- 1School of Economics, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, China

- 2School of Management Engineering, Shandong Jianzhu University, Jinan, China

Air pollution, an influencing factor for decision-making behavior, is closely related to company risk-taking, which affects high-quality economic development. Based on a fixed effect model, using the panel data of non-financial listed companies from China’s A-share markets from 2011 to 2019, this study empirically analyzes the influence of air pollution on company risk-taking and the moderating role of digital finance. The benchmark regression results reveal that air pollution has a significantly negative impact on company risk-taking. Mechanism analysis reveals that digital finance that is not “green development-oriented” can strengthen such relationship. The results of the heterogeneity analysis demonstrate that the negative impact of air pollution on risk-taking is more significant within private companies and those located in the eastern and central regions. Digital finance impacts companies with strict financing constraints more significantly. This study provides a reference for reducing the negative impact of air pollution on high-quality economic development.

1 Introduction

The traditional economic development in China continues to heavily rely on the consumption of petrochemical resources. This leads to serious air pollution, threatens the human living environment, and hinders high-quality economic development. According to the 2021 China Ecological Environmental Status Bulletin, only 64.3% of 339 cities reach the country’s air quality standards. Air pollution seriously affects people’s physical health and mental health (Feng et al., 2019; Dhimal et al., 2021; Sun C. et al., 2022; Zhang G. et al., 2022b; Lin et al., 2022). The World Health Organization ranked air pollution at the top of the Ten Human Health Threats in 2021. Air pollution can further impact consumption (Agarwal et al., 2021; Du et al., 2022), income distribution (Zhou and Li, 2021), property prices (Sun and Yang, 2020), labor welfare, and labor supply (Wang et al., 2021; Li and Li, 2022) at the macroeconomic level. At the microeconomic level, companies form an important part of the social economy and have been affected by air pollution in many aspects. Examples include debt financing capacity (Tan J. et al., 2022b), company cash holdings (Tan et al., 2021), location choices (Tang and Dou, 2021), and market value (Su et al., 2017). Certain scholars focus on the influence of air pollution on company management decisions from the insights of innovation, capital-labor ratio, and investment (Busch and Hoffmann, 2007; Li et al., 2021a; Liu B. et al., 2021; Sun Y. et al., 2022). In the process of China’s economic transition from the mode of traditional extensive growth to high-quality development, it has become an important issue to explore the mechanisms of how air quality affects micro company decision-making behavior.

A company’s risk-taking level is a result of decision-making behavior. The risk-taking level embodies the willingness and tendency of a company to pay the price for pursuing high profits and further reflects a company’s preference for venture investment projects (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996; Steul, 2006). An improvement in risk-taking means that the company tends to choose high-risk investment projects, rather than foregoing projects with positive net present value (NPV) and risks (Shahzad et al., 2019; Tan J. et al., 2022). Reasonable risk-taking can improve a company’s core competitiveness, which is conducive to long-term healthy and high-quality economic development (Vural-Yavas, 2020). Existing literature extensively investigates the internal and external influencing factors of company risk-taking. The former includes corporate governance mechanisms (John et al., 2008; Jiraporn et al., 2015), manager characteristics (Faccio et al., 2016; Teodósio et al., 2021), and company characteristics (Teodora, 2010; Faccio et al., 2011); the latter comprises uncertainty (Tran, 2019), cultural tradition (Li et al., 2013; Diez-Esteban et al., 2019), macro policy (Ljungqvist et al., 2017; Langenmayr and Lester, 2018), and institutional environment (Boubakri et al., 2013b). In the current stage of seeking high-quality economic development, environmental problems are increasingly a concern. Some scholars have studied the problems of company management from the perspective of the environment (Feng et al., 2017; Song et al., 2019; Zhang L. et al., 2021; Zhang G. et al., 2022; Zhu and Xu, 2022; Lin and Wu, 2022). However, to the authors’ knowledge, there are few studies on the change of company risk-taking from the perspective of air quality. This study is focused on this knowledge gap.

The willingness of a company for risk-taking is closely associated with its financing channels and capabilities (Wen et al., 2021). Digital finance is more technical than traditional finance (Gomber et al., 2017). It assesses the characteristics of companies in all respects through machine learning and other algorithms, which reduces the financing costs caused by the imperfection of the traditional financial market mechanism and information asymmetry (Yang and Zhang, 2020; Liu Z. et al., 2021c). Digital finance, which helps address many of the financing difficulties of companies (Ozili, 2018), has a certain impact on company risk-taking. In addition, the existing literature study the impact of digital financial on air pollution. Some scholars found that digital financial development inhibits air pollution (Zhao et al., 2021; Wang F. et al., 2022), but others indicated that the influence of digital finance on air pollution varies with its different levels, and shows an inverted U—shaped relationship (Li et al., 2021c). Therefore, the impact of digital finance on air pollution is still controversial. To guide digital finance to play a positive role in improving air quality, and promote the coordinated development of digitalization and greenization, the government has issued various policies. For example, the 14th Five-Year Plan points out that green low-carbon, and digital development should be accelerated. This paper further explores the regulatory role of digital finance in the relationship between air pollution and company risk-taking.

We use a fixed-effect panel data model to examine the impact of air pollution on company risk-taking, and explore the moderating role of digital finance on the relationship between air pollution and company risk-taking. Robustness tests were performed to ensure the robustness and reliability of the regression results. Considering the differences in companies’ pollution degree, the economic development levels where the companies are located, and companies’ ownership attributes, the heterogeneity of air pollution on the risk-taking level is discussed and analyzed.

This study makes three main contributions: 1) The influence mechanism of company risk-taking is analyzed from the perspective of an external environmental phenomenon—air pollution, which supplements previous studies mainly focusing on environmental regulation, green finance, and other environmental policies (Zhou et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2021; Chen and Zhao, 2022; Zhang Z. et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022; Peng and Zheng, 2021). By examining the impact of air pollution on risk-taking, this study provides important theoretical support for improving air quality and promoting the coordinated development of the environment and economy. 2) We adopt a relationship framework between air pollution, digital finance, and company risk-taking. It is shown that digital finance plays an important role in regulating the relationship between air pollution and company risk-taking. Our research focuses more on the role of “green development-oriented” digital finance in improving air quality and enhancing the level of company risk-taking, which makes up for the deficiency of traditional finance in this aspect. 3) The heterogeneity of the impact of air pollution on company risk-taking is discussed and analyzed based on the difference in companies’ pollution degree, the economic development levels where the companies are located, and companies’ ownership attributes. The research results can provide a practical basis for improving air quality, balancing resource endowment among different regions, and formulating differentiated ownership policies.

2 Literature review and research hypothesis

2.1 Air pollution and company risk-taking

Air pollution mainly affects company risk-taking through two aspects. First, air pollution can affect a manager’s emotion and cognition, cause behavioral decision-making biases (Jo et al., 2022), and then affect the level of company risk-taking. In the long run, the healthy operation and development of companies will be compromised. As far as the impact of air pollution is concerned, rational executives exhibit the risk-averse tendency and reduce investment in high-risk projects, inhibiting a company’s risk-taking intentions. Jiang et al. (2022) showed that air pollution affects earnings management by reducing labor productivity and exacerbating negative emotions, leading companies to shift real earnings management to accrual earnings management to reduce financial risks. Tan et al. (2021) indicated that air pollution can increase pessimism and weaken management cognitive ability, which leads to poor company operation. Therefore, companies tend to increase cash holdings to prevent risk. There is also a negative association between air pollution and the quality of financial reports, which reduces the level of company risk-taking (Hu et al., 2021).

Second, air pollution reduces the level of company innovation by increasing labor force capital, which further lowers the risk-taking level. Risk-taking is an orientation of decision-making behavior, and an intermediate process of realizing innovation-driven development (García-Granero et al., 2015). Company innovation is essentially a venture investment project (Tan, 2001). A company with a strong innovation capacity usually has a high risk-taking level. People presumably seek work in less polluted areas favorable to their health and emotional well-being (Xue et al., 2021). Air pollution has a significantly positive influence on executive payments (Zhang L. et al., 2021a). In this case, the company often needs more capital and replaces more low-quality laborers with fewer high-quality laborers, to increase the capital-labor ratio and maintain market competitiveness (Liu B. et al., 2021a). An increase in labor force capital leads to a reduction in R&D investment. Under the effect of human capital, a company’s technological innovation ability and level of risk-taking are reduced (Wang and Wu, 2020; Tan and Yan, 2021). Based on the above two aspects, air pollution limits the risk-taking level of companies. Therefore, we arrive at Hypothesis H1:

Hypothesis H1. Air pollution inhibits company risk-taking.

