- 1Institute of Industrial Economics, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China

- 2School of Finance and Economics, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China

- 3Department of Business Administration, Sukkur IBA University, Sukkur, Pakistan

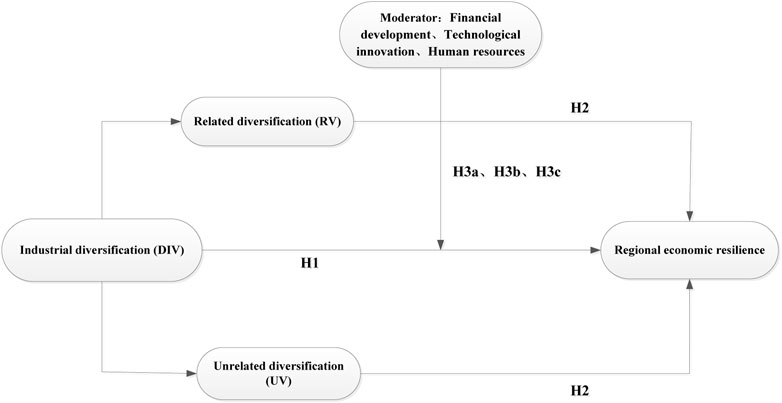

Strengthening economic resilience is the key to stable economic growth in various regions. Previous studies have paid more attention to the level and evolution trend of economic resilience, and seldom Dissected the reasons for differences in regional economic resilience. This paper takes 243 cities in China as the research object and explains the reasons for the differences in regional economic resilience from the perspective of industrial diversification. The results show that industrial diversification helps to improve the level of regional economic resilience. Compared with related diversification, unrelevant diversification has a more significant effect on economic resilience. The region’s own endowment conditions will also affect the effect of industrial diversification on economic resilience. Diversified industries can better promote regional economic resilience in more economically developed cities. The development of industrial diversification also depends on the support of external factors such as finance, technological innovation, and human capital. Therefore, increasing the investment in these factors will also help to positively adjust the role of industrial diversification in promoting economic resilience. Our research helps to understand the reasons for the formation of regional economic resilience, and the research results provide a scientific basis for optimizing sustainable development policies.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the frequent occurrence of external shocks has led to a continuous increase in economic uncertainty, and improving economic resilience has become an important practical issue for all regions. Research on economic resilience has received extensive attention from all walks of life, and its concept is also constantly enriched. Economic resilience is not just an economy’s ability to withstand shocks and recover quickly (Caldera Sanchez et al., 2016) but also an economy’s ability to adapt to environmental changes and constant change (Simmie and Martin, 2010). Regions with stronger economic resilience readjusted their own structures after the shock and achieved faster development, while regions with weaker economic resilience slumped after the shock and fell into long-term economic stagnation. The actual reason for the different results is the regional differences in economic resilience.

With the continuous accumulation of relevant empirical literature, the main factors affecting regional economic resilience have gradually been revealed. One is internal factors related to the regional industrial structure, and the other is external factors such as labor skills, financial structure, and trade openness. The industrial structure is regarded as the most important factor (Boschma, 2015; Yicheol and Stephan, 2015; Rocchetta and Mina, 2019). In the long-term development process, some regions are overly dependent on the development of a certain advantageous industry. Although this “specialized” development method can exert comparative advantages and drive economic growth in a specific period, it still has many drawbacks (Martin et al., 2019). When the impact comes, once the leading industries in these regions are severely hit, sustaining the original growth pattern may be difficult, resulting in the stagnation of economic growth in the entire region. With the continuous advancement of industrialization, the industrial division and layout of more and more regions have been further refined, and the regional industrial structure has also changed from simplification and specialization to diversification. The diversified industrial structure positively affects regional economic development, promoting factor flow, knowledge spillovers, and accelerating innovation output (Tavassoli and Carbonara, 2014). However, there is still a lack of in-depth research on the impact of economic resilience. A small amount of research on industrial diversification and economic resilience mainly focuses on the coping ability of one or several specific regions under risk shocks, which is not conducive to summarizing more general laws.

China has more than 200 cities, almost all undergoing rapid industrialization, and the industrial structure of the cities is also diversified to varying degrees. Therefore, taking more than 200 cities in China as the research object is more conducive to exploring the general laws of industrial diversification development and economic resilience evolution. Based on this, this paper attempts to address the following questions: In an uncertain economic environment, are diversified industries conducive to strengthening regional economic resilience? Comparing related and irrelevant diversification, which form of diversification is more conducive to improving regional economic resilience? Can the investment of industrial elements such as innovation, finance, and talents further strengthen the impact of industrial diversification on economic resilience? The possible contributions of this paper are: 1) The time span of the data samples in this paper covers the defense and recovery periods before the financial crisis and the impact of the financial crisis. The long time span can better analyze the general effect of industrial diversification on economic resilience. 2) Divide industrial diversification into related diversification and unrelated diversification, and deeply examine the impact of related and irrelevant diversification on economic resilience, as well as the heterogeneity in different regions and different time periods; 3) Different from the existing There are studies, and this paper also considers the moderating role of key externalities such as finance, technological innovation, and human capital to provide more perspectives for enriching economic resilience and strengthening policies.

2 Hypotheses development

2.1 Industrial diversification and regional economic resilience

The concept of resilience, which was derived from physics in the 19th century, has experienced three stages of evolution: engineering resilience, ecological resilience, and evolutionary resilience. Engineering and ecological resilience pursue the system’s equilibrium state (Holling, 1973; Holling, 1996). The economic system constantly evolves, and economic development does not always remain balanced. Davoudi et al. (2012) proposed examining evolutionary resilience from the perspective of system evolution. In recent years, scholars, to “improve economic resilience,” have conducted an increasing number of studies on how countries or regions seek stable and high-quality development in the face of complex shocks, interpreting the connotations and characteristics of economic resilience (Nystrom K, 2017; Doran & Fingleton, 2018). Regarding industrial diversification and economic resilience, most studies find that regional industrial structure is closely related to resistance and recovery (Martin et al., 2016; Doran & Fingleton, 2018; Rocchetta & Mina, 2019). Industrial structure diversification is conducive to spreading external risks and coping with external shocks (Petrackos & Psycharis, 2016), while industrial structure adjustment improves regional economic resilience (Zhang et al., 2021). Xu & Deng (2020) compared 230 prefecture-level cities in China and found that after the 2008 financial crisis, while each city’s economic resilience differed significantly, it was stronger in those with diversified industrial structures. Evans and Kaercha (2014), Brown and Greenbaum (2017), and other scholars focused on a single city as the research object and found that traditional specialized agglomeration methods lead to regional economic vulnerability, while a diversified industrial structure can reduce the losses caused by a crisis and maintain the robustness of regional economic growth.

The positive effect of industrial diversification on economic resilience manifests itself in various ways. First, industrial diversification can spread risk, reduce the instability of economic development, and act as an automatic stabilizer. Regions with a single industrial structure or that are overly dependent on a certain industry and its upstream and downstream sectors will experience violent fluctuations and be adversely affected when faced with strong shocks. Meanwhile, the various industry types, trade orientations, and market environments comprising diversified industrial structures face different risks, so when a shock occurs, they can reduce systemic risk (Xu and Deng, 2020). Moreover, a diversified industrial structure can better adjust to changes and efficiently allocate resources after a crisis, thus showing more sustainable resilience.

