95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 30 July 2024

Sec. Environmental Economics and Management

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2024.1396687

This article is part of the Research Topic Green Finance & Carbon Neutrality: Strategies and Policies for a Sustainable Future View all 36 articles

The 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference, held in the United Arab Emirates at the end of November 2023, stated that climate action cannot be delayed and the financing and investment situation for adapting to climate change needs a qualitative leap. Vigorously developing green finance is one of the important ways to achieve this goal. The core question of this paper is: Can green finance policies promote enterprises’ environmental investment? This article uses the formal implementation of the “Green Credit Guidelines” in 2012 as a quasi-natural experiment, bases on the micro data of A-share listed companies from 2004 to 2020, and adopts the difference-indifferences propensity score matching method (PSM-DID) to explore the role of green credit policy in guiding corporate environmental protection investment from multiple dimensions. The research shows that the implementation of the “Green Credit Guidelines” has promoted corporate environmental protection investment to a certain extent, and the conclusion still holds after a series of robustness tests. Heterogeneity tests found that the impact of green credit policy on corporate environmental protection investment varies significantly among different ownership enterprises and enterprises in different regions. Further research shows that the Green Credit Guidelines are regulated by macro and meso factors. From the perspective of mechanism, this paper finds out the mechanism of promoting enterprises’ environmental protection investment at the micro level. At the macro level, economic policy uncertainty and monetary policy tightening affect the degree of corporate environmental protection investment. At the meso level, the government’s attention to environmental protection determines the behavior of local enterprises, which in turn affects the attitude of enterprises towards environmental protection investment activities. At the micro level, the implementation of green credit on the one hand exacerbates the problem of corporate financing constraints, making companies have incentives to invest in environmental protection to alleviate this problem. On the other hand, it will also promote changes in innovation and capital factors in enterprises, directly increasing corporate environmental protection investment. This paper is helpful for the theoretical circle and management departments, so as to provide reference for the government to issue relevant policies.

At present, the global extreme weather is frequent, the conflicts caused by energy crisis are increasing, and the environmental problems are increasingly prominent, as a result, the demand for sustainable development is pushed to a new peak again and again, and the green action is urgent.

Commercial and industrial activities are one of the main factors causing environmental degradation (Agliardi et al., 2017). As an influential presence in daily life, enterprises bear significant social responsibility. Environmental investment is the most direct manifestation of corporate environmental management activities. However, environmental investment itself has certain particularities. It has strong externalities and usually involves large investment scales and long return cycles. Therefore, it requires the dual effects of external factors such as relevant government policies and internal factors such as corporate social responsibility to promote enterprises to carry out environmental investment activities (Zhang et al., 2021).

Due to the strong leverage of banks, it is not uncommon to see that investment through banks to promote enterprises to adopt more environmentally friendly and sustainable development strategies (Sun et al., 2019). As early as 1974, the Federal Republic of Germany established the world’s first policy-based environmental protection bank, which specialized in providing preferential loans for environmental projects that were not accepted by general banks (Stoeppler et al., 1984). Subsequently, the Superfund Act, the Equator Principles, and the Environmental Responsibility Economic Alliance were introduced and established, effectively promoting the sustainable development of economic sectors (Munitlak-Ivanović et al., 2017).

As the largest developing country and a responsible major country, China has been actively participating in global climate governance and environmental governance (Wu et al., 2016). In the 2022 Global Green Finance Development Index ranking, China is the only developing country among the top 10 countries in terms of green loan balance. By the end of the third quarter of 2023, China has become the world’s largest green credit market and the second largest green bond market.

Without the strong support and promotion of the government, China’s green finance would not have made such great progress and achievements. Green credit was first proposed in China in 2007, and since then, China’s green credit has experienced rapid development and policy improvement. The “Green Credit Guidelines” issued in 2012 further elevated green credit to the level of corporate strategy. At present, scholars’ researches on green credit policies(GCP) mostly focus on the impact on corporate green innovation (Hu et al., 2021), corporate performance (Yao et al., 2021), corporate structure upgrading (Wen et al., 2021), etc. There are few papers studying the relationship between GCP and enterprises’ environmental protection investment, and most of the relevant papers take environmental protection investment as an intermediary variable to study the impact of GCP on other variables. For example, L. Ji et al. (2021) discussed the impact of GCP on the implementation of GCP. Whether the environmental protection investment of heavy polluting enterprises is conducive to promoting their debt financing. Few scholars have studied the direct causal relationship between GCP and environmental protection investment, and the discussion on the mechanism of action is not comprehensive, without taking into account the influencing factors at all levels. However, adequate investment in environmental protection is a necessary path for the green transformation of enterprises. Previous studies have theoretically demonstrated the path of mandatory environmental policies on enterprises’ green innovation, environmental protection investment and green transformation, but there are no relevant studies to analyze whether market-based and guiding environmental policies can affect enterprises’ environmental protection investment and what their impact path is. Therefore, the important question of the existing research is: Can the Green Credit Guidelines really play the guiding role of banks in capital allocation and promote enterprises’ environmental investment?

Analyzing the role of guided environmental policies at the enterprise level can accurately evaluate the policy effect and better analyze the policy path. The purpose of this paper is: Can the Green Credit Directive promote enterprises’ environmental investment, and what are the influencing factors? Based on this, this article constructs a quasi-natural experiment using the Green Credit Guidelines (hereinafter referred to as GCG) promulgated in 2012, takes China’s A-share listed companies from 2004 to 2020 as the research object and use the PSM-DID method to evaluate the impact of green credit on corporate environmental protection investment and its mechanism of action, and study the mediating role of financing constraints and factor substitution effects. Compared to existing study, the possible research contributions of this article are: firstly, studying the relationship between green credit and corporate environmental protection investment provides empirical evidence for green financial policies to promote sustainable development of enterprises, helps to fully understand the policy effects of green credit, and also makes up for the relative scarcity of literature in this field. Second, it reveals the regulatory factors of green credit on enterprises’ environmental protection investment from the macro and medium levels, analyzes the impact mechanism of green credit policy on enterprises’ environmental protection investment from the micro perspective, and considers the influence factors of green credit policy at different levels more comprehensively, which helps to open the black box of green credit affecting enterprises’ behavior. It expands the influence link of policy affecting enterprise behavior, and provides ideas and empirical evidence support for policy making of relevant departments and institutions at all levels. Thirdly, studying China’s green finance can provide reference and ideas for financial policy reform and institutional development in other emerging developing countries. We built the theoretical framework shown in Figure 1 as a visual presentation of the article.

The remaining parts of this article are arranged as follows: the second part details the theoretical mechanism of the green credit policy’s impact on corporate environmental investment and proposes research hypotheses; the third part is the research design; the fourth part is data description and benchmark regression results and analysis; the fifth part further studies the other factors of green credit policy affecting enterprises’ environmental protection investment; and the last part is conclusions and implications.

