94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 06 September 2022

Sec. Environmental Economics and Management

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.983860

The pandemic has presented governments with a variety of complex effects. These include the disruption of the entire economy, the development of mass unemployment, and the impact of the pandemic on the public health systems. It is also becoming clear that the timescale of the crisis may significantly change the foundations of society’s daily lives. This study is focused on analyzing the effects of Covid19 on the employment and businesses sectors. It also examined the various policies and actions that governments of selected countries took and can take to sustain the economic recovery. Although the pandemic has already caused unprecedented social and economic crises, it is still not over. The pandemic caused unprecedented health, economic environment, and social crises at the global level, however, several measures to curb the damages are underway, as the development of vaccines, immunization campaigns, job retention schemes, and financial support schemes to offset the worst economic impact of COVID-19. Under the current pandemic situation where new variants are still on the loose and causing trouble in many parts of the world, it is extremely important to maintain highly targeted support, especially towards the sustainable job market. Otherwise, bankruptcies and unemployment can make the economic recovery much harder. Strong economic policies can create and sustain jobs by supporting employers to avoid bankruptcies particularly for emerging and high-performing companies. To avoid experiencing the same issues that young people experienced during the global financial crisis, states should take immediate action to help them avoid falling behind. Concrete measures are required to sustain their connection with the education system and labor market.

The exact economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic is still unknown. Although the full economic effect of the disease and health disaster is still unknown (Jaffar et al., 2019; Al Halbusi et al., 2022; Farzadfar et al., 2022; Geng et al., 2022; NeJhaddadgar et al., 2022). It is important to learn from pandemic’s early stages to avoid repeating the damages for mental health and economic losses (Azhar et al., 2018; Jaffar 2020; Aqeel et al., 2021a; Moradi et al., 2021; Ge et al., 2022). Circumstantial evidence from a range of media sources as well as from macro-economic data on corporate business decline, mental health challenges, less new employment opportunities and GDP decline is abundant (Aqeel et al., 2021b; Li et al., 2021; Aqeel et al., 2022; Mubeen et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2022). Few studies explored the effects of the pandemic on business activities, firm performance and labor markets (Asad et al., 2017; Aman et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Rahmat et al., 2022; Yao et al., 2022). The provision of vaccines, emotions control and equal health facilities is still a challenge (Su et al., 2021a; Su et al. 2021b; Su et al. 2021c; Lebni et al., 2021; Mubeen et al., 2021; Shoib et al., 2021; Soroush et al., 2021). This study examines health problems and uses the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s calculations to analyze the effects of the outbreak on various sectors of the economy (Lebni et al., 2020; Azadi et al., 2021; Azizi et al., 2021; Local Burden of Disease 2021; Moradi et al., 2021). Due to the pandemic, some companies experienced a loss of sales and considered laying off workers (Kalemli-Özcan et al., 2018; Humphries et al., 2020; Paulson et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Awan et al., 2022). This caused them to lose their liquidity. The data relating to enterprise permits to recognize this procedure better. It also provides an insight into the impact of temporary closures of businesses on the economy and shows how various factors such as wage cuts and hours of work affect workers. This effect led to a significant economic cost.

The pandemic has developed challenges for economic activities in circular economy, social sustainability and sustainable development (Awan & Sroufe, 2019; Golroudbary et al., 2019; Awan et al., 2020; Alhawari et al., 2021; Dhir et al., 2021). Government organizations and business firms have faced difficulties to maintain sustainable operations administration for logistics due to the pandemic circumstance. Organizations implemented CSR activities (Hussain et al., 2017; Golinska-Dawson & Spychała, 2018; Awan, Khattak, & Kraslawski, 2019; Golroudbary et al., 2019; Ikram et al., 2021). The pandemic challenge motivated leadership to implement green innovation and shift to green energy development. Organizations implanted technological applications, designed value chains, and sustainability in the circular economy (Awan & Sroufe, 2022; Begum, Ashfaq, Xia, & Awan, 2021; Kumar et al., 2022; Rashid Khan et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2019).

Government policies, such as Temporary workplace closures, designed to save lives have often had a significant impact on sales and labor. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused severe and wide-reaching effects. It has also affected various aspects of the labor market and businesses. This study aims to identify the various ways in which the pandemic has affected the labor market and businesses.

As mentioned earlier, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented in its complexity and severity. It led to the biggest collapse in demand for goods and services since the Great Depression. It affected various industries and regions around the world, causing them to impose nationwide lockdowns. The uncertainty surrounding the recovery and the severity of the crisis raised concerns that many businesses would fail—especially the smaller ones. During the crisis, governments rushed to respond to the fallout. The complexity of the situation presented policymakers with a limited set of real-time data to decide which firms and sectors were most vulnerable to covid-19 shock.

One year after the pandemic, the world is finally getting used to the idea of how the disease will eventually be eradicated. With the development of multiple vaccines, there is a growing hope that the pandemic will eventually be over. Owing to unprecedented actions taken by the government and central banks have led past the worst of the crisis. The unemployment rate has partially been reversed as global activity in various sectors has recovered. After the pandemic, the global economy is expected to grow by 4.2% (OECD, 2020a). However, the recovery will be contingent on various factors, such as the evolution of the virus and the effectiveness of government support. Despite the significant progress made in the production and distribution of vaccines, there are still significant obstacles in the way of effectively immunizing large portions of the population (Anderson et al., 2020). They noted that it will take a large portion of the population to be sufficiently immune to prevent disease outbreaks. The new strains causing the pandemic are more infectious and could diminish vaccines’ effectiveness. If a weak confidence scenario is considered, the global economy is expected to grow at a lower level in 2021 (OECD, 2020b). The OECD’s projections show that the decline in North America and Europe’s contribution to global growth will reverse once vaccine distribution is done swiftly and efficiently. Even as the global economy begins to recover from the crisis, it is expected to remain below its pre-crisis level by the end of 2022 even as many countries benefit from the recovery (OECD, 2020c). Lessons from the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic are needed to be applied to prevent a repeat of the situation from happening again.

This transition period warrants careful handling as many households and companies are still struggling due to the recession. The rise in the number of job retention schemes is also expected to continue. While it is true that many firms that have recovered are now hiring again, identifying which ones are still struggling and which ones are worth supporting is more important than ever. Too soon to pull support can lead to higher unemployment, poverty, and bankruptcies. This is especially true for households with young children. Without adequate support of government, households may have to cut back on their basic consumption. This can happen even for very low-income families (OECD, 2014). Young people are especially vulnerable to the effects of the current financial crisis, just as if they were during the global financial crisis. People who were exposed to COVID-19 risk paying the price for their entire life. Having a worse job and a lower income are two of the factors that people are more likely to face when it comes to experiencing social issues. They also tend to face other problems such as criminal activities (Wachter, 2020).

