95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 07 February 2023

Sec. Land Use Dynamics

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1119936

This article is part of the Research Topic Land Use and Food Security from Theory to Empirical Exploration View all 5 articles

In the 70 years since it has been founded, China’s cultivated land protection work has made remarkable achievements: less than 10% of the world’s cultivated land has fed 22% of the world’s population and 900 million peasants have the foundation on which to survive and develop. However, under the strictest protection system such as “Grow Teeth” (GT), there is still a deviation of “norm-value” and “demand-efficacy” in the Administrative Protection of Cultivated Land (APCL) at this stage. This paper uses normative analysis method, similar case research method as well as value analysis method to find that the legitimacy of the current APCL system is insufficient: on the one hand, under the perspective of functionalist “needs and efficacy”, the existing Cultivated Land Protection Law (Draft) (CLPL) and other normative documents cannot meet the needs of APCL penalties, relief, public welfare, etc.; On the other hand, from the perspective of normative “value legitimacy”, APCL legitimacy value foundation is lacking due to the limitations of overall value fragmentation, insufficient compatibility value and fragile defensive value. Therefore, the value base of APCL should be dismantled under the guidance of “function for use” to disassemble the functions of punishment, relief and public welfare, so as to specifically realize the construction of CLPL subjects, the inheritance of regulations, the transformation of responsibility subdivision, and the Land Administration Law and other regulatory continuations, to carry out protective measures such as clarifying the scope of punishment and giving compulsory force after coordination to cultivated land protection inspection recommendations, so as to give full play to the efficacy of APCL.

Cultivated land is the basis for human survival and development and the most basic agricultural production resources and agricultural productivity factors (Taraborin, 2021). The foundation of ensuring food security lies in the protection of cultivated land (Petersen-Rockney et al., 2021) and improving the quality of cultivated land is an important measure to consolidate and improve food production capacity and ensure global food security and ecological security (Su et al., 2022). China has always attached great importance to the protection and utilization of cultivated land, from the initial exploration at the beginning of the founding of the People’s Republic of China to the gradual expansion of cultivated land quality construction after the reform and opening up (Liu et al., 2017), and then to the expansion and extension of cultivated land ecosystem maintenance since 2012, forming a “trinity” that takes into account quantity, quality and ecology‘s comprehensive cultivated land protection and utilization system (Zhu et al., 2022). In addition, the implementation of the most stringent cultivated land protection system such as “Grow Teeth” (GT) provides valuable experience for the conservation and utilization of cultivated land worldwide. Marked by the implementation of the Land Administration Law (LAL) in 1987, China has begun the process of institutionalization, rule of law and institutionalization of Administrative Protection of Cultivated Land (APCL). This was followed by amendments to the Land Administration Law (LAL) in 1999 and in 1993,1999 and 2008, the State Council of China successively issued the (The Central People’s Government of the PRC, 1985) and the (The Central People’s Government of the PRC, 1997) and the (The Central People’s Government of the PRC, 2006). In terms of the protection of the quantity of cultivated land, China has gradually adjusted and improved the initial “protection of the quantity of cultivated land” to “maintain the dynamic balance of the total amount of cultivated land and the equal quantity and quality of cultivated land occupation and compensation ", and improved the “protection of basic cultivated land” to “permanent basic cultivated land protection”, clearly proposed to keep it 1800 million mu of cultivated land red line; In terms of cultivated land quality construction, it has put forward “strengthening the transformation of medium and low-yield cultivated land to ensure that the overall quality of cultivated land is improved”, as well as the detailed requirements for “improving the level of cultivated land protection and comprehensively strengthening the construction and management of cultivated land quality”; In the aspect of cultivated land management, it has also put forward the system of “the first responsible person for the governor of the amount as well as the area of cultivated land”. With the promulgation of the Cultivated Land Protection Law (Draft) (CLPL) in September 2022, the process of legalization of China’s APCL has reached a new level. As the basic law in the field of cultivated land protection, CLPL has not only risen from an administrative regulation of the Basic Farmland Protection Regulations (BFPR) to a law passed by the Chinese National Assembly, but also made great progress over the BFPR in terms of specific administrative protection measures. In public law, the normativism is a traditional thought rooted in the belief of ideal of decentralization and the necessity of making the government obey the norm, emphasizing the judicial and control functions of the law, and therefore paying attention to the rule orientation and conceptual attributes of the law (Goranov, 2019), which basically reflects the ideal of autonomy (primary production) of legal rules (Mendes, 2022). An important feature of China’s current APCL is to protect cultivated land with the strictest system and the strictest rule of law. It requires strict implementation of the “Grow Teeth” hard measures to protect cultivated land, comprehensively grasp and maintain the red line of 1.8 billion mu of cultivated land from a strategic and overall perspective, in order to improve the quality of cultivated land, and comprehensively consolidate the material basis for food security, which reflect the requirements of “rule by rule” under normativism. In the latest CLPL, relevant provisions regulate the protection subjects, protection standards, protection objectives, legal responsibilities and other issues of cultivated land protection, define the rights (powers) and obligations of the subjects of legal relations in the field of cultivated land protection, and achieve effective accountability through detailed provisions such as “assessment of responsibility objectives”, “supervision of cultivated land protection”, and judicial and administrative discretion, so as to form a legal system of cultivated land protection dominated by the legalization of administrative protection. Under the terms of normativism, APCL legalization is an effective way to define the relevant laws and regulations of administrative protection and their normative value basis (Zorzetto, 2021), which mainly requires the integrity, compatibility and defensive of APCL system (Andreescu and Puran, 2022). Through the overall balance and internal integrity of the system, it provides a benchmark for the overall integration and connection of the normative structure in APCL (Scholtes, 2019). By putting forward higher requirements for the compatibility of the normativism, the multiple coverage of the protected objects by APCL is realized; At the same time, the defensive value of APCL system is used to cope with the administrative task and expansion and the change of administrative role in the field of cultivated land protection (Tschorne, 2020). Functionalism is a regulatory model corresponding to the normativism, which emphasizes the value of pragmatism and can provide more flexible standards and balance strategies for public administrators (Morgenthau, 2017). Specifically, functionalism first attaches importance to the functions of different organizations in the field of APCL. Functionalism also believes that people should not only prevent the abuse of government power, but also promote the functions and values of power, especially administrative power, in promoting public services (Zumbansen, 2008), which means that functionalism recognizes the functional limitations, therefore the participation of other subjects are required to make up for the limitation of risk regulation function of administrative organs; Secondly, it focuses on the discretion of the administrative organs (Klabbers, 2014), promotes the function of discretion to complete administrative tasks actively and efficiently, and gives play to the initiative of administrative discretion in the process of systematically managing their own reproduction (Whytock, 2009). At present, China is pushing for the establishment of a “all-factor” protection system for cultivated land, which requires the formation of a “six in one” integration mechanism of cultivated land use control, remediation and quality improvement, capacity improvement, spatial planning, circulation and value-added, and rights and interests protection. It means that cultivated land protection decisions are policy oriented and benefit measuring, which requires taking into account the “functional governance” thinking mode while meeting the “rule of law". The “functional” relationship between relevant regulations and “specifications” in APCL is shown in Table 1.

