- 1School of International Business, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China

- 2Jiyang College, Zhejiang A&F University, Hangzhou, China

Strong judicial support is an important guarantee for a country’s environment to achieve good governance. This paper utilizes a multi-period difference-in-differences approach to examine the impact of environmental justice reform, represented by environmental tribunals, on corporate green innovation and its underlying mechanisms. It is found that environmental courts can effectively promote green innovation in enterprises, and their effect on “substantive green innovation” is more significant than that on “strategic green innovation”. The environmental court is divided into the environmental resources trial court and the environmental resources panel court, and the trial court has a more pronounced effect on promoting corporate green innovation than the environmental resources panel court. The establishment of environmental protection courts can improve the efficiency of regional environmental justice, enhance the government’s awareness of environmental protection, and increase the cost of illegal activities by enterprises, thereby promoting corporate green innovation. The promotion effect of environmental courts on corporate green innovation is more significant in regions with non-state-owned enterprises, better legal environments, and lower levels of industry competition. The main findings still hold after considering robustness tests, such as the endogeneity of environmental court establishment. The study suggests that environmental judicial specialization has a positive impact on corporate green innovation, and that the reform of environmental judicial specialization should be continuously deepened to provide useful insights for the construction of the ecological rule of law and the green transformation of enterprises.

1 Introduction

In 2020, China proposed the strategic goals of achieving Carbon Peak by 2030 and Carbon Neutrality by 2060. This demonstrates the government’s efforts to promote the construction of eco-cities and a resource-saving, eco-friendly, and green development system to cope with global climate change. Green technological innovation is considered crucial for achieving Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality, as well as for enterprises to coordinate economic development and eco-environmental protection, ultimately accomplishing the sustainability of low-carbon development.

The Chinese government has established several policies and regulations over the decades for the goal of promoting environmental and economically sustainable development. Prior to 2018, China had been adopting a sewage charging system to regulate corporate pollution, tackling the issue of environmental pollution externalities. However, at the macro level, due to the overly uniform charging standards, the adoption of unified charging standards for pollutants of different concentrations has instead stimulated the motives for some enterprises to increase emissions (Zhang et al., 2015). Furthermore, the amount of sewage charges collected is less than the fiscal expenditure on environmental protection, with a poor implementation effect. According to statistics, the national general budget allocated 1.76 trillion yuan for energy conservation and environmental protection expenditures from 2011 to 2015, averaging 352 billion yuan per year. However, during 2003-2015, China generated a total revenue of 2.115 trillion from pollutant discharge fees, averaging 162.7 billion per year, indicating a significant difference in scale (Zhou et al., 2023). At the micro level, during the collection of sewage fees, officials may collect arbitrarily or fail to pay what is due. Since 2018, China has been formally implementing the Environmental Protection Tax Law, which partially alleviated the issues caused by sewage fees. However, in practice, the traditional administrative and legal governance system is relatively inefficient in dealing with complex environmental issues involving water, land, air, and other environmental factors.

In addition, local governments are prone to two extremes in managing pollution. On one hand, they may prioritize protecting local economic development and therefore protect or even condone enterprises in certain highly polluting industries that make significant contributions to the local economy. On the other hand, in some regions, environmental governance has become a mere show project of central environmental supervision due to the incentive mechanism of political promotion. In order to complete environmental tasks, extreme measures are taken, such as directly ordering enterprises to suspend operations, which can negatively impact their normal functioning. The regulatory behavior of local governments regarding the environment not only goes against the central government’s original environmental policy goals but also harms social and public interests. Therefore, China’s environmental pollution governance still lacks a long-term mechanism, and the key to promoting the normalization of pollution governance lies in the construction of the rule of law (Fan and Zhao, 2019). The rule of law is the foundation of environmental pollution governance, effectively ensuring the implementation of environmental protection policies. Enterprises are typically the main source of environmental pollution, and green innovation is a crucial means for them to reconcile the conflicts between production and the environment, thereby promoting sustainable economic development. The transformation of enterprises towards sustainability has become crucial in balancing environmental protection and economic development. Green innovation can achieve sustainability, enhance economic growth potential, reduce carbon emissions, and minimize damage to climate change and biodiversity, making it a key factor in corporate green transformation (Peng et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2024). To address environmental pollution caused by corporate behavior, power abuse and the failure of government to take actions, it is necessary to improve the judicial system. The establishment of environmental courts provides the necessary supervision and regulation of these behaviors, which truly achieves the internalization of enterprise pollution costs.

Promoting green innovation in enterprises has become a major academic focus. Currently, in the context of environmental protection being a consensus, green innovation becomes an important way and a necessary measure in China to build a resource-saving and environmentally friendly society for sustainable development (Yin et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2024). As public environmental awareness improves, enterprises must take on environmental responsibilities while still making profits. Green innovation is seen as a business opportunity by many enterprises. (Huang and Li, 2017; Gao et al., 2024b). However, there is a high degree of substitutability between green and non-green technologies. In the absence of external intervention, most enterprises are unwilling to actively engage in green innovation due to market scale effects and the initial productivity advantage of non-green technologies, leading to increasing levels of environmental pollution. Therefore, achieving green innovation solely through enterprises and the market is challenging (Wang et al., 2022a; Jiang et al., 2023). Accordingly, promoting corporate green transformation requires environmental regulation. Scholars have examined various factors, including environmental regulation (Wakeford et al., 2017; Deng et al., 2021), regulatory intensity (Ziegler and Nogareda, 2009; Luo et al., 2021), government subsidies (Guo et al., 2023), and public opinion (Peng et al., 2021), that exert regulatory pressure on corporate green innovation. Scholars have also examined the relationship between environmental tribunals and environmental governance, including their impact on industrial pollutant emissions (Fan and Zhao, 2019), corporate environmental expenditures (Zhang et al., 2019), and investments (Jinjarak et al., 2021).

Three conclusions can be drawn from the study above. Firstly, environmental regulation inhibits corporate green innovation. It will internalize the external environmental costs of corporate production and operations into private costs, thereby increasing the burden on companies. (Jaffe and Stavins, 1995). Strict adherence to environmental regulations can result in increased operating costs, which may reduce the profit margin of the enterprise. As the total resources of the enterprise are limited, a decrease in profit margin can inevitably lead to a reduction in the enterprise’s R&D investment, hindering its level of innovation and sustainable development. (Yu and Li, 2021). Secondly, environmental regulation can enhance the level of green innovation due to their incentive effect on enterprises. According to the Porter Hypothesis, companies can enhance their production and sales capacity of environmentally friendly products through green innovation, which gives them a competitive advantage in the market. This, in turn, motivates companies to strengthen their research and development efforts, improve their emission reduction technologies, and promote green technological progress (Li et al., 2018; Xie, 2021). Thirdly, the literature suggests a U-shaped relationship between environmental regulation and green innovation. Over time, there is an inflection point between the two (Peuckert, 2014; Li, 2017). As environmental regulation enhances, the impact of environmental regulation on green innovation shifts from an inhibitory to a facilitative effect (Zang and Zhang, 2015).

Specifically, our research differs from previous studies in two key aspects. First, while most earlier studies focus on macro or micro levels, this paper examines the impact of environmental courts on green innovation from a micro-level perspective, specifically at the enterprise level. Second, we further differentiate between trial courts and collegial courts within the environmental court system, investigating their respective impacts on green innovation. Since trial courts and collegial courts handle different cases and impose varying penalties on enterprises, the resulting effects on corporate innovation also differ.

In conclusion, previous literature has primarily focused on analyzing the relationship between environmental regulation and corporate green innovation at the macro and industrial levels in China. However, there still exists a lack of analysis at the micro-level regarding the impact of environmental courts on corporate green innovation. The environmental tribunal serves as a policy experiment to test judicial capabilities. It provides an ideal opportunity to examine the impact of the rule of law construction on corporate green innovation.

This paper has three main contributions. First, most studies focus on the macro level, analyzing the relationship between green regulations and green innovation. Our study examines the influence of local environmental tribunals on corporate green innovation from a micro perspective. The environmental courts are divided into tribunals and collegiate panels to verify their impact on green innovation. This helps to understand its operational mechanism. Second, we examine the role of environmental tribunals in promoting green innovation from three perspectives: local environmental judicial efficiency, government environmental awareness, and corporate illegal costs. This analysis provides a deeper understanding of the impact of environmental tribunals on corporate innovation. Finally, we study the heterogeneity of the impact of environmental tribunals on corporate green innovation from four perspectives: enterprise nature, geographical location, level of the rule of law, and industry competition. Using data from 341 cities in China from 2007-2021, this paper matches the green innovation of local enterprises and uses a multi-period DID model to evaluate the impact of environmental tribunals on corporate green innovation. Our study provides a new perspective on how Chinese enterprises can undergo a green transformation, which can serve as a reference for other countries to achieve green and sustainable development.

The remainder of the paper is set out as follows. Section 2 introduces the institutional background and development overview of the environmental tribunal. Section 3 presents theoretical analysis and research hypotheses. Section 4 introduces the model and data. Section 5 demonstrates the benchmark results of empirical evidence of environmental tribunals on corporate green innovation. Section 6 examines how environmental tribunals impact corporate green innovation. Section 7 offers additional analysis. The final section then draws some conclusions and recommendations from this study.

2 Institutional background and development

As environmental pollution has become a focus of concern for both the government and the public, severe pollution issues have led to a significant increase in legal disputes. According to the China Environmental Justice Development Report (2022), in 2022, courts nationwide accepted a total of 273,177 first-instance environmental resource cases, representing a year-on-year increase of 12.89%. Since 2005, the number of environmental disputes in China has been increasing at an average annual rate of 30%, indicating a time of explosive growth (Wu et al., 2020). Prior to the establishment of environmental courts, China’s environmental judiciary faced two main challenges. Firstly, environmental cases typically require specialized knowledge, which ordinary personnel often lack, making it difficult to render effective judgments. Secondly, environmental pollution cases involve three categories of law: administrative, civil, and criminal. Each category has a wide range of implications and is generally complex. Separate trials of each category of cases would greatly reduce the efficiency of the judicial process. Thus, establishing environmental court can effectively solve these problems. The environmental court has professional talent and can adopt a series of alternative judicial systems to achieve judicial innovation and improve the efficiency of environmental justice. Therefore, the establishment of environmental courts is a natural step, with emerging environmental disputes around the country, and as a long-term mechanism to leverage specialized adjudication and enforcement capabilities.

