- 1School of Environment and Sustainability (SENS), University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

- 2Instituto Boliviano de Investigación Forestal (IBIF), Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Santa Cruz, Bolivia

- 3Nación Monkoxi del Territorio de Lomerío, Santa Cruz, Bolivia

Indigenous territories cover more than one-fourth of the world’s land surface, overlap with distinct ecological areas, and harbour significant cultural and biological diversity; their stewardship provides critical contributions to livelihood, food security, conservation, and climate action. How these territories are accessed, used, and managed is an important question for owner communities, state governments, development agencies, and researchers alike. This extends to how broad community memberships remain invested in territorial use and management, with young people comprising one sub-group often underrepresented in decision-making spaces. We know that internal community norms and structures–often dominated by older, adult males–can limit opportunities for youth to contribute their energy and ideas. We also know that youth can and do leave their home communities to pursue life, work, or education goals and aspirations. Drawing on insights from 5 years of collaborative research with the Indigenous Territory of Lomerío (ITL), Bolivia, we explore the roles that youth play in territorial governance, their perceptions of current structures and novel engagement strategies, and consider what lessons from this case could be applied more broadly. Our findings point to the ITL as an instructive example of how Indigenous (and other rural and remote) communities might enable young people to participate more fully in territorial governance, highlighting the importance of an enabling, underlying socio-cultural context. Based on our work in Bolivia, and lessons from other places, we discuss ways to enhance youth-community-territory linkages to support Indigenous land sovereignty and stewardship and reflect on how research co-design and knowledge co-production can help deliver more robust, inclusive, and useful (in an applied sense) empirical insights in support of such efforts.

1 Introduction

Globally, over 476 million people (6 per cent of the world’s population) identify themselves as Indigenous (ILO, 2019). Through their land stewardship, Indigenous Peoples have made important contributions to addressing the global challenges of mitigating and adapting to climate change, conserving biodiversity, and attaining sustainability (Garnett et al., 2018; Howitt, 2018; Schuster et al., 2019; Fa et al., 2020). While Indigenous Peoples comprise only a small percentage of the global population, their customary territories are estimated to span a quarter of the world’s land surface (Garnett et al., 2018), covering distinct ecological areas and landscapes (Fa et al., 2020). These territories can contain equal or higher biodiversity than government-run protected areas in the same regions (Duran et al., 2012; Porter-Bolland et al., 2012; Schuster et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2020), and offer cost-effective natural climate solutions (Griscom et al., 2017; RRI, 2018). With the “taking care” of relations (with the natural world) (see Hernandez, 2022) central to their value system and worldview, the role that Indigenous Peoples play in environmental management and conservation has garnered attention across international fora, frameworks, and legal instruments (Dawson et al., 2021)—from the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, and, most recently, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework–and focused attention on the devolution of rights to support Indigenous territorial sovereignty (Blackman et al., 2017; Paneque-Gálvez et al., 2018).

Yet it also stands to reason that the potential of Indigenous Peoples to continue or enhance their environmental stewardship efforts will depend on how they access, use, and self-govern customary territories into the future. Across global regions, most such territories are traditionally managed as commons, defined by Ostrom (1990) as collective resources administered through community-derived rules and norms, which “owner” communities sustain by navigating a myriad of collective action challenges; from securing (and defending) land tenure (a major incentive for self-organization) to reconciling rights over existing claims, addressing legal overlaps, managing the impacts of market integration, and building equitable governance institutions (Assies, 2006; Monterroso et al., 2019). On this latter issue, we know that legitimate governance delivers more effective commons management than tenure ownership alone, and legitimacy requires broad participation in decision-making (Larson et al., 2023). This, in turn, will require customary norms and institutions to adapt to changing socio-demographic, economic, and environmental realities (Robson et al., 2019a).

Making territorial governance democratic, socially inclusive, and representative means giving voice to and building capacity among a broad swath of community members, across a diversity of ages and genders. Youth1 constitute one of the groups within Indigenous communities often underrepresented in local institutions and governance structures (Robson et al., 2020; Brown, 2021). At the same time, the number of Indigenous youth is on the rise globally (UNDESA, 2017; IFAD, 2019), part of a broader ‘youth bulge’ with the potential to underpin future rural economic growth and development (ADB & Plan International, 2018; Clendenning, 2019). However, while different levels of government are tasked to find ways for young people to contribute more (IFAD, 2019), the fact that youth are not central actors in the rural sphere (UNDP, 2015; IFAD, 2019)—they often lack influence or power (Salter, 2022) through being excluded from the decisions that impact their lives (Cahill, 2007)—could prove a major barrier to Indigenous territorial governance over time. Similarly, the degree to which Indigenous youth may be brought into the fold will be shaped by the customary norms embedded within their home territories, which can vary across communities and regions, as attested to by work in Latin America (Monterroso et al., 2019). And as they continue to be ostracized or left out of such structures, young people have fewer motives to stay in their communities of origin (Zurba and Trimble, 2014; Deotti and Estruch, 2016; Robson et al., 2019a); a real concern since rural out-migration tends to weaken the social cohesion, traditional knowledge, and collective action that underpin management of territorial commons (Ostrom, 1990; Robson, 2010; Lira et al., 2016), with youth the demographic set to assume responsibility for managing such shared lands, forests, and other natural resources (ECLAC, 2018; Macqueen and Campbell, 2020).

It is of little surprise then that ‘youth engagement’ has become a priority among community leaderships (as reported in Robson et al., 2019a; Robson et al., 2020), and part of the contemporary rhetoric of international development frameworks (UN, 2018; UNDESA, 2018), including the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. However, while better integrating young people into community processes is widely espoused (and not just within Indigenous contexts), little is written about how such efforts are best envisioned and undertaken to be meaningful and empowering (to youth) (Brennan and Barnett, 2009) rather than symbolic or tokenistic–where young people are apparently given a voice but have little or no choice about the subject or the style of communicating it, and little or no opportunity to formulate their own opinions (Hart, 1992). The danger is that when engagement is piecemeal, youth are further alienated from, rather than invested in, community institutions and processes (Pritzker and Metzger, 2011), youth-oriented interventions can be founded on unsubstantiated claims and assumptions (UNDESA, 2018; IFAD, 2019), and youth are not given the opportunity to drive forms of social change (Ginwright and James, 2002). Conversely, when youth feel represented, emergent local policies are more likely to match their needs and aspirations (FAO et al., 2014), youth will better understand how their community and territory functions (Robson et al., 2019a; Zetina et al., 2019), and youth can more easily position themselves as functioning actors within the community sphere (UNDESA, 2015).

It is our contention that youth engagement is important but if (desired) outcomes are to be maximized, communities (and the organizations that support them) must first build their knowledge of youth-community linkages and the factors that shape the prospects for youth wanting to engage in and with local governance institutions and structures. This means exploring what enables or hinders such involvement and to understand (and appreciate) the perspectives and aspirations that dictate the levels and types of participation that they (youth) will likely engage in (Park and White, 2018; Clendenning, 2019; Clendenning et al., 2019; Macqueen and Campbell, 2020). It means considering the drivers of social marginalization in rural areas; from employment to poverty, migration, education, technology, and land rights, and how these shape opportunities to participate. We know that formal (state-sanctioned) education can be poorly matched to Indigenous cultures, histories, and needs (Trucco and Ullmann, 2015), and young people may miss the local knowledge to enhance their livelihood skills and work opportunities (FAO et al., 2014; Zetina et al., 2019). Youth can be disadvantaged by structural impediments to land rights, tenure systems, and customary practices (White, 2019; Landesa, 2023), which makes their involvement in land-based livelihoods more difficult (Barney, 2012). When children do not inherit land, or do so at a later stage in life, this “[delays] their transition to independence and […] their attainment of greater decision-making authority” (IFAD, 2019: 33). The intersection between youth and gender is also pertinent here; if youth are underrepresented in community governance structures (Erbstein, 2013; MacNeil et al., 2017; White, 2019), then gender inequality can create additional complexities (Agarwal, 2010; Colfer et al., 2017; Elias et al., 2017). While women are taking on more active roles in community governance in rural contexts (Asher and Varley, 2018), the most powerful “voices” still tend to belong to older, adult men (ECLAC, 2018; Doss et al., 2019), and we do not know how perspectives on youth and gender interact to affect the engagement of young women specifically (Elias et al., 2018).