2.2 The moderating effect of digital finance

With the development of the digital economy, digital finance is an innovative financial model linking traditional finance and information technology. Digital finance encompasses a wide range of financial services, financial products, financial software, and novel channels of customer communication provided by financial fintech and service companies (Ozili, 2018; Hasan et al., 2020). Digital finance plays an important role in addressing companies’ risk problem (Liu B. et al., 2021). Digital finance can offer more financial support to companies through innovative, inexpensive, high-quality, and fast service content and forms (Ravikumar, 2019). Sufficient financial support is a necessary condition for a company to invest in high-risk projects (Deng and Liu, 2019; Wang, 2022). The willingness of a company to take risks is directly determined by the financing constraints. Digital finance can ease the financing constraints faced by companies, and then affect the level of risk-taking (Cao et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2022). If the financing constraint is weak and the availability of credit funds is strong, a company will prefer to invest in high-risk projects, thus elevating the level of company risk-taking (Ferris et al., 2017). In addition, digital finance can also prevent liquidity imbalance and capital structure problems (Yang and Zhang, 2020), promote company innovation (Hsu et al., 2014; Pan et al., 2022; Zhao and Wang, 2022), and increase information transparency and reduce financial leverage (Ji et al., 2022) to enhance the level of company risk-taking. It can be seen that digital finance has a positive impact on company risk-taking. Therefore, we arrive at Hypothesis H2:

Hypothesis H2. The development of digital finance promotes company risk-taking.

Studies show that digital finance lowers the emission of carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and PM2.5 through technological innovation, capital allocation, and structural adjustment (Muganyi et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021; Shahbaz et al., 2022). Digital finance shortens the time and distance to conduct financial activities, improve operation efficiency, and simultaneously generates environmental benefits (Yang et al., 2022). Shi et al. (2022) indicated that with the enhancement of digital finance development, environmental pollution can be effectively alleviated. Li et al. (2021c) found that in the early stage of digitization, carbon dioxide emissions continue to increase, and when digitization reaches a higher level, carbon dioxide emissions begin to decline. Chang (2022) believed that digital finance can reduce agricultural carbon emissions through its impact on farmers’ entrepreneurship and agricultural technological innovation. Wan et al. (2022) indicated that there is a significant negative correlation between digital finance and pollutant emissions and the impact varies in different regions. Yang et al. (2021) showed that there is a certain threshold for the influence of digital finance on the PM2.5 concentration. When the development of digital finance is lower than the threshold, it has an inhibitory effect on PM2.5 concentration; when the development of digital finance exceeds a certain level, pollution will be reduced. Wang et al. (2022b) pointed out that digital finance is conducive to haze reduction by enhancing regional innovation capacity. Thus, there is no clear conclusion about the effect of digital finance on air pollution.

To guide digital finance to play a positive role in improving air quality and promote the coordinated development of digitalization and greening, the government has issued various policies. For example, the 14th Five-year Digital Economy Development Plan points out that green development should be promoted in the process of digital transformation. The 14th Five-year National Informatization Plan puts forward leading the greening with digitization. Studies have confirmed that if digital finance can be oriented to improve environmental problems, it can achieve the effect of reducing pollutant emissions and improving company risk levels (Hong et al., 2021; Xing et al., 2021; Wang F. et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2022). Therefore, if digital finance development is “green development-oriented,” the improvement in the digital finance development level will weaken the inhibitory impact of air pollution on a company’s risk-taking level. Conversely, digital finance will reinforce such a relationship. Therefore, we propose Hypotheses H3a and H3b.

Hypothesis H3a. If the digital finance development is “green development-oriented,” digital finance will weaken the inhibitory impact of air pollution on company risk-taking level.

Hypothesis H3b. If the digital finance development is not “green development-oriented,” digital finance will strengthen the inhibitory impact of air pollution on company risk-taking level.

3 Research design

3.1 Data source and sample selection

Considering the availability of data related to air pollution, development of digital finance, and company risk, we adopt the panel data of non-financial listed companies1 from China’s A-share markets from 2011 to 2019 as the sample. We eliminated ST- and *ST-listed companies, and companies with major variables missing. The air pollution index uses provincial-level panel data from the Atmospheric Composition Analysis Group at Washington University to measure the PM2.5 concentrations on the earth’s surface. Digital finance adopts the Peking University Digital Financial Inclusion Index of China at the provincial level. The data obtained from CSMAR are calculated to measure company risk-taking. Data on the nature of property rights are derived from the CCER database. The industry to which the company belongs refers to the industry code and industry category code in the Guidelines on Industry Classification of Listed Companies stipulated by CSRC (revised in 2012). To alleviate some endogeneity problems, this paper matches the macroscopical air pollution and digital finance with the microscopical company risk-taking to verify the impacts of air pollution and the development level of digital finance on company risk-taking.

The original samples were cleaned as follows: 1) we deleted companies in finance industries since their supervision system and reporting structure differ greatly from those of other industries2; 2) we excluded ST and *ST companies because their financial situation and transaction mechanisms are abnormal; 3) some companies that have key variables missing, including innovation, digital finance, and manager’s ability, were abandoned; 4) samples with an asset-liability ratio higher than 100% (insolvency) were excluded; 5) to avoid the influence of abnormal values on regression analysis, all the continuous variables were 1% level winsorized. Stata15 was used to conduct regression analysis on the screened sample of 12,545 companies.

3.2 Variable selection

3.1.1 Explained variable: Company risk-taking

A company’s level of risk-taking mainly refers to the ability to take operational and financial risks. To date, the main approaches used to measure company risk-taking level are returns volatility and volatility of stock returns (Boubakri et al., 2013b). Some scholars also adopted the debt ratio, the possibility of company survival, R&D expenditure and capital expenditure (Coles et al., 2006; Faccio et al., 2011). Return volatility is the most classical method used in the academic community to measure company risk-taking. Therefore, this study referred to Acharya et al. (2011), the volatility (Risk1) and range (Risk2) of return on total assets adjusted by the industry average values during 3-year observation period were used to measure company risk-taking. The specific calculation process is as follows:

Whereby, adjROAit represents the returns of total assets adjusted by the industry average values of company i in the tth year. EBITit represents the earnings before interest and tax of company i in the tth year. avgAssetit represents average assets of company i in the tth year, namely the average of the sum of assets at the beginning and the end of the tth year. j represents the industry to which company i belongs. nijt represents the number of companies in industry j to which company i belongs in the tth year. T represents the observation period. This study selected a 3-years observation period, namely T = 3.

3.1.2 Explanatory variable: Air pollution

The central explanatory variable is the level of air pollution. The existing studies mainly used PM2.5 concentration and air quality index (AQI) to evaluate the level of air pollution. Considering the data availability and the robustness of the conclusions, data from the Atmospheric Composition Analysis Group at Washington University were applied to weigh the PM2.5 concentrations of the earth’s surface. The level of air pollution was measured by the population-weighted annual average of PM2.5 concentration. In the robustness tests, the geography-weighted annual average of PM2.5 concentration was used to measure the level of air pollution.

3.1.3 Moderating variable

The moderating variable is digital finance. The digital finance at the provincial level from 2011 to 2019 that was compiled by the Institute of Digital Finance of Peking University, was adopted to weigh digital finance (Guo et al., 2020). It builds a digital finance system from the digital financial depth, coverage, and the support of services three dimensions, and has a wide range of use. In the regression analysis, the development index of digital financial inclusion was reduced 100 times.

