- 1Department of Biotechnology and Food Science, Agricultural University of Tirana, Tirana, Albania

- 2Department of Economy and Rural Development Policies, Agricultural University of Tirana, Tirana, Albania

- 3Albanian Development Fund, Tirana, Albania

- 4International Union for Conservation of Nature, WCPA, Ljubljana, Slovenia

- 5Department of Economy and Business, Beder University, Tirana, Albania

This study aims to identify and evaluate ecosystem services and calculate the total economic value of Vjosa Valley, an endangered riverine ecosystem. An instrumental-deliberative approach is used with experts and Albania’s general public. The results show that experts highly evaluate Vjosa Valley for its cultural ecosystem services, while the general public assigns higher importance to regulation ecosystem services. Two monetary measures have been calculated, WTP and WTA. The results indicate no significant differences between WTP and WTA when using a payment card. Participants will pay, on average, 7% of their monthly incomes to protect Vjosa Valley from Hydropower Construction. This study was developed during the pandemic of COVID-19, and the results may be affected by the context; however, it represents the first economic evaluation of this rare ecosystem in Albania and Europe.

1 Introduction

The debate among policymakers, environmental bodies, and academia about assigning a price tag to natural resources continues. Enormous efforts have been undertaken to make them tangible by quantifying the goods and services offered by nature to humankind through the concept of ecosystem services (ES). ES is defined as the direct and indirect contributions of fundamental importance to human wellbeing, health, livelihood, and survival (Costanza et al., 2014). The conceptual framework of ES, as defined by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) in 2005, has become a model that links the functioning of ecosystems to human welfare. It persists as a dominant environmental paradigm that opens up crucial global conservation opportunities (de Groot et al., 2002; Fisher et al., 2009). In addition, a common conceptual framework is used to compare the different range of stakeholder perceptions of the role and value of ES to understand better the trade-offs involved—across sectors and stakeholders in a multiscale—from local communities, national, and international. This multiscale analysis at the local and national level is also used in the case of the Vjosa River Ecosystem. Vjosa/Aoos River is in a transboundary area of Albania and Greece, one of Europe’s last living wild rivers. Throughout its entire course of over 270 km, the Vjosa/Aoos River is a natural and free-flowing water body characterised by canyons, braided river sections, and vegetation-covered islands (Shumka et al., 2018a). The Vjosa River offers various and diversified ES that can be grouped into four groups according to the MEA 2005 ES classification. More than 15 priority habitat types of European interest have been identified (CE, 2013). At least 177 species listed in the Appendices of the Bern Convention, 13 out of 16 Albanian amphibian species and 32 out of 37 reptile species reported in Albania are present in either aquatic or terrestrial habitats of the Vjosa River (Shumka et al., 2018b). The Vjosa Valley hosts around 70 of the 83 registered mammal species in Albania (approx. 84%), for example, the European otter, a globally endangered mammal, and 257 waterbird species to approximately 80% of the species known in Albania (Ibid.). However, this European resource of important natural heritage was under threat of the construction of hydro powers endangering the entire ecosystem. IUCN has commissioned the preparation of a study for the protection of the Vjosa River Valley based on the IUCN Protected Area Standards (IUCN, 2021). Thanks to the efforts of national authorities, NGOs, academia, and international donors, the Vjosa River and its three tributaries have recently been protected as a national park. Therefore, the economic evaluation of the ecosystem’s goods and services is an important step that will provide a shred of clear and tangible evidence of the value of this unique ecosystem for Albania and Europe.

Pruckner et al. (2022) emphasise that due to climate change, the ecosystem’s viability is going to deteriorate, and Beca-Carretero et al. (2020) add to the issue the fact that transformation of the ecosystems may transfer the remaining community and, in later phases it may have a massive impact to the associated ecosystem functions. Despite the various ES studies, none of them offer integrative overview of the total economic value and how is the people’s willinges towards their conservation policies. While Xu et al. (2018) reports the obsance of a complete pitcture on how people value the ES and the economic value they may give to understand the public interface. For this reason, Christie et al. (2012) suggest using evaluation methods that measure the willingness to pay considering the environmental issues. Zhogmin et al. (2003) state the willingness to pay for ES restoration using CVM, but even they suggest using the willingness to accept as more accurate measure. We have integrated all ES based on the suggestion by Zhongmin et al. (2003), which assess some river ecosystem and conclude that an assessment of integrative ES may result in a more accurate result. ES are directly linked to communities, and their sustainable conservation relies heavily on the community’s attitude, motivations and perceptions. According to Owen et al. (2020), the feedback of local actors is “critical for diverse stakeholders in a given space to “feel” collectively attached to a shared problem and future” to ensure a transition towards greater sustainability.

Similarly, Saha and Taron (2023) present the imperative need to understand the community’s attitude in formulating the policies for ES protection. For instances, local and non-local stakeholders may put different value to the ES (Harrison et al., 2018; Zoderer et al., 2019). Based on this, results derived from an integrative approach with the participant from the Vjosa Catchment and Tirana may serve as a basis to reveal their willingness to conserve ES in the future. The other novelty of the deliberate approach used in this paper is inclusion to the TEV measures 53 experts which is derived from Hernández-Blanco et al. (2021) and contributes to the modified benefit transfer for the value of ES. Due to above mentioned gaps and discrepancies, the aim of this study is to identify the total economic value for ecosystemic services in Vjosa Voley through a deliberative and integrated approach.

The paper is organised into four sections. The first examines the concept of SE and provides the total economic value (TEV) methods used in different ES evaluation literature. The second presents the methodological framework. A discussion of the field research results is presented in the third part, while conclusions are provided in the final section.

