- 1Department of Geography, Environment and Geomatics, University of Guelph, Guelph, Canada

- 2College of Social and Applied Human Sciences, Guelph Institute of Development Studies, University of Guelph, Guelph, Canada

- 3Department of Political Science, University of Guelph, Guelph, Canada

In this article, we conduct an analysis of the Pathway to Canada Target 1 biodiversity conservation policy process to determine its level of inclusivity towards Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems. Also known simply as the Pathway, the policy focuses on Target 1 of Canada’s efforts to meet Aichi Target 11 of the Convention on Biological Diversity by 2020. The study aims to showcase the importance and meaningfulness of Indigenous involvement in the policy process. Simply including Indigenous actors does not automatically mean that their knowledge contributions to the policy were considered. Knowing why, when, and how Indigenous Peoples were engaged in the policy process helps us to see the role their presence and contributions played in co-producing policy knowledge for informing the Pathway to Canada Target 1 policy process. This is fundamental in reconciliation and in the improvement of conservation policies. After a review of the history and structure of the Pathway, paying attention to the importance of building relationship with Indigenous Peoples early in the policy process, we use the policy cycle model, outlining five stages of the policy process, to enable our analysis. While we have chosen the policy cycle model as a general framework for analyzing the stages of the policy process, it is a Western model, which falls short in its ability to reflect Indigenous worldviews adequately. Its use reveals, however, the degree of Indigenous engagement in each of the stages, demonstrating that the Pathway to Canada Target 1 did engage Indigenous Peoples at certain stages, in ways potentially reflective of what the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) Calls to Action demand. We conclude with recommendations for more collaborative governance in policymaking that would be more attentive to including Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems at all stages of the policy cycle.

1 Introduction

In recent years, global biodiversity policies have evolved to integrate Indigenous knowledge systems into conservation strategies. For example, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) adopted in 2022 emphasizes a whole-of-society approach to conservation and underscores the importance of including the knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples in science-policy approaches (Global Biodiversity Framework, 2022). This has led more countries, including those with colonial histories and institutions like Canada, to increasingly recognize and address Indigenous Peoples’ needs and contributions to policy-relevant knowledge. With the signing of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and environmental agreements such as the GBF there is increasing recognition by the Canadian government that the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in environmental policy is critical for success. Indeed, UNDRIP asserts the rights of Indigenous Peoples to their lands (e.g., Articles 24–26) and to participate in decision-making effecting their rights (e.g., Articles 18–19). For settler-colonial states1 like Canada (Barker, 2015), whose successive governments have long asserted exclusive jurisdiction over lands and waters, living up to these commitments can be particularly challenging. Increasingly over the past decades and through the hard work of Indigenous Peoples in the court system, as well as lobbying, protests, and media campaigns (Coulthard, 2014; McAdam, 2015; Manuel and Derrickson, 2021), it has become clear that the Crown governments of Canada, federal, provincial, and territorial, have legal responsibilities to work with Indigenous Peoples in ways consistent with signed treaties and the Canadian constitution (Duhamel, 2022). Since 2015, when the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015) drew public attention to the historic and present mistreatment of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, a new reconciliatory relationship between the Crown and Indigenous Peoples has become urgent concern in all areas of Canadian society (MacDonald, 2016).

TRC Call to action #43 calls on the government to ‘adopt and implement’ the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) which Canada had endorsed in 2010 (Duhamel, 2022), while navigating pressure to sign UNDRIP and still objecting over its potential to erode Canada’s asserted jurisdiction. UNDRIP and the TRC Calls to Action are not legally binding instruments, yet they seem to be a moral obligation because they align with Canada’s international claim of being a country of justice without colonial bearings (Henderson and Wakeham, 2009). Finally, in 2016, Canada removed its objector status in the UN General Assembly and in 2021 passed Bill C-15, the implementing legislation for UNDRIP. This new dawn requires the recognition of Indigenous People’s rights to land and governance as well as the obligation to involve Indigenous Peoples in policies affecting them (MacDonald, 2016; Government of Canada, 2018).

UNDRIP Articles 26–29 speak to the importance for the Indigenous Peoples of their traditional lands and the need for states to consult and partner with Indigenous Peoples on domestic policies that impact their rights (UN General Assembly, 2007). Article 25 speaks to the Indigenous Peoples right “to maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationships with their traditionally owned or otherwise occupied and used lands”, and Article 29 speaks to their right to the “conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources” (UN General Assembly, 2007). Biodiversity conservation policies are implicated given that protected areas and other conservation mechanisms have been acting as a means of displacing Indigenous Peoples (Adams and Hutton, 2007; Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018; Stevens, 2014; Binnema and Niemi, 2006; Sandlos, 2008) and disregarding their knowledge systems (Slater, 2019; Kohler and Brondizio, 2017; Sandlos, 2014; Youdelis, 2016; Zurba et al., 2019) despite mounting evidence that the knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples are vital for biodiversity conservation success (Berkes et al., 2000; Brondizio et al., 2021; Pierotti and Wildcat, 2000). The colonial history of conservation policy and other colonial violence, including the breach of treaties, land disputes (Regan, 2010; Blackburn, 2019; Coon Come, 2015), and the residential school system (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015) have given rise to deep mistrust amongst Indigenous communities towards state policies. With the signing of UNDRIP and its implementing legislation, the federal government sent signals that protected area expansion in Canada needs to be done with Indigenous Peoples, rather than for them, especially in federal government jurisdictions.

The growing public attention, globally and locally, to both environmental issues and Indigenous rights shifted political views on Indigenous involvement in biodiversity conservation to an extent that these dual issues became part of ongoing political debates. International debates about the rights of Indigenous People stimulated changes in the public policy towards land and resource rights, and in Canada, for example, the Berger inquiry into the Mackenzie Delta oil pipeline, and the Inuvialuit Final Agreement in 1984 contributed to changes in national park policy with regard to Indigenous rights (Adams and Hutton, 2007). The growing public attention contributed to giving an important place to environmental issues in Canada’s political landscape (Beazley and Olive, 2021). In 2015, a new federal government under the Liberal Party was elected with a renewed focus on reconciliation and biodiversity conservation. Evidence of this commitment can be found in the mandate letters for the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Canada in 2015, where the expansion of protected areas and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples both feature prominently (Prime Minister of Canada, 2015). A challenge for Canada then, given the political support for expanded conservation measures, was to put in place processes that appropriately involve Indigenous Peoples in conservation policymaking, while ensuring the public expectation of environmental protection is met.

A response to this challenge was the development of the Pathway to Canada Target 1 policy to meet the Aichi Targets (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2016), established by the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 2010 (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2010). The Pathway to Canada Target 1 policy process was enacted in 2017 to help Canada meet its Aichi Targets, which committed Canada to protecting 17% of its lands and 10% of its coastal and marine area by 2020 while outlining a “new approach to conservation in Canada”, advancing a more collaborative approach that recognizes “the integral role of Indigenous Peoples as leaders in conservation, and respects the rights, responsibilities, and priorities of First Nations, Inuit and Metis Peoples” (National Advisory Panel, 2018). While the Pathway began as a way of meeting international biodiversity targets, it gradually grew into a process with potential for promoting reconciliation within the conservation sector, as well as a guide for organizations seeking to implement the TRC’s Calls to Action and UNDRIP’s call to recognize Indigenous Peoples’ rights and involve them in policies. This policy process was completed in 2022, claiming to be an inclusive process as highlighted by the National Advisory Panel (NAP) in its 2018 report, and a possible model for other processes (Elder Larry McDermott, interview 2022).

Now that Canada has passed Bill C-15 and is working towards meeting its international obligations under the Global Biodiversity Framework, it needs models on how to advance policy in a more collaborative and inclusive manner (Scott, 2015). Doing so could contribute to rebuilding the trust that has been broken through years of conservation policy which has alienated and displaced Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems. Article 27 of UNDRIP states (UN General Assembly, 2007):

“States shall establish and implement, in conjunction with indigenous peoples concerned, a fair, independent, impartial, open and transparent process, giving due recognition to indigenous peoples’ laws, traditions, customs and land tenure systems, to recognize and adjudicate the rights of indigenous peoples pertaining to their lands, territories and resources, including those which were traditionally owned or otherwise occupied or used. Indigenous peoples shall have the right to participate in this process.”

