- 1Faculty of Computing, Engineering and the Built Environment, Birmingham City University, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 2Environmental Change Institute and Nature-based Solutions Initiative, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Planning, Property and Environmental Management, Humanities Bridgeford Street, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 4Natural England, Strategy and Government Advice Team, York, United Kingdom

- 5Peter Neal Consulting, London, United Kingdom

Multi-functional urban green infrastructure (GI) can deliver nature-based solutions that help address climate change, while providing wider benefits for human health and biodiversity. However, this will only be achieved effectively, sustainably and equitably if GI is carefully planned, implemented and maintained to a high standard, in partnership with stakeholders. This paper draws on original research into the design of a menu of GI standards for England, commissioned by Natural England—a United Kingdom Government agency. It describes the evolution of the standards within the context of United Kingdom government policy initiatives for nature and climate. We show how existing standards and guidelines were curated into a comprehensive framework consisting of a Core Menu and five Headline Standards. This moved beyond simplistic metrics such as total green space, to deliver GI that meets five key ‘descriptive principles’: accessible, connected, locally distinctive, multi-functional and varied, and thus delivers 5 ‘benefits principles’: places that are nature rich and beautiful, active and healthy, thriving and prosperous, resilient and climate positive, and with improved water management. It also builds in process guidance, bringing together stakeholders to co-ordinate GI development strategically across different sectors. Drawing on stakeholder feedback, we evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the standards and discuss how they provide clarity and consistency while balancing tensions between top-down targets and the need for flexibility to meet local needs. A crucial factor is the delivery of the standards within a framework of supporting tools, advice and guidance, to help planners with limited resources deliver more effective and robust green infrastructure with multiple benefits.

1 Introduction

Urban areas face increasing challenges from climate change, including floods, heatwaves, and droughts (Díaz et al., 2024). A key response involves using Nature-based Solutions (NbS): actions to protect, restore, create or sustainably manage natural, semi-natural or manmade ecosystems to tackle societal challenges, with benefits for both biodiversity and people (Cohen-Shacham et al., 2019). In urban areas, this includes the use of Green Infrastructure (GI), a network of natural and semi-natural features which is planned and managed to provide multiple ecosystem services and benefits for people and nature. GI can play a key role in climate change adaptation, particularly by helping to provide flood protection, shade and cooling, alongside wider benefits such as climate mitigation, air and water quality regulation, and green space for recreation (Choi et al., 2021). Additionally, there is substantial evidence that GI has a positive influence on health and well-being (Lovell et al., 2020), and that investing in GI can enhance equality of access (Hunter et al., 2019) and quality of life (Jerome et al., 2019).

However, poorly planned and implemented GI may not deliver these benefits sustainably and effectively. Both quantity and quality of GI are important. For example, low quality green roofs consisting of a thin layer of sedum matting provide limited rainwater absorption or insulation and may die off during droughts and heatwaves (Smith and Chausson, 2021). The process of designing GI is critical; for example, failure to include local stakeholders can result in inequitable outcomes (Derickson et al., 2021).

Standards and guidelines to ensure GI effectiveness have been developed in several countries, but are of mixed quality (Roghani et al., 2024). Guidelines often focus on specific challenges such as climate resilience (Klemm et al., 2017) or heat mitigation (Pereira et al., 2024), or specific issues such as community engagement (Everett et al., 2023), but there is a lack of frameworks covering the full breadth of GI planning issues. Previous literature reviews have compiled theoretical guidance on good GI (e.g., Monteiro et al., 2020) but have not been translated into practical standards for implementation at the national level. This diverse, dispersed and incomplete guidance creates confusion and extra work for hard-pressed planners and practitioners.

This paper describes the development and initial evaluation of an integrated set of GI standards for England, although the process, principles and issues encountered are also applicable to other countries. It presents ‘action research’ in which academics work closely with practitioners and policymakers in an iterative process to co-develop, test and refine solutions to societal challenges (Croeser et al., 2024). In this case, the research was in response to government policy and was driven by Natural England, an independent government agency tasked with helping to conserve, enhance and manage the natural environment in England for the benefit of present and future generations, working in partnership with academics, consultants and stakeholders. In the remainder of this introduction, we explain the policy background driving development of the GI standards in England, set out the challenges being addressed by this study, and explain the aim and structure of the paper.

1.1 Policy drivers for development of GI standards for England

The United Kingdom Government recognizes the role of green infrastructure for delivering key environmental and social commitments on human health and wellbeing, climate change adaptation and mitigation, and nature recovery. This was reflected in the commitment to develop a set of GI standards for England in the 25 Year Environment Plan (HM Government, 2018); the other devolved United Kingdom nations set their own environmental policy. Later policies reinforced this commitment, including the HM Government (2021), the Outcome Indicator Framework (Defra, 2023) and the Environmental Improvement Plan (HM Government, 2023). These policies aimed to ensure that people would have access to high quality, accessible, natural spaces close to where they live and work, particularly in urban areas, and to encourage more people to spend time in green spaces to benefit their health and wellbeing (HM Government, 2018; page 28) and social benefits; this has been embedded further in the 2024 updates to the NPPF (see para 159). This includes the need for safe and accessible urban GI to enable and support healthy lifestyles, especially where this would address identified local health and well-being needs, including the provision of allotments for growing healthier food, playing fields for active recreation, and green travel routes to encourage walking and cycling (DLUHC, 2023b; para 96c).

The rationale for developing GI standards was to encourage more investment by explaining what “good” GI looks like (HM Government, 2018; p76). Multi-functional outcomes are at the heart of this promise, mentioned in both the 25 Year Environment Plan and the NPPF. Government envisages GI as a “network of multi-functional green and blue spaces and other natural features, urban and rural, which is capable of delivering a wide range of environmental, economic, health and wellbeing benefits for nature, climate, local and wider communities and prosperity” (DLUHC, 2023b; Annex 2). These benefits include managing climate change risks by absorbing surface water and reducing high temperatures, as well as sequestering carbon, absorbing noise, improving air and water quality, and delivering Nature Recovery Networks of connected biodiverse habitats. Government also recognises that the distribution of urban greenspace is a factor in addressing social inequalities, deprivation and community cohesion, accepting that people in greener surroundings have longer and healthier lives (see Smith et al., 2023 for a summary of the evidence).

GI is also noted in the National Adaptation Plan (NAP), which explains the government’s plans to adapt to climate change to 2028, especially regarding the resilience of the United Kingdom’s infrastructure (Defra, 2024c; Defra, 2024d). Within the NAP, standards are expected to play a role in boosting climate change resilience across multiple sectors including road, rail, energy, food safety, buildings, water use efficiency, water quality, agriculture, and the health service. Similarly, the Environmental Improvement Plan covers standards for air and water quality, sustainable farming, safety, and green finance. The GI Standards accordingly line up alongside standards in many other sectors, aimed at delivering United Kingdom government policy commitments on climate change adaptation, net zero carbon, biodiversity loss, pollution, infrastructure security, and scarcity of land and water resources. Looking across these policy drivers and related standards, some important themes emerge: resilience, consistency, alignment of approaches and data within and between sectors, resource management and the security of infrastructure.

1.2 Challenges in development of GI standards

Development of standards requires decisions on three key aspects: what to measure, how to measure it (in terms of metrics, data and methods), and what level the standards should be set at. For GI, the standards need to cover quantity, quality, and the planning process. Delivering a minimum quantity of GI is a particular challenge in the United Kingdom, where high annual housebuilding targets and tight council budgets are placing pressure on both maintenance of existing green spaces and delivery of new ones. The 25 Year Environment Plan recognises this challenge, noting that the number and condition of green spaces has declined, and current investment is limited. It highlights the risk of losing good quality green spaces to urban development, while acknowledging that this development means that preserving and creating green spaces in towns is more important than ever. The tussle with growth is highlighted again within the NPPF (and the 2024 consultation on planning reform), which urges a significant uplift in the average density of residential development where land is in short supply. This makes it harder to include GI within these more compact developments.

The GI Standards need to respond to these external pressures and tensions in the context of the discretionary English planning system, which can permit development that has the potential to incrementally degrade (or enhance) GI assets at both a very local and more strategic scale. A key role for GI standards is, therefore, to help manage public expectations by creating confidence, consistency and certainty for developers and communities on both the quantity and the quality of GI expected in urban areas. However, this desire for consistency creates a further conflict with the need to respond to local needs, constraints and context (Zuniga-Teran et al., 2019).

This issue is not confined to a United Kingdom context. Globally an ongoing debate on the use of GI standards highlights the merits of a standardized approach for delivering continuity, but acknowledges that the application of standards is malleable due to variations in focus on specific ecological features or amenities in each location, the calculations of areas of facilities, site composition and perceived management (Lee et al., 2014). Additionally, there are questions around the applicability of different metrics such as proportions or areas of GI, and distance or time to access GI in different contexts (Dinand Ekkel and de Vries, 2017).

1.3 Aim and structure of the paper

As this paper describes an iterative, ongoing process of action research, in which the design of the standards continuously evolved in response to research findings and user feedback, it is not structured around a simple linear progression from pre-determined research questions to methods, results and discussion. Instead, we address the overarching question of how to develop a comprehensive and coherent menu of standards that can support planners and practitioners with limited time and resources to deliver more effective and robust GI with multiple benefits, taking into account the practical challenges, tensions and trade-offs discussed above. We illustrate this by describing the development of standards as part of a wider GI framework in England and evaluating their effectiveness through user feedback.

Accordingly, in the Methods section we first summarise the process of developing the overall GI Framework. We then show how the principles developed as part of this framework were used to inform development of the GI Standards by determining “what to measure”. This was underpinned by research to review existing tools, standards and guidance and collate them into a single framework, updating as needed, that covers GI quantity, quality, and the planning process. We also describe how the standards were continuously evaluated and refined with feedback from users. The Results section then addresses the question of “how to measure” by describing the system of standards that was developed. As part of this, we show how the standards evolved through “action research” in response to the ongoing process of consultation, critical evaluation and user feedback. Detailed descriptions of the standards can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Finally, in the Discussion we assess the overall strengths of the standards, summarise the extent of their uptake in local and national policy to date, and discuss key challenges. In particular, we focus on determining “what level the standards should be set at” in view of the tensions and trade-offs between top-down and locally adapted standards. We also consider the way forward, including how to facilitate implementation of the standards.

