95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. For. Glob. Change , 28 June 2022

Sec. Forest Management

Volume 5 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2022.849920

This article is part of the Research Topic Understanding How Small-Scale Forestry Helps to Achieve UN Sustainable Development Goals View all 4 articles

Sustainable development is one of the ubiquitous paradigms of this century. Poverty, biodiversity loss and climate change are some of the obstacles to achieving sustainable development. To mitigate these encumbrances, countries have painstakingly adopted various policies and interventions. Public work programs, one of the initiatives targeting the construction of strong social safety nets through redistribution of wealth and generation of meaningful employment are increasingly being launched in developing countries. This paper is an attempt to examine the effects of phased implementation of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) on the rejuvenation and restoration of community forests in India. Searches performed in multidisciplinary electronic databases (Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct, PubMed, Emerald Insight, Google Scholar, Taylor and Francis Online, Wiley Online Library, and Springer Link) indicated that MGREGS is one of the largest labor guarantee schemes ever recorded in India and globally, and has holistically contributed to reforestation and afforestation through its land development themes to reduce vulnerability of rural communities to recurrent droughts, floods and improve soil moisture and fertility. It is evident that MGNREGS in synergy with the government forest development programs have the potential to promote social afforestation, reforestation and biodiversity conservation as witnessed in the Sundarbans. These have the potential to empower local people through creation of income generating activities and provision of local forest goods and services. However, the creation of forests as rural assets necessitates that emphasis should be laid on their maintenance so as to ensure that they are given their due importance for sustainable and long-term benefit of the poor rural households. This study highlights the need to perform a comprehensive assessment of forest assets that has been established through MNREGS across states in India.

Sustainable development is one of the ubiquitous paradigms of the 21st century (Costanza et al., 2014; Mensah, 2019; Combet, 2020; UNESCO, 2020). Poverty, biodiversity loss, and climate change are some of the encumbrances to sustainable development (Oyeshola, 2007; IISD, 2012; Roe et al., 2019). Fighting these hindrances in all their dimensions constitute the various targets embedded in the sustainable development goals which aim at achieving a more fruitful integrative paradigm of “sustaincentrism” (UNDP, 2020). Public work programs (PWPs) or public employment programs have a long history and has been popularized worldwide as possible engines for economic recovery and putting an end to crises such as droughts, famine, unemployment, and poverty (McCord, 2008, 2012; Holmes and Jones, 2011; Blattman and Annan, 2016). Carter et al. (2021) defined public work programming as “the provision of state-sponsored employment for the working age poor who are unable to support themselves due to under-productivity, seasonality of rural and urban livelihoods, or the inadequacy of market-based employment opportunities.” McCord (2008) elaborated PWPs as “those activities which entail the payment of a wage (in cash or in kind) by the state, or by an agent acting on behalf of the state, in return for the provision of labour, in order to (i) enhance employment and (ii) produce an asset (either physical or social), with the overall objective of promoting social protection” (p. 1).

Many variants of PWPs exists; however, most PWPs tend to offer either food or cash in return for physical labor and are therefore, respectively, classified as food-for-work (FFW) or cash-for-work (CFW) programs. The choice of an appropriate model (cash, food or other inputs) relies on the conditions upon which the need for the program itself was necessitated (McCord, 2008). Another common variant of PWPs is one in which wages (in the form of food) are harnessed as societal incentives for participation in training programs (food-for-training or FFT) or construction assets (food-for-assets or FFA). PWPs that remits food (not cash wage) have always received support from international agencies such as the World Food Program and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) as these agencies usually have surplus food inventories vis-à-vis capital to support PWPs (McCord, 2008).

There has been an upsurge in PWPs globally (The World Bank, 2009; Subbarao et al., 2013; Bahal, 2022). Representative examples of PWPs reported globally include Program Nasional Pemberdayaan Mandiri (PNPM) in Indonesia (Baker et al., 2013; Global Delivery Initiative, 2015), the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) in Ethiopia (European Union, 2018), Programa de Jefes y Jefas de Hogar Desocupados (Program for Unemployed Male and Female Heads of Households) in Argentina (Galasso and Ravallion, 2004; Kostzer, 2008), the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme in India (Agrawal, 2019),Liberia’s Cash for Work Temporary Employment Project (CfWTEP), the Vision 2020 Umurenge Program in Rwanda (Subbarao et al., 2013; National Institute of Statistics Rwanda, 2021), and the Expanded Public Works Program in South Africa (South African Government, 2021).

It is proven beyond doubts that PWPs can build a strong social safety net through redistribution of wealth and generation of meaningful employment, thereby serving as countercyclical interventions to address both seasonal and short-term unemployment challenges (Grosh et al., 2011; Azam, 2012; Subbarao et al., 2013). PWPs on the whole entail remittance of a wage (in kind as food, cash or voucher) by the state or an agent acting on behalf of the same, in return for the provision of labor, to reduce poverty and vulnerability, produce a (physical or social) asset or service and/or improve employability (Subbarao et al., 2013; Alderman and Yemtsov, 2014; Berhane et al., 2014; McCord and Paul, 2019). Traditionally, PWPs have been adopted as a strategy to tackle poverty, mitigate economic, social, and humanitarian shocks or other country-specific transient circumstances in both middle income and low-income countries (del Ninno et al., 2009; Beierl and Grimm, 2017; Gehrke and Hartwig, 2018; Gilligan, 2020; Carter et al., 2021). Through provision of temporary low-wage employment opportunities to usually unskilled manual laborers, PWPs improves living standards and transfers income to the poor (vulnerable) households in a self-targeted manner while realizing accomplishment of other national initiatives such as reforestation and afforestation, soil conservation, irrigation infrastructure development, road construction and maintenance (Kanaan, 1997; Mackintosh and Blomquist, 2003; Global Delivery Initiative, 2015; European Union, 2018). ıVeritably, labor-intensive PWPs can induce productive investments via income and insurance effects when they are sufficiently reliable and long-term (Gehrke and Hartwig, 2018).

Recently, the role of PWPs has expanded due to globalization and economic integration that seeks to avail opportunities for all as well as function as a fundamental part of the social protection toolkit necessary to address risks and persistent poverty (Zimmermann, 2014; Gehrke and Hartwig, 2018). Thus, innovative dimensions of PWPs have emerged with the sole aim of achieving extra goals. Add-on interventions, such as capital infusion, training and mentoring, and behavioral therapy components are being inculcated into PWPs to improve the quality of labor supply and develop programs into more or less permanent initiatives so as to attain social protection goals, e.g., restoring dignity, reducing child labor and gender inequality (Dejardin, 1996; Holmes and Jones, 2011; Rimki, 2012; Ehmke, 2015; Kumar, 2017; Gehrke and Hartwig, 2018; Dinku, 2019; Mission Directorate, 2021) and maintaining social and political stability, particularly in fragile states (Mvukiyehe, 2018). This new image given to PWPs leaves only a thin commonality between all PWPs−they are all poised to (1) minimize persistent poverty through provision of low-wage employment opportunities for the vulnerable poor and at-risk youths, and (2) create or upgrade (repair) community assets e.g., social and economic infrastructure (The World Bank, 2009; Mvukiyehe, 2018). While PWPs have been beneficial, they also have some drawbacks. For example, they can revolutionize the rural wage market to the benefit of rural workers, which might adversely affect the private sector labor markets (pushes up the cost of agriculture) if the wages offered in PWPs are higher than the wages in local markets (JICA, 2011; Azam, 2012).