The question we seek to answer is, to what extent were Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems included in the Pathway policy process? Answering this question would help understand the degree to which the Pathway process embodies the principles of UNDRIP and what could be improved for future federal policy processes to deliver on international biodiversity obligations. The purpose is to investigate the Pathway as a model for inclusive policy reforms in Canada and call the attention of policymakers to the successes and shortcomings of the process so that improvements can be made as Canada moves into the implementation of the Global Biodiversity Framework.

1.1 History of the pathway to Canada target 1

The Pathway made its way into the Canadian policy landscape as a tool for biodiversity conservation reform as well as a tool for reconciliation. It embodied part of the struggle by Indigenous Peoples and their communities for their rights to land and conservation governance and has been used by some Indigenous Peoples as a way to voice grievances on their marginalization in biodiversity conservation policy in Canada. Prior to the Pathway, conservation policies in Canada had mostly neglected Indigenous knowledge systems and practices (Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, 2021; Kohler and Brondizio, 2017; Moola and Roth, 2018; Youdelis, 2016; Government of Canada, 2017). Since Indigenous worldviews previously have been neglected and thus effectively undermined (Loring and Moola, 2020), the conservation community has found it challenging to move towards a model of knowledge co-production (Miller and Wyborn, 2020) that draws on multiple knowledge systems for policymaking (Brosius, 2004), especially in Canada (Zurba et al., 2019).

After the election in 2015, the new federal government was open to collaborate with Indigenous Peoples for more inclusive policies, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made reconciliation and a ‘renewed nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous Peoples’ a priority in his mandate letters to Ministers (Prime Minister of Canada, 2015). In response to this mandate letter, policymakers within the Parks Canada Agency started thinking about how to advance their mandate to improve relations with Indigenous Peoples. According to some executives of Parks Canada and the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), and members of other organizations that were key actors of the Pathway, the Pathway initiative was meant to help Canada catch up with the long delay in meeting international obligations on biodiversity conservation.

The Pathway was a process initiated in 2017 by the federal government, in collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, to address the domestic implementation of the Aichi Targets of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). However, according to Nadine Spence of Parks Canada, who co-chaired the Pathway process, preliminary discussions started with Indigenous experts as early as 2016. Ms. Spence (Nuh-chal-nut), emphasizing that her role in the Pathway was as an employee of Parks Canada, worked to ensure that relations with Indigenous leaders started well before the public launch of the Pathway. Unlike other initiatives, including the Canadian implementation of the Paris Climate Agreement (Jordaan et al., 2019), the Pathway was not only a Federal, Provincial, Territorial (FPT) initiative (Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, 2021). It was also shaped by Indigenous leaders from the outset, leading to the establishment of the Indigenous Circle of Experts (ICE) composed of Indigenous experts on conservation issues, law, governance, and Indigenous knowledge. Initially proposed as a working group within the National Advisory Panel (NAP), composed of conservation and industry leaders, ICE was negotiated to be a committee reporting directly to the Minister. Co-chaired by Eli Enns, of Tla-oh-qui’aht First Nation, and Danika Littlechild, Ermeskine Cree First Nation, ICE engaged Indigenous Peoples and organizations across Canada, holding four regional meetings and establishing itself as a pillar of the Pathway process. The cooperation established in the early phase of the Pathway, which included Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems in Canada’s conservation policy, was effective and resulted in widespread acceptance of the ICE report. The goodwill to implement its recommendations and those of other committees has influenced Canada’s response to the post-2020 biodiversity targets adopted as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) in Montreal in 2022.

1.2 The pathway to Canada target 1 and the policy process in Canada

The Pathway can be understood as a policy process in that it fits the general definition of a set of laws, regulations, and initiatives implemented by government bodies to address public issues (Hessing et al., 2005; Hill, 2013; Jann and Wegrich, 2017). In a democratic country like Canada, policies are expected to be motivated by the desires of the general public through the votes of a majority. The democratic process is, however, also expected to consider the voices of every group in the country, including Indigenous Peoples (Howlett, 2009). This is becoming more important in an era where reconciliation is gaining ground in public affairs. Policy actors of the Pathway to Canada Target one took a giant step to ensure that reconciliation played a key role in the process by enshrining it as the first principle of the Pathway policy document (Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership, 2021). A systematic analysis of the Pathway process will assess to what extent the Pathway lived up to its reconciliatory intent by engaging Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems at all stages of the process.

1.3 The policy cycle model

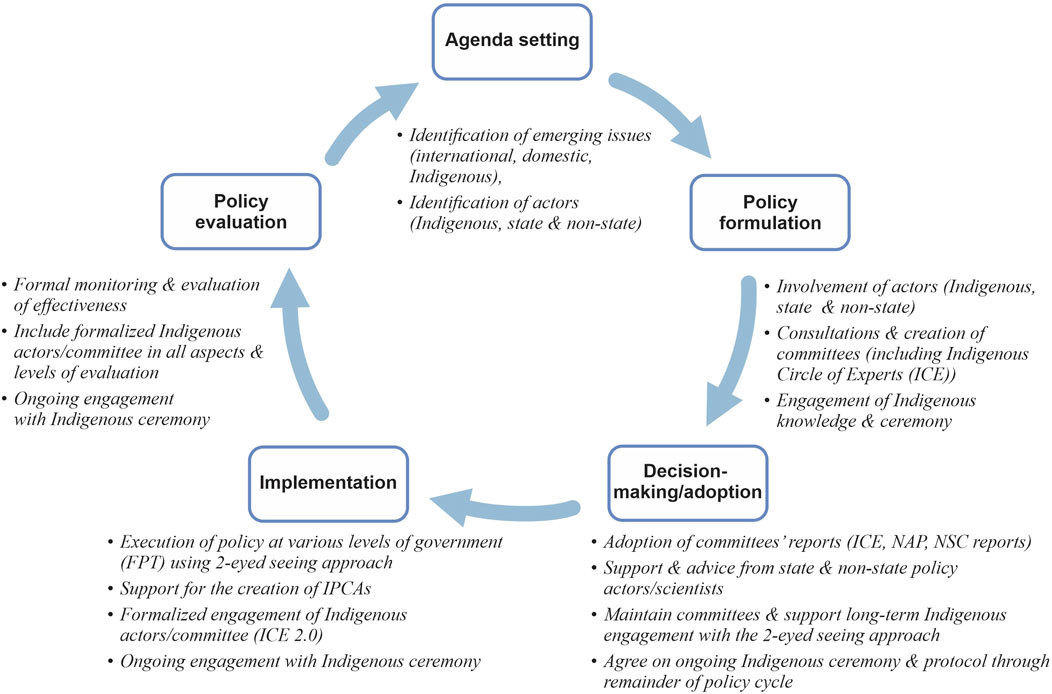

The policy cycle model is a general framework for analyzing the stages of the policy process, commonly presented in five stages (Jann and Wegrich, 2017; Sabatier, 1991), including agenda setting, policy formulation, decision-making/adoption, implementation, and evaluation (Hessing et al., 2005; Howlett, 2009). In our analysis, we use the five-stage policy cycle model as a tool to examine the Pathway policy process and its level of involvement of Indigenous Peoples at each stage. While not necessarily the ideal model (Ayres, 2021) the policy cycle model gives an overview of the policy process, enabling us to pay attention to inclusivity at each stage (Hessing et al., 2005; Howlett et al., 2009; Jann and Wegrich, 2017). We use this model as a general framework to assess the existing policies and suggest an extended model that contributes to integrate Western and Indigenous approaches (Figure 2) and offers more opportunities for including Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems in all the stages of the policy cycle. Knowing “how well or how poorly the policy process operated” (Ascher, 1986: 370), with the inclusion of Indigenous actors, is helpful for other policy processes.

