94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. For. Glob. Change, 23 November 2022

Sec. People and Forests

Volume 5 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2022.1019994

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Utilization and Management of Forest Resources in South and Southeast AsiaView all 5 articles

The positive social and environmental outcomes of involving local and indigenous people in environmental management have made their inclusion in forest management increasingly considered. However, in Malaysia, where indigenous forest-dependent communities, known as the Orang Asli, are not yet involved in forest management, their significance needs to be empirically recorded. This study aims to investigate the relevance of involving the Orang Asli in Malaysia’s forest management. The study employed a participant observational study at Kampung Tanjung Rambai, an Orang Asli settlement located in the Malaysian state of Selangor. Dwelling with the community and engaging in their forest-based lives for a course of 1 month have managed to capture their current relationships with the forest, which were then analyzed to determine their roles as meaningful stakeholders. The results show that the community has maintained a relationship with their land that may ensure the prudent use of resources. Furthermore, their forest-based lives can be regarded as small-scale disturbances in the forest ecosystem, which are necessary for maintaining resilience.

The compatibility of local and indigenous peoples’ knowledge and ways of life with the conservation of ecosystems and natural resource management has been recorded in many parts of the world (Joa et al., 2018; Abas et al., 2022; Jessen et al., 2022). As the environment is progressively being understood as a complex social–ecological system, such compatibility calls for more inclusive management, in which local and indigenous people are deemed capable of contributing to more desirable management in the face of unprecedented global change and uncertainty (Ban et al., 2018; Molnár and Babai, 2021; Ullah et al., 2021; Jessen et al., 2022). Local and indigenous people who were previously overlooked and excluded in the conventional management of the environment are increasingly being considered meaningful stakeholders, offering an alternative set of management to the table with the traditional ecological knowledge and values that are embedded in their worldviews (Berkes, 2012; Molnár and Babai, 2021). The fact that they depend on a wide array of natural resources in many ways, from food sources to spiritual matters, and yet their territories coincide with ∼40% of terrestrial conserved areas, lower deforestation rates, and maintained biodiversity further highlights the merits of their perspectives and experiences (Fromentin et al., 2022; IPBES, 2022).

In the context of forests, history has recorded that their conventional management was preferably under technocratic control to generate revenue for development. National interests took precedence over local and indigenous forest-dependent communities that have unfortunately benefited the least (Banuri and Marglin, 1993; Wiersum, 1999; Larson et al., 2012). Seemingly, such management has failed in catering to the needs of forest-dependent communities and accommodating the value of forests beyond merely economic. Even though local and indigenous peoples’ longstanding proximity to and dependence on forest ecosystems may confer significant expertise and knowledge of the forest, they are considered irrelevant and regarded as unscientific. In some cases, indigenous peoples were even seen as a hindrance to forestry in the development and encroachers of state-owned forests (Cooke, 1999; Aiken and Leigh, 2011; Chao, 2012; Barreau et al., 2016). Meanwhile, their proximity to the forest makes them the first ones to be affected by the degradation of forests, as is the case for many forests under centralized control and management (Banuri and Marglin, 1993; Larson et al., 2012; Cox, 2016). The stewardship of forests by local and indigenous forest-dependent communities will not only benefit themselves but is also believed to be in the best interests of urban societies, all the more so in today’s globally intertwined social–ecological system, where “everyone is in everyone else’s backyard” (Folke, 2016). Conflicting interests in the forest due to the various goods and services that are valued differently require measures to bring them together in harmony. Exclusionary approaches, however, will rather hinder efforts to achieve so.

More recently, studies highlight the need to emphasize managing the resilience of social–ecological systems to sustain development rather than merely sustaining production for development (Berkes et al., 2003; Tengö et al., 2014; Folke, 2016). The proponents of resilience thinking suggest that incorporating different types of knowledge would be beneficial in the face of uncertainty and a host of unknowns, which are among the intrinsic features of the everchanging social–ecological system (Berkes et al., 2003; Westley et al., 2011; Berkes, 2012; Folke, 2016). Disciplinary boundaries are instead viewed as an impediment to better understanding the dynamics and complexities of human–environment systems (Rosa and Dietz, 1998; McIntosh et al., 2000; Gunderson and Holling, 2002; Berkes et al., 2003; Berkes, 2012; Fromentin et al., 2022). The separation between natural and social sciences and the exclusiveness of scientific knowledge over other kinds of knowledge will add to the problem rather than the solution. Though often dismissed as being unscientific and irrational, sustainability has been essential to the wellbeing of local and indigenous peoples throughout the world and is maintained through their knowledge, practices, and spirituality (IPBES, 2022). Ensuring that their sustainable use of natural resources that are embedded in and maintained through their cultures has been pointed out as having the potential to meet the sustainable development goals, yet is still largely overlooked (Fromentin et al., 2022). Learning from and collaborating with local and indigenous peoples who have adapted their lives in the forest and retained strong connections with their land may therefore be of utmost importance in attempting to reconcile various interests and conflicting values in the forest. Perhaps due to the increasing support and recognition for this, there has been an increasing trend in the shift from industrial forests to community forestry involving local and indigenous communities (Barron et al., 2022).

Approximately, one-fifth of the world’s remaining tropical forests are situated in Southeast Asia (Butler, 2021), and they play important roles in environmental protection, biodiversity, as well as in socio-economy and the living conditions of forest-dependent communities in the region (Fui et al., 2012; Stibig et al., 2014). A study by Poffenberger (2006) has documented experiences from an inclusive forestry mechanism known as Community Forest Management (CFM) in five Southeast Asian nations, namely Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. The study reveals the shift from forest management goals oriented at timber production toward multipurpose and adaptive management goals, which extend forest management responsibilities, rights, and roles to local forest-dependent communities that have affected forest cover, biodiversity, and local livelihoods in a compelling way. More recent studies on CFM in the region corroborate how CFM can be a win-win solution for achieving environmental as well as societal goals (Diansyah et al., 2021). As society’s demands for forest goods and services continue to change and differ on multiple spatial and temporal scales, Sayer and Collins (2012) argue that forests should indeed be governed based on the search for ways to encourage cross-learning, achieve a compromise, and accommodate agreements to be able to facilitate those changes in an equitable and considered way. Though results may differ across multiple scenarios, CFM has been shown to facilitate just those (Diansyah et al., 2021). Tenure arrangements like CFM provide secure rights over land and resource use that can incentivize conservation, sustainable use, and diverse livelihoods that contribute to human wellbeing, while at the same time ensure that the ecological conditions are maintained (IPBES, 2022). However, the relationship between people and the forest is subject to change, so it is necessary to inquire about the current state of local and indigenous forest-dependent communities that has not been rightfully considered in forest management.

Despite the increasingly recognized significance of local and indigenous peoples in forest management, a study in the Philippines indicates that indigenous knowledge systems are slowly disappearing due to the changing needs and interests of the indigenous peoples as well as efforts to modernize them (Camacho et al., 2016). Similarly, in Indonesia, many traditional systems of natural resource management that are in line with the values of biodiversity conservation are being left behind as development toward the modern economy provides many improvements in the lives of the people (Boedhihartono, 2017). Changes in society are inevitable, and the extent is even more so considerable in an increasingly globalized world where foreign influence has encroached into the doorsteps of previously isolated communities. The changes will undeniably alter the human–environment relationship among forest-dependent indigenous communities, along with the ecological feedback that comes with it. For instance, IPBES reports that the integration into monetized and commodified economic systems has undermined local and indigenous peoples’ values toward nature and the sustainable use of wild species (IPBES, 2022). Without proper recognition and arrangements in addressing social and ecological changes, the forest’s resilience as an interdependent social–ecological system is therefore at risk of being compromised (Folke et al., 2016).

This study is particularly concerned with indigenous forest-dependent communities in the Malaysian context. While indigenous territories make up at least 36% of the world’s intact forests and their significance in nature conservation has been recorded (Fa et al., 2020; Butler, 2021; Abas et al., 2022), the indigenous peoples in Malaysia are still struggling for the rights to their ancestral lands, and their significance in forest conservation and management continue to be undermined (Amnesty International, 2018; Fa et al., 2020; Mohd et al., 2021). A distinction between the notion of indigenous and local should be emphasized, whereby the former has a sense of the temporal dimension and cumulative cultural transmission that are not necessarily attributes of the latter (Berkes, 2012). Indigenous communities are known to have a longstanding relationship with the land and environment where they reside, with historical continuity of resource use and knowledge embedded in the cultural milieu (Fa et al., 2020; Molnár and Babai, 2021; Jessen et al., 2022). With their knowledge of the forest that may complement science, the significance of the forestland to their culture, as well as their preference for a well-functioning forest for their own wellbeing, it is expected that their inclusion in forest management would be more inclined to forge toward a path that could maintain the resilience of the forest and its peoples.

