- 1Department of Chemistry, College of Science, University of Bahrain, Sakhir, Bahrain

- 2Department of Materials Science, Institute of Graduate Studies and Research, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

Waste management (WS) has been identified as one of Bahrain’s most pressing concerns owing to the potential negative consequences for the country. Data collected over the last 30 years show considerable growth in waste amount created in the country throughout the sectors of residential, commercial, institutional, building and demolition, municipal services, public places, treatment plant sites, manufacturing, and crop residues. The restricted location space, characterised by Bahrain’s tiny geographic area, is the most significant element contributing to the difficulty of controlling the government’s rising waste buildup and developing Sustainable Waste Management systems. As a result, the study focuses on the rising have to upgrade the government’s present municipal solid wastes Management (MSWM) system. Which the study discussed the municipal solid wastes Management in Bahrain that was consisted of Solid Waste generation, composition, and characteristics and also discussed the waste collection, transportation, disposal and regulations and institutions in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Furthermore, The study focused on the general views about waste management and privatization. Also, discussed MSWM and sustainable development goals and privatization as a private sector in the context of SDGs.

1 Introduction

Waste is a major problem in today’s consumer-driven world. Under immense pressure, the local government must find sustainable ways to handle this massive garbage volume. Waste management systems have received less attention in city design than water and electricity. Waste management is an area where modern urban planning fails. High consumption rates have made municipal household solid waste a global issue (Parashar et al., 2020). The Earth summit 2002, paid high attention to sustainable consumption and production. According to the United Nations report, at least 12 out of the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) are directly related to waste management such as SDG 12. Those goals assist in the prevention or minimization of domestic solid waste and encourage reuse, recycling and use of environmentally eco-friendly materials (Laso et al., 2019; UNEP, 2020). Hence, municipal waste management is an important issue globally, and a major barrier to sustainability (Tudor et al., 2011). Consequently, there is a necessity in reducing the impacts of waste and raising awareness on waste reduction and recycling methods among the community. Because the continuous production of waste in huge quantities leads to depletion of natural resources. Henceforth, serious thinking for sustainable practices, sustainable consumption, development of smart waste management systems, and recover resources instead of disposed of. For instance, in China, the process of converting waste to fertilizer is a common process since the year 2000 BC (Zaman and Lehmann, 2011).

To get from the first Eve to the point where there were one billion people in the world in the early 1800s took nearly three million years of human history. More than 200,000 people are added to the world’s population every single day, and the population doubles every 12–14 years (Cointreau, 2011). Half of the world’s population already resides in urban areas, and by mid-century, the majority of all regions will be urban. Comparatively more people live in cities in high-consuming nations than in low-consuming ones. In Australia, one of the world’s top consumers, approximately 89% of the population resides in metropolitan regions. Mega-regions, urban corridors, and city regions are all produced by cities that stimulate economic development (Lehmann, 2010). Large cities in developing nations have a unique environmental challenge in the form of solid waste (Kanat et al., 2006). MSW has been put to alternative uses such as composting, separation, and recycling, especially in third world nations. Waste management is still an issue in many of these nations (Cointreau, 2006). Due to its ease of use and cheap price, unclean landfilling or open dumping has been the primary method of solid-waste disposal in a number of poor nations (Blight, 2008).

Roughly 1.7–1.9 billion tonnes (109 Mg) of MSW were produced globally in 2006 (Chalmin et al., 2009). Over the past century, the Arab world’s population has grown from 50 million to over 325 million (Tolba and Saab, 2008); concurrently, the region’s economic development, urbanisation, industrialization, and improvement in people’s standard of living have contributed to an increase in the amount of municipal solid waste produced (Al-Yousfi, 2006). Despite rising expectations, most Arab nations still only have a semi-developed MSW management system and a nascent resource management infrastructure. Only around 20% of MSW is processed properly and only about 5% is recycled at the moment (Tolba and Saab, 2008), with uncontrolled landfills still being the most common disposal technique (Al-Yousfi, 2006). To ensure a seamless and effective transition to sustainable resource management in such a constantly evolving context, it is crucial to monitor and assess the management of MSW properly and fully. However, there are not many articles on MSW in the West Arab area accessible in the scholarly literature (Mrayyan and Hamdi, 2006; Al-Salem et al., 2009; Al-Khatib et al., 2010). The United Arab Emirates generates 2.2 kg of municipal solid waste per inhabitant, making it one of the highest rates in the world among the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. This is followed by Qatar, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Bahrain. MSW is the second biggest source of urban waste after building wastes, which together are anticipated to equal over 150 million tonnes annually in the GCC. Several nations, like Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, have recently developed large-scale solid waste management initiatives, the success of which has not yet been determined. Countries in the Middle East are, on the whole, spending extensively on waste management projects, sourcing new technology, and boosting public awareness in order to face the issue of waste management. But the amount of trash being made is not keeping up with how quickly the area is growing. Policymakers, urban planners, and other stakeholders in the Middle East have a significant issue when it comes to the management of the mountains of waste that are piling up in the region’s cities.

Many countries in the Middle Eatst have implemented comprehensive recycling programs, encouraging citizens to segregate waste at source. Recycling initiatives not only reduce landfill pressure but also conserve resources and promote a circular economy. Advanced Waste-to-Energy technologies have been adopted in several countries, converting MSW into energy, thus minimizing landfill usage and generating electricity or heat, contributing to renewable energy sources (Alsabbagh, 2019). Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programs hold manufacturers accountable for the entire lifecycle of their products, including proper disposal. This approach encourages eco-friendly product design and responsible waste management practices. Successful waste management systems often involve active community participation. Awareness campaigns, education, and incentivized initiatives enhance public involvement, leading to improved waste segregation and reduced littering. Technological advancements, such as IoT-enabled bins and data analytics, optimize waste collection routes and schedules, minimizing operational costs and ensuring timely waste pickup (Mancini et al., 2017).

However, public consumption of goods is the major causal driver of change in production activities and flows of wastes to the environment. For instance, the European environment agency has found that the key environmental pressure is caused by household consumption. The number of deficiencies in the current solid waste management system is causing the incapacity of different sectors to fully meet the standards of efficient solutions, even though domestic solid waste still causes major harm to the economy, environment, and human health (EEA, 2012; Mohammed, 2012). Waste and secondary resource management is a multifaceted endeavour that is increasingly needing holistic, integrated strategies. A relatively recent systems approach, Integrated Sustainable Waste Management (ISWM) enables governments to maximise environmental advantages while minimising costs associated with waste management (van de Klundert et al., 2001).

Improper solid waste management leads to major problems, especially in developing countries. Therefore, there is a need for different ways to deal with waste such as recycling or composting, to reduce waste and its risks (Kanat, 2010). Bahrain is one of the small islands countries due to the small size, increasing population growth and rapid industrialization, and lack of appropriate policies, which leads to leaving a negative impact on environmental resources and increased pollution (Khalil and Suliman, 2017; Al-Joburi, 2018).

