- School of Business, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan, China

To verify the importance of optimizing a business environment and improving the level of human capital structure to promote economic development, this study employs a panel data of 30 Chinese provinces from the period 2008–2019 and utilizes the spatial Durbin model and quantile regression model to analyze the relation between a business environment, human capital structure upgrading, and economic development quality. We find that the quality of economic development has a strong spatial correlation and the improvement in the business environment promotes human capital structural upgrading and economic development quality. Human capital structural upgrading plays a significant intermediary role, through which improvement in the business environment affects economic development quality. Considering the huge differences in the level of economic development in different regions of China, we also conduct a regional heterogeneity analysis. We find that the promotion effects of the business environment and advanced human capital structure on economic development quality are significant within the sample period, and their promotion effects are significantly heterogeneous and asymmetric across quartiles, indicating that there is heterogeneity in the intensity of dependence of economic development quality on advanced human capital structure and business environment at different stages of economic development. Moreover, by observing the impact trends in the eastern, central, and western regions, we find that the impact of the business environment and human capital structure on the quality of economic development varies somewhat across provinces. This suggests that the eastern and central regions need to strengthen the optimization of the business environment, while the eastern and western regions should pay more attention to the improvement of the level of the advanced human capital structure.

1 Introduction

After over 40 years of reform and opening up, China’s economy surged due to its preferential policies and favorable factor prices. But due to a sharp increase in labor and land costs, diminishing competitive advantages in resource environments and demographic dividend, and mounting pressure derived from trade barriers imposed by the US, the extensive development model based on scaling-up in China becomes hard to sustain. To respond to the changes in major social contradictions and realize sustainable economic development, there has been a pressing need for improving economic development quality. A good business environment is an important grip to maintaining good government–enterprise relations and stable economic growth. In recent years, the Chinese government has spared no efforts in bettering the business environment. A series of key planning and policies, which are considered a major way for improving economic development quality in the new era, have been issued in China. According to Doing Business 2020 by the World Bank, China jumped to the 31st, showcasing a fast ranking improvement in seven consecutive years and international recognition of China’s efforts to bettering its business environment. Human capital is the key engine of economic growth (Škare and Lacmanović, 2015). China’s human capital structure has experienced significant changes toward an upgraded one. The “demographic dividend” is gradually fading and the “talent dividend” is becoming increasingly significant. The transition from the “demographic dividend” to a “human capital dividend” constitutes the key to improvement in economic development quality. At the same time, due to many factors such as resource endowment and development conditions, the human capital structure in the process of optimization and adjustment, high-quality human capital is more inclined to transfer to cities with developed economies and superior business environments. The human capital structure matches the economic and social structure to maximize the role (Čadil et al., 2014b). The huge economic development gap among Chinese provinces prompts us to study how to promote the quality of economic development in each region of China by optimizing the business environment and enhancing the advanced level of human capital structure. It is of great practical significance to explore new paths of economic development quality and to achieve the goal of coordinated regional economic development.

Current research exhibits explorations on the relation between the business environment and economic development and confirms the positive relation between these two. For instance, a favorable business environment significantly promotes economic development (Easton and Walker, 1997; Alesina et al., 1998; Nelson and Singh, 1998; De Haan and Sturm, 2000). Countries with worsening business environments experience a slowing-down growth rate (Nelson and Singh, 1998). The main reason is that the favorable business environment effectively lowers the transaction cost for companies (Fabová and Janáková, 2015) and helps attract foreign direct investment (FDI) (Economou, 2019; Li et al., 2021). In fact, human capital plays an essential role in driving economic development. Furthermore, studies show that human capital is the key factor and engine for economic growth (Tsaurai and Ndou, 2019; Musibau et al., 2019) and is also the key factor which explains the status difference between developed and developing countries Acemoglu et al., 2014). On the one hand, the quantity of human capital increases the level of knowledge and innovation, which ultimately propels economic development (Romer, 1989; Benhabib and Spiegel, 2002). Moreover, the accumulation of human capital stock delivers significant spillover effects on economic growth (Benjamin, 1997). On the other hand, structural improvement in human capital is also of great importance to economic growth (Fleisher et al., 2010). The extant literature has not reached a consensus on this issue. Some scholars believe that inequality in the distribution structure of human capital is negatively correlated to economic growth (Park, 2006). A high-level human capital structure and low-level human capital structure deliver different effects on economic growth, and there exists an optimal human capital structure for the economy (Feng & Li, 2019). However, some scholars still believe that the relationship between the two is not significant (Lopez et al., 1998). In a nutshell, the impact of the level of the human capital structure on economic growth is complex. Meanwhile, the quality of systems affects, to some extent, human capital’s role in economic growth (Nelson and Singh, 1998). This raises a topic of great theoretical and practical significance: in the face of continuous improvement of the regional business environment and the obvious trend of advanced human capital structure, what kind of spatial and temporal evolutionary characteristics does the quality of economic development in each province of China present at present? How do the business environment and the advanced human capital structure affect the quality of economic development? Does it show heterogeneity due to regional differences? Does the impact of the advanced human capital structure on the quality of economic development have a mediating effect? The study of these questions will help clarify the economic development quality of each province in China, grasp the strengths and weaknesses of each province’s economic development quality, and has important theoretical and practical significance for narrowing the provincial economic gap as a whole and promoting coordinated provincial economic development. The research results can also provide some evidence for the economic development of other countries in heterogeneous regions.

In summary, the current research investigates the relation between the business environment and human capital or the relation between the business environment and economic development. But few analyses have been conducted on the three under a unified framework. To bridge this research gap, this study incorporates the business environment, human capital structural upgrading, and economic development quality into a model where the relation between them and their impact mechanism are examined. Our study contributes to the existing literature in the following aspects. First, the impact of the business environment on the advanced human capital structure is examined, and the moderating effect of the advanced human capital structure on the business environment to promote high-quality economic development is discussed in depth; second, considering the great differences in resource endowments and development conditions among different provinces, the differences in the impact of the business environment and advanced human capital structure on high-quality economic development in different regions and the reasons for them are explored. Third, the relationship between the business environment, advanced human capital structure, and economic development quality is studied using spatial quantile regression models. The spatial quantile regression model used in this study provides a more accurate understanding of spatial dependence. The study also further investigates the impact of business environment optimization on high-quality economic development since the 18th National Congress. The findings of this study can be used as a reference for local governments to promote the high-quality development of the regional economy.

2 Theoretical analysis and hypothesis

2.1 Relation between the business environment and economic development

A business environment is the comprehensive external conditions which market entities come across during the process of entry, operation, and exit, including market, government, legal system, and cultural environment. Improving the business environment is a vital method to galvanize economic development and is an important measure to elevate economic development quality. A favorable business environment helps debunk the wayward judgment that “GDP is everything” in economic development. It adjusts the overall relation among regions, between urban and rural areas, and between the economy and society. A favorable business environment is conducive to developmental balance on varied fronts, organic development of society, and improvement in economic development quality. Business environment improvement helps increase per capita income (Gilanders and Whelan, 2014) and significantly promotes economic growth (Mohamadreza, 2012). Meanwhile, business environment improvement serves as an impetus for companies in innovation activities and productivity progress (Gogokhia and Berulava, 2021), which is beneficial to attract foreign direct investment and climb up the value chain (He et al., 2021). In addition, a favorable business environment not only lowers the cost of starting a business and offers convenience and support in market entry and exit but also reduces companies’ costs in operation (Yu and Ramanathan, 2013). Therefore, companies increase their R&D and innovation input, which in turn improves economic development quality. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis: H1. Business environment improvement betters economic development quality.

2.2 Impact of human capital structural upgrading on economic development quality

The endogenous growth theory recognizes human capital as the key factor for the absorption and spread of technologies. As the carrier for knowledge and technology, human capital substantially increases total factor productivity and economic development quality through such ways as knowledge acquisition, technological innovation, and R&D result transfer. The higher the human capital level is, the more evident its positive effect will be (Teixeira and Queirós, 2016). Human capital bolsters up quality economic growth featured by innovation and industrial structural upgrading. Improving effective allocation of human capital represents the fundamental way for breakthroughs in the quality of economic growth (Li and Nan, 2019). In the special period of economic transformation, human capital with higher education is the vital force for industries to introduce new technologies (Vandenbussche et al., 2006; Goedhuys and Veugelers, 2012; Balsmeier and Czarnitzki, 2017). Human capital upgrading is different from human capital stock because the former better explains regional variance in the economic growth of China. Human capital is the engine for economic growth (Lucas, 1988) because high-level human capital not only realizes better technological innovation via “learning by doing” (Romer, 1990) but also absorbs technological spillover more effectively and engages in emulation and innovation quickly (Caselli and Coleman, 2006). Therefore, human capital upgrading is beneficial to the cultivation of innovative talents and promotion of technological progress. When the innovation-driven development strategy is implemented, technological progress will invariably bring about quality improvement for economic growth. Based on this, we propose hypothesis 2. H2. Human capital structural upgrading is beneficial to improvement in economic development quality.

2.3 How the business environment impacts human capital structural upgrading

As an important way for comprehensive reforms, improvement in institutional quality increases the accumulation rate of human capital on the one hand and lifts the utilization rate of human capital on the other hand. This study believes that the business environment affects human capital structural upgrading through the following mechanisms: first, a convenient business environment cuts companies’ cost of starting a new business, reduces formalities and procedures, and lowers the threshold for starting a business. More high-quality and capable talents with innovative minds are attracted to investment and start-up, which invigorates market vitality. Generally, high-quality human capital possesses absolute advantages in start-up and employment (Lazear, 2004). Put differently, excess procedures, low efficiency, and long process of business registration approval add transaction costs for start-up and affect the entrepreneur’s response to business opportunities (Dreher and Gassebner, 2013). Slashing institutional transaction costs means that more operational costs are saved for high-level human capital and higher start-up benefits can be acquired. With competitive advantages in innovation and start-up, high-level human capital tends to forsake employment opportunities, even though they boast plenty of them in the labor market, and engage in high-risk start-up activities. They are more likely to grow to be the entrepreneurs described by Joseph Alois Schumpeter because their start-up quality is higher, and their start-ups are more probable to increase economic development quality; second, improving the business environment creates more job opportunities. A convenient business environment not only promotes the number and quality of the start-up but attracts more foreign direct investment, which in turn creates more job opportunities. High-quality human capital tends to migrate to regions with favorable business environments. As a result, improvement in the business environment promotes human capital structural upgrading. Therefore, we propose hypothesis 3. H3. Improvement in the business environment promotes human capital structural upgrading.

3 Econometric model, methodology, and data

3.1 Econometric model setting

The quality of economic development showcases space relevance and is influenced by the development level of the neighboring area. Traditional econometric models fail to unravel its spatial effects and exhibit a bias to some extent. Moreover, considering the imbalance of economic development quality in terms of spatial distribution among provinces of China, we use spatial econometric models (Fredriksson and Millimet, 2002), including the spatial autoregressive regression (SAR), spatial error model (SEM), and spatial Durbin model (SDM). Their respective calculation method is shown in Eqs. 1–3.

Spatial autoregressive regression (SAR):

Spatial error model (SEM):

Spatial Durbin model (SDM):

where I represents the dependent variable while x is the independent variable. α is intercept. ρ denotes the spatial autocorrelation coefficient. w is the spatial weights matrix. z is the control variable.

where i refers to the province and t represents the year. HQ is the economic development quality. Dtf is the business environment which shows the relation between the local government, market, and enterprise. Hstruc is human capital structural upgrading, which reflects the level of regional human capital development. To avoid estimation bias caused by variable omission, we add a control variable vector related to economic and regional characteristics (Z) in model (4) and control time-fixed effects.