In Malaysia, the significance of indigenous people in forest management has yet to be formally recognized and is under-explored (Diansyah et al., 2021; Abas et al., 2022). Meanwhile, their forest-based lives do not develop in a vacuum and are subject to exogenous socio-economic pressures. Their exclusion in forest management implies that there is a lack of necessary considerations in addressing the impacts of social–ecological changes on Malaysia’s forests, particularly concerning indigenous forest-dependent communities. As societies continue to change and impact the environment, the environmental changes will in turn affect societies in ways that require them to have the capacity to cope and adapt to sustain. Exclusionary and rigid approaches, however, will rather suppress possibilities to innovate and adapt to changes in a timely and flexible manner, which can consequently lead to the loss of resilience (Berkes et al., 2003; Folke et al., 2016).

Forestry in Malaysia is basically decentralized under the authority and jurisdiction of respective state governments. The federal government’s role in the management of Malaysia’s forests is limited to providing recommendations and assistance (Shahwahid, 2006; Sayer and Collins, 2012; Krishnan et al., 2019). A further down decentralization has been recorded, whereby the locals are involved in a management project as part of Malaysia’s commitment to community participation in forest conservation and development projects (Alam et al., 2021). The commitment, however, has not been adequately reflected with the scant involvement of forest-dependent communities in Malaysia’s forest management, especially when compared with other countries in the surrounding region and considering the number of forest-dependent communities in Malaysia (Diansyah et al., 2021; Abas et al., 2022). Moreover, the indigenous people of the Malaysian Peninsular, the Orang Asli, who are notably close to the forest both in terms of culture and physical proximity, appear to be overlooked in forest management despite ample evidence pointing out their significant forest-related knowledge and continued dependence on the forest (Howell et al., 2010; Azliza et al., 2012; Ong et al., 2012a,b; Kardooni et al., 2014; Keat et al., 2018; Jamian and Mohd Ghazali, 2021).

The Orang Asli has historically been recorded as forest dwellers (Gomes, 2004). They are a minority group of people comprising only 0.6% of the total population of Malaysia (Kamal and Lim, 2019). The Orang Asli is a Malay phrase that literally means the “original peoples,” which refers their indigeneity since they have lived in the country for long, even before the arrival of other groups including the Malays, the current ethnic majority (Nicholas, 2000). They are not homogenous people and constitute 18 ethnic subgroups officially classified for administrative purposes under Negrito, Senoi, and Aboriginal Malay (Nicholas, 2000). Although they have been residing in the now Malaysian land since time immemorial, their ancestral lands have been largely targeted for resource extraction, conversion to plantation crops, and development of infrastructure (Cooke, 1999; Nicholas, 2010; Aiken and Leigh, 2011; Amnesty International, 2018; Kamal, 2020; Abraham and Ng, 2021). Apparently, the significance of their forest-based lives has not received the recognition it deserves in the management of Malaysia’s forests.

Although on one hand studies have suggested that more desirable forest conservation and management should not leave out the Orang Asli as key stakeholders (Gill et al., 2009; Aziz et al., 2013; Shaleh et al., 2016; Kamal and Lim, 2019; Kamal, 2020; Abraham and Ng, 2021), forest management and development projects rather tend to exclude and even displace Orang Asli communities in its practice, and on the other hand, these communities continue to change from time to time because they are not free from external socio-economic pressures. Therefore, it is necessary to thoroughly investigate the relevance of their involvement in forest management as long as they have yet to be rightfully considered and formally acknowledged. This study investigates and explores the current forest-based lives of an Orang Asli community of the Temuan ethnic subgroup so that not only could they be of use to and get incorporated into forest management at the very least but especially promote their lead in forest conservation and management programs as key stakeholders should. Considering the fact that the Orang Asli is not a homogenous group of people, the human–environment relationship between one community and the other may also differ significantly. Hence, the push to consider the involvement of Orang Asli in forest management based on isolated cases needs to be substantiated by cases elsewhere.

In an extension to previous studies that have documented Orang Asli’s Forest-related empirical knowledge as well as land and resource management systems (Howell et al., 2010; Ong et al., 2012a; Kardooni et al., 2014; Shaleh et al., 2016; Keat et al., 2018), this study investigates the relevance of involving the Orang Asli in the management of Malaysia’s forests by delving into the worldview that governs how they shape, manage, and benefit from forests. Using qualitative methods, the relationship between an Orang Asli community of the Temuan ethnic subgroup with the forest that is manifested in their forest resource utilization is observed. A participant observational study was employed, whereby the researcher lived with the community for 1 month and got involved in the forest-based livelihoods of the community. By getting a grasp on their human–environment relationship, the feasibility and practicability of collaborating with and actively involving the Orang Asli in forest management can be analyzed and concluded whether managing Malaysia’s forests for a more resilient social–ecological system should be achieved with their inclusion.

Malaysia is separated into two mainland areas by the South China Sea. The Peninsular Malaysia on the west occupies the southern part of the Malay Peninsula and East Malaysia adjoins Brunei and Indonesia’s Kalimantan on the island of Borneo. In Peninsular Malaysia, the Orang Asli, whose lives are dependent on the forest and the natural environment for subsistence economies, are acknowledged by the Malaysian Constitution as the indigenous peoples of the peninsula (Azima et al., 2015). The Orang Asli is not a homogenous group of people and has an estimated population of 178,197 people belonging to 18 subgroups that are further grouped into three main categories: Negrito which consists of the Bateq, Lanoh, Jahai, Menriq, Kintak, and Kensiu peoples; Senoi which consists of the Semai, Temiar, Semoq Beri, Che Wong, and Jahut peoples; and Proto-Malay which consists of the Temuan, Semelai, Jakun, Orang Kanaq, Orang Kuala, and Seletar peoples (Man and Thambiah, 2020).