3.1.4 Control variables

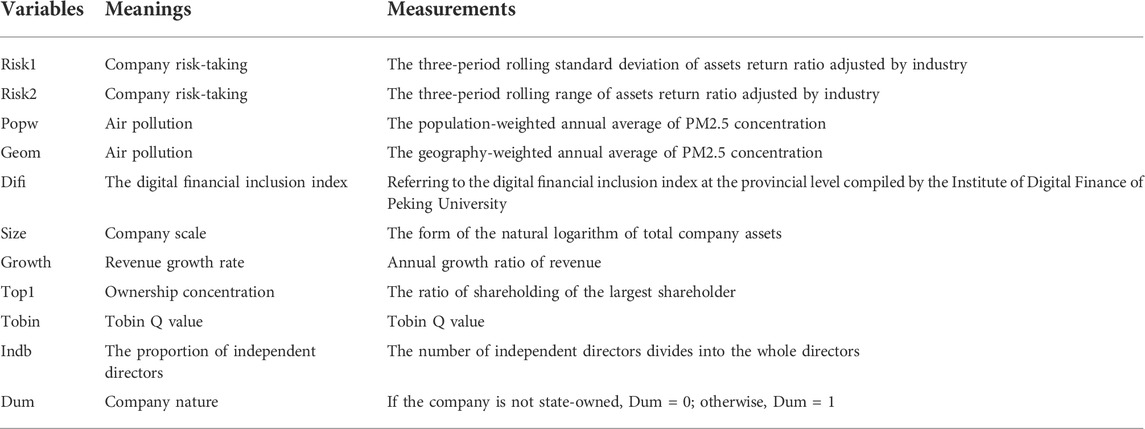

Following Li et al., 2021a the following five control variables that affect company risk-taking in the regression analysis were selected: 1) the variable Size reflects the company scale characteristics, and weighed by the form of the natural logarithm of total company assets; 2) Growth represents the increase rate of revenue and the variable Tobin represents Tobin Q value. Both Growth and Tobin reflect the solvency of the company; 3) Top1 represents ownership concentration and reflects the situation of company governance, and is measured by the ratio of shareholding of the largest shareholder; 4) Indb reflects the proportion of independent directors, which is measured by the number of independent directors dividing to the whole directors; 5) Dum reflects the nature of the company. If the company is not state-owned, Dum = 0; otherwise, Dum = 1. In addition, the industry fixed effect and year fixed effect were controlled. Table 1 demonstrates the relevant variables.

3.3 Model specification

According to the theoretical mechanism analysis, it can be seen that air pollution may be a key factor affecting company risk-taking. However, whether this conclusion is tenable in the current stage of economic development needs further investigation. The sample data adopted in this paper are panel data; the results of the Hausman test indicate that a fixed effects model is needed (Hausman, 1978). Due to the different situations of each province and industry, there may be either missing variables that do not change with time or missing variables that do not change with the industry. Therefore, a fixed effect model (FE) with fixed industry and time is considered. For testing the impact of air pollution on company risk-taking, we adopt the EF model as follows:

Whereby i represents the company’s serial number, and t represents the year’s serial number. The variable Risk represents company risk-taking. AirPoll is the core explanatory variable. Control represents the set of control variables, including company scale (Size), ownership concentration (Top1), increase rate of revenue (Growth), Tobin Q value (Tobin), proportion of independent directors (Indb), and company nature (Dum). ind and year represent industry fixed effect and year fixed effect. α0 represents the intercept item. ε is the random interference term. In view of the fact that the more serious the air pollution, the more managers are inclined to make short-sighted decisions, which results in a reduction in the level of risk-taking. Therefore, we expect α1 in Model (1) to be significantly negative.

Additionally, this paper continues to explore whether digital finance moderates the association between air pollution and company risk-taking. Regardless of air quality, the development level of digital finance has an important relationship with the financing constraints, which is closely related to the growth of companies. Generally, the higher the development level of digital finance, the lower the financing constraints. The direct impact on company risk-taking is mainly reflected in the capital needed to improve the level of company risk-taking. However, when environmental factors are taken into account, the digital finance development may lead to the loss of core technical talents in company innovation. With that in mind, the following model is constructed:

Following on, a further examination of the moderating role of financing constraints on the development level of digital finance between air pollution and company risk-taking will be undertaken. The following model is therefore constructed:

Whereby, SA represents the financing constraints faced by the company. In reference to Hadlock and Pierce (2010), SA =—0.737 × Size + 0.043 × Size2—0.04 × Age. The variable Age indicates for how many years the company is established. With the increase of SA, the financing constraints of companies become stronger. Therefore, we expect α6 to be significantly negative in Model (6).

4 Empirical results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

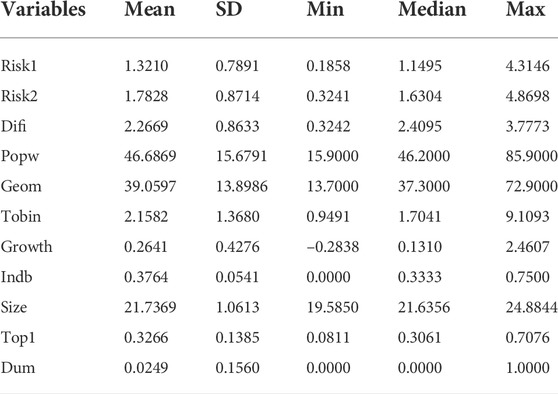

Table 2 The descriptive statistical characteristics of the main variables. Results demonstrate that the average risk-taking level (Risk1) of China’s non-financial listed companies is 1.3210. The minimum and maximum risk-taking levels are 0.1858 and 4.3146, respectively. The average of Risk2 is 1.7828, the maximum is 4.8698, and the minimum is 0.3241. The descriptive statistical results of Risk1 and Risk2 indicate large differences in risk-taking levels among different companies. The average air pollution Popw (core explanatory variable) is 46.6869, and the standard deviation is 15.6791, indicating large differences in air pollution levels across different areas. The average development level of digital finance (moderating variable) is 2.2669, the maximum is 3.7773, and the minimum is 0.3242, indicating large differences in the development level of digital finance among different regions.

4.2 Benchmark test

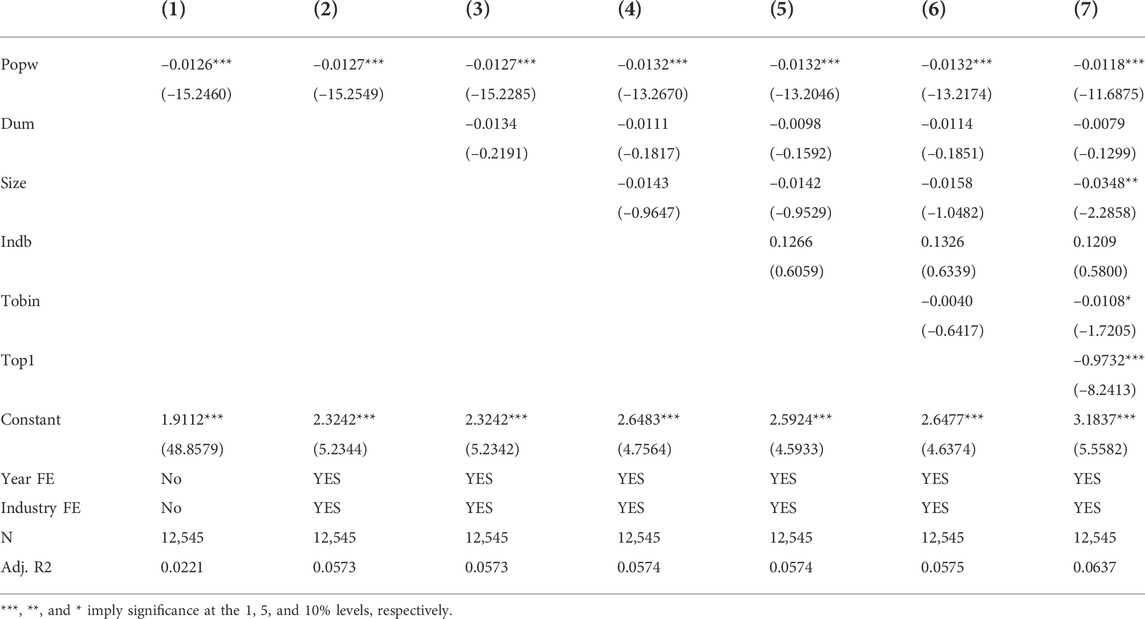

Table 3 reports the benchmark regression results of air pollution and company risk-taking. Column (1) in Table 3 only controls the air pollution level (Popw). The results show that the regression coefficient of Popw is –0.0126, and it is significantly negative at the 1% level, which imply that aggravated air pollution significantly reduces the company’s risk-taking level. Thus, the aggravated air pollution level in cities does not force companies to raise company risk-taking but instead weakens their incentive to take risks, which supports Hypothesis H1.