Researchers are beginning to explore such knowledge gaps. The Future of Forest Work and Communities (FOFW) project (see Robson et al., 2019a) was one example, connecting researchers with young people from forest communities across Asia, Africa, and the Americas to examine the fit between youth and forest-based work and livelihoods. In Mexico and Guatemala, youth spoke of wanting to participate more in community-making processes (Robson et al., 2019c; Zetina et al., 2019; Robson et al., 2020), with “strong connections between village youth, their community and their forest” (Zetina et al., 2019: 41). In Peru, young people who had emigrated from their community to a regional urban center maintained an interest in forest-related occupations (Quaedvlieg et al., 2019), while youth in Canada spoke of returning to their communities to practice their cultural tradition and engagements (Asselin and Drainville, 2020). Yet young people in these places remained frustrated at a lack of voice and involvement in territorial governance, and at the prejudices and misconceptions that older community members often hold about them (Robson et al., 2020; Mora Sánchez and Robson, 2022). The lessons from FOFW showed that relevant and meaningful youth participation probably begins with bottom-up processes where youth-held ideas and perspectives guide engagement processes and how interventions are planned, implemented, assessed, and modified (Vargas-Lundius and Suttie, 2014; FAO & CPF, 2018; IFAD, 2019). It is worth noting here that “meaningful” engagement is strongly tied to subsequent empowerment, since giving youth “the right, the means, the space, and the opportunity and where necessary the support to participate in and influence decisions and engage in actions and activities” helps them to feel invested “to contribute to building a better society” (Council of Europe, 2015:5). In the context of Indigenous territorial governance, this means not only involving young people in the “institutions and decisions that affect their lives” (Checkoway and Gutierrez, 2006:1), but making sure that decisions recognize and, indeed, reflect both their aspirations and evolving socio-political realities (Rajani, 2000; Trivelli and Morel, 2019).

The research we present here explores youth-held views and perspectives to enhance our (collective) understanding of the potential for youth engagement in Indigenous territorial governance. It was developed collaboratively by Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers and Indigenous community members (including youth) and, guided by three questions: i) How do young Indigenous women and men perceive of, and are currently involved (or engaged) in territorial governance? ii) To what extent do social norms and relations shape these perceptions and level of involvement? and, iii) What strategies might enhance youth involvement, and what are some good practices to drive change towards more socially sustainable outcomes? This collaboration took place over a 5-year period (2017–2022), with partners coming together at different junctures to plan, approve, carry out, and evolve the work. As researchers, we hoped to identify the factors that intersect to structure territorial governance opportunities for young people and consider how such governance might evolve through institutional and organizational adaptations. As community members, we wanted to understand from local youth how best to engage them and use these insights to guide decision-making that would better reflect stated commitments (see next section) to more inclusive governance in Lomerío. For all, the work has further enhanced capacities to work and collaborate with youth in these settings and on these kinds of issues. While we draw heavily on a single case–the Indigenous-controlled Territory (ICT) of Lomerío, in eastern Bolivia–we use our discussion to consider how empirical insights from other places can situate the lessons from Lomerio more broadly. This helps us to comment (and speculate) on how typical or atypical this case might be, and how our findings might apply to Indigenous territories and communities in other places.

While predominantly designed to showcase empirical, youth-focused research, the paper makes an additional contribution to this special issue on knowledge co-production. It does so by providing commentary and reflections on how research conducted with co-design and knowledge co-production in mind–where joint “processes of reflection, formulating questions, selecting methods, collecting and analyzing data, sharing, [and] learning” (Shackleton et al., 2023:2) and the accounting of diverse values, perceptions and worldviews are prioritized–can enable such elements to unfold in accordance with the needs and interests of collaborating partners, and that these may not be clear from the outset and can (and probably will) change over time. This speaks to the virtue of longer-term, multi-phased collaborative work that supports the building of relationships of trust, friendship and respect (Tobias et al., 2013; Toomey, 2016), and encourages researchers to be self-aware, and use critical reflection and self-evaluation to consider how knowledge is to be generated, shared, mobilized, and how (Castleden et al., 2012; Smith, 2012; Datta, 2018). We also contend that taking a bottom-up approach–where (academic) researchers engage partners and do work based primarily on the needs of those partners–can help collaborators to figure out how they want to work together, how research funds can best be spent (to maximize locally-derived benefits), and to enable collaborations to emerge organically rather than follow a set, pre-determined pattern. These and other lessons learned form an important part of the paper’s discussion and conclusion.

2 Materials and methods

The research adopted a qualitative, participatory, and collaborative approach (Merriam, 1998; Robson et al., 2019b) and case study strategy of inquiry (Yin, 2018) inspired by the principles and ideals of research co-design (Reed et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2023) and knowledge co-production (Simon et al., 2018; Norström et al., 2020). This involved collaboration between: Central Indígena de Comunidades de Lomerío (CICOL), the centralized body responsible for overseeing territorial governance in the Indigenous-controlled Territory (ICT) of Lomerío (hereafter referred to as Lomerío); the Instituto Boliviano de Investigación Forestal (IBIF), which has been working in eastern Bolivia since 2002 and with Lomerío since 2016; and the UNESCO Chair in Biocultural Diversity, Sustainability, Reconciliation and Renewal, based at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. The authors on this paper represent these three partners.

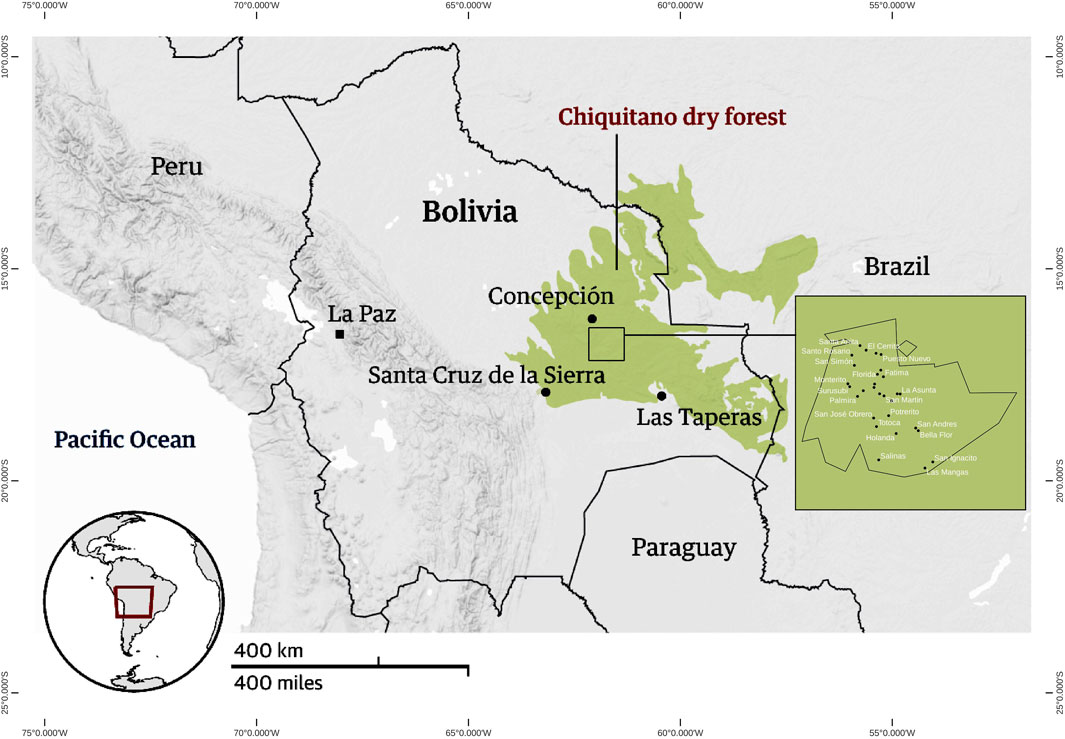

Lomerío (see Figure 1) is located in the Bolivian lowlands, a land-locked country in South America where Indigenous Peoples number over 4 million, or more than 40% of the country’s population (World Bank, 2015). Lomerío’s territory is home to extensive tracts of Chiquitano dry forest; the largest and best-preserved tropical dry forest in South America, rich in biodiversity and ecological functions (Pinard et al., 1999).

FIGURE 1. About here (Caption: Current extent of the Chiquitano dry forest region (in green), and (inset) the Indigenous-controlled Territory of Lomerío (Base map source: Collyns, 2019; Edited by: Reginald Jay Argamosa).

A history of colonization and post-colonial independence has seen extractive industries threaten Indigenous lands and livelihoods across the country (Robb et al., 2015), and only recently have Indigenous struggles for greater control over customary territories and resources gained traction. Reforms in the mid-1990s acknowledged Indigenous territorial rights and introduced “[the] decentralization of political power, and agrarian land reform” (Taylor et al., 2003), which potentially paved the way for Indigenous groups to be recognized as legal corporations or “owners” of their ancestral lands (Ortega, 2004). Progress was slow2, however, and subsequent calls for Indigenous territorial concepts to be better integrated into national plans and legal frameworks were made. This prompted the Bolivian government to replace the ‘Tierra Comunitaria de Origin’ (TCO) (or Native Community Lands) designation with that of ‘Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos’ (TIOC) (Native Indigenous and Peasant Territories); marking a subtle but significant shift from land to territorial rights (Tockman and Cameron, 2014).

Lomerío is heralded as a relative success story in the assertion of territorial sovereignty in Bolivia; a decades-long struggle that established legal title in 2009, providing the 29 member communities of the Monkoxi Nation of Lomerío with collective control over 259,188 ha of land, the incentives to devise a set of territorial rights and responsibilities, and a self-governance structure to articulate their relationship with the state (CEJIS, 2018; Baldiviezo et al., 2020). The Central Indígena de Comunidades de Lomerío (CICOL), first created in 1982 and ratified in 1996 as an Indigenous community organization, was given the responsibility to oversee Lomerío’s territorial governance, guided by a written statute (Estatuto Autonómico de la Nación Monkoxi del Territorio de Lomerío, 2017).