The agenda-setting stage is the stage where a policy issue is identified, gains government attention, and is recognized by policymakers, who then ensure that it is placed on the state’s policy agenda (Birkland, 2007; Hessing et al., 2005; Jann and Wegrich, 2017; Kingdon, 1995). Jann and Wegrich (2017) identify four patterns that explain different ways agendas get set. In the outside-initiation pattern, the government is pressured by social actors to act on an issue. In the inside-initiation pattern, the issue on the agenda comes from government actors, with possible interference from interest groups, but not as influential as in the previous pattern. In the mobilization pattern, the government does not get support from non-state actors initially, and in the consolidation pattern, the government relies on a popular issue to initiate a policy.

The policy formulation stage refers to the stage where solutions are sought by state and non-state actors and proposed to the government for decision. At the decision-making stage, the government decides on the solutions to be implemented. In the implementation stage, administrators take action to ensure that the policy decisions are materialized. The policy evaluation stage is put in place to assess the effectiveness of the policy. This final stage helps guide future policies by informing policymakers about policy successes, failures, or shortcomings.

2 Materials and methods

The idea for the project reported in this article came from the Indigenous leadership of the Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership (CRP), a nation-wide partnership founded by several members of the ICE committee and their academic allies. The purpose was to explore the achievements of the Pathway process in its efforts at reconciliation. None of the authors identify as Indigenous from North America. The first author is from Cameroon and has an interest in Canadian public policy, biodiversity conservation, and reconciliation. The second author is a political ecologist working at the intersection of biodiversity conservation and Indigenous environmental knowledge and currently serves as the Principal Investigator on the Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership. The third author is a political scientist with extensive experience collaborating with Indigenous partners on issues related to Indigenous rights, reconciliation, and policy.

Research consisted of interviews with key actors in the Pathway process, participant observation, review of academic and grey literature, and use of secondary data on UNDRIP, TRC, biodiversity conservation in Canada, the Aichi Targets, and the Pathway to Canada Target 1. The grey literature included government reports and publications as well as Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) publications on biodiversity conservation, public policies, and Indigenous engagement. The literature review helped us to identify major areas of concern regarding Indigenous involvement in conservation policies and practices in Canada and revealed that despite the growing discussions about the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems in conservation practice (McGregor, 2021), there was considerably less guidance on the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in environmental policy formulation (Zurba et al., 2019). These insights were combined with participation in conferences, workshops, seminars, symposiums, and conservation actors’ gatherings organized by the CRP, enabling access to key conservation actors and assisted in the relationship building process.

To explore our question about Indigenous inclusion in the Pathway process, we conducted what Pisarska (2019) and Harvey (2011) call elite interviews, with focus on the experiences of those centrally involved in the process, due to their individual impact and insider knowledge. The interviewees, both Indigenous and settler, played crucial roles in the Pathway to Canada Target 1 policy process. They were recruited from committees of the Pathway policy process, namely, the Indigenous Circle of Experts (ICE), the National Advisory Panel (NAP), and the National Steering Committee (NSC). We made efforts to have a balance of Indigenous and non-Indigenous interviewees, but it was not possible because of disproportionately small number of Indigenous actors on the committees, with the exception of ICE. We were able to interview one co-chair of the ICE, four Indigenous ICE core members, and a few other Indigenous experts and leaders who played important roles in the Pathway process directly and indirectly. We interviewed four members of the NAP, as well as the co-chair. We were able to interview a total of 26 key policy actors of the Pathway policy process. At that point the responses from new participants were no longer bringing in additional information. It is worth noting that the Indigenous leaders and experts involved in the Pathway were not representing their communities but were invited to the Pathway for their experience relevant to Indigenous-led conservation. They sought the inclusion of community voices through the regional gatherings with Indigenous communities across Canada (Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018).

Before heading to the field for interviews, we had approval from the Research Ethics Board of the University of Guelph, Canada and followed the procedure for oral or written consent. Semi-structured interviews were conducted for deep conversation with participants (Laws et al., 2013; Longhurst, 2010) and were helpful in gaining an understanding of the Pathway process beyond the reports and other documents. We used an interview guide with open-ended questions, prepared and shared with the participants before the interviews, alongside an informed consent form. Some interviews were face to face while others happened on digital platforms due to covid pandemic restrictions. We began the conversations by discussing the informed consent form. Some participants signed the informed consent form, while others provided oral consent. Participants were asked if they wanted to remain anonymous or have their names used for direct quotations. All named participants quoted in this article agreed to be cited directly. Those who could not be reached for the approval of their quotes have their opinions either cited anonymously or paraphrased. The interviews ranged between 45 and 90 min long. A few cases went beyond 90 min as some participants decided to engage in deeper conversations on conservation policies and reconciliation.

The primary data helped to examine the engagement and the role of Indigenous actors at each stage of the Pathway policy cycle. Our approach to the collected data is interpretive and reflexive (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2017). All interviews were transcribed and subjected to qualitative text analysis coding for different themes, including the connection between the Pathway, UNDRIP and the TRC Calls to Action, inclusion and engagement of Indigenous Peoples, discussions about reconciliation, and the Pathway as a tool for reconciliation. Coding of the interviews was conducted with the use of NVivo, a qualitative software. All responses to a certain theme were grouped together making it possible to identify general tendencies in the responses and themes where respondents disagreed. From our analysis of the data, we could identify the stages of the policy cycle model where Indigenous actors were most involved in the Pathway, and those stages where involvement was minimal, as well as the quality of engagement.

3 Results and analysis: interrogating the Pathway and Indigenous engagement through the policy cycle model

3.1 The agenda-setting stage of the pathway

Both international and domestic factors played important roles in the agenda-setting stage of the Pathway. While the policy emanated from the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 2010, the decision to inscribe it on Canada’s environmental policy agenda took place in 2015 when the incoming federal government had made a political decision to collaborate with Indigenous People in several policy areas, as expressed in Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s 2015 mandate letters to several ministers, including the Minister of ECCC who was the overseer of the Pathway process. This administrative instrument created an official platform for collaboration and engagement with Indigenous Peoples in the Pathway process. Indigenous engagement in the Pathway can be seen as an attempt to seek solutions to the “wicked” problem of biodiversity conservation, arising from a situation of diverse values and objectives (Zurba et al., 2019; Rittel and Webber, 1973), which got more complex because of the need to consider Indigenous rights to land and resource governance. Although the Aichi Target 18 also emphasized the importance of Indigenous participation in all conservation initiatives (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2010; Zurba et al., 2019), the Crown government saw it as an opportunity for relationship building towards reconciliation as stipulated in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action.

The combination of these factors made the agenda-setting stage of the Pathway policy process quickly change from an outside-initiation pattern, from the CBD, to a consolidation plus an inside-initiation pattern. Apart from being an important issue for government of the day, there was also pressure from environmental organizations. This change in the Pathway policy reflected attempts to better include Indigenous-led conservation. According to Nadine Spence of Parks Canada and Scott Duguid (interview, 2022) who represented the government of Alberta on the Initial Pathway committee, the agenda was drafted with an eye to how Indigenous engagement in the process could be best accomplished. Although Indigenous Peoples were not explicitly involved at this stage of the policy process, this early thinking about Indigenous involvement enabled rapid uptake at the next stage of the process.

3.2 The policy formulation and decision-making stages of the Pathway

The policy formulation and decision-making stages have been combined in our analysis because they frequently overlapped in the context of the Pathway, making it hard to distinguish them, an overlap also pointed out by Hupe and Hill (2006). In the policy formulation and decision-making stages, the federal government created a structure with committees and working groups that evolved over time to meet the needs of the policy process. In these two stages, Indigenous Peoples were invited to join the policy process mostly through the creation of the ICE, advocated for by the Indigenous leaders and experts that first were contacted by the federal government. Indigenous actors were also included as members of the other committees, NAP and NSC, but their numbers and engagement in the policy making process were limited. The NSC had representatives from the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and the Metis National Council but only the AFN representative self-identified as Indigenous. Membership on these committees, and especially the ICE, meant that Indigenous actors could bring their knowledge systems and worldviews to the table and contribute to the co-creation of knowledge for policy development (Coggan et al., 2021; National Steering Committee, 2022). The ICE committee was composed of 20 members, with two co-chairs and 11 core members who are Indigenous leaders and experts and additional members who represented the Federal, Provincial, and Territorial (FPT) governments (Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership, 2021; Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018).

