- 1School of Accounting, Capital University of Economics and Business, Beijing, China

- 2School of Economics and Management, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

- 3School of Economics and Management, Beijing Institute of Petrochemical Technology, Beijing, China

In recent years, governments worldwide have paid more attention to environmental issues, and green innovation is essential to balance economic growth and environmental sustainability. This article investigates the different impacts of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation of heavy-polluting and non-heavy-polluting firms using the sample of listed firms in China from 2011 to 2019. We find that the relationship between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation is consistent with the “U”-shape in heavy-polluting firms. However, the government’s environmental attention positively impacts the green innovation of non-heavy-polluting firms. In addition, Fintech mitigates the negative effects of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation in the short term while enhancing the positive effect of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation in the long term for heavy polluting firms. Our article provides evidence and implications for environmental regulation in developing countries and urban areas.

1 Introduction

Over the past several decades, inappropriate human activities have been steadily increasing and influencing numerous climate extremes in every region of the world, according to the report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2021). To deal with the contradiction between economic development and environmental protection, governments worldwide have focused on environmental issues and engaged firms’ green production persistently (Zhang et al., 2011; Martín et al., 2020). Green innovation has long been recognized to be a critical factor in balancing economic growth and environmental sustainability. Several articles have examined the influencing factors of green innovation from the perspective of micro- and macro-level (Gollop and Robert, 1983; Amore and Bennedsen, 2016), particularly the effects of environmental regulations and related policies on green innovation (Porter and Linde, 1995; Zhang et al., 2011; Song et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2021). However, few of them investigated the impact of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation.

Initially, “attention” was a topic for psychologists. Jones (2010) introduced “attention” to government decision-making and proposed an attention-driven model for policy selection. He argues that decision-makers must differentiate the significance of information based on their attention and then make decisions accordingly, demonstrating that when policymakers’ attention shifts, government decisions follow suit. Due to the limited attention span of policymakers, when policymakers’ attention is focused on environmental protection, associated issues are more likely to be motivators behind the policy and related behavior (Wen and Du, 2018). Policy and institutional changes determine enterprise behavior (La Porta et al., 1998), particularly in a transitioning country like China, where firms are exposed to greater external uncertainty and must stay sensitive to changes in regulations to seize business opportunities. Therefore, changes in government regulations significantly impact the investment and financing behaviors of firms (Khanna and Rivkin, 2001; Liu et al., 2022). When the government focuses attention on environmental protection, businesses may anticipate potential institutional changes and alter behaviors accordingly. This allows us to explicitly link the government’s environmental attention to corporate green innovation.

Depending on the different mechanisms, the government’s environmental attention may promote or inhibit green innovation. Heavy polluters have a greater demand for emissions than non-heavy polluters and are, therefore, the primary targets of environmental regulation (Matthews and Denison, 1981; Gray, 1987). Moreover, polluting firms have a lot of pressure on green transition, which is essential to enhancing product competitiveness (Wong, 2012). Hence, most existing research on green innovation focuses on heavy polluting firms (Wu et al., 2018; Li and Xiao, 2020). Although non-heavy-polluting firms are not the primary targets of pollution control, this does not mean that non-heavy polluting firms will not engage in green innovation. For instance, firms in the industry like automobile manufacturing are not highly polluting; however, they can still optimize their production through environmentally responsible innovation. Existing research ignores the impact mechanism of green innovation on non-heavy-polluting firms. So, what are the differences between the impact of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation in heavy-polluting and non-heavy-polluting firms?

A related question is whether Fintech influences the relationship between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation. The existing literature provides evidence that Fintech increases the accessibility of financial services, alleviates financing constraints, and thereby boosts the green innovation of firms (Li et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2022). Yet, it remains unclear whether Fintech will affect the relationship between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation.

Using the data of A-share firms listed in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges in China from 2011 to 2019, combined with the dataset of the government’s environmental attention in 274 cities, we investigate the different impacts of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation of heavy-polluting and non-heavy-polluting firms. Additionally, we explore the moderating effect of Fintech on the relationship between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation. Moreover, we focus on the government’s environmental attention mechanism for green innovation through two channels: “crowding-out effect” and “innovation compensation.”

The following content is organized as follows: Section 2 provides the literature review. The theoretical framework and research hypotheses are presented in Section 3. Section 4 presents the methodology, and Section 5 describes the analysis of the empirical results. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the conclusions and implications.

2 Literature review

2.1 Attention and policy behavior

“Attention” was initially a topic of interest to psychologists, but it has become an essential concept in the disciplines of management and organizational behavior (Wang, 2013). Attention is “the process by which managers selectively focus on certain information and ignore others” (Simon, 1947). Attention allocation necessitates the rapid determination of what is urgent and essential within the limit of decision-makers’ cost constraints. Some researchers have investigated the economic effects of changes in managers’ and the public’s attention (Zheng et al., 2013; Liu and Wang, 2014). Jones (2010) introduced “attention” to government decision-making and proposed an attention-driven model for policy selection. He argues that decision-makers must prioritize the significance of information based on their attention and then make decisions accordingly, demonstrating that when policymakers’ attention shifts, government decisions follow suit.

Existing research has examined the measurement of government attention. Chen and Chen (2018) and Wen (2014) measure the government’s focus on innovation, entrepreneurship, and essential public services in China, respectively, using text analysis techniques on government work reports. Flavin and Franko (2017) use introduction data from state legislatures to measure government attention and discover that state legislators are less likely to act on an issue when it is prioritized by low-income citizens than by wealthy citizens. Some scholars assess the government’s environmental attention. Wang and Li (2017) analyze the government work reports in 30 Chinese provinces and cities between 2006 and 2015, using text analysis to examine the changes in the government’s attention to ecological and environmental issues. It has been discovered that the local government’s attention to ecological and environmental issues has gradually increased and that this attention is consistent with that of the central government.

A large strand of research has evaluated the effects of the government’s environmental attention on pertinent policies and administration. Using the cognitive dynamics theory of psychology, Wen and Du (2018) investigate the impact of changes in the central government’s environmental attention on government environmental policies and explain the process using “concept-motivation-guidance” logic. Wang and Wu (2021) examine the effect of government–public attention congruence on environmental governance and conclude that environmental governance is more effective when government and public attention are congruent. Shen et al. (2020) investigated the effect of government ecological attention on environmental governance performance in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region between 2005 and 2020, demonstrating that environmental protection attention is most effective at enhancing environmental governance performance. Huang et al. (2022) investigated the effects of the Chinese government’s environmental attention on ambient pollution. The results indicate that increasing the government’s environmental attention can reduce air pollution. When governments shift their attention from “pursuing GDP growth” to “green and low-carbon development,” they can significantly reduce carbon emissions, which can boost economic growth in the long run according to Hu and Wang (2022).

2.2 Influencing factors on green Innovation

Existing literature has examined the factors that contribute to green innovation. Some studies have investigated the micro-level factors of green innovation, such as firm-level environmental management (Li et al., 2019), corporate governance (Amore and Bennedsen, 2016), environmental perceptions of executives (Lin and Chen, 2017), financial constraints (Aghion et al., 2009), and stakeholder pressure (Song et al., 2020).

A portion of the literature investigates the macro-level factors that influence green innovation, focusing primarily on government environmental regulations and green innovation-related policies. Regarding the impact of environmental regulation on green innovation, some neoclassical economics theories propose that environmental regulation inhibits green innovation by increasing the cost of environmental compliance for firms (Gollop and Robert, 1983). It is primarily due to the “crowding-out effect” of environmental regulations on firms’ investments in green technological innovation due to rising compliance costs, production costs, and sewage costs (Matthews and Denison, 1981; Gray, 1987; Palmer et al., 1995; Bai et al., 2019). Nevertheless, several studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of environmental regulations on green innovation. According to Porter and Linde (1995), well-designed environmental regulations promote green innovation. By compelling or incentivizing firms to invest more in R&D to enhance their ability to reduce pollution and product technology content, regulations create innovation compensation and competitive advantage (Zhang and Vander, 1995; Jaffe and Palmer, 1997; Zhang et al., 2011; Jing and Zhang, 2014; Guo, 2018; Li et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2021).

Recent research indicates that the relationship between environmental regulation and green innovation is not linear but “U”-shaped in terms of inhibition or promotion. Zhang et al. (2011) contended that the “U”-shaped relationship between environmental regulation and green innovation is because the positive effects of “innovation compensation” and the negative effects of “compliance costs” are not synchronized, and the positive effects lag behind the negative ones. Thus, a “U”-shaped relationship exists between a given level of environmental regulation and technological innovation (Shen, 2012; Xie et al., 2017; Fan et al., 2020).

Several researchers have investigated the heterogeneity of environmental policies’ effects on green innovation. Some studies have demonstrated the significant effects of new environmental protection laws, the central environmental protection inspection system, and the environmental protection target responsibility system on corporate green innovation (Wang et al., 2020; Song et al., 2022). Some academics also believe that market-based environmental regulations, such as emission taxes, environmental protection taxes, and environmental subsidies, have a greater effect on fostering green innovation (Weitzman, 1974; Nordberg-Bohn, 1999; Requate, 2005; Cai and Li, 2018). Several articles have demonstrated that financial technology can enhance the accessibility of financial services, alleviate corporate financing constraints, optimize the precision and efficiency of external and internal capital allocation, and thereby promote corporate green innovation (Li et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2022).

