- Institute of Agriculture and Tourism, Poreč, Croatia

Large and monumental trees are important elements of the ecosystem and represent valuable ecological, environmental, and historical heritage. Different countries have different strategies to protect such trees; most often, through the creation and reference to catalogues of the most valuable, old, big, or monumental trees on the territory. In Croatia, such an inventory has not yet been implemented. In order to create a database and catalogue of super-trees on the territory of Istria, in 2022, we launched a citizen science action to find out the locations of large, old, and valuable trees in Istria with the help of the public. The result of the action is a geo-referenced census of 64 ʻsuper-treesʼ in Istria in the form of an online Catalogue created in ArcGIS StoryMaps application. We proved that it is possible to efficiently and quickly create a catalogue that will serve to protect monumental trees. This Catalogue is the first step in creating a regional or national register.

1 Introduction

1.1 Importance of large old trees

Large old trees are some of the biggest and oldest living organisms on the Earth (Lindenmayer et al., 2012). They are important elements of the ecosystem and represent valuable ecological, environmental, and historical heritage (Mattioni et al., 2020). Large old trees are individuals established over a long period and which have survived environmental changes and human interventions. Accordingly, they represent a distinctive and valuable source of genetic diversity (Lindenmayer and Laurance, 2017; Mattioni et al., 2020). Their ecological role includes the influence on the hydrological regime, nutrient cycling, carbon storage, rainfall interception, and micro-and meso-climatic conditions (Lindenmayer and Laurance, 2017; Lindenmayer, 2017). Large old trees provide substrates for other plants and fungi (epiphytes, lichens, mosses). Tree canopy, cavities, bark, and roots represent sheltering and nesting places for various microorganisms, invertebrates, and vertebrates (Lindenmayer and Laurance, 2017). In that way, they can act as biodiversity hotspots. Large trees also provide food resources for a wide range of animals in the form of fruits, flowers, seeds, foliage, pollen, and nectar (Lindenmayer and Laurance, 2017; Lindenmayer, 2017). Large trees are often reproductively dominant trees in an area and can act as hotspots for propagules that have come by seed-dispersing animals. In that way, they can be focal points for vegetation regeneration in agricultural landscapes (Fischer and Lindenmayer, 2002; Lindenmayer et al., 2012; Lindenmayer, 2017). The scientific work of Lutz et al. (2018) revealed that large-diameter trees make up almost half of the mature forest biomass and carbon storage worldwide. These trees are also part of human identity and cultural heritage and have aesthetic, symbolic, religious, and historical character (Blicharska and Mikusiński, 2014). In the last decade, the importance of large trees has been further emphasised by the theory of mother trees. According to this theory, the trees in a forest are linked to each other via an older tree called a “mother” or “hub” tree. This connection is crucial in energy transfer, regeneration capacity, and forest survival (Simard, 2021). Regarding the terminology in the literature, different terms (ancient, veteran, notable, champion, old, monumental, heritage, mother) are often used to describe large old trees depending on the particular interest (Nolan et al., 2020; Simard, 2021) We thus used the term ʻsuper-treesʼ which comprises all of the mentioned terms and meanings.

1.2 Threats to large old trees

Large old trees are exposed to different environmental and anthropogenic threats. Environmental threats include windstorms, fire, drought, insect attacks, pathogens, invasive plant, animal species, and climate change (Lindenmayer, 2017). Most of these environmental threats have a human origin, such as introduced new invasive species and pathogens, as well as anthropogenic climate change. Some anthropogenic threats are logging, land clearing, landscape fragmentation, air pollution and the establishment of human infrastructure (Lindenmayer and Laurance, 2017).