Regional gatherings for Indigenous community consultations were organized across Canada (Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018; National Steering Committee, 2022). These gatherings were an effort to hear the voices of Indigenous communities from across Canada and engage them in the policy process. The governments of Nunavut and Quebec were not part of the Pathway, and Indigenous communities and governments from those jurisdictions were not well represented in the regional consultations, although some traveled to ICE gatherings. According to a key state actor of the Pathway process, there was a sense that some absentee communities did not trust the process. Another state participant explained that others could not participate because of the distance to the meeting locations and associated expenses since the federal funds were not sufficient to support participants from all Indigenous communities. While the budget and scope of the ICE did not allow for broad Indigenous participation in the larger Pathway process, ICE was able to engage a remarkable breadth of Indigenous leadership. At the end of its mandate in 2018, ICE submitted a landmark report titled We Rise Together: Achieving Pathway to Canada Target one through the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the spirit and practice of reconciliation. This report was instrumental in the rest of the Pathway process and continues to be a reference for Indigenous-led conservation policy, research, and practice (Zurba et al., 2019).

Every actor in the Pathway process with whom we spoke appreciated the work done by Indigenous experts, knowledge holders, and leaders on ICE. They all agreed that the presence of ICE was a critical component of the Pathway’s success. With the regional gatherings, ICE was able to generate goodwill and insight into the perspectives of Indigenous Peoples across Canada and respectfully include Indigenous knowledge systems and Indigenous worldviews in the ICE report, thus rebuilding trust in national policymaking. The ICE report, with wide consultation and being Indigenous-led, was a thorough expression of Indigenous knowledge systems and worldviews. The NAP and NSC reports also supported the Indigenous views of the ICE report. The Indigenous participants interviewed all agreed that their views were taken into consideration during the policy formulation stage, which suggests that ICE, NAP, and NSC were all able to engage Indigenous Peoples and knowledge systems in their recommendations.

A noteworthy initiative introduced at the decision-making stage was the consideration given to Indigenous ceremonies. The Pathway process opened and closed with a pipe ceremony, led by Elders Reg Crowshoe (Piikani) and Larry McDermott (Shabot Obaadjiwan). This was highly appreciated by Indigenous Peoples in all seminars and conferences we spoke with. According to most participants, the inclusion of these ceremonies, long absent from official Canadian protocol, was significant to them because it was a sign that the relationship-building process was headed in the right direction. They all agreed that the early stages of the Pathway made them feel a sense of belonging in the policy initiative and influenced them to pledge their support for the policy. It was decided to recognize the practice of traditional medicine bundles (Pauketat, 2012), common to many Indigenous cultures, by creating a sacred bundle containing meaningful objects and herbs representing the Pathway process and gifting it to the Minister. The traditional medicine bundle was gifted to Minister McKenna at the conclusion of the Pathway. According to Indigenous leaders and experts, the traditional medicine bundle was expected to be passed on to each ECCC Minister, to remind them of their responsibilities towards the Indigenous Peoples and keep the stories of the Pathway alive. During the Pathway, Indigenous Elders and knowledge holders would offer opening and closings to each meeting and gathering as a way of upholding Indigenous protocol. Non-Indigenous participants were also deeply touched by the ceremonies they took part in. Discussion on the importance of the ceremonies is prominent in the NSC report (National Steering Committee, 2022, p.14), and participants have widely spoken to the personal transformation experienced in ceremonies. However, the impact of the ceremonies was limited in the Pathway process, since the foundation of the relationship that required ongoing maintenance through dialogue and co-production of policy knowledge began to deteriorate when Canada moved into the next stage of the policy process.

3.3 The implementation stage of the Pathway

Considering the complex nature of the Pathway, the implementation stage appears to be the most critical one. It is where the materialization of the Pathway strategies through effective ground action was expected to show ‘good faith’ on the part of the Crown government. By ‘good faith’, we mean action related to the principles of good laws (Baxter, 1980; Kolb, 2006; Reinhold, 2013). As Kolb (2006) suggests, it is a principle protecting legitimate expectations. This was what gave hope to most Indigenous participants on the Pathway and Indigenous Peoples more broadly. To a certain extent, some good fruits were harvested at this stage. The federal government rapidly announced a Nature Fund of over CAD 166 million of which was to be invested in the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) (Government of Canada, 2021). IPCAs were a policy recommendation from ICE and are being established in collaboration with Indigenous experts, leaders, and communities, and are intended to be Indigenous-led (Thaidene Nene, 2021; Thaidene Nene, 2024; Townsend and Roth, 2023; Zurba et al., 2019).

Apart from the IPCAs that were established by Nature Fund investments, the involvement of Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems in the establishment of protected areas faced several challenges as the announcements regarding the Crown government’s support for Indigenous-led conservation did not match the reality on the ground (Youdelis et al., 2021). While the Nature Fund represented “the largest single investment in conservation in the history of Canada” (Jane Sumner, Co-chair of NAP, interview 2022) there was insufficient funding to support local community projects and involvement by Indigenous Peoples in the Pathway process. In addition to limited funds, Indigenous communities and organizations could not access the available funds easily because of the daunting bureaucratic procedures at the various levels of government (Janet Sumner, interview 2022). According to some participants, the Nature fund was also biased towards projects that were capable of quickly contributing to Canada’s targets, leaving smaller community projects without provincial government support, unfunded. This meant that implementation was mostly in the hands of Crown governments, without Indigenous contributions, thus making many question the Crown government’s commitment to reconciliation through the Pathway. Apart from a few IPCAs which the state recognized as Indigenous-led, most other protected areas projects proceeded as before, thus effectively undermining the involvement of Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems (Townsend and Roth, 2023; Youdelis et al., 2021). Nevertheless, with the announcement of more funds to support several Indigenous conservation initiatives such as the guardians program (Government of Canada, 2023) and other Indigenous-led conservation programs including the Aboriginal fund for terrestrial and aquatic species at risk (Government of Canada, 2022) and an Indigenous-led area-based conservation program (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022; Tamufor and Roth, 2022), there is hope for improvement. With increased federal funding for IPCAs, there is growing concern that the federal government has appropriated IPCAs as their program, stirring up historical mistrust and threatening the relationship gains made through the Pathway (Townsend and Roth, 2023). Federal funding seemed to have altered the path of the policy process through what Sabatier and Mazmanian (1980) call “conditions to the disbursement of funds”.

Other government actions also exacerbated the increasing tension between the Crown government and Indigenous conservation leaders, especially the decision to take Parks Canada out of the management of the Pathway process and hand implementation over to ECCC. Nearly all public administrators who were involved in the initial stages of the policy process were replaced. The final reports were handed over in ceremonies on 30 March 2018, and on April 1st, the ICE committee found out that ECCC, instead of Parks Canada, would be the implementing agency. Eli Enns (Tla-o-qui-aht), co-chair of ICE, referred to this abrupt change that silently sidelined their committee and most Indigenous actors as “the April Fools day joke”. Such a change suggested to the Indigenous participants in the Pathway, intentionally or not, that they were not partners, but rather instruments in the Pathway, dampening their enthusiasm and sowing seeds of mistrust, especially after the government of Canada discontinued ICE. Curtis Scurr (Mohawk) (interview, 2022), member of ICE and the AFN representative on the NSC, expressed his disappointment on discontinuing ICE by saying, “We built a really wonderful machine and sent the mechanic home.” When questions later surfaced on the NSC about the functioning of the “machine”, i.e., the Indigenous knowledge, worldview and perspectives, Mr. Scurr was left having to explain that he could not answer them alone because the experts had been dismissed without any preparation for developing an ICE 2.0.