3.2 Variable and statistical description

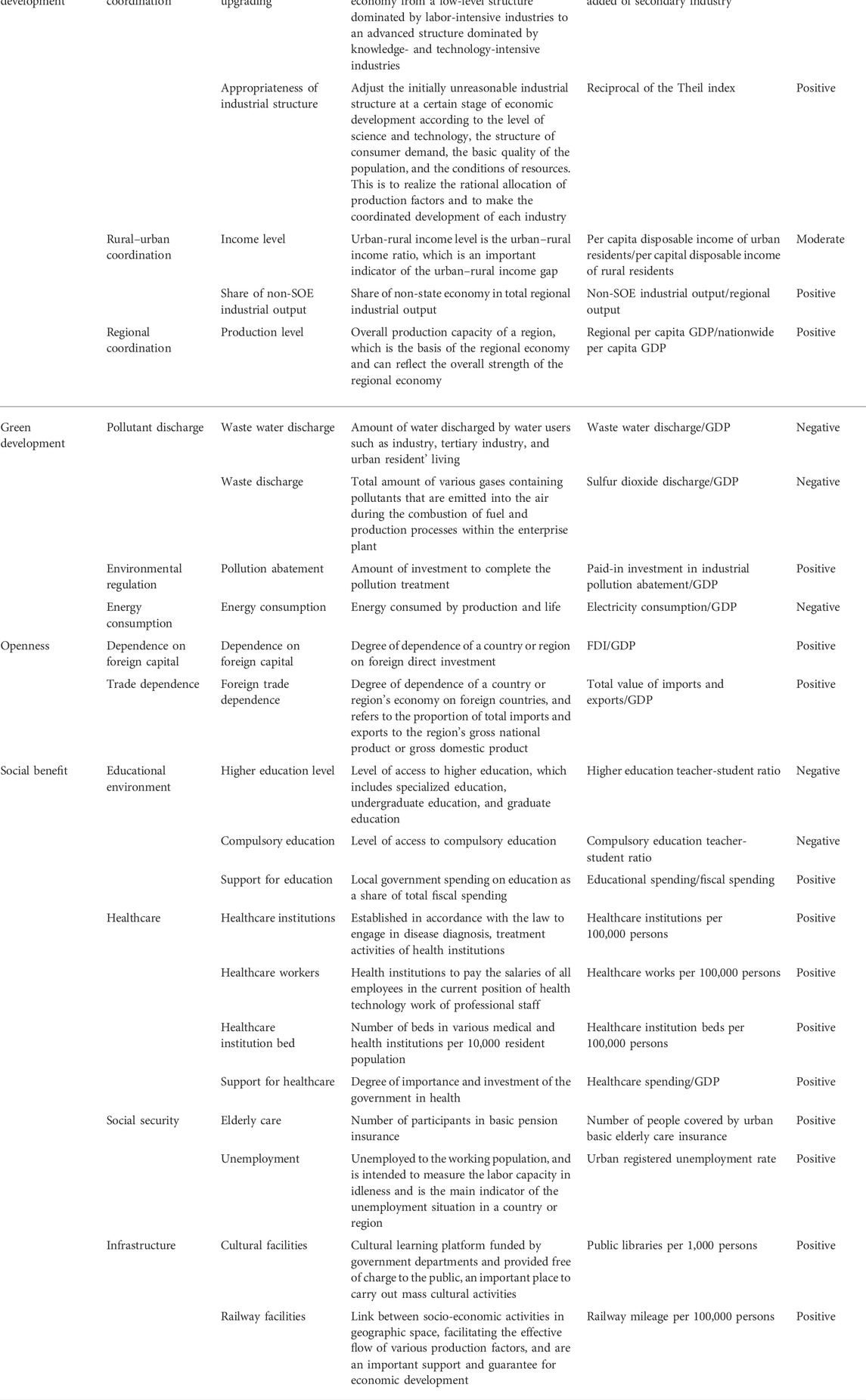

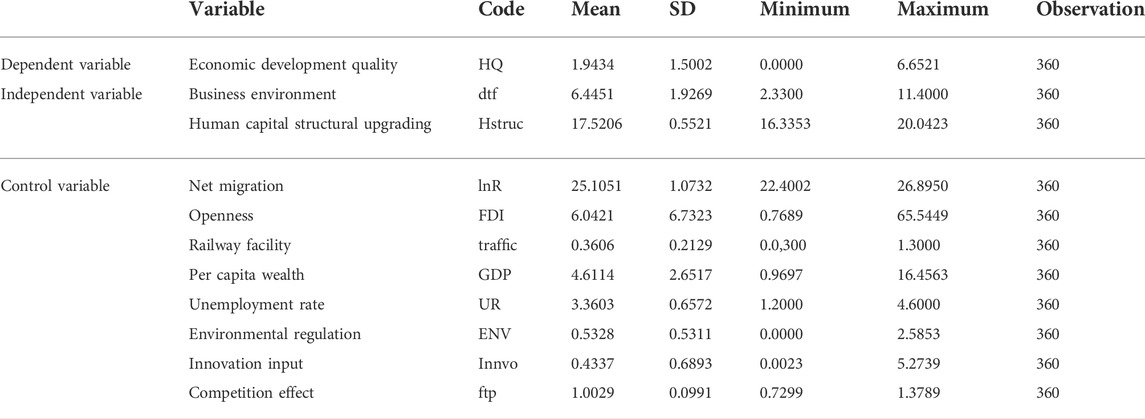

1. Dependent variable: economic development quality (HQ). Economic development quality is a complex and systematic indicator which is a comprehensive evaluation of the economic development of a country or a region. Multiple measurements have been proposed, but a universally accepted method is yet to be developed. Some studies adopt a monotonic indicator, for example, per capita GDP, to evaluate the economic development quality (Ding et al., 2021), which fails to capture the multi-layered characteristics of economic development quality. This study refers to the practice of Jiangguo Du et al. (2020) and selects 27 indicators from the five dimensions of innovation-driven development, coordinated development, green development, openness, and social benefit to construct a comprehensive evaluation system for economic development (see Table 1).

As potential estimation bias may be caused by measurement via a monotonic method, it is advised to combine different measurement methods to optimize weights (Du et al., 2015). Therefore, this study refers to the practice of Tang et al. (2020) and employs the “dynamic-static” measurement method, or the “vertical and horizontal” scatter degree method (VHSD) and entropy method (EM) to construct a VHSD–EM model to measure the indicator weight of economic development quality. Time factors and the information contained in the indicators are also incorporated into the identification of weights. As such, economic development quality can be effectively measured, which resolves the limit of the static measurement method where dynamic comparison among the measured subjects is impossible and reflects the developmental differences among the measured subjects to the greatest possible extent (Tang et al. (2020)).

First, the inverse and moderate indicators in the original indicator data are forwarded. It is assumed that there are a total of n tertiary indicators of m provinces in K different years of the original indicator data, where

If

If

If

where

Next, the data after forwarding are dimensionlessized. The specific formula is as follows:

where,

Finally, according to the weight coefficients obtained from the VHSD–EM model, a linear weighting method is used to sum up the weights layer by layer to obtain the comprehensive evaluation function

where

In addition, to facilitate visual comparison without loss of generality, the technical treatment of panning of

In this way, the integrated evaluation function values, i.e., HQ, are all greater than or equal to 0.

2. Key independent variables: 1) business environment (dtf). As an important factor impacting economic development, the business environment reflects the comprehensive level of the regional political and economic systems. We adopt a marketization index from Marketization Index of China’s Provinces NERI Report 2019 by Fan Gang and Wang Xiaolu to denote the business environment. The marketization index is weighted by indicators from the five dimensions of government–market relations, development of non-state-owned economy, development level of a product market, development level of a factor market, and development of market intermediary organizations and legal environments. There is a total of 18 second-tier indicators under the five dimensions. Specific discussions on indicators from the five dimensions are presented in empirical analysis to explore the impact of administration environment, economic structural environment, product market environment, factor market environment, and rule-of-law environment on economic development quality. 2) Human capital structural upgrading (Hstruc): human capital structural upgrading is a regular evolution where human capital with higher education gradually replaces human capital with primary education. It is a process where a country or a region, by optimizing the human capital structure, promotes coordinated development of human capital at different levels to satisfy the demand for high-level human capital due to socioeconomic development. This study refers to the practice of Du et al. (2020)in measuring human capital structural upgrading, that is, to measure human capital structural upgrading at the provincial level through a vectorial angle method. The specific procedures are as follows: first, we group migrants into five categories of illiteracy or near illiteracy, primary school, middle school, high school, and vocational college and above. The share of each group in the total population surveyed is adopted as components of the spatial vector to construct a five-dimension spatial vector

where

In Eq. 7,

3. Control variables. To further alleviate estimation bias caused by variable omission, we control the variables related to urban and economic characteristics in model (4). Variables related to urban characteristics controlled in model (4) include railway facility (traffic), per capita wealth (GDP), openness (FDI), unemployment rate (UR), and net migration (lnR). Variables related to the economic development mode controlled in the model include innovation input (innvo), competition effect (ftp), and environmental regulation (ENV), among others. 1) Railway facility (traffic) is denoted by railway mileage per ten thousand persons of the province. 2) Openness (FDI) reflects the utilization level of external resources and is measured by the share of FDI in GDP. 3) Net migration (lnR). Adequate population migration accelerates the spread of knowledge and technology, improves resource allocation efficiency, and effectively galvanizes innovation dynamism. This study uses the difference between permanent residents and household population to measure net migration, which is denoted by R. 4) Innovation input (innvo). Innovation input is the material foundation for innovation, which directly propels innovation-driven development. The higher the innovation input is, the more capable a region is in innovation. Innovation input is measured by per capita research and experiment development spending. 5) Per capita wealth (GDP) is measured by the per capital GDP of a province. 6) Environmental regulation (ENV) is denoted by the ratio of urban investment in industrial pollution abatement to industrial value-added. 7) Unemployment rate is measured by the registered unemployment rate of a province and is denoted by UR. 8) Competition effect (ftp) is indicated by total factor productivity. Data description and descriptive statistics of the aforementioned dependent variable, key independent variables, and a series of control variables as shown in Table 2.

Based on the availability and validity of data, this study selects panel data from 30 Chinese provinces (Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan excluded) from 2008 to 2019 as the research object. All original data were obtained from China Statistical Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook on Environment, the database of the National Bureau of Statistics of China, and statistical yearbooks of the provinces. Missing data are supplemented through median value and trend extrapolation.

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Measurement of regional economic development quality

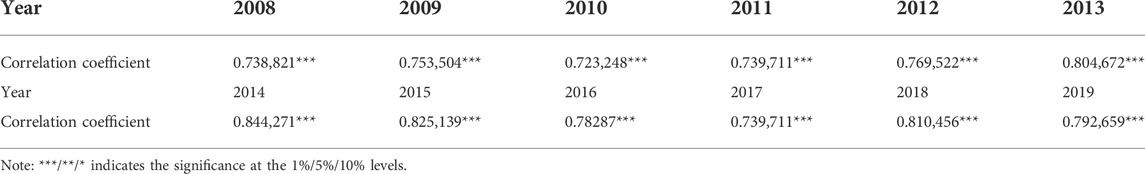

Du et al. (2015) argued that a combined evaluation method could be employed only when there is consistency in the results obtained from each single evaluation method. Therefore, this study employs Spearman’s rank correlation test to verify the stability of the VHSD–EM model. According to the VHSD–EM model and its index evaluation system, the Spearman’s rank correlation test was conducted on the scores obtained from the “vertical and horizontal” pull-down method and the entropy weighting method by using MATLAB software. The results are shown in Table 3.