1.3 Problems with the management of large old trees

The management of large old trees can be complicated because of various factors. Lindenmayer and Laurance (2017) state that key attributes of those trees can contribute to their faster deterioration. For example, the tree’s extreme height and large cavities may weaken a stem and increase the risk of collapse. Therefore, they threaten human safety in populated areas (Carpaneto et al., 2010). Large old trees are sometimes difficult to protect from environmental hazards, such as pesticide spray drift and exposure to massive logging and pathogens. Furthermore, traditional protection methods, such as including a tree within in a reserve, are not always possible on agricultural land and in urban areas. Individual large old trees can be exposed to different environmental and anthropogenic factors that can manifest in different ways in the ecosystem (Lindenmayer, 2017). Because of all these factors, the protection of each tree should be approached in a manner appropriate for that ecosystem.

1.4 Conservation management of large old trees

Due to various environmental and anthropogenic threats to large old trees, conservation management must be focused on limiting such threats (Lindenmayer et al., 2014). There are two main approaches to managing large old trees: limiting the rate of removal and mortality of existing trees and protecting the tree recruitment and maturation in places where large specimens are most likely to develop (Lindenmayer et al., 2014; Lindenmayer and Laurance, 2017). In terms of protecting large old trees in populated areas, their potential threat to human safety should also be considered (Blicharska and Mikusiński, 2014). Regular pruning and restricted access zones in urban areas can help manage those specimens (Lindenmayer and Laurance, 2017). Some examples of promoting tree recruitment are controlling invasive plants, reducing grazing pressure, and reducing the use of herbicides and fertilisers in agricultural landscapes (Lindenmayer et al., 2014). Lindenmayer and Laurance (2017) stated that tree protection policy could take place at the following levels: individual tree level, landscape and regional level and over a prolonged temporal scale. Policies and conservation management of large old trees should be oriented on large spatial scales (landscape and regions) and long-lasting to achieve the best results (Lindenmayer et al., 2014). Blicharska and Mikusiński (2014) concluded that incorporating large old trees’ social and cultural value can strengthen the policies and conservation management. Although the social value is usually very contextual and limited in place, managing the trees on a large scale can be difficult. One of the most important first steps for the conservation of large old trees is the creation of a register of such trees (Lindenmayer et al., 2014). For example, citizen science can be a successful mean of gathering information about large old trees on large scales and long time periods (Lindenmayer and Laurance, 2017; Nolan et al., 2020). Such registers containing information on distribution and condition of large old trees across some country could be beneficial for monitoring changes in trees and environment generally. Additionally, including the tree in the register should ensure the protection of being easily pruned, damaged or removed. Nolan et al. (2020) highlighted the importance of developing citizen science databases such as this for research and conservation of trees. Furthermore, the promotion of large old trees through registers could be of particular interest for attracting tourist (Lindenmayer, 2017).

1.5 Catalogues in other countries

Some countries have no inventories of its super-trees (Finland, Norway, Serbia), while others have well-formed and maintained catalogues of the most valuable, old, big or monumental trees on the territory (Bosnia and Herzegovina, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, United States). Approaches and strategies for tree cataloguing and protection are different.

1.5.1 Bosnia and Herzegovina

In Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), old trees located near historic-cultural monuments and sacred places are listed in the regional catalogue (Memić et al., 2020). The Institute for the protection and use of cultural, historical and natural heritage of Tuzla Canton (BiH) recorded and valorised over thirty localities with individual memorial trees or groups of trees, parks, gardens and arboretums. These trees are listed in the catalogue “Memorial trees in the cultural landscape of the Tuzla region.”

1.5.2 Hungary

In Hungary, the largest trees were first catalogued in 2005 in the book “Hungary’s Largest Trees—Dendromania.” Based on the book, the author created an online catalogue1. The catalogue includes only those genera that achieve impressive sizes in terms of both circumference and height. Citizens can contribute by reporting large trees. Each reported tree is then examined by one expert responsible for maintaining the catalogue.

1.5.3 France

The ARBRES association (Remarkable Trees: Assessment, Research, Studies and Safeguarding), a non-profit association together with National Forestry Office (ONF), has been working on the preservation and protection of remarkable trees in France. They have compiled data about more than 700 trees all over the country into an interactive map available to users2. Via a descriptive form sent to the ARBRES association, citizens are able to report a remarkable tree that meets specific criteria such as age, physical characteristics, morphology, historical, and religious significance, ecological function, and rarity. Remarkable trees can get a label, which has no legal value but it is recognized by the national body for nature protection.

