- Department of Media and Communication, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

The aim of this study was to develop and validate multidimensional criteria that can be used to evaluate fashion brand ESG management. This research used both qualitative and quantitative research methods to derive multi-dimensional and wide-ranging questions that could help explain fashion brand ESG with a high level of detail. A Delphi study was conducted with a group of 30 professionals to derive the initial items for fashion brand ESG management, and these items were used to design a questionnaire that was then administered to 800 consumers. Based on the results of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, 13 items were used to construct the scale. Convergent and discriminant validity were also verified between the factors. Finally, it was confirmed that the items on the ESG practices scale significantly affected a fashion brand’s reputation and consumer intention to purchase that brand as mediated by reputation. The results of this research are expected to provide a theoretical framework for future ESG research that can help fashion brands achieve more effective ESG management and increase their reputation and sales.

1 Introduction

Environmental pollution is a significant global issue, and the fashion industry is assigned substantial blame for this problem. One reason for this is that apparel manufacturing requires enormous volumes of energy and water (Jia et al., 2020). Moreover, fast fashion—which involves continuously offering new styles at affordable prices—has greatly increased the amount of clothing produced and discarded; textile production now accounts for an estimated 20% of global water pollution (European Parliament, 2022). The fashion industry also accounts for up to 10% of global carbon dioxide emissions (Bloomberg, 2022). Further, it takes 2,700 L of water—the amount that the average person drinks in two and a half years—to make one cotton shirt (World Resources Institute, 2017). In response to these issues, the United Nations (UN) has launched the Alliance for Sustainable Fashion, and the European Union (EU) has announced its intention to end fast fashion by 2030.

This situation involving fast fashion is just one example of how the global economic development and industrialization that accelerated beginning in the late 20th century has led to the emergence of serious problems such as indiscriminate environmental destruction and pollution; widening inequality between countries, regions, and classes; deepening inequities in distribution; and the deterioration of overall human quality of life. As a separate development, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to rapid paradigm innovation and perspective shifts globally in all fields, including politics, the economy, society, culture, and education (OECD, 2020). Accordingly, there has been substantially increased interest in ESG practices that emphasize and respect corporate social, eco-friendly, ethical responsibility, and transparency worldwide (McKinsey, 2019). ESG emphasizes the importance of publicity, transparency, and accountability by combining these three nonfinancial elements and using them as a lens through which to view all areas of a company’s activities (Galbreath, 2013). With their focus on reducing carbon fuel emissions and building circular economies, ESG practices—which aim to strengthen corporate social contributions and establish transparent governance structures—are expected to become increasingly prominent characteristics of a firm (Ben-Amar et al., 2017; Sam-Jeong KPMG, 2020).

When the concept of ESG was first proposed, there were concerns about its effects on corporate activity, disclosure, and R&D costs, but research continues to confirm that ESG has a positive effect in generating long-term profits, enhancing corporate value, and improving social reliability (Provasnek et al., 2017). For example, companies that obtain a high ESG evaluation index by engaging in voluntary and continuous ESG activities can implement sustainable management that produces clear social support and brand value, which are lacking among companies with low evaluation indices (Muñoz-Torres et al., 2018). Based on the results that have been obtained to this point, following ESG practices is currently recognized as a key driver of increased corporate value while ensuring sustainable management and company growth.

When judging the effects of ESG efforts, it is necessary to consider brand reputation, which has recently increased in both academic and practical importance. Brand reputation is a constant and universal type of company value evaluation that forms gradually and is built over time through sincere communication and trust-building with consumers (Davies et al., 2003). It is also a key strategy that is essential for sustainable management in helping companies maintain a good reputation while taking the lead in domestic and international markets by gaining an edge in good faith competition with other companies. This means that, brand reputation—in contrast to brand image—is a more long-term, permanent, authentic, and reliable concept that is a positive strategic element for corporate development (Dowling & Roberts, 2002).

In the context of the present work, brand reputation is expected to be closely related to following ESG practices in the pursuit of sustainable management and growth, which are the ultimate goals of a company. Continuous and sincere ESG management is expected to not only positively influence the brand reputation of a company but also induce favorable consumer intentions and actions through brand reputation as a mediator. This research focuses on the effects of ESG practices on brand reputation and consumers’ purchase intentions with a specific focus on fashion brands, for which ESG practices represent a particularly important aspect of sustainable management.

Fashion products are highly influenced by season and are sensitive to trends, and their performance is substantially affected by subjective evaluations and consumer word of mouth (Cachon and Swinney, 2011). Therefore, fashion companies must survive fierce market competition every season and respond to the demands of consumers through creative and aesthetic product development (Cataldi et al., 2010). This means that fashion brands with positive reputations are expected to gain advantages in terms of sales and management performance compared to brands without positive reputations. Because of this increased importance of brand reputation for fashion companies, along with the importance of corporate reliability and consumer preference, the strategic importance of ESG activities for sustainable management has generated substantial discussion in the global fashion industry over the past decade (DiBenedetto, 2017; Gupta, 2019; Jiménez-Zarco, 2019; Gwilt, 2020).

The need for sustainable supply chain management is being emphasized due to the increase in demand due to globalization and the increase in population, as well as concerns about the environment. Companies need a lot of tangible and intangible assets to operate sustainably (Sarkis et al., 2011), and having the ability to continuously supply necessary resources and adapt to changing circumstances is key to a business’s competitive advantage (Aytekin et al., 2022). Sustainable supply chain management, which is emphasized here, is the management and coordination of logistics, information and capital flows between companies in the supply chain while considering all the goals of economic, environmental and social aspects of sustainable development resulting from the needs of customers and stakeholders (Seuring and Müller, 2008; Aytekin et al., 2022). In addition, a study that proposed a practical decision-making model in consideration of existing performance indicators and theories on sustainable supply chain management (Aytekin et al., 2022) emphasized that sustainability and supply chain management are driven by the concepts of corporate governance, ethical principles, and “Stakeholder theory.” Reputation is defined as the cumulative and empirical evaluation of stakeholders formed over a long period of time (Han et al., 2020). Therefore, management considering the environment, society, and governance of a company and careful consideration of various stakeholders’ evaluations of it are important factors that have a great impact on the sustainability of a company. Thus, the value and main purpose of this research are to develop major items that affect fashion brands’ ESG management decisions at a statistical level by reflecting the opinions of various stakeholders, and statistically verify the impact on consumers’ purchase intentions through reputation, a cumulative and empirical evaluation of ESG.

Academic and industrial actors currently agree on the importance and value of ESG practices, but detailed strategies and practical components necessary to incorporate ESG practices into business processes have yet to be properly developed. Because there is currently no scale that can measure the ESG practices of fashion brands, this research attempts to derive ESG practices that are suitable for fashion brands. ESG practices have an important influence on brand and corporate reputation, and they lead to purchasing behavior (Reputation Institute, 2021). The Reputation Institute (2021) reports on corporate, national, and regional reputations based on consumer surveys and media reports, and it recently added ESG to its corporate reputation measures; this institute uses a model called RepTrak to produce a reputation quotient and annually publishes the results. If this scale of fashion brand ESG practices significantly affects reputation and purchase intention, it can provide practical guidance for fashion brands to incorporate ESG activities and sustainable management, and therefore secure theoretical justification. With this background, the present work aims to derive effective practices for determining if a fashion brand is practicing ESG management through Delphi studies and verify the effects of fashion brands’ ESG practices on brand reputation and consumer purchase intention based on the derived items.

To fulfill this research aim, this study combines qualitative and quantitative research methods. Qualitative research provides transparent and verifiable research designs and involves rigorous data collection and analysis procedures (Sukma & Leelasantitham, 2022). Prior studies examining management decisions in the textile industry have used a methodological combination of qualitative research and quantitative research that included expert group interviews. For example, the opinions of expert groups were collected in a study that proposed a decision-making model applying sustainable supply chain management by applying each tool according to statistical methods (Aytekin et al., 2022). Therefore, this research collected initial questions with which to evaluate fashion brand ESG management through the Delphi technique, which is a qualitative research method, then verified the collected questions through a quantitative research method with strict standards to secure their reliability and validity. This research used the following research procedures.

