- 1Faculty of Applied Social Sciences (FACISA) of State University of Mato Grosso, Caceres, Brazil

- 2Business School of Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

The National School Feeding Program (PNAE—Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar) is a Brazilian policy that attends to 44 billion students per year, distributed in 5,568 municipalities, providing school meals to public school students. Law No. 11,947 establishes a minimum percentage of 30% to purchase foodstuffs directly from family farming. In addition to the general rules, it is possible to create specific rules for the operationalization of the program; therefore, this paper aims to characterize the dynamic process of the relationships and actions of social agents involved through the Activity System generated by Law No. 11,947 of 2009 in the municipality of Porto Velho in the state of Rondônia, located in the western Amazon. As a theoretical framework, cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) and mediated action theory (MAT) were used. To achieve the objective, qualitative research and abductive reasoning were adopted, using a unique and incorporated case study as a strategy. In all, 49 interviews were conducted and analyzed using content analysis. The extent of the influenced community and the different realities to which the actors are exposed were verified.

1 Introduction

The main objective of the National School Feeding Program (PNAE—Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar) is to partially meet the nutritional needs of beneficiary students by offering at least one meal a day in order to comply with the nutritional requirements for the period in which they are at school. Thus, school meals must cover at least 15% of the student’s daily nutritional needs (Silva et al., 2022). This Brazilian policy attends to 44 billion students per year, is distributed across 5,568 municipalities, and is recognized worldwide as a reference for the implementation of sustainable school feeding programs (Silva et al., 2018). It is worth mentioning that the good evaluation is due to the fact that the program has instruments that enhance access to adequate and healthy food, resulting in socially inclusive forms of production and distribution and respecting the various expressions of diversity in the process (Maluf and Luz, 2016; Silva et al., 2022).

According to Peixinho (2013), p. 910), the PNAE had its origins in the Social Security Food Service, founded in August 1940. During the 1950s, the Federal Deputy and President of the Executive Council of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Josué de Castro, aimed to raise global awareness of the problems of hunger and misery, promoting projects that highlighted hunger and its possible solution through the action and will of social actors (Peixinho, 2013, p. 910). Silva (1995), p. 88) mentions that, in 1952, the Plan of Food Conjuncture and Nutritional Problems in Brazil was prepared, which included nutritional issues, expansion of school meals, food assistance for adolescents, regional programs, enrichment of basic foods, and support for the food industry. This project resulted in the School Meal Campaign, instituted by Decree No. 37,106, instituted on 31 March 1955, by President Getúlio Vargas. In 1979, the program was renamed as the National School Feeding Program.

There were other contributions to PNAE formation, but Law No. 11,947 of 16 June 2009 brought a significant change in its execution. This law resulted from an intersectoral process involving the Federal Government and the participation of the civil society through the National Council for Food and Nutritional Security and the trade union movement organized by the National Confederation of Rural Workers Farmers and Family Farmers (CONTAG—Confederação Nacional dos Trabalhadores Rurais Agricultores e Agricultoras Familiares) and Federations of Rural Workers (FETAGs - Federações de Trabalhadores na Agricultura). During the period between 13 and 27 of May 2009, 52 hearings occurred involving more than 30 government agencies, 14 ministers, and several executive secretaries, which resulted in Provisional Measure 455/09 (MP 455/09) being approved by the Federal Senate. This Provisional Measure determined that at least 30% of the purchase of food for school meals should be from family farmers (Broch, 2009; Silva et al., 2022, p. 88).

Law No. 11,947 was the definitive institutionalization of Provisional Measure 455/09. It universalized the PNAE for all basic education, from early childhood education to high school, in addition to young people and adults. It defends food and nutrition education as a priority, thus strengthening the community’s participation in social control of the actions developed by the states, federal districts, and municipalities. Law 11,947 provides support for sustainable development, encouraging the purchase of diversified, locally produced foodstuff, respecting seasonality, culture, and food traditions in addition to prioritizing organic and/or ecological foods in menus of school meals (Peixinho, 2013, p. 913; Silva et al., 2022, p. 88).

Another positive aspect of Law No. 11,947 of 2009 was its Article 14, which created the Management Committee, formed by representatives of the Federal Government, the Consultative Group with the participation of civil society representatives, in addition to representatives of the National Council of State Secretaries of Education (CONSED—Conselho Nacional de Secretários de Educação) and the National Union of Municipal Education Directors (UNDIME—União Nacional dos Dirigentes Municipais de Educação), with the purpose of advising the Management Committee. This Law established a new composition for the School Meals Councils (CAE—Conselho de Alimentação Escolar), contemplating more representatives of teacher, student, or education worker associations, appointed by the respective professional associations. It also expanded the participation of representatives of organized civil entities, excluding the participation of representatives of the Legislative (Peixinho, 2013, p. 913; Silva et al., 2022, p. 88).

To complement the guidelines of Law No. 11,947, the National Education Development Fund (FNDE—Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação) established some resolutions that clarified some points in the execution of the PNAE. Resolution No. 26 of 17 June 2013 assisted in clearing doubts about who could meet the demand for school meals. This Resolution established that, in addition to the Declaration of Aptitude for National Program for Strengthening Family Farming (PRONAF—Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar) (DAP—Declaração de Aptidão ao PRONAF), a document that establishes a maximum quote of production to be considered for a family farmer, individual activities in rural areas are necessary, besides having an area of up to four fiscal modules, family labor, family income linked to the establishment, and management of the establishment or enterprise by the family itself. Resolution No. 26 also included family farmer foresters, aquaculturists, extractivists, fishermen, indigenous people, quilombolas (communities originated from slavery in Colonial Brazil), and agrarian reform settlers (Silva et al., 2022, p. 88).

On 3 April 2015, Resolution No. 4 improved the definition of formal and informal groups of agrarian reform settlers, traditional indigenous communities, and quilombolas and determined tie-breaking criteria to select a supplier. Another important aspect of Resolution No. 4 was the definition of individual sales limit for family farmers in marketing to the PNAE by the executing entity. It also established new rules to control the individual sales limit of family farmers and defined models for public call notices, sales project price surveys, and contracts (Silva et al., 2022, p. 89).

The last update of Law No. 11,947 occurred with Resolution No. 6, approved on 8 May 2020. One of its measures was to introduce the PNAE Card, a debit card from a current account kept by the FNDE for access to the program resources. So, in this case, to receive his payments, family farmers need a machine card (Silva et al., 2022, p. 89).

Law No. 11,947 allowed family farming to contribute to the improvement and continuity of the PNAE. The integration of school meals with family farming increases the inclusion of small farmers. This encourages products from the local economy aimed at sustainable development and non-industrialized foods for students. However, adherence to Law No. 11,947 by the municipality depends on multiple interests and social actors, such as municipal government, state government, federal government, different productive actors, union leaders, teachers, nutrition professionals, students, parents, and other institutions involved.

This diversity is affected by multiple influences and interventions, such as partisan political pressures. Each historical moment, society, and culture provides a set of mediational resources that enable action in specific contexts for each municipality in different periods. Mediation builds a link between social and historical processes on one hand and individuals’ mental processes on the other hand. From the understanding of this dynamic, through the mediation in the activity system, new paths can emerge, creating new chances to enforce the determinations of this program, which is increasingly oriented toward the path of local sustainable development. To understand this, logic studies by Engeström (2001), Engeström (2015), Sannino and Engeström (2018), Daniels et al. (2007), and Wertsch (2007) were used, as stated in Sections 2, 3.

To analyze a municipality that can characterize the largest number of activities in addition to having a greater work field to discuss sustainable development and sustainability, Porto Velho, the capital of the state of Rondônia, a state that is part of the Legal Amazon, was chosen. With an estimated population of 494,013 inhabitants (IBGE, 2017a), it is the most populous municipality in the state and the fourth most populous in the north region. It stands out for being the Brazilian state capital with the largest territorial area, covering just over 34,000 km2. It is the only state capital that borders another country, Bolivia (Velho, 2019).

PNAE resources for the municipality of Porto Velho are sent in two ways: 1) to the municipality, which manages 144 schools (SEMED, 2019), and 2) to the state, which manages 74 schools (SEDUC, 2019) in the capital. The program is managed differently by the Municipal Secretariat of Education (SEMED—Secretaria Municipal de Educação) and the State Secretariat of Education (SEDUC—Secretaria Estadual de Educação). Each department has specific decrees and laws in addition to Law 11,947, and the activities of these two systems influence the dynamics of the organization of small rural producers and communities around schools. Two activity systems can be seen in the municipality of Porto Velho, the first is SEDUC, state administration, and the second is SEMED, municipal administration. To represent the integration of actors, the cultural–historical activity theory (CHAT) was used, which provides dimensions of analysis for the groups that participate in the operationalization of the PNAE, their expectations in relation to Law No. 11,947, the laws and regulations established by the secretariats for the execution of the program, the tools used, and the community influenced by the decisions of public policy managers. It is worth mentioning that CHAT and its main points will be explained in Section 2.

Therefore, the objective of this article is to characterize the dynamic process of the relationships and actions of the social actors involved through the activity systems representing the configuration of the current moment by the fulfillment or not of the requirement of Law No. 11,947 of 2009, based on the theory of activity and in the mediated action theory (MAT). It is important to emphasize that some aspects of TMA will be discussed in Section 3.