1.5.4 Italy

In Italy, monumental trees of particular landscape, naturalistic, monumental, historical, and cultural value are legally protected. The list of these trees is established and published within the Law 10/2013 and special Decree n. 5,450 from 19/12/2017 (Ministero delle politiche Agricole alimentari e forestali, 2013; Ministero delle politiche Agricole alimentari e forestali, 2017). The List of monumental trees3 of Italy includes 3,300 trees all over the country. The Decree also provides the principles and criteria (age, size, shape, ecological value, botanical rarity, plant architecture, landscape and historical-cultural-religious value) for their census. To ensure maximum protection for monumental specimens, the law prohibits their felling and carrying out of any interventions. The census of monumental trees is carried out by the Municipalities, under the coordination of the Regions. The census is done through verification of reports from citizens, associations, schools, local authorities, etc. The Regions draw up regional lists based on proposals from Municipalities and send them to Ministry of Agricultural Food and Forestry Policies for a national list.

1.5.5 United Kingdom

United Kingdom has a national programme of inventory ancient, veteran and notable trees called the “Ancient Tree Inventory” (ATI). Three charities (Ancient Tree Forum—ATF, Tree Register of the British Isles—TROBI and the Woodland Trust—WT) from the United Kingdom conducted the five-year citizen science project that resulted in a database of over 200,000 tree records (Nolan et al., 2020). Each record includes the location and photo of the tree, information about its condition, girth, accessibility and other characteristics. “Ancient Tree Inventory” (ATI)4 is presented in the form of an interactive map. Each citizen can add a new tree record, but each record must be verified by the experts according to the criteria in order to enter the register. There are three categories of the trees—notable, veteran, and ancient. The data collected by the Ancient Tree Inventory is used by scientists to study the oldest trees in the United Kingdom.

1.5.6 United States of America

In the United States, the protection of trees is driven by American Forests, the oldest national non-profit conservation organisation. Almost a century ago, they launched a citizen science campaign to identify the largest and oldest living specimens of trees. Their goal was to raise awareness about the ecosystem services of big trees and to involve people in their preservation. As a result, in 2021 National Register of Champion Trees5 was created. The list of champions features 561 trees across 39 states. The champions in this context refer to the largest tree of a specific species, determined by evaluating only its height, trunk circumference, average crown spread, and awarding points accordingly. Citizens have the option to nominate a tree for inclusion in the Register either through an online form or by participating in the state-level Champion Tree Program. However, each nomination is subject to verification by experts before being accepted.

1.6 Super-trees in Croatia

In Croatia, the only effort in the sense of inventory and valorisation of super-trees is the application for the European Tree of the Year by the Environmental Partnership Association (EPA). EPA is a consortium of six foundations from Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia. The European Tree of the Year contest started in 2011 as an upgrade to a similar contest organised by the Czech Environmental Partnership Foundation. The purpose of this contest is to emphasise the importance of trees in the natural and cultural heritage. The competition is focused not only on the tree’s size and age but its story and significance for people. Croatia has been participating in this contest since 2017. The national coordinator of the Republic of Croatia participating in the contest is the Public Institution for Management of Protected Natural Areas of Dubrovnik-Neretva County. They organise and conduct a national competition known as the Croatian Tree of the Year in cooperation with the Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology of the University of Zagreb, Hrvatske šume d.o.o., and the Croatian Agrometeorological Society. The winner of this national competition enters the European Tree of the Year contest. Aware of the importance of monumental trees and the lack of their systematic inventory or protection in Croatia, we decided to create a Super-Trees Catalogue for a pilot region Istria (Croatia), through a citizen science action. The hypothesis was that a citizen’s action with following coordinated expert activities can rapidly lead to the creation of a Super-Trees Catalogue containing all the necessary data about trees for their further investigation and protection.