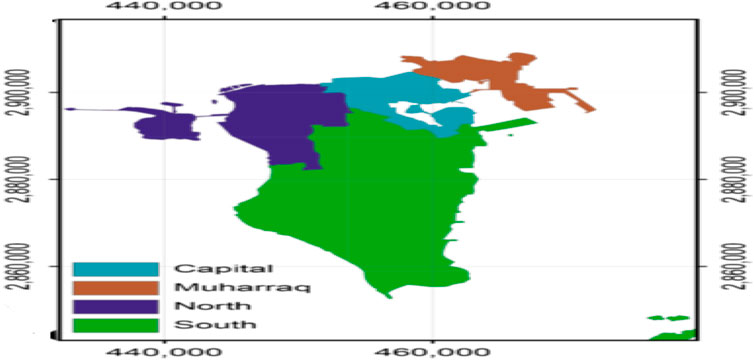

While the total land area of the Kingdom of Bahrain is relatively modest, more than two-thirds of the population resides in the capital city of Manama on Bahrain Island. With a population of almost 1.6 million, Bahrain has the greatest population density in the GCC area. Statistics show that the country generates over 1.2 million tonnes of solid trash annually, making it one of the top waste-generating nations on a per-person basis. The increasing waste in Bahrain may be traced back to the country’s expanding population as well as its boom in building and manufacturing. Because of geographical constraints and a lack of designated landfills, it is difficult for policymakers and municipalities in Bahrain to effectively manage the country’s growing waste problem. There is a rising focus on the need for all nations to minimise waste and become more sustainable in this era of the circular economy. The existing waste management practises in Bahrain are examined, along with the significant problems, opportunities, efforts, and strategy in delivering acceptable waste management and recycling solutions for a sustainable future by Waste and Recycling Middle East. The current municipal solid waste management in Bahrain is served in all areas. The location of the dumpsite in Askar area (Figure 1). Two commercial companies are now in charge of the five governorates of the Kingdom of Bahrain’s trash collection and waste transportation networks (Figure 2). Waste collection and transportation in Muharraq and Manama (the capital) is handled by Gulf City Cleaning Company (GCCC), whereas in the Southern, Middle, and Northern Areas, this task falls under the purview of Sphinx Services. Since October 2019, Urbaser has been operating the Askar landfill under the monitoring of the Ministry of Works and Municipal Affairs (Mohammed, 2012; Al-Joburi, 2018). These businesses evolved out of the concept of privatising sanitation services. The “cellular tipping technique,” in which trash is dumped within a sealed area or depression enclosed by a pre-built bund, is used for landfilling at the currently operational Landfill Site. But there are rising worries about such tactics. The following site issues are a direct result of these procedures and processes. Lack of: planned development inside the site, investment funds for new landfill equipment and site upgrades, cellular tipping techniques, suitable covering materials, landfill gas production, leachate generation, fire dangers, and bird hazards. When such a waste management system is in place, sustainability efforts, the quality of the environment, and the safety of the public are all in jeopardy. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance to improve the country’s present approach to managing municipal solid waste. The primary goal of this analysis and evaluation is to create an ISWM system suitable for the present conditions in Bahrain, taking into account all the aforementioned issues, complications, and concerns.

FIGURE 2. Illustrate the administrative division of the Kingdom of Bahrain divided into four governorates, which are Capital, Muharraq, Northern, and Southern governorates. The Capital is the most populated, and the Southern Governorate is the least populated.

1.1 Study background

Wastes are the unutilized tangible byproducts of human activity that are regarded as unwanted and useless (Tchobanoglous and Kreith, 2002). Waste, contrary to popular belief, can be recycled into new products and used to generate new forms of energy if handled properly. However, managing is difficult, particularly in the modern period when so many elements have piled on additional limitations and difficulties. Effective waste management has emerged as one of our era’s most pressing challenges due to related issues of lifestyle preservation, environmental protection, and public health promotion. Many studies have focused on municipal solid wastes (MSW), which are defined as wastes generated in private homes and collected by municipal agencies (Strange, 2007). A more precise definition of MSW, however, depends on the existing makeup of the municipality, the state, or the nation. Municipal solid wastes (MSW) from homes, businesses, institutions, building and demolition sites, public spaces, treatment facility grounds, factories, and farms all fall under the umbrella of municipal solid wastes (MSW) in Bahrain.

Wastes are typically seen as non-production related and only handled when the need to find a solution to the issue outweighs the cost of doing so via simple disposal (Seadon, 2010). This line of thinking has long guided waste management, leading to a variety of inefficient approaches to the ever-increasing trash load and the dwindling effectiveness of waste-control infrastructure. In this regard, studies that have examined global waste management systems have shown that sustainability is one element that has not been satisfied adequately. The term “sustainable development,” which encapsulates the concept of sustainability, is commonly understood to refer to “development that fulfils the requirements of the present without compromising the capacity of future generations to satisfy their own needs” (Brundtland, 1987). This term establishes the need to consider the benefits to future generations when designing solutions to improve our immediate surroundings. Therefore, it is imperative that municipal solid waste management systems not only handle the current complexity and underlying circumstances but also negotiate for long-term efficiency.

Municipal solid waste (MSW) levels are growing at an alarming rate across the globe. In 2000, it was predicted that a total of 2.5 billion metric tonnes (MT) of MSW will be produced globally; this number is projected to rise to 5.3 billion MT by the year 2030. The rate of solid waste creation in Bahrain and the GCC ranges from 470 to 700 kg/capita/year, making it one of the highest in the world. More than four thousand tonnes of municipal solid waste (MSW) are produced every day in Bahrain, and they are collected by private contractors and sent to the Asker municipal dump site, which is situated in the quarry regions about 2five km outside of the city centre.

The primary purpose of that study (Mohammed, 2012) was to assess the existing SWM system in the kingdom of Bahrain and to identify the issues that have hindered its effective facilitation. In addition, it aimed to create an ISWM strategy to deal with rising environmental, public health, and safety concerns about the status quo SWM setup. Al-Joburi (Al-Joburi, 2018) showed that the Kingdom of Bahrain is severely contaminated due to the haphazard and unsystematic disposal of municipal solid waste. The suggested approach was successful, and it may now serve as a template for tracing the distribution of litter. Khalil and Suliman (Khalil and Suliman, 2017) used two analytical methods to determine the optimal landfill location. Fuzzy Set analysis and Analytical Hierarchy Process analysis are used, both of which are based on multi-criterion decision making. Both methods provide almost identical findings, with the rankings of the five choices being nearly identical with the exception of places 3 and 4, where landfill 3), placed underneath the current landfill at Askar, is deemed to be the best solution. Sabbagh et al. (Al Sabbagh et al., 2012) contributed the first Middle Eastern city to the UN-Habitat database on solid waste management in the world’s cities by creating a profile of the country’s waste management and recycling programmes based on that organization’s established city profile methodology. In order to maximize recovery and reduce transportation costs, (Mancini et al., 2017), offered an approach to an insular self-contained waste management system.

The nations of the GCC produce a disproportionate amount of waste compared to their populations (Al Ansari, 2012). The Kingdom of Bahrain is included among the Gulf Cooperation Council members. The United Arab Emirates produces the most waste per capita in the GCC, at about 2.2 kg a year (Alghazo et al., 2018). Annual waste production in the GCC as a whole is estimated to be between 90 and 150 million metric tonnes. Only about 5% of waste is reused, with the rest going to landfills or being dumped illegally. Rapid increases in waste production are predicted, with 2022 seeing a volume of waste that is 1.5 times to 2 times more than what it is now (Alghazo et al., 2018). All the GCC nations, like most developing countries, are using landfills to dispose of their municipal solid waste (MSW), which has detrimental effects on the environment, the economy, and society. Askar Landfill, the only municipal solid waste landfill in the Kingdom of Bahrain, is now at capacity (Alghazo et al., 2018). As a result of the current crisis, it is important to find good ways to deal with MSW in the country.

1.2 Research problem

Few academics and industry professionals have conceptually addressed the difficulties facing the GCC region’s waste management sector (Zafar, 2016). Which argue that the waste management industry in the GCC is experiencing a number of obstacles at the moment, including.

• The solid waste industry is poorly governed, from collection to transformation and disposal or treatment.

• The inadequacy of existing legal frameworks and the enforcement mechanisms controlling the solid waste industry.

• Public services, such as MSW management, are within the purview of government agencies.

• Shortage of resources (both human and material) and inability to effectively implement change.

• Lack of dependable historical context and current state information on garbage.