Since the reform and opening up, China’s economy has developed rapidly, and China has become the world’s second largest economy. However, behind the economic development is an increasingly severe ecological environment problem. In the early stages of reform and opening up, due to the backward technology level and unsound industrial system, China adopted an extensive economic development model of “high investment, high consumption, high pollution, low efficiency”, which seriously affected the ecological environment. In the late 1990s, Chinese enterprises began to participate in the global economic division of labor on a large scale, undertaking a large number of high-polluting and high-energy-consuming industries transferred from developed regions, leading to more serious environmental pollution and ecological degradation (Chan and Yao, 2008). In the new century, China rises as a “world factory”, while behind this economic miracle is the blowout development of low value-added, high energy-consuming and high-polluting industries and the surge in population further deepens people’s destruction of the ecological environment and their demand for the environment.

Faced with the continuously severe ecological environment situation, although the country has implemented certain environmental governance measures and thus improved the ecological environment in some areas, the overall situation is still deteriorating. The governance capacity is far behind the speed of destruction, resulting in a gradual expansion of ecological deficit. In addition, there are also many problems in China’s environmental policies for local industries, which have led to the failure of the policy to achieve its expected results.

In recent years, the increasing natural problems caused by environmental degradation have made the society’s demand for high-quality development stronger. All development is based on economic foundation, so is environmental governance. The funds needed for implementing environmental governance and green product projects can be obtained through green finance channels (Ng, 2018). Green finance mainly uses financial instruments as leverage to promote the development of environmental protection industry, green upgrade of traditional industries, and ecological environment protection projects to obtain financial support (Hemanand et al., 2022). The destructive development in the past decades has made many sicknesses of heavy pollution industries entrenched. Therefore, in addition to hard environmental policies, some guiding policies are also needed to promote the green development of industries. In order to implement the sustainable development strategy, the Chinese government has also issued a series of green finance policies.

The beginning of China’s green finance policy can be traced back to the “Decision of the State Council on Strengthening Environmental Protection Work during the Period of National Economic Adjustment”, which was issued in 1981. From this point until 2012, it was the initial stage of the development of China’s green finance policy. During this stage, China mainly adjusted the industrial structure and strengthened environmental protection through the issuance of “differentiated” credit policies (Zhang et al., 2021). In 1995, after the People’s Bank of China established the “Notice on Issues Related to Implementing Credit Policies and Strengthening Environmental Protection Work”, some domestic commercial banks began to issue green credits, and China’s green finance system was officially born. The “Notice on Continuing to Deepen the Implementation of National Macro-control Measures to Effectively Strengthen Credit Management” issued in 2006 increased the difficulty for high-polluting and high-energy-consuming enterprises to obtain credit funds. The “Notice on Preventing and Controlling Loan Risks in High-energy-consuming and High-polluting Industries” issued in 2007 more strictly controlled the issuance of loans for high-polluting and high-energy-consuming projects. In 2012, the GCG issued by the CBRC promoted green credit from three aspects. First, the GCG requires banking financial institutions to promote green credit from a strategic height and increase support for green economy, low-carbon economy, and circular economy. Second, the GCG requires financial institutions to prevent environmental and social risks involved in credit business. Third, the GCG guides more credit resources to flow to green areas through adjusting the flow of bank credit funds and significantly reducing capital investment in high-energy-consuming enterprises (Wang et al., 2020). The promulgation of the GCG marks the rapid development stage of China’s green finance policy.

Whether the green credit policy can effectively and accurately promote the green transformation of enterprises is the core issue in evaluating the effectiveness of the policy. Scholars have found that the green credit policy has significant financing punishment effects, which inhibit the new investment of heavily polluting enterprises, reduce the performance of enterprises in heavily polluting industries, and reduce the proportion of long-term debt of heavily polluting enterprises, affecting the scale and efficiency of investment (Wang et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2021). This shows that the implementation of GCG has led commercial banks to impose green credit constraints on heavy polluting enterprises. In the face of this negative externality, what measures will enterprises adopt? Existing studies on the effects of GCP mainly include two parts: some scholars believe that GCP can only promote industrial cleanliness. Due to the increased financing constraints of heavy polluting enterprises, the development of heavy polluting enterprises is inhibited (Yao et al., 2021). Another scholar found that GCP can force heavily polluting enterprises to carry out green transformation by reducing the level of long-term debt financing and increasing financing costs (Liu et al., 2019). Zhu et al. (2022) found the “guiding effect” of green credit policy on enterprise capital investment, that is, green credit can help improve the level of green transformation investment of heavily polluting enterprises. Therefore, after realizing the difficulties faced, heavy polluting enterprises will have the motivation to increase green investment and accelerate the process of green transformation, so that their own behavior and national policy trends are consistent, in order to avoid strict environmental regulation by the government.

The implementation of green credit policy is not completely harmful to heavily polluting enterprises. Some scholars have found that although the green credit policy restricts the financing costs of heavily polluting enterprises in terms of credit scale and interest rate, the increase in financing constraints is conducive to promoting enterprises to carry out technological upgrading in order to reduce compliance costs (Liu et al., 2019). Besides, corporate environmental protection investment can provide necessary financial support for corporate green innovation, thereby promoting enterprises to carry out green innovation activities (Zhang et al., 2020). In addition, the introduction of the green credit policy also implies the demand for green products in the corporate market, as a result, heavily polluting enterprises will promote the production of green products through environmental protection investment in order to occupy a larger market share.

Regarding the influencing factors of corporate environmental investment, scholars have pointed out that the external institutional environment will affect the environmental investment behavior of enterprises, and the greater the government intervention and the higher the legitimacy requirements of the social environment, the greater the environmental investment of enterprises (Huang and Sternquist, 2007). At the same time, the implementation of green credit policy makes the government and society pay attention to sustainable development and the depth of the concept of green development, stimulating the social responsibility of enterprises and then making investment behaviors in line with green standards.

Based on the above analysis, this article proposes:

Hypothesis 1. The implementation of green credit policy can promote enterprises’ environmental protection investment.

The common explanation for economic policy uncertainty is that it is difficult to form a definite policy expectation because the government has not clarified whether, when, and how to change the current policy (Le and Zak, 2006; Gulen and Ion, 2016). Economic policy uncertainty may lead companies to be unable to make clear decisions in such unpredictable circumstances, which in turn can have serious consequences for the company. Therefore, in today’s era of global uncertainty, policymakers and corporate executives are highly concerned about it.

There are different views among scholars on the relationship between economic policy uncertainty and corporate investment. Vural-Yavas (2020) believed that during periods of high economic uncertainty, corporate managers would be more risk-averse and therefore avoid new investment projects. In addition, as uncertainty increases, the probability of corporate default also increases, resulting in increased debt financing costs. Therefore, when uncertainty is strong, banks may propose higher interest rates (Hong and Quang, 2023), which will have a negative impact on investment activities. However, some scholars believe that uncertainty can have a positive impact on corporate investment. Kulatilaka and Perotti (1998) believed that uncertainty in the external environment can bring new potential development space for enterprises. The greater the potential development space is and the fiercer the market competition is, the more investment opportunities there are. This is consistent with the growth option theory (Bloom N, 2014) and the Oi-Hartman-Abel effect (Oi, 1962; Hartman, 1972; Abel, 1983), which believe that increased uncertainty can increase the size of potential project returns and thus increase corporate investment.