2 Literature review

Numerous studies demonstrate ES as a potentially powerful concept to guide sustainable and equitable natural resource management strategies (Costanza et al., 1997; 2014; Costanza, 2000; Abson et al., 2014). As previously mentioned, the MEA (2005) structures the ES in four main pillars: provisioning (PES), regulating (RES), cultural (CES), and supporting services (de Groot et al., 2002; Groote, 2009). Several studies have been dedicated to ES classification and TEV (Cropper and Oates, 1992; Costanza et al., 1997; de Groot et al., 2002; Bastian et al., 2012; Costanza et al., 2014). However, still debated are the perspectives and concepts related to ES and the methodological tools that lead to monetary value (Fisher et al., 2009; Banzhaf and Boyd, 2012). Current research on ES is essentially focused in two directions, the first deals with biophysical assessments and the second with economic/monetary valuation (Plieninger et al., 2013; Plieninger et al., 2015). A third, but largely overlooked, component of ES is the socio-cultural domain (Daniel et al., 2012). In this regard, one of the critical challenges for ES research is to develop a comprehensive methodological approach in which biophysical, socio-cultural, and monetary values can be explicitly considered and integrated into decision-making processes (Hornung et al., 2019). Several scholars have considered CES the most salient and compelling reasons for people to conserve or restore natural systems despite their persistent underrepresentation (Schaich et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2012; Daniel et al., 2012; Kirchhoff, 2012; Milcu et al., 2013; Plieninger et al., 2013; Willis, 2015). The ES valuation task is vital in developing countries because environmental goods and services are essential to family production functions. The lack of income diversification in developing countries also claims the urgency of CES and other passive economic values in TEV procedures.

Although value refers to several distinct concepts, values are central to fully understanding ES. Values can generally be considered evaluative beliefs about the worth, importance, or usefulness of something or moral principles (Hirons et al., 2016). A full review of ES values and methods to capture these values is beyond the scope of this paper. However, it is important to understand the diversity in which people value the environment because different elements of value are captured by different valuation methods, especially in riverine ecosystems.

The economic value attached to freshwater ES is estimated using a surrogate for the observable behaviour witnessed in the marketplace (Wilson and Carpenter, 1999). Within the inventory of methods used to measure the economic value of freshwater ecosystem services, the travel cost method (TCM), hedonic prices (HP), and contingent valuation method (CVM) have been used so far. Fleming and Cook (2008) used the zonal travel cost method (TCM) to evaluate the recreational value of River McKenzie.

CVM is a widely used method for all-purpose evaluation when dealing with ES services. Several scholars have used it to estimate economic values for all ecosystems and environmental services; see Wilson and Carpenter (1999) for a review on freshwater ES. CVM assigns monetary values to non-use values of the environment—values that do not involve market purchases and may not involve direct participation (Hanemann et al., 1991; Portney Paul, 1994; Boxall et al., 1996). These values are sometimes referred to as “passive use” values. They include everything from the essential life support functions associated with ecosystem health or biodiversity to the enjoyment of a landscape or a wilderness experience, to appreciating the option to fish or bird watch in the future, or the right to bequeath those options to your grandchildren (Acharya, 2000; Ressurreição et al., 2011; Pearce et al., 2013). It also includes the value placed on simply knowing that the ecosystem exists. CVM deals not only with direct and indirect use-value, but also existence value and transgenerational value.

Citizens in nations as diverse as Norway, Turkey, Brazil, and Bulgaria indicated similar levels of Willingness to pay higher taxes for environmental protection, showing high levels of public concern for the environment (Inglehart, 1995). The more significant environmental concern among residents of developing nations is attributed to life subsistence matters (Dunlap and York, 2008). This issue puts forward the problem of ES evaluation and implies that the institutional and cultural context largely affect this process. Thus, in contexts where monetary valuation methods are not considered appropriate or possible to develop, several non-monetary valuation methods can be used, such as scaling and ranking (Hirons et al., 2016). Thus, methods that prioritise stakeholder understanding and the co-production of knowledge also represent an alternative to the accurate evaluation of ES. Indeed, studies from different stakeholder perceptions, perspectives, values, attitudes, and beliefs may generate more meaningful insights regarding the contributions of ES to human wellbeing than purely biophysical assessments (Martín-López et al., 2012; 2014; Iniesta-Arandia et al., 2014). The present study proposes a combination of the instrumental approach, which aims to measure the TEV of the Vjosa Catchment ecosystem, and the deliberative approach based on local stakeholder perceptions. The following section introduces the operationalisation of these approaches.

3 Methodology

The deliberative approach explored the desired ends and states of the functions and values of ES in the Vjosa Catchment. In addition, an instrumental approach involving the ranking of preferences based on the ES framework typology proposed by the MEA 2005 was applied.

The research design of this study is based on Sekaran (2003) and it has undertaken an exploratory research with the main aim to have a complete overview about people’s wilingness to pay and willingness to accept on Vjosa ESs. In oder to further explore there were interviewed 53 experted to serve as focus group and also the interviewing process with individual from the Vjosa Voley and Tirana. The case considered is Vjosa Voley in Albania. A small number of participants identified as local stakeholders and experts, about 53, were recruited through the snowballing procedure and participated in a Vjosa Catchment-ES rating. They represent local businesses, community participants, local and central government associations, NGOs, and academia. Combining these approaches aims to avoid the biases generated by one single approach. In the case of the deliberative approach, we may not have a required degree of expert involvement, while for the instrumental method, the format of the question assures a higher response rate. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus groups have been partly developed online.

The value assigned to ES through CVM can be presented in two theoretically commensurate empirical measures (Wilson and Carpenter, 1999). Through the amount of money people are willing to pay (WTP) for a site not to be damaged or to prevent loss of a species (Fleming and Cook, 2008) and through the minimum amount an individual would need to be compensated for accepting a specific degradation in a good or service, “willingness to accept compensation” (WTA) (Kolstad and Guzman, 1999). The first scenario comprises a WTA mechanism using a payment card technique. The exact wording of the scenario was presented to respondents as follows: Suppose that the companies that will build the hydropower plants will pay you for the damage they cause to the Vjosa Valley ecosystem in the form of a monthly payment per household. In your opinion, how much would the monthly payment be per family that would justify the damage to this ecosystem? 200 ALL1/Monthly, 400 ALL/Monthly, 1,000 ALL/Monthly, 0 ALL/Monthly. To avoid anchoring bias from the presented payment card, we have also included an open question. If you are unwilling to accept one of the payments listed on the card, how much would that be?