Taking a case in point of a developing country like India, the unemployment and out-of-labor force days of agrarian laborers exceed 100 (about 76 days for males and 141 days for females). An estimated 73% of the poor are in rural areas, more than 77% of the country’s total labor force is rural, and 85% of women participating in the labor force are in rural areas (IFAD, 2021). Persistent poverty and unemployment remain as direct outcomes of extensive erosion of natural resources over the past five decades. These are accompanied by natural disasters (floods, hailstorms and whirlwinds, heat waves, prevalence of pests and diseases) have been adversely impacting agricultural activities (Esteves et al., 2013; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2016; Parth, 2019; Amarasinghe et al., 2020; Angom et al., 2021; IFAD, 2021). Increasing poverty and unemployment have triggered other challenges: land fragmentation and an upsurge in the number of agricultural laborers. For instance, the number of agricultural laborers had increased exponentially from 56 million in 1981 to 107 million in 2008. Within almost the same time scale, the percentage of operational land holdings under small and marginal farmers increased from 70% in 1971 to 82% in 2001 (Sharma, 2011). Thus, policy responses to chronic poverty and inequality alike have laid emphasis on inclusive growth whose architecture is precisely defined by setting key areas that requires prioritization through major PWPs. Such PWPs target time-bound delivery of outcomes, including infrastructure, human resource development through basic education, and health and livelihood through skills development, income-generation through a wage employment program (Sharma, 2011; Gehrke and Hartwig, 2018).

The National Employment Guarantee Act 2005 or NREGA is an historic Indian labor legislative and social security measure with the sole objective of guaranteeing the “right to work” as a fundamental one. The act is situated within a rights-based framework and follow demand driven approach, and is self-targeting in its scope (Upendranadh and Tankha, 2009). The program had its origin as fallout of the economic meltdown experienced in the country, though this could not be treated as a unidirectional response to any specific crisis as was the case with most PWPs launched globally. The act was originally intended at poverty alleviation and reducing inequality, i.e., achieving social protection goals (Khera and Nayak, 2009; Sharma, 2011; Mahato and Roy, 2015). However, the scope of the program got expanded later on to reducing migration and creation of rural assets and infrastructure thereby strengthening democracy (Agrawal, 2019).

India is a country comparable to a continent, and therefore its poverty levels can best be addressed as a multi-pronged phenomenon. Thus, the trends, extent, causes, and alleviation of poverty in it is somewhat complex to understand and rather controversial, as it is unevenly spread (The World Bank, 2011). The scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, women (and women-headed households), the elderly and the disabled are the most affected groups (Mehta and Saha, 2001; Borooah et al., 2014; Keerthi, 2014). Nevertheless, many poverty alleviation schemes, such as Rural Landless Employment Guarantee Program (RLEGP,1983–1989), Integrated Rural Development Program (IRDP, 1978–present), Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY, 2000–present), Antyodaya (1977–present), National Rural Employment Program (NREP, 1980–1989), Small Farmer Development Agency (SFDA, 1971–present), Balika Samridhi Yojana (BSY,1997–present), Swarna Jayanti Grameen Swarojgari Yojana (SJGSY, 1999–2011), Rural Women’s Development and Empowerment (RWDE), Sampoorna Grameen Rozgar Yojana (SGRY, 2001–2008; was merged with NREGA), National Food for Work Program (NFFWP, 2004–2005; was subsumed in NREGA), and Rashtriya Mahila Kosh (RMK, 1993–2021) have been launched from time to time after India’s independence on 15th August 1947 (Rimki, 2012; Breitkreuz et al., 2017; Singh and Mann, 2020). Most of these schemes were either closed because they lost relevance or were subsumed in NREGA.

The NREGA, one of the most recent strides in this direction, was passed on 23rd August 2005. It was notified through the Gazette of India (Extraordinary) Notification dated September 7, 2005 as “An Act to provide for the enhancement of livelihood security of the households in rural areas of the country by providing at least one hundred days of guaranteed wage employment in every financial year to every household” (Babu et al., 2014; Godfrey-Wood and Flower, 2017). It was initially launched in 200 backward districts in the first phase on 2nd February 2006 (Sudarshan et al., 2010; Babu et al., 2014) and subsequently expanded to cover 140 more districts by May 15th, 2007. The rest of the Indian districts were automatically included under NREGA with effect from April 1st, 2008 and at present, the scheme is uniformly implemented across the entire 644 districts of rural India (Babu et al., 2014). Approximately 50% of the Drought Prone Areas Program districts were included in this incipient phase, suggesting that the original perception of NREGA was clearly oriented toward climate sensitive (rain-fed) areas as the geography of poverty, and the socio-economically weak groups as the sociology of poverty (Khera and Nayak, 2009; Viswanathan et al., 2014b; Kumar et al., 2021). Originally, the NREGA was to: (a) provide not less than 100 days of unskilled manual work as guaranteed employment in a financial year to every household in rural areas as per demand, resulting in creation of productive assets of prescribed quality, and durability, (b) create sustainable rural livelihoods through regeneration of natural resource base, i.e., augmenting productivity and supporting creation of durable assets, (c) strengthen rural governance (Panchayati Raj institutions) through decentralization and processes of transparency and accountability, and (d) proactively ensuring social inclusion. On October 2nd, 2009 following an amendment, the NREGA 2005 was renamed as Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) honoring the father of the nation, Mahatma Gandhi (Sanjay et al., 2018). On October 2nd, 2009, following an amendment, the NREGA 2005 was renamed as Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) honoring the father of the nation, Mahatma Gandhi (Sanjay et al., 2018).

Thus, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS, hence forth) is one of the largest functional labor guarantee schemes ever recorded in the world (ESID, 2014; Bahal, 2022), which offers 100 days of paid labor in a financial year to every rural household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work (Ministry of Rural Development, 2012; Bhalla, 2014; Gupta and Mukhopadhyay, 2014; Ehmke, 2015; Godfrey-Wood and Flower, 2017; Agrawal, 2019). Later, a directive was issued by Ministry of Rural Development that members of Scheduled Tribe who have received land rights under the Forest Rights Act (2006) should be given extra 50 days of work under the scheme (Business Standard, 2014). In its first phase of implementation (2006–2007) in 200 districts, at least 2.10 crore households got employed, amounting into 90.5 crore person days generated. In 2007–2008, 3.39 crore households were employed, totaling to 143.59 crore person days generated in 330 districts (Rimki, 2012). In 2008–2009, 4.51 crore households were given employment, with 216.32 crore person days generated countrywide. In 2011–2012 financial year, 3.77 crore households were employed, which created 120.88 crore person days of employment (Rimki, 2012). The works permitted under the MGNREGA are categorizable into the following heads (Sanyal, 2017; GOI, 2020).

(a) Watershed related works—such as contour trench, bundh, boulder check, underground dikes, earthen dam, dugout farm ponds, stop dam etc.

(b) Watershed–related works in mountain regions (especially in Spring-shed development).

(c) Agriculture–related works (with emphasis on composting, vermicomposting, and liquid bio-manures).

(d) Livestock–related works (including poultry and goat shelter, construction of pucca floor, urine tank and fodder trough for cattle and Azolla as cattle-feed supplement among others).

(e) Fisheries–related works (especially for exploration of fisheries in seasonal water bodies on public land).

(f) Works in coastal areas–depends upon fish drying yards, belt vegetation and construction of storm water drains for coastal protection (Viswanathan, 2013).

(g) Rural drinking water related works (such as soak pits and recharge pits for point recharge).

(h) Rural sanitation–related works (including introduced individual household latrine, school toilet units, Anganwadi toilet, solid, and liquid waste management).

(i) Food management-related works (for instance deepening and repair of flood channels and Chaur renovation).

(j) Irrigation command–related works (for example unfolding the rehabilitation channels of minors, sub-minors and field channels) (Birhanu et al., 2019).

Indeed, there are limited empirical evidences pointing that PWPs’ such as MGNREGS can generate medium to long-term sustainable extra employment, improve nutrition, afforestation, education outcomes, social, and political stability or asset accumulation (Lieuw-Kie-Song et al., 2011; Dhakane and Mandan, 2014; Blattman and Annan, 2016; Mvukiyehe, 2018; Agrawal, 2019). Also, evidences are lesser as regards the benefits of public infrastructure (community assets) produced by PWPs or of skills developed “through training or on-the-job practice”(Gehrke and Hartwig, 2018). Hence, it is important to critically examine these aspects of PWPs to allow for their improvement (Shah, 2016).