2 Methodology

2.1 Development of the GI framework

Development of the standards is part of a wider programme of research and development towards a national framework for GI. Natural England began to develop the GI Framework of Principles and Standards for England in 2018, working closely with the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra, 2024b) and a cross-government steering group (Dundon et al., 2019). The aim was to develop a voluntary suite of principles, standards and tools designed to support practitioners at all stages of GI development.

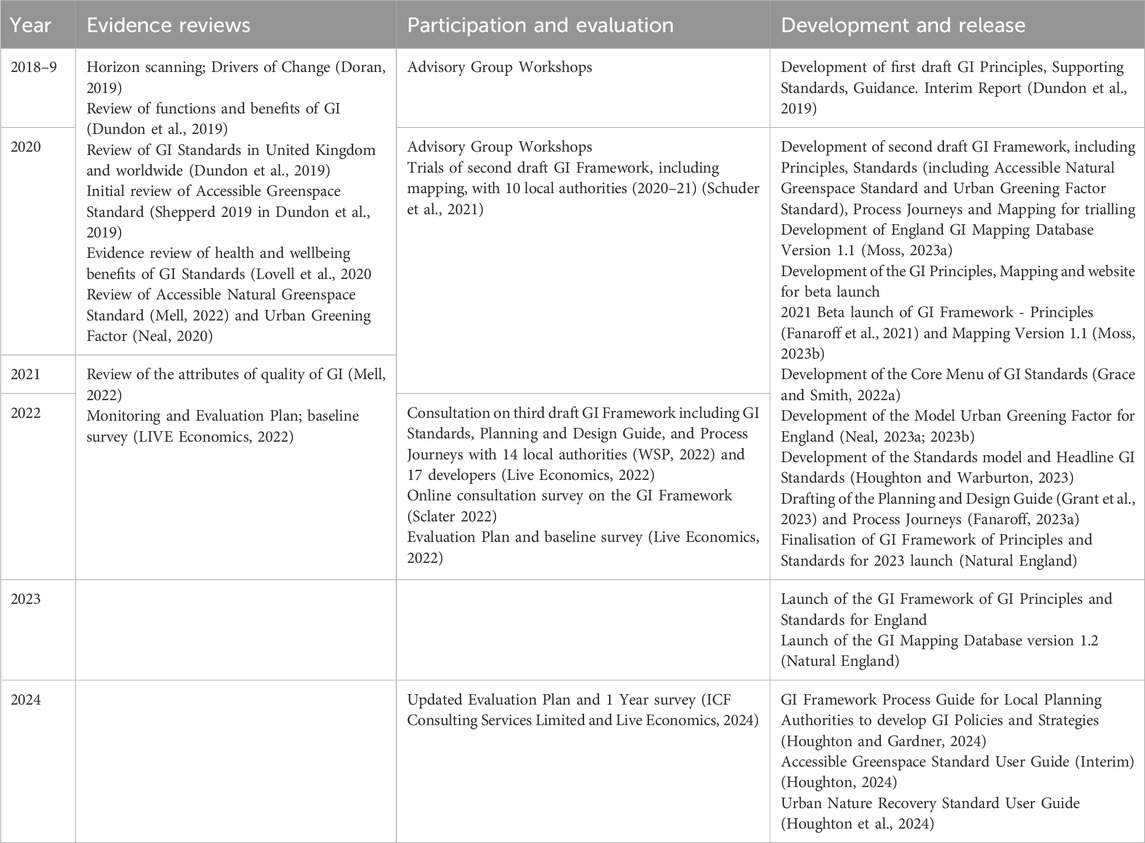

The development of the GI Framework (including the standards discussed in this paper) followed a participatory and evidence-based process (Table 1). Natural England started by undertaking a horizon scanning exercise, followed by workshops with a GI Project Advisory Group comprised of relevant practitioners and experts representing 35 GI-related organisations, to identify the future drivers of GI. This led to a series of evidence reviews covering the factors determining the health and wellbeing benefits of GI (Lovell et al., 2020), the effectiveness of Natural England’s pre-existing Accessible Natural Greenspace Standards (Mell and Neal, 2020a; Mell and Neal, 2020b), and a review of United Kingdom and international Urban Greening Factors (Neal, 2020). Natural England engaged the GI Framework Steering and Advisory Groups through online workshops to discuss the draft outputs.

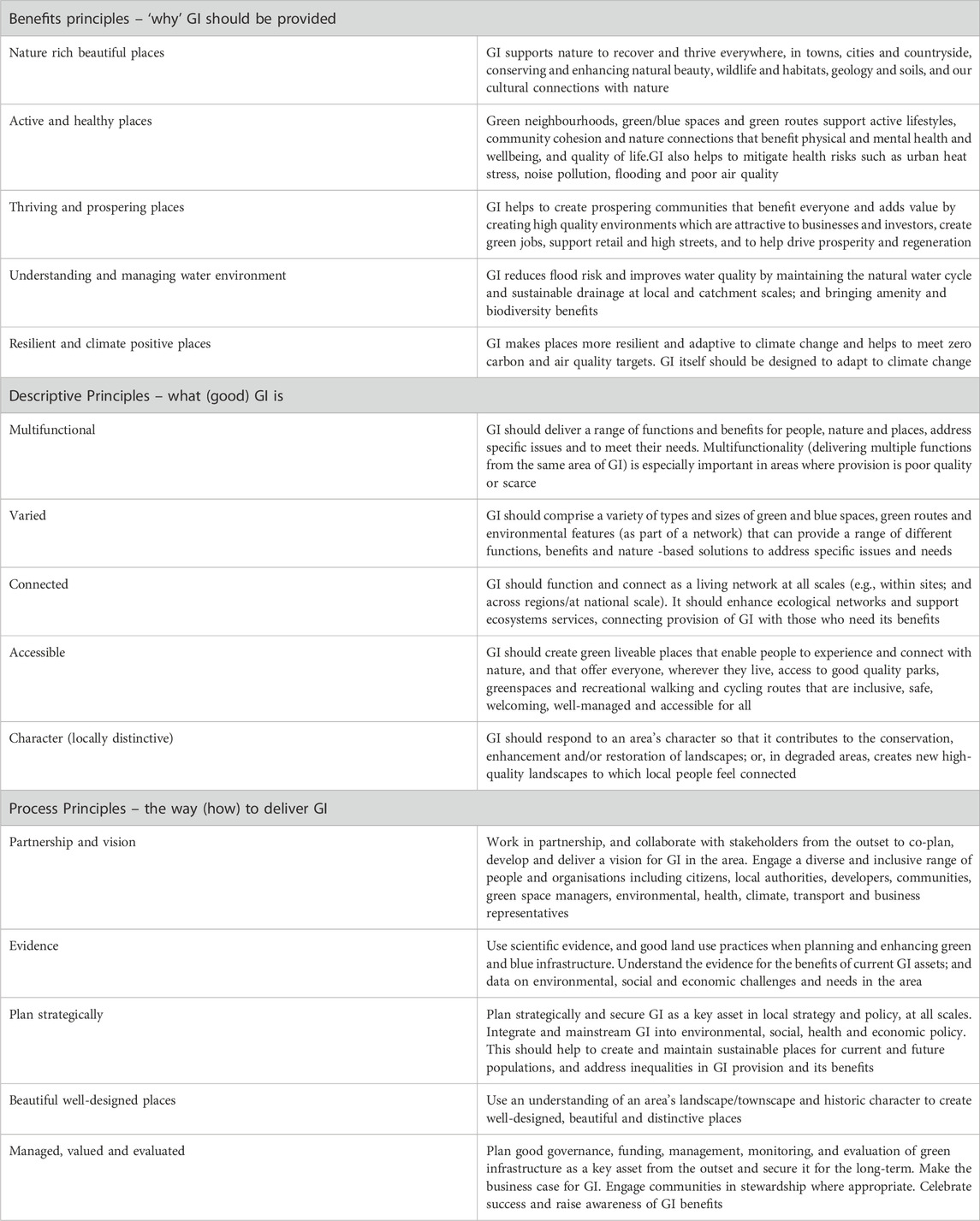

The evidence reviews underpinned development of a set of GI principles by Natural England. There are three groups of principles that describe why GI should be provided (benefit principles), what good GI looks like (descriptive principles), and how to deliver it (process principles) (Table 2) (Fanaroff et al., 2021; Fanaroff, 2023a). These principles directly informed the development of the GI standards.

The principles and standards are accompanied by the other elements of the GI Framework: a GI mapping database developed by Natural England for assessing and planning GI provision (Moss, 2023a; Moss, 2023b; Moss, 2023c); a planning and design guide advising on how to create good GI (Grant et al., 2023); case studies to illustrate examples of good GI (Natural England, 2023a; Neal, 2023a); and a suite of ‘process guides’ illustrating how to use the framework in different contexts for Local Planning Authorities (LPAs), neighbourhood planning groups, and developers (Fanaroff, 2023b; Houghton and Gardner, 2024). While this paper concentrates on development of the standards, it also shows how it is supported by the other elements of the framework. Natural England commissioned independent testing and consultation on the draft GI Framework design and components in 2020–21 and again in 2022 (Schüder et al., 2021; LIVE Economics, 2022; WSP, 2022).

2.2 Development of the GI standards

In 2021–22, Natural England collaborated with the research team to develop a set of GI standards underpinned by the key attributes of GI quantity, quality, and location, that will deliver the GI principles (Houghton and Warburton, 2023). The standards should:

• Support delivery of good quality GI with benefits for people and nature

• Help put the 15 GI principles into practice

• Bring multiple existing quantity standards, quality standards and best practice guidance together into a single logical framework

• Signpost standards that can be measured using the GI Mapping Database and other readily available datasets and resources

• Provide an easy-to-use hierarchical menu that signposts more detailed standards and guidance as needed

• Provide metrics for monitoring GI and help show progress towards achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets.

To decide “what to measure”, we focused on the logic of the 15 GI principles (Table 2). We reasoned that the GI Standards must enable Local Authorities to determine whether their GI meets the five descriptive principles that state what good GI should look like. In other words, GI must be accessible, connected, respond to local character, and be multifunctional and varied. We therefore aimed to develop a menu that groups standards under these five headings.