As a result of the reported controversy over CVM, we have also used the WTP scenario as follows: Suppose that you are required to pay a monthly family tax2 to provide the necessary budget that will impede the building of hydropower plants and thus preserve the Vjosa ecosystem intact. How much would you be willing to pay? 200 ALL/Monthly, 400 ALL/Monthly, 1,000 ALL/Monthly, 0 ALL/Monthly. The same open question is directed in the WTP scenario. The TEV will be calculated by generalising the values at the country level.

The WTA and WTP are calculated based on the following formula:

Where:

S → WTA or WTP at Country level

S→ sum of WTA or WTP of the sample

ni→ sample size (per Region).

Ni→ population size (total population over 16 years old of the surveyed region).

N→ Total population of the surveyed area.

M- > Total Population of Albania over 16 years old.

3.1 Sample design

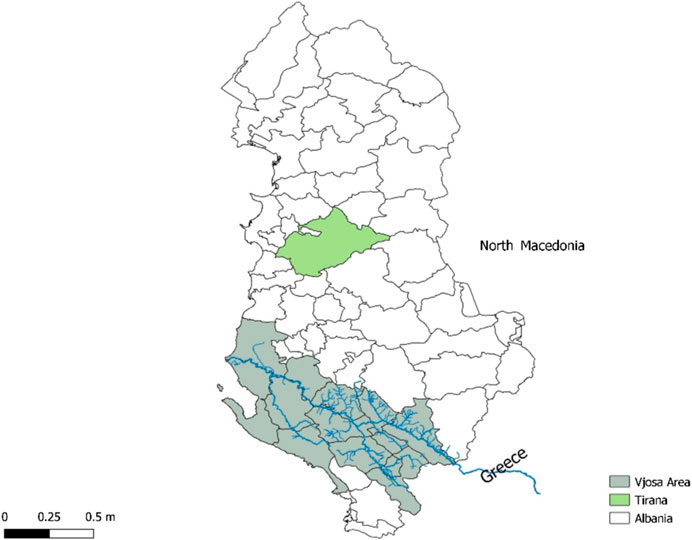

Since it is impossible to acquire a complete census of the targeted area, which has about 395,000 residents, a sampling technique is used. Considering that a minimum representative sample size is required, we suggested a sample size with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. This approach offers the minimum sample size without compromising the reliability of the results. The final sample comprises 400 residents in the Vjosa Catchment areas and 400 other residents in the Tirana Municipality. The sample selection for the municipality is calculated separately from the Vjosa Valley areas, and it occupies more than 70% of the total population of selected areas. The respondent sample is composed of the residents of the following areas: Municipality of Permet, Gjirokastra, Tepelena, Memaliaj, Kelcyra, Selenica, Mallakastra, Vlora, Sub-Municipalities of Kuta, Centre Tepelene, Brataj, Sevaster, Qesarat, Kote, and Tirana (see the map of the Vjosa Valley area). The main reason why Tirana, the capital of Albania, is included in this study is to gain a representative estimation of TEV of Vjosa Valley at a country level. This study’s population comprises residents aged 15–64 years and the study area is shown on Figure 1.

To select residents in each area, we used the simple random sampling technique (when the list of contacts exists), while face-to-face interviews were applied to the areas that lack the predefined list of respondent contacts. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we have combined face-to-face interviews, mail interviews, and phone surveys for this study. Face-to-face interviews were mostly used with residents living in rural areas because the list of phone numbers was unavailable. It was almost impossible to conduct online interviews due to poor internet access and limited information and communication technology (ICT) knowledge. Applying the questionnaires to several outlets assured a high response rate, about 90% (729 out of 800 questionnaires). The following section presents the results and their respective discussion.

4 Discussion of results

Vjosa River is a central ecosystem for the whole region. Its services are very important; for the majority of experts and stakeholders (68%), it is the only ecosystem offering such services. Local stakeholders consider Vjosa to be a focal point of economic, cultural, aesthetic, and environmental sustainability and the development vector of the area. Although Vjosa has traditionally been an important development vector for the area, the economic activities that provide this development are not related exclusively to the direct use-value of the river ecosystem (e.g., fish, gravel, water for hydropower). The indirect use-value of the latter, like the sumptuous landscapes, green and natural areas, traditional varieties and elaborated gastronomic skills, are developed due to the river’s existence.

The Vjosa ecosystem use and non-use values are not limited only to the area’s local population. The totality of local actors and experts state that this ecosystem impacts the Albanian population, and some (43%) consider it to have an international reach. This is not due only to the international status of Vjosa (which borders Albania and Greece), but also the multiple ties that link this ecosystem with others in Albania or beyond through aquatic and non-aquatic fauna species; it is a nesting area for some types of birds and a habitat for some species of fish).

The main risk identified by the experts and local actors is related to the change from a lotic to a lentic environment that will produce significant changes in the functions of the ecosystem by reducing or interrupting them. Experts consider these changes to have a domino effect in all Vjosa ecosystems. While few (6%) think the river can adapt to these changes, even this minority requires necessary and particular intervention to restore the river’s ecosystem.

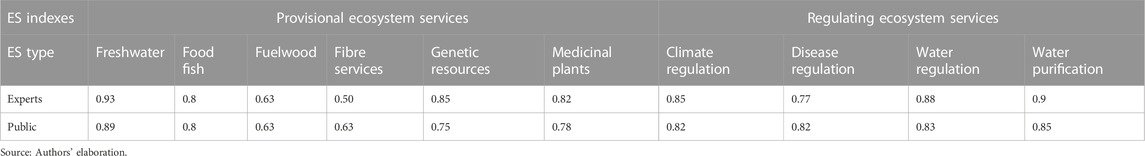

The calculation of ES indexes based on 53 experts and local actors from the municipalities of VV, in addition to ES experts from Tirana, displays the high preferences of the latter concerning the ES of Vjosa Valley. The Vjosa ecosystem offers a high level of ES to the human community, ranked at 0.82 out of 1 (see Table 1). Experts consider that the diversity of services, considering the three elements (i.e., PES, RES, CES), in this ecosystem runs from high to outstanding. Local actors think that Vjosa provides the community’s cultural services. Although the difference between cultural and regulation services is unimportant, it still reflects the importance of Vjosa as a symbolic and historic attraction.