It is generally believed that administrative protection can be divided into private benefit-oriented administrative protection and public welfare-oriented administrative protection according to the different leading goals (Eckes and Mendes, 2011; de Casimiro and de Sousa, 2020), in which the dominant objective of public welfare-oriented administrative protection is to safeguard and promote relevant national and social interests (Handrlica, 2018; Metzger, 2010) based on the idea of a political philosophy of a positive state view (Pojanowski, 2019). APCL is classified as public welfare-oriented according to this classification. At the same time, public welfare-orientated and private interest-orientated are not diametrically opposed (Bastos, 2021), APCL also attaches importance to the maintenance of private interests, but focuses more on safeguarding and restoring public interests (Gersen, 2020). Driven by public welfare-oriented goals, APCL encompasses all stages of the cultivated land conservation life cycle, including all types of administrative protection methods such as administrative management, administrative relief, administrative agreements, and administrative public interest litigation (Rosenbloom and Piotrowski, 2005; Bell, 2021). On this basis, scholars have carried out the normative (Li et al., 2016) and empirical (Xiao et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2017) studies on the problems of logic of policy formulation (Zheng et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022) and implementation strength (Han et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022). There is no doubt that improving the implementation of policies can work to a certain extent, but focusing on the manifestations of norms is not the only good antidote to the problems of system operation (García Berger, 2015), and re-examining the logic of policy formulation is not the only option to properly solve policy failures. The key to evaluate whether the APCL system is mature and superior. Depends on whether the system is legitimate, and only a political order with legitimacy can be called fair and just (Merlino, 2021; Didikin, 2018). In any regulatory system, the legitimacy of the regulator and his activities fundamentally determines the successful operation of the regulatory system (Cooper, 1993; George, 2008). Scholars have not grasped the value basis of the norms related to the APCL system, and the discussion of the system itself has failed to pay attention to the legitimacy of the system. Many scholars point out that legitimacy is not only equivalent to legality or legality, but more related to need satisfaction and value judgment in the formation and adjustment of institutions (Marszal, 2020). Based on this, the academic community generally believes that from the perspective of normativism, norms have a value basis, and only the value recognized and solidified by norms is the connotation that norms “should” point to (Segado, 2013); From a functionalist perspective, the legitimacy of an institution derives from the ends it pursues, which in turn derive from social needs (Weinrib, 2021; Chiti, 2016). Normativism answers the question of what a system should look like, and functionalism answers what functions a system should contain (what needs to meet and what functions to perform) (Boisson de Chazournes, 2011; Hiddleston, 2015). For APCL system, both the normative model and the functional model have certain advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, the integrity, compatibility and defensive value provided by APCL under normativism can promote the solution of the problems of inadequate integration and convergence of laws and regulations in the field of APCL, and the difficulty to highlight the diversity of subjects. At the same time, it is conducive to further compact territorial regulatory responsibility so as to accelerate the establishment and improvement of a whole process regulatory mechanism for the establishment, implementation, acceptance check, management and protection of supplementary cultivated land. However, In the field of APCL which is highly technical, policy-oriented and time-sensitive, it is difficult for the implementation of relevant policies to meet the basic elements of normativism; On the other hand, although functionalism has the characteristics of effectiveness (Mehra and Yanbei, 2017), flexibility (Sinclair, 2015), and adaptability (Shaman, 1980) in the field of APCL, it has always been unable to reach a new legitimacy basis to fundamentally solve policy failure because it only focuses on administrative goals while ignoring the value basis (Allen, 2018; Tomlins, 2012). Therefore, only when there is a priori normative rationality under the item of normativism, and the practical functional demands are met under the item of functionalism, can the cultivated land administrative protection system reasonably adapt and be flexible between norms and functions. In summary, this paper attempts to use normative analysis methods, similar case research methods as well as value analysis methods to explore and analyze relevant normative documents and administrative judicial cases, and to examine the legitimacy of APCL from the perspective of normativism and functionalism so as to clarify the difficulties in the implementation of cultivated land administrative protection policy and seek the administrative legal optimization path that is beneficial to cultivated land protection, the research path is shown in Figure 1.

Functionalism is a public law analysis perspective corresponding to normativism, which is built on the basis of demand-oriented pragmatism (Tan and Fu, 2021) compared with value-oriented normativism, which intends to examine the actual function APCL and grasp its proper value. As an overall design to meet the needs of cultivated land protection, the examination under functionalism provides an analytical path different from the test of “value legitimacy”, that is, it does not directly discuss legal norms as means, but falsifies the function of APCL at the operational level of the system (Chen, 2020) and passes the test of “demand and efficacy". This method explores how the APCL system manages its own “reproduction process” under the limitation of self-adaptation (“primary production” is the self-adaptation of the rules of APCL from the perspective of normativism). Assuming that all links in the “reproduction process” have collaborative instrumental rationality from the perspective of functionalism, administrative penalties, administrative remedies, administrative contracts and administrative public interest litigation in the APCL system can evolve into punishment needs and effects, relief needs and effects, desirable needs and effects, and public welfare needs and efficacy according to the relationship structure of “demand-efficacy”, the road map of “demand-effectiveness”actual inspection of APCL is shown in Figure 2. The traditional APCL defines the system operation link from the perspective of the administrative subject in cultivated land protection, hence its consequence is that it is generally believed that APCL is only the system of the subject, ignoring the important procedural element of the administrative counterpart of cultivated land protection (Klabbers, 2022), thus making it one-sided to focus on improving the organizational efficiency when considering the optimization of the system operation link, without fully taking into account the multiple needs of the counterpart for program optimization. It is also difficult to regulate the realistic game among the objectives, roles and behaviors of multiple subjects in cultivated land protection (Michaels, 2011). This means that when reviewing the operation links in APCL, we should pay attention to the counterpart, an important procedural subject, and highlight the important role and value of APCL system in ensuring administrative participation and public participation (Sandholtz and Stone Sweet, 2012). On this basis, from the perspective of functionalism, APCL can be divided into four links at the system operation level according to the relationship between administrative subjects and administrative counterparts in cultivated land protection: cultivated land protection administrative punishment for adjusting cultivated land administrative management relationship, cultivated land protection administrative reconsideration focusing on administrative relief relationship, administrative contract signing and fulfillment based on consensus, and the administrative public interest litigation of cultivated land protection between the procuratorate organs and the administrative organs for cultivated land protection. In addition, from the perspective of functionalism, APCL has its independent value and function whose integral value, compatibility value, and defensive value will gradually highlight. The system operation level of APCL will be reviewed, and the improvement of procedures will be included in the overall protection scope. The core function of APCL will move from protection procedures to procedural protection, from managing cultivated land to serving cultivated land, that is, its role is no longer just to regulate the system operation but to build a systematic protection concept of a diversified community of cultivated land resources. This means that the fundamental purpose of standardizing administrative procedures at the level of APCL system operation is to promote and standardize the legitimacy, fairness and efficiency of administrative acts in the field of APCL, while the direct purpose is to build a unified procedural standard, improve responsibility compensation, ecological compensation and interest adjustment through multiple means, create a positive incentive atmosphere for cultivated land protection, and finally form a farmer-centered pluralistic and co-governed cultivated land protection community with social participation and government protection. Furthermore, the procedures regulated by each link in the APCL system are the procedures for all activities, including administrative management of cultivated land protection, administrative relief and even administrative agreements, administrative public interest litigation, etc.

The Cultivated Protection Law (draft) marks the beginning of change from cultivated administrative protection under the formal law to the direction of substantive development. With the major changes in the investigation and handling measures for illegal occupation of cultivated land protection, the administrative punishment in it is no longer “formalization of punishment”, but a functional order to meet the needs of punishment with an instrumentalist attitude (Chen, 2012). However, in the specific regulations promulgated, the corresponding expression of “whistleblowing and accusation” in Article 50 of the CLPL fails to clarify whether illegal acts can be included in the scope of administrative punishment after the right holder has carried out the corresponding reporting act, and the new “order correction” clause also conflicts with the expression “ordering corrections within a time limit” in the LML. Before the promulgation of the CLPL, there were conflicts among “ordering suspension of production and business”, “ordering corrections within a time limit” and “ordering corrections” in judicial practice. In the (2020) Qingxing Shen No. 44 case (https://wenshu.court.gov.cn/), Minhe Hui Tu Autonomous County retrial court ruled that the courts of first and second instance had erroneously applied the clause of “ordering suspension of production and business” with reference to the Administrative Punishment Law and determined that Article 75 of the LAL was applied with reference to the Land Administration Law “Order corrections within a time limit” clause. In (2020) Yuxingzhong No. 1667 case (https://wenshu.court.gov.cn/), the Notice of Order to Correct Illegal Acts issued by the land administration department of Xinzheng City was judged by the court to be selective in law enforcement due to lack of legal basis. In the Jinxing Zhong 50 case (https://wenshu.court.gov.cn/), the Hequ County government’s “ordering corrections” punishment was found by the Court of Final Appeal that “it cannot be directly concluded that the main penalty decision must go through the procedure of ordering corrections before making it”. In the case of the existing disputes between “ordering corrections within a time limit” and “ordering the suspension of production and business” in the Administrative Punishment Law and the LAL, the expression “ordering corrections” in the CLPL inevitably causes administrative organs to create new functional objectives in addition to the original legislative objectives when considering the functionality of different expressions, and at the same time, the functional objectives created will also be integrated into the handling of individual cases as purposeful factors or consequential factors. As a result, the public law sector, which is highly defensive itself, has become even more resistant to functionalist interference under the influence of individual cases.