The establishment of environmental courts has a long history. It is considered an effective way to improve judicial efficiency, reduce environmental pollution, and carbon emissions (Walters and Westerhuis, 2013). Since the 1950s, some countries have begun to explore the system of environmental courts by setting up independent environmental resource adjudicative authorities specifically for environmental pollution cases (Almer and Goeschl, 2010). In 1980, New South Wales, Australia established the world’s first specialized environmental high court, which was able to promptly handle judicial disputes and improve environmental governance efficiency (McClellan, 2009). Subsequently, countries such as Sweden, the United States, and New Zealand also started to establish environmental courts.

In the face of increasing pressure on carbon emissions and environmental governance, China has also begun to attempt to establish environmental courts. In December 2005, the State Council issued the Decision of the State Council on Implementing the Scientific Outlook on Development and Strengthening Environmental Protection. In the context of China’s institutional development, this was the first time that environmental public interest litigation was mentioned. However, this policy only outlines the basic principles and objectives of environmental protection without being legally implemented, thus having a limited practical impact. In November 2007, the first environmental court was established in Qingzhen City, Guizhou Province, China. In January 2013, China implemented the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China, which established the first system of environmental public interest litigation at the legal level. In July 2014, the Environmental Resources Trail Courts was officially established in the Supreme People’s Court. Accordingly, several regions have established institutions for environmental resources litigation, marking the official launch of the specialization of environmental judiciary in China. In January 2015, the promulgation of the new Environmental Protection Law further perfected the legal provisions regarding environmental public interest litigation. In July 2015, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPCSC) officially passed the Decision on Authorizing the Supreme People’s Procuratorate to Conduct Pilot Projects of Public Interest Litigation in Certain Regions. This decision made prosecutorial authorities the main body of public interest litigation and required the pilot work to be carried out in some cities in 13 provinces. In June 2017, the NPCSC amended the Civil Procedure Law and the Administrative Procedure Law, formally implementing the public interest litigation system nationwide. This system includes administrative public interest litigation and environmental civil public interest litigation, with the parties involved being prosecutorial authorities, social organizations, and individuals.

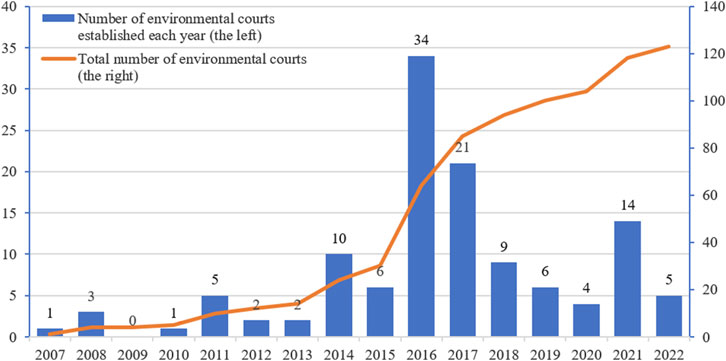

The data released by the Supreme People’s Court of China shows that, as of the end of 2021, a total of 2,149 specialized environmental resource adjudicative organs and judicature organizations have been established nationwide. It includes 649 environmental resource tribunals (including the Supreme People’s Court, 29 high people’s courts, divisions of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, 158 intermediate people’s courts, and 460 grassroots people’s courts), 215 people’s courts, and 1,285 trail teams (collegial panels). The environmental court uses a “Three-in-one” trial model, where administrative, criminal, and civil cases related to environmental resources are all under the jurisdiction of the environmental court for the trial of environmental public interest litigation events. In 2007, during the pollution incident in Hongfeng Lake in Guiyang, the environmental courts introduced experts to assist enterprises in identifying problems and formulating rectification plans, urging them to make improvements. The environmental courts exercise exclusive jurisdiction over environmental cases within designated areas, which has to some extent addressed the deficiencies of environmental justice in pollution control. After a decade of development, the system for environmental public interest litigation has been continuously improved. It has been formed into an ecological environmental protection regulatory system that includes civil, administrative, and criminal public interest litigation, which safeguards ecological safety, social public interests and people’s health. Figure 1 displays a steady rise in the number of environmental protection courts in China, with the most significant increase occurring in 2016. This growth can be attributed to the NPCSC’s requirement for pilot projects to be carried out in some cities in 13 provinces in 2015, which led to the highest growth rate of 2016.

3 Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses

3.1 Theoretical analysis

Porter’s Hypothesis proposes that properly designed environmental regulations can trigger corporate innovation (Porter and Linde, 1995), leading to increased corporate productivity. Early studies on Porter’s Hypothesis primarily aimed to identify environmental regulatory indicators and assess the effectiveness of environmental regulation enforcement (Carrion-Flóres and Innes, 2010). With the introduction of Emissions Trading and Cap and Trade systems in Europe, the United States, and China, researchers have begun to focus on the impact of pollution trading rights and environmental regulations (Calel and Dechezleprêtre, 2016). Environmental pollution has negative spillover effects, while green innovation has positive spillover effects, creating a positive externality. Environmental courts can address this externality and remedy market failure by resolving the contradiction between public and private interests, increasing social welfare, and providing incentives for green innovation. Thus, the environmental courts, being a special system within the Chinese judicial system, have a significant impact on green innovation.

The Pegu’s tax principle suggests that internalization degree of costs in environmental courts has significantly increased compared to original environmental policies (Wang Y. et al., 2022). After the establishment of environmental courts, firms are faced with two choices: maintain their original levels of pollution emissions, which may result in public prosecution, high litigation costs, and reputational damage, or increase investment in environmental protection to avoid lawsuits, promote green transformation, and produce cleaner products. Enterprises are the main subjects of market activities, providing a variety of values while also generating externalities for the outside world. Negative externalities are particularly severe for heavily polluting enterprises. The establishment of environmental courts can help enterprises transform their initial ideas and focus more on the long-term benefits of green transformation. At the same time, the enforcement of environmental court resolutions is stronger and more strictly regulated. Enterprises are increasingly recognizing the importance of environmental protection and pollution control due to additional costs arising from litigation and reputation. Improving corporate environmental performance and enhancing environmental awareness are some of the benefits (Liu and Xiao, 2022). The establishment of environmental courts has led to increased costs of non-compliance for enterprises. When the costs of violating the law exceed the costs of pollution control incurred for actively improving the environment, firms are more likely to invest in environmental protection (Tian et al., 2022).

3.2 Research hypotheses

Once an environmental court is established, it will be difficult to abolish. Enterprises’ actions to reduce emissions and control pollution will consider both short-term benefits and long-term costs. Green innovation is a crucial factor in long-term pollution control, and the use of green technology can reduce pollutant emissions. By improving the green production process or technology, it is possible to reduce the generation of pollutants at the source, achieve long-term emission reduction, enhance sustainable development capabilities, and improve the competitiveness of enterprises (Yu et al., 2021). According to the Porter Hypothesis, environmental courts can motivate firms to engage in green innovation, thus establishing a competitive advantage (Antonioli et al., 2013). In other words, if there is a reasonable environmental regulation system, firms will be compelled to innovate towards green practices and use this as a form of environmental management decision. In the long term, the benefits of green innovation outweigh the costs of governance incurred by firms in pollution control. Therefore, we proposed the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. The establishment of environmental courts will promote corporate green innovation.

Establishing environmental courts in regions can reduce local protectionism and indirectly encourage firms to increase R&D expenditure for green innovation by improving judicial efficiency. When local protectionism is severe, unprotected firms are less likely to pursue green innovation as their green patents may be infringed upon, and they may face a lower success rate in court (Liu et al., 2022). An independent environmental court system can strengthen the protection of intellectual property rights and ensure a fair competitive environment, thereby stimulating green innovation. By setting up an environmental court specialized in environmental resources, on the one hand, the court can train judges with professional backgrounds to be in charge of environmental cases, improving the accuracy of evidence collection in cases. For instance, utilizing a “Judge plus expert” model can decrease the likelihood of wrongful trials and miscarriages of justice, thereby enhancing the efficiency of judicial processing of environmental cases. On the other hand, a specialized judicial organ with centralized jurisdiction over environmental cases can adopt a special judicial system and make a series of adjustments for specific cases within the legal framework (Edwards, 2013). In practice, environmental courts have implemented a centralized trial mode that hears criminal, civil, and administrative cases related to environmental resources. This ‘Three in one’ trial model promotes close cooperation and a collaborative trial mechanism, unifying the judicial standards and criteria for environmental cases. It effectively standardizes the judicial procedures of environmental cases. By focusing on the trail of environmental pollution, the establishment of environmental courts ensures professionalism and enforcement, improving the efficiency and quality of handling environmental disputes and enhancing law enforcement capacity. Therefore, hypothesis 2 is proposed:

Hypothesis 2. The environmental courts enhance the efficiency of regional environmental justice, imposing the “hard constraints” on enterprises, and encouraging them to pursue green innovation.