Our article contributes to the literature by first exploring the effect of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation. Prior research has examined the impact of the government’s environmental attention on environmental protection policies (Wen and Du, 2018), the efficiency of environmental governance (Wang and Li, 2017; Wang and Wu, 2021), environmental investment, and carbon emissions (Zheng et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2022). Yet, few studies have examined the impact of the government’s environmental attention from the standpoint of green innovation. Second, this article investigates the different mechanisms of the impacts of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation of heavy polluting and non-heavy polluting firms. Since heavy polluters are the primary focus of environmental management, most existing green innovation studies have centered on these companies (Wu et al., 2018; Li and Xiao, 2020). However, the existing studies have disregarded the mechanism of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation in non-heavy polluting firms. Lastly, we further explore the moderating effect of Fintech on the relationship between the government’s environmental attention and firms’ green innovation. Although some scholars have investigated the impact of financial technology on firms’ green innovation (Li et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2022), the effect of Fintech on the relationship between the government’s environmental attention and firms’ green innovation has been overlooked.

3 Hypothesis development

A local government work report is a policy issued by the local government that typically includes a review and summary of the government’s work from the previous year, plans for the upcoming year, and resource allocation guidance. The report reveals “the focus of their work and where their resources flow.” Thus, the government’s work report is a significant indicator of the government’s attention allocation or shift (Wen, 2014; Wang and Li, 2017).

According to the psychological cognitive dynamics theory, changes in government attention primarily reflect changes in government cognition, which is a vital force driving behavior and a precondition for institutional and policy changes. Due to the limited attention span of policymakers, when their attention is on environmental protection issues, social issues related to environmental protection are more likely to shape policy motives and drive the related policy behaviors (Wen and Du, 2018). Policy changes affect the behavior of businesses and vice versa. Firms always pay close attention to institutional shifts to identify opportunities and adjust their development strategy, investment and financing behavior, and business decisions promptly to accommodate policy shifts (Zhou, 1999; Khanna and Rivkin, 2001). Therefore, businesses can anticipate possible policy and institutional changes and adapt their behavior accordingly when the government demonstrates a growing concern for environmental protection by releasing public information.

As the government pays more attention to the environment, policymakers allocate their limited attention to addressing environmental issues, and institutions or policies change accordingly. As a result, the government is more likely to implement stringent environmental policies, increase environmental legislation and enforcement, and increase pressure on businesses to control emissions and protect the environment (Wen and Du, 2018; Shen et al., 2021), such as by establishing energy conservation and emission reduction targets and increasing penalties for noncompliance. As a result, firms must purchase pollution-reducing equipment and incur operating expenses, in addition to paying higher taxes and environmental fines. It will undoubtedly increase the cost of sales and administrative expenses, reducing the firm’s free cash flow and tightening its financing constraints, resulting in a “crowding-out effect” on investment in technological innovation (Matthews and Denison, 1981; Gray, 1987; Bai et al., 2019). Moreover, to pursue short-term profits, businesses typically limit their investments in green innovations, which are characterized by lengthy cycles, high costs, and substantial unpredictability (Gollop and Robert, 1983). Therefore, increased government environmental attention may harm green innovation in the short term.

While the government’s environmental attention grows to a certain level, its positive impact on green innovation is felt over a longer period. First, with the increase of government’s environmental attention, governments are more likely to increase environmental regulation, and the market will be more inclined to resource-saving and environment-friendly green products under reasonable regulations. With the awareness of increased government environmental attention, companies will choose to optimize resource allocation, develop green technology and equipment, and improve production processes and organizational management to enhance the green technology of their products according to Porter’s theory (Porter and Linde, 1995). It will stimulate the “innovation compensation effect” of the company, resulting in environmental protection and performance growth, while companies without efficient green innovation are more vulnerable to being eliminated by the market (Zhang et al., 2011; Jing and Zhang, 2014). Second, with increased government environmental attention comes increased government financial budgets for environmental protection, such as increased financial allocations, environmental subsidies, green credit, and other local government-provided financial support for firms’ environmental protection projects (Wen and Du, 2018; Li and Chen, 2022). Support from environmental protection funds can promote firms’ green innovation, generate a “resource compensation effect,” direct firms’ green technology development, prompt firms to invest or purchase resources for green R&D activities, increase firms’ green innovation investment, and thereby promote firms’ green innovation (Yang et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019). Lastly, an increase in the government’s environmental attention indicates that the government is more inclined to provide resources and pays more attention to environmental issues. According to signaling theory, green innovation can assist businesses in obtaining a government-approved label, constructing a positive corporate image, and attracting more external resources to supplement themselves (Feldman and Kelley, 2006; Kleer, 2010). Therefore, the government’s increased focus on the environment can aid in increasing the level of green innovation among businesses.

When examining the effects of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation, there are significant differences between the mechanisms for heavy polluters and non-heavy polluters. Heavy polluters have a greater demand for waste disposal and are the primary focus of environmental governance. As environmental regulation improves, waste disposal consumes a greater portion of cash flow and reduces green innovation investment (Matthews and Denison, 1981; Gray, 1987). In addition, the increased government attention to the environment makes it harder for heavy polluters to obtain loans and then tightens financing restrictions (Ding et al., 2020). Therefore, the negative effect of the government’s increased environmental attention on green innovation is more significant in the short term for firms that heavily pollute. Nonetheless, as the government’s environmental attention grows, polluting firms have more pressure to green transition, which is the essential path to enhancing product competitiveness. When the “innovation compensation effect” is greater than the “crowding-out effect,” the government’s environmental attention will spur green innovation. However, since the two effects are not synchronized, the negative effect tends to occur in the short term, whereas the performance of green innovation takes longer to be compelled. Consequently, increased government environmental attention decreases green innovation in the short term but increases green innovation in the long term (Zhang et al., 2011).

Based on the analysis presented earlier, we propose hypothesis 1 (H1):

H1. : The influence of the government’s environmental attention on the green innovation of heavy polluting firms shows a U-shaped relationship.Since non-heavy polluting firms are not the primary focus of pollution control, increasing the government’s environmental attention does not significantly increase such environmental associated costs and expenses. Therefore, the negative effects of the increased government’s environmental attention on green innovation can be negligible for firms that do not heavily pollute. Nevertheless, it does not imply that non-heavy polluting firms will not implement green innovation. Although ecological protection and environmental management are not heavy polluters, they can still promote green production through green innovation. On the one hand, green innovation has become a strategy for some businesses to obtain policy resources. These firms prefer green innovation that is easier and quicker to achieve, allowing them to obtain more government subsidies or tax rebates by disclosing green patent information. On the other hand, with the increasing government’s environmental attention, the environmental awareness of both individuals, firms, and the government will be enhanced (Li and Zheng, 2016), and customers are more inclined to resource-saving and environment-friendly green products. Green innovation can not only meet customers’ needs and build a good reputation for the company but also improve product competitiveness and prevent environmental pollution (Kammerer, 2009; Li et al., 2015; Hou et al., 2021). With the growth of the government’s environmental attention, non-heavy polluting firms foresee the business opportunities brought by green production and then perform green innovation. Therefore, the increase in the government’s environmental attention has positively impacted the green innovation of non-heavy polluting firms.Based on the analysis presented earlier, we propose hypothesis 2 (H2):

H2. : The government’s environmental attention is positively associated with green innovation in non-heavy-polluting firms.Financial technology can enhance the availability of regional financial services, alleviate the financing constraints of firms, and direct the precise flow of funds, thereby optimizing the precision and efficacy of external and internal capital allocation (Tan et al., 2022). Green innovation activities are characterized by high costs, lengthy timelines, and high levels of uncertainty. Thus, green innovation activities require greater financial support than others (Gollop and Robert, 1983). Suppose the enterprise’s location city has a high level of financial technology. In that case, it can effectively reduce information asymmetry, alleviate resource mismatch (Tian et al., 2017), and provide financial support for the R&D of heavy polluters who need to implement green innovation. This advanced level of financial technology will mitigate the short-term negative effects of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation. In the long term, it improves the efficiency of resource allocation, creates a favorable external financial environment, and aids heavy polluters in achieving the “innovation compensation effect” (Tan et al., 2022). Thus, a high level of financial technology augments the positive impact of the government’s environmental attention on the green innovation of heavy polluters.Based on the analysis presented earlier, we propose hypothesis 3 (H3):

H3. : Increased financial technology can mitigate the negative effects of the government’s environmental attention on the green innovation of heavy polluting firms in the short term while enhancing the positive effect of the government’s environmental attention on the green innovation of heavy polluting firms in the long term.

4 Methodology

4.1 Sample and data collection

In this article, we use the data of A-share companies listed in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2011 to 2019 and filter samples as follows: 1) exclude the samples that were ST, *ST, PT, and delisted during the sample period; 2) exclude the samples of financial companies; 3) exclude the samples with missing variables. Finally, we obtained 18,390 observed samples and performed tailing at the 1% and 99% levels for continuous variables. The other main variables are defined and measured as follows.