In the administrative law enforcement activities of cultivated land from the perspective of functionalism, when the existing administrative protection laws and regulations are insufficient to meet the various needs of cultivated land protection, functionalist law enforcers may give up translating administrative activities into legal administrative acts (Mi and Luo, 2021). In the case where land management agencies carry out their activities not on the basis of legal rules but on functional objectives, it is easy for law enforcement agencies to deviate in their way of thinking: confusing legal rights such as “peasants’ rights” and “land development rights” with the policy goal of “stopping illegal land occupation”, thereby abandoning legal commitments–thus creating relief needs for administrative protection of cultivated land. Taking administrative reconsideration as an example, it has been found that a very small proportion of administrative litigation was initiated in administrative judicial cases related to cultivated land protection because they are dissatisfied with the administrative reconsideration decision. Very few went through substantive hearings at the administrative litigation stage. Most of the reconsideration results were upheld at the administrative litigation stage, which means that the cases filed in the APCL had the phenomenon of procedural “idling in the previous administrative reconsideration stage. The specific phenomenon of “idling” of administrative reconsideration of cultivated land protection is shown in the following Table 2. Combined with the functionalist viewpoint of “the basis of public law is the organization” and “self-correction theory" (Peng and Zhang, 2015)., it can be seen that there are roughly three reasons for the “idling” phenomenon of the administrative reconsideration procedure for cultivated land protection: First, at the beginning of the formulation of the Administrative Reconsideration Law, The legislator intends to form a strict boundary between administrative reconsideration and administrative litigation, give full play to the internal supervision function of administrative reconsideration, and form an organizational system that specifically exercises the power of administrative reconsideration, and this boundary and sense of alienation in the field of cultivated land protection are becoming more and more obvious; Second, the implementation organs of the administrative acts of cultivated land protection are mixed, the responsibilities of the ecological environment, natural resources, agriculture and rural departments in some fields overlap, so the administrative entities are often unclear when the parties initiate administrative reconsideration and the individual organs lack the ability to conduct substantive review of the administrative reconsideration stage; Third, due to the particularity of cultivated land protection cases themselves: the investigation time of cultivated land protection cases is often lengthy, and it is difficult for administrative organs to find a balance between implementing the principle of “administrative efficiency” and conducting a full substantive review of the cases.

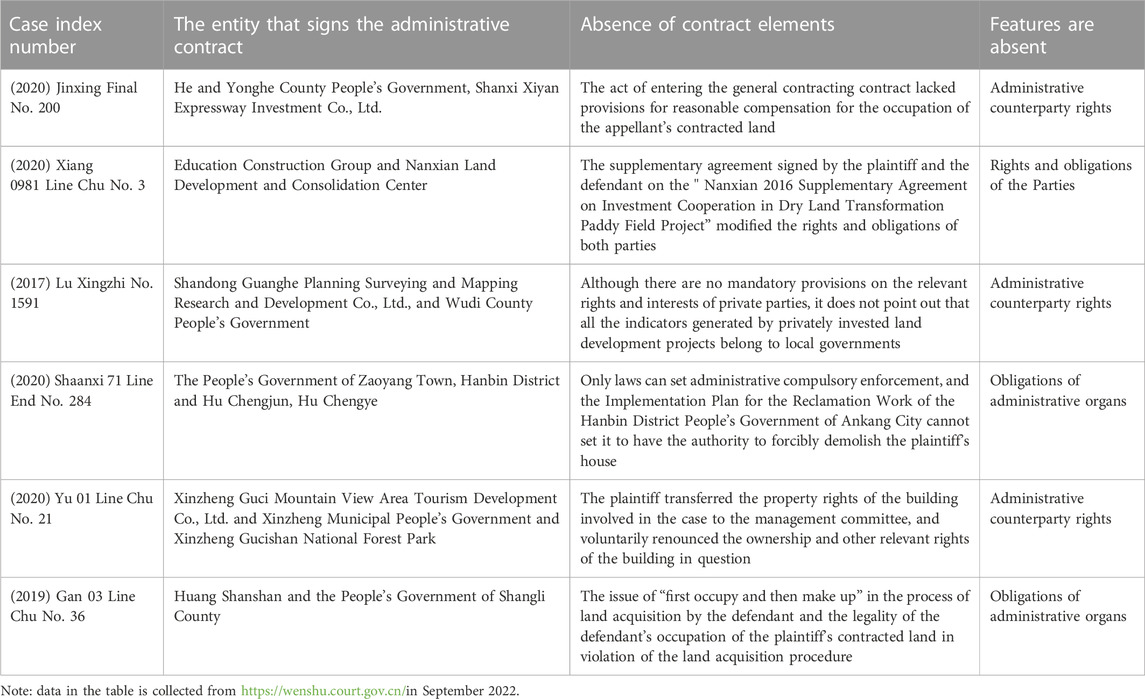

Under the accelerated flow of social capital, the public service supply capacity corresponding to the private sector is facing severe challenges, and at this time, a new purpose has emerged in shaping the relationship between administrative organs and administrative counterparts: from the perspective of functionalism, it is not for administrative organs to use administrative agreements such as basic cultivated land compensation contracts to meet public needs, nor to create a new type of contract, but to introduce a consensual-centered functional mechanism in the relationship between the two to strengthen the position of the counterparty (Li, 2020). Based on this, the search for administrative contracts for cultivated land protection based on the element structure of “rights-obligations” found that there was a lack of “rights-obligations” elements, that is, the desirable needs were not met (rights and obligations are the main contents of the agreement). In the current academic discussion, there is controversy about the dual attributes of contract and administrative nature of cultivated land protection administrative contracts, and there has been no general view on the issue of separating the two or taking both of them into account. If the contract is for administrative dominance, it mainly emphasizes the review of the legality of the actions of administrative organs in the field of cultivated land protection and the definition of public interests such as the overall plan of cultivated land protection; If the contract excludes the nature of the administrative act and is dominated by the contract, both the administrative organ and the other party may sign, modify or terminate the contract in accordance with the contract provisions in the civil law, as well as the preferential rights of the administrative organ in the administrative contract. Together, they hinder the satisfaction of desirable needs. In addition, due to the lack of supervision of cultivated land protection administrative contracts, whether it is cultivated land protection government procurement contracts or basic cultivated land protection compensation contracts, there is still no law to regulate the performance of such administrative contracts. The Regulations on Open Government Information stipulate 11 items stipulates that the government needs to actively disclose, and the Audit Law also stipulates that auditing institutions have the right to supervise the expenditure of funds under administrative contracts, but the problem of insufficient contract functions still arises one after another. The absence of specific “rights-obligations” structural elements is shown in Table 3 below.