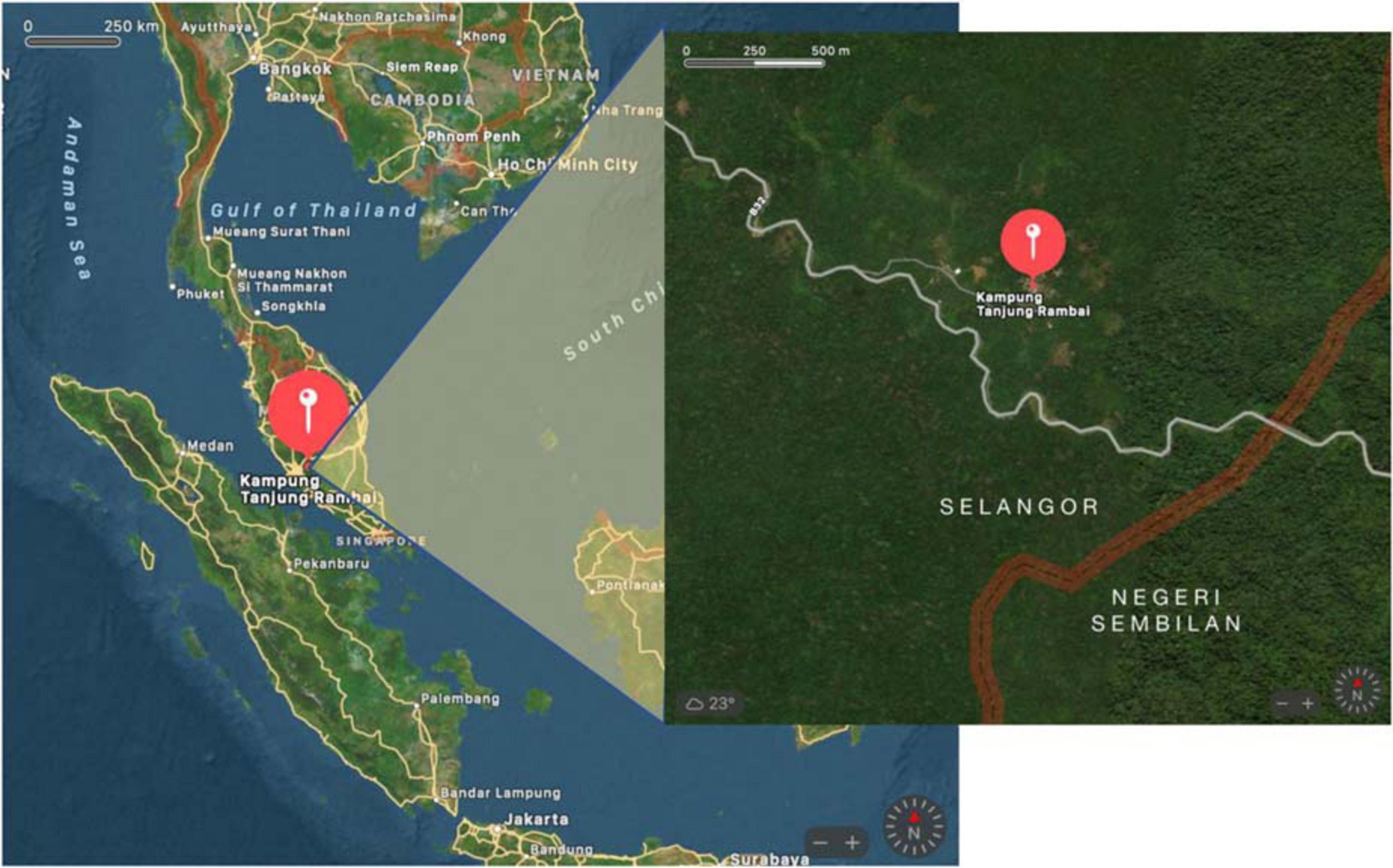

The study was conducted in Peninsular Malaysia involving an ethnic subgroup of the Proto-Malay Orang Asli subgroup, namely the Temuan people (hereinafter referred to as Orang Temuan). The Orang Temuan was selected considering the proximity of their settlement to where the researchers reside and their dependence on the forest which has been recorded by Indriatmoko (2006). The Orang Temuan community involved in this study resides in a settlement officially known as Kampung Genting Peras, but referred to as Kampung Tanjung Rambai by their people. The Kampung, which literally means village, is located in the Hulu Langat District within the state of Selangor, not far from the borders of Negeri Sembilan (Figure 1). It is ∼45 km to the northeast of Kajang, a well-developed urban area in the same state where the researcher resides. Kampung Tanjung Rambai is nestled among the densely vegetated landscape of the Hulu Langat Forest Reserve, which is a drastic shift from the human-packed urban setting of Kajang, roughly about 2 h ride away. The forest surrounding Kampung Tanjung Rambai is classified as Hill Dipterocarp Forest which lies at an elevation between 300 and 800 m above sea level and is significant to the livelihoods and culture of the people.

Figure 1. Location of Kampung Tanjung Rambai. Source: Apple Maps accessed at 21.42 (GMT + 7) on 14 October 2022.

The inhabitants of Kampung Tanjung Rambai are predominantly descendants from a nearby community in a Kampung named Paya Lebar located about 10 km by road downstream of the Sungai (river) Lui. It was said that in the 1980s, some elders in Paya Lebar who had foreseen the place as increasingly being surrounded by the Malay ethnic majority considered moving upstream to the now Kampung Tanjung Rambai as they sought to avoid conflicts over land and resources. There are currently around 32 households in Kampung Tanjung Rambai, many of whom are still closely related, similar to their predecessors in Kampung Paya Lebar, who have been recorded as having bounded together by kinship and affinal ties as well (Gomes, 1982). Information regarding the exact number of housing and families was not obtained because some extended families happen to occupy the same household and was considered insignificant for this study.

The basic social unit in Tanjung Rambai is the nuclear family, which plays a key role in passing down the community’s cultural values to the younger generation. The nuclear family is also the basic economic unit whereby each family maintains its own horticultural land area known as kebun. The kebun is a patch of forest land nearby the kampung that is converted to cultivate crops for their livelihood. Although some have chosen to work outside the Kampung as wage laborers, the majority of people in Kampung Tanjung Rambai still mainly rely on land resources from the kebun for their means of sustenance, just like their predecessors at Paya Lebar (Gomes, 1982). Each household nurtures its own kebun that will eventually be inherited by the children to be taken care of and benefit from. Another land category is called the dusun, which is an orchard typically planted with durian trees by their predecessors. The dusun is generally located deep in the forest and is quite a long journey to reach since the people do not frequently go there unless it is the fruiting season. Unlike the inheritance of kebun, which is limited to the nuclear family (from the parents to their children), the dusun is passed on to the next generation of the extended family. On some occasions, the presence of these land management systems can serve as the basis to claim land where the trees grown in the kebun and dusun are evidence of a longstanding relationship with the land. The land between a certain family-owned kebun, dusun, and another’s is generally not demarcated by a prominent barrier, but the people are quite familiar with the boundaries of their territory and respect one another’s.

Apart from horticulture, many still derive forest products such as snaring wild game, harvesting wild honey of various bee species, collecting dammar resin, rattan, and various other non-timber forest products. These forest products are obtained both for personal consumption and are sold to the outside market for additional income. The people of Kampung Tanjung Rambai are connected to the outside market through middlemen whom they call tauké. The tauké usually belong to the Chinese and Malay ethnicities who come to pay regular and occasional visits to Kampung Tanjung Rambai as the villager’s business associate, trading kebun/dusun produce and a wide array of other non-timber forest products with cash. Often, the taukés will request certain goods in the forest for the Orang Temuan to look for, without which they do not. As has been recorded by Indriatmoko (2006), the relationship between taukés and the Orang Temuan is a mutual economic relationship based on trust that persists to date.

Based on the suggestions by Jessen et al. (2022) and in line with the goal of involving the Orang Asli in forest management, it was deemed necessary to position those involved in this study as more than just informants, to begin with. To acknowledge the voices of indigenous people in academia, who are generally referred to merely as “informants” and remain anonymous in a conventional research setting, it was considered necessary to treat the participants of this study more as collaborators who deserve equal credit and respect. Hence, the information that has been acquired from the Orang Temuan in Kampung Tanjung Rambai is cited following the templates of citing indigenous knowledge holders that were developed and proposed by MacLeod (2021). In agreement with MacLeod’s (2021) proposition that indigenous people’s oral teachings deserve the credit it merits so as to not see them as lesser than Western written materials, those who took part in this study are referred to according to their respective names with their own consent.

In the case of this study, it was impossible to involve the whole community due to limited time and resources. Apart from the fact that it was impossible to delve into all the lives of the people in the research setting in only 1 month, the people’s openness to the researcher’s presence differed significantly. Therefore, this participant observation intensively involved the extended family of Arwah Embong (Arwah refers to one who has deceased), who have been welcome to the researcher’s presence since the very beginning. For this warm welcome by the extended family, sincere gratitude is conveyed to Mr. Yayan Indriatmoko who initially introduced the researcher to the people of Kampung Tanjung Rambai.1 The children of Arwah Embong have raised their own families and have grandchildren of their own, living in separate houses not far from each other in the Kampung. In other words, the main research participants in this study were the extended family of Arwah Embong, whose house accommodated the researcher during data collection. Among the members of Arwah Embong’s extended family who became the main participants of this study were as follows:

1. Til bin Embong and his wife Aznah binti Aling (bin refers to “the son of” whereas binti refers to “the daughter of”) welcomed the first researcher and introduced him to the Tok Batin (an honorific title that refers to the highest leadership rank in the community who holds the most authority) as well as to the other members of Arwah Embong’s extended family. They also provided an introduction to the Orang Temuan culture and language, which was very much needed for this study. Til bin Embong is hereinafter referred to as T. Embong and Aznah binti Aling is referred to as Aling.

2. Ajo bin Til, the son of T. Embong let the researcher be involved in snaring wild game. Ajo bin Til is hereinafter referred to as Til.

3. Yahya bin Embong, the brother of T. Embong, let the researcher get involved in his kebun. Yahya bin Embong is hereinafter referred to as Y. Embong.

4. Ahu bin Embong, the eldest among the Embong brothers, occasionally let the researcher get involved in his livelihood activities that were erratic. Ahu bin Embong is hereinafter referred to as A. Embong.

Local and indigenous knowledge is living knowledge that is rarely written and typically lives with the elders. Studying such knowledge often requires observation, imitation and practice, and even apprenticeship (Gamborg et al., 2012). Since such knowledge is often locally and culturally specific, combining facts and values, it is better suited for a case study that utilizes a participant observation research model. Hence, the first researcher dwelled with the Orang Temuan of Kampung Tanjung Rambai and lived there in November 2021 to record sufficient data. Data collection in the field was mainly done by the first researcher who stayed at the Kampung throughout November 2021 and only went back home once a week on the weekends of that month. Through participant observation, informal and casual interviewing were combined along the way for Supplementary Data that clarifies and triangulates observed and experienced phenomena. These informal and casual interviews were written in the field notes and recorded through the Voice Memos application as well as videos recorded through the Photos application on the researcher’s smartphone, according to the allowing circumstances. They were then transcribed later on after the researcher left the Kampung. The interaction with the Orang Temuan was conducted in Malay, a language that both parties could understand well. However, certain native Orang Temuan languages have no Malay equivalence, which required further explanation and clarification along the way.