Moreover, the following reasons were identified as impediments to waste management in Bahrain (Batteries, 2017): The lack of commitment to implementing a sustainable waste management strategy and the allocation of essential resources is a result of a gap between high-level policymakers and the lower entities responsible for waste management (NGOs, individuals, industries, etc.). Entity-level lack of coordination in governance and conflicts of interest arising from overlap in regulatory, operational, and other tasks are examples of the second kind of governance flaw. Thirdly, there is not enough information to go around because entity managers do not have the proper data management, controls, monitoring systems, tools, or resources. The entities that were asked for information for this study had poor and inconsistent historical records, as well as a general lack of information and consistency.

Municipal solid waste is one of major issues facing the developing countries, while Bahrain is considering a special case due to limited small land area, population growth and density, economic development, and lack of waste treatment facilities. There is only one existing landfill site in Bahrain - Asker landfill - that is the only officially practice and this landfill is not engineered as sanitary landfill, and waste disposal has peaked to more than 1.9 million tons in 2018. From environmental point of view, the landfilling practice is not considered a sustainable method, and this practice cannot be continued at the long term due to limited area of Bahrain. In this regard, Bahrain has taken an important step to foster best environmental practice towards attain sustainable waste management system by endorsed the “Bahrain’s national waste management strategy”.

In this research emphasis is on municipal solid waste in the context of sustainable development goals (SDGs) based on environmentally, socially and economically. This study aims to assesses the privatization waste collection services sector in Bahrain with respect to effectiveness and efficiency. Some important issues should be focused on the privatization project. First, no evaluation study has been conducted since starting the privatization process and implementation. Secondly, the service contract should include a set of criteria for evaluating performance based on sustainability, which leading to assessment and improvement of efficiency and effectiveness of waste collection services. Lastly, the extension of contracts should be based on competitive and the set of criteria.

1.3 Research questions

The key research questions address in this study are.

• What is the level of evaluation of the privatization experience in waste collection and disposal in Bahrain in terms of waste disposal?

• What is the impact of engaging the private sector in solid waste collection for the sustainability of urban service provision at the regional and global levels compared to the Bahrain experience.

• What is the efficiency and quality of the services of private companies related to solid waste collection and sorting services.

• What are the main factors that describe the differences in performance and service quality of private companies in the context of the principle of sustainability of waste management.

• What are the capacity building programs that improve Bahrain’s ability to solve waste management issues and determine the suitability of best environmental practices and the best available technological opportunities.

• What are the prospects for introducing small businesses at the local level to make solid waste a useful business based on the partnership between the public and private sectors.

• What is the level of community participation in solid waste management in terms of policy formulation, implementation and evaluation.

1.4 Research objectives

The aim of this research work is to assess the privatization involvement in municipal solid waste management with respect to efficiency, effectiveness, and the level of performance towards sustainable management. In order to attain this aim, the following sub-objectives have been devised.

• To assess the privatization experience in waste collection and disposal in Bahrain in terms of waste minimization disposal.

• To study the impact of including the private sector in solid waste collection for the sustainability of urban services delivery at regional and global level comparing with Bahrain experience.

• To evaluate the efficiency and quality of private companies’ services involving in solid waste collection and sorting services.

• To analyze the key factors that describe the differences in performance and service quality of private companies in the context of waste management sustainability principle.

• To review the capacity building programs that improve Bahrain’s capability to solve waste management issues and identify appropriateness of the best environmental practices and best available technology opportunities.

• To study prospects for introducing small scale businesses at the local level to make solid waste a beneficial business based on public private partnership.

• To assess the level of community involvement in solid waste management in terms of policy articulation, implementation, and evaluation.

1.5 Research significance

Since there is a finite amount of space on an island, the disposal of waste through landfills will always be risky and have a short lifespan, making it one of the primary obstacles to overcome in the waste management sector. When considering a shift from a cheap landfill solution to a more expensive Integrated Waste Solution, the price tag is often cited as the main barrier to adoption. While landfill disposal is currently economically viable, it will need more technology and so cost more in the future. Population growth, urbanisation, and rising consumer demand are all contributing to rising waste volumes, and the government cannot forever foot the bill. The opportunities for waste recycling are substantial in Bahrain, and the government is responding by establishing programmes that further the goals of the country’s National Waste Management Strategy. End-use markets are now located abroad, so recycled materials must be exported. This places a significant constraint on the waste recycling business. Eventually, landfill disposal rates will have to go up, and that will open the door for alternative recycling methods. Pre-qualification of companies is already underway for tyre recycling, and a tender for consultant work for a waste-to-energy plant including a materials recycling facility will be issued shortly, to be followed by the actual building of the facility. The Waste Strategy Plan prioritises recycling, but there are a lot of obstacles in the way. Like the majority of Middle Eastern nations, Saudi Arabia sends its recycled trash overseas rather than reusing it in its domestic manufacturing. Since waste disposal is so cheap in Bahrain and the Middle East generally, recycling programmes have nothing to gain financially.

The primary goals are landfill diversion and future-proofing waste treatment and disposal in Bahrain. This can be done via the use of alternative treatment technologies, but it is also crucial to educate the public and the commercial sector on the need of reducing their waste output through improved practises and recycling. Over 180 different policies, including legislation, recycling and composting, treatment and recovery, disposal, education and awareness, regulation and enforcement, institutional arrangements, economic framework, waste classification, waste prevention and minimization, and waste collection, are outlined in the Waste Strategy and need to be implemented over the next 20 years (short term, medium term, and long term).

During the period from 2008 to 2018, waste generation increased by 48%; the reasons lay in the increasing population growth, growing level of urbanization and development, expansion of the commercial sector, public services, and continuous industrial sector extension. The limited land of Bahrain is the main contribution to the reason for the problem. Therefore, Bahrain urgently needs to adopt and activate a national waste strategy plan to tackle the solid waste management issues. Hence, this study aims to examine and assess all aspects of solid waste management and the case of privatization to improve the privatization outcome toward the sustainability of solid waste management.

2 Waste management and privatization

The effects of solid waste on public health and the natural environment have made it clear that this is a pressing problem for metropolitan areas (Subhan et al., 2014). The world as a whole has a waste problem, but the widespread use of unsustainable methods in the management of solid waste in emerging and transition nations needs particular attention (Ferronato and Torretta, 2019). Population expansion, new product production and consumption, industrialization, and improved living standards, as well as changes in consumer habits and lifestyles, are major causes of the ever-increasing waste output in growing economies (Nabukeera, 2016). Because of this, waste disposal systems do not work as well, landfills fill up quickly, and waste management services are not as good (Nabukeera, 2016). Thus, a variety of inefficiencies, such as low collection coverage, irregular collection, pollution from uncontrolled waste, the dumping and burning of domestic waste, uncoordinated private sector involvement, and a lack of basic solid waste management infrastructure, persist in the management of solid waste in developing countries (Nabukeera, 2016; Wilson et al., 2017). Abul (Abul, 2010) says that if waste is not handled properly, it can spread bacterial infections, pollute ground and surface water, and clog air filters. Lack of resources and inadequate social and economic circumstances are other barriers to the establishment of efficient solid waste management systems (Adelayo, 2023). Despite the fact that waste management is often the responsibility of the local government, many municipalities in developing countries struggle to keep up with the growing demand for effective waste management due to limited resources (Nabukeera, 2016; Wilson et al., 2017). It is estimated that between 20 and 50 percent of municipal income is spent on solid waste management. Unfortunately, only around half to two-thirds of the population benefits from waste collection. As a result, many governments are shifting away from providing public waste management services and toward privatising them (Mohammed, 2012; Sukholthaman et al., 2017). The private sector must be involved, and authority must be devolved to the local government or city council (Post, 1999). When it comes to solid waste management, some nations choose private-public partnerships, in which the public and private sectors work together to create a strategy and divide the workload (Sukholthaman et al., 2017). Contracting, franchising, divestment, concession, and open competition are only a few of the methods that governments use to privatise solid waste management services (Post et al., 2003). Contracting and franchising are the two most popular forms of privatisation used for solid waste management, but the appropriateness of each form of privatisation for a given system differs when it comes to solid waste collection, disposal, cleaning, and transportation services. A traditional justification for outsourcing services is the potential for cost savings for the government (Greve, 2007), which may be maximised via market competition (Anderson, 2011). There are two primary points of contention on the topic of privatising waste management. The philosophy that private firms provide relatively cheaper and improved services than the public sector rests on three pillars: the existence of competition between private firms; the ability of public officials to monitor and enforce service contracts between the government and private firms; and the expectation that private companies hired under government contracts will provide public services at lower costs and with higher quality than those provided directly by the government (Anderson, 2011). One counterargument is that privatisation opens up a new market, which, if used, could lead to more competition in the private sector and better public services (Anderson, 2011). Some academics (Tukahirwa et al., 2010; Sukholthaman et al., 2017) have aligned their public-private argument towards the partnership paradigm theory, which calls for cooperation between all waste management stakeholders to increase the quantity and quality of public services beyond what is possible under purely private or purely public arrangements. Partnerships between governmental and non-governmental organisations (NGOs and CBOs) are preferred to private sector engagement in providing sanitation and waste management services to low-income urban residents. In this setup, service providers work with families who get waste management services to increase the ecosystem value by including a “voice for nature” in the service delivery process.