After controlling the year fixed effect and industry fixed effect, Model (2) shows that the coefficient of air pollution (Popw) is –0.0127, which is still significantly negative, demonstrating air pollution still has a strong inhibiting effect on company risk-taking. On one hand, air pollution leads to an increase in internal and external governance costs for companies; on the other hand, it damages the physical and mental health of employees, which is not conducive to company risk-taking. To guarantee robust results, a stepwise regression of adding control variables is performed. Following the addition of the control variables of company nature (Dum), company scale (Size), the proportion of independent directors (Indb), Tobin Q value (Tobin), and ownership concentration (Top1), the coefficient of air pollution level (Popw) remains significantly negative. The results are shown in Columns (3)–(7) of Table 3.

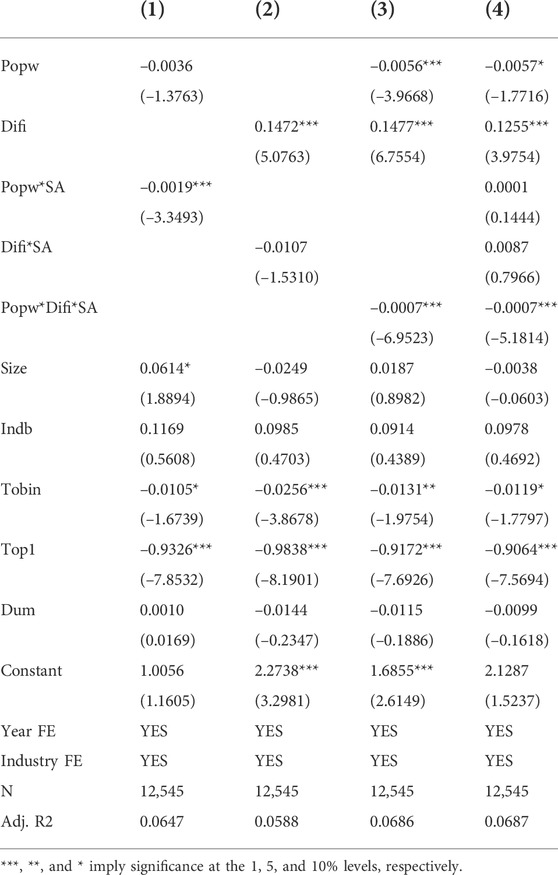

4.3 Moderating effect test

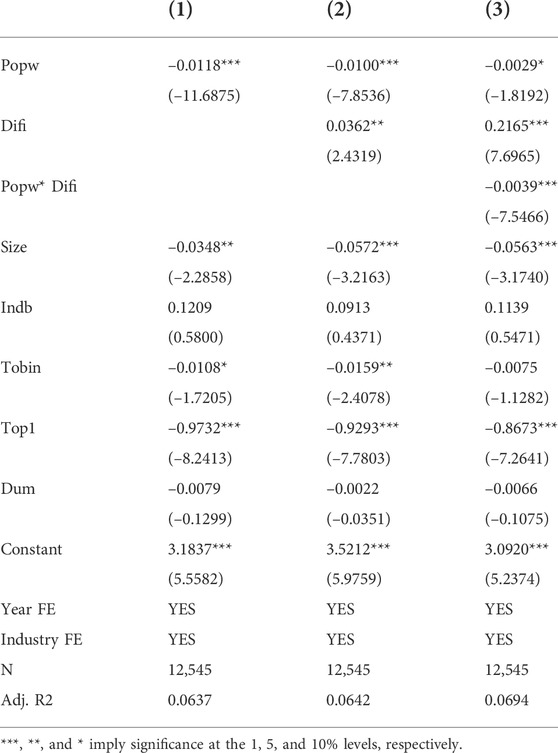

First, the overall effect of digital finance is discussed. The regression results are shown in Table 4. Based on Model 1) in Table 3, we add the indicator of the digital finance development; the results are then demonstrated in Column (1) of Table 4. When the results of both results are compared, the inhibitory impact of air pollution (Popw) remains unchanged, which demonstrates the robustness of the analysis. Correspondingly, digital finance (Difi) is used to obtain the regression results of Column (2) in Table 4. As shown in Column (2), the regression coefficient of the development level of digital finance is significantly positive, which indicates that the overall impact of the digital finance development on the company’s risk-taking is significantly positive. The regression coefficient and significance are consistent with existing studies (Ma and Du, 2021), which means that digital finance improves the level of company risk-taking through the advantages of resource effect and information effect. In addition, digital finance can ease financing constraints or motivate company innovation (Hsu et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2022; Pan et al., 2022), which indirectly improves the level of company risk-taking. Hypothesis H2 is therefore supported.

Second, this study examines the moderating effect of the development level of digital finance on the relationship between air pollution and company risk-taking. For this purpose, the cross-term of air pollution and digital finance is added and the regression results are shown in Column (3) of Table 4. We explored the direct and indirect effects of digital finance on company risk-taking. The value of the regression coefficient of digital finance reflects the direct effect, and the value of the cross-term coefficient of air pollution and digital finance reflects the indirect effect. The cross-term coefficient of air pollution and digital finance is significantly negative. This shows that the development of digital finance has strengthened the negative relationship between air pollution and company risk-taking. The regression results confirm Hypothesis H3b, which shows that when the development level of digital finance is not oriented by green development, companies may be unwilling to take risks. In previous studies, the effect of digital finance on pollution reduction is not clear, and some regions with better development of digital finance have aggravated air pollution (Yang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022). Therefore, the state has also issued relevant policies such as the 14th Five-year Digital Economy Development Plan to guide the green orientation of digitalization and to promote the coordinated development of digitalization and greening. Therefore, when the development of local digital finance is “not green-oriented,” it will strengthen the negative relationship between air pollution and a company risk-taking.

Hypothesis H3b supposes that if the development of local financial institutions is not green-oriented, the improvement of digital finance will reinforce the negative relationship between air pollution and company risk-taking. The possible mechanism is that digital finance development without green orientation reduces financing constraints and the willingness of the company to take risks. Table 5 introduces the cross-term air pollution level (Popw), development level of digital finance (Difi), and financing constraint (SA). The cross-term coefficient of air pollution level (Popw), development level of digital finance (Difi), and financing constraint (SA) is significantly negative at the level of 1%. This indicates that the stronger the financing constraint faced by the companies, the more obvious the moderating effect of regional digital finance on the negative relationship between air pollution and company risk-taking. This demonstrates that digital finance development without a green orientation reduces both the financing constraints and the willingness of the company to take risks.