From the beginning of the implementation stage, when the new team at ECCC was appointed towards the end of 2018, the consideration given to Indigenous ceremony that had been introduced by the previous managing team led by Parks Canada, suddenly lost its place. The new state authorities appointed to continue the policy process also neglected the pipe ceremony that had been revived by the previous environmental policymakers as a way of building relationships and supporting co-production of knowledge for policy. According to protocol, the ceremony should be carried out annually, but ECCC did not prioritize this responsibility. The ceremony was a way of building and maintaining relationships between the Crown and Indigenous Peoples, understood as one aspect of fulfilling UNDRIPs promise, and its neglect led to concern on the part of Indigenous leaders involved in the ICE. When this relationship-building dwindled, tension started building up. The traditional medicine bundle that was supposed to be transferred to the new team at ECCC had been misplaced, exacerbating the growing tension. Indigenous interviewees expressed that this situation contributed to re-surfacing of old feelings of colonialism and cultural genocide. Some Indigenous experts and state actors on the Pathway asserted that the momentum to carry things forward slowed down because the administrators of the Pathway policy found it hard to detach themselves from the colonial system that undermined Indigenous expertise. This led to the feeling of betrayed trust. The decision-making style where the government makes decisions through a top-down approach (Young et al., 2014), gradually returned and strained the relationship that was on a good path to reconciliation and Indigenous-led conservation. Although the traditional medicine bundle was later found, its loss had already done serious damage to the relationship built at the earlier stages of the Pathway process.

3.4 The policy evaluation stage of the Pathway

The policy evaluation is perhaps the most contentious stage of the Pathway process. The exclusion of almost all Indigenous actors involved in the Pathway in any form of evaluation was glaring and caused many, especially Indigenous experts and allies we interviewed in 2022 and 2023, to question the good faith of the Crown government. It seriously undermined reciprocity and trust in collaborative policymaking. Only members of the NSC were able to have their voices heard in terms of evaluation, whereas members of ICE and of NAP were sidelined, and there were only two Indigenous representatives on the NSC. Mr. Curtis Scurr suggested that more Indigenous representatives from the three National Indigenous Organizations (NIO) would have been helpful in a process that seeks to address social justice and equity.

The request for an ICE 2.0 by many actors that were involved in the Pathway is an indication that things did not go well. They expected to have the opportunity to address their concerns so that future policies could be improved. Since there is no platform to address such concerns, gatherings organized by the Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership (CRP) project often served as opportunities to express some disappointments (Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership, 2021). The neglect of any follow up process to hear the reflections and concerns of ICE members, risks replicating lessons of the past by marginalizing voices and experiences of participants by centralizing control of the policymaking process back into the state apparatus (Scott, 1998).

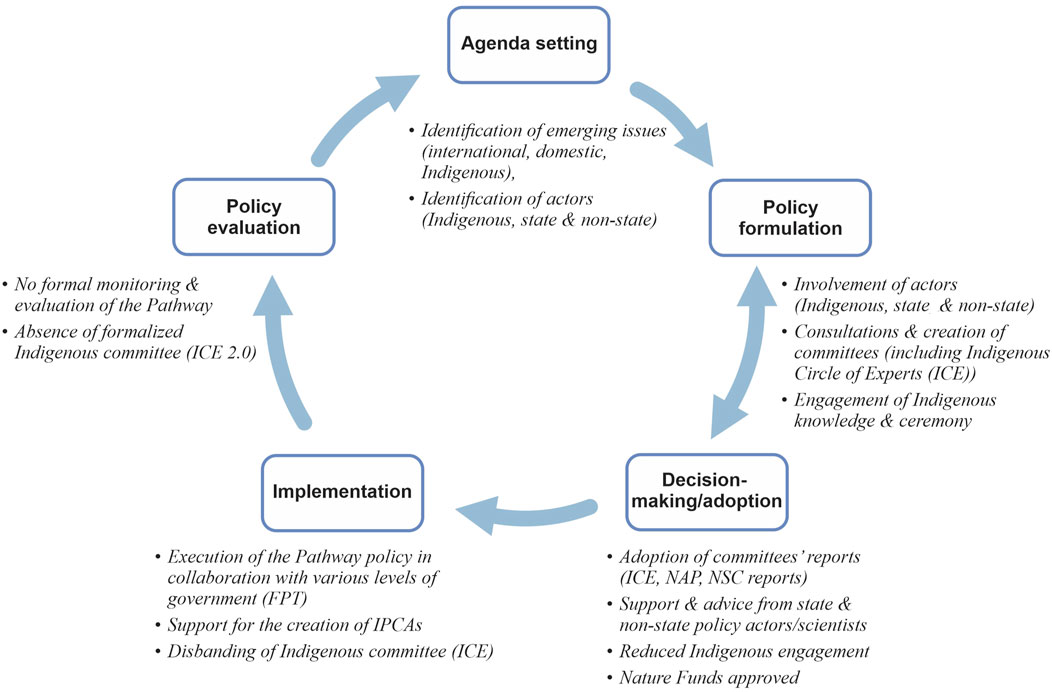

Overall, the Pathway took off well by trying to engage all major actors who have impact on conservation or may be impacted by conservation in Canada. However, after 2018, when the major committees had submitted reports of their findings, doors were shut and the state regained more centralized control. ICE 2.0 was never formed and Indigenous Peoples were left on the outside looking in. The engagement of Indigenous Peoples could be seen in the establishment and celebration of IPCAs, for example, the Thaidene Nene in the Northwest territories (Thaidene Nene, 2021; Thaidene Nene, 2024) and the Edéhezíe Protected Area (Zurba et al., 2019), but slowly disappeared in the national policy arena as the state changed the leading policy actors. The disengagement of Indigenous Peoples became obvious in the implementation stage, and they literally became invisible during the evaluation stage (Figure 1). This departure from the collaboration that seemed to be working well, brought stress to the Pathway policy process and seemed to exacerbate the mistrust in state efforts in co-producing knowledge for policy (Beck, 2011; Miller and Wyborn, 2020; Watson, 2005; Wesselink et al., 2013; Young et al., 2014).

In Figure 1, we have summarized the ways in which efforts were made by the state to include Indigenous Peoples, their worldviews, knowledge systems, and protocols in the Pathway to Canada Target one policy process. Figure 1 also shows the failure to meaningfully include and engage Indigenous actors in the implementation and evaluation stages, explaining why Indigenous resentment resurfaced in the Pathway process that started well. Trust was breached to a large extent at crucial stages, especially with the disbanding of ICE. This experience demonstrates that the presence of Indigenous Peoples at the table is not sufficient, and that meaningful inclusion requires the creation of a space where ceremony can play a role and exchange of knowledge is welcome.

4 Learning from Pathway to Canada target 1 – trust as a major ingredient in reciprocity

Several lessons can be learned from our examination of the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems in the Pathway process as a means to foster collaboration and reconciliation. Using the policy cycle model to investigate the Pathway process highlights that, although there were initial successes from involving Indigenous Peoples, still much needs to be done to achieve reconciliation. In the whole policy process, Indigenous participation was visible only at the agenda setting and policy formulation stages. At the implementation stage, Indigenous involvement was limited to establishment of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas, while their input was absent during policy development at the national scale. The implementation stage was marked by a breach of trust by shifting responsibility for implementation from Parks Canada to ECCC. The evaluation stage was even more questionable. Here, the ICE and NAP committees which contained most Indigenous participants, were discontinued. As expressed through interviews with several previous ICE members, this was causing the build-up of resentment and destroying the elements of trust achieved through relationship building in the early days of the Pathway. The growing resentment and trust issues may be seriously jeopardizing reconciliation efforts at a time when Canada is organizing efforts to meet its post-2020 targets. The Crown government needs to strengthen its efforts in regaining the trust of Indigenous actors and their communities, to ensure that conservation policies are sustainable (Bouckaert and Van de Walle, 2001; OECD, n. d; Young et al., 2014). Lack of trust in policy and administration increases divides between societal actors (Cooper et al., 2008; OECD, n. d.) and impairs the routes to reconciliation.

