- 1School of Economics and Management, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, China

- 2School of Social Audit, Nanjing Audit University, Nanjing, China

- 3Business School, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance (D&O insurance), an important tool for diversifying and transferring risks of managers, plays a crucial role in corporate investment decisions, including corporate environmental investment decisions. However, the relationship between D&O insurance and corporate environmental investment remains unknown. Using a sample of Chinese listed firms, this study examines whether and how D&O insurance affects corporate environmental investment from 2008 to 2019. We find that D&O insurance is negatively associated with corporate environmental investment. This result is consistent with the results of a series of robustness tests. Further analyses show that D&O insurance impedes corporate environmental investment by driving executives to seek private benefits, especially monetary benefits. Moreover, the negative effect of D&O insurance on corporate environmental investment is more pronounced in low-polluting and highly competitive industries. However, this negative relationship is mitigated by political connections. The findings contribute to the literature by providing empirical evidence of the involvement of D&O insurance in influencing corporate environmental investment decisions.

1 Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid economic development in China, environmental problems have become more prominent (Tang et al., 2013; Yan and Xu, 2020). In 2002, the United Nations released the China Human Development Report, which pointed out that environmental pollution in China caused an annual GDP loss of approximately 3.5%–8%, and that more than 80% of the environmental pollution in China arises from the corporate sector (Shen et al., 2012). Owing to the deterioration of the ecological environment, the Chinese government increasingly values environmental protection, actively participates in green practices, and proposes and implements a series of goals and policies for green production and low-carbon emissions. In practice, according to the statistics of Tian et al. (2022), the Chinese government has invested 40.51 billion USD in the energy sector, of which 67.66% has been invested in green and clean energy. Regarding policies, in 2008, the guidelines for the disclosure of environmental information for companies listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange required heavily polluting industries to publish information on their environmental performance. In 2015, the Chinese government implemented strict corporate environmental regulations, imposing fines and even imprisonment on companies that violated the law. In September 2020, President Xi Jinping proposed the climate action targets of “2030 Carbon Peak, 2060 Carbon Neutral” at the United Nations General Assembly. He also proposed the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China and the Outline of Vision 2035, both of which included accelerating green and low-carbon development as a crucial objective and task. This further establishes the importance of green development in the new era of China’s development.

Despite the aforementioned regulations and government initiatives established for corporate environmental responsibility, China still faces environmental governance problems. For example, environmental investment is dominated by the government, and the level of corporate environmental investment is relatively low (Claessens et al., 2000), and this type of investment is mostly motivated by legal requirements or gaining a competitive advantage (Maggioni and Santangelo, 2017). However, according to the “who pollutes, who controls; who exploits, who protects” principle established by China’s New Environmental Protection Law and the “polluter pays” principle advocated by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), enterprises, which are the main consumers of natural resources and the main producers of environmental pollution, should bear the primary responsibility of environmental protection and increasing green investment (Tang et al., 2013).

D&O insurance is a type of liability insurance purchased by a company to protect all directors and managers against certain losses from lawsuits arising from poor management decisions and other wrongful acts in that capacity (Yuan et al., 2016). Existing studies have widely investigated the economic consequences of D&O insurance. However, two opposing views remain. One view is that D&O insurance can provide protection for directors and officers from the threat of litigation and reduce their concerns about the performance of their duties, thereby reducing agency costs (Hoyt and Khang, 2000), encouraging firm innovation (Wang et al., 2020), increasing firm value (Hwang and Kim, 2018), and conveying information about the corporate governance of the insured firm (Chen, 2016). Another view is that D&O insurance weakens the disciplinary effect of shareholder lawsuits, which could drive firms to make economic overinvestments (Li and Liao, 2014) and inefficient mergers and acquisitions (Lin et al., 2011) and lead to aggressive earning management (Boyer and Tennyson, 2015).

As an important tool to diversify and transfer risks of managers, D&O insurance plays a crucial role in corporate investment decisions, including corporate environmental investment decisions. The purpose of the study was to examine whether and how D&O insurance affects corporate environmental investment. In theory, D&O insurance also has a two-fold impact on corporate environmental investment. On the one hand, D&O insurance can increase the incentive for directors and officers to act in the interests of their stakeholders, thus promoting corporate environmental investment; on the other hand, D&O insurance can reinforce moral hazard and induce executives to seek private benefits, thereby impeding corporate environmental investment. Consequently, what is the effect of D&O insurance on corporate environmental investment? What are the influencing mechanisms through which D&O insurance affects corporate environmental investment? Does the effect vary among different industries? Whether the effect is influenced by the moderating effect of political connections? To answer the aforementioned questions, we conduct our research based on the data of A-share listed companies in China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2008 to 2019. We find that D&O insurance is negatively associated with the corporate environmental investment. The intermediary mechanism suggests that D&O insurance impedes corporate environmental investment by prompting executives to seek monetary private benefits. Further analyses show that the negative impact of D&O insurance on corporate environmental investment is more pronounced in low-polluting and highly competitive industries, but the negative relationship is mitigated by political connections.

This study makes several contributions to the literature. (1) We expand the literature on corporate environmental investment from the perspective of D&O insurance and executives seeking private benefits. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the impact of D&O insurance on corporate environmental investment, by identifying new factors affecting the investment, thus enriching the literature on this type of investment. (2) We also contribute to the literature on the environmental and economic consequences of D&O insurance. Although the economic consequences of D&O insurance have been widely examined, there is no unanimous conclusion on the role of D&O insurance in corporate governance, and it is impossible to understand the environmental consequences of D&O insurance. This study sheds light on the effectiveness of D&O insurance on corporate governance and further enriches the literature on its consequences. (3) We also show that government connections have a significant impact on the relationship between D&O insurance and corporate environmental investment, thereby providing important empirical evidence for government regulators to formulate environmental policies.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows: Section 2 provides the background of D&O insurance and proposes hypotheses. Section 3 refers to the research design. Section 4 represents empirical results. Section 5 provides the intermediary mechanism tests, heterogeneity analyses, and moderating effect tests. Finally, Section 6 gives conclusions and policy suggestions.

2 Background and hypotheses development

2.1 Background

In the early 1930s, the collapse of the U.S. stock market evoked strong demand from investors for a better regulatory system for the security market. With the establishment of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the sanctioning of the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the business risks borne by directors and officers of US listed companies increased abruptly. As a result, Lloyd’s of London introduced D&O insurance in 1934. Subsequently, D&O insurance gradually gained popularity in the security industry and became an important business for insurance companies in developed countries and regions. The percentage of D&O insurance coverage exceeds 70% (Zou et al., 2008; Yuan et al., 2016).