The key to supporting the most vulnerable individuals during the transition phase is how policymakers can help them find jobs while promoting the creation of new industries. There are also concerns that the support for the most vulnerable individuals could have detrimental effects on the labor market in the long term. Based on the global financial crisis, It has been evidenced that the efficiency cost of providing support to unemployed people is not very large as long as there are long lines of people wanting to apply (Landais et al., 2018; OECD, 2020d).

As the situation worsens, governments should implement policies that are geared toward addressing the most vulnerable individuals and firms. Doing so would allow them to avoid increasing the budget deficit. Most countries will also need to do more with less as the tight budget constraints make it difficult to fund programs. This includes focusing on the most vulnerable groups, such as women, the poor, and informal workers. Even though they have done their part, low-income countries will still face challenges as they continue to face various issues, such as the implementation of debt restructuring and concessional financing. The international community will also need to help them speed up the operationalization of their debt treatment frameworks.

The study consists of seven broad interrelated issues. The first two sections deal with the literature review and the response to the COVID-19 effects. The second section of this paper focuses on the dynamics of the coronavirus. The third section tackles the various aspects of the job retention schemes (JRS) and the labor market. The fourth section focuses on the effectiveness of government interventions aimed at rescuing and stimulating the economy. The fifth section is about analyzing the various ways to stimulate job creation. The sixth section is dedicated to comparing Job market before and after the pandemic. The next section explores the implications of the economic crisis on the future of jobs. It also talks about the changes that COVID-19 may bring about in the labor market.

The COVID-19 crisis-hit European countries in the first quarter of 2020. The number of infections has continuously increased, and various restrictions have been implemented to prevent the spread of the virus since January. These measures were eased up in most countries in May. They were implemented in phases after several weeks. The impact of the pandemic on the global economy is being studied in greater detail than ever before. The studies show that the most vulnerable segments of the workforce are being hardest hit by the crisis.

The Covid-19 pandemic outbreak caused significant disruption in almost all industry sectors. (Dai et al., 2020). The adverse impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on small businesses was widely acknowledged (WTO, 2020). Under Covid-19 stress, limited access to commercial financing, and financial fragility led to severe effects on small businesses (Barthik et al., 2020). Several studies have shown that the negative effects on the business environment are severe. These include the reduction in revenue, the layoffs of workers, and the liquidity crisis (see for instance Cirera et al., 2021).

Studies on the impact of the pandemic on employment and production show that it hurt firms and individuals. In the first wave of the crisis, sales at firms declined by over 70 percent, and employment was negatively affected by the crisis particularly for SMEs (Apedo-Amah et al., 2020). Other studies noted that the employment of women, young people, and the less educated workforce was most affected by the crises (Borland and Charlton, 2020; Costa Dias et al., 2020). In Honduras, the implementation of stricter containment measures has significantly affected formal firms in terms of revenue losses, however, larger firms experienced smaller revenue losses (Bachas et al. (2021).

In response to the COVID-19 shock, governments have introduced various measures to support businesses. Some of these included tax deferrals, interest-free loans, and direct cash transfers. Additional measures consist of equity injections and government-guaranteed bank loans. These were aimed at helping smaller businesses avoid bankruptcy. Various studies have been conducted on how government policies can help businesses address the effects of Covid-19 (see, for instance, Chetty et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020). In a note released in 2021, the International Monetary Fund noted that combining the support provided by job retention and relocation services could help minimize the negative effects of the pandemic (Jaffar et al., 2021).

Studies on the impact of the pandemic on firms also explore the effects of government financial support on the firms’ liquidity (see for example Banerjee et al., 2020; Yoosefi Lebni et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). The most important work that was done in this study was by Cirera et al. (2021), who analyzed how government policies affected the operations of small businesses. They found that women-owned enterprises were more likely to be denied financial support. This study also revealed that firms in developing nations are more likely to be misidentified as recipients of support schemes. This finding suggests that the lack of effective governance and enforcement in these countries may have led to the mistargeting.

Several studies conducted in different countries revealed mixed results regarding the effectiveness of the government support programs in the US, China, and Italy (see Cororaton and Rosen, 2020; De Marco, 2020; Granja et al., 2020). In China, the government has been implementing various policies aimed at supporting the country’s firms that are affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. These policies have been instrumental in helping firms minimize the effects of the epidemic. They include the reduction of Social Insurance contributions and payroll tax (Chen et al., 2020). However, others noticed that the US government’s financial support policies did not work as well as they should have (Chetty et al., 2020).

Despite the debate about the use of policy instruments to address supply-side shocks, it is still not yet clear which approach is more effective: fiscal stimulus or monetary policy. A study conducted by Guerrieri et al. (2020) argues that monetary policy is more effective at addressing short-term liquidity issues than fiscal stimulus. However, another study conducted by Chetty et al. (2020) found that the use of conventional tools to stimulate demand and provide liquidity may have limited the capacity of firms to restore jobs following the pandemic.

The recent mutations of the coronavirus have raised concerns about the public’s confidence in the recovery efforts. However, as countries continue to work on their long-term recovery plans, this crisis should not be forgotten.

Governments should be aware of the costs associated with implementing policies, as well as the varying effects of their actions on people. Lockdowns have been known to set back social and economic progress, but they should also be made to work through these setbacks to ensure that the vulnerable are not left behind. Having the necessary policies and procedures in place is also important to ensure that the people affected by a lockdown are not left behind. This can be done through the implementation of effective and efficient movement restrictions. Besides isolation and treatment, other precautionary measures such as mass testing and physical distancing have also been able to help prevent the spread of the disease.

In addition to regular vaccinations, effective public health measures such as clean working environments and safety measures are also needed to limit the spread of the virus. Although the availability of the vaccine will affect the business community’s economic performance, it is still important to note that the virus’ volatility can still occur. The importance of the vaccination campaign can be seen in the economic recovery and therefore on employment, and in reducing the uncertainty that affects firms and households. In addition, its positive effects on the social benefits far outweigh the expenses (Brito, et al., 1991; Boulier, et al., 2007). In addition, the externalities of vaccination are also beneficial for the economy.

After almost one and a half years of the crisis, uncertainty about the future remains high. Many countries kept on enhancing strict containment measures. Therefore, there is also a growing risk of people becoming “pandemic fatigued”. This is causing a sense of complacency to emerge. Many SME companies in the most affected sectors are struggling to secure the support they need to endure the uncertainty and low activity. Without this support, many of them are on the verge of bankruptcy. Despite the slow recovery from the economic crisis, various measures are still needed to support the workers and sectors that are still affected by the situation. These include encouraging business creation and hiring. Moreover, strong measures are needed to support the labor market to prevent further job losses and encouraging the creation of businesses, and avoid high-risk businesses. These actions are aimed at preventing a crisis from developing into a long-term one.