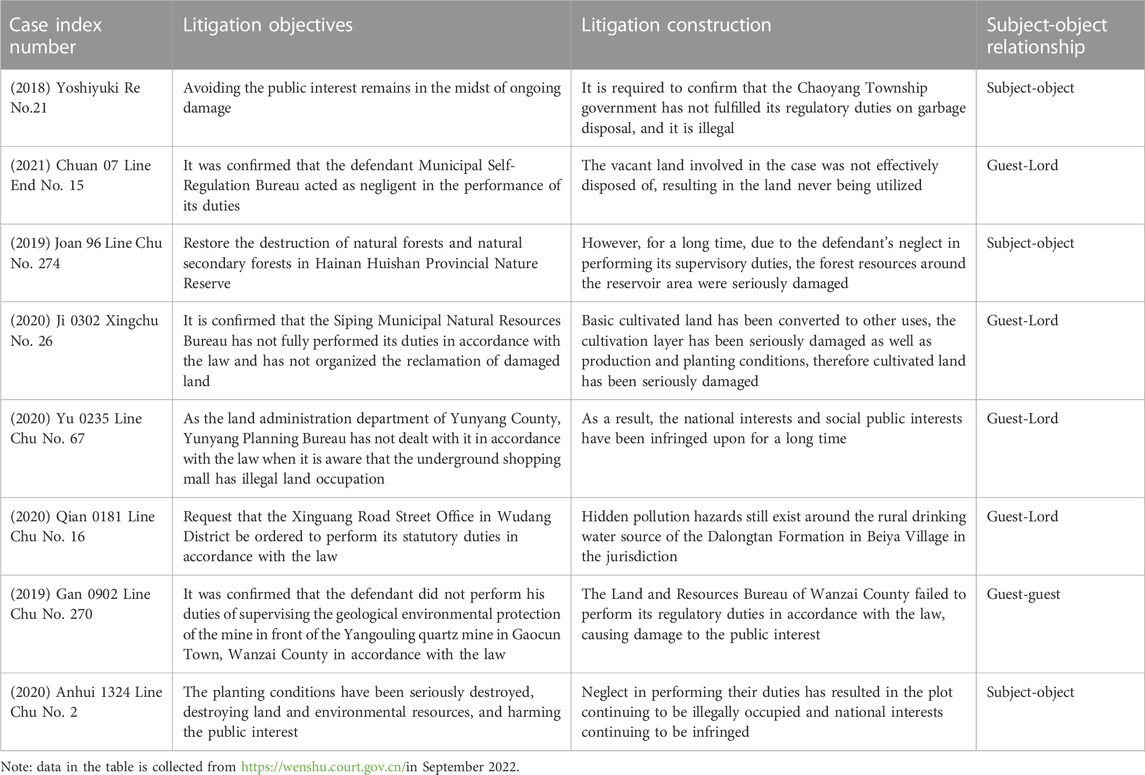

TABLE 3. Lack of structural elements of “rights-obligations” in administrative contracts for cultivated land protection.

The existing civil public interest litigation system cannot fully fill the lack of ecological value of cultivated land, and administrative organs lack initiative in performing social services such as cultivated land protection, which creates a public welfare demand for cultivated land administrative protection (Wang, 2021). The reality is that although paragraph four of Article 25 of the Administrative Procedure Law stipulates an administrative public interest litigation system in the field of ecological environment and natural resources protection, and the CLPL also stipulates a public interest litigation system in the field of cultivated land protection, however whether this type of public interest litigation is an objective litigation or a subjective litigation is not explicitly stipulated. Some administrative public interest litigations related to cultivated land protection show that the litigation objectives are objective while the litigation structure is subjective. This type of administrative public interest litigation for cultivated land protection is intended to restore objective public law order, but in fact, the focus of the trial is whether it has subjectively caused damage to the public interest of the ecological environment. In some administrative public interest litigations related to cultivated land protection, the litigation structure is objective while the litigation goal is subjective, and the purpose of litigation in such cases is to subjectively remedy public interest damage, but the focus of trial is on the objective legality of administrative acts of administrative organs. In practice, the judicial organs’ subjective judgment standards for “the public interest have not been separated from the state of infringement” are not clear, and it is difficult to form a standard of “non-performance of statutory duties” when objectively identifying the legality of administrative organs; Through further research on judicial cases, it is found that there is subjective and objective mutual exclusion in administrative public interest litigation in cultivated land protection, and the phenomenon of subjective and objective mutual exclusion in specific administrative public interest litigation related to cultivated land protection is shown in the following Table 4. This phenomenon has given rise to two secondary problems: First, subjective and objective mutual exclusion will aggravate the limitation of the subject of public interest litigation, and legislators will completely delegate the function of public interest litigation to the procuratorate, which is not conducive to the participation of third-party forces in cultivated land protection. Second, when the public interest of cultivated land protection conflicts with the development interests of local governments, the subjective and objective mutual exclusion will make it difficult for the court to choose between the two interests when adjudicating, and it is difficult to meet the public welfare needs of APCL. In addition, the limitation of litigation subjects is not conducive to the supervision of the procuratorate’s administrative actions of the government at the same level, especially in the “local development” government.

TABLE 4. Subjective and objective mutual exclusion in administrative public interest litigation for cultivated land protection.

From the perspective of normativism, the reason why the relevant normative documents in the field of APCL are applied is not due to the obedience of the counterparty in the “central-land” relationship, the “article-block” structure and the “state-farmer” relationship, but because the relevant normative documents themselves constitute a specific value judgment basis, which makes the subject behavior in the field of APCL legal or justified (Xu, 2020). Specifically, in terms of the system structure of cultivated land administrative protection, in order to avoid forming a “closed category” of one or more protection means, administrative protection should have overall balance and internal integrity in structure, and the integrity of norms in the field of cultivated land protection provides a benchmark for the balance and integrity of the protection structure; In terms of the coverage of the protected objects, administrative protection is increasingly manifested as a multi-level process involving the joint participation and interaction of many subjects, which also puts forward higher requirements for the compatibility of norms; In terms of the tasks of administrative protection of cultivated land, although with the expansion of administrative tasks and the transformation of administrative roles, “defense against violations” is no longer the central task of administrative protection, the defensive tasks of administrative protection still play an important role in policy guidance, risk regulation and other aspects in the field of cultivated land protection. In a general sense, the generation of value determines the efficacy and demand satisfaction of the system and efficacy is the external expression of the legitimacy of the system (Zhu and Deng, 2021). And the significance of exploring the legitimacy of the value of APCL is to make the characteristics of administrative protection play a role in the field of cultivated land protection. In addition, “under a specific norm, value, belief and understanding system” is the basis for evaluating legitimacy (Guo, 2006). In the specific context of APCL, the overall value inhabits the overall protection requirements of “cross-level and cross-region”; The value of compatibility lies in the behavior of diverse subjects in specific situations While defensive value lies in the regulation of local government, the relationship between several value legitimacy of APCL is shown in Figure 3.

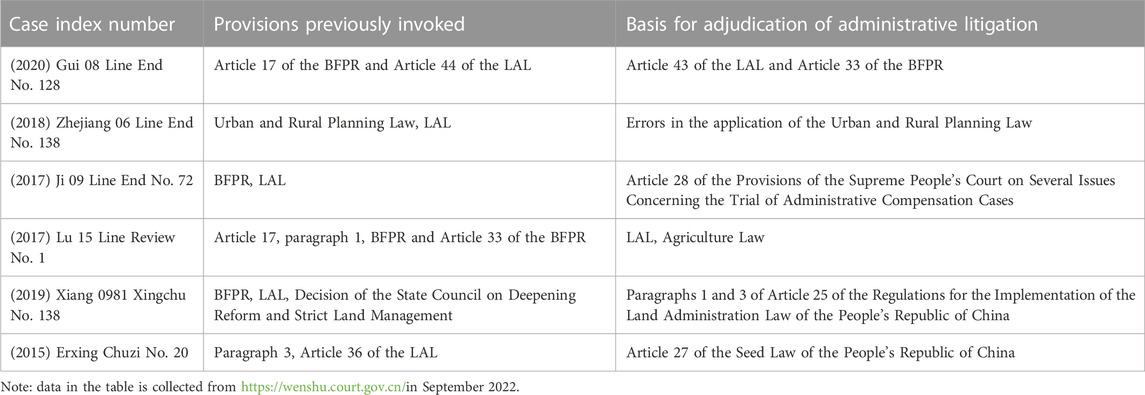

The CLPL points out in the description that the law aims to solve the problem of lack of unified and effective connection of laws and regulations in the field of cultivated land protection at this stage to create overall value. However, there is still a certain degree of isolation and fragmentation between CLPL and the BFPR, the LAL and other regulations. Under the normative analysis: First, in the CLPL promulgated, Article 20 regulates the “balance of in-and-out” system of cultivated land and stipulates that supplementary Land must be both qualitative and quantitative. But the LAL stipulates that when the construction of relevant projects occupies basic cultivated land, it can be supplemented by paying a certain reclamation fee as an entity alternative behavior. Second, article 83 of the LAL refers to the fact that the land administration department does not have compulsory enforcement powers, which is not explained in the CLPL and the BFPR. Third, The CLPL Draft does not inherit the article 18 of the punishment of idle cultivated land and the article 33 of the punishment of unused cultivated land for other purposes in BFPR, but instead stipulates that the article 75 of the LAL as the punishment. Articles 18 and 33 of the BFPR and Article 75 of the LAL have long been confused in judicial practice. In addition, the BFPR only stipulated that the main body responsible for the destruction of basic cultivated land was “destroying or changing the mark of the basic cultivated land reserve without authorization”, and it was unclear whether the double penalty system should include both units and individuals or the single penalty system of units or individuals, and the CLPL did not make targeted additions and modifications to this. In the scattered provisions of normative documents such as the new law and the old law, the special law and the general law, and the superior law and the lower law, it is difficult to highlight the overall value of APCL. The specific phenomenon of regulatory fragmentation is shown in Table 5 below.