As part of corporate investment, environmental protection investment is also affected by economic policy uncertainty. In periods of high uncertainty, the macro environment is not optimistic. At this time, heavily polluting enterprises that are subject to credit constraints will face more difficult conditions for survival. In order to seek their own long-term development, heavily polluting enterprises have to make changes and take actions to comply with the overall sustainable development of society, which means the demand for long-term development will force these enterprises to invest in environmental protection.

Based on the above analysis, this article proposes:

Hypothesis 2. Economic policy uncertainty positively regulates the promotion effect of green credit policy on corporate environmental protection investment.

In China, the government is centralized and powerful, and the People’s Bank of China, as the country’s central bank, is directly under the State Council and occupies an important position in the national administrative system. Therefore, the monetary policy implemented by the central bank has a great influence. As an important economic policy of the country, monetary policy’s impact on corporate investment behavior is also one of the core issues for scholars to explore the effectiveness of macroeconomic regulation. In response to this issue, scholars mainly conduct research from two aspects: laying economic foundation and alleviating financing constraints.

On the one hand, when the monetary policy environment is loose, companies tend to seize this opportunity and increase their financial asset reserves in a timely manner (Baumc et al., 2009), which lays an economic foundation for companies to invest in environmental protection. On the other hand, loose monetary policy can effectively reduce the cost of corporate loans by increasing the overall supply of funds in society, which can alleviate the problem of financing constraints to a certain extent (Morgan, 1998). The alleviation of financing constraints will promote companies to reduce cash holdings, expand investment (Kirch et al., 2019), and reduce the cost of environmental protection investment.

Based on the above analysis, this article proposes:

Hypothesis 3. Loose monetary policy positively regulates the promotion effect of green credit policy on enterprises’ environmental protection investment.

As the middleman between national policies and enterprises, local governments play a “connecting link” role. In particular, in China’s unique central-local structural relationship, the dynamic role of local governments is extremely important (Xu et al., 2009). On the one hand, local governments need to implement and carry out the macro policies issued by the state; on the other hand, the reflection and attention of local governments on policies will directly affect the behavior and attitude of enterprises.

The same is true for environmental issues. However, few scholars have conducted research on the relationship between government environmental concerns and corporate behavior. In China’s current national conditions and institutional environment, the degree of government attention to the environment can directly affect corporate environmental governance investment decisions through the capital market (Rowe et al., 2010).

If local governments pay high attention to the environment, they will put pressure on heavily polluting enterprises, strictly control their pollutant emissions, and use incentives and constraints to make enterprises meet environmental compliance standards. This process is conducive to promoting the generation of environmental investment behaviors such as replacing fixed equipment and technological upgrading. If local governments pay less attention to the environment, they will not take too many environmental protection measures. In the absence of government pressure, punitive measures, and incentives, enterprises are more inclined to maintain their original production behavior, so there will not be many environmental investment behaviors.

Based on the above analysis, this article proposes:

Hypothesis 4. The government’s environmental concerns will positively regulate the promotion effect of green credit on corporate environmental protection investment.

Allen (2005) found that in China, due to the dominant position of the banking system in the financial system, the financial model is dominated by credit, which makes bank credit determine the intensity of financing constraints (Brandt and Li, 2003).

Regarding the green credit policy and financing constraints, a large number of scholars have conducted research and reached a consensus. On the one hand, the implementation of the green credit policy has increased the difficulty for heavily polluting enterprises to obtain credit funds (Yao et al., 2021), which has exacerbated their financing constraints. On the other hand, credit regulations have a financing penalty effect (Peng et al., 2021), which restricts the investment and financing capabilities of heavily polluting enterprises (Fan et al., 2021), reduces the financing channels of enterprises (Hu et al., 2019), and these restrictions make heavily polluting enterprises unable to provide sufficient funds for investment, which inhibits their investment level. Environmental protection investment, as a unique investment, pursues comprehensive benefits including environmental, social, and economic benefits (Мельниченко et al., 2014). Therefore, under the condition of limited funds, financing constraints will reduce the environmental protection investment of enterprises.

Based on this, this article proposes:

Hypothesis 5. The green credit policy has an impact on corporate environmental investment through financing constraints, and the higher the degree of financing constraints, the weaker the positive effect of green credit on corporate environmental investment.

The factor substitution effect in the enterprise refers to the process in which the proportion of a certain production factor rises and gradually replaces other production factors. In this article, the factor substitution effect mainly refers to the implementation of GCG, which promotes the substitution of innovative factors for traditional inefficient capital factors.

GCG clearly require financial institutions to prioritize environmental compliance enterprises when allocating credit funds, which increases the difficulty of borrowing and financing for heavily polluting enterprises. If enterprises want to ensure long-term development under restrictive conditions, they must make a “clean” transformation (Wang et al., 2022), which will prompt enterprises with different pollution levels to make differentiated innovation investment choices.

Green credit policy is essentially a supplement to traditional environmental regulation policies. Therefore, most existing literature analyzes its green innovation effect based on the Porter hypothesis (1995). Scholars have found that the implementation of green credit significantly increases the innovation output of heavily polluting enterprises (Liu et al., 2021) and the output of green technological innovation (Gao et al., 2022). It can positively affect corporate green innovation by internalizing “environmental externalities” (G. Amacher et al., 2004).

The construction of green innovation projects is beneficial for heavily polluting enterprises to replace their existing inefficient and highly polluting facilities, equipment, and technologies. However, the development of green innovation cannot be separated from the role of investment. That is to say, changes in innovation factors drive changes in capital factors.

Based on this, this article proposes:

Hypothesis 6. The implementation of GCP can promote corporate environmental investment through factor substitution effects.

This article selects A-share listed companies from 2004 to 2020 as the research sample, with relevant data from the CSMAR database. The sample is classified into heavy pollution (experimental group) and non-heavy pollution (control group) industries.

In order to ensure the rationality of the sample, this article processed the original data according to the following three steps: ① removing all listed companies with “ST” and "*ST” in their stock abbreviations; ② removing companies in the financial and real estate industries; ③ removing severely missing data. After the above processing, the final sample included 531 listed companies, with 1,011 samples in the experimental group and 619 samples in the control group, with a total of 1,630 observations.

Corporate environmental investment (lnEEPI). In this article, the data on corporate environmental protection investment in 2017 and earlier years is replaced by sewage charges, while the data in 2018 and later years is replaced by environmental protection taxes. The two parts of the data are combined to form the data on corporate environmental protection investment.

The difference-in-differences variable DID (treated*time). Among them, treated is a group dummy variable, with a value of 1 for the experimental group and a value of 0 for the control group. Time is a time dummy variable, with a value of 1 for years from 2012 onwards and a value of 0 otherwise.