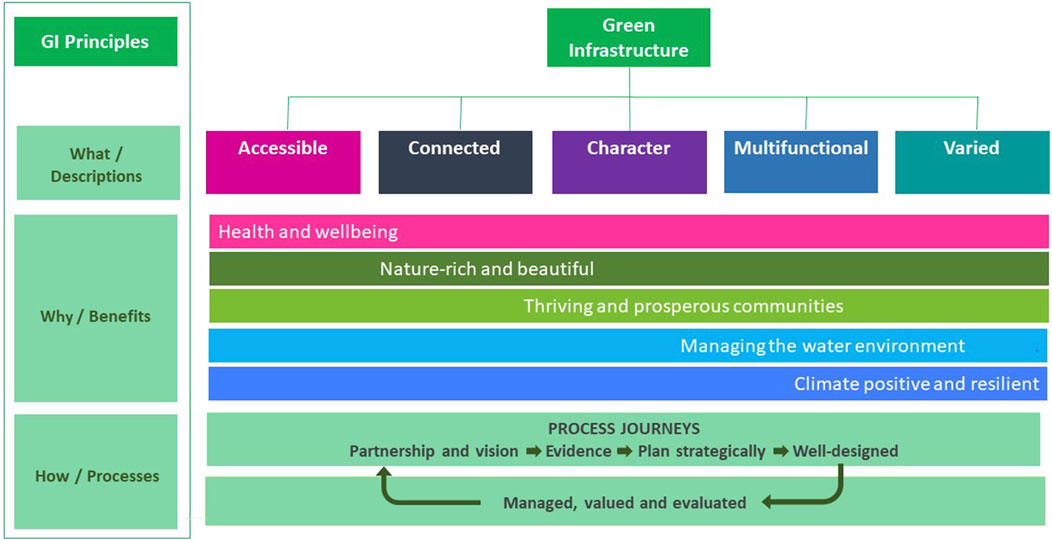

Following the logic of the GI principles, GI that meets those descriptions should deliver the five benefits identified in the “Why” principles: places that are ‘nature rich and beautiful, active and healthy, thriving and prospering, with improved water management, and resilient and climate positive (Figure 1). Local Authorities need to show how GI delivers these benefits, to make the case for investing in good quality GI. Several of these benefits are closely linked to specific descriptive principles. For example, health and well-being depends strongly on accessibility, hence the label is positioned under the “Accessible” principle on the left-hand side of the bar in Figure 1. Yet the bar extends across the whole diagram because the other four descriptive principles are also important for health and well-being. For example, GI needs to be well connected (i.e., walkable), characterful (to foster a sense of place), multifunctional (e.g., enhancing air and water quality, and protecting from floods and heatwaves) and varied (providing a range of parks, allotments, sports and play opportunities and an attractive and diverse environment).

The five process principles shown at the bottom of Figure 1 also play a vital role in delivering GI, ensuring that it is based on a partnership and vision, is evidence-based, strategically planned, well-designed and managed, valued and evaluated. These aspects are addressed partly by the Process Guides within the GI Framework. While these are not the focus of this paper, we aimed to embed the importance of the process principles within the GI standards–not least because all the standards aim to be evidence-based, enable good design, and facilitate managing, monitoring and evaluation.

To determine “how to measure” GI, relevant standards were selected to meet each of the five descriptive principles. To keep the menu simple for practitioners with limited time and resources, we aimed to select only the most significant (“core”) standards for delivering each principle, thus creating a “Core Menu” of standards that practitioners could draw on.

To select the core standards, the research team adopted a mixed method approach. First, we reviewed a list of relevant documents on potential quantitative GI standards compiled by Natural England, originating mainly from existing government departments and agencies and from earlier phases of the GI Framework development, including the evidence reviews (Table 1). This material included feedback from Local Authorities who had tested earlier versions of the standards (n = 10) (Schuder et al., 2021). We then identified key gaps in this evidence base and conducted targeted (non-systematic) searches of grey and academic literature sources (Web of Science, Google Scholar) to identify additional evidence on the application of quantitative GI standards globally. For example, we searched for evidence underpinning targets for total area of GI and specific GI types such as tree cover and recreational space. This was complemented by a scoping review of the academic literature on GI quality standards, focusing on developing a more detailed understanding of the socio-cultural, economic, and ecological interpretations of what “quality and qualities” GI was reported to hold within academic and practitioner debates (Mell, 2022). Current articulations of quality from this review were evaluated and fed back to Natural England to support the development of the Core Menu and GI Standards more widely.

This evidence base informed our initial proposals for the design of the Core Menu, and was used as the basis for gathering further feedback through semi-structured interviews with LPAs (n = 6), to draw on practical experience (Grace and Smith, 2022a). The standards were then further refined through a four-fold process: i) discussions within the research team, ii) a structured and facilitated integration workshop with stakeholders, iii) consultation and discussion with Natural England, Defra, and other GI stakeholder experts, and iv) feedback from Natural England’s GI steering and advisory groups. Finally, Natural England commissioned an ongoing evaluation programme focused on local authorities and developers (LIVE Economics, 2022; ICF Consulting Services Limited and Live Economics Ltd, 2024).

2.3 Developing additional tiers of standards

To complement the Core Menu, we considered the feasibility of developing a single overarching standard, such as the total percentage of green space in an area, to provide a simpler ‘headline’ metric for local authorities to communicate their progress. However, feedback from stakeholders and the Steering and Advisory Groups highlighted that this could be counter-productive, as it could lead to a focus on quantity of green space at the expense of quality and multi-functionality. For example, an area with a high proportion of green space could contain mainly short-mown playing fields, which would deliver a specific type of recreational benefit but have little value for biodiversity, urban cooling, air quality enhancement and carbon sequestration. This is a common trade-off within GI debates, where the use of simple quantitative metrics is critiqued as it can fail to reflect local needs (Dinand Ekkel and de Vries, 2017). Instead, we recommended using a suite of ‘headline standards’ covering multiple aspects of GI in line with recommendations from other reviews (e.g., Korkou et al., 2023). Natural England therefore developed a set of Headline Standards that are ‘owned’ by government and its agencies to avoid any perceived bias towards or against existing standards developed by non-governmental organisations. In addition, although the Core Menu was restricted to the minimum set of standards needed to meet the five descriptive principles of good GI, Natural England also decided to signpost a much wider set of standards and guidance in a separate table. Therefore, a three-tiered structure was adopted:

1. Headline standards. Five overarching standards developed by government and its agencies, informed by the indicators in the Core Menu.

2. Core Menu. A targeted menu including a more comprehensive range of green infrastructure standards, tools and best practice checklists, which can be used for in-depth green infrastructure planning to ensure that the five principles describing good green infrastructure are delivered (to be tested further before launching).

3. Signposting table. A table signposting a wider range of possible additional standards and guidance documents that stakeholders could find useful (in development by Natural England). Each item is matched to the relevant GI Principles, and context (e.g., new development or existing GI) and area type, from city centre to rural, enabling users to identify the most appropriate standards, benchmarks and indicators for their purpose.

The first version of the GI Framework was published in January 2023, including the Headline Standards (Houghton and Warburton, 2023; Natural England, 2023b). The Core Menu and Signposting table will be released later after final testing and refinement.

3 Results

Here we summarise the standards that were selected for inclusion in each of the five categories of the Core Menu (Section 3.1), and then describe the information included in the user guidance for each category (Section 3.2). Finally, we describe the five Headline Standards and evaluate them based on user feedback so far (Section 3.3).

3.1 Standards included in the core menu

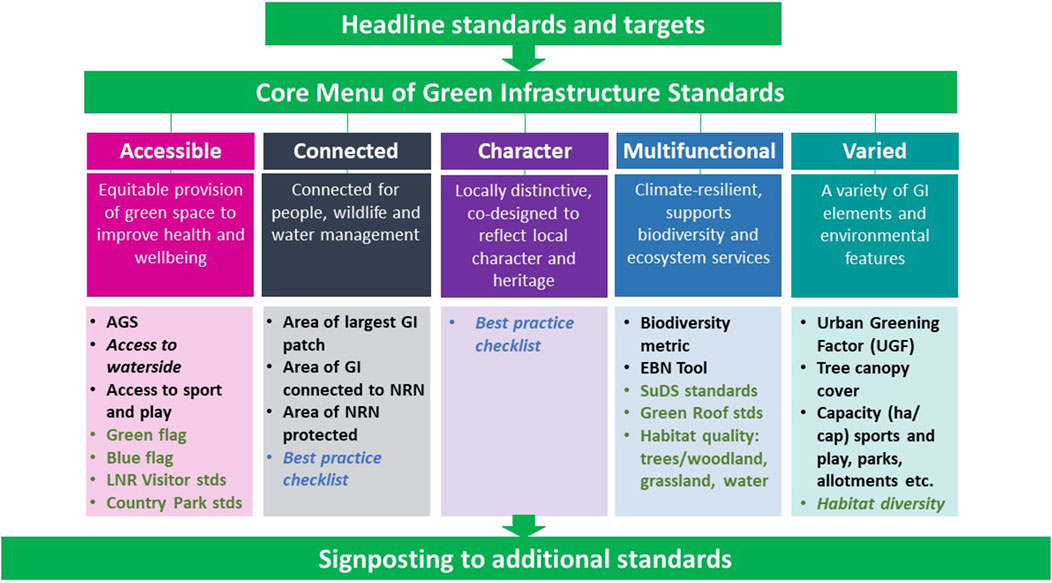

Standards selected for the Core Menu include a mix of quantitative standards, qualitative standards, and checklists (Figure 2). As far as possible, we selected existing standards that are already widely used and recognised by practitioners in England, developed by a range of organisations. However, there were gaps for the “Character” and “Connected” standards where new checklists were developed to ensure that the principles were fully covered. Below we summarise the core standards selected to meet each of the five descriptive principles. Full details of all standards are in the Supplementary Information (SI).

Figure 2. The Core Menu of standards, structured under the five descriptive principles. AGS, Accessible Greenspace Standards; LNR, Local Nature Reserves; NRN, Nature Recovery Network; EBN Tool, Environmental Benefits from Nature Tool. Black text, quantitative standards, green, qualitative standards, blue, checklists.