D&O insurance was introduced relatively late in China. In 2001, China first formulated regulations related to D&O insurance, namely, the Guidance on the Establishment of Independent Directors in Listed Companies, stating that listed companies may establish a D&O insurance system to reduce the risks incurred by directors and officers in the normal performance of their duties. In 2002, the Code of Governance for Listed Companies mentioned that listed companies could purchase D&O insurance for directors if it was approved in the shareholders’ meeting. In the same year, Ping An Insurance and the American Chubb Company jointly provided an insurance policy for Wang Shi, Chairman of Vanke, and this was a prelude to D&O insurance in China.

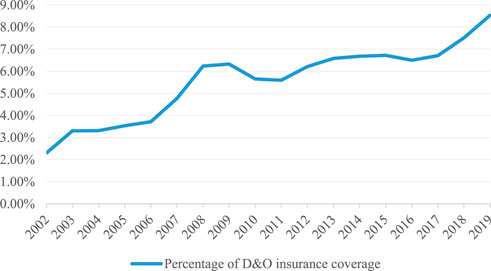

Figure 1 depicts the number of Chinese listed firms that purchased D&O insurance divided by the total number of listed firms from 2002 to 2019. As shown in Figure 1, the percentage of D&O insurance coverage in China increased from 2.30% in 2002 to 8.53% in 2019. Although the percentage of D&O insurance in China has been rising annually, it is still relatively low. However, with the improvement of the legal system of the capital market and the enhancement of risk awareness of listed companies and investors, the role of D&O insurance has become increasingly prominent, and an increasing number of listed companies have realized the importance of D&O insurance and acquired it. Furthermore, there is still scope for the development of D&O insurance in China, and it is important to study the consequences of D&O insurance.

2.2 Hypothesis development

Environmental investment refers to a range of practices by companies aimed at reducing the direct or indirect environmental impact of organizational processes and products or services, including environmental remediation costs, pollution prevention costs, R&D investment costs to address environmental challenges or environmental product development, recovery costs, and costs to implement environmental management systems (Orsato, 2006; Bhuiyan et al., 2021).

Prior studies have examined the determinants of environmental investment, including environmental regulation (Maxwell and Decker, 2006; Chang et al., 2021), political connection (Yan and Xu, 2020), financial constraints (Zhang et al., 2019), the controlling shareholder–manager collusion (Li et al., 2019), managerial strategy (Costa‐Campi et al., 2017), characteristics of CEOs (Li et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2019), independent directors, especially women directors (Bhuiyan et al., 2021; Atif et al., 2020), consumers’ who are environmentally conscious (Liu and Wu, 2009), and works councils (Askildsen et al., 2006). However, the relationship between D&O insurance and corporate environmental investment remains unknown.

Theoretically, D&O insurance may have two effects on corporate environmental investment. On the one hand, D&O insurance may impede corporate environmental investment. The agency theory suggests that shareholders, as principals, are owners of corporate resources, and managers, as agents, are users and controllers of corporate resources. When the interests of managers conflict with those of shareholders and this is coupled with information asymmetry, managers have an incentive to act according to their interests that is difficult for shareholders to detect, thereby leading to principal–agent problems. However, the existence of D&O insurance may exacerbate these issues. D&O insurance enables the insured to shift liability to the insurance company for damages arising from negligence or misconduct in the performance of their duties, which can easily make the insured ignore the cost of their liability for damage. This not only weakens the disciplinary effect of shareholder lawsuits but also reduces the cost of rent-seeking for executives, resulting in managers being more likely to engage in economic behaviors that maximize their utility but against the best interests of shareholders and stakeholders (Lin et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2016). Studies have provided evidence that D&O insurance leads to moral hazards from the perspectives of overinvestment, corporate mergers and acquisitions, and surplus management. For example, Chan et al. (2019) showed that D&O could easily become an “umbrella” for the self-interested behavior of executives because the risk-averse effect reduces the rent-seeking cost of executives, thereby increasing the eagerness of executives to economically over-invest. Based on a study of firms in Taiwan, Li and Liao, (2014) confirmed that D&O insurance coverage is positively associated with economic overinvestment, indicating that D&O insurance reduces corporate investment efficiency. Moreover, firms with higher levels of D&O insurance coverage are more likely to make aggressive merger and acquisition (M&A) decisions; however, these are accompanied by higher acquisition premiums, lower synergies, and lower shareholder returns (Lin et al., 2011). From the perspective of earning management, Boyer and Tennyson, (2015) and Chung and Wynn, (2008) pointed out that D&O insurance is associated with more aggressive earning management and less conservative earnings. Therefore, it may not be a wise investment for a company to purchase D&O insurance; nonetheless, it may still be of interest to company executives (Griffith, 2006). As executives use company funds to purchase enterprise-level D&O insurance, they protect their compensation and private benefits with a larger but infrequently expected loss, which is a classic representation of agency costs.

As a special form of non-economic investment, corporate environmental investment pursues comprehensive benefits, including economic, environmental, and social benefits; however, due to the diversified target requirements, long investment cycles, and low return on investment, it results in relatively low economic benefits (Gray and Shadbegian, 1998; Fisher-Vanden and Thorburn, 2011; Bhuiyan et al., 2021). Not only is it difficult for corporate environmental investment to generate direct economic inflows, but also it requires the companies to continuously spend large amounts of money on environmental facilities and environmental technology innovation (Orsato, 2006). As managers and firms seek to maximize the short-term economic benefits, they prefer to invest their limited resources in low-risk, high-return projects (Guariglia and Liu, 2014), rather than in less economically beneficial environmental projects; therefore, they are not willing to pursue environmental management and investment. Moreover, investing limited resources in environmental governance can constrain or crowd out the investment of firms in other economic and productive projects, which is contrary to the profit maximization goal of firms (Gray and Shadbegian, 1998). Particularly, in the Chinese capital market, the compensation evaluation system for executives of Chinese firms focuses on economic performance and does not increase executive compensation because of improved environmental and social performance resulting from corporate environmental investment. Accordingly, we predict that with the risk-sheltering and risk-transfer effects of D&O insurance, self-interested executives will actively seek private benefits associated with economic benefits rather than making decisions to allocate funds to environmental investments that have lower economic benefits or that even crowd out other economic projects.