2.1 Lomerio’s governance structure

Governance in Lomerío is best described as collective in form and structure, with deliberations and decisions carried out via member assemblies, organized at different (community, zonal, territorial) levels.

The most important decisions, including those with implications for the use and management of the Indigenous territory-at-large, are taken in territorial-level (general) assemblies, with representation from all 29 member communities. ‘Ordinary’ assemblies occur once a year and are used to report to membership on key advances and plans moving forward. ‘Extraordinary’ assemblies are called as required to discuss and tackle pressing matters that require the attention of member communities. Decisions are made/carried by majority vote, with quorum reached when more than 50% of member communities are present (represented). Every 4 years, a general assembly is held to elect a new set of incumbents to run CICOL; the body responsible for enacting territory-wide governance in Lomerío. CICOL comprises 6 secretaries or ‘carteras’—each headed by a cacique3 (a community member elected by his or her peers who is responsible for associated activities for a fixed term)—that cover the following sectors: Acts and Communication (Second Cacique); Production, Economic Goods and Services; Gender and Youth; Land, Territory and Natural Resources; Health; Education; and Culture and Sport. The six caciques report to a Cacique General who acts as CICOL’s head authority and works to ensure the Assembly’s stated mandate. Below territorial-level (general) assemblies, each member community has its own local governance structure, consisting of community (communal) assemblies and ‘communal’ caciques, who follow a similar structure to that of CICOL; a ‘Head’ cacique, and five caciques who oversee community-level work tied to the areas of: Education; Economy and Production; Gender; Land, Territory and Natural Resources; and, Health. There are also zonal assemblies and zonal caciques that bring together groups of communities that represent Lomerío’s main territorial zones: Salinas (8 communities); San Antonio (8 communities); San Lorenzo (7 communities); and, El Puquio (6 communities). Each of these zones has a representative who attends the general assemblies (called by CICOL) to advocate for these groups’ particular needs. Coordination across governance institutions is largely reliant on the caciques that hold similar briefs–for example, the ‘Gender and Youth’ cacique in CICOL working closely with the Gender caciques at zonal and community levels, and vice versa.

The above arrangements are designed to provide Lomerío’s member communities with voice and vote across all three levels of governance (community-zonal-territorial), and the ability to collectively determine CICOL’s mandate for each of its 4-year terms. CICOL incumbents are elected by the 29 member communities, with each community presenting a candidate (male or female) for the general assembly to vote on. A first round sees the Cacique General and Segundo Cacique (Cacique of Acts and Communication) chosen, followed by a second round when sector-specific caciques are elected. In all cases, voting is through secret ballot, with results ratified by the Assembly before being made legal. The election of community-level authorities and caciques follows a similar process, with the only difference being that incumbents are elected every one or 2 years, depending on the internal norms/rules of the community in question. CICOL is responsible for supervising these community-level elections.

It should be noted that all caciques (at all levels) are elected; none are hereditary positions. Nevertheless, CICOL has in recent years been pushing to bring more young people into the fold. It has been vocal in expressing how Lomerío’s future will, in large part, be determined by the life and livelihood choices of upcoming generations. The territory’s population was 6,481 in 2012, with over a quarter of its residents aged between 15 and 29 (INE, 2012)4. These young people are growing up in a region where the local economy remains tied to subsistence farming and forest use, with limited capital investment and market integration. While providing livelihood opportunities is one priority for leadership, so too is a commitment to greater inclusivity in decision-making, with CICOL’s operating principles including a commitment to ‘consensus, broad participation, transparency in gender equality, equal opportunities and parity’, while the Territory’s recently published ‘Plan de Vida’ (Life Plan) of the Monkoxi Nation (2020–2024)’ (CICOL, 2019) states that women and youth should be able to “freely participate in decision-making tied to territorial use and management, with territorial welfare […]rooted in liberty and self-determination”. This is the context within which the work we present here emerged.

2.2 A phased research approach

Partnering with CICOL, the research engaged youth from 23 of Lomerío’s 29 member communities5, and explicitly involved local, young professionals to facilitate dialogue and engagement. Data collection began in 2017 and ended in 2022. In retrospect, the research interactions and collaborations over this multi-year period constituted four main phases or elements: i) first, a visioning workshop focused on the voice of youth; ii) second, a set of focus groups and follow-up workshop that brought youth and leadership voices together; iii), third, more in-depth research working with individual youth; and, iv) finally, a large-scale gathering of youth pushing for social change. This phased approach, which we describe in much more detail below, emerged organically, with each phase informed by and building upon what previous engagement work had shown and taught us. This enabled youth insights to be integrated into subsequent research design, and for us to innovate and prioritize (where needed) so that the research could contribute to ongoing youth empowerment processes. All phases were co-developed by researchers and CICOL and approved by the latter. All were created to give youth the opportunity to lead and guide discussions to a greater or lesser degree. Communication and collaboration protocols were discussed to help guide work among and between IBIF and University of Saskatchewan researchers, CICOL, and community leaders.

2.2.1 Phase 1

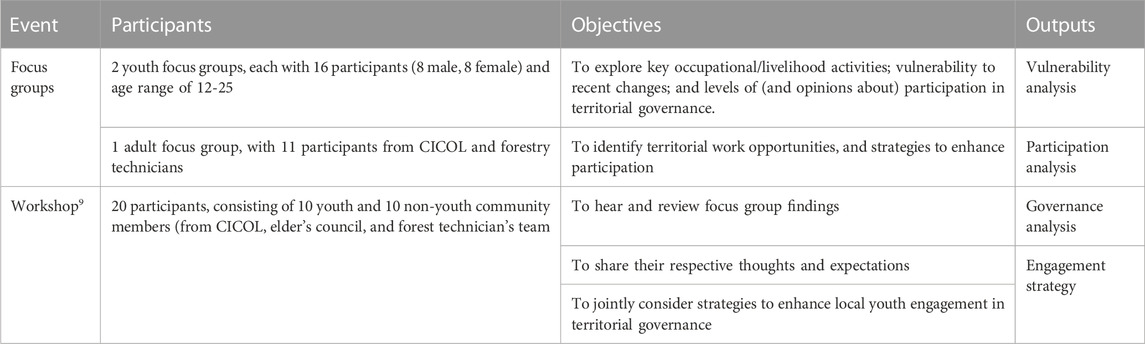

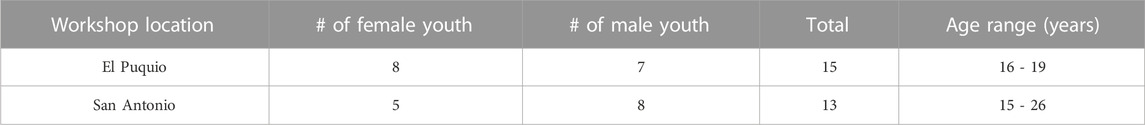

Instructive for9 building our understanding of youth-held aspirations and youth-forest-community linkages, and our capacity to work with youth, two ‘Visioning’ workshops took place in August 2017, engaging 28 Lomerío youth (see Table 1 for details) in conversations about their communities and their home territory, particularly local forests. This made use of a methodology (see Robson et al., 2019a) developed by an international team of researchers and practitioners, including several authors on this paper, which gave youth a lead in guiding those conversations and thus the knowledge production and sharing process that followed.

TABLE 1. Number, gender, and age ranges of youth who participated in the initial ‘visioning’ workshops to better understand the future of forest work and communities.

A follow-up meeting in June 2019 brought CICOL, IBIF, and researchers from the University of Saskatchewan together to present and share lessons and insights from the two workshops and discuss local concerns about elevated youth migration to regional urban centres (principally, Santa Cruz de la Sierra). CICOL expressed an interest in a second phase of collaborative research, and this was agreed to by all parties. CICOL were becoming aware of how little they knew about their youth and the perspectives and aspirations they held. This realization provided the platform for further engagement activities.

2.2.2 Phase 2

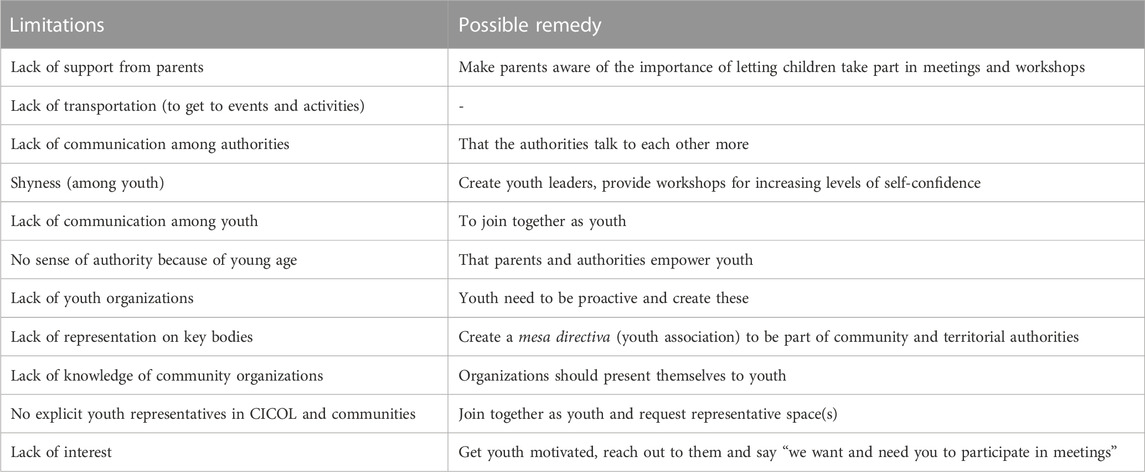

In November 2020, IBIF visited CICOL, representatives from the Consejo de Ancianos (Elders Council), and CICOL’s teams of forestry technicians to co-develop research based around a series of focus groups and workshops designed to generate insights from both youth and territorial authorities, and to bring the two groups together to share their thoughts and perspectives (Table 2).