4.2 Measurement

4.2.1 Green innovation

The data on green innovation were obtained from the National Intellectual Property Patent Database of China. According to Song et al. (2020), we collected the patent information of the sample firms from 2011 to 2019 and matched them with the Green List of International Patent Classification, which was published by the World Intellectual Property Organization. Since patent application data are more stable than the number of patents granted, and the year of patent application could better reflect the actual innovation time than the year of patent grant, we use the total number of green patent applications (GITotal) to measure the green innovation of firms. Furthermore, according to the type of green patents, we classify green patents into green invention patents (GreIv) and green utility model patents (GreUm). Meanwhile, to make the sample more consistent with the assumption of normal distribution, we use the natural logarithm of the number of green patent applications plus one to measure corporate green innovation, following Tan et al. (2022). In addition, green innovation has a time lag caused by research and development, so we use t+1 period green innovation data as the dependent variable.

4.2.2 Government’s environmental attention

To measure the government’s environmental attention (GEA), we use text analysis to obtain the frequency of environmental keywords used in government work reports, and the number of relevant words reflects the degree of attention given to a public issue by decision-makers (Wang and Li, 2017; Huang et al., 2022). The more frequently the words appear, the more attention the government pays to the issue. To ensure the completeness and continuity of the textual data, we first collected 274 city-level government work reports from 2011 to 2019, all of which were obtained from the official government websites. Second, we read 15 reports from different regions and years intensively to extract keywords related to environmental protection and sorted them by frequency (Shen et al., 2020). Then, we selected the top 15 keywords (Wang and Li, 2017), which were low carbon, environmental protection, air quality, green, PM2.5, COD, CO2, PM10, ecology, emission, emission reduction, pollution, environmental protection, sulfur dioxide, and energy consumption. Third, we used software to sort the government work report documents word by word and count the frequency of the abovementioned keywords. Finally, considering the influence of text length on the frequency of keywords, we standardized the index by dividing the frequency of keywords by the total number of words in the text and then multiplying by 100 to get the government’s environmental attention (Huang et al., 2022).

4.2.3 The mediating variables

In order to measure the level of financial technology (Fintech) where the company is located, we used the number of companies in the finance and high-technology industries in the city to measure Fintech according to Tan et al. (2022). We obtained the number of companies that is financial and technological which were currently in existence and had been operating for 2 years through the advanced search function of the “Enterprise Search” website. Furthermore, considering Fintech is influenced by the level of local economic development, we adjusted the indicator by dividing the number of Fintech companies by the regional GDP.

4.2.4 The control variables

According to the related study by Lin et al. (2014), we control for the following variables (controls) in the model: firm size (size), the natural logarithm of the firm’s total assets; firm age (age), firm’s establishment time; leverage (Lev), the ratio of total liabilities to total assets; return of Asset (Roa), the ratio of net profit to average total assets; firm value (TobinQ), the sum of the market value of owner’s equity and liabilities to total book assets; revenue growth (growth), the percentage of revenue growth; independent directors (Indep), the percentage of independent directors to board members; cash flow from operating activities (cashflow). As the level of economic development of the city may affect the firm’s innovation capability, we control the city-level GDP (Lngdp), and we also control for year fixed effects (year), industry fixed effects (industry), and city fixed effects (city) in the model. All financial data of listed companies are obtained from the Wind database, and data on economic indicators at the city level are obtained from the China City Statistical Yearbooks.

4.3 Model

Based on the previous assumptions and variable settings, our benchmark regression model is set as follows:

where α and β are the coefficients of variables, i and t denote the enterprise and year, respectively, and GIi,t+1 denotes the green innovation level of enterprise i in the next period, which is measured by three indicators: total number of green patent applications (GITotal), green invention patents (GreIv), and green utility model patents (GreUm), respectively; GEAit denotes the primary term of the government’s environmental attention in the city where enterprise i is located in year t; GEAit2 denotes the secondary term of the government’s environmental attention; Fintech denotes the level of financial technology in the city in the model (2); Controlsit denotes all control variables, and εit is the random error term.

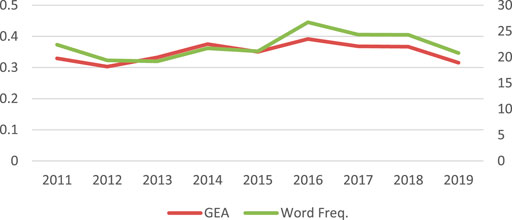

4.4 Statistics

Figure 1 shows the mean values of the government’s environmental attention and the environment-related word frequency in 274 cities in China from 2011 to 2019. The figure shows that the average GEA was falling from 0.33% to 0.30% during 2011–2012 and then raised to 0.37% in 2014. After that, it experienced volatile falling to 0.35% and rising to 0.39%, with 2 years stabled at 0.37% and then fell to 0.32% in 2019. This indicates that although local governments were aware of the importance of environmental governance and have begun to focus on environmental protection issues, the growth of government’s environmental attention is volatile and weak in sustainability, and local governments need to improve their environmental attention continuously.

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the variables in this article. The mean and median of GITotal are 0.299 and 0, respectively, which means the data have serious right skewness, the green innovations of the firms are highly differentiated, and the overall innovation level is low. Compared with the number of GreUm, the mean and standard deviation of the number of GreIv are larger, which indicates that firms are more positive to carry out green invention patents, but the differences in performance among individuals are more obvious. The mean and Std. of GEA are 0.357% and 0.128, respectively, which means the differentiation of the government’s environmental attention among cities is not huge.