Second, a diverse industrial structure can promote external spillovers, driving economic innovation. The Jacobs externality theory states that knowledge spillovers are likelier to occur when complementary industries are located in the same region (Jacobs, 1969). Boschma and Iammarino (2009) believe that the exchange and dissemination of knowledge occur more often in industries with closer technological and cognitive distance. A single regional industrial structure is neither conducive to technological spillovers nor the creation of an innovative atmosphere. At the same time, regions with diverse industries can encourage the exchange of knowledge and information between sectors and offer more opportunities for technological choices, thus promoting innovation activities (Wan et al., 2019). When an economy experiences a shock, a diversified industrial structure can provide enterprises with more technological choices and reduce the adverse impact of the crisis. During the recovery and adjustment period after the shock, diversified industries can introduce new technologies, find new opportunities faster, reinforce the need for corporate innovation, and enter a new stage of development comparatively quickly, reflecting strong economic resilience.

Finally, industrial diversification can also promote the flow of labor and the ability to match it to the correct industry. During the post-shock adjustment and recovery period, the focus is on high-efficiency reemployment. Diversity can reduce frictional unemployment and instability (Brown & Greenbaum, 2017). Diversified industries provide various potential employment opportunities, and the labor force’s skills continue to improve as the industry upgrades. With the ability to perform different jobs, the labor force can be effectively utilized. Therefore, when subjected to external shocks, the regional diversification of industries increases, reducing labor-switching costs and employment volatility while allowing production to continue.

H1: A positive correlation between industrial diversification and regional economic resilience exists. Industrial diversification is conducive to regional economic resilience.

Scholars have also explored the relationship between industrial diversification methods and regional economic resilience, often comparing the diversification of related industries and unrelated industries. Relevant diversification refers to diversification among sub-industries with clear complementary or technological substitutability characteristics, while unrelated diversification refers to industrial diversity that does not exhibit these traits. Bishop (2019), Boschma and Iammarino (2009) and Xu and Deng (2020) have found that related diversification is conducive to promoting innovation activities and has a more significant role in promoting regional economic resilience. Williams et al. (2014) and Holm & Østergaard (2015) have demonstrated that related diversification can promote positive externalities, including employment and growth. Relevant diversification assists in exchanging information, knowledge, and resources in the industrial chain, creating comparative advantages. Similar technologies can be used as links to promote the generation of new technologies to cope with adverse shocks and achieve economic growth (Neffke et al., 2011). The related diversified industries are mostly complementary. Knowledge flows more conveniently and efficiently in highly related sectors, and knowledge spillovers can occur between industries at a lower cost, thus providing valuable resources for innovation and promoting technology diffusion and innovation. Behaviors that increase productivity drive economic growth (Wan et al., 2019). However, when external shocks occur, related diversification may be more easily implicated, because regions with a high degree of relative diversification may experience a decline in upstream and downstream industries due to the deterioration of one industry; they may be less resilient to adverse shocks (Xu & Wang, 2017).

Unrelated industry portfolios can diversify external risks and function as automatic stabilizers; in cities with a high level of irrelevant diversity, a specific industry may shock but not disrupt the entire regional economy. Although unrelated diversification lacks technical correlation, the cross-integration of different sectors can promote collaboration, and talent exchanges can generate new ideas. Unrelated diversification may improve regional economic resilience by promoting portfolio effects (Sun & Chai, 2012), disruptive innovation (Castaldi et al., 2015), and new economic innovation (Xu & Deng, 2020). Regardless of regions with a high degree of diversification, the negative impact of a specific industry is not easily spread across industries, and the possibility of resource reallocation is higher when entering a recovery period (Kemeny & Storper, 2015). Regardless of diversification, different industries maintain different unemployment cycles in the face of shocks, and the diversity of unrelated industries also brings a variety of employment opportunities, reducing labor costs and making up for the employment gap (Sun & Chai, 2012).

H2: Unrelated diversification has a more positive effect on regional economic resilience than related diversification.

2.2 The moderating role of financial development, technological innovation, and human resources

The development of the industry is never isolated. The actual economy, with industry at its core, cannot be separated from the collaborative support of human resources, modern finance, and technological innovation (Liu and Ren, 2020). Scholars have recently examined the relationship between these industrial factors and regional economic resilience. Zheng and Qi (2022) have demonstrated that the ability of finance to absorb savings and share risks can improve economic resilience. Jennifer et al. (2010), Simmie (2014), and Cheng and Jin (2022) have pointed out that the long-term development of the regional innovation system helps improve innovation capabilities, which in turn can further strengthen regional economic resilience. Ge et al. (2022) also pointed out that technological innovation is crucial to increasing income and maintaining the smooth operation of the economy in the impact of the new crown epidemic, Liu et al. (2022) also believe that entrepreneurs with innovative behaviors have a greater chance of survival after the crisis. Marloes et al. (2015) and Zhu and Sun (2021) have shown that high-quality human resources capital is conducive to refining resource allocation efficiency, thereby enhancing cities’ resistance and resilience in response to crises.

Finance allocates the capital that funds all aspects of economic operations (Cui, 2021). Financial development refers to expanding financial activities and optimizing financial instruments and institutions (Han et al., 2021). A sound financial market can improve the efficiency of resource allocation and diversify risks. In cities with a high level of financial development, information asymmetry between industries can be effectively alleviated, and the exchange and dissemination of information and knowledge among industries are more effective and convenient. In the face of shocks, companies rely on the financial sector to reallocate resources, resume production, and upgrade industrial structures during recovery (Martin et al., 2016). Cities with high levels of financial development can broaden adversely affected enterprises’ financing channels, ease their financing constraints, and promote continuous production and innovation, which positively impacts the resilience of the regional economy.

H3a: In cities with a high level of financial development, industrial diversification has a more significant effect on the resilience of the regional economy.

Innovation is the main driving force of the modern industrial system, leading and supporting economic development and enabling structural upgrades and optimization (Cheng and Jin, 2022). Areas with high innovation capabilities can spawn new technologies and emerging industries, and the cross-integration of different industries can generate breakthrough innovations (Bishop, 2019). Technological progress brought about by innovation can increase input-output efficiency and optimize resource allocation, thereby enhancing economic resilience. Against the backdrop of an uncertain and unstable global economy, technological innovation has played a huge role in coping with the decoupling of the China-US economy and the adverse effects of COVID-19. In the face of external shocks, cities with strong innovation abilities experience lower exchange costs between industries and find it easier to discover new opportunities and new technologies. In the recovery period, such cities can break the original development path (Bristow and Healy, 2018), more readily reallocate resources, upgrade and transform the industry, and encourage the incubation and growth of new enterprises and production activities. Regions with stronger innovation capabilities can take advantage of new comparative advantages and enter new growth paths (Martin et al., 2015), thus showing strong resilience.

H3b: In cities with a high level of technological innovation, the effect of industrial diversification on the resilience of the regional economy is more pronounced.

Human resources are the guarantee of a modern industrial system. The development of the urban economy is inseparable from the accumulation of human capital. Human resources can promote economic growth by affecting the formation of productivity and other factors of production. High-quality human resources can stabilize fluctuations by increasing domestic demand after experiencing external shocks (Marloes et al., 2015). Cities with high levels of human resources can transfer information and knowledge between industries more efficiently. In addition, it enhances technical reserves and knowledge accumulation; high levels of human resources encourage competition, prompting labor force members to increase their knowledge reserves and competitiveness (Han et al., 2021), which leads to economic development. Abundant human capital can stabilize domestic demand and act as a shock absorber (Zhu and Sun, 2021). In the face of adverse external shocks, improving human capital allows for a better match between the primary labor force and the primary industry. During the recovery period, cities with high levels of human resources can produce and innovate faster and more efficiently, thus demonstrating strong resilience.

H3c: In cities with a high level of human resources, the effect of industrial diversification on regional economic resilience is more pronounced.

Figure 1, demonstrate the mechanism diagram of this paper.