The focus groups took place in December 2020 in the communities of El Puquio and San Lorenzo, and the workshop took place in February 2021 in the community of El Puquio. Information gleaned from these events was used by IBIF and USask researchers to conduct a vulnerability-participation-governance analysis, and the findings from this analysis are presented in the Results section below.

2.2.3 Phase 3

Master’s thesis research (Sarigumba, 2022) collected and analyzed data from semi-structured interviews with 18 youth (10 males and 8 females), representing 8 of Lomerío’s 29 communities. Youth ranged in age from 15 to 25; identified through a combination of convenience and representative sampling strategies. These interviews took place in late 2020 and were conducted remotely via WhatsApp and Zoom video calls, because in-person travel was not possible due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A mix of descriptive, narrative, structural, contrast, evaluative, and comparative questions were used to explore youth-held experiences, feelings, and perceptions with regard to participation and ‘place’ in community processes and territorial decision-making. These interviews helped to delve deeper into youth-held views, while creating a safer space for youth to voice their ideas and opinions than Phase 1 and Phase 2 (focus groups and workshops) had provided for.

2.2.4 Phase 4

This final phase involved an ‘Encuentro de Jovenes’ (or Youth Gathering, under the moniker of Together for our Territory) that took place in June 2022 with 101 youth participants (47 female and 54 male), most between 16 and 28 years of age. The aim was two-fold: to keep the conversation going between researchers, CICOL, and youth, and, in doing so, help to maintain youth engagement firmly on Lomerío’s agenda. The authorities (CICOL, Council of Elders, Community leaders) were reminded of efforts made to date, and, most importantly, of the commitment made to local youth; as valued constituents within the territorial sphere, whose voice and ideas would be given a platform to be heard. For the researchers, it was a chance to further verify data collected during Phases 1-3. At this gathering, youth, who contributed to setting the meeting objectives and agenda, spoke about the experiences they have had, both challenges and opportunities, to make meaningful contributions to their communities and in the home territory. This was a really important event in both placing youth at the forefront of knowledge co-creation and raising their profile at a territorial level. The event was led by the caciques from CICOL responsible for the areas of ‘gender and youth’, ‘health’ and ‘education’. IBIF staff helped to organize the agenda and to facilitate analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Youth links to the home territory

To youth, the idea of territorial governance is not confined to higher-level decision-making but extends to how the territory is accessed, used, and by whom. Youth recognized agriculture as the main land use and livelihood in the territory, with corn, rice, banana, and yucca the main crops planted for household subsistence. Aside from farming, the raising of livestock, hunting, and fishing were other common land-based practices that youth spoke to. A few mentioned timber harvesting from local forests for use in construction or to make furniture. Youth had some knowledge of the rules and policies regarding such activities. For subsistence farming, for example, “each family works on their own farm” (22/male/Palmira), and “everyone [above 18 years of age] has the right to use the land, without discrimination from anyone” (23/female/San Lorenzo). Upon being granted rights to use a designated plot of land, youth understood their responsibility not to use heavy machinery or chemicals and to help prevent fires.

Youth created ‘mapeos de actividades’ (activity maps) to show their activities within the territory and pointed to many being an important source of labour both at home and in the chaco (fields). As a young male from El Puquio explained, “[we] have that energy and action to help the [other] community members”. Some youth help out with ranching, an important source of income for families6 and often used to finance the costs of school and further study. Youth made mention of logging, though few directly participate. Female youth predominantly help their mothers in the home garden and with domestic chores. From an early age, most had taken part in a collective work institution known as ‘Minga’—for most, this involved cleaning and maintaining the church, school, plaza, and soccer field as communal spaces. Some of the youth engaged in activities requiring a degree of specialization: carpentry, construction, and wild honeybee production (in the case of the males), and arts and crafts and nursing (among the females). An ‘Other’ category included football, played regularly by many young women and men, attending church (important for young women), and attending fiestas (noted by some young men). For most youth, attending school was their main daily activity. Because a lot of the research took place during the COVID-19 Pandemic, when most classes were held virtually, youth said that they had been able to dedicate more time to domestic and territorial chores than was the norm. Finally, it is worth noting that the degree of overlap in activities was limited; young women and men coincided in just 5 of the 18 activities listed.

In the Phase 1 ‘visioning’ workshops and Phase 2 focus groups, youth had a lot to say about how improvements in technology and communication had aided connectivity, both within the territory and with the outside world. Improvements in transport and road infrastructure were seen as positives, enhancing movement and commerce between member communities, and facilitating territorial monitoring. At the same time, increased Internet access and cell phone connectivity were blamed for reductions in social interaction, with negative effects on family and community cohesion. Some youth were worried about the loss of tradition, pointing to apathy (among peers), the influence of modern music in the fiestas, and new religions as problematic developments. Youth wanted to connect more with older community members, and for traditional practices to be promoted at local schools and colleges.

3.2 Youth-held perspectives on territorial governance

Upon turning 18, Lomerío youth are expected to attend the general assembly and community-level meetings and have the right to ask for their own plots of land to farm or turn to pasture. Youth understood their involvement (in assemblies and meetings) to constitute part of responsibilities synonymous with active community membership. As a 22-year-old male from Palmira explained, upon reaching 18, you fulfill the functions of being a community member with [attendant] obligations and rights… [and a young person] can be elected as a representative of their community [cacique7].

When the concept of territorial governance was brought up in conversation, Lomerío youth were quick to focus on the role that the caciques play in managing and making decisions for how the communal territory is accessed, used, and managed. Most recognized the caciques as “the highest authority in the community or territory” (22/male/Palmira), with the responsibility to plan territorial activities, garner support from the broader community membership, engage and coordinate with external organizations, interact with families on land-based issues, and “carry the community forward”. Parallel to the work of the caciques, CICOL was mentioned by nearly all youth for its role in bringing the 29 member communities together to coordinate territorial use and management decisions. Most youth could (to some degree) articulate how this works. A 19-year-old female from Monterito captured it as follows: “We are organized and have a board […] which is at the head of the 29 communities that watch over the territory of Lomerío… we coexist with nature, the territory is our casa grande (big house), it is where we work, live, and exist and [we] have our own language, music, clothing, and culture”.

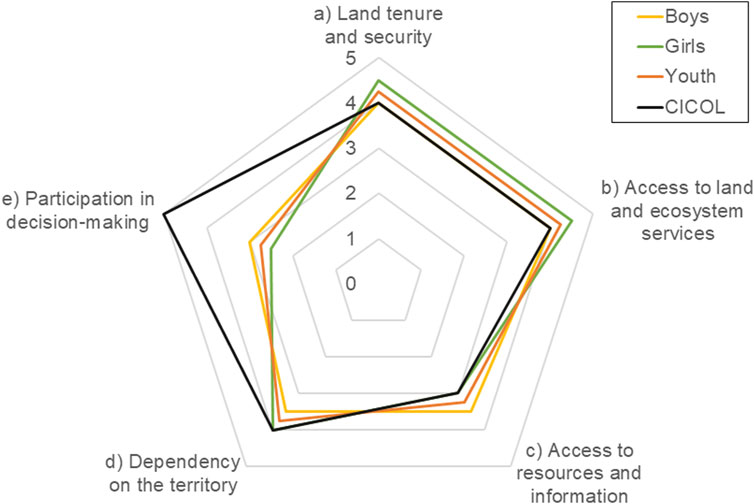

In the focus groups, youth participants shared their opinions on territorial rights, dependence on territorial resources, and level of participation in territorial decision-making (selecting 1 = Very poor, 2 = Poor, 3 = Satisfactory, 4 = Good, or 5 = Very Good to the questions being posed). The results, shown in Figure 2, make clear that most male and female youth see their tenure as secure8, providing them access to territorial resources and associated ecosystem services. In terms of territorial dependence, both groups of female youth, and one group of male youth, rated this as ‘medium-high’, with the second group of male youth setting level of dependence as ‘medium-low’.

FIGURE 2. About here (Caption: ‘How youth rank (their) tenure security, territorial dependence, and participation in territorial governance’).