① Enterprise size (lnsize). Generally speaking, larger enterprises will pay more attention to green development for their own sustainability, thereby increasing their environmental protection investment. This article uses the logarithm of a company’s total assets at the end of the year to measure the size of the enterprise. ② Enterprise age (lnage). Enterprise age represents the maturity of an enterprise. Generally, the higher the maturity of an enterprise, the more capable and energetic it is to make new investments, such as environmental protection investments. ③ Total operating revenue (lngrevenue). Total operating revenue is one of the important measures of a company’s “blood-making ability”. It is generally believed that the higher the total operating revenue, the stronger the willingness to invest. ④ Net profit (lnProfit). A high net profit indicates that the enterprise has good operating efficiency and greater investment possibilities. ⑤ Enterprise growth (Growth). Enterprise growth is a reflection of the comprehensive strength of an enterprise’s total factors and also a guarantee for its sustainable development. This article uses the growth rate of operating income to measure it. ⑥ Variables related to corporate performance and governance structure. Considering the impact of factors such as corporate performance and governance structure on corporate environmental protection investment, we introduce return on assets (Roa) and capital intensity (Cap_inten). Among them, return on assets is represented by the ratio of a company’s net profit to total assets; capital intensity is represented by the ratio of a company’s total assets to operating income. ⑦Capital surplus (lncr). Capital surplus is the amount of capital invested in the enterprise by investors or others that exceeds the legal capital. Some environmental protection investors prefer to invest in companies with environmental responsibility and sustainable development strategies, so companies with large environmental protection investment efforts are more attractive to them.

① Mediating variables: We select mediating variables from two aspects: the degree of financing constraints and the factor substitution effect. (1) In terms of financing constraints, drawing on the research of Wang et al. (2020), we introduce financing constraints as a mediating variable, and refer to Kaplan and Zingales (1997) to measure the degree of financing constraints using the KZ index. The higher the KZ index, the higher the degree of financing constraints of the enterprise. (2) In terms of factor substitution effect, we measure it using the ratio of net long-term investment, net fixed assets, net intangible assets, and total assets.

② The proxy variable for environmental concern draws on the method of Li-fe et al. (2014) and builds an environmental concern indicator variable based on the frequency of words related to “environmental protection” in the work reports of each provincial government.

③ Adjustment variables: The variables of monetary policy tightness and economic policy uncertainty were selected as adjustment variables. (1) The proxy variable of monetary policy tightness was measured by the growth rate of M2, which was calculated as (M2 in the current year - M2 in the previous year)/M2 in the previous year. The faster the growth rate of M2, the more the money supply increased, and the looser the monetary policy became. Conversely, the looser the monetary policy became. (2) The proxy variable of economic policy uncertainty was measured by the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index compiled by Scott R. Baker, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis from Stanford University and the University of Chicago. The variable construction information is shown in Table 1.

GCG is a national economic policy that was officially implemented in 2012. This article uses the difference-in-differences method to evaluate the implementation effect of the policy, and designs the model as follows:

Among them,

The application of the difference-in-differences method is premised on the exogenous nature of policy shocks. However, as China’s domestic emphasis on green finance continues to increase and the concept of global sustainable development deepens, the endogenous nature of the implementation of GCG will cause certain biases in the estimated results. Therefore, this article introduces the propensity score matching method (PSM) to weaken the bias caused by differences in initial conditions between the experimental group and the control group. The basic idea is to find an individual j in the control group that is as similar as possible to individual i in the experimental group in terms of observable variables. The specific approach is as follows: First, estimate the propensity score of the sample using Logit regression. Then perform one-to-one nearest neighbor matching between the experimental group and the control group based on the propensity score values. Finally, obtain a control group that matches the experimental group.

To further clarify the path of green credit on corporate environmental investment, this article sets up models (2) and (3) based on the basic regression model:

Among them,

Similarly, when testing the mediating effect of factor substitution effects, it is only necessary to replace the KZ data in models (2) and (3) with FS data.

The descriptive statistics of the main variables are shown in Table 2. According to Table 2, the mean value of lnEEPI is 12.51, the median is 13.14, which is higher than the mean value, and the standard deviation is 3.182. The maximum and minimum values are 18.88 and −3.507, respectively. It can be seen that there are significant differences in the amount of environmental protection investment among various enterprises in China, but the overall level is relatively high. In addition, Table 2 also shows that there are certain differences between various variables of enterprises. Therefore, it is particularly necessary to perform propensity score matching on the experimental group and control group and add appropriate control variables.

Table 3 shows the correlation between each variable. The results indicate that there is a strong correlation between the variables (significant at the 1% level). Except for a few variables, the correlation coefficients for most variables are less than 0.5, so there will be no serious multicollinearity problems in the subsequent regression analysis.

Table 4 presents the results of 1:1 nearest neighbor matching on the sample. From the results, it can be seen that after matching, except for the enterprise size, the standard deviations of the remaining variables are all less than 10%, indicating that the variable characteristics of the treatment group and control group samples are relatively close after propensity score matching, with small deviations and good matching effect. Compared with the results before matching, the standard deviations after matching have significantly decreased. Among them, the deviation of company age decreased by 98.10%, capital intensity decreased by 87.20%, total operating revenue decreased by 63.50%, return on assets decreased by 60.00%, growth decreased by 50.50%, company size decreased by 49.00%, capital reserves decreased by 38.80%, and net profit decreased by 11.10%. In addition, most of the t-test results do not reject the null hypothesis that there is no systematic difference between the treatment group and control group, and the t-statistic values of all variables have decreased after matching, passing the balance test and meeting the requirements of the double difference balance hypothesis.

