94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci., 19 September 2022

Sec. Environmental Economics and Management

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.976203

This article is part of the Research TopicClimate Risk, ESG Integration and Economic GrowthView all 11 articles

This paper aims to investigate the impact, mechanism, and heterogeneity of regional integration policy (RIP) on firms’ total factor productivity (TFP). We take the integration of the Shenzhen-Dongguan-Huizhou policy (ISDHP) as the research object and conduct a multi-dimensional fixed-effect DID analysis based on China’s listed A-share firms’ data. The results show that RIP can significantly improve corporate TFP within the region, while it is more pronounced in the SOE group. After a series of robustness tests, the policy effects are summarized as robust. In addition, we use a set of industry chain indicators to identify the mechanism between RIP and corporate TFP from the industry chain perspective. We conclude that the ISDHP can improve corporate TFP by significantly improving the upstream degree of firms’ industrial chain. Further research shows that the impact of ISDHP policies can also improve corporate TFP by green innovating, innovating, and improving market competitiveness. Moreover, the state-owned listed firms have significant advantages in these mechanisms. In general, China’s ISDHP has achieved the expected effect in improving enterprises’ TFP. However, in the future, attention should be paid to the issues of “state tilt” and “private discrimination”.

Since China implemented the reform and opening-up policy in the late 1970s, the national economy has achieved a miracle of economic growth driven by capital and resource factors. However, the extensive growth mode that intensively relies on resources and factors is difficult to maintain. Resource and environmental issues have become important constraints restricting China’s economic growth, and the issue of high-quality development is imminent (Yu et al., 2020). The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China proposed: “China’s economy has shifted from a stage of high-speed growth to a stage of high-quality development, and is in a critical period of transforming its development mode, optimizing its economic structure, and transforming its growth drivers.” High-quality economic development no longer only emphasizes the speed of economic growth, but also pays more attention to the quality and efficiency of economic growth. In this context, the improvement of total factor productivity (TFP) has become the key content of high-quality economic development. How to improve corporate TFP to achieve high-quality development at the enterprise level has become an important topic of concern for scholars in recent years.

In order to solve similar problems related to the quality of economic development, China and other emerging economies have taken many measures (Ma & Zhu, 2022). Among these attempts, the regional integration policy (RIP), which is represented by targeted integration of regions, is the policy attempt that the Chinese government attaches great importance to. Previous studies have shown that the degree of integration of the economic circle determines the spatial arrangement and strategic position of a region. It directly determines the development quality and efficiency of a country or region (Chen A. Z et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). On this basis, scholars have studied the relationship between RIP and high-quality economic development. They mainly focus on the impact of regional integration on high-quality development at the macro level, for example, by studying the impact of regional integration on urban TFP (Li et al., 2017; Huang and Zhang, 2019; Zhang et al., 2021). Surprisingly, however, few studies have examined the impact of RIP on firm-level TFP at the microenterprise level. To address this gap, we use data from Chinese listed companies to examine the impact of RIP on firm TFP, taking the integration of the Shenzhen-Dongguan-Huizhou Policy (ISDHP) as an example.

In theory, the main content of the RIP is to ease the constraints on the cross-regional circulation of resource elements. It reduces the cost of transportation and trade while promoting the spatial diffusion and spillover of knowledge and technology. It realizes the efficient allocation of resource factors and reduces the cost of technological innovation for enterprises (Li et al., 2017; Gries et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). Therefore, logically, RIP may have a positive impact on corporate TFP. Many scholars have carried out theoretical and empirical analyses and provided empirical supporting evidence (Jensen & Miller, 2018; Bau and Matray, 2020; Blankespoor et al., 2022). For example, Li et al. (2022) apply the PSM-DID method to examine the impact of RIP on firm productivity and its heterogeneity based on the city data of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Their findings support this view. However, RIP does not always have a positive impact on corporate TFP as expected. Many scholars have come to the exact opposite conclusion. They believe that the process of regional integration will boost the cross-regional location choices of heterogeneous companies. It will exacerbate regional imbalances, increase the productivity gap between regions, and inhibit the productivity of enterprises in backward regions (Liang et al., 2012; Lv et al., 2019). For example, Lv et al. (2019), based on the theoretical model of the new economic geography, examines the relationship between the integration process and corporate productivity. They found that in the process of integration, low-productivity firms in developed regions migrated out first. Then the economic gap between regions is narrowing, but the productivity gap is widening. Although the above studies have drawn completely contradictory conclusions, they also confirm that RIP does have an impact on corporate TFP. To this end, it is necessary to introduce new empirical evidence to assess the causal relationship, providing new empirical extensions to the existing literature.

In addition, COVID-19 swept the world at the end of 2019, and the global outbreak of the epidemic and extreme weather conditions had a great impact on international economic trade. It has brought a series of severe challenges to the development of the industrial chain in China’s southeast coastal economic circle. The high-quality development of each economic circle has been negatively affected to varying degrees (Dou et al., 2021). This raises another question, will the level of industrial chain linkages in the economic circle be an important mechanism that affects the effect of RIP on corporate TFP? However, to the best of our knowledge, this leaves a gap in existing research on the impact of RIP on corporate TFP. In the field of international trade, many scholars have conducted many investigations on the link between the industrial chain and corporate TFP (Yan et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2021; Opazo-Basáez et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2022). For example, Ge et al. (2018) used Chinese firm-level data from 2000 to 2007 to study the impact of industrial chain participation on firm productivity. The results show that Chinese manufacturing firms experience significant productivity enhancement effects in industrial chain embedding. Cainelli et al. (2018) also provide empirical support for this conclusion. Therefore, the link between the industrial chain level and corporate TFP has been confirmed. While the relationship between RIP and the industrial chain has been generally ignored in the existing literature. Therefore, we conducted this empirical analysis to examine the impact of the ISDHP on the industrial chain to complement research in this area.

As discussed above, the relationship between RIP and corporate TFP remains uncertain in the literature. However, clarifying this relationship will help us better understand the micro-mechanisms of the high-quality development of the economic circle. It provides new insights for formulating scientific and accurate policies for the high-quality development of enterprises and RIP. To better solve the above problems, we choose the Shenzhen-Dongguan-Huizhou economic circle (SDHEC) as the research object among the many economic circles in China. We use 2007–2021 China A-share listed company data from CSMAR database and apply the DID method to investigate the impact of RIP on corporate TFP. To get a more detailed grasp, we also use the number of patents filed by listed companies and the HHI index to further investigate the other mechanisms. It found that the implementation of RIP can significantly increase the number of patents, reduce the HHI index of enterprises, and then achieve a positive impact on corporate TFP. In addition, starting from the ownership of listed companies, we use the DDD method to further investigate the heterogeneity of the policy effects of economic circle integration. We find that the policy effect of ISDHP shows a more significant TFP improvement effect in state-owned listed companies.