The expert evaluation reveals that freshwater is PES’s most important ecosystem service, with firewood and timber the least evaluated (see Table 2). This is because the use of firewood and timber is strictly regulated in Albania, and partly forbidden due to a moratorium on its use. The difference in the importance index between firewood (0.63) and timber (0.5) is mainly related to the fact that the use of wood for fuel purposes is still allowed. The evaluation of experts tends to under-evaluate the use-value of ecosystem services (they prefer the conservation strategy over that of usage). However, it is interesting that even the broader public is inclined toward a conservation strategy since it has evaluated the same ES (see table 2).

Three other ecosystem services of the provisioning group, namely, food, genetic resources, and medicinals and aromatic plants, show a very high and quite comparable index. The area is an important source of medicinal plants and other genetic resources that traditionally provide a consistent income for rural families. The expert group identified the importance of freshwater as an ES of Vjosa as a key element, especially in agriculture and for recreational purposes.

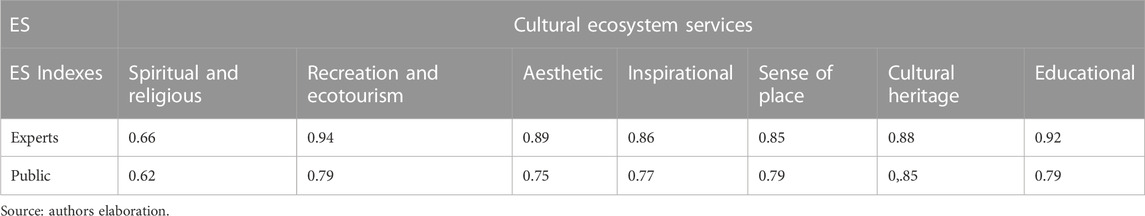

The second group of ES, Regulating Services, show a higher index than provision services (0.85 out of 1). This index is mainly related to water regulation and purification. Although the river run positively impacts the population of the Vjosa Valley, the experts do not identify any benefit to the population. The respective index is the lowest for this ecosystem services group. The index for the climate regulation service is higher, mainly related to the positive effects of the Vjosa River and its affluence on the area’s climate. It is still important to underline that the Vjosa River plays an important role in the hydric system of the whole area and thus regulates the totality of hydric resources of the area. This main characteristic of Vjosa is already widely accepted by experts and policymakers in the Karavasta lagoon, where the role of the Vjosa River is considered substantial. The last group of ecosystem services is related to cultural services, which are highly rated by expert opinion. The Vjosa Valley gathers a wealthy cultural heritage due to the relationships and interactions between several cultures and populations with different backgrounds. These relationships and interactions are also made possible because of the Vjosa Valley. It is important to note that the experts rate highly nearly all of the ES, except religious ones, with a lower evaluation rate (0.66 out of 1). This result is unexpected because the Vjosa Valley has assemblies for at least three of the four main religions in Albania. A possible explanation may be religion’s limited relevance in Albanian society. All other ecosystem services related to the cultural services score much higher; all score an individual rate of more than 0.85 out of 1. Among those ecosystem services, recreation and ecotourism score the highest index, 0.94 out of 1 (see Table 3). These complementary services show an extremely high value for the VV in terms of cultural services and the future development of the tertiary sector in the area. The VV is introduced as a unique selling proposition, especially in the municipality of Përmet.

The calculation of the ES indexes based on 729 questionnaires put to the selected sample shows that the PES index is 0.75 out of 1, regulating ecosystem services index (RES) is assigned 0.83 out of 1, and the CES index is 0.77 out of 1 (see Table 1). The VV ecosystem offers a high level of ES to the human community; the total VV-ES index is 0.78 out of 1 (the expert-based VES is 0.82 out of 1), with slight differences from the local expert-based ES evaluation. Statistically significant differences in the indexes of ES in Tirana, Permet, Gjirokaster, Vlora, and Selenica are shown; the respondents have assigned a higher RES score than the other ES. Climate and disease regulation services show the same index score of 0.82 out of 1. This result is interesting and requires further study to understand the trade-offs between the two services. The water regulation index ranked 0.83 out of 1, and water purification scored 0.85 out of 1, which also explains the importance of freshwater service in the highly ranked PES category. In Fier, Memaliaj, Brataj, and Ane Vjosa, participants attributed higher importance to the PES, with the food index achieving 0.8 out of 1 and the freshwater index achieving 0.89 out of 1. These results show that according to community perceptions of those near and far from Vjosa Valley, this ecosystem can offer a myriad of ES; the outstanding index scores support this finding.

The findings show also that the respondents have demonstrated high preferences for RES. While the typology of PES is less preferred, the latter has also been less evaluated by experts and local actors. Interestingly, the respondents assigned high scores to the RES, which is not the case in the expert and stakeholder-based evaluation, especially for disease regulation services. This result is not expected since it is assumed that the experts have more knowledge on the effect of freshwater ecosystems regulating features. In the same vein, local stakeholders and experts should have more experience and knowledge regarding the regulating dimension offered by the Vjosa Valley-ES. This outcome may be linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, whereby health issues have become a priority to the respondents, and that is why they place RES in the first place (disease regulation having the higher score) when dealing with ES. An interesting finding is also linked to CES. The experts have evaluated this ecosystem feature more highly than the broader public; the expert index is 0.86 out of 1, while the public evaluation score was 0.77 out of 1. The ES, based on expert and local actors’ evaluation, embeds the strategic role of VV-ES in the development of the areas near VV from a long-term perspective. The general public does not usually perceive this value.

The low indexes for Fibre and Firewood services show again the pertinence of using the ES framework to understand perceptions. As presented previously, RES shows the highest index among the ES. All of the RES scored higher than 0.8 out of 1. The greater importance of RES is observed not only in the population living in the area but also by the respondents living in Tirana. Communities in Albania are becoming increasingly aware of environmental issues and the impact of ES quality on the overall wealth of the population.