3 Methodology

3.1 Model settings

Based on the theoretical mechanism and research assumptions, we construct the following benchmark model to investigate the effect of industrial diversification on economic resilience improvement and use the ols method to estimate the model (Frenken et al., 2007; Wang and Wei, 2021):

Where i and t are city and time, respectively; rccit is economic resilience and the explained variable takes the logarithmic form of rcc; DIVit is industrial diversification; Xit is the control variable; and

In order to verify Hypotheses 3a, b, and c, we add three moderator variables: financial development, technological innovation, and human resources, as well as the multiplication term of moderator variables and industrial diversification based on basic regression (Han et al., 2021):

Where Zit is the three adjustment variables.

3.2 Variable description

3.2.1 The explained variable

The explanatory variable, regional economic resilience, is derived from the work of Zhao and Wang (2021). We calculate the difference between the actual GDP growth rate of each prefecture-level city in 2008 and the GDP growth rate of 2008 and convert negative values to positive values. The larger the difference, the smaller the economic resilience. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

Where rdvalue is the difference between the annual real GDP growth rate and the 2008 GDP growth rate, the logarithmic form of economic resilience (lnrcc) is included in the model.

3.2.2 Core explanatory variables

The core explanatory variable is industrial diversification. In the existing literature, the entropy index is used to measure industrial diversification (Xu and Zhang, 2019):

Where DIV is the level of industrial diversification and Pi is the proportion of employees engaged in the small industry i to employment in the region. Generally, the larger the index, the higher the level of industrial diversification. The index value is zero in extreme cases where the city has only one industry. If it is assumed that there are n sub-industries distributed in Q (Q < n) major industries in a certain region, the employment proportion of the major industries (q = 1, 2, 3, .., Q) is the sum of employment proportion in covered small industries, thereby decomposing industrial diversification into related diversification and unrelated diversification. The specific decomposition process is as follows:

Where RV is related to diversification, and UV is unrelated diversification.

The data used to calculate industrial diversification is pulled from 19 industries in the China Urban Statistical Yearbook. Referring to Sun and Chai’s (2012) industry classification method based on three industry divisions, we categorize 19 small industries into six major industries. Agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery are the primary industries; mining, manufacturing, electricity and heat, and construction are the secondary industries; wholesale and retail, transportation, and information software services in the tertiary industry are circulation services; finance, real estate, leasing, and service industries are producer services; accommodation and catering, residential services, culture, and sports and entertainment are consumer services; scientific research comprehensive services, water conservancy environment and public facilities services; education, health and social security, social welfare, and public management and security are social service industries.

3.2.3 Moderators

1) Financial development: The city’s deposit and loan balance ratio to regional GDP.

2) Technological innovation: The number of patent authorizations.

3) Human resources: Number of undergraduate and junior college students.

3.2.4 Control variables

1) Market size: It is generally believed that economies with large market sizes can better withstand the adverse effects of external shocks and recover faster (Christopherson et al., 2010). We use the total retail sales of social consumer goods to represent the market size.

2) Population density: Population density measures market size potential. The logarithm of population density functions as a proxy variable of population density.

3) Open to the outside world: Higher levels of urban openness reduce the cost of trade, increasing economic strength and enhancing economic resilience (Zhao and Wang, 2021). In this paper, the use of foreign business people expresses the degree of openness to the outside world.

4) Government participation: When an area experiences a shock, government fiscal spending in the region raises resilience to a certain extent and enables economic recovery. The ratio of regional fiscal expenditure to regional GDP indicates the degree of government participation.

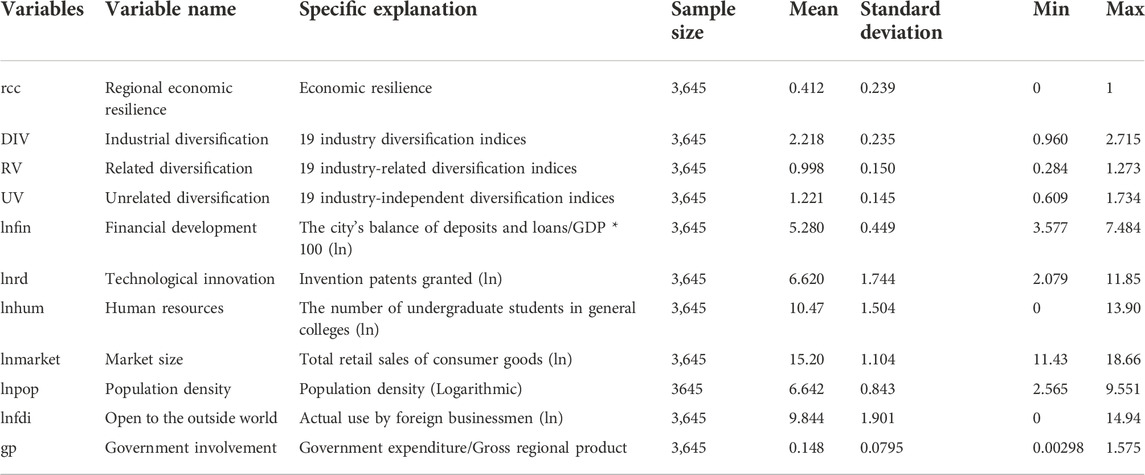

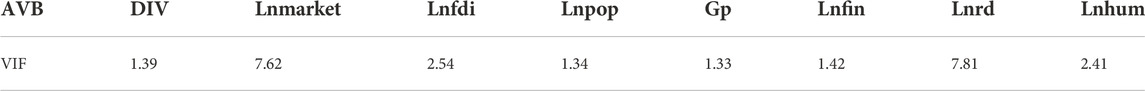

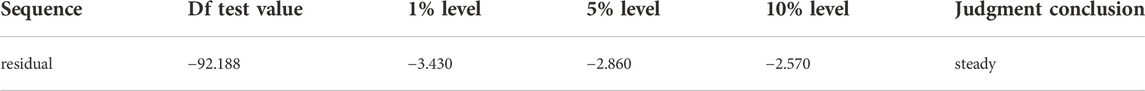

5) Data sources and descriptive statistics: We use panel data from 243 Chinese prefecture-level and above cities gathered from 2004 to 2018. The number of patent authorizations are collected from the State Patent Office. Other explanatory variable data are from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook and each city’s statistical yearbook. A few missing data are filled by interpolation. The description of each variable is shown in Table 1. Tables 2, 3 report the variables’ VIF values and cointegration test results, respectively. The results show that the VIF value is less than 10, indicating no multicollinearity between the variables, and there is a long-term stable cointegration relationship between the explanatory variables and the explained variables.

4 Result analysis

4.1 Regression results

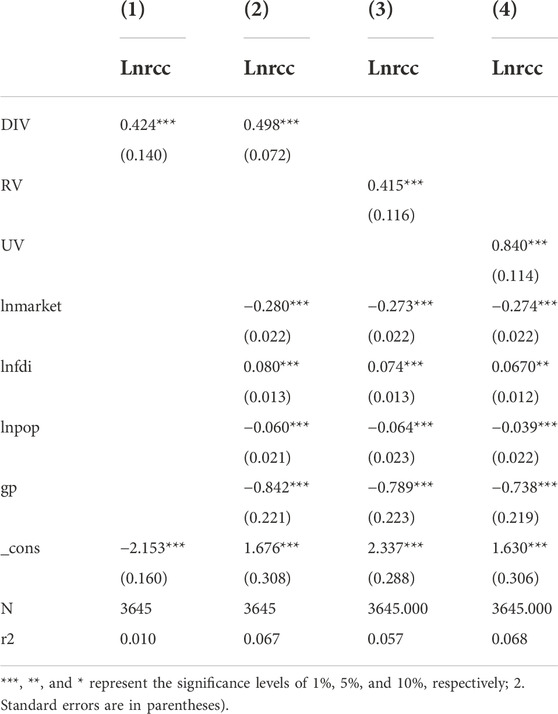

We adopt a fixed-effect model to perform basic data regression. The regression results are shown in Table 4. R2 refers to the degree of fit. The first column shows the regression results without adding the control variables. Industrial diversification positively affects economic resilience and is significant at the 1% level, with an average increase of 0.424%. Columns 2 to 4 are regression results with control variables added. After adding the control variables, industrial diversification continues to significantly affect regional economic resilience. When industrial diversification increases by one unit, on average economic resilience increases by 0.498%, which shows that industrial diversification can improve economic resilience. Cities with diversified industries can function as automatic stabilizers in the face of shocks, dispersing the risks; diversified industries can also promote innovation activities and industrial structure upgrades and transformation through knowledge exchange and spillover. Diversified industries allow China to construct a strong foundation to upgrade its vast array of industries in an increasingly uncertain economic environment, leading to self-repair and strong resilience.