3.1.1 Accessible GI

Standards focus on providing equitable access to green space. The main standard is Natural England’s Accessible Greenspace Standards (AGS), which incorporates measures of proximity to different sizes of green space, capacity (i.e., quantity of accessible greenspace per person), quality (the Green Flag (2024) criteria), inclusion and access for all. This forms one of the Headline Standards (see Section 3.3.2 for more detail). It is complemented by an Access to Waterside measure and separate standards for provision of adequate sport and play facilities. Additional quality standards for specific types of green space include the Blue Flag (for beach and bathing water quality), Local Nature Reserve Visitor Service Standards, and Country Park Accreditation standards (see SI for details). In addition to covering the quantity and quality of GI, several of these standards also include process guidance covering issues such as governance, monitoring and stakeholder engagement.

3.1.2 Connected GI

Relates to three types of connections: for people, via active travel networks of footpaths, cyclepaths and bridleways (including public rights of way); for wildlife, via ecological corridors enabling species to move around the landscape; and for water, such as by linking urban Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) with Natural Flood Management schemes in the wider landscape. No single metric captures connectivity unambiguously, so we use a set of three quantitative standards: the area of the largest patch of green space in an area; the area of GI connected to a wider nature recovery network beyond the urban area, and the area of the nature recovery network that is protected. These reflect the overall aim to link smaller spaces together to form larger connected areas that are linked into Local Nature Recovery Networks, currently being developed across England as part of the statutory Local Nature Recovery Strategies mandated by the Environment Act (2021). We have also compiled a best practice checklist showing how to deliver connected GI in new developments and across an existing area (see SI).

3.1.3 Character

Refers to the need for GI to be locally distinctive and co-designed with local communities to respond to local character and heritage. As there were no overarching existing standards for this, we developed a checklist (see SI) drawing together existing relevant guidance to help planners co-design GI with local communities, support local priority species and habitats, respect existing descriptions of local characteristics (known as Local and National Character Areas and Landscape Character), incorporate cultural heritage, and protect existing cultural and historic features.

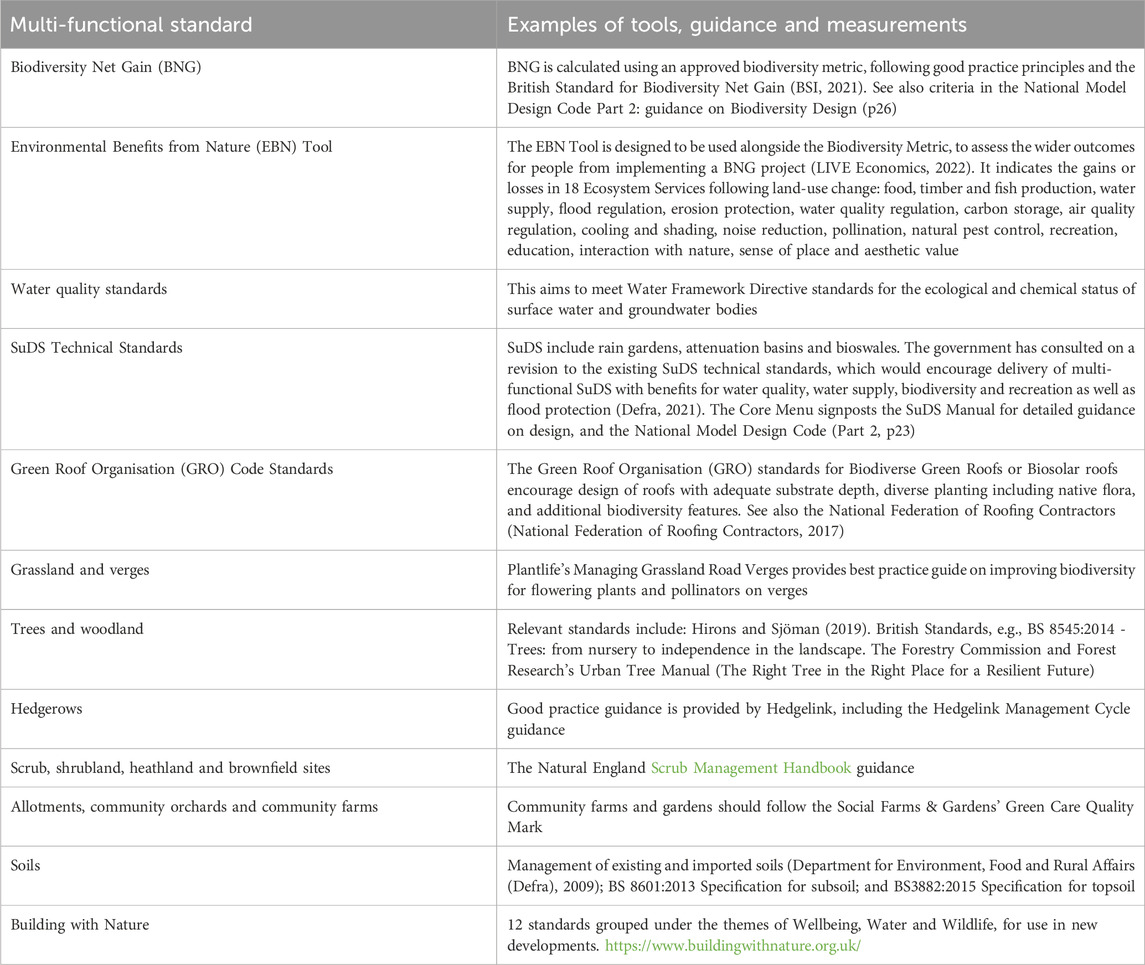

3.1.4 Multifunctional

Refers to designing GI so that it can deliver multiple functions at the same time, addressing the climate and biodiversity crises as well as supporting health and communities. Quality standards are particularly important, as high-quality GI can deliver multiple benefits. Biodiversity and ecosystem health are crucial for delivering multiple benefits in the long term, so delivery of Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) in new developments using the government’s Biodiversity Metric is a key standard. Unlike most of the standards, delivering BNG is now mandatory in England via the 2021 Environment Act (Natural England, 2024). The menu also includes a complementary tool intended to help design BNG schemes with positive outcomes across a wide range of ecosystem services: the Environmental Benefits from Nature (EBN) Tool (Smith et al., 2021). In addition, we include standards for multifunctional Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) that have benefits for water quality, biodiversity and amenity as well as for runoff management; a standard to encourage high quality green roofs with multiple benefits for biodiversity, cooling and water management (the Green Roof Organisation, 2021 Biodiverse Green Roof standard); and quality standards for soils, water, trees, woodland, urban grasslands, hedgerows, scrub, heathland, brownfield sites and urban food-growing areas (allotments, community orchards and community farms). A strategic approach to planning GI is vital for delivering multifunctionality, so a process-based GI Strategy Standard was included in the Headline Standards (see below). All these standards can also be implemented in the framework of “Building with Nature”, a well-established process-based standard that encourages multifunctionality (Jerome et al., 2019).

3.1.5 Varied

Reflects the need to deliver a diverse mix of different types of GI to meet local needs. This menu includes mainly quantitative standards. It includes the Urban Greening Factor (UGF) tool, which sums the areas of different GI types within a development weighted by scores reflecting their benefits (see Section 3.3.4), as well as tree cover standards, a habitat diversity index, and capacity standards (hectares per 1,000 people) to ensure a mix of play areas, sports fields, parks, allotments, and natural green spaces. See SI for more detail.

3.2 User guidance for the core menu of standards

Supporting guidance was developed to help users navigate and understand the Core Menu of standards, in a format that could be presented in a web-based interface (see SI). For each of the five categories, this includes an overview summarising key benefits that could be delivered by the standards, showing how they help to meet both national policies and global targets (including the UN SDGs), and listing any synergies or trade-offs with the standards in the other four categories. The individual standards in the category are briefly described, with links to full details.

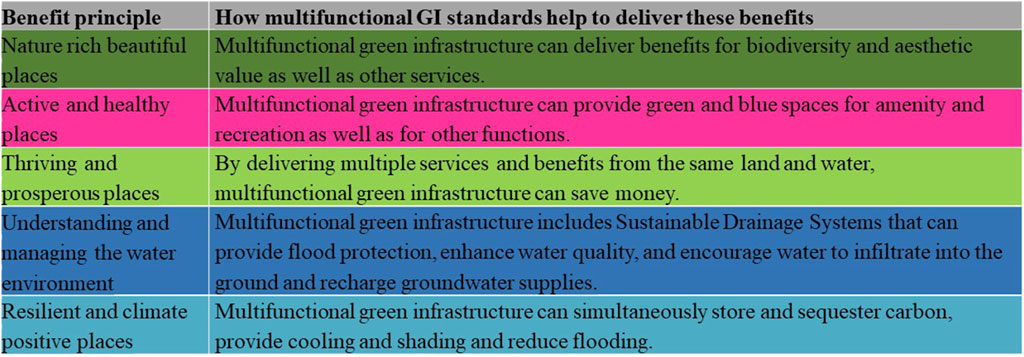

For example, for the Multifunctionality standards, the guidance states the aim to ensure that GI should be climate-resilient, support biodiversity, and deliver a wide range of ecosystem services, and emphasizes that delivering multiple benefits from the same space is especially important where the total area of GI is limited. It lists benefits delivered by multifunctionality (Figure 3) and shows how it delivers 18 SDG targets. It also shows that it supports two goals from the ‘Building for a Healthy Life’ guidance developed by Homes England, a government agency for delivering housing (“Healthy streets” and “Landscape layers that add sensory richness to a place”) (Birkbeck et al., 2020). Each of the individual multifunctionality standards are then described (Table 3).