The concern of local government for environmental governance will also impact corporate behaviors in pollution control. With the establishment of environmental courts in the region, the local government’s awareness of environmental protection is likely to increase (Jin and Chen, 2022). Environmental courts can improve the government’s awareness of environmental protection through two channels. Firstly, the establishment of environmental courts in a region indicates the central government’s emphasis on local environmental protection. This sets higher requirements for the environmental protection functions of the regional government, making them pay more attention to environmental protection. Secondly, enterprise pollution can directly or indirectly impact the environment that the public depends on for survival. A healthy environment has always been a fundamental demand of society. The level of public concern for environmental protection is reflected in public opinion and media coverage to urge the government to prioritize environmental protection. After the establishment of environmental courts in regions, socially conscious individuals are highly concerned about issues of environmental pollution generated by enterprises, whether for the protection of their own interests or out of a concern for the overall quality of the social environment beyond personal benefits. They use a variety of channels to pressure the local governments to prioritize environmental protection. The government exerts pressure on relevant firms through effective channels, supervising and punishing firms that cause environmental pollution, thereby transferring the pressure of environmental governance to local firms. Improving managers’ green cognition and the intrinsic motivation of enterprises to voluntarily undertake environmental and social responsibilities (Gao et al., 2024a). When firms face stronger government regulation, they will be more inclined towards green transformation (Huang and Zhang, 2018), which is beneficial for enhancing the level of green innovation in the long run. Therefore, we propose hypothesis 3:

Hypothesis 3. Environmental courts enhance environmental awareness of the government, adding a “soft constraint” to enterprises, and encouraging them to pursue green innovation.

The establishment of environmental courts will increase opportunities for environmental protection rights, indirectly raising the production and operation costs of enterprises, and forcing polluting firms to transition to green practices. Due to the increasingly strict environmental penalties, enterprises not only face high legal costs but also potential reputation damage and the risk of losing customers when an environmental pollution incident occurs. Therefore, they tend to undergo green transformation. Environmental courts have the potential to increase the costs of pollution for enterprises more directly than traditional judicial organs in the event of pollution incidents. The outcome of environmental courts’ handling of enterprises can also act as a deterrent, thereby expanding the scope of the rule of law and increasing public confidence in taking judicial protection initiatives in environmental disputes. The public will file more lawsuits against polluting enterprises, and the number of environment-related civil lawsuits will also increase significantly. In view of the above, the establishment of environmental courts will directly increase the environmental pollution costs of enterprises, which is an intangible control on their environmental pollution behavior. To mitigate legal risks, companies will enhance their production methods, implement pollution control equipment, and decrease environmental pollution through eco-friendly transformation. Therefore, hypothesis 4 is proposed:

Hypothesis 4. The establishment of environmental courts increases the cost of violations for enterprises, thereby promoting corporate green innovation.

4 Research design

4.1 Sample selection and data sources

This paper focuses on the intermediate environmental courts of Chinese prefecture-level cities as the research sample, excluding grassroots environmental courts. While the number of grassroots environmental protection courts is relatively large, their judicial and enforcement powers are mostly limited to county areas and are more influenced by grassroots governments. Furthermore, the professionalism of grassroots environmental courts needs improvement. Environmental resource cases require specialized and comprehensive judicial background due to their complexity and technicality. Grassroots courts encounter practical challenges in establishing specialized judicial institutions. Cases handled by intermediate environmental courts in prefectural cities are major disputes with wide-ranging impacts. Therefore, the disposal results pronounced by the environmental courts will have a deterrent effect on enterprises located in counties, which is more persuasive than that of the grassroots courts. Lastly, the establishment time of environmental courts at the county level and below is also difficult to verify, so we will not consider county-level environmental courts.

Intermediate environmental courts typically consist of four types: tribunals, circuit courts, collegial panels, and detached tribunals. The most common type established by intermediate and higher people’s courts is the environmental resources tribunals. This court has a fixed personnel composition and broad jurisdiction. Environmental courts may sometimes have jurisdiction and enforcement in different jurisdictions due to their standardization, specialization, and systematization characteristics. The other three types of environmental courts are temporary and often face the embarrassing situation of having many courts and few cases or even no cases to be heard at the beginning of establishment (You, 2018), resulting in a lack of professionalism and systematic mechanisms. Their operating scope and judicial enforcement capabilities are not as effective as those of the environmental resources tribunals. Therefore, this paper focuses on researching the environmental resources tribunals of the Intermediate People’s Court.

We use data from Chinese listed companies from 2007 to 2021 as samples, manually collecting and matching data from intermediate environmental courts in prefecture-level cities and corporate green patents to form the dataset for this paper. The data of the environmental courts comes from searching the relevant city data in the document of the 2021 China Environmental Resources Trials, released by the Supreme Court, and is manually collected and organized based on the official websites of various Intermediate Courts, Legal Daily, and related news reports. Green patent data is sourced from the CRNDS database and the Chinese Patent Database. The remaining data comes from CSMAR and Wind Database. We removed the samples of companies listed in the financial industry, ST, *ST, or PT, as well as those with missing data. Continuous variables were then trimmed at the 1% level on both ends. In the end, our study has a total of 31,342 company-year observations.

4.2 Variable definition and descriptive statistics

4.2.1 Explanatory variable

The establishment of environmental courts is the independent variable (Du) of this study. According to the principle of multi-period DID, if the region established an environmental court in the current year or earlier, Du is 1; otherwise, Du is 0. As of the end of 2021, the intermediate people’s courts established a total of 158 intermediate environmental resources tribunals. Meanwhile, manually collected data that can be used to prove was 147, including 125 environmental resource tribunals, 17 environmental resource collegial panels, and 5 circuit courts. The margin of error is about 7%, mainly due to the probability of omission when manually searching for city names and keywords such as “environmental resources tribunals.” Not all intermediate people’s courts will have official records or news reports after establishing environmental courts. These courts are likely to have relatively weak environmental governance capability and may not attract widespread media attention. The effectiveness of intermediate environmental courts should be a long-term mechanism widely followed by the public media, therefore, the impact of the unsearchable part on the sample regression is limited.

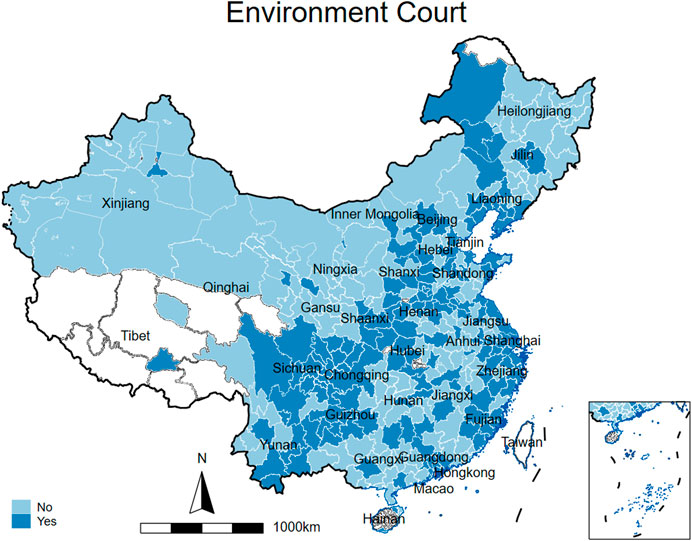

As shown in Figure 2, since the establishment of the first environmental court in China, most regions have set up environmental courts. Currently, 29 provinces and municipalities in China have environmental courts. However, the geographical distribution of environmental courts is mainly in the eastern and southern regions, where economically developed cities in China are also located. It shows spatial geographical consistency between the distribution of courts and economic development.

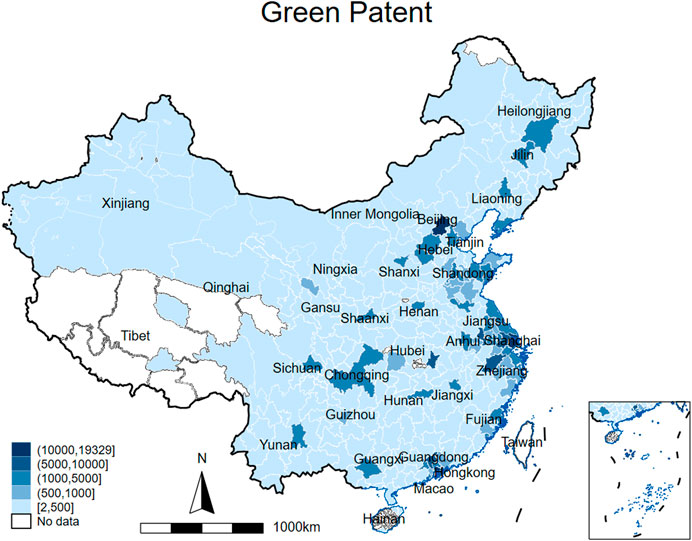

4.2.2 Dependent variable

Following the research of Fei Fan et al. (2020), corporate green innovation (Patent) is measured by the number of green patent applications. The number of green invention patents is considered as substantive green innovation, while the number of green utility-based patents is classified as strategic green innovation (Wurlod and Noailly, 2018). Figure 3 shows the geographical distribution of green innovation in Chinese enterprises, matching their corporate location with green patent data. The green innovation intensity is concentrated in coastal areas such as the Yangtze River Delta, and this distribution is similar to the actual economic development. After 3 decades of rapid development, most of the industrial transformation and upgrading in coastal areas, such as the Yangtze River Delta, has been completed. Industries with high emissions and energy consumption have shifted to central and western regions. Additionally, the eastern regions, with their abundant talent reserve and R&D resources, have laid a foundation for green innovation.

This article aims to differentiate between various green innovation behaviors driven by distinct motivations and to explore the impact of China’s environmental courts on micro-enterprise innovation and its underlying mechanisms. For companies influenced by China’s innovation policies, the anticipation of increased government subsidies and tax incentives leads to a significant rise in their patent applications, particularly for non-invention patents. The selective fiscal and tax support measures associated with these policies often compel companies to engage in “support-seeking” behavior, resulting in a surge in patent applications that prioritize “quantity” over “quality.” This phenomenon indicates that the Environmental Protection Tribunal may not effectively motivate enterprises to pursue substantive innovations that foster technological advancement and competitive advantages. Instead, the focus on increasing the “quantity” of innovations to “seek support” reflects a form of strategic innovation rather than genuine progress.