The idea of the intangible or non-material benefits of nature has found popular expression in the notion of CES as put forward in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2003). Benefits derived from recreation, spiritual enrichment, inspiration, and cognitive development contribute to meaning and purpose in the individual’s life (Willis, 2015). The respondents demonstrate a higher preference for the cultural heritage of the Vjosa Valley ES (0.85 out of 1), While recreation and ecotourism, a sense of place, and educational factors represent the same index (0.79 out of 1). Spiritual and religious ES display the lowest index among the CES. The local expert evaluation also assigned it the lowest score (0.66 out of 1). Three possible explanations can be made: firstly, the low importance of this ES may be linked to the limited relevance of religion in Albanian society; secondly, it lacks information regarding existing events that are organised around the religious characteristics of the area. Moreover, from the methodological viewpoint, cultural heritage is sometimes confounded with spiritual and religious aspects. In conclusion, the respondents in this study acknowledge the importance of VV-ES, an essential aspect that justifies the TEV approach application.

4.1 Analysis of the TEV of Vjosa Valley ecosystem services

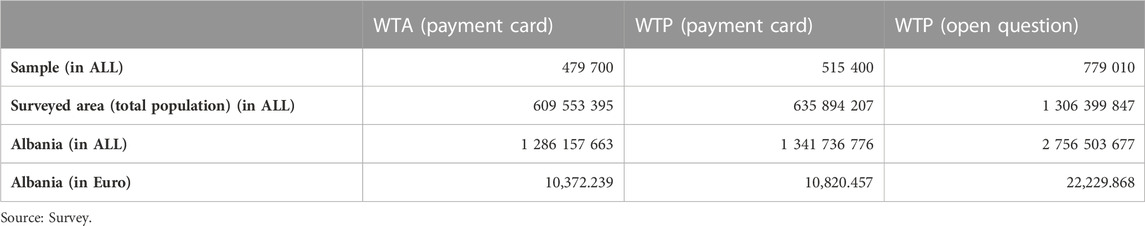

In a favourable non-market situation with imperfect substitutes, the divergence of WTP and WTA value measures is persistent, even with repeated market participation and complete information about the nature of the good (Morrison, 1997). Plott and Zeiler (2005) show that there is no consensus regarding the nature or robustness of the WTP-WTA gap and, similarly, none about the fundamental properties of misconceptions or how to avoid them. In the present research, the WTA and WTP value on VV-ES is almost the same when comparing data from the payment card technique. When the open question is introduced in both payment mechanisms (WTP and WTA), the WTP doubles the WTA. The WTA value is approximately €10.4 million/year, and that of WTP is €22.2 million/year. This difference arises because about 21% of the respondents have reported an empty value for WTA, explaining that no price can be placed on damage caused to the ecosystem. The calculation of WTP and WTA is made on three levels: first for the surveyed sample, then for the whole population of Vjosa Valley and Tirana, and finally for the entire Albanian population (see Table 4).

The respondent demographics such as age, gender, education attained, household income, sector of employment, and the origin of the respondent are collected to identify if there is any effect on the TEV. Stratified forms of sampling are important concerning the social valuation of ES, particularly when some groups are likely to be affected by an ecosystem management decision more than the wider regional population (Raymond et al., 2014). In absolute terms, the total WTP of respondents living in Vjosa Valley is about 2.9 times lower than those living in Tirana. The difference is related to an external factor, such as the economic disparity between both populations. The average monthly expenditure per family is much higher for Tirana compared with the other regions in Vjosa Valley. The expenditure level is a trustful proxy for the family’s income level, and if the income level is reduced considerably in recent years, this will directly impact the WTP of the local population. It is interesting to note that average monthly expenditures at the national level (Albania) are more or less the same as the average of the three regions (Tirana, Vlora, and Gjirokastra), especially in 2015 and 2018. This means that from the income perspective, the evaluation of WTP is representative of the Albanian population.

Several pieces of research have shown the inclination toward environmental issues and their linkage with economic development (Dunlap and York, 2008; Notaro and Paletto, 2011). High-income countries assign high importance to the environment compared to low-income countries because the latter has other emergent problems to cope with, such as unemployment and economic crises, among other issues. Albania lacks research in that direction. Nevertheless, in a recent unpublished work concerning the WTP regarding a very well-known national park named Lura, Albanian citizens reported a willingness to pay yearly about €30 for the rehabilitation and protection of the park. The WTP was recorded before and after the earthquake emergency in Albania in November 2019. As expected, following the earthquake, WTP decreased on average to €26 and has continued to decrease during the COVID-19 pandemic to €25. The results from this study can also be used to understand the value attributed by Albanian citizens to the Vjosa Valley ecosystem from a broader perspective. The current analysis is developed during a pandemic, during which people usually assign lower importance to environmental problems because health issues have priority. Even though was not the scope of the present research, blue spaces (aquatic ecosystems such as lakes and rivers) affect long-term physical and mental health (Pretty et al., 2005; Barton and Pretty, 2010; White et al., 2014; 2017; 2020; Dzhambov et al., 2018; Garrett et al., 2019; Chiabai et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021). This is shown also in the importance conferred to RES by respondents by implicitly giving the highest index to disease prevention service ES. The effect of Vjosa Valley on health is an object of future studies.

It is interesting to analyse the difference between the three methods i) WTA payment card, ii) WTP payment card, and iii) WTP open question. Other research shows a difference between the WTP and WTA; the WTP is generally low compared with the WTA (Brown and Gregory, 1999). The authors mentioned above list several studies where the ratio WTA/WTP ranges from 2:1 to 5:1. The CVM estimates may accentuate this ratio due to CVM’s tendency to overestimate (Brown and Gregory, 1999) asymmetrically. Similarly (Sayman and Öncüler, 2005), suggest that the lack of markets for environmental goods increases the difference between the WTA-WTP. Other studies show that the difference between WTA and WTP is smaller for ordinary private goods than for public and non-market goods (Tunçel and Hammitt, 2014). In the present research, the difference between the WTA and WTP is less than 5% which leads us to the conclusion that the perception of the consumers about the way both payments and acceptance is going to be the same by tax increases and tax reduction and not a direct payment or direct income. In that regard, the differences between the two values tend to be less evident. The concept of WTA among the Albanians tends to be biased due to the feeling of the consumers to consider the WTA as a payment to trade-off something very important for them. The low WTA value can be considered as well as a protest vote to protect the natural area. The elicitation format of the CVM also shows differences in the WTP estimation.