First, the ESG practices of fashion brands are derived through a Delphi process involving expert interviews. Next, we empirically verify the derived ESG practices scale. A general survey is administered using this scale, and the findings of that survey are used to analyze and verify the influence of ESG management on brand reputation and purchase intention.

2 Literature review

2.1 Fashion brands and ESG management

With the COVID-19 outbreak, domestic and foreign companies suffered serious crises and chaos, including sudden shutdowns, infections and quarantine of employees, cross-border lockdowns, and the collapse of global supply chains. This has caused domestic and foreign companies to seriously consider future strategies and self-rescue measures for corporate survival, such as sustainable management, seeking coexistence with communities, communicating with consumers, and co-creation (Broadstock et al., 2021). Therefore, many companies have recently pushed for system reestablishment based on ESG practices (Brogi & Lagasio, 2019). In this context, ESG management and practices are expected to produce massive innovation and qualitative transformation in corporate culture in the future (Holden et al., 2017). Further, as the strategic value and influence of practicing ESG management in the global market expands and consumer demand keeps growing, international organizations and related ministries in major countries are obliged to reflect ESG activities in their corporate evaluations; individual industries should also present specific guidelines for ESG management (Clementino & Perkins, 2021).

ESG practices are increasingly being emphasized in all industries, including fashion, and it has recently been emphasized in both investments and production. Eco-friendly and ethical companies that make prosocial contributions and that have secured sustainable growth engines through ESG management will also have high investment value and stability, and countries in the United States and Europe are strengthening their socially responsible investment (SRI) strategies to focus on investing in companies with high ESG ratings (Van Duuren et al., 2016; Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, 2018). In an analysis of the correlations between ESG activities and corporate financial performance after the 1970s for 2,000 companies around the world, Friede et al. (2015) found a positive correlation for 63% of the analyzed companies. In another study, Alareeni and Hamdan (2020) verified that there was a significant correlation between ESG activity and financial performance among 500 US S&P companies.

Companies with strong sustainable management, growth capabilities, and resources can easily attract consumers and investors seeking sustainable or socially responsible investments. They can also experience enhanced brand reliability—and, in turn, reputation—which increases loyalty among consumers and investors. It is therefore expected that companies that do not actively engage in ESG will not be able to attract domestic and foreign investment in the future, thus falling behind in global competition. As the effect or value of ESG practices is bound to continue increase in the future, this study aims to analyze the effects of fashion brands’ ESG practices on brand reputation and consumer purchase intention.

Global fashion companies are already promoting and expanding ESG strategies such as increasing the production of recycled polyester materials, increasing the production of vegan materials to replace the use of animal products, strengthening eco-friendly dyeing techniques, and increasing the production of eco-friendly materials and packaging (Choi, 2021). With these efforts, the share of recycled polyester in the global market increased from 11% in 2010 to 15% in 2020 (Textile Exchange, 2021). Moreover, the global upcycling market grew 16.6% from $150 million in 2014 to $170 million in 2020, and the domestic upcycling market in Korea also increased by 60% from 2.5 billion won to 4 billion won over the same period (Ko, 2021).

ESG management is emerging as a key strategy for fashion companies aiming to expand the sustainability of operations, making social contributions, and creating common value and satisfaction for consumers. However, it must be noted that the three dimensions of ESG carry different weights under different circumstances; companies initiating ESG-guided operations will experiment with and modify strategies until they achieve a harmonious and stable mix that is sustainable over time.

2.2 Fashion brand ESG practices, reputation, and purchase intention

ESG practices are emerging as the best strategy for fashion companies to use to improve their reputations, particularly in light of the recent green consumer movement. Researchers have well established that a having a high brand reputation and value promote positive consumer responses such as purchase intention, satisfaction, and loyalty (Engel & Blackwell, 1990; Mosler et al., 2008). Brand image and reputation are particularly important in the fashion industry, which is largely driven by word-of-mouth publicity among consumers; reputation has a more direct impact on corporate performance in the fashion industry than it does in other industries (Kwon, 2022). It is therefore expected that fashion brands that incorporate ESG practices in their operations will see improvements in their reputations that actively induce consumer purchase intentions. The theoretical bases for this proposition are as follows.

First, among the analyses of the relationships between ESG activities and brand reputation and value, Jukemura (2019) identified that companies with excellent ESG activities secure greater competitive advantages through their better brand reputations, which in turn increase consumer confidence. McKinsey (2019) reported that a company’s ESG activities significantly affect their brand assets and value in addition to positively affecting financial performance. Giese et al. (2019) found that companies that actively engage in ESG generate increased profits through more efficient resource utilization and organization management, which increases consumers’ preferences for such companies and thus expands their competitive advantage. Muñoz-Torres et al. (2018) found that ESG activities significantly affect consumer social support and induce larger-scale socially responsible investment, which drives sustainable management over time.

Next, researchers examining the relationship between brand reputation and purchase intention have again confirmed that active engagement in ESG and corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices and other desirable management activities has significant positive effects on consumers’ purchasing intentions (Engel & Blackwell, 1990; Brown & Dacin, 1997; Han and Yu, 2004; Mosler et al., 2008). Engel and Blackwell (1990) confirmed that corporate reputation is an important factor in competitiveness that actively promotes purchase intentions, while Brown and Dacin (1997) confirmed that the positive corporate image and brand reputation generated from engaging in CSR activities lead to positive product evaluations and purchase intentions among consumers.

Ji and Seo (2021) detailed that a company’s continuous ESG activities promote positive purchase intentions by narrowing the psychological distance between consumers and companies, therefore enhancing intimacy and bonding. Han and Yu (2004) stated that corporate reputation is a more expansive concept than corporate or brand image, and they found that corporate reputation significantly affected purchase intention. Choi, Yoo, and Kwon (2011) also reported that Starbucks’ corporate reputation and social connection had positive effects on consumers’ purchase intentions.

3 Method

3.1 Research model and hypotheses

Based on the prospects and problems described in the literature review, this research intends to derive the ESG practices that are most applicable to fashion brands. This research is expected to have significant implications for fashion brands that in the initial stages of incorporating an ESG strategy across the entire industry as well as providing a scale that existing firms that practice ESG can use to measure their success. The measurement scale developed in this work is also expected to provide a theoretical framework for academic research related to ESG management and practices. The guiding research questions of the study that were used to develop the scale were as follows.

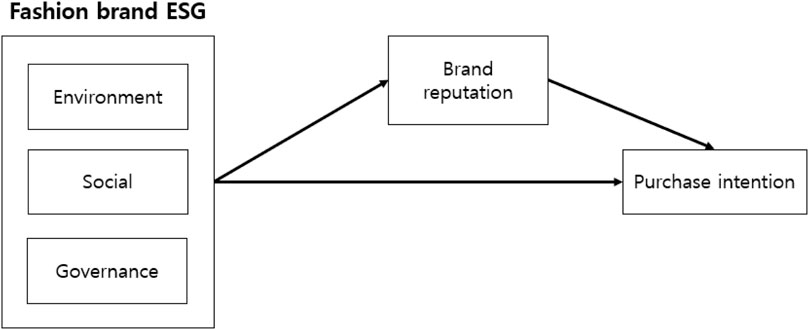

Research question 1. (RQ1): What practices should a scale for measuring a fashion brand’s compliance with ESG management standards include?RQ2: Does the newly developed scale demonstrate convergent validity?RQ3: Does the newly developed scale demonstrate discriminant validity?Further, the results discussed in the literature review confirm that company ESG and CSR activities significantly affect brand reputation and consumer purchase intention, but there have notably been no studies examining this relationship in the fashion industry in particular. Therefore, the aim of this research was to investigate the effect of fashion brands’ ESG activities on their brand reputations and on consumer purchase intention using the fashion brand ESG practices scale that were newly developed in this research. Figure 1 presents the research model used in this work. We proposed the following hypotheses to investigate the relationships of interest in this research.