From this perspective, we categorize enterprise innovation behaviors into two distinct types: First, there is “high-quality” innovation behavior aimed at promoting technological advancement and securing competitive advantages, which we term substantive innovation. Second, there is “strategic innovation,” characterized by a focus on pursuing alternative interests and aligning with regulatory and government innovation strategies by emphasizing the “quantity” and “speed” of innovation.

4.2.3 Control variables

We select the following control variables based on previous literature (Fang and Shao, 2022; Yan et al., 2023): ① Firm size (Size), with the value of the natural logarithm of annual total assets. Generally, larger companies possess a greater capacity to acquire resources, which may influence their business strategies and performance, including their responses to environmental policies and their capacity for green innovation; ② State-owned enterprise or not (SOE), with a value of 1 for state-owned and 0 for others. The distinctions between state-owned and privately-owned enterprises often manifest in their property rights structures, resource acquisition capabilities, and business objectives; ③ The age of firm establishment (FirmAge), with the value of the natural logarithm of the current year minus the year of corporate establishment plus one. This logarithmic processing effectively eliminates the impact of scale on the results. This logarithmic transformation effectively mitigates the influence of size on the results. The establishment year serves as an indicator of a company’s development stage, with differences in resources, experience, and market position between newly established firms and mature enterprises likely affecting their behaviors and performance; ④ The firm’s capital structure (Lev), with the value of dividing total liabilities at the end of the year by total assets. Capital structure significantly influences financial decision-making, risk tolerance, investment behaviors, and how enterprises respond to external changes, including adapting to environmental regulations and pursuing green innovations; ⑤ The firm’s industry (Industry), according to the China Securities Regulatory Commission’s classification of industries in 2012 to divide into different industry codes. Different industries exhibit unique characteristics that may impact corporate behaviors and performance. For instance, technology firms may prioritize innovation more heavily than service-oriented businesses, which might focus on customer experience. Controlling for industry type enables researchers to identify and differentiate the factors that uniquely influence performance within specific sectors; ⑥ Return on equity (ROE), with the value of net profit divided by average shareholders’ equity. ROE is a crucial metric for assessing a company’s profitability, reflecting how effectively it utilizes shareholders’ equity to generate profits. By controlling for ROE, we account for differences in profitability across various firms; ⑦ CEO-chairman duality (Dual). If the chairman and general manager are the same person, represented as 1, otherwise as 0. The dual role is a significant aspect of corporate governance, influencing the company’s decision-making processes, power dynamics, and oversight mechanisms; ⑧ Management ownership ratio (Manho), this ratio indicates the percentage of shares held by management and reflects the alignment of interests between management and the company. When management possesses a higher shareholding ratio, they are typically more motivated to enhance company performance, as their personal wealth is closely tied to the company’s long-term success. In our analysis of green innovation capabilities, we consider the effects of management incentives and corporate governance structures to improve the accuracy and reliability of our findings; ⑨ Return on assets (Netp), the proportion of total profit to total assets, offering insights into how efficiently a company utilizes its assets to generate earnings; ⑩ Regional urbanization rate (Ur), this variable measures the proportion of the urban permanent population to the total population at the end of the year. It reflects the level of urbanization in a region, which can influence policy environments and economic opportunities; ⑪ Regional industrial structure (Ris), the proportion of added value of regional industry to total output as a representation variable of industrial structure. Different levels of urbanization and industrial structure can lead to varying policy environments; for example, urban areas may receive more economic development incentives such as tax breaks and subsidies. By controlling for Ur and Ris, we enhance the accuracy and reliability of our research; ⑫ Industrial development level (GDP), the logarithm of per capita gross domestic product. GDP serves as a vital indicator of the economic scale and market potential of a region or country. By controlling for this variable, we account for the impact of economic development and scale when analyzing corporate green innovation.

4.2.4 Descriptive statistics

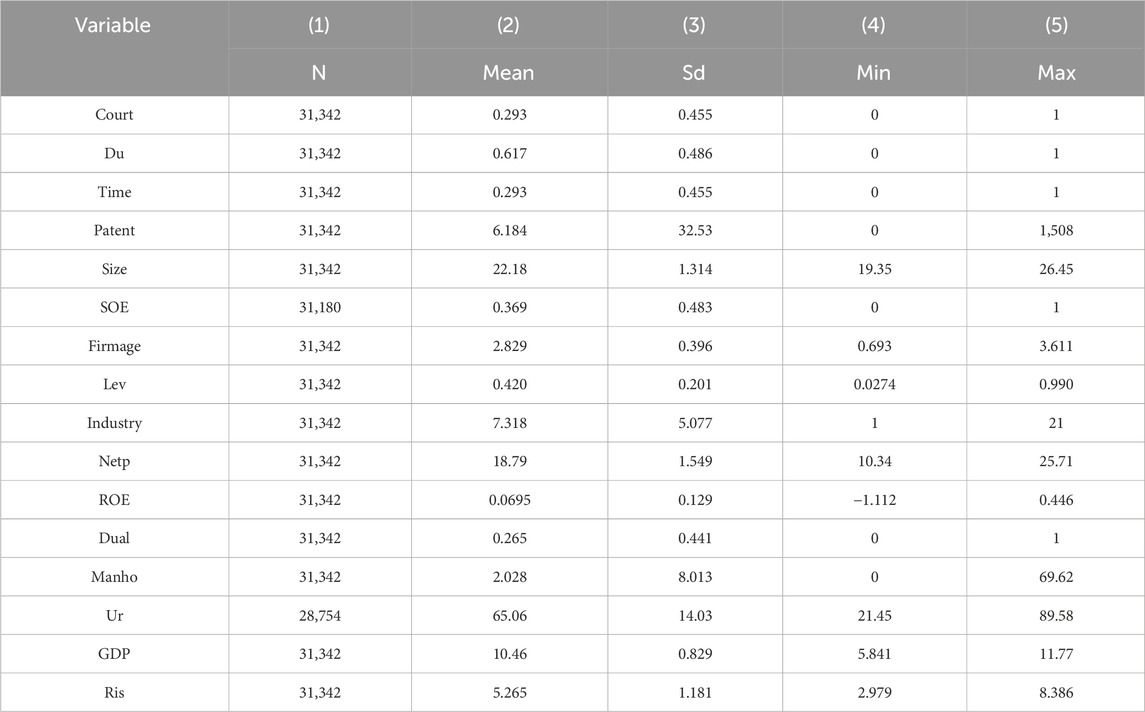

The average value of enterprise green innovation Patents is 6.184, with a standard deviation of 32.53. The minimum value is 0 and the maximum value is 1,508, indicating significant differences in the level of green innovation among enterprises. The average value of the policy variable Du is 0.617, which means that during the research period, approximately 62% of the regions where the enterprises are located have established environmental courts. This indicates that environmental courts have not yet become a widespread presence, but recent trends suggest that there will be more in the future. Statistical descriptions of all variables are shown in Table 1.

4.3 Modeling

Following the study of Kesidou and Wu (2020), this paper sets up prefecture-level cities with intermediate environmental courts as the treatment group, and those without environmental courts as the control group. Using a multi-period DID method, we construct a two-way fixed effect model as follows to test the influence of environmental courts on the green innovation capabilities of enterprises:

Patentit is an indicator that measures green innovation in enterprises, representing the number of green patents in city i in year t. The main explanatory variable is the policy dummy variable, which is the interaction term product of the city dummy variable and the time dummy variable, i.e.,

The primary objective of this article is to assess the effectiveness of the environmental court and its impact on corporate green innovation. The DID method allows us to quantify the changes that occur before and after the implementation of the policy, as well as to measure the differences in changes between groups affected by the policy and those that are not. This enables a robust evaluation of the policy’s actual effects. Controlling Confounding Factors: During the establishment of the environmental court, various external factors—such as economic cycles and technological advancements—may concurrently influence the research outcomes. The DID method effectively controls for these confounding variables by comparing the changes observed in the treatment group (those impacted by the policy) with those in the control group (those unaffected by the policy).