2 Materials and methods

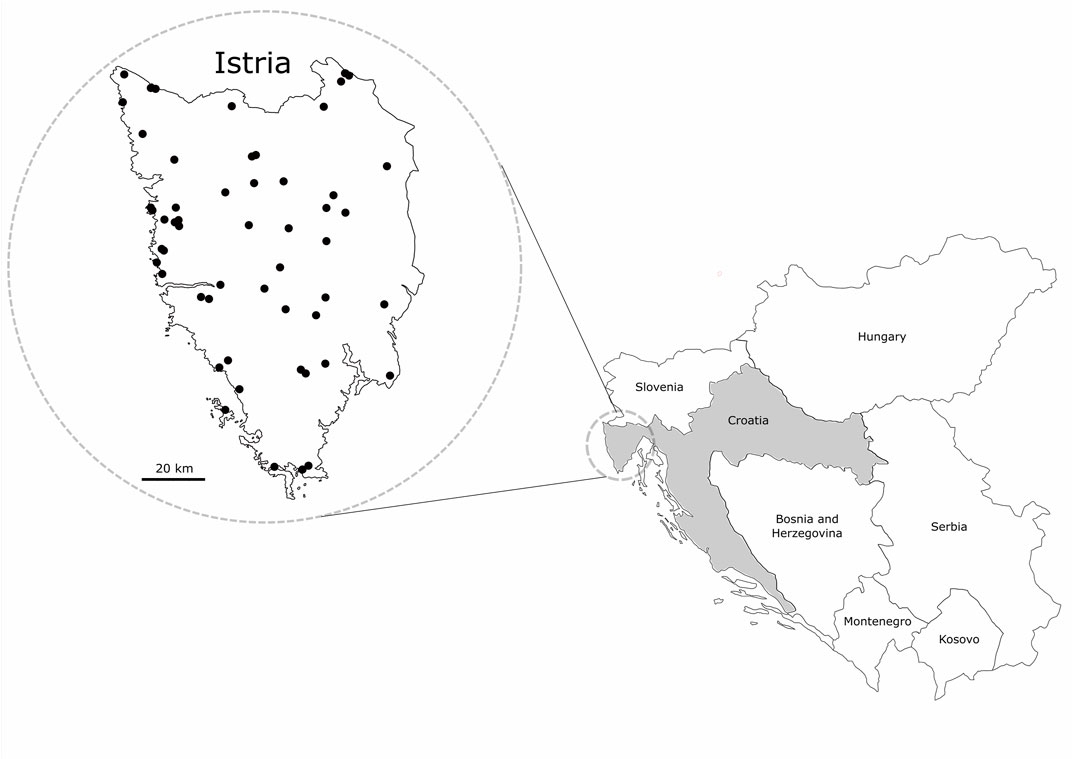

2.1 Study area

We conducted our campaign in the Istria County (Istrian peninsula, Croatia) situated on the northeastern coast of the Adriatic Sea (Figure 1). Istria County covers an area of 2,815 m2 with 195,794 inhabitants (according to the population census from 2021). Based on the geological composition and different types of soil, Istria can be divided into three geomorphological units: White Istria (mountainous part), Gray Istria (flysch), and Red Istria (low limestone-dolomite plateau). The climate of the coastal part of Istria is a moderate Mediterranean climate; moving away from the sea, it turns into a moderate continental one. The vegetation’s richness and diversity reflect the geographical position, relief, soil, and climate (Croatian Enyclcopaedia, 2021).

2.2 Citizen science campaign—Primary data collection

In 2021, we conducted the first preliminary field survey and collected data about seven big and old trees in the region. From February to May 2022, the citizen science campaign “Look up for the super-tree in Istria” was launched. The purpose of the campaign was to collect records on the location of large, old, and valuable trees in Istria with the help of the public. Citizens were asked to report the location, species, and story connected to the largest, oldest, or most fascinating trees they are aware of in Istria. Subsequently, in direct communication, we updated reports with additional data on the tree’s health (based on its external appearance), accessibility, and other characteristics. With the aim of reaching the maximum number and different categories of citizens the campaign it was published on the website, social networks (Facebook, Instagram), on the radio, and in local newspapers. Free-form reports from citizens were gathered through various channels such as social media, emails, phone calls, and face-to-face interactions. These reports were then sorted, classified, and archived in an Excel database.