The marginal contributions of our research are mainly reflected in the following aspects: Firstly, this study is one of the few studies that enrich the impact of RIP on corporate TFP at the micro level. Our findings link economic circle integration policies at the macro level with high-quality enterprise development at the micro level. It provides new insights for relevant policymakers and business managers. Secondly, to our knowledge, this study is the first paper that attempts to examine the mechanism of RIP on corporate TFP from the perspective of industrial chain linkages. It provides new ideas for the RIP and industrial chain builders of emerging economies including China. It also helps to realize the high-quality development of enterprises in the region in the post-epidemic era. Thirdly, we introduce a variety of causal identification methods such as the multi-dimensional fixed-effect DID method and DDD method. These econometric methods help to scientifically estimate the policy effects, mechanisms, and heterogeneous characteristics of ISDHP in China. It also improves the scientific nature of policy treatment effect evaluation and provides ideas for such policy evaluation work.

In the following text, Section 2 discusses the policy background and literature. Section 3 explains the methodology and data. Section 4 illustrates the empirical results of the benchmark model, robustness tests, and policy heterogeneity. Section 5 is an in-depth analysis of the mechanism. The last Section brings out the conclusions and recommendations for future research.

The Pearl River Delta is an important urban agglomeration along the southeast coast of China and an important engine of China’s economic growth. Its economic and social development is deeply affected by the combined effects of globalization and localization (Liu et al., 2022). The integration process of the Pearl River Delta is as follows: firstly, the key construction of the core cities of Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Zhuhai, forming a core-edge structure; secondly, to form secondary urban agglomerations or economic circles around these three core cities, namely Guang-Fo-Zhao (Guangzhou, Foshan, Zhaoqing), Shen-Guan-Hui (Shenzhen, Dongguan, Huizhou), and Zhu-Zhong-Jiang (Zhuhai, Zhongshan, Jiangmen), forming a multi-center ring-layer structure. On 24 September 2009, the third joint meeting on the integration of Shenzhen-Dongguan-Huizhou was held in Huizhou. Following the requirements of the “Outline of the Reform and Development Plan for the Pearl River Delta Region” on “optimizing the functional layout of the east bank of the Pearl River estuary” and the Guangdong Provincial Government’s “Guiding Opinions on Accelerating the Promotion of the Regional Economic Integration of the Pearl River Delta”, Shenzhen, Dongguan, and Huizhou held three joint meetings of the main leaders of the party and government in the three cities in 2009. They signed a series of cooperation agreements, such as “Implementing the Outline of the Reform and Development Plan for the Pearl River Delta Region and Promoting Close Cooperation in the East Bank of the Pearl River Estuary”, and “Shenzhen-Dongguan-Huizhou Planning Integration Cooperation Agreement”. In 2014, Guangdong Province’s revitalization and development strategy for the east, west, and north regions of Guangdong was carried out. Heyuan and Shanwei were officially included in the SDHEC.

The SDHEC has successively established a multi-level and multi-channel cooperation structure. Under this cooperation framework, SDHEC has adopted a series of integrated reform policy measures. It mainly includes the following five aspects: industrial integration, environmental protection integration, transportation infrastructure integration, technological innovation integration, and market integration (as shown in Table 1).

At present, under the integrated reform policy measures, SDHEC has made significant progress in industrial development, environmental governance, infrastructure construction, and collaborative innovation. However, it is difficult for us to directly judge whether ISDHP has brought improvement to corporate TFP. If so, by what mechanism does ISDHP achieve its influence on corporate TFP? Is there heterogeneity in the policy effects of ISDHP? These issues need to be further identified and analyzed.

Although, as a macro-regional planning policy, RIP focuses on the macro-level multi-regional and cross-administrative boundary economic coordination policy, the micro-effects of policies have been a hot research direction of scholars in recent years. As mentioned in the introduction, the key job of RIP is to break through the barriers, which can significantly reduce the cost of acquiring advanced knowledge and technologies for some enterprises in the economic circle, thereby improving the TFP of these enterprises. Much literature supports this view. For example, Blankespoor et al. (2022) examine the integration effect such as the Jamuna Bridge construction in Bangladesh. They found that integration by the bridge construction led to economic revival in the Jamuna hinterland and increased productivity. In addition, under RIP, human capital represented by advanced managers will be efficiently circulated between regions. It can bring advanced management levels and allocation efficiency to some enterprises and improve the TFP of enterprises (Chang et al., 2016; Hou & Song, 2021). For China, Li et al. (2022) report similar conclusions. Therefore, RIP may have a positive impact on their TFP. Accordingly, we propose the first hypothesis:

H1a: The ISDHP will have a positive impact on corporate TFP within the territory.

However, RIP does not always lead to high-quality development as expected while being introduced to more and more countries and regions. Scholars have even found the exact opposite conclusion. They believe that the RIP will interfere with the spatial location choice of enterprises and hinder the free choice and productivity ranking in market competition. It interferes with the resource allocation process, resulting in rising transaction costs and restricting the improvement of corporate TFP (Chuah et al., 2018; Chen & Lin, 2021). In addition, although the RIP can reduce transaction costs, however, this positive effect is mainly reflected in the core areas. For the non-central areas, excellent enterprises, resources, and factors are attracted and absorbed by central cities and regions. At the same time, relatively inefficient enterprises are squeezed into non-central areas. This will further deteriorate the productivity improvement of the non-central areas. This argument is supported by Lv et al. (2019). Based on the theoretical model of the new economic geography, they found that in the process of integration, low-productivity firms in developed regions migrated out first. Then the economic gap between regions is narrowing, but the productivity gap is widening. On this basis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1b: The ISDHP will have a negative impact on corporate TFP within the territory.

As mentioned in the introduction, scholars have confirmed the link between the industrial chain level and corporate TFP (Amiti et al., 2014; Baldwin & Yan, 2014; Chen H et al., 2021). As for China, due to its latecomer advantages, it can easily learn and absorb advanced production processes, management systems, and advanced technologies from importing countries in international trade (Liu et al., 2017; Chen W et al., 2021). However, the relationship between RIP and the industrial chain has been generally ignored in the existing literature.

As shown in Table 1, we can reasonably believe that RIP’s industrial integration measures can reshape the industrial structure and layout of the economic circle. This makes the original homogeneous industrial competition evolve into a rational division of labor. On the one hand, industrial redistribution can stimulate the extension and expansion of the local industrial chain. This directly enhances the domestic connection of the industrial chain. The regional integration of the industrial chain will also enhance the international competitive advantage and connection of the industrial chain. On the other hand, enterprises in the economic circle can enjoy the amplification effect of the integrated local market in industrial redistribution. This will lead to an increase in competitiveness, allowing companies to climb further upstream in the global industrial chain and global value chain. Therefore, we propose the hypothesis as follows:

H2a: Industrial chain linkage is an important mechanism for ISDHP to improve corporate TFP. ISDHP can significantly improve the upstream of the industrial chain of local enterprises and drive the growth of corporate TFP.

However, some scholars have found that the international linkage of the industrial chain may not always improve corporate productivity. For example, Daveri & Jona-Lasinio (2008) did not find the productivity improvement effect brought by international production segmentation in their research. Lin & Ma (2012) suggested that during their sample period Korea’s experiment with service outsourcing did not lead to an increase in its productivity. This mismatch in the global industrial chain will somehow affect its positive impact on corporate TFP. On this basis, we propose the opposite hypothesis:

H2b: The industrial chain connection has no significant mechanism role in the influence of the ISDHP on corporate TFP.