5 Empirical analysis

5.1 Baseline regression results

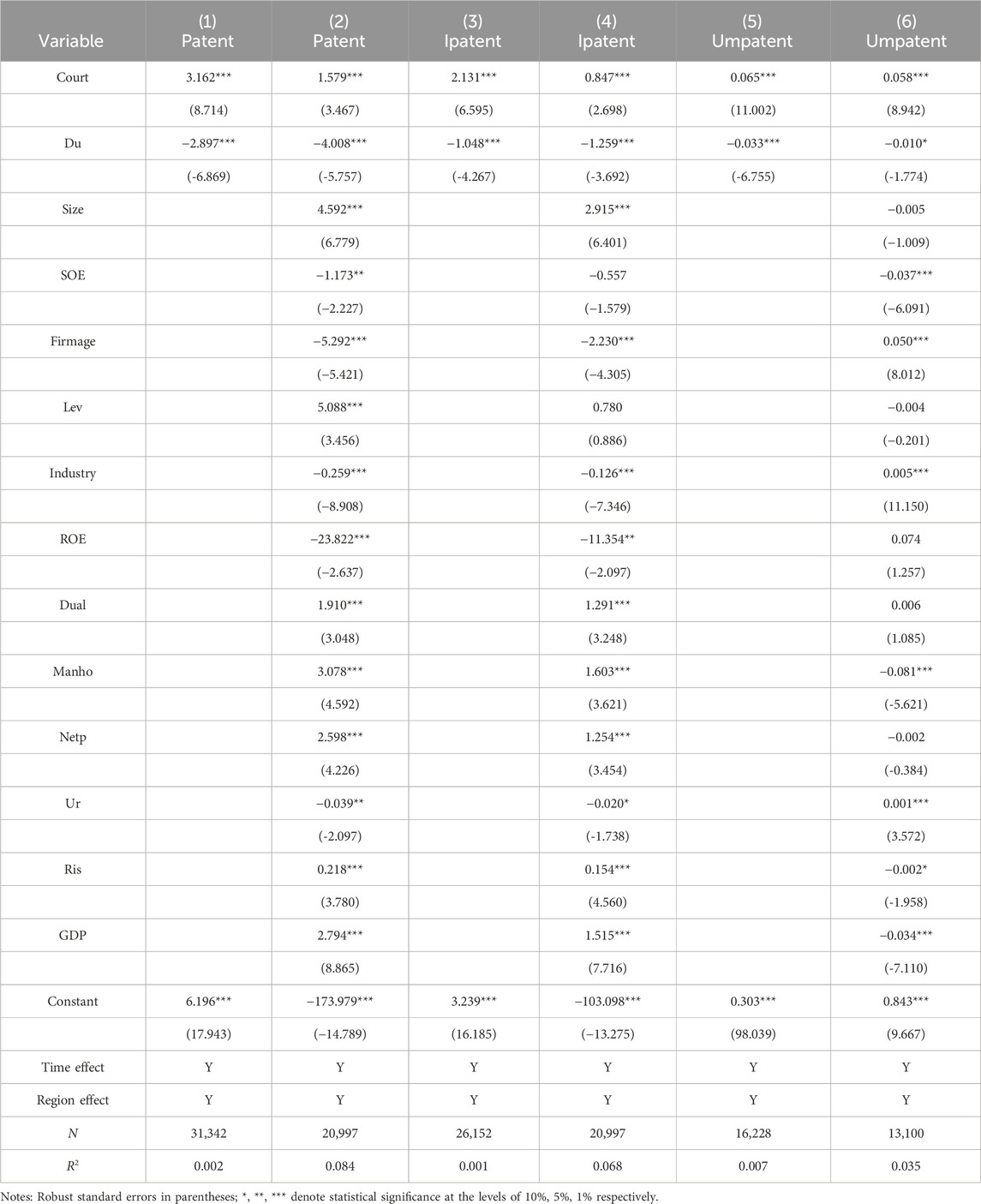

The results of the regression of environmental courts on corporate green innovation are shown in Table 2. Column (1) controls for time and regional fixed effects with no control variables. The results show that the regression coefficient of the double DID interaction term, Court, is significantly positive at the 1% level, which preliminarily indicates that the establishment of environmental courts has improved the level of corporate green innovation. After adding the city and regional level control variables in Column (2), the coefficient of the interaction term decreased to 1.346. The significance and absolute value of the regression coefficient Court change slightly, about one-third of the coefficient without the control variables. The possible reason for this could be that the control variables play an intermediary role, causing the establishment effect of the environmental court to be absorbed by the control variables, thereby affecting corporate green innovation and reducing the coefficient. This strongly demonstrates the rationality of the selection of control variables and the significant facilitating role of the net effect of environmental court establishment on corporate green innovation. The regression results still support the above findings.

While the type of patent reflects different innovation motivations, invention patents are considered substantive innovation that drives technological progress (Costantini and Mazzanti, 2012). This paper further examines whether the establishment of environmental courts can improve the quality of corporate green innovation. Patents are distinguished by the type of green patents into the number of green invention patents (Ipatent) and the number of green utility-based patents (Umpatent). The estimated coefficients of Columns (3), (4), (5), and (6) in Table 2 are all significantly positive, and the absolute values of the estimated coefficients in Columns (3) and (4) are larger, indicating that the establishment of environmental courts has a certain enhancing effect on different types of green innovation levels. To a greater extent, the establishment also increases the number of patent applications for green inventions, thus improving the substantive green innovation capacity of enterprises.

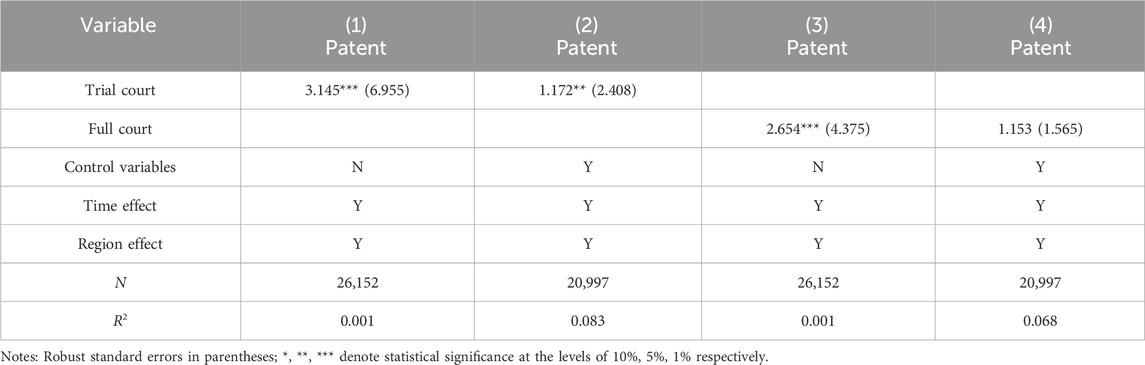

Environmental resources tribunals occupy an important position as the core organization for the court to hear cases, maintaining high utility in terms of both quantity and quality. Meanwhile, in order to promote the centralized hearing of ecological environmental cases of natural environment pollution torts under their jurisdiction, a number of intermediate people’s courts have simultaneously established environmental resources collegial panels. Due to the applicability of internal management and personnel composition, the evaluation of system efficiency based on trial efficiency, professionalism and uniformity shows that the widespread establishment of collegial panels lacks legitimacy and rationality (Han, 2019). From the perspective of professionalism and uniformity, collegial panels have not been well implemented in Chinese judicial practice. Most trials in collegial panels often have the problem of “convening without deliberation, convening without discussion” (Ye, 2010), which hinders the improvement of judicial efficiency.

Therefore, do the institutional drawbacks of collegial panels in environmental justice also affect their impact on green innovation? The regression results in Table 3 show that among the environmental courts established by intermediate courts, the environmental resource tribunals (Trial court) can effectively improve the level of corporate green innovation. While compared with the environmental tribunals, the collegial panels (Full court) can also promote the level of corporate green innovation, but the effect is not significant. It can be seen that in the current trial system of Chinese courts, the systematical and operational disadvantages of collegial panels still exist in environmental justice. The current process of legal construction of environmental pollution control in China needs continuous policy experiments to improve the legal mechanism construction of green innovation. More importantly, it is necessary to ensure that the new legal system and operational mechanism can be truly implemented in practice.

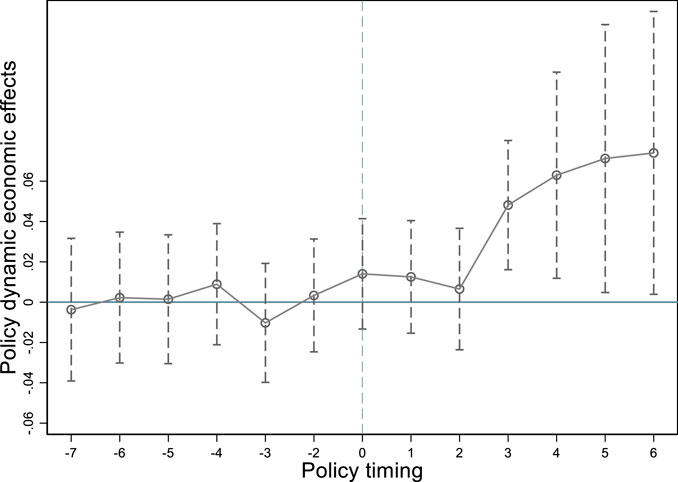

5.2 Parallel trend test

The prerequisite for causal inference using the DID is that there are no different trends between the treatment and control groups prior to the policy event, i.e., the green innovation levels of the two groups of cities should maintain a parallel trend. Figure 4 presents the results within a 95% confidence interval, showing that there were no significant differences before the policy was implemented. It indicates that there was no systematic difference in green innovation levels between the experimental and control group cities before the actual establishment of the environmental court, and the parallel trend hypothesis is verified. Therefore, the baseline regression results are not caused by inherent time trends between the two groups of regions. Moreover, the estimated coefficients were not significant in the 2 years immediately following the establishment of environmental courts, but became significantly positive after the third year, with the absolute value of the coefficients gradually increasing. This suggests that the establishment of environmental courts has a certain lagged effect on promoting the level of green innovation in firms, and furthermore, the policy effect gradually strengthened over time.

5.3 Robustness test

5.3.1 Propensity score matching

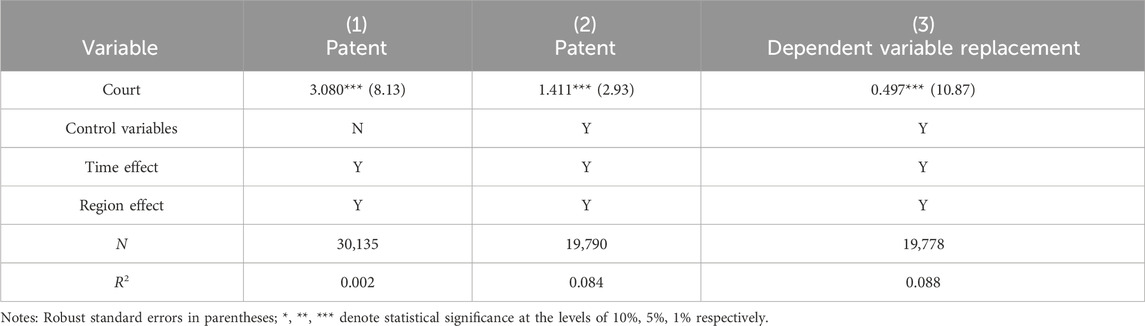

Following the work of Blundell and Dias (2010) and Heyman et al. (2007), we use a propensity score matching (PSM) to match year by year from 2007 to 2021, finding a comparable control group for the treatment group in each year. We combine observable control variables to perform a one-to-one matching of the treatment and control group samples. First, we compute the propensity score for each observation and then find the only control group of cities that did not establish environmental courts for the city with environmental courts (treatment group). After deleting the unsuccessful matches of 1,207 samples, we finally obtain 19,790 control group samples corresponding to the treatment group.