5 Empirical results

5.1 Benchmark regression

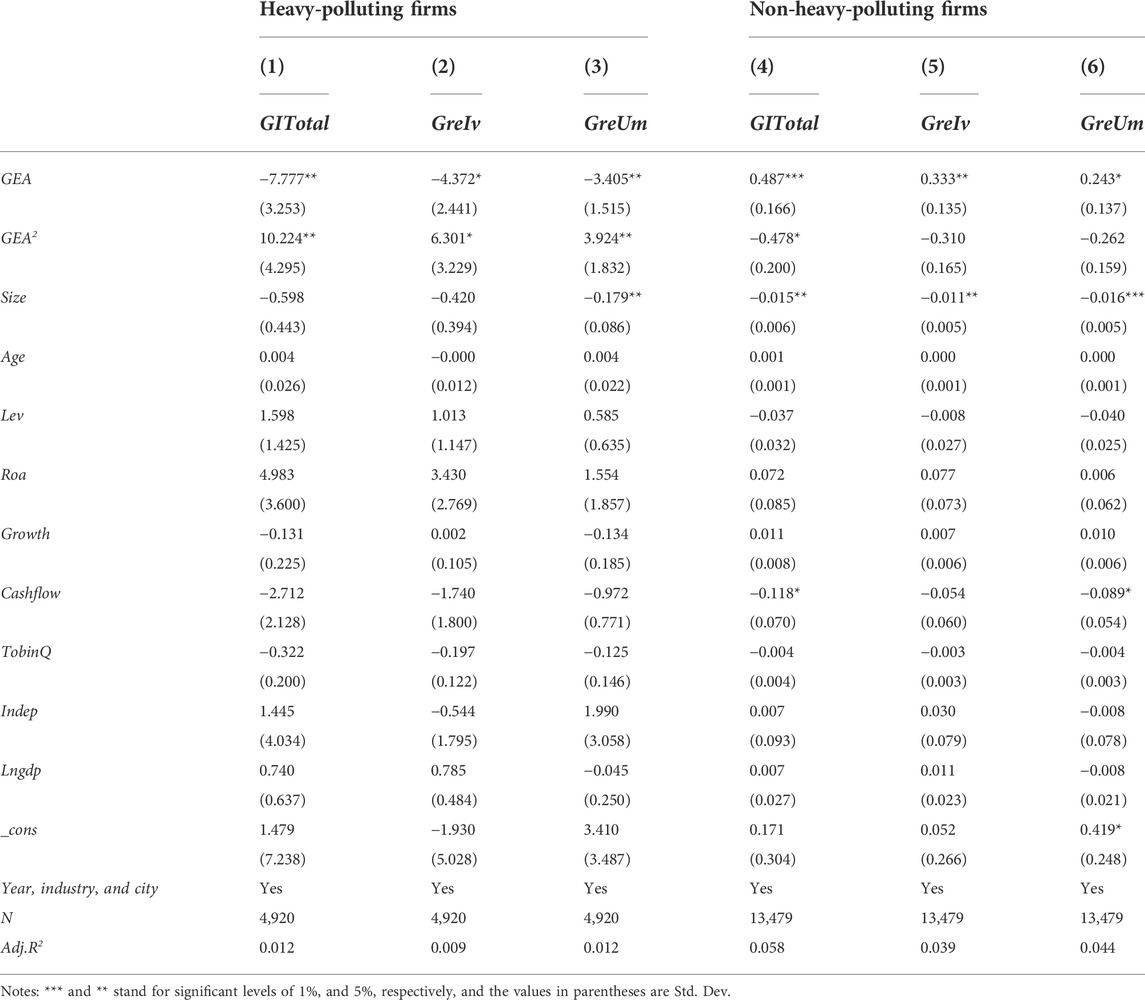

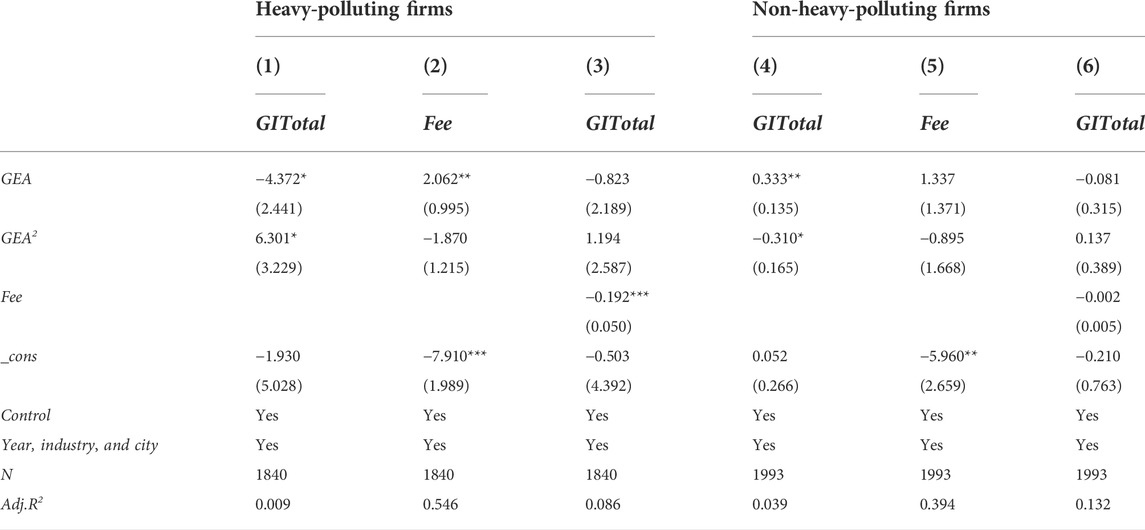

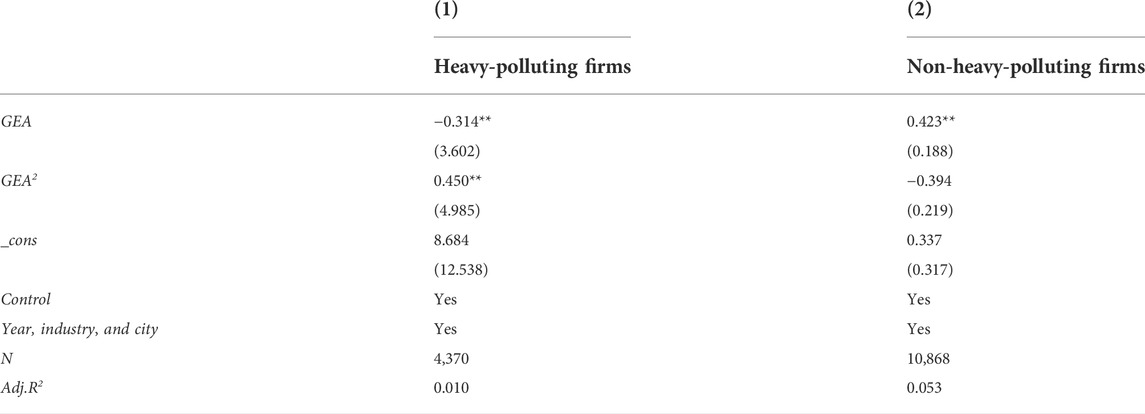

As in the previous analysis, the mechanisms of the government’s environmental attention to green innovation are different between heavy polluting and non-heavy polluting firms. Hence, we divided the sample into heavy polluting and non-heavy polluting groups according to the Guidelines on Environmental Information Disclosure of Listed Companies issued by the Shanghai Stock Exchange. Table 2 reports the results of the benchmark regressions of the impact of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation for heavy polluting and non-heavy polluting firms, respectively.

Columns (1) to (3) show the results for the sample of heavy polluting firms. The signs of the coefficients of GEA and GEA2 are negative and positive, respectively, and are both significant at least at the 10% level, which demonstrates that as the government’s environmental attention shifts from weak to strong, the impact it has on heavy polluters’ green innovation will change from negative to positive. Therefore, the relationship between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation is consistent with the “U”-shape, which can prove hypothesis H1. The results are significant in GITotal, GreIv, and GreUm, and the inflection points are 0.377, 0.343, and 0.432, respectively. The mean value of the existing government’s environmental attention data is 0.357, which indicates that the government’s environmental attention has started to promote green invention patents for heavy polluting firms, but the influence on the total number of green patents and green utility model patents has not reached the inflection point.

Columns (4) to (6) show the regression results for the sample of non-heavy polluters. The coefficients of government’s environmental attention are 0.487, 0.333, and 0.243, respectively, and all of them are positively significant at a level of at least 10%, which indicates that the government’s environmental attention has a positive effect on green innovation of non-heavy-polluting firms, and the impact is greater on green invention patents than on green utility model patents. The results indicate that the motivation of innovation for non-heavy-polluting firms is not only to strategically release “green signals” but also to foresee the business opportunities brought by green production. The results mentioned earlier are consistent with hypothesis H2.

It is worth noting that the regression coefficients of GEA2 for non-heavy polluters are negative, but only the result of GITotal is significant in statistics, which means the regression result is not robust. The results demonstrate that the positive effect of GEA on green innovation gradually decreases with the increase in the government’s environmental attention to non-heavy polluting firms, but the results are not robust to an inverted U-shaped trend. The possible explanation is that one of the purposes of green innovation for non-heavy polluting firms is to release green signals and obtain government resources, and when green innovation reaches the standard of obtaining government resources, the incentive for green innovation decreases (Zhu et al., 2022). Meanwhile, with the improvement of resource allocation efficiency, government resources will be allocated to firms with more green production needs, so when the government’s environmental attention reaches a certain level, its positive effect on green innovation for non-heavy polluting firms diminishes.