TABLE 5. Cases of administrative protection of cultivated land are scattered according to laws and regulations.

In order to expand the participation space of social capital, break the restrictions between traditional departments, levels and subjects, and form a cooperative pattern between government and social subjects, it is urgent to improve the compatibility of APCL which is only meaningful when it operates in a specific cultivated land protection social relationship (Wu and Shen, 2021). When the protection means cannot effectively coordinate the value identity between subjects, the protection loses its compatibility, leading to the phenomenon of “rejection” in practice. Different from the holistic value, which focuses on the self-adaptation of rules, the compatibility value focuses on whether the behavior of multiple subjects can be coordinated in specific situations. From the perspective of normativism, the main body of cultivated land administrative protection policy-making, the implementation subject and other stakeholders have their own behavioral logic and rational thinking; If the three cannot be coordinated and released together, it will lead to the ability to erode compatibility (Yang, 2021) under the influence of relevant interests, thereby diverting and restricting administrative protection of cultivated land. Among the existing legal norms, whether it is the CLPL or the LAL, there is a phenomenon that the provisions of the guaranteed subjects (government organs at all levels) are clear, but the basic subjects (collective economic organizations and their members) and social subjects are insufficient. The rights, obligations and responsibilities in the relevant norms must be realized by relying on the behavior of the subject. And “Grow Teeth” hard measures can be implemented not only by setting the relevant government as the subject of responsibility. Since it is inferred from the ex officio interpretation in Article 50 of the CLPL that collective economic organizations and their members have become the subject of legal relations related to cultivated land protection, peasants should also be included in the law as subjects in the state of course. After all, relative to the subject of legal relations, legal subjects are only “potential subjects”, and at the same time, this is also the proper meaning of “land to the tiller”. In addition, under normativism, the law relies on the reverse method of “person-right, responsibility-behavior” to construct a direct connection between legal subjects and real life, therefore under Article 46 of the CLPL, “social investors” naturally lose their status as legal subjects in the absence of provisions on the connotation of rights and responsibilities, which is also contrary to the original legislative intention of “who invests, who benefits”.

Under the current trend of emphasizing the transformation of cultivated land protection subjects from the government to farmers and forming a cultivated land protection model guided by the government and the participation of peasants and enterprises, how to strengthen the regulation and control of local governments in administrative protection has become a major difficulty. From the perspective of normativism, the regulatory role of the administrative protection system on local governments is mainly reflected in the aspects of ex post restriction and judicial review (Liu, 2018), and compared with the preventive review of ex ante review, the APCL under the “strictest system” is highly defensive. Compared with the thin provisions on government responsibility in the LAL, the CLPL initially realizes the “rule of law of political responsibility” in the field of cultivated land protection by incorporating political responsibility into the law. In order to highlight the defensive value, realize the transformation from the legitimacy of power to the legitimacy of behavior, and further consolidate the territorial regulatory responsibility, it is also necessary to realize the transformation from “consistency of rights and responsibilities” to “unity of rights and obligations". The transformation of norms and obligatory norms makes it difficult to make “power and responsibility” a relatively clear “duty and authority” in the field of law. On this basis, the relevant provisions of the CLPL transform the investigation of political responsibility into the pursuit of legal responsibility under the framework of “behavior-result”, and then political principles should be transformed into legal principles under the framework of “norm-value”, to realize “judicial decisions” in the field of APCL. In addition, according to the principle of political responsibility of “who authorizes, who is accountable”, the subject of accountability to local governments in Article 59 of the CLPL should be the people (or citizens). Although the defensive value is reflected in this interpretation, under this interpretation, the legitimacy of Article 59 of the CLPL derives from the rationality of the allocation of rights and obligations, and the value basis of “who authorizes, who is accountable” lies in the affinity to the people. The difference between the two makes political responsibility unable to be legalized at this time. Therefore, it can be inferred that the basis of “accountability” here lies in the “accountability” between superiors and subordinates in the internal relationship of the administration, but this is contrary to defensive values.

The main purpose of administrative protection is to achieve the stability of order while the realization of order stability depends on the legitimacy of the system (Zhou, 2020). From the perspective of normativism, the system operation rules formulated should maintain integrity, compatibility, and defensiveness for a certain period of time in order to meet the requirements of overall protection, diversification of subjects and interference of regulatory administrative power in cultivated land protection. However, from the perspective of functionalism, the demand for cultivated land protection is developed in change, and the growth of rules is a time-consuming process. From the BFPR to the promulgation of the CLPL, from partial norms to overall norms, in the process of gradual development of system rules, there is always an adaptive relationship between rule values and needs. When the opposition and adaptation between essence and existence, value and demand are dissolved into the loop of the infinite cycle of APCL, it is manifested as a circular demonstration process that mixes value and demand. As a result, the APCL is transformed into a “fluid” without vertices and layers. To avoid the occurrence of this phenomenon, the value basis of APCL should be disassembled with “norms” as noumenon and “functions” for use, specific norms and coordination should be carried out on the basis of dismantling, and the protection means should be specifically carried out after coordination, so as to realize the legitimacy of APCL, and the path map for achieving the legitimacy of APCL is shown in Figure 4.

The system of laws and regulations on the APCL is viewed from a holistic perspective, the CLPL is perceived as the Basic Law, and the LAL and the BFPR are also important parts of the system. As a comprehensive protection system, the legal regulation and control methods of administrative law and other departmental laws has gradually been integrated into the APCL in the process of development. Among them, the Administrative Punishment Law regulates the punishment behavior of land administrative departments, the Administrative Reconsideration Law corrects the improper behavior of land management organs in the process of law enforcement, and the relevant administrative regulations on administrative public interest litigation and administrative contracts all play a role in the implementation of cultivated land protection policies. However, the existing traditional law departments do not adapt to specific legal issues related to cultivated land protection, and the isolated and scattered issues of laws and regulations such as the CLPL are difficult to coordinate in the field. In the overall value analysis under normativism, the dispersion between Article 20 of the CLPL and the LAL is essentially the absence of a consensual function. Under Article 20 of the CLPL, administrative contracts are dominated by administrative nature, while under the relevant provisions of the LAL, they are dominated by contracts. On the issue of succession between Article 18 of the CLPL and the BFPR, as well as the issue of “ordering corrections” in Article 50 of the CLPL, it is difficult for the systematic punishment function to effectively intervene. Under the premise of maintaining the integrity of the APCL system, if we want to use the traditional departmental law basis to solve the problem of isolation and dispersion of norms in the field, it is necessary to disassemble the function of agreeing and punishing of the overall value.

From the perspective of compatibility value of APCL, the “three subjects” recognized in the field of cultivated land protection include governments at all levels, rural collective economic organizations, and actual land users (farmers or new business entities), but the regulation and control mean of APCL are still mainly “government-peasants”. At present, the dualization of protection means and the lack of protection for new business entities have reduced the predictability of the behavior of social subjects, therefore it is inevitable that interests will be resisted and pluralistic will be divided. In the above-mentioned judicial cases, on the one hand, social subjects encounter administrative squeeze in cultivated land protection, on the other hand, even if social subjects participate in the actual work of cultivated land protection, the lack of public and private social responsibility of cultivated land interests urgently requires due regulation by the administrative protection system. At this time, the relevant subject responsibility should be clarified in the cultivated administrative protection system. The extensive participation of multiple subjects dilutes the clarity of the subject responsibility to some extent, which makes it difficult to identify and determine the main responsibility. In the face of complex social relations, it is necessary to rely on the subject normative system that combines punishment and relief, in which the legal punishment function is used for non-performance of subject responsibilities and legal remedies are given to those who are still squeezed after performing subject responsibilities to ensure diversity instead of a vicious circle of prevarication. By dismantling the compatibility value according to the punishment and relief functions, establishing the legitimacy of the entity and the predictability of the responsibility, the reasonable limit of all parties participating in cultivated land protection is confirmed while the enthusiasm of social subjects to participate in cultivated land protection is fully mobilized so as to realize the legitimacy of APCL.