Previous studies have shown that environmental policy has a significant impact on corporate green innovation (Hazarika & Zhang, 2019; Takalo & Tooranloo, 2021). As shown in Table 1, ISDHP has taken many environmental protection integration measures. These measures are indeed the environmental policy. Therefore, logically, RIP can convey green management signals to company management by exerting environmental pressure on enterprises. It will prompt company management to take green behavioral decisions in response to policy pressures from the integrated system of environmental protection (Wang et al., 2020; Liu et al. al., 2021). Thus, RIP can promote corporate green innovation. The improvement of corporate green innovation will inevitably lead to the improvement of corporate TFP. Therefore, we propose the green innovation mechanism hypothesis:

H3: Green innovation plays a significant mechanism role in the influence of the ISDHP on corporate TFP.

Theoretically, innovation integration can significantly improve the allocation efficiency of knowledge, technology, and human resources in the spatial dimension. It can significantly reduce the cost of acquiring advanced resources for enterprises. This helps to improve the probability of enterprises achieving technological innovation and independent innovation, thereby improving TFP (Davids & Frenken, 2018; Kijek & Matras-Bolibok, 2019). Based on that, we propose the innovation mechanism hypothesis:

H4: ISDHP has significantly improved the local corporate TFP by enhancing the innovation capabilities and the green innovation level of the companies in the circle.

As shown in Table 1, the market integration policy measures in RIP aim to form a unified market within the economic circle. That is, to build a relatively unified and perfect market environment and form a market atmosphere with complete competitiveness. Therefore, we believe that the advancement of the market integration process in the integration of economic circles will help improve the degree of market competition, improve market efficiency, accelerates the replacement and elimination of outdated production capacity and technology, and improves the TFP of enterprises in the circle (Abdoh, 2019; Liu and Li, 2021). In conclusion, we propose the market competition mechanism hypothesis:

H5: ISDHP significantly improves corporate TFP by raising the level of market competition in the economic circle.

The DID method is widely used in the existing literature when assessing the impact of a government’s economic and social policy (Card and Krueger, 1994; Goodman-Bacon,2021). Accordingly, we mainly use the multi-dimensional fixed-effects DID model to examine the impact of ISDHP on micro corporate TFP as follows:

In the above model, i represents the listed company, j represents the province, and t represents the year.

1) Dependent Variable. The existing methods for measuring the TFP of listed companies mainly include the parametric method, non-parametric method, and semi-parametric method. Among them, semi-parametric estimation has become the main method for estimating micro corporate TFP because it can avoid simultaneous bias and selection bias (Liu et al., 2017). Commonly used semiparametric methods are the OP method (Olley & Pakes, 1996) and the LP method (Levinsohn & Petrin, 2003). However, due to the high requirements of OP for raw data, scholars gradually turned to the LP method, which takes into account the problem of endogeneity and missing data, to estimate the TFP of listed companies (Lu & Lian, 2012). Therefore, this paper mainly refers to the practice of Zhang & Shen (2020), Giannetti, et al. (2015), Yang (2015), and other scholars. We first use the LP method to calculate the TFP of Chinese listed companies for benchmark model estimation. Secondly, we adopt the OP method and other methods to measure the TFP of various listed companies (tfp_op, tfp_xie, tfp_liao) for robustness testing. The input-output variables required for the calculation are as follows: Operating income (total output), net fixed assets (capital input), number of employees (labor input), intermediate inputs (operating cost plus selling expenses plus administrative expenses plus financial expenses minus depreciation and amortization minus paid to and for employees cash).

2) Key Explanatory Variable. The key explanatory variable in the benchmark model 1) is the multiplication term of the time dummy variable and the treatment group dummy variable

3) Key Mechanism Variables. ①Industry chain mechanism variables. We choose the number of production stages in the industrial chain and the industrial chain position index to measure the level of the regional industrial chain. Accordingly, we examine how ISDHP affects the regional industrial chain and then act on corporate TFP. Based on the research of Wang (2017a, 2017b), we use the production chain forward link production length Plv to measure the number of production stages in the industrial chain. The larger the value Plv, the farther the sector is from the final consumer end, and the more upstream the sector is in the value chain of the industrial chain. Then we use the production chain backward link production length Ply to examine the upstream and downstream levels of the industry. The larger the value Ply, the closer the sector is to the final consumer, and the more downstream the sector is in the value chain of the industrial chain. Besides, we use the ratio of forward link production length to backward link production length POS and the APL-based production position index POS_ APL to measure the industrial chain position index (Wang, 2017a; Zhao). When the Position value is high, it means that this sector is relatively further from the final consumption end.

② Green Innovation mechanism variables. Based on the research of Li and Zheng (2016), Wang et al. (2021), etc., we use the number of green patent applications of listed companies to measure the level of corporate green innovation

③ Innovation mechanism variables. Based on the research of Im & Shon (2019), and Chen (2021), we use the number of patent applications filed by listed companies to measure the level of corporate innovation. Specifically, the number of patent applications of listed companies is obtained by adding up the number of invention patents and utility model patents of listed companies. In addition, we take the number of invention patents authorized by listed companies as a robust test in the follow-up study. To eliminate the obvious right-skewed distribution problem of the patent data of listed companies, we take the natural logarithm of the number of patents plus one to obtain

④ Market competition mechanism. Based on the research of Yu et al. (2016) and other scholars, we use HHI (Wang & Zhou, 2017) and Lener Index (Zhang & Zhao, 2022) to measure the level of competitiveness of listed companies in the market. The values of HHI and LI reflect the level of monopoly power in the market in which the company is located. Therefore, the larger the value, the stronger the market monopoly power of the industry and the lower the degree of market competition.

4)Control Variables. To control the potential confounding factors that may affect the total factor productivity of enterprises and obtain more reliable estimation results of policy effects, based on the research of Chen W et al. (2021), Zhang and Liu (2022), and other scholars, the following enterprise-level variables are controlled: ① Enterprise size (Size); ② Asset-liability ratio (Lev); ③ Return on assets (ROA); ④ Enterprise TobinQ (TobinQ); ⑤ Enterprise age (Age). In addition, we also control for the fixed effect of the province, the individual company, and the year. It removes unobservable confounding factors at the regional and enterprise levels that do not change with time and time factors that do not change with individuals, to improve the credibility of policy effect estimates.

The data used in this paper mainly come from three sources: listed company data, industry chain data, and patent data. In this study, the LP method is used to measure the explained variable corporate TFP, which requires input and output variables. These IO variables and the main control variables are all from the CSMRA listed company finance and characteristics database. We manually collect data on variables related to A-share listed companies. Financial insurance and abnormal trading listed companies (ST and PT listed companies) are excluded, and samples of companies with serious missing variables are also removed. The data for calculating the industrial chain comes from the ADB-MRIO in the UIBE GVC Indicators database RIGVC UIBE 2016. The ADB-MRIO (2021) database contains data from 63 countries and regions and 35 industrial sectors in 15 years from 2000 to 2007–2020. Based on the data of ADB-MRIO (2021) and the method of Wang (2017a, 2017b), this paper calculates the industrial chain length and industrial chain position data of various industries. To make full use of ADB-MRIO (2021), this paper selects the samples from 2007 to 2020 to match and merge with the data of listed companies to obtain the industrial chain data of listed companies.