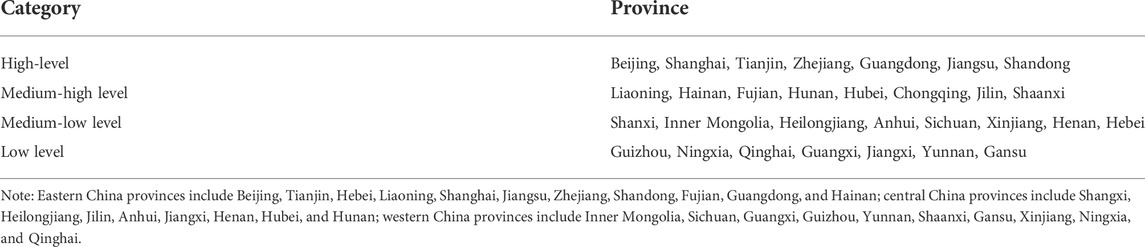

As shown in Table 3, the calculation results of the VHSD and EM method indicate a high degree of correlation, whose results are statistically significant at the 1% level. Estimate results through these two methods are, therefore, consistent. In another word, the VHSD–EM model constructed in this study is stable, and the comprehensive evaluation results estimated by this model reflect the real level of the subject which has been assessed. We obtain a comprehensive evaluation values of Chinese provinces’ economic development quality for the period from 2008 to 2019 (detailed results are not shown here due to space constraints). The results show that most Chinese provinces indicate varying degrees of improvement in economic development quality during the inspection period. The fundamental reason for overall improvement in regional economic development quality lies in the betterment of the business environment, steady progress in supply-side structural reform, and transformation of economic development philosophy among Chinese provinces. Based on the estimate results of Chinese provinces’ economic development quality from 2008 to 2019, we use the annual mean value of each year as the benchmark value and use the quartile method to divide the provinces into four development quality categories: high level, medium-high level, medium-low-level, and low level (see Table 4).

Table 4 demonstrates evident spatial differences among Chinese provinces in terms of economic development quality, with a certain degree of region-based clustering. Provinces with relatively high levels of economic development quality are those which the Yangtze River runs through or those in the eastern seaboard area while the western region shows a low level. The main reason is that eastern provinces boast favorable economic foundations, experience rapid urbanization, and enjoy convenient transportation and rich human resources. Chongqing Municipality and Hubei Province, which the Yangtze River runs through, showcase strong performance in recent years in terms of economic development quality. Their performance is mainly attributable to the elevation of scientific and technological innovation, which helps sustain rapid economic development. It is worth noting that industrial structural improvement in Inner Mongolia and Shaanxi is obvious. Per capita GDP in these two regions maintain steady growth. Livelihood also showcases major improvements, indicating an eye-catching performance in terms of overall economic development quality.

4.2 Spatial correlation analysis

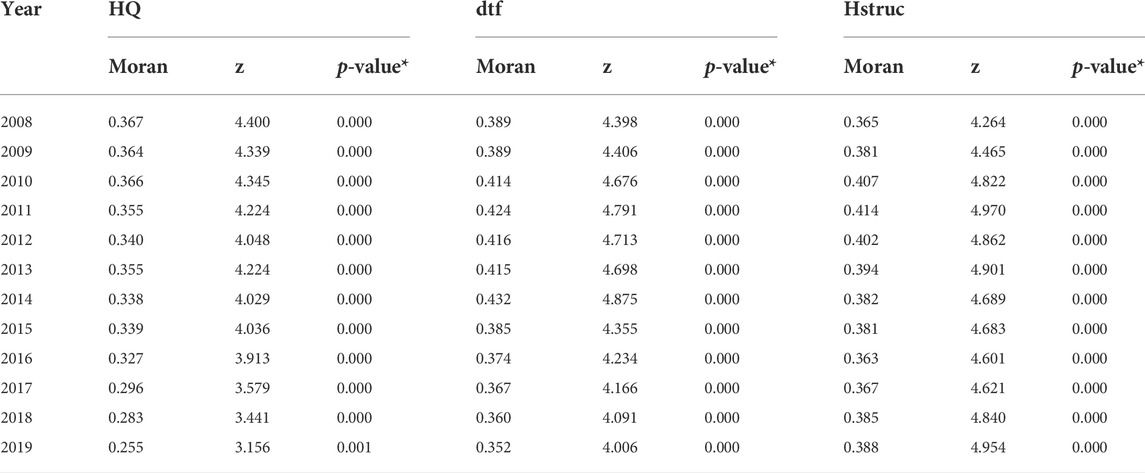

Before we conduct the regression, we need to check the potential existence of the spatial effects (Ren et al., 2021). A precondition for the utilization of the spatial econometric model is the spatial correlation among research subjects, which is often checked by Moran’s I. When Moran’s I ranges from 0–1, a positive spatial correlation among the level value of the neighboring area exists; when Moran’s I falls between -1 and 0, a negative correlation among the level value of the neighboring area exists. The higher the absolute value of Moran’s I, the higher the spatial correlation will be. To examine the spatial correlation of economic development quality, this study constructs the following four spatial weights matrices. The first is the geographical distance weight matrix (W1) where

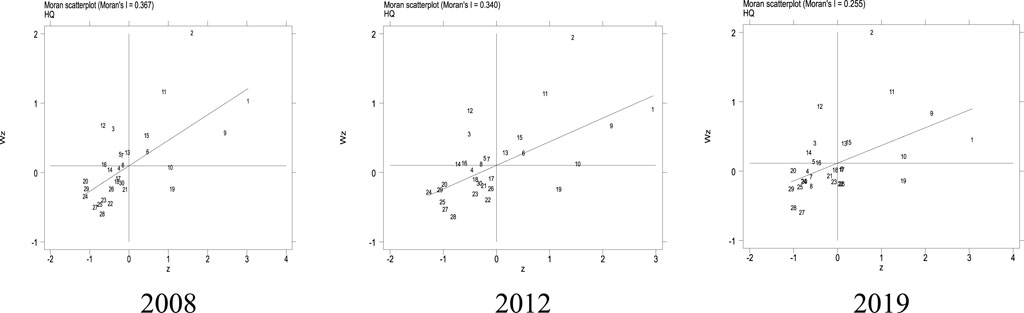

Based on Table 5, in spatial weight matrix W1, global Moran’s I of economic development quality is significantly positive during the inspection period at the 1% level, meaning that the economic development quality of Chinese provinces is significantly and positively correlated in terms of spatial distribution and can be analyzed through the spatial econometric model. Specifically, instead of random scattering, economic development quality among Chinese provinces is distributed in a cluster or regions with a similar level of economic development quality cluster together. In terms of trend, Moran’s I increases over time, indicating a growing spatial correlation of economic development quality in the inspection period. Moreover, the business environment and human capital structure also showcase spatial correlation.

TABLE 5. Global Moran’s I of economic development quality, business environment, and human capital structural upgrading.

Global spatial correlation reflects the overall correlation of spatial variables, which may miss non-typical characteristics of local regions (Anselin, 1995). As such, local space correlation analysis on economic development quality is required. The most commonly used indicator for that is local Moran’s I. The test result of local Moran’s I in Figure 1 further corroborates the significant spatial dependence of economic development quality among provinces. Most provinces indicate clustering characteristics similar to their neighboring provinces. Provinces with high-quality economic development are often surrounded by neighbors with high-quality economic development while the neighboring provinces with low-quality development are also experiencing low-quality growth.

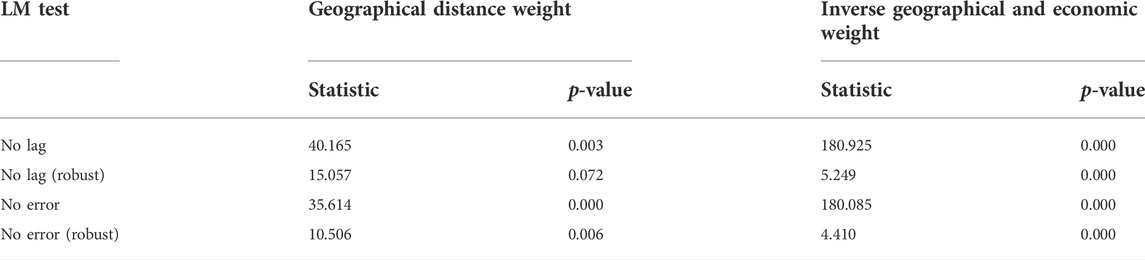

Even though Moran’s I test indicates significant spatial correlation in residual error, such a test cannot identify whether the spatial lagged model or spatial error model should be adopted. Therefore, we need to run the Lagrange Multiplier test or LM test for identification. The model with more significant LM statistics is the suitable one. If the two models showcase the same significance level in terms of LM statistics, robust LM statistics are required. As shown in Table 6, in geographical distance weight matrix (W1) and inverse geographical and economic distance weight matrix (W3), both LM-Lag and LM-Error are statistically significant at the 1% level. Further identification by robust LM is required, that is, identification through robust LM-Lag and robust LM-Error. The robust LM test value of the spatial lagged model and spatial error model is statistically significant. The adoption of the spatial Durbin model (SDM) is basically confirmed. But further LR and Wald test should be conducted.

To further corroborate the econometric model, we use the Wald/LR to test whether the SDM can be regressed as the SLM/SEM. Results significantly reject the original hypothesis, meaning that the adoption of the SDM for follow-up investigation is robust.

Last, we need to determine which SDM model should be applied in our study, the SDM with fixed effects or the SDM with random effects. We applied the Hausman test in our study (Ren et al., 2021). According to the Hausman test results, the p-value is below 0.05, which rejects the original hypothesis and supports the adoption of a fixed effect model. Moreover, joint significance test results (selection of ind, time, and both) significantly reject original hypothesis. By comparison, we find that the time-fixed effect model delivers the optimal results. Therefore, follow-up spatial analysis is based on time-fixed effects.