Due to the recent health crisis, many workers have been affected by the restrictions imposed on their activities. They are now looking for ways to restart their activities. Job retention schemes (JRS) have been influential in alleviating the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the labor market (OECD, 2020a). As Figure 1 shows, in the second quarter of 2020, around 1/3rd of workers in several OECD countries were on a job retention schemes. As businesses reopened after the conciliatory phase, the share of employees on JRS decreased significantly. Nevertheless, In November and December of 2020, the number of people applying for JRS increased as countries faced the second wave of the pandemic. In 2020, the take-up of JRS was still substantially larger than that of the global financial crisis in 2009 (Hijzen and Martin, 2013).

Job retention schemes were launched by various nations in the course of the peak of COVID-19 supporting approximately 60 million jobs, ten times more than the support offered during the global financial crisis. As shown in Figure 1, a quick decline in JRS is observed from April 2020 (peak) to September 2020 as the pandemic subsided, later as the COVID-19 cases increased again through the winter in many parts of the world and a rise in the JRS is observed again in February/March 2021.

While the COVID-19 crisis, JRS responded to the effects of the pandemic on labor markets. As governments fight against the pandemic, they remain a vital tool for supporting businesses and workers. Although current uneven economic activities are challenging, the jobs with likely return to viability need to be focused on (OECD, 2020b). There are always uncertainties when it comes to the viability of certain jobs, particularly in the sectors that are still subject to mandatory restrictions. Furthermore, the reallocation process is expected to remain restrained until job creation sees a sustained increase. Nevertheless, countries can also enhance their support for jobs in the sectors that are at stake as they face specific restrictions. In other words, they can differentiate support for workers in sectors that are still subject to certain restrictions.

It is generally necessary for workers to be able to move to unsubsidized areas in order to avoid being subjected to the subsidy. This can be done through the establishment of job retention schemes and the registration of individuals with the public employment service. For example, in the Netherlands, it is required that employers applying for Job Retention Support (JRS) must affirm their support for training. Various other measures have been undertaken by the government to enhance access to online learning. The French government announced a substantial increase in financial benefits, from 84% of their net pay to 100% under JRS, for those workers who undertake training. According to the French Ministry of Labor’s survey data (DARES, 2020), in Q3 2020, around 20% of the employees of JRS beneficiary firms are commencing several types of training. The share was slightly greater in medium and large firms compared to small-sized firms.

Creating a training calendar can be challenging since it must be coordinated with different work arrangements and time constraints. Equally, having the necessary training can be challenging, especially for workers who have irregular work schedules. However, it is still essential that workers on JRS obtain the necessary training to prepare for their recovery. Conditions or motivations to register with the PES and upskilling/reskilling would help JRS to safeguard employees without delaying the reorganization of employment to growing business and sectors.

Many people who became unemployed during the first phase of the pandemic may exhaust their unemployment benefits at some point during the second phase. This is expected to increase the number of people claiming last-resort minimum-income benefits. Several countries have temporarily raised the number of benefits or offered one-off payment programs. As countries consider reinstating certain concessions, they should make them more accessible and less restrictive to encourage more people to take advantage of them. Effective targeting is crucial; however, states should make certain that those in urgent need continue to get assistance. For instance, income tests could be reintroduced to let households adjust their spending while maintaining asset tests relaxed as-long-as employment prospects are still limited. Some countries may want to expand programs that encourage job hunting and training for young adults. They may also want to make it easier for them to receive benefits.

Massive support measures were taken by governments to put a stop to the rise of business failures during the COVID-19 crisis across the globe. According to data from OECD (2021a), the decline in firms’ closures slowed down in 2020 even as the economy contracted (Wang et al., 2020). The bankruptcy rate among SMEs would have doubled in absence of government support (Gourinchas et al., 2020). The economic downturn has affected various sectors such as education, the arts, and recreation. These sectors are expected to be adversely affected by the effects of the crisis. This crisis has also led to a significant decline in business creation. There is a high risk of a large number of bankruptcy filings without a reallocation of resources to infant and growing firms.

Creative destruction is essential to enable resources allocation to more productive activities, for sustaining economic growth and improving employment prospects. It is a very useful tool to help (re)allocate resources more effectively to support economic growth. Nevertheless, this process may take a while to implement as businesses start to generate more debt and require more time to establish their operations. This policy is very useful, but it has certain risks. Therefore, governments need to keep a very close eye on the economic activities of the firms for the next few months to manage these risks. The first risk is a reduction in innovation and investment efforts by high-performing companies that are over-indebted. This phenomenon, known as debt overhang, can lead to an underinvestment problem (Demmou et al., 2021). Moreover, high-performing over-debited companies consider bankruptcy to pay off their debts due to the above-mentioned phenomena. Another risk is of saving the zombie firms (companies that were already unfeasible before COVID-19 started but the public support they received helped them survive). Aggregate productivity would be adversely affected in both instances, which was already a concern before COVID-19 began (Adalet McGowan et al., 2017).

Comparatively, the first type of risk will likely be more severe in the short term, especially for employment. To avoid a massive default by companies, particularly SMEs, it is necessary to tackle the high levels of corporate debt that were present before the crisis. In addition, substantial restructuring of debt is also needed during this pandemic crisis.

While public support for startups is targets existing firms, the creative destruction process triggers followed by business creation resumption. The effect of a “lost generation of firms” can be quite significant. According to Sedlacek (2020), if the firm entry persisted constant throughout the financial crisis, the unemployment rate in the US would have been half a percentage point lower 10 years later, and output would have recovered 4–6 years earlier.

Additionally, a large body of empirical evidence indicated that new businesses create a substantial share of new jobs (Haltiwanger, et al., 2013; Criscuolo, et al., 2014). Therefore, it is important to support start-ups to intact an entire generation of new firms and hence new jobs. It is also important to protect self-employed workers from getting unemployed. This can be done by offering them unemployment insurance or relaxing eligibility conditions for starting new companies in the following couple of years. It would also help promote the growth of new businesses and minimize the risks involved in starting a new venture. Social partners can also help SMEs develop and grow by providing them with the necessary support and advice.

