- Prevention Research Center at UMass Chan Medical School, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, Worcester, MA, United States

Active transportation by walking or biking can improve health and quality of life. Public health official participation in transportation and land use policy-related decision-making is recommended to improve opportunities for active transportation. However, United States local health department (LHD) engagement in activities that support this decision-making is not well understood. The purpose of this study was to describe engagement in activities that support inclusion of active transportation in transportation and land use decision-making among small and midsize LHDs, identify LHD characteristics associated with engagement, and describe interest in training activities to increase engagement. Data are from a 2017 national probability cross-sectional survey of United States LHDs serving fewer than 500,000 residents that assessed departmental engagement in eleven activities related to ten cross-cutting capabilities that support engagement in transportation and land use decision-making (30.2% response rate). Negative binomial regression of 183 LHDs with complete data determined the relationship between LHD characteristics and engagement in activities. Survey weights were applied to generate nationally representative statistics. LHDs reported their engagement in eleven activities that support active transportation in land use and transportation decision-making as a major responsibility, secondary responsibility, or neither. Responses were summed to generate a score. LHDs reporting major responsibility varied by activity and ranged from 8.6% for data and assessment to 32.7% for public outreach to community. The distribution of engagement scores was skewed (mean = 6.2, variance = 34.7). Larger population size served, any staff working on active transportation issues, and contracting with an individual/organization on active transportation were significantly associated with greater engagement in activities related to land use and transportation decision-making that support active transportation. High interest in training or technical assistance for activities ranged from 12.2% for dedicated staffing to 42.8% for public outreach to community. These data demonstrate room for improvement in activities and capabilities supportive of active transportation in land use and transportation decision-making and modest but promising interest in assistance for greater engagement among LHDs.

1 Introduction

Active transportation by walking or bicycling, can improve health and quality of life as a sustainable form of physical activity, provide affordable connection to everyday destinations (Maizlish et al., 2022; Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF), 2016), and contribute to climate change mitigation efforts, among other benefits (Sallis et al., 2015). Land use and transportation policies that create safe, walkable and bikeable communities are evidence-based approaches that promote active transportation (De Nazelle et al., 2011). The United States Community Preventive Services Task Force recommends “built environment strategies that combine one or more interventions to improve pedestrian or bicycle transportation systems with one or more land use and environmental design interventions to increase physical activity.” Implementing such strategies requires action from government departments such as transportation, public works and land use planning.

Local health departments (LHD) have an important role to play in promoting equitable active transportation through land use and transportation policies. The Public Health 3.0 vision of public health service delivery calls for health departments to partner across sectors to address social factors that affect health, including factors pertaining to the built environment (DeSalvo et al., 2017). For nearly 2 decades public health authorities have recommended participation of the public health sector, including LHD officials, in land use and transportation policy-related decision-making to incorporate health and equity considerations, and that participation is valued by collaborators across sectors (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Dyjack et al., 2013; Lemon et al., 2015; Goins et al., 2016; Sreedhara et al., 2017; Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2018; Physical Activity Alliance, 2022). Emphasis has been on community design that makes health a priority for chronic disease prevention. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that physical activity protects against infectious disease (Sallis et al., 2021) and that allocating public space for safe and active social distancing is valuable. In addition, rising rates of traffic violence overall and disparities in these rates experienced by different demographic groups, including older adults as well as persons of color, make it imperative for LHDs to engage (Smart Growth America, 2021). Early efforts to involve public health officials in active transportation policy decision-making have emphasized building relationships between public health, and transportation and land use disciplines (Institute of Medicine, 2011). However, there is also a need to move to collaborative work on a routine basis to achieve change in the built environment (Harris et al., 2015; Pilkington et al., 2016). Available evidence suggests limited participation by public health officials overall and especially in small and midsize communities (Lemon et al., 2015; Goins et al., 2016). For example, in 2014, most United States municipalities had a planning or zoning commission (90.9%) but few included a public health representative (6.5%) (Omura et al., 2022). Conversely, few municipalities reported an advisory committee on active transportation (16.5%), with less than a quarter of these including a public health representative (22.4%) (Omura et al., 2020). Public health participation in decision-making can help to promote the inclusion of community in those processes and place equity at the center.

Little guidance exists to prepare public health officials to participate across the continuum of multi-sector land use and transportation policy-related decision-making. Breaking down participation into discrete components can provide actionable steps for LHDs to take. Our team used a Delphi methodology to develop a set of ten core capabilities and eleven associated activities for LHDs’ engagement in decision-making for active transportation, focusing on land use and transportation (Lemon et al., 2017; Lemon et al., 2019). These capabilities are aligned with the essential services of public health (Prevention CfDCa, 2022) and are intended to guide strategic planning and workforce development efforts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Three capabilities are specific to engagement in policy development and implementation during different phases of the process: plan and policy development; project development and design review; and reviewing and commenting on plans, policies, and projects. Four capabilities emphasize roles and relationships with other officials and the public, including participating on a land use or transportation policy board or committee, educating policy makers and elected officials, collaborating with public officials, and educating and mobilizing the community around built environment initiatives. Two capabilities emphasize ensuring appropriate resources for LHDs: dedicating staff and securing funding or assisting with grant applications. One capability emphasizes LHDs leading or contributing to data and assessment activities.