Despite the interest of scholars on the nature and progress of employment generation under MGNREGS, few studies have, in retrospect, analyzed its aim of creating productive, useful and durable public and private assets. A recent study (Lengefeld et al., 2021) examined the livelihood security funding and potential opportunities for ecosystem restoration, with reference to MGNREGS from 2013 to 2021. The authors found that the scheme through its funding flows and projects contributes to ecosystem restoration, indicating that there lies the potential of linking ecosystem restoration with development policies to acquire the necessary funding opportunities. This, would be maximized through capacity building as well as incorporation of environmental indicators and integration of the best ecosystem restoration practices (Lengefeld et al., 2021). This paper makes a critical analysis of the research studies, including papers, evaluation reports and other documents on the MGNREGS, its contribution to the community with a specific focus on forest rejuvenation and restoration across states in India. The paper is presented as follows; (1) background of PWPs (MGNREGS) and their relevance in the context of sustainable development, (2) literature search strategy (methodology), (3) an overview of the success of MGNREGS on forest restoration and rejuvenation in India, (4) gender dynamics in MGNREGS and its contribution to afforestation, and lastly (5) the conclusions and recommendations.

This review followed a non-systematic approach to retrieve and scrutinize peer-reviewed journal articles and reports on National Employment Guarantee Program (MGNREGS) and the associated contribution on the rejuvenation and restoration of forests in India. The reports considered were retrieved electronically from multidisciplinary databases: Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct, PubMed, Emerald Insight, Google Scholar, Taylor and Francis Online, Wiley Online Library and Springer Link. References in the returned results were screened and a further general Google search was done to capture reports and documents from international organizations, regional, national and subnational agencies. The documents obtained were screened using their titles, abstracts and keywords for the key terms and acronyms: “National Employment Guarantee Program,” “Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act,” “Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Scheme,” “Mahatma Gandhi National Employment Guarantee Program,” “National Employment Guarantee Act,” “India,” “forestry,” “afforestation,” “trees,” “reforestation,” “forests,” “plantation,” “agroforestry,” “terracing,” “NREGA,” “MGNREGA,” “NREGS,” and “MGNREGS.” Only relevant reports and articles with information pertaining to the role of MGNREGS and the role of women under the scheme in promotion of forestry, afforestation or reforestation were considered. Only full text reports published in or translated to English and dated until December 2021 were included in the study. In total, the study retrieved 127 reports. After removal of duplicates and assessment for their eligibility, 44 reports met inclusion criteria and were reviewed.

While there is great momentum by India in response to the threats of the decadal climate change, it is evident that the action points are rooted in restoration (species-dependent afforestation works) of the degraded and destroyed ecosystems (Kanwal et al., 2017; Ranjan, 2019; Saxena et al., 2021). These are exemplified by the restoration targets reflected in several flagship programs such as the National Afforestation Program (NAP), Joint Forest Management (JFM) program, the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM), the National Biodiversity Action Plan, and the National Mission for a Green India (GIM) under the National Action Plan on Climate Change (Singh et al., 2020; Bagai and Gergan, 2021).

Amongst other things, the MGNREGA envisaged that activities to be undertaken as part of the program would strengthen natural resource management and address auxiliary causes of chronic poverty like drought, deforestation and soil erosion, thereby insulating the rural poor against climate change impacts and encouraging sustainable development (Bhanumurthy et al., 2014; Narayanan et al., 2014; Bhat and Yadav, 2015). This is because, the scheme itself is not a permanent occupation for poor households, but creation of durable assets could uplift rural economies to levels of prosperity and thrust out the need for minimum-wage employment under MGNREGS (Bhattarai and Viswanathan, 2018). Forest restoration and rejuvenation is one of the objectives of MGRENGA that is nested under land development works (Tiwari et al., 2011; Ministry of Rural Development, 2012; Esteves et al., 2013; Dhakane and Mandan, 2014). As per the guidelines enshrined in the MGNREGA, the following works were allowed in drought proofing category (Dhakane and Mandan, 2014).

(a) Eco-restoration of forests, road/rails, reforestation and tree plantation, canal plantation, block plantation, and avenue plantation.

(b) Afforestation- To cover degraded forest and barren land under afforestation.

(c) Grass land development and production of woody plants combined with pasture (silvipasture).

(d) Watershed development works on watershed approach.

Thus, these activities can be broadly divided into afforestation, reforestation, terracing, agroforestry systems and horticulture development activities. Some of the works relating to MGNREGS forestry are under convergence with other departments that guarantees their implementation in the most efficient manner (Bhanumurthy et al., 2014). This is indicative that collective efforts are being put to support MGNREGS, which itself subsumed various PWPs initially launched in India.

Works relating to afforestation constitutes up to 10% of the total MGNREGS works (Ministry of Rural Development, 2012). A study undertaken in 31 of the 40 study villages of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan states indicated that forest (Neem and Dalbergia) and fruit-bearing (lemon, mango, jackfruit, and guava) tree species had been planted on individual farms and common property resources under MGNREGS (Table 1). Forest trees can be harnessed in the production of fodder, fuel (wood), and other non-timber forest products. The fruit trees yield fruits, flowers and nuts, which is a source of extra income for reducing vulnerability to climatic risks (Tiwari et al., 2011). Similar initiatives have been witnessed in Bihar state where planting of fruit trees such as mangoes, banana, jack fruit and litchis provide livelihood options for farmers under MGNREGS (Gandhi, 2016). Such initiatives standout to encourage the agrarian communities to practice forest restoration without reservations.