2.3 Data collection in the field and catalogue creation

Fieldwork was carried out during October and November 2022. During the fieldwork, we visited and processed most of the reported trees. Trees were identified based on the citizen science campaign. Some of the trees did not have enough precise coordinates or location description and could not be found. Moreover, we expanded the database with additional trees observed in the field. These additional trees were included based on either our personal observations or through discussions with local individuals during fieldwork. All data on each tree was collected using a mobile application (ArcGis Survey 123). This data comprised: location name, GPS coordinates, position, species, girth, average height, average canopy width, health condition, age, and interesting facts (through informal verbal reporting) accompanied by photos (Supplementary Table S1). The girth of each tree was measured with a rolling meter at a height of 1 m. The width of the canopy was measured so that the edges of the canopy were projected onto the ground, and the distance from one edge to the other was measured. All data collected with the mobile application were automatically sorted into a database of the super-trees in Istria. An online public access Catalogue was created in ArcGIS Story Maps application.

While the criteria were not mandatory for citizens to submit a report, a tree had to meet at least one of the following categories to be included in the Catalogue: 1) Notable trees; 2) Cultural heritage; 3) Rare trees. Category “Notable” includes trees that stand out in the environment based on height, trunk girth, canopy shape, growth mode, ecological role, etc. Regarding the trunk girth, Attachment to circular letter n. 477 from 09/03/2020 was used as a reference document (Ministero delle politiche Agricole alimentari e forestali, 2020). This document prescribes the minimum values of trunk girth per species. Category “Cultural heritage” includes trees with a specific background story and special meaning/association to people, or very old trees. The category “Rare trees” includes plant species that are rare for a specific geographic area.

3 Results and Discussion

The citizen science campaign “Look up for the super-tree in Istria” resulted in significant public interest; we received 56 reports on potential trees within 4 months. During eight fieldwork visits, we visited and collected data for the reported trees and additional 23 trees. Based on the defined criteria, in the Catalogue, we included a total of 64 trees (Supplementary Tables S1, S2; Figures 2, 3). There are 59 trees whose features correspond to the category “Notable” (Figure 2), while the category “Cultural heritage” (Figure 3) includes 28 trees. There are no trees in the “Rare trees” category. Some of the trees belong to more than one category.

FIGURE 2. Examples of notable trees in Istria: (A) Platanus orientalis in Cerovlje; (B) Quercus pubescens in Gologorički Dol; (C) Tilia platyphyllos in Slum.

FIGURE 3. Examples of cultural heritage trees in Istria: (A) Quercus cerris in Veleniki is a part of the cultural identity of the locals, and its silhouette can be found on the logo of their bocce club. According to legend, in ancient times, on its way from Africa, a swallow left an acorn at that location, from which a tree grew; (B) Celtis australis in Peroj is the centre of the settlement and a gathering place for the locals. The illustration shows a settlement rebuilt after 1,657 by the Montenegrins who settled in this area at that time. A tree was planted in the center of the settlement as a monument to their identity (oral tradition).

An online Catalogue6 containing a map and relevant information on 64 super-trees in Istria was created (Supplementary Figure S1A). Among the 64 processed trees, we identified 24 different plant species, and the most represented genera were Quercus (oaks) and Celtis (hackberries). Regarding the girth of the trunk, the largest was Castanea sativa, with a girth of 10.3 m, followed by Tillia platyphyllos (7.1 m) and two Quercus pubescens (6 m). Among the other largest species in terms of trunk girth are Platanus orientalis, Quercus cerris, Pinus halepensis, Quercus ilex, Celtis australis, and Populus nigra (Supplementary Table S2;). While the attributed record of tree girth and canopy width is correct and reliable, there are potentially biased records of tree height. Errors may occur because the height was measured with a laser at a fixed point on the tree and by the visual transmission of the distance to the top. In the future, developing a more reliable method for determining tree height will be necessary.