Column 3 reveals the impact of related diversification on economic resilience, which is positive at the1% level. A unit of unrelated diversification increases economic resilience by an average of 0.415%. Column 4 shows the impact of unrelated diversification on economic resilience, which is positive at the 1% level. A unit of unrelated diversification increases economic resilience by an average of 0.840%. The coefficient of irrelevant diversification is Dada higher than that of correlated diversification, which is consistent with the previous theoretical analysis, cities with a high level of unrelated diversification are better able to maintain economic stability in the face of fluctuating external environments than those with related diversification, thus exhibiting stronger resilience. When shocks are unrelated to a specific industry in a city with a high degree of diversity, the negative impact is not easily spread among industries, and the reallocation of resources is relatively high. The disruptive innovation generated by the integration of different industries can generate new technologies and new economies, which allow for more room for maneuvering in an unstable environment, and can enter a new growth path that strengthens resilience.

4.2 Robustness check

4.2.1 Substitute core explanatory variables

In addition to using DIV to indicate industrial diversification, the reciprocal HHI can also measure the diversified industrial agglomeration index (Jacobs). We use the improved Hirschman-Herfindahl index (HHI) reciprocal calculation (Hong and Gu, 2016) and the calculation method is as follows:

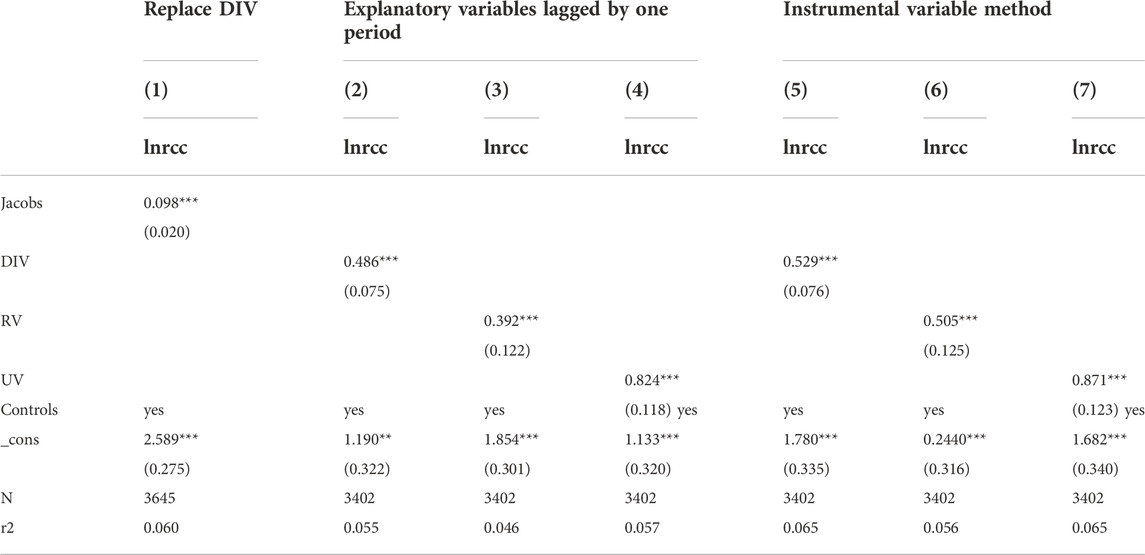

Where Jacobsit is the level of industrial diversification and agglomeration in city i in year t; ISitj is the ratio of industry employment j in city i to total employment in the city in year t; IStj is industry employment j in the country in year t as a percentage of the total employment in the country. The regression results are shown in Table 5. After replacing the core explanatory variables, the Jacobs coefficient is positive and significant, indicating that the basic conclusions remain unchanged and the results are robust.

4.2.2 Endogenous test

Endogeneity issues may appear in the benchmark regression of the model, including the omission of individual and time-variant factors on economic resilience. To eliminate such errors, the core explanatory variables and control variables are lagged by one period. Whether an economy can withstand a shock and recover faster depends on past economic conditions, and a one-period lag of explanatory variables can also solve the endogeneity problem. As shown in Table 5, the coefficients of industrial diversification, related diversification, and unrelated diversification are all significantly positive when the variables are lagged. This shows that the role of diversified industries in improving economic resilience is continuous. The Jacobs coefficient is positive and passes the significance test, indicating that after replacing the core explanatory variables, the basic conclusion remains unchanged, and the result is robust.

In addition to lagging variables by one period, the instrumental variable method can also address endogeneity. This paper uses the lagged one period of industrial diversification, related diversification, and unrelated diversification as instrumental variables to estimate the model. The estimation results show that industrial diversification significantly positively affects economic resilience. The improvement in the level of economic resilience is related diversification, and the basic conclusions of the instrumental variable method estimation remain unchanged, indicating that our conclusions are robust.

4.3 Heterogeneity test

4.3.1 Locational heterogeneity

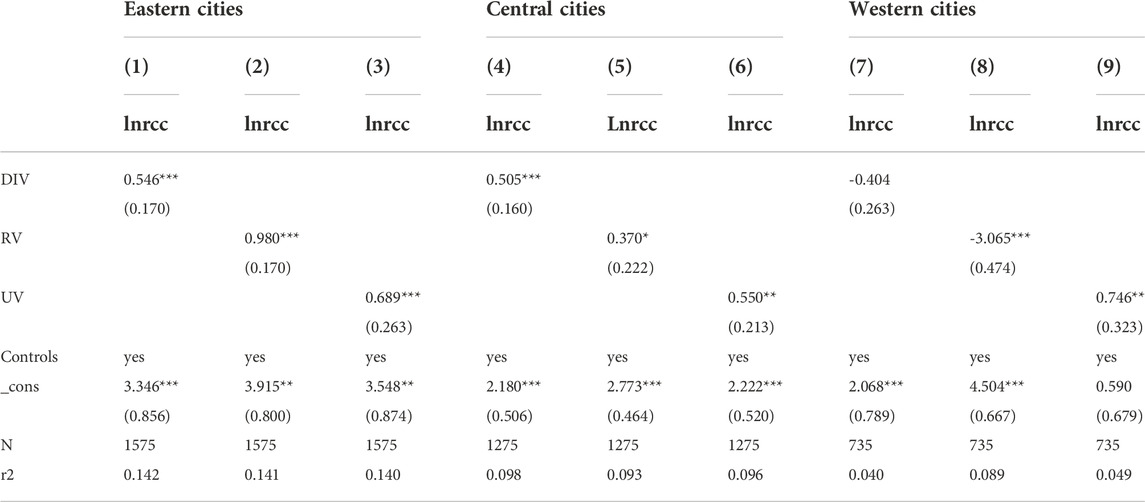

Depending on location, industrial diversification levels vary from city to city, and economic resilience in the face of external shocks will also differ. Therefore, to more comprehensively understand the impact of different cities’ industrial diversification levels on economic resilience, we categorize Chinese urban areas into eastern, central, and western cities according to their locations. The empirical results are shown in Table 6.