The extent of participation was clarified to research participants at the onset of the study as suggested by Marshall and Rossman (2016), i.e., what the nature of the involvement is, how much about the study’s purpose is revealed to the people in the setting, how intensively the researcher is present, and how ethical dilemmas are managed. Every involvement in the lives of the people took place with their consent and without any kind of insistence. Data were collected through experiencing first-hand living in Kampung Tanjung Rambai, as the researcher mingled and took part in the forest-based livelihoods of those who were willing to participate in this study. Among those livelihoods involved game snaring, collecting wild honey, working in their rubber plantations, and other horticulture, which were considered land management systems of the forest. In addition, the daily lives of the community were also part of the participant observation study, which was no less important than their forest-based livelihoods because they live close to the forest in terms of physical and spiritual proximity, making the forest closely related to their daily life. In other words, the data collection process was not limited to isolated events, but rather continuous throughout being present in the Kampung. By being directly involved in the community’s environmental–cultural milieu, the human–environment relationship was experienced and observed to get a grasp of their worldview. Data collection aimed to capture the worldview of the people in Kampung Tanjung Rambai to explore the nature and possibility of integrating the Orang Asli in an inclusive forest management context.

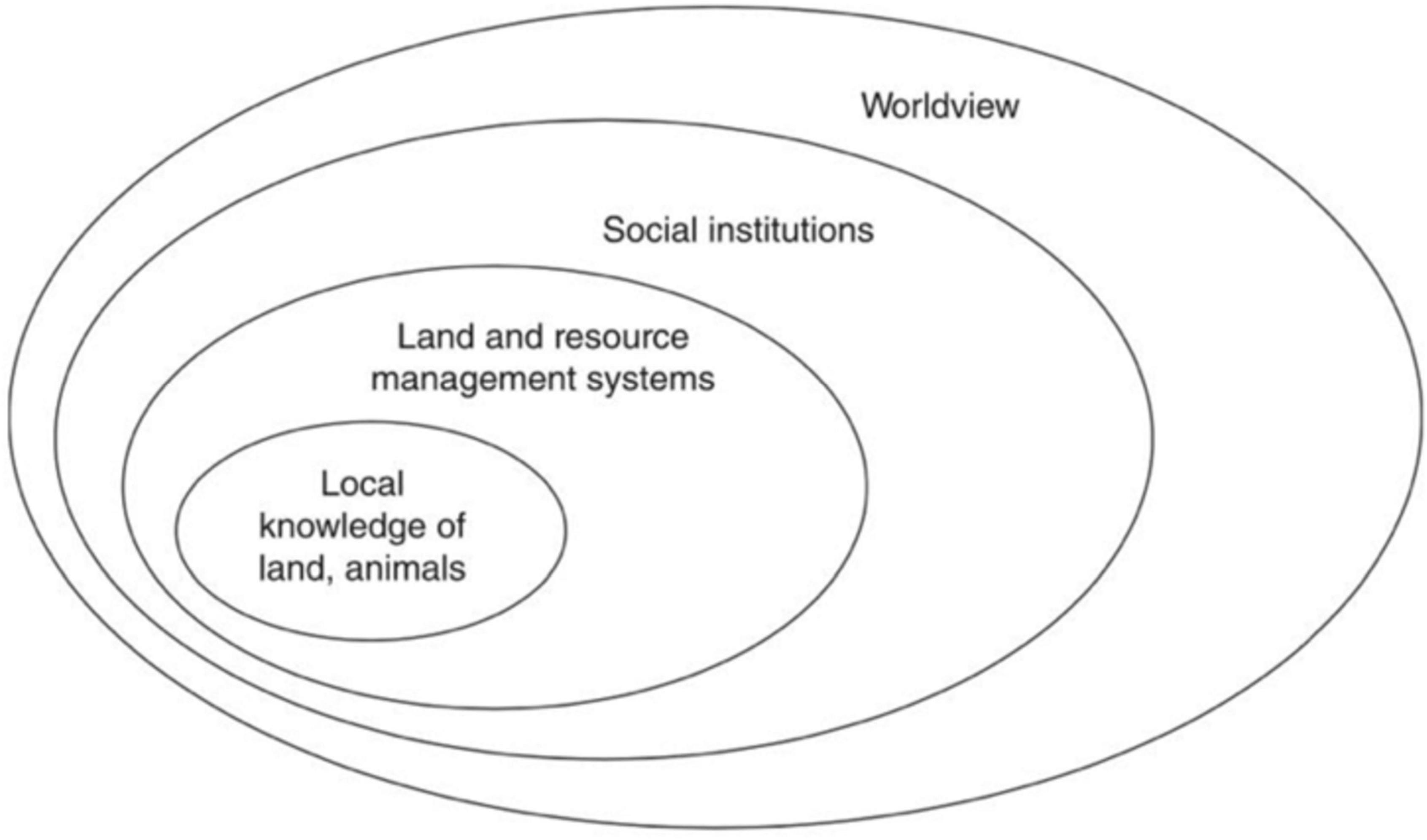

The worldview, according to Berkes (2012), determines human attitudes toward the environment through interpretations of the world we observe. These interpretations are influenced, among other things, by religion, ethics, and more generally, belief systems. Berkes (2012) has illustrated four levels of analysis regarding traditional knowledge in interrelated concentric ellipses (Figure 2), with the worldview as the outermost part that encompasses the other three levels of analysis. Tapping into the community’s worldview through participant observational study, therefore, provided an overview of how the community gives meaning to the forest, which ultimately governs their conduct toward it.

Figure 2. Levels of analysis in traditional knowledge and management systems. Source: (Berkes, 2012, 17).

The data analysis process commenced as the researcher set foot in Kampung Tanjung Rambai. Observed and experienced events were recorded through field notes, photographs, as well as video and voice recordings. Such recordings were in itself part of the analysis, i.e., the descriptive analysis stage whereby empirical facts were described as they were observed or encountered. At this stage, deciding what was relevant became a reflexive activity that informed the data collection process (Marvasti, 2014). The data analysis was therefore not a linear and distinct stage of the research process, but rather a cyclical and dynamic process as the researcher came back and forth between reflection about a problem, data collection, and action (Creswell, 2013; Marvasti, 2014). Meaning-making of the data collected was to some extent attained through a comparative analysis as well. By continually reflecting on what was observed and experienced in the Kampung Tanjung Rambai with other observed phenomena from studies elsewhere, similarities and differences were able to be pointed out to distinguish what is particular or accidental from what is regular and standard (Palmberger and Gingrich, 2014). On the other hand, being immersed in the world of the “other” helped to make sense of phenomena that were highly contextual and hardly conceivable through a scientific or rational lens alone. Getting immersed in the field required the researcher to turn down the role of an expert and remain exploratory and open to changing perspectives as the researcher mingled with the worldview of the “other” to understand how facts are made meaningful by the people in the field. The data collected and analyzed were repeatedly validated with the persons concerned, as well as with other people in the Kampung to ensure that they have not been misrepresented and misinterpreted.

During the first week of the study, the researcher mingled more with people in their daily lives and did not specifically participate in livelihood activities just yet. It was during this period that a relationship of mutual trust was established through casual interactions. Between the early mornings to the afternoon when the grown-ups were busy with their livelihood activities, elementary-school-aged children who happened to be on school leave due to the COVID-19 pandemic helped the researcher in scoping the Kampung. They guided the way and led to various places in their village, from their family’s kebun, the rivers, and to the burial site of their predecessors. During this time, these children have demonstrated exceptional knowledge of their environment, which reveals how they have learned and attuned themselves well to it from early on.