We consider that the most appropriate value of WTA is the open question WTP which considerably reduces the effects of payment card construction to achieve a more inclusive value of WTP.

5 Conclusion

This research will improve the understanding of stakeholder knowledge about, and perceptions of VV-ES and will contribute to fulfilling an essential part of the knowledge gap in Albania. In this country, information on local community awareness and perceptions of ES is greatly needed. The study makes a clear departure from the methodological limitations of previous research. The differences in the importance conferred to the VV-ES in different areas in Albania show that the MEA 2005 framework of ES is applicable in the Albanian case.

Ecosystem services in Vjosa Valley are considered to be very important in the opinion of experts, the population of the area, and respondents living outside the Vjosa Valley (0.82 out of 1 for experts and local actors and 0.75 out of 1 for the broader public). Their services are highly appreciated in all the components, namely, 1) Provisioning services, 2) Regulation services, and 3) Cultural services. For all components, it is interesting to note that despite their differences, the experts (and local actors) and the broader public show a very high appreciation for the Vjosa Valley ES.

Albanians are keen to pay more than €22 million per year to protect the Vjosa ecosystem. The figures elaborated by the study reflect the reticence of respondents to protect the environment during a health crisis period. According to similar studies focusing on other environmental resources, the WTP value may decrease by up to 30%. If the study’s timing had been different, it is expected that a WTP of more than €28 million/year would have been indicated.

The selection of the sample that spans not only the Vjosa Valley area but also other regions of the country, especially Tirana, since it represents a mixture of the country’s population, was chosen to arrive at an evaluation that reflects the whole country. Each respondent is keen to pay, on average, 707 ALL/month or nearly 7% of total household income. This average value is not impacted by the socio-economic characteristics of respondents, which is typical for this method, showing that the payment for Vjosa ES is persistent in all population categories independent of age, education, gender, or income.

This study may help design the Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) scheme, which is currently a need because Vjosa River has been establised as National Park, which will provide ES to both local and international communities. Moreover, the results may support other policies, strategies and initiatives in Albania and broadly strengthen the narrative for the conservation and restoration of other riverine natural resources. Additionally, they may be incorporated into any mid-term and long-term project regarding climate change actions and other related sustainability issues.

We suggest including spatial territorial characteristics in the analysis for the sustainable development of the ES itself based on the Li et al. (2022) approach. This is especially important for the case of the Vjosa river, considering that it may enrich the understanding of its transnational area (Greek and Albanian). Moreover may balance the relationship between ES conservation and socioeconomic development. Another good contribution may be the development of a meta-regression analysis like Liu et al. (2022). Including macroeconomic data in ES economic valuation, especially in developing countries, may serve for proper local policy design because they face economic difficulties and other social and cultural matters.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, EK, FG, ES, AS, and KG; methodology, EK, FG, and KG, software, ES and AS; validation, EK, FG, ES, AS, and KG; formal analysis, EK, FG, ES, AS, and KG; investigation, EK, FG, ES, AS, and KG; resources, EK, FG, ES, AS, and KG; data curation, EK, FG, ES, AS, and KG; writing—original draft preparation, EK, FG, ES, AS, and KG; writing—review and editing, EK, FG, ES, AS, and KG; visualization, EK, FG, ES, AS, and KG; supervision, EK; project administration, FG All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1Albanian Lek.

2It was explained in the questionnaire that respondents would not pay any tax and that this is a hypothetical situation that will be implicitly used to assign a value to the VVES. This explanation was offered to avoid the effect of mistrust in institutions and the tax payment.

References

Abson, D. J., von Wehrden, H., Baumgärtner, S., Fischer, J., Hanspach, J., Härdtle, W., et al. (2014). Ecosystem services as a boundary object for sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 103, 29–37. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.04.012

Acharya, G. (2000). Approaches to valuing the hidden hydrological services of wetland ecosystems. Ecol. Econ. 35 (1), 63–74. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00168-3

Banzhaf, H. S., and Boyd, J. (2012). The architecture and measurement of an ecosystem services index. Sustainability 4 (4), 430–461. doi:10.3390/su4040430

Barton, J., and Pretty, J. (2010). What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health? A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 (10), 3947–3955. doi:10.1021/es903183r

Bastian, O., Haase, D., and Grunewald, K. (2012). Ecosystem properties, potentials and services – the EPPS conceptual framework and an urban application example. Ecol. Indic. 21, 7–16. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.03.014

Beca-Carretero, P., Teichberg, M., Winters, G., Procaccini, G., and Reuter, H. (2020). Projected rapid habitat expansion of tropical seagrass species in the mediterranean sea as climate change progresses. Front. plant Sci. 11, 555376. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.555376

Bolund, P., and Hunhammar, S. (1999). Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecol. Econ. 29 (2), 293–301. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00013-0

Boxall, P. C., Adamowicz, W. L., Swait, J., Williams, M., and Louviere, J. (1996). A comparison of stated preference methods for environmental valuation. Ecol. Econ. 18, 243–253. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(96)00039-0

Brown, T. C., and Gregory, R. (1999). Why the WTA–WTP disparity matters. Ecol. Econ. 28 (3), 323–335. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(98)00050-0

Chan, K. M. A., Satterfield, T., and Goldstein, J. (2012). Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecol. Econ. 74, 8–18. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.11.011

Chen, K., Zhang, T., Liu, F., Zhang, Y., and Song, Y. (2021). How does urban green space impact residents' mental health: A literature review of mediators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (22), 11746. doi:10.3390/ijerph182211746

