94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci., 11 April 2024

Sec. Environmental Economics and Management

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2024.1381466

The principle that sustainable development can foster high-quality corporate growth has gained popularity as a tool for environmental protection. Utilizing data of firms listed on Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange from 2010 to 2020, this study investigates the impact of corporate carbon emissions management (CCEM) on the disclosure of key audit matters (KAMs). The findings indicate that CCEM can significantly elevate the adequacy of disclosure concerning KAMs. Tests on underlying mechanism underscore that accounting conservatism and audit quality serve as pivotal channels through which CCEM facilitates the disclosure of KAMs. Further analysis on economic consequences reveals that the disclosure of KAMs helps mitigate stock price crash risk while enhancing environmental, social, and governance performance. This study enriches research on factors influencing the disclosure of KAMs, concurrently providing valuable insights for advancing high-quality corporate development and facilitating communication between auditors and users of audit reports.

The Report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China explicitly outlines the primary objective of achieving high-quality development in the new era1. It emphasizes that, “Based on China’s energy and resource endowment, we will advance initiatives to reach peak carbon emissions in a well-planned and phased way in line with the principle of building the new before discarding the old.” (Zheng et al., 2023) The strategic decision to achieve carbon neutrality and peak carbon emissions (i.e., the dual-carbon goal) was first announced in September 2020 during the general debate of the 75th United Nations General Assembly. This initiative plays a crucial role in addressing the pressing issues of resource and environmental constraints, contributing notably to the attainment of sustainable development goals. To achieve systemic transition in the economic and social spheres, the Chinese government has issued the “Action Plan for Carbon Dioxide Peaking Before 2030,” proposing to “base economic and social development upon highly efficient utilization of resources and green and low-carbon growth.” At the institutional level, the Chinese government has introduced a “1 + N” policy framework, directing concerted efforts to guide further implementation of the dual-carbon goal.

In the globalized economic context nowadays, corporate carbon emissions management (CCEM) has become an important criterion for measuring corporate sustainable development capability and social responsibility. Not only is this assessment a matter of environmental concern, but it is also directly related to the financial health and operational efficiency of a company. A company’s carbon emissions have a direct impact on the rate and extent of global climate change, which in turn has a wide-ranging impact on the company’s own economic performance. On the one hand, higher levels of carbon emissions may trigger stricter government regulatory measures, such as carbon taxes or quotas. These regulatory measures, if implemented, will undoubtedly increase the operating costs of the affected companies, thereby reducing their profit margins. On the other hand, these dynamics present key challenges and opportunities from the perspective of corporate financial performance. The immediate compliance costs of environmental regulations like carbon taxes or quotas can be a drain on a company’s financial resources, but they may also promote operational innovation leading to cost savings in the long run, such as improved energy efficiency and more usage of renewable energy.

At the micro level of practical implementation, pending litigations, accounting uncertainties, and the authenticity and comprehensiveness of information disclosure have garnered attention from regulatory bodies in China’s capital markets, certified public accountants, and external stakeholders. Chinese regulatory authorities primarily strengthen oversight on CCEM through corrective directives and administrative penalties. For example, Chongqing Iron & Steel (Group) Co., Ltd. (A-share stock code: 601005) experienced a substantial change in circumstances during the execution of its contract with Chongqing Zhongjieneng Sanfeng Energy Co., Ltd. (A-share stock code: 601827) The newly revised Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China came into effect on 1 January 2015, enhancing the regulatory duties of national and local governments as well as the environmental governance restrictions placed on polluting companies. The law mandates reductions in emissions of carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and related waste materials in the steel industry. These changes affected the execution of the contract, leading to disputes regarding the calculation method for processing fees, compensation, and penalties. Owing to the matter’s involvement in pending litigation and its substantial impact on the company’s current financial reports, the engaged accounting firm (audit partner) has identified it as a major enhancement in auditor risk perception. Examining the effects of CCEM on information disclosure and the underlying mechanisms in the context of the dual-carbon goal is a crucial subject for advancing high-quality economic development.

To forge a high-level socialist market economy, China endeavors to enhance its risk monitoring and early warning system. This necessitates the regulation of market economic order, harmonization of legal frameworks to ensure financial stability, and augmentation of capabilities in risk prevention, supervision, and control. In December 2016, the Ministry of Finance issued “Auditing Standard No. 1504 for Certified Public Accountants of China-Communication on Key Audit Matters in Audit Reports.” Its introduction has propelled the alignment of Chinese auditing standards with international practices. It has enriched the information content, further standardized the consistency, and increased the communicative value of audit reports. Key audit matters (KAMs) are those matters that, in the auditor’s professional judgment, were of most significance in the audit of the financial statements of the current period. Key audit matters are selected from matters communicated with those charged with governance. Since the introduction of the new auditing standards, the economic ramifications associated with the disclosure of KAMs have been extensively explored, primarily concentrating on three main areas. First, research indicates that the disclosure of KAMs involves substantial market information content linked to risks of material misstatements (Brasel et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018), thereby elevating the quality of audit information (Wu et al., 2019). Second, the disclosure of KAMs has a positive impact on corporate investment efficiency (Muslu et al., 2019; Zhou and Gui, 2020; Wang and Zou, 2022), transmission of investment signals to the stock market (Song and Rao, 2022), and effective restraint against tunneling of controlling shareholders (Yao, 2022). Third, the disclosure of KAMs further influences auditor responsibilities (Han and Zhang, 2018), fostering an improvement in audit quality in terms of risk and responsibility perception (Zhou et al., 2020).

Research has also investigated factors influencing the disclosure of KAMs. On the one hand, auditor traits can have a certain impact on KAM disclosure. For instance, industry expert auditors, shared auditors, and audit independence can contribute to more comprehensive disclosures (Pan, 2020). On the other hand, the individual characteristics of an audited entity can influence the disclosure of KAMs. Factors such as firm financialization, audit quality, and audit fees can have a certain impact (Fu and Liao, 2022). However, few studies have examined the influence of the behavioral characteristics of an audited entity on the disclosure of KAMs.