In addition, it cannot be denied that in the field of cultivated land protection at this stage, government governance is in a guiding and dominant position, and in the process of further shrinking and adjusting government power, APCL should be more open and rational. On the basis of giving play to defensive value, it empowers the integration of government governance elements in the field of cultivated land protection. First, through the punishment function (necessary expansion and reasonable restriction of the scope of punishment), the government governance matters are standardized, institutionalized and procedural; Second, through the relief function, the deviation of administrative counterparts’ understanding of administrative behavior should be reversed, and build a communication hub between public participation, public management and government management, to meet the current trend of emphasizing openness and two-way government governance model. The third is to urge administrative organs to optimize cultivation and protection social services through public welfare functions, perform corresponding duties, and change from “cultivated land management” to” serving cultivated land,” in order to force the government to face new contradictions and make the right choice in the new development stage in the “changing” and “unchanged” new environment.

In order to highlight the integrity, compatibility and defensive value of APCL, and at the same time fully meet the punishment, relief, desirability and public welfare needs of APCL, the standardization and coordination of the CLPL should be carried out on the existing basis of the CLPL in terms of regulatory inheritance, subject construction, and responsibility subdivision. First of all, “the land replenished must be both qualitative and quantitative” should be clarified in the CLPL and free of the previous conflict of “alternative act” between BFPR and LAL; At the same time, the “compulsory law enforcement power” of land administration organs should be explained to solve the problems of the punishment of idle cultivated land and unused cultivated land for other purposes. And the issue of inheritance of penalties for idle cultivated land and cultivated land for other purposes under the CLPL and the BFPR on idle cultivated land and diverted cultivated land for other purposes needs to be fully discussed before the law is formally promulgated. Secondly, in terms of subject construction, in order to cope with the tendency of dualization of subjects in the old regulations, the structure of basic subjects (collective economic organizations and their members) + social subjects + security subjects (land administration departments, etc.) can be further derived on the basis of the “three subjects” and clarified in the CLPL. In addition, although the CLPL clarifies the responsibilities of local governments at all levels in the special chapter on “Legal Liability”, the regulation and control of local governments’ powers cannot be achieved overnight by stipulating responsibilities, therefore should be regulated by law from the time of decision-making, from “political decision” to “judicial decision".

At the same time, on the basis of the transformation of the CLPL, the adoption of “Grow Teeth” hard measures requires multiple measures to be further continued on the LAL and other regulations. To solve thorny problems such as the low level of relevant laws and regulations as well as the cross-border behavior of local governments, resolute and decisive measures are required. Strictly abide by the red line of 1.8 billion mu of cultivated land, sign a written guarantee of power and responsibility between the central and local governments, and use it as a hard target when evaluating political performance, implement an inspection policy that does not miss any criteria for evaluation, directly veto a certain leading cadre who does not meet the standard, and who bears the main responsibility can still be held accountable after leaving in order to strictly enforce the law and pursue responsibility. The revision of land regulations and the implementation of the “Grow Teeth” hard measures should focus on two points in the continuation of laws such as the LAL. Firstly, before the promulgation of the CLPL, the relevant provisions of the LAL should first be optimized: the clause “ordering corrections within a time limit” in Article 75 should be given the effect of administrative punishment, or the “ordering correction within a time limit” clause should be banned by referring to the application of the “order to stop production and business” clause of the Administrative Punishment Law of administrative acts in the field of land management in the subordinate position of administrative punishment measures; Grants the land and resources administration department the power to require the person involved to restore the basic cultivated land occupied, and restricts the authority and operating procedures of this power under Article 85, so as to avoid blind expansion of administrative power based on the improved provisions of Article 85; Based on the penalties imposed in Article 33, Article 18 of the BFPR was absorbed to consolidate the content of the article to avoid excessive penalties; There should be new provisions to regulate the idle use of basic cultivated land and prohibit the government’s erroneous cadastral registration and blind “drought to water” projects. Secondly, low-level laws and regulations should be optimized, and the compensation subjects of the “interim measures for compensation and incentives for cultivated land protection” and “measures for the protection of basic cultivated land economic compensation” in various provinces and cities should be uniformly stipulated in accordance with central policies, to avoid the situation that compensation responsibilities are not in place. In the “implementation rules for the work of accounting for supplementary balance” and other documents of various provinces and cities, the source of “supplement” land should be clarified, as well as the dual requirements of quantity and quality. In addition, under the unified planning of the LAL, each local government rule and regulation should make detailed provisions on the land reclamation tenure adjustment plan and the source of funds for land development and consolidation and issue the “Cultivated Land Protection Land Tenure Management Plan” and “Cultivated Land Protection Fund Management Measures” as soon as possible. The main responsibility of the government for errors in cadastral registration and the registration matters for changes in land ownership and use rights should also be clarified. A special cultivated land fund for cultivated land protection which is composed of part of the paid use fee for construction land and the conversion fee of cultivated land input by social capital investment should be set up to subsidize the loss of cultivated land of landless peasants.

In the supporting aspect of the risk prevention and control mechanism, firstly, the CLPL, the LAL and other relevant laws and regulations should be guided by more principles on the basis of clear rules. In the conflict prone period of the transformation of cultivated land use, the complexity of the interests and relationships of cultivated land makes the clear value of existing laws and regulations unable to maintain a good adaptability to cultivated land governance. Therefore strengthening the principle guidance of relevant laws and regulations, and forming a supporting application of rule-based governance and principle—based governance can not only deal with the new form of atypical food security risks, but also promote the further maintenance of the overall value of laws and regulations in the field of cultivated land protection. Secondly, in the regulations on cultivated land protection issued by the local government, the undertake and distribution of legal responsibility should be more preventive in advance to fill the information gap between the land destroyers (i.e. risk makers) and the victims, Meanwhile, it will prove that the burden distribution also turns from the victims to the makers, forcing the makers to maintain the obligation of observation at all times to ensure that the use of cultivated land and the technical level of pollution prevention and control are synchronized. Finally, basic laws and administrative regulations such as the CLPL and local government rules should be balanced between stability and flexibility. The administrative protection system of cultivated land should also consciously absorb soft law sources such as cultivated land governance policies, industry norms and professional standards in the ecological field, which is conducive to meeting the diversity requirements of legal order of risk prevention and control in the field of cultivated land protection.

After the “function” dismantling of the “normative” orientation, in the specific development of the punishment function, determining the standard for scope of punishment is on the top priority. First, the cultivated land protection policy must be used as the previous guide, and the requirements of lawful administration must also be met under the premise of meeting the cultivated land protection policy. The purpose of administrative punishment is to prove the legality of administrative acts made by administrative organs, such as administrative organs imposing extremely high fines on acts that cause land damage e.g., excavation, collapse, and occupation to meet the first point. However, it would lack legality and meet the requirements of administration in accordance with law which makes it difficult to enter the scope of administrative punishment. Second, it must have the validity of administrative management. If the administrative organ imposes a penalty on it for confiscation of illegal gains, it does not have the effectiveness of administrative management under this item, because it lacks obvious benefits to cultivated land. On the contrary, forcing the offending unit to reclaim the damaged cultivated land meets the requirements under this and satisfies the first two points of the functional system. Third, it is necessary to have the economy of maintaining the implementation of cultivated land protection policies. Fourth, if the acts that meet the functions of the first three points are interpreted as administrative punishments, it will greatly increase the law enforcement costs of administrative organs and the judicial costs of court trials, and at this time, it is also necessary to summarize the common measures for administrative punishment of cultivated land in judicial practice. The administrative measures that meet the requirements of the first three functions and have a high probability of appearing will be interpreted as administrative penalties. In summary, administrative measures that meet the four requirements in the functional system have the nature of administrative penalties, and vice versa.