Chiabai, A., Quiroga, S., Martinez-Juarez, P., Suarez, C., Garcia de Jalon, S., and Taylor, T. (2020). Exposure to green areas: Modelling health benefits in a context of study heterogeneity. Ecol. Econ. 167, 106401. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106401

Christie, M., Fazey, I., Cooper, R., Hyde, T., and Kenter, J. O. (2012). An evaluation of monetary and non-monetary techniques for assessing the importance of biodiversity and ecosystem services to people in countries with developing economies. Ecol. Econ. 83, 67–78. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.012

Costanza, R., d'Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., et al. (1997). The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387 (6630), 253–260. doi:10.1038/387253a0

Costanza, R., de Groot, R., Sutton, P., van der Ploeg, S., Anderson, S. J., Kubiszewski, I., et al. (2014). Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Change 26, 152–158. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.002

Costanza, R. (2000). Social goals and the valuation of ecosystem services. Ecosystems 3 (1), 4–10. doi:10.1007/s100210000002

Cropper, M. L., and Oates, W. E. (1992). Environmental economics: A survey. J. Econ. Literature 30 (2), 675–740.

Daniel, T. C., Muhar, A., Arnberger, A., Aznar, O., Boyd, J. W., Chan, K. M. A., et al. (2012). Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109 (23), 8812–8819. doi:10.1073/pnas.1114773109

de Groot, R. S., Wilson, M. A., and Boumans, R. M. J. (2002). A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ. 41 (3), 393–408. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7

Dunlap, R. E., and York, R. (2008). The globalization of environmental concern and the limits of the postmaterialist values explanation: Evidence from four multinational surveys. Evid. Four Multinatl. Surv. 49 (3), 529–563. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2008.00127.x

Dzhambov, A., Hartig, T., Markevych, I., Tilov, B., and Dimitrova, D. (2018). Urban residential greenspace and mental health in youth: Different approaches to testing multiple pathways yield different conclusions. Environ. Res. 160, 47–59. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2017.09.015

Fisher, B., Turner, R. K., and Morling, P. (2009). Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecol. Econ. 68 (3), 643–653. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.09.014

Fleming, C. M., and Cook, A. (2008). The recreational value of Lake McKenzie, Fraser Island: An application of the travel cost method. Tour. Manag. 29 (6), 1197–1205. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2008.02.022

Garrett, J. K., White, M. P., Huang, J., Ng, S., Hui, Z., Leung, C., et al. (2019). Urban blue space and health and wellbeing in Hong Kong: Results from a survey of older adults. Health and Place 55, 100–110. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.11.003

Groote, U. (2009). Environmental labeling, protected geographical indications and the interests of developing countries. Estey J. Int. Law Trade Policy 10 (1), 94–110.

Hanemann, M., Loomis, J., and Kanninen, B. (1991). Statistical efficiency of double-bounded dichotomous choice contingent valuation. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 73 (4), 1255–1263. doi:10.2307/1242453

Harrison, P. A., Dunford, R., Barton, D. N., Kelemen, E., Martín-López, B., Norton, L., et al. (2018). Selecting methods for ecosystem service assessment: A decision tree approach. Ecosyst. Serv. 29, 481–498. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.09.016

Hernández-Blanco, M., Costanza, R., and Cifuentes-Jara, M. (2021). Economic valuation of the ecosystem services provided by the mangroves of the Gulf of Nicoya using a hybrid methodology. Ecosyst. Serv. 49, 101258. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2021.101258

Hirons, M., Comberti, C., and Dunford, R. (2016). Valuing cultural ecosystem services. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 41 (1), 545–574. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085831

Hornung, L. K., Podschun, S. A., and Pusch, M. (2019). Linking ecosystem services and measures in river and floodplain management. Ecosyst. People 15 (1), 214–231. doi:10.1080/26395916.2019.1656287

Inglehart, R. (1995). Public support for environmental protection: Objective problems and subjective values in 43 societies. PS Political Sci. Polit. 28 (1), 57–72. doi:10.2307/420583

Iniesta-Arandia, I., Garcia-Llorente, M., Aguilera, P. A., Montes, C., and Martin-Lopez, B. (2014). Socio-cultural valuation of ecosystem services: Uncovering the links between values, drivers of change, and human well-being. Ecol. Econ. 108, 36–48. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.09.028

Kirchhoff, T. (2012). Pivotal cultural values of nature cannot be integrated into the ecosystem services framework. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109 (46), E3146. doi:10.1073/pnas.1212409109

Kolstad, C. D., and Guzman, R. M. (1999). Information and the divergence between willingness to accept and willingness to pay. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 38 (1), 66–80. doi:10.1006/jeem.1999.1070

Li, J., Dong, S., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Li, Z., and Li, F. (2022). Effects of land use change on ecosystem services in the China–Mongolia–Russia economic corridor. J. Clean. Prod. 360, 132175. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132175

Liu, H., Hou, L., Kang, N., Nan, Z., and Huang, J. (2022). A meta-regression analysis of the economic value of grassland ecosystem services in China. Ecol. Indic. 138, 108793. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.108793

Martín-López, B., Gomez-Baggethun, E., Garcia-Llorente, M., and Montes, C. (2014). Trade-offs across value-domains in ecosystem services assessment. Ecol. Indic. 37, 220–228. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.03.003

Martín-López, B., Iniesta-Arandia, I., García-Llorente, M., Palomo, I., Casado-Arzuaga, I., Del Amo, D. A., et al. (2012). Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLoS ONE 7, e38970. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038970

Milcu, A. I., Hanspach, J., Abson, D., and Fischer, J. (2013). Cultural ecosystem services: A literature review and prospects for future research. Ecol. Soc. 18 (3), art44. Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/26269377. doi:10.5751/es-05790-180344

Morrison, G. C. (1997). Resolving differences in willingness to pay and willingness to accept: Comment. Am. Econ. Rev. 87 (1), 236–240.