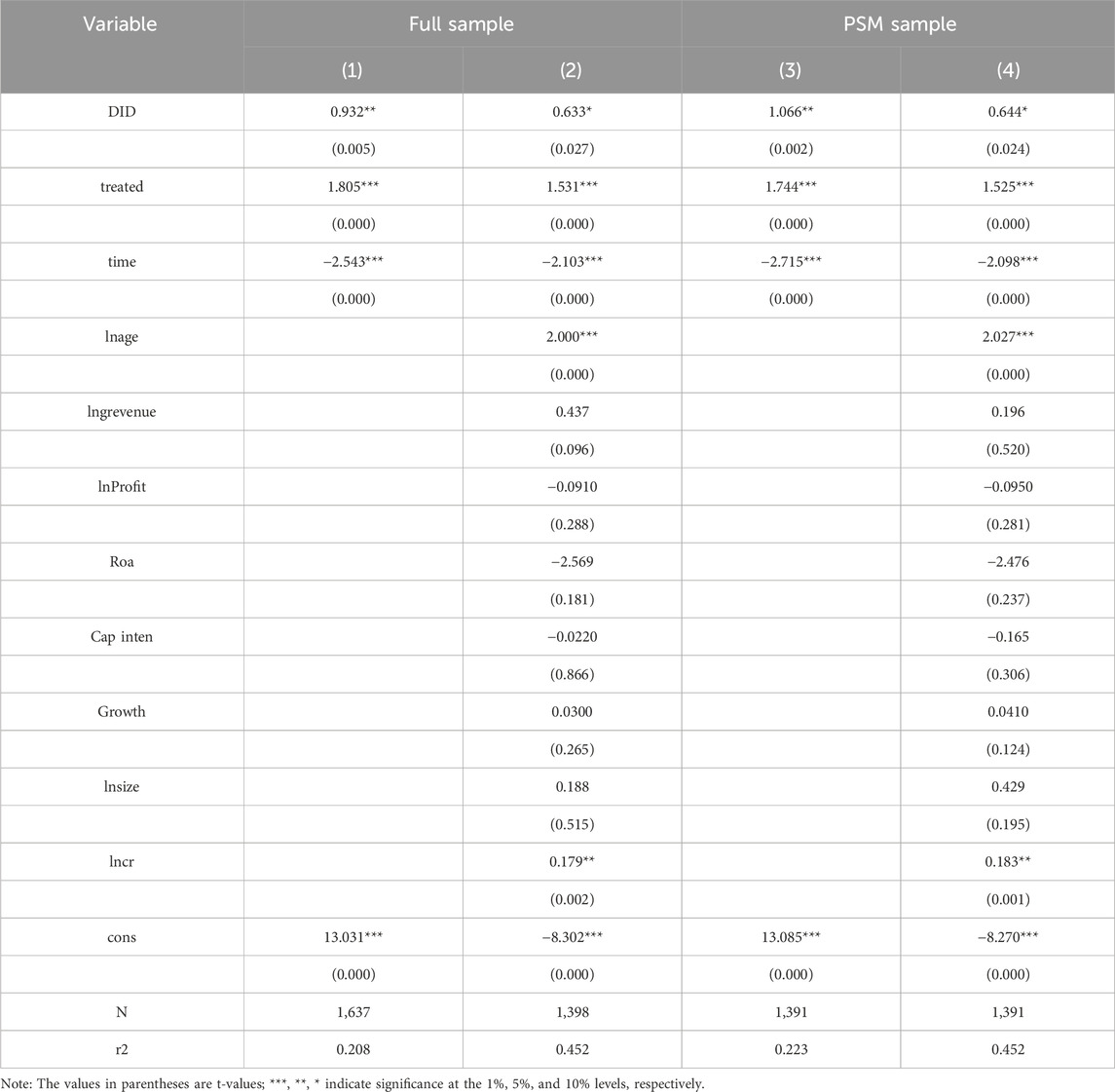

This article conducted a double difference test on the full sample and the PSM sample, and the benchmark regression results are shown in Table 5. In Table 5, columns (1) and (3) are the estimated results without adding other control variables, and columns (2) and (4) are the results with adding other control variables. The estimated value of the interaction coefficient in column (1) is 0.993, which is significant at the 5% level; the estimated value of the interaction coefficient in column (2) is 0.662, which is significant at the 10% level, indicating that the implementation of GCG has a positive impact on corporate environmental protection investment, and hypothesis 1 is established. In addition, from the regression results of control variables, the increase in company age, growth, and capital reserves will all lead to an increase in corporate environmental protection investment, indicating that there is a positive correlation between corporate “strength” and corporate environmental protection investment. Columns (3) and (4) are the regression results of the PSM sample, which are the same as the regression results of columns (1) and (2) for the full sample.

To verify the validity of the difference-in-differences regression results and enhance the reliability of the results, this article conducted robustness tests by restructuring the experimental and control groups, removing other policy interventions, redefining proxy variables, and conducting a placebo test.

We construct a new experimental group and control group by redefining the classification of heavily pollution industries. According to Di Zhou’s classification method, we select 17 categories of heavy pollution industries, with specific industry codes of B06, B07, B08, B09, B10, C14, C15, C17, C18, C19, C22, C25, C26, C27, C28, C29, C30, C31, C32, and D44. This results in a new experimental group and control group containing 1,072 and 565 sample data sets, respectively. On this basis, we construct a new difference-in-differences variable for testing. The regression results are shown in Table 6, which are basically consistent with the benchmark regression results.

Table 6. The results of the double difference regression after redefining the heavily polluting industries.

Regarding the concurrent environmental policies that may interfere with the results of this article: the Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (hereinafter referred to as the “Environmental Protection Law”), which was officially implemented in 2015, adopts the following measures: adding a policy dummy variable for 2015 to the benchmark regression. If the result after adding the policy dummy variable for 2015 is not significant, it indicates that the impact of GCG on environmental protection investment is not significant, and the results of this article are not robust; if the result after adding the policy dummy variable for 2015 is still significant, it indicates that the results of this article are robust. The regression results are shown in Table 7. The coefficient of the interaction term changes slightly compared to the benchmark regression results, and it is still significant at the 10% level, so the results of this article are robust.

The quantitative method of environmental protection investment in the main effect of this paper mainly takes into account the passive investment of enterprises in environmental protection due to government regulation. This article replaces enterprise environmental protection investment data. We refer to Zhang et al. (2022) for quantifying corporate environmental investment. Specifically, we define corporate environmental investment as the sum of capitalized and expensed corporate environmental expenditures. We use the variable of enterprise environmental protection investment obtained by this quantitative method to carry out substitution variable test. This paper takes capitalized and expensed expenditures for environmental protection as proxy variables of corporate environmental protection investment to analyze the degree of influence of GCP on enterprises’ active investment in environmental protection. Our empirical results are largely consistent with the benchmark regression results, indicating that the benchmark regression in this article is highly robust. The result is shown in Table 8.

Considering that the results of this article may be affected by other relevant time periods before the promulgation of GCG, a time placebo test was conducted by advancing the policy implementation time by 1 year to 2011 and re-constructing time dummy variables and interaction terms for regression. As shown in Table 9, regardless of whether other control variables were included, the obtained interaction term coefficients were not significant, indicating that advancing the policy implementation time would not significantly affect corporate environmental protection investment. Therefore, the policy effect is real and the results of this article are relatively reliable.

The theoretical and empirical analysis results above indicate that the green credit policy significantly promotes corporate environmental protection investment. This article will conduct heterogeneity analysis from two aspects: corporate ownership and geographical location. In order to analyze the impact of corporate ownership, this article uses a triple difference model for testing. On the basis of formula (1), the corporate ownership variable is introduced to construct a triple difference variable DDD for estimation, as follows:

Among them,

As shown in column (1) of Table 10, the impact of green credit on corporate environmental investment is more significant in state-owned enterprises. This may be due to the fact that state-owned enterprises, as the pillar of China’s national economy, have a demonstration and leading role, and therefore are more proactive in responding to new national policies. On the other hand, state-owned heavy polluting enterprises are often the key monitoring targets for pollution control, and usually bear certain political functions and policy tasks, which make them more susceptible to environmental regulation policies (Tietenberg et al., 1989).