At a very young age, the children’s ability to distinguish the pucuk paku (Diplazium esculentum, vegetable fern as shown in Figure 3) amid the densely planted shrubs in the forest fringes was remarkable. This is perhaps the result of frequent involvement with the parents in foraging edible plants that grow around the kebun and forest fringes, which are either to be sold for the household’s additional income or personal consumption. In addition, children were also often asked by their parents to collect the fallen fruits of pinang (Areca catechu, palm tree nuts as shown in Figure 3) and pluck daun sirih (Piper betle, betel leaves). Pinang and daun sirih are chewed together with lime until the mouths turn red, which is enjoyed by many in Tanjung Rambai as one of their most notable habits. By doing these things, not only do the children become familiar with certain species of plants but they also get to know the functions and significance to their culture. The physical environment, therefore, serves as a learning space for the children, where learning is carried out through hands-on experience with the land.

Figure 3. The children of Tanjung Rambai collecting pucuk paku (A) and buah pinang (B) for their parents. Source: Photographed by the first author in Hulu Langat, Selangor, Malaysia, on 11 and 16 November 2021.

The children’s direct involvement with their parents in various activities in the kampung also allowed them to be more familiar with their environment. For example, in the case when exploring a nearby river, many children followed and insisted that they can catch fish with their bare hands. They began to rummage through the rock crevices without hesitation and struck their hands in it to prove their point, and after quite some time, surprisingly, one of them came back with a fish almost the size of their palms. It turned out they had caught a fish that is known to the locals as ikan daun, whose Latin name is Poropuntius normani [according to Muhammad-Rasul et al. (2018) study]. With adequate skills and knowledge, apparently, ikan daun which is commonly found in the rivers of Tanjung Rambai can indeed be caught with bare hands. The knowledge in question, however, is of course neither a priori nor textbook knowledge.

Catching ikan daun with bare hands requires one to know the fish’s behavior, their preferred hiding spots, and what kind of habitat they live in, which constitutes knowledge of the fish ecosystem. An understanding of the fish ecosystem among the children in Tanjung Rambai is indeed not acquired through educational learning but rather through engaging in activities that interact directly with the fish ecosystem. When the children come along fishing with their parents, they observe what their parents do and experience for themselves, ultimately gaining experiential knowledge about the fish ecosystem. This way of knowing, which builds on experience, is an attribute of societies with historical continuity in resource use on a particular land (Berkes, 2012). Even though the children have not in fact lived on the land for a long time, their familiarity with the land seemed to be extended from the collective experience of the community.

Land-based learning centered on lived experiences nurtures the human–environment relations of people living in a certain place whereby the land becomes the teacher and the classroom that teaches the learners to listen, understand, and connect with it (Nesterova, 2020). In the context of Tanjung Rambai, the unification of nurture and nature is apparent in the relationship of the elders with the younger generation, and between themselves with their land. The elders transmit knowledge to the younger generation orally or by setting examples, while on the other hand, the community’s direct interaction with the environment from early on in their lives nurtures their sensitivity to their natural environment. The long-term interrelationship produces a collective experiential knowledge within the community about the land that forms part of their cultural and spiritual identity as well, therefore making them deeply connected to their environment. They nurture such “kinship” with the natural environment like many indigenous people around the world, according to Pio and Waddock (2021), which has the potential to offer an alternative set of managerial values for environmental management. Not surprisingly, Embong (2021c) stated with confidence that no expert from the forestry department could know the forest better, even with the most sophisticated equipment at their disposal.

Experiential knowledge is considered a useful knowledge source for devising management options as it can complement the available scientific ecological knowledge, which is often insufficient to address environmental management issues alone (Fazey et al., 2006; Gosselin et al., 2018). However, the dissemination of experiential knowledge requires one to observe and experience for themselves since it is understood or implied without being stated. Hence, similar to the production of such knowledge, it is necessary to interact and engage directly with the knowledge holders to be grasped. Exclusionary approaches will limit these possibilities, and a holistic understanding of the forest that involves multiple perspectives would therefore be difficult to achieve, ultimately making synergy in devising the most favorable management for all parties concerned even more challenging. Nonetheless, any kind of knowledge in itself does not guarantee that people will live in harmony with nature (Berkes, 2012). Knowing about the fish ecosystem alone, for instance, will not ensure their prudent harvest and management. There are values and beliefs that are interconnected with knowledge that ultimately determine the human–environment relationship. The experiential knowledge among the people in Tanjung Rambai is probed deeper into by being directly involved in the community’s livelihood activities to shed light on how knowledge, practice, and beliefs are intertwined in their human–environment relations.

The community’s familiarity with the land that results from their long-term engagement with it appears to allow them to be bound to relationships that transcend people and places as mere commodities. This has been manifested in the livelihoods of the people in Tanjung Rambai. Livelihoods are referred to as kerja kampung, which literally translates to “work in the village.” Yet in actuality, the term kerja kampung cannot be interpreted literally as working within the physical boundaries of the kampung since many often trek quite a distance in search of certain forest products. Game trappers even go as far as the forests adjacent to oil palm plantations in the state of Negeri Sembilan, yet are still considered kerja kampung. In addition, searching for certain forest products such as madu kelulut (honey produced by the trigona sp., a stingless bee species commonly found in Malaysia that are locally known as lebah kelulut) requires the people to venture deep into the forest beyond the confines of their Kampung.

The term kerja kampung accommodates a broader meaning than just a certain distance from which a person works; it is a concept that involves the work within the scope of the Orang Temuan’s cultural boundaries. Those who are known to do kerja kampung derive wealth from the land in the ways and traditions of the Orang Temuan. Kerja kampung involves a wide array of livelihoods ranging from working in the kebun as rubber tappers, cultivation of various crops, foraging forest products, game snaring, etc., all of which depend on the allowing circumstances, such as the availability of plants to cultivate, soil fertility, seasons, favorable weather, physical ability, etc., What distinguishes kerja kampung is how their identity as an Orang Asli shape how they carry out their livelihoods. They make their land a source of their wellbeing, yet from engaging in their kerja kampung, it is evident that they do not take excessively from the land. Rather than optimizing labor for a single livelihood to gain the most profit for their wellbeing, they diversify their sources of income from the land and are very flexible. One family may have several kebun located separately around the kampung, and each of the kebun may have various plants cultivated together.

Although their idea of wealth values the land as a source of wellbeing, it does not simply make the people in Tanjung Rambai exploitative toward the land. The community’s conception of the forest is that it provides sustenance as if the forest has a soul, in the sense of being able to consider whether the community is worthy of its resources. Thus, there are ways of deriving its resources that are exclusively based on humility and respect. For instance, one should not be arrogant and “talk big” when entering the forest. Seeking sustenance in the forest requires one to be humble and equipped with good intentions (Aling, 2021; Embong, 2021c). In addition, anything that is derived from the forest, according to their belief, is simply what the forest provides. It is not because of the people’s intelligence, skill, luck, or lack thereof alone, but it is rather the forest that ultimately determines the result. This relationship between the community and the land is a distinctive feature of kerja kampung that treats the land with great consideration, even when working in the kebun.

The kebun cannot indeed be equated with the forest, but they resemble a piece of the forest in which the community cares to generate economic returns because it would not be sensible if they had to go into the forest every single day to fulfill their needs in this day and age. The structure and composition of the plants cultivated in the kebun resemble that of a forest as it is packed with various types of plants grown together for different functions and needs, unlike that of monocultures. Bunga kantan (Figure 4, picture D), for example, are grown in various kebun areas, which allows a person working in a particular kebun to randomly pick its flowers after they are done with their main work in the kebun. This applies to many plants grown in close proximity to the kebun as well. In essence, the kebun is a piece of the forest that is being taken care of and treated with great consideration. As a daily rubber tapper, Embong (2021c) stated that working in the kebun is like taking care of their own children, which requires determination and love for the best results. The best results, however, do not seem to be limited to their quantities.

Figure 4. Some of the kerja kampung in Tanjung Rambai include rubber tapping (A), banana cultivation (B), collecting banana leaves (C) and bunga kantan (D), snaring wild game (E), and collecting stingless bee honey (F). Source: Photographed by the first author in Hulu Langat, Selangor, Malaysia (A–D,F), and Gelami Lemi, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia (E), in November 2021.

The kebun is mostly cultivated with introduced cultivars to serve the outside market such as rubber plantations, durian D24, durian Musang King, bunga kantan, ginger, and pisang mas. Meanwhile, the produce from forest crops is generally harvested for the community’s personal consumption as they are not widely known by the outside market and do not yield as much. However, some forest crops are also grown in the kebun as well, but they are not commercially cultivated and do not require as much care. These forest crops include petai (Parkia speciosa, as shown in Figure 5), manggis (Garcinia mangostana, mangosteen), langsat (Lansium domesticum), cempedak (Artocarpus integer), keledang (Artocarpus anisophyllus), tampoi (Baccaurea macrocarpa), rambai (Baccaurea motleyana), all of which can be consumed and sold on a small-scale for additional income if there is supply and demand. According to Embong (2021c), though forest crops do not yield as much as introduced cultivars, they are generally more disease resistant and yield fruits that are rich in flavor. From just one durian tree, he further explains, one can expect varying tastes among the fruits it produces. This is unlike the introduced cultivars with fruits produced by different individual trees which almost certainly will have the same taste.

