- 1Resource Economics Group, Humboldt University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2Research Area 2 “Land Use and Governance”, Working Group SusLAND, Leibniz Center for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF), Müncheberg, Germany

- 3JAINA Studies Community, Tarija, Bolivia

- 4International Water Management Institute, Colombo, Sri Lanka

- 5Independent Researcher, Siem Reap, Cambodia

- 6International Water Management Institute (Laos), Vientiane, Lao People’s Democratic Republic

- 7Political Sociology post graduation program, Vila Velha University, Vila Velha, Espirito Santo, Brazil

In rural Cambodia, inland freshwater and rice field fisheries are key sources of income, animal protein, and important ecosystem services. As the flood pulse in the Tonlé Sap floodplain recedes post-monsoon, leaving rice fields and local water bodies dry, Community Fish Refuges (CFRs) offer a promising path to sustain dry season fish stocks, aquatic biodiversity, and secure water for agriculture and husbandry. Their sustained physical integrity and productivity as multiple-use systems hinge on communities’ ability to manage these systems collectively. To explore whether the studied communities have been able to respond to the challenge of collectively governing CFR, we investigate two CFR sites that were established in 2016 by local and international organizations alongside State authorities. Our aim is to investigate two key aspects: 1) the presence, extent, and efficacy of community-level collective action (CA) for managing CFRs; and 2) the factors that either facilitate or inhibit CA regarding CFRs. We conducted a qualitative case study between March and May 2023 at two sites in Kampong Thom Province. These were selected because while they have similar ecological features, they show different management results according to the implementing international organization WorldFish. This paper delves into a process guided by external agents seeking to reshape local behavior and existing institutional frameworks. Results show how centralized power structures and entrenched rural patronage politics in villages limit villagers’ participation and agency in CFRs management. Villagers encounter constraints hindering their capacity to instigate change, prompting a re-evaluation of the CFR Committee’s composition and operation to ensure broader legitimacy among actors. While emphasizing extended project funding and informed external intervention strategies, the study underscores doubts about short-term CA feasibility. It highlights the critical influence of contextual factors and policymakers’ assumptions in achieving effective collective governance. Structural factors and the deeply human process of pulling together a plurality of stakeholders pose challenges to establishing community-based projects prioritizing diverse voices.

1 Introduction

Inland fisheries play a multifaceted role in supporting economy, culture, environment, and food security (Funge-Smith and Bennett, 2019; Muthmainnah et al., 2019). Cambodia’s inland fisheries are part of the Mekong River system, with Tonlé Sap (TS) at the heart of freshwater fisheries for people living in the TS and Mekong floodplains. The central region of Cambodia is strongly shaped by the dynamics of the TS. While our study sites are not situated within the floodplain itself, they lie within its basin (FAO, 2023). Fish is the primary protein source for rural Cambodian families, in a country where 75% of its population is rural (World Bank, 2024). Rice, the country’s staple crop, is an important source of food and nutrition security (Freed et al., 2020b). Thus, initiatives that support fish conservation and its productivity in rice field landscapes are key for supporting well-nourished rural populations. Community Fish Refuges (CFR) – centered around dry season water storage infrastructure–can play a vital role as dry season repositories for fish and other aquatic biodiversity in anticipation of the next flood cycle when aquatic life in the CFRs spreads across the rice-fields and other seasonal water bodies. CFRs can be natural, human-made, or a combination thereof. In addition to maintaining fish stocks and aquatic biodiversity, CFRs provide water for animals and, in some cases, for irrigation and household consumption depending on the size of the CFR (see Figure 1). Consequently, CFRs improve food security by reducing food expenditure and supporting the diversity of aquatic foods (WorldFish, 2021b). However, while it is a promising innovation in ecological terms (Freed et al., 2020a), it is necessary to problematize to what extent community-managed mechanisms for sustaining CFRs can emerge in current contexts in rural Cambodia. CFRs must be managed in terms of infrastructure and competing uses, keeping in mind that they are a fish refuge. This implies changes in the forms of resource management where stakeholders must establish appropriate governance structures and rules that promote equity of use across different users and sustainability. Therefore CFRs represent a multi-dimensional challenge for common-pool-resource (CPR) management that demands new ways of social organizing, learning, and decision making.

Figure 1. Main physical components of the Community Fish Refuge system source: Kim et al., 2019.

Since the 1990s, CFR initiatives have demonstrated positive ecological outcomes and enhanced food security, particularly benefiting marginalized communities. These efforts have attracted attention from the State, with international organizations funding projects through WorldFish, which, in turn, collaborates with local NGOs for implementation. Studies examine community members’ awareness of CFR management and its socioeconomic impacts (Phala et al., 2019). Insights are also gained from project implementation, focusing on both technical and social design, leading to the proposal of community governance models (Brooks et al., 2015; Joffre and Sheriff, 2011; Kim et al., 2019) and the integration of nutrition and gender considerations into CFR management (Shieh et al., 2019). While studies offer insights into various management features, there are no existing studies that examine the effectiveness of institutions responsible for the collective management of CFRs—namely, the CFR Committees and the broader village communities—in addressing the challenges of long-term social sustainability in collective governance. Previous management studies mainly focus on the management committee or on household awareness of the CFR (Joffre and Sheriff, 2011; Kim et al., 2019; Phala et al., 2019). They do not look at collective action at the community level and how collective agreements can be reached under existing conditions. This article addresses this gap by drawing on research in rural Cambodia to explore the relationships between institutional arrangements, social histories, structures and relations, actor perceptions and rationales, as well as the broader governance contexts for CFR management. We also use our findings to reflect upon current frameworks and discourses around common-pool-resource (CPR) management, in particular to highlight insights on the feasibility of bridging the gap between the management conditions envisaged in Ostrom’s design principles (Ostrom, 1990) and local contexts without strong traditions of CPR management. Thus, we investigate: 1) the presence, extent, and efficacy of community-level collective action (CA) for managing CFRs); and 2) the factors that either facilitate or inhibit CA regarding CFRs. We believe that our research provides insights into the social sustainability of the project and deepens the social dynamics understanding, which are crucial for enhancing the ecological outcomes and improvements in food and nutrition achieved so far.

Our approach is grounded in three critical underlying assumptions: 1) not all projects that work well in ecological terms do equally well in social terms, presenting challenges for managing and sustaining social-ecological systems; 2) externally driven community governance projects will struggle to involve actors and build equitable and context-responsive governance systems at the local level, if existing contextual conditions constrain actor agency; and 3) an adequate management of social-ecological transformations hinges guaranteeing equitable benefits for all involved actors and ensuring that those benefiting from CFRs possess a fundamental recognition of rights, empowering their participation in decision-making processes. Therefore, the social sustainability of CFR management relies heavily on CA by all stakeholders, encompassing both social and ecological outcomes. This management challenge calls for transformations in social relations.

2 Literature review

Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) projects typically have promising intentions, aiming to engage communities in bottom-up processes that allow people to participate in and influence natural resources governance through collaborative arrangements. However, the current definitions of community in institutional economics not just have a sociological deficit in studying CAs but also problematize the nature of community (Hall et al., 2014). In this tradition, CA and its policy applications often depend on idealized views of community, which may overlook the challenges posed by actors’ heterogeneity in rule-making (Hall et al., 2014). CA is perceived as the desirable outcome when individuals with bounded rationality work together for mutual and collective benefit (Cleaver, 2012). However, the relational factors that affect the effectiveness of managing resources could be underrepresented or not addressed in socio-economic diagnosis (Meinzen-Dick, 2007). Moreover, policy instruments and international development projects are often derived from Western ideals of institutions and their democratic mechanisms (Hall et al., 2014); yet existing institutions may not be compatible with the ideals underlying such projects, while adaptation processes may result in other, possibly unexpected, institutional forms. In such settings, the concept of institutional bricolage is useful in understanding how local institutions take shape, referring to the process whereby existing arrangements are modified by usually local actors to reflect needs and value systems, leading to acceptable ways of doing things in a particular society (Cleaver and Whaley, 2018).