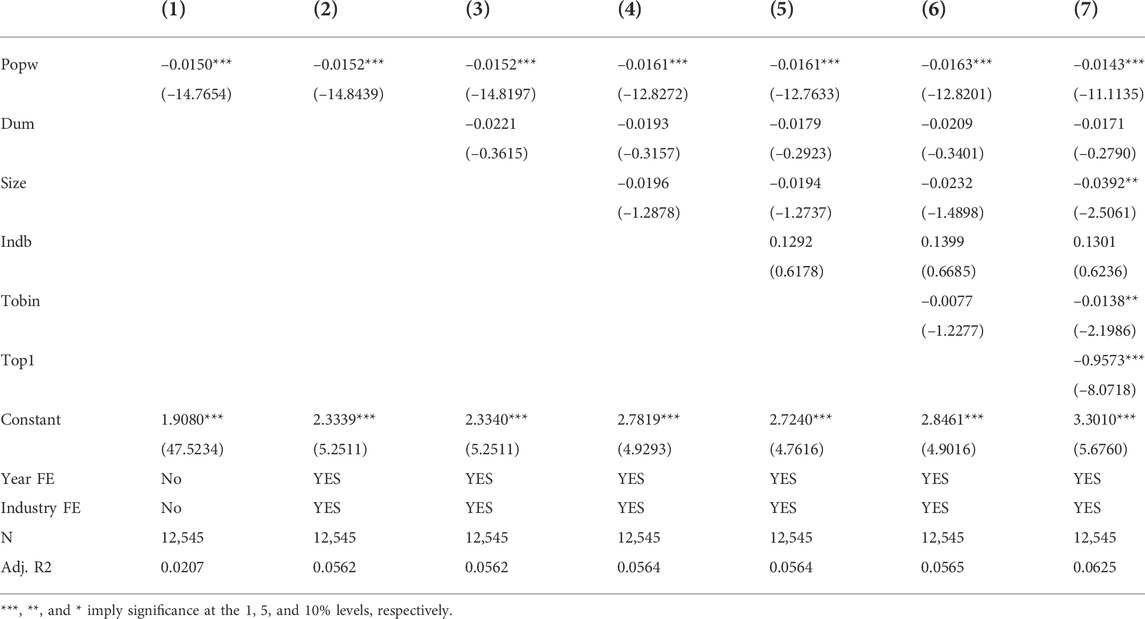

5 Robustness tests

5.1 Replacement of explained variables

Company risk-taking level adopts the three-period rolling standard deviation of assets return ratio adjusted by industry (Risk1) in the benchmark model. In the robustness test, the three-period rolling range of assets returns ratio adjusted by industry (Risk2) is used to replace the explained variable for re-estimating the regression model. The regression results are shown in Table 6. Column (1) only controls the variable of air pollution level (Popw). The results show that the regression coefficient is significantly negative, indicating that the air pollution level significantly reduces the company’s risk-taking level. After controlling the year fixed effect and industry fixed effect, it can be seen from Column (2) that the regression coefficient of air pollution (Popw) is −0.0152, which is still significantly negative, indicating that air pollution (Popw) significantly inhibits company risk-taking. To obtain more robust results, the regression analysis was performed by the stepwise addition of the following control variables: company nature (Dum), company scale (Size), the proportion of independent directors (Indb), Tobin Q value (Tobin), and ownership concentration (Top1). The results in Columns (3)–(7) of Table 6 clearly show that following the regressions, the coefficient of air pollution level (Popw) remains significantly negative. The results of this study are robust based on these tests.

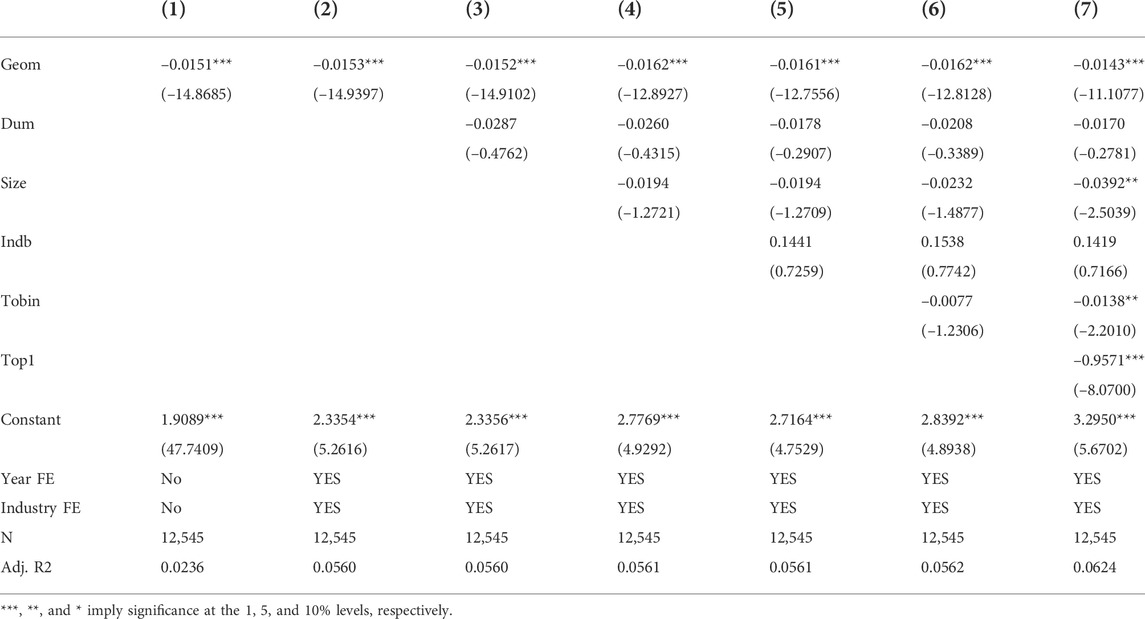

5.2 Replacement of explanatory variables

The air pollution level in the benchmark regression model is the population-weighted annual average of PM2.5 concentration (Popw). In the robustness test, the geography-weighted annual average of PM2.5 concentration (Geom) is used to replace the explanatory variable Popw, and the regression model is re-estimated. Table 7 shows the regression results. Only the air pollution level variable (Geom) is controlled for in Column (1). The results show that the regression coefficient is significantly negative, indicating that the air pollution level significantly reduces the company’s risk-taking level. After controlling the year fixed effect and industry fixed effect, it can be seen from Column (2) that the regression coefficient of air pollution (Popw) is –0.0153, which is still significantly negative, indicating that air pollution (Popw) significantly inhibits the company risk-taking level. To obtain more robust results, the regression analysis is performed using the stepwise addition of the following control variables: company nature (Dum), company scale (Size), the proportion of independent directors (Indb), Tobin Q value (Tobin), and ownership concentration (Top1). Following the regression, the coefficient of air pollution level (Geom) remains significantly negative. The results are shown in Columns (3)–(7) of Table 7. This again verifies the robustness of the regression results.

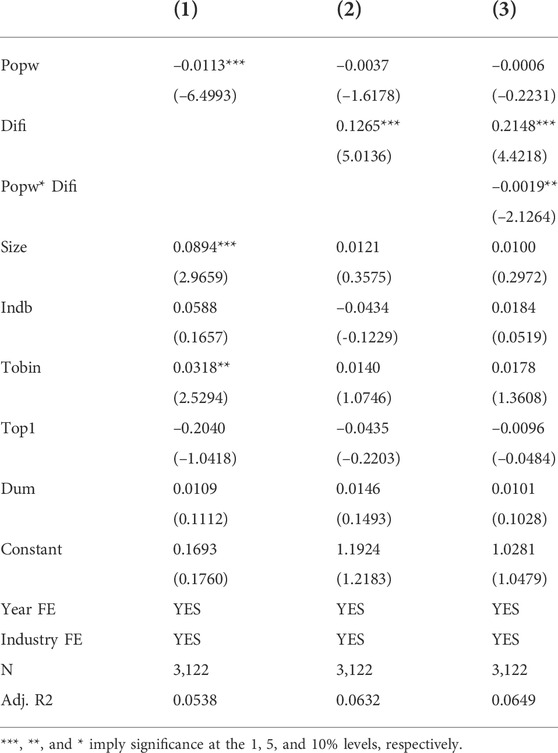

5.3 Re-test based on samples of heavy-polluting companies

In contrast to non-heavily polluting companies, heavily-polluting companies may have more of an incentive to improve the “green” content of their products through innovation, because of the adverse effects of tighter financial control policies to tackle air pollution. Therefore, we took heavily-polluting companies as samples for re-examination. The results are shown in Table 8. Heavily-polluting companies are usually more motivated to take risks to enhance their pollution control ability and to reduce the negative impact that air pollution may impose on the company risk-taking level. Table 8 shows that when compared with the whole sample in the benchmark regression results, the air pollution level has a weaker inhibiting effect on the risk-taking level of heavily-polluting companies, and the moderating effect of digital finance development is less significant.

5.4 Heterogeneity analysis

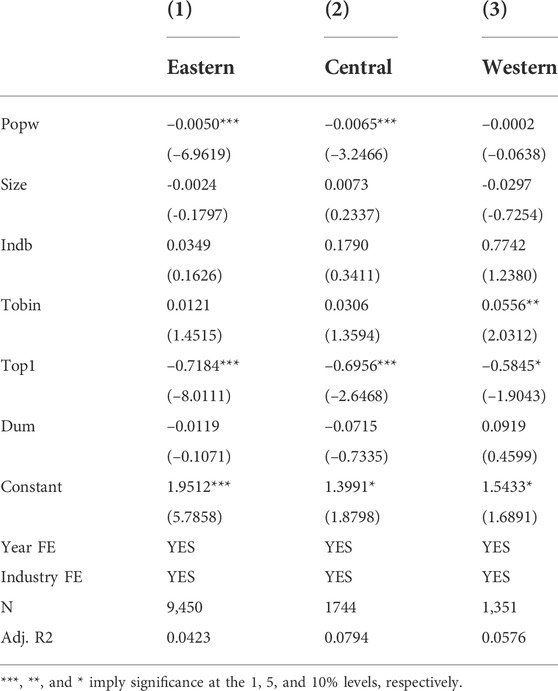

5.4.1 Air pollution, regional development, and company risk-taking

The gap in the level of economic development among the western, central, and eastern regions of China is vast. Regions with a high level of economic development and where risk-taking is lower are usually subject to serious air pollution. Therefore, to assess the robustness of the regression results, this paper further examined whether there is heterogeneity among different regions on the impact of air pollution on company risk-taking. First, the samples are divided into companies located in the western, central, and eastern regions. Sub-sample regressions are then carried out. Columns (1)–(3) of Table 9 show that the risk-taking level of companies in the western region is less sensitive to air pollution. By contrast, air pollution has a significantly negative impact on a company risk-taking level in the eastern and central regions and a greater negative impact on the companies in the central region. On account of the different levels of economic development and competitive environments in the eastern and western regions, air pollution levels may vary significantly. Because of the aggravation of air pollution, the company risk-taking is reduced.