With regards to (levels of) participation in territorial decision-making, the results were more mixed; two groups (one all-male, one all-female) ranked their participation as low, one group as satisfactory, and another as good. Male participation was overall higher than female participation. It was notable that no group ranked their participation as ‘very good’. We also asked CICOL to give their own set of rankings for youth-territory linkages. Their views were largely congruent with youth in terms of access to land, access to information, tenure security, and territorial dependency, but much higher than youth in terms of the level of youth participation in decision-making.

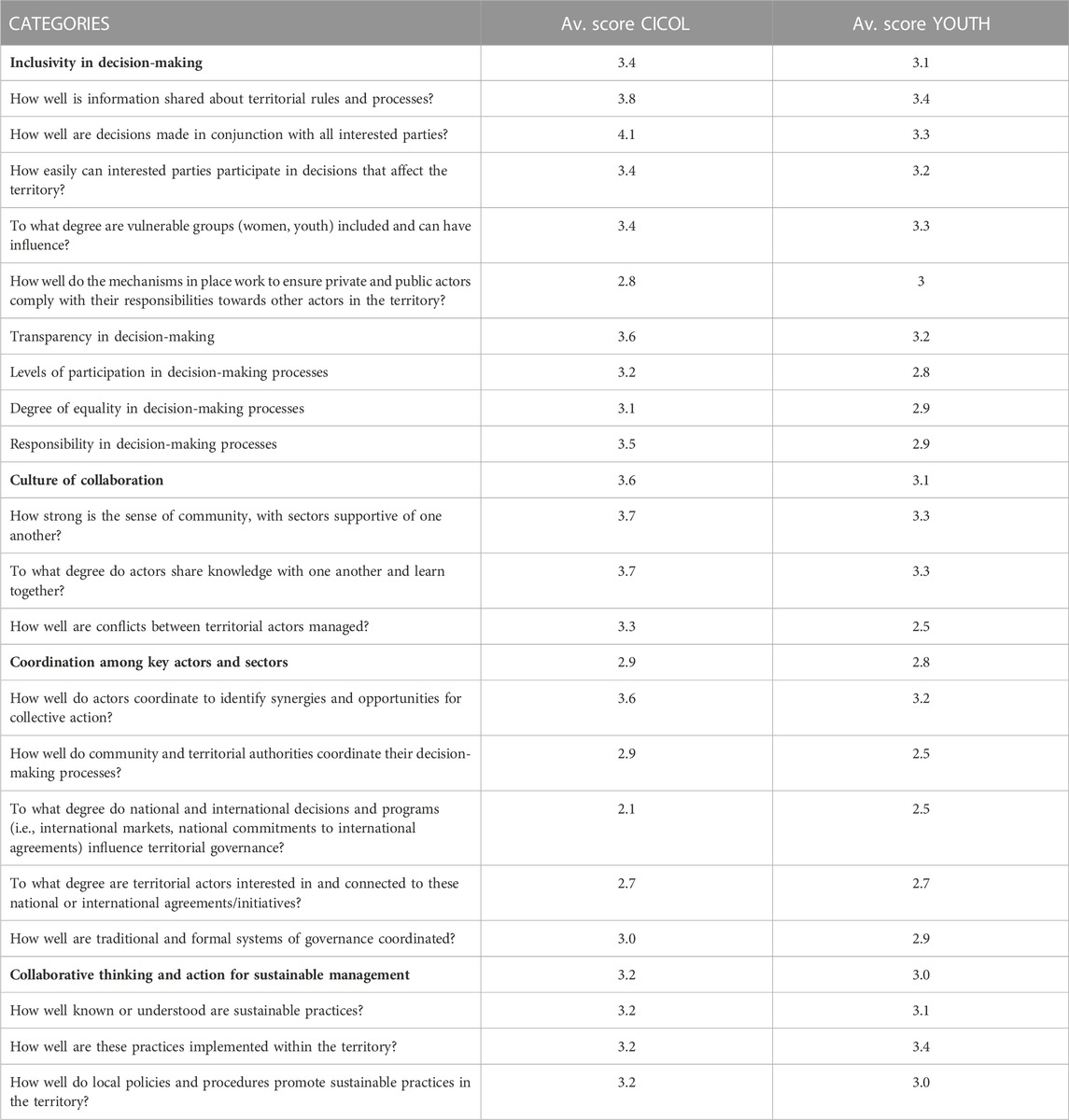

At the 2022 ‘Encuentro’, youth spoke about the reasons for sometimes limited participation, and possible remedies, with these summarised in Table 3.

These echoed the thoughts of youth interviewed during Phase 3. In particular, the challenge of getting to events and meetings (“we need the support of our parents so we can travel across the territory to take part”), and how the authorities could do a better job of getting the word out: “Many times information does not reach us [about things going on], or if it does it is very late in the day, […] CICOL does not coordinate well [across the communities] so we struggle to participate in different events”. Interview data also raised the issue of participation among the many youth not physically present in Lomerío: “[many] young people do not stay in the community… [there is] high migration […] to the city to search for better study and work opportunities” (22/male/Palmira), with that absence making it “impossible to come and be an integral part of the community” (17/female/Palmira).

We also wanted to know how youth felt when participating. Most felt welcomed by older community members, feeling that they wanted them there because youth were seen as among “the most dynamic” elements of community memberships and “able to contribute to [community] progress” (17/female/Surusubi). However, this also placed pressure on youth to not only attend but be active in these meetings. For some, this was a positive since it meant that their opinions might be heard and valued. Others were less effusive, notably two female interviewees who had unhappy memories of their first meetings, with one “a little nervous due to [their] lack of experience” and another feeling “a little strange [uncomfortable]” in that environment. Indeed, only three of our 18 interviewees said they were vocal and provided interventions–a suggestion, an idea, or a solution to a problem–when having attended a meeting. Most felt that if they did take the floor then everyone would listen but had not wanted to because they lacked the necessary “experience”.

3.3 Perceptions around quality of territorial governance

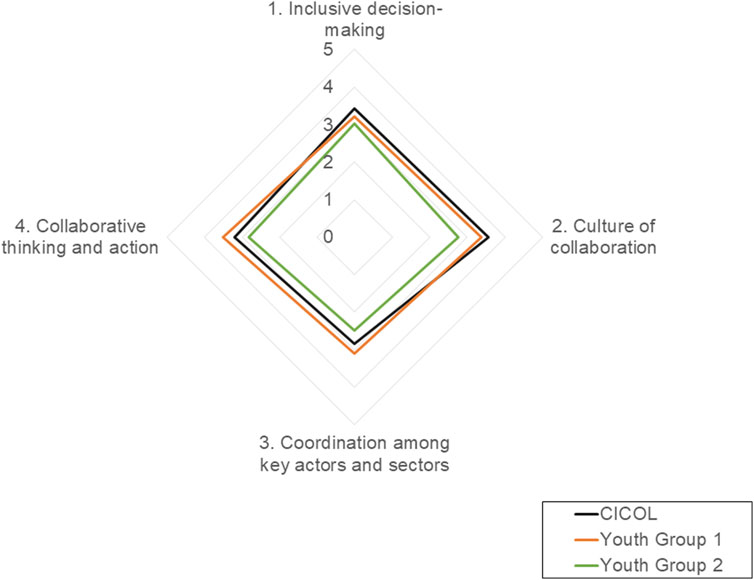

Youth and CICOL participants were asked to consider how well their territory was governed, measured against 4 criteria: Inclusivity in decision-making (to recognize and consider the rights, needs, and concerns of all groups of parties interested in the territory when decisions are made, and rules crafted); Culture of collaboration (the way in which people connect and work together in the territory); Coordination among key actors and sectors (whereby territorial actors and organizations ensure that norms and decisions do not enter into conflict and, where possible, are mutually reinforced and strengthened); and, Collaborative thinking and action for sustainable management (that territorial norms and decisions promote the sustainable use and management of territorial resources). Their average scores (based on; 1 = Very poor, 2 = Poor, 3 = Satisfactory, 4 = Good, or 5 = Very Good) are provided in detail in Table 4 and summarized visually in Figure 3 below.

FIGURE 3. About here (Caption: ‘Youth and CICOL-held perceptions of quality of territorial governance’).

Scores were in the ‘satisfactory’ range for most questions, with CICOL generally scoring higher than youth across three of the four categories. Both sets of participants scored highest (Satisfactory-Good) in the category of ‘making inclusive decisions’ and lowest (Poor-Satisfactory) in the category of ‘coordination among territorial actors and sectors’. No criterion was rated as ‘very good’ by either group, suggesting significant room for improvement.

3.4 Youth keen for greater say in decision-making

Throughout all phases of the research, youth gave the sense that they wanted to be more involved in territorial governance. Many spoke about a welcoming environment that could potentially support such participation, but that certain realities limited their current level of involvement. It was noted how youth who farm (independently) were in the strongest position to speak out and have their views considered, but they represented only a small minority of young people in the territory. And for the “big” land-related issues, youth in general did not “have the right to make decisions, […] older people or the elderly [do that]” (21/female/Coloradillo). The lack of a ‘youth representative’ in [territorial] decision-making spaces was identified as a problem. Youth also said that being encouraged to get involved, especially by their families, was important: “a big challenge for us is to get our parents to trust and believe in us, to petition CICOL to bring us together, to become leaders, to encourage and applaud those youth that are doing things, to bring us together and get us a seat at the table”.