Our goal is to better inform strategic guidance and workforce development efforts that support LHD participation in land use and transportation policy-related decision-making. Thus, we must first understand current engagement in activities pertaining to the ten capabilities, and preferences for training and technical assistance in these areas (Lemon et al., 2019). The objectives of this study are to (1) describe small and midsize LHD engagement in activities that support land use and transportation policy-related decision making, (2) identify LHD characteristics associated with engagement, and (3) describe interest in training and technical assistance.

2 Materials and methods

The study protocol for this web-based cross-sectional survey was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the UMass Chan Medical School.

2.1 Survey development

The survey was developed based on literature and input from a team of experts in physical activity policy. Items were tested with representatives of five local health departments and revised to improve comprehension and relevance. The survey was programmed and administered in Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Useability testing was conducted with five team members and final refinements were made. This testing indicated respondents could complete the survey in 10–15 min.

2.2 Sample and survey administration

A random sample of local health departments serving populations <500,000 was obtained using a database of LHDs maintained by the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) and was drawn for eight strata based on four United States census geographic regions (Northeast, Midwest, South, West) and two population categories (<40,000 and ≥40,000). We emailed LHD directors or equivalent officials a unique survey link between June and October 2017. Recipients were encouraged to contact study staff if they believed another individual in the department was more appropriate to complete the survey. Survey instructions further asked respondents to answer from the perspective of the LHD and not their own opinion. We followed a standardized reminder protocol. Additional details about survey administration have been previously published (Sreedhara et al., 2019).

A total of 693 LHDs were invited to participate in the survey and 209 completed it (30.2% response rate). There were no statistically significant differences between respondents and non-respondents with respect to jurisdiction, governance, Census region, or population category. Of the 209 LHDs, 26 (12.4%) were excluded from the analytic sample due to missing covariates (n = 24) or outcome data (n = 2). There was not a statistically significant difference between these two groups with respect to jurisdiction, governance, or United States census geographic region. However, a greater proportion of LHDs that were analyzed represented populations of ≥ 40,000 (55.2%) than LHDs excluded due to missing data (34.6%) (p = 0.049). The final analytic sample contained 183 LHDs, which represented 2,390 United States LHDs after weights were applied.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Covariates

LHD characteristics derived from administrative data provided by NACCHO included United States geographic region, and state where the LHD was located. To explore the governance relationship between state and local public health agencies, we classified agencies as centralized, shared, mixed or decentralized by following the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials’ State and Local Health Department Governance Classification System. This was collapsed into a dichotomous variable due to small cell sizes (centralized/shared/mixed or decentralized). LHD respondents reported additional characteristics, including population size of department service area (<25,000, 25,000–49,999, 50,000–99,999, 100,000–499,999), health department structure [municipal (city or town) department, county or city-county department or other department (regional department, state-run department, public health network, other)], and perceived level of resources compared to other LHDs in own state (fewest or moderate/most kiresources).

LHDs were asked to report on staff work related to active transportation. Content area of work on active transportation (chronic disease, injury, environmental health, other, no staff work on active transportation) was reported as dichotomous variables and used to generate a summary variable of any current work on active transportation issues versus none or not. LHD contracting with individual(s) or organization(s) to work on issues related to transportation or land use and LHD receipt of training to work on active living or active transportation issues were each assessed as dichotomous variables (no or yes).

2.3.2 LHD engagement in land use and transportation policy process activities

Eleven questions about LHD participation in activities related to each of the ten capabilities described above (including two questions pertaining to dedicated staffing) were developed. Each question asked whether there was one or more staff members or contractors at the LHD for whom the activity was a responsibility, even if it was not in their job description. LHD respondents selected one of three response options (major responsibility, secondary responsibility, not major or secondary responsibility) that best matched the department’s current engagement. The 11 questions were summed to generate a score (range 0–22). To assess the reliability of the score we conducted a polychoric factor analysis, which resulted in good internal consistency (ordinal alpha = 0.96).

2.3.3 Interest in training and/or technical assistance

LHD respondents reported departmental interest in training and/or technical assistance for each of the eleven activities. Response options included low priority, moderate priority, or high priority.

2.4 Analysis

We generated frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables were described as means and variances. An interquartile range was also calculated for the outcome variable. A negative binomial regression model was conducted because the outcome variable was over-dispersed. The regression model determined the relationship between LHD characteristics and the extent of LHD engagement in activities supporting active transportation decision-making. We identified covariates to include in the adjusted model from the literature (Goins et al., 2016; National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2016). We assessed for multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor threshold of <10. Survey weights were applied to all analyses to account for the stratified simple random sampling design, differential response rates among strata, and analysis of surveys with complete data. A detailed description of survey weight construction is published elsewhere (Sreedhara et al., 2019). We performed analyses using Stata/MP 14.2 (StataCorp College Station, TX).