CHAT was used to understand the organization of actors and the way public policy is conducted. It is considered essential for understanding the process of transformation and learning of activities aimed at implementing Law No. 11,947. TMA was applied to complement the institutional analysis involving events and people. Through the discourse of the members from the activity system, terms of their context were analyzed and how their practice was communicated in relation to their values, beliefs, and attitudes.

2 Cultural-historical activity theory

The cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) is the result of a school of thought based on the works of Vygotsky and Leontiev in the 1920s and 1930s. It is an effort toward sociohistorical–cultural psychology based on Marxist philosophy (Duarte, 2002; Piccolo, 2012). Engström (2001) presented a systematization of the theory and methodology around the CHAT, seeking to clarify its development. According to the author, this was an approach that evolved over three generations of research. The first generation is based on the work developed by Vygotsky (1997), emphasizing individual consciousness and activity as a way of interaction between humans and the world based on mediation artifacts. The second takes up the concept of activity and, mainly, its collective characteristics, based on the works of Leontiev (1981), as well as the contribution of Engeström, with the third generation advancing toward understanding the formation of concepts in networks of interacting activity systems (Campos et al., 2017).

The third generation of activity theory developed conceptual tools for understanding networks of activity systems in interaction, dialogue, and multiple perspectives and voices. Engeström (2015) first expanded Leontiev’s theory of activity, keeping the activity system as the basic unit of analysis, but incorporated sociocultural artifacts that should mediate the interaction between the subject and object, such as rules and division of work and community.

An activity system is understood as the context in which actions, operations, and activities are developed, that is, the minimum unit of analysis for understanding how a subject articulates collective efforts to change an object (Cole and Engeström, 1993; Hutchins, 2000; Campos, 2015). The subject is the individual who performs social and collective practical activities, consciously, whose agency is taken as a starting point for the analysis in question (Leontiev, 1981; Engeström, 2001; Campos, 2015).

The object would be the transformation of what is expected to produce: the result. It is a kind of analysis tool that allows understanding not only what individuals are doing but also the reasons for doing it (Engestrom and Blackler, 2005; Kuuti, 2010; Kaptelinin, 2005; Leontiev, 1981; Campos, 2015).

Artifacts are understood as cultural means characterized by tools and signs that individuals internalize, during socialization, through participation in common activities with other humans. It does not consist only of the material aspect but includes social or cognitive aspects, such as procedures, heuristics and scripts, routines, and languages. It is important to emphasize that these tools, procedures, regulations, processes, concepts, and practices are involved in the transformation of the practice of the activity (Vygostky, 1997; Omicini and Ossowski, 2004; Mietinen and Virkkunen, 2005; Campos, 2015).

The rules they refer to are regulations, norms, and conventions related to the context of the activity that are presented tacitly or explicitly. They must be understood from the subject’s point of view since they regulate the subject’s behavior toward the object. In general, the rules refer to formal and informal conventions, which direct the relationships between the elements in an activity system (Engeström, 2001; Virkkunen and Ristimäkki, 2012; Campos, 2015).

The Labor division comprehends tasks between subjects, existing hierarchical relationships, power relationships, and status. In this case, it is important to understand that the activity depends on its social development and the position that individuals occupy since these factors bring in themselves motives and objectives and means and ways of carrying out the activity. The labor division also determines the possibilities for the use of artifacts, depending on the social position of individuals (Bernstein, 2000; Engeström, 2001; Hasan, 2005; Virkkunen and Ristimäkki, 2012; Campos, 2015).

Community concerns all and any human activity that has a certain division of labor and is governed by rules constituted by a group of people responsible for a shared object. The community transforms the object and is responsible for the activity. The community carries an activity, and its form and limits depend on the concrete history of the activity system (Engestrom, 2001; Campos, 2015). Finally, the result is seen as the construction of desire glimpsed from an object (Mukute and Lots Sisika, 2012; Campos, 2015).

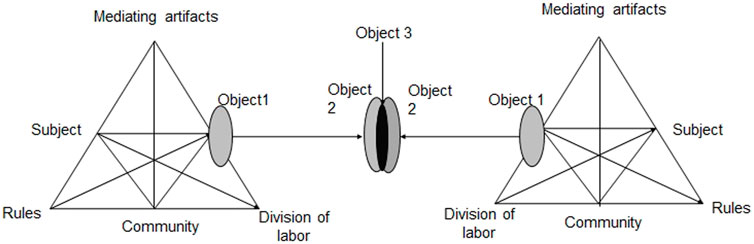

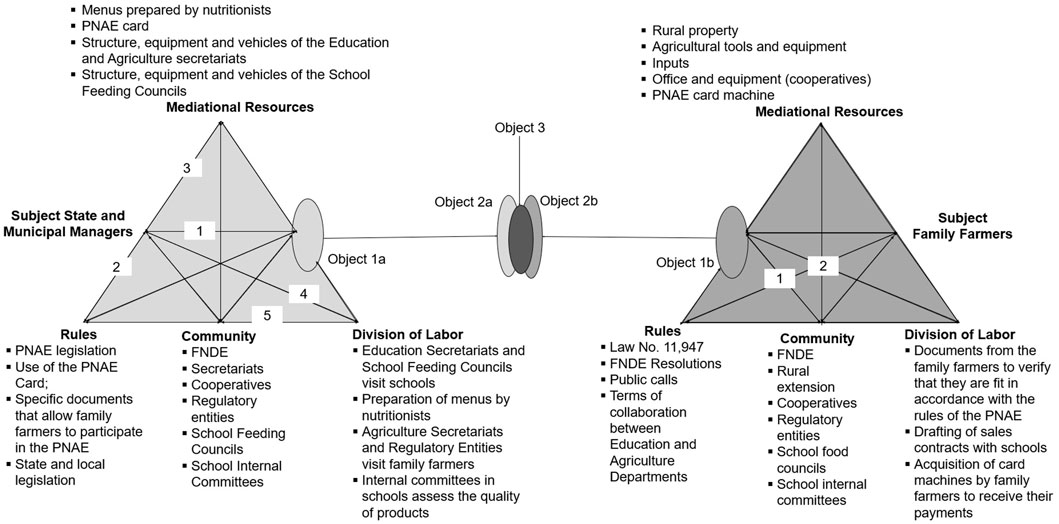

After consolidating his model, Engeström (2015) expanded it to include at least two interacting activity systems. The evolution of third-generation activity theory expands the analysis both upward and downward and outward and inward. Moving up and out, it addresses various interconnected activity systems with their partially shared and often fragmented objects. Moving downward and inward, it addresses issues of subjectivity, experience, personal meaning, emotion, embodiment, identity, and moral commitment. To bridge and integrate the two directions, serious theoretical and empirical efforts are needed (Engeström, 2015). Figure 1 shows the two interacting activity systems representing the minimum model for the third generation.

FIGURE 1. Mediation in two interacting activity systems and objects of a model for human activities. Source: Engeström (2001), p. 136).

While analyzing Figure 1, each system has its own object; however, object 3 is a specific objective in which both systems are connected. This point symbolizes the interaction of systems. The systems, in turn, interact with each other and show confrontations, which often generate opportunities for transformation (Engeström, 2001).

For Sannino and Engeström (2018), there is a global momentum for formative interventions in multi-activity constellations and coalitions that may include local communities, social movements, educational institutions, private companies, public service agencies, non-governmental organizations, associations, and administrative and political bodies of policymaking. The need for these interventions typically stems from contradictions linked to the search for social and economic equity and ecological sustainability. The revolutionary challenge for activity theory is to develop and use the conceptual foundations and methodological solutions in such interventions (Sannino and Engeström, 2018).

3 Mediated action theory

Nevertheless, in this search for conceptual foundations, the mediated action theory (MAT) proposed by Wertsch (1993) offers important elements to analyze the mediating artifacts of an activity system. According to this theory, each historical moment, each society, and each culture provide a set of mediational resources that enable action.

According to Daniels (2015), humans dominate through external symbolic and cultural systems rather than by being subjugated by and within them. This emphasis on self-building through and with the tools available brings two crucial issues to the fore. First, it speaks of the individual as an active agent in development. Second, it affirms the importance of the sociocultural context in which development takes place using tools that are available at a given time in a given place. Vygotsky distinguished between psychological tools and others and suggested that psychological tools can be used to direct mind and behavior. In contrast, technical tools are used to bring about changes in other objects (Daniels, 2015).

To investigate these mediating artifacts, Wertsch (1998), building on Kenneth Burke (1984), used five terms as generative principles. These terms are act, scene, agent, agency, and purpose. In a state guided by motives, there must be a word that names an act, that is, names the products of a given action, and another word that names the scene, which is the background of the act, which is the sociohistorical context that shapes this situation. Moreover, it must be indicated which agent or type of person executes the act and what means or instruments he uses, thus considering the agency and the objective. It is known that the purpose is the agent’s intention at the origin of the act or the intention that is stabilized during the action. Agency is characterized by the instruments used, or in other words, the mediational resources from which the act can be performed.