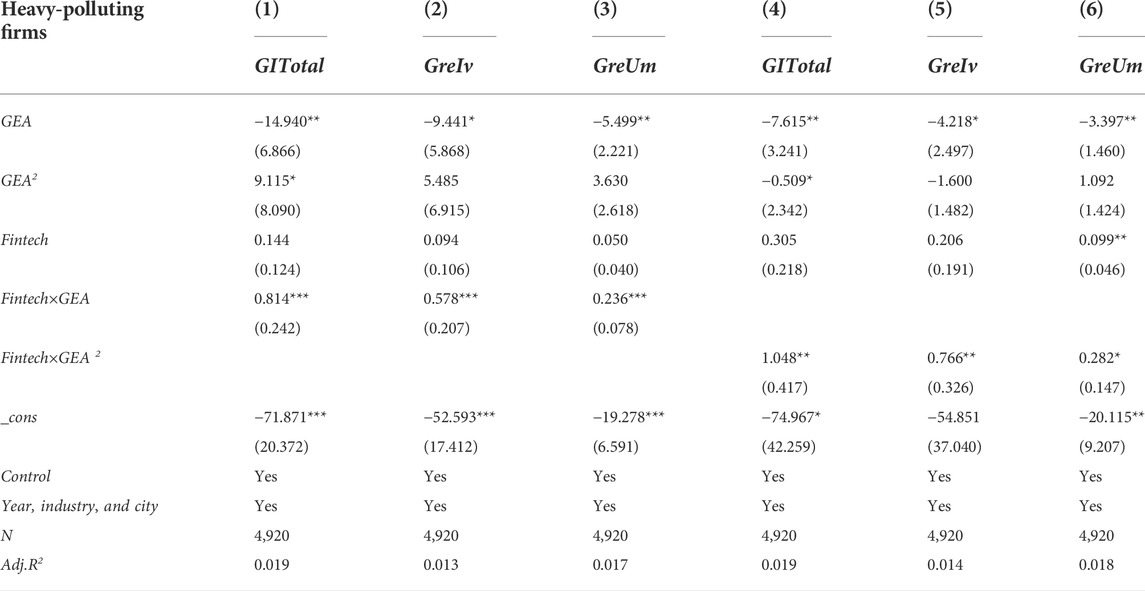

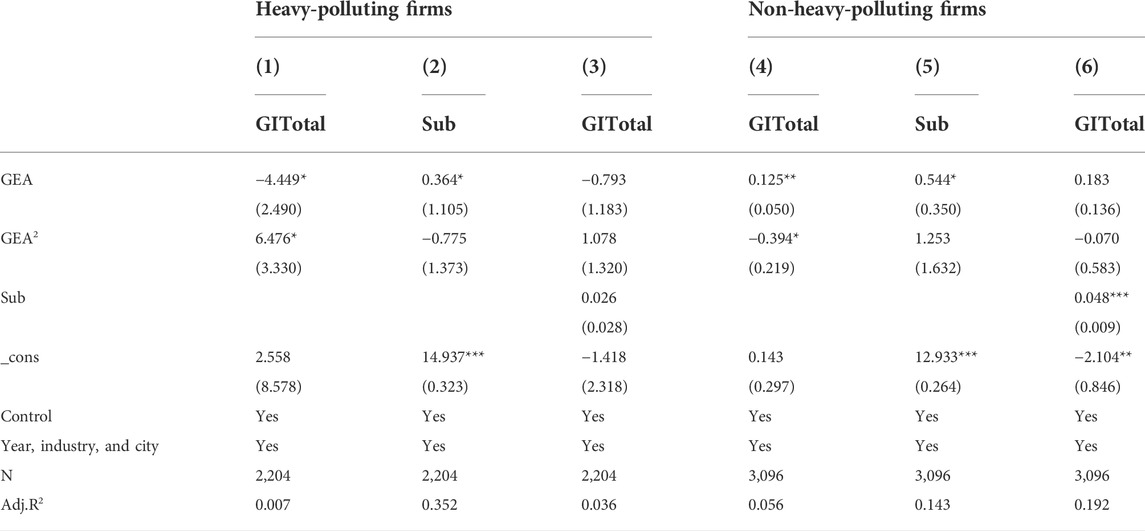

5.2 Mediating effects

Table 3 shows the regression results that added the interaction terms of financial technology level (Fintech), GEA, and GEA2, respectively, in heavy-polluting firms. As the inclusion of interaction terms has serious multicollinearity problems that affect the regression results, therefore, we follow Su and Zhou (2019) to add the interaction terms separately. Focusing on the regression coefficients and significance levels of the interaction term Fintech×GEA, we find that the coefficients of the interaction term are significantly positive at the 1% level, and the coefficients are 0.814, 0.578, and 0.236, respectively. The results indicate that the increase of financial technology weakens the impact of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation before the extreme value, which means that the increase of Fintech can mitigate the negative relationship between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation in the short term.

In columns (4) to (6), we added the interaction term Fintech×GEA2, and the results show that the regression coefficients of the interaction terms are significantly positive at the 10% level at least, indicating that after GEA reaches its extreme value, the positive relationship between government’s environmental attention and green innovation is enhanced by the increase of financial technology. The abovementioned results are consistent with hypothesis H3.

It should be noted that the moderating effect of Fintech on the sample of non-heavy polluting firms is not significant, which may be due to the development of Fintech improving the precision and effectiveness of green capital, alleviating resource mismatch (Tian et al., 2017), and providing financial support for heavy polluting firms which urgent to pursuit green innovation. Therefore, Fintech does not significantly increase the positive effect of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation in non-heavy polluting firms. The hypothesis H3 is only proved in heavy-polluting firms, and the regression results for non-heavy-polluting firms are not reported here due to space constraints.

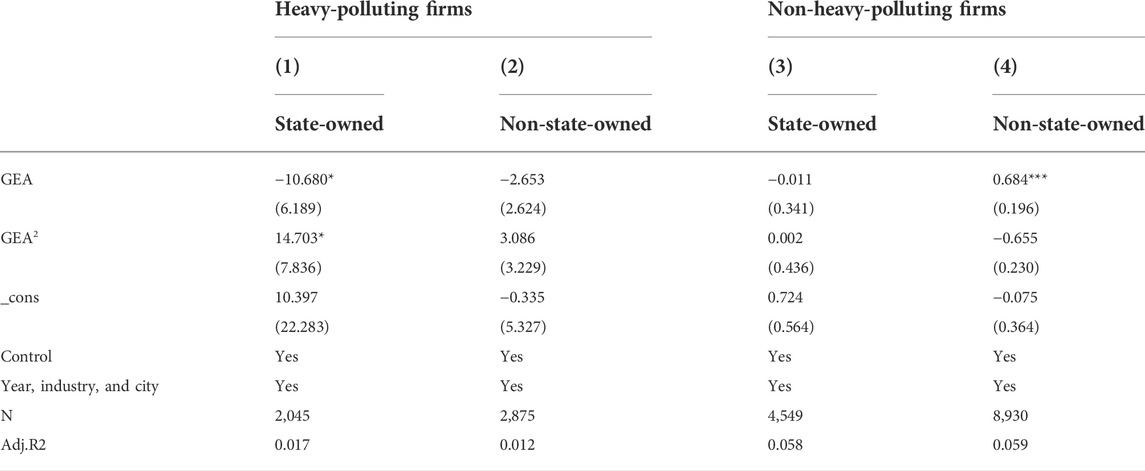

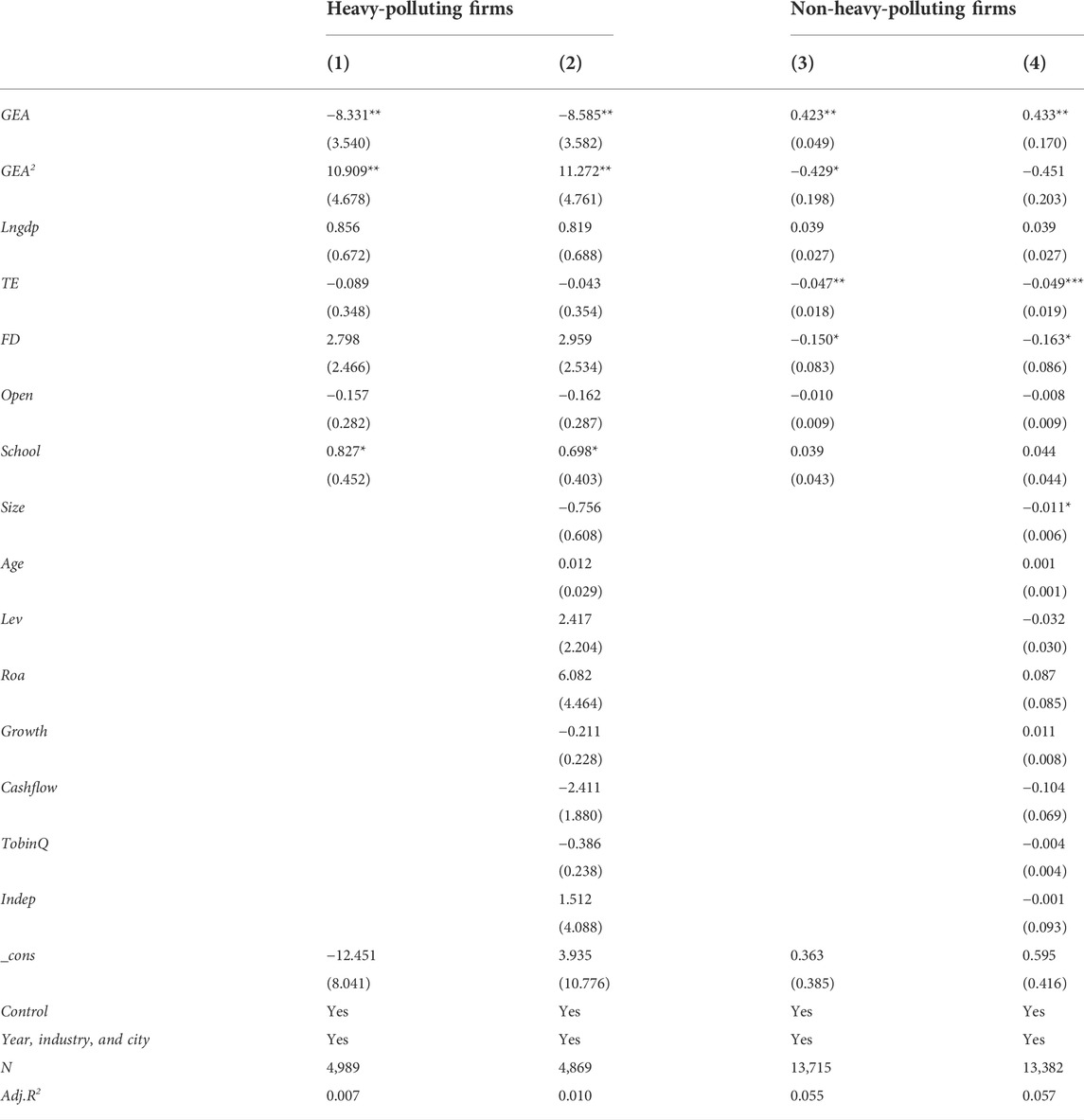

5.3 Heterogeneity effect

In the heterogeneity test, we further divided the firms into state-owned and non-state-owned groups according to the nature of equity. There are significant differences between state-owned and non-state-owned firms in terms of resource access, response to government policies, financing capacity, and relationship with the government (Zhang et al., 2022). We focused on whether the nature of equity affects the relationship between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation. Table 4 reports the regression results of the government’s environmental attention (GEA) on the total green innovation (GITotal) of heavy polluters and non-heavy polluters, respectively.

The regression results are reported in columns (1) to (2) for the grouping of heavy polluters by the nature of equity. The results show that the coefficients of GEA and GEA2 are significantly negative and positive, respectively, in the group of state-owned firms, but the coefficient of GEA is not significant for non-state-owned firms. One possible explanation is that state-owned firms reflect government regulations more effectively and enforce the regulations more strictly than non-state-owned, and state-owned firms generally have more obvious economies of scale and bear a stronger risk of innovation failure than non-state owned. Hence, the effect of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation in state-owned firms is more significant in the grouping of heavy polluters.

Columns (3) to (4) report the regression results for non-heavy polluting firms by the nature of equity, the results show that the coefficient of GEA is significantly positive in the group of non-state firms, but the coefficient of GEA is not significant for state-owned firms. Since green innovation is not an inevitable choice for non-heavy-polluting firms and non-state firms face stronger financing constraints, therefore, with the increase in government’s environmental attention, non-state-owned firms are more motivated to conduct green innovation for the signal of government recognition to receive government subsidies, tax rebates, and other government resources (Feldman and Kelley, 2006; Kleer, 2010). Hence, the government’s environmental attention has a more significant impact on green innovation in non-state firms for non-heavy-polluting firms.