As Canada moves to implement the Global Biodiversity Framework, Indigenous Peoples need to be engaged more than ever before (Jiang et al., 2024; Zurba, 2014), given their long-standing experience in sustainable conservation practices (Loring and Moola, 2020). The early stages of the Pathway to Canada Target 1 have proven that achieving this is possible but difficult conversations in a ‘brave space’2 will be necessary. Having these conversations will require truth and honesty, and the intention to gain reciprocal trust is essential (United Nations Development Program, 2021), especially in Canada where trust is said to be a growing problem in the government (Norquay, 2022). According to Baier (1986), in Bouckaert and Van de Walle, 2001: 4), “trust involves the belief that others will, so far as they can, look after our interests, that they will not take advantage or harm us. Therefore, trust involves personal vulnerability caused by uncertainty about the future behaviour of others, we cannot be sure, but we believe that they will be benign, or at least not malign, and act accordingly in a way which may possibly put us at risk.” This definition ties with the context of reconciliation and speaks to the growing resentment from some Pathway actors and Indigenous communities regarding the trust they bestowed on the government at different levels, and which was not reciprocated. Eli Enns stated that during the early stages of the Pathway “each time we named the moose in the room, and there was an opportunity for it to fall apart, the crown government responded appropriately, and trust grew”. “Until April Fools Day”, he added, in the old colonial fashion, the trust given to the federal government was betrayed before the end of the Pathway project. The lack of trust was discussed by several Indigenous actors we had conversations with, including Marilyn Baptiste (interview, 2023), former chief of the Xeni Gwet’in First Nation community in British Columbia and a core member of the ICE committee, who said that trust was a concern right from the beginning, but they hoped to get a “pleasant surprise” from state authorities. Despite the disappointments, the federal policymakers were commended for their early efforts in trusting the capacities of Indigenous actors. The concern that remained was how the issue of trust played out throughout the Pathway policy process. This concern seems to be opening old wounds that had begun to heal through the ongoing reconciliation process.

At every stage of the policy cycle, collaboration and co-production of knowledge for policy require an element of trust. According to the OECD (n.d.) public trust fosters social cohesion, and “public trust leads to greater compliance with a wide range of policies [.]. It nurtures public participation, strengthens social cohesion, and builds institutional legitimacy.” The Institute of Public Administration of Canada (IPAC) has prioritized trust as a major theme in its annual conferences and leadership workshops since speakers at the IPAC 75th annual conference in Quebec City in 2018 raised concerns about the trust expected from government officials. This instills hope that reciprocity within the policy structure aimed at co-producing knowledge for policy across all areas of society can be achieved. Indigenous actors involved in the Pathway process had similar expectations that their participation in the pathway process was a reciprocal relationship where trust could be built but they ended up disappointed when senior government officials failed to adequately engage Indigenous actors at crucial stages of the Pathway such as the implementation and evaluation stages. This exclusion was problematic because it did not align with the principles of inclusive engagement stated in the Pathway documents.

Many actors who participated in the early stages of the Pathway process and were involved in the research reported in this article suggested that trust deteriorated when the federal government decided in around mid-2018 to replace nearly all public administrators who were involved in the initial stages of the policy process. A new Minister of Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) was appointed, with a slightly different mandate from that of their predecessor. The new administration did not support the continuity in public administration that would have limited the frustrations of Indigenous Peoples, especially those participating in the Pathway policy process. The former seemed to have undermined, knowingly or unknowingly, a fundamental concept of public policy and administration; that “administration is continuous”, and this has affected the perceived good intent of the government till date. When asked about the implications for their participation in the post-2020 targets, the majority of the Indigenous participants in this research expressed skepticism about the importance of their engagement.

5 Discussion and policy recommendations

The analysis of the Pathway process reveals the limited and inconsistent involvement of Indigenous Peoples, particularly during implementation and evaluation stages. This exclusion indicates a deeper issue within policy frameworks, resulting in a breach of trust and the revival of historical tensions between Indigenous communities and the Crown government. Early promises of collaboration were undermined by later actions, causing skepticism toward future biodiversity conservation policy, including the 2030 targets. Trust is essential for knowledge co-production and reconciliation. The Pathway experience shows that excluding Indigenous voices undermines these efforts. Rebuilding this trust is crucial, as public trust fosters greater policy compliance and strengthens social cohesion (OECD, n. d.).

Moving forward, our research suggests that a two-eyed seeing approach can be highly beneficial (Bartlett et al., 2012) that genuinely integrates Indigenous and Western knowledge systems. Continuous engagement at every stage is key to building trust and creating effective conservation policies, highlighting the need for structural changes that promote transparency, reciprocity, and cultural respect. Our findings suggest that these can be key elements in achieving reconciliation and sustainable conservation policies and practices (Smith and Sterritt, 2010; Zurba, 2014). The following recommendations emerge once we begin to understand and consider trust as a key element in the state’s interactions with Indigenous Peoples.

5.1 Conservation policies should have a well-defined framework, actors, and stakeholders from the beginning

Having a well-defined policy framework which considers the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples, from the beginning to the end, should be established earlier in the policy process. Indigenous, state, and non-state3 actors and stakeholders should be identified and assigned to each stage in a balanced manner. Indigenous Peoples involved in co-production of knowledge for policy should have their voice heard in proposed changes to policy, such as shift in the administrative responsibility. Involvement in evaluation and decision-making at each stage would ensure that ‘old habits’ of top-down policymaking do not re-establish themselves. With the policy cycle model, the process can be evaluated as we move from one stage to the other and at the final stage of the process (Hessing et al., 2005), and reciprocity can be monitored and adjusted throughout the policy cycle. In a model of co-production of knowledge for policy, the state would ensure that all actors impacted by the policy are involved in every stage of the policy cycle (Figure 2). The stage-by-stage evaluation may render this model complex, but it enables accountability and transparency among the Indigenous, state and non-state actors involved, to support reciprocity and trust needed for meaningful reconciliation.

Figure 2. The policy cycle model after inclusive policy reforms that consider trust and reciprocity.

Figure 2, an extended version of the policy cycle model in Figure 1, outlines opportunities for continuous Indigenous engagement into each stage of the policy cycle for any policy development implicated in UNDRIP and the TRC Calls to Action. In particular, providing more opportunities to better engage Indigenous Peoples in the implementation and evaluation stages will strengthen relationships and build the trust needed for the co-production of knowledge for better conservation policies. Continuous engagement with Indigenous knowledge systems enables a two-eyed seeing approach (Bartlett et al., 2012), which enhances policy outcomes. The following of appropriate Indigenous protocol, and the inclusion of at least proportionate numbers of Indigenous actors are important in all stages. We suggest the inclusion of Indigenous ceremony in every stage, suggested by participants as key to creating room for a ‘brave space’ where everyone has an opportunity to speak as equals. This practice is common amongst many Indigenous cultures and provides a safe, supportive environment for individuals to be vulnerable and connect with others. With the enactment of Bill C-29 in 2022, for the establishment of a national council for reconciliation, Indigenous inclusion at every stage may become imperative, with protocols specific to the territory.

Respecting Indigenous leadership in all stages of the policy cycle is not simply including Indigenous Peoples, but rather engagement needs to occur in culturally appropriate and meaningful ways (Ens et al., 2016). Implementing the vision of an extended policy cycle model (Figure 2) would require cultural competency and cultural humility training among policymakers. Meaningful engagement means that the very premise of the work may change, and that co-production of knowledge for policy may give rise to innovative ideas that advance conservation policy as a tool for reconciliation.

5.2 Weaving Indigenous and western sciences is needed to co-produce knowledge for sustainable conservation policies

Learning from different cultures and traditions may enhance our knowledge of nature and ability to make better decisions on how we interact with nature (Simpson, 2002). Such is the case with Indigenous knowledge on biodiversity that has played a significant role in conservation for ages (Loring and Moola, 2020; Moola et al., 2024; Smith, 2015). Although challenging, co-producing policy knowledge that weaves Western and Indigenous sciences together in a two-eyed seeing approach is more productive (Bartlett et al., 2012; Littlechild and Sutherland, 2021; Reid et al., 2021; Simpson, 2002) and supports reconciliation endeavours (Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018). The two-eyed seeing approach articulated by Elder Albert Marshal (Mi’kmaw from Nova Scotia) brings together different perspectives on biodiversity conservation (Bartlett et al., 2012). Research on this approach is growing rapidly, and Indigenous experts are contributing to the application of two-eyed seeing in conservation (Littlechild and Sutherland, 2021; Reid et al., 2021).