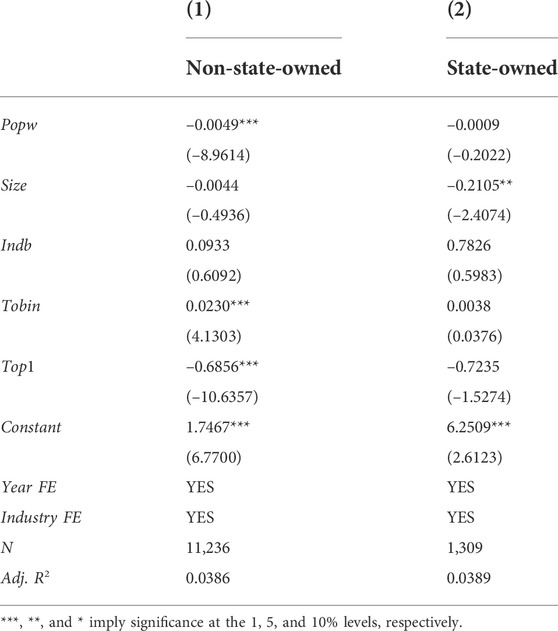

5.4.2 Air pollution, property nature, and company risk-taking

A company’s risk-taking level not only relates to macro factors but also to the unique characteristics of companies. To further analyze the heterogeneity impact of company characteristics on the relationship between air pollution and company risk-taking level, this section examines whether the company risk-taking level differs based on property rights. The test based on the nature of property rights divides the sample companies according to the nature of the actual controller. Table 10 shows the results. It can be seen that air pollution has a more significant effect on company risk-taking levels of non-state-owned companies than state-owned companies. This indicates a stronger marginal effect on non-state-owned companies in the process of reducing company risk-taking levels.

6 Discussion

This paper obtains the data of non-financial listed companies from China’s A-share markets from 2011 to 2019 as the research sample and then assesses whether air pollution affects the company’s risk-taking level through theoretical analysis and empirical tests. A further mechanism analysis based on the digital finance development level is conducted. The results demonstrate three main findings: 1) air pollution has a significantly negative impact on company risk-taking. This conclusion remains stable after replacing the core explanatory variable and the explanatory variable; 2) an improvement in digital finance can meet a company’s capital requirements in risk-taking. However, digital finance that is not “green development oriented” can strengthen the negative impact of air pollution on a company risk-taking; 3) moderating effect of digital finance is more evident amongst companies with strict financing constraints. The heterogeneity analysis further shows that the level of the negative relationship between air pollution and company risk-taking varies based on company nature, pollution levels, and regional development levels. This research has important policy implications for understanding both environmental protection issues and the economic consequences for companies.

This paper puts forward the following recommendations: 1) The government’s priority is to fully consider the negative impact of air quality on micro-economic entities, advocate for all society to improve environmental protection awareness, and further increase the weight of green development in the process of establishing and improving the high-quality economic development system. A good ecological environment is conducive to high-quality development of companies and contributes to the coordinated development of environmental protection and economic society. 2) Air pollution control policies should be formulated according to the different development levels and environmental conditions across regions. The eastern and central regions need to formulate stricter environmental protection policies, whereas vast land space and sparse populations in the western region cause air pollution to have a lower impact on company risk-taking. Because of the underdeveloped economy and the weak environmental carrying capacity, the focus should be placed on the control of air pollution in parallel with promoting economic development. Furthermore, consideration should be given to the fact that air pollution poses an obvious inhibiting effect on the risk-taking level of private companies, and the risk-taking level of private companies is higher than that of state-owned companies. 3) Service quality of digital finance should be actively improved. Government should formulate relevant policies to guide digital finance to be green-oriented and realize the coordinated development of digitalization and greenization. Through the improvement of digital financial service quality, it is beneficial for both better air pollution situations and higher company risk-taking levels. In the long term, the core competitiveness of enterprises will be further strengthened, which contributes to healthy and high-quality economic development.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, XL; methodology, XL; software, XL; validation, XL and YY; formal analysis, XL; investigation, XL; data curation, XL; writing–original draft preparation, XL; writing–review and editing, YY; visualization, YY; supervision, YY; funding acquisition, YY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Shandong Provincial Social Science Planning Project of China (No. 21DGLJ23).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1According to category J (financial industry) of the National Economic Industry Classification (GB/T4754-2011), financial companies are divided into monetary financial services, capital market services, insurance, and other financial services. Monetary financial services are divided into monetary banking services and non-monetary banking services. Other financial services are divided into financial trust and management services, holding company services, and other financial sectors not included. According to the economic nature, money banking service financial companies are classified as banking deposit financial institutions. Non-monetary banking service financial companies are divided into banking non-deposit financial institutions, loan companies, petty loan companies, and pawnshops. Capital market service financial companies were classified as securities financial institutions. Insurance financial companies were classified as insurance financial institutions. Other financial companies were divided into trust companies, financial holding companies, and other financial institutions except pawnshops. Then the companies not in category J (financial industry) were identified as non-financial listed companies.

2The financial statement preparation principles of financial listed companies are different from those of real companies. Their financial statement structure and major accounting items are industry-specific. In addition, there are high capital flows in financial companies, and the leverage ratio is high. But they do not create real wealth. If they are compared and analyzed together with non-financial companies, results are biased. Therefore, financial companies are excluded and non-financial companies are used in the study.

References

Acharya, V. V., Amihud, Y., and Litov, L. (2011). Creditor rights and corporate risk-taking. J. Financ. Econ. 102 (1), 150–166. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.04.001

Agarwal, S., Wang, L., and Yang, Y. (2021). Impact of transboundary air pollution on service quality and consumer satisfaction. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 192, 357–380. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2021.10.002

Boubakri, N., Cosset, J. C., and Saffar, W. (2013a). The role of state and Foreign owners in corporate risk-taking: Evidence from privatization. J. Financ. Econ. 108 (3), 641–658. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.12.007

Boubakri, N., Mansi, S. A., and Saffar, W. (2013b). Political institutions, connectedness, and corporate risk-taking. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 44, 195–215. doi:10.1057/jibs.2013.2

Busch, T., and Hoffmann, V. H. (2007). Emerging carbon constraints for corporate risk management. Ecol. Econ. 62, 518–528. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.05.022

Cao, S. P., Nie, L., Sun, H., Sun, W. F., and Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. (2021). Digital finance, green technological innovation and energy environmental performance: Evidence from China's regional economies. J. Clean. Prod. 327, 129458. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129458

Chang, J. (2022). The role of digital finance in reducing agricultural carbon emissions: Evidence from China’s provincial panel data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-21780-z

Chen, H., and Zhao, X. (2022). Green financial risk management based on intelligence service. J. Clean. Prod. 364, 132617. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132617

Chen, Y., Yao, Z., and Zhong, K. (2022). Do environmental regulations of carbon emissions and air pollution foster green technology innovation: Evidence from China’s prefecture-level cities. J. Clean. Prod. 350, 131537. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131537

Coles, J. L., Daniel, N. D., and Naveen, L. (2006). Managerial incentives and risk-taking. J. Financ. Econ. 79 (2), 431–468. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.09.004

Deng, W., and Liu, L. (2019). Comparison of carbon emission reduction modes: Impacts of capital constraint and risk aversion. Sustainability 11 (6), 1661. doi:10.3390/su11061661