5.4 Mechanism

5.4.1 Channel of “crowding-out effect”

According to the previous theoretical analysis, the “crowding-out effect” and the “resource compensation effect” are the two main channels for the government’s environmental attention to affect green innovation. The rise in the government’s environmental attention increases the production costs and the associated costs of sewage to control pollution, which in turn decreases crowding-out investment in green innovation. Herein, we use the environmental related expenses to measure the “crowding-out effect.” The variable fees in table 5 are the total environmental related expenses such as sewage charges, cleaning fees, and environmental protection inputs of the enterprise are taken as logarithms (Lu et al., 2019). Table 5 reports the regression results of the environmental related expenses as a mediating variable for heavy polluting firms and non-heavy polluting firms, respectively.

Columns (1) to (3) report the regression results for the group of heavy polluting firms. The result shows that the coefficient of GEA in column (2) is 2.062 with a significant positive sign, which means that the rise in the government’s environmental attention significantly increases environmental related expenses. The coefficient of fee in column (3) is −0.192, which is significant at the 1% level, indicating that the rise in the government’s environmental attention significantly increases the environmental related expenses of heavy polluters, which in turn crowds out innovation inputs and inhibits green innovation. Since the regression coefficients of GEA and GEA2 are not significant, the financing constraint plays a full mediating effect. Columns (4) to (6) report the regression results for the sample of non-heavy polluters. We find that the increase in the government’s environmental attention does not significantly affect environmental related expenses for non-heavy polluters. Therefore, the environmental related expenses are not the mechanism of influence between the government’s environmental attention and the green innovation of non-heavy-polluting firms, which is also consistent with the previous theory.

5.4.2 Channel of “resource compensation effect”

The rise of the government’s environmental attention increases the government’s financial investment in environmental protection, which has a “resource compensation effect” on firms’ green innovation and thus promotes green innovation. We use the logarithm of the number of environmental subsidies to measure the government’s “resource compensation effect” (Yang et al., 2017). Table 6 reports the results of the test of environmental subsidies as mediating variables for heavy polluters and non-heavy polluters, respectively.

Columns (1) to (3) report the regression results for the group of heavy polluting firms. The result shows that the coefficient of GEA in column (2) is 0.364 with a significant positive sign, indicating that the increase in the government’s environmental attention significantly increases the environmental subsidies of heavy polluting firms. The results of GEA and Sub in column (3), however, are not significant, indicating that the increase in environmental subsidies is not an effective mediating variable for the increase of green innovation in heavy polluting firms. The reason is that government environmental subsidies make the heavy polluting firms financially dependent, and the subsidies are more likely to be used to maintain survival rather than innovation (Xu and Li, 2019); therefore, environmental subsidies cannot significantly increase the green innovation of the heavy polluting firms.

Columns (4) to (6) report the regression results of the non-heavy polluters. In column (5), we find that the rise of the government’s environmental attention significantly increases environmental subsidies with a coefficient of 0.544. In column (6), environmental subsidies have a significant positive effect on green innovation, which means that the government’s environmental attention can improve environmental subsidies which causes the increase of green innovation in non-heavy-polluting firms. Since the results of GEA are not significant, environmental subsidies play a full mediating effect, which is consistent with the theoretical derivation described earlier in this article.

5.5 Robustness test

5.5.1 Endogeneity problem

Although the benchmarking regression verifies our previous hypothesis, further research shows that there may be a causal endogeneity between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation. When local firms have more green innovation achievements, the officers may emphasize environmental related results in government work reports to highlight the government’s performance, which results in higher government environmental attention.

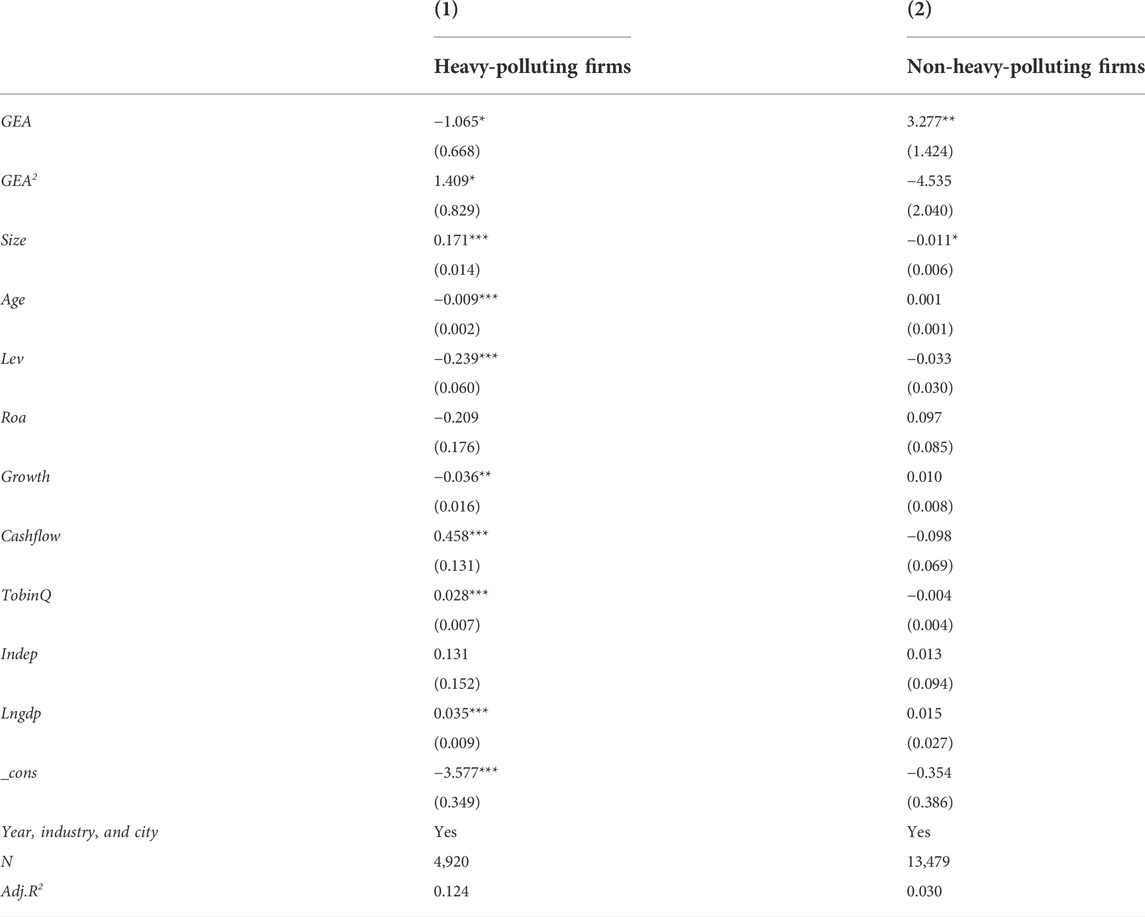

To solve the endogeneity problem, we use the 2SLS instrumental variables approach for further testing. We choose the one-period lagged government’s environmental attention primary term L.GEA and the one-period lagged government environmental attention secondary term L.GEA2 as the instrumental variables for GEA and GEA2, which is a common practice since the endogenous variables with one lag period can meet the correlation assumption and the exogenous assumption of effective instrumental variables (Huang et al., 2022). The first-stage regression results also confirm the significant positive correlation between L.GEA2 and GEA2 as well as L.GEA and GEA.

Table 7 mainly reports the second-stage regression results in the 2SLS regression of government environmental attention (GEA) and green innovation (GITotal) for heavy polluters and non-heavy polluters, respectively. We notice that after controlling for endogeneity, the results of the GEA and GEA2 of heavy polluters still significantly support the hypothesis of a U-shaped curve, but the coefficient decreases to 1.065, and the significance drops to 10%. As for the non-heavy polluters, the regression coefficient of GEA is still significantly positive, and the coefficient increases to 3.277. The coefficient of GEA2 is still negative but not statistically significant. Therefore, after controlling for endogeneity, the regression results still support the hypothesis of this article.

5.5.2 Alternative control variable

In the robustness test, we try to replace and add control variables. Most of the existing literature on corporate green innovation controls for city-level macroeconomic variables and the control variables selected in this article are mainly corporate financial data. Therefore, to further test the robustness of the regression results, we chose to replace the control variables with macro control variables as follows (Zhu et al., 2022): (1) the level of science and technology expenditure (TE), measured by the logarithm of the share of general public budget expenditure on science and technology; fiscal decentralization (FD), the logarithm of the ratio of fiscal revenues to fiscal expenditures; regional openness (Open), measured by the logarithm of the actual amount of foreign capital used in the region; the number of higher education institutions (schools), the logarithm of the number of general higher education institutions in the city. Table 8 reports the regression results of government environmental attention (GEA) and green innovation (GITotal) for heavy and non-heavy polluters after replacing or adding macro control variables. The coefficients’ symbols and significance of the test are generally consistent with the results in the benchmarking regression, which further supports our previous conclusions.