Hypothesis 1. (H1): Fashion brand ESG practices will have a positive effect on purchase intention.H1-1: Fashion brand environmental practices will have a positive effect on purchase intention.H1-2: Fashion brand social practices will have a positive effect on purchase intention.H1-3: Fashion brand governance practices will have a positive effect on purchase intention.H2: The effect of fashion brand ESG practices on purchase intention will be mediated by brand reputation.H2-1: The effect of fashion brand environmental practices on purchase intention will be mediated by brand reputation.H2-2: The effect of fashion brand social practices on purchase intention will be mediated by brand reputation.H2-3: The effect of fashion brand governance practices on purchase intention will be mediated by brand reputation.

3.2 Research process

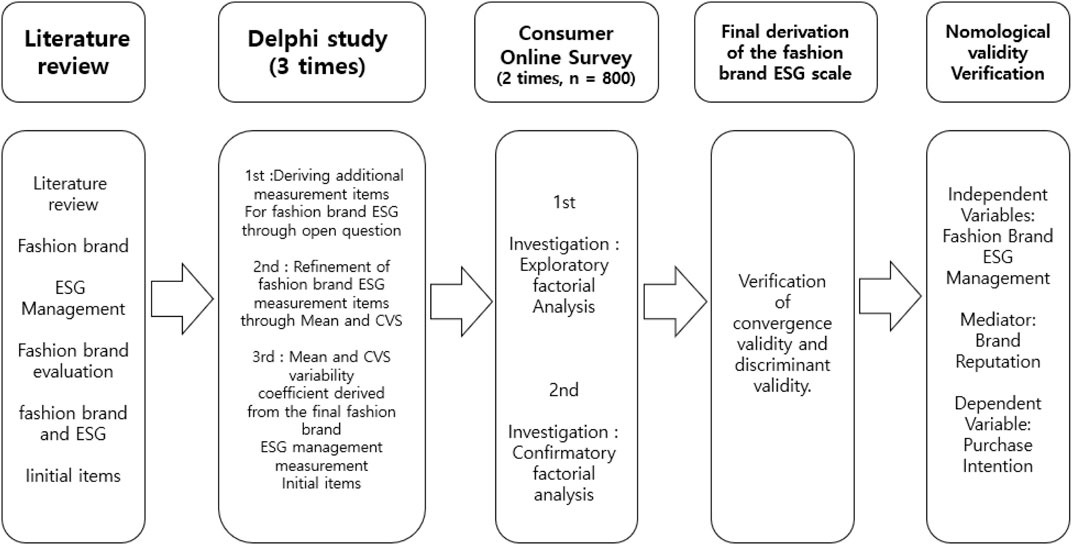

The purpose of this study was to derive and verify the accuracy of measurement items regarding the ESG practices of fashion brands using both qualitative and quantitative methods. To this end, a (qualitative) Delphi study was conducted with a group of 30 fashion industry experts: fashion CEOs, employees, related academic professors, and graduate students. The experts/survey subjects were limited to people who responded that they knew about ESG and that they purchased fashion items more than two to three times a month. The initial items were extracted from the existing literature, and two surveys were administered to 400 general consumers each for exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (EFA and CFA, respectively). Figure 2 depicts the research procedure followed in this study.

3.2.1 The Delphi technique

A Delphi study involves meetings conducted with panels of experts and/or close stakeholders with professional experience and knowledge; material is submitted for the group to review, such as the potential ESG scale items in this study. The opinions of the group members are collected, and survey rounds are repeated until a consensus is reached (Yu & Han, 2021).

The Delphi survey was conducted here with the exploratory purpose of identifying the components of ESG management for fashion brands. Qualitative research methods using in-depth interviews and focused group interviews were used to collect the initial preliminary questions through the Delphi surveys. The specific process we used is as follows.

First, items that can evaluate fashion brand ESG management were collected based on previous studies that were gathered in the literature review. Moreover, a group of fashion brand experts was formed to collect opinions using in-depth interviews and questionnaires. The expert panel for conducting the Delphi survey was composed of 30 people, including industry workers such as fashion brand marketing managers, magazine editors, CEOs, related academic professors, graduate students, and fashion brand consumers. An interview was conducted with this group of experts while focusing on the best practices as well as pros and cons of fashion brand ESG management, and based on the results of these interviews, we attempted to understand what subconcepts fashion brand ESG is composed of and what sub-concepts can be measured with.

Second, among the collected questions, items that were judged to have overlapping contents or low explanatory power were removed.

Third, the appropriateness of the initial questions derived for fashion brand consumers and expert groups was evaluated along a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very inadequate, 7 = very appropriate). Further, descriptive questions were added so that the participants could freely express their opinions on the fashion brand ESG.

Fourth, to verify the appropriateness of the items, a pre-survey was conducted three times while removing items whose average value, Content Validity Ration (CVR), and coefficient of variation did not meet the standard. CVR is the value obtained by subtracting half the total number of respondents (30/2 = 15) from the total number of cases (7-point Likert scale: more than 5 points) that responded as “valid”, then dividing it by half of the total number of respondents (Lawshe, 1975). It is a value indicating the degree of agreement of the expert panel on given concepts and factors. CVR has a difference in the minimum value that is used to obtain agreement depending on the number of expert panels. Since the number of panels in the expert group in this study is 30, CVR 0.33 was set as the minimum value standard 1 (Lawshe, 1975; Yu & Han, 2021).

3.2.2 Consumer survey

The resulting scale was then administered online to consumers aged from 20 to 59 years old who purchased fashion items at least twice a month and often searched for fashion brands. In total, data from a total of 800 surveys were collected, and these were analyzed quantitatively.

The first survey was administered to conduct an EFA of the Delphi group’s scale. In total, 400 respondents rated each survey item regarding the importance of each ESG practice for a fashion brand along a 7-point Likert scale. The items on the second survey were extracted from the EFA after removing items that did not meet their thresholds.

The second consumer survey was administered to conduct a CFA of the revised survey and measure the relationship between the fashion brand ESG practices scale, a brand’s reputation, and consumer purchase intention. The participants were 400 consumers aged from 20 to 59 years old who purchase fashion items more than twice a month and who regularly search for fashion brands. In this study, to determine whether the fashion brand ESG practices were significantly related with the brand’s reputation, respondents were asked to list at least three fashion brands that they believed were best practices for ESG management based on the items on the first consumer survey fashion brand ESG practices scale. Next, the reputation (Dowling, 2001; 2004a; 2004b) and purchase intention (Mackenzie & Lutz, 1989) of the names fashion brands were rated using a 7-point Likert scale.

Then, the SPSS process macro was used to analyze the influence of fashion brand ESG practices on purchase intention as well as the mediating effect of reputation based on these consumers’ survey responses. Hayes’s process macro (2013) is an analysis method that can reflect a phenomenon without assuming a normal distribution and that measures the significance of mediators. It can both accurately calculate indirect effects and analyzing the significance of the effects to be measured without requiring additional processing by verifying the direct and indirect effects in regression analysis (Hayes, 2013). Model 4 of the SPSS process macro was used to evaluate the direct, indirect, and total effects. To verify a mediating effect, it is necessary to check whether the size of the indirect effect—which verifies the significance of the mediating effect through bootstrapping—is statistically significant (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Specifically, if the upper limit CI of the indirect effect calculated at the 95% CI does not include 0, then the estimated size of the indirect effect is considered to be statistically significant (Hayes, 2013; Hayes & Preacher, 2014).

4. Results

4.1 The Delphi technique

Given RQ1 involving the most effective items for measuring a fashion brand’s ESG practices, the first step in this study was to derive a starting point for those practices. First, the literature review obtained 107 measurement items for the questionnaire that was developed for the Delphi round. The group removed items with similar meanings and duplicate items, then rated the remaining items for importance, which was again done on 7-point Likert scales. The experts ultimately arrived at 50 initial items, which included the addition of some new items.

Following the Delphi study round, Lawshe’s (1975) content validity ratio (CVR) was calculated for each item, and 10 items that did not meet the threshold of 0.33 were removed. CVR is calculated by subtracting half the total number of respondents from the number of cases (here scale items) rated as valid (i.e., which had a Likert scale score of 5 or more), then dividing that result by half the total number of respondents (Lawshe, 1975; Yu & Han, 2021). Next, SPSS (IBM SPSS Inc.) was used to calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) and Cronbach’s alpha for each of the remaining 40 items, and items that exceeded a CV of 0.3 were discarded. This ultimately left 30 survey items.