4.3 Spatial econometric analysis

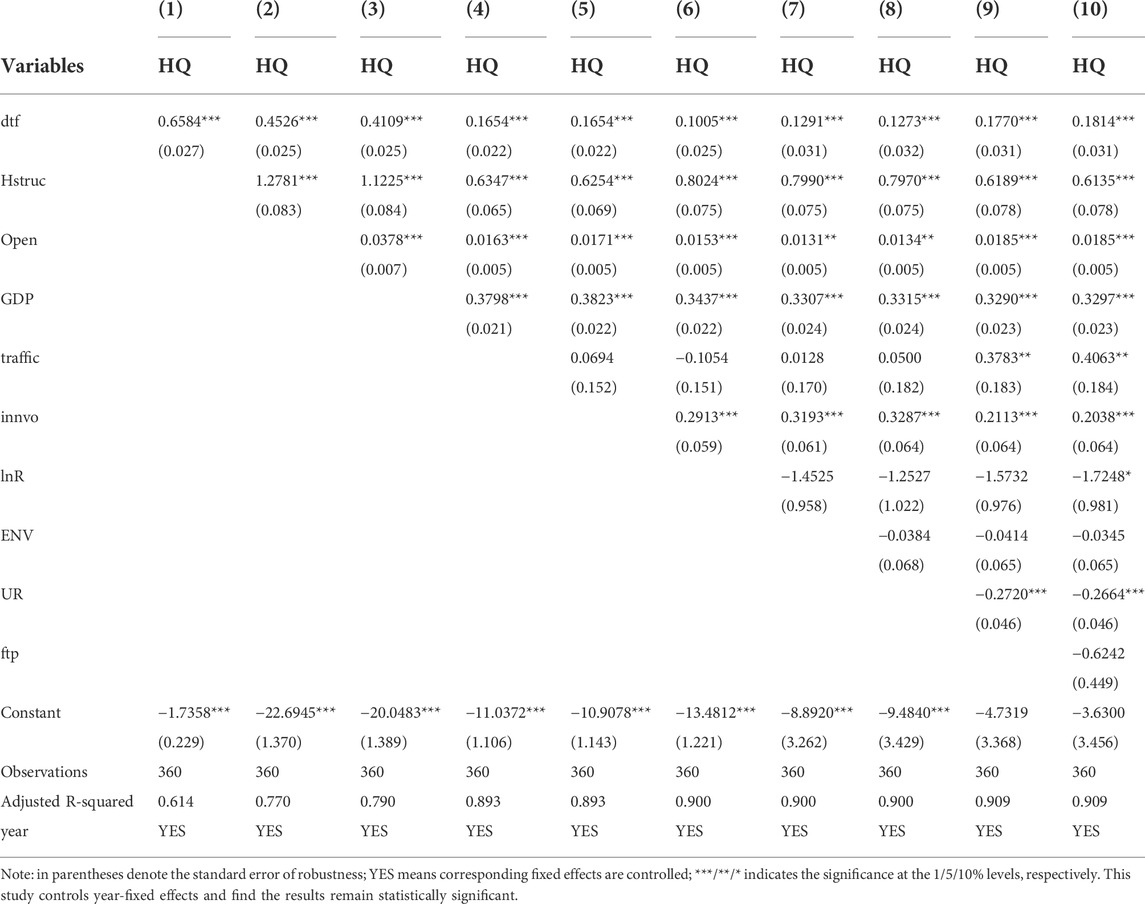

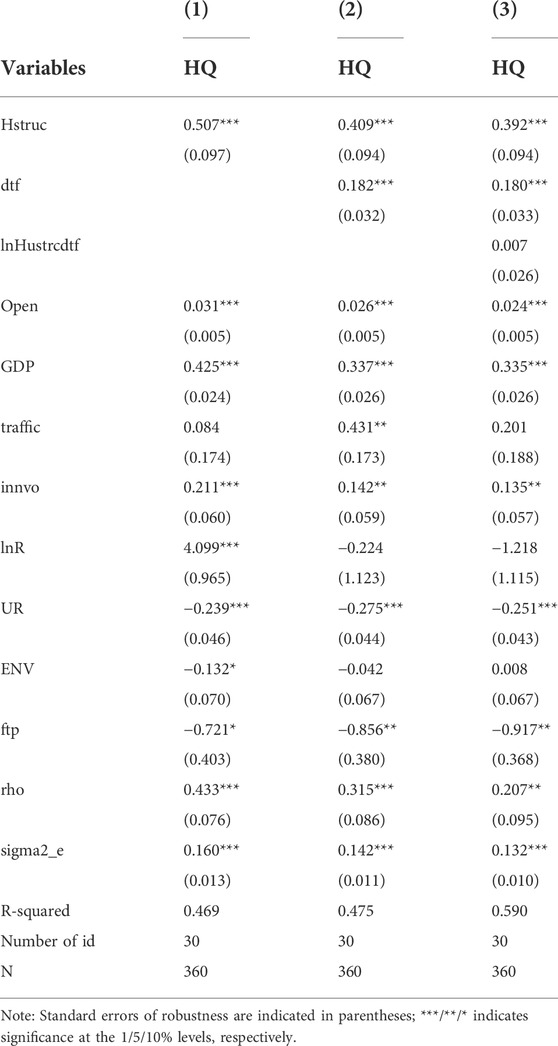

As the spatial Durbin model with fixed effects is adopted for spatial econometric analysis, this study employs the econometric software STATA to run spatial econometric analysis. First, the variance inflation factor (VIF) of the main model and VIF of the single independence variable are lower than 10, demonstrating that there is no multicollinearity among independent variables. As the economic development quality is affected by many factors, there may be an omission in variable selection. To alleviate the influence of potentially omitted variables, this study constructs the model from generalized consideration to specific issues. After identifying the specific impact of the business environment and human capital structural upgrading on economic development quality, we gradually add other control variables on the basis of basic control variables for parameter estimation. As such, control variables’ impact on economic development quality can be revealed. The results are shown in Table 7.

“Generalized” estimate results in Table 7 show that the business environment and human capital structural upgrading consistently and positively affect economic development quality. The direction of different variables is basically the same and indicates little change, demonstrating the robustness of estimate results. Business environment improvement significantly lifts economic development quality. In another word, regions with a better business environment enjoy higher economic development quality. Elevation in the human capital structure also effectively betters economic development quality. Hypotheses 1 and 2 are corroborated.

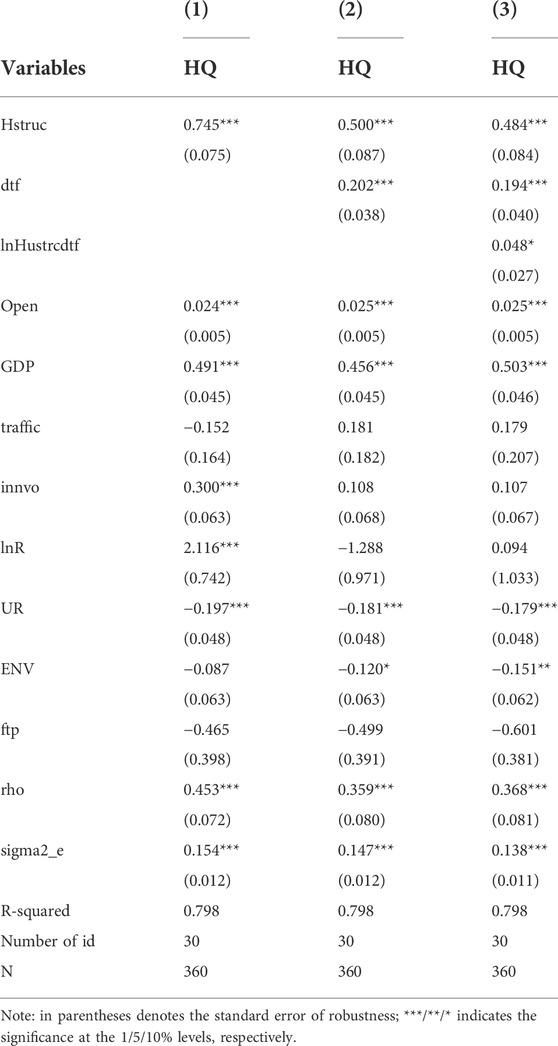

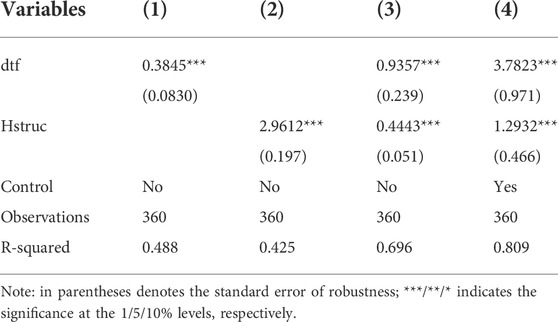

The parametric panel fixed-effects regression model cannot explain the observed variation well. The model only reflects the average relationships between variables and so cannot describe the relevant associations (Ren et al., 2022a). To ensure reliability of the estimate results, we use the spatial Durbin panel estimation method for robustness checks. Models (1) to (3) in Table 8 report the estimate results on the impact of the business environment and human capital structural upgrading on economic development quality. It is shown that the significance level of the independent variables’ coefficient is consistent with models in Table 7, demonstrating the robustness of estimate results shown before. Empirical results reveal that economic development quality’s spatial autoregression coefficient ρ is significantly positive, indicating a positive spatial interaction effect of economic development quality. Regions with relatively high economic development quality often cluster together. In line with the results of the spatial autocorrelation test, the quality of urban economic development is influenced by the economic development quality of neighboring cities. Model (1) shows that the coefficient of human capital structural upgrading is 0.745 and is statistically significant at the 1% level when the business environment is not taken into consideration. This reveals that human capital structural upgrading is beneficial to the elevation of economic development quality. The main explanation is that the share of high-level human capital grows along with the inflow of high-level talents, generating positive results in productivity and technological innovation. Therefore, human capital structural upgrading delivers positive effects on economic development quality. Compared with model (1), model (2) adds empirical results of the business environment’s impact on economic development quality. The coefficient of the business environment is 0.202 and is statistically significant at the 1% level. Put differently, 1% increase in the business environment brings about 0.202% of improvement in economic development quality. This testifies to the positive effect of the business environment on economic development quality. The possible explanation is that a convenient business environment can, to a large extent, lower the entry cost and operation cost, which reduces investment risks and enhances expectations of investment return. Enterprises are encouraged to conduct independent innovation. Such conclusions corroborate the hypothesis proposed previously. Model (3) considers the coordination effect of the business environment and human capital structural upgrading on economic development quality. Coefficients of both the business environment and human capital structural upgrading are significantly positive at the 1% level, meaning that improvement in the business environment and attracting high-level talents are conducive to the elevation of economic development quality. The major reason is that human capital structural upgrading propels technological progress and innovation. The more fierce the competition is, the greater its contribution to the elevation of economic development quality. Hypotheses 1 and 2 are further corroborated.

Based on the verified hypothesis, we investigate the impact of control variables on economic development quality. According to the results in Table 2, the goodness of fit of various models (adjusted R^2 value) is higher than 0.5, showcasing the proper design of models. The significance level of coefficients shows that per capita wealth, innovation input, net migration, railway facility, and openness significantly increase economic development quality, which is consistent with the vast majority of existing studies. But the unemployment rate’s impact on economic development quality is negative, meaning that a high unemployment rate suppresses economic development quality. The higher the unemployment rate is, the lower the possibility of employment will be. This reduces, to some extent, labor migration. Talents or entrepreneurs are less likely to stay, which ultimately affects the technological innovation of enterprises and is detrimental to economic development quality.