Figure 5. A. Embong showing off the petai that he acquired by climbing the tree in his kebun. Despite not having much for himself, he insisted on sharing with the researcher in this encounter. Source: Photographed by the first author in Hulu Langat, Selangor, Malaysia, on 18 November 2021.

Furthermore, each person in Tanjung Rambai who is involved in the kerja kampung is not restricted to a particular work as they are very flexible. They can work together with their family, relatives, or neighbors, or by themselves and do whichever livelihood is suitable for them in any given situation. For instance, some households who used to cultivate a cultivar of banana known as pisang berangan were having trouble with their crops due to an unfamiliar disease at the time of this study, and hence they simply turned to rubber tapping. Some others harvest another cultivar of banana named pisang mas which is more resistant to the disease, while others gather and sell banana leaves (of the wild type they refer to as pisang hutan), collect bunga kantan that are grown around the kebun, cultivate ginger, and some would go to the forest to look for various forest products in their spare time. There were also some others who trapped wild game in the previous years and then diverted to rubber tapping for the past year due to personal preference. The flexibility implies that the community’s kerja kampung is somewhat closely related to adaptive management which is guided by a sense of appropriateness (Norton, 2018). They do not limit themselves to a single source of provision and with whom they do the work.

Indeed, kerja kampung maintains the community’s traditions of earning a living, which ultimately distinguishes it from the conventional work outside the kampung. It is characterized by the embeddedness of work in the local cultural milieu as well as the commitment to the local physical environment. But this does not mean that the community does not take advantage of technological advances from the outside world to make their kerja kampung easier. They utilize mechanical tools such as chainsaws, lawnmowers, snares, and many other tools not historically used for kerja kampung. Moreover, since there has been electricity in the village over the past year, it has also enabled the efficient use of mobile phones to communicate with the outside world and facilitate the community’s trade relations. This further highlights that kerja kampung is highly flexible to adapt to outside influence and is not hostile to the conveniences offered by modernity. From the observations in Tanjung Rambai, it can be suggested that even with the possession of modern tools and the opportunity to take more from the land, the people still tend to be less exploitative and only take what they need from the land in moderation. However, with such flexibility, kerja kampung will continue to evolve in ways that could be driven by many factors, which can lead to better or worse. Ensuring the community’s wellbeing is met with their current rate of kerja kampung is needed to guarantee that they are not detrimental to the surrounding forest ecosystem conditions so that, on the other hand, the forest could continue to sustain them.

The people in Tanjung Rambai might indeed lack material wealth if compared to urban-dwellers downtown, but when it comes to food they will never go hungry because the land will provide them with almost everything they need (Embong, 2021c). In fact, even though often considered a backward community in need of development, they have never heard of their people and those before them die of starvation and will rather continue to live that way than move into urban areas that can be stressful to them (Aling, 2021; Embong, 2021a,b,c). This then raises the question of the need to develop for whom (de Oliveira, 2020), if the prescribed development scheme does not in fact fit with their aspirations. The forest is their life and living off of it is the kind of life they wish to pursue. Therefore, developing the Orang Asli should consider how their kerja kampung can be maintained to improve their wellbeing without compromising on forest conditions rather than efforts to integrate them into modernity and the market economy, which could in fact lead them into the poverty trap. Working together to ensure this is therefore necessary to better understand how their kerja kampung impacts the forest ecosystem and how socio-economic drivers influence them.

According to Aling (2021), the community will be forever grateful for the sustenance provided by the land, be it large or small, of good or bad quality. They would generally express gratitude by sharing forest products and kebun harvest with their relatives and fellow neighbors, especially during the annual durian harvest, which brings a considerable amount of revenue to the community. In the past, it was customary to share forest products such as game meat with the whole kampung, but as the population grew, they only share with those closest to them by kinship or proximity to their homes. However, social values of sharing with other community members are still very strong as demonstrated in the following case. One day, a group of game trappers managed to catch a kijang (Muntiacus muntjak) and two wild boars (Sus scrofa) in their snares. They shared and distributed the wild boar meat to the families in the community (Figure 6) because they had already profited a considerable amount of cash from the kijang that was sold alive to their business associate, the Malay tauké.

Figure 6. Butchered wild boar meat to be distributed to the community (A) as they gather to have barbecue (B). Source: Photographed by the first author in Hulu Langat, Selangor, Malaysia on 24 and 27 November 2021.

The game trappers could have in fact earned additional income by selling the extra wild boar meat too since it is usually sold for RM6 per kilogram to fellow Orang Asli members, but instead, they decided not to. The warm smiles and shared happiness that are felt as the community gather to share game meat while they enjoy a little barbecue with one another meant more than some extra cash (Til, 2021). Concepts like this are commonly found in many indigenous communities around the world with their idea of redistribution, i.e., giving and sharing for the common good which is a relational sense that recognizes that there is far more to a “good” life than the material and financial gains (Pio and Waddock, 2021). Furthermore, sharing between community members can be seen as a principle of social organization to instil a set of reciprocal obligations that strengthen bonds in the community (Nadasdy, 1999). Perhaps, this social value of sharing with the community that is still maintained is among the factors that prevent oneself from taking excessively from the land as well since the land is considered an integral part of the community itself.

If being part of the community can foster the human–environment relations that consider the forest as part of, as well as the foundation of the community itself, maintaining a sense of community can at the same time be regarded as ensuring forest conditions. Meanwhile, it is evident from urban environments that as society progresses toward modernity, humans have become increasingly individualistic. A recent study by Komatsu et al. (2019) suggests that individualism might be the root cause of today’s environmental problems. Humans in more individualistic societies, they argue, are less likely to organize for collective proenvironmental action and are more inclined to care about personal rather than the social good. As a community that is flexible and not isolated from outside influences, it is not impossible that the sense of community in Kampung Tanjung Rambai gets eroded by modern ways of life exerting more and more influence on the community by the day. Forest management with the inclusion of the community in Tanjung Rambai can therefore be considered as one mechanism in which the sense of community within the kampung can be maintained.

Kerja kampung represents the multiple uses of forest resources by the Orang Asli for their subsistence. It utilizes the various goods and services provided by the forest that does not simplify forest ecosystems by maximizing the yield of a single preferred species. Rather, kerja kampung places more emphasis on the multiple provision of resources from the land, which requires the community as resource users to ensure that the forest ecosystem functions as it should, i.e., to produce various benefits that allow their kerja kampung to persist. This makes it consistent with the management focusing on resilience, emphasizing ecological processes rather than products (Berkes, 2012; Folke, 2016). Studies suggest that it is necessary to incorporate disturbance at a small-scale in managing resilience (Miller et al., 2010; Berkes, 2012; Folke, 2016; Johnstone et al., 2016; Nocentini et al., 2017; Hurteau et al., 2019; Newman, 2019). The use of various forest resources by the Orang Asli through their forest-based livelihoods can therefore be seen as a form of small-scale disturbance to the forest ecosystem that can be essential in ensuring forest resilience. Low-intensity productive use acts as a disturbance to forest ecosystems, which is necessary to provide ecosystem renewal and maintenance of system resilience, consequently, making kerja kampung suitable for the management of resilient forest ecosystems.

Managing resilient forests can go hand in hand with the Orang Asli’s kerja kampung because it does not treat land as mere commodities and therefore does not extract resources excessively. With the current relationship between the community and the land resulting from their long-term engagement with it, as well as with their maintained sense of community, the people of Tanjung Rambai are in the least likely position to exploit their land. It is precisely this relationship that makes kerja kampung distinct from other land resource derivations that have no historical and cultural bonds between the user and the resource being used. Incorporating kerja kampung in forest management will position the community as resource users as well as resource managers themselves, not in isolation or separation. By being immersed in the environment in which they manage and utilize, it is expected that the information gained through resource use can expand the knowledge base necessary for long-term planning and decision-making in the sustainable management of the forest aimed at resilient social–ecological systems.