Columns (2), (3), and (4) in Table 10 are the regression results after dividing the sample into East, Central, and Western regions. From the regression results, it can be seen that the regression results of the cross-terms in the eastern region are significant at the 5% level and the coefficients are positive, indicating that the green credit policy has a strong promoting effect on corporate environmental protection investment in this region. However, the coefficients of the cross-terms in the central and western regions are not significant and are all negative, indicating that the green credit policy has no significant impact on corporate behavior in these regions. The reason may be that China’s eastern region is economically developed, with relatively mature industries and mostly technology-intensive and financial services industries. The degree of pollution is not high, coupled with its own abundant funds, so it has the ability to carry out a series of environmental protection investments. While facing policy constraints, heavily polluting enterprises, as the main economic source in this region, have a more difficult time surviving under policy constraints. The lack of funds and the nature of the enterprise make it very difficult for them to carry out clean transformation, so it is reflected in the unclear policy effect.

The above analysis shows that the implementation of the green credit policy can promote corporate environmental investment to a certain extent, and the promotion effect is heterogeneous in different dimensions. As a macro policy tool, GCG have an impact on micro-enterprises. Therefore, this article explores the mechanism of GCG from the macro, meso, and micro levels.

A large number of scholars have found a close relationship between macroeconomic policies and micro-enterprise financial behavior (Serven et al., 1992). As one of the important macroeconomic policies, monetary policy affects the country’s money supply and market interest rates, which in turn affects the investment and financing behavior of enterprises.

To alleviate the high collinearity between the interaction term and the independent and moderator variables, this article performs a centralization process on the independent and moderator variables. The regression results of the test of the moderating effect of monetary policy tightening are shown in Table 11. The coefficient of the interaction term is significantly positive at the 5% level, indicating that the looser the monetary policy, the stronger the promotion effect of green credit on corporate environmental protection investment. Hypothesis 2 is established.

There is some controversy among scholars about the impact of economic policy uncertainty on corporate investment: some scholars believe that economic policy uncertainty brings opportunities to enterprises and helps them expand their investment scale (Wilson et al., 1975); while others believe that economic policy uncertainty will reduce corporate investment behavior (Almustafa et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2020). Although the conclusions are different, there is no doubt that economic policy uncertainty has a certain impact on corporate investment, so this article tests its moderating effect. The regression results are shown in Table 12. The coefficient of the interaction term is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that economic policy uncertainty plays a positive moderating role, and hypothesis 3 is established. The higher the economic policy uncertainty index, the less optimistic the macroeconomic environment, and the more difficult it is for heavily polluting enterprises subject to GCG to survive and develop. In order to preserve themselves, heavily polluting enterprises can only make themselves clean through continuous environmental protection investment to obtain more credit investment.

The degree of environmental concern of regional governments largely determines the attitude of enterprises in this region towards green production and sustainable development, which in turn affects their environmental investment efforts. The results of the moderating effect test of environmental concern are shown in Table 13. The coefficient of the interaction term is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the government’s environmental concern plays a positive moderating role between green credit and corporate environmental investment. The higher the degree of concern, the stronger the promotion effect of green credit on corporate environmental investment. Hypothesis 4 is established.

The regression results of the mediating effect are shown in Table 14 and Table 15. The P-value of the Sobel test is less than 0.01, which is significant at the 1% level, indicating the existence of a mediating effect. Among them, supporting the hypothesis that financing constraints play a negative mediating role in the impact of green credit on corporate environmental protection investment, and hypothesis 5 is established. It can be seen that the introduction of GCP restricts the financing of heavily polluting enterprises and exacerbates their financing constraints. Therefore, under the pressure of limited financing, enterprises will have incentives to invest in environmental protection, thereby alleviating the difficulties of financing constraints.

Tables 16, 17 reports the results of the mediation effect test of the factor substitution effect. It can be seen from the table that the P-value of the Sobel test is much smaller than 0.01, which is significant at the 1% level, indicating the existence of a mediating effect. This indicates that after the introduction of GCG, the development of heavily polluting enterprises has been greatly impacted. When financing difficulties increase and production costs increase to a certain extent, these heavily polluting enterprises will undergo factors substitution and technological progress in order to survive, which will ultimately promote the increase of corporate environmental protection investment.

This article examines the impact of China’s green credit policy on corporate investment behavior from the perspective of green finance. Specifically, this article constructs a quasi-natural experiment based on the Green Credit Guidelines issued in 2012, and uses the PSM-DID method to evaluate the impact of green credit on environmental protection investment of A-share listed companies from 2004 to 2020. The new conclusions found in this study are as follows: The study found that the implementation of green credit policy significantly promoted the environmental protection investment behavior of enterprises. Further analysis shows that from a macro perspective, economic policy uncertainty and monetary policy can positively regulate the promotion effect of green credit on enterprise environmental protection investment; from a meso perspective, government environmental concern plays a positive regulatory role between green credit and enterprise environmental protection investment; from a micro perspective, green credit policy can affect enterprise environmental protection investment through financing constraints and factor substitution effects. The heterogeneity test found that the green credit policy has different effects on enterprises with different characteristics. Specifically, compared with non-state-owned enterprises, the green credit policy has a more significant promoting effect on the environmental protection investment of state-owned enterprises; in terms of regional distribution, the impact of green credit policy on enterprise environmental protection investment is best in the eastern region, and the effect is not obvious in the central and western regions.

The research in this paper has obtained a wealth of conclusions, so it is necessary to compare with the previous work. This article has important theoretical value. It conducts in-depth analysis of corporate environmental protection investment in the field of green credit, which is rarely studied, increases the diversity of views in the field of green finance, enriches the theoretical basis for how to motivate enterprises to carry out environmental protection investment to achieve sustainable development goals, and responds to the call of Huang et al. (2021) that attention should be paid to corporate environmental protection investment behavior. However, there are differences between this paper and the existing literature in terms of the mechanism of green credit policy affecting corporate behavior: Contrary to the conclusion of most scholars (Aastveit et al., 2017; Phan et al., 2021) that economic policy uncertainty will inhibit the economic behavior of enterprises, the empirical study of this paper finds that economic policy uncertainty can positively regulate the role of green credit in enterprises’ environmental protection investment. That is, forcing companies to make green investments. This paper expands the research framework of economic policy uncertainty from the perspective of enterprise crisis sense and has new theoretical significance. In addition, this paper holds that the introduction of green credit policy exacerbates the financing constraints of heavily polluting enterprises, thus motivating them to make environmental protection investment to alleviate their difficult situation, which is different from the view of Chen et al. (2021) that supporting the development of green finance can reduce financing constraints and promote green innovation of enterprises. The conclusion of this paper can support the green credit policy to optimize the market structure and accelerate the liquidation of backward production capacity.