The task of a sociocultural approach is to explain the relationships between human action on one hand and the cultural, institutional, and historical contexts in which that action takes place on the other hand. Such a focus places less emphasis on other elements, such as scene and objective. Wertsch (1998), Wertsch (2007), and Daniels (2015) argue that it makes sense to assign the agent–instrument relationship a privileged position, at least initially, in sociocultural research, for several reasons.

First, a focus on the agent–instrument dialectic is perhaps the most direct way to overcome the limitations of methodological individualism, age, copyright, centralized mindset, and so on. An appreciation of how mediation means or cultural tools are involved in the forces of action. Therefore, the agent-instrument dialectic forces one to go beyond the individual agent when trying to understand the forces that shape human action (Wertsch, 1998; Wertsch, 2007; Daniels, 2015).

Analysis of mediated action or “agent action with mediating means” (Wertsch et al., 1993) provides important insights into other scene, purpose, and action dimensions. This is because these other elements are often shaped, or even “created” (Silverstein, 1985), by mediated action. At this point, it is not to argue that one can reduce the analysis of these other elements to that of mediated action. Burke (1984) convincingly demonstrated that this reductionism cannot work. It is to say, however, that the human action perspective comes from the agent–instrument relationship, from which it provides some important insights into the nature of other elements and relationships of analysis.

Mediated action provides a kind of natural link between action, including mental action, and the cultural, institutional, and historical contexts in which that action takes place. This occurs in this way because mediation means, or cultural tools, are inherently situated culturally, institutionally, and historically. The fact that cultural tools are involved means that the sociocultural incorporation of the action is always incorporated into the analysis (Wertsch, 1998; Wertsch, 2007).

Wertsch (1998) described a set of basic statements that characterizes mediated action and cultural tools and illustrates each statement with some concrete examples. The author examines ten basic claims: 1) mediated action, which is characterized by an irreducible tension between the agent and mediation means; 2) means of mediation, which are material; 3) mediated action usually has several simultaneous goals; 4) mediated action is situated on one or more developmental paths; 5) the means of mediation constraint and enable action; 6) the new mediation means transforming mediated action; 7) the relationship of agents in relation to the means of mediation can be characterized in terms of domain; 8) the relationship between agents and mediation means can be characterized in terms of appropriation; 9) means of mediation are often produced for reasons other than to facilitate mediated action; and 10) the means of mediation are associated with power and authority.

The mediated action, for Wertsch (1998) and Daniels (2015), can be characterized from a set of properties among which the existence of an irreducible tension between the agent and the mediational resources stands out, and these mediational resources enable but at the same time restrict action.

Analyzing an action from the point of view of the irreducible tension between the agent and mediational resource contributes, according to Wertsch (1998), to a better understanding of the other dimensions of mediated action: scene, purpose, and action. Regarding the restriction of action, the author states that even when a mediational resource creates new possibilities for action by “freeing” agents from restrictions that prevent the realization of new actions, it introduces other new restrictions that are its own.

Wertsch (1998) states that the restrictions imposed by a mediational resource on an action are usually only recognized, in retrospect, through a process of comparison that contrasts the present and past. Thus, only with the emergence of new forms of mediation do individuals become able to recognize the restrictions imposed on the actions they performed with previous mediational resources. For example, the limitations of the dial-up internet only became evident to its users after the advent of broadband.

Importantly, tensions are revealed in competing definitions of “culture” and in the labeling of contemporary theoretical approaches as, for example, sociocultural or cultural–historical. There are similar debates about the means of mediation. Some approaches tend to focus on the semiotic means of mediation (Wertsch, 1998; Daniels et al., 2007; Wertsch, 2007), while others tend to focus more on the activity itself (Engeström, 2015). Therefore, this article seeks points of convergence between the two aspects for the analysis of the results.

CHAT and mediated action theory (MAT), in addition to having the same origin, emphasize development and learning in social environments. In MAT, the focus is on mediated actions, while in CHAT, it is on culture and history. Artifacts, including language, signs, and tools, play a prominent role in both MAT and CHAT (Postholm, 2015, p. 43).

4 Methodology and methodological procedures

This article has a qualitative nature (Merriam, 2002; Sampieri et al., 2006) and employs abductive reasoning (Charreire and Durieux, 2003; Cruz, 2007, p. 53), using as a strategy the case study and data collection of primary and secondary data (Yin, 2018). The research design is descriptive research (Aaker et al., 2001; Triviños, 2007).

A single, embedded case study was chosen, as it has analysis subunits that can be incorporated into the same context, adding significant opportunities for extensive analysis and improving ideas about the single case (Yin, 2018). The main unit is the execution of the PNAE within the municipality of Porto Velho, which in turn is divided into two units of analysis: the municipal execution (SEMED) and the state execution (SEDUC). Between these two units of analysis, there are intermediate units: municipal and state schools, union leaders, and farmers. Union leaders and farmers participate in the two main units of analysis within the same context. Therefore, this justifies the choice of the single, embedded case study design.

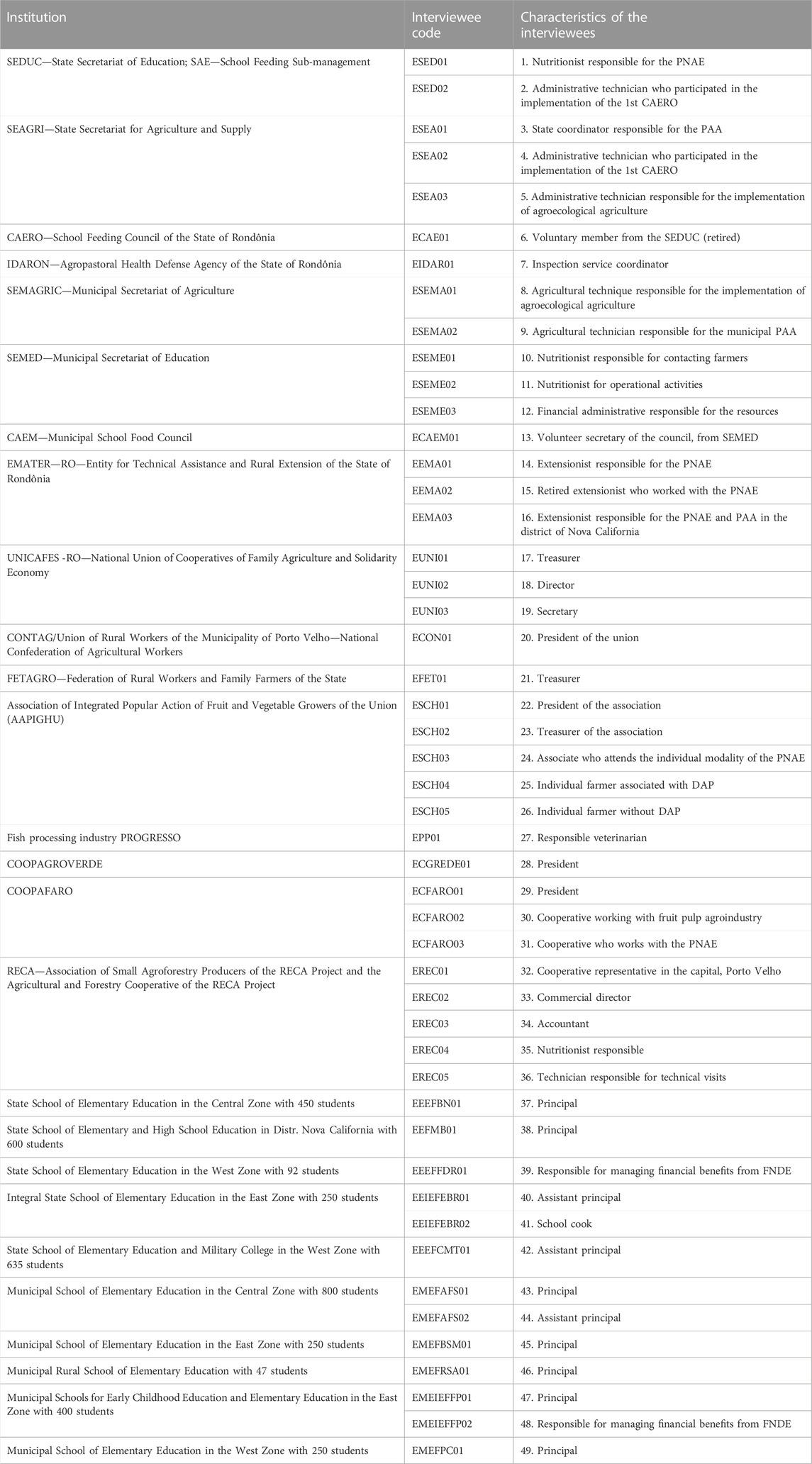

First, visits were made to SEMED and SEDUC to have a preliminary mapping of who would be the main actors involved with the historical process related to the PNAE in the municipality of Porto Velho. Through the study of specific legislation and consultation with nutritionists coordinating the program in the state of Rondônia and in the municipality of Porto Velho, 49 interviewees were recruited, as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Interviewees, institutions, and functions that interact in the PNAE (National School Feeding Program) in the municipality of Porto Velho, State of Rondônia, Brazil.