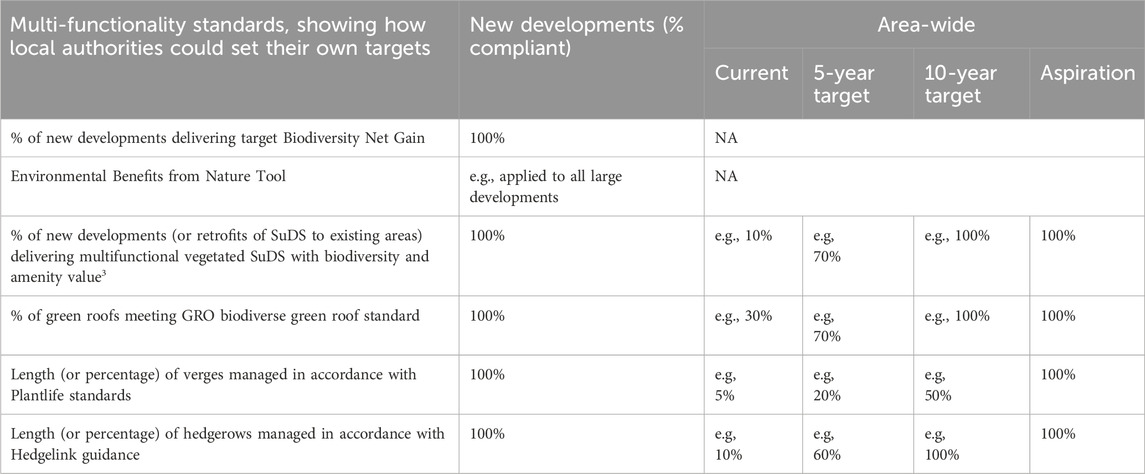

Figure 3. How the Multi-functional GI standards deliver the five GI benefit principles. Colour coding matches Figure 1.

Next the guidance addresses the issue of what level the standards should be set at. Feedback from users stressed the need to account for different local contexts, resources, needs and constraints, rather than setting a prescriptive level for every standard. Therefore, we suggested that local authorities should be invited to measure their baselines and then set their own targets for working towards fully meeting the aspirational standards over a set. The user guidance provides a template table for setting targets both for individual new developments and for the wider area governed by the local authority, to reflect the potential to create or enhance GI in existing urban areas and account for the cumulative impact of individual developments. The template suggests setting targets for a certain percentage area of new developments or existing GI to meet each standard. This flexible approach can encompass quantitative and qualitative standards, checklists, and process-based standards. For example, for Multifunctionality the template table suggests setting targets for the percentage area of new developments that use the EBN Tool to design better outcomes for ecosystem services, or the percentage length of roadside verges or hedgerows managed according to recommended guidance (Table 4).

Table 4. Template for Local Authorities to set their own targets, with examples for Multifunctionality Standards.

3.3 The five headline standards

Based upon the evidence reviews, workshops and interviews with users, we recommended an initial suite of five headline standards (not directly mapped to the five descriptive principles): i) an accessibility indicator, ii) targets for overall green space and the proportion that should be nature-rich, iii) no net loss of trees and green space (to prevent a ‘race to the bottom’ in areas that already exceed the green space target), iv) minimum 2 ha green space per 1,000 people, and v) an Urban Greening Factor score threshold for new developments. In addition, it was suggested that having a robust Green Infrastructure Strategy should be part of the headline standards.

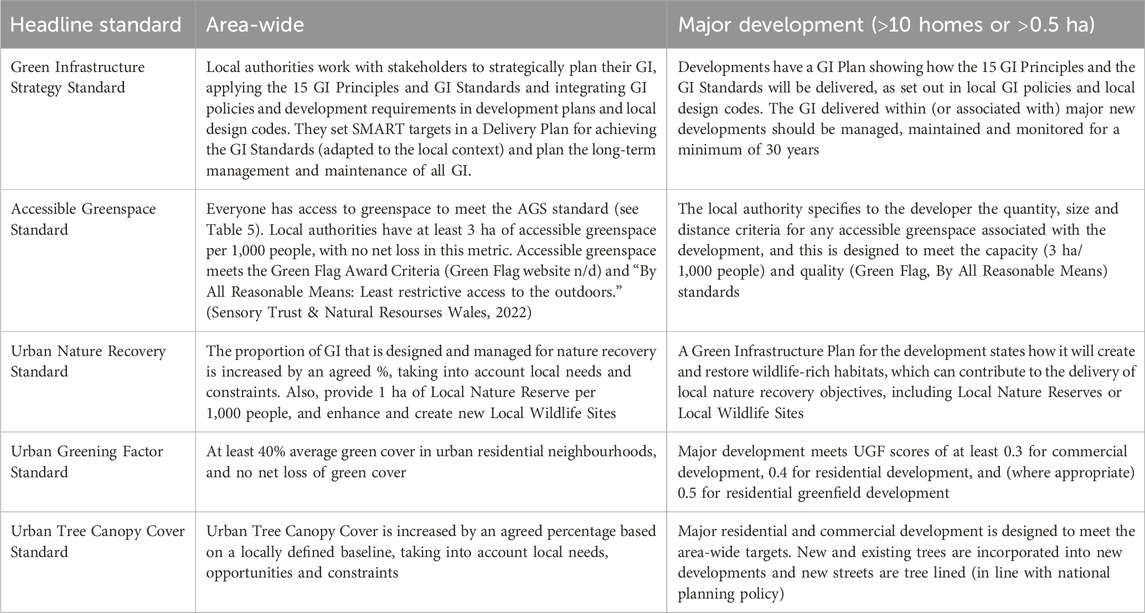

Following further internal discussions, Natural England adapted these suggestions into five revised Headline Standards: GI Strategy, Accessible Greenspace, Urban Nature Recovery, Urban Greening Factor and Urban Tree Canopy Cover (Houghton and Warburton, 2023) (Table 5). These Headline Standards respond to Government policy (e.g., the 25 Year Environment Plan and National Planning Policy Framework) and aim to provide clear, high-level standards for quantity, quality, proximity, capacity and, importantly, process, that will support planning and delivery of good GI. They aim to provide an easy-to-use set of measurable standards with supporting evidence and analysis that busy planners, communities and developers can use alongside the GI Planning and Design Guide, the GI Process Guides and the Core Menu to assess, plan, monitor and evaluate local GI networks. The Core Menu provides a more comprehensive set of GI standards, which complements and supports the Headline Standards at a more detailed level, linking directly to the five Descriptive Principles (accessibility, connectivity, character, multi-functionality and variety), and to GI quality. When used together to strategically plan GI, the Headline Standards, Core Menu and other GI Framework tools will complement and reinforce each other, and can deliver multiple benefits to meet local needs (meeting the five Benefits Principles).

Table 5. Summary of the five Green Infrastructure Headline Standards (Link to GI Headline Standards (Houghton and Warburton, 2023) https://designatedsites.naturalengland.org.uk/GreenInfrastructure/GIStandards.aspx).

Below we describe and critically evaluate each Headline Standard drawing on the feedback gathered in our research, with a particular focus on the longest-established standards (the Accessible Greenspace Standard and Urban Greening Factor) where more feedback is available.

3.3.1 GI Strategy Standard

The GI Strategy Standard is a process-based standard that requires local authorities to strategically plan their GI in partnership with local communities and other stakeholders across different sectors, to enable GI to contribute to a wide range of social, economic and environmental policies. It is fundamental to the delivery of the other standards, especially for delivering multifunctionality over the long term.

The standard states that GI advocates should apply the 15 GI principles to integrate GI policies into development plans and local design codes, and to plan the delivery, long-term management and maintenance of GI. As such, the GI Strategy, the other four Headline Standards, the Core Menu of standards and the GI Planning and Design Guide are mutually interdependent—the GI Strategy can motivate implementation of the other standards, and the standards are key tools for supporting local authorities to deliver their GI Strategy by ensuring that their GI can deliver the 15 principles.

The GI Strategy plays a key role in implementing the five Process Principles (Table 2). It requires a Delivery Plan that should set SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound) targets for achieving the GI Standards, adapted to the local context. For individual development sites, it recommends a GI Plan showing how the 15 GI Principles and the GI Standards will be delivered, as set out in local GI policies and local design codes, and how the GI associated with major new developments should be managed, maintained and monitored for at least 30 years.

3.3.2 Accessible Greenspace Standard

The accessible greenspace headline standard consists of three elements covering i) size and distance, ii) capacity (3 ha of green space per 1,000 people) and iii) quality (Green Flag criteria for high quality parks, and inclusive access for all based on two key guides (Houghton and Warburton, 2023; Houghton, 2024; Sensory Trust and Natural Resources Wales, 2022).

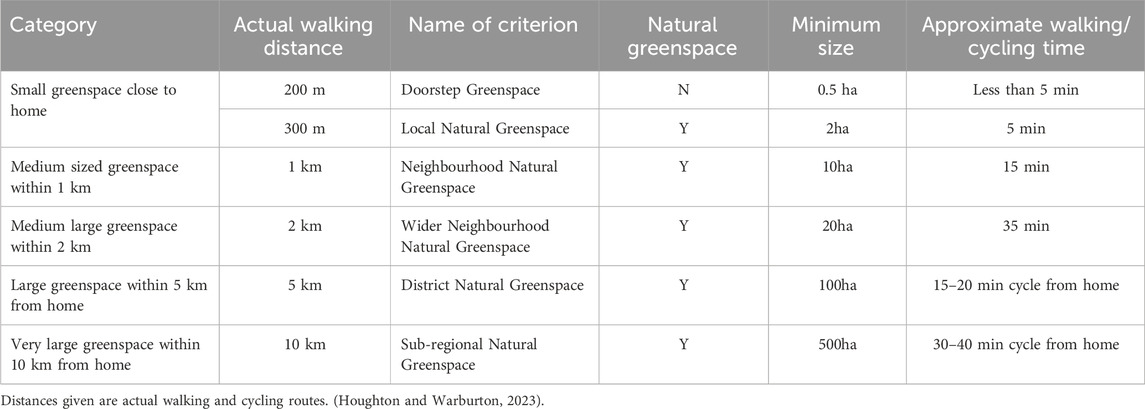

The size-distance element was based on the original Accessible Natural Greenspace Standard (ANGSt), which had been the default accessibility metric for planning in England since its creation in 1995. This measured access to greenspace using a simple, yet effective, set of criteria based on the size of the green space, the distance from residents, and the time required to walk there. Criteria were originally set for provision of four size/distances of accessible natural greenspace:

• at least one accessible natural greenspace site of 2 ha or more within 300 m or 5 min’ walk from home

• a 20ha site within 2 km

• a 100ha site within 5 km

• a 500ha site within 10 km.