In light of this, this study utilizes data of Chinese A-share listed firms from 2010 to 2020 and investigates whether and how the disclosure of KAMs is influenced by their CCEM. This study attempts to test if CCEM can elevate KAM disclosure. We conduct a series of robustness check including propensity score matching, Heckman two-stage estimation, lagged explanatory variables, and control of omitted variables. Furthermore, tests on potential underlying mechanism find that accounting conservatism and audit quality reinforce the promotive effect of CCEM on the disclosure of KAMs. In addition, we discuss how CCEM can mitigate stock price crash risk and enhance green technological innovation through promoting KAM disclosure. This study, grounded in empirically verified evidence from textual analysis of KAM disclosure, systematically examines, both theoretically and empirically, the impact of CCEM on the disclosure of KAMs from the perspective of pollutants emitted during business operations. This approach addresses the viewpoint of achieving high-quality development for firms under the dual-carbon goal, thereby providing insights for further regulating corporate green transformation and elevating the quality of KAM disclosure. Besides, this study incorporates CCEM, disclosure of KAMs, accounting conservatism, and audit quality in the analytical framework. It aims to validate that the disclosure of KAMs can serve as a foundation for further communication between expected users of financial statements and those charged with governance regarding matters associated with the audited entity, audited financial statements, and conducted audit work. In the context of China’s current dual-carbon goal, this perspective of auditing contributes insights for strengthening carbon management.

According to signaling theory, reducing information asymmetry is crucial to safeguarding the interests of stakeholders and providing additional incremental information for investors in their decision-making (Plumlee et al., 2015). The primary motivation for disclosing KAMs in the audit report is to enhance the information content and relevance of the audit report. In terms of characteristics, KAMs involve significant areas and relevant matters with distinct features related to the business. The KAMs identified by auditors based on their professional judgment can have a notable impact on the professional competence of practitioners, users of financial statements, and external stakeholders (Spence, 2002; Li et al., 2022). KAMs can reduce information asymmetry, making it easier for external stakeholders to access crucial information about the firm (Wang et al., 2022). By disclosing carbon emission data, firms communicate information about their environmental and sustainability performance to investors, creditors, and other stakeholders, aiding in reducing information uncertainty. KAM disclosure thus helps diminish information asymmetry, making the market more efficient.

On the one hand, with the further advancement of China’s dual-carbon goal, government departments and external stakeholders are paying increased attention to environmental protection-related information of firms. CCEM, as an indicator of a firm’s compliance with environmental laws and regulations, serves as an informational conduit in terms of sustainable operations, compliance, legal adherence, and long-term strategic planning for the firm. Research has found that CCEM can reduce the cost of debt financing and equity financing for firms (Lemma et al., 2019). The incremental risk information and important asset transaction information associated with CCEM both affect auditory attention, which could potentially influence the disclosure of KAMs. First, CCEM, as a crucial feature of corporate information disclosure, can influence the information content of audits and the level of earnings management. This influence aims to uncover information value and enhance in-depth communication between the auditors and audited entities (Yang and Li, 2020). The accuracy of corporate carbon emissions data is closely related to the quality of firms’ internal control systems. Auditors assess internal controls to determine and identify potential risks and ensure the accuracy of data. Second, CCEM directly relates to the integrity and accuracy of a firm’s environmental data. Auditors must ensure that the carbon emissions data provided by firms are accurate and complete, without any misrepresented or misleading information. If CCEM is subject to misreporting or intentional manipulation, resulting in inaccurate data, then the credibility of the financial statements would be compromised. During risk assessment, auditors continuously adjust their judgment of expected earnings against analyst profit forecasts. CCEM can indirectly manipulate corporate performance/earnings uncertainty and earnings management, leading auditors to adopt conservative language in stating KAMs and issue conservative audit reports (Liao and Yang, 2021). Third, CCEM requires compliance with relevant regulations and standards. Auditors need to confirm whether a firm adheres to applicable carbon emissions regulations and the legal requirements for disclosing related information. If a firm fails to comply with regulations, auditors must pay attention to potential legal risks and consequences, which can impact the disclosure of KAMs.

On the other hand, based on contemporary risk-oriented audit theory, the audit of CCEM is currently encountering uncertainties, estimation errors, and complexities in internal controls. The presence of these factors may elevate the level of audit risk (Zhang and Lyu, 2009). Specifically, calculating corporate carbon emissions intensity involves a large amount of environmental data and estimations. These data and estimations typically come with uncertainties, requiring auditors to assess data accuracy and ascertain the reasonability/validity of estimations. When reporting carbon emissions data, firms typically need to make managerial estimations and assumptions, which are based on the management’s professional judgment and experience, thus potentially introducing subjectivity. Auditing CCEM also requires consideration of a firm’s internal control system to ensure data accuracy and compliance. The collection and reporting of environmental data involve multiple departments and data sources, adding complexity to the internal control structure. Auditors pay attention to and assess the risk factors faced by firms. For one, firms face the risk of material misstatements owing to information disclosure. The disclosure of KAMs by auditors can serve as an essential means of mitigating professional risks (Huang and Tang, 2021). From a reputation perspective, audit failures can considerably impact an auditor’s reputation and future career development (Brasel et al., 2016). Auditors are motivated to pay attention to a firm’s carbon emissions data, ensuring its accuracy and compliance. They may take actions, such as increasing audit procedures, expanding the scope of substantive testing, and strengthening communication with the management, to augment the quantity and content of KAMs, further mitigating their own culpability (Qian et al., 2022). Based on the analysis above, we posit the following research hypothesis:

H1:. CCEM lead auditors to disclose KAMs more comprehensively.

External stakeholders and minority shareholders have a heightened demand for accounting conservatism, seeking a conservative view of a firm’s operational and financial status to predict its accounting information (Tang and Han, 2018). Accounting conservatism, as a crucial accounting policy, allows the management to exercise discretion in response to changes in the external environment. When a firm exhibits low accounting conservatism, auditors, adhering to the prudence principle, are more likely to pay attention to market vis-à-vis accounting indicators. By comparing analysts’ value/valuation predictions, auditors proactively disclose the potential risks of material misstatements. This approach involves disclosing incremental information in audit reports to better leverage the capital market’s governance effect (Li and Wu, 2019; Zhuang and Lian, 2022). The data and estimations of CCEM concerning environmental responsibilities are influenced by the expectations of the firm’s stakeholders, leading the firm to potentially adopt a more proactive and optimistic approach regarding environmental costs and liabilities. This optimistic approach can lead to the adoption of more positive estimations and reduction in potential loss provisions, thereby weakening the conservatism of financial statements (Chen et al., 2007). This phenomenon can impact the quality of financial statements, making them more inclined to reflect a positive financial situation while overlooking potential negative risks and uncertainties. In this context, auditors need to pay closer attention to the audit of environmental data to ensure the reasonability/validity of these data and the accuracy of financial statements. Consequently, auditors may express doubts on the listed firms’ financial health and accounting information quality, leading to the disclosure of more KAMs.