In summary, based on the aforementioned analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

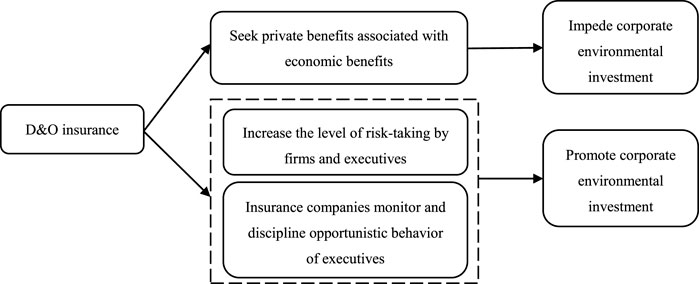

H1a. D&O insurance is negatively associated with corporate environmental investment.In contrast, D&O insurance may promote corporate environmental investment. D&O insurance increases the level of risk-taking for firms and executives by reducing their worries about incurring losses to the firm due to unintentional misconduct in the performance of their duties, thus helping managers make bold decisions that are beneficial to corporate governance, as well as the interests of shareholders and stakeholders (O'Sullivan, 1997; Jensen, 1993). This includes the decision to increase corporate investment in environmental protection because this may become part of the future core competencies of the company and increase corporate value. With the introduction of various environmental protection policies in China, consumers are becoming aware of the importance of protecting the environment. Therefore, the environmental investment of a company generates reputational benefits and stimulates consumer demand for environmental products (Liu and Wu, 2009), especially in a stable state, a high level of environmental investment also leads to a higher output (Liu and Wu, 2009). The company might then profit from these environmental investments and eventually turn them into core competencies (Orsato, 2006) and increase the company's value. Corporate environmental investment can also be an uncertain, long-term, and trial-and-error process. However, D&O insurance increases the level of risk-taking and the tolerance of managers to failure (Wang et al., 2020), which encourages firms to continue investing in the environment.In addition, by purchasing D&O insurance, the firm introduces an insurance company as an external monitor that restrains the opportunistic behavior of managers through multiple layers of supervision, thus contributing to a corporate environmental investment increase. Before underwriting, the insurer conducts a comprehensive risk assessment of the listed firm and the insured (directors and officers), including the financial situation and the risk management status, on which the rates charged are based (Boyer and Stern, 2014); in particular, the insurer will set strict insurance terms for high litigation risk companies. All of these are conducive to restraining the short-sighted behavior of firms, improving the efficiency of corporate governance, and increasing corporate environmental investment. During underwriting, the insurance company continuously evaluates the level of corporate governance and the project risks. If they find an increased risk of compensation, they will propose a modification plan and urge the firm to implement it, or even produce a warning effect by raising premiums (Li and Xu, 2020), all of which can improve the compensation structure of directors and the ownership structure of executives (O'Sullivan, 1997), and optimize the corporate governance mechanisms. Even in the event of a lawsuit, the insurance company conducts an in-depth investigation and pays for the liability of directors and officers for any negligent acts in performing their duties. To avoid large compensation for environmental liability, insurance companies, which have become corporate stakeholders, also have an incentive to monitor corporate compliance with environmental regulations and increase their investment in environmental protection and pollution reduction (Figure 2).In summary, based on the aforementioned analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1b. D&O insurance is positively associated with corporate environmental investment.

3 Research design

3.1 Sample

Since the Guidelines on Disclosure of Environmental Information for Companies Listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange were issued in 2008, the environmental investment data began in 2008. Accordingly, our initial sample includes Chinese A-share listed firms in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges for the period 2008–2019. We collect our data from several resources. First, data about D&O insurance are from the Chinese Research Data Services (CNRDS) Platform. Second, corporate environmental investment and other financial data were gathered from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) Database. To enable reasonable precision, all missing environmental investment observations were deleted, and we exclude firms with special treatment, firms that belong to financial industries, and firms with missing values. Limited by corporate environmental investment data, the total number of our final sample is 1,008 for 521 listed firms from 2008 to 2019. All the continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

3.2 Variables

3.2.1 Dependent variable: corporate environmental investment

Drawing on Li et al. (2019) and Bhuiyan et al. (2021), we use the natural logarithm of the amount of annual environmental investment to measure corporate environmental investment (EI), which is a common way to measure corporate green investment.

3.2.2 Independent variable: directors’ and officers’ insurance

Following previous studies (Lin et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2020), we adopt a dummy variable to measure D&O insurance (DO), which equals 1 if a firm purchases D&O insurance in a given year, and 0 otherwise.

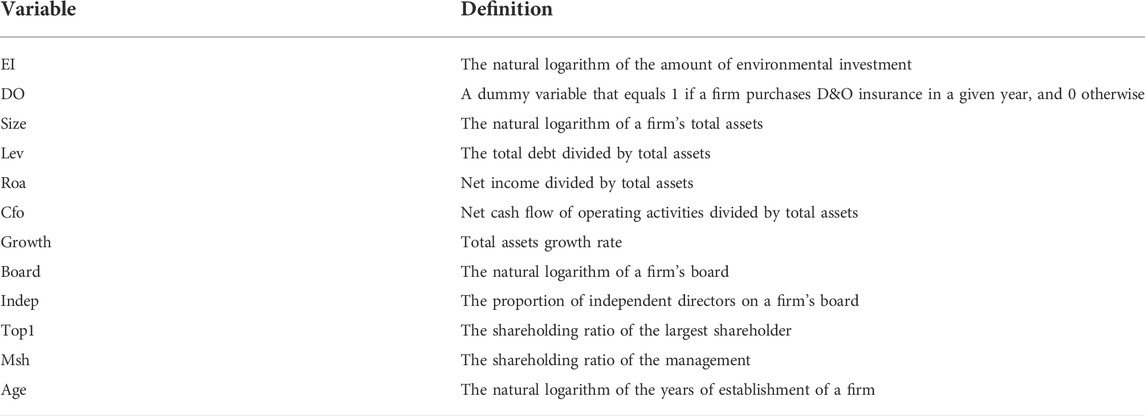

3.2.3 Control variable

Referring to previous studies (Li and Liao, 2014; Li et al., 2019), we control several factors that could influence a firm’s environmental investment activities as follows: firm size (Size), leverage ratio (Lev), return on assets (Roa), cash flow (Cfo), growth capacity (Growth), board size (Board), the proportion of independent directors (Indep), equity concentration (Top1), management shareholding (Msh), and firm age (Age). Furthermore, we control industry (Industry) and year (Year) effects. The definition of the aforementioned variables is presented in Appendix A.