It is important to note that the interviews took place in four periods: May and October 2019, which were resumed between January and March 2020, and finally, due to the coronavirus pandemic, it was decided to return to the field between May and September 2020 to register changes in the execution of the PNAE. Therefore, the characteristics exposed thus far denote research of an abductive nature.

The interviews were semi-structured, and non-participant observation was used, in which the researcher assumes the role of the participant as an observer, a technique with less involvement of the researcher in the field, given that the interest is in observation and not in acting in this field (Flick, 2009). Thus, the interviews and the observation process were documented using field notes (Lofland, 1974; Lofland and Lofland, 1995). In addition to the interviews and observations, 83 documents were analyzed, including internal documents, legislation, and regulations.

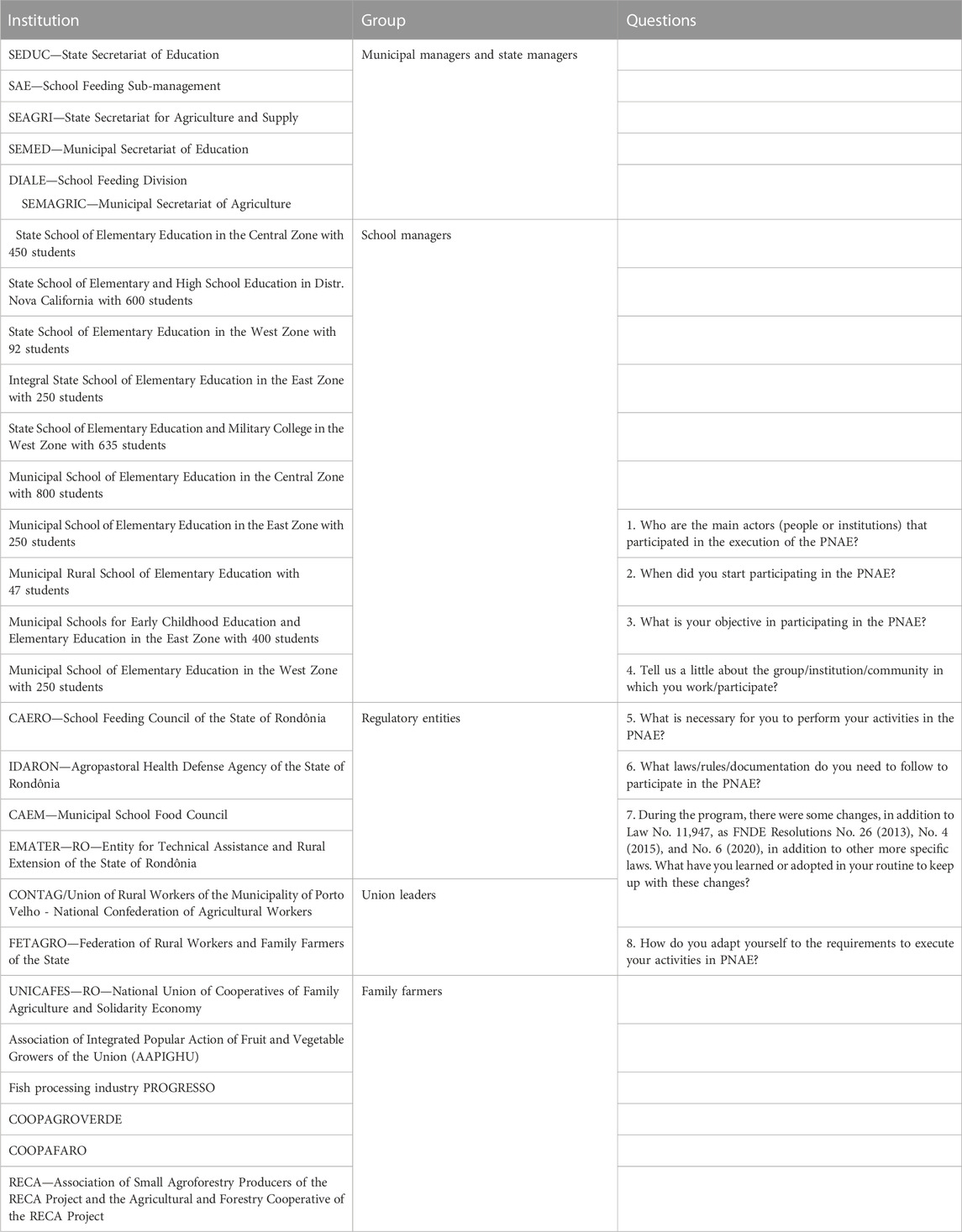

To analyze the activity system, two interview scripts were prepared for each identified group. Open questions were chosen, allowing the interviewees to feel free to add information that they considered relevant, especially to identify some tensions in performing their activities. The interviewees were divided into municipal managers and state managers, school managers, regulatory entities, family farmers, and union leaders.

The first script was directed to all groups. Its objective was to cross information from different points of view to describe the aspects of the activity system. Table 2 shows the issues addressed and to which group they were addressed.

TABLE 2. Interview script 1 for all groups of the PNAE (National School Feeding Program) in the municipality of Porto Velho, State of Rondônia (Brazil), aiming to characterize the activity system generated by Law No. 11,947.

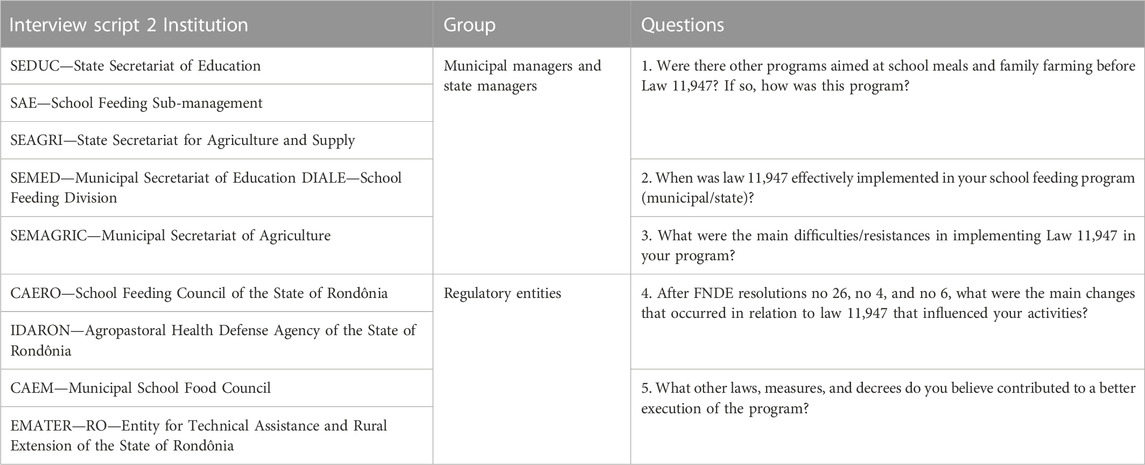

The second interview script was directed to municipal managers and state managers and regulatory entities groups. Its objective was to identify their division of work, rules, and legislation complementary to Law No. 11,947, in addition to mediation resources. Table 3 shows the issues addressed and to which group they were directed.

TABLE 3. Interview script 2 for municipal managers and state managers and regulatory entities groups of the PNAE (National School Feeding Program) in the municipality of Porto Velho, State of Rondônia (Brazil), aiming to characterize the activity system generated by Law No. 11,947.

The analysis of the collected data took place through content analysis, whose operation and objective are a set of communication analysis techniques aiming to obtain, through systematic procedures and objectives, the description of the content of the messages, indicators that allow the inference of knowledge regarding the production/reception conditions (inferred variables) of these messages (Bardin, 2011).

In the context of this article and based on Bardin (2011), a treatment of data analyses was used that included a rereading of documents and transcriptions from interviews, establishing codes for the formulation of categories of analysis through the theoretical framework, in this case, CHAT and mediated action theory.

5 Activity system in Porto Velho

Porto Velho is a Brazilian municipality and capital of the state of Rondônia. PNAE resources are sent to the municipal government, which manages 144 schools (SEMED, 2019), and to the state government, which manages 74 schools (SEMED, 2019) in the capital. The program is managed differently by the Municipal Secretariat of Education (SEMED) and the State Secretariat of Education (SEDUC). Each secretariat has specific decrees and laws in addition to Law No. 11,947, and the activities of these two incorporated activity systems influence the dynamics of the organization of small rural producers and communities around schools.