According to stewardship theory, audit quality serves as a convenient measure for financial statement users to assess the auditor’s work. A higher sense of responsibility and risk perception encourages auditors to maintain a skeptical attitude in audit planning and execution. They approach material misstatement risks cautiously, leading to the disclosure of more KAMs (Gutierrez et al., 2018). In the context of sustainable environmental and resource development, CCEM may give rise to legal or regulatory violations (Chen and Seng, 2016), potentially subjecting a firm’s operations to considerable uncertainty. Indeed, the discrepancy between a firm’s environmental strategy and its actions significantly impacts sustainable business operations (Wang, 2020). The recognition and measurement of environmental liabilities, such as fines for environmental violations, costs related to pollution control, disposal expenses/abandonment costs, and ecological restoration expenditure, can directly influence the current profitability of a firm. Consequently, this scenario could result in a significant risk of material misstatement in financial reporting. As such, auditors need to examine whether the audited entity’s disclosed carbon emissions information complies with relevant laws and regulations. Simultaneously, they must allocate more resources to assess the accuracy of the listed firm’s disclosure of environmental information. This approach ensures the issuance of more accurate and rigorous audit opinions. In summary, the disclosure of corporate carbon emissions information can better reflect the auditor’s level of responsibility and professional competence. This, in turn, prompts the issuance of higher-quality audit reports and increases the likelihood of disclosing KAMs. Based on the analysis above, we posit the following research hypothesis:

H2:. Accounting conservatism is a crucial mechanism through which CCEM promotes the disclosure of KAMs. Specifically, the promotive effect of CCEM on KAM disclosure increases with a decrease in the level of accounting conservatism.

H3:. Audit quality is a critical mechanism through which CCEM promotes the disclosure of KAMs. Specifically, the promotive effect of CCEM on KAM disclosure increases with an improvement in audit quality.

Auditing Standard No. 1504 for Certified Public Accountants of China - Communication on Key Audit Matters in Audit Reports was established in 2016. To accurately examine the specific impact of CCEM on KAM disclosure before and after the implementation of the new standard, this study utilized Chinese firms listed on Shanghai Stock Exchange and Shenzhen Stock Exchange from 2010 to 2020 as the initial research sample. The choice of the 2010–2020 period allows for a comprehensive before-and after comparison while mitigating the confounding variables introduced by the pandemic. This time frame enables an accurate depiction of the evolution of KAM disclosures, untainted by the extraordinary circumstances post-2020. Considering the research theme and the distribution pattern of the research sample, as well as accessibility, we applied the following preprocessing criteria to the data: 1. Exclusion of special treatment and particular transfer firms and firms in abnormal states; 2. Exclusion of listed firms in the financial and insurance sectors; 3. Exclusion of firms with less than 1 year of listing; 4. Exclusion of firms with missing observational data. After data filtering, we obtained a total of 15,390 annual observations. To mitigate the impact of outliers, we winsorized all continuous variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

The financial data from annual reports of listed firms utilized in this study were obtained from the Wind database. Data pertaining to the disclosure of KAMs were gathered by manually reviewing annual reports and subsequently processed using textual analysis techniques in Python. Data on accounting conservatism and audit quality were gathered from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database and derived subsequently.

KAMs may be measured in three ways. First, a binary variable, KAMIF, can be set to indicate whether a firm discloses KAMs in a given year (Li et al., 2022). If KAMs are disclosed in a given year, KAMIF takes the value of 1; otherwise, it takes the value of 0. Second, the comprehensiveness of KAM disclosure of listed firms can be measured by counting the number of KAMs disclosed (KAMN) (Chen et al., 2021). Finally, the readability of KAM disclosure is captured by constructing the KAM readability index (KAMRead). We created this specific index using deep learning algorithms as follows: 1. Utilizing word embedding to represent each word as a dense fixed-length real-value vector, in which semantically similar words possess similar vector representations in the vector space; 2. Following the optimization principles of Hierarchical Softmax and Negative Sampling to calculate the sentence’s probability of generation; 3) Computing the logarithmic mean of the product of generation probabilities of individual sentences as a measure of document readability. The equation can be expressed as follows:

in which

We constructed the corporate carbon emissions intensity (CI) as an indicator of CCEM following Chapple et al. (2013) and Shen and Huang (2019). The carbon dioxide conversion factor that we used adopted the standard of 2.493 from Xiamen Energy Conservation Center. The data on total industry energy consumption and industry main costs were respectively obtained from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook and China Industry Economy Statistical Yearbook. We used the following formulae for calculation:

in which CI is corporate carbon emissions intensity, CCE is corporate carbon emissions, EMR is the main business revenue of the firm, TIEC is total industry energy consumption, CCF is carbon dioxide conversion factor, and IMC is industry main costs. A higher CI value indicates higher corporate carbon emissions intensity.

Following Qian et al. (2022) and Menon and Williams (2010), we introduced a series of control variables that may affect KAM disclosure. Table 1 gives the definition of all variables.

We analyzed the impact of CCEM on the disclosure of KAMs using a two-way fixed-effects model:

in which KAM represents the variables of KAM disclosure, using the indicators of whether KAMs were disclosed in a given year (KAMIF), quantity of KAMs disclosed (KAMN), and readability of KAMs disclosed (KAMRead). Controls pertain to a series of variables influencing the disclose of KAMs; Ind and Year represent industry and year fixed effects, respectively. Industry fixed effects are used to control for time-invariant omitted industry characteristics. Their inclusion ensures that estimates of

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables. The results showed no significant differences in the level of KAM disclosure among different listed firms. Moreover, the overall carbon emissions of the sample firms were relatively low. We found no significant differences in carbon emissions intensity among different listed firms. These results are consistent with those in previous studies (Reid et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022). Additionally, we conducted correlation coefficient estimates and variance inflation factor tests on the relevant variables, and the results indicated the absence of multicollinearity among the selected variables2.