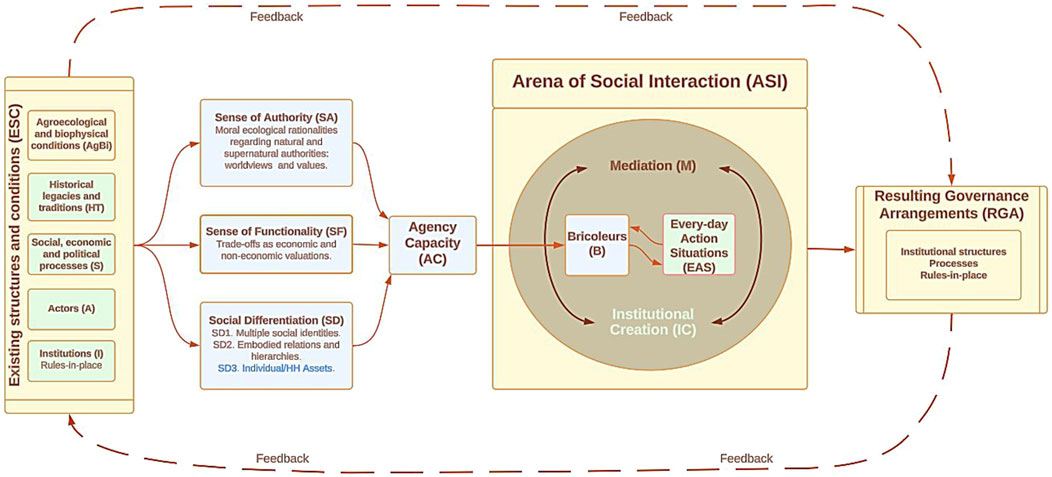

We use a Conceptual Framework (Figure 2) drawing on elements of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework (IADF), Critical Institutionalism (CI), and the Sustainable Livelihoods framework (SLF). These approaches allows us to incorporate a more nuanced understanding of social processes, ultimately reflecting the performance of institutions from the perspectives of multiple actors.

The IAD framework was designed to identify how humans collaborate, establish organizations and regulations, and make decisions to attain desired outcomes, facilitating comparative institutional analysis across cases (Hess and Ostrom, 2005). It was initially designed to study how institutional arrangements are contributing to sustainable resource use of CPR (Kimmich et al., 2023). Its underlying assumptions come from resource economics and political science (Ostrom, 2012). The genesis of this framework stems from Elinor Ostrom’s aim to study self-governing forms of collective action, emphasizing community involvement and evolving rules (Ostrom, 1990; Ostrom, 2014). She sought to identify enduring institutional patterns, called later design principles (Ostrom, 2008; Ostrom, 2009b). In this context, enduring institutional arrangement that adapt operational rules over time based on higher-level rules are called robust institutions (Anderies et al., 2003; Ostrom, 2008). We use Ostrom’s principles as an analytical lens for assessing CFR performance.

The CI is a body of thought that explores how institutions mediate relationships between people, common goods, and society. It draws on critical realist thinking and critical social theories (Cleaver and De Koning, 2015). It encourages the questioning of the underlying assumptions of economic institutionalism, such as those of the IAD framework. However, it also has commonalities and complementarities with respect to studying the commons (Clement, 2010; Whaley, 2018). The term institutional bricolage is used by CI scholars to understand how institutional change happens, recognizing the creativity of people to adapt, but also the constraints inherent in those processes of adaptation (Cleaver, 2012). Following Sehring (2009) approach, we use bricolage to describe a non-teleological process in which actors are constrained by institutions at the time they participate in shaping and reinterpreting them. Thus, bricolage is situated between path dependency and the development of alternative and “new” institutions.

SLF helps us understand the diverse factors shaping an individual’s livelihood outcomes, linking the interplay between physical, human, social, environmental, and political capitals. Institutional analysis is key for the framework given that it mediate the ability to carry out strategies and achieve outcomes (Scoones, 2015), while understanding actors’ livelihood outcomes and underlying capitals helps explore actors’ perceptions of their agency and decision-making around participation in CA. In theory, local actors can generate CA by challenging long-standing ideas, and modifying previous institutions. CA involves multiple individuals contributing to a shared effort to achieve a common goal (Erwin et al., 2023). However, given that power differentials between actors are common, the degree of agency of the actors involved must be questioned, especially in places where patronage politics in agrarian settings involve historically established social ties that are not likely to change in the short term, such as in South East Asia (Sithirith, 2014; Scott, 1972). From the perspective of historical anthropology, studies such as those of Blanton and Fargher (2007) reveal the social complexity inherent in collective action. The formation of Asian states was often characterized by reliance on the labor of subaltern groups, who were often considered to have little or no political agency. These groups were often denied the right to organize locally or to have a voice in governance at the local or national level (Scott, 1985). This highlights the challenges of the establishment of a project with a focus on the collective management of common goods in a challenging regional context. This paper explores the limitations of individual and collective agency in shaping CA processes and outcomes. It emphasizes the significance of integrating diverse human factors—such as capacity for participation, value systems, and gendered differences—for understanding of local contexts in institutional formation to comprehend the real possibilities for people to participate in community governance.

The IAD framework, while robust for analyzing institutions, might overlook localized informal institutions in place and the real agency that actors have. The IAD assumes that actors are bounded rational, that they seek to achieve goals for themselves and for the communities to which they identify, and are capable of making conscious choices as members of groups (McGinnis, 2011). However, people cannot always influence collective outcomes in homogeneous ways. Instead, the agency is constrained by an individual’s position in society and shaped by power relations, struggles, processes of negotiation, and the enforcement of rules and regulations (Cleaver, 2012; Sakketa, 2018). CI is an appropriate approach for this because it considers the agency as socially situated, considering how marginalized people can participate and work in institutions for NRM, not that some of them participate and work (Liebrand, 2015). It also critically assesses who are the people who can make decisions within a collective, and how the rules are not only shaped but also shape the behavior of the actors (Jones, 2015). Cleaver’s theorization of the role of individual agency in CA explores an understandings of how individual human agency shapes and is shaped by social relations and institutions (Cleaver, 2007).

We take a cross-cutting political economy approach to the conceptual framework to ensure our methods and analysis account for issues related to power, interests, influences, and systemic constraints, such as those arising from historical legacies and its reproduction in institutional making (Scoones, 2015; Pichon, 2019). These elements contribute to the Conceptual Framework’s ability to facilitate a grounded assessment of whether the CFR Committees (CFRC), in their current form, are appropriate institutional arrangements capable of representing diverse CFR users and promoting collective planning for system sustainability and equitable benefit sharing that includes conflict mitigation mechanisms when dry season water levels may call for negotiated limits to water usage to maintain functionality as a fish refuge.

We stress that a framework is “a guide to thinking rather than a description of reality” and that “it is a heuristic model of how things might interact” (Scoones, 2015). Thus, we recognize that any single framework is unlikely to be sufficient to fully encompass the social-ecological complexity inherent in human actions and social systems.

The framework includes several key elements:

• Structural Conditions (ESC) serve as the foundation for the existence and development of institutions and organizations that have a significant impact on livelihoods. Within this framework, several interrelated factors contribute to the management of CPRs.

• Agro-ecological, biophysical, and related processes (AgBi) alongside historical legacies and traditions (HT) provide essential context. AgBi are the changes that natural resources undergo over time, while HT addresses historical variables, such as past events and societal changes, providing insights into institutional changes within specific societal frameworks.

• Policy settings (S) and actors (A) play critical roles in shaping governance dynamics. S includes laws and macroeconomic conditions that affect local governance, while A includes individuals, groups, or organizations within social-ecological systems that influence, or are influenced by, decision-making processes. Institutions (I) include formal, informal, and hybrid arrangements that take place in the context and shape human behavior.

• Agency capacity (AC) reflects the ability of individuals to act meaningfully within social structures. There are factors that condition and influence this agency. These are: a) Sense of Authority (SA), which indicates the factors that shape human behavior within social structures, such as the moral and ecological rationalities that guide agency and behavior within these institutions; b) Sense of Functionality (SF), which includes economic and non-economic valuations that influence collective action (CA) and institutional arrangements; and c) Social Differentiation (SD), provides insights into governance by focusing on the micro-level differences within communities, such as social identities, embodied differences like class and gender, and the influence of household assets.

• Bricoleurs (B) drive institutional reformulation and influence the resulting governance arrangements (RGA). These arrangements, which emerge from social interactions within everyday action situations (EAS), influence existing structural conditions through feedback loops, completing the cycle of governance dynamics within socio-ecological systems.

• For the management of CPRs to take place, mediation (M) processes facilitate interaction between actors with different agency capacities and knowledge through brokerage processes.

• EAS and Institutional Creation (IC) are dynamic processes that shape governance outcomes. EAS describes the dynamic management practices of CPRs that influence societal structures and norms, while IC involves the creation and adaptation of agreements over time that shape governance arrangements. In an arena of social interaction (ASI), EAS and IC take place as part of the bricoleurs’ interactions for daily CPR management.