3.3 Empirical model

We employ the following regression using an ordinary least squares (OLS) model with a pooled sample to capture the effect of D&O insurance on environmental investment:

where i, t, and j refer to firm, year, and control variables, respectively. εit denotes the disturbance. To reflect the long-term nature of environmental investment and alleviate the possible endogeneity issue, we use a one-year lead period to match environmental investment with D&O insurance. Robust standard errors are used in model estimates to eliminate heteroscedasticity.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

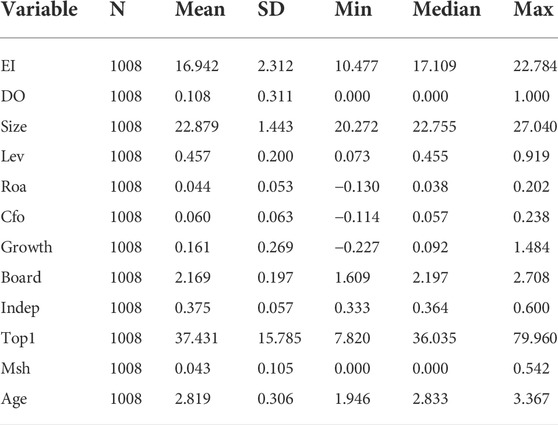

The descriptive statistics of the main variables in terms of mean value and standard deviation, as well as the minimum and maximum values, are reported in Table 1. The mean value of EI is 16.942, which is similar to the results of Li et al. (2019). The mean value of DO is 0.108, suggesting that 10.8% of firm-year observations are covered with D&O insurance in our sample.

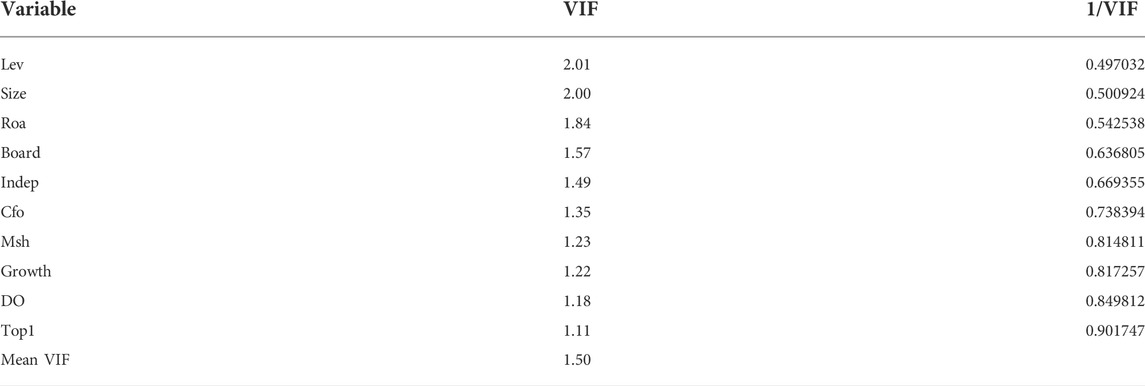

In addition, we calculate the variance inflation factors (VIFs) to evaluate whether multicollinearity exists among the variables. The results in Appendix B show that the VIF varies from 1.11 to 2.01, which is substantially lower than the critical value of 10 for multiple regression models (Griffith and Harvey, 2001), implying that there is no serious problem of multicollinearity in this study.

4.2 Results and analysis

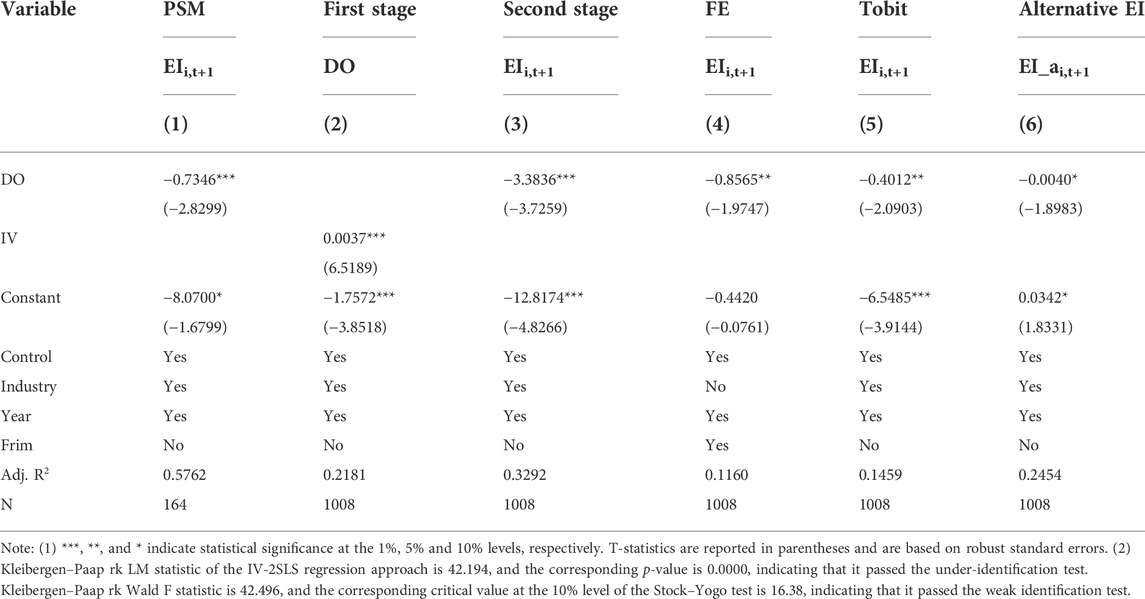

Table 2 reports the results of model 1. In column (1), we only incorporate control variables. Column (1) shows that the coefficients of the control variables are generally consistent with previous findings in the literature. Column (2) shows that the regression coefficient of DO is negative and significant at the 5% level, providing strong support for our Hypothesis 1a, that is, D&O insurance could inhibit corporate environmental investment. The result suggests that D&O insurance provides risk hedging and shelter for corporate executives to engage in behaviors that benefit their personal interests and reduce green investments.

4.3 Robustness tests

4.3.1 Propensity score matching approach

We use the propensity score matching approach to address potential endogeneity. Depending on whether the firm has D&O insurance or not, the treatment variable is considered to be one or zero, respectively. We employ a logit model to generate the propensity score of a firm with D&O insurance using the same control variables in Model 1 and match each observation for a firm with D&O insurance to a control firm with the closest propensity score to that of the analyzed firm. Finally, we obtained 164 firm-year observations. The result in column (1) of Table 3 indicates that the coefficient of DO is significantly negative at the 1% level, which supports our previous conclusions.

To ensure the reliability of the matching, we adopt a balance test, and the results are presented in Appendix C. The standard deviation (% bias) after matching significantly decreases to less than 20%. In addition, no significant difference in the mean of the characteristic variables was observed after matching, according to the statistical analysis using the t-test, indicating that the matching effect is effective.

4.3.2 Instrumental variable approach

We further employ the IV-2SLS regression approach to solve potential endogeneity problems. Drawing on Zhou et al. (2022), we use the number of insurance companies where the listed company is located as an instrumental variable. We expect that the higher the number of insurance companies, the more active the insurance market is likely to be, and therefore firms are more likely to cover D&O insurance, but no studies are showing that the number of insurance companies will directly affect corporate environmental investment. Columns (2) and (3) in Table 3 report the results of the 2SLS approach. It suggests that the regression coefficient of DO remains negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. Our results are robust when controlling for the endogeneity issue.