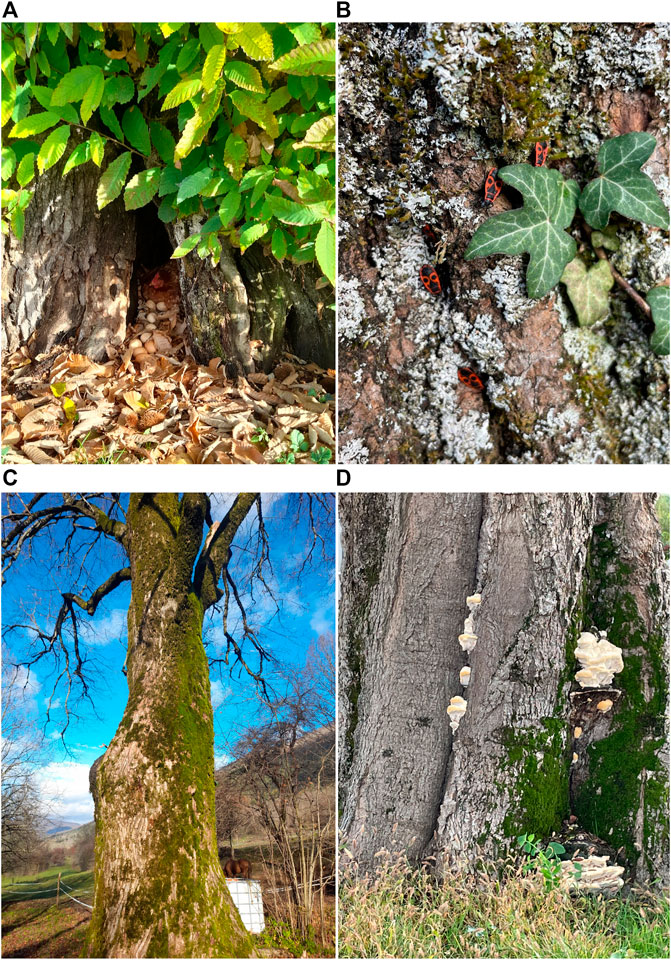

Fieldwork confirmed that large old trees are suitable habitats for various animals. Many recorded trees had saproxylic organisms present on them, like lichens, moss, and fungi. Furthermore, some trees have large trunk cavities, which provide shelter and nesting places for some animals (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Super-trees host other species: (A) The super-tree chestnut hosts a hen with eggs; (B) The firebug on Tillia platyphyllos tree; (C) Tillia platyphyllos tree covered with the moss; (D) Celtis australis as a habitat for fungi.