5.3 Indigenous participation means engaging Indigenous perspectives in conservation

The state needs to ensure that Indigenous Peoples are not only included in the whole policy process, but also that their knowledge systems are leading solutions to policy issues (Simpson, 2002; Smith and Sterritt, 2010; Wyborn, 2015). Doing so would mean going beyond conservation targets, removing bureaucratic obstacles (Fuller and Vu, 2011) and embracing a more holistic approach to conservation policy. Well documented in the ICE report, Indigenous approaches to conservation do not separate people from nature but aim to improve the relationship between people and nature, to support healthy ecosystems and healthy people (Indigenous Circle of Experts, 2018). The question from Eli Enns (interview, 2022) and other conservation actors about the 2030 targets should guide the way forward: “If 30 percent of Canada’s biodiversity is protected, then what?” With reconciliation on the agenda, we have to look beyond protected area targets and uplift Indigenous Peoples’ understanding of the relation to the land into conservation policies.

6 Conclusion

In this article, we have presented an overview of federal government efforts through the Pathway to innovate policymaking and collaborate better with Indigenous partners as recommended by the TRC and the UNDRIP. Obvious highlights of the Pathway process, worthy of replication, include engagement of Indigenous leaders and experts from the early stages of the process, appropriate funding of ICE, respect for Indigenous knowledge systems, and inclusion of Indigenous ceremony. The federal government followed through with funding for Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) and other Indigenous-led conservation activities, pointing towards a smooth pathway to the 2030 targets (Moola et al., 2024; Tamufor and Roth, 2022). We have also identified shortcomings in the process. The inclusion of Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge systems in the Pathway was dramatically reduced after the policy formulation and decision-making stages. This caused damages in the relationship that was beginning to grow and saw the return of mistrust of the government among Indigenous actors and communities. The loss of the traditional medicine bundle that was transferred to the Minister of ECCC in 2018 added to concern that Indigenous knowledges and perspectives were not being respected.

The Pathway has been a policy process rich with lessons, dealing with a “wicked” problem of biodiversity conservation, in a situation of diverse values and objectives (Zurba et al., 2019), and given the complexity, it was innovative in its quest for solutions. The endeavors of policymakers to engage with Indigenous Peoples have set the stage for more collaborative governance in policymaking in Canada. Currently, policymakers are focusing on fulfilling their pledges to the Global Biodiversity Framework and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which necessitates greater participation from Indigenous communities in shaping policies that impact them. As evidenced by the failure to maintain the level of Indigenous inclusion demonstrated in the early stages of the Pathway, settler-colonial structures and institutions are resistant to change. As Canada continues to work on its relationship with Indigenous Peoples and enhance policy tools for land protection as required by the Global Biodiversity Framework, it will be critical to learn from the Pathway and create a space where Indigenous Peoples and Nations can lead policy development and implementation, as suggested by Wyborn (2015). Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs), a key policy innovation emerging from Indigenous involvement in the Pathway process, need to be embedded in a policy framework that weaves Western and Indigenous sciences together and respects Indigenous protocol. It is our hope that the extended policy cycle elaborated upon in this article can assist in that endeavor.

7 Résumé

Dans cet article, nous analysons le processus de la politique de conservation de la biodiversité «En route vers l’objectif one du Canada » afin de déterminer son niveau d’inclusivité envers les peuples autochtones et leurs systèmes de connaissances. Cette politique, également nommée simplement « En route », se concentre sur l’objectif 1 des efforts du Canada pour atteindre l’objectif 11d'Aichi de la Convention sur la diversité biologique en 2020. L'étude vise à montrer l’importance et la signification de l’implication des peuples autochtones dans le processus politique. Inclure simplement des acteurs autochtones dans une politique ne signifie pas automatiquement que leurs contributions en matière de connaissances ont été prises en compte. Savoir pourquoi, quand et comment les peuples autochtones ont été impliqués dans le processus politique nous aide à comprendre le rôle que leur présence et leurs contributions ont joué dans la co-production de connaissances politiques pour éclairer le processus de la politique « En route vers l’objectif one du Canada ». Cela est fondamental pour la réconciliation et pour l’amélioration des politiques de conservation. Après un examen de l’histoire et de la structure de l’initiative « En route », en prêtant attention à l’importance d'établir des relations avec les peuples autochtones dès le début du processus politique, nous utilisons le modèle du cycle de politique publique, décrivant cinq étapes du processus de politique publique, pour développer notre analyse. Notre analyse est basée sur des entretiens menés avec des membres du processus « En route » et une revue des documents de politique nationale et internationale. Bien que nous ayons choisi le modèle du cycle de politique comme cadre général pour analyser les étapes du processus politique, il s’agit d’un modèle occidental qui n’est pas entièrement capable de refléter adéquatement les visions du monde autochtones. Son utilisation révèle cependant le degré d’engagement des acteurs autochtones à chaque étape, démontrant que « En route vers l’objectif one du Canada » a effectivement impliqué les peuples autochtones à certaines étapes, de manière potentiellement conforme à ce que demandent la Déclaration des Nations Unies sur les Droits des Peuples Autochtones (DNUDPA) et les Appels à l'Action de la Commission de Vérité et Réconciliation (CVR). Nous concluons par des recommandations pour une élaboration collaborative des politiques, qui serait plus attentive à l’inclusion des peuples autochtones et de leurs systèmes de connaissances à toutes les étapes du cycle de politique publique.

Mots clés: Politique de conservation de la biodiversité, processus politique, cycle de politique, peuples autochtones et systèmes de connaissances, En route vers l’objectif one du Canada, réconciliation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The University of Guelph Research Ethics Board, certificate number 19-10-026. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

NT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. RR: Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing–review and editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision. DM: Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was conducted as part of ET’s doctoral program, which was supported by the Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership (SSHRC grant #895-2019-1019).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2024.1434731/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1By a settler-colonial state, we refer to state regimes built on settler colonialism, which is defined as “a specific mode of domination where a community of exogenous settlers permanently displace to a new locale, eliminate or displace indigenous populations and sovereignties, and constitute an autonomous political body” (Veracini, 2019: 1).

2“Brave space” is a term often used by Indigenous Peoples and their allies in Canadian reconciliation fora to encourage intercultural dialogue and difficult conversations on topics like decolonization. It refers to a description of the atmosphere in the early stages of the Pathway which facilitated these difficult conversations. According to some ICE members, it requires bravery from beneficiaries of colonization to engage in decolonial discussions.

3Non-state actors in our framework refer to NGO representatives and scientists.

References

Adams, W. M., and Hutton, J. (2007). People, parks and poverty: political ecology and biodiversity conservation. Conservation Soc. 5 (2), 147–183.

Alvesson, M., and Sköldberg, K. (2017). Reflexive methodology: new vistas for qualitative research. London: Sage.

Ascher, W. (1986). The evolution of the policy sciences: understanding the rise and avoiding the fall. J. Policy Analysis Manag. 5 (2), 365–373. doi:10.1002/pam.4050050212

Ayres, R. (2021). Using the policy cycle: practice into theory and back again. Learn. Policy, Doing Policy 185, 185–203. doi:10.22459/lpdp.2021.08

Barker, A. J. (2015). ‘A direct act of resurgence, a direct act of sovereignty’: reflections on idle no more, Indigenous activism, and Canadian settler colonialism. Globalizations 12 (1), 43–65. doi:10.1080/14747731.2014.971531

Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., and Marshall, A. (2012). Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2, 331–340. doi:10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8

Baxter, R. R. (1980). International law in “her infinitye variety”. Int. & Comp. Law Q. 29 (4), 549–566. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/29.4.549

Beazley, K. F., and Olive, A. (2021). Transforming conservation in Canada: shifting policies and paradigms. FACETS 6 (1), 1714–1727. doi:10.1139/facets-2021-0144

Beck, S. (2011). Moving beyond the linear model of expertise? IPCC and the test of adaptation. Reg. Environ. Change 11 (2), 297–306. doi:10.1007/s10113-010-0136-2

Berkes, F., Colding, J., and Folke, C. (2000). Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol. Appl. 10 (5), 1251–1262. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1251:ROTEKA]2.0.CO;2

Binnema, T., and Niemi, M. (2006). ‘let the line be drawn now’: wilderness, conservation, and the exclusion of aboriginal people from banff national park in Canada. Environ. Hist. 11 (4), 724–750. doi:10.1093/envhis/11.4.724

Birkland, T. A. (2007). “Agenda setting in public policy,” in Handbook of public policy analysis: theory, politics, and methods. Editors F. Fischer, G. J. Miller, and M. S. Sidney (Boca Raton: CRC Press), 63–78.