In addition, to verify the innovation mechanism of ISDHP, the patent data of listed companies is also required. The patent data of listed companies including patent application data and patent authorization data comes from the China Research Data Service Platform (CNRDS). Then, we obtain the green patent data by matching the patent identification in the CNRDS with the “Green List of International Patent Classification” issued by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Then, the characteristic data, the industrial chain data, and the patent data are matched and merged to obtain the final dataset. To eliminate the influence of extreme values, this paper performs a 1% Winsorize treatment on the main variables.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the main variables. tfp_lp has a mean of 9.04, a standard deviation of 1.107, a minimum value of 6.33, and a maximum value of 12.27, and it shows that the TFP measured by the LP method is quite different among the sample listed companies. Similarly, the statistics of Plv, Ply and APT also show that the length of the regional industrial chain and the level of innovation among listed companies are quite different.

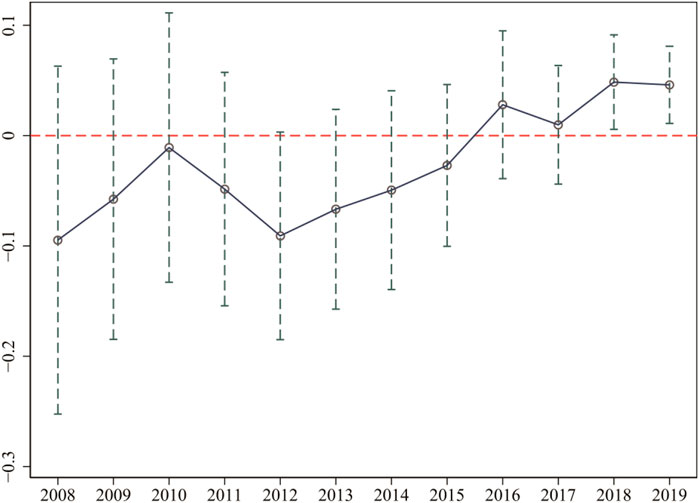

The important premise of using the DID model is that the policy treatment group and the control group have a significant parallel trend before the policy (Huang and Chen, 2022a; Wang et al., 2021). That is, before the implementation of the integration policy, the TFP levels of listed companies in Shenzhen-Dongguan-Huizhou and non-Shenzhen-Dongguan-Huizhou should have a significantly parallel time series trend. Based on the literature (Deschenes et al., 2017; Liu & Xiao, 2022), we use the event study method for reference to carry out the parallel trend test, and the model is as follows:

In model (2),

FIGURE 1. Parallel trend test (PS: The figure is drawn according to the value and the confidence interval of the coefficient

As shown in Table 3, columns (1)–4) are the results of the average treatment effect estimated by the DID model with or without the control variable and fixed effect. Column 4) is the estimation result of the benchmark model (1). By comparison, we can examine the difference in estimated results with or without control variables and with or without fixed effects. The results show that after controlling for firm-level control variables and fixed effects, ISDHP has a significant promoting effect on the TFP of listed companies. The estimated coefficient is significant at the 1% confidence level. The above benchmark regression results for the first time confirm the significant improvement effect of Chinese ISDHP on corporate TFP, which is consistent with the theoretical hypothesis H1a.

In addition, column 5) in Table 3 is the estimation result of selecting the listed companies in Guangdong Province to identify the benchmark model. When the sample is limited to Guangdong Province, the baseline estimation results are still significant at the 1% confidence level, again supporting the theoretical hypothesis H1a.

To understand the time series characteristics of policy effects more clearly, we added dynamic policy effect analysis to the benchmark regression.

As shown in Table 4, column 1) is the dynamic policy effect analysis results of the full sample. After the policy is implemented, RIP has a positive impact on corporate TFP and the policy effect varies over time. However, from 2011 to 2013, the policy effect is not significant, and after that turns to positive and significant. In addition, we add the dynamic policy effect analysis of the Guangdong Province sample for the robust test as shown in column (2). It found that the policy effect still varies over time and the policy effect disappears in 2011–2013 and 2018–2019.

The previous article has analyzed the average policy effect of ISDHP on corporate TFP and lacks a sufficient comparison before and after the policy is introduced. Therefore, referring to the research method of Shi and Li (2020), the difference in corporate TFP in different periods was tested by changing the time window width before and after the introduction of ISDHP. Specifically, 2 and 3 years are selected as the window width for the dynamic sliding window test.

The test results are shown in Table 5. Changing the width of the time window does not change the direction of the impact of ISDHP on corporate TFP. It indicates that the estimation results of the benchmark model are robust, again supporting the theoretical hypothesis H1a.

To make the benchmark regression results credible, this paper advances the ISDHP time by 1 year (Pre1) and 2 years (Pre2) and conducts a counterfactual test on the average treatment effect of RIP on SDHEC’s corporate TFP.

The results are shown in Table 6 below. When we advance the ISDHP time by 1 year and 2 years, the effect of RIP on corporate TFP is not statistically significant. It stated that when ISDHP was not implemented, RIP did not have any significant impact on SDHMC’s corporate TFP. Therefore, the baseline model regression results are robust, which again supports the theoretical hypothesis H1a.

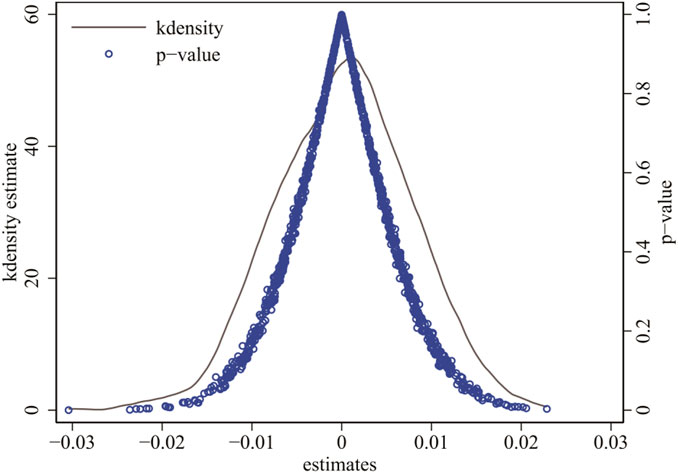

Although DID estimates can mitigate potential unobservable confounders to some extent, self-selection bias may still exist in the treatment groups. Therefore, referring to the research of Huang and Chen (2022b), and Wang et al. (2021), we further avoid this bias by conducting multiple random sampling experiments. Specifically, we randomly sample 1,000 times to obtain a virtual experimental group and a control group and apply the benchmark estimation model to identify policy effects. The results of the placebo test were examined by plotting the kernel density curve and the distribution of policy effect coefficients as shown in Figure 2. It shows the distribution of DID term coefficients in the random sampling estimation results. It can be found that most of the sampling estimation coefficients still have a low pass rate at the 10% confidence level, that is, the significance of the placebo sampling results fails. It indicates that the policy effect of the ISDHP does not exist significantly in the random sampling simulation, that is, the baseline estimate results pass the placebo test.