• Resulting governance arrangements (RGA). These are the CPR’s institutional structures and processes observed as ASI outputs. These include processes and rules used to manage the CPR. These RGA will feed back into the ESC. This graph shows a linearity in the process. However, it is important to emphasize that there is constant feedback between the ASI, RGA, and the ESC. RGA will be analyzed according to the Design Principles proposed by Elinor Ostrom, as described below.

See Supplementary Material 1 for a more detailed description.

Ostrom looked for the specific rules associated with long-lived, self-organized, and self-governed CPRs in order to uncover broader institutional patterns common to these enduring systems of CPR management. A robust institution, as defined by Shepsle, persists over time, with operational rules evolving in accordance with higher-level rules (Ostrom, 1990). This led to the definition of “design principles,” which are the conscious or unconscious ideas that guide individuals in organizing and reorganizing their associations, i.e., guiding them to create CA (Ostrom, 2009a). She suggested eight design principles to distinguish between robust and collapsed systems. In addition, Ostrom identified theoretical models showing how trust and reciprocity can increase in settings with clear boundaries and repetitive exchanges (Ostrom, 2007). Robust systems would fulfil most of the following design principles:

1. Clearly defined boundaries. The boundaries of the resource system (e.g., irrigation system or fishery) and the individuals or households with rights to harvest resource units are clearly defined.

2. Proportional equivalence between benefits and costs. Rules specifying the amount of resource products that a user is allocated are related to local conditions and to rules requiring labor, materials, and/or money inputs.

3. Collective-choice arrangements. Many of the individuals affected by harvesting and protection rules are included in the group who can modify these rules.

4. Monitoring. Monitors, who actively audit biophysical conditions and user behavior, are at least partially accountable to the users and/or are the users themselves.

5. Graduated sanctions. Users who violate rules-in-use are likely to receive graduated sanctions (depending on the seriousness and context of the offense) from other users, from officials accountable to these users, or from both.

6. Conflict-resolution mechanisms. Users and their officials have rapid access to low-cost, local arenas to resolve conflict among users or between users and officials.

7. Minimal recognition of rights to organize. The rights of users to devise their own institutions are not challenged by external governmental authorities, and users have long-term tenure rights to the resource.

For resources that are parts of larger systems:

8. Nestled enterprises. Appropriation, provision, monitoring, enforcement, conflict resolution, and governance activities are organized in multiple layers of nested enterprises (Ostrom, 1990; Hess and Ostrom, 2005).

She recognized the existence of both successful cases (from which these principles were derived) and others of fragility and failure (Ostrom, 1990). In her 1990 book, Ostrom presents the case of a Sri Lankan fishery where CA failed due to the absence of local debate and decision-making spaces at the local level. Political relations between local villagers and elected state officials revolved around patronage positions given to leaders in exchange for electoral support (p. 156). Other factors that can contribute to institutional fragility and failure include the dissipation of rents due to the number of beneficiaries, undefined boundaries, unrecognized rights to organize, and a lack of conflict resolution mechanisms (p. 179).

Evidence from Cambodia indicates that there are significant challenges associated with CA in community-based inland fisheries. In their study of community-based fish culture, Joffre and Sheriff (2011) note that past experiences of collective action in Cambodia, such as the Khmer Rouge regime and forced collectivization, have negatively impacted people’s perceptions of collective initiatives. This is reflected in communication problems, trust issues, and a desire to work individually. The sharing of information is particularly challenging, with villagers frequently citing poor communication, and a lack of cooperation among, village leaders. De Silva et al. (2017) present examples of Community Fisheries (CFis) initiatives in the Tonlé Sap region that faced CA challenges due to lack of awareness of the project among local authorities, difficulties in coordination among actors, and lack of experience in project management, among others. These initiatives were able to overcome certain difficulties through deliberative processes, identifying common grounds for action and negotiating solutions within actor networks, with extensive external support channeling most of these processes. Importantly, De Silva et al. (2017) acknowledge the challenges associated with the control of productive resources and the embeddedness of patronage networks. In a study on small-scale aquaculture in the Mekong Delta of Cambodia and Vietnam, Werthmann (2012) notes a discrepancy between the external factors that impede the success of CA and the internal motivation of villagers. External issues–such as property rights, technical challenges, and NRM regulations that do not align with local conditions–are at odds with the potential trust and cooperation between villagers demonstrated in field experiments. However, the same villagers expressed challenges to cooperation within the village. This shows that even when there is potential motivation for CA, there are challenges to its emergence. In an assessment of CFis in Cambodia, Kurien (2017) finds that most of the design principles are met, calling CFis “modern commons” because they are a novel management system, similar to CFRs. However, Kurien notes that community members still have difficulty fully realizing their rights and responsibilities in communing. It is crucial to underscore that, given the current political context in Cambodia, studies that examine power dynamics and the governance of common goods in rural areas may be restricted and face content control (Beban et al., 2019). These examples highlight how the successes or failures of CA initiatives are often determined by a complex mix of variables, thus giving us the context of the Cambodian context and its challenges for community-based CA from diverse studies on aquatic food systems.

3 Methodology

3.1 Study sites

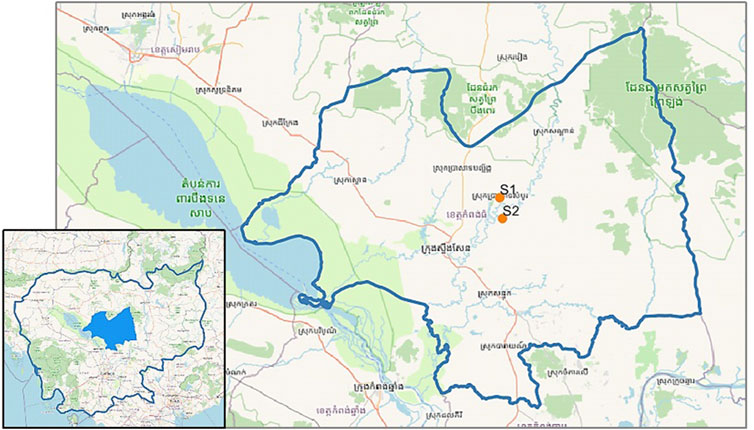

Kampong Thom province is located in Cambodia’s central region (Figure 3), where rural villages are primarily inhabited by Khmer people who rely on agriculture as their primary source of income. Historically, rice production is their primary crop; however, cassava and cashew production are becoming increasingly important. Yet many families lack regular cash income and rely on remittances from family members working as migrant workers in Phnom Penh or other countries, creating new challenges for the sustainability of agriculture (Ministry of Economy and Finance of Cambodia, 2019) (Figure 3).

Fishing is a supplementary activity for most families with a minority of rural households deriving direct income from fishing. Although official estimates place RFF at 30%, field-based studies estimate a contribution of RFF equivalent to 60%–70% of inland fisheries production (Freed et al., 2020a). Thus, CFRs that preserve dry season fish habitat within RFF landscapes provide an important function for improving RFF productivity and fostering sustainability of these integrated agricultural systems (Kim et al., 2019).

A CFRC comprises five to ten local elected volunteers, who oversee the management of the CFR. With support from local authorities and the Fisheries Administration Cantonment, the CFRC can obtain official recognition for the CFR from the Provincial Department of Agriculture. The membership of the committees include the Committee Chief, Deputy Chief, Secretary, Cashier, and the CFR patrolling team. Each committee is not just responsible for patrolling the CFR and the wider ZOI, but also raising awareness, information sharing, fund raising for the CFR, establishing by-laws to define responsibilities of its members, as well as defining those actions that are allowed in the CFR and no-fishing area (Kim et al., 2019).

One of the main challenges facing CFRs in Cambodia is the potential for conflict over water use during the dry season, where there are competing interests over water resources for activities such as rice cultivation, livestock breeding, human consumption, and fish conservation, particularly in times of drought (Sithirith et al., 2024). A study conducted in 2013 highlighted the initially limited capacity of local communities, NGO partners, and authorities to implement technical interventions and effectively manage CFRs, exacerbated by external factors such as environmental changes and fluctuations in rainfall and flood patterns (Kim et al., 2019). In addition, another study (Phala et al., 2019), identified illegal fishing, inadequate financial support, and low beneficiary participation as affecting CFR outcomes. Respondents in this study emphasized the importance of strengthening infrastructure such as culverts, dikes, and pond cleaning to improve the resilience of CFR.