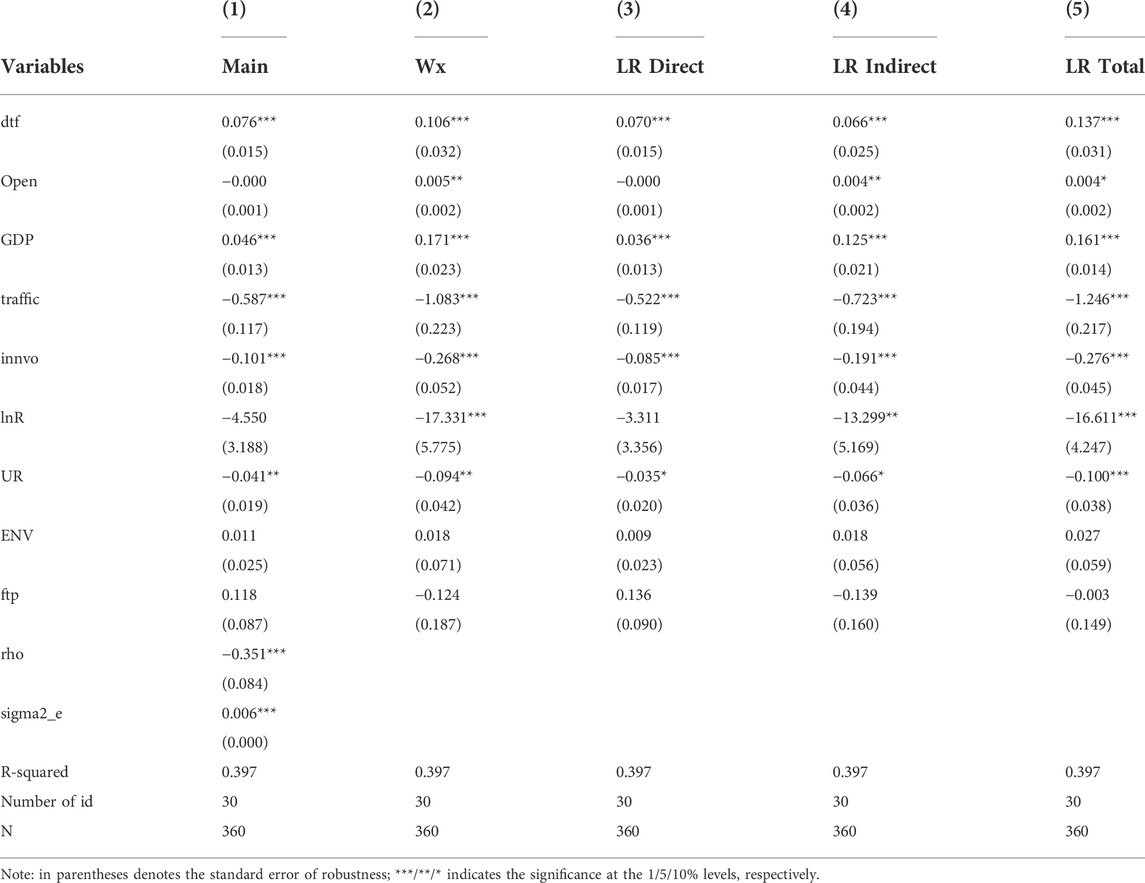

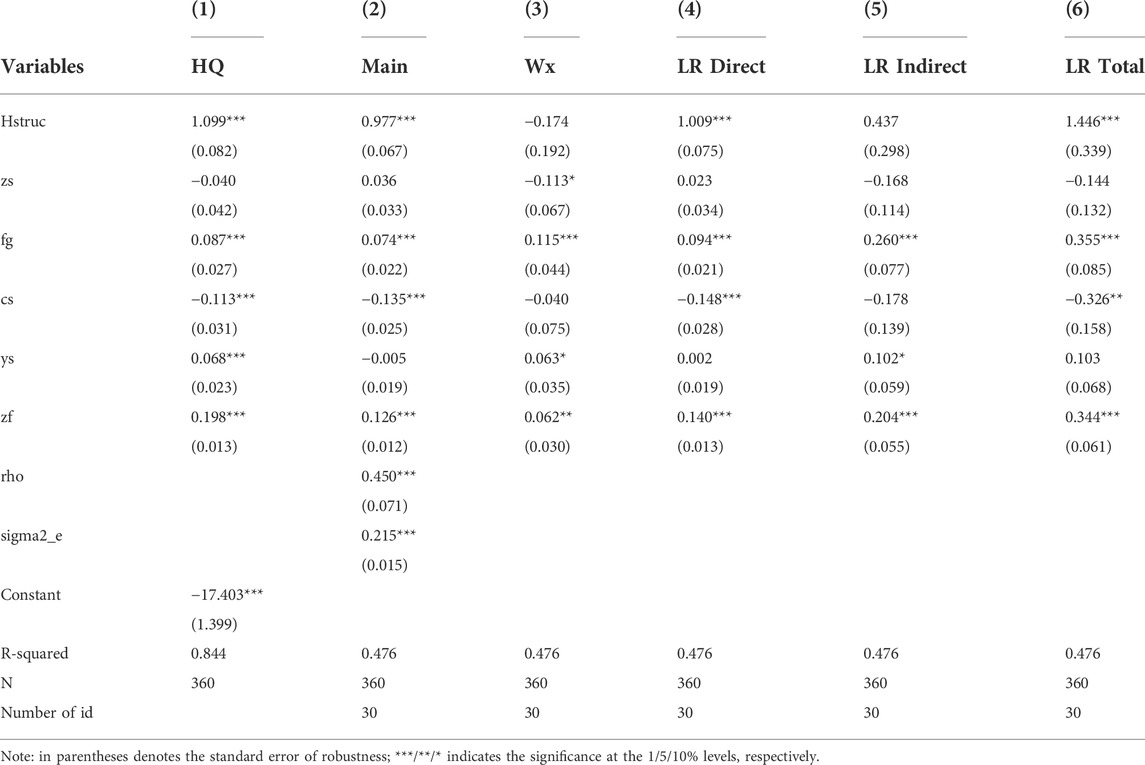

To further examine the impact of the business environment on human capital structural upgrading, this study employs the spatial Durbin model to investigate the relation between these two. The results are shown in Table 9.

Results in Table 9 show that improving the business environment delivers positive impacts on human capital structural upgrading, which is statistically significant. The coefficient of the business environment is 0.076 and is significant at the 1% level. The reason is that a convenient business environment lowers innovation costs and offers better incentive mechanisms and start-up opportunities for enterprises. More high-level and technical talents with innovative ideas are attracted to the region, who propel development driven by innovation and massive start-ups. As a result, economic development quality is improved. Moreover, estimate results of control variables are consistent with those in benchmark regression and are not repeated here for the sake of brevity.

As the spatial autoregression coefficient of economic development quality passes the significance test, regression results cannot directly explain the economic sense of independent variables. Therefore, this study decomposes spatial effects based on point estimation results of the SDM. The results are shown in Table 10.

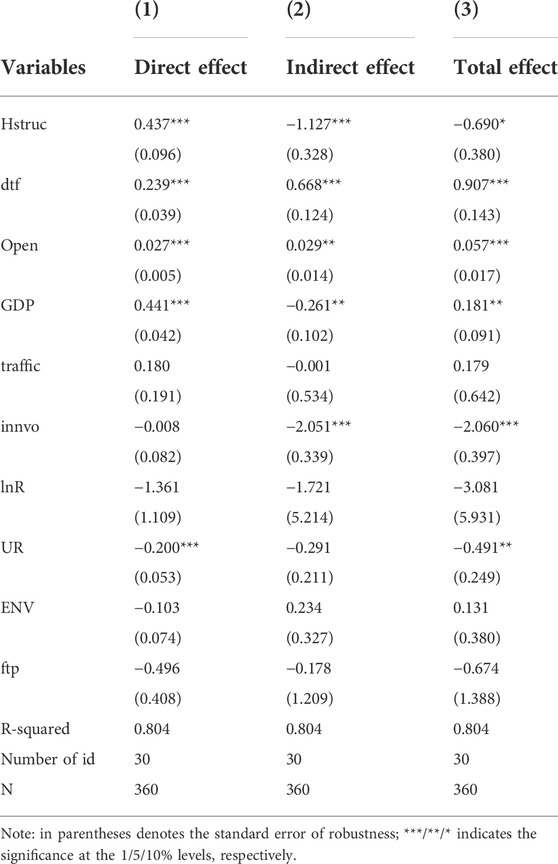

Under the economic distance weight matrix, the direct effect of the business environment and human capital structural upgrading is significantly positive, meaning that business environment improvement and human capital structural upgrading effectively increase the quality of regional economic development. On the one hand, a convenient business environment offers evident advantages in attracting and cultivating high-level talents and enterprises. Through clustering effects and technological spillover effects, favorable business environment enhances product quality and competitiveness, which ultimately increases economic development quality. On the other hand, high-level human capital is the carrier of knowledge, technology, and experience, which is the main driver for technological innovation. As compared with primary human capital, high-level human capital not only realizes technological innovation via “learning by doing” (Romer, 1990) but also engages in emulation and secondary innovation by effectively assimilating international technological spillover (Caselli and Coleman, 2006). Furthermore, human capital possesses a strong externality (Lucas, 1988). High-level human capital with an innovation spirit is more likely to generate new ideas, learn new technologies, and is more capable of technological innovation. Therefore, human capital structural upgrading serves as a solid support for the application, improvement, and innovation of various technologies. Advanced technologies are better assimilated and applied and technological innovation is conducted more efficiently, which leads to the improvement of economic development quality. The indirect effect of the business environment is significantly positive, revealing that business environment improvement delivers obvious and positive spatial spillover effects on economic development quality of neighboring provinces. Improving the business environment helps accelerate technological spillover among provinces and cross-region cooperation. The indirect effect of human capital structural upgrading is significantly negative. An improvement of 1% in human capital structural upgrading leads to a 1.127% decrease in economic development quality in the neighboring area. The possible explanation is that regions with a relatively high-level of human capital structure often enjoy favorable geographical location, preferential policies, and competitive platforms, which easily attract talents (Du et al., 2020). For neighboring provinces, this means brain drain. Therefore, human capital structural upgrading delivers a negative impact on the economic development quality of neighboring areas.

4.4 Endogeneity issues

When analyzing how the business environment and human capital structural upgrading affect economic development quality, endogeneity of the business environment and human capital structural upgrading is not a serious issues. But for the analysis based on benchmark regression on the impact of the business environment and human capital structural upgrading on economic development quality, the endogeneity of the two is an issue of great significance. To be specific, on the one hand, the business environment can improve economic development quality through technological innovation and introduction of FDI while human capital structural upgrading affects economic development quality by attracting and cultivating high-level talents. On the other hand, economic development quality itself influences human capital structural upgrading via the scale effect, technological effect, and structural effect. The development of high-level enterprises may entail improvement of the business environment. That is, a favorable business environment may promote economic growth. But at the same time, an advanced economic level means a higher requirement for a business environment, which urges the government to create better business environments. Replacing key independent variables with suitable instrumental variables is an effective way to alleviate endogeneity. This study refers to typical research such as the research by Acemoglu et al. (2014) and Glaeser et al. (2015) and selects the duration of a foreign trade port and the origin of merchant groups in the Ming and Qing Dynasty as the historical instrumental variable for an urban business environment. In reference to the practice of Dai (2020), we adopt the interaction between the number of higher education institutions (related to individuals’ changes) in the province from the period 2008–2019 and the number of college graduates in China in the previous two periods as the instrumental variable of human capital structural upgrading.

Models 3 and 4 in Table 11 report the second stage estimate results of two-stage least-squares regression on instrumental variables. The RKF statistic value of models is obviously below 32.7888, the critical value of the F value at the 10% level, demonstrating no weak instrumental variable. Moreover, the second stage regression results show that the coefficient of endogenous variable human capital structural upgrading (Hstruc) and the business environment (dtf) experience no evident changes when control variables are added. This testifies that the estimate variable satisfies the exclusion restriction (Burchardi and Hassan, 2013) or the instrumental variable is exogenous. Furthermore, the first stage regression result satisfies the relevant hypothesis of the instrumental variable. Therefore, the selection of instrumental variables in this study is effective. Estimate results of the instrumental variable in model 4 show that there is no obvious difference in direction and significance among coefficients of independent variables in models 1 to 3 of Table 2, which verifies the robustness of the conclusions drawn before.

4.5 Robustness checks

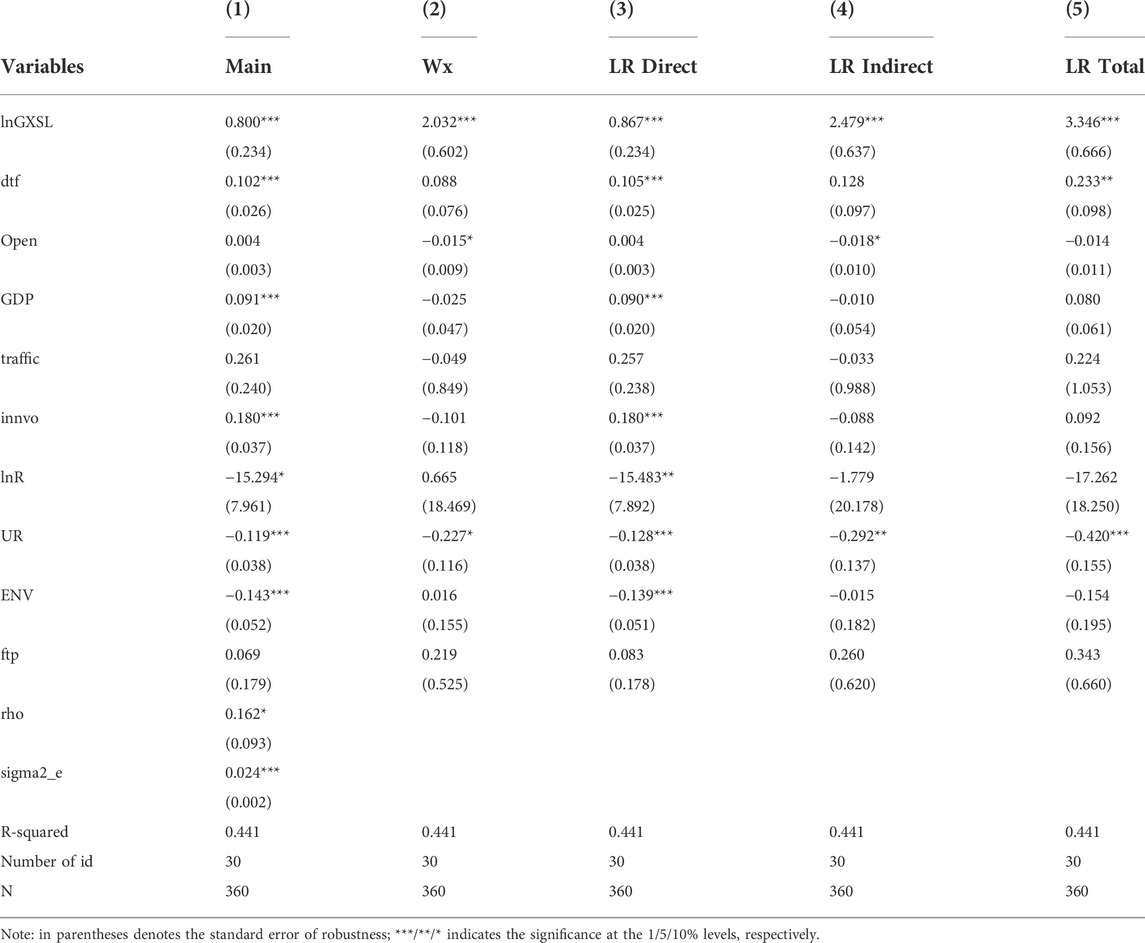

To ensure the comparability of estimate results and reliability of the conclusions of this study, we use the number of higher education institutions (lnGXSL) as the proxy indicator for human capital structural upgrading. The estimate result is shown in Table 12, which is consistent with the benchmark regression conclusion.