3 Results

3.1 LHD characteristics

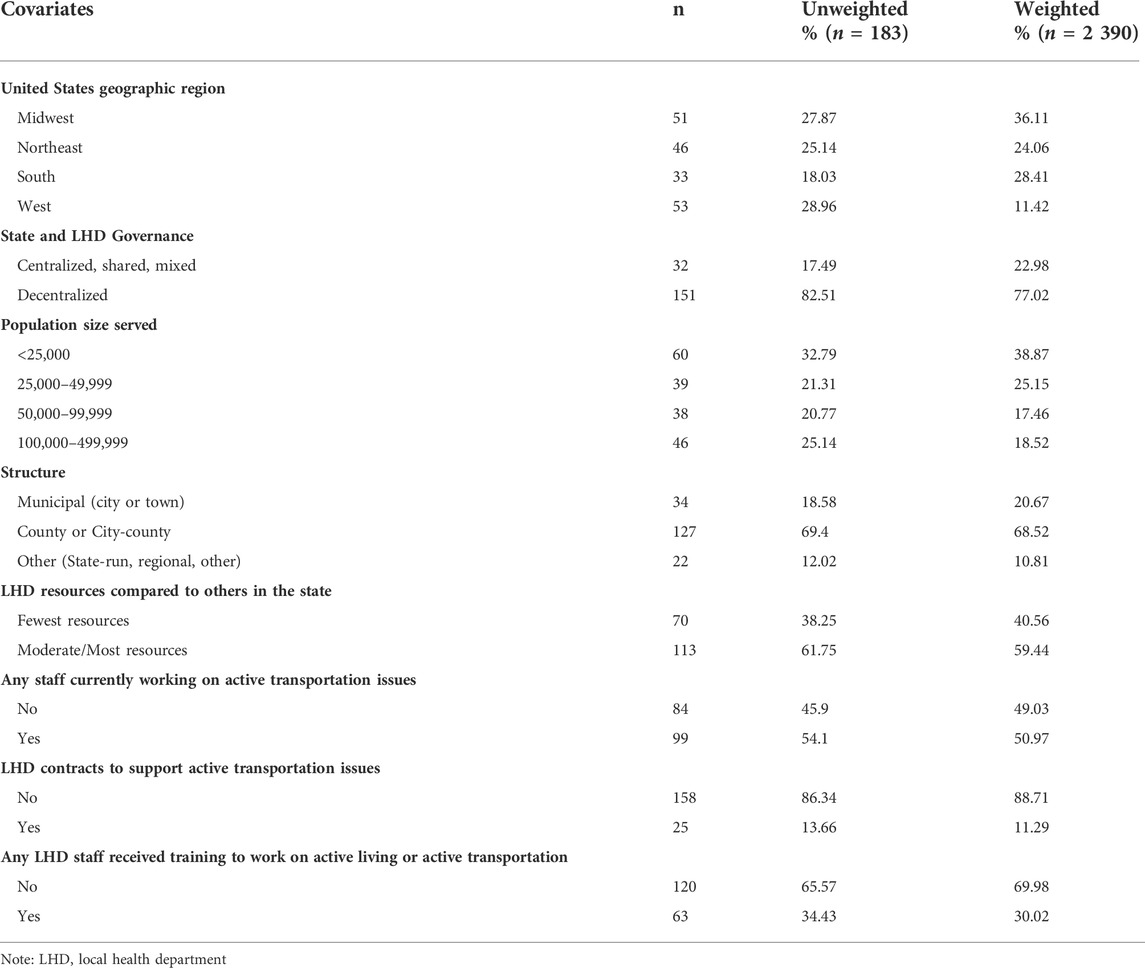

Table 1 describes the sample characteristics. Respondents were most commonly from the Midwest (36.1%), decentralized or locally governed (77.0%), were county-level departments (68.5%), and served a population of <25,000 residents (38.7%.). Half reported any current staff work on active transportation (51.0%).

3.2 Engagement in activities that pertain to capabilities supportive of active transportation

The average engagement score for LHDs was 6.2 (variance = 34.7; interquartile range = 2–10). Figure 1 describes LHDs’ current engagement activities supporting active transportation decision-making. The percentage of LHDs reporting major responsibility for individual activities ranged from 8.6% for data and assessment to 32.7% for public outreach to community.

FIGURE 1. Percentage of United States local health departments reporting level of responsibility of one or more staff member(s) or contractor(s) to perform activities, (unweighted n = 183, weighted n = 2390), weighted %.