Based on the previous analysis, this article proposes the following policy recommendations:

(1) We will strengthen support for green credit and use financial constraints to force enterprises to invest in environmental protection. As the dual carbon targets are proposed and the time is approaching, the requirements for green ecological environment governance are becoming higher and higher. In order to better play the role of green financial policies, the government should strengthen supervision and punishment, forcing enterprises with higher pollution levels to carry out “clean” reforms.

(2) Increase monetary policy supply and policy stability, with special emphasis on the role of local governments in green finance. This paper finds that monetary policy and macroeconomic policy uncertainty have an important impact on the role of green credit policy. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen the stability of the government’s monetary policy and economic policy.

(3) Attach importance to the implementation of top-level GCP by local governments. This study shows that the higher the government’s attention to environmental protection, the more significant the promotion effect on corporate green investment. Therefore, government attitude largely determines the behavior of individual enterprises. In addition, due to the differences in the implementation effect of GCP among enterprises in different regions, the policy implementation effect in the central and western regions is not obvious. To solve this problem, the fundamental approach is to strengthen the attention of various governments in the region to the environment, increase the emphasis on sustainable development and green finance, and seek regional development in the balance of economy and ecology.

(3) Give full play to the leading and demonstration role of state-owned enterprises, and strengthen the green supervision and punishment of non-state-owned enterprises. State-owned enterprises are in a dominant position in many key areas and important sectors, and the Chinese government has also given them more funds. State-owned enterprises, which are in a dominant position in both economy and policy, should play a model role and lead more non-state-owned enterprises to respond to national policy calls. However, non-state-owned enterprises currently respond less actively to policies than state-owned enterprises. This can be achieved by adding corporate environmental protection levels and environmental indicators to the assessment of enterprises or their managers, and implementing necessary punishment measures to promote their environmental protection investment and other green financial activities.

However, there are also some shortcomings in this article: for the explained variable, this article uses data on pollution charges and environmental protection taxes instead of corporate environmental investment data, which inevitably involves subjectivity and some bias. This also points out several important directions for future research. Firstly, with more comprehensive and accurate disclosure and statistics in the field of green finance in the future, more objective and accurate indicators for corporate environmental investment evaluation and other indicators for measuring the sustainable development of micro-enterprises can be constructed. Secondly, the economic consequences of corporate environmental investment are also worthy of further research, which is not elaborated in detail in this article due to space limitations.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://data.csmar.com/.

RZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. YW: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing–review and editing. RL: Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Validation, Supervision, Writing–review and editing

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This paper thanks Soochow University and South China University of Technology for providing database resources.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aastveit, K., Natvik, G., and Sola, S. (2017). Economic uncertainty and the influence of monetary policy. J. Int. Money Finance 76, 50–67. doi:10.1016/J.JIMONFIN.2017.05.003

Agliardi, E., Pinar, M., and Stengos, T. (2017). Air and water pollution over time and industries with stochastic dominance. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 31, 1389–1408. doi:10.1007/s00477-016-1258-y

Allen, F., Qian, J., and Qian, M. (2005). Law, Finance, and Economic Growth in China. J. Financial Econ. 77 (1), 57–116. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.06.010

Almustafa, H., Jabbouri, I., and Kijkasiwat, P. (2023). Economic Policy Uncertainty, Financial Leverage, and Corporate Investment: Evidence from U.S. Firms. Economies 11, 37. doi:10.3390/economies11020037

Amacher, G., Koskela, E., and Ollikainen, M. (2004). Environmental quality competition and eco-labeling. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 47, 284–306. doi:10.1016/S0095-0696(03)00078-0

Baumc, F., Caglayan, M., and Ozkan, N. (2009). The second moments matter: the impact of macroeconomic uncertainty on the allocation of loanable funds. Econ. Lett. 102 (2), 87–89. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2008.11.019

Bloom, N. (2014). Fluctuations in Uncertainty. J. Econ. Perspect. 28 (2), 153–176. doi:10.1257/jep.28.2.153

Brandt, L., and Li, H. (2003). Bank Discrimination in Transition Economies: Ideology, Information, or Incentives? J. Comp. Econ. 31 (3), 387–413. doi:10.1016/s0147-5967(03)00080-5

Chan, C., and Yao, X. (2008). Air pollution in mega cities in China. Atmos. Environ. 42, 1–42. doi:10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2007.09.003

Chen, X., and Chen, Z. (2021). Can Green Finance Development Reduce Carbon Emissions? Empirical Evidence from 30 Chinese Provinces. Sustainability 13, 12137. doi:10.3390/su132112137

Fan, H. C., Peng, Y. C., Wang, H. H., and Xu, Z. W. (2021). Greening Through Finance. J. Dev. Econ. 152 (9), 102683–102717. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102683

Gao, D., Mo, X., Duan, K., and Li, Y. (2022). Can Green Credit Policy Promote Firms’ Green Innovation? Evidence from China. Sustainability 14 (7), 3911–3915. doi:10.3390/su14073911

Gulen, H., and Ion, M. (2016). Policy uncertainty and corporate investment. Rev. finance Stud. 29 (3): 523–564. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhv050

Hartman, R. (1972). The effects of price and cost uncertainty on investment. J. Econ. Theory 5 (2), 258–266. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(72)90105-6

Hemanand, D., Mishra, N., Premalatha, G., Mavaluru, D., Vajpayee, A., Kushwaha, S., et al. (2022). Applications of Intelligent Model to Analyze the Green Finance for Environmental Development in the Context of Artificial Intelligence. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 1–8. doi:10.1155/2022/2977824

Hong, M. N., and Quang, V. T. U. K. (2023). Economic policy uncertainty and innovation activities: A firm-level analysis. J. Econ. Bus. 123, 106093. doi:10.1016/j.jeconbus.2022.106093

Hu, G., Wang, X., and Wang, Y. (2021). Can the green credit policy stimulate green innovation in heavily polluting enterprises? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Energy Econ. 98, 105134. doi:10.1016/J.ENECO.2021.105134

Hu, Y., Jiang, H., and Zhong, Z. (2020). Impact of green credit on industrial structure in China: theoretical mechanism and empirical analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 10506–10519. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-07717-4

Huang, Y., and Sternquist, B. (2007). Retailers’ foreign market entry decisions: An institutional perspective. Int. Bus. Rev. 16, 613–629. doi:10.1016/J.IBUSREV.2007.06.005

Huang, Y. M., Xue, L., and Khan, Z. S. (2021). What abates carbon emissions in China: Examining the impact of renewable energy and green investment. Sustain. Dev. 29 (5), 823–834. doi:10.1002/sd.2177

Ji, L., Jia, P., and Yan, J. (2021). Green credit, environmental protection investment and debt financing for heavily polluting enterprises. PLoS ONE 16, e0261311. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0261311

Kaplan, S. N., and Zingales, L. (1997). Do Investment-n Cash FowSensitivitiesProvideUsefulMeasuresofFinan-l cing Constraints? Q. Journalof Econ. 112 (1), 169–215. doi:10.1162/003355397555163

Kirch, G., and Terra, P. (2019). Financial constraints and the interdependence of corporate financial decisions. RAUSP Manag. J. 55, 339–354. doi:10.1108/RAUSP-01-2019-0003

Kulatilaka, N., and Perotti, E. (1998). Strategic Growth Options. Manag. Sci. 44, 1021–1031. doi:10.1287/MNSC.44.8.1021

Le, Q. V., and Zak, P. J. (2006). Political risk and capital flight. J. Int. money finance 25 (2), 308–329. doi:10.1016/j.jimonfin.2005.11.001

Li-fe, X. (2014). A Comparative Study of Regional Environmental Protection Industry Development Base on Index System. Darwin: Territory & Natural Resources Study.