However, the extent to which kerja kampung disturbs the forest ecosystem needs to be assessed to ensure they remain within resilient limits. For instance, there are several disturbances posed to the forest ecosystem in searching for wild honey of the stingless bee honey species alone (Figure 7). The people who participate in the kerja kampung need to work in a group and venture into the forest to look for the stingless bee’s nest. In doing so, they open small roads in the forest by slashing the dense shrubs and young trees with their machetes. These roads not only serve their sole purpose for humans but also provide access for wildlife to pass through, as well as allow plants on the forest floor to grow with less competition and more access to natural light. When the group arrives at the location where the stingless bee’s nest is, which is usually inside hollow trees, they observe the nest for some time. Only after several days, they would come back to the site with more people involved to ease the work and bring the hollow tree with the bee’s nest inside back to the kampung. Stingless bees play important roles in the forest ecosystem, and their removal will surely disturb ecosystem functions to some extent. They are major pollinators of wild and cultivated plants (Rismayanti et al., 2015; Gonzalez et al., 2018; Atmowidi et al., 2022), so their removal from the environment will disrupt the fruiting of plants that require their role in its process. As a result, the forest’s wildlife that relies on the fruits produced by those plants will also be impacted, and the Orang Temuan themselves might also be indirectly dependent on the stingless bee’s role for the outcome of their other sources of income like the annual durian harvest season. How much disturbance this particular kerja kampung has will depend on how often they are carried out, which depends on the market demands requested by the tauké. Throughout this study, there have been two events of harvesting wild honey of the stingless bee species by two different groups. One group sold theirs to a tauké who requested it and the other for personal consumption.

Figure 7. (A) A. Embong with his children cutting the hollow tree where the stingless bee’s nest is (A), and the stingless bees inside their nest (B). Source: Photographed by the first author in Hulu Langat, Selangor, Malaysia, on 23 November 2021.

Even though the Orang Temuan has been harvesting wild honey for generations and its sustainability has been empirically tested, applied, contested, and validated throughout time, the bee ecosystem is also affected by changes in environmental conditions that span beyond the confines of the kampung and their people. Slight temperature and weather pattern changes due to climate change, for instance, might have already impacted the bee ecosystem in a certain way. Further disturbance by the Orang Temuan’s kerja kampung can therefore worsen the situation or rather serve as a disturbance that is needed to ensure the bee’s resilience. Such as in the case of James Bay Cree in Berkes (2012) study, where not only the overuse of beavers can lead to their drop in productivity but so does underuse. To find out further in the context of Orang Temuan’s wild honey harvest, however, is beyond the scope of this study. This study points out that despite the Orang Temuan of Kampung Tanjung Rambai not currently being involved in the officially recognized forest management, their lives are inherently forest management themselves that continue to shape and are shaped by the forest ecosystem. Working in collaborative measures across multiple disciplines and involving the Orang Asli communities regarding how much disturbance will impact the ecosystem resilience is highly needed because even without official recognition, they are forest managers nonetheless.

Kerja kampung does not only imply the community’s physical proximity to the land but it is also influenced by the spiritual closeness to it. The spiritual relationship between the community and the land is based on the beliefs they profess, which guide the community’s day-to-day conduct and pose boundaries in certain aspects of their life. As animists, the people in Tanjung Rambai believe that the physical environment embodies spirits, some of which are the incarnation of their ancestors or moyang, to use their term. This belief exerts influence on many aspects of their lives, governing their attitude toward the land.

For instance, on numerous occasions when we heard the screeching sounds of an eagle soaring above, some would respond with a gaze to the sky and utter words suggesting that they have heard their moyang’s call. When asked, they explained how they cannot actually communicate with eagles but they believe that it was their moyang watching over them. According to Til (2021), the eagle’s call may signal heavy rain or it may signal that the snare traps they have set had caught something. The meaning varies depending on the context of what the people are doing at that time. They do not know for sure, other than believing that it is necessary to heed such a phenomenon as a sign. Although it can be difficult for us to fathom, such beliefs can simply be regarded as something that makes people wary of their surroundings, which is indispensable when working in uncertain environmental conditions, like the forest. In addition, associating their ancestors with the land can also be regarded as preventing oneself from doing any kind of harm to their environment and establishing respectful relationships with nature, as though children behaving to their elders.

There are also certain taboos in the community that poses restrictions in various aspects of their lives. For instance, the elders advised us not to say the word harimau (tiger) whenever we are in the forest. One should substitute with the term “orang tua bukit” which literally means “old man of the hill” (Embong, 2021c). This can be deemed as an expression of respect for the forest’s top predator. Upon being asked whether the people are afraid of tigers, they were in fact very confident that they will not be harmed because their moyang is watching over them, especially if they stick to the norms in the forest. Among the norms in question, one should not imitate the sounds of animals in the forest because it is considered as being disrespectful to their moyang. The rational interpretation of such a norm could be that not allowing oneself to imitate the sound of animals in the forest is to limit unnecessary noise that may trigger the tigers’ hunting senses, thereby avoiding tiger attacks. Whatever the reason behind it though, it has been adhered to as a code of conduct handed down by their predecessors. As irrational as it may sound, attributing human traits to non-human entities such as the land and animals, or in other words anthropomorphizing, may allow oneself to treat non-human entities in a more considerate manner. Perhaps, not everything needs to be rationalized so long as it has been proven to work. When things are going well, it makes perfect sense to simply persist in what has been practiced by the community even though in actuality there is more to it than meets the eye. In real-life situations that require assurance to sustain, rationalizing what has been proven to work seems less essential than sustaining in itself.

Having a spiritual connection to the land can also be linked to the community’s natural resource management which encompasses the authority system of rules for resource use. Since the forest is associated with ancestral spirits, people cannot arbitrarily take from the forest. When they eventually depart from this world and their spirit is embodied in the land as moyang for the succeeding generation, the land becomes their final resting place. As such, their idea of an afterlife and paradise is closely related to lush green forests which makes a degraded forest incompatible with such a belief (Embong, 2021c). Honoring their moyang means respecting the forest in which they lie and treating the forest with care as it will also be their final resting place when they become the moyang for succeeding generations. This spiritual connection allows the community to have prudence in utilizing forest resources. Indeed, even their kerja kampung is governed by such spiritual connection. They guide the community’s conduct in the kebun or dusun as well, which can be regarded as the land management system of the forest.

The Orang Temuan’s labor in the kebun and the trees they plant in the dusun may not yield immediate returns and they might not even reap the harvest in their lifetime, but the sweat they put into is intended for those who come after them (Embong, 2021c). This further implies the right to resources in the community that is based on heredity. Therefore, the forest, kebun, and dusun can be considered land management systems that revolve around the notion of sustainability. Firstly, because they believe that the land will become their final resting place that should not be degraded, and secondly because they consider resource use for the next generations to come. As long as the spiritual connection that underlies the human–environment relationship in the community is well preserved, it is almost certain that their forest-based lives are within the limits of sustained environmental conditions.

Another taboo in Kampung Tanjung Rambai is related to the food taboos. Although the Orang Asli are widely known as people who eat a wide variety of bush meats as opposed to the majority of Malay Muslims who have certain restrictions in their diet, the people of Tanjung Rambai do not eat tapir meat. It is believed that the meat is bad for them and may cause itching all over the body as if the meat is poisonous or has some kind of evil spell (Aling, 2021). Food taboos among the people are also related to their beliefs about the presence of spirits. If a person turns ill after eating something, they would believe that an evil spirit has caused the illness and can be cured with jampi (incantations) that are done by the dukun (shaman) rather than seek medical help at the hospital. Therefore, it is not advised to go and take forest products to eat at will. One needs to ask permission from the moyang beforehand to give them safety and protection from evil spirits, which can be done silently in their hearts (Aling, 2021; Embong, 2021c). Indeed, beliefs that inhibit certain actions deter people from acting frivolously toward their environment. Aside from that, however, it can also be in line with conservation efforts and may serve as a social function in the management of natural resources (Boedhihartono, 2017; DeRoy et al., 2019; Jessen et al., 2022), such as the taboo of eating tapir meat that can spare the tapirs from being hunted and consequently support the Malayan tapir’s conservation efforts since the species have been categorized as endangered by the IUCN (Traeholt et al., 2016). Managing the forest would not be effective without taking into account what the forest means to the very people who live in and depend on it.

The current social relationship in the community is close enough to ensure that the people live their lives according to the values of their beliefs mentioned above. Aling (2021) stated that those who deviate will be subject to social sanctions. In a fairly tight social environment where everyone knows one another, social sanctions are really something to be avoided. Even though nowadays there are some of the younger generations who do not take spiritual aspects seriously, they nonetheless practice what they are traditionally accustomed to. Over time, however, it is possible that the aforementioned beliefs can be eroded and taken over by the dominant culture from the outside if not properly acknowledged, reinforced, and maintained. For example, since the advent of electricity in recent years has enabled the use of smartphones, many of the younger generations have been introduced to YouTube and online games, which can certainly change their outlook on life.