But youth were also aware that they themselves could (and should) do more to demand or create the change they want to see. An important, early example of self-organization had been the Jóvenes Unidos por el Medio Ambiente (JUMA) (Youth United for the Environment) group, established as a response to the forest fires of 2019, and led by youth who wanted to be “more involved and ensure the revitalization of the environment” (18/male/El Puquio). Indeed, concerns about local environmental change were consistently raised by youth during Phase 1 and Phase 2 activities. Youth talked about agricultural production being down, impacted by pests and prolonged dry spells. They perceived declines in water bodies and fish diversity, prompting some to call for a ban on forest clearing along streams and rivers. Youth wanted to see funds to support forest restoration work; noting a decline in forest cover in recent years, driven by fires and logging that fell outside of the territory’s sustainable forest management plan. At times, one concern would contradict another, such as when worries about forest loss (in general) would butt up against youth-led calls for forest clearance to expand ranching (to potentially increase household earnings, which would not only help with living costs but also help fund continued education). Overall, though, youth in Lomerío vocalized interest in and concern for territorial issues and wanted a say in how the home territory is used and managed.

For CICOL’s part, there was an understanding that giving youth greater involvement would bring new and needed skills, knowledge, and training to the territory. With many young people continuing their studies (outside of the home territory), leadership were encouraging more among this group to get training in areas that could serve the future needs of their community. It was notable that they rarely discouraged young people to leave, especially those who want to “be professionals… [but also] a part of the community again by helping with the knowledge [they acquire]”. Youth themselves have picked up on this, with several highlighting (in their conversations with us) how young professionals are being hired and given important roles within CICOL and among its technical staff.

4 Discussion

Through enhanced youth engagement and participation, communities are believed to be better placed to achieve broad development goals, from social inclusion to organizational capacity and overall decision-making (Checkoway and Gutierrez, 2006; MacNeil et al., 2017). This extends to territorial governance, with today’s youth set to inherit key roles and responsibilities within their home territories (Zurba and Trimble, 2014), a reality recognized by both local leaderships and young people themselves, who are now demanding a seat at the table (Clendenning, 2019; IFAD, 2019; Robson et al., 2020). More broadly, this is happening within a context where states are becoming more open to recognizing Indigenous claims to customary lands (Monterroso et al., 2019)—whether driven by a commitment to honour Indigenous sovereignty or an emergent realization that Indigenous territories could help countries towards national biodiversity and climate-related targets (Wily, 2011; Woodley et al., 2012; RRI, 2015; Schuster et al., 2019)—and the role of youth in addressing social change and development more broadly (Bersaglio et al., 2015).

4.1 What did Lomerío teach us?

Our case from Bolivia offers several lessons for building Indigenous youth engagement and empowerment in the area of territorial governance, which we summarise here.

When young people participate in community activities with various levels of involvement, beginning in the fields (chacos) and extending to community meetings and assemblies, they become more cognizant of their land-based culture. When this does not happen, youth know less about their community and territory and may be less invested in those aspects of their cultural and personal identities (Zetina et al., 2019). The degree to which they have and are participating in wider community life can help to build a culture that values young people and lays the ground for them to voice their opinions and ideas. This scenario is not widely reported in the literature, which talks more about youth feeling underappreciated and underrepresented in decision-making spaces and institutions (Yunita et al., 2017; Quaedvlieg et al., 2019). Cultivating a strong sense of belonging increases the chance of success in youth engagement and empowerment, particularly in Indigenous territorial contexts predicated upon notions of comunalidad; of shared norms, shared cultural identity, and collective action (Kelles-Viitanen, 2008; Robson et al., 2018).

After 5 years of collaborative research, we have learnt that young people in Lomerío feel a part of their home territory, and this appears to hold true for girls as much as it does for boys. While bonds such as these can and do exist in other settings, the Lomerío experience stands out. For example, Indigenous youth in Mexico, Guatemala and other parts of eastern Bolivia have spoken to us of strong bonds that connect them to their community (Robson et al., 2020; Campos Rivera, 2022) but of customary institutions that are exclusionary because they have yet to “earn” the right to speak and make decisions through service and experience (Mora Sánchez, 2021). This can engender a feeling of alienation, of distance (rather than belonging), increasing tensions between the generations and becomes a push factor behind the decision to migrate (Aquino-Moreschi and Contreras-Pastrana, 2016). Lomerío would appear to buck this trend, with youth feeling welcomed in decision-making spaces and able to voice their opinion if they so choose. CICOL has always had youth participation clear in its statutes. However, little was done to promote their participation until after Lomerio’s successful struggle for territorial sovereignty and autonomy (and establishment of the Monkoxi Nation in 2009), which gave member communities impetus to (re)consider their relationship with one another and their customary territory and make efforts to bridge and consolidate youth-community relations (this research; Chuvirú Garcia et al., 2021; CICOL, 2022). In this way, the engagement work of the past 5 years should be viewed within the context of a larger socio-cultural-political project and serves as a reminder that Indigenous Peoples are at different moments in their struggle against (ongoing) settler colonialism (see Hernandez, 2022), and so their capacities to build social inclusion into these structures and norms are shaped by these particular histories and trajectories.

At the beginning of this paper, we said that we wanted to reflect on how typical or atypical a case, Lomerío may be. It is difficult to make such a determination, given the small sample size of published studies focused elsewhere. However, while we are not yet able to determine that Lomerío provides an experience atypical among Indigenous territories and communities, we are willing to speculate (based upon wider reading and our own experiences engaging youth in rural, remote communities across multiple global regions (see Robson et al., 2019d) that youth in Lomerío seem to be (or at least, feel) less impinged by the hierarchical, patriarchal nature of structures and norms that often limit participation and access to land in other places, and how certain demographics are viewed, valued, and represented. In Latin America, in particular, we have generally observed limited opportunities for youth in community-building processes (Robson et al., 2020; Campos Rivera, 2022; Mora Sánchez and Robson, 2022), consistent with insights from other global regions where rural youth are not actors within decision-making processes (see Cahill, 2007; Yunita, et al., 2017; IFAD, 2019).

4.1.1 Some question marks remain

Our findings from Lomerío also point to knowledge gaps or challenges that remain. Perhaps the most important of these concerns the difficulty to ensure that commitments to build social inclusion move beyond the symbolic, to be meaningful and real (Brennan and Barnett, 2009). Our interactions and conversations in Lomerío showed that the authorities have a genuine desire to involve and work with their young people. This is perhaps most evident in the youthfulness of current caciques, over a third of whom (based on our best estimations) are under 28 years of age. Yet ‘tokenism’ is always a risk, which Hart (1992), in this context, would see as youth being given a voice or platform, but not being given the chance (and supports) to formulate or communicate their opinions effectively. While Lomerío youth feel welcomed in meetings–an important barrier overcome–they often choose not to speak up in these spaces. This is not uncommon in rural communities in Latin America, indeed in many group settings, where “newcomers” can be reticent to speak without sufficient lived experience to give their words weight and meaning. While it is their choice to stay quiet, doing so limits their active participation, and this is most acute among younger youth. It speaks to a need to build their capacity and confidence to give voice to their ideas and opinions and may require some thought (by leaderships) as to how meetings and assemblies are conducted so that power is shared within engagement processes (Cahill, 2007) and content grounded in youth-held realities and concerns (IFAD, 2018).

Another important area where Lomerío was lacking is formalized youth representation in territorial governance spaces. CICOL sees the emergence of JUMA Monkox as important because it supports work in the area of territorial governance and environmental protection, while bringing Lomerían youth together. But it also recognizes that JUMA remains outside of formal institutional structures and norms, and can lack visibility and ‘presence’ across member communities. We concur that JUMA can (and should) take on a more active and integrative role, and support CICOL’s current efforts to integrate JUMA more fully into the Gender and Youth secretary (cartera) and the work of CICOL’s Territorial Technical Unit. We have seen that in other Indigenous contexts, from Guatemala (Zetina et al., 2019) to Bangladesh (ILC, 2020), ‘youth councils’ have emerged to give young people a collective voice in territorial matters and better representation within institutional structures. It is important that CICOL has recognized this and is striving to enhance JUMA’s profile in territorial governance; in the first instance, through territorial monitoring and oversight.

Digital technologies may also help build youths’ collective voice (Crowley and Moxon, 2017); in Lomerío, platforms such as WhatsApp group chats are now being used to connect youth who live in localities spread out across a large, remote territory, and build linkages between youth and community institutions. The other area that youth in Lomerío highlighted was ‘training’ – opportunities to develop their skills and knowledge, especially in the areas of forestry, digital technologies, ecological restoration, and marketing, among others. As Zetina et al. (2019) found for Indigenous youth in northern Guatemala, training can go hand in hand with the amplification of youth voice in community settings and help young people to more easily envision viable livelihood pathways within the home territory.