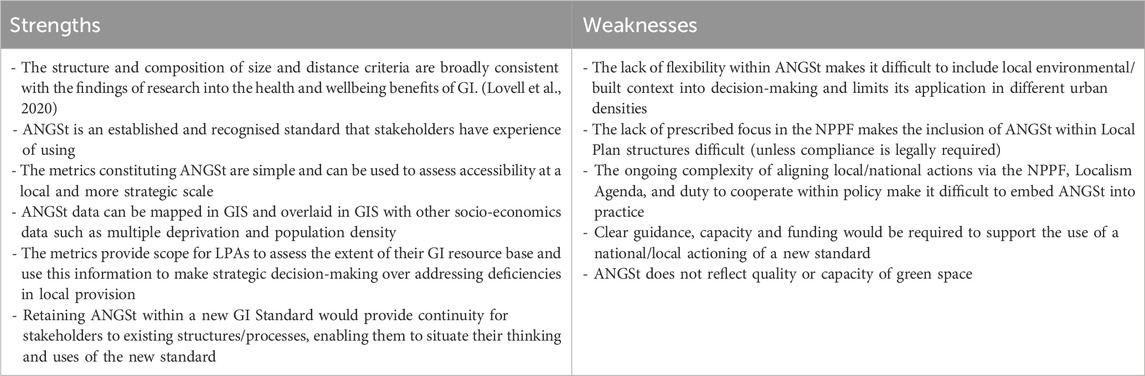

During development of the GI Standards, a review of the grey and academic literature suggested that ANGSt had retained its relevance because it was a well-established and easy-to-use tool, with a lack of alternative metrics. The size and distance hierarchy approach is supported by an evidence review which concluded that “different types, sizes and configurations of green infrastructure afford different benefits” and that “mixed provision is most likely to be beneficial” (Lovell et al., 2020). The simple size/distance/time metrics enabled users to map and assess accessibility and identify gaps in provision relatively easily using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) (Pauleit et al., 2003; Wysmułek et al., 2020). Yet engagement levels by Local Authorities varied, with some using ANGSt as a simple spatial tool to understand existing provision, and others performing detailed (and more complex) analyses of local greenspace accessibility or using ANGSt as a benchmark against which locally specific metrics can be tested. Research questioned whether greater nuance was needed to adapt ANGSt to contemporary planning, with a growing call for increased flexibility in the approach taken to accessibility that is more reflective of local environmental, socio-economic, and planning contexts (Schuder et al., 2021; Whitten, 2022). The strengths and weaknesses of ANGSt identified by the research are summarised in Table 6.

Table 6. Strengths and weaknesses of the original ANGSt for aligning local/national objectives within a GI Standard.

These findings were reinforced by interviews with local authorities (n = 6) with none expressing strong support for ANGSt because it did not fit all local contexts. For example, one council had significant accessible green space, but major problems with quality, while another had severe constraints on proximity, with 50% of the area over 5 min from a green space. Several councils also applied capacity standards (hectares of green space per capita), seen as important for avoiding over-crowding and over-use of green space in dense urban areas. Most commonly, they used a version of the Six Acre Standard, developed by the non-governmental organisation Fields in Trust (2016), a recommended minimum standard of six acres (2.75 ha) of sports, recreation and/or open space per 1,000 people. For allotments and sports facilities, however, some councils felt that a more bespoke approach was needed to reflect demand, such as the number of local sports teams, rather than population size. Alternative approaches include more sophisticated strategies for assessing needs and the quantity of greenspace suggested by Sport England (2014).

Natural England therefore revised ANGSt and renamed it the Accessible Greenspace Standard (AGS). First, they added two additional categories of greenspace of different sizes—Doorstep and Neighbourhood (Table 7). This aimed to increase the focus on greenspaces close to home, supporting the Government’s Environmental Improvement Plan commitment to improve access to nature while encouraging walking and cycling for health and wellbeing, and thus also reducing air pollution and carbon emissions from cars. In line with this, the revised standard encourages users to use network analysis to determine actual walking distances to the nearest access point, rather than straight-line distances. The term ‘natural’ was dropped from the name because nature recovery goals were separated out into the new Urban Nature Recovery standard.

While these standards are ambitious, given that only 62% of people currently live within 15 min from accessible green space (Moss, 2023c), they aim to provide scope for planners and developers to deliver greenspace of varying sizes, functions and qualities that are locally appropriate. This was emphasized through a second major change: the guidance for the Headline Standards states that ‘In assessing and strategically planning their green infrastructure provision, local authorities can apply the GI Standards locally, adapting them to local context where appropriate, and setting local GI standards.’ Supported by the GI Mapping Database, which maps achievement of the criteria across England in relation to deprivation and population density, the standards can thus be used as benchmarks to support local analysis of needs and identify priority areas for action.

The third major change was the addition of quality, capacity and inclusivity elements to the size-distance metrics (Table 5). This partly responds to research showing that local needs can be better addressed via discussions on accessibility rather than through a uniform assessment of greenspace size, distance and capacity (De Sousa Silva et al., 2018; Mell and Whitten, 2021). This includes integrating local understanding on access points, quality, amenity, landscape context, landscape diversity, aesthetic value, functions, and socio-economic and demographic variables. For example, perceptions of accessibility may differ from the simple measure of distance or time to green space if they do not feel safe and welcome (Larson et al., 2016). However, this more nuanced assessment of accessibility based on local needs and constraints requires more data, time and resources, which may not be available given local authority budgetary constraints.

The other Headline and Core Menu standards can complement the AGS. For example, there is evidence that greater health and well-being benefits are delivered by more nature-rich green space (Smith et al., 2023; Wood et al., 2019), highlighting the importance of the Urban Nature Recovery headline standard. The Urban Greening Factor Headline Standard and the Core Menu standards for Multifunctional and Varied GI also play a part in delivering a range of ecological and socio-economic amenities, functions and landscapes, including cool green and blue space and sustainable drainage to help people adapt to climate change, although expertise is needed to balance ecological quality with socio-economic function. This has been central to discussions of ecologically and water-focused GI work in North America and China (Cheshmehzangi, 2022; Grabowski et al., 2022). This holistic approach has been taken up more widely in the United Kingdom, with the Greenspace Toolkit developed by Natural Resources Wales and the inclusion of Building with Nature principles in the 2024 revisions to Planning Policy Wales Edition 12 (Natural Resources Wales, 2010; Welsh Government, 2024).

Evaluation by Natural England with LPAs (n = 14) and (developers n = 17) showed that these amendments were welcomed, especially the flexibility to set local standards. Feedback said that the AGS was user friendly, the links with the nature recovery Headline Standard were useful, and it was a useful evidence base for local plan preparation. A lack of guidance and training opportunities for LPAs was mentioned and is now being addressed, including a User Guide (Houghton, 2024). However, there was still felt to be a lack of deliverability in dense urban areas and a lack of benchmarks for challenging spaces, e.g., areas with little publicly owned land (though the Urban Greening Factor Standard can be helpful in those cases).

Comparable size-distance metrics have been applied in other countries, including China (300 m to a greenspace and 500 m to a park), Japan (10 m2 of GI per person and 3% of total urban area should be GI), the US ParkScore evaluation method, New York Green Infrastructure Plan (10 min walk to GI), and India Urban Greening Guidelines (area metrics for parks, forests, and playgrounds) (Larson et al., 2022; Mell, 2016; Zhou et al., 2021). These show that the discussions used to structure the AGS are being considered in geographically complex locations.

3.3.3 Urban Nature Recovery Standard

The Urban Nature Recovery standard states that the proportion of GI that is designed and managed for nature recovery should be increased by an agreed percentage and should consider local needs and constraints. New developments should also have a GI Plan showing how they will create and restore wildlife rich habitats which can contribute to the delivery of these local nature recovery objectives. In addition, there should be 1 ha of Local Nature Reserve per 1,000 people alongside enhancing or creating more Local Wildlife Sites. This recognises that Local Nature Reserves, intentionally designed to bring people in urban areas into contact with nature, are an integral part of GI networks for people as well as contributing to Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS) under the Environment Act (2021).

This standard responds to the United Kingdom government’s national and international targets to protect 30% of land for nature by 2030 and reverse species loss (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022). Although much urban GI may be unsuitable for contributing directly to the ‘30 × 30’ target, it can play a key role by providing space and corridors for wildlife to move through the highly fragmented United Kingdom landscape, helping species adapt to climate change and enabling more people to experience nature. Yet GI does not always meet the definition of a Nature-based Solution, in that it should deliver benefits for biodiversity (IUCN, 2020; Seddon et al., 2021). Outcomes for nature are often ignored or taken as a given. The Urban Nature Recovery Standard, accompanied by a User Guide (Houghton et al., 2024) and supported by elements of the Core Menu for Multifunctionality, makes this requirement more explicit.

In interviews, several LPAs emphasised that standards need to deliver high quality, nature-rich and multi-functional GI as well as a minimum area requirement, but there was also a clear message from metropolitan authorities on the difficulty of delivering enough GI in dense inner urban areas. As with the other Headline Standards, Local Authorities can adapt the standards to the local context. However, this flexibility to set lower targets can further disadvantage deprived or minority inner urban communities, where there are clear inequalities in the provision of greenspace and tree canopy cover compared to high-income, gentrified places (Kiani et al., 2023; Jarvis et al., 2020). As mentioned above, the GI Mapping Database maps greenspace provision against deprivation and ethnicity, enabling planners to address greenspace access inequalities (often associated with health inequalities).

The discussion of access to nature during COVID-19 placed health and greenspace inequalities at the forefront of GI planning, noting numerous examples of place-based inequality (Burnett et al., 2022; Pan et al., 2021). This may be compounded by uncertainties in extrapolating evidence from one population or place to another, especially for the more vulnerable, due to differing environmental factors and population variables (Spickett et al., 2013). Addressing these inequities through standards can help deliver strategic ambitions, but decision makers need to be aware of the risk of bias and inequalities, as weaknesses in ethical frameworks for standards can disadvantage less powerful stakeholders (Haugen et al., 2017).

Even within national guidance, the tension between competing policy objectives makes the application of standards a matter of local judgement. Delivering 30 × 30 should be a collaborative, voluntary effort, led by those who are driving nature’s recovery on the ground (Brummitt and Araujo, 2024). However, the lack of statutory protection for newly created habitats, and a provision for landowners or land managers to withdraw at any point, risks undermining the achievement of the target.