Notaro, S., and Paletto, A. (2011). Links between mountain communities and environmental services in the Italian alps. Sociol. Rural. 51 (2), 137–157. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.2011.00532.x

Owen, L., Udall, D., Franklin, A., and Kneafsey, M. (2020). Place-based pathways to sustainability: Exploring alignment between geographical indications and the concept of agroecology territories in Wales. Sustainability 12 (12), 4890. doi:10.3390/su12124890

Pearce, D., and Barbier, E. (2013). “Economics of environment and development,” in Evidence for Hope: The search for sustainable development. Routledge, 172–188.

Plieninger, T., Bieling, C., Fagerholm, N., Byg, A., Hartel, T., Hurley, P., et al. (2015). The role of cultural ecosystem services in landscape management and planning. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 14, 28–33. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.02.006

Plieninger, T., Dijks, S., Oteros-Rozas, E., and Bieling, C. (2013). Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy 33, 118–129. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.12.013

Plott, C. R., and Zeiler, K. (2005). The willingness to pay–willingness to accept gap, the “endowment effect,” subject misconceptions, and experimental procedures for eliciting valuations. Subj. Misconceptions, Exp. Proced. Eliciting Valuations Am. Econ. Rev. 95 (3), 530–545. doi:10.1257/0002828054201387

Portney Paul, R. (1994). The contingent valuation debate: Why economists should care. Why Econ. Should Care 8 (4), 3–17. doi:10.1257/jep.8.4.3

Pretty, J., Peacock, J., Sellens, M., and Griffin, M. (2005). The mental and physical health outcomes of green exercise. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 15 (5), 319–337. doi:10.1080/09603120500155963

Pruckner, S., Bedford, J., Murphy, L., Turner, J. A., and Mills, J. (2022). Adapting to heatwave-induced seagrass loss: Prioritizing management areas through environmental sensitivity mapping. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 272, 107857. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2022.107857

Raymond, C. M., Kenter, J. O., Plieninger, T., Turner, N. J., and Alexander, K. A. (2014). Comparing instrumental and deliberative paradigms underpinning the assessment of social values for cultural ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 107, 145–156. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.07.033

Ressurreição, A., Gibbons, J., Dentinho, T. P., Kaiser, M., Santos, R. S., and Edwards-Jones, G. (2011). Economic valuation of species loss in the open sea. Ecol. Econ. 70 (4), 729–739. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.11.009

Saha, D., and Taron, A. (2023). Economic valuation of restoring and conserving ecosystem services of Indian Sundarbans. Environmental Development. 46, 100846. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2023.100846

Sayman, S., and Öncüler, A. (2005). Effects of study design characteristics on the WTA–WTP disparity: A meta analytical framework. J. Econ. Psychol. 26 (2), 289–312. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2004.07.002

Schaich, H., Bieling, C., and Plieninger, T. (2010). Linking ecosystem services with cultural landscape research. GAIA - Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 19 (4), 269–277. doi:10.14512/gaia.19.4.9

Sekaran, U. (2003). Research methods for business a skill building approach. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. Inc.

Shumka, S., Bego, F., Beqiraj, S., Paparisto, A., Kashta, L., Miho, A., et al. (2018b). The Vjosa catchment–a natural heritage. Acta ZooBot Austria 155 (1), 349–376.

Shumka, S., Meulenbroek, P., Schiemer, F., and Šanda, R. (2018a). Fishes of River Vjosa–an annotated checklist. Acta ZooBot Austria 155, 163–176.

Tunçel, T., and Hammitt, J. K. (2014). A new meta-analysis on the WTP/WTA disparity. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 68 (1), 175–187. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2014.06.001

White, M. P., Elliott, L. R., Gascon, M., Roberts, B., and Fleming, L. E. (2020). Blue space, health and well-being: A narrative overview and synthesis of potential benefits. Environ. Res. 191, 110169. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.110169

White, M. P., Pahl, S., Wheeler, B. W., Depledge, M. H., and Fleming, L. E. (2017). Natural environments and subjective wellbeing: Different types of exposure are associated with different aspects of wellbeing. Health and Place 45, 77–84. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.03.008

White, M. P., Wheeler, B. W., Herbert, S., Alcock, I., and Depledge, M. H. (2014). Coastal proximity and physical activity: Is the coast an under-appreciated public health resource? Prev. Med. 69, 135–140. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.09.016

Willis, C. (2015). The contribution of cultural ecosystem services to understanding the tourism–nature–wellbeing nexus. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 10, 38–43. doi:10.1016/j.jort.2015.06.002

Wilson, M. A., and Carpenter, S. R. (1999). Economic valuation of freshwater ecosystem services in the United States: 1971–1997. Ecol. Appl. 9 (3), 772–783. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(1999)009[0772:EVOFES]2.0.CO;2

Xu, X., Jiang, B., Tan, Y., Costanza, R., and Yang, G. (2018). Lake-wetland ecosystem services modeling and valuation: Progress, gaps and future directions. Ecosyst. Serv. 33, 19–28. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.08.001

Zhongmin, X., Guodong, C., Zhiqiang, Z., Zhiyong, S., and Loomis, J. (2003). Applying contingent valuation in China to measure the total economic value of restoring ecosystem services in Ejina region. Ecol. Econ. 44 (2-3), 345–358. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00280-X

Keywords: Vjosa Valley, ecosystem services, willingness to pay, willingness to accept, total economic value

Citation: Kokthi E, Guri F, Shehu E, Sovinc A and Gura KS (2023) How much does it cost the river near my house? An integrated methodology to identify a value for ecosystemic services (The case of Vjosa Valley in Albania). Front. Environ. Sci. 11:1166874. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1166874

Received: 15 February 2023; Accepted: 27 March 2023;

Published: 11 August 2023.

Edited by:

Otilia Manta, Romanian Academy, RomaniaReviewed by:

Valentina Ndou, University of Salento, ItalyAnuradha Iddagoda, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka

Copyright © 2023 Kokthi, Guri, Shehu, Sovinc and Gura. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kriselda Sulcaj Gura, a3Jpc2VsZGFzdWxjYWpAZ21haWwuY29t

Elena Kokthi1

Elena Kokthi1 Kriselda Sulcaj Gura

Kriselda Sulcaj Gura