Dhimal, M., Chirico, F., Bista, B., Sharma, S., Chalise, B., Dhimal, M. L., et al. (2021). Impact of air pollution on global burden of disease in 2019. Processes 9 (10), 1719. doi:10.3390/pr9101719

Diez-Esteban, J. M., Farinha, J. B., and Garcia-Gomez, C. D. (2019). Are religion and culture relevant for corporate risk-taking? International evidence. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 22 (1), 36–55. doi:10.1016/j.brq.2018.06.003

Du, H., Liu, H., and Zhang, Z. (2022). The unequal exchange of air pollution and economic benefits embodied in beijing-tianjin-hebei’s consumption. Ecol. Econ. 195, 107394. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107394

Faccio, M., Marchica, M. T., and Mura, R. (2016). CEO gender, corporate risk-taking, and the efficiency of capital allocation. J. Corp. Finance 39, 193–209. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.02.008

Faccio, M., Marchica, M. T., and Mura, R. (2011). Large shareholder diversification and corporate risk-taking. Rev. Financ. Stud. 24 (11), 3601–3641. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhr065

Feng, C., Shi, B., and Kang, R. (2017). Does environmental policy reduce enterprise innovation? — evidence from China. Sustainability 9 (6), 872. doi:10.3390/su9060872

Feng, Y., Cheng, J., Shen, J., and Sun, H. (2019). Spatial effects of air pollution on public health in China. Environ. Resour. Econ. 73, 229–250. doi:10.1007/s10640-018-0258-4

Ferris, S. P., Javakhadze, D., and Rajkovic, T. (2017). CEO social capital, risk-taking and corporate policies. J. Corp. Finance 47, 46–71. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.09.003

García-Granero, A., Llopis, Ó., Fernández-Mesa, A., and Alegre, J. (2015). Unraveling the link between managerial risk-taking and innovation: The mediating role of a risk-taking climate. J. Bus. Res. 68 (5), 1094–1104. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.10.012

Gomber, P., Koch, J. A., and Siering, M. (2017). Digital finance and FinTech: Current research and future research directions. J. Bus. Econ. 87, 537–580. doi:10.1007/s11573-017-0852-x

Guo, F., Wang, J., Wang, F., Kong, T., Zhang, X., and Chen, Z. (2020). Measuring China’s digital financial inclusion compilation and spatial characteristics. China Econ. Q. 19 (4), 1401–1418. doi:10.13821/j.cnki.ceq.2020.03.12

Hadlock, C. J., and Pierce, J. R. (2010). New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 23 (5), 1909–1940. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhq009

Hasan, M. M., Yajuan, L., and Khan, S. (2020). Promoting China’s inclusive finance through digital financial services. Glob. Bus. Rev., 097215091989534. doi:10.1177/0972150919895348

Hausman, J.450 (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica. 46 (6), 1251–1271. doi:10.2307/1913827

Hong, M., Li, Z., and Drakeford, B. (2021). Do the green credit Guidelines affect corporate green technology innovation? Empirical research from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (4), 1682. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041682

Hsu, P. H., Tian, X., and Xu, Y. (2014). Financial development and innovation: Cross-country evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 112 (1), 116–135. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.12.002

Hu, N., Xue, X., and Liu, L. (2021). The impact of air pollution on financial reporting quality: Evidence from China. Account. Finance. doi:10.1111/acfi.12898

Ji, Y., Shi, L., and Zhang, S. (2022). Digital finance and corporate bankruptcy risk: Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Finance J. 72, 101731. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2022.101731

Jiang, D., Li, W., Shen, Y., and Yu, S. (2022). Does air pollution affect earnings management? Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Finance J. 72, 101737. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2022.101737

Jiraporn, P., Chatjuthamard, P., Tong, S., and Kim, Y. S. (2015). Does corporate governance influence corporate risk-taking? Evidence from the institutional shareholders services (ISS). Financ. Res. Lett. 13, 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2015.02.007

Jo, H., Kim, H. E., and Sim, M. (2022). Environmental preference, air pollution, and fund flows in China. Pacific-Basin Finance J. 72, 101723. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2022.101723

John, K., Litov, L., and Yeung, B. (2008). Corporate governance and risk-taking. J. Finance 63 (4), 1679–1728. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2008.01372.x

Langenmayr, D., and Lester, R. (2018). Taxation and corporate risk-taking. Acc. Rev. 93 (3), 237–266. doi:10.2308/accr-51872

Li, B., Shi, H., Yang, D. C., and Peng, M. (2021a). Smog pollution, environmental uncertainty, and operating investment. Atmosphere 12 (11), 1378. doi:10.3390/atmos12111378

Li, B., Zhou, Y., Zhang, T., and Liu, Y. (2021b). The impact of smog pollution on audit quality: Evidence from China. Atmosphere 12 (8), 1015. doi:10.3390/atmos12081015

Li, K., Griffin, D., Yue, H., and Zhao, L. (2013). How does culture influence corporate risk-taking? J. Corp. Finance 23, 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2013.07.008

Li, X., and Li, Y. (2022). The impact of perceived air pollution on labour supply: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manage. 306, 114455. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114455

Li, X., Liu, J., and Ni, P. (2021c). The impact of the digital economy on CO2 emissions: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Sustainability 13, 7267. doi:10.3390/su13137267

Li, Z., Kuo, T. H., Siao-Yun, W., and Vinh, L. T. (2022). Role of green finance, volatility and risk in promoting the investments in renewable energy resources in the post-covid-19. Resour. Policy 76, 102563. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102563

Lin, B., and Wu, N. (2022). Will the China's carbon emissions market increase the risk-taking of its enterprises? Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 77, 413–434. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2021.10.005

Lin, C. C., Chiu, C. C., Lee, P. Y., Chen, K. J., He, C. X., Hsu, S. K., et al. (2022). The adverse effects of air pollution on the eye: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (3), 1186. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031186

Liu, B., Wu, J., and Chan, K. C. (2021a). Does air pollution change a firm’s business strategy for employing capital and labor? Bus. Strategy Environ. 30 (8), 3671–3685. doi:10.1002/bse.2833

Liu, Y., Luan, L., Wu, W., Zhang, Z., and Hsu, Y. (2021b). Can digital financial inclusion promote China’s economic growth? Int. Rev. Financial Analysis 78, 101889. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101889

Liu, Z., Zhang, X., Yang, L., and Shen, Y. (2021c). Access to digital financial services and green technology advances: Regional evidence from China. Sustainability 13 (9), 4927. doi:10.3390/su13094927

Ljungqvist, A., Zhang, L., and Zuo, L. (2017). Sharing risk with the government: How taxes affect corporate risk taking. J. Account. Res. 55 (3), 669–707. doi:10.1111/1475-679X.12157

Lu, Z., Wu, J., Li, H., and Nguyen, D. K. (2022). Local bank, digital financial inclusion and SME financing constraints: Empirical evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 58 (6), 1712–1725. doi:10.1080/1540496X.2021.1923477

Lumpkin, G. T., and Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manage. Rev. 21 (1), 135–172. doi:10.5465/amr.1996.9602161568

Ma, L., and Du, S. (2021). Can digital finance improve corporate risk-taking level? Economist 5, 65–74. doi:10.16158/j.cnki.51-1312/f.2021.05.008

Muganyi, T., Yan, L., and Sun, H. P. (2021). Green finance, fintech and environmental protection: Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 7, 100107. doi:10.1016/j.ese.2021.100107

Ozili, P. K. (2018). Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 18 (4), 329–340. doi:10.1016/j.bir.2017.12.003

Pan, W., Xie, T., Wang, Z., and Ma, L. (2022). Digital economy: An innovation driver for total factor productivity. J. Bus. Res. 139, 303–311. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.09.061

Peng, J., and Zheng, Y. (2021). Does environmental policy promote energy efficiency? Evidence from China in the context of developing green finance. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 733349. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.733349

Ravikumar, T. (2019). Digital financial inclusion: A payoff of financial technology and digital finance uprising in India. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 8 (11), 3434–3438.