This study selects the five dimensions of the marketization index from Marketization Index of China’s Provinces NERI Report 2019, i.e., government–market relation (zs), development of non-state-owned economy (fg), development level of the product market, development level of the factor market (ys), and market intermediary organization development and legal environment (zf) as the proxy indicator for the business environment (dtf). The estimate result is shown in Table 13, which is consistent with the results shown before and corroborates the robustness of previous conclusions. Such results demonstrate that the government should refrain from interfering with the market. Instead, the government should give an active role to the factor market for effective allocation, enhance the rule-of-law environment, and further improve the business environment. In addition, different spatial weights are adopted for tests, the result of which shows no substantial difference from the benchmark model and remains robust.

In addition, to avoid biased regression results due to the choice of spatial weights, the Durbin model is retested based on geographic distance spatial weights and the regression results are shown in Table 14. Compared with the estimated results of economic distance spatial weights (Table 8), it is found that the significance level, direction, and size changes of the effects of the advanced human capital structure and business environment on economic development quality are not significant. It indicates that the setting of spatial weights did not lead to biased model estimation results and also proves the robustness of the previous findings.

5 Further analysis

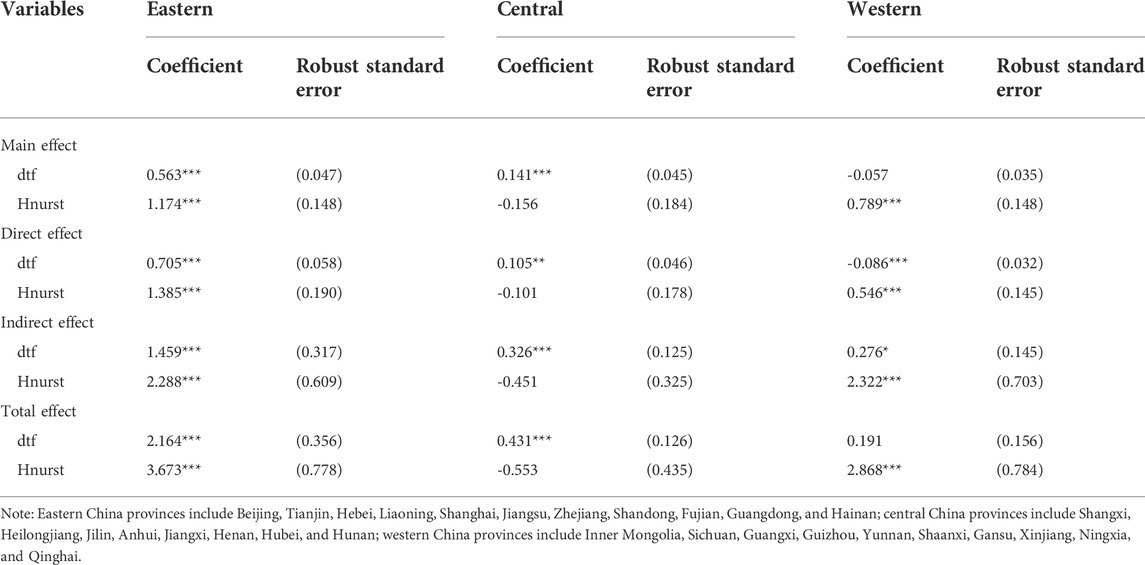

5.1 Region heterogeneity

Due to differences in natural endowment and economic development among varied regions of China, regional variance among eastern, central, and western China is significant. To examine regional heterogeneity of the impact of the business environment and human capital structural upgrading on economic development quality, this study refers to the study by Ding et al. (2021)and groups samples into eastern, central, and western regions. Further test results are shown in Table 15. The empirical result shows that a 1% improvement in the business environment directly leads economic development quality in eastern regions to grow by 0.563%. But the impact of business environment improvement on economic development quality is not significant with its estimate coefficient being -0.057. The reason is that economy is less developed in western China. Relatively weak administration and a rule-of-law environment and slow progress in the business environment generate little positive impact on economic development quality. But in terms of spatial spillover effects, business environment improvement delivers evident and positive spillover effects on neighboring areas. However, the eastern region accumulates lots of capital and technology over a sustained period of economic development. Urban construction and government administration levels are better than the rest of the country. Growing environmental awareness of residents and industrial structural upgrading also prominently improve economic development quality in the eastern region. Moreover, at the regional level, the impact of human capital structural upgrading on economic development quality is evidently different among varied regions. In the eastern region, the coefficient of human capital structural upgrading is 1.174 and is statistically significant at the 1% level; in the central region, the coefficient is -0.156 and is not significant; in the western region, the coefficient is 0.789 and is significant at the 1% level. This demonstrates that human capital structural upgrading in the eastern and western regions delivers significantly positive impact on business environment quality with the impact of the former stronger than that of the latter. Based on the regression coefficient of the central region, human capital structural upgrading in the central region suppresses economic development quality. But such impacts are not statistically significant. This may be explained by the mismatch between the human capital structure and industrial structure in the central region. Only when the human capital structure matches the economic structure and social structure can it maximize its role (Adil et al., 2014). Put differently, a higher level of human capital structure does not necessarily mean better effects. Instead, there is an optimal state of human capital structure (Jun and Mingfeng, 2019). When the human capital structure upgrades to a state where human capital exceeds the demand required by the economic structure, the excess high-level human capital leads to internal competition and results in issues such as industrial mismatch. In such a case, human capital structural upgrading is detrimental to improvement in productivity and economic development quality. Furthermore, a mismatch between human capital and economic structure generates crowd-out effects, which entails higher levels of unemployment and imbalance in the labor market (Čadil et al., 2014a). Therefore, human capital structural upgrading does not improve economic development quality in the central region. This also suggests that the central region should, while improving economic development quality, optimize the human capital structure to make it better match with the industrial structure to unleash human capital structural upgrading’s positive effects on economic development quality.

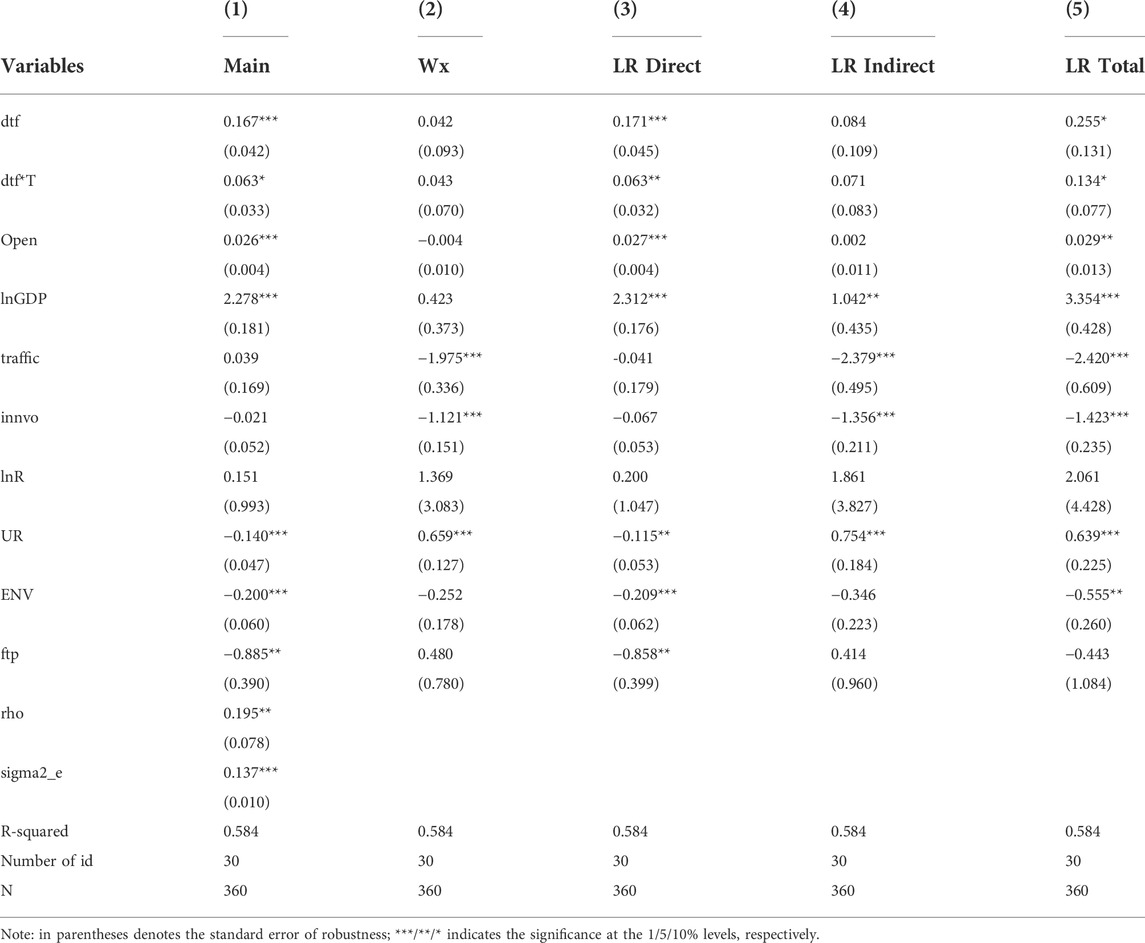

5.3 Period heterogeneity

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the business environment has been high on the government’s agenda. The impact of business environment improvement on economic development quality may be varied before and after the 18th National Party Congress. To verify such potential variance caused by the period, we introduce the dummy variables of time T, which investigates whether there is a difference in the business environment’s impact before and after the 18th National Party Congress. T = 0 for the period before the Congress (2008–2012); T = 1 for the period after the Congress (2012–2019).

The model in Table 16 introduces the product term T*dtf. The result shows that the estimate coefficient of T*dtf is significantly positive at 0.063, demonstrating significant differences in the business environment’s impact before and after the 18th National Party Congress. That is, the positive impact of the business environment on economic development quality becomes stronger after the 18th National Party Congress. The possible explanation is that improving the business environment was highlighted by the Congress. Local governments are motivated to create a favorable business environment and lay a solid foundation for improving economic development quality.