3 Municipal solid waste management in Bahrain

To handle municipal solid waste (MSW), the government of Bahrain has established a system in which each of the country’s five governorates has its own municipal authority in charge of MSW collection and management within its borders. Since the 1970s, when crude oil was first exploited, there has been a rapid financial modernization in Bahrain, leading to a rise in spending and a transformation in the city’s physical appearance (Hamouche, 2004). Near Bahrain, waste is collected and transported to an already operational landfill site in Manama. Total waste production in the Kingdom of Bahrain is 659,847 metric tonnes per year. When considering the population of the nation in the same year, it is estimated that each individual generates 1.4 kg of waste. Domestic waste accounts for around 45% of the total, but as the nation rapidly urbanises, business waste is also rising, as shown by (Mohammed, 2012). These rises are indicative of the challenges that may occur as the government continues to address the issues now plaguing its waste management systems.

3.1 Solid waste generation, composition, and characteristics

More than 1.2 million metric tonnes of solid waste are produced annually in Bahrain. The small Gulf country generates more than 4,500 tonnes of waste every day. The organic material in municipal solid waste is mostly made up of food scraps, and it makes up a significant portion of the waste. Bahrain’s municipal solid waste (MSW) is a strong recycling feedstock due to the high percentage of recyclables present, particularly paper (13%), plastics (7%), and glass (4%), while informal sectors are now responsible for collection of collection of recyclables and recycling operations (Zafar, 2017). There are five governorates in Bahrain: Manama, Muharraq, the Middle, the Southern, and the Northern. A small number of private companies in Bahrain are responsible for waste collection and disposal. Currently, most municipal solid waste is disposed of at the Askar landfill. Only at Askar, Bahrain’s lone landfill/dumpsite, may municipal wastes, agricultural wastes, and non-hazardous industrial wastes be disposed of. The landfill, which covers more than 700 acres, will likely hit capacity in the next several years. Major environmental concerns have been raised due to the location of the Askar dump so close to populated areas. The high rate of trash buildup is having and will continue to have terrible effects on the air, soil, and groundwater quality in the communities nearby (Shimelis, 2011). Waste management issues plague the Kingdom of Bahrain due to its expanding population, rapid industrialization, excessive waste production per inhabitant, disorganised solid waste management (SWM) sector, limited land availability, and low levels of public awareness (Thanh et al., 2010). The government is making significant efforts to better manage waste by introducing recycling programmes, a waste-to-energy project, and a public awareness campaign (Freije et al., 2015). A sustainable waste management system in Bahrain, however, requires more work from all parties involved in the form of efficient laws, substantial expenditures, the implementation of cutting-edge SWM technology, and environmental consciousness (Karak et al., 2012).

Decomposition and biodegradation of waste at high temperatures cause unpleasant odours, insect and rodent populations to boom, unwanted major and minor fires to break out, soil and water to be contaminated by leachate from landfills, and toxic gases to be emitted during waste disposal, burning, and incineration. Emissions of methane and carbon dioxide from MSW are also major contributors to global warming. Other significant effects include disruptions to both terrestrial and marine ecosystems; increased traffic, road congestion, accidents; increased dust and noise; nuisance; bird hazards; risks to worker health; increased litter production and spread; and a decline in the visual appeal of the surrounding area. Vermin like flies, rodents, and other insects are drawn to garbage and may transmit illness. It is important to realise that the government cannot tackle the MSW issue by itself. We must all do our part to reduce waste production, collect all trash for proper disposal, sort recyclables from nonrecyclables, and educate others about the need for eco-friendly waste management (Sharma and Jain, 2020). Waste management efficiency is reliant on the population’s knowledge of the issue and its desire to adjust its wasteful ways of thinking and behaving. Reducing trash at its origin, or source, is an effective waste management strategy. Grass recycling and backyard composting are two examples of sustainable practises that may have a major impact. Many greenhouse gases are avoided, pollution is decreased, energy is saved (Blanchard et al., 2020), resources are preserved, and the demand for landfills is significantly cut down (Jassim et al., 2019; Coskuner et al., 2020; Coskuner et al., 2021).

3.2 Waste collection, transportation and disposal

Nidukki, based in the Kingdom of Bahrain, has been operating for more than 30 years, during which time it has become a leader in the waste management, cleaning, and recycling industries. The firm has commercial and public-sector clients all throughout the island, and its services include a wide range of waste types (solid, liquid, industrial, hazardous, and general). Since recycling facilities have not yet been established in the country, waste management in Bahrain mostly entails moving trash from one location to another (Mohamed et al., 2009). Nidukki mostly serves gated neighbourhoods, commercial businesses, and factories. The municipal contracts are tendered by the ministry of works and municipalities, and the residential contracts are structured so that one contractor is responsible for all the standard public residential areas and another contractor is responsible for the gated residential developments and is interested in servicing the gated communities. To back up their services and ensure maximum efficiency and productivity, the firm operates a fleet that includes vacuum tankers, skip trucks, compactor trucks, dump trucks, combination trucks, mechanical road sweepers, transportation vehicles, diesel tankers, and light vehicles. Nidukki also provides on-site scrap collection services and collects various types of paper and plastic. Their goal is to expand their presence in this area and benefit from their primary concentration on Bahrain. They began as a waste transportation company, but in 2006 branched out to provide hydro jetting and drain cleaning services. They started a recycling company in 2012.

Gulf City Cleaning Company (GCCC) is another company operating in the island nation of Bahrain. GCCC provides a variety of services, including trash management, to customers all throughout the country. The company offers a variety of different services, such as garbage pickup for homes and businesses, transportation of hazardous waste, drain cleaning and maintenance, and skip rental. After Manama, Muharraq, and Hidd, Bahrain’s municipal governments awarded GCCC the contract to collect waste, clean streets, and empty septic tanks in the year 2000, the company officially came into being. This was one of the first and most successful “turnkey” privatisations in the GCC. GCCC has been in business for 18 years and has grown to become a major player in the market for cleaning and waste management services; the company is now expanding into other GCC countries through joint ventures. The organisation uses state-of-the-art machinery and transportation. Their waste collection vehicles are equipped with a GPS system that relays real-time data, which has increased efficiency, decreased wasted time, and decreased overtime expenses (Indrupati and Henari, 2015). RFID tags improve the efficiency, timeliness, and accuracy of data collection (Al-Jubori and Gazder, 2018). The “recycling bin allocation app” was created by GCCC as part of an effort to help locals who are serious about sorting their waste at the curb find the most convenient place to leave their recyclables. They have also organised massive cleanup operations and created in-depth education programmes for schools (Abbas et al., 2020).