Shahbaz, M., Li, J., Dong, X., and Dong, K. (2022). How financial inclusion affects the collaborative reduction of pollutant and carbon emissions: The case of China. Energy Econ. 107, 105847. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105847

Shahzad, F., Lu, J., and Fareed, Z. (2019). Does firm life cycle impact corporate risk taking and performance? J. Multinatl. Financial Manag. 51, 23–44. doi:10.1016/j.mulfin.2019.05.001

Shi, F., Ding, R., Li, H., and Hao, S. (2022). Environmental regulation, digital financial inclusion, and environmental pollution: An empirical study based on the spatial spillover effect and panel threshold effect. Sustainability 14 (11), 6869. doi:10.3390/su14116869

Song, Y., Yang, T., and Zhang, M. (2019). Research on the impact of environmental regulation on enterprise technology innovation—an empirical analysis based on Chinese provincial panel data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 21835–21848. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-05532-0

Steul, M. (2006). Does the framing of investment pportfolios influence risk-taking behavior? Some experimental results. J. Econ. Psychol. 27 (4), 557–570. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2005.12.002

Su, K., Li, L., and Wan, R. (2017). Ultimate ownership, risk-taking and firm value: Evidence from China. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 23 (1), 10–26. doi:10.1080/13602381.2016.1152021

Sun, B., and Yang, S. (2020). Asymmetric and spatial non-stationary effects of particulate air pollution on urban housing prices in Chinese cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (20), 7443. doi:10.3390/ijerph17207443

Sun, C., Yi, X., Ma, T., Cai, W., and Wang, W. (2022a). Evaluating the optimal air pollution reduction rate: Evidence from the transmission mechanism of air pollution effects on public subjective well-being. Energy Policy 161, 112706. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112706

Sun, Y., Hu, H., and Jin, G. (2022b). Pollution or innovation? How enterprises react to air pollution under perfect information. Sci. Total Environ. 831, 154821. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154821

Tan, C., He, C., Shi, Z., Mo, G., and Geng, X. (2022a). How does CEO demission threat affect corporate risk-taking? J. Bus. Res. 139, 935–944. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.034

Tan, J., Chan, K. C., and Chen, Y. (2022b). The impact of air pollution on the cost of debt financing: Evidence from the bond market. Bus. Strategy Environ. 31 (1), 464–482. doi:10.1002/bse.2904

Tan, J. (2001). Innovation and risk-taking in a transitional economy: A comparative study of Chinese managers and entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 16 (4), 359–376. doi:10.1016/S08839026(99)00056-7

Tan, J., Tan, Z., and Chan, K. C. (2021). Does air pollution affect a firm’s cash holdings? Pacific-Basin Finance J. 67, 101549. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2021.101549

Tan, Z., and Yan, L. (2021). Does air pollution impede corporate innovation? Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 76, 937–951. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2021.07.015

Tang, C., and Dou, J. (2021). The impact of heterogeneous environmental regulations on location choices of pollution-intensive firms in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 799449. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.799449

Teodósio, J., Vieira, E., and Madaleno, M. (2021). Gender diversity and corporate risk-taking: A literature review. Manag. Financ. 47 (7), 1038–1073. doi:10.1108/MF-11-2019-0555

Tran, Q. T. (2019). Economic policy uncertainty and corporate risk-taking: International evidence. J. Multinatl. Financial Manag. 52–53, 100605. doi:10.1016/j.mulfin.2019.100605

Vural-Yavas, C. (2020). Corporate risk-taking in developed countries: The influence of economic policy uncertainty and macroeconomic conditions. J. Multinatl. Financial Manag. 54, 100616. doi:10.1016/j.mulfin.2020.100616

Wan, J., Pu, Z., and Tavera, C. (2022). The impact of digital finance on pollutants emission: Evidence from Chinese cities. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-18465-4

Wang, F., Cai, W. X., and Elahi, E. (2022a). Do green finance and environmental regulation play a crucial role in the reduction of CO2 emissions? An empirical analysis of 126 Chinese cities. Sustainability 13 (23), 13014. doi:10.3390/su132313014

Wang, F., and Wu, M. (2020). Does air pollution affect the accumulation of technological innovative human capital? Empirical evidence from China and India. J. Clean. Prod. 285, 124818. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124818

Wang, K. L., Zhu, R. R., and Cheng, Y. H. (2022b). Does the development of digital finance contribute to haze pollution control? Evidence from China. Energies 15 (7), 2660. doi:10.3390/en15072660

Wang, L., Dai, Y., and Kong, D. (2021). Air pollution and employee treatment. J. Corp. Finance 70, 102067. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.102067

Wang, Z. (2022). Digital finance, financing constraint and enterprise financial risk. J. Math. 2882113, 1–9. doi:10.1155/2022/2882113

Wen, F., Li, C., Sha, H., and Shao, L. (2021). How does economic policy uncertainty affect corporate risk-taking? Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 41, 101840. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2020.101840

Xing, C., Zhang, Y., and Tripe, D. (2021). Green credit policy and corporate access to bank loans in China: The role of environmental disclosure and green innovation. Int. Rev. Financial Analysis 77, 101838. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101838

Xue, S., Zhang, B., and Zhao, X. (2021). Brain drain: The impact of air pollution on firm performance. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 110, 102546. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102546

Yan, X., Zhang, Y., and Pei, L. L. (2021). The impact of risk-taking level on green technology innovation: Evidence from energy-intensive listed companies in China. J. Clean. Prod. 281, 124685. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124685

Yang, L., Wang, L., and Ren, X. (2022). Assessing the impact of digital financial inclusion on PM2.5 concentration: Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 22547–22554. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-17030-3

Yang, L., and Zhang, Y. (2020). Digital financial inclusion and sustainable growth of small and micro enterprises — evidence based on China’s new third board market listed companies. Sustainability 12 (9), 3733. doi:10.3390/su12093733

Yang, Y., Su, X., and Yao, S. (2021). Nexus between green finance, fintech, and high-quality economic development: Empirical evidence from China. Resour. Policy 74, 102445. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102445

Zhang, F., Li, Y., Li, Y., Xu, Y., and Chen, J. (2022a). Nexus among air pollution, enterprise development and regional industrial structure upgrading: A China's country panel analysis based on satellite retrieved data. J. Clean. Prod. 335, 130328. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.130328

Zhang, G., Ren, Y., Yu, Y., and Zhang, L. (2022b). The impact of air pollution on individual subjective well-being: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 336, 130413. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130413

Zhang, L., Peng, L., and He, K. (2021a). Does air pollution affect executive pay? China J. Account. Stud. 9 (2), 247–267. doi:10.1080/21697213.2021.1992938

Zhang, W., Zhang, M., Wu, S., and Liu, F. (2021b). A complex path model for low-carbon sustainable development of enterprise based on system dynamics. J. Clean. Prod. 321, 128934. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128934

Zhang, Z., Su, Z., Wang, K., and Zhang, Y. (2022c). Corporate environmental information disclosure and stock price crash risk: Evidence from Chinese listed heavily polluting companies. Energy Econ. 112, 106116. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106116

Zhao, H., Yang, Y., Li, N., Liu, D., and Li, H. (2021). How does digital finance affect carbon emissions? Evidence from an emerging market. Sustainability 13 (21), 12303. doi:10.3390/su132112303

Zhao, L., and Wang, Y. (2022). Financial ecological environment, financing constraints, and green innovation of manufacturing enterprises: Empirical evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 891830. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.891830

Zhou, A., and Li, J. (2021). Air pollution and income distribution: Evidence from Chinese provincial panel data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 8392–8406. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-11224-x

Zhou, Z., Liu, L., Zeng, H., and Chen, X. (2018). Does water disclosure cause a rise in corporate risk-taking? — evidence from Chinese high water-risk industries. J. Clean. Prod. 195, 1313–1325. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.001

Keywords: air pollution, company risk-taking, digital finance, financing constraint, moderating effect, panel data

Citation: Li X and Yang Y (2022) The relationship between air pollution and company risk-taking: The moderating role of digital finance. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:988450. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.988450

Received: 07 July 2022; Accepted: 25 July 2022;

Published: 17 August 2022.

Edited by:

Yunfeng Shang, Zhejiang Yuexiu University of Foreign Languages, ChinaReviewed by:

Rendao Ye, Hangzhou Dianzi University, ChinaYunpeng Sun, Tianjin University of Commerce, China

Mengya Chen, University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Li and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ye Yang, eWFuZ3llMTlAc2RqenUuZWR1LmNu

Xiuping Li1

Xiuping Li1 Ye Yang

Ye Yang