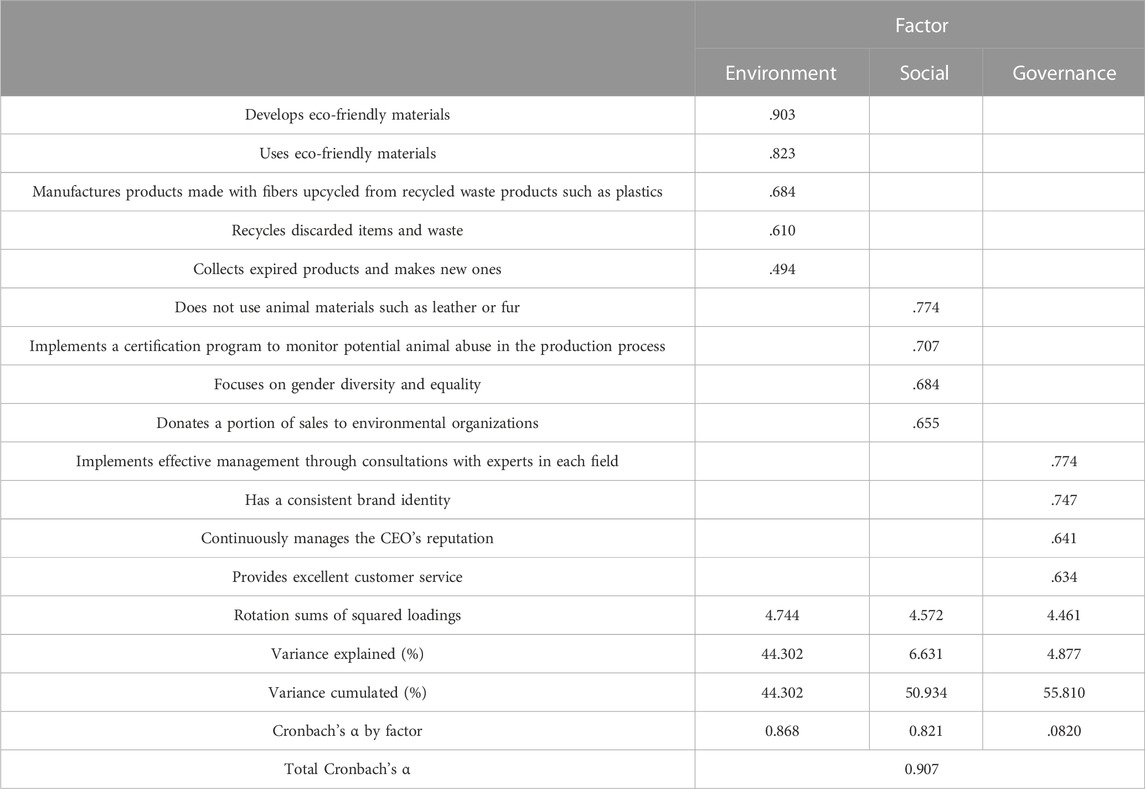

4.2 Exploratory factor analysis

For each of the 30 items extracted from the Delphi study and revisions, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to measure the reliability of the items for accurately measuring a fashion brand’s ESG activities; a Cronbach’s alpha of .7 is considered to be adequate. For the EFA to extract factors, promax rotation—which maintains the correlation without assuming that there is no correlation between factors—was used. Only items with a factor loading of at least 0.4 and an eigenvalue >1 or more were retained for the final scale.

The EFA left 13 items under the three factors of environment, social, and governance. The results of the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test, which indicates the appropriateness of the data standardization, was 0.921, while Bartlett’s sphericity was found to be significant (χ2 = 2487.056, p < 0.001). Cronbach’s α for all three factors exceeded the 0.7 threshold: environment, 0.868; social, 0.821; and governance, 0.820. The overall explanatory power for ESG was 55%, while Cronbach’s α for the full scale was 0.907, thus indicating the reliability of the scale. The 13 survey items that were extracted represent the response to RQ1 for this study: What items comprise an effective measurement scale for the ESG practices of a fashion brand? Table 1 lists the scale items that resulted from the EFA along with their individual factor loadings.

4.3 Confirmatory factor analysis

For the CFA, each factor extracted from the EFA was input as a latent variable, and each measurement item was input as an observation variable to construct a measurement model, after which the model fit could be measured. The CFA produced χ2 = 177.723 (df = 62, p = 0.000). In general, when the sample is sufficiently large (200 or more), a threshold of p < 0.05 is indicated, and the χ2 fitness test result rejects the null hypothesis that a model is appropriate. However, if there is a sufficient sample, then the p for χ2 is 0.000; in this case, if the null hypothesis is rejected, the model fit is not considered to be unacceptable. Instead, there is considered to be a significant difference and it is necessary to check whether the other fitness criteria are met (Yu & Han, 2021). For this study, adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were the absolute fit indices, while the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) and the comparative fit index (CFI) were the calculated incremental fit indices. Four models were tested for fit, and Table 2 presents the threshold for each index along with the indices for each tested model.

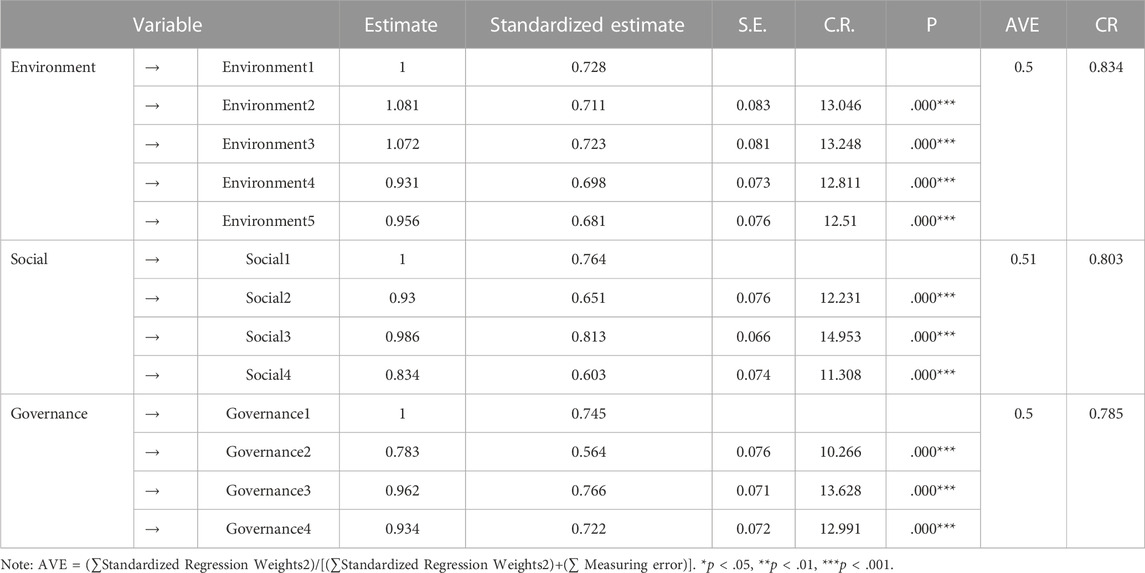

4.4 Convergent validity of fashion brand ESG practices scale

To answer RQ2, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated to verify the convergent validity of each scale factor; CR should be ≥0.7 and AVE should equal or exceed 0.5. As presented in Table 3, for the scale to measure a fashion brand’s ESG practices, CR ranged from 0.785 to 0.834 whereas AVE was either 0.5 or 0.51. Therefore, as each factor of the scale for measuring a fashion company’s ESG practices has been confirmed to have convergent validity, RQ2 is answered in the affirmative.