3.2 Materials and methods

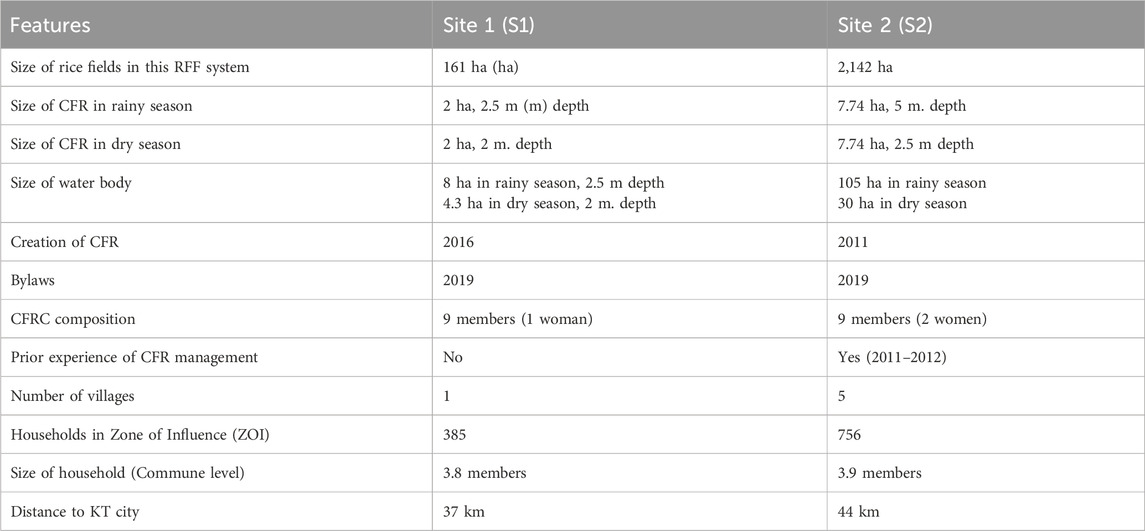

The case study sites were selected after evaluating eleven CFRs from March 2022 to January 2023, including field visits, interviews, focus groups, and meetings with staff of WorldFish, the international research organization. The two selected locations have similar ecological characteristics including large water bodies with extensive flooding areas, in which their respective CFRs are relatively small compared to the total area of water (Kim et al., 2019). What differed, and what was of particular interest for this research, was that the sites were categorized by WorldFish as having contrasting performance in terms of CFR management since the project implementation in 2016. S1 was categorized as underperforming on local CFR project management while S2 was considered to have better management. This performance assessment by WorldFish was based on the Project Governance Manual and use of a tool that evaluates organizational management, planning and implementation capacity, funding strategies, networking, as well as women’s representation and participation (Kim et al., 2019). The characteristics of our study sites are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Features of study sites sources: report for RFF project, phase II 2016–2021. Bylaws (2019). Interviews.

Our field work during March through May consisted of the following steps sequentially.

1) Community mapping as a scoping method, to ascertain a spatial understanding of the setting of the villages; the diversity, locations, and extents of natural resources especially in relation to the CFR; who and how many people live where and how; who, when, and how people interact with their agroecology, especially the CFR infrastructure. In S2, a collective meeting was held for this purpose, with the participation of n = 10 people, representatives of the CFRC, and village chiefs. In S1, it was not possible to organize such a meeting, the map was made from individual contributions of n = 7 people where each contributor added to the map iteratively. As a scoping method, community mapping effectively provided valuable insights into the continuity of the CFR committee. It offered an initial overview of the community’s physical, biophysical, and social landscape, allowing us to gather preliminary information on interpersonal interactions. The interviews then explored these relationships in greater depth. In that sense, the inability to conduct a collective mapping meeting in S1 due to coordination challenges with local authorities revealed organizational gaps within the CFR committee. In contrast to S2, where structures were clearly defined, the lack of clarity around management roles in S1 created uncertainty around committee membership and leadership, as well as prevented coordination with local actors. This variation highlights differences in organizational continuity between sites, providing useful insights into local governance challenges during this initial mapping exercise.

2) Visits to the villages and CFR systems for validating the maps through visual verification.

3) Semi-structured interviews (n = 95): 65% were village households representing livelihoods, gender, and class diversity; 17% were formal village representations such as Commune Council (CC) representatives, village representatives, and CFRC members; 5% were monks from the village Pagoda; 7% were Pagoda representatives (local intermediaries between the monks and villagers); 2% elder’s groups representatives; 2% police officers; and 1% other religious groups representations (Christian church). We iteratively conducted interviews across four phases of fieldwork over the 3-month period in Cambodia. This approach allowed for reflective pauses between each round to evaluate data, adjust methods and tools, and enhance our empirical understanding of theoretical categories. The sampling process focused on selecting interviewees based on their potential to illuminate our research questions, deepen our understanding of key processes, and compare the theories related to our conceptual framework to emerging field data (Ligita et al., 2019; 2019; Eisenhardt et al., 2016). We sought to include individuals in both formal and informal roles within village social structures, we prioritized diversity in livelihoods, class, gender, social roles, and significance within rural society to ensure a plurality of perspectives. Most respondents were households (65%), as we aimed to capture the collective agency across a broad demographic scope rather than formal representations and vocal voices. To facilitate effective sampling, we employed both snowball and convenience sampling, alternating based on circumstances to minimize bias. Interviews were conducted in respondents’ homes, religious sites, or workplaces, typically lasting around 1 hour, with durations ranging from twenty-five minutes to one and a half hours.

The interviews were conducted as a three person group, all co-authors of this publication. Two non-local people asked the questions and then recorded the answers in a notebook, while one local person played the role of simultaneous Khmer-English translator and vice versa, and knowledge/cultural broker. The two non-locals, from diverse identity backgrounds, brought theoretical perspectives and work experience in related processes. The translator is a local from a neighboring area to the study site, knowledgeable about rural dynamics and the ecology of the environment with local and empirical knowledge of RFF. The process involved a knowledge co-construction between the team and the local villages in the field. Biases were managed by recruiting respondents from a variety of locations and backgrounds in the village, having daily evaluation meetings among the group of interviewers to analyze the responses, methodological process, and cultural biases. The interview process involved informing participants about the purpose and use of their responses prior to obtaining their consent, with registration on confidential lists taken upon acceptance.

In addition, we conducted semi-structured interviews with three people related to WorldFish implementing the project (WorldFish and Trailblazer Cambodia Organization - TCO), two interviews with Cambodian scholars studying social issues in rural areas of Cambodia, and one interview with a state organization at the provincial level (Fisheries Administration). The six of the above interviews were conducted in English and by the two non-locals. The last interview was conducted in the same manner as the village-level interviews. In total, n = 102 interviews were conducted in the period March - May 2023.

During the fieldwork period, we resided in villages with local families, which afforded us the opportunity to observe and conduct unstructured visits to villages and CFRs. This allowed for insights into the local landscape and general social organization. However, there were some limitations due to language barriers and differences in cultural understanding.

4) A revisiting transect walk was conducted at the end of the three-month fieldwork. The final revisit was guided by a local fisherman and the same procedure was used in both study areas. This approach allowed for further validation of the understanding of the socioecology of the CFR system based on knowledge gathered previously in field and also to triangulate findings.

The data analysis was carried out both iteratively throughout data collection and comprehensively at the conclusion of fieldwork. During the iterative phase, analysis was integrated with the sampling process, with team discussions following each round of fieldwork to assess findings and adjust methods as necessary, employing both inductive and deductive approaches. At the end of the fieldwork, field notes were digitized in Microsoft Word and organized in Microsoft Excel. We then familiarized ourselves with the data through pre-coding and open coding, followed by a deductive content analysis in NVIVO12, guided by the conceptual categories from our theoretical framework (Saldaña, 2013).