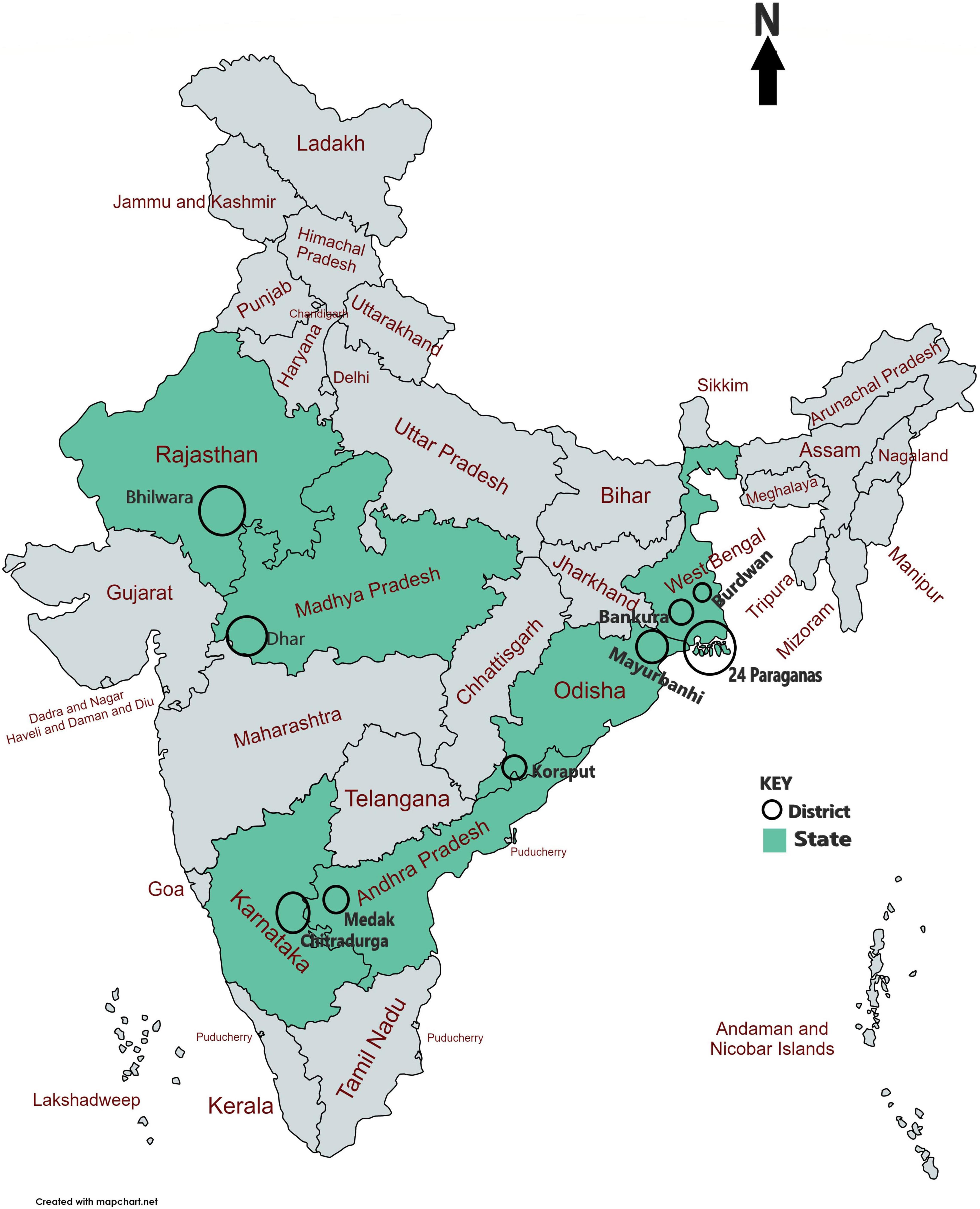

Similarly, horticultural plantations have been raised in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan states which in combination with forest plantations and fruit trees have the potential to confer both regional and global environmental benefits, including biodiversity conservation and carbon sequestration (Tiwari et al., 2011). Of the plantations (afforestation work) implemented in 12 out of 40 villages of the studied states (Table 1 and Figure 1), soil organic content was reported to have improved (increased). For example, a 70–75% increase of the beneficiary plots in Bhilwara district (Rajasthan) and Dhar district (Madhya Pradesh) were recorded (Tiwari et al., 2011).

Figure 1. Map of India showing the location of states where afforestation works under MGNREGS in India. Based on encountered literature.

The “Green Ambaji” project in Banaskantha district of Gujarat covering about sixty hectares of land under the green coverage employed MGNREGS women workers from poor families (Dhakane and Mandan, 2014), which has been instrumental in the restoration of plantation in degraded forestlands and increasing forestry in the district. Due to increased water availability, 60 hectares of forest land was created (TSIRD, 2013). Another project under MGNREGS in conjunction with the Joint Forest Management Committee (JFMC) raises a nursery of multipurpose tree species at Navaras in Banaskantha district which are then transplanted. This plantation initiative led to the creation of 200 hectares of land under forest cover (TSIRD, 2013; Dhakane and Mandan, 2014), exemplifying the potential role of MGNREGS in restoration of forests and other ecosystems in India.

A similar initiative (orchid nursery) was reported in Boko block of Assam state (Bhanumurthy et al., 2014) wherein a convergence partnership with MGNREGS for a cumulative budget of Rs. 2.04 lakhs were drawn. This convergence aimed at land development, institution of bamboo shelves, green house, water sprinklers, orchid blocks and orchids. Published data on the outcomes of this project were, however, not encountered.

A survey report by the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research which surveyed 20 districts in Maharashtra state indicated that MGNREGS works had “replaced scrublands with forests, built earthen structures for impounding water and preventing soil erosion, cleared lands and levelled them to make them cultivable” (Narayanan et al., 2014). Afforestation and horticulture under MGNREGS are being undertaken as a drought prevention and flood-proofing strategy that conserve both the soil and water among agrarian communities of India. Specifically, more than half (52%) of the works in Bhandara district of Maharashtra were related to afforestation. In other districts, such as Jalgaon, Raigad, Thane and Ahmednagar, afforestation assets and works dominated by 26, 6, 5, and 5%, respectively. However, most households did not opine that they had any benefits accruing from afforestation of their farm lands (Narayanan et al., 2014); only a few reported to have benefited from the sale of fruits, medicinal plants (in Gadchiroli district), vegetables or other non-timber forest products. In Gadchiroli’s Kurkheda block specifically, afforestation involved major species of medicinal herbs and plants which are prepared by a local Ayurvedic doctor who distributes them for free as a source of remedy for common ailments. It is therefore reasonable to assert that, some of the benefits from the forests could materialize in the long run if the forests are maintained (Singh et al., 2020). Other convergence interventions in Odisha led to shifting from conventional agricultural crops to high-value crops such as coffee, mangoes, cashew and aromatic plants. In addition to cultivation of commercial horticulture species, this resulted into the development of 1,940 hectares of forest land in Koraput district, fruit trees in 8,226 hectares of land of 12,556 beneficiaries under MGNREGS in Mayurbhanj district (Mishra and Mishra, 2018). Another afforestation initiative in India is the landscape approach to forest restoration which is largely multisectoral in that it takes into account the interests of multiple stakeholders at various levels (Saigal et al., 2016).

In Nainital district of Uttarakhand, MGNREGS along with other forest development programs were reported to have led to increased afforestation, regeneration of forests (reforestation), increased production of forest products, access to forest for income generation and financial support for livelihood improvement (Kanwal et al., 2017).

A social afforestation project of the State Forest Department of Bihardovetailed with the MGNREGS was reported in six participating districts of East and West Champaran, Sitamarhi, Muzaffarpur, Hajipur, and Tirhut range-Vaishali (Down to Earth, 2009). This was a mass plantation drive in which villagers were supported to grow fruit-bearing tree species such as mango, jamun, litchi, guava and gooseberry, trees with supposed medicinal potential (like neem) or those that produce hard wood like teak and mahogany. Out of not less than 200 saplings, farmers were tasked to nurture them for the next 3 years after which annual payments of Rupees 10,200 (for 90% or more survival of the saplings) or Rupees 5,100 if 75% of the saplings survive (Down to Earth, 2009; Gandhi, 2016). Roadside planting of both fruit and wood trees under MGNREGS was also reported in Muzaffarpur district, and the initiative named “Muzaffarpur model on roadside plantations” was visited for possible extension to other locations (GOI, 2012). A similar initiative was reported on 5th July 2021 along Purvanchal expressway in Uttar Pradesh (Shukla, 2021). Such social forestry and flower-bearing tree planting initiative was also undertaken in Kodopal district (Sankrail block) where nurseries and orchard saplings were established (Mishra and Mishra, 2018).

Rural farmers under the MGNREGS convergence with sericulture department of Ramanagar district, Karnataka state were reported to have benefited from 1,460 man-days of employment annually for over 15 years (Dhakane and Mandan, 2014). This initiative was also a source of raw material for the silk industry which on the other hand avails an employment opportunity especially for those involved in silk worm rearing (Viswanathan et al., 2014a).

In another report, restoration of the forest protecting the remote habitats of the Sundarbans of West Bengal was reported to be due to the impact of the construction of farm ponds, renovation of earthen dams and structuring of river embankment under the convergence efforts of MGNREGS and forestry department (TSIRD, 2013). The Sundarbans is one of the important heritage sites housing globally endangered or rare animal species including the Indian python, the Ganges and Irawadi dolphins, olive ridley turtles, Royal Bengal tiger, estuarine crocodiles, critically endangered endemic river terrapin (Batagur baska) as well as the world’s only salt-tolerant mangrove forest harboring species of Panthera tigris tigris tigers (WWF, 2011; UNESCO, 2021). For this, plantation of more than a crore of mangrove seedlings in up to 2,485 hectares was registered in 24 Parganas of West Bengal. Further, restoration of the ecological lifelines of river embankments and earthen dams with mangrove plantation were also done, with planting of mangoes and other fruit trees in Bankura district of West Bengal (Mishra and Mishra, 2018). This highlights that such restoration initiatives can foster eco-tourism industry in India (Lengefeld et al., 2021). Other than the cited forest restoration reports, conservation terracing was another activity under MGNREGS (Tiwari et al., 2011).