4.3.3 Other robustness tests

To ensure the robustness of our results, we also implement the following robustness tests: first, to address the omitted variable problem, we re-examine the model with fixed effects (FE). The result in column (4) of Table 3 suggests that the baseline regression is robust. Second, we replace the regression model with the Tobit model. Considering that the dependent variable contains some zero values, we replace the baseline OLS model with the Tobit model and re-examine our result. As seen in column (5) in Table 3, the conclusions are consistent with the previous. Last, we substitute the dependent variable. We use the alternative proxy EI_ai,t+1 measured as the amount of corporate environmental investment divided by the firm’s sales revenue. The result in column (6) in Table 3 remains unaltered.

5 Additional analyses

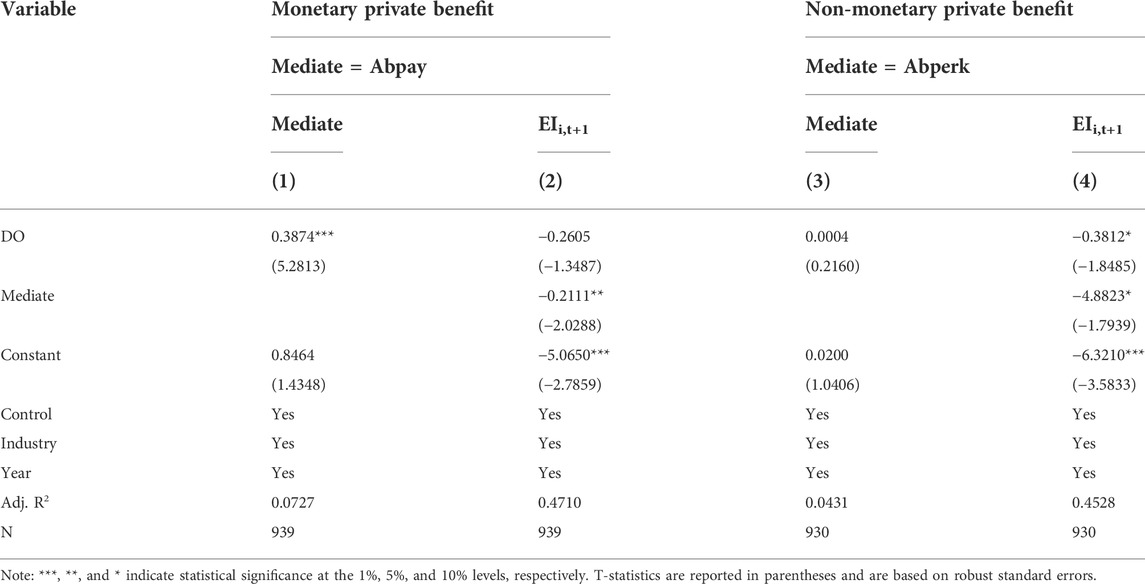

5.1 Intermediary mechanism tests

In the section on hypothesis development, we suggest that D&O insurance, which shifts the risk of litigation and liability that the insured may face to the insurer, tends to exacerbate principal–agent problems. This causes self-interested executives to actively seek private benefits associated with economic benefits rather than making decisions to allocate funds to environmental investments that are less economically efficient or that even crowd out other economic projects. Thus, we predict that D&O insurance may reduce corporate environmental investments by increasing the private benefits of executives. However, in this section, we further explore the intermediary role of these benefits in the relationship between D&O insurance and environmental investment.

Based on previous studies, we classify the private benefits of executives into monetary and non-monetary benefits. First, according to Firth et al. (2006) and Core et al. (2008), the monetary private benefits of executives refer to abnormal compensation (Abpay), which is measured by the difference between the actual compensation and the expected compensation that is determined by economic factors. The expected compensation is estimated using Model 2:

where Lnpay denotes the natural logarithm of the total compensation of the top three highest paying executives. Size and Roa are consistent with the definition of previous variables. Areawage is the average level of urban employees at the location of the company. Central and West are dummy variables indicating that the listed companies are in the central and western regions, respectively.

Second, according to Luo et al. (2011), the non-monetary private benefits of executives refer to abnormal on-the-job spending (Abperk), which is calculated by the difference between the actual on-the-job spending and the expected on-the-job spending that is determined by economic factors. The expected on-the-job spending is estimated using model 3:

where Perks indicates the executive on-the-job spending. Asset is the total assets. ΔSale represents the change in primary business revenue in period t. PPE is net fixed assets. Inventory is net inventory for the period t. Lnemployee is the natural logarithm of the total number of employees in the company.

Then, drawing on the intermediary effect model proposed by Baron and Kenny, (1986), we further construct the following models:

where i, t, and j represent the firm, year, and control variables, respectively. Mediate refer to Abpay and Abperk. DO, EI, and Control are consistent with the definition of variables in the benchmark regression mentioned previously. Robust standard errors are used in model estimates to eliminate heteroscedasticity.

The results of intermediary mechanism tests are reported in Table 4. Columns (1) and (2) show that DO is significantly positively correlated with Mediate (Mediate = Abpay) and Mediate (Mediate = Abpay) is also significantly negatively associated with EIi,t+1, indicating that D&O insurance inhibits corporate environmental investment by increasing monetary private benefits of executives. In addition, the coefficient of DO in column (2) is not significant, suggesting that monetary private benefits play a fully mediating effect in the relationship between D&O insurance and environmental investment. The results in column (3) show that the coefficient of DO is also not significant, indicating that non-monetary private benefits do not play an intermediary role in the process of D&O insurance influencing corporate environmental investment. In summary, our findings of the intermediary mechanism tests show that D&O insurance inhibits corporate environmental investment by driving executives to seek monetary private benefits, whereas non-monetary private benefits play no role.