4 Results

4.1 Existing structures and conditions (ESC)

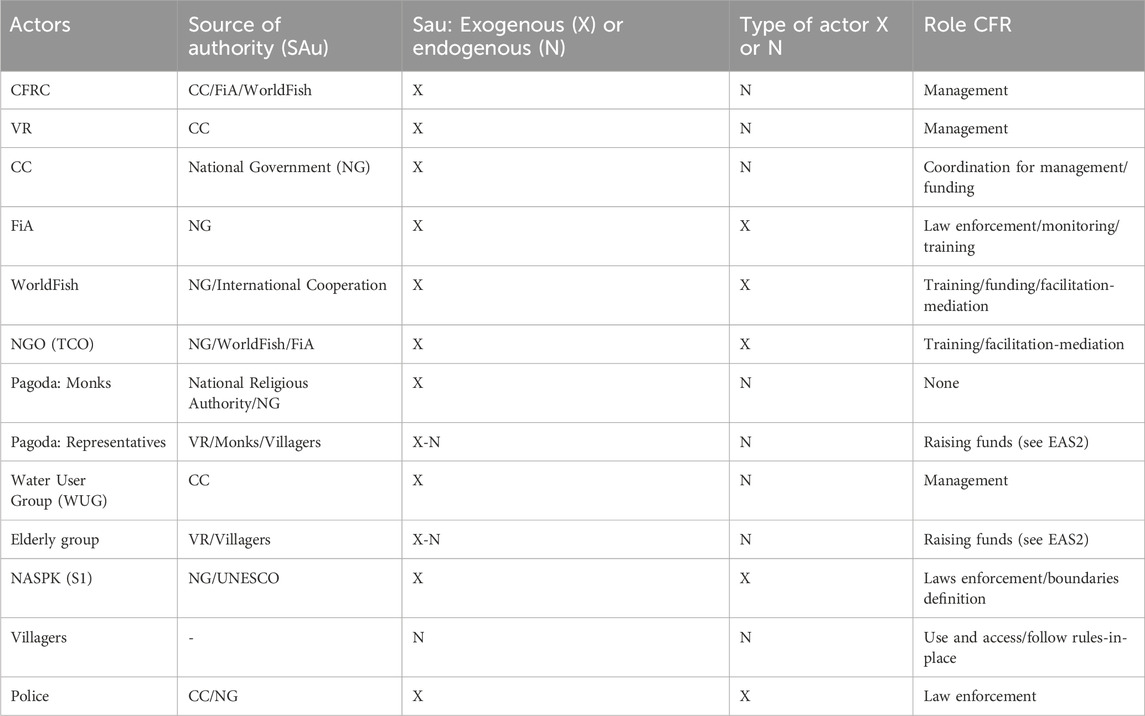

At the village level, key organizations at both sites during project implementation (2016–2021) included the Commune Council, the Village Representatives (VR), the Pagoda (comprising civilians and monks), the Elderly group, the Fisheries Administration Cantonment (FiA), WorldFish, and related local NGOs (Trailblazer Cambodia Organization–TCO). Additionally, in S1, other relevant entities include other religious institutions (Christian Church) and the National Authority for Sambor PreiKuk Temples (NASPK). WorldFish and the FiA were the lead implementing organizations, guiding the creation of the CFRs and the CFRCs working with local NGOs.

Each village has a chief and two deputies, and villages are clustered into communes administered by a CC. Since 1998, a CC has an elected commune chief as part of the Decentralization and Deconcentration (D&D) reform program (Eng and Ear, 2016). As Jack et al. (2021) indicate, in Cambodia village-level officials are typically not elected but consist of long-standing leaders and Cambodian war veterans. The village chiefs appoint other officials, including deputies, forming a governing group with recurrent family and kinship ties. Some relationships adopt a hierarchical “patron-client” structure, involving the exchange of gifts for loyalty, a common feature in the Cambodian governance landscape (Jack et al., 2021).

Village representatives are usually members of the CC, meaning that they are government employees who receive a government paid salary. At both sites, VRs have a central role for building the CFRCs, as they are CFRC members. Our selected sites belong to different Communes and, in both areas, the VR and CC are from the dominant Cambodian People’s Party (CPP). Given the power CCs wield over villages including as the conduit for much development finance, they represent highly contested political spaces. In S1, we learned that the original elected CC members belonged to an opposition party but were forced to resign to make way for CPP party supporters to fill the CC’s membership (former CC leader, 03 May 2023).

Appreciating the current political climate in Cambodia is key to understanding rural governance processes and actor’s positionality. Cambodia has experienced a gradual narrowing of space for political critical voices (Beban et al., 2019; Loughlin and Norén-Nilsson, 2021; Young, 2021). In rural areas, this phenomenon is evidenced by the control exerted through social media platforms, challenges encountered by independent journalism, and the issues facing critical media outlets over the years (Schoenberger et al., 2018; Beban et al., 2019). These power shifts in Cambodia have affected rural contexts by fragmenting rural villages as evidenced in S1 and explained later (Jack et al., 2021; Loughlin and Norén-Nilsson, 2021).

The study sites exhibit specific institutional arrangements (IA) that have the potential to shape the formulation of rules regarding the management of CPRs, none of which indicate CA related to CFRs. However, these are underlying agreements that exist in the study areas and shape social relationships, as discussed later. The IAs are:

• IA1. Election/selection arrangements: The election processes in the villages essentially amount to a selection organized by individuals in positions of power, resulting in office bearers being chosen from a familiar circle.

• IA2. Fundraising arrangements: Fundraising for collective activities involves collaboration between the elder’s group and the pagoda representatives group, with each group taking responsibility based on the specific activity. Both groups consist of trustworthy individuals, being recognized as a traditional organizations.

• IA3. Partisanship schemes: Control and political organization schemes, wherein teams affiliated with the dominant political party oversee specific numbers of families in each rural village. This is a form of political action that exists in rural areas. It ensures control of, and information about, what is happening in households.

• IA4. Collaborative arrangements: 1. Contributions for traditional Buddhist ceremonies arranged by the Pagoda, donations of private land for village road improvement or construction, and active involvement with financial support for village weddings and funerals are examples of voluntary acts within the community. 2. The practice of “provas dai” (labor exchange or ‘helping hand’), is a traditional practice rooted in principles of mutual help and reciprocity, where households collaborate to complete farming tasks (e.g., reciprocal ploughing, rice transplanting, and livestock rearing) (Lyne and Ngin, 2024).

Regarding AgBi, in S1, infrastructural changes are limited due to the historical significance of the area, originally part of the irrigation system for Sambor Preikuk temples (SPK) dating back to 600 AD. The recognition of the temples as a UNESCO heritage site in 2017 (UNESCO, 2017) altered possibilities for infrastructural changes. While soft interventions are allowed, hard construction, such as deepening the lake, was restricted due to its proximity to the UNESCO site, requiring permission from national authorities (WorldFish, 25 April 2023).

4.2 Agency capacity (AC)

4.2.1 Sense of authority (SA)

Social organization involves a hierarchical differentiation, where individuals in high positions are frequently connected to the State. Public speaking is limited among the general rural population, often characterized by a reluctance to express their opinions. Interviewees indicate that this is due to fear of failure, lack of education, social pressure, and cultural norms; moreover, this is accentuated within the older population (see EAS3 below). We find that this also reflects a fear of authority given the strong state influence at the commune and village levels. Village meetings predominantly occur at the village chief’s house. Typically, village representatives utilize communal loudspeakers to disseminate information verbally, which are also situated within the residences of the village chiefs. This centralization gives village chiefs significant control over dissemination of information and power within the social sphere (Jack et al., 2021). Furthermore, collected data indicates discontent in both areas concerning the unequal distribution of benefits by the authorities, emphasizing inequalities rooted in kinship groups or territorial locations within the villages (stakeholders, April to May 2023). However, this phenomenon is particularly pronounced in S1, where we were explicitly informed that individuals who lack financial resources or connections to influential figures are effectively excluded from leadership roles. This exclusionary practice acts as a deterrent against greater involvement in activities convened by these individuals (villager, 3 May 2023).

Regarding authority related to traditions we observed that monks and most elderly people, following Buddhist traditions, avoid discussing CFRs due to their association with ‘killing life,’ which conflicts with Buddhist principles (monk, 23 March 2023; Pagoda representative, 13 May 2023). This restriction may lead them to disengage from CFR-related processes, which could impact the project, given the Pagoda’s key role in social organization (Diepart and Sem, 2015). Additionally, collaborative actions, such as IA2 and IA4.1., are notably linked to the Pagoda.

According to WorldFish and TCO, securing the backing of the CC and state authorities is crucial for collaborative efforts in management and resource acquisition (project implementers, April 25 and 26, 2023). The CC serves as the gateway to villages, representing a source of their influence. While some view the State as a guardian, there is a contrasting perspective where people express mistrust and apathy toward the government, believing it may not be of significant assistance unless directly involved in their affairs. This sentiment was emphasized in an interview, stating, “Normally, people don’t trust or care much about what the government might do. Many people don’t think the government can help them, as long as our government doesn’t bother them.” (Scholar, 23 April 2023).