5.5.3 Sample excluding favorable environment cities

In a further robustness test, we exclude samples that are located in the cities of Qingdao, Yantai, Lishui, Taizhou, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Huizhou, Zhongshan, Guiyang, Haikou, and Kunming, which have a relatively favorable environment (Zhu et al., 2022), because cities with the relatively favorable environment may have less pressure on environmental governance. Table 9 shows the regression results of government environmental attention (GEA) and green innovation (GITotal) for heavy polluters and non-heavy polluters after removing the samples. The coefficients’ symbols and significance of the robustness test are generally consistent with the results in the benchmarking regression, which further supports our previous conclusions.

6 Conclusion and policy recommendations

6.1 Conclusion

This article examines the influence and differential influence mechanism of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation in heavy-polluting and non-heavy-polluting firms, using data of Chinese A-shares listed companies in Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2011 to 2019. It also investigates the moderating effect of financial technology on the relationship between government environmental attention and green innovation. The following are the conclusions:

(1) There is a distinction between heavy polluting and non-heavy polluting firms concerning the effect of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation. Using OLS regression models, the 2SLS instrumental method, and other robustness tests, we demonstrate that as the government’s environmental attention shifts from weak to strong, its impact on heavy polluters’ green innovation will shift from negative to positive. “U”-shape is the relationship between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation. In the meantime, the government’s environmental attention positively impacts the green innovation of non-heavy polluting firms, with a greater impact on green invention patents than on green utility model patents.

(2) As for the mediating effects of Fintech, the regression results indicate that an increase in Fintech can mitigate the negative relationship of heavy polluters between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation in the short term. Moreover, after the government’s environmental attention reaches its extreme value, an increase in Fintech strengthens the positive relationship between the government’s environmental attention and green innovation. However, Fintech’s moderating effect on the non-heavy-polluting group is insignificant.

(3) According to the heterogeneity test, the effect of the government’s environmental attention on green innovation in state-owned firms is greater than in non-state-owned firms in the grouping of heavy polluters. In contrast, the government’s environmental attention significantly impacts green innovation in non-state firms by grouping non-heavy polluters.

(4) The “crowding-out effect” channel plays a mediating role in heavy polluters. Results indicate that an increase in the government’s environmental attention significantly increases environmental related expenses, which, in turn, crowds out innovation inputs and impedes green innovation among heavy polluters. On the other hand, the “resource compensation effect” channels have a moderating effect on non-heavy polluters since the government’s environmental attention can increase environmental subsidies, which in turn increases green innovation in non-heavy-polluting firms.

6.2 Policy recommendations

Based on our findings, we propose the following recommendations and wish to provide developing or transitioning nations and regions with experience. To improve the green innovation of firms, the government must first increase its attention to environmental protection in a sustainable manner. Before the inflection point, they should pay attention to the negative impact on heavy polluters and make efforts to alleviate their financing constraints. If the government’s environmental attention fluctuates too much over a short period, it may threaten the viability of green innovation. Second, enhancing the government’s environmental attention is advantageous for the green innovation of non-heavy polluting firms, which are also crucial R&D firms for green innovation. Therefore, the government should pay greater attention to the green innovation of non-heavy-polluting firms and implement continuous stimulation policies to sustain the innovation zeal of non-heavy-polluting firms. Lastly, the government should actively improve the level of regional financial technology, which is conducive to enhancing the allocation efficiency of funds, reducing the inhibiting effect of the government’s environmental attention enhancement on the green innovation of heavy pollution firms in the short term, and enhancing the promotion effect on green innovation in the long term.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, JC and QL; methodology, JC; software, JC; formal analysis: JC and QL; writing—original draft preparation, JC; writing—review and editing, QL and XW; visualization, XW.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Program (72102153 and 71902165).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aghion, P., Veugelers, R., and Serre, C. (2009). Cold start for the green innovation machine. Bruegel Policy Contrib.

Amore, M. D., and Bennedsen, M. (2016). Corporate governance and green innovation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 75, 54–72. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2015.11.003

Bai, Y., Song, S. Y., Jiao, J. L., and Yang, R. (2019). The impacts of government R&D subsidies on green innovation: Evidence from Chinese energy-intensive firms. J. Clean. Prod. 233, 819–829. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.107

Cai, W., and Li, G. (2018). The drivers of eco-innovation and its impact on performance: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 176 (8), 110–118. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.109

Chen, S. Y., and Chen, D. K. (2018). Air pollution, government regulations and high-quality economic development[J]. Econ. Res. J. 53 (02), 20–34.

Ding, N., Ren, Y. N., and Zuo, Y. (2020). Do the losses of the Green─credit policy outweigh the gains? A PSM-DID cost-efficiency analysis based on resource allocation[J]. J. Financial Res. 04, 112–130.

Fan, F., Lian, H., Liu, X., and Wang, X. (2020). Can environmental regulation promote urban green innovation efficiency? An empirical study based on Chinese cities[J]. J. Clean. Prod. 287 (1).

Fang, Z. M., Kong, X. R., Sensoy, A., Cui, X., and Cheng, F. (2021). Government’s awareness of environmental protection and corporate green innovation: A natural experiment from the new environmental protection law in China. Econ. Analysis Policy 70, 294–312. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2021.03.003

Feldman, M. P., and Kelley, M. R. (2006). The ex-ante assessment of knowledge spillovers: Government R&D policy, economic incentives and private firm behavior. Res. Policy 35, 1509–1521. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2006.09.019

Flavin, P., and Franko, W. W. (2017). Governments unequal attentiveness to citizens political priorities. Policy Stud. J. 45 (4), 659–687. doi:10.1111/psj.12184

Gollop, F. M., and Robert, M. J. (1983). Environmental regulations and productivity growth: The case of fossil-fueled electric power generation. J. Political Econ. 91 (4), 654–674. doi:10.1086/261170

Gray, W. B. (1987). The cost of regulation: OSHA, EPA and the productivity slow down. Am. Econ. Rev. 77 (77), 998–1006. doi:10.1016/0038-0121(88)90025-0

Guo, J., Li, K., Jin, L., Xu, R., Miao, K., Yang, F., et al. (2018). A simple and cost-effective method for screening of CRISPR/Cas9-induced homozygous/biallelic mutants. Plant Methods 28 (05), 40–48. doi:10.1186/s13007-018-0305-8

Hou, Y. H., Li, S. S., Hao, M., and Rao, W. Z. (2021). Influence of market green pressure on the green innovation behavior of knowledge-based enterprises. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 31 (1), 100–110.

Hu, J. K., and Wang, Y. M. (2022). The transformation of local government competition mode and carbon emission Performance─Empirical evidence from working reports of municipal. Gov. Econ. 06, 78–87. doi:10.16158/j.cnki.51-1312/f.2022.06.004

Huang, S., Ding, Y., and Failler, P. (2022). Does the government’s environmental attention affect ambient pollution? Empirical research on Chinese cities. Sustainability 14, 3242. doi:10.3390/su14063242

Huang, Z. H., Liao, G. K., and Li, Z. H. (2019). Loaning scale and government subsidy for promoting green innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 144, 148–156. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2019.04.023

IPCC (2021). Climate change 2021 the physical science basis working group I contribution to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental Panel on climate change. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/.

Jaffe, A. B., and Palmer, K. L. (1997). Environmental regulation and innovation: A Panel data study. Rev. Econ. Stat. 4, 610–619. doi:10.1162/003465397557196

Jing, W. M., and Zhang, L. (2014). Environmental regulation, economic opening and China’s industrial green technology progress[J]. Econ. Res. J. 49 (09), 34–47.

Jones, B. D. (2010). Reconceiving Decision-making in Democratic Politics Attention, Choice, and Public Policy. Beijing: Peking University Press, 58.

Kammerer, D. (2009). The effects of customer benefit and regulation on environmental product innovation: Empirical evidence from appliance manufacturers in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 68 (8/9), 2285–2295. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.02.016

Khanna, T., and Rivkin, J. W. (2001). Estimating the performance effects of business groups in emerging markets. Strategic Manag. J. 22 (1), 45–47. doi:10.1002/1097-0266(200101)22:1<45::AID-SMJ147>3.0.CO;2-F

Kleer, R. (2010). Government R&D subsidies as a signal for private investors. Res. Policy 39, 1361–1374. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.08.001

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R. (1998). Law and finance. J. Political Econ. 106, 1113–1155. doi:10.1086/250042

Li, C. T., Yan, X. W., Song, M., and Yang, W. (2020). Fintech and corporate Innovation─Evidence from Chinese NEEQ-listed companies[J]. China Ind. Econ. 01, 81–98. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2020.01.006

Li, D. Y., Huang, M., Ren, S. G., Chen, X. H., and Ning, L. T. (2018). Environmental legitimacy, green innovation, and corporate carbon disclosure: Evidence from CDP China 100. J. Bus. Ethics 150 (4), 1089–1104. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3187-6

Li, D. Y., Tang, F., and Jiang, J. L. (2019). Does environmental management system foster corporate green innovation? The moderating effect of environmental regulation. Technol. Analysis Strategic Manag. 31 (10), 1242–1256. doi:10.1080/09537325.2019.1602259

Li, Q. Y., and Xiao, Z. H. (2020). Heterogeneous environmental regulation tools and green innovation incentives: Evidence from green patents of listed companies[J]. Econ. Res. J. 55 (09), 192–208.