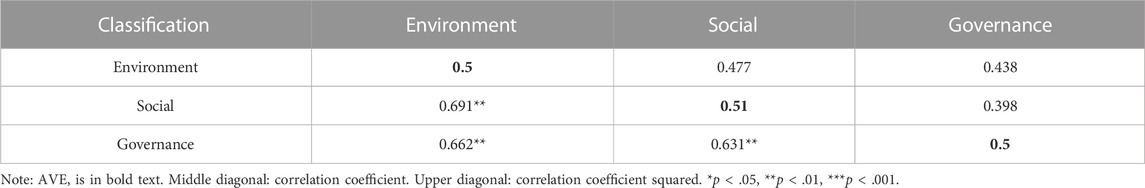

4.5 Fashion brand ESG practices scale discriminant validity

Finally, to answer RQ3 regarding the new scale’s discriminant validity, AVE, correlation coefficient, and correlation coefficient squared (R2) were calculated to distinguish the 13 ESG practices of fashion brands (Segarsm, 1997). Discriminant validity is confirmed if AVE for a variable—here, a fashion brand ESG practice—is greater than R2. Meanwhile, discriminant validity is confirmed with a rejection of the hypothesis that the correlation between latent variables (φ = 1.0) is the same; that is, when φ (correlation coefficient) ± 2 × standard error does not contain 1 at the 95% confidence interval (CI). As can be seen in Table 5, R2 = 0.398–0.477, which is lower than the minimum AVE of 0.5, and the hypothesis that the correlation between all latent variables was the same was rejected, thus indicating that the discriminant validity of the fashion brand ESG practices scale was secured (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), which therefore also answered RQ3 in the affirmative. Table 4 presents the findings regarding the discriminant validity.

Overall, the study results indicate that the scale developed in this work to measure a fashion brand’s ESG management according to its ESG practices has both convergent validity (RQ2) and discriminant validity (RQ3). In this study, the scale is tested for its ability to investigate the relationships between a fashion brand’s ESG practices, its reputation, and consumer purchase intention.

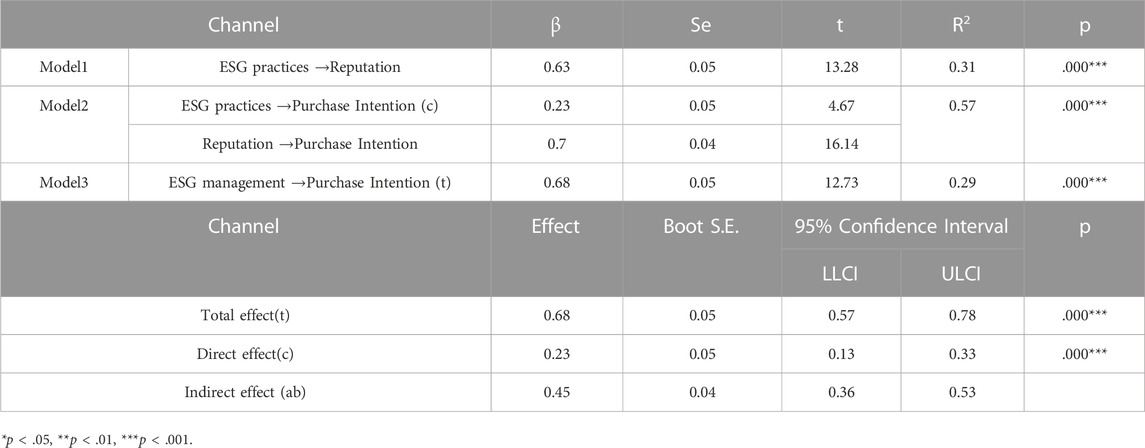

4.6 ESG practices, brand reputation, and purchase intention of fashion brands

If a mediated model analysis finds a significant mediator, then there is a mediating effect if the indirect effect—i.e., the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediation—is significant. As can be seen in Table 5, model 1 confirms a mediator in the effect of fashion brand ESG practices, which is an independent variable, on brand reputation. In a regression analysis, the effect of fashion brand ESG practices on brand reputation was found to be significant and positive (β = 0.63, p = 0.000).

TABLE 5. Mediating effects of fashion brand reputation on the effects of brand ESG practices on purchase intention.

In the second model, the effect on purchase intention was verified by introducing the independent variable of fashion brand ESG practices and the mediator of brand reputation. In the analysis, brand ESG practices (β = 0.23, p = 0.000) and reputation (β = 0.7, p = 0.000) were both found to have significant and positive effects on purchase intention. In the third model, fashion brand ESG practices and purchase intention were respectively input as the independent and dependent variables to examine the total effect of a brand’s ESG practices on purchase intention. The analysis confirmed that the independent variable had a significant positive effect (β = 0.68, p = 0.000) on the dependent variable.

Further, the magnitude of the indirect effect of ESG practices on purchase intention through reputation was 0.45, with a lower limit of 0.36 and an upper limit of 0.53. As 0 was not within the 95% CI, the mediating effect of fashion brand reputation was considered to be statistically significant. Thus, the results indicate that the effect of fashion brand ESG practices on purchase intention was partially mediated by brand reputation, and that H1 and H2 were both supported. Tables 6 through 8 present the details of the mediating relationships for each of the dimensions of ESG practices, environment, social, and governance.

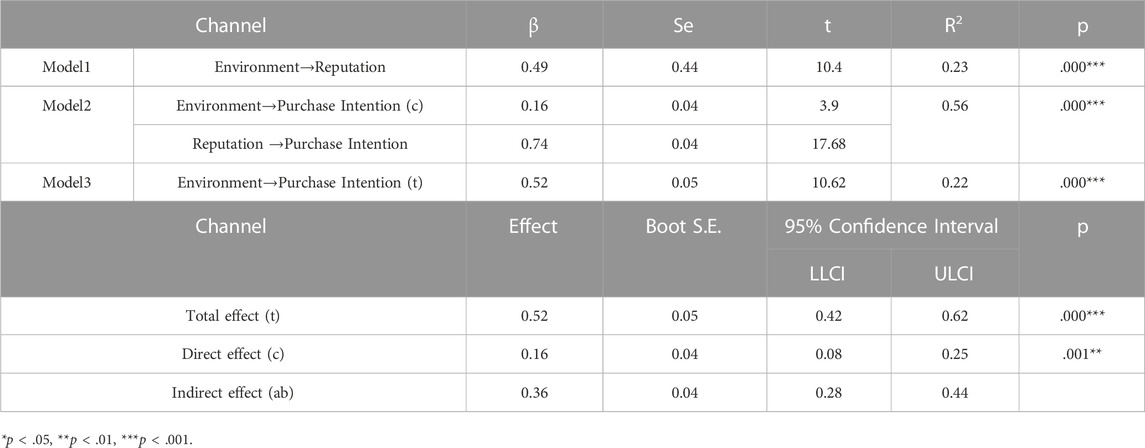

TABLE 6. Mediation effects of fashion brand reputation on the effects of brand environmental practices on purchase intention.

4.6.1 Fashion brand environmental practices, brand reputation, and consumer purchase intention

Table 6 presents the effects of the independent variable of a fashion brand’s environmental practices on that brand’s reputation as a mediator in the first model. The regression analysis revealed that a brand’s environmental practices had a significant positive effect on its reputation (β = 0.49, p = 0.000). In the second model, the effect on purchase intention was verified by introducing the brand’s environmental practices as an independent variable and the reputation as a mediator, and environmental practices (β = 0.16, p = 0.000) and reputation (β = 0.74, p = 0.000) were both found to have significant positive effects on purchase intention. In the third model, brand environmental practices and purchase intention were respectively input as the independent and dependent variables to examine the total effect of environmental practices on purchase intention. The results of this analysis showed that the independent variable had a significant and positive effect (β = 0.52, p = 0.000) on the dependent variable. Moreover, the magnitude of the indirect effect of the environmental practices on purchase intention through reputation was 0.36, with a lower limit of 0.28 and an upper limit of 0.44. Thus, the influence of a fashion brand’s environmental practices on purchase intention was partially mediated by brand reputation; H1-1 and H2-1 were therefore supported.