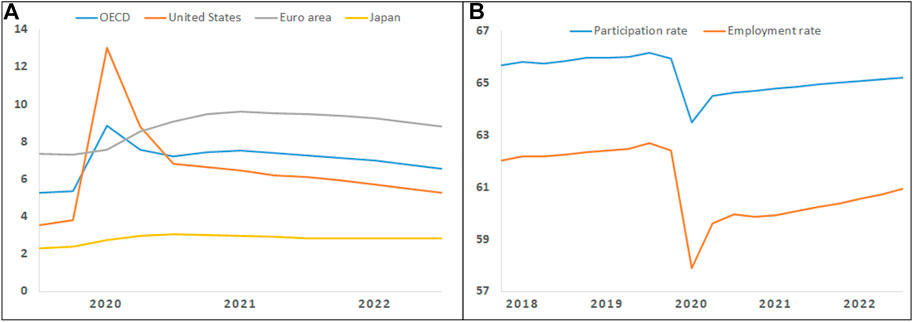

During the first wave of a pandemic the unemployment rates surged in most parts of the world as shown in Figure 2A and the labor market participation rate has further declined than it was experienced in the global financial crisis (OECD, 2020c). Moreover, job losses are highly concentrated at lower wage levels (OECD, 2020b). This phenomenon is understandable due to the restrictions imposed by the governments and the fear among the public. To overcome the havoc caused by the pandemic new jobs must be created and provided quickly and this can be achieved through a long-term strategic commitment of the governments in the worst-hit countries.

FIGURE 2. (A) Unemployment rate - % age of labor force (B) Employment and participation rates % of population aged 15–74 1.

There is no way out of the current crisis unless the recovery in job creation materializes. Since the recovery will not be quick enough to make up for the losses of the previous jobs (See Figure 3), the focus is on creating new ones. The recovery plans of many countries are key to sustaining the global economy. However, their full implementation typically spans months or even years.

In the short term, monetary and fiscal policies should remain complementary to maintain the economy’s growth (OECD, 2020d). Temporary and targeted hiring subsidies can help promote job creation at the micro-level. In a few countries, such as Italy, the United Kingdom Australia, and France, these schemes have been introduced or renewed. Empirical evidence about the financial crisis has indicated that hiring subsidies can stimulate job growth and cost-effectiveness (Cahuc, et al., 2018). Direct job creation could also be considered to support the logistical support for testing and vaccination. The concept of a “youth corps” is a potential solution to address the country’s healthcare challenges. It could involve helping individuals deliver vaccines and other administrative tasks to public health facilities.

The increasing economic activity and the spread of new infectious diseases such as COVID-19 and influenza are contributing to the development of new barriers to the control of these diseases. Due to the increasing number of people working and living in different economic sectors, the risk that individuals will contact sources of contagious diseases increases. The economic consequences of new infections can be severe, especially when they affect workers and the production of goods and services. For instance, the absence of workers due to these infections can cause the disruption of production at the workplace. Besides disrupting the production of goods and services, the supply chains of these companies can also be disrupted due to the emergence of new infections. For instance, the COVID-19 outbreak has caused a major economic depression in various countries.

Global merchandise trade indicators are showing a healthy sign as shown in Figure 3, increasing demand in different sectors can be seen (Figure 5). Although the service sector is still not shining, particularly air traffic remained 32% lower in April 2021 than the average of 2019 (OECD, 2021b). This economic turnaround has created new jobs in different countries and sectors in different proportions (Figures 4, 5).

Job openings remained significantly low during 2020, however, towards the end of the year job openings started picking up and a significant recovery is seen in the year 2021 (Figure 4). As the restrictions eased down and the level of confidence was restored among the public, demand for different products increased, and as a result job openings increased in different sectors. Health and production sector particularly posted more jobs as compared to other sectors (Figure 5).

Despite the low number of job openings during the pandemic, some improvements were seen in the summer of 2020 as various states implemented effective measures to address the issue. However, the decline in job openings in the second wave of the pandemic continued (see Figure 4). Notwithstanding this, there is still substantial heterogeneity across various occupations and sectors. In December 2020, high-frequency indicators of online job postings indicate a 45% decline in demand for labor in accommodation and food services in pre and post-pandemic levels, whereas online job postings in transportation and storing services were thirty percent higher than in January 2020. Similarities can be found in the types of jobs posted online during the pandemic. Looking at the level of job openings for different occupations, such as hospital workers, employees of food retailers, and warehouse personnel, data indicates that the demand for these positions either remained unchanged or exhibited an increase during the pre-crisis period.

Even though job opportunities are still limited and switching jobs is still challenging owing to geographical distribution and needed skills; there is opportunity to reorganize employees to sectors and professions where the demand is anticipated to recover faster. Thus, during a pandemic, governments should step up efforts to improve the skills of workers and boost job opportunities for them, besides their existing programs that support job search and training. Countries can also scale up their ALMP (Active Labor Market Program) to enhance the effectiveness of these efforts.

Furthermore, not only job seekers, but PES can also provide valuable support to employers. The outcomes of a large scale randomized experiment conducted in France regarding the free recruitment services offered by the PES to SMEs suggest that a transfer in the filtering and pre-screening responsibility of the hiring procedure away from the enterprise to the PES official can have a significant net impact on hiring and job posting (Algan, et al., 2020).

To meet the challenges, PES needs additional resources, which can be either through hiring or engaging private-service providers. Some countries, for instance, the United Kingdom, have started increasing their PES staff. Without new resources, the existing schemes and services will most likely be overwhelmed by the influx of demand. This could result in a marked decrease in the quality of services.

In addition to hiring new staff members, the PES also needs additional resources to address the increasing demand for its services. This can be done through the recruitment of new staff members or using private-sector providers. For instance, United Kingdom have increased their PES workforce. If the lack of these resources leads to a reduction in the quality of the services, then the situation will become worse.

After the global financial crisis, the resources needed to support job placement, training, and recruitment were not increased despite soaring joblessness. In 2007–2010, the number of jobless increased by 54% on average in the OECD area., while the ALMP spending only increased by 21%. Resultantly, during the time of the greatest need, the average amount spent per job seeker decreased by 21% (OECD, 2011). This suggests that addressing the COVID-19 labor market challenges will require significant additional investments in PES and ALMPs. Nevertheless, if the capacity constraints of PES are not resolved, then its increased resources may not be effective. PES might have to reduce its non-essential activities, for instance, it might have to scale down its job-search monitoring services or stop processing benefit claims (OECD, 2020a). Furthermore, with the rapid emergence of digital platforms and innovative solutions, countries with a modern and proactive PES can provide better support to jobseekers and employers.

Lastly, it is also important not to lose contact with young people who have recently lost their jobs or left their school without finding a new one. Due to various factors such as lack of awareness, poor communication skills, and distrust in public authorities, these vulnerable young people are not reaching out to the PES. In times of crisis, rapid and effective outreach through social media campaigns and collaboration with youth organizations and school administration can be particularly important.

In this study, the detailed impact of the coronavirus epidemic on the labor market is discussed. Despite the widely held belief that the crisis is over, its impact on the work environment will likely continue. Following the crisis, many people may start looking for jobs that are more meaningful to them. Others may start focusing on their job security and prioritize earnings.