Likewise in Thailand, there is a contrast between the older and younger generations regarding spiritual beliefs, whereby the younger ones tend to take it less seriously (Chunhabunyatip et al., 2018). The issue is addressed, among others, through education at the village’s primary school that teaches the local cultures’ heritage and values. Yet, on the contrary, the Orang Asli children in Malaysia are rather taught mainstream culture in schools where their sense of exclusion is exacerbated by insults from the non-Asli students (Renganathan, 2016). Many children in Tanjung Rambai have shown reluctance to go to school whenever the school bus comes by to pick them up in the early mornings. They often make excuses to skip school, perhaps because they feel like they do not belong at a place that pushes them to intermingle with contrasting cultures and lifestyles that tend to discredit theirs (Aling, 2021). The Orang Asli’s cultural identity should have been maintained by encouraging the children to be proud of their culture and teaching them about their cultural traditions and history through an inclusive education system that is grounded in the local contexts of diverse Orang Asli communities. As the biophysical and sociocultural components of social–ecological systems are linked (Gavin et al., 2015), sustaining the Orang Asli’s culture with their unique set of local values and relationship to the land can be expected to sustain the forest on which their cultures and societies depend.

This study intended to explore the relevance of involving the Orang Asli in Malaysia’s forest management. Their relevance is considered through the current relationship with the forest. In reference to the findings, the case in Kampung Tanjung Rambai confirms that the Orang Asli still maintains a relationship with the land beyond that of people and place as a mere commodity. The relationship in question is two-way, namely what the community gets from the land and what the land gets in return. The land provides natural resources to the community and through their derivations, the community becomes increasingly knowledgeable and familiar with it over time, which thus shapes the values that make up their worldviews. Furthermore, this study found that the sense of belonging to a community that is still present in the kampung can enable the community to have reciprocal obligations to its natural and social environment. This can be compatible with community-based and collaborative forest management that is still under-explored in Malaysia. Orang Asli communities, like those in Kampung Tanjung Rambai, should be recognized as having the qualities of potential partners and able to complement and expand the information base needed in forest management.

On the other hand, this study argues that Orang Asli’s kerja kampung can be regarded as a human–environment relationship that serves a similar purpose as a small-scale disturbance to the forest ecosystem, which is considered necessary for managing resilience. However, this study is limited to pointing out the disturbance that kerja kampung poses on the forest ecosystem without being able to assess the extent of such disturbance to ensure ecosystem resilience. To do so requires experts from various fields beyond the authors’ expertise. This highlights the need and opportunity for future collaboration and partnerships involving scientists, the state, and private enterprises. By doing so, the Orang Asli’s wellbeing can be prioritized through collaborative measures and co-management arrangements that emphasize improving their kerja kampung without compromising forest ecosystem conditions. Meanwhile, the impacts of their kerja kampung and the extent of their disturbance can simultaneously be assessed and monitored to devise management and long-term planning that aptly suits to adapt to the community’s local social–ecological contexts.

In addition, forest management with the inclusion of Orang Asli can also serve as a sustainable development strategy that is in line with their aspirations to preserve their ancestral forestlands. Nonetheless, these arguments do not seek to position the Orang Asli and the Orang Temuan of Tanjung Rambai, in particular, as “high priests” of sustainable resource use and managers. Rather, they are seen as potential partners and collaborators in the research-management nexus to focus on feedback and iterative learning in forest management. Neglecting their dependence on the forest and how such dependence may shape and alter the forest, and how they are shaped by the changes in forest ecosystems in return, would fail to grasp and therefore manage forests as an integrated and interrelated social–ecological system.

Forests have contributed immensely to Malaysia’s development and economic growth, yet the Orang Asli who have resided in forest ecosystems for many generations remains one of the poorest groups of people in the country. The Orang Asli of the Malaysian Peninsular has largely been excluded from the conventional management of Malaysia’s forests, which results in inequitable benefits and a series of environmental degradation that adversely affects their wellbeing. Meanwhile, in the neighboring countries, local and indigenous forest-dependent communities are increasingly being engaged in collaborative arrangements to ensure livelihood qualities and forest ecosystem conditions. Aligning forest management with sustainable development that favors the Orang Asli is therefore highly needed while there is still time. This study suggests that the Orang Asli still living in proximity to and depending on the forest in many ways pose small-scale disturbances to forest ecosystems with their kerja kampung, which could be essential in maintaining social–ecological resilience. We propose incorporating their kerja kampung in managing forests as complex social–ecological systems to achieve sustainable development goals that are in line with the aspirations of the Orang Asli.

Just like ecosystems, cultures are also dynamic. They experience shifts in structure and composition that are affected by many factors, which ultimately affect the way they function. The cultures that shape the human–environment relationship in Kampung Tanjung Rambai can therefore change for the better or worse. Not taking into account the dynamic changes in their culture and its impacts on the structure, composition, and function of the forest simply means that the impacts of social–ecological change are disregarded. Incorporating Orang Asli’s perspectives for impactful research and effective management should not be seen as introducing new players to what already exists, but it should instead be perceived as creating space for new possibilities, which may be key to solving the complexities of social–ecological change in the context of Malaysia’s forests. This study concludes that it is not too late to invite the Orang Asli to the negotiating table for better managing the forest through more equitable and inclusive arrangements.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

This study was approved by the Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli (JAKOA/Department of Orang Asli Development) on behalf of Malaysia’s government agency entrusted to oversee the Orang Asli affairs. Informed consent was obtained prior to the commencement of fieldwork, including permission for publication of all photographs, as well as participants’ consent to reference their real names as equal partners in the manuscript. The official document regarding research approval by JAKOA is available upon request.

MD developed the methodology, conducted the study, analyzed the data, and also wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AA provided the research fund and supervised the study. ZS supervised the study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research has been supported by the UKM through research grant: SK-2022-015.

We would like to thank JAKOA for granting permission to conduct this research. We also thank Pak Yayan Indriatmoko for connecting us to the people of Kampung Tanjung Rambai. Sincere gratitude was conveyed to the people of Kampung Tanjung Rambai, especially to the extended family of Arwah Embong.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abas, A., Aziz, A., and Awang, A. (2022). A Systematic Review on the Local Wisdom of Indigenous People in Nature Conservation. Sustainability 14:3415. doi: 10.3390/su14063415

Abraham, D. N., and Ng, J. (2021). First on Land, Last in Plan: The Orang Asli as Key Players in Forest Rehabilitation, Management and Conservation Practises. Planter 97, 543–552.

Aiken, S. R., and Leigh, C. H. (2011). In the way of development: Indigenous land-rights issues in Malaysia. Source 101, 471–496.

Alam, M. J., Nath, T. K., Dahalan, M. P. B., Halim, S. A., and Rengasamy, N. (2021). “Decentralization of forest governance in Peninsular Malaysia: The case of peatland swamp forest in North Selangor, Malaysia,” in Natural Resource Governance in Asia, eds R. Ullah, S. Sharma, I. Makoto, S. Asghar, and G. Shivakoti (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 13–26. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-85729-1.00002-5

Aling, A. (2021). Orang Asli Temuan. Lives in Kampung Tanjung Rambai, Hulu Langat, Selangor, Malaysia. Pers. commun.

Amnesty International (2018). The Forest is Our Heartbeat: The Struggle to Defend Indigenous Land in Malaysia. Sarawak: Amnesty International.

Atmowidi, T., Prawasti, T. S., Rianti, P., Prasojo, F. A., and Pradipta, N. B. (2022). Stingless Bees Pollination Increases Fruit Formation of Strawberry (Fragaria x annanassa Duch) and Melon (Cucumis melo L.). Trop. Life Sci. Res. 33, 43–54. doi: 10.21315/tlsr2022.33.1.3

Azima, A. M., Lyndon, N., Sharifah Mastura, S. A., Saad, S., and Awang, A. H. (2015). Orang asli semelai: Conflict of defending land ownership rights. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 6, 63–69. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n4s3p63

Aziz, S. A., Clements, G. R., Rayan, D. M., and Sankar, P. (2013). Why conservationists should be concerned about natural resource legislation affecting indigenous peoples’ rights: Lessons from Peninsular Malaysia. Biodivers. Conserv. 22, 639–656. doi: 10.1007/s10531-013-0432-5