3.3.4 Urban greening factor standard

The Urban Greening Factor Standard covers both the total area of green space in a local authority area and the UGF scores of individual developments. Various studies from around the world suggest setting an overarching ambition for the total percentage of green cover in an urban area (e.g., Osmond and Shafiri, 2017, for urban cooling), but differences in the local context make this challenging. In the United Kingdom, the percentage of green cover is highly sensitive to the position of the urban boundary, with some dense urban areas that include peri-urban open land easily exceeding 40% or 50% of green cover, while those with tight boundaries have substantially less. Setting a minimum standard also risks a ‘race to the bottom’ in areas where the standard is exceeded. Therefore, following feedback from local authority interviews, the UGF headline standard specifies a target of 40% average green cover in urban residential neighbourhoods (thus excluding peripheral rural areas and dense city centres), together with no net loss of green cover (to prevent a race to the bottom).

For new developments, the standard applies a UGF threshold. UGFs aim to assess the proportion of green cover in an area, with a score (weighting) to indicate the quality and multifunctionality of each type of feature. They were first developed in the late 1990s, primarily to reduce surface runoff and the urban heat island. The first example was the Biotopflächenfaktor (Biotope Area Factor) in Berlin, which aimed to combat growing urban densification. This has generally been viewed positively by city planners, architects and developers for its simplicity and flexibility (Grant, 2017) and as a valuable transferable tool for translating landscape design standards into planning regulations, though it has also been viewed as too procedurally intense (Vartholomaios, 2013). It inspired the Grönytefaktor (Green Space Factor) used for experimental and creative planning in Malmö (Sweden), and other UGFs adopted by cities in Europe, Asia, North America and Australia. UGFs are increasingly being used in the United Kingdom by LPAs in the revision of their local plans and have become a prominent policy tool for urban greening across Greater London through the adopted London Plan (Mayor of London, 2021).

These existing UGFs were reviewed by the research team to develop a Model UGF for England as part of the Core Menu (Neal, 2023b). We assessed their development and current application; their role in promoting ecosystem services; the specific metrics they use; their ability to meet local needs; and their capacity to inform national and local GI targets. The Model UGF for England includes 22 different surface cover types grouped under four key headings: Vegetation and Tree Planting, Green Roofs and Walls, Sustainable Drainage Systems and Water Features, and Paved Surfaces. A weighting factor from 0.0 to 1.0 is assigned to each cover type reflecting its environmental and social value in urban greening; its functionality in providing ecosystem services, including improving permeability; and its benefit in supporting biodiversity and habitat creation. Detailed guidance for each cover type is provided in a User Guide that sets out their design and specification and the method of measurement (Natural England and Neal, 2023).

The UGF score is calculated by adding up the area of each GI element multiplied by its weighting and dividing by the total area within the development site boundary, commonly referred to as the red-line boundary. Target UGF scores for different types of development (residential, commercial, etc.) should be set by planning policy (Table 3). These targets can be considered as minimum benchmarks intended to set a level playing field for development but may also be adapted to local context as required. Planning policies should state that development schemes are expected to meet or exceed these targets to demonstrate the positive contribution their design proposals will have on both urban greening and wider planning policies to achieve sustainable development.

The increasing use of UGF tools suggests that they are perceived to be both beneficial and effective in improving the provision of GI. The London UGF withstood formal scrutiny during review of the London Plan (Planning Inspectorate, 2019). Sites in Malmö and Seattle describe the positive influence of UGFs on ecological and aesthetic design (Neal, 2023b).

The unified rating and metric establish a practical instrument that combines multiple ecosystem services within a simple set of land covers and metrics. However, this can mask gains and losses in individual ecosystem services, which could instead be explored using the EBN Tool. The simplified land cover categories may also mask important differences, e.g., between existing mature trees or new trees, and native or non-native species. As the UGF does not take account of loss of pre-existing land cover, it needs to be applied in conjunction with a Biodiversity Metric. However, it is well-suited to assessing developments with a low biodiversity baseline.

A clear benefit of the UGF tool is that it promotes a collaborative approach to GI planning that is both “flexible and easy to understand” (Massini and Smith, 2018). Local authorities can establish the policy and set factor targets that meet the needs of a district, developers can engage through design and dialogue to meet the objectives and communities can ultimately benefit from GI that is better planned and is more functional.

Interviews with local authorities confirmed these findings, with three councils either already applying a UGF or looking to develop one. In one case a UGF was successfully used as a benchmark to challenge developers over the low provision of GI. UGFs are particularly relevant in dense urban districts that are often unable to meet prescribed accessibility standards due to lack of space. One council said a UGF can be used to determine the area of green space needed, and developers can then be required to ensure that this is publicly accessible to meet AGS targets for hectares of accessible green space per 1,000 people.

3.3.5 Urban tree canopy cover standard

This standard specifies that urban tree canopy cover is increased by an agreed percentage based on a locally defined baseline, taking into account local needs, opportunities and constraints, and that new developments have tree-lined streets.

Tree planting has now become rooted in national policies as a response to climate change as well as for other benefits. Trees intercept rainwater, filter out pollution and aid infiltration into the ground, helping to reduce surface flooding. This alleviates pressure on drainage and water treatment systems, especially as part of a wider system of SuDS and/or natural flood management. The addition of a street tree could reduce stormwater runoff by between 50% and 62% in a 9 m2 area, compared with asphalt alone (Armson et al., 2013). Trees also store and sequester carbon and help communities adapt to climate impacts through urban cooling. Tree planting could reduce maximum surface temperature by between 0.5 and 2.3°C (Hall et al., 2012). A single large tree can transpire 450 litres of water in a day which uses 1,000 mega joules of heat energy, making urban trees an effective way to reduce urban temperature (Bolund and Hunhammar 1999). However, there can be trade-offs if water is required for irrigation (Rambhia et al., 2023).

One challenge with setting a tree canopy target is that local authorities have widely differing baselines, with current tree cover ranging between 4% and 42% (Sales et al., 2023). Various sources suggest a tree cover target of 15%–30% for urban areas (e.g., Konijnendijk, 2021; Osmond and Shafiri, 2017; Grace and Smith, 2022b; Supplementary Appendix A5) based on the multiple benefits for climate, biodiversity and health. Our research suggested working towards quantitative targets of 20% minimum (Sales et al., 2023) and 30% aspirational tree cover. This was preferred to specifying a fixed percentage increase, which would produce very low targets for areas with low tree cover. For example, a 10% increase in an area with 5% tree cover will be only 5.5%. Meanwhile, an area that already has 30% tree cover would need to increase this to 33%, risking the loss of space needed for other habitats such as semi-natural grassland or wetland, and other GI such as allotments and play spaces. This could jeopardise the principle of delivering Varied GI. We also specified that there should be no net loss of canopy cover, to avoid the risk that an area above the minimum target (e.g., having 33% tree cover) might feel justified in removing existing trees.

However, stakeholders were concerned that setting a standardised target could disincentivise action in areas currently far below the target. Councils had faced challenges in agreeing standards for tree canopy cover at both county and site scale. One felt that a uniform standard of 30% tree canopy cover could result in the loss of other GI assets.

Therefore, the Headline Standard requires urban tree canopy cover to be increased by a locally agreed percentage based on a local baseline, considering local needs, opportunities and constraints. Major new residential and commercial developments should be designed to meet these area-wide targets, incorporating new and existing trees and ensuring that new streets are tree lined. Specifying an increase removes the need to specify no net loss. This gives flexibility to councils to set locally appropriate targets - for example, they can specify how many trees should be incorporated in a new development - but also introduces uncertainty and a risk of under-ambition. For example, how many trees need to be included in a new street for it to qualify as “tree-lined”? These tensions are discussed further below.

4 Discussion

Drawing on feedback from local authorities and the Steering and Advisory Groups, in this section we discuss the strengths, challenges, tensions and trade-offs associated with application of the GI Standards as a whole, with a particular focus on the challenges around determining the level at which to set the standards. We consider the role of governance and look ahead to how some of the practical challenges in planning and assessing GI could be addressed through the use of digital data and mapping.

4.1 Overall strengths of the GI standards

The GI Standards have several key strengths that help to deliver more and higher-quality GI. First, they take a holistic approach that considers all aspects of good GI, including quality, accessibility, connectivity, local character and multifunctionality, rather than just the overall area of green space. This meets the needs expressed by several Local Authorities engaged in developing the standards to deliver high quality, nature-rich and multifunctional GI–something that is rarely implemented in practice, despite decades of research (Cook et al., 2024). The GI Standards encourage a more comprehensive and strategic approach, working across sectors and departmental silos to enable GI to contribute to a wide range of social, economic and environmental policies, as set out in the GI Strategy Standard. The five pillars of the Core Menu (Accessible, Connected, Local Character, Multifunctional, Varied) are not weighted or traded off against each other (c.f. Dang et al., 2020). Instead, the menu recognises that all five elements are important and can support each other synergistically. For example, for climate adaptation, Multifunctionality standards can deliver urban cooling and flood protection, supported by Accessible and Varied green space to optimise public health benefits, thus reducing the vulnerability of the population to climate impacts such as urban heat. The Connectivity standards provide ecological corridors helping wildlife to adapt, and the Character standards can deliver socio-economic benefits such as jobs and income from tourism (e.g., Epifani et al., 2017) which also strengthens community resilience to climate change.

Second, the GI Standards were informed by evidence and co-designed iteratively with stakeholders, taking note of feedback and adjusting the evolving standards accordingly (Table 1). Demonstrating policy is evidence-based is a key requirement in the NPPF and for local authorities, so helping give greater weight to GI delivery at local plan examinations and public inquiries.

Thirdly, the Core Menu follows a clear and logical structure. It rationalises a myriad of existing standards and guidance from many sources into a concise, coherent and comprehensive framework, based on Natural England’s fifteen principles of good GI, to help users assess current provision and ensure they are delivering the full range of potential benefits from limited urban spaces.

Fourthly, a hierarchical approach is used to balance comprehensiveness with simplicity, catering for the needs and preferences of different users. The five Headline Standards provide a framework of simple, measurable targets that can be linked to local planning and other policy. As they do not explicitly cover all aspects of GI, such as connectedness, local character and multifunctionality, the Core Menu supports them with the full set of standards needed to meet all 15 principles. This provides Local Authorities with the tools needed to assess the current state of their GI and inform target-setting in their GI Strategies. For connectivity and local character, where existing standards were not available, the Core Menu adopts a checklist approach which could be built into local design guides or related policies. For users looking for alternative or additional tools, the signposting table adds a third level of detail.