The effects of recessions on the labor market are difficult to predict. However, they can be influenced by a variety of factors, such as changes in expectations about the economy. The study, conducted by Cotofan et al. (2020), also noted that young people who experienced the worst economic conditions during the early stages of the crisis were more likely to prioritize financial stability over job security. Early evidence suggests that the pandemic might have affected their career decisions. Even though it is yet too soon to say, the pandemic may have an impact on the expectations of young people in the future. It is already creating a changing landscape of work values.

One of the most significant changes that occurred during the course of the pandemic was the rise of people working from home. In October 2020, about one-fourth of the United Kingdom’s workforce was working from home, a decrease from almost half in the first lockdown, although far higher than the pre-pandemic level of barely 5% (Gibbs, 2020). While working from home has had its slight negative effects on productivity, it also provided some immediate benefits particularly avoiding the commute and increased autonomy (Lee & Tipoe, 2020).

Many companies are planning on getting rid of their offices. However, this move may end up costing them a huge sum of money and time. With the rise of the workplace revolution, many companies are now thinking of ditching their desks entirely (Lebowitz, 2020). However, this move is subject to the risk of overlooking potential negative effects on productivity. Moreover, homeworking could negatively affect companies’ intellectual capital and employees’ long-term job security. It is also a risky strategy that could undermine social and operational capital.

Within this frame of reference, social and intellectual capital are often depleted when people are working mostly at home. This is because the stocks are usually replenished by new ideas and places, and the inflow of new people. The intellectual and social capital that people develop is stimulated by their interactions with others. This is because people tend to work together more frequently. While there’s a lot of evidence suggesting that home workers are more productive than they initially thought, however, they are also more likely to be neglected for promotion Bloom et al. (2015). This is a sign that the need to build social capital with coworkers. Having a good working relationship with your co-workers and management is very important to both life satisfaction and your job. Working full-time from home does not provide such an opportunity to build working relationships Krekel et al. (2019). Work is more than a paycheck. It is a segment of people’s personality. According to Bloom et al. (2015), when people lose their job, half of their negative impact is due to the loss of identity and social ties, which often come with a job. Many workers who were laid off due to the pandemic still experienced significant well-being losses compared to those who did not lose jobs.

Although the pandemic may eventually be over, workers still need support and social connection at work. Moving-forward, it is crucial to maintain the advantages of working from home while also enabling workers to develop and maintain their social and intellectual capital. During the pandemic, flexibility turns out to be an even more significant factor in supporting well-being at work. Even working at the office couple of days weekly may offer workers to network, provide identity and routine to support their well-being. A home working model that still tenders employees the networking and collaboration in-person opportunities could provide the needed in-flow of social, intellectual capital and lead to substantial productivity dividends (Davis et al., 2021).

A significant disruption in demand and supply is evident during the pandemic that led to several problems for the businesses, economies, and societies, for example, decline in sales, liquidity shortage, temporary and permanent business closures, wage cuts, and increased unemployment. Under the current state of a pandemic where uncertainty is still prevailing, the pace of economic recovery is very slow. A revival of job markets is observed in many countries, but still, a huge number of workers are unemployed. If the uncertain situation continues, many of the struggling firms may be forced to file bankruptcies which will further deteriorate the already miserable job market. So, it is extremely important to provide support to households and businesses through macro and microeconomic policies to avoid the worst social and economic crisis characterized by unemployment and insolvencies.

During the pandemic, a few innovative measures have been adopted by the firms to mitigate the damages caused by the pandemic, for example, remote working, online sales, services, etc. The majority of the businesses experienced negative effects of the restrictions imposed by the governments to control the effects of the pandemic, whereas only a small number of firms have received government support. Without such support, continued sales losses threaten the viability of firms and require further employment cuts. While preparing for the implementation of their massive stimulus programs, countries should sustain their support for those affected by the COVID-19 economic crisis. This includes providing the necessary incentives for job creation and sustaining the recovery of the private sector.

The lack of checks and balances on economic policies would threaten the recovery from the effects of Covid-19. This study raises concerns for further research. The permanent closure of firms will cause a significant job loss. It is most likely that firms that permanently close are very likely to cause significant job losses. This paper aims to provide an in-depth analysis of the failures that occurred during the crisis, and what they could have been done differently to prevent them.

Maintaining a balanced approach will require policymakers to provide adequate short-term support to ensure a resilient recovery and keep debt at a sustainable level. They will also need to develop credible multiyear plans to improve the public finances. This can be done through the establishment of effective revenue and spending frameworks.

The short-term costs of implementing programs designed to support the most vulnerable sectors are high, but they are significantly lower compared to the benefits of avoiding mass layoffs and bankruptcies. Additionally, these short-term costs can be lessened by boosting the direct assistance to the most exposed sectors, households, and companies, whilst encouraging start-ups and employment creation. Though several of the mechanisms and facilities needed to support the increasing number of recipients are already there, the additional financial and human resources at their disposal may need increase to deal with the influx of beneficiaries. Real-time and granular survey data are vital resources to guide policymakers in exceptionally challenging times. At the beginning of the pandemic, the efforts made by various countries to make these data widely accessible should continue.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: OECD.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adalet McGowan, M., Andrews, D., and Millot, V. (2017). “Insolvency regimes, technology diffusion, and productivity growth: Evidence from firms in OECD countries,” in OECD economics department working papers (Paris: OECD Publishing). No. 1425. doi:10.1787/36600267-en

Al Halbusi, H., Al-Sulaiti, K., and Al-Sulaiti, I. (2022). Assessing factors influencing technology adoption for online purchasing amid COVID-19 in Qatar: Moderating role of word of mouth. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 942527. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.942527

Algan, Y., Crépon, B., and Glover, D. (2020), “Are active labor market policies directed at firms effective? Evidence from a randomized evaluation with local employment agencies”, J-PAL.

Alhawari, O., Awan, U., Bhutta, M. K. S., and Ülkü, M. A. (2021). Insights from circular economy literature: A review of extant definitions and unravelling paths to future research. Sustainability 13 (2), 859. doi:10.3390/su13020859

Aman, J., Shi, G., Ain, N. U., and Gu, L. (2022). Community wellbeing under China-Pakistan economic corridor: Role of social, economic, cultural, and educational factors in improving residents’ quality of life. Front. Psychol. 12, 816592. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.816592

Anderson, R., Vegvari, C., Truscott, J., and Collyer, B. S. (2020). Challenges in creating herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection by mass vaccination. Lancet 396/10263, 1614–1616. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32318-7

Apedo-Amah, M. C., Avdiu, B., Xavier Cirera, M. C., Davies, E., Grover, A., Iacovone, L., et al. (2020). “Businesses through the COVID-19 shock: Firm-level evidence from around the world,” in Policy research working paper 9434 (Washington, D.C., United States: World Bank).