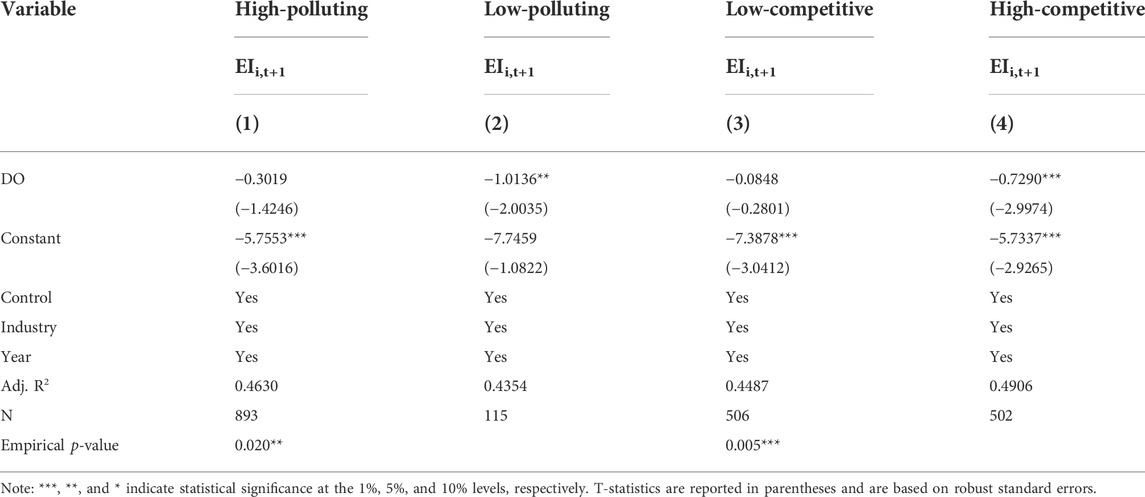

5.2 Heterogeneity analyses

Table 5 further explores the heterogeneity impact of D&O insurance on corporate environmental investment in different industries. Due to the significant differences in the degree of environmental pollution caused by different industries, corporate environmental investment will be affected by the attributes of polluting industries to a certain extent. Compared with low-polluting industries, high-polluting industries have long been subjected to strict environmental regulations and wide social concerns due to serious environmental pollution problems. Therefore, these industries started with environmental management earlier have relatively higher environmental awareness and are more willing to increase corporate environmental investment. However, for firms in low-polluting industries, lower environmental pressure may lead to low environmental awareness and low willingness to participate in environmental governance investment. Therefore, we predict that in low-polluting industries, executives may place less emphasis on environmental performance, making it more likely that D&O insurance will crowd out corporate environmental investment.

We divide listed companies into high-polluting and low-polluting companies based on industry codes 1 and regress Model 1 again. In column (1) of Table 5, we can find that the coefficient of DO in high-polluting companies is not significant. The possible reason for this is that, after a long period of development, firms in high-polluting industries have achieved some success in environmental management and therefore have limited marginal contribution to continued investment in the environment. In column (2) of Table 5, we can find that the coefficient of DO is significantly negative at the 5% level. It means that the disincentive effect of D&O insurance on environmental investment is more pronounced in low-polluting industries, which suggests that firms in low-polluting industries are more environmentally unaware and in these companies, D&O insurance is more likely to be used as a tool for selfish purposes by managers.

In addition, corporate environmental investment may be influenced to some extent by industry competition. When firms face fierce market competition, the conflict between their economic and environmental interests becomes evident, which leads to a more significant inhibitory effect of D&O insurance on corporate environmental investment. This is reflected in two ways. On the one hand, fierce market competition compresses the profit margins of enterprises and prompts them to reduce costs. After reaching the legal requirements of environmental investment, firms in a fiercely competitive environment are often reluctant to make too much environmental investment and are more concerned about whether the firm can gain more market share and economic benefits. This is because of the strong externality associated with environmental investment. Furthermore, excessive investment in environmental protection will increase the cost of enterprises, which is not conducive to a favorable position in fierce competition. Therefore, reducing high-cost environmental protection investments may be a means for firms to control costs. On the other hand, the appraisal of the performance of managers mainly emphasizes financial performance and neglects environmental performance. Therefore, when the market is more competitive, to avoid a decline in profits that affects performance appraisal, managers have more incentives to cut cost expenditures and reduce product costs, thus maintaining high compensation and monetary benefits, which crowd out environmental investments. Hence, we predict that the inhibitory effect of D&O insurance on corporate environmental investments is more pronounced in a more competitive market.

We use the Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI) of operating income to measure the competitiveness of industries. We divide the sample into two groups of high and low competition based on the median of the HHI and performed a group regression. The results in columns (3)–(4) of Table 5 show that the DO coefficient is not significant in low-competitive industries, whereas it is significantly negative in highly competitive industries. These findings indicated that the more competitive the market, the more the executives of the insured companies focus on economic interests, which leads to less environmental investment.

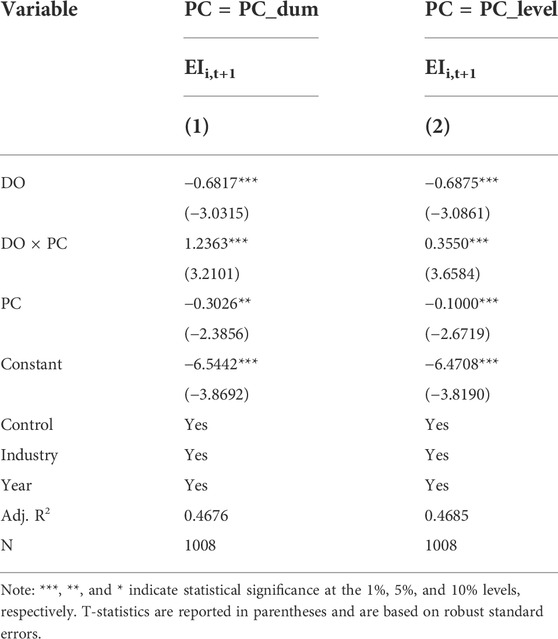

5.3 Political connection tests

According to the resource dependency theory, the government possesses important resources for the development of enterprises. Therefore, enterprises need to shape their relationship with the government for their long-term development (Wan and Luo, 2006). We expect that politically connected firms will actively respond to government policies and enhance corporate environmental investments to maintain their political and social capital. Accordingly, we further examine the impact of political connections on the relationship between D&O insurance and corporate environmental investment. Drawing on Jia et al. (2019) and Luo and Liu, (2019), we use PC_dum and PC_level to proxy political connections. Among them, PC_dum is a dummy variable that equals one if the chairman of the board or the CEO has served or is currently serving as a member of government departments, the National People’s Congress of China (NPC), or the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), and 0 otherwise. PC_level is a fixed-order variable that takes values between 1 and 4, depending on the degree of political ties at the county, city, province, and country levels, respectively. Otherwise, it takes the value 0.

Table 6 presents the results of political connection tests. Column 1) shows that the coefficient of the interaction term DO × PC (PC = PC_dum) is positive and significant at the 1% level, suggesting that the negative effect of D&O insurance on environmental investment is attenuated for firms with political connections. The coefficient of DO × PC (PC = PC_level) is also positive and significant at the 1% level in column (2). This finding suggests that higher levels of political connections mitigate the negative effect of D&O insurance on environmental investment.