To verify the reliability of the results, we conducted balance tests for each year, confirming that there were no significant systematic differences in the control variables between the control and treatment groups. After matching, the sample characteristics of the treatment and control groups tended to be consistent. At the same time, the p-values of the t-test statistics after matching are not significant at the 10% significance level, indicating no significant systematic difference. Overall, the matching results are satisfactory, passing the balance test and effectively eliminating the endogeneity bias. The DID regression after matching is performed on the data as shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 4. The test results indicate that the hypothesis remains valid regardless of the inclusion of the control variables.

5.3.2 Dependent variable replacement

Following the related study by Fan and Zhao (2019), we substitute the ratio of R&D investment to operating income (Rd) as the new dependent variable. Specifically, we perform data matching before the regression to ensure the availability and continuity of data and filter out missing data. Estimated by DID to prevent selective bias in the experiment, the regression results in Column 3 of Table 4 show that the regression coefficient of the interaction term Court is significantly positive at the 1% level regardless of whether control variables are included, which is consistent with the regression results above.

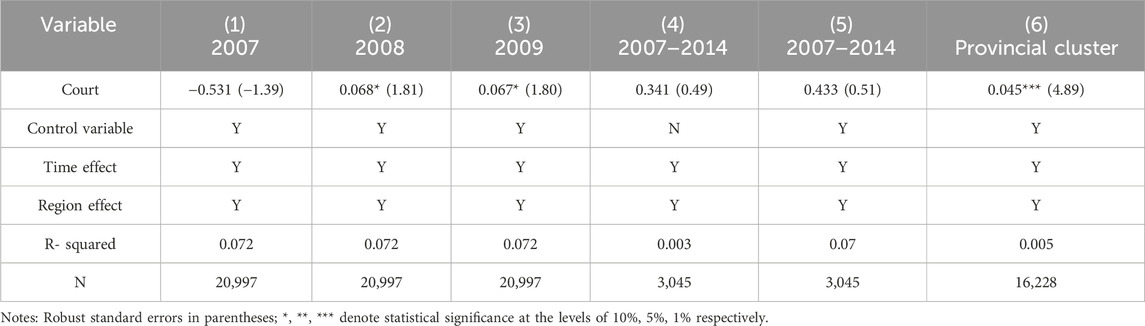

5.3.3 Dynamic effect test

Currently, environmental courts in China are still in the developmental stage and have not fully matured. Therefore, we further verify the dynamic benefits of environmental courts on green innovation, considering the lag in their effectiveness. Since the establishment of environmental courts began in 2007 and gradually expanded to different regions, this study designates cities with environmental courts as the experimental group and cities without environmental courts as the control group. The time points for the establishment, 2007, 2008, and 2009, are examined to determine the dynamic marginal effect of environmental court establishment on corporate green innovation over time. The specific results are shown in Table 5. Columns (1), (2), and (3) show the dynamic effect regression results for the years 2007, 2008, and 2009, respectively. The results in Column (1) indicate that the establishment of environmental courts in 2007 did not have a significant effect on corporate green innovation. This may be due to 2007 being the first year of the formal establishment of environmental courts. In Guiyang, only a few cities had started implementing the policy on a pilot basis. Although the effect was not immediately obvious, it began to emerge in the second and third years after implementation (2008 and 2009). Additionally, both Columns (2) and (3) show positive significance at the 10% level, with values of 0.068 and 0.067, respectively. It is evident that in the 2 years following implementation, the effects are not particularly significant, but they do have a certain promotional effect. This indicates that the establishment of environmental courts will promote green innovation in enterprises, further validating the hypothesis.

5.3.4 Counterfactual analysis

To further test the reliability of the hypothesis results, this paper conducts a counterfactual test by creating a hypothetical treatment group. Since only a few cities had established environmental courts before 2014, we have selected the time interval of 2007-2014. The sample excludes cities that established environmental courts during this interval. A consistency test was conducted, assuming 2009 as the time point for the establishment of environmental courts. We then use the traditional DID method to verify the absence of a shock effect. The green innovation efficiency of enterprises in cities, with or without environmental courts, should remain consistent over time. Furthermore, innovation efficiency trends should remain parallel before and after the establishment of said courts. In Columns (4) and (5) of Table 5, the regression coefficient of Court in the model after adding control variables is 0.433, which is not statistically significant. This shows that providing a specific policy to cities without environmental courts, under the hypothetical policy treatment, does not improve the innovation efficiency of enterprises. This conclusion is not due to systematic factors but rather the establishment of environmental courts, which has a significant impact on the green innovation of enterprises, proving its robustness.

5.3.5 Provincial cluster test

We cluster at the provincial level to compute the standard errors, considering the spatial autocorrelation issues among enterprises within the same province. The results, shown in Column (6) of Table 5, indicate a significant positive interaction term, supporting the hypothesis.

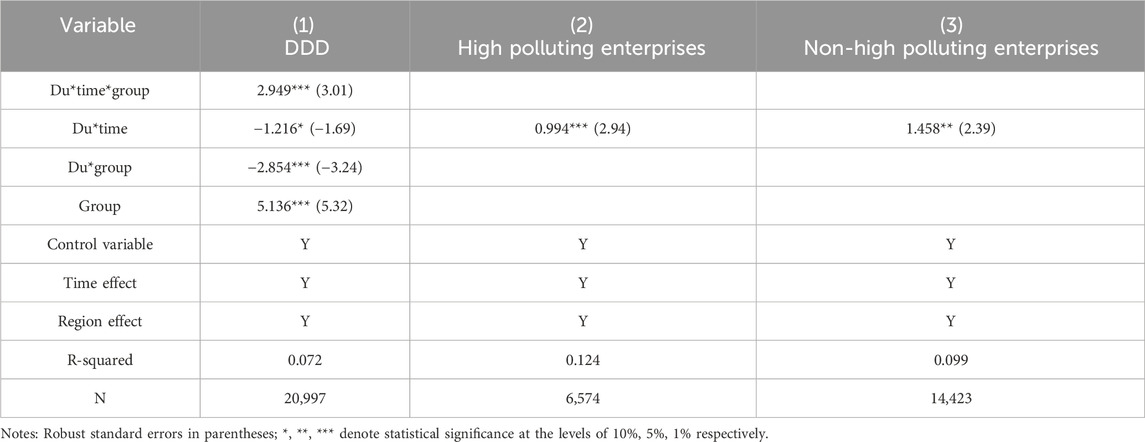

5.3.6 Triple-difference regression

The double-difference estimation strategy has potential problems: apart from environmental regulations, there may be other policies that affect regions with and without environmental courts differently, leading to biased estimation results. To overcome this problem, a triple-difference method is needed. This involves finding another pair of “treatment group” and “control group” that are not affected by environmental regulations. The second pair of treatment and control groups differ only in the impact of other policies, as non-polluting industries are not affected by environmental regulations. To determine the net effect of environmental regulations, we subtract the difference between the second pair of treatment and control groups related to other policies from the difference between the first pair of treatment and control groups (including differences in environmental regulations and other policies).

Based on the analysis above, we construct a triple-difference model (DDD) by multiplying the double-difference model with the third difference (Group) that represents whether the enterprise is a high polluter in the regional dimension. If the enterprise is heavily polluting after the year of the establishment of environmental court in the region, the value of Du*time*group is set to 1; otherwise, it is set to 0. As shown in Column (1) of Table 6, the coefficient of Du*time*group is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the establishment of environmental courts has a significant impact on promoting corporate green innovation. Additionally, this paper conducts grouped tests to determine whether enterprises are in high-polluting industries. The results, shown in Columns (2) and (3), demonstrate that the promotion effect is more significant in high-polluting companies. The promotion effect on high-polluting companies is more significant.

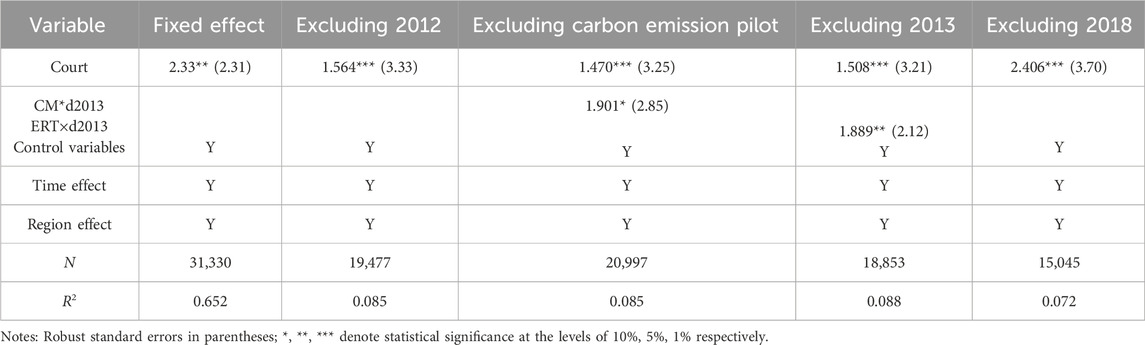

5.3.7 Exclusion of other policy interference

5.3.7.1 Fixed effects test

To eliminate interference from other policies on baseline empirical tests, this paper controls for the effects of individuals (firms), year, industry*year, and province*year. Other policies, such as industrial policies, local policies, and regional pilot projects, are mainly implemented at the industry and regional levels. Therefore, the fixed effects mentioned above can better control for interference from most other policies. As shown in Column (1) of Table 7, the establishment of environmental courts continues to promote green innovation in enterprises even after controlling for the influence of other policies through the addition of fixed effects.