Aqeel, M., Raza, S., and Aman, J. (2021a). Portraying the multifaceted interplay between sexual harassment, job stress, social support and employees turnover intension amid COVID-19: A multilevel moderating model. Found. Univ. J. Bus. Econ. 6 (2), 1–17. doi:10.fui.edu.pk/fjs/index.php/fujbe/article/view/551

Aqeel, M., Rehna, T., Shuja, K. H., and Abbas, J. (2022). Comparison of students' mental wellbeing, anxiety, depression, and quality of life during COVID-19's full and partial (smart) lockdowns: A follow-up study at a 5-month interval. Front. Psychiatry 13, 835585. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.835585

Aqeel, M., Shuja, K. H., Rehna, T., Ziapour, A., Yousaf, I., Karamat, T., et al. (2021b). The influence of illness perception, anxiety and depression disorders on students mental health during COVID-19 outbreak in Pakistan: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 15 (1), 17–30. doi:10.1108/ijhrh-10-2020-0095

Asad, A., Irfan, M., and Raza, H. M. (2017). The impact of HPWS in organizational performance: A mediating role of servant leadership. J. Manag. Sci. 11, 25–48.

Awan, U., Khattak, A., and Kraslawski, A. (2019). “Corporate social responsibility (CSR) priorities in the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) of the industrial sector of sialkot, Pakistan,” in Corporate social responsibility in the manufacturing and services sectors. Editors P. Golinska-Dawson, and M. Spychała (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg), 267–278.

Awan, U., Kraslawski, A., Huiskonen, J., and Suleman, N. (2020). “Exploring the locus of social sustainability implementation: A south asian perspective on planning for sustainable development,” in Universities and sustainable communities: Meeting the goals of the agenda 2030. Editors W. Leal Filho, U. Tortato, and F. Frankenberger (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 89–105.

Awan, U., Sroufe, R., and Bozan, K. (2022). Designing value chains for industry 4.0 and a circular economy: A review of the literature. Sustainability 14 (12), 7084. doi:10.3390/su14127084

Awan, U., and Sroufe, R. (2019). Interorganisational collaboration for innovation improvement in manufacturing firms’s: The mediating role of social performance. Int. J. Innov. Mgt. 24 (05), 2050049. doi:10.1142/s1363919620500498

Awan, U., and Sroufe, R. (2022). Sustainability in the circular economy: Insights and dynamics of designing circular business models. Appl. Sci. 12 (3), 1521. doi:10.3390/app12031521

Azadi, N. A., Ziapour, A., Lebni, J. Y., Irandoost, S. F., and Chaboksavar, F. (2021). The effect of education based on health belief model on promoting preventive behaviors of hypertensive disease in staff of the Iran University of Medical Sciences. Arch. Public Health 79 (1), 69. doi:10.1186/s13690-021-00594-4

Azhar, A., Wenhong, Z., Akhtar, T., and Aqeel, M. (2018). Linking infidelity stress, anxiety and depression: Evidence from Pakistan married couples and divorced individuals. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 11 (3), 214–228. doi:10.1108/ijhrh-11-2017-0069

Azizi, M. R., Atlasi, R., Ziapour, A., and Naemi, R. (2021). Innovative human resource management strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic narrative review approach. Heliyon 7 (6), e07233. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07233

Bachas, P., Brockmeyer, A., and Semelet, C. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on formal firms in Honduras: Evidence from monthly tax returns, MTI practice notes 9L. Washington, D.C., United States: World Bank.

Banerjee, R., Illes, A., Kharroubi, E., and Serena, J-M. (2020). “COVID-19 and corporate sector liquidity,” in BIS bulletin 10 (Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements).

Begum, S., Ashfaq, M., Xia, E., and Awan, U. (2021). Does green transformational leadership lead to green innovation? The role of green thinking and creative process engagement. Bus. Strategy Environ. 31 (1), 580–597. doi:10.1002/bse.2911

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., and Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from homework? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q. J. Econ. 130 (1), 165–218. doi:10.1093/qje/qju032

Borland, J., and Charlton, A. (2020). The Australian labour market and the early impact of COVID-19: An assessment. Aust. Econ. Rev. 53, 297–324. doi:10.1111/1467-8462.12386

Boulier, B., Datta, T., and Goldfarb, R. (2007). Vaccination externalities. . J. Econ. Analysis Policy 7–1. doi:10.2202/1935-1682.1487

Brito, D., Sheshinski, E., and Intriligator, M. (1991). Externalities and compulsary vaccinations. J. Public Econ. 45/1, 69–90. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(91)90048-7

Cahuc, P., Carcillo, S., and Le Barbanchon, T. (2018). The effectiveness of hiring credits. Rev. Econ. Stud. 86/2, 593–626. doi:10.1093/restud/rdy011

Chen, J., Cheng, Z., Gong, K., and Li, J. (2020). Riding out the COVID-19 storm: How government policies affect SMEs in China. Minneapolis, MN, United States: SSRN. Technical report.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Hendren, N., and Stepner, M. (2020). How did COVID-19 and stabilization policies affect spending and employment? A new real-time economic tracker based on private sector data. Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States: National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper 27431.

Cirera, X., Marcio, C., Davies, E., Grover, A., Iacovone, L., Lopez Cordova, J. E., et al. (2021). Policies to support businesses through the COVID-19 shock: A firm-level perspective. Washington, D.C., United States: World Bank. Policy Research Working Paper 9506.

Cororaton, A., and Rosen, S. (2020). Public firm borrowers of the US paycheck protection program. Covid Econ. Vetted Real-Time Pap. 10, 641–693. doi:10.1093/rcfs/cfab019

Costa Dias, M., Joyce, R., Postel-Vinay, F., and Xu, X. (2020). The challenges for labour market policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fisc. Stud. 41, 371–382. doi:10.1111/1475-5890.12233

Cotofan, M., Cassar, L., Dur, R., and Meier, S. (2020). Macroeconomic conditions when young shape job preferences for life, IZA discussion papers, No. 13123. Bonn: Institute of Labor Economics IZA.

Criscuolo, C., Gal, P., and Menon, C. (2014). “The dynamics of employment growth: New evidence from 18 countries,” in OECD science, technology and industry policy papers (Paris: OECD Publishing). No. 14. doi:10.1787/5jz417hj6hg6-en

Dai, H. Feng, Hu, J., Jin, Q., Li, H., Ranran, W., Wang, R., et al. (2020). Working paper. September: Center for Global Development.The impact of covid-19 on small and medium-sized enterprises: Evidence from two-wave phone surveys in China

DARES (2020). Activité et conditions d’emploi de la main-d’oeuvre pendant la crise sanitaire Covid-19. Paris: DARES.

Davis, M. A., Ghent, A. C., and Gregory, J. (2021). The work-at-home technology boon and its consequences. Available at SSRN 3768847.