According to the latest statistics, most waste is now being dumped in landfills. The country’s general and industrial non-hazardous waste goes to one landfill, while hazardous solid and liquid waste are disposed of in the other. There are several STPs around the nation where sewage and light industrial waste are processed (Zafar, 2018). In 2016, there were 1,448,685 tonnes of solid garbage created (from sources such as homes, businesses, farms, and factories). Daily, Bahrain generates 380 tonnes of industrial garbage, 7 tonnes of medical waste, and 5,500 tonnes of municipal waste, most of which is food scraps. However, work is being done to institute the necessary steps to address the issue. There is talk of a new national waste plan that would try to reduce the amount of trash sent to landfills. With regards to recycling, Bahrain is “only scratching the surface” at the moment, with just a handful of recyclers operating. Two test projects with municipal contractors have been initiated by the government. One contractor is leading the way on a pilot project for construction and demolition debris, while the other is hard at work on composting. Furthermore, a prequalification tender for tyres has been released. Now that the plan is coming together, the next step is to put it into action.

4 Waste management regulations and institutions in Bahrain

The production of waste and the problems it causes for humans and the environment are universal concerns. Garbage management presents unique challenges, particularly in developing countries, due to the increasing complexity of waste composition and the rising volume of waste produced per person. The multi-level governance structure that comprises waste management includes national, regional, and, most often, local governments, each of which is responsible for developing strategies, national plans, regional policies, and local instruments for trash collection, treatment, and disposal. Government policies, like taxation and subsidy programmes, are crucial to the growth of this industry and the promotion of innovative technologies that may otherwise struggle to succeed (Al Sabbagh et al., 2012).

The principles of “reduce, reuse, and recycle” (3R) and waste management are widely acknowledged as the foundation upon which a society based on “material cycles” might be built (Yoshida et al., 2007). The European Union’s (EU’s) Waste Framework Directive (2008) serves as the bloc’s foundational waste management law. Individual EU member states have enacted their own waste management statutes under this directive. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is revising its EPA Strategic Plan right now. The proposal proposes making resource management the government’s top priority in order to cut greenhouse gas emissions. In 2016, India revised its waste management regulations to include a circular economy and resource optimization. In 2005, China also revised its law on preventing and controlling environmental pollution via the use of solid waste. It pioneered the use of three-resource-reuse (or 3R) laws for garbage, sewage, and toxic waste. Any nation’s waste management needs an all-embracing strategy for continuous development if it is to ensure its citizens’ health and safety. There is a portfolio of technology and solutions that might be used, but they will not be effective without dependable economic, political, and legal backing. Trash management will improve as a result of the circular economy in this area, which includes the safe reuse and resource recovery of waste and energy neutrality. Effective waste management has been linked to a country’s commitment to sound policy. Dead animals, buildings, industries, businesses, households, food, gardens, and liquids all contribute to the wide variety of waste produced in the Kingdom of Bahrain. It is plausible to assume that landfill waste management will not be an option in light of the increasing complexity and volume of waste generated. Based on what they found, Al Sabbagh et al. (Al Sabbagh et al., 2012) came to the conclusion that Bahrain makes a lot of waste but does not have a good recycling and waste material recovery system to match. They also found that the public is not very aware of how to manage waste properly, and that local government institutions do not do much to get the public on board.

Preventing waste from being dumped anywhere in Bahrain serves as an efficient land protection measure. There was a need for a policy on the use of agricultural chemicals in the agriculture development sector (fertilizers and pesticides). Materials and wastes that, either on their own or when combined with other wastes, pose a threat to human health, animal welfare, or environmental stability as a result of their composition (e.g., toxic substances, the potential to burst and corrode, etc.). These hazards can be the result of industrial processes, chemical reactions, or radiation (Mohamed et al., 2009). In order to reduce environmental contamination and lessen its effects, this was supposed to be managed by international laws on its safe usage. Consistent efforts have been made in Bahrain to increase the amount of land that can be farmed, the quality of the land that can be farmed, the amount of water that can be farmed, the yield per hectare, and the efficiency with which water can be farmed (Blanchard et al., 2020). The ability to establish fresh Industrial Symbiosis partnerships in waste and wastewater management is frequently hindered by several non-technical obstacles. These challenges encompass environmental regulations, insufficient collaboration and trust among industrial systems, economic and legal constraints, and notably, a lack of awareness regarding the potential benefits that could be attained (Mancini et al., 2021).

One of Bahrain’s most serious environmental issues is how it handles waste from both households and factories. Both sorts of waste are generated at a tremendous rate. The location, located far from populated regions, serves only as a landfill for municipal solid waste. Handling, collecting, and transportation of waste are only a few areas that have benefited from advances in waste management. Regular monitoring of landfill sites helps to reduce potential risks to public health. At the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), Bahrain was only one of several countries present. It emphasised the need to integrate environmental protection with sustainable development.

Bahrain is committed to protecting the environment and conserving natural resources while pursuing its ambitious national development goal. Incorporating the Sustainable Development Goals 2030 (SDGs) established by the United Nations General Assembly into its Government Action Plan and Economic Vision 2030, the Kingdom has achieved tremendous progress in these areas (Elimam, 2023). In addition to the environment, sustainable resource management, urban development, water and energy, transport, urban expansion, waste management, marine conservation, and biodiversity are all addressed in Bahrain’s Economic Vision 2030, which is guided by sustainability as one of three principles. Various government agencies, boards, and commissions have been set up in the Kingdom with the express purpose of formulating plans for achieving sustainability across all of its many aspects. Additionally, it has passed a number of laws and rules aimed at promoting sustainable development. Despite the difficulties faced by the international community in the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak, Bahrain has signed multilateral accords relating to sustainability and is continuing to meet its obligations to them (Buong, 2020).

5 Bahrain waste management strategy

It is generally agreed that waste management for municipal solid waste should follow a waste hierarchy strategy that prioritises resource conservation and recycling above disposal (Zafar, 2018). The circular economy strategy goes further than the waste hierarchy by encouraging the development of products that do not create waste, the use of products and materials for longer, and the reintroduction of recycled resources. The Kingdom of Bahrain has received two proposals in response to its request for proposals seeking a consultant to evaluate the effectiveness of the 2018 version of the National Waste Management Strategy (NWMS) (Alsabbagh, 2019). On 4 July 2022, the Bahrain Tender Board announced that it had issued a tender for consulting services to assess the country’s waste management plan. In terms of technical proposals, both Roland Berger Middle East and KEO International Consultants have put themselves forward. According to the Minister of Works, Municipalities, and Urban Planning, the waste issue in the kingdom would be alleviated in the long term due to the execution of the National Waste Management Strategy (Phillips, 2010). According to a “Bahrain News Agency report,” the Works Ministry has made significant progress in putting the strategy’s practical ideas into action. An estimated 1.7 million tonnes of waste end up at the Askar landfill every year, but according to these measures, half of that quantity is now being processed. The strategy’s overarching goal is to fulfil the Kingdom of Bahrain’s promises in the area of “integrated management,” or the coordination of various waste management activities—from collection to sorting to management to awareness-raising and beyond—using the most effective methods available worldwide in terms of health, the environment, and technology (Wilson et al., 2015). As part of the strategy’s implementation, the ministry is focusing on three core projects: For starters, 38% of all waste sent to landfills may be recycled; this comes mostly from the building and demolition sector (646,000 tonnes per year). A call for bids was issued, and the contract to carry out the plan was ultimately given to a business in the area. The effort has helped increase the availability of recycled materials for road construction. The first roadway built entirely from recycled materials was completed by the ministry. Second, we are trying to find new uses for the approximately 300 tonnes of green waste produced every day (which accounts for around 7% of total waste). This endeavour, located in Hoorat A’ali, will be carried out by the Works Ministry. The private sector will be granted the project, which would transform garbage into agricultural fertiliser. The third plan, he added, involves turning garbage into useful energy, and the government is now hiring a consultant to be ready for the contract. The government is also getting ready to issue a request for proposals for tyre recycling. The Askar landfill will be developed over 3 years by the Spanish firm Urbaser, according to a deal signed earlier this year by the Ministry of Works, Municipalities Affairs, and Urban Planning.