5.3 Quantile regression

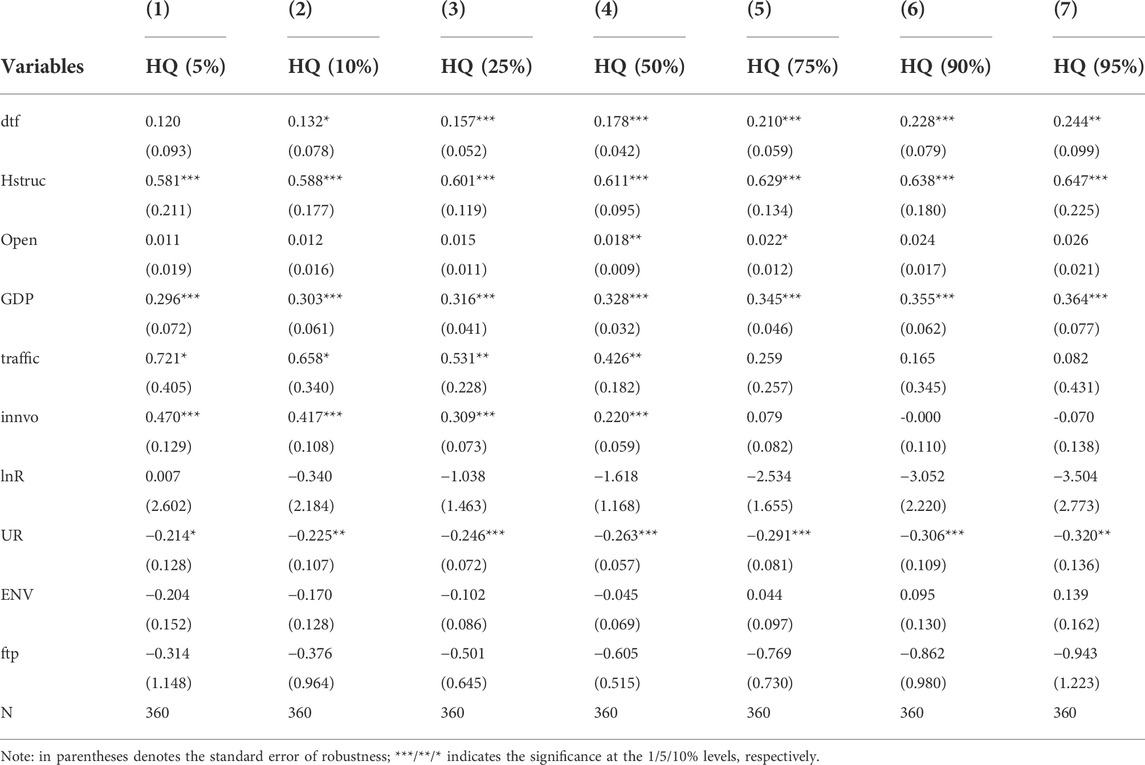

For the aforementioned reasons, considering that there are significant differences between different regions, to further verify whether the impact of the business environment and advanced human capital structure on the quality of economic development is heterogeneous, this study introduces the quantile method for regression (Cheng C et al., 2021; Ren et al., 2022c). A panel data quantile regression model can analyze different marginal utilities of the business environment and human capital structural upgrading on economic development quality at varied quantile points (Koenker, 2004; Ren et al., 2022b). In reference to the common practice in previous research, we select the most representative seven quantile points (5, 10, 25, 75, 90, and 95%) for analysis. To be consistent with previous estimations in terms of methodology, we adopt the quantile method with a panel fixed effect for estimation, the result of which is shown in Table 17.

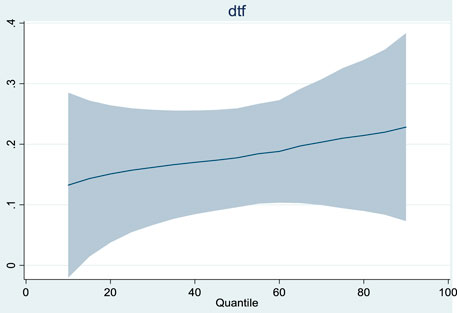

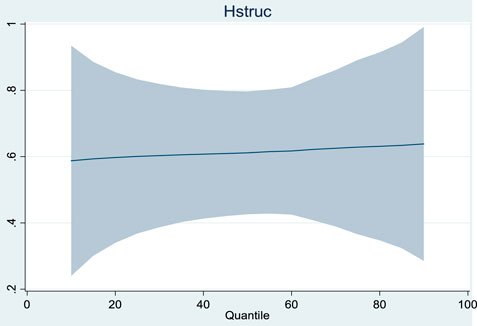

Estimate results in Table 17 show that the business environment and human capital structural upgrading deliver significantly different impacts on economic development quality at varied quantile points. At the quantile of economic development quality, the coefficient of the business environment is not significant. From a lower to higher quantile of economic development quality, its coefficient showcases an increasing trend. Meanwhile, the coefficient of human capital structural upgrading’s impact on economic development quality is 0.581, 0.588, 0.601, 0.611, 0.629, 0.638, and 0.647, respectively, at the quantile point of 0.05, 0.10, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 0.90, and 0.95. This shows that at different economic development stages, human capital structural upgrading positively and significantly affects economic development quality. As the quantile point moves up, the positive impact of human capital structural upgrading becomes stronger. At the quantile point of 0.95, the coefficient of human capital structural upgrading is the highest, meaning that its marginal contribution is the highest. The reason is that regions with high economic development quality enjoy stronger advantages in human capital stock and structure, which deliver greater positive impacts on technological innovation and industrial structural upgrading. Its coefficient also grows gradually. This is in line with the general trend in China that high-level human capital gradually flows to economically advanced regions and economic development quality in the country improves over time. Such results also corroborate the test results on the eastern, central, and western regions as shown in Figures 2, 3.

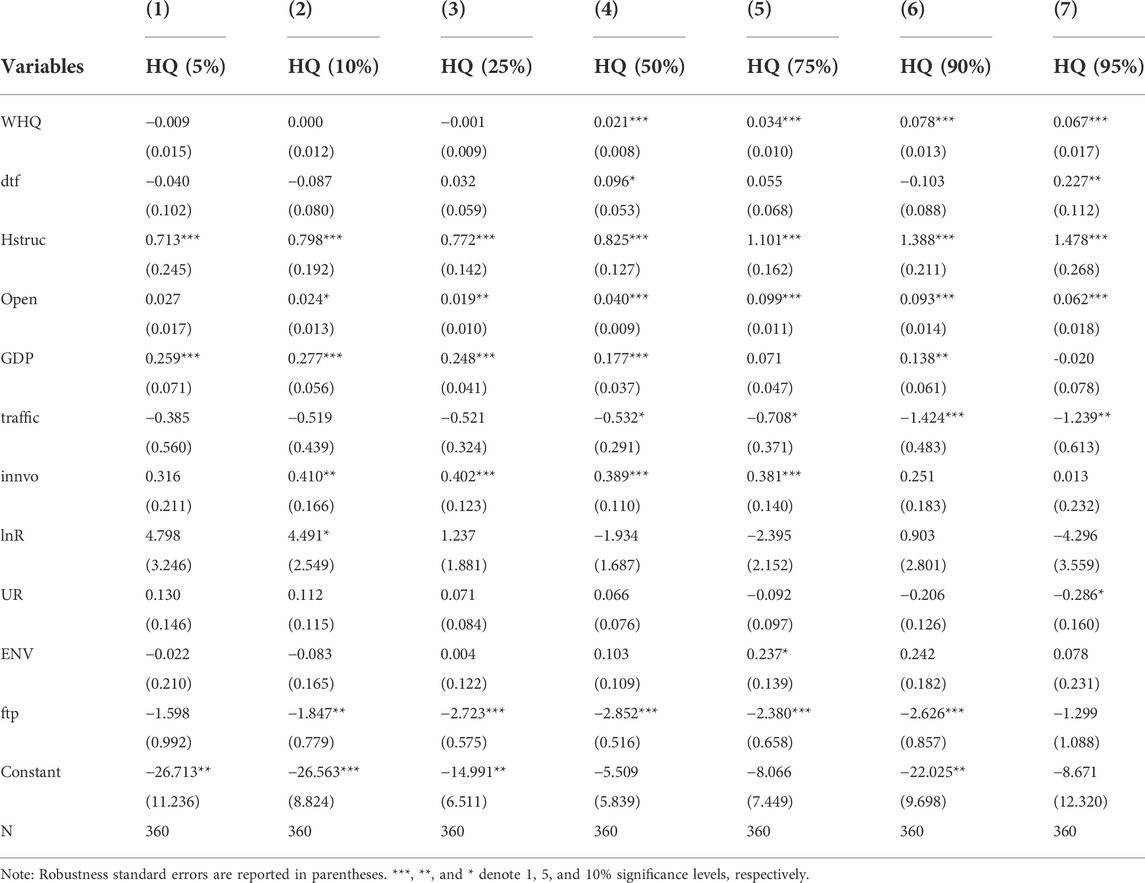

The result of the spatial quantile method is shown in Table 18. According to the first law of geography, the quality of economic development has a strong spatial dependence, but the quantile regression model has not yet considered this spatial autocorrelation. The spatial quantile model can more comprehensively portray the distribution characteristics and spatial correlation of the quality of economic development. In this study, the instrumental variable quantile regression (IVQR) method is used for estimation. The spatial quantile estimation results in Table 18 further show the existence of a significant and positive spatial autocorrelation of economic development quality, which passed the 1% significance level test. Moreover, the spatial correlation of economic development quality differs across quartiles, and the spatial autocorrelation of high economic development quality is stronger than that of low economic development quality. Meanwhile, the business environment and advanced human capital structure show a positive correlation on the economic development level, but the coefficients differ with different quartiles, indicating that the intensity of reliance on advanced human capital structure and business environment is not the same at different economic development stages. The reason for this is that in provinces with lower levels of economic development, optimizing the business environment will increase a lot of construction costs, when the cost benefit of the business environment is greater than the promotion effect, and for provinces with higher levels of economic development, their own business environment system has been relatively perfect, so the reliance on business environment optimization is not very strong. Talent is the key factor of economic development; the higher the level of economic development, the stronger the reliance on the advanced human capital structure. From the side, it is further verified that the improvement of the advanced level of the human capital structure has a significant promoting effect on the quality of economic development, and this promoting effect shows a gradual increasing trend as the position of the economic quality development quantile rises.

6 Conclusion and policy implications

To study the dependence of the quality of China’s economic development on the business environment and the advanced structure of human capital, based on theoretical analysis on the impact mechanism through which the business environment and human capital structural upgrading influence economic development quality, this study employs the panel data of 30 Chinese provinces for the period from 2008–2019, measures provincial economic development quality via the VHSD–EM model, and tests the trilateral relation and impact mechanism through the spatial panel Durbin model and quantile regression model. We further examine the regional heterogeneity of the impact of the business environment and human capital structural upgrading on economic development quality and investigate whether the emphasis on improving the business environment on the 18th National Party Congress affects economic development quality of the regions. We find that 1) business environment improvement promotes human capital structural upgrading and economic development quality. Human capital structural upgrading delivers significant intermediary effects, through which business environment improvement affects economic development quality; 2) in terms of region, there is evident heterogeneity in the impact of the business environment and human capital structural upgrading in the eastern, central, and western regions. The positive impact of the business environment on economic development quality is the most prominent in the eastern region, followed by that in the central region. The business environment’s impact on the western region is not statistically significant. Human capital structural upgrading significantly promotes economic development quality in the eastern and western regions but suppresses economic development quality in the central region in a statistically non-significant sense. This indicates that the central region needs to strengthen the optimization of the business environment, and the western region should pay more attention to the improvement of the advanced level of human capital structure. The eastern region should strengthen the enhancement of the advanced level of the human capital structure while optimizing the business environment; 3) the quantile regression estimate result reveals that the promotion effect of the business environment and advanced human capital structure on the quality of economic development shows an overall upward trend at different quartiles, and its promotion effect has obvious heterogeneity and asymmetry among quartiles. This indicates the heterogeneity in the intensity of the reliance on the advanced human capital structure and business environment at different stages of economic development; 4) the time heterogeneity of the business environment’s impact on economic development quality demonstrates that business environment improvement further elevates economic development quality since the 18th National Party Congress when the business environment was highlighted.