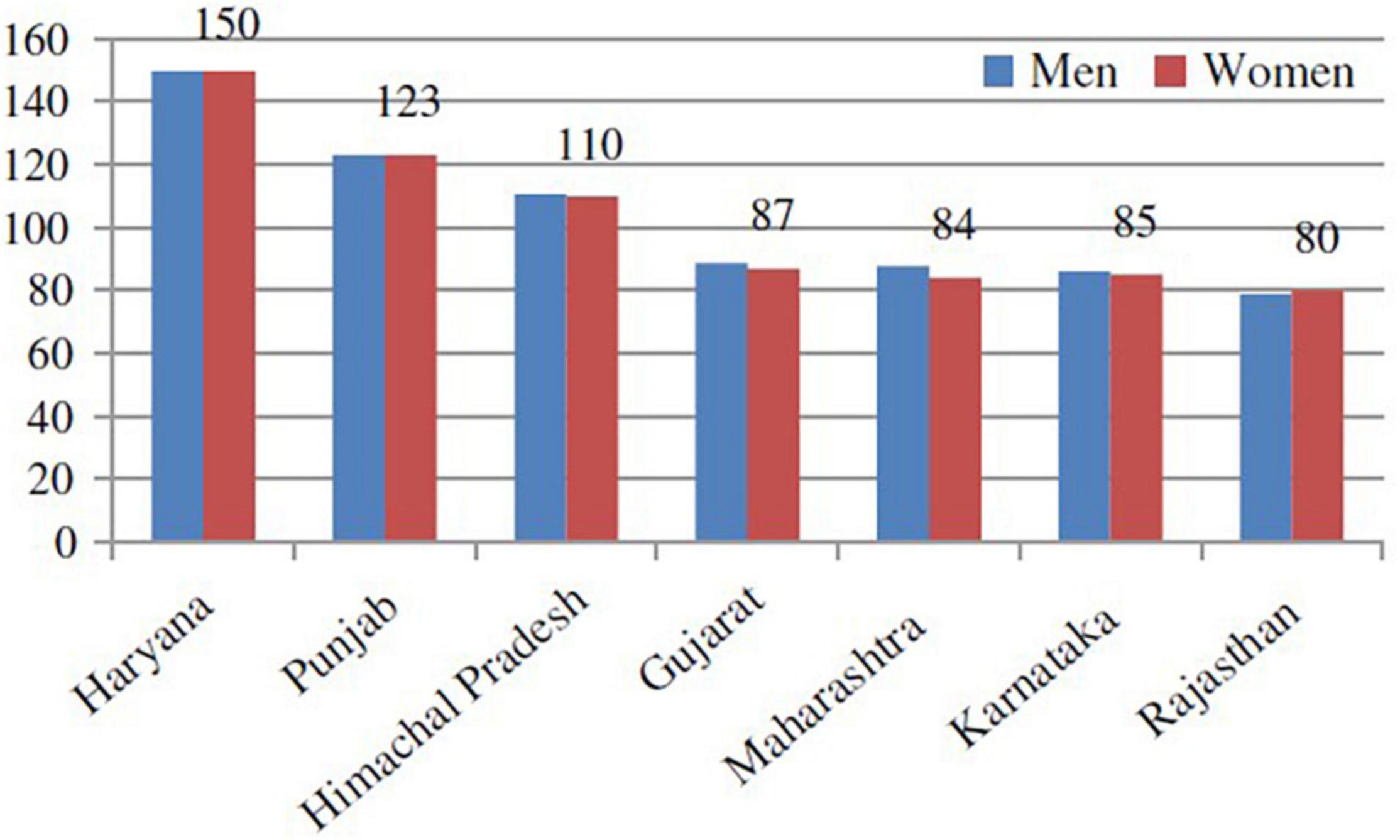

The MGNREGA provide safeguards and prioritizes the interests of the deprived, marginalized and vulnerable Indian population (H.P. State Institute of Rural Development, 2017). MGNREGA vividly gives room for women equity (gender quota dictating) in both access to work and in the payment of wages (Pankaj and Tankha, 2010; Girard, 2014; Figure 2). Thus, the scheme gives room for women to take one-third share in the stock of employment if they demand. Interestingly, women were reported to make up more than half of the population in MGNREGS in some Indian states (Panda et al., 2009; Sudarshan et al., 2010; Holmes et al., 2011; Stahlberg, 2012; Ahangar, 2014; Kartika, 2015; H.P. State Institute of Rural Development, 2017). Proportion of women in MGNREGS in the financial year 2009–2010 and 2010–2011 at the national level were reported to be 48% (Sharma, 2015). In Kerala and Tamil Nadu, over 90% of the workers were reported to be women (Peedikakandi et al., 2015; Arya et al., 2017; Breitkreuz et al., 2017; Mahapatra, 2021). A more recent finding indicates that 55% of MNREGS beneficiaries who were allocated 2.35-billion-person days of work in 2015/2016 consisted of women, mostly of the scheduled castes (dalits), scheduled tribes (adivasi) or those hailing from other vulnerable sections such as other backward classes and the landless (Bhattarai and Viswanathan, 2018). These data attests to some extent that the “self-targeting social safety net program” has had long-term implications in poverty alleviation and correcting gender skewness and discriminatory wages prevalent in the rural labor markets of India (Pankaj and Tankha, 2010; Ahangar, 2014; Carswell and De Neve, 2014; Ravindar, 2016; Basavaraj and Nagaraja, 2017; Jose and Radhakrishnan, 2018; Mahapatra, 2021; Nagaraja, 2021).

Figure 2. Wage rate obtained under MGNREGA (in Indian Rupees) across some selected Indian states. Adopted from Kumar (2018).

The act also indicates that child care facilities should be availed at the workstations, in addition to ensuring that work for women are done as close as possible to the participant’s homes. Unlike in other poverty-alleviation schemes, women in MGNREGS have access to equal wages as men which is a major incentive for women (Rimki, 2012). In other words, MGNREGS’ potential to empower Indian women through provision of employment opportunities has been a subject of discussion by previous researchers (Drèze and Oldiges, 2007, 2009; Pankaj and Tankha, 2010).

However, the uptake of MGNREGS work by women is an expected trend. This is because women tend to be paid lower wages in the casual labor market than they might be earning from MGNREGS. For instance, Sudarshan et al. (2010) reported that wages paid by MGNREGS was 125 Indian rupees which is higher than 70–80 Indian rupees for agrarian manual labor in the private sector. Some researchers argue that MGNREGA, through improving women’s wages, has broadened consumption options for women and enhanced their economic independence (Pankaj and Tankha, 2010). This gender dynamism in MGNREGS as witnessed in various reports point to notion that upscaling the program can be harnessed for gender mainstreaming in the country.

Direct participation of women in MGNREGS has had an impact on forest rejuvenation and restoration in India. For example, in West Bengal, involvement of women drawn from local Self Help Groups were reported to have been instrumental in the rearing of mangrove sap (Mishra and Mishra, 2018). Other than the foregoing, there is paucity of published literature on the direct role of women under MGNREGS in forest restoration and rejuvenation of India. This can partly be explained by the asymmetrical inheritance of resources such as land and water by women which may limit them from participating in community tree planting programs currently being launched under MNREGS-convergence initiatives in India.