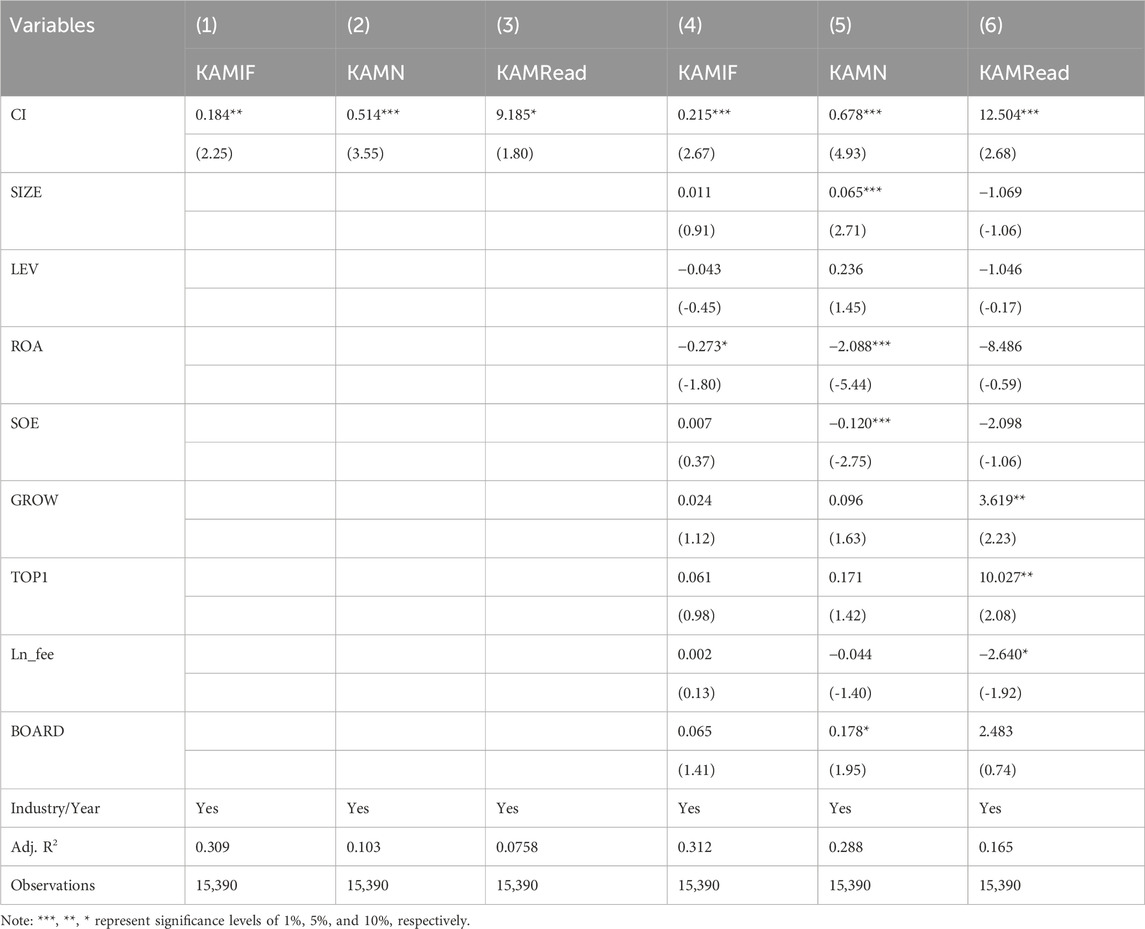

Table 3 presents the regression results of the impact of CCEM on the disclosure of KAMs. In columns (1), (2), and (3), CCEM, as indicated by CI, is included in the regression, controlling for industry and year fixed effects. According to the results, without control variables, the coefficient of CI is significant at least at the 10% significance level in all three columns. After controlling for other factors that influence the disclosure of KAMs, as shown in column (4), (5), and (6), the coefficient of CI remains significant at the significance level of 1%. These results indicate that CI increases the disclosure of KAMs, which supports H1. As CCEM is closely related to corporate environmental compliance and financial truthfulness, to meet the needs of investors and other stakeholders for corporate environmental responsibility and sustainable development performance, auditors will increase the transparency and credibility of the disclosure in the auditor’s report to reduce their own auditing risks. This in turn increases the disclosure of KAMs.

Table 3. Regression results on the impact of corporate carbon emission practices on key audit matter disclosure.

Among the control variables, there is a significantly positive relationship between Size and KAMN, indicating that larger firm size leads to more disclosure of KAMs, as larger firms usually have more complex business operations and financial structure, and therefore more disclosure of KAMs is needed to satisfy the regulatory requirements and investor information needs (Bepari et al., 2022). ROA has a significantly negative impact on KAMIF and KAMN. Higher ROA usually reflects good financial performance and lower business risk of the firms. Therefore, auditors may perceive that less risky firms need to disclose fewer KAMs (Rousseau and Zehms, 2024). There is a positive relationship between SOE and KAMN. SOEs are subject to stricter government regulation and control, and their risk of non-compliance is lower compared to that of non-SOEs. Therefore, SOEs have lower number of disclosures of KAMs (Florou et al., 2021). Growth and Top1 have positive impact on KAMRead. Business expansion and the growth of the number of shares held by the largest shareholder tend to be subjected to more public attention and regulatory requirements, which force auditors to disclose more comprehensible and high-quality auditing information (An et al., 2023). There is a negative relationship between Fees and KAMRead. Higher audit fees may imply that more time and resources need to be invested in the audit process to deal with complex and high-risk matters, resulting in the language and content in the audit report to become more technical and complex, reducing the readability of KAMs (Al Lawati and Hussainey, 2021). The adjusted

To address potential self-selection issues, we employ propensity score matching (PSM) to alleviate endogeneity. Initially, we divide the samples into a treatment group and a control group based on whether the listed firms engaged in CCEM. Specifically, we established a binary variable T_CI to encode CCEM, with a value of 1 for firms engaged in CCEM (treatment group) and 0 for those not engaged in CCEM (control group). Subsequently, we use this encoded variable as the grouping variable (T_CI) to estimate the propensity scores using a logit model, in which the explained variable is T_CI and the explanatory variables consist of all control variables used in this study. To minimize potential sample selection bias, we employ 1:1 nearest neighbor matching. Finally, we individually map the obtained matched samples to regression analysis. The results in Table 4 indicate that the core explanatory variable CI demonstrates a significantly positive impact on KAMIF at the 5% significance level. Similarly, the relation between CI and KAMN is positively significant at the 10% significance level. Additionally, the association between CI and KAMRead is significantly positive at the 5% significance level. These regression results closely align with the baseline results, further affirming the robustness of the outcomes in our study.