De Marco, F. (2020). Public guarantees for small businesses in Italy during COVID-19. London, United Kingdom: The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). Technical report.

Demmou, L., Calligaris, S., Franco, G., Dlugosch, D., McGowan, M. A., Sakha, S., et al. (2021). Insolvency and debt overhang following the COVID-19 outbreak: Assessment of risks and policy responses”. Paris: OECD Publishing. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1651. doi:10.1787/747a8226-en

Dhir, A., Malodia, S., Awan, U., Sakashita, M., and Kaur, P. (2021). Extended valence theory perspective on consumers' e-waste recycling intentions in Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 312, 127443. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127443

Farzadfar, F., Naghavi, M., Sepanlou, S. G., Saeedi Moghaddam, S., Dangel, W. J., Davis Weaver, N., et al. (2022). Health system performance in Iran: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 399 (10335), 1625–1645. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02751-3

Ge, T., Ullah, R., Abbas, A., Sadiq, I., and Zhang, R. (2022). Women's entrepreneurial contribution to family income: Innovative technologies promote females' entrepreneurship amid COVID-19 crisis. Front. Psychol. 13, 828040. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.828040

Geng, J., Ul Haq, S., Ye, H., Shahbaz, P., Abbas, A., Cai, Y., et al. (2022). Survival in pandemic times: Managing energy efficiency, food diversity, and sustainable practices of nutrient intake amid COVID-19 crisis. Front. Environ. Sci. 13, 945774. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.945774

Gibbs, C. (2020). Coronavirus and the latest indicators for the UK economy and society. UK: Office of National Statistics ONS.

Golinska-Dawson, P., and Spychała, M. (2018). Corporate social responsibility in the manufacturing and services sectors. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

Golroudbary, S. R., Zahraee, S. M., Awan, U., and Kraslawski, A. (2019). Sustainable operations management in logistics using simulations and modelling: A framework for decision making in delivery management. Procedia Manuf. 30, 627–634. doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2019.02.088

Gourinchas, P., et al. (2020). COVID-19 and SME failures. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w27877

Granja, J., Makridis, C., Yannelis, C., and Zwick, E. (2020). Did the pay-check protection program hit the target? Massachusetts, United States: NBER. Technical report.

Guerrieri, V., Lorenzoni, G., Straub, L., and Werning, I. (2020). Implications of COVID-19: Can negative supply shocks cause demand shortages. Massachusetts, United States: NBER. Technical report.

Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R., and Miranda, J. (2013). Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young. Rev. Econ. Statistics 95/2, 347–361. doi:10.1162/rest_a_00288

Hijzen, A., and Martin, S. (2013). The role of short-time work schemes during the global financial crisis and early recovery: A cross-country analysis. IZA J. Labor Policy 2/1, 5. doi:10.1186/2193-9004-2-5

Humphries, J. E., Neilson, C. A., and Ulyssea, G. (2020). Information frictions and access to the pay-check protection program. J. Public Econ. 190, 104244. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104244

Hussain, T., Abbas, J., Li, B., Aman, J., and Ali, S. (2017). Natural resource management for the world’s highest park: Community attitudes on sustainability for Central Karakoram National Park, Pakistan. Sustainability 9 (6), 972. doi:10.3390/su9060972

Ikram, M., Sroufe, R., Awan, U., and Abid, N. (2021). Enabling progress in developing economies: A novel hybrid decision-making model for green technology planning. Sustainability 14 (1), 258. doi:10.3390/su14010258

Jaffar, A., Aman, J., Nurunnabi, M., and Bano, S. (2019). The impact of social media on learning behavior for sustainable education: Evidence of students from selected universities in Pakistan. Sustainability 11 (6), 1683. doi:10.3390/su11061683

Jaffar, A. (2020). The role of interventions to manage and reduce covid-19 mortality rate of the COVID-19 patients worldwide. Found. Univ. J. Psychol. 4 (2), 33–36. doi:10.33897/fujp.v4i2.158

Jaffar, A., Wang, D., Su, Z., and Ziapour, A. (2021). The role of social media in the advent of COVID-19 pandemic: Crisis management, mental health challenges and implications. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 14, 1917–1932. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S284313

Kalemli-Özcan, Ṣ., Laeven, L., and Moreno, D. (2018). Debt overhang, rollover risk, and corporate investment: Evidence from the European crisis. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. doi:10.3386/w24555

Krekel, C., Ward, G., and De Neve, J. E. (2019). “What makes for a good job? Evidence using subjective well-being data,” in The economics of happiness (Cham: Springer), 241–268.

Kumar, S., Raut, R. D., Priyadarshinee, P., Mangla, S. K., Awan, U., and Narkhede, B. E. (2022). The impact of IoT on the performance of vaccine supply chain distribution in the COVID-19 context. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 5, 1–11. doi:10.1109/tem.2022.3157625

Landais, C., Michaillat, P., and Saez, E. (2018). A macroeconomic approach to optimal unemployment insurance: Theory. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 10/2, 152–181. doi:10.1257/pol.20150088

Lebni, J. Y., Toghroli, R., Kianipour, N., NeJhaddadgar, N., Salahshoor, M. R., ., , and Ziapour, A. (2021). Nurses' work-related quality of life and its influencing demographic factors at a public hospital in western Iran: A cross-sectional study. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 42 (1), 37–45. doi:10.1177/0272684X20972838

Lebni, J. Y., Toghroli, R., NeJhaddadgar, N., Salahshoor, M. R., Mansourian, M., Ziapour, A., et al. (2020). A study of internet addiction and its effects on mental health: A study based on Iranian university StudentsA study of internet addiction and its effects on mental health: A study based on Iranian university students. J. Educ. Health Promot. 9 (1), 205. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_148_20

Lebowitz, S. (2020). Business insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/CEOs-no-offices-fully-remote-virtual-work-coronavirus-pandemic recession-2020-10.

Lee, I., and Tipoe, E. (2020). Time use and productivity during the COVID-19 lockdown: Evidence from the UK. London, United Kingdom: IZA Working Paper.