FIGURE 2. Placebo test. (PS: Figure is the plot of kernel density and p-value distribution of coefficients estimated with random sample 1,000 times based on the benchmark estimation.)

Based on the practice of Zhang & Shen (2020), and Yang (2015), we change the dependent variable for robustness testing, and re-identified and estimated the benchmark model (1). This processing method can exclude the influence of unobservable confounding factors that may be ignored by the LP method.

The estimation results are shown in Table 7. Columns (1), (3), and 5) are the analysis results of different dependent variables using the benchmark model 1) to estimate policy effects. It finds that the estimated results of the three groups of dependent variables are all significantly positive at the 1% confidence level. It shows that the promotion effect of ISDHP on corporate TFP is still significant under various measurement methods. The benchmark estimation results are robust, and hypothesis H1a is verified again.

In addition, we also estimate the sample from Guangdong Province alone. Columns (2), (4), and 6) are the analysis results of different dependent variables. The estimated results are significant when the sample is limited to Guangdong Province. It supports the theoretical hypothesis H1a again.

We construct policy dummy variables for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area and incorporate them into the benchmark model to control for confounding effects. The estimated results are shown in Table 8.

Columns 1) to 4) in Table 8 are the estimated results of different dependent variables. The results are all significantly positive at the 1% level. It shows that after controlling the confounding effects of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, the ISDHP still has a positive effect on corporate TFP. It verifies hypothesis H1a again and verifies the robustness of the benchmark estimation results.

Ownership is an important factor affecting the innovation and development of firms in China (Huang & Chen, 2022b). State-owned enterprises and private enterprises may enjoy different “treatment” in the face of government policies. Therefore, we performed estimation analyses of all fabrications as significant sources of heterogeneity. Drawing on the practice of Jiang (2022), we apply a DDD estimation model to investigate ownership heterogeneity. This model can not only directly show the difference in the policy effect coefficient, but also can be achieved by testing HSOE:

The estimated results are shown in Table 9. Columns (1)–4) are the estimated results of ISDHP policy effects on enterprises of different ownerships, respectively, with different dependent variables. The results show that the policy effect coefficients of state-owned listed companies are all larger than those of private listed companies. The three HSOE:

To test whether ISDHP exerts its policy effect by affecting the linkage of the industrial chain, we use Plv and Ply to test the mechanism:

The estimated results are shown in Table 10. Columns 1) and 3) are the estimated results. The results in column 1) show that ISDHP helps to improve the production length of the forward linkage of the industrial chain. The estimated coefficient is significant at the 1% level, indicating that ISDHP significantly improves the upstream degree of local enterprises in the global industrial chain. The results in column 3) show that ISDHP helps to shorten the production length of backward linkages in the industrial chain. The estimated coefficient is significant at the 1% level, indicating that ISDHP significantly reduces the downstream degree of territorial enterprises in the global industrial chain. On the one hand, it proves that the industrial chain climbing effect is an important mechanism for ISDHP on corporate TFP. That is, hypothesis H2a is proved. On the other hand, the results show that under the ISDHP, industrial integration has gradually advanced. It will help the SDHEC to absorb the technology diffusion of developed countries through import and export trade. This gradually improves the upstream level of local enterprises participating in the global industrial chain and leads to independent innovation. The dependence on the import of intermediate goods from developed economies is gradually reduced, the domestic industrial chain is continuously strengthened, and the downstream degree is significantly reduced.

Secondly, columns 2) and 4) are the estimation results of the DDD estimation model. We found that the estimated coefficients of DID*SOE and DID*(1-SOE) were both significant at the 1% level. The HSOE test showed that there was a significant difference between the two coefficients. It means that ISDHP can better promote the upstream status of state-owned listed companies in the global industrial chain. It can also shorten the downstream status of local state-owned listed companies in the global industrial chain. The possible explanation is that under ISDHP, state-owned listed companies have more policy support than private listed companies. It enables state-owned listed companies to have certain policy advantages over private enterprises in the process of import and export trade. Thus, the process of absorbing advanced technologies is earlier, wider, or even faster. Then, state-owned entities can perform better in the global industrial chain and value chain.

In addition, based on the research of Wang (2017b), we also decompose Plv into forward link pure domestic production length Plv_d and international production length Plv_o. We use these two decomposition quantities to estimate the ISDHP policy. The estimation model is as follows:

The estimated results are shown in Table 11. Columns 1) and 3) are the estimated results of different dependent variables. The estimated coefficients are significant at the level of 1 and 5%, respectively. This indicates that ISDHP has significantly improved the pure domestic production length Plv_d and the international production length Plv_o of the forward linkage of local enterprises. It means that whether the domestic connection or the international connection, ISDHP has shown a significant positive promotion effect, which verifies hypothesis H2a again.

Columns 2) and 4) are the results of the ownership heterogeneity estimation. The results show that the domestic linkages are mainly driven by private listed companies, while the international linkages are mainly driven by state-owned listed companies. The estimated coefficients are significant at the levels of 1 and 5%, respectively. Private enterprises are relatively small in scale compared to state-owned enterprises, and their competitiveness in participating in international trade is weaker. Therefore, private enterprises are more inclined to distribute production activities in the domestic production network. While state-owned enterprises will choose to embed some production activities in the international production division network in international trade.

In addition, we also use the position index to further examine how ISDHP affects the position of the industry chain to the promotion of corporate TFP. We use POS and POS_APL to measure the industrial chain position index. Then, we construct the following model to continue testing the mechanism:

Theoretically, the larger the POS and POS_APL values, the stronger the international competitiveness of the company. The estimation results are shown in Table 12. Columns 1) and 3) are the estimation results of POS and POS_APL identified by applying the above model as dependent variables, respectively. The study found that ISDHP helps to promote local enterprises to climb to a higher upstream position in the process of participating in the international industrial chain. The estimated coefficients are all significant at the 1% level. On the one hand, it again demonstrates that the industrial chain climbing effect is an important mechanism for ISDHP to improve corporate TFP. That is, hypothesis H2a has been verified again. On the other hand, the results show that ISDHP helps to obtain advanced technology diffusion from developed countries. It thereby improves corporate TFP and promotes enterprises to climb to the upstream position in the competition of the global industrial chain.

Secondly, columns 2) and 4) are the estimation results of the DDD estimation. The estimated coefficients of DID*SOE and DID*(1-SOE) were both significant at the 1% level. The HSOE test showed that there was a significant difference between the two coefficients. It shows that ISDHP can better promote the state-owned listed companies to climb the upstream position of the global industrial chain. The possible explanation is still that ISDHP is more conducive to the state-owned listed companies to climb the global industrial chain. Compared with state-owned companies, private listed companies have relatively weaker policy advantages and resource support. Thus, they are weaker than state-owned listed companies in participating in international competition. Therefore, the policy promotion effect is not as good as that of state-owned units, but the policy promotion effect still exists and is significant.