Considering that not all sampled firms disclose CCEM, we recognize the influence of various external policies and internal strategic decisions on related practices, which could lead to potentially spurious estimations. To further alleviate potential self-selection bias, we use a Heckman two-stage estimation model. In the first-stage estimation using a Probit regression model, we establish the variable T_CI as a dummy variable for CCEM. This model simultaneously includes all control variables. Following the regression, the computation yielded the inverse Mill’s ratio (IMR). In the second-stage estimation, we introduce the IMR as an additional control variable. The results, presented in Table 5, indicate a significantly positive relationship at the 5% significance level between CI and KAMIF. Additionally, a significantly positive relationship at the 1% significance level is observed between CI and KAMN. Furthermore, CI demonstrates a significantly positive impact at the 5% significance level on KAMRead. The consistency of these results with the baseline regression result verifies the robustness of the empirical model.

To mitigate potential endogeneity issues arising from reverse causality between CCEM and the disclosure of KAMs, we conduct regression using the lagged one-period explanatory variables. The regression results are presented in Table 6. L_CI exhibits a significantly positive correlation with KAMN at the 5% significance level and with KAMRead at the 10% significance level. After introducing control variables, we note that the coefficient of CI remains significantly positive at the 5%, 1%, and 5% significance level, respectively. The consistent findings further confirm the robustness of our baseline regression results.

To alleviate endogeneity issues resulting from omitted variables, we further control for the individual traits of auditors. The personal traits of auditors reportedly have a certain impact on audit quality, which may, in turn, influence the disclosure of KAMs (Cai and Xian, 2007). We re-estimate the model by further controlling for auditor’s degree in accounting, gender, educational background, and number of listed firms audited in a given year. As shown in Table 7, CI exhibits a significantly positive correlation with KAMIF, KAMN, and KAMRead at 10% significance level at least. Upon introducing control variables, we note that CI demonstrates a significantly positive relationship with KAMIF, KAMN, and KAMRead at the 1% significance level. The research conclusions remain largely unchanged.

As discussed in Section 2.2, the effects of CCEM on KAM disclosure may be transmitted through two channels: accounting conservatism and audit quality. From the perspective of information asymmetry, CCEM could serve as a crucial external signal that influences the level of attention given to accounting earnings. When a firm exhibits low accounting conservatism, auditors, guided by the prudence principle, pay closer attention to both market and accounting indicators. Proactively disclosing risks of material misstatements, auditors enhance the transparency of the executed audit work and augment the communicative value of the audit report through the disclosure of KAMs. Therefore, we introduce accounting conservatism (C_Score) as a mediating variable for underlying mechanism. We define accounting conservatism by considering CCEM as a “bad/unfavorable news” that can bring detrimental effects on firms (Basu, 1997). We gauge accounting conservatism by measuring the extent of earnings change indicative of the influence stemming from this bad/unfavorable news. From the perspective of stewardship, CCEM directly impacts the quality of financial reports, drawing significant attention from stakeholders. Out of their own professional considerations, auditors show heightened anxiety regarding risks and uncertainties. They maintain a cautious/prudent attitude in risk assessment and audit procedures, consequently influencing audit quality. Therefore, we introduce audit quality (AQ) as a mediating variable for underlying mechanism. We use the degree of audit opinion aggressiveness to measure audit quality (Basu, 1997).

We devise a mediation model to examine the potential mechanism of how CCEM influence the disclosure of KAMs. Utilizing a step-by-step approach (Baron and Kenny, 1986), we employ the following model to test for mediating effects.

in which MID represents the mediating variable accounting conservatism, proxied by accounting conservatism (C_Score) and audit quality (AQ).

Table 8 reports the estimation results with accounting conservatism as the mediating variable. In column (1), the coefficient of CI is −0.051, significantly negative at 5%. The results indicate that CCEM reduces the accounting conservatism of a firm. In columns (3), (5), and (7), the significant coefficient values reveal the presence of an obscuring effect of accounting conservatism in the relationship between CCEM and KAM disclosure, which verifies H2. Given that CCEM represents bad/unfavorable news, accountants operating within an uncertain environment may exhibit biases in quantifying potential risks or losses. This could consequently lead to risks of material misstatements in financial reports. From a prudent perspective, auditors may disclose more KAMs to augment the communicative value of audit reports. This involves promptly and accurately providing additional information. Such disclosures assist users in comprehending the issues that auditors consider pivotal in their audit of financial statements for a given period.

Table 9 reports the estimation results with audit quality as the mediating variable. The results in column (1) shows a coefficient of 0.416, significant at the 1% significance level, indicating that CCEM enhances audit quality. In columns (3), (5), and (7), the significant coefficients imply that audit quality partially mediates the relationship between CCEM and KAM disclosure, which verifies H3. CCEM may serve as a significant “greenwashing” strategy for firms. Firms might selectively disclose or disclose more favorable information to enhance their reported environmental performance, potentially reducing the likelihood of regulatory investigations. As government and stakeholders increasingly demand disclosure of environmental information, auditors are likely to pay more attention to the disclosure of environmental matters in audit planning and execution, thereby enhancing audit quality. Auditors, influenced by client impression management practices, may adjust the level of environmental disclosure during audits, thereby ensuring that the overall assessed audit risks remain manageable.