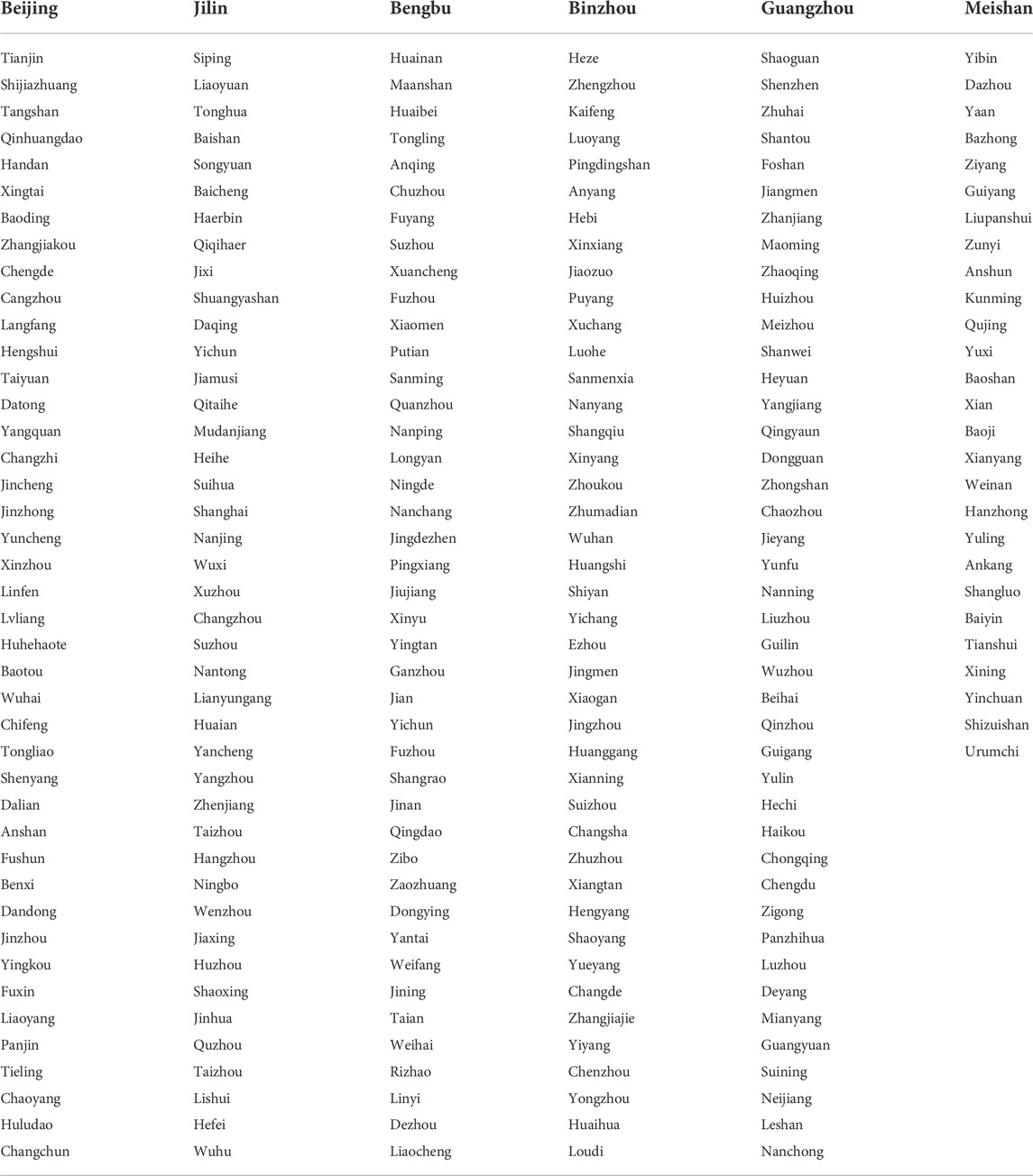

Columns 1, 2, and 3 of Table 6 are the estimation results of eastern cities, columns 4, 5, and 6 are the estimation results of central cities, and columns 7, 8, and 9 are the estimation results of western cities. The results show that the industrial diversification of central and east cities has a significantly positive impact on economic resilience and that the impact is higher in eastern cities. Both related and unrelated diversification in eastern cities has significantly improved economic resilience. Although the related diversification and unrelated diversification in central cities significantly affect economic resilience, the improvement effect is smaller than that in eastern cities. The impact of industrial diversification in western cities on economic resilience is significantly negative, and related diversification significantly affects their economic resilience. Most western regions are characterized by low development levels with related industrial diversification comprised mainly of traditional industries. On the other hand, the industries in the eastern and central cities are mostly capital- and technology-intensive, with strong diversification externalities, relatively lower costs for integration and exchange between industries, and stronger support for economic resilience. Overreliance on a certain industry and related industries reverses the stabilizing effect of diversification in Appendix illustrate the list of cities (refer to Table A1).

4.3.2 Temporal heterogeneity

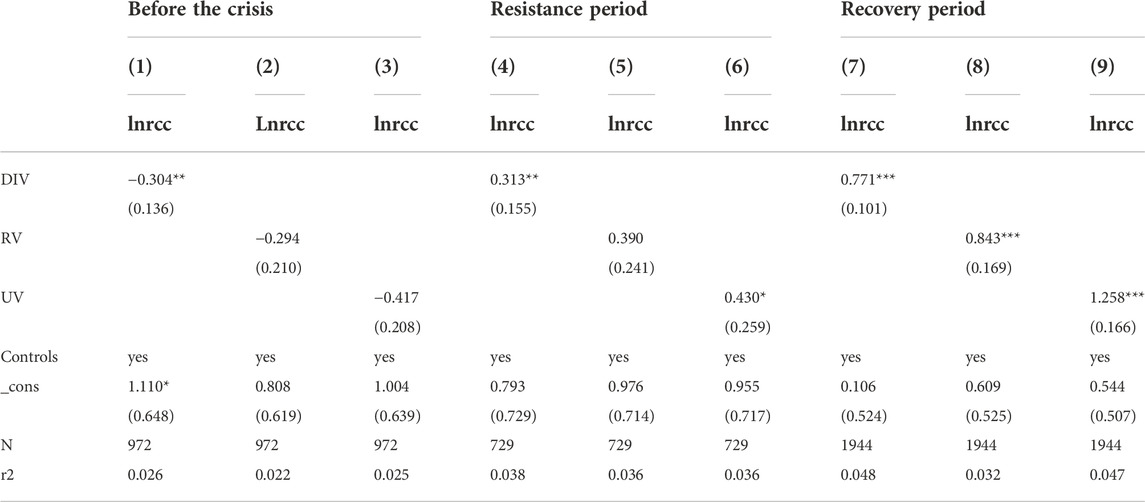

The economic resilience level includes resilience to shocks and resilience aftershocks. Therefore, the effect of urban industrial diversification on economic resilience differs depending on the time period. Using Martin and Sunley (2015) classification method, 2004–2007 is the period before the financial crisis, 2008–2010 is the resistance period, and 2011–2018 is the recovery period. The regression results are shown in Table 6.

Columns 1, 2, and 3 of Table 7 reflect the periods before the financial crisis, columns 4, 5, and six are periods of resistance, and columns 7, 8, and 9 are periods of recovery. It is clear that before the financial crisis, the impact of industrial diversification on economic resilience was significantly negative. This may be because the economic development level of many cities was relatively low during 2004–2007. The agglomeration of industrial specialization helps strengthen comparative advantage and the connection and competition between enterprises, thereby promoting economic growth. During this period, diversified industries typically do not grow rapidly, nor do they enjoy economic stability, so the impact on economic resilience is negative. After the financial crisis, industrial diversification had a significant positive effect on economic resilience, and the effect was even more pronounced during the recovery period. Unrelated diversification during the resistance period has a positive effect on economic resilience, while related diversification is not significant; both related and unrelated diversification significantly impact economic resilience during the recovery period. When a shock occurs, diversified industries can spread risks and thus exhibit strong resilience. Cities with a high level of related diversification contain primarily upstream and downstream industries. The entire industrial chain is often affected, leading to lower resilience levels than cities with high levels of unrelated diversification. During the recovery period, an industry’s recovery may lead to the recovery of its upstream and downstream industries. Therefore, related diversification can significantly improve economic resilience during the recovery period.