Finally, with regards to gender, it seemed notable that few youth highlighted differences in expectation ascribed to young men and women or reported any significant gendered disadvantages in decision-making processes. But neither can we be certain that the young women we engaged were willing to share their true perceptions with us, especially with regards to local cultural norms. Indeed, the somewhat contrasting nature of gender-based insights from Lomerío is suggestive that more, nuanced research is needed. For example, Oropeza (2022, unpublished report) had found patriarchal structures were still reinforcing a gender divide (i.e., women have to make double or triple the effort (than men) to achieve the same results) and making women disadvantaged players within the rural community sphere, as has been reported widely elsewhere (Silverman, 2015; Lastarria-Cornhiel et al., 2017; ECLAC, 2018). Yet the same author (Oropeza, 2022) also spoke about a generational change in gender roles, with more young men helping out with domestic chores, and young women in general spending less time taking care of the home and more time engaged in economic activities. In both cases, this was attributed to the democratic and participatory nature of Lomerío’s leadership, with internal rules and procedures now more supportive of gender equality. We would echo that, with the fact that there are caciques whose mandates revolve specifically around gender evidence of change, at least at an institutional level. But no matter that some attitudes and practices appear to be shifting, it would seem to be too soon to speak of transformative change; for example, under a fifth of elected caciques (currently) are women, and that figure does not change among the caciques in Lomerió who are under 28 years of age–four-fifths are male.

4.2 The prospects for youth to be significant territorial actors

This research was focused on the role of young people in territorial governance, and how Indigenous communities might engage youth to be more than just a source of physical labour in land-based and community activities (i.e., farming or forestry); to become leaders and agents in the territorial sphere. In Lomerío, connections between youth and the home territory are forged through hands-on involvement in land-related activities. The significance of work in family and community chacos cannot be overlooked, since it is through such activities and practices that young people build ties to the land and appreciate the importance of holding land tenure from which they can draw benefits. It is significant that young people in Lomerío, irrespective of gender, can access and use land upon turning 18. The broader literature suggests that this is not common among Indigenous youth across global regions, where many are denied such rights (FAO et al., 2014; Kosec et al., 2018; Yeboah et al., 2018), limiting their power and authority within the home community and territory (IFAD, 2019). Also significant is the fact that young people in Lomerio have access to productive lands, again in contrast to scenarios elsewhere where youth are more likely given degraded plots of limited value (FAO et al., 2014; Yeboah et al., 2018). Access to good land appears to be one important entry point for youth engagement and integration, as it helps youth to exercise their rights and capabilities (UNDESA, 2015), be better positioned to carve out a land-based livelihood and shows them how customary norms shape their engagement and empowerment as community actors.

While ‘engagement’ largely concerns reaching out to youth and opening up spaces for their participation, ‘empowerment’ is about creating the environment (mechanisms) by which youth build an enhanced sense of control and esteem through participating and feel encouraged to lead initiatives for the benefit of their peers and communities (Pritzker and Metzger, 2011). In other words, it “sets the stage for clearly identified youth roles and long-term participation in the community development process” (Brennan and Barnett, 2009: 305). A sense of empowerment also comes from knowing that youth are really being listened to, and for youth this means being able to talk about the aspirations that orient their future (White, 2019), influence life choices and self-perception (Schaefer and Meece, 2009) and, ultimately, life outcomes (Leavy and Smith, 2010). Youth aspire to a better future, but what that means or looks like for a young person growing up in a remote and rural region cannot be understood (by others) unless these same youth feel comfortable to share their thoughts and ideas in a non-judgmental setting. Our sense is that the authorities in Lomerío are doing well in the area of engagement but are yet to translate this into youth feeling sufficiently empowered to contribute to the long-term, transformative change that they want to see (see Salter, 2022). Youth are made to feel welcome in general assemblies and community meetings, and some have even been elected to fill leadership positions because of the skills they possess. Yet, while many youth might be considered ‘territorial actors’ from a use or livelihood perspective, few make decisions about how lands are used or managed. The formation of JUMA Monkox, the recent series of youth engagement workshops and other initiatives (see Chuvirú Garcia et al., 2021), and the emerging trend of young professionals taking on key positions (as caciques or technical staff), are important recent advances. Similarly, the current 4-year (2022–2026) plan to develop local education curricula that better connect young people to Monkoxi identity and territory (CICOL, 2022) may prove extremely important. Nevertheless, most young people in Lomerío are not active in governance but regarded a source of labour “[of] energy, ideas, and skills” for rural production–a scenario that mirrors findings from the Future of Forest Work (FOFW) initiative, where most youth from participating communities fell into the same category (Robson et al., 2019a).

It would seem that many Indigenous territories have work to do in this area. Unfortunately, they do not seem to be receiving the right support from external rural development agencies and organizations, many of which espouse youth engagement but design associated interventions towards market-oriented livelihood and skills development to boost local rural economies. Only a handful of the 66 youth engagement projects/initiatives reported upon in FAO et al. (2014), IFAD (2018) and Robson et al. (2019a) looked to engage youth in a dialogue about community-related pathways or to co-create solutions together. And none spoke explicitly about youth as key actors in territorial governance. These kinds of initiatives certainly have the potential to enhance local livelihood opportunities, and thus help to retain youth in their home communities, but they fall short of what youth themselves are asking for (this research; Clendenning, 2019; IFAD, 2018; IFAD, 2019; Mora Sánchez and Robson, 2022); namely, a sense of empowerment and to feel a degree of “ownership” over community-generated projects, initiatives, and policies.

Of course, the life pathways that youth choose for themselves are equally relevant in any discussion of youth-community linkages, and how choices (of youth) take place within a broader development context where mobility and ideas about what constitutes the “good life” may or may not sit well with the daily realities of territorial life. In Phase 1 engagement workshops and Phase 3 interviews, youth spoke of the challenges of rural life, repeating things heard in other places (IFAD, 2019; Robson et al., 2020; Mora Sánchez, 2021)—from limited educational and work opportunities to the fit between collectivist ideologies and personal (life, work, family) aspirations. In other words, do places like Lomerío offer what young people believe they need? In Lomerío, young men and women enjoy equal access to productive land upon turning 18, and yet many still leave the home community or territory for work or study. This serves as a powerful reminder that secure tenure alone is rarely enough (Hecht et al., 2015); work, education, and life goals must still stack up against the realities of community life.

This speaks to a broader tension evident in many remote and rural communities, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Even if youth are proud of their roots and their Indigeneity, and feel connected to their communities, some will expect–often encouraged by their parents–to leave for a “better” life elsewhere. It is a reality that presents community leaderships with a conundrum; tasked to bring young people into the fold, they are part of a society that also pushes them to (potentially) build a future elsewhere. This serves a reminder that power and influence resides with families and households and is not only exercised within community-level institutions, and that tensions, which we have observed everywhere we work, needs to be navigated if the integration of youth is to be achieved and sustained, and requires bridging the gap between youth-held aspirations and the social and political realities and structures that these communities are founded upon (Rajani, 2000; Checkoway and Gutierrez, 2006; Brennan and Barnett, 2009). It seems inevitable that some of those structures will need to be adapted, even reimagined, to better reflect emergent realities–work that has begun (see Robson et al. (2019c) for an analysis of Indigenous community adaptation to change driven by pervasive out-migration) but requires more investigation and tracking to fully understand.

4.3 What we learnt about research co-design and knowledge co-production

We wrote this, first and foremost, as an empirical paper, with neither research co-design nor knowledge co-production the central arc or theme. However, both approaches have been fundamental to how our work emerged and was conducted, and how empirical findings were generated, shared, and validated (and built upon throughout the process). It also provides an example of how co-production not only happens in the context of community-researcher collaborations, but also internally, among (and across) community actors. In this final section, we reflect on what we have learnt from working together in this way, and how that might shape our research in the future.

First, co-design can emerge organically and without prior intent on the part of the researcher (or the community). This was a 5-year, phased research design. But that is what it became, not how it started out. We had begun as a collaboration between University of Saskatchewan and IBIF researchers; part of an international team of academics and practitioners working on the Future of Forest Work and Communities project. We approached CICOL with the idea of doing a couple of visioning workshops with local youth and they agreed because it coincided with concerns that they had (at the time) about youth involvement in territorial life and decision-making, and rates of youth out-migration. In the discussions that followed all parties were interested to work together to keep youth engagement on the agenda. That led to Phase 2, which in contrast to Phase 1, brought youth and community authorities together to co-produce knowledge and to learn from one another. That objective was jointly formulated but driven by CICOL. Phase 3 (interviews with youth) emerged because it became apparent that group settings were not always conducive for all youth to share their ideas and perspectives. Phase 4 built on what we had learnt through Phases 1-3, to create a bigger platform for local youth (over 100 participated) to convey a message to their authorities–that they cared about the home territory and wanted to be involved but needed to be listened to.