Liu, G., and Zhang, C. (2020). Economic policy uncertainty and firms’ investment and financing decisions in China. China Econ. Rev. 63, 101279. doi:10.1016/J.CHIECO.2019.02.007

Liu, S., Xu, R., and Chen, X. (2021). Does green credit affect the green innovation performance of high-polluting and energy-intensive enterprises? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 65265–65277. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-15217-2

Liu, X., Wang, E., and Cai, D. (2019). Green credit policy, property rights and debt financing: Quasi-natural experimental evidence from China. Finance Res. Lett. 29, 129–135. doi:10.1016/J.FRL.2019.03.014

Morgan, D. (1998). The Credit Effects of Monetary Policy: Evidence Using Loan Commitments. J. Money, Credit Bank. 30, 102–118. doi:10.2307/2601270

Munitlak-Ivanović, O., Zubović, J., and Mitić, P. (2017). Relationship Between Sustainable Development And Green Economy - Emphasis On Green Finance And Banking. Ekon. Poljopr. (1979) 64, 1467–1482. doi:10.5937/EKOPOLJ1704467M

Ng, A. (2018). From sustainability accounting to a green financing system: Institutional legitimacy and market heterogeneity in a global financial centre. J. Clean. Prod. 195, 585–592. doi:10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2018.05.250

Oi, W. Y. (1961). The desirability of price instability under perfect competition. Econ. J. Econ. Soc. 29, 58–64. doi:10.2307/1907687

Peng, B., Yan, W., Elahi, E., and Wan, A. (2021). Does the green credit policy affect the scale of corporate debt financing? Evidence from listed companies in heavy pollution industries in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 755–767. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-15587-7

Phan, D., Iyke, B., Sharma, S., and Affandi, Y. (2021). Economic policy uncertainty and financial stability–Is there a relation? Econ. Model. 94, 1018–1029. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2020.02.042

Porter, M. E., and Van der Linde, C. (1995). Toward a New Conception of the Environment Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspective 9 (4), 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Rowe, A., and Guthrie, J. (2010). The Chinese Government’s Formal Institutional Influence On Corporate Environmental Management. Public Manag. Rev. 12, 511–529. doi:10.1080/14719037.2010.496265

Serven, L., and Solimano, A. (1992). Private investment and macroeconomic adjustment : a survey. World Bank Res. Observer 7, 95–114. doi:10.1093/WBRO/7.1.95

Stoeppler, M., Backhaus, F., Schladot, J., and Nürnberg, H. (1984). Concept and Operational Experiences of the Pilot Environmental Specimen Bank Program in the Federal Republic of Germany. Berlin: Springer, 95–107. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-6765-6_14

Sun, J., Wang, F., Yin, H., and Zhang, B. (2019). Money Talks: The Environmental Impact of China’s Green Credit Policy. J. Policy Analysis Manag. 38, 653–680. doi:10.1002/PAM.22137

Tietenberg, T. (1989). Indivisible Toxic Torts: The Economics of Joint and Several Liability. Land Econ. 65, 305–319. doi:10.2307/3146799

Vural-Yavas, A. (2020). Corporate risk-taking in developed countries: The influence of economic policy uncertainty and macroeconomic conditions. J. Multinatl. Financial Manag. 54, 100616. doi:10.1016/j.mulfin.2020.100616

Wang, E., Liu, X., Wu, J., and Cai, D. (2019). Green Credit, Debt Maturity, and Corporate Investment—Evidence from China. Sustainability 11, 583. doi:10.3390/SU11030583

Wang, X., Elahi, E., and Khalid, Z. (2022). Do Green Finance Policies Foster Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance of Corporate? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 14920. doi:10.3390/ijerph192214920

Wang, Y., Lei, X., Long, R., and Zhao, J. (2020). Green Credit, Financial Constraint, and Capital Investment: Evidence from China’s Energy-intensive Enterprises. Environ. Manag. 66, 1059–1071. doi:10.1007/s00267-020-01346-w

Wen, H., Lee, C., and Zhou, F. (2021). Green credit policy, credit allocation efficiency and upgrade of energy-intensive enterprises. Energy Econ. 94, 105099. doi:10.1016/J.ENECO.2021.105099

Wu, Z., Tang, J., and Wang, D. (2016). Low Carbon Urban Transitioning in Shenzhen: A Multi-Level Environmental Governance Perspective. Sustainability 8, 1–15. doi:10.20944/PREPRINTS201607.0083.V1

Xu, J., and Yeh, A. (2009). Decoding Urban Land Governance: State Reconstruction in Contemporary Chinese Cities. Urban Stud. 46, 559–581. doi:10.1177/0042098008100995

Yao, S., Pan, Y., Sensoy, A., Uddin, G., and Cheng, F. (2021). Green credit policy and firm performance: What we learn from China. Energy Econ. 101, 105415. doi:10.1016/J.ENECO.2021.105415

Zhang, J. (2021). Green Policy, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Protection Investments - Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies in Heavy Pollution Industries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research: Springer. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1054167/v1

Zhang, K., Li, Y., Qi, Y., and Shao, S. (2021). Can green credit policy improve environmental quality? Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 298, 113445. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113445

Zhang, Y., Sun, J., Yang, Z., and Wang, Y. (2020). Critical success factors of green innovation: Technology, organization and environment readiness. J. Clean. Prod. 264, 121701. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121701

Zhang, J., Gao, C., Wu, S., and Liu, M. (2022). Can the carbon emission trading scheme promote corporate environmental protection investment in China?. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29 (4). doi:10.1007/s11356-022-21548-5

Zhu, Y., Niu, L., Zhao, Z., and Li, J. (2022). The Tripartite Evolution Game of Environmental Governance under the Intervention of Central Government. Sustainability 14, 6034. doi:10.3390/su14106034

Keywords: green credit policy, corporate environmental investment, PSM-DID, financing constraints, factor substitution effect

Citation: Zhu R, Wang Y and Li R (2024) Can green finance policies accurately promote corporate environmental investment?—a comprehensive evaluation from multiple aspects. Front. Environ. Sci. 12:1396687. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1396687

Received: 06 March 2024; Accepted: 11 July 2024;

Published: 30 July 2024.

Edited by:

Wei Zhang, China University of Geosciences Wuhan, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Zhu, Wang and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruiling Li, YWxpbmc4MjFAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.