We use GAP, which is the logarithm of the number of green patent applications of listed companies plus 1, to measure the level of corporate green innovation. In addition, we also use the ratio of the number of green patent applications of listed companies to the number of patents applied for in the year, GAPR, as a proxy variable for green innovation to conduct robustness tests.

The estimation results are shown in Table 13. Columns 1) and 3) are the estimation results when GAP and GAPR are the dependent variables, respectively. The results show that, after controlling for multidimensional fixed effects, RIP has a positive effect on corporate green innovation. The estimated coefficient is significant at the 1% confidence level. The above results for the first time confirm the significant promotion effect of China’s RIP on corporate green innovation from the enterprise level. It confirms the role of green innovation as an intermediary mechanism in RIP on corporate TFP, which verified hypothesis H3.

Besides, we further analyzed the ownership heterogeneity of this mechanism using the DDD method, and the results are shown in columns 2) and 4) of Table 13. The results show that the policy effect coefficients of state-owned listed companies are smaller than those of private listed companies. The HSOE test rejects the null hypothesis. This shows that the private listed companies get more green innovation promotion effects under ISDHP, and the coefficient difference is significant. The environmental protection integration policy in RIP is a mandatory regulatory policy. Compared with state-owned listed companies, private listed companies will face greater policy constraints. This drives private enterprises to have greater incentives for green decision-making, which in turn improves the level of green innovation.

Innovation synergy or innovation integration is an important part of ISDHP. We use the total number of patents applied for by listed companies in the year APT and the total number of patents granted in the year GPT to measure the level of enterprise innovation. Then, we construct the following model to verify the hypothesis H4:

The estimation results are shown in Table 14. Columns 1) and 3) are the estimation results of APT and GPT used as dependent variables to identify the above models. The study found that ISDHP helps to promote the innovation level of local enterprises, and the estimated coefficients are all significant at the 1% level. On the one hand, it proves that the innovation effect is an important mechanism for ISDHP to improve corporate TFP. That is, it is assumed that H4 is proved. On the other hand, the results show that ISDHP helps to improve the level of technological innovation of enterprises in the circle, and then enhances corporate TFP.

Columns 2) and 4) are the estimation results of the DDD estimation. The estimated coefficients of DID*SOE and DID*(1-SOE) in column 2) were both significant at the 1% level. The estimated coefficients were significantly different through the HSOE test. That is, the estimated coefficients of DID*SOE were significantly greater than that of DID*(1-SOE). It shows that ISDHP is more conducive to the state-owned listed companies in the circle. The DID*SOE of column 4) is significantly negative at the 5% level, but the estimated coefficient of DID*(1-SOE) is not significant. The HSOE test proves that the two coefficients are significantly different. It shows that the ISDHP is not conducive to increasing the number of patents granted by state-owned listed companies in the circle.

We use HHI and LI to measure the level of market competitiveness of enterprises, and then investigate the mechanism role between ISDHP and corporate TFP. To test the above mechanism, that is, the hypothesis H5, we construct the following model:

Theoretically, the lower the HHI and LI values of listed companies, the higher the actual competitiveness level. Thus, the DID coefficient should be negative. The estimation results are shown in Table 15. Columns (1) and (3) are the estimation results of HHI and LI as dependent variables. The DID estimation coefficients of the two models were both significantly negative at the 1% level. On the one hand, it demonstrates that market competitiveness is an important mechanism for ISDHP on corporate TFP. Hypothesis H5 was verified. On the other hand, it also shows that ISDHP can promote corporate TFP by improving the market competitiveness of enterprises.

In addition, columns 2) and 4) are the estimation results of the DDD estimation. The estimated coefficient of DID*(1-SOE) of column 2) is significantly negative at the 1% level. The estimated coefficients of DID*SOE and DID*(1-SOE) in column 4) are both significantly negative at the 1% level. The estimated coefficients of the two models DID*SOE and DID*(1-SOE) are significantly different through the HSOE test. That is, the estimated coefficient of DID*SOE is significantly larger than that of DID*(1-SOE). It shows that ISDHP is more conducive to the state-owned enterprises to gain more market competitiveness. It is also in line with China’s actual national conditions.

Based on the quasi-natural experiment of ISDHP in China, this research is the first paper to examine the impact of RIP on corporate TFP from the perspective of the industrial chain. Our research provides new perspectives and new ideas for the research on the influencing factors of corporate TFP, RIP, and industrial chain linkage in emerging economies. Based on an empirical study by applying a multi-dimensional fixed-effects DID model, we found that: Firstly, ISDHP has a positive impact on corporate TFP. Moreover, the policy effect shows a more significant TFP improvement effect in the state-owned enterprise group. It is consistent with the conclusions of the existing literature (Li et al., 2022). Secondly, the level of the industrial chain linkage is an important mechanism for RIP to improve corporate TFP. It is mainly achieved by improving the upstream degree of local enterprises embedded in the global industrial chain. However, existing research lacks to explore the micro-policy effects of regional integration from this perspective. Further research finds that the RIP can also improve the corporate TFP by enhancing the level of corporate green innovation, innovation, and market competitiveness. Corporate ownership has a significant heterogeneity moderating effect on different mechanisms. The TFP of state-owned listed companies is significantly more positively affected by policy effects than private enterprises. Overall, China’s ISDHP has achieved its goal of improving corporate TFP. The above research provides ideas for subsequent scholars to introduce micro-effect evaluation similar to RIP in other emerging economies.

Although from the perspective of the industrial chain, this paper provides an econometric empirical analysis from SDHEC in China for the TFP improvement effect of ISDHP, however, it is subject to several limitations: ① Although this study investigates the policy effects of RIP on corporate TFP in SDHEC. However, due to the limitations of the sample of listed companies, it is difficult to reflect the more general effect of RIP truly and comprehensively. There will be some sample bias. ②This study attempts to explore the policy effect mechanism from the perspective of the industrial chain. However, due to the close economic ties between the cities of SDHEC, our research inevitably ignores the spatial correlation of policy effects. Future research can consider the following ideas for improvement: ① Match the Chinese industrial enterprise database data with the customs database data and try to re-examine policy effects using microdata. It can improve the confidence of the analysis and reduce possible sample bias. ② The MRIO data can be used to construct the spatial weight matrix, and then to perform spatial DID analysis on the micro data. It will identify the spatial effects of policy and increase the credibility of the research.

In conclusion, our findings support the positive impact of China’s ISDHP on industrial chain climbing, corporate innovation, market competition, and corporate TFP. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the policy design of these key mechanism factors. ①According to the requirements of industry chain supply chain segmentation, strengthen more specialized personnel training. Cultivate cross-field, cross-industry, and interdisciplinary human capital, and give play to the role of compound talents as the “glue” between the industrial chain and supply chain. Build a modern financial service system that adapts to the modernization of the industrial chain and supply chain. ②Cultivate a group of technologically advanced “little giant” enterprises with a leading role. Give full play to its main role in key technological breakthroughs and innovation. Play its leading role in creating new markets. ③ By establishing a negative list for the integration of economic circles. Clarify the boundaries of the role of the market and the government in the practice of regional integration. Build a more free market competition environment to reduce the distortion of factor allocation between regions, within and between industry chains by administrative intervention. Give full play to the decisive role of the market in the allocation of factors.