India’s MGNREGS is an epitome of a rights-based scheme integrating employment promotion and income security for rural populations in an entirely innovative way. Drawing on the experiences with similar PWPs with regional geographical scope, MGNREGS is a bold intervention to empower vulnerable rural population with a basic source of income and social security through 100 days of guaranteed employment per eligible household. The results of this study indicate that MGNREGS has and will continue to contribute immensely to reforestation and afforestation through its land development objectives to reduce vulnerability of local agrarian communities to recurrent droughts, floods and to conserve soil moisture and fertility. It is well marked that MGNREGS in convergence with other government forest development programs have the potential to promote afforestation and reforestation in Indian states as these have the potential to empower local people through income generating activities. However, the creation of forests as rural assets should be rolled out along with emphasis on their maintenance so as to ensure that they are given their due importance for sustainable and long-term benefit of the poor rural households. The study evinces the need to assess the status of village forest ecosystems, especially forest production systems that has been established through MNREGS. It is also important to integrate MGNREGS with the joint forest management interventions across states in India, by which, the reforestation and forest rejuvenation activities can be effectively implemented with potentially higher success. The role played by women under MNREGS in forest restoration of India is a theme that warrant more comprehensive future studies.

JA assembled the datasets and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. PV contributed to reading and editing of the manuscript. Both authors approved the final manuscript submitted.

This project has been funded by the E4LIFE International Fellowship Program offered by Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham and JA also extend her gratitude to the Live-in-Labs Academic program for the support offered.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Agrawal, G. (2019). Mahatma Gandhi national rural employment guarantee act: design failure, implementation failure or both? Manag. Labour Stud. 44, 349–368. doi: 10.1177/0258042x19871406

Ahangar, G. B. (2014). Women empowerment through MGNREGA: a case study of block Shahabad of district Anantnag, Jammu and Kashmir. Abhinav Natl. Month. Refereed J. Res. Commer. Manag. 3, 55–62.

Alderman, H., and Yemtsov, R. (2014). How can safety nets contribute to economic growth? World Bank Econ. Rev. 28, 1–20. doi: 10.1093/wber/lht011

Amarasinghe, U., Amarnath, G., Alahacoon, N., and Ghosh, S. (2020). How do floods and drought impact economic growth and human development at the sub-national level in India? Climate 8:123. doi: 10.3390/cli8110123

Angom, J., Viswanathan, P. K., and Ramesh, M. V. (2021). The dynamics of climate change adaptation in India: a review of climate smart agricultural practices among smallholder farmers in Aravalli district, Gujarat, India. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 3:100039. doi: 10.1016/j.crsust.2021.100039

Arya, A. P., Meghana, S., and Ambily, A. S. (2017). Study on Mahatma Gandhi national rural employment guarantee act (MGNREGA) and women empowerment with reference to Kerala. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst. 9, 74–82.

Azam, M. (2012). The Impact of Indian Job Guarantee Scheme on Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from a Natural Experiment. IZA Discussion Paper No. 6548. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

Babu, V., Kanth, G., Dheeraja, C., and Rangachryulu, S. (2014). The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). Frequently asked Questions on MGNREGA Operational Guidelines-2013. Available online at: https://nrega.nic.in/Circular_Archive/archive/nrega_doc_FAQs.pdf (accessed August 10, 2021).

Bagai, A., and Gergan, R. (2021). India Holds Great Promise in this Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. Available online at: https://india.mongabay.com/2021/06/commentary-india-holds-great-promise-in-this-decade-on-ecosystem-restoration/ (accessed June 20, 2021).

Bahal, G. (2022). A tale of two programs: assessing treatment and control in NREGA studies. World Bank Econ. Rev. 36, 514–532. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhab019

Baker, J. L., Burger, N., Glick, P., Perez-Arce, F., Rabinovich, L., Yoong, J., et al. (2013). Indonesia – Evaluation of the Urban Community Driven Development Program : Program Nasional Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Mandiri Perkotaan (PNPM-Urban) (English). Indonesia Policy Note. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Bandyopadhyay, N., Bhuiyan, C., and Saha, A. K. (2016). Heat waves, temperature extremes and their impacts on monsoon rainfall and meteorological drought in Gujarat, India. Nat. Hazard. 82, 367–388. doi: 10.1007/s11069-016-2205-4

Basavaraj, S. B., and Nagaraja, J. (2017). Women empowerment through Mahathma Gandhi national rural employment guarantees act (Mgnrega): in Ballari Disrict Karnataka State. IOSR J. Human. Soc. Sci. 22, 26–30.

Beierl, S., and Grimm, M. (2017). Do Public Works Programmes Work? A Systematic Review of the Evidence in Africa and the MENA Region. Passau: University of Passau.

Berhane, G., Gilligan, D. O., Hoddinott, J., Kumar, N., and Taffesse, A. S. (2014). Can social protection work in Africa? The impact of Ethiopia’s productive safety net programme. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 63, 1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.001

Bhalla, S. S. (2014). No Proof Required: Move From NREGA to Cash Transfers. Noida: The Indian Express.

Bhanumurthy, N. R., Amar Nath, H. K., Verma, A., and Gupta, A. (2014). Unspent Balances and Fund Flow Mechanism under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS. New Delhi: National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

Bhat, J. A., and Yadav, P. (2015). MG-NREGA: – a pathway for achieving sustainable development. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. Appl. Sci. 3, 339–347.

Bhattarai, M., and Viswanathan, P. K. (2018). “Introduction,” in Employment Guarantee Programme and Dynamics of Rural Transformation in India. India Studies in Business and Economics, eds M. Bhattarai, P. K. Viswanathan, R. Mishra, and C. Bantilan (Singapore: Springer).

Birhanu, A., Murlidhar Pingale, S., Soundharajan, B. S., and Singh, P. (2019). GIS-based surface irrigation potential assessment for Ethiopian river basin. Irrig. Drain. 68, 607–616. doi: 10.1002/ird.2346

Blattman, C., and Annan, J. (2016). Can employment reduce lawlessness and rebellion? A field experiment with high-risk men in a fragile state. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 110, 1–17. doi: 10.1017/s0003055415000520

Borooah, V. K., Diwakar, D., Mishra, V. K., Naik, A. K., and Sabharwal, N. S. (2014). Caste, inequality, and poverty in India: a re-assessment. Dev. Stud. Res. 1, 279–294. doi: 10.1080/21665095.2014.967877

Breitkreuz, R., Stanton, C.-J., Brady, N., Pattison-Williams, J., King, E. D., Mishra, C., et al. (2017). The Mahatma Gandhi national rural employment guarantee scheme: a policy solution to rural poverty in India? Dev. Policy Rev. 35, 397–417. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12220

Business Standard (2014). Centre Issues Directive for 150 Days Work Under MGNREGA for STs in Forest Areas. Chennai: Business Standard.

Carswell, G., and De Neve, G. (2014). MGNREGA in Tamil Nadu: a story of success and transformation? J. Agrar. Chang. 14, 564–585. doi: 10.1111/joac.12054

Carter, B., Roelen, K., Enfield, S., and Avis, W. (2021). Public Works Programmes. Available online at: https://gsdrc.org/topic-guides/social-protection/global-issues-and-debates-2/public-works-programmes/ (accessed December 2, 2021).

Combet, E. (2020). Planning and sustainable development in the twenty-first century. Facts Energy Environ. Econ. 1, 473–506. doi: 10.4000/oeconomia.9558

Costanza, R., McGlade, J., Lovins, H., and Kubiszewski, I. (2014). An overarching goal for the UN sustainable development goals. Solutions 5, 13–16.

Dejardin, A. K. (1996). Public Works Programmes, A Strategy for Poverty Alleviation: The Gender Dimension. Issues in development, Discussion Paper 10. Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_123436.pdf (accessed June 9, 2021).

del Ninno, C., Subbarao, K., and Milazzo, A. (2009). How to Make Public Works Work : A Review of the Experiences. Social Safety Nets Primer Notes; No. 31. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Dhakane, M. U., and Mandan, J. K. (2014). Afforestation bustle through MGNREGA: a pace towards the sustainable approach. Int. J. For. Crop Improv. 5, 90–93. doi: 10.15740/has/ijfci/5.2/90-93

Dinku, Y. (2019). The impact of public works programme on child labour in Ethiopia. South Afr. J. Econ. 87, 283–301. doi: 10.1111/saje.12226

Down to Earth (2009). Money Growth Policy of Bihar. Social Forestry Projects links Rural Employment with Growing Saplings. New Delhi: Down to Earth.