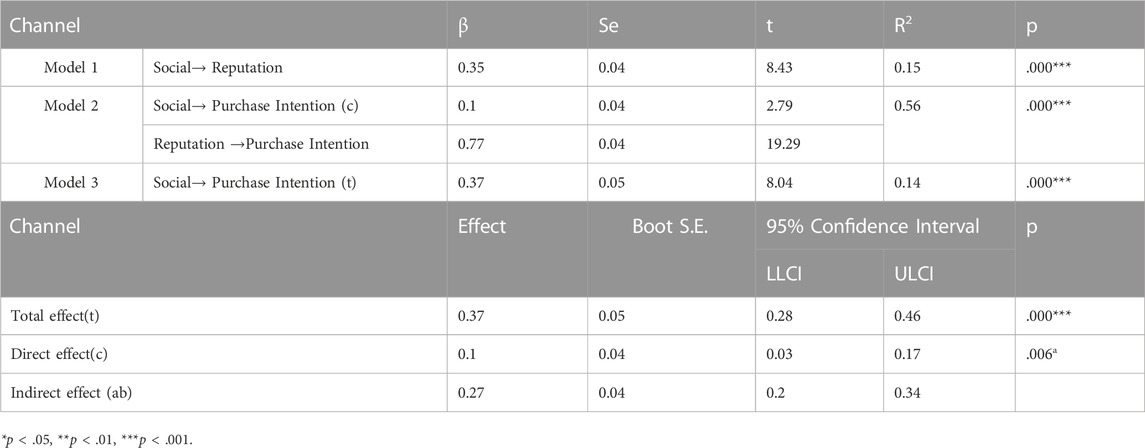

4.6.2 Fashion brand social practices, brand reputation, and consumer purchase intention

Table 7 lists the effects of the independent variable of the social practices of a fashion brand on the brand’s reputation as a mediator in the first model. The results of the regression analysis showed that a brand’s social practices had a significant positive effect on its reputation (β = 0.35, p = 0.000). In the second model, the effect on customer purchase intention was verified by introducing the brand’s social practices as an independent variable and the brand reputation as a mediator. The analysis revealed that both brand social practices (β = 0.1, p = 0.000) and brand reputation (β = 0.77, p = 0.000) had significant positive effects on purchase intention. In the third model, the brand social practices and consumer purchase intention were respectively input as the independent variable and the dependent variable to examine the total influence of social practices on purchase intention. In the analysis, the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable was found to be significant and positive (β = 0.37, p = 0.000). Further, the magnitude of the indirect effect of the social practices on purchase intention through brand reputation was 0.27, with a lower limit of 0.2 and an upper limit of 0.34. Thus, the influence of a fashion brand’s social practices on consumer purchase intention was partially mediated by brand reputation, and H1-2 and H2-2 were both supported.

TABLE 7. Mediation effects of fashion brand reputation on the effects of brand social practices on purchase intention.

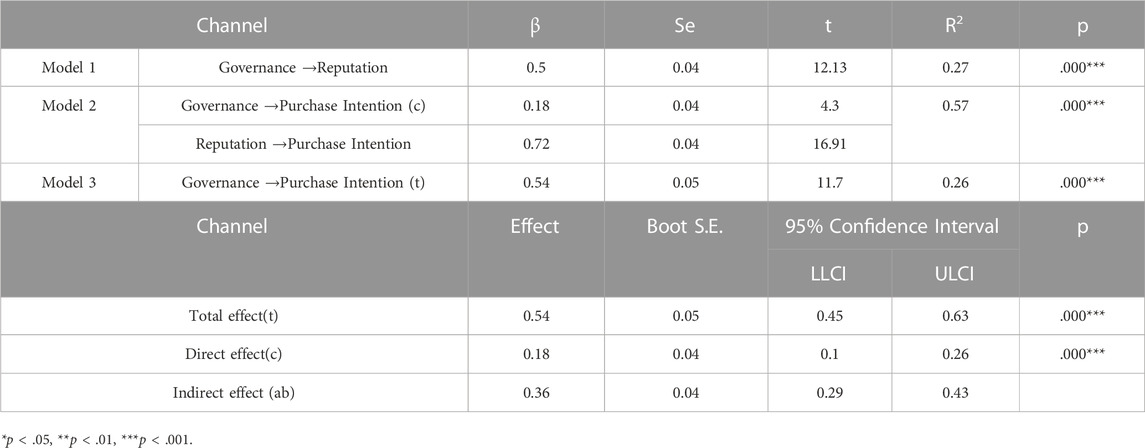

4.6.3 Fashion brand governance practices, brand reputation, and consumer purchase intention

The results of the first model in Table 8 show the effect of a fashion brand’s governance practices as the independent variable on the brand’s reputation as a mediator. The regression analysis results showed that governance practices had a significant positive effect on brand reputation (β = 0.5, p = 0.000). In the second model, the effect on purchase intention was verified by introducing governance practices as an independent variable and brand reputation as a mediator. This analysis found that both governance practices (β = 0.18, p = 0.000) and brand reputation (β = 0.72, p = 0.000) had significant and positive effects on purchase intention. In the third model, governance practices and customer purchase intention were respectively input as the independent variable and the dependent variable to examine the total effect of a brand’s governance practices on consumer purchase intention. This analysis indicated that the independent variable had a significant and positive effect (β = 0.54, p = 0.000) on the dependent variable. Further, the magnitude of the indirect effect of the governance practices on purchase intention through brand reputation was 0.36, with a lower limit of 0.29 and an upper limit of 0.43. Thus, the influence of a fashion brand’s governance practices on consumer purchase intention was partially mediated by the brand’s reputation, and H1-3 and H2-3 were supported.

TABLE 8. Mediation effects of fashion brand reputation on the effects of brand environmental practices on purchase intention.

5 Discussion

Although ESG practices have represented a relevant research topic since the early 2000s, they have taken on increased importance following the paradigm shifts demanded by the COVID-19 pandemic. A wide variety of stakeholders—consumers, shareholders, investors, employees, community residents, etc.,—now consider social responsibility, eco-friendly policies, and stable, transparent governance to be important criteria for judging a company’s authenticity and reliability, and ultimately, its value. These stakeholders have also been monitoring companies with an increasingly critical eye (Blowfeld & Murray, 2019), and companies that do not actively engage in ESG and CSR practices can face criticism from consumers and even lose business.

For example, the global energy company Exxon Mobil generates tremendous amounts of carbon dioxide in refining oil, and its shareholders have called for various carbon reduction efforts in response. However, Exxon Mobil rejected the demands of its shareholders and continued its business practices, which led to a customer boycott and a decline in corporate value. By contrast, Nestlé, which provides long-term support to coffee bean growers and local communities in South America, and Ottogi, which maintains a 99% regular employment rate and performs a range of social contribution activities, have achieved results such as increased sales and improved corporate reputations by not ignoring shareholder demands. ESG management and practices have become globally relevant, and they now even serve as standards for investors.

As such, it has been argued that sustainable development can be achieved when companies consider transparent management such as eco-friendliness, social responsibility management, and governance improvement. Consistent with this, ESG management has become a global corporate management method and investment standard for investors.

The importance of ESG management is continually growing for fashion brands that want to secure competitiveness and protect their stakeholders. The fashion industry has a close relationship with the Environmental and Social aspects, from production to the disposal of products. As awareness of climate change grows around the world, the fashion industry is increasingly being pointed to as the main culprit of environmental pollution, and fashion brands have recently been striving for ESG management by adopting eco-friendly methods or launching products targeting the socially disadvantaged.

Until recently, developments in the textile and clothing industries have focused on technology and cost (Niinimäki & Hassi, 2011). However, fashion brands have begun to recognize the importance of ESG practices in securing competitiveness and maintaining positive relationships with customers as well as protecting stakeholders. The textile/apparel industry is very important to the economy in terms of trade, employment, investment, and revenue worldwide. However, there is a significant loss due to overproduction and a “throw away” culture (Filho et al., 2019). Since the 2000s, the fashion industry has received criticism and warnings from environmental and consumer groups regarding the extensive negative environmental impacts of its work, and brands have shown gradual increases in their ESG practices. ESG management and practices are considered to be long-term strategies that affect corporate sustainability, and the fashion industry is expected to make many such ESG changes in the future.