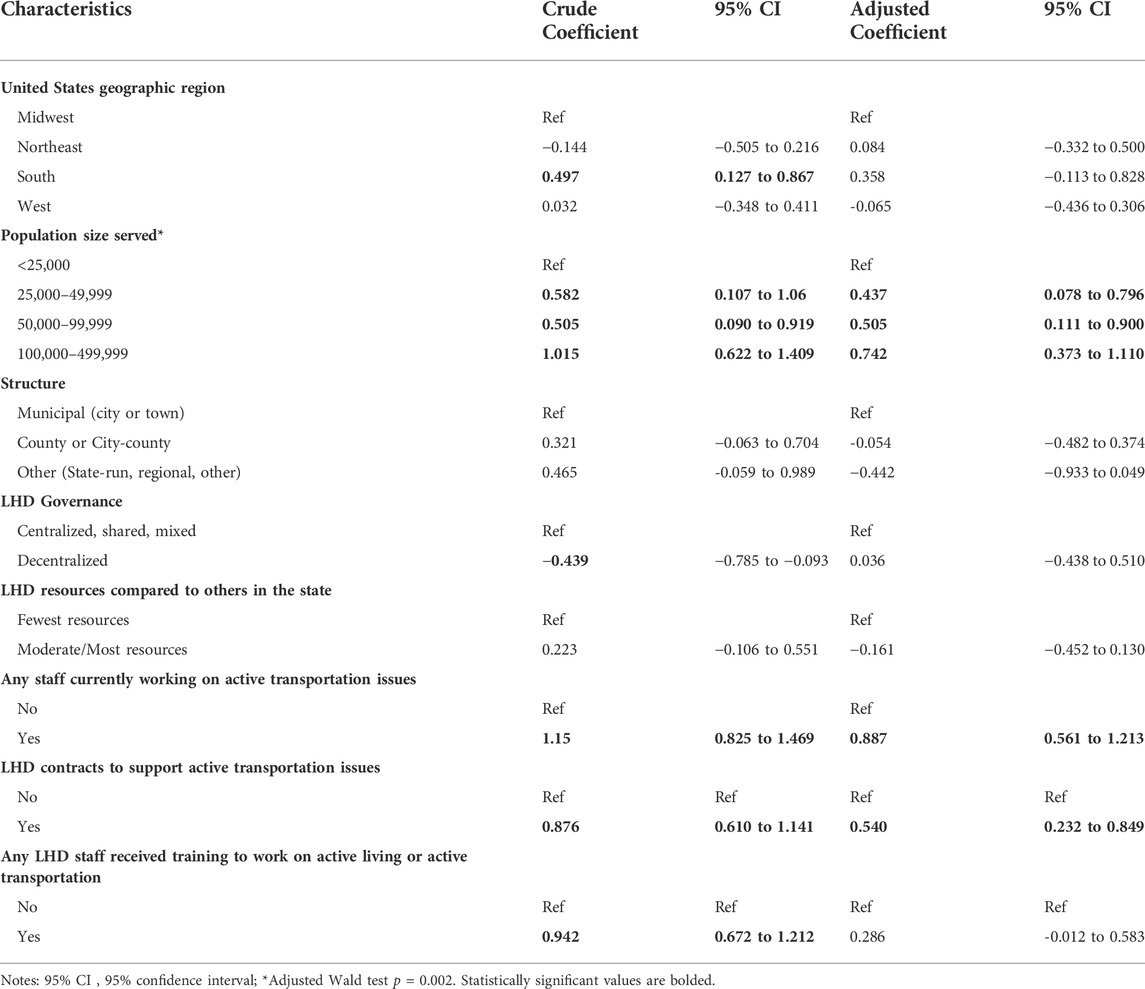

Table 2 reports the results of the crude and multivariate negative binomial regression models. In the multivariate model, population size served was associated with engagement overall. LHDs that serve 25,000 residents or more were more engaged than those with <25,000 residents. LHDs reporting any staff currently working on active transportation issues had higher engagement scores (coefficient = 0.887, 95% CI 0.561–1.213) than their counterparts. Similarly, LHDs with contractors working on issues related to transportation or land use exhibited greater engagement (coefficient = 0.540%, 95% CI 0.232–0.849) compared to LHDs that did not report contracting. United States geographic region and receipt of training were significantly associated with engagement in crude models but the relationships did not remain in the fully adjusted model.

TABLE 2. Results from crude and multivariable negative binomial regression of factors associated with LHD engagement in active transportation activities (unweighted n = 183, weighted n = 2 390).

3.3 Interest in training and technical assistance on activities that pertain to capabilities supportive of active transportation

Table 3 presents LHDs’ rating of their interest in receiving training and/or technical assistance in the areas represented by the activities. High interest in training or technical assistance for specific activities ranged from 12.2% for dedicated staffing to 42.8% for public outreach to community. Level of interest in training and/or technical assistance qualitatively aligned with LHDs’ current engagement in activities that support active transportation decision-making. For instance, LHDs were most interested in training or technical assistance for public outreach to community, but this activity was also most often reported as a major responsibility by LHDs. Similarly, few departments reported strong interested in training or technical assistance for plan or policy development (16.5%) even though a low proportion of departments reported that this activity was a major responsibility (8.7%).