However, our research results show that the existing ISDHP has certain problems. The policy effect of RIP appears ownership discrimination, showing a significant “state-owned tilt” feature. Therefore, it is necessary to establish and improve the information disclosure and supervision system for non-listed companies based on the existing information disclosure system of listed companies in the future ISDHP practice. Besides, taking measures such as introducing NGO supervision, reducing the probability of local government ownership discrimination, and achieving a balanced development of “state-owned” and “private”.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Methodology, CG; software, CG; data curation, CG and HD; writing—original draft preparation, HD and CG; writing—review and editing, HD, CG, and HY; visualization, CG and HD; supervision, HD, CG, and HY; project administration, HD and CG; funding acquisition, HD and CG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

We acknowledge the financial support from the Shenzhen Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning 2020 Project (No. SZ 2020B012), and the Characteristic Innovation Project of General Colleges and Universities in Guangdong Province (No. 2020WTSCX237), Guangdong philosophy and Social Sciences Planning 2021 youth project (No. GD21YGL03). Sponsored by Guangdong Modern Industry and SME Development Research Center. All errors remain our own.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abdoh, H. A. (2019). Product market competition and productivity shocks. Appl. Econ. 51 (37), 4104–4115. doi:10.1080/00036846.2019.1588953

Amiti, M., Itskhoki, O., and Konings, J. (2014). Importers, exporters, and exchange rate disconnect. Am. Econ. Rev. 104 (7), 1942–1978. doi:10.1257/aer.104.7.1942

Baldwin, J. R., and Yan, B. (2014). Global value chains and the productivity of Canadian manufacturing firms[M]. (Ottawa, ON, Canada: Statistics Canada).

Bau, N., and Matray, A. (2020). Misallocation and capital market integration: Evidence from India[R]. (Cambridge, MA, United States: National Bureau of Economic Research). Working Paper(27955). doi:10.3386/w27955

Blankespoor, B., Emran, M. S., Shilpi, F., and Xu, L. (2022). Bridge to bigpush or backwash? Market integration, reallocation and productivity effects of Jamuna bridge in Bangladesh. J. Econ. Geogr. 22 (4), 853–871. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbab024

Cainelli, G., Ganau, R., and Giunta, A. (2018). Spatial agglomeration, global value chains, and productivity. Micro-Evidence from Italy and Spain. Econ. Lett. 169, 43–46. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2018.04.020

Card, D. A. D., and Krueger, A. B. (1994). Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast-food industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Am. Econ. Rev. 84 (4), 772

Chang, C., Wang, P., and Liu, J. (2016). Knowledge spillovers, human capital and productivity. J. Macroecon. 47, 214–232. doi:10.1016/j.jmacro.2015.11.003

Chen, B., and Lin, J. Y. (2021). Development strategy, resource misallocation and economic performance. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 59, 612–634. doi:10.1016/j.strueco.2021.10.003

Chen, Y. (2021). Does political turnover stifle or stimulate corporate innovation?. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 76, 1126–1145. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2021.08.010

Chen, A. Z, A. Z., Chen, F. L., and He, C. Y. (2021). Industry Chain Link. Frim’s Innovation. China Industrial Econ. 2021 (09), 80–98. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2021.09.004

Chen, H, H., Guo, W., Feng, X., Wei, W., Liu, H., Feng, Y., et al. (2021). The impact of low-carbon city pilot policy on the total factor productivity of listed enterprises in China. Resour. Conservation Recycl. 169, 105457. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105457

Chen, W, W., Sun, W., Liu, C., and Liu, W. (2021). Regional integration and high-quality development in the Yangtze River delta region[J]. Econ. Geogr. 41 (10), 127–134. doi:10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2021.10.014

Chuah, L. L., Loayza, N., and Nguyen, H. (2018). Resource misallocation and productivity gaps in Malaysia[J]. Washington, DC: World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-8368

Daveri, F., and Jona-Lasinio, C. (2008). Off-shoring and productivity growth in the Italian manufacturing industries. CESifo Econ. Stud. 54 (3), 414–450. doi:10.1093/cesifo/ifn019

Davids, M., and Frenken, K. (2018). Proximity, knowledge base and the innovation process: Towards an integrated framework. Reg. Stud. 52 (1), 23–34. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1287349

Deschenes, O., Greenstone, M., and Shapiro, J. S. (2017). Defensive investments and the demand for air quality: Evidence from the NOx budget program. Am. Econ. Rev. 107 (10), 2958–2989. doi:10.1257/aer.20131002

Ge, J., Fu, Y., Xie, R., Liu, Y., and Mo, W. (2018). The effect of GVC embeddedness on productivity improvement: From the perspective of R&D and government subsidy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 135, 22–31. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.057

Giannetti, M., Liao, G., and Yu, X. (2015). The brain gain of corporate boards: Evidence from China. J. Finance 70 (4), 1629–1682. doi:10.1111/jofi.12198

Goodman-Bacon, A. (2021). Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. J. Econ. 225 (2), 254–277. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2021.03.014

Gries, T., Grundmann, R., Palnau, I., and Redlin, M. (2018). Technology diffusion, international integration and participation in developing economies - a review of major concepts and findings. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 15 (1), 215–253. doi:10.1007/s10368-017-0373-7

Hazarika, N., and Zhang, X. (2019). Evolving theories of eco-innovation: A systematic review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 19, 64–78. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2019.03.002

Hou, S., and Song, L. (2021). Market integration and regional green total factor productivity: Evidence from China’s province-level data. Sustainability 13 (2), 472. doi:10.3390/su13020472

Hu, D., Jiao, J., Tang, Y., Han, X., and Sun, H. (2021). The effect of global value chain position on green technology innovation efficiency: From the perspective of environmental regulation. Ecol. Indic. 121, 107195. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107195

Hu, D., Jiao, J., Tang, Y., Xu, Y., and Zha, J. (2022). How global value chain participation affects green technology innovation processes: A moderated mediation model. Technol. Soc. 68, 101916. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101916

Hu, Y., Fisher-Vanden, K., and Su, B. (2020). Technological spillover through industrial and regional linkages: Firm-level evidence from China. Econ. Model. 89, 523–545. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2019.11.018

Huang, D., and Chen, G. (2022a). Can the carbon emissions trading system improve the green total factor productivity of the pilot cities?a spatial difference-in-difference econometric analysis in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (3), 1209. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031209

Huang, D., and Chen, G. (2022b). Can the technologically advanced policy achieve green innovation of small and medium-sized enterprises?the case of China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 964857. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.964857

Huang, W., and Zhang, Y. (2019). Does the strategy of regional integration affect the high-quality development of China’s urban economy? An empirical study based on urban agglomeration in the Yangtze River economic belt. Industrial Econ. Res. (06), 14–26. doi:10.13269/j.cnki.ier.2019.06.002

Im, H. J., and Shon, J. (2019). The effect of technological imitation on corporate innovation: Evidence from US patent data. Res. Policy 48 (9), 103802. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2019.05.011

Jensen, R., and Miller, N. H. (2018). Market integration, demand, and the growth of firms: Evidence from a natural experiment in India. Am. Econ. Rev. 108 (12), 3583–3625. doi:10.1257/aer.20161965

Jiang, T. (2022). Mediating effects and moderating effects in causal inference. China Ind. Econ. 2022 (5), 100–120. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2022.05.005

Kijek, T., and Matras-Bolibok, A. (2019). The relationship between TFP and innovation performance: Evidence from EU regions[J]. Equilibrium. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 14 (4), 695. doi:10.24136/eq.2019.032

Levinsohn, J., and Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Rev. Econ. Stud. 70, 317–341. doi:10.1111/1467-937x.00246

Li, X., Zhang, Y., and Sun, B. W. (2017). Does regional integration promote the efficiency of economic growth? an empirical analysis of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 27 (1), 10–19.