However, to this point, ESG management scales have been too broad to apply to specific fields, and due to the different standards presented, there have been few scientific and empirically verified scales. In particular, there have been no scholarly investigations of ESG practices in the context of the fashion industry. The primary outcome of this research was a scale that was developed via the Delphi method and made up of individual items that mark a fashion brand as one that follows ESG practices. The produced scale encompasses 13 ESG practices that fashion brands should follow under the three domains of ESG, which constitute the three factors from the exploratory analysis: environment, society, and governance. The items for each factor of ESG practices of fashion brands derived from this research are as follows.

First, Environment was represented by five measurement items: “Develops eco-friendly materials,” “Uses eco-friendly materials,” “Manufactures products made with fibers upcycled from recycled waste products such as plastics’” “Recycles discarded items and waste,” and “Collects expired products and makes new ones,” These items involve the development and use of eco-friendly materials and waste management. This is interpreted as the result of fashion brand consumers demanding not only products that use eco-friendly materials, but also high-level eco-friendly activities such as fiber utilization using waste (recycle), waste recycling (upcycling), and product recycling (reuse).

Second, Social was represented by four measurement items: “Does not use animal materials such as leather or fur,” “Implements a certification program to monitor potential animal abuse in the production process,” “Focuses on gender diversity and equality,” and “Donates a portion of sales to environmental organizations,” These items represent the contribution of fashion brands to social issues related to fashion. Fashion brand consumers do not want animal abuse associated with the use of animal materials such as leather and fur utilized in the textile industry, which has a close relationship with fashion brands. Moreover, considering the impact of the fashion industry on environmental destruction, consumers want to donate a portion of their sales to environmental organizations. Interestingly, items related to gender diversity and gender equality were drawn, which is interpreted to be part of the recent trend of consumers’ perception that they should contribute to improving gender awareness while pursuing “genderless,” a way of dressing regardless of gender in the fashion industry.

Third, Governance is represented by four measurement items: ‘Implements effective management through experts in each field’, ‘Has a consistent brand identity’, ‘Continuously manages the CEO’s reputation’, and ‘Provides excellent customer service’. These items represent reputation management through the consistent and effective management of fashion brands. Fashion brand consumers want fashion brands to maintain their brand identity through professional and effective management based on consultations with experts in each field. Further, consumers want high-quality customer service that is directly related to consumer needs. This is interpreted to mean that consumers want to continue to manage the reputation of CEOs and brands through these governance activities.

Further, the ESG practices from this research scale were confirmed to have significant positive direct effects on a fashion brand’s reputation along with positive effects on customer purchase intention through brand reputation. These results have the following practical and theoretical implications. The fashion brand ESG practices developed in this research secured nomological validity through research results that significantly affect purchase intention and reputation related to fashion brand ESG management. Therefore, the fashion brand ESG practices developed in this research can be used to verify the effects of various variables through the research model developed in subsequent studies. From a practical point of view, these results show that fashion brands’ ESG management practice considering the ESG practices items developed in this research leads to enhanced brand reputation, which can lead to increased sales.

ESG as a management practice enhances a company’s reputation, which increases consumers’ trust in the company and satisfaction with its practices; this in turn leads to repurchase behavior (Yu & Han, 2021). Reputation is a universal value judgment about a company (Bromley, 2000), and it develops positively over time as a result of a company’s continuous, long-term efforts (Gray & Balmer, 1998); short-term ESG practices will only have slight impacts on brand reputation. Positive reputation impacts will only be derived from long-term ESG practices in the fashion industry, which should lead to increased sales.

The fashion brand ESG practices scale developed in the present work are expected to provide a standard by which consumers can choose reliable, sustainable brands, and a standard for individual brands to measure whether they are conforming to ESG tenets. Brands that follow the ESG practices in the scale will improve their reputations with consumers, and positive brand experiences are expected to lead to increased profits.

6 Conclusion and limitations

This research was conducted to derive and empirically verify items that can be used to measure the ESG management of fashion brands, which are primary actors in environmental and social problems. This research provides the following theoretical implications.

First, expertise was enhanced by developing measurement items on a scale for a group of experts composed of various stakeholders. Moreover, through an expanded research design that combines quantitative and qualitative research, this study expanded the research topics and scope of the analysis methodology used for fashion brands, for which there is still a lack of quantitative and qualitative research cases related to ESG management. It gathered a group of experts targeting various stakeholders of fashion brands, including fashion brand CEOs, fashion magazine CEOs, related academic professors and graduate students, and consumers who are highly involved in fashion brands. Through a multidimensional and scientific verification process, a tool was developed that could be used to measure the reputation of a fashion brand, and through this, high levels of statistical reliability and validity were secured.

Second, this research was specifically conducted to examine fashion brands that have a close relationship with ESG management. Considering that global fashion companies are predicting ESG management for sustainable development, they have developed ESG management evaluation items that the fashion industry can refer to and apply. The fashion brand ESG management scale developed in this research is expected to provide guidelines for brand reputation management that can help fashion brands in the future.

As such, this research derived items to measure fashion brand ESG management through various approaches. Moreover, the reliability and validity of these items were secured through multidimensional verification, and significant effects on reputation and purchase intention were empirically verified to provide various theoretical and practical imitations. However, this research has the following limitations.

First, the Online Consumer Survey conducted a study targeting only fashion brand consumers. Although the Delphi study collected opinions from various fields, the Online Consumer Survey did not consider various stakeholders. Due to the nature of online surveys, it was difficult to control the conditions of the survey participants. In the future, if an environment were to control the survey participants is secured and research is conducted on various stakeholders related to fashion brands, this would help extract various factors and items and therefore obtain generalized results.

Second, it is necessary for future studies to more deeply explore the relationship between various variables in addition to reputation and purchase intention in the future. This will help clarify the role of ESG management in terms of marketing communication and establish a foundation upon which a sustainable brand can be built. In addition, based on the fashion brand ESG management scale of this research, it is expected that an empirical study can be conducted to evaluate and measure the ESG management of a fashion brand while targeting a specific fashion brand.

Finally, this research was conducted with participants from Eastern cultures. Since the social perception of ESG and evaluation items may be different, meaningful results can be derived if a comparative analysis is conducted by securing responses from both Eastern and Western participants in the future. In addition, it is expected that ESG management practices and marketing communication strategies can be derived by deducing ESG practices that should be applied separately to either the East or the West as well as those that can be simultaneously applied to both the East and the West. ajunews, 2021, Hansbiz, 2021, INDUSTRY EUROPE, 2022, Sukma and Leelasantitham, 2022b.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HY: conceptualization, methodology, analysis, writing- original draft preparation. MA: data collect, methodology, writing. EH: conceptualization, methodology, writing-review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

ajunews, (2021). Aju business daily. https://www.ajunews.com/view/20210911174009630 (Accessed August 06, 2022).

Alareeni, B. A., and Hamdan, A. (2020). ESG impact on performance of US S&P 500-listed firms. Corp. Gov. 20 (7), 1409–1428. doi:10.1108/cg-06-2020-0258

Amel-Zadeh, A., and Serafeim, G. (2018). Why and how investors use ESG information: Evidence from a global survey. Financial Analysts J. 74 (3), 87–103. doi:10.2469/faj.v74.n3.2

Aytekin, A., Okoth, B. O., Korucuk, S., Karamaşa, Ç., and Tirkolaee, E. B. (2023). A neutrosophic approach to evaluate the factors affecting performance and theory of sustainable supply chain management: Application to textile industry. Manag. Decis. 61 (2), 506–529. doi:10.1108/md-05-2022-0588

Ben-Amar, W., Chang, M., and McIlkenny, P. (2017). Board gender diversity and corporate response to sustainability initiatives: Evidence from the carbon disclosure project. J. Bus. Ethics 7 (2), 369–383. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2759-1

Bloomberg, (2022). The global glut of clothing is an environmental crisis. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2022-fashion-industry-environmental-impact/ (Accessed August 06, 2022).