In terms of the public welfare function of cultivated land administrative protection, judging from the provisions of the current law, procuratorial suggestions are only unnecessary links in the legal supervision process, which will not have a substantial impact on the rights and obligations of the parties, and are not a precursor process with procedural coercion in the measures to deal with the expansion of government power. In view of the problem that the relief needs are difficult to meet, and the defensive value is fragile in the judicial practice of cultivated land protection administrative public interest litigation, it is urgent to integrate the procuratorial recommendations in the field of cultivated land protection in accordance with the effect of special procedures to urge the government to perform public service functions and continue to provide “beneficial goods” for the society. In the context of the blind expansion of administrative power and the lack of prominent subjects of government responsibility for cultivation and protection, if the administrative organ still refuses to correct the corresponding rigid behavior after the procuratorial organ has fulfilled the soft procedures recommended by the procuratorate, the reality shows that the court ruling, as the last line of defense, may not achieve procedural justice. Therefore, in the field of administrative public interest litigation, procuratorial recommendations should be given binding force in the sense of a rigid system, that is, they should have an impact on substantive legal relationships. And in the case that the administrative organ ignores the content of the procuratorial recommendation, the procuratorial organ may apply to the people’s court directly to enforce the refusal to make corrections. For the issue of fragile defensive value, making procuratorial recommendations binding can effectively transfer the pressure of courts in cultivation and protection trials, highlight the functions of procuratorial organs in public interest litigation, strengthen the unified understanding and application of the subjective and objective aspects of litigation structure and litigation purpose as well as promote the judicial community. Reconstructing the judgment of the constituent elements such as “the public interest has not been separated from the state of infringement” and “non-performance of statutory duties” is conducive to strengthen the supervision of the procuratorate over the actual work of cultivated land protection by governments at the same level, so as to curb the expansion of administrative power while promoting the participation of social capital in cultivated land protection. It is worth noting that when urging the government to export “beneficial goods”, it should be wary of the government’s “beneficial” output above individual rights and interests. Once a certain government action in the field of cultivated land protection is marked as beneficial, the public interest and public demand reflected behind it become untestable concepts. And under the intersection of needs to be verified and untestable reality, the government may be pushed onto the altar of the tester, thus assuming its own function of defining what is “beneficial”. At this stage, when the procuratorial recommendations have not yet been given enforcement power, how to promote the procuratorial recommendations in the field of cultivated land protection to accurately identify beneficial public goods and give full play to the rigid enforcement effect of flexible supervision rights needs to be gradually improved in practice.

For the relief function, in response to the crisis that the public welfare needs of cultivated land administrative protection cannot be met, it is necessary to establish an administrative reconsideration committee for cultivated land protection, so as to improve the efficiency of the government’s system of self-inspection, self-correction and self-supervision. In committees, personnel selected by the land administration organs should be assigned to exercise the power of administrative reconsideration in an overall manner, and the judicial administrative departments should select personnel to undertake administrative reconsideration tasks within a detailed framework. The reconsideration organs, reconsideration bodies and reconsideration committees rely on each other in their duties and constrain each other in terms of authority. The exercise and supervision of powers should be integrated, which is conducive to the unification of reconsideration resources, the institutionalization of reconsideration powers, and the standardization of reconsideration basis, while enhancing the people’s confidence in the administrative reconsideration system and gradually making administrative reconsideration one of the main ports for dredging administrative disputes. In addition to administrative reconsideration, it is also necessary to carry out external supervision of the implementation process of the three major systems of cultivated land protection to supervise, restrict and contain them, so as to activate and increase the institutional stock of the basic cultivated land protection system, strengthen the institutional authority of the cultivated land occupation and supplement balance system and improve the implementation efficacy and utilization performance of the land development, consolidation and reclamation system. Effectively link legal supervision and disciplinary supervision in the field of cultivated land; Solve problems such as the connection of land evidence materials, the screening of default and violation of law of land administrative contracts, and the separation of preliminary investigation by land administrative organs from the investigation and collection of evidence by judicial organs; Taking the spirit of legislation and the central directives on cultivated land protection as the guiding principle, make efforts on “constant” and “long-term”; Form a good atmosphere of supervision and acceptance of supervision in the realization of procedural justice and protection of rights and promptly punish problems discovered daily in accordance with the law. Improve the system for conducting special inspections, investigations and studies on phenomena such as non-disclosure and opacity in administrative law enforcement in the field of cultivated land protection; Dig deep into the mechanism behind illegal problems while dealing with them, and fully study and judge the ecological problems of cultivated land and the political and judicial ecological problems behind them. At the same time, give full play to the visual and close-up advantages of the land administration department in the corresponding problems, on the one hand, establish a yardstick for the all-round coverage of cultivated land problems, and on the other hand, focus on important projects in the approval of cultivated land projects. Prevent small things from evolving and grasp small problems as soon as possible.

In order to “firmly adhere to the red line of 1.8 billion mu of cultivated land,” the strictest measures for the protection of cultivated land have been adopted from the central to the local level in China. But at the same time, the urgency of cultivated land protection remains. Faced with the problems of insufficient unified collection of laws and regulations in the existing fields and lack of effective connection between all aspects of administrative protection, this paper provides a rational examination path for actual testing in “demand-efficacy” and due reflection under “norm-value.” And on this basis, a new idea of APCL is proposed: “function” is disassembled based on the “normative” orientation, and “specification” coordination is carried out after that, then specific protection means will be implemented, which gives full play to the effect of cultivated land administrative protection, so as to realize the “norms” as the noumenon and the “functions” for the use in the field of APCL. Cultivated land is the material basis of food security and the “ballast stone” of economic security, and the new ideas will provide a certain theoretical basis for scientific research and judgment on new problems and new needs in the field of APCL and food security.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFD1900700).

The authors would like to thank the reviewers and editors for the helpful suggestions for this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Andreescu, M., and Puran, A. (2022). Aspects of contemporary social and legal normativism. Pandectele Romane 120. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/rpanderom2022&div=32&id=&page=.

Allen, C. H. (2018). Determining the legal status of unmanned maritime vehicles: formalism vs functionalism. J. Mar. L. & Com. 49, 477. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/jmlc49&div=27&id=&page=.

Bastos, F. B. (2021). Doctrinal methodology in EU administrative law: Confronting the “touch of stateness=. Ger. Law J. 22 (4), 593–624. doi:10.1017/glj.2021.20

Bell, J. (2021). Sources of dynamism in modern administrative law. Oxf. J. Leg. Stud. 41 (3), 833–853. doi:10.1093/ojls/gqaa057

Boisson de Chazournes, L. (2015). Functionalism! Functionalism! Do I look like functionalism? Eur. J. Int. Law 26 (4), 951–956. doi:10.1093/ejil/chv065

Chen, R. (2012). Normative analysis of "social public interest" in economic law: From the perspective of functionalism. J. Hunan Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 26 (02), 152–156. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=HDXB201202033&DbName=CJFQ2012.

Chen, H. (2020). On the construction of functionalist legal interpretation theory. Mod. Law 42 (06), 48–61. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=XDFX202006004&DbName=CJFQ2020.

Chiti, E. (2016). Is EU administrative law failing in some of its crucial tasks? Eur. Law J. 22 (5), 576–596. doi:10.1111/eulj.12203

Cooper, S. W. (1993). Considering power in separation of powers. Stan. L. Rev. 46, 361. doi:10.2307/1229187

de Casimiro, L. M. S. M., and de Sousa, T. P. (2020). A tutela do direito à saúde pela administração pública: Delineando o conceito de tutela administrativa sanitária. Rev. Investig. Const. 7, 601. doi:10.5380/rinc.v7i2.71320

Didikin, A. (2018). “Platonism and normativism: A historical and philosophical reconstruction,”. SCHOLE-FILOSOFSKOE antikovedenie I klassicheskaya traditsiya-schole-ancient philosophy and the classical tradition, 12, 709–713. doi:10.21267/schole.12.2.27

Eckes, C., and Mendes, J. (2011). The right to be heard in composite administrative procedures: Lost in between protection? Eur. Law Rev. 36, 651–670. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2092855.

García Berger, M. (2015). An analysis of the dispute between exclusive and inclusive legal positivism from a neokantian-kelsenian perspective. Isonomía 43, 77–96. doi:10.5347/43.2015.73

George, M. (2008). Comparability, functionalism, and the scope of comparative law. Hosei Riron 41 (1), 1.

Gersen, J. E. (2020). Administrative law's shadow. Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 88, 1071. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/gwlr88&div=32&id=&page=.