6 Municipal solid waste management and sustainable development goals

Waste from homes and businesses accounts for the bulk of what is known as “municipal solid waste,” which is primarily the responsibility of state and local authorities. Waste that is collected and processed by or for a municipality is known as municipal solid waste. It includes waste from homes, especially large items like furniture and appliances, as well as waste from stores, offices, and other commercial buildings, as well as waste from streets and sidewalks, public spaces, and trash cans.

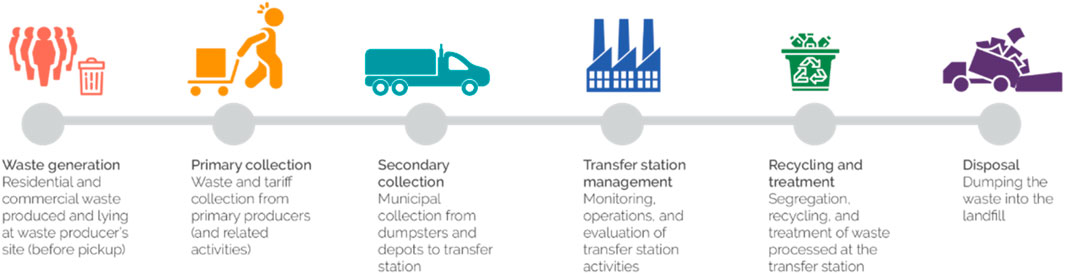

There are six steps to managing municipal solid waste (MSWM): waste generation, primary collection, secondary collection, transfer station management, recycling and treatment, and final disposal. Primary collection occurs often at the point of generation for both residential and commercial waste. Afterwards, it is transported by secondary collection to a transfer station, where it is sorted and either composted, recycled, or treated before being sent to a landfill that is under strict environmental supervision. Biological or thermal treatment, including incinerators, may be used to convert waste to energy for treatment or recovery (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Municipal solid waste management process (Bank, 2022).

Different aspects play different roles in MSWM. Both households and businesses generate and benefit from municipal solid waste collection and disposal services. Central and regional governments conduct policy formulating and regulatory roles and offer supplemental financial assistance, while local governments are the primary sources of municipal solid waste finance and service supply. The informal waste picker community plays a crucial role in the collection and recovery of recyclable and reusable materials, and civil society and nonprofit groups work to promote awareness about MSWM, keep service providers responsible, and assist this group. Extended producer responsibility, in which producers take full legal and financial responsibility for the disposal of their goods, is one example of a practise that might benefit from private sector investment, efficiency, and innovation. Wherever official services fall short, the informal sector (i.e., rubbish pickers) steps in to fill the void. Air, land, and water pollution all occur as a result of insufficient MSWM, which has negative effects both locally and globally. Poor MSWM has far-reaching consequences at the community level, negatively affecting the quality of life for low-income individuals in the areas of the environment, society, and economy. In the grand scheme of things, it aids in the acceleration of global warming and the proliferation of plastic waste.

The health and quality of life of a population suffer when MSWM is inadequate at the local level. The pollution of land, air, and water and the attraction of disease vectors that result from improper waste management and the open dumping and burning of municipal solid waste People living or working in low-income areas are disproportionately affected by improper waste management because they are more likely to live near or work at trash disposal sites, which may lead to flooding that produces filthy and poisonous conditions (Giusti, 2009). Pollutants in the air and small particles that come from trash fires have been linked to a number of health problems, including ones with the respiratory and nervous systems (Thompson, 2018). Poor MSWM performance also adds to global warming. Landfills and open dumps account for about 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, but waste can be a resource and a net sink for greenhouse gases if properly recycled and reused (De La Barrera and Hooda, 2016).

The effects of plastic pollution in the ocean and rivers on ecosystems and human health and livelihoods are especially severe. Estimates put the annual cost of plastic pollution in the ocean at $13 billion, with the overall natural capital cost of plastics in consumer products rising to above $75 billion (Independent Evaluation Group, 2021). If current trends continue, the amount of plastic entering the oceans across the world would almost quadruple by 2025. About 80% of marine debris comes from land, with 75% coming from MSWM systems that do not work well (Fletcher et al., 2021).

Millions of people throughout the globe rely on collecting, recycling, and selling useable garbage for a livelihood, but they have a poor social position, work and live in awful circumstances, and get little help from their local governments. Worldwide, it is estimated that 24 million people work in the informal economy as rubbish pickers, the most majority of whom live in underdeveloped nations but also some wealthy ones (Marello and Helwege, 2018). Public benefits from the increased percentage of recyclables recovered by informal waste pickers compared to the official industry are substantial despite the fact that these workers are compensated little and endure hazardous working conditions. In the informal economy, women and children play an outsized role yet face unique risks to their health and safety (Leal Filho et al., 2021).

Compared to other municipal services, MSWM receives far less attention from multilateral development agencies and private investment. The International Solid Waste Association reported that between 2003 and 2012, only 0.32 percent of all official development financing went toward solid waste (Lerpiniere et al., 2014). MSWM received between 0.5 and 6.1 percent of total urban sector pledges from Asian Development Bank, African Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and Inter-American Development Bank from 2010 to 2020. Based on statistics from the Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility, in 2020, private investments in MSWM totaled $1 billion, while investments in water supply and sanitation totaled $4 billion. All of the private MSWM funding went to UMICs. There is no global organisation promoting a unified strategy in the municipal solid waste industry. In contrast to other urban sectors, solid waste management lacks a worldwide coordinating framework (such as water supply, sanitation, transport, and energy). The Global Partnership on Waste Management was set up in 2010 and was the only organisation of its kind to focus on waste management. Since then, it has stopped working without having done anything important.

In order to achieve green, resilient, and inclusive development, MSWM is essential for achieving SDG 11 on sustainable cities and achieving SDG 12 on waste reduction (and is pertinent to concerns addressed by other SDGs). Service delivery for waste management is directly addressed in SDG 11 for sustainable cities, and prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse are directly addressed in SDG 12 for reducing waste generation (Eller et al., 2021). These are essentially the elements of the waste hierarchy approach to MSWM described in the following paragraph. Other SDGs aim to reduce plastic pollution in the ocean, improve the lives of people who pick up trash for a living, make MSWM more effective in fighting climate change, and more (Ferronato et al., 2019).