For centuries, the heart of villages in Istria has been marked by trees encircled with stone benches. These trees served as a central gathering place for locals to meet, socialize, and discuss. The most commonly found trees at these centers were Mediterranean hackberry (Celtis australis), oaks (genus Quercus), mulberries (genus Morus), and linden trees (genus Tillia) (Istrian Encyclopaedia; Ivetac, 1998; Vince Pallua, 2022). Mediterranean hackberry is very favoured and common in whole Istrian peninsula, except on its northeastern part. It is planted in visible places, in squares and in the form of tree rows (Ivetac, 1998). During the fieldwork and the conversation with people, we noticed a great number of hackberries in Istria, there are even settlements with over 300 hackberry trees in it (Mugeba, Istria). Furthermore, the hackberry from Medulin (Istria) won the title of Croatian Tree Of The Year 2020 and participated in the European Tree of the Year contest. The northeastern part of Istria is characterized by linden trees—the holy tree of Slavs, related to their migrations in the past (Vince Pallua, 2022). During the fieldwork, we noticed that almost every settlement in Istria has a tree that represents its center. While the significance of some trees has vanished due to the decline of the custom of meeting in the open, others have been conserved as a symbol of this tradition. Additionally, some of these trees still serve as places of gathering and socializing, bringing people together in the spirit of community and friendship. Some local communities and tree owners on private parcels make great efforts to maintain and preserve their valuable trees, however, their capacity to do so is limited to some extent. On the other hand, aware of the importance of such trees, several of them are maintained by people even though they do not grow on their property. Most of the trees in our Catalogue are currently not under any official protection. Only the pine trees from Karojba are protected as a natural monument—a rare example of trees, the cypress in Kašćerga is a monument of park architecture, an individual tree, and the oaks and cedars in St. Ana are a monument of park architecture, a group of trees (Natura Histrica, 1996). Large old trees can achieve better protection if they get special status under global-level initiatives, such as UNESCO World Heritage (Lindenmayer and Laurance, 2017). Furthermore, Blicharska and Mikusiński (2014) stated that some trees of a particular height, age, and dimension can be included in the European Union Habitat Directive (EEC, 1992) as “habitats of community interest” acting as habitats or even entire ecosystems. The positive response received by the online Catalogue from the public indicated their desire to remain engaged with the subject even after the study had concluded. Through our interactions with them, we observed that the large old trees held significant emotional and cultural value for the people. Consequently, they continued to contribute data, recognizing its potential long-term benefits for the community. Additionally, there was significant media attention and interest in taking measures to safeguard and appreciate these trees. We propose creating an online form for reporting super-trees in order to enhance the primary data gathering by citizens. Every member of the public might upload a record by using an online database system, which would greatly simplify data storage. To ensure the Catalogue’s long-term success and full utilization, it is essential to create a national register. Our suggestion is to establish multiple local centers in Croatia that gather data and conduct field checks. These centers could potentially be associated with specific regions. In this sense, agreements were initiated with the relevant national authorities.

4 Conclusion

It is possible to create a catalogue of large and monumental trees quickly and with limited financial resources. Once created, it represents the basis for further protection management. As the first of three steps, we propose the creation of a National Register of Super-Trees, coordinated by a national nature protection body. Secondly, further scientific investigation is needed to understand the trees’ history and biological background. And finally, proper protective measures are necessary to ensure the ultimate goal, which is the long-term biodiversity preservation of important natural resources such as big trees.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BS conceptualized the study. BS, DD, MU, and DP designed the methodology and participated in data collection. BS and DD prepared the manuscript, analyzed data, and developed maps and Figures. DP and MU reviewed and edited the manuscript. BS and DP attained funding for project conduction and paper publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Istrian County, Developmental scientific programs and projects of budget users 3661, Position 220748, group 36-366 for 2022 year.

Acknowledgments

We thank the colleague Slavko Brana for the help in species determination and Marin Krapac for the help during field work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1154101/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

2https://www.arbres.org/label-national.htm.

3https://www.alberimonumentali.info/.

4https://ati.woodlandtrust.org.uk/.

5https://www.americanforests.org/champion-trees/champion-trees-registry/.

References

Blicharska, M., and Mikusiński, G. (2014). Incorporating social and cultural significance of large old trees in conservation policy. Conserv. Biol. 28 (6), 1558–1567. doi:10.1111/cobi.12341

Carpaneto, G. M., Mazziotta, A., Coletti, G., Luiselli, L., and Audisio, P. (2010). Conflict between insect conservation and public safety: The case study of a saproxylic beetle (osmoderma eremita) in urban parks. J. Insect Conserv. 14, 555–565. doi:10.1007/s10841-010-9283-5

Croatian Enyclcopaedia (2021). Istria. Available at: http://www.enciklopedija.hr/Natuknica.aspx?ID=28002 (Accessed December 9, 2022).

EEC (1992). Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora.