Based on the aforementioned conclusions, we propose the following policy suggestions: first, to further improve economic development quality of provinces, local governments should deepen reforms to delegate power to the government at lower levels, better administration, and improve government services to improve the business environment. Based on local conditions and advantages, local governments should formulate talent development policies and enhance systematic and institutional arrangements related to human capital investment. By adjusting and guiding the flow of human capital, local governments can galvanize human capital structural upgrading. Second, policymakers should take full account of regional differences when formulating economic policies. The country should steadily improve the business environment and human capital structure in the eastern region while stepping up efforts in elevating the business environment and channeling more inputs into human capital in the central and western regions to the narrow regional development gap. Third, as regional economic development is affected by policies and structural differences of neighboring provinces, the local government should develop new methods for synergy in regional economic development, invent mechanisms for benefit coordination and win-win results, and construct a cross-regional coordination system for economic development quality monitoring. At last, the reform of the sub-provincial fiscal system in China is an important aspect of promoting China’s economic development in the future. Promoting the reform of the sub-provincial fiscal system is conducive to optimizing the allocation of financial resources and relieving the pressure on financial resources at the grassroots level (Kassouri, 2022), and strengthening the capacity to guarantee public services at the grassroots level and promoting the equalization of public services, thereby promoting high-quality economic development. This provides ideas and directions for further research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Files; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, SH and HY; methodology, SH and HY; data curation, SH and HY; writing—original draft preparation, SH and HY; writing—review and editing, SH and HY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71973041) and the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (19YJA790026).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acemoglu, D., Gallego, F., and Robinson, J. A. (2014). Institutions, human capital and development[R]. Massachusetts United States: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Acemoglu, D. (2003). Patterns of skill premia. Rev. Econ. Stud. 70 (2), 199–230. [J]. $230. doi:10.1111/1467-937x.00242

Alesina, A., Hems, L. C., and Chinnock, K. (1998). The political economy of high and low growth[C]//Annual World Bank Conference. Dev. Econ. 1997, 217–237.

Anselin, L. (1995). Local indicators of spatial association-LISA. Geogr. Anal. 27 (2), 93–115. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4632.1995.tb00338.x

Balsmeier, B., and Czarnitzki, D. (2017). Ownership concentration, institutional development and firm performance in central and eastern europe. MDE. Manage. Decis. Econ. 38 (2), 178–192. doi:10.1002/mde.2751

Čadil, J., Petkovová, L., and Blatná, D. (2014a). Human capital, economic structure and growth. Procedia Econ. finance 12, 85–92. doi:10.1016/s2212-5671(14)00323-2

Čadil, J., Petkovová, L., and Blatná, D. (2014b). Human capital, economic structure and growth. Procedia Econ. finance 12, 85–92. doi:10.1016/s2212-5671(14)00323-2

Caselli, F., and Coleman, W. J. (2006). The World technology frontier. Am. Econ. Rev. 96 (3), 499–522. doi:10.1257/aer.96.3.499

Chen, J., He, Y., and Zhan, H. (2021). Measurement of the impact of advanced human capital structure on industrial structural change[J]. Statistics Decis. Mak. 37 (02), 80–83.

Cheng, B. S., and Hsu, R. C. (1997). Human capital and economic growth in Japan: An application of time series analysis. Appl. Econ. Lett. 4 (6), 393–395. doi:10.1080/135048597355375

Cheng, C., Ren, X., Dong, K., and Wang, Z. (2021). How does technological innovation mitigate CO2 emissions in OECD countries? Heterogeneous analysis using panel quantile regression[J]. J. Environ. Manag. 280, 111818. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111818

De Haan, J., and Sturm, J. E. (2000). On the relationship between economic freedom and economic growth. Eur. J. political Econ. 16 (2), 215–241. doi:10.1016/s0176-2680(99)00065-8

Ding, C., Liu, C., Zheng, C., and Li, F. (2021). Digital economy, technological innovation and high-quality economic development: Based on spatial effect and mediation effect. Sustainability 14 (1), 216. doi:10.3390/su14010216

Dreher, A., and Gassebner, M. (2013). Greasing the wheels? The impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry[J]. Public Choice 155 (3), 413–432. doi:10.1007/s11127-011-9871-2

Du, D., Pang, Q., and Wu, Y. (2015). Modern comprehensive e-valuation method and case selection. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press. the 3rd Edition.

Du, J., Zhang, J., and Li, X. (2020). What is the mechanism of resource dependence and high-quality economic development? An empirical test from China[J]. Sustainability 12 (19), 8144. doi:10.3390/su12198144

Easton, S. T., and Walker, M. A. (1997). Income, growth, and economic freedom[J]. Am. Econ. Rev. 87 (2), 328–332.

Economou, F. (2019). Economic freedom and asymmetric crisis effects on FDI inflows: The case of four South European economies. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 49, 114–126. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.02.011

Fleisher, B., Li, H., and Zhao, M. Q. (2010). Human capital, economic growth, and regional inequality in China. J. Dev. Econ. 92 (2), 215–231. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2009.01.010

Fredriksson, P. G., and Millimet, D. L. (2002). Strategic interaction and the determination of environmental policy across U.S. States. J. urban Econ. 51 (1), 101–122. doi:10.1006/juec.2001.2239

Gillanders, R., and Whelan, K. (2014). Open for business? Institutions, business environment and economic development[J]. Kyklos 67 (4), 535–558. doi:10.1111/kykl.12067

Glaeser, E. L., Kerr, S. P., and Kerr, W. R. (2015). Entrepreneurship and urban growth: An empirical assessment with historical mines. Rev. Econ. Statistics 97 (2), 498–520. doi:10.1162/rest_a_00456

Goedhuys, M., and Veugelers, R. (2012). Innovation strategies, process and product innovations and growth: Firm-level evidence from Brazil. Struct. change Econ. Dyn. 23 (4), 516–529. doi:10.1016/j.strueco.2011.01.004

Gogokhia, T., and Berulava, G. (2021). Business environment reforms, innovation and firm productivity in transition economies. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 11 (2), 221–245. doi:10.1007/s40821-020-00167-5

Gu, G, Guo, A, and Wen, Y (2013). A study on the dual effect of institutions on human capital dividend[J]. China Popul. Sci. 3, 65–75.

He, S., Yao, H., and Ji, Z. (2021). Direct and indirect effects of business environment on BRI countries’ global value chain upgrading. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (23), 12492. doi:10.3390/ijerph182312492

Jun, F., and Mingfeng, L. (2019). Human capital structure and economic growth: From the perspective of new structural economics[J]. China Econ. 14 (6), 36–55.

Kassouri, Y. (2022). Fiscal decentralization and public budgets for energy RD&D: A race to the bottom?[J]. Energy Policy 161, 112761. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112761

Koenker, R. (2004). Quantile regression for longitudinal data. J. Multivar. Analysis 91 (1), 74–89. doi:10.1016/j.jmva.2004.05.006

Kui-chao, D., Li, X., and Luo, Z. (2020). Advanced human capital structure, factor market development and structural upgrading of service industry. [J]. Finance Trade Econ. 10, 129–14.

Fabová, Ľ, and Janáková, H. (2015). Impact of the business environment on development of innovation in Slovak Republic[J]. Procedia Econ. Finance 34, 66–72. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01602-0

Lazear, E. P. (2004). Balanced skills and entrepreneurship. Am. Econ. Rev. 94 (2), 208–211. doi:10.1257/0002828041301425

Li, J., and Nan, Y. (2019). Decision-making under human capital mismatch: Prioritizing innovation drive or industrial upgrading? [J]. Econ. Res. 54 (08), 152–166.

Li, X., Zhou, W., and Hou, J. (2021). Research on the impact of OFDI on the home country's global value chain upgrading. Int. Rev. Financial Analysis 77, 101862. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101862

Liu, C, and Xia, J. Commercial system reform human capital and entrepreneurial choice [J]. Finance Trade Econ. 2021 (8), 113–128.

Liu, Z., Li, H., Hu, F., and Li, C. (2018). Advanced human capital structure and economic growth-also on the formation and reduction of the gap between the east, middle and west regions[J]. Econ. Res. 53 (03), 50–63.

Lopez, R., Thomas, V., and Wang, Y. (1998). Addresing the education puzzle: The distribution of education and economic reform[J]. Policy Res. Work. Pap. Ser. 2, 1–31. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-2031

Lucas, R. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. J. monetary Econ. 22 (1), 3–42. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

Ma, R, Luo, H, and Wang, H, (2019). Research on the evaluation index system and measurement of high-quality development of China’s regional economy [J]. China Soft Sci. 7, 60–67.

Musibau, H. O., Yusuf, A. H., and Gold, K. L. (2019). Endogenous specification of foreign capital inflows, human capital development and economic growth: A study of pool mean group[J]. Int. J. Soc. Econ 3, 454–472. doi:10.1108/IJSE-04-2018-0168

Nelson, M. A., and Singh, R. D. (1998). Democracy, economic freedom, fiscal policy, and growth in LDCs: A fresh look. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 46 (4), 677–696. doi:10.1086/452369

Park, J. (2006). Dispersion of human capital and economic growth. J. Macroecon. 28 (3), 520–539. doi:10.1016/j.jmacro.2004.09.004

Ren, X., Cheng, C., Wang, Z., and Yan, C. (2021). Spillover and dynamic effects of energy transition and economic growth on carbon dioxide emissions for the European union: A dynamic spatial panel model. Sustain. Dev. 29 (1), 228–242. doi:10.1002/sd.2144

Ren, X., Li, Y., Wen, F., and Lu, Z. (2022a). The interrelationship between the carbon market and the green bonds market: Evidence from wavelet quantile-on-quantile method. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 179, 121611. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121611

Ren, X., Tong, Z., Sun, X., and Yan, C. (2022b). Dynamic impacts of energy consumption on economic growth in China: Evidence from a non-parametric panel data model. Energy Econ. 107, 105855. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105855

Ren, X., Wang, R., Duan, K., and Chen, J. (2022c). Dynamics of the sheltering role of bitcoin against crude oil market crash with varying severity of the COVID-19: A comparison with gold. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 62, 101672. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2022.101672

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. J. political Econ. 98 (2), S71–S102. doi:10.1086/261725

Romer, P. M. (1989). Human capital and growth: Theory and evidence[J]. Carnegie-Rochester Conf. Ser. Public Policy 32, 251–286. doi:10.1016/0167-2231(90)90028-J

Sharifazadeh, M., and Ziyari, R. (2012). The study of the dual effects of institutional environment on economic growth[J]. Iran. J. Appl. Econ. 3, 1–37.

Škare, M., and Lacmanović, S. (2015). Human capital and economic growth: A review essay[J]. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 17 (39), 735–760.

Tang, X, Wang, Y, and Tang, X (2020). Research on the evaluation of high-quality economic development of Chinese provinces [J]. Sci. Res. Manag. 41 (11), 44–55.

Teixeira, A. A. C., and Queirós, A. S. S. (2016). Economic growth, human capital and structural change: A dynamic panel data analysis. Res. policy 45 (8), 1636–1648. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2016.04.006

Tsaurai, K., and Ndou, A. (2019). Infrastructure, human capital development and economic growth in transitional countries. Comp. Econ. Res. Central East. Eur. 22 (1), 33–52. [J]. doi:10.2478/cer-2019-0003

Wooldridge, J. M. (2015). Control function methods in applied econometrics. J. Hum. Resour. 50 (2), 420–445. doi:10.3368/jhr.50.2.420

Xu-Ming, Shangguan (2018). Spatial heterogeneity in the context of technological multidimensional spillover, absorptive capacity and technological progress" J1 . Sci. Technol. Manag. 4, 74–87.

Keywords: business environment, human capital structure upgrading, economic development quality, spatial durbin model (SDM), China

Citation: He S and Yao H (2022) Business environment, human capital structural upgrading, and economic development quality. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:964922. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.964922

Received: 09 June 2022; Accepted: 25 August 2022;

Published: 30 September 2022.

Edited by:

Faik Bilgili, Erciyes University, TurkeyReviewed by:

Rahim Alhamzawi, University of Al-Qadisiyah, IraqYacouba Kassouri, Leipzig University, Germany

Xiaohang Ren, Central South University, China

Copyright © 2022 He and Yao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huilin Yao, MTkwMTE1MDEwMDAyQG1haWwuaG51c3QuZWR1LmNu

Shengbing He

Shengbing He Huilin Yao

Huilin Yao