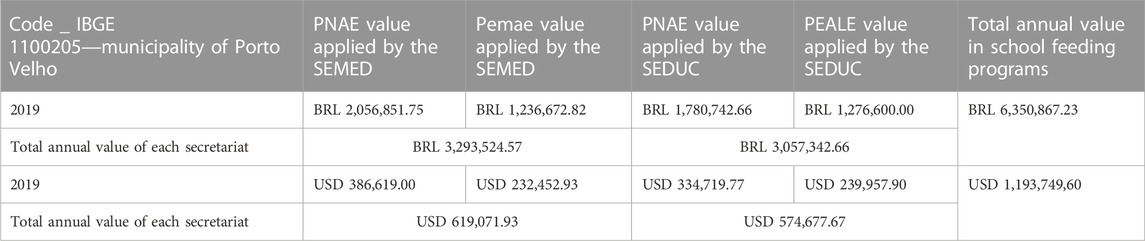

In 2019, the FNDE transferred BRL 4,380,008.00, in U.S. dollars, equivalent to USD 823,294.30, to municipal schools, and the SEMED, through the Municipal School Feeding Program (PMAE—Programa Municipal de Alimentação Escolar), presented the counterpart in the amount of BRL 2,633,460.00, in U.S. dollars, equivalent to USD 495,001.97, totaling BRL $$7,013,468.00, or USD 1,318,296,27, transferred to school meals (SEMED, 2019). Considering that the SEMED invests the same percentage of family farming (46.96%) as the PNAE in the PMAE, in 2019, approximately BRL 2,056,851.75, in U.S. dollars, equivalent to USD 386,619,00, were transferred.

While the SEDUC, in 2019, received BRL 15,793,795.20, or USD 2,968,702,69, from the FNDE regarding the PNAE, the state of Rondônia offered the complementation through the State School Feeding Program (PEALE—Programa Estadual de Alimentação Escolar), for the supply of fish, the amount of BRL 7,269,761.20, or USD 1,366,470.78. These values met 330 school councils distributed in schools throughout the state of Rondônia. Financial resources were transferred to 312 school councils for the acquisition of fish to complement the school meals (SEDUC, 2020). It is worth mentioning that this value refers to the state of Rondônia; 30% of this amount is applied in the municipality of Porto Velho.

It is also worth considering the impact of regional feeding programs on farmers. For example, PEALE, a state program, in 2019, supplemented the purchase of fish in school meals for 191,934 students, totaling the transfer value to the execution units of BRL 3,867,626.00, or USD 726,983.70 (SEDUC, 2020); that is, 53.20% of PEALE are destined for family agroindustry. In the municipality of Porto Velho alone, approximately BRL$ 1,276,600.00 or USD 239,957.90, was spent.

Therefore, it can be inferred that between the execution of Law No. 11,947 by the Education Departments and regional programs together, the annual transfer to family agriculture reaches BRL 6,350,867.23 or USD 1,193,749.60. Table 4 shows the distribution of values for each program managed by the education secretariats.

TABLE 4. Investments in family farming products used in school meals made by education secretariats during 2019—in reais and US dollars—in the PNAE (National School Feeding Program) in the municipality of Porto Velho, State of Rondônia, Brazil.

It is worth mentioning that all values in U.S. dollars were based on the quotation value of 14 November 2022.

Education secretariats are the most important social actors in the implementation of Law No. 11,947. In the municipality of Porto Velho, as previously mentioned, the SEDUC and SEMED do not have shared management of schools; in other words, each secretariat is responsible for its group, in this case state schools and municipal schools. Therefore, to better understand the municipality’s CHAT, it is necessary to analyze municipal and state management separately.

Initially, contact was made with the Municipal Secretariat of Education (SEMED). Ten interviews were conducted with three respondents in different periods between 2019 and 2020. The municipal education network of Porto Velho, according to the 2019 census of the National Fund for the Development of Education (FNDE), has 50,210 students. These students are distributed in 144 school units and are attended by centralized, decentralized, and private/affiliated school units. Centralized school units are those that do not have a formed school council, and there are 15 schools in this modality in the municipality. The decentralized school units have a formed school council, represented by 124 schools, while there are five private/affiliated school units (SEMED, 2019).

Understanding this classification is important for the scope of the PNAE, as it determines how the Secretariat of Education will act. For example, in centralized units, the SEMED purchases foodstuffs and distributes them. In decentralized units, resources are made available for the school unit itself to purchase foodstuffs. Private educational institutions, on the other hand, make an agreement with the SEMED to receive only PNAE resources.

To manage activities related to the PNAE, the SEMED counts on a specific department, the School Feeding Division (DIALE—Divisão de Alimentação Escolar). The DIALE is composed of 15 employees: a manager responsible for the division, five nutritionists, and nine employees distributed in administrative functions. The department serves an average of 15–20 people daily, including principals, schoolteachers, suppliers, and the community in general, with two service teams in two shifts: morning and afternoon (SEMED, 2019).

The duties performed by nutritionists range from supervising and visiting schools in the municipal education network; developing, monitoring, and evaluating the school meal menu; planning, coordinating, and supervising the application of the acceptability test of the menus practiced; elaborating and implementing the Manual of Good Practices for School Feeding Services; performing the sensorial analyses of the samples of the foodstuffs of the schools; interacting with family farmers and rural family entrepreneurs and their organizations; planning, coordinating, and executing training programs for school cooks and school unit managers; and promoting and coordinating nutritional assessment programs.

Regarding public calls, in decentralized management, each executing unit is responsible for its call. The buyer, in this case, is the school, and the supplier signs the contract that establishes the delivery schedule of the products, the payment date, and all other purchase and sale clauses with the principal (SEMED, 2019).

For the public call to take place, it is necessary to formulate a universal price list which will serve all schools in the municipal education network. Until 2019, the SEMED performed price surveys to formulate the amount to be paid for family farming products, and at least three surveys were performed in the local or regional market. For organic or agroecological products, if there was no way to research the price, it was possible to overprice by up to 30% in relation to conventional products. The formulation process has not changed, but as of 2020, this price survey was performed by a Municipal Secretariat of Agriculture (SEMAGRIC—Secretaria Municipal de Agricultura) employee. Farmers, to participate in the public call, need to present the project for sale, which is made by the Municipal Entity of Technical Assistance and Rural Extension (EMATER—Entidade Autárquica de Assistência Técnica e Extensão Rural), together with the documentation required by the DIALE. The nutritionists assessed whether the producer was able to participate in the PNAE.

Another very important actor is the Municipal School Feeding Council (CAEM—Conselho Municipal de Alimentação Escolar). The council is installed in a room in the SEMED building and receives logistical support from the secretariat. The CAEM inspects both the PNAE and the PMAE. There is the School Food Council of the State of Rondônia (CAERO—Conselho de Alimentação Escolar do Estado de Rondônia), but it works in state schools throughout the state. The two councils are not related.

To have a perception of the schools, five principals from the municipal scope were interviewed. The schools were selected with the aim of showing different realities within the execution of the PNAE. All had a School Council, which has the National Registry of Legal Entities (CNPJ—Cadastro Nacional da Pessoa Jurídica), and is subdivided into commissions to manage resources, buy food, and receive and check the products.

At the State Secretariat of Education (SEDUC), seven interviews were conducted with two respondents in different periods between 2019 and 2020. The state education network, according to the 2019 census of the National Fund for the Development of Education (FNDE), consists of 301 thousand students, and 63,810 thousand students (FNDE, 2020) are concentrated in the municipality of Porto Velho. Among the 74 schools allocated in the municipality, five were selected.

In addition to the municipal schools visited, school units with a school council were chosen. The constitution of the School Council is practically the same in relation to schools linked to the SEMED. State schools are subject to the SEDUC. Within the Secretariat, there is the Program Management, which is responsible for planning, organizing, and coordinating administrative actions and activities concerning the programs and projects under its responsibility, guiding, monitoring, and consolidating results in management reports, providing monitoring instruments, and monitoring the approvals of the rendering of accounts of the resources transferred from the programs carried out by the School Units of the State Public Network and the Regional Education Coordinations (CREs—Coordenadorias Regionais de Educação). The School Feeding Program Monitoring Sub-management is one of the units of this management, which is responsible for coordinating, planning, executing, supervising, and controlling the activities that ensure the quality standard of the food offered to the student clientele of the state education network (Rondônia, 2018).

School Feeding Sub-management (SAE—Subgerência de Alimentação Escolar) has 11 employees: four administrative technicians, two nutritionists, four commissioned employees (technical advisors trained in nutrition), and one intern. The sub-management has the support of the Nucleus of the National School Feeding Program, which is responsible for calculating and transferring financial resources from the PNAE intended for the acquisition, by schools, of food for school lunches, and the Nucleus of the State School Feeding Program, which is responsible for calculating and transferring financial resources from the State Treasury, intended to complement the school meals of Schools of the State Public Network (Rondônia, 2018).

The SEDUC also has other bodies to carry out the public call, one of which is the State Superintendence of Purchases and Tenders (SUPEL—Superintendência Estadual de Licitações), which receives documents from farmers (Rondônia, 2019). To analyze the Documents for Accreditation, a Judging Committee is appointed by means of an ordinance issued by the Secretary of State for Education, which will examine the documentation required for accreditation purposes regarding compliance with the conditions established in the Term of Reference and its respective notice within 5 days. The interested farmer must deliver all the relevant documentation in a single act, and fractional delivery is not allowed. After analyzing the documentation presented, if lack or divergence of documents is found, a period of 5 days will be granted for the missing documentation to be presented. The formalization of accreditation will take place through a specific administrative contract, the draft of which will be attached to the Public Notice (Rondônia, 2019).