5.3.7.2 The respective impact of various environmental regulations

Policy of Green Credit Guidelines. In 2012, the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) issued the Green Credit Guidelines to promote the development of green credit in banking and financial institutions. The promotion of green credit encourages corporate green innovation. However, it may introduce an upward bias in the estimates of this study. To avoid any potential bias, we removed the sample data from 2012 and conducted a difference-in-differences regression. The results, shown in Column (2) of Table 7, remain significantly positive.

Program of Establishment of Carbon Emissions Pilots. From 2013 to 2015, the Chinese government designated Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Guangdong, Shenzhen, Hubei, and Chongqing as pilot provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities for carbon emissions trading systems. To mitigate the confusion effect of carbon pilots, our study further controlled the CM×d2013 using 34 pilot cities1 located in the above 7 pilot regions. If the firm is located in one of the 34 pilot cities, CM equals 1; otherwise it is 0. The dummy variable d2013 equals 1 if time t ≥ 2013. In Column (3) of Table 7, the results show that the coefficient Court remains statistically significant.

Ten policies of air pollution. In 2013, Chinese Premier Li implemented ten policies to prevent and control atmospheric pollution during a State Council executive meeting. As a result, various cities proposed PM2.5 emission reduction targets. To mitigate the confounding effect caused by atmospheric policies, we constructed ERT × d2013, an interaction term of emission reduction targets and time dummy variable, to control for their effects. ERT is a variable based on the logic of local government work reports and text analysis to determine whether specific emission reduction targets were set by the municipal government that year. The variable is assigned a value of 1 if prefecture-level governments specifically list quantitative environmental management objectives in their work reports for the year; otherwise, it is assigned a value of 0. The time dummy variable d2013 takes a value of 1 for the year 2013 and thereafter; otherwise, it takes a value of 0. In Column (4) of Table 8, the estimates are significantly positive and remain effective.

Environmental tax and dual-carbon policy. In 2018, the Chinese government enacted the Environmental Protection Tax Law. To exclude the influence of environmental taxes and dual-carbon policy, we removed the sample data after 2018. The results, shown in Column (5) of Table 8, are significantly positive, confirming the hypothesis.

6 Mechanism test and heterogeneity analysis

6.1 Mechanism test

The previous section analyzed the impact of establishing environmental courts on green innovation. Building on this foundation, the following section investigates the mechanisms by which environmental courts affect corporate green innovation. The tests include three aspects: regional environmental justice efficiency, government environmental awareness, and corporate violation costs.

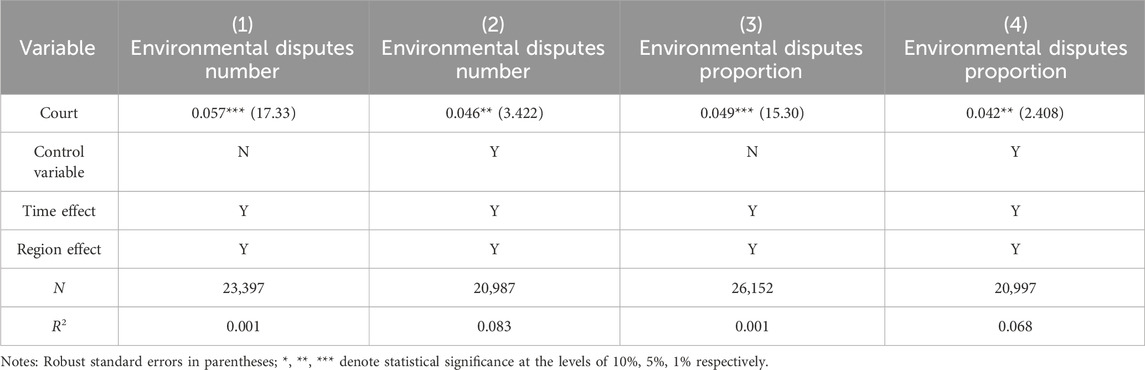

6.1.1 Regional environmental justice efficiency

Our paper collects and organizes data on environmental judicial cases at the prefectural level in China Judgements Online. We use the number of environmental pollution liability dispute cases as a proxy variable for regional environmental justice efficiency and conduct the DID test. Additionally, we use the proportion of environmental pollution liability dispute cases to all tort liability dispute cases for robustness testing. After controlling for time and regional effects, the promotion effect remains significantly positive, as shown in Table 8.

However, the influence on environmental justice may not be solely attributed to the establishment of environmental courts. The observed impact is possibly a result of an overall improvement in judicial efficiency in the region. Therefore, there is a risk of overestimating the impact of environmental courts on environmental justice. To eliminate this factor, our study uses the total number of cases of tort liability disputes as a placebo test. The results indicate that environmental courts do not significantly impact the efficiency of adjudicating non-environmental pollution tort disputes. This suggests that the influence of environmental courts on the adjudication of regional environmental pollution disputes primarily comes from the functioning of the system itself.

6.1.2 Government environmental awareness

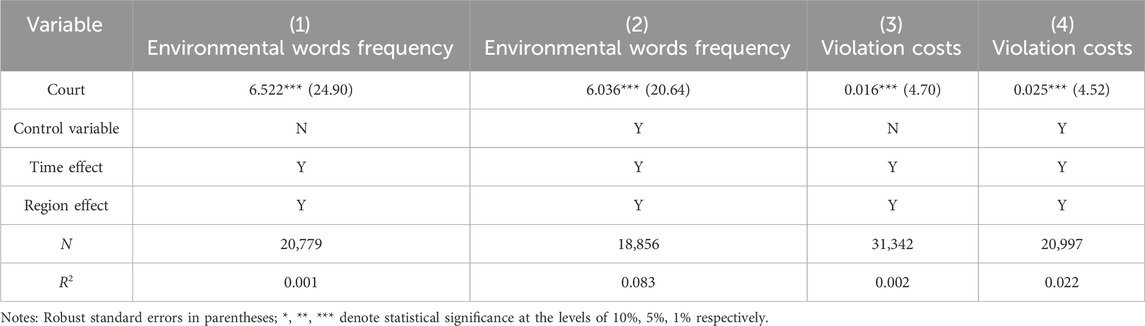

The establishment of environmental courts has increased the government’s focus on environmental protection. This policy is closely linked to the surrounding environment. When the public demands a better living environment, it reflects the government’s awareness of environmental protection. Improving such awareness creates a soft constraint on enterprises, encouraging them to promote green innovation. Therefore, our paper uses the frequency of environmental words in government reports at the prefecture level as a proxy variable for the government’s awareness of environmental protection. We statistically match different years and include them in a DID regression. The test results, shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 9, are both significantly positive. Column (1) does not include control variables, while Column (2) does.

6.1.3 Corporate violation costs

This paper measures the cost of corporate violations by calculating the ratio of production costs to operating income. In Columns (3) and (4) of Table 8, the results are significantly positive regardless of the inclusion of control variables. The “combination of trial and enforcement” mode in environmental courts aims to establish a coordinated mechanism to strengthen enforcement power in environmental cases. This mode also addresses the issue of environmental protection bureaus being influenced by local governments. In cases where pollution has significantly affected public life, environmental courts may conduct interviews with defendants or impose behavioral restrictions before trial results. After the verdict, environmental courts have the power to directly enforce the verdict, thus ensuring compliance with the environmental judgment by enterprises that may refuse to accept the court’s ruling. This improves the efficiency of the rule of law and the severity of punishment, reduces the likelihood of local government protection, and increases potential environmental litigation risks and legal costs for enterprises. The firms will therefore improve their environmental management practices to reduce the likelihood of being punished.

6.2 Heterogeneity analysis

This paper further analyzes whether environmental courts show apparent heterogeneity in promoting corporate green innovation from the perspectives of the nature of enterprise ownership, the level of regional rule of law environment, and the degree of industry competition.

Heterogeneity in the nature of ownership is crucial in the study because there are significant differences between SOEs and private firms in terms of access to resources, decision-making mechanisms and incentives to innovate. SOEs may be more influenced by government policies, while private firms are more concerned with market competition and brand image. This difference may lead to differences in their responses to environmental tribunals and their green innovation capabilities, thus affecting the assessment of policy effects.

Level of regional rule of law environment: Heterogeneity in the regional rule of law environment affects firms’ compliance costs and willingness to innovate. In regions with better rule of law environments, firms face stricter environmental requirements, prompting them to increase green technology investment and innovation. In regions with weak rule of law environments, on the other hand, firms may invest less in environmental protection, so studying these differences helps to understand the mechanisms by which environmental tribunals work on green innovation in different rule of law contexts.

Degree of industry competition: Heterogeneity in the degree of industry competition has an important impact on firms’ innovation strategies. In highly competitive industries, firms often need to respond quickly to changes in market demand and policies, and may be more active in green innovation to maintain a competitive advantage. In relatively less competitive industries, firms may be less eager to invest in green technologies, and therefore examining the degree of competition in different industries is critical to understanding the impact of environmental tribunals on green innovation.

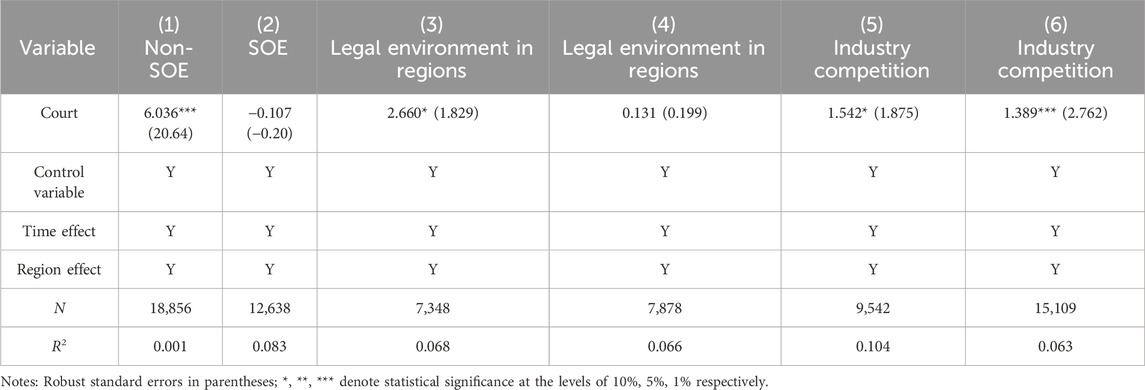

6.2.1 The nature of enterprise ownership

Shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 10, the results indicate that the establishment of environmental courts has improved the level of green innovation in non-state-owned enterprises, while state-owned enterprises do not show a significant green innovation effect and environmental investment governance dynamics. The reason may be that the nature of state-owned enterprises, under the protection of local governments, determines their stronger bargaining power in the face of environmental regulation (He et al., 2020) and stronger path dependency effects in the process of innovation upgrading (Xu and Cui, 2020). Against the backdrop of strengthening environmental governance and achieving the dual-carbon targets in China, state-owned enterprises need to improve governance mechanisms, strengthen innovation-driven leadership, and achieve green and high-quality development.