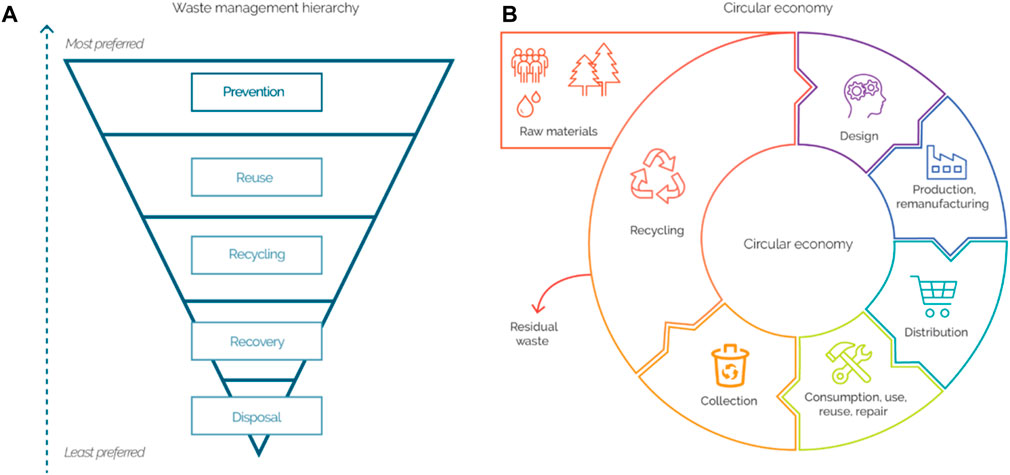

The waste hierarchy is a well-known strategy for the responsible and long-term disposal of trash. Usually, the waste hierarchy is shown as a reverse pyramid, with the most desirable methods of MSWM at the top and the least preferred at the bottom (Figure 4, panel a). In this formulation, reducing consumption and increasing source reduction and reuse are chosen over recycling, which is preferred over recovery (such as waste to energy, composting, and incineration), which is preferred over ecologically responsible disposal (usually in sanitary landfills). How far each country has moved up the waste hierarchy, from less acceptable to more acceptable methods, varies a lot.

FIGURE 4. The waste hierarchy and the circular economy (Bank, 2022). (A) Stages of waste hierarchy and (B) Illustration of the Circular Economy with its different components.

When compared to the conventional linear (take-make-dispose) economic model, the more comprehensive circular economy approach is more environmentally friendly. The circular economy promotes waste-minimization via product design, prolonged product and material use, and the reintroduction of recycled resources (Figure 2.2, panel b). For the transition to a circular economy to be successful, consumers must insist that producers take full legal and financial responsibility for their goods’ disposal. The independent Circularity Gap Report 2021 states that just 8.6 percent of the global economy is circular, resulting in a waste rate of 91.4% (Regueiro et al., 2021).

7 Municipal solid waste management privatization

The tiny size of Bahrain means that the nation has a very small amount of land available for waste disposal facilities, which is one of the main contributing factors to the difficulty of dealing with the country’s rapidly expanding waste issue. This has led to calls for privatising the country’s municipal and solid waste services (Read, 1999). Properly handling waste is seen as one of Bahrain’s most pressing problems. Residential, commercial, building and demolition, industrial, and agricultural waste have all seen considerable increases over the last 30 years, according to data collected across all of these sectors. The small size of Bahrain means that the nation has a small amount of land available for waste disposal facilities, which is one of the main contributing factors to the difficulty of dealing with the country’s rapidly expanding waste issue. Therefore, there is a pressing need to privatise municipal and solid waste operations throughout the nation. It was in the year 2000 that a feasibility study regarding outsourcing waste collection services was undertaken by the Central Municipal Council, as it was then known before it was split into four independent municipalities. Services deemed to be in the best interests of the nation might be outsourced at that time under government policy. “Provide better service at a reduced cost” was the stated goal. The choice to hire outside help was influenced by a number of considerations. Vehicles were kept in service much beyond their economic life due to the infrequent allocation of capital expenditures for fleet renewal. Due to the aforementioned Government bidding procedures and pressure from local suppliers, garage prices were rising, resulting in a fleet of cars that was not uniformly well-suited to the task and hence required the stockpiling of spare parts for a wide variety of makes and models. Each time a bid was put out for new automobiles, a different manufacturer’s chassis and body styles would make their debut. Difficulties in accommodating, transporting, paying, and managing a growing expatriate workforce. Since most of the employees resided in privately rented homes spread out over the nation, the municipality had trouble getting everyone together for morning meetings on time. As a result, drivers, workers, and city inspectors are all overworked as a result (Soós et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2017).

8 Privatization as a private sector in the context of sustainable development goals

Quite a few communities still provide waste and recycling pick-up to residents in single-family homes. The private sector, however, has been the go-to for most communities because of its cheaper prices and more reliable service. The majority of waste management is handled effectively by the private sector. They also run transfer stations, recycling facilities, composting facilities for yard and food wastes, and disposal facilities, in addition to collecting trash, recyclables, and compostables. Privatization is a good option because it helps governments save money, reduce their exposure to risk, improve their safety records, adopt better technology more quickly, and take on less debt (Zaidan et al., 2019).

Investment, environmental protection, and procurement expenses may be spread over numerous contracts and sites, allowing private enterprises to take advantage of economies of scale (El-Kholei et al., 2020). General liability and environmental compliance are normally the responsibility of the commercial partner in a government contract. Standard contractual arrangements that reduce government risk include financial guarantees and insurance coverage requirements (Al Naimi, 2022). Assuming and managing commodities market risk in the recycling industry is best left to the private sector, which has more experience and expertise in doing so than government authorities (Khayati, 2023). Alternative fuel vehicles, single stream collection of recyclables, new truck technology, and computer systems to monitor and more effectively manage the collection fleet are all examples of innovations driven by the private sector’s ambition to enhance services, cut costs, and boost safety (Faradova, 2020). When it comes to upgrading or replacing machinery, as well as deploying assets like collection trucks to optimise routes, the private sector often has greater access to funds than many local governments. Moreover, the private sector is more likely to create incentive systems for workers and managers to achieve high performance levels while keeping employees safe and promoting personal responsibility for maintaining their equipment (Alawadhi, 1999). Therefore, it is expected that private enterprises will have far less vehicle downtime than public operations do. So, privatization has great benefits like: Municipalities may save money and boost efficiency by outsourcing their waste management to the private sector. As a result, governments are free to devote more of their limited funds to essential services like recycling education, emergency response services, schools, and roads. Privatization has the potential to reduce government debt while increasing safety, efficiency, and resilience to market fluctuations. When a city or town wants to outsource its solid waste services, it uses a bidding process to encourage competition among private waste companies. This leads to low prices and good work.

9 Research methodology

Waste management is a critical and multifaceted challenge faced by nations worldwide, requiring comprehensive strategies and sustainable solutions to minimize environmental impact and ensure public health and safety. Bahrain, a dynamic island nation in the Arabian Gulf, is no exception to the global waste management concerns (Zaidan et al., 2019). As urbanization and industrialization accelerate, so does the generation of waste, posing significant challenges for the local authorities and communities alike. Understanding the complexities of waste management in Bahrain demands a rigorous and systematic research methodology. This research aims to delve into the intricate web of waste generation, collection, treatment, and disposal practices in the Bahraini context. By comprehensively investigating the existing systems, identifying gaps, and proposing innovative solutions, this study endeavors to contribute valuable insights to the enhancement of waste management strategies in the nation. The efficient management of waste is a vital component of any modern society, impacting not only public health and environmental sustainability but also economic growth and social wellbeing. In the context of Bahrain, a progressive nation witnessing rapid urbanization and industrialization, waste management has emerged as a significant concern. Moreover, the dynamic landscape of waste management practices is intertwined with the ongoing privatization initiatives in the country. This confluence necessitates a focused and systematic study to understand the intricate relationship between waste management and privatization in Bahrain (Khayati, n. d.).

The rationale for delving into the research on waste management and privatization in Bahrain is grounded in the intersection of economic policy, environmental conservation, and public welfare. The privatization of waste management services has become a global trend, aiming to enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and introduce innovation. Bahrain’s foray into privatization in various sectors, including waste management, raises pertinent questions regarding the impact on service quality, environmental sustainability, and equitable access.