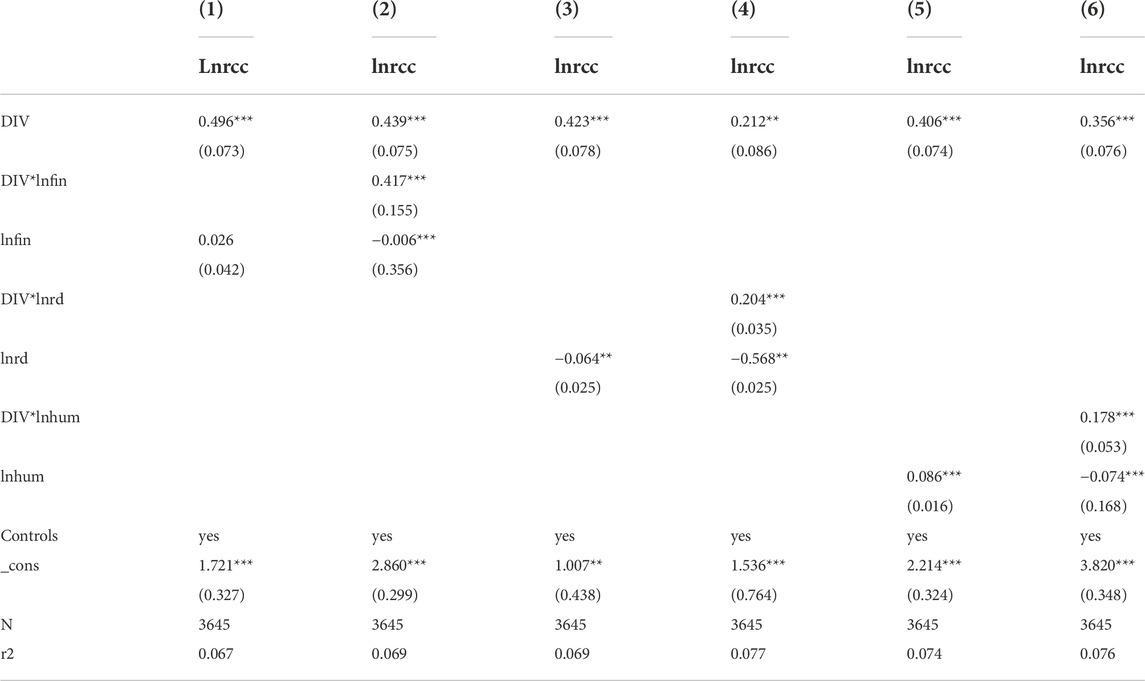

4.4 Moderating effect test

This paper focuses on the impact of industrial diversification on economic resilience levels. While industrial diversification has a heterogeneous effect on economic resilience, the development of the industry is inseparable from finances, technology, and labor. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the adjustment role of these three elements, examining the regulatory roles of financial development, technological innovation, and human resources.

Columns 1, 3, and 5 of Table 8 show the regression results without the addition of the multiplication term, while columns 2, 4, and 6 display the regression results with the addition of the multiplication term. The multipliers of moderator variables and industrial diversification all passed the positive significance test; financial development, technological innovation, and human resources all have positive moderating effects on industrial diversification, improving economic resilience levels. This confirms our hypotheses. Structural upgrades are inseparable from financial development, and efficient capital flow can help enterprises resist shocks. Cities with high levels of innovation can find new opportunities faster when the external environment is turbulent and promote industrial upgrades and transformation. High-quality human capital builds knowledge, improving factor allocation efficiency, which maintains smooth economic operations. In the face of external shocks, the level of financial development, technological innovation, and human capital also play a positive role. In cities with a high level of financial development, a high level of technological innovation, and high-quality human capital, the cost of information exchange between enterprises is reduced. Additionally, the reallocation of resources is more efficient in the face of external shocks, and it is easier to generate new technologies and industries. In such cities, the effect of industrial diversification on economic resilience levels is more obvious. Therefore, improving the financial system, providing an inclusive and open financial environment, strengthening innovation-driven strategies, promoting new technologies and industries, and gathering high-quality human capital is crucial to improving economic resilience.

5 Discussion

The empirical results in Table 5 show that industrial diversification significantly improves regional economic resilience. Cities with diverse industrial structures can adjust their structures more quickly, diversify risks, and thus gain greater resilience. Both related diversification and unrelevant diversification can promote economic resilience, but compared with related diversification, unrelevant diversification can promote the improvement of regional economic resilience. Diversifying industries can bring dynamism to cities, giving them more leeway in dealing with shocks. Relevant diversification can facilitate the flow between industries with more convenient resources, and the development of one industry can also drive the development of related industries. Cross-integration between different industries in cities with a high degree of irrelevance and diversity can stimulate breakthrough innovations, and new technological trajectories (Duschl, 2016). In addition, it is easier to enter new growth paths in the event of shocks, which can fluctuate in macroeconomic fluctuations. It can reduce or even avoid the chain reaction between industries during the shock or shock so as to play the risk diversification effect of the investment portfolio. Therefore, unrelated diversification can be more conducive to improving economic resilience. This conclusion also passed the robustness test.

The locational heterogeneity analysis in Table 7 shows that the industrial diversification of eastern and central cities has a significant promoting effect on the improvement of regional economic resilience, but it has an inhibitory impact on the western region. The development level of eastern and central cities is higher than that of western cities, and the externalities of diversification are more robust, which is more conducive to improving the level of resilience. The industrial diversification of western cities is not conducive to improving economic resilience. The possible reason is that the economic development level of western cities is relatively low, focusing on the development of pillar industries, and the related diversification level is higher. Therefore, when the impact comes, it may affect the upstream and downstream industries of the leading industry, which is not conducive to improving the level of regional economic resilience. Industrial diversification’s effect on improving economic resilience has reversed (Sun and Chai, 2012). The results in Table 7 show that the diversification of industries in both the resistance and recovery periods significantly promotes the improvement of regional economic resilience. Before the crisis, China’s economic development level was not high, and the development of diversified industries may lead to a lack of concentrated factor allocation, and the professional development of various regions focusing on pillar industries may be more conducive to economic development. Diversified industries during the resilience and recovery periods can spread risks and improve the resilience of the regional economy. During the resistance period, regions with a high degree of related diversification may be affected by the impact on the leading industries, resulting in all related industries being adversely affected. Therefore, the effect of improving economic resilience in the resistance period is not significant. This conclusion is consistent with previous research conclusions (Xu and Deng, 2020). Unrelevant diversification can significantly improve regional economic resilience during both the resilience and recovery phases. Other unrelated industries may be less affected when a particular industry is hit. After the crisis, cities with a high degree of unrelated diversification can resume production faster and enter a new development path. Cities with a high degree of related diversification will also drive the recovery of upstream and downstream industries due to the recovery of a specific industry, so the related diversification has a significant positive effect on improving regional economic resilience after the crisis.