Fischer, J., and Lindenmayer, D. B. (2002). The conservation value of paddock trees for birds in a variegated landscape in southern New South Wales. 1. Species composition and site occupancy patterns. Biodivers. Conserv. 11, 807–832. doi:10.1023/A:1015371511169

Lindenmayer, D. B. (2017). Conserving large old trees as small natural features. Biol. Conserv. 211, 51–59. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.11.012

Lindenmayer, D. B., Laurance, W., Franklin, J. F., Likens, G. E., Banks, S. C., Blanchard, W., et al. (2014). New policies for old trees: Averting a global crisis in a keystone ecological structure. Conserv. Lett. 7, 61–69. doi:10.1111/conl.12013

Lindenmayer, D. B., and Laurance, W. (2017). The ecology, distribution, conservation and management of large old trees. Biol. Rev. 92, 1434–1458. doi:10.1111/brv.12290

Lindenmayer, D., Laurance, W., and Franklin, J. (2012). Global decline in large old trees. Science 338, 1305–1306. doi:10.1126/science.1231070

Lutz, J. A., Furniss, T. J., Johnson, D. J., Davies, S. J., Allen, D., Alonso, A., et al. (2018). Global importance of large-diameter trees. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27, 849–864. doi:10.1111/geb.12747

Mattioni, C., Ranzino, L., Cherubini, M., Leonardi, L., La Mantia, T., Castellana, S., et al. (2020). Monuments unveiled: Genetic characterization of large old chestnut (Castanea sativa mill) trees using comparative nuclear and chloroplast DNA analysis. Forests 11 (10), 1118. doi:10.3390/f11101118

Memić, K., Hadžimusić, S., and Djedović, R. (2020). Memorijalna stabla u kulturnom krajoliku tuzlanske regije. Tuzla (Bosnia and Herzegovina): JU zavod za zaštitu i korištenje kulturno-historijskog i prirodnog naslijeđa tuzlanskog kantona. Tuzla, Bosne: JU Muzej istočne Bosne Tuzla.

Ministero delle politiche Agricole alimentari e forestali, (2020). Attachment to circular letter n 477 from 09/03/2020. Roma, Italy: Circonferenze minime indicative per il criterio dimensionale.

Ministero delle politiche Agricole alimentari e forestali, (2017). Decree n 5450 from 19/12/2017. Roma, Italy: Decreto di approvazione dell'elenco nazionale degli Alberi Monumentali.

Ministero delle politiche Agricole alimentari e forestali, (2013). Law 10/2013 from 14/1/2013, n 10: Norme per lo sviluppo degli spazi verdi urbani. Roma, Italy: Ministero.

Natura Histrica (1996). Protected areas. Available at: https://www.natura-histrica.hr/hr/zasticene-prirodne-vrijednosti (Accessed January 25, 2023).

Nolan, V., Reader, T., Gilbert, F., and Atkinskon, N. (2020). The ancient tree inventory: A summary of the results of a 15 year citizen science project recording ancient, veteran and notable trees across the UK. Biodivers. Conserv. 29, 3103–3129. doi:10.1007/s10531-020-02033-2

Simard, S. (2021). Finding the mother tree, discovering the wisdom of the forest. New York, United States: Knoph.

Keywords: large trees, database, GIS, register, heritage

Citation: Sladonja B, Damijanić D, Uzelac M and Poljuha D (2023) Catalogue of super-trees in Istria (Croatia) created as a result of the citizen science action. Front. Environ. Sci. 11:1154101. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1154101

Received: 30 January 2023; Accepted: 27 April 2023;

Published: 10 May 2023.

Edited by:

James Kevin Summers, United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), United StatesReviewed by:

Jess K. Zimmerman, University of Puerto Rico, Puerto RicoLeah Sharpe, United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), United States

Copyright © 2023 Sladonja, Damijanić, Uzelac and Poljuha. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Danijela Damijanić, ZGFuaWplbGFkQGlwdHBvLmhy

Barbara Sladonja

Barbara Sladonja Danijela Damijanić

Danijela Damijanić Mirela Uzelac

Mirela Uzelac Danijela Poljuha

Danijela Poljuha