Table 2 shows the hierarchy of relationships based on the source of authority and the current role that these actors play in relation to the CFR. Additionally, we indicate whether the source of this authority is external or endogenous to understand where the agency of these actors originates and to illustrate the indirect influence on CFR management from higher levels of Cambodia’s decentralized governance system (Table 2).

4.2.1.1 Moral ecological rationalities

The lingering memories of conflicts from the 1970s to the 1990s (the Khmer Rouge period, the Cambodian-Vietnamese armed conflicts) impact older adults, deepening reliance on rituals and avoiding conflict with peers (Agger, 2015). As Lee (2021) indicates in a study of everyday peace in Cambodia, local peacebuilding efforts often manifest as seemingly insignificant and less visible actions, which may take the form of non-action or silence. The near extinction of Buddhism during the “Pol Pot years” further strengthens people’s support for the religion (Harris, 2013). Nowadays, Buddhism plays a profound role in community life, predominantly observed through festivals held in Pagodas. Older adults, particularly those adhering strictly to Buddhist principles, refrain from voicing views about village issues. Buddhism does however play a role in political life (Ledgerwood and Un, 2003; Kent, 2006). For instance, individuals in S1 avoid expressing grievances to the VR due to their commitment to Buddhist values and their proximity to the Pagoda (villager, 1 May 2023). These perspectives, intertwined with the ongoing political climate of 2024, contribute to the apparent acceptance of the status quo and the lack of social scrutiny toward CFR decisions.

In that context, actors at both sites report that illegal fishing and water pumping are often committed by middle-class individuals who disregard rules, despite being aware of them. Interviewees describe these individuals as “selfish” – focusing solely on their families and highlighting their disregard for environmental regulations. However, an interviewee indicated that if someone has a debt, they can repay it more quickly by engaging in illegal fishing than by pursuing other economic activities (villager, 3 May 2023).

4.2.2 Sense of functionality (SF)

Fishing, a culturally significant livelihood and recreational activity, holds importance in these communities. CFRs’ multifunctional nature necessitates tradeoffs between competing uses, e.g., managing water extraction by reducing the frequency of rice cultivation from twice to once during the dry season, which has led to some complaints questioning the new regulations (stakeholder, April 10 and 24, 2023). People who complained in S2, changed their productive orientation from rice cultivation to cashew cultivation, a crop that is less water intensive. Initially lacking the necessary skills for transitioning to a new crop, they made investments and acquired the required competencies in cashew production (villager, 28 April 2023).

Tradeoffs are more evident in S2, where economic diversification is lower. In S1, there is a gradual substitution of agricultural work, potentially diminishing the significance of the CFR. In S2, while some individuals depend solely on fishing for their livelihoods, it is a common activity for everyone during the rainy season. Further, the lake area was once a forest decades ago, and villagers now prefer its absence, as it facilitates fishing activities (villager, 7 April 2023).

In S1, access and use of space are restricted by external regulations related to construction in the area of the UNESCO site of SPK temples (NASPK, 2023), influencing people’s attitudes toward the area. Individuals expressed dissatisfaction with regulations impacting house constructions and seem to feel a lack of control over the territory they inhabit (villager, 2 May 2023). Moreover, some respondents maintain the belief that only individuals involved in tourism activities benefit from SPK, a perspective not supported by those allegedly engaged (villager, 3 May 2023; villager, 15 May 2023). This may cause some villagers to perceive the CFR as an unalterable space with limited immediate productive functionality, unless it involves tourist activities.

Another challenge related to the use and valuation of the resource is the presence of invasive aquatic plants with thorns that discourage access to the water body due to potential injury to the skin of fishers. This was mentioned by villagers at both sites. However, at S1, it was observed that this problem is significant as some people prefer to fish in neighboring water bodies rather than in the one surrounding the CFR. Interviewees stated that they cannot prevent the proliferation of this plant (villager, 2 May 2023).

4.2.3 Social differentiation (SD)

4.2.3.1 Multiple social identities

People at both sites perform multiple roles, such as the VRs who are also farmers. Nevertheless, there are dominant individual identities that position people in the social hierarchy. State representatives, including members of the CC and village representatives, often have multiple roles in managing the commons. For instance, at S2, VRs are both members of the CFR, members of the CC, and representatives of the WUG. At S1 one of the former CFR chiefs is the lead of the partisanship scheme (IA3), he identifies himself as a State-employee even when he does not receive a State salary (party group leader, 16 May 2023). We can see that political careers often lead to higher positions within the State, with potential kinship connections due to villages typically being run by one or a few families (Ovesen et al., 1996).

The majority of respondents primarily engage in agriculture, identifying themselves as farmers, while fishing serves as a secondary activity. Additionally, they have diverse occupations such as construction worker, seller, and teacher. People in the productive age group (15–64) are occupied with their jobs, hindering their involvement in positions that do not yield immediate income. Consequently, unpaid roles like CFR patrolling face challenges in attracting participants (villager, 28 March 2023; village guard, April 4 and 10, 2023).

4.2.3.2 Embodied relations and hierarchies

Our focus here centers on gender-based relationships. At both sites, finance positions were held by women, with the belief that women are better at financial management. In S1, the female CFR Cashier did not actually manage the money during her time in the CFR, further she indicated that she never saw any money during her tenure in the position (former Cashier, 15 May 2023). This could also indicate that she had a marginal position in the CFR structure. In S2, the female Cashier is also a member of the CC and gender-based violence prevention projects. Two out of nine members in S2 CFRC are women, the other woman being a sub-village head. In S1, only one out of nine CFRC members were women (Bylaws, 2019).

Traditional positions of power, comprising the Elderlies and the Pagoda representatives’ groups, are also mostly reserved for men, given that Cambodia could be considered a gerontocracy (Guérin, 2012). Moreover, the perception that patrolling is exclusively a male responsibility contributes to the association between men and CFRCs, as members engage in patrolling activities, often overlooking the participation of women. WorldFish project implementers, local NGOs, and FiA, further argue that women encounter challenges in taking on managerial roles attributed to poor family support and the burden of an excessive workload, both within and beyond the home (project implementers, April 25 and 26, 2023; State officer, 27 April 2023).

4.2.3.3 Individual and household assets

The primary crops at both locations consist of cashew and rice, with cultivation of cassava, watermelon, banana, and various fruits and vegetables on a smaller scale. Another reported activity involves selling wood from nearby forests. However, migration in both areas seem to be altering the agricultural orientation of the communities. Young adults migrate to work in factories (clothing, manufacturing, food) in Phnom Penh or Thailand or to engage in the construction and mining sectors (ILO, 2023).

In both areas, village chiefs refer to two poverty categories based on Sub-Decree 291, which defines very poor and poor individuals, both falling below the poverty line set by the World Bank (IDpoor program, 2024). At S1, 7.79% of people are classified as being under the poverty line, while in S2 it is 9.92% of the population (WorldFish, 2021a). Most families at both sites are medium-income, with a few high-income households. The description provided by village chiefs emphasizes that low-income individuals may have a house but lack animals or land for cultivation, or possess minimal land. This category includes divorced or widowed individuals who have lost their property and work for others, potentially leading them to migrate for employment, as well as individuals who are unable to work due to physical impairment. At S2, it is highlighted that, “the situation of poor people is not very bad because they have a home and also, they can go to the lake, so it’s not always necessary to buy food” (CFRC chief, 20 March 2023). This last sentence highlights the importance of fish conservation for low-income households’ livelihoods, for which the CFR might be an important asset. At S1, there is skepticism regarding the apparent affluence of certain households in the village, with some suggesting that they might represent “big houses, big debts” (villager, 2 May 2023).

Regarding other assets, literacy and education seems to play a protagonist role in social differentiation. Some people in S1 view education as crucial for attaining managerial roles and upward mobility (villager, 5 April 2023). Some associate fishing with economic constraints, expressing a preference for their children to focus on education and aspire to social mobility, reserving fishing for leisure activities (villager, 9 April 2023).

4.3 Arena of social interactions (ASI)

Actors of both sites consider CFR infrastructure as common property, considering themselves as its custodians for future generations. While villagers have ideas and aspirations, they rely on organizations like the CC or CFRC to initiate and propose collective activities. The CFRC, assumes a vital role in CFR management, serving as legitimate local actors.