Li, Y., Wei, Z., and Wu, K. (2022). Does regional integration optimize firm productivity? evidence from the Yangtze River economic belt. Wuhan. Finance (02), 70

Liang, Q., Li, X., and Lv, D. (2012). Market integration, firm heterogeneity and regional investment subsidy a new perspective explaining the regional inequality in China. China Ind. Econ. (02), 16–25. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2012.02.002

Lin, S., and Ma, A. C. (2012). Outsourcing and productivity: Evidence from Korean data. J. Asian Econ. 23 (1), 39–49. doi:10.1016/j.asieco.2011.11.005

Liu, J., and Xiao, Y. Y. (2022). China's environmental protection tax and green innovation: Incentive effect or crowding-out effect?. Econ. Res. J. 57 (01), 72

Liu, P., and Li, H. (2021). The impact of banking competition on firm total factor productivity. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 1–21. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2021.2010109

Liu, W. G., Ni, H. F., and Xia, J. C. (2017). The effects of production fragmentation on enterprises’ productivity. J. World Econ. 40 (08), 29.

Liu, Y., Wang, A., and Wu, Y. (2021). Environmental regulation and green innovation: Evidence from China’s new environmental protection law. J. Clean. Prod. 297, 126698. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126698

Liu, Y., Zhang, Y. F., Huang, K. X., and Chen, R. (2022). Measuring impact of strategic coupling towards the patterns of industrial upgrading in the Pearl River Delta. Geogr. Res. 41 (4), 1107

Lu, X. D., and Lian, Y. J. (2012). Estimation of total factor productivity of industrial enterprises in China:1999一2007. China Econ. Q. 11 (02), 541–558.

Lv, D., Gen, Q., Jian, Z., et al. (2019). Market Size,Labor cost and location of heterogeneous firms:solving the riddle of economic and productivity gaps in China. Econ. Res. J. 54 (02), 36

Ma, D., and Zhu, Q. (2022). Innovation in emerging economies: Research on the digital economy driving high-quality green development. J. Bus. Res. 145, 801–813. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.03.041

Olley, G. S., and Pakes, A. (1996). The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica 64 (6), 1263–1297. doi:10.2307/2171831

Opazo-Basáez, M., Vendrell-Herrero, F., Bustinza, O. F., et al. (2021). Global value chain breadth and firm productivity: The enhancing effect of industry 4.0. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 33 (4), 785–804. doi:10.1108/JMTM-12-2020-0498

RIGVC UIBE (2016). UIBE GVC indicators. Available at: http://rigvc.uibe.edu.cn/english/D_E/database_database/index.htm.

Takalo, S. K., and Tooranloo, H. S. (2021). Green innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 279, 122474.

Wang, F., Feng, L., Li, J., and Wang, L. (2020). Environmental regulation, tenure length of officials, and green innovation of enterprises. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (7), 2284. doi:10.3390/ijerph17072284

Wang, G. D., and Zhou, J. K. (2017). Calculation on the monopoly power of Chinese manufacturing enterprises: A discusson of the market boundary. Econ. Rev. (04), 30–44. doi:10.19361/j.er.2017.04.03

Wang, S., Chen, G., and Han, X. (2021). An analysis of the impact of the emissions trading system on the green total factor productivity based on the spatial difference-in-differences approach: The case of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (17), 9040. doi:10.3390/ijerph18179040

Wang, Z., Wei, S.-J., Yu, X., and Zhu, K. (2017a). Characterizing global value chains: Production length and upstreamness”. Cambridge, MA, United States: National Bureau of Economic Research. Paper 23261. doi:10.3386/w23261

Wang, Z., Wei, S.-J., Yu, X., and Zhu, K. (2017b). Measures of participation in global value chains and global business cycles”. Cambridge, MA, United States: National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper 23222. doi:10.3386/w23222

Yan, B., Zhang, Y., Shen, Y., and Han, J. (2018). Productivity, financial constraints and outward foreign direct investment: Firm-level evidence. China Econ. Rev. 47, 47–64. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2017.12.006

Yang, R. D. (2015). Study on the total factor productivity of Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Econ. Res. J. 50 (02), 61

Yu, L., Zhang, W., Bi, Q., Dong, J., Niu, T., and Zhao, Y. (2020). Population-based design and 3D finite element analysis of transforaminal thoracic interbody fusion cages.:Evidence from the Turnover of Local Environmental Protection Directors. J. Orthop. Transl. 22 (2), 35–40. doi:10.1016/j.jot.2019.12.006

Yu, M. G., Fan, R., and Zhong, H. J. (2016). China's industrial policy and enterprise technological innovation. China Ind. Econ. (12), 5–22. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2016.12.002

Zhang, Q. L., and Shen, H. T. (2020). Can major government customers improve corporate total factor productivity?. J. Finance Econ. 46 (11), 34

Zhang, X. M., and Zhao, Y. (2022). Banking competition and systemic risk in the post-crisis era —based on major global listed commercial banks. Stud. Int. Finance (02), 44–54. doi:10.16475/j.cnki.1006-1029.2022.02.010

Zhang, Y., Liu, L., and Huang, S. (2021). Does regional integration promote the high quality development of urban agglomeration economy: A quasi——natural experiment based on the Yangtze River delta urban economic coordination commission. Stud. Sci. Sci. 39 (01), 63–72. doi:10.16192/j.cnki.1003-2053.20200930.001

Keywords: regional integration policy (RIP), integration of shenzhen-dongguan-huizhou policy (ISDHP), total factor productivity (TFP), industrial chain, difference-in-differences (DID), green innovation, market competition, listed firms

Citation: Huang D, Chen G and Han Y (2022) Regional integration policy, industrial chain and corporate total factor productivity: An econometric empirical analysis from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:976203. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.976203

Received: 23 June 2022; Accepted: 31 August 2022;

Published: 19 September 2022.

Edited by:

Martin Thomas Falk, University of South-Eastern Norway (USN), NorwayReviewed by:

Wenxiu Wang, Guangzhou Institute of Energy Conversion (CAS), ChinaCopyright © 2022 Huang, Chen and Han. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gang Chen, MTNiOTU2MDA1QHN0dS5oaXQuZWR1LmNu

†These authors contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.