TABLE 3. Interest in training and technical assistance in areas represented by the activities, (unweighted n = 183, weighted n = 2 390).

4 Discussion

Public health participation in transportation and land use policy processes is recommended to elevate physical activity, health and equity considerations. The current study aimed to assess the extent to which United States LHDs engage in a set of cross-cutting activities associated with previously identified capabilities to support engagement. We observed a range in reported engagement by activity. LHDs serving larger populations, having any staff working on active transportation issues, and contracting with an individual or organization on active transportation, reported greater engagement in activities that support active transportation. This study also demonstrated modest but promising interest in assistance for greater engagement among LHDs.

To our knowledge, this is the first time a comprehensive set of activities related to active transportation has been assessed among United States LHDs. Although half of respondents reported LHD staff work on active transportation, the low proportion of LHDs reporting specific activities as major or secondary responsibilities for any staff, may indicate that LHDs find it challenging to move beyond a traditional programmatic lens. The 2016 Profile Survey of LHDs conducted by NACCHO supports our overall finding of low engagement (National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2016). This 2016 survey observed limited involvement in “land use planning activities” including safe, convenient walking or biking access, connecting safe walking and biking routes with mass transit options, road designs that support and encourage walking and biking, and neighborhoods that meet life needs without car use, which has modestly increased since the 2008 Profile survey (National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2016). A mixed methods study of LHD leaders (n = 159) representing all jurisdictions in California reported positive attitudes towards built environment strategies but limited organizational readiness for implementation (e.g., modifying a strategic plan, dedicating staff, or changing organizational structure) (Kuiper et al., 2012). This study concluded that increased organizational readiness, rather than resources, was associated with rich collaborations and modest increased odds of engaging in nine land use and transportation activities, such as zoning or environmental review. Another study reported that only half of the United States frontline public health workforce supports agency involvement in the Public Health 3.0 activities of transportation and built environment (Balio et al., 2019). Bolstering support from public health workforce and leaders for built environment initiatives is a crucial precursor to improving public health engagement in activities to support active transportation which requires additional work.

Activities related to education and collaboration were the most commonly reported by LHDs, specifically public outreach to the community, policy maker education, and collaboration with other public officials in this study. Our findings on collaboration are supported by data from recent NACCHO profile reports (National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2016; National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2019). Encouragingly, the proportion of LHDs reporting partnerships and collaborations (i.e., regularly scheduled meetings, written agreements or shared personnel or resources) with government partners in transportation (22% and 29%) and land use planning (35% and 41%) increased slightly between 2016 and 2019 (National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2016; National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2019). Collaboration and education may be the most feasible activities for LHDs (Lemon et al., 2019) and can serve as stepping stones to engage in other activities examined in this work, especially in light of workforce capacity challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic (National Association of County & City Health Officials (NACCHO), 2020).

Participation in activities pertaining to engagement in policy development and implementation during different phases of the process (plan and policy development, project development and design review, and reviewing and commenting on plans, policies, and projects) was relatively low in this sample. While LHDs may not drive the agenda, they have a critical role to play in these processes. LHD officials who understand what is proposed and what decisions are made are better equipped to influence those decisions to positively impact health and incorporate potential health benefits of built environment changes into their own planning. Less than half of U.S. LHDs report participating in a community health improvement plan containing one or more strategy related to active transportation (Sreedhara et al., 2019), which represents an opportunity for LHDs to serve a critical role in co-learning with and integrating their ongoing community partners into equitable land use and transportation decision processes and working with those partners to move built environment goals in health improvement plans from intentions to more concrete objectives. Furthermore, LHD engagement in policy development and implementation can be enhanced as has been demonstrated by pioneering work in the United States and internationally (Tina Zenzola, 2009; Miro et al., 2014; Rube et al., 2014; Politis et al., 2017).

Engagement in data and assessment was among the least reported activities in our study, and few LHDs indicated a high interest in technical assistance related to this activity. Yet the 2019 Profile report indicates 56% of United States LHDs included data related to built environment factors that impact health in a recent community health assessment (National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2019). The discrepancy between our findings and that of the Profile report suggests that LHDs are engaging in this activity, but they may be doing so within the confines of a public health strategic planning process. Additional guidance may be needed to help public health officials utilize data and assessment skills across sectors. Public health practitioners can play a critical role in contributing to the use and interpretation of metrics used by the transportation sector, which is encouraged to use tools such as the Integrated Transport and Health Impact Model (ITHIM) in its decision-making (Woodcock et al., 2013; Meehan and Whitfield, 2017). ITHIM relies on selection of local health statistics in model generation and produces estimates of complex health indicators related to mortality and disease burden (e.g., years of life lost, years living with disability) as well as costs. It would be an innovative and appropriate dimension of LHDs’ community education role to help inform, interpret and disseminate the information on health impacts and tradeoffs of alternative transportation scenarios in terms of physical activity, roadway traffic injury, air pollution, and equity. This, however, would require resources that many LHDs could not support at this time. Partnerships with academic institutions and community partners may support this capacity.