This phased approach was a powerful reminder that co-design manifests in different ways and sits on a spectrum; guided by the needs and resources of the community partner, not all elements of research necessarily incorporate, indeed require, co-design, while others do. Phases 1 and 3 were more researcher-driven, with design reviewed and approved by CICOL. Phases 2 and 4 were much more driven from below, with CICOL taking a lead in methodological design and how those activities were organized and run. This is the mix that proved appropriate for our emergent collaboration. And by allowing elements of co-design to feed into the process, more of us (as collaborators) felt invested in the work. From a researcher perspective, we were better positioned to honour and respect several key principles, from ‘conducting research in a good way’ to ‘generating benefits for community partners’ (see Reed et al., 2023), that we wanted to adhere to. From a Lomerío perspective, we were in a position to ensure that the work was always tied to our priorities and conducted in accordance with local norms and ways of doing things. As an Indigenous Territory, we are uncertain as to where our ongoing process of youth engagement will go, but by working with IBIF and the University of Saskatchewan over the past number of years, we have been able to develop a variety of platforms and spaces by which our youth can share their voice and perspectives. And this has generated insights that will assist CICOL as it works to get a meaningful role for youth ever more established on the territory’s agenda.

The other benefit, perhaps not anticipated (or certainly not by design), is that these encounters have reinforced a notion among youth that their territorial authorities do see them as an important and valued constituency. While none of this should be overplayed (or underplayed for that matter), it is a reminder that perhaps the true value of creating these spaces is not for research purposes (i.e., for the empirical knowledge it generates), but for how it facilitates or prompts community members to talk about things that are important to them and that do need thinking about. It is why CICOL have been open to collaborate with IBIF and the University of Saskatchewan over multiple years, and why youth have been generally enthusiastic about participating in these research activities. Such an insight strengthens the idea that co-production processes are about more than creating knowledge; they are processes to “develop capacity, build networks, foster social capital, and implement actions” (Norström et al., 2020). At the same time, those of us from outside of Lomerío have become acutely aware of the care needed when discussing, what are, internal and sovereign territorial matters; the importance of getting to understand and then work within the boundaries or limits of where and how to get involved. Fortunately, CICOL knows this only too well, and have been forthright with us (as Bolivian and international researchers) about our remit and role, and that decisions about how information is used internally or what strategies to pursue are for them to deliberate and decide upon. So, while this collaborative process has been useful for the territory, what comes of this work is not something the rest of us can (or should) be a part of. Rather, the Monkoxi Nation, together, will determine, guided by their Statute, their cosmovision, and their ‘saberes locales’ (traditional knowledge) (see Chuvirú Garcia et al., 2021; CICOL, 2022), what the future will bring.

5 Conclusion

This research, built on 5 years of collaborative research with the Indigenous-controlled Territory (ICT) of Lomerío in Bolivia, has explored the prospects for Indigenous youth to be engaged and empowered in local territorial governance. The work provides insights for other regional contexts, building knowledge of youth-community linkages and dynamics and strengthening our methodologies for engaging and working with youth in participatory, applied research. As such, it creates a foundation to scale-up this line of inquiry to investigate the intersection of youth and community and territorial governance across Latin America and global regions more broadly. Our findings highlight the importance of having community norms and practices in place that value young people, that help create a welcoming space for them to function within the community sphere, and it is this that provides the foundation from which meaningful engagement initiatives can emerge. The Lomerío case shows that this process is not straightforward or easy, and nor should one expect it to be. Beyond creating a welcoming environment for youth to share their thoughts, ideas, and perspectives, the process by which the right spaces and opportunities are realized, to enable young people to find their own role and place in community-level and territorial-level decision-making, is inevitably a slow, incremental one. But a key lesson here is the importance of authorities, and by extension broader community memberships, (genuinely) recognising that all constituencies within the community sphere have a role to play. That it is this–and not how many concrete changes are achieved within a certain timeframe–that opens the door for the underrepresented to become visible and active; to understand their social and political realities and structures and begin to mobilize to bring about the change they want to see. In this way, the Lomerío case is instructive because it shows how a contemporary Indigenous territory might go about enabling and building a culture where young people are made to feel valued and given the platform to contribute, which is a process that will inevitably take time and navigate the realities of territorial sovereignty, young people’s tenure security, and communities’ diverse development trajectories. It also shows that when leadership gets the issue of youth engagement taken seriously by broader community memberships, this will not go unnoticed by young people themselves. It can be the catalyst for self-organization, where youth see that they could start pushing for the changes that they want to see. It is here that applied research, if based on the principles of collaboration, co-production, and co-design, can play a role in helping to construct a platform for dialogue, especially in places where time and financial resources are limited.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article may be made available by the authors upon request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

MSa, MSo, JR, IQ, and OC contributed to conception and design of different phases of the study. MSo led facilitation of Phase 1 of the research, using a methodology developed by an international teams that included JR, MSo, and MSa. MSo and IQ led Phase 2, MSa led Phase 3 (with support from IQ), and OC led Phase 4 of the research. MSa carried out the critical literature review that underpins the paper’s Introduction and Discussion sections, supported by MSo and JR. MSa and JR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Revisions were overseen by JR, MSo, and MSa. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada (Connection Grant # 611-2016-0262; Insight Development Grant #430-2018-00007, both JR PI), a University of Saskatchewan International Research Partnership Fund (JR PI, 2020-2022), the UNESCO Chair in Biocultural Diversity, Sustainability, Reconciliation and Renewal, and the Dutch Government and Tropenbos International through the Green Livelihoods Alliance (https://greenlivelihoodsalliance.org/).

Acknowledgments

Our heartfelt thanks to all of the community members, youth, and authorities from the Monkoxi Nation of Lomerío who participated in this research. Without their time and willingness to share knowledge, opinions, and ideas, this work would not have been possible. For their specific help in organizing and facilitating youth-engagement events and workshops, and for knowledge sharing, we thank Flora (Yifan) He, Reina Garcia, Elmar Masay (former Cacique General), Anacleto Peña (current CICOL’s Cacique General) and Aylyn Vaca (current CICOL’s Gender and Youth Cacique). We thank Dr. Maureen Reed for her insights on community-engaged scholarship and youth-gender intersectionality, and support for MPS in her master’s thesis work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1There is no universal definition for “youth” or “young people”; with definitions varying across international organizations and national governments according to variable sociocultural, institutional, economic, and political factors (ADB & Plan International, 2018). For operational purposes, the United Nations (UN) defines youth as those between 15 and 24 years of age (UNDESA, 2013). Yet in practice, age is not the sole indication of who is or is not a “youth”; some societies, for example, regard youth as the transition phase as individuals take on greater responsibilities for family, for finances, or in their community (ADB & Plan International, 2018) and the age at which this occurs varies.

2Indigenous communities in Bolivia have continued to suffer from incomplete formal land titling, a lack of clarity around rights, inter-communal conflicts and disputes, pressures from extractive industries and agricultural companies, and socio-economic marginalization (RRI, 2015; Monterroso et al., 2019).

3It should be noted that the contemporary meaning of ‘cacique’ in the Lomerian context–a fixed-term elected governance post or position of responsibility–deviates from the age-old association with the term, which refers to a local political boss, often hereditary (rather than elected) and nearly always male, who typically exercises a high level of power and authority over their subjects.

4The last national census in Bolivia was conducted in 2012. The next one is scheduled for 2024.

5We were unable to secure representation from all 29 communities because of difficulties in visiting and/or bringing youth from some of the more remote localities in the Territory.

6Ranching was introduced to the territory by Jesuit missions in the late 1600s and early-to mid-1700s.

7Caciques are individuals elected to play specific administrative roles in their communities, where they look after key sectors (i.e., Health, Education, Gender), or within CICOL´s governance structure.

8Members of one (female) group did express concern about illegal incursions by a neighbouring Indigenous territory (to harvest valuable tree species), and this had affected their perception of tenure security.

9‘Mapeo de actividades’ were presented by each focus group, followed by a question period with CICOL and the Elders Council. Next, information about current levels of youth participation in territorial use and governance was reviewed. Participants were then invited to define a vision for the future, including concrete steps and actions to improve future participation.

References

Agarwal, B. (2010). Gender and green governance: the political economy of women's presence within and beyond community forestry. Oxford: OUP.

ADB [Asian Development Bank] & Plan International (2018). What’s the evidence? Youth engagement and the Sustainable Development Goals. London: Plan International UK: Manila: ADB Headquarters.

Aquino-Moreschi, A., and Contreras-Pastrana, I. (2016). Community, young people, and generation: contesting subjectivities in the Sierra Norte de Oaxaca. Lat. Am. J. Soc. Sci. Child. Youth 14, 463–475. doi:10.11600/1692715x.14131240315

Asher, K., and Varley, G. (2018). Gender in the jungle: a critical assessment of women and gender in current (2014–2016) forestry research. Int. For. Rev. 20 (2), 149–159. doi:10.1505/146554818823767537

Asselin, H., and Drainville, R. (2020). Are Indigenous youth in a tug-of-war between community and city? Reflections from a visioning workshop in the Lac Simon Anishnaabeg community (Quebec, Canada), 17. World Development Perspectives.

Assies, W. (2006). Land tenure legislation in a pluri-cultural and multi-ethnic Society: the case of Bolivia. J. Peasant Stud. 33 (4), 569–611. doi:10.1080/03066150601119975