The results in Table 8 show that financial development, technological innovation, and human resources all have positive moderating effects. The coordinated development of industrial elements is more conducive to improving economic resilience. When the crisis comes, all sectors need the support of the financial sector to resist risks and restore development. A sound financial market can alleviate corporate financing difficulties by optimizing resource allocation and diversifying risks (Mia et al., 2016). Small and medium-sized enterprises are relatively easy to get loans, and they can resume production faster and reduce losses in the face of shocks. A crisis creates an opportunity to accelerate technological progress and innovation, both of which are critical in driving economic stability and growth, regions with high innovation capabilities can withstand the negative impact of fluctuations in the face of complex environments, faster adjust to show strong resilience (Bristow and Healy, 2018). Regions with abundant human capital are more competitive, have more knowledge and technology reserves, and have higher income levels and spending power, which can act as shock absorbers. In addition, high-quality human capital also has higher income levels and spending power, which can stimulate domestic demand in times of crisis, thus acting as a shock absorber.

6 Conclusion and implications

6.1 Conclusion

Economic resilience is the foundation of a region’s economic growth and prosperity, and a necessary condition for sustainable development. China’s economy is in a critical transition period from high-speed growth to high-quality development. Under the new environment, more attention should be paid to improving regional economic resilience. This is very important for my country to coordinate regional development, prevent internal risks and external shocks in the system, promote the upgrading of industrial structure, and realize economic transformation and upgrading.

Many scholars have found that a diversified industrial structure can resist shocks and improve economic resilience (Eraydin, 2016; Wang and Wei, 2021). Based on previous research, our research deeply explores the impact of different diversification on economic resilience. The empirical results show that industrial diversification can improve the level of economic resilience, and the effect of unrelevant diversification on economic resilience is greater than that of related diversification. This result also passes the robustness test. We also explore how industrial diversification affects the heterogeneity of regional economic resilience. The study’s results found that the effects of industrial diversification, related diversification, and unrelated diversification on regional economic resilience were heterogeneous in different regions and time periods. This conclusion also shows that policymakers should formulate relevant policies according to the region’s development level, factor endowments, etc., according to local conditions and time conditions to improve the region’s ability to resist risks. In addition, to examine the influence of industrial synergy factors, we added three moderating variables of financial development, technological innovation, and human resources. The study found that all three moderating variables can positively moderate the effect of industrial diversification on regional economic resilience. This result also shows that the coordinated development of various industrial elements is more conducive to the stable development of the economy. Our research provides a realistic reference for optimizing the industrial structure of various regions in an uncertain environment, improving the coordinated development of various industrial elements, and enhancing the level of regional economic resilience.

6.2 Implications

The findings of this study have several policy implications:

First, China’s economy has entered a high-quality stage, and for healthy and sustainable economic development, the economic system must be resilient. The development mode that relies on a single industry to drive economic growth is no longer suitable for the requirements of sustainable economic development. Local governments should actively and orderly guide diversified industrial development throughout the country, strengthen the coordination and interaction of related industries, and reinforce their automatic stabilizer functions. Appropriately apply selective industrial policies, gradually break away from the low-level specialized agglomeration development model, lead and support industries that are horizontally related to leading local industries, cultivate emerging sectors with counter-economic cycle differences that differ from leading industries, and promote exchanges and integration between industries; Second, all localities should pay attention to the diversified development of unrelated diversification and promote more breakthrough innovations to create new innovation advantages. Each region should also balance the proportion of industry-related and irrelevant diversification based on its resource endowments and comparative advantages, supplement the resource conditions and policy supply required by unrelated industries, and strengthen cross-industry accumulation and integration. When formulating industrial policies, all regions should also adopt measures to local conditions and the times. Eastern and central cities should coordinate the coordinated development of various industries and simultaneously encourage the transfer of emerging industries to western cities, inject new vitality into the development of western cities, and improve economic resilience.

Finally, this research accelerates the development of the modern industrial system, promote the accumulation and upgrading of industrial elements such as technological innovation, human resources, and modern finance, and strengthen the construction of an environment that enhances the resilience of the regional economy. In the long run, it is also necessary to strengthen the factor supply system that matches the diversified development of the industry, enhance the coordination of the industrial reform of various departments, improve the synergy and linkage effect between industrial elements, and realize the endogenous development and independent upgrading of economic resilience driven by industrial diversification.

6.3 Limitations

Using data from 2004 to 2018, this paper examines the effect of industrial diversification on regional economic resilience. The classification of shocks in this paper is based on the 2008 financial crisis. Due to data limitations, this article does not take into account the impact of the new crown epidemic. In the follow-up research, we will incorporate the new crown epidemic as an exogenous shock into the model and conduct a more in-depth discussion on the relationship between industrial diversification and regional economic resilience.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

We acknowledge support from the National Social Science Fund General Projects of China (No. 21BTJ050) and the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71974078). The findings and observations contained in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of those providing support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bishop, P. (2019). Knowledge diversity and entrepreneurship following an economic crisis: An empirical study of regional resilience in Great Britain. Entrepreneursh. Regional Dev. 31 (5), 496–515. doi:10.1080/08985626.2018.1541595

Boschma, A., and Iammarino, S. (2009). Related variety, trade linkages and regional growth in Italy. Econ. Geogr. 85 (3), 289–311. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01034.x

Boschma, R. (2015). Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience. Reg. Stud. 49 (5), 733–751. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.959481

Bristow, G., and Healy, A. (2018). Innovation and regional economic resilience: An exploratory analysis. Ann. Reg. Sci. 60 (2), 265–284. doi:10.1007/s00168-017-0841-6

Brown, L., and Greenbaum, R. T. (2017). The role of industrial diversity in economic resilience: An empirical examination across 35 years. Urban Stud. 54 (6), 1347–1366. doi:10.1177/0042098015624870

Caldera Sanchez, A., Serres, A., Gori, F., Hermansen, M., and Röhn, O. (2016). Strengthening economic resilience: Insights from the post-1970 record of severe recessions and financial crises. OECD Econ. Policy Pap. 20, 1–30. doi:10.1787/6B748A4B-EN

Castaldi, C., Frenken, K., and Los, B. (2015). Related variety, unrelated variety and technological breakthroughs: An analysis of US state-level patenting. Reg. Stud. 49 (5), 767–781. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.940305

Cheng, G. B., and Jin, Y. (2022). Can improved innovation capacity enhance urban economic resilience? Discuss. Mod. Econ. 02, 1–11+32. doi:10.13891/j.cnki.mer.2022.02.015

Christopherson, S., Michie, J., and Tyler, P. (2010). Regional resilience: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Camb. J. Regions Econ. Soc. 1, 3–10. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsq004

Cui, G. R., Wang, J. S., and Chang, C. P. (2021). Environmental quality, corruption and industry growth: The global perspective. Probl. Ekorozwoju 43 (12), 29–37. doi:10.35784/pe.2021.1.03

Davoudi, S., Shaw, K., Haider, L. J., Quinlan, A. E., Peterson, G. D., Wilkinson, C., et al. (2012). Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? Plan. Theory Pract. 13 (2), 299–333. doi:10.1080/14649357.2012.677124

Doran, J., and Fingleton, B. (2018). US Metropolitan Area Resilience: Insights from dynamic spatial panel estimation. Environ. Plan. A 50 (1), 111–132. doi:10.1177/0308518X17736067

Duschl, M. (2016). Firm dynamics and regional resilience: An empirical evolutionary perspective. Ind. Corp. Change 25 (5), 867–883. doi:10.1093/icc/dtw031

Eraydin, A. (2016). Attributes and characteristics of regional resilience: Defining and measuring the resilience of Turkish regions. Reg. Stud. 50 (4), 600–614. doi:10.1080/00343404.2015.1034672

Evans, R., and Kaercha, J. (2014). Staying on top: Why is Munich so resilient and successful? Eur. Plan. Stud. 22 (6), 1259–1279. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.778958

Frenken, K., Van Oort, F., and Verburg, T. (2007). Related variety, unrelated variety and regional economic growth, unrelated variety and regional economic growth. Reg. Stud. 5, 685–697. doi:10.1080/00343400601120296

Ge, T., Ullah, R., Abbas, A., Sadiq, I., and Zhang, R. (2022). Women's entrepreneurial contribution to family income: Innovative technologies promote females' entrepreneurship amid COVID-19 crisis. Front. Psychol. 13, 828040–828110. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.828040

Han, L., Chen, S., and Liang, L. L. (2021). Digital economy, innovation environment and urban innovation capability. Res. Manag. 42 (4), 35–45. doi:10.19571/j.cnki.1000-2995.2021.04.004

Holling, C. S. (1996). Engineering resilience versus ecological resilience. Eng. Within Ecol. Constraints 31, 31–32.

Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 4 (1), 1–23. doi:10.1146/ANNUREV.ES.04.110173.000245

Holm, J. R., and Østergaard, C. R. (2015). Regional employment growth, shocks and regional industrial resilience: A quantitative analysis of the Danish ict sector. Reg. Stud. 49 (1), 95–112. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.787159

Hong, Q. L., and Gu, S. Z. (2016). Structural characteristics of industrial agglomeration and its impact on regional innovation performance: An empirical study based on China's high-tech industry data. Soc. Sci. Front 000 (001), 51–57. CNKI:SUN:SHZX.0.2016-01-010.

Jennifer, C., Huang, H., and Walsh, J. P. (2010). A typology of "innovation districts": What it means for regional resilience. Camb. J. Regions Econ. Soc. 1, 121–137. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsp034

Kemeny, T., and Storper, M. (2015). Is specialization good for regional economic development? Reg. Stud. 49 (6), 1003–1018. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.899691

Liu, G. F., and Ren, B. P. (2020). Construction of the modern industrial system of China's provincial and local economy in the new era. Explor. Econ. Issues 7, 81–91.

Liu, Q., Qu, X., Wang, D., and Mubeen, R. (2022). Product market competition and firm performance: Business survival through innovation and entrepreneurial orientation amid COVID-19 financial crisis. Front. Psychol. 12, 790923–791012. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.790923

Marloes, Z., Horst, A., Vuuren, D., Erken, H., and Luginbuhl, R. (2015). Long-term unemployment and the Great Recession in The Netherlands: Economic mechanisms and policy implications. De. Econ. 163 (4), 415–434. doi:10.1007/s10645-015-9263-y

Martin, An., Johan, P., and Joakim, W. (2019). The economic microgeography of diversity and specialization externalities-firm-level evidence from Swedish cities. Res. Policy 48 (6), 1385–1398. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2019.02.003

Martin, R., Sunley, P., Gardiner, B., and Tyler, P. (2016). How regions react to recessions: Resilience and the role of economic structure. Reg. Stud. 50 (4), 561–585. doi:10.1080/00343404.2015.1136410

Martin, R., and Sunley, P. (2015). On the notion of regional economic resilience: Conceptualization and explanation. J. Econ. Geogr. 15, 1–42. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbu015

Martin, R., Sunley, P., and Tyler, P. (2015). Local growth evolutions: Recession, resilience and recovery. Camb. J. Regions, Econ. Soc. 8, 141–148. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsv012

Mia, M. A., Nasrin, S., and Cheng, Z. (2016). Quality, quantity and financial sustainability of microfinance: Does resource allocation matter? Qual. Quant. 50 (3), 1285–1298. doi:10.1007/s11135-015-0205-1

Neffke, F., Henning, M., and Boschma, R. (2011). How do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of new growth paths in region. Econ. Geogr. 87 (3), 237–265. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

Nystrom, K. (2017). Regional resilience to displacements. Reg. Stud. 1, 4–22. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1262944

Petrackos, G., and Psycharis, Y. (2016). The spatial aspects of economic crisis in Greece. Econ. Soc. 9, 137–152. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsv028

Rocchetta, S., and Mina, A. (2019). Technological coherence and the adaptive resilience of regional economies. Reg. Stud. 53 (10), 1421–1434. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1577552

Simmie, J., and Martin, R. (2010). The economic resilience of regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Camb. J. Regions, Econ. Soc. 3 (1), 27–43. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsp029

Simmie, J. (2014). Regional economic resilience: A schumpeterian perspective. RuR. 72 (2), 103–116. doi:10.1007/s13147-014-0274-y

Sun, X. H., and Chai, L. L. (2012). Relevant diversification, irrelevant diversification and regional economic development: An empirical study based on panel data of 282 prefecture-level cities in China. China's Ind. Econ. 6, 5–17. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2012.06.001

Tavassoli, S., and Carbonara, N. (2014). The role of knowledge variety and intensity for regional innovation. Small Bus. Econ. 43 (2), 493–509. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9547-7

Wan, D. X., Hu, B., and Li, Y. (2019). Relevant diversification, irrelevant diversification and urban innovation: An empirical study based on panel data of 282 prefecture-level cities in China. Financial Sci. 5, 56–70. CNKI:SUN:CJKX.0.2019-05-006.

Wang, Z. X., and Wei, W. (2021). Regional economic resilience in China:measurement and determinants. Reg. Stud. 17, 1228–1239. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1872779

Williams, N., Vorley, T., and Ketikidis, P. H. (2014). Economic resilience and entrepreneurship: Lessons from the Sheffield city region. Entrepreneursh. Regional Dev. 26 (3-4), 257–281. doi:10.1080/08985626.2014.894129

Xu, Y., and Deng, H. Y. (2020). Diversity, innovation and urban economic resilience. Econ. Dyn. 8, 88–104.

Xu, Y. Y., and Wang, C. (2017). Influencing factors of regional economic elasticity under the background of financial crisis—taking zhejiang province and jiangsu province as examples. Adv. Geogr. Sci. 36 (8), 986–994. doi:10.18306/dlkxjz.2017.08.007

Xu, Y., and Zhang, L. L. (2019). The economic resilience and origins of Chinese cities: An industrial diversification perspective. Finance Trade Econ. 40 (7), 110–126. doi:10.19795/j.cnki.cn11-1166/f.2019.07.008

Yicheol, H., and Stephan, J, G. (2015). The economic resilience of U.S. counties during the great recession. Rev. Reg. Stud. 45, 131–149. doi:10.52324/001c.8059

Zhang, M. D., Wu, Q. B., and Li, W. L. (2021). Industrial structure change, total factor productivity and urban economic resilience. J. Zhengzhou Univ. Philosophy Soc. Sci. Ed. 54 (6), 51–57.

Zhao, C. Y., and Wang, S. P. (2021). The impact of economic agglomeration on urban economic resilience. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 1, 102–114. doi:10.19639/j.cnki.issn1003-5230.2021.0008

Zheng, C. D., and Qi, Y. Y. (2022). Theoretical and empirical research on the impact of China's financial development on macroeconomic resilience. J. Southwest Univ. Natl. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed. 43 (1), 117–131.

Appendix

Keywords: industry diversification, regional economic resilience, financial development, technological innovation, human resources

Citation: He D, Miao P and Qureshi NA (2022) Can industrial diversification help strengthen regional economic resilience?. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:987396. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.987396

Received: 06 July 2022; Accepted: 31 October 2022;

Published: 21 November 2022.

Edited by:

Alex Oriel Godoy, Universidad del Desarrollo, ChileReviewed by:

Luigi Aldieri, University of Salerno, ItalyBilal Hussain, Government College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan

Copyright © 2022 He, Miao and Qureshi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Naveed Akhtar Qureshi, bmF2ZWVkQGliYS1zdWsuZWR1LnBr; Pengjia Miao, bXBqNzE4QDEyNi5jb20=

Dan He

Dan He Pengjia Miao

Pengjia Miao Naveed Akhtar Qureshi

Naveed Akhtar Qureshi