Finally, the GI Standards are embedded within the GI Framework, where the whole is more than the sum of the parts for practitioners. They are supported by the GI principles, the practical advice in the Planning and Design Guide, the Process Guides, GI Mapping Database, Case Studies and training webinars, as well as one-to-one guidance and advice.

4.2 Uptake in national and local policy

As the strengths of the GI Standards have become recognized, they are being taken up into national policy. For example, the Environmental Improvement Plan 2023 endorses the standards in the GI Framework to help local planning authorities, planners, and developers create or improve GI, particularly where provision is poorest, and includes a commitment that all homes should be within 15 min of a natural green space. The National Model Design Code advises applying the GI Framework and its Standards to “green our towns and cities … through incorporating GI into development” (MHCLG, 2021). The Office for Environmental Protection highlighted the importance of the GI Framework in its annual report, which was otherwise critical of government progress towards improving the natural environment in England. It notes that the framework has the “potential to be an influential lever in planning decisions” and that “the underpinning evidence, guidance and tools are high quality” (OEP, 2024a; 2024b). The GI Standards were also endorsed strongly by the Secretary of State in the introduction to the third National Adaptation Plan (NAP), as a “consistent way to set out what good green infrastructure provision looks like” and to “help increase the amount of green cover in urban residential areas and other places where it can deliver multifunctional benefits” (Defra, 2024a; NAP3). Furthermore, Natural England is preparing a report on how the GI Framework contributes to adaptation. Proposed reforms to the NPPF announced by the new government in 2024 include direct reference to the Natural England standards on accessible green space, the UGF and Green Flag criteria. They also require the provision of green space for new development to “meet local standards where these exist in local plans” and “where no locally specific standards exist, development proposals should meet national standards relevant to the development” (MHCLG, 2024, para 156). This recognition of the importance of GI standards in key environmental policies is encouraging, and it will be important to maintain and strengthen the continuity of this policy commitment to greener place-making for the long term in future iterations of national planning policy.

The GI Framework is already being applied as the core of a new ‘Nature Towns and Cities programme’ run by Natural England, working with the National Trust (a United Kingdom conservation organization) and The National Lottery Heritage Fund. Offering £15 million for capacity building, this aims to attract further investment and support for accessible green space in at least 100 United Kingdom towns and cities (focusing on areas lacking green space), to improve health and wellbeing and create better connected and more climate-resilient neighbourhoods. It will also establish a UK-wide network enabling practitioners to share best practice.

Of the six Local Authorities interviewed in Phase 2, four explicitly endorsed the overall structure of the draft Core Menu around the five descriptive principles of good GI as a clear, logical and comprehensive framework, and none provided any specific criticisms or objections. Early responses (n = 36 in early 2024) to Natural England’s ongoing evaluation survey of the current GI Framework, which includes the five Headline GI Standards but not yet the full Core Menu, are mainly from Local Authorities (56%) but also include the housing and development industry, landowners, consultancies, landscape architects and charities. Of these respondents, 39% have used the GI Framework and 85% said they were likely to use it in future. Of the 14 local authority respondents who have used the GI Framework, 86% stated that it had helped them to follow the NPPF guidance when considering green infrastructure in local plans and new development. All four of the Local Authority respondents who have adopted or refreshed their local plan since the launch of the GI Framework used it to support development of their strategy. Within the GI Framework, the most useful elements were the GI Principles, GI Standards and GI Mapping Database (ICF Consulting Services Limited and Live Economics Ltd, 2024).

Natural England has provided a training programme to 27 Local Authorities in 2023–4 and further bespoke advice to 10 of these, supported by their Area Teams. The engagement target will increase to 40 local authorities in 2024–5. Natural England also provide free training webinars on their website (Natural England, 2023). Of the survey respondents who have used the GI Framework, 84% felt that this support was very useful (46%) or somewhat useful (38%).

4.3 Tensions and trade-offs

The GI Standards are voluntary, but we found differing views on the balance between the strength of mandatory standards and the need for flexibility to meet local needs and constraints. Some stakeholders felt that mandatory national standards that apply to all authorities would provide a strong steer for minimum delivery and help them to enforce delivery of good quality GI by creating a level playing field for developers in all areas. Stakeholders often asked for stronger weight for the GI Framework in policy, especially by including them in the NPPF and associated guidance. This would help councils to justify their inclusion within their local plan policies and enforce their application.

However, other councils argued that local constraints can make delivery of universal standards extremely challenging. For example, it can be difficult or even impossible to deliver 40% green cover in dense urban areas, especially where there are high housing delivery targets. Local authorities with no space to create new GI had to focus on improving quality and accessibility instead, as well as negotiating with neighbouring authorities to meet local needs. While standards for new development were thought to be more feasible than retrofitting GI in existing areas, sometimes developers deliver off-site contributions where space is constrained. Access standards can also be challenging in rural areas with poor public transport, narrow roads, low car ownership, and lack of connection to the existing footpath network, unless landowners allow creation of new paths across their land. Universal standards that do not reflect the local context have been highlighted by Dang et al. (2020) and Nyvik et al. (2021) as being at risk of poor take up due to a lack of focus on the bespoke planning issues visible at this scale.

With GI provision being very variable across the country, standards that are perceived as out of reach and unachievable can demotivate stakeholders, resulting in inaction (Washbourne and Wansbury, 2023). Also, where current GI provision exceeds standards, there is a perverse risk of a “race to the bottom”. This was evident from our interviews, with one local authority with ample green space considering whether to allocate some of it for development, while another, in contrast, viewed it as a long-term asset and focused on improving its quality and accessibility.

Challenges with fixed minimum standards in conservation have also been exposed by Brann et al. (2024), who highlight that any minimal standard inevitably excludes some aspects of natural assets (such as particular species or habitats) that are worth protecting. They suggest adopting ‘conservation reasonabilism’ as opposed to ‘conservation minimalism’ through a process of free and open discourse to ensure a flexible, practical, and ethical conservation approach (Brann et al., 2024). This endorses the value of the “process standards” within the GI Framework that aim to ensure inclusiveness in the development and application of standards.

The GI Standards therefore aim to balance ambitious top-down national standards with a bottom-up approach in which local areas can adapt standards to their local context and needs. A mixed approach was adopted for the Headline Standards. The Accessible Greenspace Standards and Urban Greening Factor set national benchmark targets, while the Urban Nature Recovery Standard and the Urban Tree Canopy Cover Standard encourage stakeholders to measure their local baseline, and then set local quantitative targets and standards based on the local context, needs and priorities. In addition, all the Headline Standards make a clear distinction between standards for the whole area and those for new developments.

The Core Menu recommends setting both minimum and aspirational targets, allowing local authorities to set their own timescale for progress to meet these targets, and/or allowing them to set their own aspirational targets (see Table 5). Aspirational targets fit the British Standards Institution’s specification-led approach while addressing the risk that as new knowledge becomes available over time, existing targets may no longer represent the optimal solution (Nyvik et al., 2021). If standards are referred to in regulations, it can prove challenging to differ from them, even if improved alternative solutions or evaluative techniques exist (Carter et al., 2024). Aspirational targets enable local authorities and developers to be flexible, able to adopt innovative approaches to meet their needs and reduce the time consumed by frequent updates to the standards.

However, there is a risk that this flexibility could result in lack of ambition and creativity, and failure to collectively meet national climate and nature targets. Even in dense urban areas, fixed standards such as the UGF can help to drive creative responses to enhancing GI, such as use of green roofs and walls, SuDS and street trees. Several key aspects of the GI Standards help to reduce the risk of under-ambition associated with this flexible, voluntary approach. Firstly, the GI Strategy Headline Standard requires Local Authorities to work with all relevant stakeholders to develop the overall strategy for the area, providing an opportunity for stakeholders to make the case for standards that deliver objectives on nature, climate, health and other local goals. This is reinforced by the statutory duty for Local Authorities to consult with relevant stakeholders when formulating Local Plans, and the need to follow best practice and take an evidence-based approach which will withstand public examination. Also, the supporting elements of the GI Framework, including the Process Journey guides, case studies, training material and bespoke support, help to demonstrate what can be achieved even where there are local constraints. The GI Standards can thus be a starting point for conversations about opportunities to do things differently.

4.4 The way forward for the GI standards

To enable successful implementation of the GI Standards in future, it is important to focus on sound governance and build capacity for Local Authorities with limited resources. A key aspect of the GI Framework is the encouragement of cross-sector partnership working and engagement with local communities, in line with the IUCN Global Standard for NbS (IUCN, 2020). This process of debate is critical for supplementing the structured and formulaic approach of quantitative standards, ensuring that GI genuinely meets local needs (Cook et al., 2024; Korkou et al., 2023). There may also be local efficiencies in sharing resources across GI and other statutory processes that require engagement and evidence-gathering.

Even so, the data-gathering and analysis required to assess local GI, develop a strategy, deliver GI enhancements and monitor the outcomes requires considerable resources. Many local authorities currently lack the necessary capacity due to budget constraints. The GI Framework cannot fix a lack of skills, expertise and data, but it may provide a sharper context and purpose to help local authorities fill those gaps, as well as useful supporting tools and guidance.

Digital mapping tools can play a key role in helping local authorities with limited time and budgets apply the GI Standards in practice. Mapping has long been used for identifying opportunities to address urban heating, flood risk management, building shading and biodiversity (Winkelman, 2017) and more recently for systems-based master planning frameworks (Puchol-Salort et al., 2021). Accessible presentation of maps and data can empower non-specialists to make informed suggestions about their priorities (Defra, 2021). With this in mind, the GI Standards are supported by Natural England’s GI Mapping Database which shows existing green space in England, zones that meet each of the Accessible Greenspace size and distance criteria, and a combined map of greenspace deprivation and socio-economic deprivation (Moss, 2023c). Additional layers include statutory site designations, public rights of way, woodland and sports facilities. Feedback from a community group that tested this mapping tool demonstrated that visually mapping GI assets made the concept of standards much more tangible. The maps have already been used at county scale to identify priority areas requiring additional greenspace in Oxfordshire (Crockatt et al., 2024).