Ehmke, E. (2015). National Experiences in Building Social Protection Floors: India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme/Ellen Ehmke; International Labour Office, Social Protection Department. Geneva: ILO.

ESID (2014). Success and Failure in MGNREGA Implementation in India. ESID Briefing No. 1. Available online at: https://www.effective-states.org/wp-content/uploads/briefing_papers/final-pdfs/esid_bp_1_NREGA.pdf (accessed August 10, 2021).

Esteves, T., Rao, K. V., Sinha, B., Roy, S. S., Rao, B., Jha, S., et al. (2013). Agricultural and livelihood vulnerability reduction through the MGNREGA. Econ. Polit. Week. 48, 94–103.

Galasso, E., and Ravallion, M. (2004). Social protection in a crisis: Argentina’s plan Jefes y Jefas. World Bank Econ. Rev. 18, 367–399. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhh044

Gehrke, E., and Hartwig, R. (2018). Productive effects of public works programs: What do we know? What should we know?. World Dev. 107, 111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.031

Gilligan, D. (2020). Social Safety Nets are Crucial to the COVID-19 Response. Some Lessons to Boost Their Effectiveness. Washington, D.C: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Girard, A. (2014). Stepping into formal politics women’s engagement in formal political processes in irrigation in rural India. World Dev. 57, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.11.010

Global Delivery Initiative (2015). Indonesia’s Program for Community Empowerment (PNPM), 2007–12 How to Scale Up and Diversify Community-Driven Development for Rural Populations. Washington, DC: Global Delivery Initiative.

Godfrey-Wood, R., and Flower, B. C. R. (2017). Does guaranteed employment promote resilience to climate change? The case of India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). Dev. Policy Rev. 36, 586–604.

Grosh, M., Andrews, C., Quintana, R., and Rodriguez-Alas, C. (2011). Assessing Safety Net Readiness in Response to Food Price Volatility. SP Discussion Paper;No. 1118. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Gupta, B., and Mukhopadhyay, A. (2014). Local Funds and Political Competition: Evidence from the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme in India. ESID Working Paper No. 42. Manchester: University of Manchester.

H.P. State Institute of Rural Development (2017). Factors Facilitating Participation of Women in MG NREGS in Himachal Pradesh. Himachal Pradesh: H.P. State Institute of Rural Development.

Holmes, R., and Jones, N. (2011). “Public works programmes in developing countries: Reducing gendered disparities in economic opportunities?,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Cohesion and Development, 20-21 January 2011, Paris. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0452-0

Holmes, R., Rath, S., and Sadana, N. (2011). An Opportunity for Change? Gender Analysis of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act‘. London: Overseas Development Institute and Indian Institute of Dalit Studies.

IISD (2012). Addressing Climate Change, Biodiversity Loss and Poverty through Sustainable Ecosystem Management. Winnipeg, MB: IISD.

JICA (2011). Data Collection Survey on Forestry Sector in India. Tokyo: Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

Jose, J., and Radhakrishnan, R. P. (2018). Impact of MGNREGP on the socio-economic empowerment of rural women with special reference to Thrikkur Grama Panchayath, Thrissur District. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 5, 1005–1008.

Kanaan, T. H. (1997). “Social safety nets: experiences of some Arab countries,” in The Social Effects of Economic Adjustment on Arab Countries, ed. T. H. Kanaan (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Kanwal, V., Divya, P., and Suhasini, K. (2017). Effect of forest development programme in income, employment and nutritional intake: case study of nainital. Indian J. Econ. Dev. 13, 369–374. doi: 10.5958/2322-0430.2017.00172.x

Kartika, K. T. (2015). Impact of MGNREGA on socio-economic development and women empowerment. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 17, 16–19.

Keerthi, K. (2014). Impact of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) on Individual and Community Assets Creation and their Sustainability in Selected Villages of Prakasam District of Andhra Pradesh. M. Sc. Thesis. Hyderabad: Acharya N.G. Ranga Agricultural University.

Khera, R., and Nayak, N. (2009). “Women workers and perceptions of the national rural employment guarantee Act in India,” in Paper Presented at the FAO-IFAD-ILO Workshop on Gaps, Trends and Current Research in Gender Dimensions of Agricultural and Rural Employment: Differentiated Pathways out of Poverty, Rome.

Kostzer, D. (2008). Argentina: A Case Study on the Plan Jefes y Jefas de Hogar Desocupados, or the Employment Road to Economic Recovery. Working Paper No. 534. Annandale-On-Hudson, NY: The Levy Economics Institute.

Kumar, P. (2018). “Employment generation under MGNREGA: spatial and temporal performance across states,” in Employment Guarantee Programme and Dynamics of Rural Transformation in India. India Studies in Business and Economics, eds M. Bhattarai, P. K. Viswanathan, R. Mishra, and C. Bantilan (Singapore: Springer).

Kumar, S. (2017). 11 Years of NREGA: Surjit Bhalla on the Failure of the Scheme. Available online at: https://www.thequint.com/news/india/nrega-has-been-a-horrendous-failure-economist-surjit-bhalla (accessed December 19, 2021).

Kumar, S., Madheswaran, S., and Vani, B. P. (2021). Response of poverty pockets to the right-based demand-driven MGNREGA programme. Rev. Dev. Chang. 26, 5–24. doi: 10.1177/09722661211005580

Lengefeld, E., Stringer, L. C., and Nedungadi, P. (2021). Livelihood security policy can support ecosystem restoration. Restor. Ecol. e13621. doi: 10.1111/rec.13621

Lieuw-Kie-Song, M., Philip, K., Tsukamoto, M., and van Imschoot, M. (2011). Towards the right to work: Innovations in Public Employment Programs (IPEP). Employment Working Paper No. 69. Geneva: ILO.

Mackintosh, F., and Blomquist, J. (2003). Systemic Shocks and Social Protection : The Role and Effectiveness of Public Works Programs. Social Safety Nets Primer Notes; No. 1. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Mahapatra, R. (2021). How Women Seized NREGA. Available online at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/how-women-seized-nrega-2282 (accessed December 19, 2021).

McCord, A. (2008). A Typology for Public Works Programming. Natural Resource Perspectives. Available online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20091205001314/http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/download/2608.pdf (accessed July 4, 2021).

McCord, A. (2012). Public Works and Social Protection in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Public Works Work for the Poor?. Tokyo: United Nations University Press, 304.

McCord, A., and Paul, M. H. (2019). An Introduction to MGNREGA Innovations and Their Potential for India–Africa Linkages on Public Employment Programming. Available online at: https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/Working%20Paper%20-%20An%20Introduction%20to%20MGNREGA%20Innovations%20and%20their%20Potential%20for%20India-Africa%20Linkages.pdf (accessed July 4, 2021).

Mehta, A. K., and Saha, A. (2001). Chronic Poverty in India: Overview Study. Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working Paper No. 7. Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID1754532_code1382430.pdf?abstractid=1754532&mirid=1 (accessed December 4, 2021).

Mensah, J. (2019). Sustainable development: meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 5:1653531. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2019.1653531

Ministry of Rural Development (2012). MGNREGA Sameeksha: An Anthology of Research Studies on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005 2006–2012, eds M. Shah, N. Mann, and V. Pande (New Delhi: Orient BlackSwan).

Mishra, P., and Mishra, S. K. (2018). “Asset creation under MGNREGA and sustainable agriculture growth: impacts of convergence initiatives in Odisha and West Bengal,” in Employment Guarantee Programme and Dynamics of Rural Transformation in India. India Studies in Business and Economics, eds M. Bhattarai, P. K. Viswanathan, R. Mishra, and C. Bantilan (Singapore: Springer).