Until 2019, the SEDUC performed its price survey for the purchase of family farming products, but it agreed through the Technical Cooperation Agreement 9969789 between the SEDUC and State Secretariat for Agriculture and Supply (SEAGRI—Secretaria de Estado da Agricultura e Abastecimento) that as of 2020, the price list would be made by the SEAGRI, based on the same methodology used in the state Food Acquisition Program (PAA—Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos). This table has already been updated in Public Call Notice no. 008/2020/CEL/SUPEL/RO.

It was observed that there is a commitment to sanitary issues, and at this point, both municipal management and state management are intertwined, as the farmer certified by the Municipal Inspection Service (SIM—Serviço de Inspeção Municipal), issued by the responsible department at the SEMAGRIC, can participate in the public call of the state; he just cannot sell outside the municipality. The opposite can occur: the rural entrepreneur can have the State Inspection Service (SIE—Serviço de Inspeção Estadual), issued by Agropastoral Health Defense Agency of the State of Rondônia (IDARON—Agência de Defesa Sanitária Agropastoril do Estado de Rondônia), and participate in the public call for the municipality.

Reinforcing the issue of standardization for the execution of the PNAE, there is an institution responsible for inspecting, deliberating, and advising the National School Feeding Program, and the state has the support of the School Feeding Council of Rondônia (CAERO). The CAERO was established by Complementary Law No. 177 of 9 July 1997, revoked by Complementary Law No. 235 of 18 October 2000, under the new term Complementary Law No. 238 of 22 December 2000, and in accordance with Article 18 of Federal Law No. 11,947, as well as the provisions of Article 35 of FNDE Resolution No. 26 (CAERO, 2016).

After introducing the actors of the first activity system, it is important to know the actors that are part of the Family Farmers System. This system has different expectations regarding Law No. 11,947. These actors interact with the SEMED and SEDUC and constitute a small number of organizations, considering the size of the municipality.

During the data collection, the importance of portraying the history of each of its actors was perceived, as this reflects on the way they interpret the rules and how they conduct their activities. The importance of union entities responsible for introducing public policies in the municipality aimed at family farmers was emphasized. In addition to its performance in the defense of peasant rights, this is reflected in institutional processes at the SEMED and SEDUC.

The Union Movement of Rural Workers seeks the development of the countryside through the valorization of family farming, with the strategic and central objective of promoting food sovereignty and living and working conditions with justice and dignity. In Porto Velho, although the Union was founded in 1984, it was reactivated in 2004. It was very important in the implementation of the Food Purchase Program (PAA—Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos) and in the guidance for the execution of Law No. 11.947, as reported by interviewee ECON01:

“When we started the articulation of PAA with CONAB. From then on, all this time, we passed public policies in favor of riverside people, in the districts, everything, dealing directly with family farming, the planting of beans, and every kind of foodstuff that they could produce. Working on monoculture, we created the concept of food security in 2007 so that the resource of the popular restaurant depended on this Food Security Council for the resource. I came to make part of this Popular Restaurant. It was all our participation; we had one restaurant” (Interviewee ECON01).

FETAGRO is also part of the Rural Workers’ Union Movement (MSTTR—Movimento Sindical dos Trabalhadores e Trabalhadoras Rurais). Affiliated with CONTAG and the Single Workers’ Center (CUT—Central Única dos Trabalhadores), it is a non-economic union entity, constituted for the purpose of studying, defending, and coordinating the individual and collective interests of rural workers, managed by a Board of Directors composed of ten members and supervised by a Fiscal Council. The FETAGRO was founded on 23 June 1993 in Ji-Paraná—RO in the state of Rondônia (FETAGRO, 2020). Although its headquarters are not in Porto Velho, it influences the municipality’s agricultural production, as it works in partnership with the SEAGRI to prepare the price list for products from family farming. Table of values used in PAA, and from 2020 onward, it became part of the public call for the PNAE and PEALE.

EMATER, another actor of paramount importance for the operation of the activity system, through its extension, contacts all farmers in the municipality. It is the one that assesses whether the producer is able to receive the DAP and, consequently, makes it possible for the producer to enter various public policies. These farmers, although they are part of family farming, have different profiles and interests and are organized in different ways. These convergences and divergences give dynamism to the activity system.

To collaborate with land tenure regularization, formulation, and execution of technical assistance and rural extension policies, EMATER aims to socialize technical, economic, social, and environmental knowledge to provide technical assistance to increase the production and productivity of sustainable agricultural activities and improve living conditions in rural areas of the State. In this research, two EMATER offices were visited: one in the city of Porto Velho and the other in the district of Nova California.

In this context, a federation of cooperatives emerged, the National Union of Family Agriculture and Solidarity Economy Cooperatives (UNICAFES—União Nacional das Cooperativas de Agricultura Familiar e Economia Solidária), which was founded in June 2005 in the city of Luziânia, state of Goiás. Currently, with 19 state UNICAFES, one of which is in the state of Rondônia. In Rondônia, it was established in 2014 to serve production cooperatives in the Ji-Paraná region (UNICAFES, 2017). According to the three representatives interviewed, it is a federative system with several institutions with legal personality, representing the cooperatives and offering support for products and services for their better organization.

UNICAFES, according to interviewee EUNI03, solidarity economy cooperatives must generate results from people, people being the focus, and the financial result comes automatically, “So it is the financial, the economic, the social, and the strategic moving forward together.” There are two cooperatives affiliated with the federation in the municipality of Porto Velho. The Cooperativa Agrossustentável de União Bandeirantes (UNICOOP—Cooperativa Agrossustentável de União Bandeirantes), located in the district of União Bandeirantes, was founded in 2017 and consists of two employees and 29 members. The Cooperative of Rural Producers of Porto Verde (COOPPVERDE—Cooperativa dos Produtores Rurais do Porto Verde), located in greater Porto Velho, was founded in 2013 and consists of 20 members.

These two cooperatives serve the PNAE, both the SEDUC and SEMED. To market their products, they participate in public calls for their own social reasons. There is a future interest on the part of UNICAFES in competing in public calls as a federation, as they would be able to offer a greater number of products, working with all the affiliated cooperatives to meet the demand.

In addition to all these marketing, training, and technical assistance roles for affiliated cooperatives, UNICAFES participates in pricing family farming products in the state. It is one of the institutions, together with FETAGRO and SEAGRI, which is part of the price research commission of the PAA and, in 2020, PNAE, contributing to the SEDUC public call.

However, a federation of cooperatives is a part of the activity system, and there are other cooperatives with different stories. One of them is the Consortium and Dense Economic Reforestation Project (RECA—Reflorestamento Econômico Consorciado e Adensado), which performs an agroforestry production proposal based on associativism and valorization of the forest as an alternative to deforestation. Although the Nova California district is part of the municipality of Porto Velho-RO, it is located 360 km from the capital and 150 km from the capital of Acre, Rio Branco. The RECA Project has 264 members and 144 cooperative members. Associates receive technical assistance and training, while cooperative members are those who can sell their products.

It is important to emphasize that of the 144 cooperative members, 40 farmers have the seal of organic production acquired through the Audit Certification of the Biodynamic Institute for Rural Development (IBD—Instituto Biodinâmico de Desenvolvimento Rural). Currently, not all producers associated with the RECA Project are part of the group of organic and agroecological producers, but an increase is expected in the number of participants by encouraging the agroecological transition and rescuing traditional knowledge with the adoption of alternative practices that provide more sustainable and healthy production (RECA, 2020).

RECA participates in the PNAE in two ways: one is through organic fruit pulp and the other is through the initiative of its members to participate individually in the public call, as the cooperative’s bylaws allow this. In the first case, the pulps, there is a cooperative member located in Porto Velho, which has an entire storage and distribution structure for schools in the capital. This cooperative member goes to the headquarters twice a month, carrying his own refrigerated truck.

At first, before going to the field, it was believed that RECA participated in the public calls of the SEMED and SEDUC, only with fruit pulp, but in the group interview with RECA representatives, it was discovered that the cooperative members delivered other products in schools in the region:

“We deliver pulp to schools, but our producers here deliver much more than that. Because our producers are registered directly, as individuals, they do not go through here. They go to EMATER to do their project, and they deliver directly to schools. pineapple, manioc flour, these things they deliver directly there” (Interviewee EREC03).

There is a partnership between EMATER and the schools to enable the execution of Law No. 11,947 in the district. Due to the distance from the capital, there is an employee of a municipal school who takes the projects to the SEMED. Projects to serve state schools are delivered in the district of Extrema at the Regional Education Coordination (CRE), 18 km from the district of Nova California. The aim is to serve schools in the region.

There are several partnerships between the actors of the Family Farmers System. An example of a public–private partnership was what happened with Pescado Progresso, the first agro-industry of fish affiliated with the Rondonia State Pulp Products Cooperative (COOPAGROVERDE—Cooperativa de Produtos de Polpas do Estado de Rondônia), which received some equipment from SEMAGRIC, as well as some equipment donated by the SEAGRI. Although the founder had incentives, she used her own resources to make her family agroindustry-viable.