Li, R., and Chen, Y. (2022). The influence of a green credit policy on the transformation and upgrading of heavily polluting enterprises: A diversification perspective. Econ. Analysis Policy 74, 539–552. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2022.03.009

Li, S., Jayaraman, V., Paulraj, A., and Shang, K. c. (2015). Proactive environmental strategies and performance: Role of green supply chain processes and green product design in the Chinese high-tech industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 54 (7), 2136–2151. doi:10.1080/00207543.2015.1111532

Li, W. J., and Zheng, M. N. (2016). Is it substantive innovation or strategic Innovation?─Impact of macroeconomic policies on micro-enterprises’ innovation[J]. Econ. Res. J. 51 (04), 60–73.

Lin, H., Zeng, S. X., Ma, H. Y., Qi, G., and Tam, V. W. (2014). Can political capital drive corporate green innovation? Lessens from China. J. Clean. Prod. 64 (2), 63–72. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.046

Lin, Y. H., and Chen, Y. S. (2017). Determinants of green competitive advantage: The roles of green knowledge sharing, green dynamic capabilities and green service innovation. Qual. Quant. 51 (4), 1663–1685. doi:10.1007/s11135-016-0358-6

Liu, H. Y., Jiang, J., Xue, R., Meng, X., and Hu, S. (2022). Corporate environmental governance scheme and investment efficiency over the course of COVID-19. Finance Res. Lett. 47, 102726. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2022.102726

Liu, J. J., and Wang, W. X. (2014). Research on managerial attention: A state of the art review[J]. J. Zhejiang Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 44 (02), 78–87.

Lu, H. Y., Liu, Q. M., Xu, X. X., and Yang, N. N. (2019). Can environmental protection tax achieve ‘reducing pollution’ and ‘economic growth. [J]. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 29 (6), 130–137.

Martín, C. G., Amores-Salvadó, J., Navas-López, J. E., and Balarezo-Núñez, R. M. (2020). Corporate environmental reputation: Exploring its definitional landscape. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 29, 130–142. doi:10.1111/beer.12250

Matthews, R., and Denison, E. F. (1981). Accounting for slower economic growth: The United States in the 1970s. Econ. J. 91 (364), 1044. doi:10.2307/2232516

Nordberg-Bohn, V. (1999). Stimulating “green” technological innovation: An analysis of alternative policy mechanisms. Policy Sci. 32 (1), 13–38. doi:10.1023/A:1004384913598

Palmer, K., Oates, W. E., and Portney, P. R. (1995). Tightening environmental standards: The benefit-cost or the No-cost paradigm? J. Econ. Perspect. 9 (4), 119–132. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.119

Porter, M. E., and Van der Linde, C. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 9 (4), 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Requate, T. (2005). Dynamic incentives by environmental policy instruments: A survey. Ecol. Econ. 54, 175–195. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.12.028

Shen, F., Liu, B., Luo, F., Wu, C., Chen, H., and Wei, W. (2021). The effect of economic growth target constraints on green technology innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 292, 112765. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112765

Shen, N. (2012). The threshold effect of environmental regulation on regional technological. Innovation[J]. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 22 (06), 12–16.

Shen, W. N., Chai, Z. Y., and Zhang, H. M. (2020). Heterogeneous ecological environmental attention and environmental governance Performance─Based on the “government work report” in beijing-tianjin-hebei region[J]. Soft Sci. 34 (09), 65–71. doi:10.13956/j.ss.1001-8409.2020.09.10

Simon, H. A. (1947). Administrative behavior: A study of decision making processes in administrative organization. New York: The Macmillan Company, 85–98. doi:10.2307/2390693

Song, M., Yang, M. X., Zeng, K. J., and Feng, W. (2020). Green knowledge sharing, stakeholder pressure, absorptive capacity, and green innovation: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 29 (3), 1517–1531. doi:10.1002/bse.2450

Song, P., Chen, M. Y., and Mao, X. Q. (2022). Does central environmental protection inspection promote green innovation of heavily pollution Companies?─Evidence from green patent data of Chinese listed companies[J]. Chin. J. Environ. Manag. 14 (03), 73–80. doi:10.16868/j.cnki.1674-6252.2022.03.073

Su, X., and Zhou, S. S. (2019). Dual environmental regulation, government subsidy and enterprise innovation output. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 29 (3), 31–39. AvaliableAt: https://kns-cnki-net-443.webvpn.cueb.edu.cn/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=ZGRZ201903004&DbName=CJFQ2019.

Tan, C. C., Wang, Z., and Zhou, P. (2022). Fintech “enabling” and enterprise green innovation: From the perspectives of credit rationing and credit supervision[J/OL]. J. Finance Econ. 2022, 1–18. doi:10.16538/j.cnki.jfe.20220519.101

Tian, X. W., Ruan, W. J., and Xiang, E. W. (2017). Open for innovation or bribery to secure bank finance in an emerging economy: A model and some evidence. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 142, 226–240. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2017.08.002

Wang, J. F. (2013). Paying attention to the attention in democratic governance-commenting on reconceiving decision-making in democratic politics attention, choice, and public policy. J. Public Adm. 5, 144.

Wang, R. J., and Wu, J. Z. (2021). Attention congruence, environmental protection interview and environmental governance efficiency: Based on polynomial regression combined with response surface analysis[J]. J. Northeast. Univ. Sci. 23 (04), 42–50. doi:10.15936/j.cnki.1008-3758.2021.04.006

Wang, X. Q., Hao, S. G., and Zhang, J. M. (2020). New environmental protection law and corporate green innovation: Forcing or forcing out? China Popul. Resour. Environ. 30 (7), 107–117. doi:10.12062/cpre.20200130

Wang, Y. H., and Li, M. Z. (2017). Study on local government attention of ecological environment governance[J]. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 27 (2), 28–35.

Weitzman, M. L. (1974). Prices vs. Quantities. Rev. Econ. Stud. 41 (4), 477–491. doi:10.2307/2296698

Wen, H., and Du, F. F. (2018). The evolution logic of attention, policy motivation and policy Behavior─Based on the inspection of process of central government’s environmental protection policy from 2008 to 2015[J]. Adm. Trib. 25 (02), 80–87. doi:10.16637/j.cnki.23-1360/d.2018.02.012

Wen, H. (2014). A measurement of government’s attention to basic public services in China: Based on the text analysis of the central government work report(1954-2013)[J]. Jilin Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Ed. 54 (02), 20–26+171. doi:10.15939/j.jujsse.2014.02.012

Wong, S. K. (2012). The influence of green product competitiveness on the success of green product innovation: Empirical evidence from the Chinese electrical and electronics industry. Eur. J. Innovation Manag. 15 (4), 468–490. doi:10.1108/14601061211272385

Wu, C., Yang, S. W., Tang, P. C., Wu, T., and Fu, S. K. (2018). Construction of the efficiency promotion model of green innovation in China’s heavy polluted industries. [J]. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 28 (5), 40–48.

Xie, R. H., Yuan, Y. J., and Huang, J. J. (2017). Different types of environmental regulations and heterogeneous influence on “green” productivity: Evidence from China. Ecol. Econ. 132, 104–112. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.10.019

Xu, Z. W., and Li, R. H. (2019). Polluters’ survival pathway: An investigation and rethink on “too polluted to fail”. J. Finance Econ. 45 (7), 84–96.

Yang, G. C., Zheng, J., Lian, P., and Bing, M. (2017). Tax-reducing incentives, R&D manipulation and R&D performance. Econ. Res. J. 52 (8), 110–124.

Zhang, C., Lu, Y., Guo, L., and Yu, T. S. (2011). The intensity of environmental regulation and technological progress of production[J]. Econ. Res. J. 46 (02), 113–124.

Zhang, M. E., and Vander, L. C. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 94, 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Zhang, Y., Yuan, B. L., Zheng, J. J., and Deng, Y. L. (2022). Strategic response or substantive response? The effect of china’s carbon emissions trading policy on enterprise green innovation. Nankai Bus. Rev., 1–24.

Zheng, S. Q., Wan, G. H., Sun, W. Z., and Luo, D. L. (2013). Public appeal and urban environmental governance[J]. J. Manag. World 06, 72–84. doi:10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2013.06.006

Zhou, L. Q. (1999). The evolution and development of the reform theory of state-owned enterprises in China[J]. Nankai J. (Philosophy, Literature Soc. Sci. Ed. 02, 2–9.

Keywords: government’s environmental attention, green innovation, FinTech, heavy polluting firms, non-heavy polluting firms

Citation: Chen J, Li Q and Wang X (2022) Does the government’s environmental attention improve enterprise green innovation?—Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:999492. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.999492

Received: 21 July 2022; Accepted: 22 August 2022;

Published: 09 September 2022.

Edited by:

Shiyang Hu, Chongqing University, ChinaReviewed by:

Feng Cao, Hunan University, ChinaKun Huang, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China

Copyright © 2022 Chen, Li and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jing Chen, Y2hlbmppbmdAY3VlYi5lZHUuY24=

Jing Chen

Jing Chen Qinyang Li2

Qinyang Li2