United States LHDs serving larger populations (>25,000), with any staff working on active transportation issues and those that contracted with an individual or organization on active transportation demonstrated significantly greater engagement in activities that support active transportation decision-making. The 2019 NACCHO Profile demonstrates variation in LHD involvement in land use planning by population size served with higher reported involvement as population size increased (<50,000, 50,000–499,000, >500,000), but it did not assess engagement in specific activities (National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2016; National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2019). A previous analysis of Profile data conducted by this study team together with NACCHO demonstrated that LHDs serving populations ≥500,000 were significantly more likely to engage in land use and transportation policy/advocacy activities than smaller departments (Goins et al., 2016). Any training developed will need to accommodate variation by LHD size as well as rural versus urban setting. Limited and lack of dedicated staffing is a known barrier to LHD engagement in built environment initiatives (Goins et al., 2013; Rube et al., 2014). Similarly, the current analysis found that LHDs with any staff working on active transportation would have greater engagement in the activities that support active transportation. Contracting with non-governmental partners to complete built environment work has been qualitatively identified as important for generating shared ownership of such initiatives across sectors (Rube et al., 2014). Identifying LHD characteristics associated with greater engagement in active transportation can help with the development of targeted resources and trainings.

We observed modest but promising interest in assistance for greater engagement among public health agencies which face tremendous resource challenges. Interestingly, LHDs indicated greater interest in activities for which they reported higher engagement. A 2011 survey of chronic disease workforce in health departments across the United States assessed confidence and interest in training for chronic disease and health promotion competencies and similarly found that most reported an interest in training for policy-related competencies for which they were also most confident (Wilcox et al., 2014). The finding of low priority on training on helping to develop transportation or land use plan or policy was unexpected, given the emphasis on public health engagement in policy generally and specifically built environment policy making to improve physical activity opportunity (Public Health Accreditation Board, 2013; National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2022; National Physical Activity Plan Alliance, 2022). This finding warrants future study. It is possible that LHDs already feel well equipped for such engagement, but that seems unlikely when two-thirds of respondents reported this capability is neither a major nor secondary responsibility. This finding deserves more in-depth consideration, especially given a NACCHO 2016 Profile finding that LHDs “governed by state authorities” were less likely to report involvement in policy work (National Association of County and City Health Officials, 2016). These findings can help prioritize development of training and technical assistance modes and mechanisms, since the breadth and volume of material would be conducive to a training series rather one-time delivery.

Training and technical assistance options include providing directly to LHDs (e.g., through a third-party capacity-building organization), through their national membership organizations such as NACCHO or the National Environmental Health Association, or by assisting state health departments in creating and providing training for their LHDs tailored to their state’s legal and political context as well as public health governance model. Knowledge of relevant processes and rules can hasten the process of building credibility.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

This analysis has several strengths and limitations. It is among the first detailed examinations of LHD activities and interests regarding active transportation, a potentially important contributor to total physical activity. The stratified random sample was representative of United States LHDs in terms of geographic region and population size served. Low representation of LHDs in the South was an artifact of the sampling process. The NACCHO random sample contained multiple departments in Tennessee; these departments are units of the state health department, which declined to allow the departments to respond. Survey weights were applied to generate nationally representative statistics and accounted for survey design, non-response, and analysis of LHDs with complete data. Strong concordance between categorization per the expert panel and LHD engagement and interest demonstrates face validity of the groupings. While it is possible the activities and capabilities are not all-encompassing, the rigorous, multidisciplinary development process supports their use as both a measurement tool and training basis. The cross-sectional design of the study does not permit assessment of causal relationships. The response rate was low although not unusual for survey research. We assessed for response bias and selection bias, but unassessed characteristics could have affected results. It is possible that response was motivated by personal or department interest in the topic; this could mean that levels of reported activity or interest in training are higher for respondents than the full sample. The study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has severely impacted LHD capacity (National Association of County & City Health Officials (NACCHO), 2020).

5 Conclusion

This analysis provides valuable information to inform development of training and technical assistance programs to help public health practitioners working under a variety of resource conditions engage meaningfully in transportation and land use policy processes. The goal is to improve physical activity opportunity through active transportation, with associated benefits for injury prevention, climate change mitigation, and equity. Such a program would respond to calls from public health authorities as well as the built environment community. The findings may also be useful to agencies in structuring grant programs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by UMass Chan Medical School Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MS, KG, and SL contributed to the design of the study. CF organized the database. MS performed statistical analysis. MS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MS, KG, and SL wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by cooperative agreement number U48DP005031 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings and conclusions from this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the experts who provided feedback on the survey instrument and thank the local health departments that participated in the survey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Balio, C. P., Yeager, V. A., and Beitsch, L. M. (2019). Perceptions of public health 3.0: Concordance between public health agency leaders and employees. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 25 (2), S103–S112. Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs. doi:10.1097/phh.0000000000000903

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011). Public health preparedness capabilities: National standards for state and local planning. Atlanta, GA.

Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF) (2016). Physical activity: Built environment approaches combining transportation system interventions with land use and environmental design: The community guide. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/physical-activity-built-environment-approaches#:∼:text=The%20Community%20Preventive%20Services%20Task,interventions%20to%20increase%20physical%20activity (Accessed June 14, 2022).

De Nazelle, A., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Antó, J. M., Brauer, M., Briggs, D., Braun-Fahrlander, C., et al. (2011). Improving health through policies that promote active travel: A review of evidence to support integrated health impact assessment. Environ. Int. 37 (4), 766–777. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2011.02.003

DeSalvo, K. B., Wang, Y. C., Harris, A., Auerbach, J., Koo, D., and O'Carroll, P. (2017). Public health 3.0: A call to action for public health to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Prev. Chronic Dis. 14, 170017. doi:10.5888/pcd14.170017

Dyjack, D. T., Botchwey, N., and Marziale, E. (2013). Cross-sectoral workforce development: Examining the intersection of public health and community design. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 19 (1), 97–99. doi:10.1097/phh.0b013e3182788cff

Goins, K. V., Schneider, K. L., Brownson, R., Carnoske, C., Evenson, K. R., Eyler, A., et al. (2013). Municipal officials' perceived barriers to consideration of physical activity in community design decision making. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 19, S65–S73. doi:10.1097/phh.0b013e318284970e

Goins, K. V., Ye, J., Leep, C. J., Robin, N., and Lemon, S. C. (2016). Local health department engagement in community physical activity policy. Am. J. Prev. Med. 50 (1), 57–68. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.033

Guide to Community Preventive Services (2018). The community preventive services Task force’s built environment recommendation to increase physical activity: Implementation resource guide. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/community-strategies/beactive/downloads/Connecting-Routes-Destinations-implementation-resource-guide-508.pdf (Accessed June 14, 2022).

Harris, P., Friel, S., and Wilson, A. (2015). ‘Including health in systems responsible for urban planning’: A realist policy analysis research programme: Figure 1. BMJ open 5 (7), e008822. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008822

Institute of Medicine (2011). For the public’s health: Revitalizing law and policy to meet new challenges. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 140.

Kuiper, H., Jackson, R. J., Barna, S., and Satariano, W. A. (2012). Local health department leadership strategies for healthy built environments. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 18 (2), E11–E23. doi:10.1097/phh.0b013e31822d4c7f

Lemon, S. C., Valentine Goins, K., Arcaya, M., Aytur, S., Heinrich, K., Maddock, J., et al. (2017). Capabilities for public health agency involvement in land use and transportation decision making to increase active transportation opportunity. Available at: https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/umass-worcester-prevention-research-center/documents/paprn-local-health-department-capabilities-wtasks-2017.pdf (Accessed June 14, 2022).

Lemon, S. C., Goins, K. V., Schneider, K. L., Brownson, R. C., Valko, C. A., Evenson, K. R., et al. (2015). Municipal officials' participation in built environment policy development in the United States. Am. J. Health Promot. 30 (1), 42–49. doi:10.4278/ajhp.131021-quan-536

Lemon, S. C., Goins, K. V., Sreedhara, M., Arcaya, M., Aytur, S. A., Heinrich, K., et al. (2019). Developing core capabilities for local health departments to engage in land use and transportation decision making for active transportation. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 25 (5), 464–471. doi:10.1097/phh.0000000000000948

Maizlish, N., Rudolph, L., and Jiang, C. (2022). Health benefits of strategies for carbon mitigation in US transportation, 2017‒2050. Am. J. Public Health 112 (3), 426–433. doi:10.2105/ajph.2021.306600

Meehan, L. A., and Whitfield, G. P. (2017). Integrating health and transportation in nashville, Tennessee, USA: From policy to projects. J. Transp. health 4, 325–333. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2017.01.002

Miro, A., Perrotta, K., Evans, H., Kishchuk, N. A., Gram, C., Stanwick, R. S., et al. (2014). Building the capacity of health authorities to influence land use and transportation planning: Lessons learned from the Healthy Canada by Design CLASP Project in British Columbia. Can. J. Public Health 106 (1), eS40–eS52. [Internet][eS40-52 pp.]. doi:10.17269/cjph.106.4566

National Association of County & City Health Officials (NACCHO) (2020). Forces of change. The COVID-19 Edition Available at: https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/2020-Forces-of-Change-The-COVID-19-Edition.pdf (Accessed June 14, 2022).

National Association of County and City Health Officials (2016). National profile of local health departments. Available at: https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/ProfileReport_Aug2017_final.pdf (Accessed June 14, 20222017).

National Association of County and City Health Officials (2019). National profile of local health departments. Available at: https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Programs/Public-Health-Infrastructure/NACCHO_ 2019_Profile_final.pdf (Accessed June 14, 20222020).

National Association of County and City Health Officials (2022). Public health 3.0: Transforming communities. Available at: https://www.naccho.org/programs/public-health-infrastructure/public-health-3-0 (Accessed June 14, 2022).