In 2013, under the guidance of EMATER, Pescados Progresso began to deliver surplus production to PAA, and in the following year, it was inserted into the National School Feeding Program (PNAE), increasing its income from commercialization of fresh fish. In 2016, the agro-industry received equipment donations. However, it was through State Decree No. 22,179 of 8 August 2017, which included fish from the region, such as Tambaqui, Pirarucu, and Pintado in the form of fillet and pulp, in the school meals menu of public educational institutions in the state, and it was responsible for an expansion to the Pescados Progresso. This decree establishes that the SEDUC transfers the amount of BRL 2.00 per month/student to the executing unit. BRL 2.00 corresponds to around USD .38. Interviewee EPP01 reports the benefits generated by the decree:

“It was a leap. Because this law, as I can say, it supported, it earmarked an exclusive resource for fish and that was very good because it encouraged children to eat fish. Because many students did not know what a fish was. Because fish is a food that has the risk of spine and ours is without spine, we work with Tambaqui, Pirarucu, Jatuarana, Pintado, and Dourado. Today, we are reference in the State of Rondônia” (Interviewee EPP01).

According to interviewee EPP01, Pescados Progresso receives fish from 35 to 40 producers spread throughout the state. The number of employees to carry out the processing varies according to the demand. The collaborators are families who live on Linha Progresso in the Ronaldo Aragão neighborhood, east of the capital. Even the name of the agroindustry originated because of the road. In this same region, approximately 2 km away, is the Cooperative of Pulp Products of the State of Rondônia (COOPAGROVERDE).

COOPAGROVERDE was founded on 2 June 2015, with the aim of serving the PNAE, initially with a family and today with 62 cooperative members serving 140 municipal and state schools. The cooperative offers fruits, vegetables, roots, tubers, vegetables, and fresh vegetables, as well as eight flavors of fruit pulp, yogurt, and bread.

Law No. 11,947 made it possible to open other cooperatives in the municipality, such as the Cooperative of Agricultural Products and Services for Family Farmers of the State of Rondônia (COOPAFARO—Cooperativa de Produtos e Serviços Agrícolas de Agricultores Familiares do Estado de Rondônia), founded on 15 December 2015, initially with 15 members in Joana D’arc settlement, 80 km from the urban perimeter of Porto Velho. Currently, COOPAFARO has 70 members with DAP, with 15 members working in logistics in six delivery lines to 40 schools. They serve the program with a list of 108 products, which range from fruit pulp to fruits and vegetables.

Cooperatives have a reality, but there is another type of farmer who also meets public policies; they are individual farmers. These farmers participate in several informal groups, where they meet to have learning experiences, negotiate their products and inputs, attend the same church, and have the same social routine. To gain access to this profile, one of the associations located in Setor Chacareiro, Jardim Santana, east of Porto Velho, was visited. The area is occupied by approximately 600 families of family farmers and has been a disputed zone since 1997. During conflicts, farmers seek to consolidate a greenbelt so that they can remain in the area. This fact is what makes the producers join the Association of Integrated Popular Action of Fruit and Vegetables of the Union (AAPIGHU—Associação de Ação Popular Integrada de Hortifrutigranjeiros da União). The association has approximately 200 members, of which 42 have DAP and are enrolled in public policies such as PAA and PNAE. To obtain an idea of how they interact with these public policies, especially with the PNAE, five individual farmers associated with AAPIGHU were selected.

All the situations presented led to the reflection that there is a connection between the farmer and the land, his work instruments, and the social relations that emerged from Law No. 11,947. The Municipal Activity System emerges from the connection between the Municipal and State Management System, which includes SEMED, SEMAGRIC, SEDUC, CRE of Porto Velho, SUPEL, SEAGRI, and IDARON. CAERO and CAEM become part of the community. The Family Farmers System is integrated by EMATER-RO, Rural Workers Union, FETAGRO, UNICAFES, cooperatives, Pescados Progresso, and individual farmers.

After this first step characterizing the activity system through the CHAT, cultural, historical, and institutional forces were considered according to the five research principles proposed by Wertsch (1998), as seen in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2. Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) and mediated action theory (MAT) used to characterize the activity system generated by Law No. 11,947 in the municipality of Porto Velho, State of Rondônia, Brazil.

In the Municipal and State Management System, five tensions were identified, as shown in Figure 2. The tension identified by number 1 refers to the interaction between managers and nutritionists and is one of the mediational resources used. Nutritionists complain about the lack of support for their activities. It is believed that during the change of managers, they are forced to take a political position; if they present a neutral position or contrary to the manager’s political aspect, they feel that there are no incentives to expand the program, such as increasing the percentage of participation of family farming in the execution of the PNAE. This difficulty is directly related to the properties of mediated action, which state that means of mediation are often produced for other reasons that do not facilitate mediated action and that means of mediation are often associated with power and authority. Tension 1 was reflected in another element of the activity: the object. This shows that when there is political interest behind the execution of a program, the main objective can be affected. The nutritionists’ reports clearly show the following:

“The issue is political visibility, politically, then it becomes a matter of politics, when we start to show that we are not political. “people lock you in a cage” so you do not show up” (Interviewee ESEME02).

“The issue of difficulty is management itself. With a manager who has a purpose, we can make the program and execute it perfectly, while a manager without purpose ends the program. People in Brazil have a very big identity crisis, and there are divisions. I think there are good things here and good things there, so we have to get together and do it. Therefore, family farming, speaking very clearly. there is no denying it, it had a bias from the PT (Workers’ Party) and those close to it that came, it was through public policy investment that there was, this “boom”. However, we had N problems, and we are still reaping. In addition, I see that whoever is there today has to be willing to organize more, so as not to harm, it happens that the big ones have benefits where they are not supposed to be right. So that politics does not happen in the form of a diversion, in the form of a diversion of interest, diversion of money destined for those who have to be, that politics truly does not just stay in ‘blabla’ and actually happens. Because every business that they want to show at the beginning starts right, but after it is implemented, errors start to appear, and then the program loses its objective” (Interviewee ESEME01).

Number 2 concerns the other tension between managers and nutritionists, which affects the subject relationship and rules of the activity system. The nutritionist at the SEDUC reports that the number of nutritionists is not ideal, as recommended by the FNDE. Although there was an evolution in the secretariat, because until 2017 there was no position of nutritionist in the education department, there are still many gaps to be solved. Many activities are no longer carried out due to the number of nutritionists, but to hire more professionals in the area, it is necessary to change State Law No. 680 of 7 September 2012, which establishes SEDUC’s career plan, positions, and remuneration for professionals in basic education. There is a conflict between state law and federal law.

There was tension between managers and the CAEM over mediating artifacts, represented by the number 3. The counselor reports that the CAEM had its own car with a driver to perform inspections at schools, but the car was removed. For inspections, counselors have to make a request to the secretariat informing the day and the itinerary for a car with a driver to be reserved.

Tension number 4 refers to the interaction between the subject and division of labor. With the reduced number of employees, principals have to make adjustments to the school routine and often to the routine itself, as there are cases in which the principal helps with kitchen tasks, in addition to hampering other administrative activities related to the backlog of work. The managers and their teams organize the receiving commissions, the bidding commission, and the fiscal council, and any lack makes it impossible to function properly. Finally, tension is produced by mediations that often occur for reasons that do not facilitate mediated action (lack of servants) and by mediations associated with power and authority (lack of public selection process). The following fragments are nutritionists’ perceptions of the difficulty faced by principals.

“You saw the principal saying, that there is only one school cook, there is a large number of meals, in addition to the preparation, then you have to clean everything, only one person, so the work is very big. The school cooks get sick, there is no structure in all schools, some even have a good kitchen, but it is not general. So, there is a school here, the kitchen is very small, very hot. many school cooks are hypertensive, obese, there is no exhaust fan, sometimes there is no fan. No, this is not general; there are some schools that have a good kitchen. They get sick, and there is no one to take the place. Therefore, it is difficult, and the number of nutritionists is also small. There is a lot to do” (Interviewee ESEME02).

“In fact, as most schools lack employees, so it ends up that each one within their attribution, I believe that they do not develop their work in the way it should be done” (Interviewee ESED01).

Tension number 5 refers to the interaction between the CAEM and the community, which affects the division of labor in the activity system. The counselor reports the difficulty of bringing new members to the council, especially councilors who are not linked to the civil service. Interviewee ECAEM01 says that there is a schedule to be followed and that it is necessary to be available for inspections. This difficulty is directly related to the properties of mediated action that affirm the means of mediation restrict and enable action. Here is a snippet of the interview:

“We actively have two mothers, right. However, we have difficulty to bring other parents. By the bylaws, in the absence in two consecutive meetings the counselor is replaced, and a replacement is requested. Therefore, we are at fault right now with the replacement resolution. Because I’m going to tell you it is difficult... for you to have an idea, the last meeting of the last council election the last council formation in 2017 we made the requests through the secretariat, right, the request was made in the schools to gather the councils and send me to a single meeting and an assembly so that there is a manifestation of participating in the council. We are seeing how we are going to do it so that the parents can participate; they are not employees, so there is no way I can demand a father from a student from a mother. We cannot charge this person to be here, to comply with this inspection schedule” (Interviewee ECAEM01).

The tensions presented hinder the execution of the PNAE, consequently affecting the execution of Law No. 11,947; they are inherent conflicts between the actors of the Municipal and State Management System. On the other hand, the Family Farmers System also has its contradictions.