9.1 Study area and research design

The research design for this study on waste management and privatization in Bahrain is structured to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the interrelation between these two critical facets. Qualitative methodology is employed to capture a holistic view of the subject matter. Qualitative methods are employed to explore the diverse perspectives, attitudes, and experiences of key stakeholders involved in waste management and privatization in Bahrain. Semi-structured interviews are conducted with government officials, representatives from private waste management companies, environmental experts, community leaders, and activists. These interviews facilitate an in-depth exploration of nuanced issues such as policy decisions, implementation challenges, community engagement, and environmental concerns related to privatized waste management services. Additionally, focus group discussions are organized with members of the local communities to gather qualitative insights into their experiences with privatized waste management services. These discussions allow for a collective understanding of public opinions, preferences, and concerns regarding the quality and accessibility of waste management services provided by private entities.

Ethical considerations are paramount in this research. Informed consent is obtained from all participants involved in interviews, focus group discussions, and surveys, ensuring their voluntary participation and confidentiality. The research adheres to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and anonymity of the respondents. Moreover, the study is conducted with respect for cultural sensitivities and local norms prevalent in Bahrain.

Qualitative insights provide depth and context and enable a multifaceted exploration of waste management privatization in Bahrain. By employing this comprehensive research design, the study aims to unravel the complexities and nuances of waste management privatization, contributing valuable knowledge to both academic discourse and practical policy-making processes in the Kingdom of Bahrain.

9.2 Data collection, sampling, and analysis

Data were collected from municipal authorities, and Gulf City Cleaning Company as private company.

Interview Process.

• Interviews are scheduled at the convenience of the participants.

• Open-ended questions are used to encourage detailed responses.

• Probing techniques are employed to explore specific topics in depth.

• Audio recordings and detailed notes are taken to ensure accurate transcription and analysis.

Focus Group Discussions:

Focus group discussions are organized with members of local communities, encompassing residents, environmental activists, and representatives from non-governmental organizations. These discussions aim to capture collective opinions, shared experiences, and diverse viewpoints related to privatized waste management services. Focus groups facilitate interactive dialogue, allowing participants to respond to each other’s ideas, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of community perspectives.

Focus Group Process.

• Focus groups are conducted in community centers or other accessible venues.

• Moderators guide discussions using a predefined set of open-ended questions.

• Participants are encouraged to express their thoughts and respond to others’ opinions.

• Sessions are recorded and transcribed, capturing the dynamics of the discussion.

Both the municipality and Gulf City Cleaning Company were interviewed using separate questionnaires. Questions asked in this municipal interview guide centered on the bidding process, the composition of service providers in the relevant municipality, monitoring concerns, and the existence of by-laws and regulations governing solid waste management. In addition, the public’s failure to pay the user fee, the private sector’s performance, the efforts put in place by municipal authorities to help the private sector, and the role of municipal authorities in the management of solid waste by private sector providers all came up as topics of discussion. Human resources, municipal budgets and expenditures, and any existing initiatives to improve the capacity and efficiency of solid waste management in the municipalityThe interview questions for Gulf City Cleaning Company centered on the company’s background, the services they provide, the company’s operations and infrastructure, the environmental effects of sustainability, the company’s issues, and the possibilities it faces.

To enhance the credibility and reliability of qualitative data, the process of member checking is employed. This involves sharing summarized findings with participants, allowing them to validate the accuracy of the information provided. The collected qualitative data undergoes thematic analysis, identifying recurring themes, patterns, and divergent viewpoints.

Qualitative data analysis for the study on waste management and privatization in Bahrain involves a systematic and iterative process to extract meaningful insights from the rich textual data collected through interviews and focus group discussions. The analysis aims to identify patterns, themes, and contextual nuances, providing a deep understanding of stakeholders’ perspectives and experiences related to waste management practices and privatization strategies.

Interviews and focus group discussions are transcribed verbatim. Transcriptions provide a written record of the qualitative data, facilitating easy access and analysis. Researchers immerse themselves in the data by reading and re-reading the transcriptions. This step enhances familiarity with the content and context, aiding in the identification of initial patterns and themes.

9.3 Muncipility authorities

9.3.1 Tendering procedure

For municipal solid waste, the Ministry has divided the country into two contracts: Capital Muharraq and North South. For other waste, such as tire recycling, construction waste, and green waste, there are separate tenders. Tenders are issued every 7 years. Criteria are used to select service providers, which is done through a strict pre-qualification process based on financial stability and technical experience.

9.3.2 Service providers

There is one provider for Capital Muharraq and one for North South. These service providers have been operating in the municipality since June 2016. The Ministry has a Performance Manager system in operation, indicating an excellent performance record of the private sector to date. The public does not pay a fee. The cost of the contracts is paid by the Ministry of Finance.

9.3.3 Monitoring

The monitoring mechanisms are in place to ensure that the private sector is providing high-quality services through an app-based performance management system to ensure the services are being done properly. Teams of inspectors are working daily to monitor the services. The Performance Manager system incorporates automatic penalties for non-compliance.

The Cleaning Laws of 2019 are regulations and by-laws that exist to guide solid waste management in the municipality.

9.3.4 Municipal support for private sector

For construction and demolition (C&D) recycling and composting, the land is being provided. The National Waste Strategy lays out 180 policies to improve the capacity and efficiency of waste services.

9.3.5 Human resources and budgets

Currently, the annual cost of waste collection, street sweeping, recycling, septic tanks, etc., Is in excess of 22 million Bahraini dinars per year. These funds are allocated directly from the Ministry of Finance to the companies on a monthly basis. There are over 3,000 workers in the two cleaning companies.

9.4 Gulf City Cleaning Company

The main business activity of the company is waste management and collection. The company has been involved in solid waste management in Bahrain for 21 years.

9.4.1 Service provided

Collection, Transport, and Recycling are types of solid waste management services that company provide in Bahrain. The company covers the Capital and Muharraq areas for solid waste management services in Bahrain. Domestic commercial industrial construction and hazardous waste are types of waste that the company handles. The company collects and handles 500 tons of waste per day. The company collects and disposes of the waste through rear-end loaders, six-wheelers, open trucks, skips, 1100-L bins, and 240-L bins.

9.4.2 Operations and infrastructure

The company has 50 waste collection vehicles, and the capacity of waste collection vehicles is 15 tons. Also, waste collection vehicles operate daily. It handles hazardous waste in Bahrain only for collection and transport to the SCE landfill. The company does not have a waste segregation system in place and does not have a waste treatment or processing facility in Bahrain.

9.4.3 Environmental impact sustainability

There are steps the company has taken to minimize the environmental impact of its solid waste management activities in Bahrain, like implementing waste reduction and recycling programs to minimize the amount of waste sent to landfills. Promoting public awareness and education campaigns on waste management and environmental conservation, Collaborating with local authorities and stakeholders to develop sustainable waste management strategies; investing in research and development of innovative waste management solutions to minimize environmental impact. Company implements waste reduction or recycling initiatives, which currently have 3 initiatives in 40 locations in both capital and Muharraq. East hidd 11 locations, nabih saleh 10 locations. Steps the company takes to ensure that its solid waste management activities are sustainable, like implementing waste management practices that prioritize waste reduction, recycling, and resource recovery, and collaborating with local communities and stakeholders to develop sustainable waste management strategies and providing awareness lectures and workshops to schools and clubs.

9.4.4 Challenges and opportunities

The main challenges that the company faces in providing solid waste management services in Bahrain stem from limited public awareness and participation in waste segregation and recycling practices, nsufficient infrastructure for waste collection, transportation, and disposal, inadequate funding and financial resources for implementing advanced waste management technologies, limited availability of suitable landfill sites and challenges in obtaining necessary permits and approvals.

There are many opportunities for the company in Bahrain’s solid waste management sector in the future. These include expanding recycling and waste-to-energy programs, working with the government and private companies to create new waste management strategies and technologies, combining smart waste management systems with digital technologies to make them more efficient and easier to keep an eye on, and introducing.

10 Bahrain as the study focus

Bahrain was selected as the focus of this study on waste management and privatization due to several compelling reasons.