Blowfeld, M., and Murray, A. (2019). Corporate social responsibility. 5th. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

Broadstock, , Chan, K., Cheng, L. T., and Wang, X. (2021). The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Finance Res. Lett. 38, 101716–101811. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2020.101716

Brogi, M., and Lagasio, V. (2019). Environmental, social, and governance and company profitability: Are financial intermediaries different? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 26 (3), 576–587. doi:10.1002/csr.1704

Bromley, D. B. (2000). Psychological aspects of corporate identity, image, and reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 3 (3), 240–252. doi:10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540117

Brown, T. J., and Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 61 (1), 68–84. doi:10.2307/1252190

Cachon, G. P., and Swinney, R. (2011). The value of fast fashion: Quick response, enhanced design, and strategic consumer behavior. Manag. Sci. 57 (4), 778–795. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1100.1303

Cataldi, C., Dickson, M., and Grover, C. (2010). Slow fashion: Tailoring a strategic approach towards sustainability”. Karlskrona, Sweden: Blekinge Institute of Technology.

Clementino, E., and Perkins, R. (2021). How do companies respond to environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings? Evidence from Italy. J. Bus. Ethics 171, 379–397. doi:10.1007/s10551-020-04441-4

Davies, G., Chun, R., Da Silva, R. V., and Roper, S. (2003). Corporate reputation and competitiveness. London, UK: Routledge.

Di-Benedetto, C. A. (2017). Corporate social responsibility as an emerging business model in fashion marketing. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 8 (4), 251–265. doi:10.1080/20932685.2017.1329023

Dowling, G. R. (2004b). Corporate reputations: Should you compete on yours? Calif. Manag. Rev. 46 (3), 19–36. doi:10.2307/41166219

Dowling, G. R. (2004a). Journalists' evaluation of corporate reputations. Corp. Reput. Rev. 7 (2), 196–205. doi:10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540220

Dowling, G. R., and Roberts, P. W. (2002). Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strategic Manag. J. 23, 1077–1093. doi:10.1002/smj.274

European Parliament, (2022). The impact of textile production and waste on the environment (infographic). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20201208STO93327/the-impact-of-textile-production-and-waste-on-the-environment-infographic (Accessed August 06, 2022).

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Los Angeles, CA, USA: Sage Publications Sage CA.

Friede, G., Busch, T., and Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 5 (4), 210–233. doi:10.1080/20430795.2015.1118917

Galbreath, J. (2013). ESG in focus: The Australian evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 118 (3), 529–541. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1607-9

Giese, G., Lee, L. E., Melas, D., Nagy, Z., and Nishikawa, L. (2019). Foundations of ESG investing: How ESG affects equity valuation, risk, and performance. J. Portfolio Manag. 45 (5), 69–83. doi:10.3905/jpm.2019.45.5.069

Gray, E. R., and Balmer, J. M. T. (1998). Managing corporate image and corporate reputation. Long. Range Plan. 31 (5), 695–702. doi:10.1016/s0024-6301(98)00074-0

Gupta, A. (2019). Sustainability policies for the fashion industry: A comparative study of asian and European brands. Indian J. Public Adm. 65 (3), 733–748. doi:10.1177/0019556119844581

Gwilt, A. (2020). A practical guide to sustainable fashion. 2nd. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Han, E. K., and Yu, J. H. (2004). A study on corporate reputation factors to influence the purchasing intention of consumers: Based on Korean and Japanese dairy products companies. Advert. Res. 65, 127–146.

Hansbiz, (2021). sporbiz. http://www.sporbiz.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=600895 (Accessed August 06, 2022).

Hayes, A. F. (2013). “Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis,” in Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach 1, 20.

Hayes, A. F., and Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 67 (3), 451–470. doi:10.1111/bmsp.12028

Holden, E., Linnerud, K., and Banister, D. (2017). The imperatives of sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 25 (3), 213–226. doi:10.1002/sd.1647

Industry Europe, (2022). The EU wants to end fast fashion by 2030. https://industryeurope.com/sectors/consumer-goods/the-eu-wants-to-end-fast-fashion-by-2030/ (Accessed August 06, 2022).

Ji, Y. B., and Seo, Y. W. (2021). The effect of domestic corporations' ESG activities on purchase intentions through psychological distance: Analysis of differences by product involvement level. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 21 (12), 217–237.

Jia, F., Yin, S., Chen, L., and Chen, X. (2020). The circular economy in the textile and apparel industry: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 259, 120728. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120728

Jiménez-Zarco, A. I., Moreno-Gavara, C., and Njomkap, J. C. S. (2019). “Sustainability in global value-chain management: The source of competitive advantage in the fashion sector,” in Sustainable fashion. Palgrave studies of entrepreneurship in Africa. Editors G. C. Moreno, and A. Jiménez-Zarco (London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan).

Jukemura, P. K. (2019). Why ESG investing seems to be an attractive approach to investment in Brazil (Sao Paolo, Brazil: Bachelor thesis).

Kwon, S. H. (2022). A study on circular textiles in luxury fashion. J. Commun. Des. 78, 84–101. I410-ECN-0102-2023-600-000554290.

Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 28 (4), 563–575. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x

Leal Filho, W., Ellams, D., Han, S., Tyler, D., Boiten, V. J., Paço, A., et al. (2019). A review of the socio-economic advantages of textile recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 218, 10–20. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.210

MacKenzie, S. B., and Lutz, R. J. (1989). An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. J. Mark. 53 (2), 48–65. doi:10.1177/002224298905300204

Mosler, H. J., Tamas, A., Tobias, R., Rodriguez, C. T., and Miranda, G. O. (2008). Deriving interventions on the basis of factors influencing behavioral intentions for waste recycling, composting, and reuse in Cuba. Environ. Behav. 40 (4), 522–544. doi:10.1177/0013916507300114

Munoz-Torres, M. J., Fernandez-Izquierdo, M. A., Rivera-Lirio, J. M., Ferrero, I., Escrig-Olmedo, E., Gisbert-Navarro, J. V., et al. (2018). An assessment tool to integrate sustainability principles into the global supply chain. Sustainability 10 (2), 535. doi:10.3390/su10020535

Niinimäki, K., and Hassi, L. (2011). Emerging design strategies in sustainable production and consumption of textiles and clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 19 (16), 1876–1883. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.04.020

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. methods 40 (3), 879–891. doi:10.3758/brm.40.3.879

Provasnek, A. K., Schmid, E., Geissler, B., and Steiner, G. (2017). Sustainable corporate entrepreneurship: Performance and strategies toward innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 26 (4), 521–535. doi:10.1002/bse.1934

Sam-Jeong, K. P. M. G. (2020). The age of ESG managenment and strategic paradigm. Seoul, South Korea: Seoul Sam-Jeong KPMG.

Sarkis, J., Zhu, Q., and Lai, K. H. (2011). An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 130 (1), 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.11.010

Seuring, S., and Müller, M. (2008). From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 16 (15), 1699–1710. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.04.020

Sukma, N., and Leelasantitham, A. (2022a). A community sustainability ecosystem modeling for water supply business in Thailand. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1209. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.940955

Sukma, N., and Leelasantitham, A. (2022b). From conceptual model to conceptual framework: A sustainable business framework for community water supply businesses. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 2213. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.1013153

Textile Exchange, (2021). Preferred fiber and materials market report 2021. https://textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Textile-.

Van Duuren, E., Plantinga, A., and Scholtens, B. (2016). ESG integration and the investment management process: Fundamental investing reinvented. J. Bus. Ethics 138 (3), 525–533. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2610-8

World Resources Institute, (2017). The apparel industry’s environmental impact in 6 graphics. https://www.wri.org/insights/apparel-industrys-environmental-impact-6-graphics (Accessed August 06, 2022).

Keywords: fashion brand, ESG, environment, social, governance, reputation

Citation: Yu H, Ahn M and Han E (2023) Key driver of textile and apparel industry management: fashion brand ESG and brand reputation. Front. Environ. Sci. 11:1140004. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1140004

Received: 08 January 2023; Accepted: 16 June 2023;

Published: 23 June 2023.

Edited by:

Federica Cucchiella, University of L’Aquila, ItalyReviewed by:

Narongsak Sukma, Mahidol University, ThailandErfan Babaee Tirkolaee, University of Istinye, Türkiye

Copyright © 2023 Yu, Ahn and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eunkyoung Han, YmlyZDI0QHNra3UuZWR1

Heeseung Yu

Heeseung Yu Minhwan Ahn

Minhwan Ahn Eunkyoung Han

Eunkyoung Han