Mission Directorate (2021). © Mahatma Gandhi NREGS Odisha. Available online at: http://odishamgnregs.org/success_story_view_details.php?cid=1&sid=2350 (accessed November 4, 2021).

Mvukiyehe, E. (2018). What are We Learning About the Impacts of Public Works Programs on Employment and Violence? Early Findings from Ongoing Evaluations in Fragile States. Available online at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/impactevaluations/what-are-we-learning-about-impacts-public-works-programs-employment-and-violence-early-findings (accessed October 13, 2021).

Nagaraja, J. (2021). Empowerment of tribal women through MGNREGA: a study of MGNREGA implementation in Ballari district, Karnataka. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 9, 3055–3063.

Narayanan, S., Ranaware, K., Das, U., and Kulkarni, A. (2014). MGNREGA Works and their Impacts – A Rapid Assessment in Maharashtra. Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute for Development Research.

National Institute of Statistics Rwanda (2021). Vision 2020 Umurenge Program (VUP) – Baseline Survey. Kigali: National Institute of Statistics Rwanda.

Oyeshola, D. (2007). Development and poverty: a symbiotic relationship and its implication in Africa. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 4, 553–558. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v4i4.31250

Panda, B., Dutta, A., and Prusty, S. (2009). Appraisal of MGNREGA in Sikkim and Meghalaya, Ministry of Rural Development/UNDP. Shillong: Indian Institute of Management.

Pankaj, A., and Tankha, R. (2010). Empowerment effects of the NREGS on women workers: a study in four states. Econ. Polit. Weekly 30, 45–55.

Parth, M. N. (2019). Hailstorms at 43°C wreck farming in Latur. Available online at: https://www.in.undp.org/content/india/en/home/climate-and-disaster-reslience/successstories/pari-undp-series/hailstorms-latur.html (accessed November 6, 2021).

Peedikakandi, S., Prema, A., and Anitha, S. (2015). Mahatma Gandhi national rural employment performance of MGNREGS on income and employment of agricultural labourers. J. Trop. Agric. 53, 91–94.

Ranjan, R. (2019). Combining carbon pricing with LPG subsidy for promoting preservation and restoration of Uttarakhand forests. J. Environ. Manag. 236, 280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.01.110

Ravindar, M. (2016). Empowerment of women through MGNREGA-a study in Warangal district of Telangana state. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Modern Educ. 2, 309–321.

Rimki, P. (2012). Women empowerment: establishment of micro-credit groups and guaranteed employment as a mean to empower women. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 1, 1–5.

Roe, D., Seddon, N., and Elliott, J. (2019). Biodiversity Loss is a Development Issue: A Rapid Review of Evidence. IIED Issue Paper. London: IIED.

Saigal, S., Kumar, C., and Chaturvedi, R. (2016). Nadi bachao samriddhi lao – a forest landscape restoration initiative in Harda district, Madhya Pradesh, India. World Dev. Perspect. 4, 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.wdp.2016.11.016

Sanjay, K., Kumari, M., and Alam, S. (2018). Ground realities and inhibitions in execution of MGNREGA in Jharkhand, India. Asian J. Res. Soc. Sci. Hum. 8, 74–93. doi: 10.5958/2249-7315.2018.00009.6

Sanyal, M. S. (2017). Rural development & Mahatma Gandhi national rural employment guarantee act (mgnrega) in West Bengal, India: – it’s activity and effectiveness. ZENITH Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 7, 78–89. doi: 10.4135/9788132108399.n5

Saxena, A., Dutt, A., Fischer, H. W., Saxena, A. K., and Jantz, P. (2021). Forest livelihoods and a “green recovery” from the COVID-19 pandemic: insights and emerging research priorities from India. For. Policy Econ. 131:102550. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102550

Shah, M. (2016). Should India do away with the MGNREGA? Indian J. Labour Econ. 59, 125–153. doi: 10.1007/s41027-016-0044-1

Sharma, A. (2011). Sharing Innovative Experiences, Volume 18: Successful Social Protection Floor Experiencies, ILO - SU/SSC (UNDP) – National experts, 2011. New York, NY: The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 271–290.

Sharma, A. (2015). Rights-Based Legal Guarantee as Development Policy: The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. Working Papers. Mumbai: eSocialSciences.

Shukla, N. (2021). Uttar Pradesh Achieves New Green Feat, Plants 25.5 Crore Saplings in a Day. Available online at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/lucknow/uttar-pradesh-achieves-new-green-feat-plants-25-5-crore-saplings-in-a-day/articleshow/84130093.cms (accessed July 5, 2021).

Singh, K., and Mann, V. (2020). A discussion on rural development strategies of Haryana. Asian J. Sociol. Res. 3, 1–4.

Singh, L., Sridharan, S., Thul, S. T., Kokate, P., Kumar, P., Kumar, S., et al. (2020). Eco-rejuvenation of degraded land by microbe assisted bamboo plantation. Ind. Crops Prod. 155:112795. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112795

South African Government (2021). Expanded Public Works Programme. Cape Town: South African Government.

Stahlberg, S. (2012). India’s Latest and Largest Workfare Program: Evaluation and recommendations’. Stanford, CA: Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law.

Subbarao, K., del Ninno, C., Andrews, C., and Rodríguez-Alas, C. (2013). Public Works as a Safety Net : Design, Evidence, and Implementation. Directions in Development;Human Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Sudarshan, R., Bhattacharya, R., and Fernandez, G. (2010). Women’s participation in the NREGA: some observations from fieldwork in Himachal Pardesh, Kerala, and Rajasthan. IDS Bull. 41, 77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00154.x

The World Bank (2009). How to Make Public Works Work: A Review of the Experiences. Safety Nets Primer, The World Bank, No. 31. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

The World Bank (2011). Perspectives On Poverty In India. Stylized Facts from Survey Data. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Tiwari, R., Somashekhar, H. I., Kumar, B. K. M., Param, V. R. R., Murthy, I. K., Kumar, M. S. M., et al. (2011). MGNREGA for environmental service enhancement and vulnerability reduction: rapid appraisal in Chitradurga District, Karnataka. Econ. Polit. Week. 46, 39–47.

Upendranadh, C., and Tankha, R. (2009). Institutional and Governance Challenges In Social Protection: Designing Implementation Models For The Right To Work Programme in India Working paper No. 48. New Delhi: Institute For Human Development.

Viswanathan, P. K. (2013). “Conservation, restoration, and management of mangrove wetlands against risks of climate change and vulnerability of coastal livelihoods in Gujarat,” in Knowledge Systems of Societies for Adaptation and Mitigation of Impacts of Climate Change, eds S. Nautiyal, K. Rao, H. Kaechele, K. Raju, and R. Schaldach (Heidelberg: Springer), 423–441. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-36143-2_25

Viswanathan, P. K., Mishra, R. N., Bhattarai, M., and Iyengar, H. (2014b). Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee (MGNREGA) Programme in India: A Review of Studies on its Implementation Performance, Outcomes and Implications on sustainable Livelihoods across States. Ahmedabad: Gujarat Institute of Development Research.

Viswanathan, P. K., Mishra, R. N., and Bhattarai, M. (2014a). Gender Impact of MGNREGA: Evidence from 10 Selected Semi-Arid Tropics (SAT) Villages in India. Montpellier: CGIAR.

Keywords: public works programs, MGNREGS, poverty alleviation, reforestation, afforestation

Citation: Angom J and Viswanathan PK (2022) Contribution of National Rural Employment Guarantee Program on Rejuvenation and Restoration of Community Forests in India. Front. For. Glob. Change 5:849920. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2022.849920

Received: 06 January 2022; Accepted: 19 April 2022;

Published: 28 June 2022.

Edited by:

Tapan Sarker, University of Southern Queensland, AustraliaReviewed by:

Saudamini Das, Institute of Economic Growth, IndiaCopyright © 2022 Angom and Viswanathan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juliet Angom, anVsaWV0YW5nb21AZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.