Low information transparency is a major factor contributing to stock price crash risk. After accumulating to a certain threshold, bad/unfavorable news collectively released to the external market can have substantially negative effects on a firm’s stock price, ultimately leading to a crash (Xu et al., 2013). When a firm experiences a high degree of financialization, the management can utilize financial assets to manipulate profits for short-term performance embellishment to conceal negative information. Public knowledge of accumulated negative information can lead to a stock price crash (Xu et al., 2013). Auditors play a crucial role as information intermediaries in the capital market, facilitating the transmission of firm-specific information to investors. The disclosure of KAMs provides investors with more decision-relevant information, contributing to increased accounting information transparency and disclosure quality. This, in turn, helps reduce the stock price crash risk. Therefore, CCEM, through enhancing KAM disclosure, may mitigate stock price crash risk.

To examine the aforementioned question, we measure stock price crash risk using the negative skewness of stock i’s weekly returns adjusted for market conditions (Xu et al., 2013). The regression model includes CCEM (CI), KAM disclosure (KAMIF, KAMN, KAMRead), and their interaction terms (CI

The report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China proposed strengthening green innovation to promote high-quality economic development. The issuance of the “Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) for National Economic and Social Development and Vision 2035 of the People’s Republic of China” has provided policy guidance to the market and firms. On the one hand, the demand for environmentally friendly offerings encourages consumers to transit to low-carbon consumption. This green demand also conveys environmentally friendly concepts to supply-side firms, compelling them to engage in green innovation to provide the market with green offerings. On the other hand, with the continuous improvement of environmental regulations, corporate pollution emissions standards and penalties are more strictly scrutinized. The compliance of CCEM has become a focal point of interest for stakeholders. Under regulatory pressure and in response to commitments to investors, firms are driven to actively pursue green innovation. To examine the aforementioned issues, we employ green invention patent applications by firms as the measure of green innovation (Zheng et al., 2023). The regression includes CCEM (CI), KAM disclosure (KAMIF, KAMN, KAMRead), and their interaction terms (CI

Under the new pattern of carbon neutrality and peak carbon emissions, the enhancement of audit risk control ability induced by CCEM will be a key element in the improvement of auditors’ professional quality. This study examines the control effect of CCEM on audit risk from the perspective of disclosure of KAMs. It is found that CCEM can improve auditors’ disclosure of KAMs, specifically in terms of increasing the number of disclosed KAMs as well as improving the readability of KAM disclosure. Overall, CCEM can improve the adequacy of disclosure of KAMs. The analysis of the underlying mechanism reveals that CCEM is perceived to be a kind of bad/unfavorable news, and firms tend to use earnings management and other manipulative ways to make a whitewash to reduce accounting soundness. To reduce audit risk, auditors tend to improve audit quality to enhance the disclosure of KAMs. Further analysis found that CCEM and the disclosure of KAMs help to convey more transparent information to the market, which in turn reduces stock price crash risk. Furthermore, the market transmits the concept of green demand back to firms, forcing to improve green innovation of listed firms.

Contrasting our findings with those from various international contexts underscores either the universal applicability or the distinctiveness of our conclusions. Divergences in the focus on environmental strategies and their implications for financial reporting and audit results are notably pronounced across different jurisdictions (Al Lawati and Hussainey, 2022). For example, research within European settings might demonstrate a stronger impact of environmental regulations, attributed to their rigorous regulatory landscapes (de Nichilo, 2022). Conversely, studies from markets with less stringent regulations might not reflect a comparable trend, highlighting the crucial role of regulatory frameworks in influencing corporate transparency (Fox, 2007). By comparing our research with these global studies, we aim to ascertain the degree to which national policy structures and market dynamics moderate the relationship between CCEM and KAM disclosure.

The observed disparities and commonalities across different geographical areas highlight the possibility of generalizing our findings, while also laying the groundwork for subsequent inquiries into the contextual determinants that may amplify or mitigate the effects noted, thereby enriching our comprehension of the underlying dynamics. In terms of managerial implications, our research provides tangible insights for both corporate executives and auditing professionals. For corporate managers, the established connection between robust CCEM and increased transparency in KAMs indicates that adopting environmental strategies serves dual purposes: fulfilling regulatory and social obligations and bolstering corporate transparency, thereby improving relationships with investors. For auditors, our results underscore the significance of integrating environmental and sustainability considerations within the auditing framework, as these elements are progressively shaping risk evaluations and focal points in financial disclosures.

Additionally, the established positive relationship between CCEM and KAM disclosure, and its consequential role in diminishing stock price crash risk, underscores the extensive impact of environmental and sustainability initiatives on financial stability and corporate governance. Consequently, firms might perceive notable benefits from incorporating sustainability objectives into their strategic frameworks. This integration extends beyond mere compliance with regulations or fulfillment of social responsibilities. It emerges as a strategic asset capable of reducing financial vulnerabilities and improving perceptions in the market.

Consequently, while our study provides foundational insights specific to the Chinese market, the broader debate and comparison with other countries reveal that the interconnections between environmental strategies, audit practices, and financial transparency are a global phenomenon. This understanding is crucial for firms operating in an increasingly interconnected and environmentally conscious global economy.

Based on the conclusions drawn from this study, the following policy implications are highlighted: First, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China should identify the entities responsible for CCEM and establish a standardized system for calculating carbon emissions. To facilitate effective CCEM and achieve emissions reduction goals, regulatory bodies must accurately identify and define the organizations, firms, and individuals playing crucial roles in CCEM activities. Another essential aspect is the establishment of a corporate carbon emission disclosure platform to standardize the measurement, recording, and reporting of carbon emission and ensure data comparability and verifiability. Non-compliant entities may face penalties, such as reduced quota allocations or withdrawal of government funding. Furthermore, regulators should establish a coordinated supervisory mechanism to address the issue of high disclosure levels of CCEM among information technology and financial-industry firms and low disclosure levels among high-polluting firms. CCEM must be standardized to reduce the CCEM costs for firms and organizations, with the aim of enhancing transparency and sustainability.

Second, policymakers should strengthen the supervision of carbon emissions rights trading. First, policies should be formulated to enhance the audit supervision of carbon emissions quota issuance and compliance of firms subject to emissions control in terms of account opening and fulfillment. This involves reviewing the annual disparity between the total carbon emissions of firms subject to emissions control and the issuance requirements. It also requires verifying the establishment of carbon emissions registration books by firms subject to emissions control and ensuring compliance with quota payment obligations. In the context of carbon emissions trading, auditing departments should focus on scrutinizing the rationality of the design of carbon emissions trading systems and assessing whether the trading regulations and systems are robust. In the process of carbon emissions verification and certification, regulators should focus on examining whether third-party verification agencies comply with the standards for calculating carbon emissions, and whether their workflow and operations are standardized.

