacy of pheromone traps: Implications for pest management. Front. For. Glob. Change 6:1132537. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2023.1132537

Received: 27 December 2022; Accepted: 21 February 2023;

Published: 06 March 2023.

Edited by:

Manuela Branco, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Edmundo Sousa, Instituto Nacional de Investigação Agrária e Veterinária (INIAV), PortugalCopyright © 2023 Resnerová, Šenfeldová, Horák, Popelková and Holuša. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karolina Resnerová, cmVzbmVyb3Zha0BmbGQuY3p1LmN6

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.