Blackburn, C. (2019). “The treaty relationship and settler colonialism in Canada,” in Shifting forms of continental colonialism. Editors D. Schorkowitz, J. R. Chávez, and I. W. Schröder (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan). doi:10.1007/978-981-13-9817-9_16

Bouckaert, G., and Van de Walle, S. (2001). Government performance and trust in government. Ponencia Present. en la Annu. Conf. Eur. group public Adm. vaasa Finl. 2, 19–42.

Brondizio, E. S., Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y., Bates, P., Carino, J., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Ferrari, M. F., et al. (2021). Locally based, regionally manifested, and globally relevant: indigenous and local knowledge, values, and practices for nature. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 46, 481–509. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-012127

Brosius, J. P. (2004). Indigenous peoples and protected areas at the world parks congress. Conserv. Biol. 18 (3), 609–612. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.01834.x

Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (2021). The grades are in: a report card on Canada’s progress in protecting its land and ocean. Available at: https://cpaws.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/cpaws-reportcard2021-web.pdf (Accessed January 4, 2022).

Coggan, A., Carwardine, J., Fielke, S., and Whitten, S. (2021). Co-creating knowledge in environmental policy development. An analysis of knowledge co-creation in the review of the significant residual impact guidelines for environmental offsets in Queensland, Australia. Environ. Challenges 4, 100138. doi:10.1016/j.envc.2021.100138

Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership (CRP). (2021). Year two of our seven-year journey. Available at: https://conservation-reconciliation.ca/2020-annual-report. Accessed March 20, 2022.

Convention on Biological Diversity (2010). Decisions adopted by the conference of the parties to the convention on biological diversity at its tenth meeting (decision X/2, annex IV). Nagoya, Japan: Convention on Biological Diversity. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-10/cop-10-dec-02-en.pdf (Accessed March 20, 2022).

Coon Come, M. (2015). “Cree experience with treaty implementation,” in Keeping promises: the royal proclamation of 1763, aboriginal rights, and treaties in Canada. Editors T. Fenge, and J. Aldridge (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press), 153–172.

Cooper, C. A., Knotts, H. G., and Brennan, K. M. (2008). The importance of trust in government for public administration: the case of zoning. Public Adm. Rev. 6893, 459–468. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.00882.x

Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red skin, white masks: rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press.

Duhamel, K. (2022). The united nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Available at: https://humanrights.ca/story/the-united-nations-declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples (Accessed August 11, 2023).

Ens, E., Mitchell, L. S., Yugul, M. R., Craig, M., and Rebecca, P. (2016). Putting indigenous conservation policy into practice delivers biodiversity and cultural benefits. Biodivers. Conservation 25 (14), 2889–2906. doi:10.1007/s10531-016-1207-6

Environment and Climate Change Canada (2016). 2020 Biodiversity goals and targets for Canada. Available at: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2016/eccc/CW66-524-2016-eng.pdf (Accessed October 18, 2022).

Environment and Climate Change Canada. (2022). Up to $40 million in Indigenous-led area-based conservation funding now available. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/news/2022/09/up-to-40-million-in-indigenous-led-area-based-conservation-funding-now-available.html. Accessed July 18, 2023.

Fuller, B. W., and Vu, K. M. (2011). Exploring the dynamics of policy interaction: feedback among and impacts from multiple, concurrently applied policy approaches for promoting collaboration. J. Policy Analysis Manag. 30 (2), 359–380. doi:10.1002/pam.20572

Global Biodiversity Framework (2022). Kunming-montreal global biodiversity framework. Convention Biol. Divers. Kunming-Montreal Glob. Biodivers. Framew. (cbd.int).

Government of Canada (2017). Press release: federal and provincial governments create national advisory Panel on Canada’s biodiversity conservation initiative. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/parks-canada/news/2017/06/federal_and_provincialgovernmentscreatenationaladvisorypanelonca.html (Accessed August 20, 2022).

Government of Canada (2018). “The recognition and implementation of rights framework talk. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-justice/news/2018/04/the-recognition-and-implementation-of-rights-framework-talk-1.html (Accessed August 20, 2022).

Government of Canada (2021). Government of Canada announces $340 million to support Indigenous-led conservation. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/news/2021/08/government-of-canada-announces-340-million-to-support-indigenous-led-conservation.html. (Accessed September 10, 2023).

Government of Canada. (2022). Canada nature fund. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/nature-legacy/fund.html. Accessed September 10, 2023.

Harvey, W. S. (2011). Strategies for conducting elite interviews. Qual. Res. 11 (4), 431–441. doi:10.1177/1468794111404329

Henderson, J., and Wakeham, P. (2009). Colonial reckoning, national reconciliation? aboriginal peoples and the culture of redress in Canada. ESC Engl. Stud. Can. 35 (1), 1–26. doi:10.1353/esc.0.0168

Hessing, M., Howlett, M., and Summerville, T. (2005). Canadian natural resource and environmental policy: political economy and public policy. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Howlett, M. (2009). Policy analytical capacity and evidence-based policy-making: lessons from Canada. Can. public Adm. 52 (2), 153–175. doi:10.1111/j.1754-7121.2009.00070_1.x

Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., and Perl, A. (2009) Studying public policy: policy cycles and policy subsystems, 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hupe, P. L., and Hill, M. J. (2006). “The three action levels of governance: Re-framing the policy process beyond the stages model,” in Handbook of public policy. Editors J. Pierre, and B. G. Peters (London: Sage), 13–30.

Indigenous Circle of Experts (ICE) (2018). We rise together: achieving pathway to Canada target 1 through the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the spirit and practice of reconciliation. Available at: http://www.conservation2020canada.ca/resources/(Accessed August 20, 2022).

Jann, W., and Wegrich, K. (2017). “Theories of the policy cycle,” in Handbook of public policy analysis: theory, politics, and methods. Editors F. Fischer, G. J. Miller, and M. S. Sidney (New York: Routledge), 69–88.

Jiang, T., Gao, H., Chen, G., Dai, X., Xu, W., and Wang, Z. (2024). The complexity of environmental policy implementation in China: a set-theoretic approach to environmental monitoring policy dynamics. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1335569. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2023.1335569

Jordaan, S. M., Davidson, A., Nazari, J. A., and Herremans, I. M. (2019). The dynamics of advancing climate policy in federal political systems. Environ. Policy Gov. 29 (3), 220–234. doi:10.1002/eet.1849

Kingdon, J. W. (1995). Agenda, alternatives, and public policies. 2nd Edition. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers.

Kohler, F., and Brondizio, E. S. (2017). Considering the needs of indigenous and local populations in conservation programs. Conserv. Biol. 31 (2), 245–251. doi:10.1111/cobi.12843

Kolb, R. (2006). Principles as sources of international law (with special reference to good faith). Neth. Int. law Rev. 53 (1), 1–36. doi:10.1017/S0165070X06000015

Laws, S., Harper, C., Jones, N., and Marcus, R. (2013). Research for development: a practical guide. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Littlechild, D., and Sutherland, C. (2021). Enacting and operationalizing ethical space and two-eyed seeing in indigenous protected and conserved areas and crown protected and conserved areas. Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d3f1e8262d8ed00013cdff1/t/6166ee2f2dc5b13b0e44fb63/1634135600122/Enacting+and+Operationalizing+Ethical+Space+in+IPCAs+and+Crown+Protected+and+Conserved+Areas+-+June+4.pdf (Accessed April 27, 2023).

Longhurst, R. (2010). “Semi-structured interviews and focus groups,” in Key methods in geography. Editors N. Clifford, S. French, and G. Valentine (London: SAGE Publications Ltd).

Loring, P. A., and Moola, F. (2020). Erasure of Indigenous Peoples risks perpetuating conservation’s colonial harms and undermining its future effectiveness. Conserv. Lett. 14 (2), e12782. doi:10.1111/conl.12782

MacDonald, D. B. (2016). Do we need kiwi lessons in biculturalism? Considering the usefulness of aotearoa/New Zealand's pākehā identity in Re-articulating indigenous settler relations in Canada. Can. J. Political Science/Revue Can. de Sci. politique 49 (4), 643–664. doi:10.1017/S0008423916000950