Third, regulatory authorities should further integrate corporate information disclosure and appropriately guide and inspect specific items in the disclosure of KAMs. First, regulatory authorities should further refine the disclosure standards for KAMs, considering not only quantity and length but also explicitly requiring auditors to provide conclusive evaluations in their disclosures. This aids in ensuring a more precise assessment of firms’ financial condition by auditors, avoiding templated and homogenized approaches. Second, to ensure the effectiveness of KAM disclosure, regulators should establish an evaluation mechanism specifically aimed at assessing the quality of audit reports. This involves regularly evaluating the content and accuracy of audit reports to promptly identify and rectify any non-compliant disclosure practices, thereby maintaining market order. Third, regulators should implement enhanced supervision and inspection of auditors to ensure compliance with relevant disclosure standards.

We conclude by outlining related questions that are beyond the scope of this paper. First, carbon emission data in the information disclosure process lack credibility and comparability due to several factors, including the lack of a scientific and uniform carbon audit assurance system and assurance standards, “overprotective tendency” of enterprises towards carbon emission information, lack of specific guidelines for carbon emission disclosure, and lack of carbon accountants’ ability to control carbon information. Second, although multiple tests have been conducted to alleviate endogeneity, testing causality using an external shock would be ideal. Third, CCEM plays multifaceted roles in corporate governance; however, how best to utilize CCEM and design proper mechanisms to maximize the contribution remains unknown. Generalizability may be limited as our study focuses on specific regions, industries, or firms types. These issues warrant future research. While our dataset concludes in 2020, this limitation is underpinned by a rationale deeply rooted in ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and relevance of our findings within the scope of our research theme.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: The data that support the findings of this study are in Chinese and available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to d2FuZ2d1b3FpbmcxMDAyQDE2My5jb20=.

GW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing–original draft. MW: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1The 1 in the “1 + N” policy framework refers to the “Opinions on Working Actively and Prudently toward the Goals of Reaching Carbon Emissions Peaking and Carbon Neutrality” issued at the policy level, while N includes the action program for carbon emissions peaking by 2030 and policy measures and actions in key areas and industries to be gradually implemented in the future. The “1 + N” policy framework clarifies the main objectives, carbon reduction pathways, and relevant supporting measures from the top-level design, and provides policy support for the future carbon emissions peaking and carbon neutrality action program, as well as policy measures and actions in key areas and industries.

2For brevity, the results are not tabulated, but are available upon request.

Al Lawati, H., and Hussainey, K. (2022). The determinants and impact of key audit matters disclosure in the auditor’s report. Int. J. Financial Stud. 10 (107), 107. doi:10.3390/ijfs10040107

An, R., Li, W., Wang, D., Wang, Y., and Yu, L. (2023). Do key audit matters affect operating activities? Evidence from inventory management. Abacus 59, 300–339. doi:10.1111/abac.12269

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Basu, S. (1997). The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. J. Account. Econ. 24 (1), 3–37. doi:10.1016/s0165-4101(97)00014-1

Bepari, M. K., Mollik, A. T., Nahar, S., and Islam, M. N. (2022). Determinants of accounts level and entity level key audit matters: further evidence. Account. Eur. 19 (3), 397–422. doi:10.1080/17449480.2022.2060753

Brasel, K., Doxey, M. M., Grenier, J. H., and Reffett, A. (2016). Risk disclosure preceding negative outcomes: the effects of reporting critical audit matters on judgments of auditor liability. Account. Rev. 91 (5), P1–P10. doi:10.2308/ciia-51546

Cai, C., and Xian, W. D. (2007). The correlation between auditor industry specialization and audit quality-evidence from the audit market of listed companies in China. Accounting Research 6, 41–47+95.

Chapple, L., Clarkson, P. M., and Gold, D. L. (2013). The cost of carbon: capital market effects of the proposed emission trading scheme (ETS). Abacus 49, 1–33. doi:10.1111/abac.12006

Chen, L. H., Yi, B. X., Yin, M. H., and Zhang, L. P. (2021). Will industry-specialist auditors adequately disclose critical audit matters? Account. Res. 2, 164–175.

Chen, Q., Hemmer, T., and Zhang, Y. (2007). On the relation between conservatism in accounting standards and incentives for earnings management. J. Account. Res. 45, 541–565. doi:10.1111/j.1475-679x.2007.00243.x

Chen, S. F., and Seng, H. Y. (2016). How environmental information disclosure affect CPA audit: empirical evidence from the heavy pollution industry. J. Xi’an Univ. Finance Econ. 29 (4), 101–107.

de Nichilo, S. (2022). How to resolve audit matters in European Affairs? Introduction to a sustainable management accounting under IAS 37. Eur. J. Soc. Impact Circular Econ. 3 (1), 27–41.

Florou, A., Wu, X., Shuai, Y., and Zhang, V. (2021). State ownership, political influence and audit reporting: evidence from key audit matters. SSRN Electron. J. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3944779

Fox, J. (2007). The uncertain relationship between transparency and accountability. Dev. Pract. 17 (4-5), 663–671. doi:10.1080/09614520701469955

Fu, Q., and Liao, Y. H. (2022). The effect of the auditor independence on KAM disclosure: client importance perspective. J. Audit Econ. 37 (1), 53–68.

Gutierrez, E., Minutti-Meza, M., Tatum, K. W., and Vulcheva, M. (2018). Consequences of adopting an expanded auditor’s report in the United Kingdom. Rev. Account. Stud. 23, 1543–1587. doi:10.1007/s11142-018-9464-0

Han, D. M., and Zhang, J. X. (2018). Disclosure of key audit matters and auditor’s perception of audit responsibility. Auditing Res. 4, 70–76.

Huang, L. H., and Tang, X. Y. (2021). Exemption effects of key audit matters: real earnings management and differentiation in the disclosure of key audit matters. J. Finance Econ. 47 (2), 139–153.

Lemma, T. T., Feedman, M., Mlilo, M., and Park, J. D. (2019). Corporate carbon risk, voluntary disclosure, and cost of capital: South African evidence. Bus. Strategy Environ. 28, 111–126. doi:10.1002/bse.2242

Li, S. H., Wu, Z. Y., and Cheng, X. (2022). Key audit matters and managerial myopia. Auditing Res. 4, 99–112.