6.2.2 The level of rule of legal environment in regions

The results for the level of the rule of legal environment in regions are reflected in Columns (3) and (4) of Table 10. Columns (3) and (4) show the empirical results for regions with better and general rule of law environments, respectively. Legislative and judicial processes mutually guarantee and promote each other, hence the deterrent effect of environmental courts on polluting firms is influenced by the general legal environment of the region. In a favorable legal environment, investors and enterprises can reasonably expect the establishment of environmental courts to take strict action and show zero tolerance toward illegal pollution emissions. In regions with a better legal environment, the establishment of environmental courts has a more pronounced effect on promoting corporate green innovation, suggesting that a good regional environmental legislation can help promote the rule of environmental law and foster a green orientation in financial markets.

6.2.3 The degree of industry competition

The degree of industry competition is reflected in the results of Columns (5) and (6) of Table 10. The empirical results of Column (5) and (6) are for intense and weak industry competition, respectively. The degree of industry competition indirectly reflects the difficulty of corporate profitability; the more intense the industry competition, the more it will inhibit the level of corporate green innovation. In other words, firms will pay less attention to environmental issues in pursuit of profits from market occupation, resulting in a limited level of green innovation.

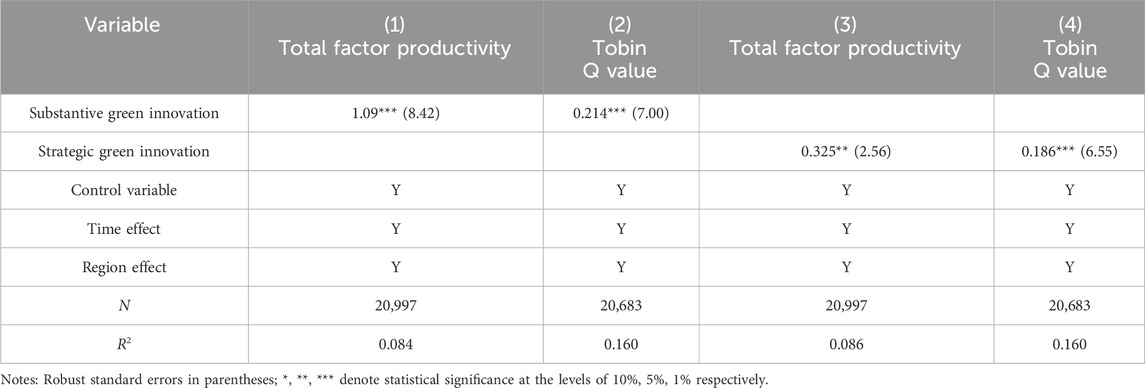

7 Further analysis

We further examine the impact of two different types of green innovation on firm economic benefits. Invention patents and utility-based patents are used to represent substantive and strategic green innovation, respectively. Based on Previous studies which have emphasized the role of green total factor productivity in environmental management, It is a crucial indicator for countries to address environmental challenges, improve environmental performance, and foster sustainable (Jiang et al., 2024). Our paper selects total factor productivity and Tobin’s Q value to measure the economic benefits of firms, and thus constructs models of the impact of the two types of green innovation on the economic benefits of firms. Among them, total factor productivity is estimated by the Levinson-Petrin (LP) method, while Tobin’s Q value is measured by the ratio of enterprise market value to total assets. The regression result in Column (1) of Table 11 is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that substantive green innovation has a positive impact on total factor productivity. Furthermore, the results in Column (3) are significantly positive at the 5% level, suggesting that this positive impact is even more pronounced. Similar results are reported in Columns (2) and (4). Therefore, overall, substantive green innovation has a more significant effect on improving the economic benefits of firms. Thus, promoting technological progress and obtaining competitive advantages through substantive innovation can enhance the market value of enterprises and promote their development.

8 Conclusion and implications

Currently, the governance of environmental pollution is still a significant challenge in China. In the process of promoting pollution control, the legal system always plays a fundamental role. This paper focuses on environmental courts, which are regarded as a manifestation of ecological rule of law, and explores their impact, effectiveness, and mechanisms on corporate green innovation. This will help in understanding how the ecological rule of law compels enterprises to achieve green transformation and sustainable development goals. Meanwhile, our study also provides countries with experiences on how to balance economic growth and environmental protection.

Our research indicates that environmental courts are effective in promoting corporate green innovation, particularly in terms of substantive innovation. (1) Furthermore, environmental courts have a greater impact on promoting corporate green innovation compared to environmental resources collegial panels. (2) The establishment of environmental courts can improve the efficiency of regional environmental justice and raise government environmental awareness. This can result in increased costs for corporate violations and ultimately promote corporate green innovation. (3) The promotional effect is stronger in regions with non-state-owned enterprises, favorable legal environments, and lower levels of industry competition.

This paper suggests that continuous improvement of the construction of the ecological rule of law is important for achieving harmonious coexistence between the environment and the economy while pursuing rapid economic development. This kind of improvement could motivate enterprises to innovate in pollution control technologies, allowing them to reduce energy consumption and pollutant emissions while engaging in production activities and improving technology levels to enhance international competitiveness. However, the green innovation effect, strengthened by the rule of law, also requires support from complementary measures, such as improving judicial efficiency and government environmental awareness. Therefore, to further promote the process of legalizing environmental governance reforms, it is necessary to strengthen the assessment and supervision of environmental law enforcement in judicial departments. By utilizing the deterrent effect of legal penalties, firms can be “compelled” to undergo green transformation and upgrading. On the other hand, it is also suggested to continuously improve the legal system and raise the level of legal construction in the regions. This can encourage residents to exercise their environmental legal rights, thereby increasing the judicial channels for environmental pollution disputes and ultimately strengthening the level of rule of law in environmental pollution control.

The conclusions highlight that while pursuing rapid economic development, it is crucial to enhance the construction of ecological rule of law to achieve a harmonious coexistence between the environment and the economy. The establishment of environmental protection courts strengthens judicial authority and credibility, and, compared to other governance models, has a lasting impact on corporate environmental governance, facilitating a win-win scenario for both the environment and the economy. Furthermore, the creation of environmental protection courts sends a positive signal to the public, encouraging enterprises to align their behaviors with governmental expectations of social responsibility. This enhances corporate green reputation, meeting the demands of relevant stakeholders. The establishment of such courts promotes a greater emphasis on environmental benefits alongside economic objectives, fostering a harmonious relationship between environmental protection and economic development. This environment can incentivize enterprises to innovate in pollution control technologies, reducing energy consumption and pollutant emissions during production activities, while also motivating them to pursue green innovations that improve their technological capabilities and international competitiveness. Ultimately, this initiative supports sustainable socio-economic development, protects environmental resources through judicial mechanisms, and ensures a livable planet for future generations.

The research presented in this paper acknowledges certain limitations that warrant further exploration. First, the issue of environmental protection enforcement across different administrative jurisdictions becomes increasingly pronounced due to the influence of local protectionist forces. Future studies could delve deeper into government protectionism in this context. Second, subsequent research could refine and expand upon the impact of ecological rule of law construction on other relevant elements of corporate green innovation, promoting proactive environmental governance among enterprises and encouraging them to adopt more active environmental management practices. Finally, in measuring the construction of ecological rule of law, we have chosen to use the establishment of environmental protection courts as a specific policy indicator, relying on manual data compilation from the year of implementation. However, this singular indicator may not fully encapsulate the broader scope of ecological rule of law construction. Thus, developing more precise measurement methodologies and improving access to relevant data is essential for studying the input-output efficiency of ecological rule of law construction in a more comprehensive manner. This area warrants further research to enhance our understanding of ecological rule of law effectiveness.

9 Classification codes

M380 Marketing and Advertising : Government Policy and Regulation

K230 Regulated Industries and Administrative Law

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

YG: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. NL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing–review and editing. LC: Formal Analysis, Project administration, Validation, Writing–review and editing. HH: Funding acquisition, Resources, Visualization, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by: the Project of Humanity and Social Science Foundation of Ministry of Education [Grant No. 19YJC790035]; Soft Science Research Program of Shaanxi Province, China [Grant No. 2024ZC-YBXM-057]; Key Project of Soft Science Research Program in Zhejiang Province [Grant No. 2024C25024], the Major Project of Humanity and Social Science in Zhejiang universities [Grant No. 2021QN063].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1The 34 pilot cities come from the 7 pilot carbon emissions trading systems, specifically Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Zhuhai, Jiangmen, Foshan, Zhaoqing, Huizhou, Shantou, Chaozhou, Jieyang, Shanwei, Zhanjiang, Maoming, Yangjiang, Shaoguan, Meizhou, Qingyuan, Yunfu, Wuhan, Huangshi, Shiyan, Yichang, Xiangyang, Jingmen, Xiaogan, Jingzhou, Huanggang, Xianning

References

Almer, C., and Goeschl, T. (2010). Environmental crime and punishment: empirical evidence from the German penal code. Land Econ. 86 (4), 707–726. doi:10.3368/le.86.4.707