National Physical Activity Plan Alliance (2022). National physical activity plan: Transportation, land use and community design. Available at: https://paamovewithus.org/for-transfer/transportation/ (Accessed June 14, 2022).

Omura, J. D., Kochtitzky, C. S., Galuska, D. A., Fulton, J. E., Shah, S., and Carlson, S. A. (2020). Public health representation on active transportation bodies across US municipalities. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 28, E119–E126. doi:10.1097/phh.0000000000001170

Omura, J. D., Kochtitzky, C. S., Galuska, D. A., Fulton, J. E., Shah, S., and Carlson, S. A. (2022). Public health representation on active transportation bodies across US municipalities. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 28 (1), E119–E126. doi:10.1097/phh.0000000000001170

Physical Activity Alliance (2022). National physical activity plan. Transportation, land use, and community design. Available at: https://paamovewithus.org/for-transfer/transportation/ (Accessed June 14, 2022).

Pilkington, P., Powell, J., and Davis, A. (2016). Evidence-based decision making when designing environments for physical activity: The role of public health. Sports Med. 46 (7), 997–1002. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0469-6

Politis, C. E., Mowat, D. L., and Keen, D. (2017). Pathways to policy: Lessons learned in multisectoral collaboration for physical activity and built environment policy development from the Coalitions Linking Action and Science for Prevention (CLASP) initiative. Can. J. Public Health 108 (2), e192–e198. doi:10.17269/cjph.108.5758

Prevention CfDCa (2022). The public health system & the 10 essential public health services. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/zz-sddev/essentialhealthservices.html (Accessed June 14, 2022).

Public Health Accreditation Board (2013). Standards and measures. Version 1.5. Available at: https://www.phaboard.org/wp-content/uploads/SM-Version-1.5-Board-adopted-FINAL-01-24-2014.docx.pdf (Accessed June 14, 2022).

Rube, K., Veatch, M., Huang, K., Sacks, R., Lent, M., Goldstein, G. P., et al. (2014). Developing built environment programs in local health departments: Lessons learned from a nationwide mentoring program. Am. J. Public Health 104 (5), e10–e18. doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301863

Sallis, J. F., Spoon, C., Cavill, N., Engelberg, J. K., Gebel, K., Parker, M., et al. (2015). Co-Benefits of designing communities for active living: An exploration of literature. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 12 (1), 30. doi:10.1186/s12966-015-0188-2

Sallis, R., Young, D. R., Tartof, S. Y., Sallis, J. F., Sall, J., Li, Q., et al. (2021). Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes: A study in 48 440 adult patients. Br. J. Sports Med. 55 (19), 1099–1105. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-104080

Smart Growth America (2021). Smart Growth America. Dangerous by design. Available at: https://smartgrowthamerica.org/dangerous-by-design/ (Accessed June 14, 2022).

Sreedhara, M., Goins, K. V., Aytur, S. A., Lyn, R., Maddock, J. E., Riessman, R., et al. (2017). Qualitative exploration of cross-sector perspectives on the contributions of local health departments in land-use and transportation policy. Prev. Chronic Dis. 14, 170226. doi:10.5888/pcd14.170226

Sreedhara, M., Valentine Goins, K., Frisard, C., Rosal, M. C., and Lemon, S. C. (2019). Stepping up active transportation in community health improvement plans: Findings from a national probability survey of local health departments. J. Phys. Act. Health 16 (9), 772–779. doi:10.1123/jpah.2018-0623

Tina Zenzola, J. Y. (2009). Creating healthy built environments: Case studies of local health departments in California. Available at: http://ph.lacounty.gov/place/docs/LA_Final.pdf (Accessed June 14, 2022).

Wilcox, L. S., Majestic, E. A., Ayele, M., Strasser, S., and Weaver, S. R. (2014). National survey of training needs reported by public health professionals in chronic disease programs in state, territorial, and local governments. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 20 (5), 481–489. doi:10.1097/phh.0b013e3182a7bdcf

Keywords: active transportation, local health department, land use, transportation, built environment, policy

Citation: Sreedhara M, Goins KV, Frisard C and Lemon SC (2022) United States local health department engagement in activities that support active transportation considerations in land use and transportation policies: Results of a national survey. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:971272. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.971272

Received: 07 July 2022; Accepted: 22 September 2022;

Published: 21 October 2022.

Edited by:

Riccardo Buccolieri, University of Salento, ItalyReviewed by:

Adam Radzimski, Adam Mickiewicz University, PolandLinda Kay Silka, University of Maine, United States

Copyright © 2022 Sreedhara, Goins, Frisard and Lemon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stephenie C. Lemon, c3RlcGhlbmllLmxlbW9uQHVtYXNzbWVkLmVkdSYjeDAyMDBhOw==

Meera Sreedhara

Meera Sreedhara Karin Valentine Goins

Karin Valentine Goins Stephenie C. Lemon

Stephenie C. Lemon