Li, W. F., and Wu, C. (2019). Industrial policy and accounting conservatism. Account. Res. 1, 65–71.

Liao, Y. G., and Yang, Y. X. (2021). Can auditors identify the risk signals delivered in analysts’ forecast: a textual analysis based on the tone of key audit matters. Contemp. Finance Econ. 1, 137–148.

Menon, K., and Williams, D. D. (2010). Investor reaction to going concern audit reports. Account. Rev. 85 (6), 2075–2105. doi:10.2308/accr.2010.85.6.2075

Muslu, V., Mutlu, S., Radhakrishnan, S., and Tsang, A. (2019). Corporate social responsibility report narratives and analyst forecast accuracy. J. Bus. Ethics 154, 1119–1142. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3429-7

Pan, K. Q. (2020). Does the disclosure of critical audit matters alter the auditors’ audit responsibility awareness? A research from the perspective of audit pricing. Econ. Surv. 37 (3), 108–116.

Plumlee, M., Brown, D., Hayes, R. M., and Marshall, R. S. (2015). Voluntary environmental disclosure quality and firm value: further evidence. J. Account. Public Policy 34 (4), 336–361. doi:10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2015.04.004

Qian, A. M., Xiao, Y. C., Zhu, D. P., and Wu, C. T. (2022). Does the financialization of non-financial enterprises affect the disclosure of key audit matters? Auditing Res. 5, 63–74.

Reid, L. C., Carcello, J. V., Li, C., Neal, T. L., and Francis, J. R. (2019). Impact of auditor report changes on financial reporting quality and audit costs: evidence from the United Kingdom. Contemp. Account. Res. 36, 1501–1539. doi:10.1111/1911-3846.12486

Rousseau, L. M., and Zehms, K. M. (2024). It’s a matter of style: the role of audit firms and audit partners in key audit matter reporting. Contemp. Account. Res. 41 (1), 529–561. doi:10.1111/1911-3846.12902

Shen, H. T., and Huang, N. (2019). Will the carbon emission trading scheme improve firm value? Finance Trade Econ. 40 (1), 144–161.

Song, X. Y., and Rao, J. (2022). The content of information disclosure on key audit matters. Friends Account. 16, 129–136.

Spence, M. (2002). Signaling in retrospect and the informational structure of markets. Am. Econ. Rev. 92 (3), 434–459. doi:10.1257/00028280260136200

Tang, Q. Q., and Han, H. W. (2018). Related party M&As and firm value: the governance effect of accounting conservatism. Nankai Bus. Rev. 21 (3), 23–34.

Wang, F., and Zou, M. Q. (2022). Disclosure of key audit matters and investment efficiency of enterprises: empirical evidence of textual analysis. Auditing Res. 3, 69–79.

Wang, H. T., Cao, W. C., and Wang, Y. M. (2022). Key audit matters disclosure and corporate accounting conservatism: evidence based on quasi-natural experiments and textual analysis. J. Audit Econ. 37 (4), 43–56.

Wang, J. H. (2020). Can enterprise environmental management improve audit quality? J. Xi’an Univ. Finance Econ. 33 (1), 77–85.

Wang, Y. Y., Xu, R., Wang, C. L., and Yu, L. S. (2018). Can key audit matters enhance the communication value of the audit report? Account. Res. 6, 86–93.

Wu, P., Chen, S. Y., Ren, J. Y., and Sun, W. C. (2021). Effects of actuation of nanoporous gold on cell orientation in a fibroblast sheet. J. Southeast Univ. (Philosophy Soc. Sci.) 23 (4), 103–115+152. doi:10.1007/s10856-021-06584-w

Wu, X., Fan, Y. J., Yang, Y. L., and Chen, G. Q. (2019). Energy use by globalized economy: total-consumption-based perspective via multi-region input-output accounting. Account. Res. 12, 65–76. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.108

Xu, N. H., Yu, S. Y., and Yi, Z. H. (2013). Institutional investors’ herding behavior and stock price crash risk. J. Manag. World 7, 31–43.

Yang, Q., and Li, T. (2020). Evaluation research on the influential effect of auditing risk from key audit matters disclosure. J. Xi’an Univ. Finance Econ. 33 (5), 43–51.

Yao, Y. F. (2022). Can critical audit matter disclosure inhibit the tunneling of controlling shareholders? Evidence from tunneling critical matters. J. Shanghai Univ. Finance Econ. 24 (5), 92–107.

Zhang, C., and Lyu, W. (2009). Disclosure, information intermediary, and over-investment. Account. Res. 1, 60–65+97.

Zheng, L. X., Guo, J., and Zheng, F. H. (2023). Does the energy saving and emission reduction fiscal policy promote the quantity and quality of green technology innovation? J. Cap. Univ. Econ. Bus. 25 (5), 3–19.

Zheng, X., Wang, J., Chen, Y., Tian, C., and Li, X. (2023). Potential pathways to reach energy-related CO2 emission peak in China: analysis of different scenarios. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 66328–66345. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-27097-9

Zhou, L., Gui, X. J., Jiang, X. M., Zheng, Y., Chen, X., Fu, Z., et al. (2020). Absorbed plant MIR2911 in honeysuckle decoction inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication and accelerates the negative conversion of infected patients. J. Industrial Technol. Econ. 39 (6), 54–60. doi:10.1038/s41421-020-00197-3

Zhou, Z. S., He, C., and Shao, W. (2020). Key audit matter disclosures and audit fees. Auditing Res. 6, 68–76.

Keywords: corporate carbon emissions management, disclosure of key audit matters, accounting conservatism, audit quality, China

Citation: Wang G and Wu M (2024) Corporate carbon emissions management and the disclosure of key audit matters. Front. Environ. Sci. 12:1381466. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1381466

Received: 03 February 2024; Accepted: 01 April 2024;

Published: 11 April 2024.

Edited by:

Alex Oriel Godoy, University for Development, ChileReviewed by:

Camelia Hategan, West University of Timișoara, RomaniaCopyright © 2024 Wang and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maoguo Wu, d3VtYW9ndW9Ac2h1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.