Li, Y., Al-Sulaiti, K., Dongling, W., Abbas, J., and Al-Sulaiti, I. (2022). Tax avoidance culture and employees’ behavior affect sustainable business performance: The moderating role of corporate social responsibility (original research). Front. Environ. Sci. 10. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.964410

Li, Z., Wang, D., Hassan, S., and Mubeen, R. (2021). Tourists' health risk threats amid COVID-19 era: Role of technology innovation, transformation, and recovery implications for sustainable tourism. Front. Psychol. 12, 769175. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.769175

Liu, Q., Qu, X., Wang, D., and Mubeen, R. (2022). Product market competition and firm performance: Business survival through innovation and entrepreneurial orientation amid COVID-19 financial crisis. Front. Psychol. 12, 790923. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.790923

Local Burden of Disease, H. I. V. C. (2021). Mapping subnational HIV mortality in six Latin American countries with incomplete vital registration systems. BMC Med. 19 (1), 4. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01876-4

Moradi, F., Tourani, S., Ziapour, A., Hematti, M., Moghadam, E. J., ., , and Soroush, A. (2021). Emotional intelligence and quality of life in elderly diabetic patients. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 42 (1), 15–20. doi:10.1177/0272684X20965811

Mubeen, R., Han, D., Alvarez-Otero, S., and Sial, M. S. (2021). The relationship between CEO duality and business firms' performance: The moderating role of firm size and corporate social responsibility. Front. Psychol. 12, 669715. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669715

Mubeen, R., Han, D., Raza, S., and Bodian, W. (2022). Examining the relationship between product market competition and Chinese firms performance: The mediating impact of capital structure and moderating influence of firm size. Front. Psychol. 12, 709678. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.709678

NeJhaddadgar, N., Ziapour, A., Zakkipour, G., Abolfathi, M., and Shabani, M. (2022). Effectiveness of telephone-based screening and triage during COVID-19 outbreak in the promoted primary healthcare system: A case study in ardabil province, Iran. J. Public Health 30 (5), 1301–1306. doi:10.1007/s10389-020-01407-8

OECD (2021a). “Business dynamism during the COVID-19 pandemic: Which policies for an inclusive recovery?,” in OECD policy responses to coronavirus (COVID-19) (Paris: OECD Publishing). doi:10.1787/f08af011-en

OECD (2020d). Job retention schemes during the COVID-19 lockdown and beyond”, OECD policy responses to coronavirus (COVID-19). Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/0853ba1d-en

OECD (2020c). OECD employment Outlook 2020: Worker security and the COVID-19 crisis. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/1686c758-en

OECD (2020a). Public employment services in the frontline for employees, job seekers and employers”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/c986ff92-en

OECD (2014). “The crisis and its aftermath: A stress test for societies and social policies,” in Society at a glance 2014: OECD social indicators (Paris: OECD Publishing). doi:10.1787/soc_glance-2014-5-en

Paulson, K. R., Kamath, A. M., Alam, T., Bienhoff, K., Abady, G. G., Abbas, J., et al. (2021). Global, regional, and national progress towards sustainable development goal 3.2 for neonatal and child health: All-cause and cause-specific mortality findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 398 (10303), 870–905. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01207-1

Rahmat, T. E., Raza, S., Zahid, H., Mohd Sobri, F., and Sidiki, S. (2022). Nexus between integrating technology readiness 2.0 index and students’ e-library services adoption amid the COVID-19 challenges: Implications based on the theory of planned behavior. J. Educ. Health Promot. 11 (1), 50. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_508_21

Rashid Khan, H. u., Awan, U., Zaman, K., Nassani, A. A., Haffar, M., and Abro, M. M. Q. (2021). Assessing hybrid solar-wind potential for industrial decarbonization strategies: Global shift to green development. Energies 14 (22), 7620. doi:10.3390/en14227620

Sedlacek, P. (2020). Lost generations of firms and aggregate labor market dynamics. J. Monetary Econ. 111, 16–31. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2019.01.007

Shoib, S., Gaitan Buitrago, J. E. T., Shuja, K. H., Aqeel, M., de Filippis, R., Abbas, J., et al. (2021). Suicidal behavior sociocultural factors in developing countries during COVID-19. L'Encephale. 47, 78–82. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2021.06.011

Soroush, A., Ziapour, A., Jahanbin, I., Andayeshgar, B., Moradi, F., and Cheraghpouran, E. (2021). Effects of group logotherapy training on self-esteem, communication skills, and impact of event scale-revised (IES-R) in older adults. Ageing Int. 46, 1–12. doi:10.1007/s12126-021-09458-2

Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Cheshmehzangi, A., Li, X., and Cai, Y. (2021a). The promise and perils of Unit 731 data to advance COVID-19 research. BMJ Glob. Health 6 (5), e004772. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004772

Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Li, X., Bennett, B., Segalo, S., Abbas, J., et al. (2021b). COVID-19 vaccine donations-vaccine empathy or vaccine diplomacy? A narrative literature review. Vaccines (Basel) 9 (9), 1024. doi:10.3390/vaccines9091024

Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Shi, L., Cai, Y., and Yang, L. (2021c). Secondhand smoke exposure of expectant mothers in China: Factoring in the role of culture in data collection. JMIR Cancer 7 (4), e24984. doi:10.2196/24984

Wachter, T. (2020). The persistent effects of initial labor market conditions for young adults and their sources. J. Econ. Perspect. 34/4, 168–194. doi:10.1257/jep.34.4.168

Wang, J., Yang, J., Iverson, B. C., and Kluender, R. (2020). Bankruptcy and the COVID-19 crisis. SSRN J (5) 31, doi:10.2139/ssrn.3690398

Yang, M., Bento, P., and Akbar, A. (2019). Does CSR influence firm performance indicators? Evidence from Chinese pharmaceutical enterprises. Sustainability 11 (20), 5656. doi:10.3390/su11205656

Yao, J., Ziapour, A., Toraji, R., and NeJhaddadgar, N. (2022). Assessing puberty-related health needs among 10–15-year-old boys: A cross-sectional study approach. Arch. Pédiatrie 29 (2), 307–311. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2021.11.018

Yoosefi Lebni, J., Abbas, J., Moradi, F., Salahshoor, M. R., Chaboksavar, F., Irandoost, S. F., et al. (2021). How the COVID-19 pandemic effected economic, social, political, and cultural factors: A lesson from Iran. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 67 (3), 298–300. doi:10.1177/0020764020939984

Yu, S., Draghici, A., Negulescu, O. H., and Ain, N. U. (2022). Social media application as a new paradigm for business communication: The role of COVID-19 knowledge, social distancing, and preventive attitudes. Front. Psychol. 13, 903082. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903082

Zhang, X., Husnain, M., Yang, H., Ullah, S., Abbas, J., and Zhang, R. (2022). Corporate business strategy and tax avoidance culture: Moderating role of gender diversity in an emerging economy (original research). Front. Psychol. 13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.827553

Keywords: unemployment, job retention schemes, economic recovery, economic environment, sustainable development, COVID-19

Citation: Naqvi HA (2022) Role of government policies to attain economic sustainability amid COVID-19 environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:983860. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.983860

Received: 01 July 2022; Accepted: 02 August 2022;

Published: 06 September 2022.

Edited by:

Jaffar Abbas, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Azhar Abbas, University of Agriculture, PakistanCopyright © 2022 Naqvi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hasnain A. Naqvi, aG5hcXZpQHVoYi5lZHUuc2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.