WorldFish, local NGOs, and FiA serve as mediators in the process, bringing their distinct perspectives that influence the situation. The bylaws, initially established by FiA, undergo partial modification and amendments by local actors. FiA suggests that the CC and the CFRC have a degree of flexibility in adjusting these regulations (state official, 27 April 2023). While CFR members indicate that they adhere to external laws, they retain the authority to make alterations within certain parameters. Adjustments could be made concerning determining villagers’ financial contributions to the CFR and specifying permissible fishing techniques (CFRC representative, April 26 and 13 May 2023) (Bylaws, 2019). Planning, which was facilitated by WorldFish during the project implementation (2016–2021), was headed by the CC and CFRC, who established priorities and responsibilities for both biophysical and management needs, incorporating financial contributions from involved stakeholders (project implementer, 25 April 2023).

The everyday action situations (EAS) in place at both sites are as follows:

• EAS1. Illegal Fishing and Patrolling: An absence of regular patrolling in S1 since 2021 with unaccounted cases of illegal fishing. Concerns include suspicions of nighttime electric fishing and other unauthorized fishing by local residents. Dependence on external fund availability for patrolling is high, with a lack of transparency around how fines collected in the past were used. An interviewee who serves as a village guard tells us that people feel they cannot patrol if they lack the authority to do so, “they have no power and they have no salary” (villager, 3 May 2023). In S2, a patrolling scheme has existed since 2016, systematically addressing incidents due to organized patrolling and graded sanction system. Committee members, at times accompanied by village security personnel, conduct patrols. Additionally, one individual reports that he voluntarily undertakes pond patrolling, despite not holding a formal position within the Committee. This person stated that his family depended on the water body for their livelihood and that he regularly patrols the area when fishing and at other times (villager, 22 March 2023). Members of the CFR state that upon encountering individuals engaging in illegal fishing, their initial approach involves engaging in dialogue to explain the regulations. For repeat offenders, they proceed to confiscate their fishing gear and, if the behavior persists, they summon external authorities such as the FiA and the police (26 April 2023).

• EAS2. Funding and Contributions in-kind: At both sites, the Pagodas removed the CFR donation boxes due to financial accountability concerns. At S1 there is no internal funding mechanism. Neither the villagers nor the representatives contribute to the CFR. During the project duration, community participation primarily involved physical efforts or contributions in-kind. At S2, committee members contribute a portion of their state salary to the CFR. Although paused for the COVID-19 pandemic, there are voluntary contribution mechanisms from villages. These should be restarted. Furthermore, a common fund to initiate a loan scheme has been initiated, with interest directed toward the CFR and its integration with the irrigation system. An annual lake ceremony was also introduced as a fundraising opportunity within the S2 villages.

• EAS3. Information Sharing, Trainings, and Meetings: At both sites individuals receive information about regulations and the significance of conservation during general village meetings, extending beyond specific CFR focused sessions (mostly during 2016–2021). While the majority of respondents are cognizant of CFR rules, these meetings reflect an absence of discursive spaces, being primarily one-way communications, and poses a significant obstacle to fostering CA. This limitation not only impedes the potential for collective learning but also hinders the collaborative exploration of solutions. At both sites, the VRs use loudspeakers to disseminate community information, including CFR rules. In S2, the CFRC organizes meetings to share updates and progress related to pond management, which can serve as an important mechanism for transparency (villager, 22 March 2023). However, a local resident noted that while people do attend these meetings, they are often hesitant to speak up, as it might be perceived as trying to “stand out or appear above others” (villager, 28 April 2023).

• EAS4. Provisioning Actions: People at both sites emphasize the importance of caring for the waterbody and CFR. They also recall past activities conducted during the project’s implementation, such as habitat improvements for the waterbody and fish releases. In S1, there was cooperation among villagers when external funds and CFR leadership were available. For example, canals were opened to connect the water body of the CFR to the main road (village representative, 01 May 2023). However, in its absence, there is a lack of endogenous CAs for CFR sustainment, despite conceptualized ideas for potential improvements. At S2, collective activities are organized by CC and CFRC to specifically address infrastructure damage, such as to water culverts. This requires the use of CFR funds and contributions from other organizations to repair damaged items (CC representative, 23 May 2023). In S1, the lack of pond maintenance is particularly indicative of the absence of endogenous collective action.

• EAS5. Appropriation and Access: At both sites, fishing serves as a supplementary activity, contributing to food provision (see SF). The peak fishing season, occurring during the rainy season (May - October), triggers changes in access and usage rules due to the dynamic nature of the resource. During this period, fish migrate to the rice fields and the water bodies undergo significant changes due to flooding. While fishing activities are taking place in all water bodies, the patrolling team becomes inactive as conservation enforcement is prioritized during the dry season. At S1, the nearest village is responsible for managing, accessing, using, and is considered the owner of the lake housing the CFR. Access by individuals from neighboring villages is prohibited, though occasional instances may occur without clear sanctions. At S2, the five neighboring villages collectively manage, access, and use the lake’s resources, considering it common property. Beyond the five principal villages, occasional fishing by individuals from other villages is also permitted. Since the creation of the CFR, the CC and the CFRC have adapted the bylaws by adjusting the size of the protected area and the amount of money that CFRC members must contribute. It was pointed out to us that “the regulations are made according to the problems of the people, not only considering the bylaws” (CC representative, 13 May 2023).

• EAS6. Competition for resources: At both sites, the water body is currently used for crop irrigation once during the dry season. This represents a shift from using it twice to once during the dry season due to adjustments for CFR conservation efforts; this caused discrepancies at both sites. S1 reports a lesser degree of control in managing water usage compared to S2. As S2 has more patrol activities, they are also aware of the illegal use of resources, which leads to an increase in reported cases of non-compliance and a stronger impetus to respond to it.

• EAS7. Perceiving Biophysical Changes: At both sites, villagers perceive improvements in the water bodies. They observe increased fish populations and express aspirations to conserve and enhance aquatic diversity.

4.4 Resulting governance arrangements (RGA)

As a result of the ASI, we have CFRCs at both sites, with different management results but shared commonalities in terms of how governance and CA happens.

In S1, there is no endogenous motivation for CFR elections; instead, people reported waiting for an external authority to take responsibility. In the case of S2, elections are organized by the CC together with the FiA, but there is no grassroots motivation for CFRC elections. This is in a context where decision-making in rural Khmer communities typically takes place at the household level. Both Diepart and Sem (2015), Ovesen et al. (1996) found in their research that commons management in these communities is predominantly shaped by decisions made at the household level, rather than by community-based organizations.

Considering the CFRC characteristics in S1, we identify an inactive committee with disconnected responsibilities. Given that No new elections occurred and old CFRC members lack clear responsibilities. Some individuals, even when identified as responsible by others, deny their management roles and prefer disengagement. Changes in committee members during 2016–2021 left some positions vacant (e.g., Cashier), contributing to a disconnect in the management processes.

In the case of S2, there is an active committee with defined responsibilities. Despite the absence of new elections, CFRC members assume and fulfill their defined responsibilities, anticipating upcoming elections with FiA support. They actively contribute funds to the CFR from their state-salaries, participate in patrolling duties, and hold dual roles as members of both the CFRC and CC.

Features of governance derived from the ASI, are discussed in the following section.

5 Discussions

5.1 Design principles

Ostrom points out that, when analyzing cases of failed CA, “the lack of capacity to achieve self-governance appears to stem from internal factors related to the situation of the farmers and external factors related to the regime structure under which they live” (Ostrom, 1990). This phrase resonates here, given that we analyze the structural characteristics of Cambodia’s decentralized governance, and a constrained individual agency hinder more than motivate CA. We use these principles as evaluative criteria to understand the outcomes of the CFR implementation process in terms of the existence and effectiveness of CA. The elements of our conceptual framework discussed are identified by acronyms in parentheses.

5.1.1 Clearly defined boundaries

The households authorized to take resources from the CFRs and the system boundaries are clearly defined at both sites; however, these can be interpreted in a flexible manner. The entry rules for becoming a resource appropriator are determined by the location of the households within the village or villages closest to the CFR. There is a finite list of villages that share each CFR as a CPR; villagers can specify which villages are included and which are excluded. The appropriators identify people who should not be appropriating the resource by fishing in their CPR because there is a clear understanding of which villages are included as appropriators. However, it is noted that people are usually identified as illegal not because of the activity of fishing in someone else’s CPR, but rather because they employ prohibited fishing practices (EAS1). Instead of seeing the boundaries as not clearly defined, we see this as an example of their flexibility for two reasons: 1) during the rainy season, due to the nature of the resource (fish migrate everywhere), people can fish in any water body while, at the same time, the enforcement of regulations, including patrols, are loosened. 2) It is part of traditional practices. In the past there were no restrictions on which CPR belonged to whom. There is a practice of self-selection based on the proximity of water bodies to households. However, this does not restrict people’s freedom of movement, as they still go fishing in other places (SF, EA5).