Guo, X. (2006). The decline and reconstruction of normative legitimacy theory. J. East China Normal Univ. (Philosophy Soc. Sci. 2006 (03), 49–56. doi:10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5579.2006.03.012

Han, H., Peng, H., Li, S., Yang, J., and Yan, Z. (2022). The non-agriculturalization of cultivated land in karst mountainous areas in China. Land 11 (10), 1727. doi:10.3390/land11101727

Handrlica, J. (2018). Revisiting international administrative law as a legal discipline. Zb. Pravnog Fak. Sveučilišta u Rijeci 39 (3), 1237–1258. doi:10.30925/zpfsr.39.3.5

Hiddleston, E. (2011). Second-order properties and three varieties of functionalism. Philos. Stud. 153 (3), 397–415. doi:10.1007/s11098-010-9518-z

Klabbers, J. (2014). The emergence of functionalism in international institutional law: Colonial inspirations. Eur. J. Int. Law 25 (3), 645–675. doi:10.1093/ejil/chu053

Klabbers, J. (2022). “Beyond functionalism,” in The cambridge companion to international organizations law (Cambridge University Press), 7. Available at: https://sc.panda321.com/extdomains/books.google.com/books.

Li, H. (2020). On the improvement of China's administrative punishment system——a commentary on the administrative punishment law of the people's republic of China (revised draft). J. Law Bus. 3 (06), 3–18. doi:10.16390/j.cnki.issn1672-0393.2020.06.002

Li, X., Zhang, W., and Peng, Y. (2016). Grain output and cultivated land preservation: Assessment of the rewarded land conversion quotas trading policy in China’s Zhejiang province. Sustainability 8 (8), 821. doi:10.3390/su8080821

Li, C., Wang, X., Ji, Z., Li, L., and Guan, X. (2022). Optimizing the use of cultivated land in China’s main grain-producing areas from the dual perspective of ecological security and leading-function zoning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (20), 13630. doi:10.3390/ijerph192013630

Lin, L., Ye, Z., Gan, M., Shahtahmassebi, A. R., Weston, M., Deng, J., K., et al. (2017). Quality perspective on the dynamic balance of cultiva-ted land in Wenzhou, China. Sustainability 9 (1), 95. doi:10.3390/su9010095

Liu, D. (2018). Process review: Research on judicial review methods of administrative acts. China law. 2018 (05), 122–140. doi:10.14111/j.cnki.zgfx.2018.05.007

Liu, X., Zhao, C., and Song, W. (2017). Review of the evolution of cultivated land protection policies in the period following China’s refor-m and liberalization. Land use policy 67, 660–669. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.012

Marszał, M. (2020). Idea prawa” w normatywistycznej teorii Szymona Rundsteina. Przegląd Sejm. 5(160) (5), 83–95. doi:10.31268/ps.2020.66

Mehra, S. K., and Yanbei, M. (2017). “Against antitrust functionalism: Reconsidering China’s antimonopoly law,” in Law and the market economy in China Routledge, 157–207.

Mendes, J. (2022). The foundations of EU administrative law as a scholarly field: Functional comparison, normativism and integration. Eur. Const. Law Rev. 18, 706–736. doi:10.1017/S1574019622000438

Merlino, A. (2021). Vittorio Frosini und das Recht als Morphologie der Praxis. Arch. für Rechts-und Sozialphilosophie 107 (3), 452–460. doi:10.25162/arsp-2021-0023

Metzger, G. E. (2010). Ordinary administrative law as constitutional common law. Columbia Law Rev., 479–536.

Mi, Y., and Luo, B. (2021). Reform of collective ownership system of cultivated land from the perspective of functionalism: A political economy interpretation of the rural land contracting law. China Rural. Econ. 2021 (09), 36–56. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=ZNJJ202109003&DbName=CJFQ2021.

Michaels, R. (2011). “The functionalism of legal origins,” in Does law matter, 21–39. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2240928.

Morgenthau, H. J. (2017). “Positivism, functionalism, and international law,” in The nature of international law. Routledge, 159–184.

Peng, B., and Zhang, Z. (2015). Research on public policy failure: Based on the analysis of interest balance and policy support. J. Natl. Acad. Adm. 2015 (01), 63–68. doi:10.14063/j.cnki.1008-9314.2015.01.008

Petersen-Rockney, M., Baur, P., Guzman, A., Bender, S. F., Calo, A., Castillo, F., T., et al. (2021). Narrow and brittle or broad and nimbleCoparing adaptive capacity in simplifying and diversifying farming systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, 564900. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2021.564900

Pojanowski, J. A. (2019). Neoclassical administrative law. Harv. L. Rev. 133, 852. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/hlr133&div=49&id=&page=.

Rosenbloom, D. H., and Piotrowski, S. J. (2005). Outsourcing the constitution and administrative law norms. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 35 (2), 103–121. doi:10.1177/0275074004272619

Sandholtz, W., and Stone Sweet, A. (2012). Neo-functionalism and supranational governance. Oxf. Handb. Eur. Union 18, 33. Available at: aHR0cHMlM0ElMkYlMkZjb3JlLmFjLnVrJTJGZG93bmxvYWQlMkZwZGYlMkY3MjgzNDkzNg==.

Scholtes, J. (2019). The complacency of legality: Constitutionalist vulnerabilities to populist constituent power. Ger. Law J. 20 (3), 351–361. doi:10.1017/glj.2019.26

Segado, C. J. (2013). El poder judicial y la defensa de la Constitución en Carl Schmitt. Rev. Estud. políticos 161, 41–67. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4461337.

Shaman, J. M. (1980). The choice of law process: Territorialism and functionalism. Wm. Mary L. Rev. 22, 227. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/wmlr22&div=16&id=&page=.

Sinclair, G. F. (2015). The original sin (and salvation) of functionalism. Eur. J. Int. Law 26 (4), 965–973. doi:10.1093/ejil/chv061

Su, D., Wang, J., Wu, Q., Fang, X., Cao, Y., Li, G., et al. (2022). Exploring regional ecological compensation of cultivated land from the perspective of the mismatch between grain supply and demand. Environment. Dev. Sustain., 1–26.

Tan, Z., and Fu, D. (2021). From normative procedure to procedural norm: Administrative procedures and their development. Adm. Law Res. 2021 (01), 26–41. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=XZFX202101003&DbName=DKFX2021.

Taraborin, R. S. (2021). Agrarian society in transition: The adaptive potential of law. EDP Sci. 282, 08005. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202128208005

The Central People's Government of the PRC (1985). Outline of China's general land use plan (1985-2000). Retrieved from: http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/.

The Central People's Government of the PRC (1997). Outline of China's general land use plan (1997-2010). Retrieved from: http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/.

The Central People's Government of the PRC (2006). Outline of China's general land use plan (2006-2020). Retrieved from: http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/.

Tomlins, C. (2012). What is left of the law and society paradigm after critique? Revisiting gordon's “critical legal histories”. Law Soc. Inq. 37 (1), 155–166. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.2011.01280.x

Tschorne, S. I. (2020). What is in a word? The legal order and the turn from ‘norms’ to ‘institutions’ in legal thought. Jurisprudence 11 (1), 114–130. doi:10.1080/20403313.2019.1699321

Wang, W. (2021). The choice of proceduralist approach to the codification of administrative law in China. China law. 2021 (04), 103–122. doi:10.14111/j.cnki.zgfx.2021.04.006

Weinrib, J. (2021). Maitland's challenge for administrative legal theory. Mod. Law Rev. 84 (2), 207–229. doi:10.1111/1468-2230.12573

Whytock, C. A. (2009). Legal origins, functionalism, and the future of comparative law. BYU L. Rev. 1879. Available at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/byulr2009&div=62&id=&page=.

Wu, Y., and Shen, X. (2021). The transformation of cultivated land protection governance in China: Supply, regulation and empowerment. China Land Sci. 35 (08), 32–38. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=ZTKX202108004&DbName=CJFQ2021.

Xiao, L., Yang, X., Cai, H., and Zhang, D. (2015). Cultivated land changes and agricultural potential productivity in mainland China. Sustainability 7 (9), 11893–11908. doi:10.3390/su70911893

Xu, J. (2020). Administrative agreements from the perspective of functionalism. J. Leg. Res. 42 (06), 98–113. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=LAWS202006006&DbName=CJFQ2020.