6 Conclusion and recommendations

6.1 Conclusion

Based on the background of D&O insurance in China, this study uses data from A-share listed firms in China as a sample to study the impact of D&O insurance on corporate environmental investment. The results indicate the following: (1) D&O insurance is negatively associated with corporate environmental investment, which reveals the negative impact of D&O insurance on corporate environmental governance. (2) Executive monetary private benefits play a fully mediating role in the relationship between D&O insurance and corporate environmental investment, whereas non-monetary private benefits play no role. (3) The negative effect is more pronounced in low-polluting and highly competitive industries, indicating that the impact of D&O insurance on corporate environmental investment varies with the industry characteristics. (4) Political connections mitigate the negative relationship between D&O insurance and corporate environmental investment, and the higher the level of political connections, the more pronounced the mitigation effect, indicating that political–business relations play an important role in the corporate environmental governance process.

6.2 Recommendations

Our findings offer several practical recommendations. First, it is necessary to provide a favorable environment for D&O insurance governance. Enterprises should improve their internal governance and strengthen the supervision and punishment of executives displaying self-interested behavior, to prevent them from harming corporate environmental investment due to economic interests. However, insurance companies should also actively play an external governance function, for example, by increasing premiums, setting restrictive contract terms, and through ongoing monitoring to restrain the self-interested behavior of executives and encourage corporate participation in environmental governance.

Second, because the inhibitory effect of D&O insurance on corporate environmental investment is more significant in low-polluting and highly competitive industries, corresponding environmental governance incentives should be formulated according to the industry characteristics. For high-polluting industries, environmental governance should be continuously increased and environmental management should not be relaxed. Even in low-polluting industries, executives should improve their environmental awareness and social responsibility and increase environmental investment. In addition, companies can also incorporate environmental performance into executive performance appraisals, so that executives increase their emphasis on environmental responsibility, whether they are in a high- or low-polluting industry. For an industry with fierce competition, due to the gradual improvement in the awareness of consumers about environmental protection, enterprises can increase investment in the research and development of green products to obtain new profit growth points. At the same time, the government can also provide tax incentives for corporate environmental investment and other behaviors that are beneficial to the environment, thereby reducing the cost pressure on enterprises and enabling them to better cope with the fierce market competition.

Finally, the government should realize that most enterprises are still in the stage of being forced to accept environmental governance and that their willingness to enhance environmental investment is insufficient. Therefore, in future environmental protection work, the government should fully consider the economic and regulatory feasibility of corporate environmental investment. In terms of economic feasibility, the government can provide appropriate financial and policy support for environmental investment enterprises and encourage them to invest in green research and development to improve their environmental performance, while maintaining economic performance. Regarding regulatory feasibility, the government should enrich the environmental regulatory tools and improve the market-oriented environmental regulatory tools, such as pollution permits and emission trading rights. Thus, improving the market mechanism of environmental investment can promote the transformation of the corporate environmental investment from passive to active.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found at: Chinese Research Data Services Platform and China Stock Market and Accounting Research Database.

Author contributions

JL: conceptualization, validation, resources, data curation, and writing the original draft. YJ: methodology, software, writing—review and editing, and visualization. SG: review and editing and supervision. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to all those who helped them during the writing of the study and acknowledge the advice of the reviewers to improve the quality of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

D&O insurance, directors’ and officers’ liability insurance.

Footnotes

1Industry codes B, C, and D are classified as high-polluting industries.

References

Askildsen, J. E., Jirjahn, U., and Smith, S. C. (2006). Works councils and environmental investment: Theory and evidence from German panel data. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 60 (3), 346–372. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2004.01.006

Atif, M., Alam, M. S., and Hossain, M. (2020). Firm sustainable investment: Are female directors greener? Bus. Strategy Environ. 29 (8), 3449–3469. doi:10.1002/bse.2588

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological - research - conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173–1182. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bhuiyan, M. B. U., Huang, H. J., and de Villiers, C. (2021). Determinants of environmental investment: Evidence from europe. J. Clean. Prod. 292, 125990. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.125990

Boyer, M. M., and Stern, L. H. (2014). D&O insurance and IPO performance: What can we learn from insurers? J. Financial Intermediation 23 (4), 504–540. doi:10.1016/j.jfi.2014.05.001

Boyer, M. M., and Tennyson, S. (2015). Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance, corporate risk and risk taking: New panel data evidence on the role of directors’ and officers’ liability insurance. J. Risk Insur. 82 (4), 753–791. doi:10.1111/jori.12107

Chan, C. C., Chang, Y. H., Chen, C. W., and Wang, Y. W. (2019). Directors’ liability insurance and investment-cash flow sensitivity. J. Econ. Finan. 43, 27–43. doi:10.1007/s12197-017-9425-7

Chang, K. C., Wang, D., Lu, Y. Y., Chang, W., Ren, G. Q., Liu, L., et al. (2021). Environmental regulation, promotion pressure of officials, and enterprise environmental protection investment. Front. Public Health 9, 724351. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.724351

Chen, C. Y. (2016). D&O insurance, corporate governance and mandatory disclosure: An empirical legal study of taiwan. Asian J. Law Econ. 7 (1), 19–62. doi:10.1515/ajle-2015-0014

Chen, Z. H., Li, O. Z., and Zou, H. (2016). Directors' and officers' liability insurance and the cost of equity. J. Account. Econ. 61 (1), 100–120. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2015.04.001

Chung, H. H., and Wynn, J. P. (2008). Managerial legal liability coverage and earnings conservatism. J. Account. Econ. 46 (1), 135–153. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2008.03.002

Claessens, S., Djankov, S., and Lang, L. H. P. (2000). The separation of ownership and control in east asian corporations. J. Financ. Econ. 58 (1-2), 81–112. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00067-2

Core, J. E., Guay, W., and Larcker, D. F. (2008). The power of the pen and executive compensation. J. Financ. Econ. 88 (1), 1–25. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.05.001

Costa-Campi, M. T., Garcia-Quevedo, J., and Martinez-Ros, E. (2017). What Are the Determinants of Investment in Environmental R&D Energy Policy 104, 455–465. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.01.024

Firth, M., Fung, P. M. Y., and Rui, O. M. (2006). Corporate performance and CEO compensation in China. J. Corp. Finance 12 (4), 693–714. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2005.03.002

Fisher-Vanden, K., and Thorburn, K. S. (2011). Voluntary corporate environmental initiatives and shareholder wealth. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 62 (3), 430–445. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2011.04.003

Gray, W. B., and Shadbegian, R. J. (1998). Environmental regulation, investment timing, and technology choice. J. Ind. Econ. 46 (2), 235–256. doi:10.1111/1467-6451.00070

Griffith, A. J. (2006). Uncovering A gatekeeper: Why the sec should mandate disclosure of details concerning directors' and officers' liability insurance policies. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 154 (5), 1147–1208. doi:10.2307/40041321