5.1.2 Congruence between appropriation and provisioning rules and local conditions

In general, the CFR system is appropriate to local ecological conditions. However, in order for the CFR to fulfill its function as a refuge during the dry season, adjustments are needed in terms of water use, based on a shift in the rice cultivation cycle from twice a year to once a year during the dry season (SF). This shift requires some cultivators to shift production from rice to less water-intensive crops, such as cashew, which is not feasible in the short term and, thus, is a significant challenge that needs addressing. Although the amount of water that must remain in the CFR is clear to resource users (water marker pole, see Figure 1), the rules must be strengthened. This inconsistency led to a conflict between the objectives of cultivation and fish conservation in both zones during the early stages of the project.

At S1, perceptions of CFR utility are also influenced by the rules imposed by UNESCO that restrict infrastructural change (SF) to increase the CFR’s services by deepening the pond (ESC, SA). Furthermore, the presence of skin-damaging aquatic plants is an additional disincentive for people to engage in ecosystem maintenance (SF). At S2, although changes in crop cycles were also required, it appears that the greater agricultural orientation of the area makes the water body more important for its economic purposes.

5.1.3 Collective-choice arrangements

There is a gap between constitutional arrangements and operational arrangements (McGinnis, 2011). Constitutional arrangements exist in the form of national laws on fisheries and defined legal requirements for CFRCs to operate (e.g., development of bylaws, creation of committees) as well as operational arrangements such as patrol shifts (S2), graduated sanction systems (S2), and boundaries on who are appropriators (S1 and S2). At S2, whilst local stakeholders in theory have greater autonomy over decisions such as CFRC membership, stakeholder contributions to the CFRC, fishing methods, the balance between water used for fish and irrigation, as well as who is or is not a resource appropriator (EAS5), these decisions also appear to have been made by a narrow group of actors who mostly derive authority from being State and village representatives appointed through a top-down political process. Further, no space for collective choice arrangements emerged following the creation of CFRC–given the ‘closed door’ nature of CFRC operations, characterized by an absence of discursive meetings with its larger constituency of CFR users and the seemingly one-way communication from CFRC to its constituency on the importance of the CFR system. Thus, this approach does little to inspire the broader population of villagers to see CFR management as a shared responsibility or to engage the diversity of opinions and ideas to inform decisions and solutions to problems (EAS3). Consequently, rule compliance depends on awareness-raising processes channeled through elites holding positions of power within the local government structure (CR, CC members) and external agents. WorldFish and local NGOs play a protagonist role in mediating and facilitating the implementation of CFRs, working closely with the CFRC (M, ASI).

One positive development in 2016, at both study sites, was the adjustment of rules pertaining to fishing gear and economic contributions in the bylaws to respond to local realities, thereby legitimizing local specificities within the broader frame of national law (ASI). This process of rethinking and reframing the bylaws is no longer existent at S1, while it continues at S2 through the redefinition of norms (EAS5) and through planning related to the water body (EAS4). Nevertheless, the fact that such decisions in S2 are made by the CFRC in the absence of discussions with the broader CFR stakeholders does not represent collective choice arrangements. Instead, that the current CFRCs are more akin to power-centralized institutions In fact, the CFRC’s selection process - instead of election (IA1, RGA) - perpetuates the power of a few individuals by adopting historically entrenched selection processes and partisanship schemes (IA1, IA3), leading to discontent among those who are unable to assume leadership positions, or simply to have a voice in village issues (SA). This last point is prominent at S1, where we note a greater reluctance to take part in collective discussions and a heightened awareness of the non-existence of possibilities for change (SA).

5.1.4 Monitoring system

Ostrom suggests that ideally the person monitoring should also be a resource appropriator to ensure a strong incentive to enforce rules (Ostrom, 1990). Yet, findings from both case study sites suggest it is not so straightforward. At S1, for instance, simply being a resource appropriator without real power to make interventions has proven to be insufficient, whilst self-interest without financial compensation also appears to be a problem for sustained monitoring (EAS1). At S2, it is observed that those with power within the CFR assume this role. The role is also performed by others who depend on the CFR and who join on a voluntary basis (EAS1). Yet, illegal fishing exists even where the need for authority is fulfilled. We propose that this is rooted in the CFRs’ value being limited to only some households given the diversification of household livelihoods options whereby the CFR is not a primary resource for livelihoods for the majority of households, as it is in S1 (SF). With Cambodia’s rural economy transforming through greater proximity to the market economy and off-farm and off-village livelihoods options expanding with improved communication, broader social networks, and transport, the livelihood strategies of households are continuously.

5.1.5 Graduated sanctions

Graduated sanctions occur when deterrence increases with each violation committed by the same person. Although there is a system of graduated sanctions in S2, there is a role for external authorities to reinforce compliance in cases of repeat offending (EAS1). The initial warning and the reluctance to escalate the sanction may also occur because people may initially opt for a status quo (SA) to maintain peace.

The reputation of local leaders and the dynamism of organizations play an essential role in sensitization and compliance processes (B, EAS). At S1, where institutions are more fragile and CFR CFRC actions and accountability are unclear (RGA), compliance is almost non-existent. At S2, there is greater resilience of the CFRC, represented by the continuity in the existence of this organization.

5.1.6 Conflict resolution mechanisms

At both study sites, it is observed that the CFRC is an unlikely arena for identifying and resolving conflict: first because of the lack of regular interaction between the CFRC and broader CFR stakeholder constituency (villagers/beneficiaries), and the consequent lack of agency villagers perceive in relation to CFR management (SA). The lack of dynamism within the CFRCs, as the Arenas of Social Interaction (ASI) in relation to CFR management, fails to engage active dialog involving the broader CFR beneficiaries (EAS3) where open discussion occurs. Where conflict resolution entails confronting local elites, the potentially high social and political costs act as a further deterrent to surfacing conflicts. Nevertheless, the authors recognize that some arenas or mechanisms for conflict resolution may not be apparent to external observers (Lee, 2021), given the limited time spent in these two locations.

5.1.7 Minimal recognition of rights to organize

CCs may delegate or appoint members to the CFRC. This is indicated as a common practice in public administration to ensure suitable representation. The appointment could guarantee that those who are able to engage with other stakeholders (SA) are elected, a quality that is highly important for resource mobilization and prioritization of the CFRC on the public agenda. However, allowing selected groups to manage the common pool resources (CPRs) can result in the constant marginalization of already excluded groups, perpetuating their social marginalization. Yet, popular elections do not seem to be considered when filling such positions. Local representative election mechanisms are either non-existent or exist in a very weak form, limited to specific instances such as CC elections and national elections. It can be argued that the electoral mechanism is based on Western democratic ideals, which may differ from an Asian model (Ho, 2023). However, we believe that a representative CFRC could increase the legitimacy of the leaders and villagers who vote, giving them a stronger voice in the public sphere.

5.1.8 Nested enterprises

Since this study focuses on local management dynamics, we did not examine other CFR management layers. However, evaluating these layers is vital for future research, as stakeholder cooperation is key for supporting CFR initiatives.

5.2 Bricolaged processes in place: Merged organizations and roles

Institutional bricolage processes play a crucial role in the articulation of institutions for managing the CFR. The fact that the state assumes functions for sustainability transitions (Silvester and Fisker, 2023) also implies that when the state acts, it is not the action of a single entity, but rather an event involving intertwined practices performed by different actors within the state apparatus. In this sense, the actions of the CFRCs are part of both the villagers in power (VR) and State actors; the CFRCs ultimately become the State’s final point of contact in the villages for fisheries management. By taking on resource management roles, these responsibilities are also institutionalized as State responsibilities. Thus, the CFRC responds to the logic of the State as it is currently conceptualized. An interesting example within this re-creation of the State is the payments that CFRC members make to contribute to the CFRC fund by paying a portion of their salary (EAS2). In this respect, we see how top-down systems merge with communal practices of contributing money to shared CPRs. Thus, when CFRC individuals contribute financially to this new CPR, they do so on the basis of accepted practices of engagement with the state, rooted in patronage networks of instrumental payments and favors (Scott, 1972).