In the Family Farmers System, tension 1 is observed, which in turn refers to the interaction between rules, community, and subject. It stems from a norm that affects the object, or even the result, directly affecting the farmer and his reaction with the other actors. The analysis reveals a mediated action that has several simultaneous objectives and that this means of mediation restricts and enables the action. Bringing this to the reality of the PNAE would be the Declaration of Aptitude for PRONAF (DAP), which is one of the requirements to participate in the program, that is, a document that establishes a maximum quote of production to be considered a family farmer.

EMATER is careful to issue DAPs, as an irregular DAP for an individual who is not a producer is a crime. There is great interest in acquiring the DAP because, in addition to the PNAE, the farmer has access to PRONAF credit lines and at least 15 other public policies from the federal, state, and municipal governments. Interviewees EEMA01 and ESED02 explain the seriousness of DAP:

“What happens, for the producer to participate in the program, he must have the DAP, declaration of aptitude from PRONAF. In addition, for him to have the DAP, he has to go to EMATER and then EMATER goes to his property and does the survey to see what he has and what he can be delivering with better quality. [...] The DAP checks it out, it involves my CPF or CNPJ of my company I can never make a DAP inside my office. For me to do a DAP, I have to go to your property, I have to check, I have to see” (Interviewee EEMA01).

“We have to follow certain bureaucratic procedures, including that everyone has DAP, which is known by EMATER colleagues who have a whole job of verifying that this producer is truly a producer of what he is saying, for us to eliminate the middleman, which is a very widespread figure, including in the problems of outsourcing cooperatives that you saw in the South and Southeast” (Interviewee ESED02).

It is true that to receive the DAP, the farmer must have a Family Unit of Agricultural Production (UFPA—Unidade Familiar de Produção Agrária), which would be a group of individuals composed of a family that works with production factors to meet their own subsistence and demand of society for food and other goods and services and who resides in the establishment or place close to it (BRASIL, 2018). One of the requirements is that the family depends on the income generated by the UFPA.

The DAP works as if it were an identity for the family farmer, but it cannot encompass all types of farmers. Nothing prevents a woman from holding the main DAP or holding an accessory DAP, such as DAP Woman, as long as the main income comes from the property. However, there are cases where the husband works outside the home and the wife manages the property. In these cases, the man’s income is greater than the income generated by the property, so this family is not entitled to the declaration. The report of interviewee ESCH05, a resident of Setor Chacareiro, is about the cancellation of her DAP because in 2020, with her husband’s salary increase, she could not meet the main requirement to receive the statement:

“I did the DAP, I did the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR—Cadastro Ambiental Rural), but I never joined the program, I never sold anything, so I needed the DAP and now to go buy corn because I already bought it. With DAP, I only bought corn at National Supply Company (CONAB—Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento). It is renewed here every 2 years, I renewed it, so when I went to renew it, it came from EMATER, and they said that it was not possible to renew”. (Interviewee ESCH05).

In this context, a discussion on peri-urban agriculture is appropriate, either within the PNAE or within a law or resolution that manages to include this type of production in public policies. Mogeout (1999) characterized the peripheral agriculture of a locality as cultivating, producing, raising, processing, and distributing a diversity of food and non-food products using human and material resources, products, and services found in or around the urban area.

This question about who participates in family farming leads to tension number 2, which influences practically all dimensions of the Family Farmers System and affects the division of labor, the rules, the community, mediational resources, and the object, in this case, economic maintenance of life in the countryside through the PNAE. The middleman emerges in this context by buying products from farmers at low cost and reselling these same products in public policies, as he presents the documentation required to enter the programs. In this case, the agent’s relationship with the mediation means can be characterized in terms of appropriation, that is, whoever owns the documents is the one who participates. To resolve this situation, a new mediation is needed to transform the mediated action, in this case, to supervise with more intensity. The accounts of the interviewees below show the point of view of the SEDUC, a farmer who feels commercially affected and a farmer who sees herself with no option, having to sell to the middleman, as she was unable to renew the DAP:

“There is something I told you that we face a very big barrier called middleman, people who falsify documents [...] there was a cooperative that worked all year with “cold documents”. This saddens us because it is part of a crime” (Interviewee ECVERDE01).

“Then, they do not want people to be middleman here, but in my case, I will have to sell my flour production. If someone shows up to buy it, it may or may not be on the program, but I will sell it; otherwise, it will ruin everything” (Interviewee ESCH05).

Law No. 11,947 brought into the dynamic process of the PNAE new relationships and actions of the social actors involved through two systems of activities. From the analysis in the municipality of Porto Velho, actions performed by the subjects were verified that generated levels of learning, which in turn reproduced behaviors that allowed the analysis of their concerns.

6 Conclusion

This study shows environmental and social aspects intermediated by a public policy. Describing good examples of PNAE implementation, it provides solid scientific evidence on the benefits of a social policy in underdeveloped regions. In a region like the Amazon, identifying solutions like this is a way to discuss the containment of deforestation and development of more sustainable ways of producing food. Publications like these enable a better comprehension of the regional aspects of Brazil.

Although there are ecological, political, economic, and social tensions, family farmers question institutions in search for meaning to their activities. It is essential, during implementation of the PNAE, that those institutions will support family farming by providing a structural adjustment policy and subsidies, instead of encouraging the concentration of food production under the control of some transnational corporations.

We sought to collect data and information that supported the objective of this article. By characterizing the dynamic process of the relationships and actions of the social actors involved through the activity systems, it was possible to detail the implementation of Law No. 11,947 of 2009. We described complementary laws, resolutions, decrees, and regulations that were used by the SEDUC and SEMED. The CHAT proved to be relevant in the characterization of the division of labor between the actors. From its theoretical precepts, it was possible to identify a greater number of participants in the system than in the exploratory phase of this study. From its theoretical precepts, it was possible to identify a greater number of participants in the system than in the exploratory phase of this study. The influence of community and the different realities to which the actors are exposed were verified. The mediational artifacts necessary to comply with the law used by the SEDUC, SEMED, and farmers were also evidenced.

The interactions and points of view converge toward a result, which is the execution of Law No. 11,947. However, reaching an agreement is not easy because some tensions among the actors occur. To characterize these contradictions, it was necessary to bring to the research the mediated action theory. Another strand of Vygotsky’s studies focuses on semiotic means of mediation, while the CHAT focuses on the activity itself. Together, both CHAT and MAT contributed to analyses of results.

Among all those situations, there is a question: can current institutions support family farming? To answer this question, it is necessary to understand the definition of “family farming.” Lowder et al. (2014), p. 7) point out that there is no consensus on this definition. In general, most definitions require that property be wholly or partially owned or operated by an individual and his or her relatives. For example, the official Brazilian definition is very different from that used by the United States. In Brazil, family farming focuses on less affluent farms, while the United States definition includes farms of all sizes, from farms with low-income levels to farms that are multimillion-dollar enterprises (Lowder et al., 2014, p. 5).

A Brazilian property classified as family farming must have less than four fiscal modules (a module can have between 5 and 110 ha depending on the location), the owner manages it with his family; the workforce must depend mainly on the family rather than on hired labor; and most of the family income must be from agricultural production (Lowder, et al., 2014, p. 6). In 2017, Brazilian agricultural census showed that 77% of rural properties are family-owned, representing 80.9% of the whole planted area. However, in relation to the value of agricultural production in the country, they represent 23% (IBGE, 2017b). Due to these numbers, it is fundamental to understand the term “family farming” in Brazil so that direct programs such as the PNAE can help farmers. Although it represents a little more than 20% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 67% of all people working in the agricultural sector (10.1 million people) are family farmers (IBGE, 2017b). In the state of Rondônia, approximately 37.5% of farms are family-owned, which emphasizes even more the importance of generating income for this population.

The guidelines of this federal public policy (Law No. 11,947 and its complementary resolutions) allow, in addition to the psychosocial evolution of students, preparing them for a better future, an opportunity for the productive, economic, and social organization of family farmers. The supply of food to students involves a market dispute: industrialized products or junk foods versus healthy products. This federal law requires 30% of family farming, healthy products, many of them as fresh products. The supply can be individual or organized, in agro-industries, cooperatives, associations, and unions. In the analyzed case, more specifically, several local cooperatives were created or developed (AAPIGHU, COOPAFARO, COOPAGROVERDE, RECA, and UNICAFES). In the case of Porto Velho, for example, more than 6 million reais (more than 1 million dollars) were invested in the municipality through school feeding programs, showing how much the local economy is dependent on government incentives.

Another point observed was the importance of rural extension institutions, such as EMATER, that support family farmers in their production, good practices, and commercialization, working on the alignment with Law No º11,947 and its resolutions to their agrarian reality.

It is worth mentioning that the creation of agro-industries is related to decent work and economic growth. There are cases of cooperatives that developed agribusinesses of fruit pulp, yogurt, and bread. Until the evolution of Pescados Progresso, whose founder initially sold fresh fish and from 2016 onward sought to structure its agro-industry to meet the demand. The expansion of its business enabled it to employ people close to the rural area where the agro-industry is located. There was regional development and improvement in the quality of life, aligned with poverty reduction and promotion of local development.