Griffith, D. A., and Harvey, M. G. (2001). A resource perspective of global dynamic capabilities. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 32 (3), 597–606. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490987

Guariglia, A., and Liu, P. (2014). To what extent do financing constraints affect Chinese firms' innovation activities? Int. Rev. Financial Analysis 36, 223–240. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2014.01.005

Hoyt, R. E., and Khang, H. (2000). On the demand for corporate property insurance. J. Risk Insur. 67 (1), 91–107. doi:10.2307/253678

Hwang, J. H., and Kim, B. (2018). Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance and firm value. J. Risk Insur. 85 (2), 447–482. doi:10.1111/jori.12136

Jensen, M. C. (1993). The modern industrial - revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control - systems. J. Finance 48 (3), 831–880. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1993.tb04022.x

Jia, N., Mao, X. S., and Yuan, R. L. (2019). Political connections and directors' and officers' liability insurance - evidence from China. J. Corp. Finance 58, 353–372. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2019.06.001

Li, C. G., and Xu, R. (2020). Insurance governance and corporate irregularities: A study of the governance effects of directors' executive liability insurance. Financ. Res. 6, 188–206.

Li, K. F., and Liao, Y. P. (2014). Directors' and officers' liability insurance and investment efficiency: Evidence from taiwan. Pacific-Basin Finance J. 29, 18–34. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2014.03.001

Li, F., Li, T., and Minor, D. (2016). CEO power, corporate social responsibility, and firm value: A test of agency theory. Int. J. Manage. Financ. 12 (5), 611–628. doi:10.1108/ijmf-05-2015-0116

Li, Q., Ruan, W. J., Sun, T. T., and Xiang, E. W. (2019). Corporate governance and corporate environmental investments: Evidence from China. Energy & Environ. 31 (6), 923–942. doi:10.1177/0958305x19882372

Lin, C., Officer, M. S., and Zou, H. (2011). Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance and acquisition outcomes. J. Financ. Econ. 102 (3), 507–525. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.08.004

Liu, C. Y., and Wu, C. H. (2009). Environmental consciousness, reputation and voluntary environmental investment. Aust. Econ. Pap. 48 (2), 124–137. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8454.2009.00366.x

Luo, W., Zhang, Y., and Zhu, N. (2011). Bank ownership and executive perquisites: New evidence from an emerging market. J. Corp. Finance 17 (2), 352–370. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2010.09.010

Luo, X. Y., and Liu, W. (2019). Political connection and corporate environmental violation penalties: Sheltering or monitoring-evidence from IPE Database. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 41 (10), 85–99. doi:10.13781/j.cnki.1007-9556.2019.10.007

Maggioni, D., and Santangelo, G. D. (2017). Local environmental non-profit organizations and the green investment strategies of family firms. Ecol. Econ. 138, 126–138. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.03.026

Maxwell, J. W., and Decker, C. S. (2006). Voluntary environmental investment and responsive regulation. Environ. Resour. Econ. (Dordr). 33 (4), 425–439. doi:10.1007/s10640-005-4992-z

O'Sullivan, N. (1997). Insuring the agents: The role of directors' and officers' insurance in corporate governance. J. Risk Insur. 64 (3), 545–556. doi:10.2307/253764

Orsato, R. J. (2006). Competitive environmental strategies: When does it pay to Be green? Calif. Manage. Rev. 48 (2), 127–143. doi:10.2307/41166341

Shen, H. B., Xie, Y., and Chen, Z. R. (2012). Corporate environmental protection, social responsibility and its market response: A case study based on zijin mining's environmental pollution incident. Chin. Ind. Econ. 1, 141–151. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2012.01.014

Tang, G. P., Li, L. H., and Wu, D. J. (2013). Environmental regulation, industry attributes and corporate environmental investment. Acc. Res. 6, 83–89+96. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-2886.2013.06.012

Tian, J., Yu, L., Xue, R., Zhuang, S., and Shan, Y. (2022). Global low-carbon energy transition in the post-COVID-19 era. Appl. Energy 307, 118205. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.118205

Wan, L., and Luo, Y. F. (2006). An equilibrium model of corporate social responsibility. Chin. Ind. Eco. 9, 117–124. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2006.09.015

Wang, J. L., Zhang, J., Huang, H. Y., and Zhang, F. (2020). Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance and firm innovation. Econ. Model. 89, 414–426. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2019.11.011

Yan, Y. L., and Xu, X. X. (2020). Does entrepreneur invest more in environmental protection when joining the communist party? Evidence from Chinese private firms. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 58, 754–775. doi:10.1080/1540496x.2020.1848814

Yang, D. F., Wang, Z. Q., and Lu, F. M. (2019). The influence of corporate governance and operating characteristics on corporate environmental investment: Evidence from China. Sustainability 11 (10), 2737. doi:10.3390/su11102737

Yuan, R. L., Sun, J., and Cao, F. (2016). Directors' and officers' liability insurance and stock price crash risk. J. Corp. Finance 37, 173–192. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.12.015

Zhang, D. Y., Du, W. C., Zhuge, L. Q., Tong, Z. M., and Freeman, R. B. (2019). Do financial constraints curb firms’ efforts to control pollution? Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. J. Clean. Prod. 215, 1052–1058. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.112

Zhou, D. H., Luo, S. Z., and Zhao, Y. J. (2022). Directors' and officers' liability insurance and corporate innovation. Sci. Res. Manage. 43 (4), 201–208. doi:10.19571/j.cnki.1000-2995.2022.04.023

Zou, H., Wong, S., Shum, C., Xiong, J., and Yan, J. (2008). Controlling-minority shareholder incentive conflicts and directors’ and officers’ liability insurance: Evidence from China. J. Bank. Finance 32 (12), 2636–2645. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2008.05.015

Appendix A Variable definitions.

Appendix B VIF multicollinearity test.

Appendix C Balance test after PSM.

Keywords: D&O insurance, corporate environmental investment, private benefits, monetary benefits, political connections

Citation: Liu J, Jiang Y and Gan S (2022) How does D&O insurance affect corporate environmental investment?. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:960097. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.960097

Received: 02 June 2022; Accepted: 08 August 2022;

Published: 02 September 2022.

Edited by:

Rui Xue, Macquarie University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Luigi Aldieri, University of Salerno, ItalyXiaotong Yang, Shandong University of Finance and Economics, China

Yong Ye, Southwest Jiaotong University, China

Copyright © 2022 Liu, Jiang and Gan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yalin Jiang, amlhbmd5YWxpbjg5QDE2My5jb20=

Jiamin Liu

Jiamin Liu Yalin Jiang

Yalin Jiang Shengdao Gan

Shengdao Gan